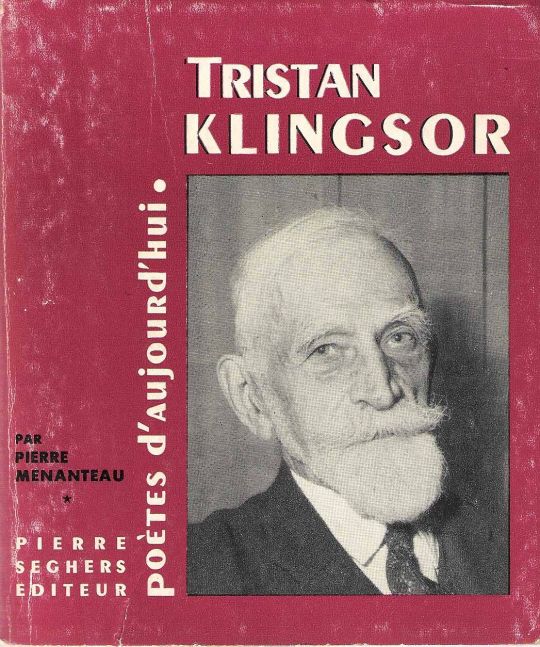

#Tristan Klingsor

Photo

Tristan Klingsor (deceased)

Gender: Male

Sexuality: Gay

DOB: 8 August 1874

RIP: 3 August 1966

Ethnicity: White - French

Occupation: Poet, musician, artist, art critic

#Tristan Klingsor#lgbt history#lgbt#lgbtq#mlm#male#gay#1874#rip#historical#white#french#poet#musician#artist#art critic#writer

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

LA URRACA

Cesó el aguacero; ríe el viejo sol

en la pista rosa y blanca,

mas quedan aún gotas en las ramas

del gris manzano.

La tartana rola como una loca

y el eje sin untar chilla;

en el prado la urraca sacude sus plumas

y echa a volar.

Mi vida es igual:

cierto que el antiguo dolor dormita

y el pasado va perdiendo las hojas;

pero apunta tal vez en los párpados llanto

y viste mi alma medio luto,

como esa urraca.

*

LA PIE

L’averse a cessé ; le vieux soleil rit

Sur la route rose et blanche

Mais il reste encor des gouttes aux branches

Du pommier gris.

La carriole roule comme une folle

Et l’essieu mal huilé crie ;

La pie secoue ses plumes dans la prairie

Puis s’envole.

Ma vie est ainsi :

Certes la douleur ancienne est assoupie

Et le passé peu à peu s’effeuille ;

Mais des larmes pourtant pointent parfois aux cils

Et mon cœur reste en demi-deuil,

Comme cette pie.

Tristan Klingsor

di-versión©ochoislas

#Tristan Klingsor#literatura francesa#poesía fantasista#impresión#urraca#lluvia#ánimo#duelo#di-versiones©ochoislas

0 notes

Text

Le Drapeau du Sacré–Cœur, 1919. Maurice Desvallières.

L’art français depuis vingt ans la peinture

Tristan Klingsor

Paris: F. Rieder et cie Éditeurs, 1921.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Libretto wagner pdf

LIBRETTO WAGNER PDF >>Download (Descargar)

vk.cc/c7jKeU

LIBRETTO WAGNER PDF >> Leer en línea

bit.do/fSmfG

lohengrin leyenda

montsalvat grial

parsifal wagner argumento

lohengrin libreto

parsifal wagner wikipedia

klingsor y kundry

la herida de amfortasortrud

LIBRETTO ESPAÑOL. PRELUDIO ACTO I (La escena se desarrolla en el territorio de los Caballeros del Grial y su castillo, Monsalvat. The directing team takes a subtly tongue-in-cheek approach to the magical opera that stays faithful to Wagner's libretto while allowing for room to laugh at its Castillo de Tristan, en Bretaña 29 TRISTAN (lujo) 1/2/08 11:06 Página 30 Tristan und Isolde | Libreto Richard Wagner. Retrato fotográfico de Pierre Petit.En frente se hallan los condes de Brabante, sus nobles, soldados y gentes, dirigidos por Friedrich de Telramund, junto al que se halla Ortrud. En el centro delParsifal -- Libretto español - Wagnermaniawagnermania.com › parsifal › espanolwagnermania.com › parsifal › espanol 31 mar 2020 — Libreto. Richard Wagner basado en Aus den. Memorien des Herren von Schnabelewopski. (Las notas del señor de Schnabelewopski) de. por R Wagner · Mencionado por 3 — ios comentarios de este libreto son propiedad de Celestino Gomóles quien perseguirá ante la ley al que lo En suma, El oro del Rhin es digno de Wágner. por AF Araújo · 2014 — 02 - Alberto Filipe Araujo - Jose Augusto Ribeiro.pdf (168.4Kb) El libreto Parsifal (1882) de Richard Wagner es un drama con resonancias simbólicas 3.2. LA TRADUCCIÓN DEL LIBRETO 13. 4. EL TRADUCTOR DE ÓPERA 16 4.1. TRADUCIR A WAGNER 18. 5. RICHARD WAGNER 22 5.1. VIDA Y OBRA DE WAGNER 22

https://www.tumblr.com/kefulimumu/698356652192202752/tbi-treatment-pdf, https://www.tumblr.com/kefulimumu/698356953572917248/vivienda-sustentable-pdf, https://www.tumblr.com/kefulimumu/698357356847906817/reagent-chemistry-pdf-worksheet, https://www.tumblr.com/kefulimumu/698356489009725440/propertyplaceholderconfigurer-example-multiple, https://www.tumblr.com/kefulimumu/698357227401232384/bwv-1007-prelude-pdf.

0 notes

Quote

« Un homme sans amour est un dormeur sans rêve »,

Dit-elle ; il posa son bonnet de Syrie,

Ôta sa pipe de ses lèvres

Et sourit.

Il avait déjà dans sa barbe d’or

Des fils d’argent, mais ses yeux étaient comme

Ceux des rois mages qu’on adore

Pour avoir cueilli le bonheur des hommes.

Son manteau de soie et ses manches

Étaient brochés de chimères agriffées

Avec des revers d’hermine blanche

Et des dentelles comme des collerettes de fées.

Sa cathèdre toute en bois de rose

Était sculptée de licornes doubles

Où dans sa grave pose

D’enchanteur, s’appuyaient son chef et ses coudes.

Il sourit. Il sourit comme un roi mage

En sa barbe blonde fleurie de givre,

Leva les yeux du vieux missel d’images

Et ses doigts tournèrent la page du livre.

« Un homme sans amour est un dormeur sans rêve »,

Reprit-elle... Et Klingsor songeant

L’ayant très amicalement baisée aux lèvres

Se remit à fumer son calumet d’argent.

Tristan Klingsor, Squelettes fleuris

1 note

·

View note

Text

„Der Rosenkavalier“, Staatsoper Berlin, 1932. From left to right: Theodor Scheidl (1880-1949, Baron Ochs auf Lerchenau), Fritz Krenn (1887-1963, Faninal) and Marta Fuchs (1898-1974, Octavian).

Theodor Scheidl (3 August 1880 – 22 April 1959) was an Austrian baritone, athlete, and academic teacher. In 1906, Scheidl began to study voice with Alois Grienauer. He made his debut in 1910 at the Wiener Volksoper as the Heerrufer in Wagner's Lohengrin. He worked in Stuttgart from 1913 to 1921. He performed there in several world premieres, in 1913 in Ulenspiegel by Walter Braunfels, in 1917 in Siegfried Wagner's An allem ist Hütchen schuld!, and in 1919 in Ture Rangström's Die Kronenbraut (The Crown Bride). From 1921 to 1932, Scheidl was a member of the Berliner Staatsoper, He appeared in world premieres again, in 1922 in Franz Schmidt's Fredigundis, 1928 in Franz Schreker's Der singende Teufel, and in 1928 as the Young Columbus in Darius Milhaud's Christophe Colomb. Afterwards he worked at the State Opera in Prague. Scheidl appeared at the Bayreuth Festival first in 1914, as Klingsor in Parsifal and Donner in Das Rheingold. He returned in 1924 to appear as Amfortas in Parsifal, repeated in 1925 and 1928, and was Kurwenal in Tristan und Isolde in 1927. He appeared as a guest at the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm, the Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam, La Scala in Milan, and the Vienna State Opera, among others. Scheidl retired from the stage in 1937 and then taught at the Musikhochschule München. From 1944, he was a voice teacher in Tübingen. He appeared on stage occasionally, notably as Scarpia in Puccini's Tosca at the Stuttgart Opera in 1955, to celebrate his 75th birthday. Scheidl died in Tübingen at the age of 78.

Marta Fuchs (January 1, 1898 - September 22, 1974) was a German concert and operatic soprano. Studied at the Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst, the College of Music in Stuttgart. In 1923 at the age of 25, she began her career as a soprano singing concerts and oratories. After undergoing further voice and drama training in Stuttgart, she made her debut as an operatic soprano at the state theatre in Aachen in 1928 with Gluck's Orpheus, Azucena in Verdi's Troubadour and with Carmen. In 1930 she was engaged by the Staatsoper in Dresden. After retraining from an alto to a high dramatic soprano, she sang, among other parts, Marschallin, Isolde, Brünnhilde, Arabella, and Fidelio. From 1935 onwards she was also part of the ensemble of the Berlin State Opera und des Deutsche Oper Berlin and appeared as guest in Amsterdam, Prague, Paris, London, Florence and Vienna. From 1933 to 1942, she was a central figure at the Bayreuther Festspiele, where she played Isolde, Kundry and especially Brünnhilde. On February 20, 1935 she played the part of Maria Tudor in the premiere of Rudolf Wagner-Régeny's Der Günstling. In 1941, she sang Fidelio-Leonore at the Rome Opera. She gave guest performances at Bayreuth (e.g. Kundry in Parsifal, 1938), Amsterdam, Paris, London, Berlin, Wien and Salzburg.

#Der Rosenkavalier#Richard Strauss#Theodor Scheidl#Marta Fuchs#Richard Wagner#Giuseppe Verdi#Giacomo Meyerbeer#La Scala#Giacomo Puccini#Georg Friedrich Händel#Johannes Brahms#Ludwig van Beethoven#Christoph Willibald Gluck#Georges Bizet

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Der fliegende Holländer (Met, 2020)

My goodness, this piece has issues. I’m surprised to note that this was my fourth Dutchman, since it still feels foreign to me, but this time through what really struck me is how foreign the piece is to what I think of as Wagner.

As with Rienzi (which I have seen only once in the DOB’s heavily bowlderised version), it seems that the figure of “opera” that Wagner rails against in the theoretical treatises of the early 1850s is not really the Italian opera represented for us by Donizetti and Bellini, nor the French now represented (when at all) by Meyerbeer. Rather, it is that of his own failings in those styles. I’d forgotten how many concerted ensembles there are here, and they’re almost without exception incomprehensible. It was also amusing when the score lurched inelegantly into something that wanted to be a “number”, sounding much more “Italianate”, as with much of Daland’s music. I was also surprised at how clumsy a lot of the text setting was. The mature Wagner has clumsy texts, yes, but not clumsy setting. The dramaturgy is also extremely dodgy. The later Wagner is often long, but seldom flabby, here he doesn’t really know how to create a plot from the outline.

I got the sense that Gergiev wasn’t helping much, with a curious lack of apparent direction (as in, teleology) a lot of the time. The clumsiness of the writing didn’t help, but there was also surprisingly much dodgy diction, particularly from Nikitin (whose Klingsor at least I’ve seen and with which I don’t recall having such problems) and Skorokhodov (although Erik is so thankless, one might feel inclined to charitableness).

It wasn’t all bad by any means, neither the writing nor the performance. As superfluous dramatically as it is, the scene with the ghost ship is tremendously effective musically (one can see why he would build on such spatial effects; the shepherd in Tannhäuser particularly came to mind). Girard, as with his Parsifal, provides beautiful stage pictures, working with at least the same choreographer and projection designer, although here perhaps with less insight and a different caliber of cast, causing the Personregie to suffer. Potrillo’s clear and beautiful singing placed the Steuermann is that category of wonderful small tenor roles in the Wagner canon (the two in Tristan, perhaps David). I liked Selig’s Daland, and Kampe did what she could with Senta (in a credible house debut, although it’s incredible to me that she hasn’t sung there before), although she could not overcome the sheer awkwardness of the writing, even in the ballad.

#normallywatches#opera tag#Der fliegende Holländer#Richard Wagner#François Girard#Valery Gergiev#Anja Kampe#Franz-Josef Selig#Evgeny Nikitin#Mihoko Fujimura#Peter Flaherty#Carolyn Choa

1 note

·

View note

Text

Can we please stop reading Wagner's operas as complete sausage fests?

(Cross-posting from /r/opera for the five people browsing the #opera tag on tumblr)

Inflammatory title, check. Typing this fresh out of the shower inflamed with righteous indignation, check. References to YouTube comments, check. That's right, it's rant-time (or, as Wagner calls it, "act 2").

So this is something that has been on my mind a lot but that I've never really bothered to write down. I don't think this will come as a surprise to most of the people on here, so this is gonna be somewhat self-indulgent. Obviously, big shout-out to the 2005 Copenhagen Ring, which was my first introduction to Wagner.

In a lot of the literature, and certainly in the popular imagination (hello there, angry YouTube commentors), Wagner is all about the men. *Meistersinger* productions almost always hinge on the director's perspective on Hans Sachs and what a cad he is. The *Ring* is usually told as either the story of Wotan, whether he be a visionary master manipulator or a villain in disguise. *Tannhäuser* is about Heinrich dithering about for three hours like a latter-day Hamlet who can't decide between Betty and Veronica (wait, what?). This is not to say Wagner's big female characters -- Brünnhilde and Kundry being the prime examples -- don't receive attention in those productions or analyses. But they're usually ancillaries of the men, in some way or another, and not the focal points of the action.

But that's not at all what we can see in the libretti themselves, let alone the music! If anything, I'd argue that in all of Wagner's mature works -- Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, Tristan, Meistersinger, the Ring and probably Parsifal -- it's the women that drive the plot, and the women that make the most use of their agency.

I think the best example for this is probably Walküre, and in fact listening to the first two acts this morning brought this on. When the Copenhagen Ring had Sieglinde pull Nothung from the ash tree rather than Siegmund, I saw a lot of reviewers tut-tutting. According to a not very scientific study of the comments on the YouTube upload, that seems to be a point of more contention than the deaths of Loge and Alberich in that production, or Hunding getting away scots-free. I note that the Met Ring has the twins pull out Nothung together, hand in hand, which is cute and doesn't seem to arouse nearly as much dissension.

But in fact, Sieglinde is far from the helpless damsel in distress that some people seem to want to paint her as. Hell, her very first line goes: "A stranger -- him, I must ask." The clear implication that she has some sort of plan in mind -- which, though never spelled out, becomes pretty clear over the course of the first act -- doesn't exactly characterise her as helpless victim waiting for her saviour. It is Sieglinde who, at risk to her own safety, forces Hunding to grant Siegmund shelter by literally calling him a coward. Later, it is Sieglinde who -- on her own initiative -- drugs Hunding and directs Siegmund to the sword, not just to save him but also herself. Rather than Siegmund saving Sieglinde, this is a transaction between equals: Sieglinde gives Siegmund the means to defend himself from certain death at Hunding's hands, and in return Siegmund bodily protects Sieglinde from her abusive husband.

Throughout the act, the equality between the twins is emphasised. In part, of course, that's for foreshadowing that sweet, sweet twincest, but one line always gives me pause:

HUNDING

Wie gleicht er dem Weibe!

Der gleißende Wurm

glänzt auch ihm aus dem Auge.

I've seen some pretty bizarre translations of that (that deceitful serpent, really?), but I think this might be the most literal:

How like to the woman is he!

The same gleaming (radiant? bright? searing?) worm (almost definitely: dragon rather than earthworm, cf. Fafner)

shines in his eye.

I don't really think you can get much clearer on what kind of temperament Wagner had in mind for both Wälsung twins than comparing them to a freaking dragon.

Later on, too, it's Sieglinde who first realises just who this dashingly handsome stranger is and goes "eh, fuck it" and proceeds to basically spell it out to her brother. By this point, we've seen Sieglinde pretty much run the first act, directing events to her advantage from a position of supreme weakness. No matter which of the twins draws Nothung from the tree, I think it's pretty clear that the first act is Sieglinde's self-actualisation and emancipation more than anything else.

The theme continues in acts 2 and 3, in my opinion. Sieglinde takes the backseat here as the overarching mythological plot dominates the action, and the focus shifts to two other female characters: Fricka and Brünnhilde. Now Fricka seems to be positioned perfectly to be played under the "shrewish, overbearing wife" trope who just doesn't understand Wotan's greatness and is keeping him down, man. Wotan and Brünnhilde certainly seem to share that opinion in how they talk about her. But regardless of how she is portrayed on stage, Fricka completely dominates the confrontation with Wotan despite the supposed master-manipulator and patriarch's sweet romantic ideas on how to deal with the Wälsung twins. This is one sharp lady, and she doesn't waste a second before reminding Wotan that he's bound to enforce the divine law she set down. Musically, too, Fricka's sharp soprano lines seem to easily overpower Wotan's explanations in all the recordings I've heard, another common theme.

Brünnhilde of course is the poster-child for any feminist reading of the Ring for obvious reasons. Not only is she, apparently, her mother's equal in wisdom and magic (so says Erda, at least -- later on Brünnhilde bitterly mocks her lack of wisdom, so your mileage may vary). Over the course of the three operas she's in, she

wilfully defies Wotan's orders despite being literally created as his instrument in attempting to save Siegmund

convinces Sieglinde to live and (on the day of his conception, most likely) bestows a seriously programmatic name on her son, with the clear implication that she's doing this as her own way of fixing Wotan's broken master plan

transforms her punishment into an unishment by tricking Wotan into letting her set the conditions for her spouse-to-be, and it's pretty clear from the swelling Siegfried motif just whom she has in mind

musically overpowers brash Siegfried not once, but twice (the love duet and the oath scene in Götterdämmerung) -- I don't think it's a coincidence that Brünnhilde enters Siegfried fresh and ready to shatter every glass pane from Walhall to Niflheim while Siegfried himself has something like three hours of intensive singing behind him

hands out magic items and boons to a departing Siegfried like a mellow dungeon master just before a big-ass boss fight

after being forced into marrying Gunther, immediately turns around and moves to take down Siegfried hard, including by making alliances of convenience with her direct personal enemies Gunther and Hagen. No lovesick puppy here.

burns down the fucking world and kills all the gods

So much for the Ring (haven't touched on Gutrune and Waltraute, who I also think get a bad rap as an uninvolved accessory to her brothers' plot respectively a walking flying plot device). It's not that different in Wagner's other operas, but I'll run through them more curtly.

Tannhäuser: Elisabeth shuts down a mob of angry men about to lynch Heinrich, then cleverly leverages her reputation for piety to give him a way out that will, at the very least, save his life and has a chance of restoring him to the court's good graces. By contrast, Heinrich himself doesn't really *do* all that much.

Lohengrin: Ortrud runs the whole show here, and she would have gotten away with it too if not for those meddling grail knights! Telramund is something of a tool by comparison who doesn't even seem to be aware his wife is manipulating him. Elsa comes off as something of an ingenue, but she's got a will of her own and I like to headcanon that much of her behaviour in act 1 is deliberately performing saintlyhood and Christian mysticism as a legal defense strategy. Sure, a grail knight does come along, but if he hadn't there are worse ways to be perceived by the audience than a consumptive martyr. Big shoutout to Carolyn Walker Bynum's Holy Feast and Holy Fast here, aka the grossest book about medieval Christianity I've had the pleasure to read.

Tristan: sheesh, it's Tristan. Nothing much happens but what little plot there is is set in motion by Isolde deciding to avenge her late husband and kill herself to avoid to unwelcome marriage to a political and dynastic enemy. (Then the date rape drugs come out.)

Meistersinger: Obviously Hans Sachs gets most of the credit for plotting, but really, most of what he does seems to be prompted by Eva at least in part. Realising that her father has gone insane, she uses her limited agency to make the best of a bad situation by first trying to make Walther a Meistersinger (roping in Lene and David) despite his eminent incompetence and psychopathic temperament, then settle for a friend if not a lover by encouraging Hans Sachs to woo her instead. She also manages to keep Walther from murdering anyone on-stage which is quite a feat.

Parsifal: Like with Tristan, there isn't too much plot in the traditional sense, and the characters are hyperstylised archetypes -- excepting Kundry, who is of course one of the most multilayered and complex characters in all of opera (which ... isn't saying much, but still). While Kundry doesn't do all that much to drive the action on-stage, it seems to me she's expressing her agency by helping the grail knights as an attempt at restitution and trying hard to subvert Klingsor's magically-binding orders to the end of her own redemption.

So, yeah. Wagner may have had a massive thing for muscular pretty boys with big swords, but it's really the women who drive the plots and tell the muscular pretty boys what to do, and I wish more directors / reviewers / etc. would pay closer attention to that. Rant over.

TL,DR: just because Wagner was an antisemitic shithead, that doesn't mean he wasn't a crypto-proto-feminist!

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

L'INDIFFERENT

Tes yeux sont doux comme

ceux d’une fille,

jeune étranger,

et la courbe fine

de ton beau visage de duvet ombragé

est plus séduisante encore de ligne.

Ta lèvre chante sur le pas de ma porte

une langue inconnue et charmante

comme une musique fausse...

Entre ! et que mon vin te réconforte...

Mais non, tu passes

et de mon seuil je te vois t’éloigner

me faisant un dernier geste avec grâce

et la hanche légèrement ployée

par ta démarche féminine et lasse...

TRISTAN KLINGSOR (pseudo de Léon Leclère)

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Several kinds of fluid enter the body in Wagner’s stories but in only one form does fluid leave it, blood, and this in male bodies only. Women have bloodless deaths: usually they simply expire, abruptly (Elsa, Elisabeth, Isolde, Kundry) or they immolate themselves, in water (Senta) or in fire (Brunnhilde). Only men bleed – bleed to death. (Therefore it doesn’t seem too fanciful to regard semen as subsumed, metaphorically, under blood.) Though Wagner makes the prostrate, punctured, haemorrhaging male body the result of some epic combat, there is usually an erotic wound behind the one inflicted by spear and sword. Love as experienced by men, in both Tristan and Isoldeand Parsifal, is tantamount to a wound. Isolde had healed Tristan but Tristan had fallen in love with Isolde; Wagner’s way of signalling the emotional necessity of a new physical wound is to make it, shockingly, virtually self-inflicted. (Tristan drops his sword at the end of Act Two and lets the treacherous Melot run him through.) Amfortas had already been seduced by Kundry – Klingsor’s spear just made that wound literal.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Das Mitleid secondo Elfo Kirill

Das Mitleid secondo Elfo Kirill

Così come Sehnen lo è per Tristan und Isolde e Wahn per Meistersinger (quanto meno nell’Atto III), anche Parsifal è caratterizzato da una parola chiave. Mitleid, approssimativamente tradotto compassione, è infatti il concetto focale dal quale muove il libretto del Buehnenweihfestspiel. Il percorso iniziatico che der reine Tor dovrà affrontare durch Mitleid wissend ci riporta al primigenio…

View On WordPress

#Amfortas#Audi#Baselitz#Fanciulle Fiore#Gatti#Gerhaher#Girard#Graal#Gurnemanz#Kaufmann#Klingsor#Koch#Kundry#Mitleid#Pape#Parsifal#Petrenko#Schopenhauer#Stemme#Tristan#Tristano ed Isotta

0 notes

Text

The Metropolitan Opera’s Fill-In Dutchman: Evgeny Nikitin

When the star bass-baritone Bryn Terfel broke his ankle last month and withdrew from the Metropolitan Opera’s upcoming new production of Wagner’s “Der Fliegende Holländer” (“The Flying Dutchman”), it left the company with a big hole to fill, five weeks before opening night on March 2.

But the Met announced on Tuesday that it had found its new Dutchman: the Russian bass-baritone Evgeny Nikitin. Mr. Nikitin has appeared at the Met recently in several Wagner operas, including as Kurwenal in a new “Tristan und Isolde” that opened the season in 2016; as Klingsor in a “Parsifal” production directed by François Girard, who is also staging the new “Holländer,” in 2013 and 2018; and as Gunther in “Götterdämmerung” last year. This past New Year’s Eve, he appeared in a gala performance as Scarpia in Act I of Puccini’s “Tosca,” opposite Anna Netrebko.

But anchoring the new “Holländer” and filling in for Mr. Terfel — a beloved star who was supposed to be returning to the company for the first time in nearly eight years — will be Mr. Nikitin’s highest-profile assignment yet at the Met.

Mr. Nikitin was also at the center of another closely observed “Holländer” cast change. In 2012, he withdrew days before he was scheduled to sing the opera’s title role in a new production at the Bayreuth Festival in Germany, after a video of him surfaced showing a tattoo resembling a swastika on his chest. Mr. Nikitin later said that the tattoo was never meant to be a swastika, and was in fact part of a heraldic crest in an eight-pointed star that was left unfinished.

He has sung “Holländer” around the world, including in St. Petersburg, Madrid, Toronto, Paris and Tokyo. (He canceled concert performances of the opera in Russia, as well as performances at the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, to take the Met engagement.)

The Met’s production, also starring the soprano Anja Kampe in her company debut as Senta, will be conducted by Valery Gergiev. Mr. Gergiev was on the podium when Mr. Nikitin made his Met debut in 2002, in Prokofiev’s “War and Peace,” which was also Ms. Netrebko’s first performance with the company.

from WordPress https://mastcomm.com/the-metropolitan-operas-fill-in-dutchman-evgeny-nikitin/

0 notes

Text

I avui insisteixo amb el Parsifal bavarès perquè ja he vist el streaming amb la producció de Pierre Audi que com imaginava no millora en res la boníssima impressió que em vaig endur quan “només” vaig escoltar la transmissió radiofònica del dia 28 de juny.

Malauradament el director libanès m’aporta poc i em molesta amb la seva “genialitat” del segon acte. Tampoc el treball amb el cantants sembla extraordinari i la foscor innecessària i tètrica d’una producció amb pretensions, pedant, avorrida i mancada de teatralitat, enterboleixen una vegada més una excel·lent proposta musical i vocal.

La traïdoria contra les acotacions wagnerianes és total i encara és l’hora que hagi d’entendre perquè les noies flors es mostren tan destrempants i perquè el Sr Audi mostra aquesta obsessió jo diria que malaltissa per les pròtessis exagerades i tendents a la deformació de temptadores noies flors o cavallers venerables.

Molts altres Parsifal han adulterat o traït directament les acotacions wagnerianes i no has respecta res, però caram! hi havia una narració treballada que esdevé atractiva o intensament potent i teatral, ja sigui la signada per Herheim, ja sigui la de Guth o la menys trencadora de Laufenberg a Bayreuth o fins i tot la de Tcherniakov, totes elles interessats, però aquesta d’Audi és inútil i el que m’exaspera més lletja, molt lletja, no hi ha ni un cert tractament estètic on agafar-se, ni una realització teatral brillant, res.

Però Petrenko i l’equip vocal aconsegueixen amb merescut escarni, fer oblidar de manera implacable al Sr Audi.

La versió del dia 8 de juliol m’ha semblat més rodona que la del dia 28. Kaufmann espectacular demostrant-nos una vegada més com s’equivoca quan canta les òperes italianes com les canta.

Pape continua sent, malgrat la feblesa del registre greu, un gran Gurnemanz, mentre que Gerhaher amb la seva particular manera de dir, fonamenta unes noves bases de com cantar o potser seria millor dir, com dir Amfortas. No és el meu model, ni el meu referent en aquest rol, però la intensitat de la interpretació és colpidora.

A Koch Audi el maltracta amb una caracterització de Klingsor grotesca, però el baríton-baix imposa vocalitat per sobre de banalitat.

Stemme està immensa, però gèlida. El segon acte el supera amb molta solvència vocal, però hagués estat bé una passió desbordada que ni ella imposa ni segurament Audi no vol.

Cor i orquestra de somni sota la extraordinària direcció de Petrenko, atent a les pauses, tan importants en questa òpera, però mantenint un ritme més aviat lleuger respecte a altres direccions letàrgiques que volen imitar allò inimitable. Petrenko no vol ser ell i ho és i triomfa.

Si bé el streaming no aporta res, la versió musical i vocal és superior, sota el meu parer a la retransmissió radiofònica i només per això hem de beneir amb aigua santa del Montsalvat aquesta magnífica versió.

El nivell de Munich és extraordinari, envejable i me’l poso com a fita

.

Richard Wagner

PARSIFAL

Amfortas: Christian Gerhaher

Titurel: Bálint Szabó

Gurnemanz: René Pape

Parsifal: Jonas Kaufmann

Klingsor: Wolfgang Koch

Kundry: Nina Stemme

Erster Gralsritter: Kevin Conners

Zweiter Gralsritter: Callum Thorpe

Stimme aus der Höhe: Rachael Wilson

Erster Knappe: Paula Iancic

Zweiter Knappe: Tara Erraught

Dritter Knappe: Manuel Günther

Vierter Knappe: Matthew Grills

Klingsors Zaubermädchen: Golda Schultz, Selene Zanetti, Tara Erraught, Noluvuyiso Mpofu, Paula Iancic, Rachael Wilson

Kinderchor der Bayerischen Staatsoper, director Stellario Fagone

Chor der Bayerischen Staatsoper director Sören Eckhoff

Bayerisches Staatsorchester

Direcció musical: Kirill Petrenko

Direcció d’escena: Pierre Audi

Escenografia: Georg Baselitz, Christof Hetzer

Disseny de vestuari: Florence von Gerkan, Tristan Sczesny

Disseny de llums: Urs Schönebaum

Dramatúrgia: Benedikt Stampfli, Klaus Bertisch

Bayerische Staatsoper 8 de juliol de 2018

INSISTINT EN EL PARSIFAL DE MUNICH (KAUFMANN-STEMME-PAPE-GERHAHER-KOCH;AUDI-PETRENKO) I avui insisteixo amb el Parsifal bavarès perquè ja he vist el streaming amb la producció de…

#Bayerische Staatsoper Chor und Orchestra#Bayerisches Staatsorchester#Bálint Szabó#Callum Thorpe#Christian Gerhaher#Golda Schultz#Jonas Kaufmann#Kevin Conners#Kinderchor der Bayerischen Staatsoper#Kirill Petrenko#Manuel Günther#Matthew Grills#Nina Stemme#Noluvuyiso Mpofu#Parsifal#Paula Iancic#Pierre Audi#Rachael Wilson#Rachel Wilson#René Pape#Richard Wagner#Selene Zanetti#Tara Erraught#Wolfgang Koch

0 notes

Text

Asie mutée, je ris au-dedans

“Asie, Asie, Asie, vieux pays merveilleux des contes de nourrice… ” ainsi commence le poème de Tristan Klingsor qui a été écrit en 1903 et mis en musique par Ravel, ouvrant sa trilogie Shéhérazade. Souvent, je fredonne cette mélodie française, et j’entends alors une autre voix que la mienne, celle de Régine Crespin sous la baguette d’Ernest Ansermet. Et, puis, je pars, en Asie, magnétisée. Je…

View On WordPress

0 notes