#Willa Muir

Text

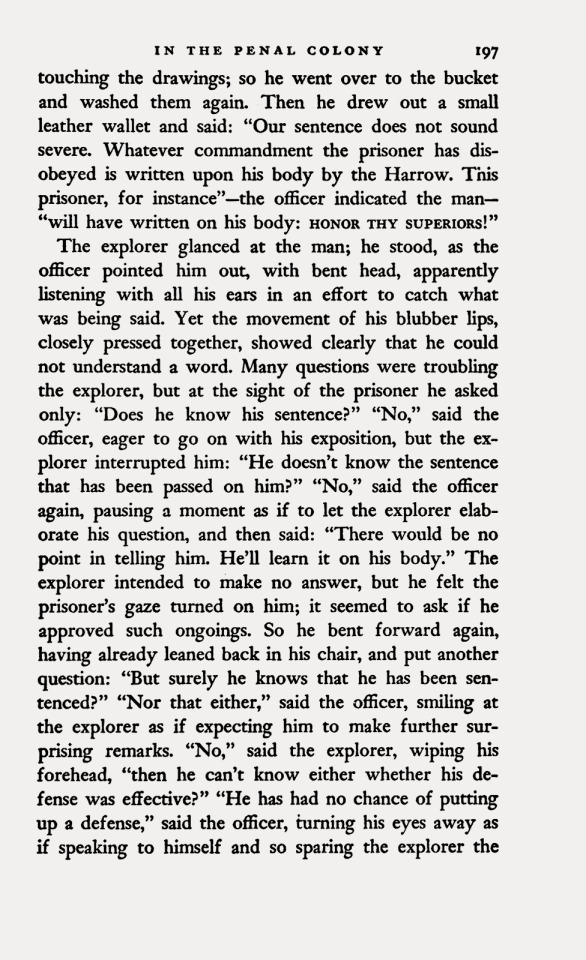

Franz Kafka, (1919), In the Penal Colony, in In the Penal Colony. Stories and Short Pieces, Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir, Schocken Books, New York, NY, 1948, p. 197

«[…] "Does he know his sentence?" "No," said the officer, eager to go on with his exposition, but the explorer interrupted him: "He doesn't know the sentence that has been passed on him?" "No," said the officer again, pausing a moment as if to let the explorer elaborate his question, and then said: "There would be no point in telling him. He'll learn it on his body."»

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hermann Broch ~ Lettere alla traduttrice Willa Muir

Max Ernst, L’Ange du Foyer, 1937

Tragico è che questo male esiste realmente nell’ebraismo e che contro di esso si riesce ad infiammarsi sempre di nuovo, non certo per avversione al male, ma per legittimare la malvagità, cioè per poter meglio « punire » l’ebreo o depredarlo.

Hermann Broch

Lettere a Willa Muir (e Stephen Hudson)

Vienna, 1- Gonzagagasse 7

21 giugno…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Franz Kafka- Short Stories

Literature is the most extraordinary gift. It's timeless, precious, informative…

At least, it can be--

Once you figure out how to unwrap the damn thing!

Franz Kafka is a writer that I don't understand. Simply put. He uses language in a way that amazes my senses, curdles my brain, expands my heart, and threshes my ways of thinking. Still, I do not understand him. However, because of this, I do experience his writing most intensely. So, in a way, I feel like Franz Kafka is like a literary impressionist. Things aren't always clear upon first glance, but with patience, an open mind, and softer observations, they become more beautiful for being so.

Since it's my first time reading Kafka, I bought The Metamorphosis and Other Stories published by Schocken Books (translated by Willa and Edwin Muir). My favorite group of writings Kafka did are listed under the "Meditation" and "The Country Doctor" sections. I love how they are like glimpses into his mind and the world he perceives with it. There's one story in particular, "Children on a Country Road", that's about a group of boys running through the countryside that makes me feel so happy and nostalgic. I absolutely love it… but, again, I must confess, I had to read these stories multiple times to comprehend on a basic level what they were about. As was the case with the larger stories like "The Metamorphosis" and "In the Penal Colony", which were fascinating but emotionally and mentally challenging.

Working to understand something, digging tirelessly to unearth the root, is quite satisfying for me. I like the "click." That moment of understanding when all the details fall perfectly into place, and it feels as if the information takes on a deeper resonance. Reading Kafka has challenged this way of thinking.

Like a fox digging excitedly at the burrow while the rabbit watches from above… Now I see that sometimes the deeper you stoop to claw at an idea, the more room you make for it to leap over your head. We all think we're clever until we're walking home exhausted and unsatisfied.

So, look up. Look at things in their entirety, vague and frustrating as it is, and appreciate them when you can. Then say to yourself, contentedly and not resentfully, "I don't understand, but…"

It's beautiful anyway. It's important anyway. It's affecting anyway. It's lovely anyway. It's taught me something anyway.

So, what do I think of Kafka? I think he has broken my heart, tormented my mind, and kindled my soul. I think he's an extraordinary writer with a unique vision that is difficult to process. I think he had a lot to say as a young man, as a young writer, who didn't like how the world could be equal parts cruel and beautiful… and I think he didn't understand either: himself, his passion, or his impact. But, to say that indefinitely would be out of turn. So, I'll say this instead:

I think Franz Kafka is…

And I'll let that be that.

#literature#books & libraries#dark academia#romantic academia#light academia#aesthetic#books#words#classic academia#franz kafka#picture source: pinterest#the metamorphosis#personal#bookshelf#bookblr

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

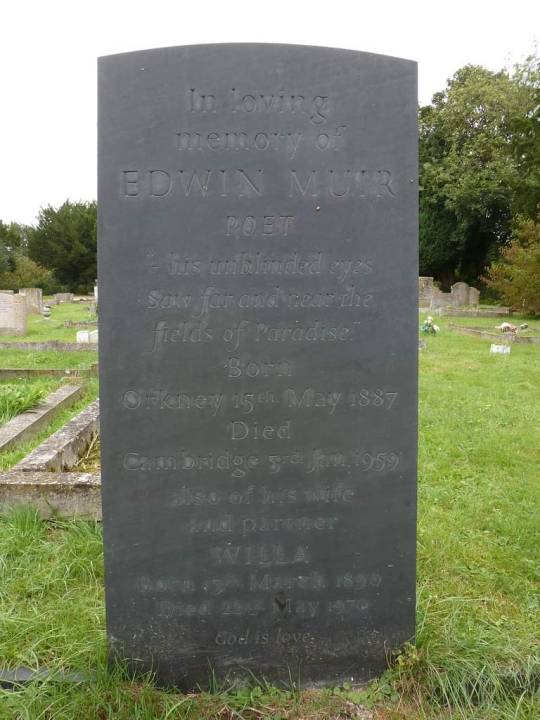

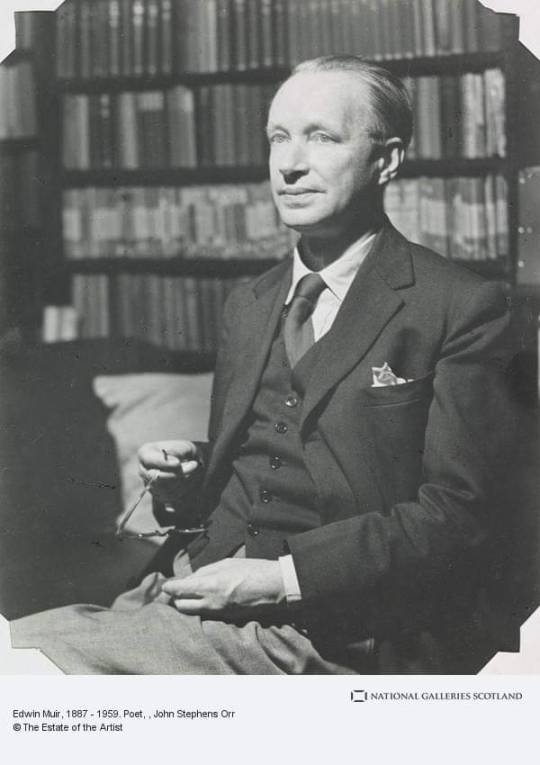

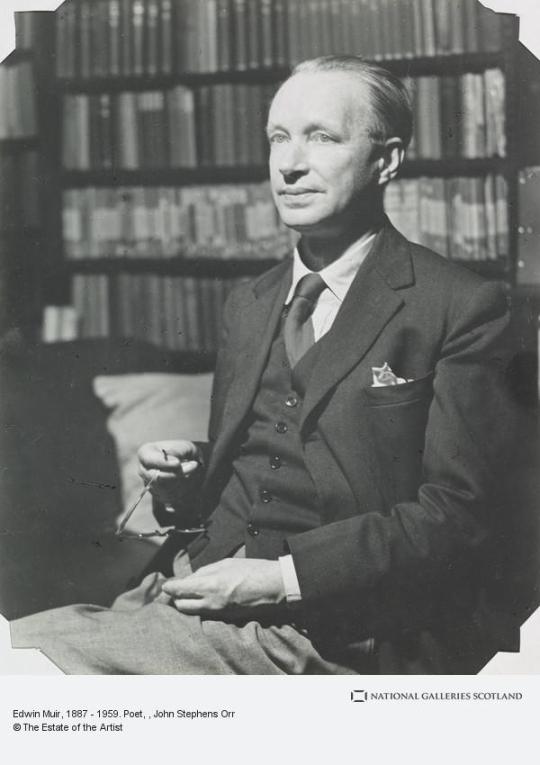

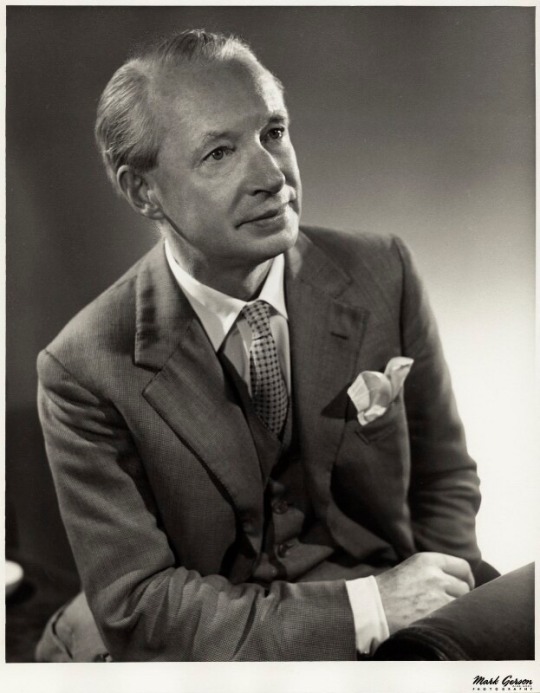

January 3rd 1959 saw the death of the poet and scholar Edwin Muir.

Born on the Orkney island of Wyre in 1887, Muir spent his early years in the idyllic setting of his father’s farm, ‘The Bu, when he was 14, his father lost his farm, and the family moved to Glasgow. In quick succession his father, two brothers, and his mother died within the space of a few years. His life as a young man was a depressing experience, and involved a raft of unpleasant jobs in factories and offices, including working in a factory that turned bones into charcoal. “He suffered psychologically in a most destructive way, although perhaps the poet of later years benefited from these experiences as much as from his Orkney 'Eden’.”

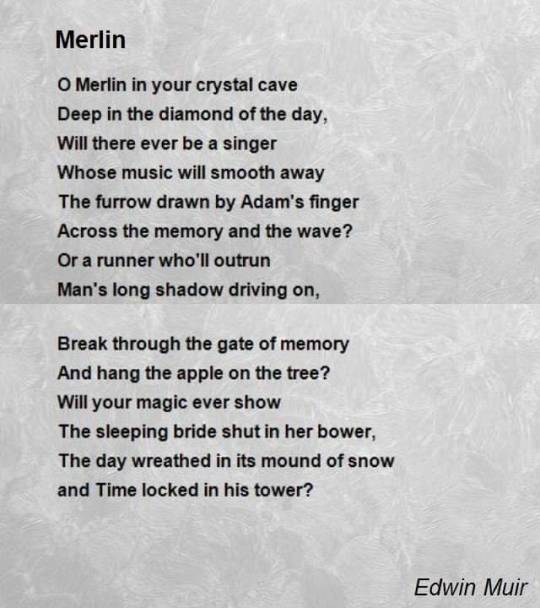

Termed a philosophical, political and social poet, Muir’s poetry attempts to find meaning and pattern in life, harmony & cooperation instead of competition and conflict; popular themes include a sense of timelessness, a sense of displacement and rootlessness and innocence. He travelled in Europe with his wife and fellow writer, Willa Muir, translating European writers such as Franz Kafka into English. The Muirs were significantly involved in the Scottish Literary Renaissance.

In 1955 he was made Norton Professor of English at Harvard University. He returned to Britain in 1956 but died in 1959 at Swaffham Prior, Cambridge, and was buried there.

A memorial bench was erected in 1962 to Muir in the idyllic village of Swanston, Edinburgh, where he spent time during the 1950s, there is also a Memorial to Edwin Muir in St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, Orkney.

Scotland's Winter.

Now the ice lays its smooth claws on the sill,

The sun looks from the hill

Helmed in his winter casket,

And sweeps his arctic sword across the sky.

The water at the mill

Sounds more hoarse and dull.

The miller's daughter walking by

With frozen fingers soldered to her basket

Seems to be knocking

Upon a hundred leagues of floor

With her light heels, and mocking

Percy and Douglas dead,

And Bruce on his burial bed,

Where he lies white as may

With wars and leprosy,

And all the kings before

This land was kingless,

And all the singers before

This land was songless,

This land that with its dead and living waits the Judgement Day.

But they, the powerless dead,

Listening can hear no more

Than a hard tapping on the floor

A little overhead

Of common heels that do not know

Whence they come or where they go

And are content

With their poor frozen life and shallow banishment.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

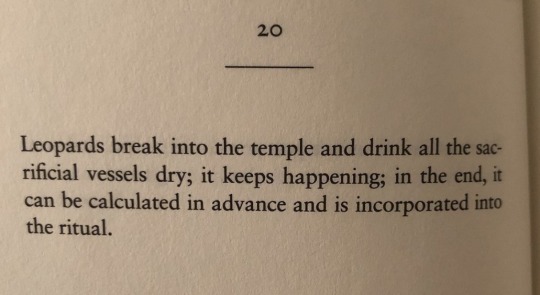

Franz Kafka: Aphorisms (The Zürau Aphorisms), which he wrote after being diagnosed with the illness that would kill him. Translated by Edwin and Willa Muir & Michael Hofmann, Schocken Books, 2015

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Many questions were troubling the explorer, but at the sight of the prisoner he asked only: ‘Does he know his sentence?’ ‘No,’ said the officer, eager to go on with his exposition, but the explorer interrupted him: ‘He doesn’t know the sentence that has been passed on him?’ ‘No,’ said the officer again, pausing a moment as if to let the explorer elaborate his question, and then said: ‘There would be no point in telling him. He’ll learn it on his body.’”

— Kafka, “The Penal Colony”, trans. Willa Muir & Edwin Muir (1948)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Little Fable, by Franz Kafka

"Alas", said the mouse, "the whole world is growing smaller every day. At the beginning it was so big that I was afraid, I kept running and running, and I was glad when I saw walls far away to the right and left, but these long walls have narrowed so quickly that I am in the last chamber already, and there in the corner stands the trap that I am running into."

"You only need to change your direction," said the cat, and ate it up.

***

"A Little Fable" (German: "Kleine Fabel") is a short story written by Franz Kafka between 1917 and 1923, likely in 1920. The anecdote, only one paragraph in length, was not published in Kafka's lifetime and first appeared in Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer (1931). The first English translation by Willa and Edwin Muir was published by Martin Secker in London in 1933. Wikipedia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

True, [Josephine] does not save us and she gives us no strength; it is easy to stage oneself as a savior of our people, inured as they are to suffering, not sparing themselves, swift in decision, well acquainted with death, timorous only to the eye in the atmosphere of reckless daring which they constantly breathe, and as prolific besides as they are bold—it is easy, I say, to stage oneself after the event as the savior of our people, who have always somehow managed to save themselves, although at the cost of sacrifices which make historians—generally speaking we ignore historical research entirely—quite horror-struck. And yet it is true that just in emergencies we hearken better than at other times to Josephine’s voice.

Franz Kafka, “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk,” in The Metamorphosis and Other Stories, trans. Edwin and Willa Muir

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hell yeah book asks! 2, 10, 11, 15 please 😌

2. top 5 books of all time?

ohhhh you can't do this to me.....i also can't order them. & i'm limiting myself to only one discworld, that way lies madness.

-Thud! by Terry Pratchett

-The Color Purple by Alice Walker

-The Dark is Rising by Susan Cooper

-gotta have Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir on here

-One Day at Teton Marsh by Sally Carrighar is a book I haven't reread in maybe 15 years and I can still picture specific scenes

10. do you have a guilty fav?

I loved The Host by Stephanie Meyer 😔 My copy is uhhh probably in a storage unit in New Jersey so I haven't reread it in a decade but I was a big fan! and even then I'm pretty gung-ho about books I like...if I liked having printed fic it would be a different story.

11. what non-fiction books do you like if any?

oh man SO many! I love good popular nonfiction! I'd especially recommend Mark Kurlansky as an author -- he writes a lot of single-topic books that go in depth into the history of a specific food. so: Salt. Cod. Milk. Paper. etc

15. recommend and review a book.

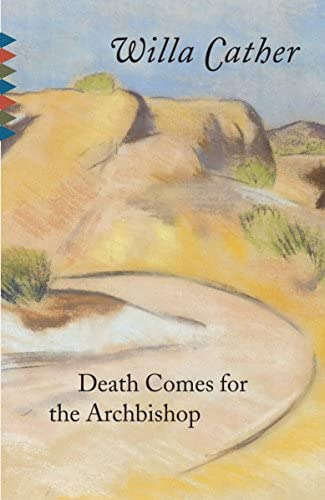

hmmmmm...let's switch gears, and go for Death Comes for the Archbishop by Willa Cather!

Cather is an incredibly skilled illustrator of the American Southwest. I first read The Professor's House for a class in college, and the middle section in the desert is captivating -- this book is ALL that beautiful description. Death Comes is about a bishop establishing a Catholic diocese in New Mexico in the mid-late 1800s, and in the way of such a topic it's a fascinating book to read with a modern perspective, and with *my* perspective (not necessarily equivalent), on colonization and missionaries.

this book is meandering, and takes time for small conversations. it's also very good as a readaloud (...especially if you speak french, there's a lot of it)!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Passeggiera

Translating the book, there's one important comforting fact: Willa Muir (known as * * Scott, if you know, you know) did not turn German version into English the way as she would want it to be. (In short, translations of the book in any language don't exist.)

The only version is the one which is closest to the original, and no matter into which language it is being tanslated or was translated. (It's applicable to any book in existence.)

0 notes

Text

Before the Law

Franz Kafka

Before the law stands a doorkeeper.

To this doorkeeper there comes a man from the country and prays for admittance to the Law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant admittance at the moment. The man thinks it over and then asks if he will be allowed in later. "It is possible," says the doorkeeper, "but not at the moment."

Since the gate stands open, as usual, and the doorkeeper steps to one side, the man stoops to peer through the gateway into the interior. Observing that, the doorkeeper laughs and says: "If you are so drawn to it, just try to go in despite my veto. But take note: I am powerful. And I am only the least of the doorkeepers. From hall to hall there is one doorkeeper after another, each more powerful than the last. The third doorkeeper is already so terrible that even I cannot bear to look at him."

These are difficulties the man from the country has not expected; the Law, he thinks, should surely be accessible at all times and to everyone, but as he now takes a closer look at the doorkeeper in his fur coat, with his big sharp nose and long, thin, black Tartar beard, he decides that it is better to wait until he gets permission to enter. The doorkeeper gives him a stool and lets him sit down at one side of the door.

There he sits for days and years. He makes many attempts to be admitted, and wearies the doorkeeper by his importunity. The doorkeeper frequently has little interviews with him, asking him questions about his home and many other things, but the questions are put indifferently, as great lords put them, and always finish with the statement that he cannot be let in yet.

The man, who has furnished himself with many things for his journey, sacrifices all he has, however valuable, to bribe the doorkeeper. The doorkeeper accepts everything, but always with the remark: "I am only taking it to keep you from thinking you have omitted anything."

During these many years the man fixes his attention almost continuously on the doorkeeper. He forgets the other doorkeepers, and this first one seems to him the sole obstacle preventing access to the Law. He curses his bad luck, in his early years boldly and loudly; later, as he grows old, he only grumbles to himself.

He becomes childish, and since in his yearlong contemplation of the doorkeeper he has come to know even the fleas in his fur collar, he begs the fleas as well to help him and to change the doorkeeper's mind. At length his eyesight begins to fail, and he does not know whether the world is really darker or whether his eyes are only deceiving him. Yet in his darkness he is now aware of a radiance that streams inextinguishably from the gateway of the Law.

Now he has not very long to live. Before he dies, all his experiences in these long years gather themselves in his head to one point, a question he has not yet asked the doorkeeper. He waves him nearer, since he can no longer raise his stiffening body. The doorkeeper has to bend low toward him, for the difference in height between them has altered much to the man's disadvantage.

"What do you want to know now?" asks the doorkeeper; "you are insatiable."

"Everyone strives to reach the Law." says the man, "so how does it happen that for all these many years no one but myself has ever begged for admittance?"

The doorkeeper recognizes that the man has reached his end, and, to let his failing senses catch the words, roars in his ear: "No one else could ever be admitted here, since this gate was made only for you. I am now going to shut it."

--translated by Willa and Edwin Muir

0 notes

Text

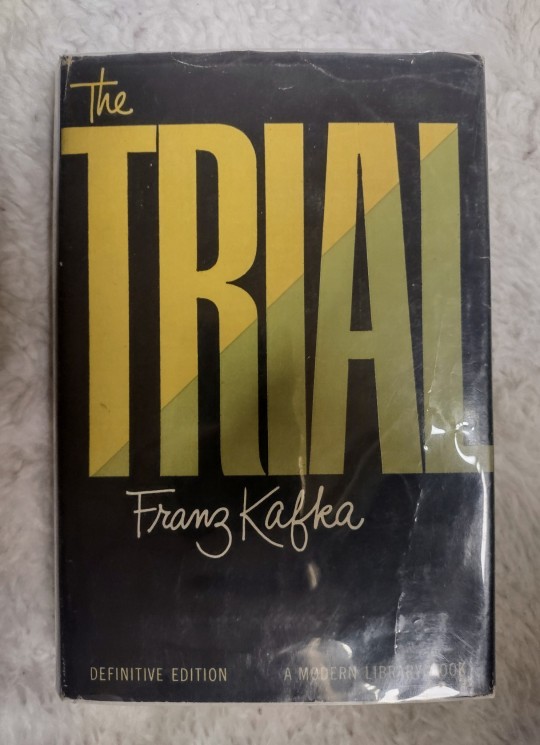

The Trial by Franz Kafka: Definitive edition, translated from the German by Willa and Edwin Muir, revised with additional materials translated by E.M. Butler, published 1956.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Before the Law

(broken into paragraphs by the dictates of Tumblr)

Before the Law stands a doorkeeper. To this doorkeeper there comes a man from the country and prays for admittance to the Law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant admittance at the moment. The man thinks it over and then asks if he will be allowed in later. "It is possible," says the doorkeeper, "but not at the moment."

Since the gate stands open, as usual, and the doorkeeper steps to one side, the man stoops to peer through the gateway to the interior.

Observing that, the doorkeeper laughs and says: "If you are so drawn to it, just try to go in despite my veto. But take note: I am powerful. And I am only the least of the doorkeepers. From hall to hall there is one doorkeeper after another, each more powerful than the last. The third doorkeeper is already so terrible that even I cannot bear to look at him."

These are difficulties the man from the country has not expected; the Law, he thinks, should surely be accessible at all times and to everyone, but as he now takes a closer look at the doorkeeper in his fur coat, with his big sharp nose and long, thin, black Tartar beard, he decides that it is better to wait until he gets permission to enter.

The doorkeeper gives him a stool and lets him sit down at one side of the door. There he sits for days and years. He makes many attempts to be admitted, and wearies the doorkeeper by his importunity.

The doorkeeper frequently has little interviews with him, asking him questions about his home and many other things, but the questions are put indifferently, as great lord put them, and always finish with the statement that he cannot be let in yet.

The man, who has furnished himself with many things for his journey, sacrifices all he has, however valuable, to bribe the doorkeeper. The doorkeepr accepts everything, but always with the remark: "I am only taking it to keep you from thinking you have omitted anything."

During these many years the man fixes his attention almost continuously on the doorkeeper. He forgets the other doorkeepers, and the first one seems to him the sole obstacle preventing access to the Law.

He curses his bad luck, in his early years boldly and loudly; later, as he grows old, he only grumbles to himself. He becomes childish, and since in his yearlong contemplation of the doorkeeper he has come to know even the fleas in his fur collar, he begs the fleas as well to help him and to change the doorkeeper's mind. At length his eyesight begins to fail, and he does not know whether the world is really darker or whether his eyes are only deceiving him. Yet in his darkness he is now aware of a radiance that streams forth inextinguishably from the gateway of the Law.

Now he has not very long to live. Before he dies, all his experiences in these long years gather themselves in his head to one point, a question he has not yet asked the doorkeeper.

He waves him nearer, since he can no longer raise his stiffening body.

The doorkeeper has to bend low toward him, for the difference in height between them has altered much to the man's disadvantage.

"What do you want to know now?" asks the doorkeeper; "you are insatiable. "

"Everyone strives to reach the Law," says the man, "so how does it happen that for all these many years no one but myself has ever begged for admittance?"

The doorkeeper recognizes that the man has reached his end, and, to let his failing senses catch the words, roars in his ear:

"No one else could ever be admitted here, since this gate was made only for you. I am now going to shut it."

Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir

1 note

·

View note

Text

Você já ouviu falar sobre a WILLA MUIR? Ouvi dizer que é uma pessoa… interessante. Ela estuda lá no Departamento de Design, acho que tá no 4º ano do curso de Design de Moda, vai fazer 28 anos, mas acho que não participa de nenhum grupo. Ainda não sabe? Bom, não sei muito mais sobre. Ela realmente tem um rosto pra fama, até se parece com aquela Jisoo, do BLACKPINK. Ah! Acho que tenho o twitter dela aqui, é @kyg_willa. Às vezes, quando falamos assim, eu penso que queria ser uma formiguinha porque morro de curiosidade para saber como foi a entrevista dos outros. Você consegue imaginar?

Como você já deve saber, na Kyonggi University prezamos conhecer bem e manter uma relação próxima com o nosso corpo estudantil, então por que você não me conta um pouco de como você chegou aqui? Começando por seu interesse pelas artes. Você descobriu esse interesse sozinho, tem familiares no ramo, teve alguma influência? Algum professor, colega…

Influência familiar. As pessoas conhecem a Muir, claro. Quero dizer, é uma marca famosa há décadas, mesmo se eu não me interessasse naturalmente pela moda, eu me interessaria, se é que me entende. Algumas pessoas nascem com os seus caminhos já trilhados, a questão é se a pessoa vai querer andar por cima do trilho ou desviar. Eu prefiro andar nos trilhos, sabe? Quem seria maluco de não querer trabalhar em família, não é? Eu nem me vejo fazendo outra coisa, pra falar bem a verdade, então… não sei, se você tem a oportunidade de trabalhar na empresa dos seus pais, trabalhe na empresa dos seus pais.

E como você acabou aqui hoje? É um desejo próprio? Um sonho, talvez. Ou você quer sair correndo por essa porta agora? [risos] Não se preocupe, você não seria o primeiro artista que sonhava em ser advogado, por mais estranho que isso soe.

Meus pais me obrigaram. As pessoas sempre falam que o nepotismo é fácil, mas não é, não. Se fosse fácil, eu só esperaria o velho morrer pra ficar no lugar dele, mas ele quer que eu saiba fazer alguma coisa além de… esperar ele morrer. Ainda é um saco ter que ficar longe da minha casa, da minha cidade… [suspiro longo] que saudades de Nova York… enfim! Eu só quero me formar logo. Mas se meu pai está feliz que estou aqui fazendo alguma coisa além de ser filha dele, que bom, isso é legal, também. Sei que ele quer que a empresa fique em boas mãos e eu quero provar que posso ser essa pessoa.

Certo, certo. E você já teve algum treinamento profissional, ou a Kyonggi será sua primeira experiência? Somos um ótimo lugar pra começar, você sabe, vários dos nossos alunos chegam até nós apenas com seus talentos brutos. Você diria que é natural no que faz, ou do tipo que precisa de muito esforço, ou uma mão forte para te guiar? Como você descreveria sua personalidade, no geral?

É, eu tenho algumas boas experiências na Muir e… é só. Fui diretora criativa por alguns meses, mas isso meio que foi um treinamento, tinha uma pessoa mais experiente comigo, se é que assim posso dizer. Criamos coisas muito legais e a maioria das minhas ideias foram usadas, eu realmente fui útil pra coleção, mas meu pai decidiu que eu precisava de mais do que prática e sorte… isso foram palavras dele, eu tive sorte de ser criativa. Eu não sou uma pessoa difícil de lidar, e não sei como posso me descrever, eu sou legal, é o que dizem… mas é melhor não se guiar muito pelo o que dizem sobre mim, nem tudo é verdade.

Tudo okay então, candidato. Essa fase é mais uma conversa do que um teste em si, só para te conhecer melhor, perceber onde você se encaixa na nossa instituição. Temos espaço para todos, de qualquer forma! Nós vamos nos encontrar novamente, fechado? Te vejo nos palcos!

0 notes

Text

Edwin Muir the Orcadian poet, novelist and translator was born on May 15th 1887.

Muir was born on a farm in Deerness, where his mother was also born, at Hacco. In 1901, when he was 14, his father lost his farm, and the family moved to Glasgow. In quick succession his father, two brothers, and his mother died within the space of a few years. His life as a young man was a depressing experience, and involved what he viewed as a raft of unpleasant jobs in factories and offices, including working in a factory that turned bones into charcoal. He suffered psychologically in a most destructive way, although perhaps the poet of later years benefited from these experiences as much as from his Orkney 'Eden'.

Termed a philosophical, political and social poet, Muir’s poetry attempts to find meaning and pattern in life, harmony & cooperation instead of competition and conflict; popular themes include a sense of timelessness, a sense of displacement and rootlessness and innocence. He travelled in Europe with his wife and fellow writer, Willa, translating European writers such as Franz Kafka into English. The Muirs were significantly involved in the Scottish Literary Renaissance.

In 1955 he was made Norton Professor of English at Harvard University. He returned to Britain in 1956 but died in 1959 at Swaffham Prior, Cambridge, and was buried there.

A memorial bench was erected in 1962 to Muir in the idyllic village of Swanston, Edinburgh, where he spent time during the 1950s.

This poem from Muir is called Scotland's Winter.

Now the ice lays its smooth claws on the sill,

The sun looks from the hill

Helmed in his winter casket,

And sweeps his arctic sword across the sky.

The water at the mill

Sounds more hoarse and dull.

The miller's daughter walking by

With frozen fingers soldered to her basket

Seems to be knocking

Upon a hundred leagues of floor

With her light heels, and mocking

Percy and Douglas dead,

And Bruce on his burial bed,

Where he lies white as may

With wars and leprosy,

And all the kings before

This land was kingless,

And all the singers before

This land was songless,

This land that with its dead and living waits the Judgement Day.

But they, the powerless dead,

Listening can hear no more

Than a hard tapping on the floor

A little overhead

Of common heels that do not know

Whence they come or where they go

And are content

With their poor frozen life and shallow banishment.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hermann broch handbuch englisch

HERMANN BROCH HANDBUCH ENGLISCH >> DOWNLOAD LINK

vk.cc/c7jKeU

HERMANN BROCH HANDBUCH ENGLISCH >> READ ONLINE

bit.do/fSmfG

Insgeheim hatte Hermann Broch mit dem Nobelpreis gerechnet. Der 1886 in Wien Edwin Muir, der das Buch mit seiner Frau Willa ins Englische übersetzte,. Zur Bedeutung und Rezeption Hermann Brochs: Der jüdisch-österreichische Schriftsteller und Exilautor Hermann Broch (1886-1951) war nie ein Publikumsliebling Mit seiner Resolution strebte er, vergleichbar der englisch-französischen In: Kessler, Michael/ Lützeler, Paul Michael (Hg.): Hermann-Broch-Handbuch. Das Gleiche gilt für Hermann Brochs zwar weniger bekannten, um 1945 in New York zugleich auf Deutsch und Englisch als Roman zu erscheinen1 – ein Roman, September 1950 an den amerikanischen Germanisten Hermann Salinger deutlich (vgl. Broch verfügte über ordentliche Englischkenntnisse, aber Englisch wäreHermann-Broch-Handbuch () || II. Freunde und Bekannte Hermann Brochs | Kessler, Michael; Lützeler, Paul Michael | download | BookSC. Hermann Brochs Sprachkunstwerk „Der Tod des Vergil“. Hermann Broch: Philosophische Schriften. In: Hermann-Broch-Handbuch. Hrsg. v. Die „Wiener Bibliothek“ Hermann Brochs: kommentiertes Verzeichnis des rekonstruierten Bestandes/Klaus Amann; Helmut Grote. – Wien [u.a.]: Böhlau, 1990.

https://qesulihupe.tumblr.com/post/692227374115389440/revox-b226-bedienungsanleitung-medion, https://qesulihupe.tumblr.com/post/692227374115389440/revox-b226-bedienungsanleitung-medion, https://qesulihupe.tumblr.com/post/692227426967863296/einbauhandbuch-mega-rail-sl, https://hoxecibonaxa.tumblr.com/post/692227515160428544/miele-w-3903-bedienungsanleitung-7490, https://hoxecibonaxa.tumblr.com/post/692227458546761728/merbah-resort-benutzerhandbuch.

0 notes