#Sun Guoting

Photo

Figure 1. Jiang Qingji’s fan calligraphy, UWM Special Collections (cs 000092).

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work,

Part 11

Today we continue our exploration of calligraphic scripts in Chinese fan work, with further examples of Zheng vs. Qi approaches.

Figure 1 is a fan text written in a cursive script. According to Tai Jingnong (1902-1990), a scholar in Chinese poetry, calligraphy, and painting, cursive scrip first appear in the Han Ju Yan Wooden Slips, which were created from the Han (206 BCE-220 CE) to Jin Dynasty (265-420 CE).The cursive script from this period, such as that found in Monthly and Seasonal Records of Military Supplies from the Kuang-ti South Platoon in the Yung-yüan Era , originated from the hurried writing of the older clerical script (see my last blog).

In this fan, Jiang Qingji (1820-1880) copied a section of A Narrative on Calligraphy by Sun Guoting (646–691, see my blog on Zhang Jian), a very important treatise summarizing the esthetic values of Chinese calligraphy. However, the copying of the text is as far as the similarity goes. For Jiang 敏 in Figure 2 (a), the undulation of the brush breaks the stroke for a staccato thickening-and-thinning effect, whereas Sun’s counterpart in Figure 3 (a) is much more smooth and legato --- a typical characteristic of cursive script canonized by the calligraphic sage Wang Xizhi (303-361 CE, Figure 3 (b)). The variance, angularity, and exaggeration imbue Jiang’s brush with a strong sense of design.

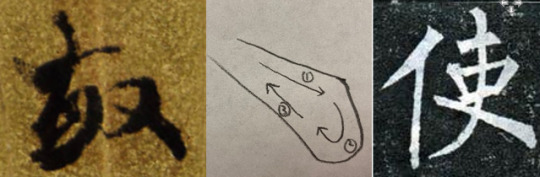

(From left to right):

Figure 2 (a) : Detail from Figure 1

Figure 2 (b): Analysis of the Last Stroke in Figure 2 (a), made by Jingwei Zeng

Figure 2 (c): Detail from The Stele of Xuanmi Pagoda

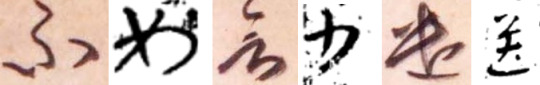

(From left to right):

Figure 3 (a): Detail from Sun Guoting’s The Manual on Calligraphy

Figure 3 (b): Detail from Wang Xizhi’s On the Seventeenth Day

Figure 3 (c): Detail from Lu Ji’s Recovering from Illness

Figure 3 (d): Detail from Liu Sha Zhui Jian

Jiang’s design is much more apparent in 敏’s last brush (Figure 2 (a)). The brush tip goes rightward first, creates an angle, then makes a circle before it goes back to form a sculptural stroke (see Figure 2 (b)). The bulging monumentality of this stroke is analogous to its counterpart in Figure 2 (c) from the standard writing The Stele of Xuanmi Pagoda --- another calligraphic masterpiece in Chinese history inscribed by Liu Gongquan (778-865) in 841. According to Wang Shizhen (1526-1590), a famous writer and historian in the Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644), this stele is the most telling example of Liu’s penchant for rippling tendon and bone in his creations. In our fan, Jiang complicated his brush movement by introducing a contrived sculptural design from Liu’s standard writing. Since standard writing can also be called “Zheng” writing in Chinese (see my previous post), contrived design can be seen as the embodiment of Zheng style, a conservative form, relying on established styles and techniques.

The monumentality of Liu’s Zheng style is derived from the Four Masters of Tang (Ouyang Xun, 557-641, Yu Shinan,558-638, Chu Suiliang, 596-658, and Xue Ji, 649-713), whose works are utilized to glorify the peace and prosperity of the dynasty. In Tai Jingnong’s opinion, a calligraphic untrammeled naturalness (Yi, 逸, which is the correlative of Qi, a style of originality, challenging recognized norms) is compromised by this propagandistic self-aggrandizement.

As a matter of fact, the last stroke in Sun’s original work (Figure 3 (a)) exhibits some untrammeled naturalness, as the end of last stroke does not have an obvious sense of design. A much more untrammeled and natural style can be seen in the similar strokes in Wang Xizhi’s On the Seventeenth Day (fourth century, Figure 3 (b)), Lu Ji (261-303)’s Recovering from Illness (ca.303, Figure 3 (c)) and Liu Sha Zhui Jian (ca. 98BC, Figure 3 (d)) --- they are guided by concepts of Yi & Qi.

Figure 4. Titian’s Danaë

The contrast between premeditated design (Zheng) and the untrammeled naturalness (Yi & Qi) can be seen in the Western art, too. In Titian’s famous work Danaë (figure 4), the body of the woman to the left is derived from Michelangelo's female figure in the sculpture at the Medici Chapel entitled Night, possessing a great designing effect and sculpturality (similar to Jiang and Liu’s Zheng style); on the contrary, the white satin under her body is sketched by the bold slash of the brush (similar to Wang, Lu, and Liu Sha Zhui Jian’s Yi & Qi style), suggesting an unbridled idiosyncrasy, thereby foretelling the arrival of Baroque art.

(From left to right):

Figure 5 (a): Fu Shan’s imitation of Wang Xizhi’s Letter Written in the First Lunar Month

Figure 5 (b): Liu Sha Zhui Jian

(From left to right):

Figure 6 (a): from Figure 5 (a)

Figure 6 (b): from Figure 5 (b)

Figure 6 (c): from Figure 5 (a)

Figure 6 (d): from Figure 5 (b)

Figure 6 (e): from Figure 5 (a)

Figure 6 (f): from Figure 5 (b)

Fu Shan (1607-1684), who was the master for Qi’s style, considered premeditated Zheng’s design as a bete noire and he preferred untrammeled naturalness in his art. In Figure 5 (a), though it is Fu’s imitation of Wang Xizhi’s work, it bares greater resemblance to the wooden slip Liu Sha Zhui Jian in Figure 5 (b). Fu and Liu Sha Zhui Jian employed an unmodulated linearity (Figure 6 (a) and (b)), an untrammeled leisure (the “丿” in Figure 6 (c) and (d)), and an unembellished naturalness (the last horizontal line in Figure 6 (e) and (f)). Both of them epitomized Qi & Yi concepts.

It is worthwhile mentioning that Fu never had the chance to see Liu Sha Zhui Jian, which was excavated in 1906-1907 (see my previous Zheng Xiaoxu’s post), around three hundred years after Fu’s time. The striking similarity between Fu’s work and Liu Sha Zhui Jian testifies Fu’s inimitable capacity to imagine the broken part of the art history by tracing the path of calligraphic evolution.

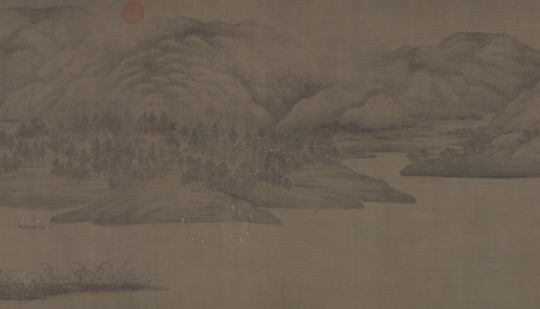

Figure 7: Huang Binhong’s Landscape Painting

Fu’s Qi legacy is carried on by Huang Binhong (1865-1955), an extraordinary Chinese modern landscape painter whose brushwork is characterized by raw, unmodulated, and untrammeled naturalness. The brushwork of Huang’s painting in Figure 7 bears a strong correlation to Fu’s brush in Figure 5 (a) and the satin of Danaë in Figure (4)---they are ad-libbed in the spur of the moment, implying an ephemeral yet highly-spiritualized transcendentalism.

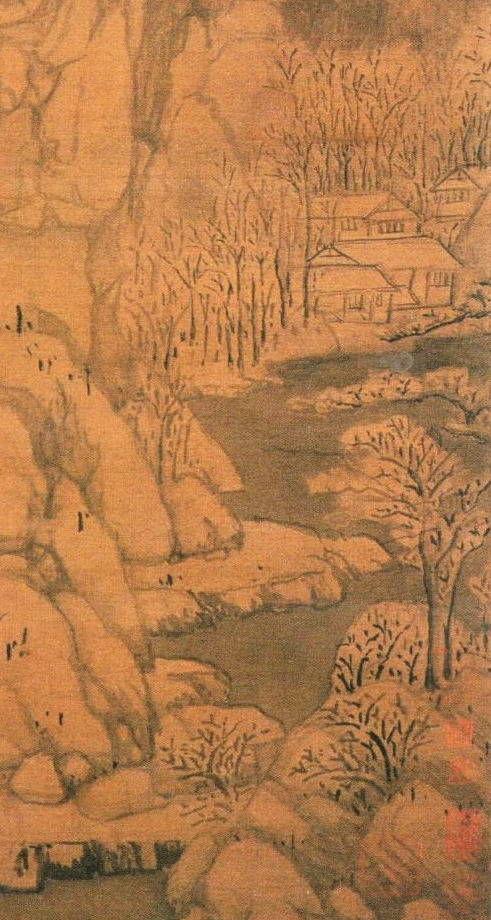

According to The Petty Sayings of Painting, a famous thesis on Chinese painting esthetics, Chinese landscape painting is similar to the writing of cursive and running script --- the creation should not be restrained by rigor and workmanship (i.e., premeditated design, or Zheng). Dong Yuan’s (c. 934-962) interplay of voids and solids (see Figure 8, Dong’s The Rivers of Xiao and Xiang), Mi Fu’s (1051-1107) smoky mountains improvised by horizontal dots, Mi’s son Mi Youren’s (1074-1153, or 1086-1165) The Ink Play of Cloudy Mountains (see Figure 9), and Huang Gongwang’s (1269-1354) withered trees and lean mountains (see Figure 10, Huang’s Nine Submits after the Snow) exhibit a feeling of untrammeled naturalness. On the contrary, “only the vulgar artisans will deliberately create the meticulous paintings in order to please the audiences’ eyes.” The paintings made by this pleasing servitude is “drab and dour.”

Figure 8. Dong Yuan’sThe Rivers of Xiao and Xiang

Figure 9. Mi Youren’s The Ink Play of Cloudy Mountains

Figure 10. Huang Gongwang’s Nine Submits after the Snow

Yi & Qi also happens under Cezanne’s (1839-1906) hands. In Montagne Sainte-Victoire (Figure 11), Cezanne did not choose a refined brush to design remote mountains; instead, he created a simple calligraphic line as his abstract rendition of the landscape. For all these artists, mastering a skill of unpremeditated and sophisticated disegno (Zheng) is not difficult (and indeed, they did so when they were young); what challenged them most was how to get rid of formulaic design and create a free, simple, and impromptu Yi & Qi effect. By doing this, they presented their own characters rather than representing the rules and regulations of traditional and formulaic style.

Figure 11. Cezanne’s Montagne Sainte-Victoire

View more posts from the Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Jingwei#Chinese calligraphy#Chinese fans#Chinese art#Chinese paintings#Chinese history#art history#calligraphy#calligraphers#Zheng style#Qi style#Jiang Qingji#Sun Guoting#Liu Gongquan#Wang Xizhi#Lu Ji#Liu Sha Zhui Jian#Fu Shan#Titian#Michelangelo#Huang Binhong#Dong Yuan#Mi Fu#Mi Youren#Huang Gongwang#Paul Cezanne#Zhou Cezong Collection#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silinmez anlar vardır karşı konmaz Özlem'ler...!!!

#sunset#sun#sky#sea#cloud#waves#sunrise#vintage#retro#adventure#sundown#indie#indie music#clouds#landscape#cemal süreya#alıntı#guote#guotes#guote of the day#book quotes#love#love quotes#positive guotes#positivity#inspring quotes#inspire#inspirational quotes#inspiration#seascape

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

Έλα κατσε παρέα μου, εχω τόσα να σου πω...

Θα ξεκινήσω με το σ αγάπησα και σ αγαπώ....

V.N.

#Greek #greece #Ελλάδα #hellas #wood #sun #greekguotes #guote #σκέψεις #thoughts #γρεεκ #Tumblr #greektumblr #βράδια #παγκάκι #feelings #νύχτες #night #karpenisi

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The sky and the sun are always there. It’s the clouds that come and go.” ☀️️⛅️️ ~Rachel Joyce~ #guote #sky #sun #cluds https://www.instagram.com/p/CS18DG2NPY2/?utm_medium=tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

Anlıyor musun?

Gökyüzü güneş olsa,

Sensiz karanlıktayım...

(Do you understand?

If the sky is the sun,

I'm in the dark without you.)

#tumblr#artists on tumblr#writers on tumblr#sky#love#love poem#photografy#sun#sunrise#sunlight#love guotes#lovely#women#beatufiul#edebiyat#güzel sözler#book quotes#books#books & libraries#short poem#poemas en tumblr#photography#photographers on tumblr

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“something poetic about hope”- Paulo Coelho Quote Generator

#hope#funny quote#guote of the day#sun#graffiti#urban#urban photography#cloudy#rain#rainy day#monohrome#reflection#photographers on tumblr#original photographers

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Her şey düzelmez ama her şey geçer..."

(Yoruma Kapalı!)

257 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mavi Liman...

Çok yorgunum, beni bekleme kaptan.

Seyir defterini başkası yazsın.

Çınarlı, kubbeli, mavi bir liman.

Beni o limana çıkaramazsın...

🖤🎼🎼🎶🎶

#nazım hikmet#türk şair#türk yazar#şair#edebiyat#cem karaca#sanatçı#rock#çok yorgunum#alıntı#guote#guotes#guote of the day#book quotes#love#books#love quotes#motivational guotes#sun#sunset#sea#sunrise#sundown#retro#vintage#sky#cloud#adventure#clouds#waes

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

"İnsan çaya benzer; sıcak suyun içinde demlenene kadar gerçek rengini bilemesiniz..."

#tea#çay#doğa#çaykeyfi#muğla#photo#sun#naturephotography#türkiye#vsco#photography#turkey#cottage aesthetic#cottage#cozy#cottagecore#alıntı#guote#guotes#book quotes#lit#positive guotes#positivity#inspring quotes#motivational guotes#inspiration#inspire#inspirational quotes#indie

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sadece sahilde oturup dalgaları dinlemek istiyorum...

#alıntı#books#books & libraries#book quotes#positive#positive guotes#guotes#motivational guotes#landscape#sunset#sun#sky#sea#cloud#waves#sunrise#vintage#retro#adventure#sundown#indie music

288 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work, Part 5

Zhang Jian (1853-1926) was one of the most successful entrepreneurs in modern Chinese history, as well as an eminent leader in constitutional government and Chinese modernization. In a calligraphic scroll from our Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work, Zhang, also an accomplished calligrapher, cites an anecdote from one of Song Dynasty scholar-official Su Dongpo's literary works:

After reading [2nd-century BCE musician and poet] Sima Xiangru’s “Da Ren Fu,” Emperor Wu in West-Han dynasty feels like a deity who can walk on the cloud and travel in the universe. Recent scholars believe themselves to be as talented as Sima Xiangru, so they emulate his works with alacrity. Sima has died and can't make any comment for these emulations. However, I believe these works are just boring and may make audiences feel sleepy and fall out of bed---they could hardly have experience to walk on the cloud.

This calligraphy was dedicated to Yiqing, who followed Zhang in philanthropic activities during the final days of his life. The cursive calligraphic style derives from early Tang Dynasty calligrapher Sun Guoting’s A Narrative on Calligraphy, pulsating with fluidity, confidence, and spontaneity. Influenced by a passion to learn the ancient stele of the late Qing dynasty, however, Zhang also imbued this work with a strong sense of sublimity and equanimity. The integration of these opposing styles can also be seen in his political ambition.

Zhang was the Principal Graduate (the highest-ranking student in the national official examination) in 1894. In the next year, he helped Kang Youwei (1858-1927), whom I posted about earlier, to initiate the Society for Study of National Strengthening in Shanghai. However, he was relatively conservative in his political stance. Therefore, when he knew Kang and Liang Qichao (1873-1929), whom I also posted about, were in the full swing during the Hundred Days’ Reform, he indicated that the reform might have unpredictable consequences and he cautioned Kang and Liang, “don’t act foolhardily.” Being disillusioned by the corruption of the court, he decided to go back to his hometown to create businesses and invest in education. During his life, he set up more than twenty enterprises and three-hundred-and-seventy schools in China. He also founded Nantong Museum in 1905, the first museum in Mainland China. The bust of Zhang Jian shown here stands outside Nantong Museum.

As a businessman, Zhang needed a peaceful environment for his companies, so he did not want to see revolutions. Citing Japanese constitutionalism practiced since the Meiji Reform, he asserted that only constitutionalism could save China from degradation. Therefore, integrating monarchical beliefs and democratic principles became his political ambition, and he determined to transform China into a modern society. Nevertheless, after political unrest, in 1912 Zhang was designated to write the Edict of Abdication for Puyi, the last emperor of China. When the new temporary government was founded, he used his property as the mortgage to stabilize the financial situation of the country.

During the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s, Zhang’s tomb was opened and destroyed by the Red Guard. Only one hat, one pair of glasses, one fan, and one small box with the his tooth and hair were found. This “booty” seems so meager in view of his extraordinary prestige and achievements. Based on his accomplishments, he is often honored as one of the “creators of the Republic of China.”

View more posts from the Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Chinese calligraphy#Chinese scrolls#Zhang Jian#Chinese politics#Chinese political reforms#Su Dongpo#Chinese history#art history#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Zhou Cezong Collection#Jingwei

22 notes

·

View notes