#Viet Nam

Text

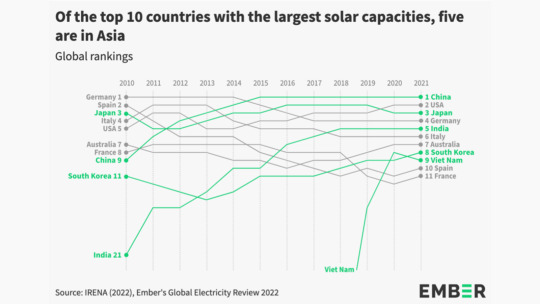

"One of the many benefits of solar power is the speed and scale at which it can be deployed. But, despite this, some states still manage to exceed expectations. Viet Nam is one such place. In 2010, the South East Asian country was ranked 196th in the world according to its solar energy capacity. By 2021, Viet Nam had climbed to ninth in the global rankings, jumping above both Spain and France, an astonishing ascendancy.

In 2018, Vietnamese solar generation was close to zero TWh, but in 2022, solar accounted for 11 percent (14 TWh) of electricity demand from January to June. The rapid growth of solar throughout Viet Nam is estimated to have saved the nation $1.7 billion in potential fossil fuel costs – and this is without factoring in the human, social and environmental harms created through burning fossil fuels.

Viet Nam’s ability to rapidly scale up solar generation over the last decade is down to a combination of factors, including supportive government intervention, a positive policy environment and international collaboration. Targeted investment in key infrastructure was essential, and worked alongside a growing demand for cheap, secure, and clean energy from Vietnamese citizens and businesses. The foundations have been set for Viet Nam to continue its rapid growth in solar, climbing further up the global rankings.

Lessons for rapid transition: How did they do it?

A generous policy mix including tax breaks and a bold feed-in tariff to enable the scaling up of solar generation and bring in new actors.

Investing in transmission and distribution to ensure that the added solar capacity can meet rising energy demand.

Sky-high demand from citizens and businesses driven by concerns over air quality and the availability of affordable household solar systems for clean, reliable and cheap electricity."

-via Rapid Transition Alliance, January 25, 2023

#vietnam#viet nam#fossil fuels#solar power#solar#clean energy#sustainability#air pollution#carbon emissions#infrastructure#asia#southeast asia#good news#hope

662 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ban Gioc waterfall, Cao Bang, Viet Nam

photo by huyen

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

Waterlilies create colorful patterns while being harvested in waist-deep water in Moc Hoa district, Long An Province, Vietnam.

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

From: Viet-nam; where East & West meet by Do-van-Minh (1968). Ph. by Nham-Ha-Phi

#viet nam#nham-ha-phi#do-van-minh#1960s#tree blossoms#vietnam#viet-nam#primavera#printemps#rural landscape#workers

338 notes

·

View notes

Link

The strong afternoon sun bears down on the coastal town of Can Thanh in southern Vietnam, but inside Lăng Ông Thủy Tướng—a single-story, pale-yellow building on the town’s shoreline—it is cool. Diffused sunlight illuminates the main hall, and the air is laden with the woody aroma of burning incense. A lone man, most likely a fisherman, enters the hall, walks toward a 20-meter baleen whale skeleton displayed in a glass case, and folds his hands in deep reverence.

Lăng Ông Thủy Tướng—the temple to the god of the sea—is one of 1,000 or more such shrines on Vietnam’s 3,260-kilometer coastline. At these temples, which come in varying sizes and configurations but all house whale bones, fishermen worship in hopes that their prayers will be carried to Cá Ông, the whale spirit, and they will be blessed with a safe fishing trip and a bountiful catch. Close relatives of fishermen also visit to light candles, burn incense, and pray for the safety of their loved one, sometimes offering fruit and money, hoping their prayers are heard.

For over two centuries, fishing communities along Vietnam’s central and southern coastlines have built places of worship to honor the dead cetaceans washing up on their shores. From large ornate structures to simple graves with headstones to small wooden shoebox-sized shrines bedecked with incense and flowers, these “whale temples” are a centuries-old part of the country’s cultural history, but they also house evidence of its natural history. For this reason, Vu Long, cofounder of the Ho Chi Minh City–based Center for Biodiversity Conservation and Endangered Species (CBES), a grassroots wildlife conservation organization also involved with marine mammal research, is visiting Lăng Ông Thủy Tướng. For marine mammal researchers like Vu who are faced with extremely limited resources and a lack of funding, these whale temples—some holding dozens of skeletons—prove an invaluable source of information regarding the current and historical diversity and distribution of marine mammals in Vietnam. “Besides being a unique aspect of Vietnamese culture, whale temples are a great supplementary source of information for our research,” says Vu, who, along with his team at CBES, collects data about marine mammals in Vietnam via boat-based surveys and by monitoring cetacean strandings.

Vu sits outside the temple entrance with Lê Văn No, a 71-year-old retired fisherman who has served as a volunteer caretaker of the temple for over 20 years. Lê cleans the temple daily, and, along with others, decorates it for special occasions, such as the annual Nghinh Ông (whale worship) festival celebrated in the eighth month of the lunar calendar.

Lăng Ông Thủy Tướng is one of the country’s older known temples, the original shrine site dating back to 1805, and Lê is eager to share the story of the whale behind glass, just one of the dozens of skeletons associated with this shrine. (The others are piled in one of the temple’s rooms or stored in one of the 17 coffin-like bins located at a nearby property.) “Local people found this whale with bullet wounds,” says Lê. “It was another victim of the [Vietnam] war.”

He shows Vu a discolored black-and-white photograph from 1971 and recounts when the whale carcass was found floating in the waters near the temple. Lê was only 20 years old then but recalls that the dead animal—about the length of 13 park benches—was too large to be moved by human effort alone. So the community used a small motorboat to drag the carcass to the nearby mangroves. It decomposed there for several months before its bones were moved to the temple, where it became a focal point for worship.

In Da Nang, about 1,000 kilometers north of Can Thanh, 35-year-old fisherman Trần Văn Mùi, has prayed at the Vạn Nam Thọ temple since he was a child. In an earlier interview conducted by Vu, he learned that Trần’s faith in the miraculous powers of whales and whale temples was reinforced in 2005, when he and his fishing crew avoided a storm that the weather forecast had failed to predict. At sea, Trần’s crew observed a whale surface and head toward shore, a sighting they took as an omen from Cá Ông, the whale spirit. They sailed home earlier than planned. In doing so, Trần believes, they avoided the storm, and their lives were saved.

According to Vu, this profound faith in the mystical power of whales can be traced back to three different origin stories. One is rooted in Hinduism and another in Buddhism, but the one that is most widely believed in Vietnam comes from the country’s history. In the 18th century, Nguyễn Ánh, a powerful warlord, was waging a 20-plus-year war against his enemies. On the verge of getting captured, he prayed to the gods for a way to escape. At that moment, two whales rose from the sea and carried him and his flagship away from the enemy, thus ensuring his safety. In 1802, Nguyễn Ánh became the first emperor of a unified Vietnamese kingdom, the precursor to modern Vietnam. As a token of gratitude to the gods, Nguyễn Ánh declared that all whales in Vietnamese waters must be worshipped as gods.

In keeping with this historical story, fishermen consider it their duty to bring a whale they find floating or catch accidentally to shore and conduct a burial ceremony—on the beach or in a dedicated whale graveyard. After three years or so, they exhume the bones and transfer them to the community’s whale temple. It’s a reverence akin to that shown for a parent or an elder. “When fishermen see a stranded whale, they believe that the animal has chosen their village as its final resting place,” explains Vu. “They feel honored and obligated to give it a proper burial ceremony.”

Years, decades, and in some places even centuries of skeletons collected at temples have resulted in a treasure trove of information about Vietnam’s cetaceans, not just whales. (If fishermen see a dead animal with a horizontal tail and a blowhole, they usually consider it a whale. As a result, the temples tend to have a mix of whale, dolphin, and porpoise bones.)

Vu, who has studied the marine mammals of Vietnam for a decade, is one of the authors of a 2021 paper that highlights the wealth of information inside whale temples. He emphasizes the need for a multidisciplinary approach—including social scientists and cultural historians, for instance—to studying them.

Over the years, Vu and his team have located more than 200 temples. For their recent paper, they visited 18 whale temples on Vietnam’s central coast, where they identified and measured 140 marine mammal skeletons from 15 species. To determine the species, they examined the dentition and took 10 specific skull measurements.

Some whale temples studied for the paper had acquired just a single carcass since the 19th century, others received a dead dolphin or whale every month, often of differing species. Several of the species they found in the temples were not seen on their boat surveys, explains Vu. One example was the data deficient Omura’s whale, a whale that was first described by Japanese scientists in 2003. Vu and his colleagues found two specimens in their whale temple survey. These finds brought the species’ record in Vietnam to five.

Much to their surprise, Vu and his coauthors also came across three dugong skulls during their visit to two whale temples in the northern part of the central coast. In recent times, the presence of dugongs has only been confirmed in southwestern Vietnam and the Con Dao archipelago, located to the southeast of the country. So this observation sheds new light on their historical distribution. They think the skulls date back to the 1990s through to the early 2000s, indicating that the dugongs’ local extinction is recent. Vu also theorizes that the local extinction of dugongs was most likely caused by human activities like hunting, by-catch, and the destruction of their seagrass habitats.

Emma Carroll, a whale researcher and an associate professor at the University of Auckland (Waipapa Taumata Rau) in New Zealand, says that “societies suffer from shifting baselines, the idea that what we see now is normal, as there’s no collective memory of the biodiversity that thrived even in the recent past. The collections within these temples are reminders of how much has changed, for example, the shift in dugong distribution that was revealed [in Vu’s paper].”

She adds that the collection of bones holds a unique archive of species diversity, population abundance, and distribution information that can be revealed with modern genetic analysis techniques, but emphasizes that these studies should only happen with community support and approval.

Vu and his team have continued documenting whale temples even after the publication of the paper. To date, they have identified 25 cetacean species in whale temples, including rare and endangered species like sperm whales. In comparison, they’ve identified only 20 cetacean species via the stranding monitoring done over the past five years and just three species in their boat-based surveys. These results underscore the importance of whale temples as information storehouses about Vietnam’s cetaceans. Vu hopes that the temples will, in the long run, become key centers for interaction with fishermen and awareness campaigns about sustainable fishing.

For now, Vu and his team still have hundreds of whale temples to document. But they are unfazed. By analyzing and dating the specimens found in these repositories, the researchers are confident of narrowing the information gaps that exist around Vietnam’s marine mammal diversity and its distribution over time.

Back at Lăng Ông Thủy Tướng, as Vu and Lê chat, a pair of curious Vietnamese tourists wander up to the temple entrance. Lê slowly rises from his chair, and walks over to greet them and share whale worship stories with this eager, younger audien

610 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ hinewin

Enjoy our curated content? You can support us here.

#viet nam#vietnam#asia#travel#wanderlust#explore#curators on tumblr#cable car#forest#forestcore#trees#nature#naturecore#landscapes#travel photography#foggy aesthetic#foggy landscape#li_destinations

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr users and staff (if I can reach them) I kind of need a few Vietnamese or hell anywhere to sign this petition. This is a petition to legalize homosexual marriage in Vietnam and so far it's getting more people signing it than any lgbt+ stuff I've seen in this small country.

https://toidongy.vn/?fbclid=IwAR3Hcal-TjLOex0wcqtoWo33oVinfS7MPBWCULd-0aGxP00BbKVHbIzGyQ8

I have already signed it and it just ask for your email and your phone number (I forgot to take a screenshot of it), and you can leave a little note below if you want. Once you're done all you need to do is verify you are not a robot and click the button right bellow the verify button and it will show this up

That's when you're done, If you have any questions you can ask down the comments or in the ask box. Thank you, have a nice day/night/evening/afternoon.

#chat with bb#lgbtqia#lgbtq community#lgbtq#gay#queer#lesbian#transgender#bisexual#pansexual#nonbinary#asexual#aromantic#intersex#fandom#viet nam#petition

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A new species of Paracortina from a Vietnamese cave, with remarkable secondary sexual characters in males (Callipodida, Paracortinidae)

Anh D. Nguyen, Pavel Stoev, Lien T. P. Nguyen, Tam T. Vu

Abstract

A new millipede species, Paracortina kyrang sp. nov., is described from a cave in Cao Bang Province, northern Vietnam.

The new species is diagnosed by having an extraordinarily long projection on the head of males, reduced eyes, a gonocoxite with two processes, a long and slender gonotelopodite with two long, clavate prefemoroidal processes densely covered with long macrosetae apically, and with a distal, reverse, short spine on mesal side, and a rather sinuous distal part of the telopodite.

This is the third species of the genus that is known from Vietnam. A brief comparison of some secondary sexual characters is made.

Read the paper here:

https://zookeys.pensoft.net/article/99651/

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

điều làm mình yêu Hà Nội nhất chính là: "mùa nào thức nấy."

bạn ăn món ăn theo mùa; uống đồ uống theo mùa; mặc trang phục theo mùa; cắm những bông hoa, bày những loại trái theo mùa.

Winter in HaNoi.

Trịnh coffee.

photos by huyen&T

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

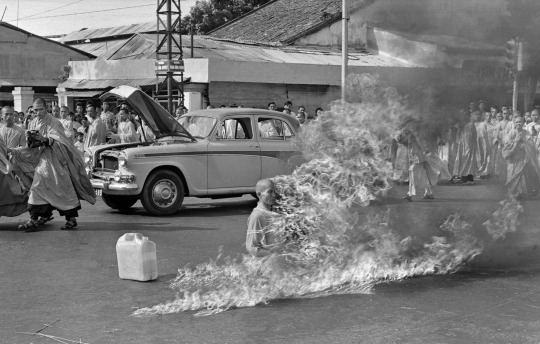

Malcolm Browne - The Burning Monk (1963) Thích Quảng Đức protesting the persecution of Buddists by altruistic suicide.

Browne photographed Vietnamese Mahayana Buddhist monk Quảng Đức's self-immolation on a busy intersection in Saigon, during which he remained perfectly still. "I just kept shooting and shooting and shooting and that protected me from the horror of the thing."

“No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.” --President John F. Kennedy

Self-immolation (the word immolation originally meant "killing a sacrificial victim; sacrifice"), is tolerated by some elements of Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism, and it has been practiced for many centuries for various reasons, including political protest.

Browne won a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting and received many job offers, eventually leaving the AP in 1965.

Malcolm Browne: The Story Behind The Burning Monk

The procession from the monastery to central Saigon - Malcolm Browne–AP

"The monks were very much aware of the result that an immolation was likely to have. So by the time I got to the pagoda where all of this was being organized, it was already underway—the monks and nuns were chanting a type of chant that’s very common at funerals and so forth. At a signal from the leader, they all started out into the street and headed toward the central part of Saigon on foot. When we reached there, the monks quickly formed a circle around a precise intersection of two main streets in Saigon. A car drove up. Two young monks got out of it. An older monk, leaning a little bit on one of the younger ones, also got out. He headed right for the center of the intersection. The two young monks brought up a plastic jerry can, which proved to be gasoline. As soon as he seated himself, they poured the liquid all over him. He got out a matchbook, lighted it, and dropped it in his lap and was immediately engulfed in flames. Everybody that witnessed this was horrified. It was every bit as bad as I could have expected." -- Malcolm Browne

Buddhist monk Quang Duc emerged from a car and sat in the center of the intersection while a younger monk poured gasoline over him. Malcolm Browne–AP

"I don’t know exactly when he died because you couldn’t tell from his features or voice or anything. He never yelled out in pain. His face seemed to remain fairly calm until it was so blackened by the flames that you couldn’t make it out anymore." -- Malcolm Browne

In the air was the smell of burning human flesh; human beings burn surprisingly quickly. Behind me I could hear the sobbing of the Vietnamese who were now gathering. I was too shocked to cry, too confused to take notes or ask questions, too bewildered to even think.

Later we learned that the man was a priest named Thich Quang Duc who had come to the square as part of a Buddhist procession, had been doused with gasoline by two other priests, had then assumed the cross-legged "lotus" position and had set a match to himself. As he burned he never moved a muscle, never uttered a sound, his outward composure in sharp contrast to the wailing people around him. -- David Halberstam, American journalist who was present at the scene

Monuments to Thich Quang Duc, the Buddhist monk whose self-immolation hit the headlines of the world in 1963.

Self-immolation has been a Buddhist and Hindu practice for many centuries for various reasons.

A Hindu widow burning herself with the corpse of her husband, 1657

#david halberstam#malcolm browne#Thich Quang Duc#self immolation#mahayana buddhist#buddhist monk#buddhist#hindu#viet nam#Pulitzer Prize#historical photos#phtography#award winning photography#monument#statue

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Viet Nam

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Hoi An Ancient Town is a popular destination in Vietnam, with narrow bustling streets full of historic monuments and traditional lanterns, charming shops and restaurants, as well as beach resorts close by.

Among such vibrant places of interest, a small museum dedicated to local archaeology is not likely to attract crowds of tourists, especially when there are other museums focusing on Hoi An’s history and cultural lifestyles. Nevertheless, the Museum of Sa Huỳnh Culture offers a fascinating look into Vietnam’s Iron Age, which flourished in the region between the 10th century BCE and the 4th century CE.

Named after a small village in Quảng Ngãi Province where the first site was found in 1909, Sa Huỳnh culture is known for its ironware, gemstone beads, and terra-cotta burial jars, not unlike those found in the Philippines.

It is known that Sa Huỳnh, the Philippines, as well as Taiwan, Borneo, and Thailand, were connected along an ancient trade route. Sa Huỳnh is one of the few cultures that made ling-ling-o, a type of ancient ring-shaped amulet in the ancient Philippines, using jade imported from Taiwan.

Founded in 1994, the Museum of Sa Huỳnh Culture is home to nearly 1,000 locally sourced artifacts, the largest of its kind. One of its major highlights is the exhibit of burial jars on the second floor.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incense burner, Vietnam (Hai Zhong Province, Hong River delta), 1635, Metropolitan Museum, NYC

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vietnam (North), 12xu stamps of 1965 commemorating the 500th F-105 US fighter plane shot down over Vietnam.

4 notes

·

View notes