#Rosemary Tonks

Text

Rosemary Tonks, Story of a Hotel Room

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bedouin of the London Evening, Rosemary Tonks (2016)

Running Away

"I was a guest at my own youth"

"I was a hunter whose animal / Is that dark hour when the hemisphere moves"

"Her priest's mouth the green scabs of winter."

"Through darkness on the knuckles of / A woman's glove."

//

20th Century Invalid

"that I am stricken / And anonymous on city nights"

//

Bedroom in an Old City

"in order / that they may be said to think deeply, people go to the trouble of believing their opinions even when they are alone."

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Audrey Wollen

January 3, 2023

We open every book with the assumption that the writer wishes it to be read. Readers occupy a default position of generosity, bestowing the gift of our attention on the page before us. At most, we might concede that a novel or a poem was written for inward pleasures only, without the need or anticipation of an audience. It is very rare to open a book and to feel—to know—that the writer did not want us to read it at all, and, in fact, tried to prevent our reading it, and that, in reading the book, we are resurrecting a self that the writer wished, without hesitation or mercy, to kill.

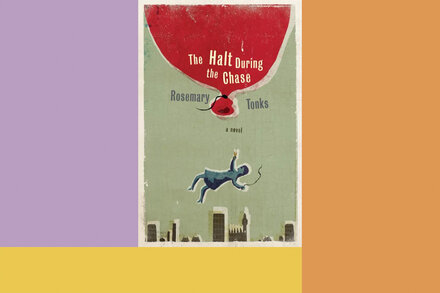

This is the case with Rosemary Tonks’s “The Bloater,” published originally in 1968 and reissued in 2022 by New Directions, eight years after the author’s death in 2014. Without this intervention, Tonks might have succeeded in wiping “The Bloater” out, along with five other novels and two books of strange and special poetry, scorching her own literary earth. Before New Directions’ reissue and Bloodaxe Books’ posthumous collection of her poetry, getting hold of any of her work was prohibitively expensive; one novel could cost thousands of dollars.

Tonks was born in 1928. By the age of forty, she had accomplished what many strive for: opportunities to publish her work and critical respect for it. Her Baudelaire-inflected poems were admired by Cyril Connolly and A. Alvarez, and her boisterous semi-autobiographical novels had some commercial success. Philip Larkin included her in his 1973 anthology “The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse.” She collaborated with Delia Derbyshire, the iconic early electronic musician who helped create the “Doctor Who” theme, and Alexander Trocchi, the novelist and famed junkie, on cutting-edge “sound poems.” At the parties that she hosted at her home in Hampstead, the bohemian literati of Swinging London were spellbound by her easy, unforgiving wit. Tonks was principled and ambitious about her writing, pushing a continental decadence into the oddly shaped crannies of bleak British humor. Until an unexpected conversion to fundamentalist Christianity compelled her to disavow every word.

After a series of harrowing crises in the nineteen-seventies, culminating in temporary blindness, she disappeared from public life, in 1980, leaving London for the small seaside town of Bournemouth, where she was known as Mrs. Lightband; she made anonymous appearances in the city to pass out Bibles at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park. She felt a calling to protect the public from the sinfulness of her own writing by burning her manuscripts, actively preventing republication in her lifetime, and destroying evidence of her career. There are tales of her systematically checking out her own books from libraries across England in order to burn them in her back garden. This is a level of self-annihilation that can be categorized as transcendent or suicidal, or a perfect cocktail of both, depending on who you ask.

Of course, most writers hate their own writing, either in flickers or a sustained glare, but they are also entranced by it, wary yet astonished. Many writers stop writing entirely, but part of the Faustian deal of publishing is that what you created lasts—beyond your feelings toward it, beyond your commitment to creating more of it, beyond your being alive to read it. Rimbaud, whom Tonks adored, famously quit poetry by twenty-one, after wringing out his wunderkind brutality, but silence is not necessarily the same as self-censorship. Tonks renounced literature as others do intoxicants, a clean break with an evangelical bent. She became allergic to all books, not only her own, refusing to read anything but the Bible. The connection between substances and language is one that she made while she was still using, so to speak; “Start drinking!” her poem “The Desert Wind Élite” commands. “Choked-up joy splashes over / From this poem and you’re crammed, stuffed to the brim, at dusk / With hell’s casual and jam-green happiness!!”

In retrospect, it’s easy to claim the dingy desolation that she describes at the heart of bohemia as some seedling of religious shame, but that would be irresponsible. Undeniably, the speakers of her poems (and, in a cheerier way, her novels) are drenched by “the champagne sleet / Of living,” of walking home from a stranger’s bedroom in the chill of dawn. “I have been young too long,” she writes, in her poem “Bedouin of the London Evening,” “and in a dressing-gown / My private modern life has gone to waste.” Her writing documents a life that prioritizes “grandeur, depth, and crust,” and those qualities are not stumbled upon, fished from the gutters, but hard-won: “I insist on vegetating here / In motheaten grandeur. Haven’t I plotted / Like a madman to get here? Well then.” Poetry, Tonks proposes, is found in the soapy bodies of resented lovers, the ashen walls of hotel hallways, the sharp rustle of February rain outside unwashed windows. Sadness is a given, but shame? Shame we reflect back upon these scenes through the mirror of her later faith, for the ease of narrative. While I can’t begrudge someone their higher power of choice, it’s heartbreaking to encounter something so wonderful that became such a terrible burden to its maker. Maybe that is what I find the most compelling about the story of Tonks: being able to articulate her troubles with such slanted beauty, a beauty that many writers would triple their troubles for, did nothing to stave off a need for self-punishment and the possibility of apotheotic forgiveness.

In “The Bloater,” the protagonist, Min, is grappling with a plight immemorial, a quandary so intimate that it might be one of the most universal questions that humanity shares: whom should she have sex with, given the baroque logistics of seduction and, more important, the shockingly limited options? As she exclaims, “Why do the only men I know carry wet umbrellas and say ‘Umm?’ I am being starved alive.” Her husband, George, the walking personification of incidental, is not on the table. Marriage, in Min’s subcultural nineteen-sixties, is merely an architectural situation, which one lives with neutrally, familiarly, as one might a doorknob. Its practical purpose is self-evident. It neither imprisons nor romances; it has zero relationship to morality, fantasy, obligation, or idealization. Sex, on the other hand, inflicts all of the above. For Min, if marriage is a doorknob, an affair is a door that opens onto the world.

The primary candidate for her affair is, at first, the eponymous Bloater, a looming, accomplished opera singer who can make every room feel like a bedroom, and whom Min associates with “red fur coats, soup, catarrh, and grating dustbins.” A bloater is a kind of cold-smoked fully intact herring, once popular in England, named for the swelling of its body during preparation. Puffed up from within, they are open-mouthed, iridescent; van Gogh painted multiple still-lifes of them in a demoralizing, reflective pile. The Bloater pursues Min with an almost delusional confidence, interpreting all of her insults as adorable idiosyncrasies. Min responds to the Bloater’s sustained flirtation with showy disgust—performed for him, her friends, and her own inner monologue—but she keeps inviting him back. Terrified of being left out of her historical moment, Min confronts the erotic complexity of being a woman suddenly freed by the sexual revolution, freed right into a new arrangement of social pressures. Yet the novel isn’t really about Min and the Bloater but, rather, the slapstick confusion between wanting someone, wanting to be wanted by them, and wanting to want in general, to know yourself capable of the focus that longing demands. It is about flirtation as a method of self-organization, and a crush as a method of self-torture. All of “The Bloater,” however—every single sentence—is funny.

Min’s cruelties and inconsistencies stem from Tonks’s surprisingly forward-thinking analysis of the sexual politics of the era: yes, straight women have full, active sexualities, and they want to have sex freely, just as much as men (if not more), but they are also constantly aware of what a power disadvantage they have, how every seduction comes with traps, social, emotional, and physical. In “The Bloater,” that push and pull, of desire and the reality of its consequences, creates an environment where women are always on the sexual back foot, so to speak—understandably defensive, cynical, anxious, and, at worst, rivalrous. Early in the novel, Min and her co-worker Jenny, who bears a striking resemblance to the aforementioned Delia Derbyshire at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, are eating cheese sandwiches on break and discussing the terrible dangers of a guitarist Jenny likes, who returned after the end of a party to help Jenny clean (uh-huh) and, instead, lay down on the floor, across her foot, “a sure sign of a late developer.” But just as she started to move away, “he leant over slowly and kissed with the most horrible, exquisite, stunning skill—” Jenny extolls. “Born of nights and nights and nights of helping people clear up after parties,” Min responds.

As Jenny continues to describe this slightly open-mouthed kiss with increasing fervor—“He knows everything,” everything being the existence of the clitoris, one assumes (one hopes)—Min spirals. “Stop! I’m agitated. She’s gone too far, and is forcing me to live her life. Where are my coat, my ideas, my name? . . . She makes me feel like I’ve got to justify myself; catch the first plane to New York, or something equally stupid. . . . Oh! I know exactly what she means; and yet, what on earth does she mean?” Min, in a personal chaos of arousal by proxy and urgent insecurity, does what so many have done, before and since: she embarrasses her friend by implying that Jenny is being too candid about her own lust. Accusations of sluttiness, the perennial hazard of women’s honesty, peek their heads around a cheese sandwich. “Basically I’ve double-crossed her emotionally, but she’ll forgive me because my motive is pure jealousy. Here we go, purring together.” Tonks pins down the fascination and bewilderment of hearing another woman describing the kind of sex that you’ve never had; the awful impulse to get your bearings by claiming your inexperience as a power position, reducing yourself to a genre of virtue that you don’t even believe in; and the way, after all that, you can walk away even closer friends, absolved by an unspoken camaraderie. For Jenny and Min, the wrangling of inherited antagonisms is transparent, absurd, and shared. Women talk over the rumblings of their own internalized misogyny, laughing louder and louder.

All the characters in “The Bloater” are trying to ward off a singular agonizing fate: falling in love. For Tonks, love is its own thing, separate from both sex and its inverse, marriage, a dreaded vulnerability that could strike at any moment if one enjoys life a little too much. Min observes, “The hard core of the trouble with the Bloater is that most of the time he’s not real to me. To someone else he may personify reality. . . . The men who are absolutely like oneself are the dangerous ones.” It’s obvious from early on in the novel that the Bloater is simply the rhapsodic foil to the man who is Min’s own personification of reality: her friend Billy, who accepts her emotional blockades with a quiet optimism. When it seems as if Billy might kiss her, Min almost falls down, thinking,

And I shall begin to think, and to long, and to be jealous. My peace of mind and my gaiety will be gone for ever. I shall have to be balanced and to keep my heart strong, to fight and to be catty, and to reinvent my arrogance all over again by an effort of will. . . . My much prized, friendly, reliable Billy will turn into a male whose flesh will keep me awake at night, and I shall have no one to phone up and complain to when he makes me unhappy.

Tonks describes the small miracle of mutual attraction through Min’s vigorous reluctance, getting closer to the true stakes of what is happening than to the usual tropes of romance. For Min, Billy is a complete rearrangement of the universe—uprooting the ego, creating flesh where there once was none. May cattiness protect us.

Min is at odds with her historical moment, slightly dislodged from time, but perhaps this is a state inherent to femininity—what era would have served her better? Min is used to being told she’s difficult:

Lots of George’s friends at the Museum, men of about fifty-eight with black thickets in their nostrils, literally save this up as the only thing which will give them any pleasure over a winter weekend: “Now I’ll just go round there for a cup of tea so that I can explain to Min what a difficult sort of woman she is.”

A woman’s personality would always make more sense in a situation that hasn’t happened yet. What Min admires in Billy is that he “moves straight into the future without any effort. In fact he’s one of the few people who are simultaneously alert to their own past, present, and future”—whereas she has a tendency to boil her life down into “pure beef essence” before she can contemplate what might happen next. That’s alienation, baby. When Billy does finally kiss her, Min swoons and observes, “I’m not the spectator I’m accustomed to being; I’m not in front of him, nor am I getting left behind.” The present arrives, without expectation. Love is being allowed, for the length of a kiss, to step outside of history.

There is a straightforward interpretation of Tonks/Lightband’s total rejection of her past writing: it promotes women speaking of their sexual needs and pleasures with clarity, intoxicants enjoyed and encouraged, poetry seeking “the Eros of grey rain, Veganin, and telephones.” (Veganin is an over-the-counter drug consisting of acetaminophen, caffeine, and codeine.) But accounts of her life suggest that her conflict was not with the content, necessarily, but the very concept of writing for others at all. In 1999, she noted in a private journal, “What are books? They are minds, Satan’s minds. . . . Devils gain access through the mind: printed books carry, each one, an evil mind: which enters your mind.”

She was afraid of finding someone else’s thoughts left behind in her personality, like a strange scarf unearthed from the sofa cushions after a party. Books were the most acute threat to the sanctity of the bordered self. Of course, Tonks is right: that is what reading does—it places another’s mind in your own mind. It is the swiftest metaphysical delirium we have, impossible to replicate. The immensity of what reading feels like should not be discounted by its omnipresence in our daily lives. How do we distinguish between the sentences that sprout and green from our own selves, the arcane loam of the individual, and the sentences that fall and land there, alien and already bloomed? Is there even a difference to discover?

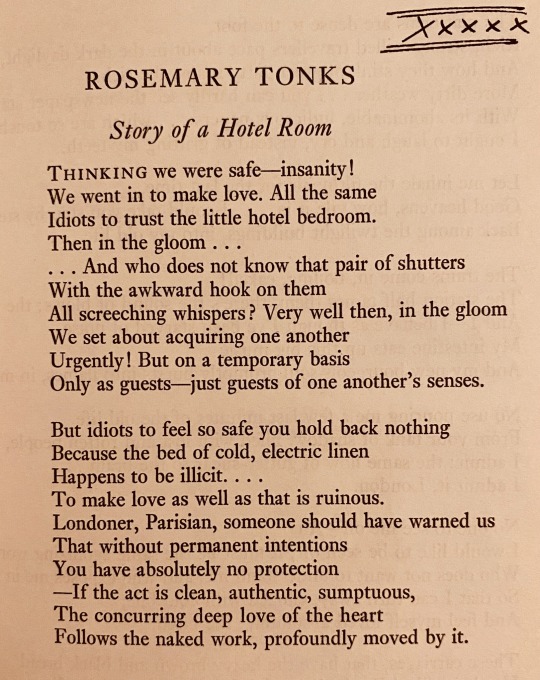

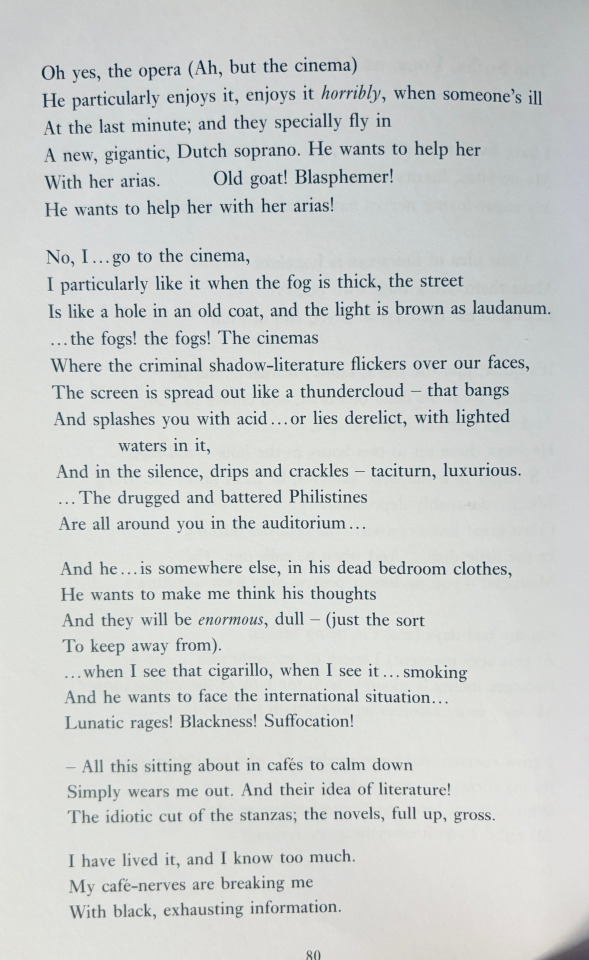

In her poetry, Tonks repeatedly alludes to the feeling of finding the other or the outside buried deep inside herself. In one of my favorites, “The Sofas, Fogs, and Cinemas,” she describes trying to escape a man’s overpowering opinions by going to the movies. She writes, “The cinemas / Where the criminal shadow-literature flickers over our faces, / The screen is spread out like a thundercloud.” The speaker is sunk in her own experience, but the man “is somewhere else, in his dead bedroom clothes, / He wants to make me think his thoughts / And they will be enormous, dull—(just the sort / To keep away from).” The poem closes with her “café-nerves” broken, and the speaker unable to sort her thoughts from the man’s. In another, “The Little Cardboard Suitcase,” she describes herself “as a thinker, as a professional water-cabbage” (cabbage is deployed at the height of its comedic potential across her work) who cannot trust her own body, trying hopelessly “to educate myself / Against the sort of future they flung into my blood— / The events, the people, the ideas—the ideas!”

Tonks’s conversion marked a change in her direction and use of idiom, but her reverence for the power of language never faltered. Mrs. Lightband lived comfortably, avoiding evil forces and writing in her journals, until her death at the age of eighty-five. In her solitude, she found alternate forms of communication. Neil Astley describes, in his introduction to the collected poems, how she listened to the birds, how “she would interpret soft calls or harsh caws or cries from crows and seagulls in particular as comforting messages or warnings from the Lord, and would base decisions on what to do, whom to trust, whether to go out, how to deal with a problem, on how these bird sounds made her feel.” In other words, she never stopped reading poetry.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oath

Rosemary Tonks

I swear that I would not go back

To pole the glass fishpools where the rough breath lies

That built the Earth – there, under the heavy trees

With their bark that’s full of grocer’s spice,

Not for an hour – although my heart

Moves, thirstily, to drink the thought – would I

Go back to run my boat

On the brown rain that made it slippery,

I would not for a youth

Return to ignorance, and be the wildfowl

Thrown about by the dark water seasons

With an ink-storm of dark moods against my soul,

And no firm ground inside my breast,

Only the breath of God that stirs

Scent-kitchens of refreshing trees,

And the shabby green cartilage of play upon my knees.

With no hard earth inside my breast

To hold a Universe made out of breath,

Slippery as fish with their wet mortar made of mirrors

I laid a grip of glass upon my youth.

And not for the waterpools would I go back

To a Universe unreal as breath – although I use

The great muscle of my heart

To thirst like a drunkard for the scent-storm of the trees.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Audrey Wollen

January 3, 2023

We open every book with the assumption that the writer wishes it to be read. Readers occupy a default position of generosity, bestowing the gift of our attention on the page before us. At most, we might concede that a novel or a poem was written for inward pleasures only, without the need or anticipation of an audience. It is very rare to open a book and to feel—to know—that the writer did not want us to read it at all, and, in fact, tried to prevent our reading it, and that, in reading the book, we are resurrecting a self that the writer wished, without hesitation or mercy, to kill.

This is the case with Rosemary Tonks’s “The Bloater,” published originally in 1968 and reissued in 2022 by New Directions, eight years after the author’s death in 2014. Without this intervention, Tonks might have succeeded in wiping “The Bloater” out, along with five other novels and two books of strange and special poetry, scorching her own literary earth. Before New Directions’ reissue and Bloodaxe Books’ posthumous collection of her poetry, getting hold of any of her work was prohibitively expensive; one novel could cost thousands of dollars.

Tonks was born in 1928. By the age of forty, she had accomplished what many strive for: opportunities to publish her work and critical respect for it. Her Baudelaire-inflected poems were admired by Cyril Connolly and A. Alvarez, and her boisterous semi-autobiographical novels had some commercial success. Philip Larkin included her in his 1973 anthology “The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse.” She collaborated with Delia Derbyshire, the iconic early electronic musician who helped create the “Doctor Who” theme, and Alexander Trocchi, the novelist and famed junkie, on cutting-edge “sound poems.” At the parties that she hosted at her home in Hampstead, the bohemian literati of Swinging London were spellbound by her easy, unforgiving wit. Tonks was principled and ambitious about her writing, pushing a continental decadence into the oddly shaped crannies of bleak British humor. Until an unexpected conversion to fundamentalist Christianity compelled her to disavow every word.

After a series of harrowing crises in the nineteen-seventies, culminating in temporary blindness, she disappeared from public life, in 1980, leaving London for the small seaside town of Bournemouth, where she was known as Mrs. Lightband; she made anonymous appearances in the city to pass out Bibles at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park. She felt a calling to protect the public from the sinfulness of her own writing by burning her manuscripts, actively preventing republication in her lifetime, and destroying evidence of her career. There are tales of her systematically checking out her own books from libraries across England in order to burn them in her back garden. This is a level of self-annihilation that can be categorized as transcendent or suicidal, or a perfect cocktail of both, depending on who you ask.

Of course, most writers hate their own writing, either in flickers or a sustained glare, but they are also entranced by it, wary yet astonished. Many writers stop writing entirely, but part of the Faustian deal of publishing is that what you created lasts—beyond your feelings toward it, beyond your commitment to creating more of it, beyond your being alive to read it. Rimbaud, whom Tonks adored, famously quit poetry by twenty-one, after wringing out his wunderkind brutality, but silence is not necessarily the same as self-censorship. Tonks renounced literature as others do intoxicants, a clean break with an evangelical bent. She became allergic to all books, not only her own, refusing to read anything but the Bible. The connection between substances and language is one that she made while she was still using, so to speak; “Start drinking!” her poem “The Desert Wind Élite” commands. “Choked-up joy splashes over / From this poem and you’re crammed, stuffed to the brim, at dusk / With hell’s casual and jam-green happiness!!”

In retrospect, it’s easy to claim the dingy desolation that she describes at the heart of bohemia as some seedling of religious shame, but that would be irresponsible. Undeniably, the speakers of her poems (and, in a cheerier way, her novels) are drenched by “the champagne sleet / Of living,” of walking home from a stranger’s bedroom in the chill of dawn. “I have been young too long,” she writes, in her poem “Bedouin of the London Evening,” “and in a dressing-gown / My private modern life has gone to waste.” Her writing documents a life that prioritizes “grandeur, depth, and crust,” and those qualities are not stumbled upon, fished from the gutters, but hard-won: “I insist on vegetating here / In motheaten grandeur. Haven’t I plotted / Like a madman to get here? Well then.” Poetry, Tonks proposes, is found in the soapy bodies of resented lovers, the ashen walls of hotel hallways, the sharp rustle of February rain outside unwashed windows. Sadness is a given, but shame? Shame we reflect back upon these scenes through the mirror of her later faith, for the ease of narrative. While I can’t begrudge someone their higher power of choice, it’s heartbreaking to encounter something so wonderful that became such a terrible burden to its maker. Maybe that is what I find the most compelling about the story of Tonks: being able to articulate her troubles with such slanted beauty, a beauty that many writers would triple their troubles for, did nothing to stave off a need for self-punishment and the possibility of apotheotic forgiveness.

In “The Bloater,” the protagonist, Min, is grappling with a plight immemorial, a quandary so intimate that it might be one of the most universal questions that humanity shares: whom should she have sex with, given the baroque logistics of seduction and, more important, the shockingly limited options? As she exclaims, “Why do the only men I know carry wet umbrellas and say ‘Umm?’ I am being starved alive.” Her husband, George, the walking personification of incidental, is not on the table. Marriage, in Min’s subcultural nineteen-sixties, is merely an architectural situation, which one lives with neutrally, familiarly, as one might a doorknob. Its practical purpose is self-evident. It neither imprisons nor romances; it has zero relationship to morality, fantasy, obligation, or idealization. Sex, on the other hand, inflicts all of the above. For Min, if marriage is a doorknob, an affair is a door that opens onto the world.

The primary candidate for her affair is, at first, the eponymous Bloater, a looming, accomplished opera singer who can make every room feel like a bedroom, and whom Min associates with “red fur coats, soup, catarrh, and grating dustbins.” A bloater is a kind of cold-smoked fully intact herring, once popular in England, named for the swelling of its body during preparation. Puffed up from within, they are open-mouthed, iridescent; van Gogh painted multiple still-lifes of them in a demoralizing, reflective pile. The Bloater pursues Min with an almost delusional confidence, interpreting all of her insults as adorable idiosyncrasies. Min responds to the Bloater’s sustained flirtation with showy disgust—performed for him, her friends, and her own inner monologue—but she keeps inviting him back. Terrified of being left out of her historical moment, Min confronts the erotic complexity of being a woman suddenly freed by the sexual revolution, freed right into a new arrangement of social pressures. Yet the novel isn’t really about Min and the Bloater but, rather, the slapstick confusion between wanting someone, wanting to be wanted by them, and wanting to want in general, to know yourself capable of the focus that longing demands. It is about flirtation as a method of self-organization, and a crush as a method of self-torture. All of “The Bloater,” however—every single sentence—is funny.

Min’s cruelties and inconsistencies stem from Tonks’s surprisingly forward-thinking analysis of the sexual politics of the era: yes, straight women have full, active sexualities, and they want to have sex freely, just as much as men (if not more), but they are also constantly aware of what a power disadvantage they have, how every seduction comes with traps, social, emotional, and physical. In “The Bloater,” that push and pull, of desire and the reality of its consequences, creates an environment where women are always on the sexual back foot, so to speak—understandably defensive, cynical, anxious, and, at worst, rivalrous. Early in the novel, Min and her co-worker Jenny, who bears a striking resemblance to the aforementioned Delia Derbyshire at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, are eating cheese sandwiches on break and discussing the terrible dangers of a guitarist Jenny likes, who returned after the end of a party to help Jenny clean (uh-huh) and, instead, lay down on the floor, across her foot, “a sure sign of a late developer.” But just as she started to move away, “he leant over slowly and kissed with the most horrible, exquisite, stunning skill—” Jenny extolls. “Born of nights and nights and nights of helping people clear up after parties,” Min responds.

As Jenny continues to describe this slightly open-mouthed kiss with increasing fervor—“He knows everything,” everything being the existence of the clitoris, one assumes (one hopes)—Min spirals. “Stop! I’m agitated. She’s gone too far, and is forcing me to live her life. Where are my coat, my ideas, my name? . . . She makes me feel like I’ve got to justify myself; catch the first plane to New York, or something equally stupid. . . . Oh! I know exactly what she means; and yet, what on earth does she mean?” Min, in a personal chaos of arousal by proxy and urgent insecurity, does what so many have done, before and since: she embarrasses her friend by implying that Jenny is being too candid about her own lust. Accusations of sluttiness, the perennial hazard of women’s honesty, peek their heads around a cheese sandwich. “Basically I’ve double-crossed her emotionally, but she’ll forgive me because my motive is pure jealousy. Here we go, purring together.” Tonks pins down the fascination and bewilderment of hearing another woman describing the kind of sex that you’ve never had; the awful impulse to get your bearings by claiming your inexperience as a power position, reducing yourself to a genre of virtue that you don’t even believe in; and the way, after all that, you can walk away even closer friends, absolved by an unspoken camaraderie. For Jenny and Min, the wrangling of inherited antagonisms is transparent, absurd, and shared. Women talk over the rumblings of their own internalized misogyny, laughing louder and louder.

All the characters in “The Bloater” are trying to ward off a singular agonizing fate: falling in love. For Tonks, love is its own thing, separate from both sex and its inverse, marriage, a dreaded vulnerability that could strike at any moment if one enjoys life a little too much. Min observes, “The hard core of the trouble with the Bloater is that most of the time he’s not real to me. To someone else he may personify reality. . . . The men who are absolutely like oneself are the dangerous ones.” It’s obvious from early on in the novel that the Bloater is simply the rhapsodic foil to the man who is Min’s own personification of reality: her friend Billy, who accepts her emotional blockades with a quiet optimism. When it seems as if Billy might kiss her, Min almost falls down, thinking,

And I shall begin to think, and to long, and to be jealous. My peace of mind and my gaiety will be gone for ever. I shall have to be balanced and to keep my heart strong, to fight and to be catty, and to reinvent my arrogance all over again by an effort of will. . . . My much prized, friendly, reliable Billy will turn into a male whose flesh will keep me awake at night, and I shall have no one to phone up and complain to when he makes me unhappy.

Tonks describes the small miracle of mutual attraction through Min’s vigorous reluctance, getting closer to the true stakes of what is happening than to the usual tropes of romance. For Min, Billy is a complete rearrangement of the universe—uprooting the ego, creating flesh where there once was none. May cattiness protect us.

Min is at odds with her historical moment, slightly dislodged from time, but perhaps this is a state inherent to femininity—what era would have served her better? Min is used to being told she’s difficult:

Lots of George’s friends at the Museum, men of about fifty-eight with black thickets in their nostrils, literally save this up as the only thing which will give them any pleasure over a winter weekend: “Now I’ll just go round there for a cup of tea so that I can explain to Min what a difficult sort of woman she is.”

A woman’s personality would always make more sense in a situation that hasn’t happened yet. What Min admires in Billy is that he “moves straight into the future without any effort. In fact he’s one of the few people who are simultaneously alert to their own past, present, and future”—whereas she has a tendency to boil her life down into “pure beef essence” before she can contemplate what might happen next. That’s alienation, baby. When Billy does finally kiss her, Min swoons and observes, “I’m not the spectator I’m accustomed to being; I’m not in front of him, nor am I getting left behind.” The present arrives, without expectation. Love is being allowed, for the length of a kiss, to step outside of history.

There is a straightforward interpretation of Tonks/Lightband’s total rejection of her past writing: it promotes women speaking of their sexual needs and pleasures with clarity, intoxicants enjoyed and encouraged, poetry seeking “the Eros of grey rain, Veganin, and telephones.” (Veganin is an over-the-counter drug consisting of acetaminophen, caffeine, and codeine.) But accounts of her life suggest that her conflict was not with the content, necessarily, but the very concept of writing for others at all. In 1999, she noted in a private journal, “What are books? They are minds, Satan’s minds. . . . Devils gain access through the mind: printed books carry, each one, an evil mind: which enters your mind.”

She was afraid of finding someone else’s thoughts left behind in her personality, like a strange scarf unearthed from the sofa cushions after a party. Books were the most acute threat to the sanctity of the bordered self. Of course, Tonks is right: that is what reading does—it places another’s mind in your own mind. It is the swiftest metaphysical delirium we have, impossible to replicate. The immensity of what reading feels like should not be discounted by its omnipresence in our daily lives. How do we distinguish between the sentences that sprout and green from our own selves, the arcane loam of the individual, and the sentences that fall and land there, alien and already bloomed? Is there even a difference to discover?

In her poetry, Tonks repeatedly alludes to the feeling of finding the other or the outside buried deep inside herself. In one of my favorites, “The Sofas, Fogs, and Cinemas,” she describes trying to escape a man’s overpowering opinions by going to the movies. She writes, “The cinemas / Where the criminal shadow-literature flickers over our faces, / The screen is spread out like a thundercloud.” The speaker is sunk in her own experience, but the man “is somewhere else, in his dead bedroom clothes, / He wants to make me think his thoughts / And they will be enormous, dull—(just the sort / To keep away from).” The poem closes with her “café-nerves” broken, and the speaker unable to sort her thoughts from the man’s. In another, “The Little Cardboard Suitcase,” she describes herself “as a thinker, as a professional water-cabbage” (cabbage is deployed at the height of its comedic potential across her work) who cannot trust her own body, trying hopelessly “to educate myself / Against the sort of future they flung into my blood— / The events, the people, the ideas—the ideas!”

Tonks’s conversion marked a change in her direction and use of idiom, but her reverence for the power of language never faltered. Mrs. Lightband lived comfortably, avoiding evil forces and writing in her journals, until her death at the age of eighty-five. In her solitude, she found alternate forms of communication. Neil Astley describes, in his introduction to the collected poems, how she listened to the birds, how “she would interpret soft calls or harsh caws or cries from crows and seagulls in particular as comforting messages or warnings from the Lord, and would base decisions on what to do, whom to trust, whether to go out, how to deal with a problem, on how these bird sounds made her feel.” In other words, she never stopped reading poetry.

0 notes

Text

Books I have read this year, 2023, roughly in order

I enjoyed doing this last year, so I thought I would do another little write-up of the books I read this year and what I thought.

I've read 52 books this year, hitting a goal I hadn't thought to set. That includes a few graphic novels, but not the audiobooks, which I listened to 15 of this year (I spent a lot of time driving). Same as last year, I've annotated the audiobooks with an asterisk.

I also started listening to Backlisted this year, which significantly influenced my reading choices.

Under a cut, because it got long

Swedish Cults, Anders Fager (1/2) - I saw this was originally published in 2009, and I feel like the first story in this collection somehow really echoes that time. Which is probably a strange thing to say about a horror story.

When Washington was in Vogue, Edward Christopher Williams (1/13) - very sweet, very interesting look at a time and a place I didn't know much about.

The Cement Garden, Ian McEwan (1/19) - I expected to enjoy this a lot more than I did, based on how it's often described as a great "fucked up" book. I think the teenage boy POV just didn't do much for me.

Cold Comfort Farm, Stella Gibbons (1/20) - a reread, for the first time since probably 2014 or so. I enjoyed it (and understood it) a lot better this time around. I got to the back half and couldn't put it down, which is a strange thing to say about a parody of the rural novels of the 1930s.

Nona the Ninth, Tamsyn Muir (2/12) - finally got this from the library. I didn't enjoy it as much as the first two books in the series

Fun Home, Alison Bechdel (2/24) - a reread. The final page always destroys me.

Cassandra at the Wedding, Dorothy Baker (2/25) - Very literary. I think I enjoyed it, though I can't muster up the energy to form a stronger opinion. The scene where Cassandra pulls out the bridesmaid dress she bought was memorable, though.

Are You My Mother?, Alison Bechdel (2/28) - a reread. Scratches the same itch as Fun Home, but doesn't tie the family narrative into the theoretical themes as cohesively.

Surviving the Applewhites, Stephanie S. Tolan (3/12) - another reread, to see if it was as good as I remembered from fourth grade. It held up for the most part.

The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Alison Bechdel (3/13) - finally, not a reread. Fun, erudite, perhaps not as tight as Fun Home, but another excellent Bechdel.

Ravishment, Amanda Quick (3/24) - sometimes you have to read an entire romance novel in an evening. This was fun, though its plot and that of "Mistress" (see below) blur into one another.

Season of Migration to the North, Tayib Saleh (4/7) - I think I would have enjoyed this book more if I had read it in a class where I could discuss it and learn more about the historical context behind it.

The Bloater, Rosemary Tonks (4/9) - of Backlisted fame. I should reread again, more slowly, to get a better taste for Tonk's use of language.

Mistress, Amanda Quick (4/15) - also a fun quick read, though I can't remember much of the plot.

Excellent Women*, Barbara Pym (4/25) - yet another attempt to get into audiobooks, and it semi-worked this time. Mildred sets a high bar for other Pym protagonists to follow, and I thought Pym created an excellent portrait of post-war life for unmarried women and the minor indignities and intimacies that accompany it. Also ridiculously funny, at least to me.

Clouds of Witness*, Dorothy L. Sayers (5/12) - I wanted to read Gaudy Night, but I figured I should read at least a few Peter Wimsey mysteries that came before it. I think my favorite character was Lord Wimsey's mother.

Star, Yukio Mishima (5/16) - an interesting portrait of a disaffected youth and of fame in Japan at the time it was written.

Strong Poison*, Dorothy L. Sayers (5/16) - the first Wimsey mystery to feature Harriet Vane, and my first encounter with Lord Peter's office of overlooked older secretaries, who provides the enjoyable detour of Miss Murchison making an important breakthrough in the case. Not bad, though not super memorable.

Have His Carcase, Dorothy L. Sayers (5/17) - the only Wimsey mystery I read instead of listened to, because neither library app had the audiobook. This one was too reliant on keeping timetables straight for my taste, but I still read it in a day.

Beyond Black, Hilary Mantel (5/22) - possibly the best book I read this year. Bleak, bleak, bleak, and wonderful for it. Yet one of the most cathartic happy endings I've ever read.

Thus was Adonis Murdered, Sarah Caudwell (5/28) - caught my sense of humor by the second or third page. Hilariously dry mystery, and understandable even if you don't know legal jargon.

The Feast, Margaret Kennedy (5/31) - this book is not even remotely a thriller, is in fact sort of an elaborate morality play, and yet I couldn't put it down. The conceit- that a cliff collapses onto a hotel and everyone inside dies, but not all the hotel guests were inside- keeps you guessing at whose sins are bad enough to merit a karmic death.

Starlight, Stella Gibbons (6/4) - a lot grimmer than I expected, and almost ahead of its time in terms of the (I'm going to say) pointlessness of its ending, in a "people come into the main character's lives, stuff happens, but the main two old ladies aren't actually affected" way. Not a book you would expect to find demonic possession in, but it's there and it's played straight!

The Shortest Way to Hades, Sarah Caudwell (6/6) - I find it interesting that all of these mysteries center around details of things like inheritance law and yet all feature murder as the main crime, and also that (spoilers) the villain is disposed of in a manner that does not require the main cast to get involved with the police.

The Sirens Sang of Murder, Sarah Caudwell (6/9) - by the second volume in this series I kept trying to guess who the murderer, and I was never ever able to do it. Not that I've ever been good at that part of mystery novels, but I do appreciate Caudwell keeping me on my toes.

Gaudy Night*, Dorothy L. Sayers (6/11) - finally, the book I read three prior mysteries for. I found this one fascinatingly slow for a mystery and much more focused on the life of women in academia in that era than I had expected. I particularly enjoyed the character of Miss de Vine, who at first seems like the classic absent-minded professor, only to reveal herself to be much wiser in ways of the heart than she appears.

The Black Maybe, Attila Veres (6/19) - short horror story collection, translated from Hungarian. Not bad, but none of the stories were super memorable.

Lessons in Chemistry, Bonnie Garmus (6/22) - I did not enjoy this and probably would not have finished it if my mom hadn't highly recommended it. The characters felt flat and the plot struggled to build enough tension for the emotional beats to hit. I also feel like the four-year-old character did not act anything like a four-year-old, though I'll admit I don't know a lot of four-year-olds.

Hackenfeller’s Ape, Brigid Brophy (6/26) - I would say this book wasn't that exciting, very dry and academic for its bizarre plot, but one detail near the end (which I won't spoil) knocked me sideways and tbh probably made the book for me.

Less Than Angels*, Barbara Pym (6/27) - I had to go back and add this while writing these reviews because I'd completely forgotten to list it at the time. Not as good as Excellent Women, though I also had to adjust to the multiple perspectives as opposed to just one.

Comemadre, Roque Larraquy (7/2) - a reread. Still one of the strangest books I've ever read. Highly recommend.

The Sky is Blue, With a Single Cloud, Kuniko Tsurita (7/3) - I'd had this collection of manga one-shots for about a year, and decided to finally read it when hanging out at the library when the water was out at my apartment. It's very interesting to see her style develop and to learn more about the alternative manga industry.

Mrs. Caliban, Rachel Ingalls (7/4) - I had been vaguely meaning to read this for a while, then found it on Hoopla. Looking back on it, it rivals In a Lonely Place (the Dorothy Hughes one) with regards to drawing California in the mind's eye, though the mood of their particular Californias are very different.

Black Wings Has My Angel, Elliott Chaze (7/8) - the tension at the end of this book is like pulling teeth, it's incredible.

Scruples, Judith Krantz (7/24) - absolutely frothy and frequently ridiculous, but also fun. Their are main characters named Spider and Valentine, and it's taken completely seriously. It's actually a really interesting look at the values and beliefs of the 1980's as reflected through pop culture.

Days in the Caucasus, Banine (7/28) - I was more interested in the sequel to this memoir, Parisian Days, but figured I should read this volume, about the author's childhood in Azerbaijan in the years leading up to its incorporation into the Soviet Union. It provided a really interesting perspective of the Soviet Union from a resident of one of its subject states.

Frederica, Georgette Heyer (8/6) - my first Heyer. I'm impressed by her ability to write annoying younger siblings and walk the line between "overly cute" and "overly aggravating".

In the Miso Soup, Ryu Murakami (8/17) - good, though not my favorite of the year by far. The violence depicted did manage to turn my stomach a bit.

My Man Jeeves*, P.G. Wodehouse (8/20) - I've realized that I need to listen to audiobooks that are fun if I'm going to survive long drives, so I turned to the Jeeves series (I only listened to the Jeeves stories in this one). An interesting introduction to the character, especially since it starts in America instead of the England of the more well-known tales.

Love in the New Millennium, Can Xue (8/29) - I'm not sure if this book is meant to be very surreal, if I'm missing cultural context, or both, but I will say it does serve me well to be a little befuddled by books sometimes. This book has a strange, flowing sense of perspective, where it moves between perspectives and the stories of its characters, only slowly unveiling where it's emotional weight lies. Very interesting.

The Inimitable Jeeves*, P.G. Wodehouse (9/1) - second collection of Jeeves & Wooster stories. Good, though Bingo isn't my favorite side character.

Flesh, Brigid Brophy (9/1) - the beginning chapters are incredibly sensual in a way I can't describe, but after that it inspired an incredible feeling of dread that something would go terribly wrong. Despite the fact that this is a satire of young adults in 1960s London, I could feel emotional catastrophe creeping around every corner. I don't think this was Brophy's intention.

Ice*, Anna Kavan (9/8) - somehow not anything like I had osmosed it being. The narrative flows between reality and fantasy so fluidly that it's incredibly easy to wonder if you spaced out and missed something important while listening to it. The plot is also fascinatingly simple and surprisingly free of actual conflict: despite impediments, the hero ("hero") rarely actually encounters any opposition that seems like it could truly keep him from his goal. This adds to the feeling that everything occurring in the book is barely-veiled symbolism.

The Glass Pearls, Emeric Pressburger (9/13) - the tension in this might have honestly been too much for me. Good, but I don't know if I can read it again.

The English Understand Wool, Helen DeWitt (9/16) - sometimes you read a book and recognize that it's very good, while also being annoyed that what it is is different from what you want it to be. I understood it worked as a morality tale, but I found it limiting and frustrating. I will also indulge in a bit of cattiness here and say that for a book about luxury and high-quality goods, the book design chosen by New Directions for this series feels like a cheap set of children's books. (I read this on an online checkout from the library, so I only saw the book itself in a bookstore.)

Right Ho, Jeeves*, P.G. Wodehouse (9/18) - The fact that Jeeves and Bertie were on the outs for this one did stress me out, I will admit.

In a Lonely Place, Karl Edward Wagner (9/22) - the stories pick up in quality in the back half, in my opinion, though none of them are true duds. The last story and standout in the collection, yet another twist on a vampire tale, really draws its strength from the grimy-yet-glamorous depiction of an art student's life in London.

Kissing the Witch, Emma Donoghue (9/27) - I enjoyed how each story folded into one another and found this book hard to put down. Also very gay, loved it.

The Drama of Celebrity, Sharon Marcus (9/27) - I was reading this for background for my fic, and it was somewhat helpful. It's really mostly an analysis of Sarah Bernhardt's career, with some light theory of celebrity to contextualize it instead of the other way around like I expected.

Malpertuis, Jean Ray (10/15) - I probably shouldn't have read the summary for this book before the book itself, but I'm not sure I would have fully understood the plot if I hadn't. Not a knock on the book itself.

The Great God Pan and Other Stories*, Arthur Machen (10/16) - I don't read a ton of nineteenth-century literature, so I was surprised by how compelling the title story was, especially when listened to. I also found some of the imagery in "The Novel of the White Powder" horrifying and would not be out of place in a modern horror story. The final story was a bit of a slog, though.

Heartburn*, Nora Ephron (10/20) - a relisten to the version narrated by Meryl Streep. I downloaded it based on a recommendation describing the audiobook as turning it into the one-woman monologue the book was meant to be, and I can't think of any higher recommendation to offer than that.

Casting the Runes and Other Stories*, M.R. James and others (10/30) - I knew about M.R. James from popular culture, but I honestly had not expected "Whistle and I'll Come to You, My Lad" to center so much around golf.

Invitation the the Waltz, Rosamond Lehmann (11/1) - I read most of this in one sitting, playing old music through my headphones, which felt really ideal. Setting most of it during one formal dance allows for a sense of insular-ness while allowing the details of the world to be woven in. If that makes any sense.

Crazy Salad and Scribble Scrabble*, Nora Ephron (11/3) - it's really interesting to listen to these essays written during the second wave feminist movement and realize that we've been having the same arguments for 50 years. It's also interesting to read about the minutiae of Watergate from the perspective of those watching it unfold in real time. So many weird, unmemorable cultural-political things that have gone down the hole of public memory! (I need to note here that the last essay in Crazy Salad is, based on my memory of the first time I read it (I skipped it this time around) very transphobic, so I can only recommend this collection with that heavy caveat.)

BBC Radiophonic Workshop: A Retrospective, William L. Weir (11/7) - I first learned about the BBC radiophonic workshop through the Backlisted episode about Rosemary Tonks, and this was a fascinating look into that period of British history and the origins of electronic music. It's also helped me pinpoint how to find that sort of music I think of as "alien abduction music", which is a bonus.

Joy in the Morning*, P.G. Wodehouse (11/10) - I didn't realize this wasn't in the 3-book arc that starts with Right Ho, Jeeves until I was partway through. Still, quality Wodehouse.

Good Morning, Midnight, Jean Rhys (11/17) - despite listening to the Backlisted episode before reading this, I didn't quite grasp what "modernist novel" meant, which meant I was surprised by the stream-of-consciousness flow of this novel. It's such gorgeous writing, though. Depressing as hell.

Winter Love*, Han Suyin (11/18) - beautiful and sad. The main character, Red, is frustrating, even though everything she does is perfectly understandable within the context she lives in.

The Girls, John Bowen (11/21) - the blurbs for this book ("Barbara Pym meets Stephen King") made it seem like this would be both lighter and more horrifying than it actually was. I found it to actually be very melancholy in parts, and surprisingly focused on the emotional aftereffects of murder. The ending, the final paragraph, is gorgeous.

Black Orchids, Rex Stout (11/30) - I'm now trying to find Nero Wolfe books in secondhand bookstores, though I'm limited by the lack of secondhand bookstores in my area (that may be a good thing). I enjoy how Nero Wolfe and Archie play off each other.

The Hearing Trumpet*, Leonara Carrington (12/1) - so, so good, and I'm glad I listened to it as an audiobook, because the narrator, Sian Phillips, is an elderly woman herself and therefore able to conjure up a whole range of different voices for the old women who populate this book.

Mistletoe Malice, Kathleen Farrell (12/6) - I was actually disappointed by this, which might have been a matter of mismatched expectations. However, the Christmas tree never caught fire, and I swore a review I read said it would, so I spent the whole book waiting in vain.

Venetia, Georgette Heyer (12/16) - A delight. Aubrey is a great character, and I enjoy how Heyer has the different characters play on each other.

Great Granny Webster, Caroline Blackwood (12/18) - did not expect this book to have a large section on "decaying old Anglo-Irish homes and their horrors", but I guess that's a richer vein in literary fiction than I realized (see: Good Behaviour by Molly Keane).

Sylvester, Georgette Heyer (12/21) - not quite as enjoyable as Frederica or Venetia, in my opinion, though that may be partly because I waited for almost 2/3 of the book for Phoebe's book to actually be published.

Providence, Anita Brookner (12/28) - beautiful prose, of the sort that makes me realize my own inadequacies in both my writing and my critical capabilities, because I can neither replicate it or describe what makes it so compelling. This book is also so tightly crafted for a story where almost nothing happens. It ends up exactly where it's been leading all along.

#ghost posts#oh my god this took forever to write#52 books! I'm surprised at myself#I really should make that list of “twentieth century queer or queer-ish literary fiction that I have read and can recommend”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nymph of House Black

Of all the stories I've written, this one remains one of my favorites. I'm highlighting it today because of the recently launched @womenofthehouseofblack

What does it feature? The whole Black fam, of course, with the MC Tonks posing as pureblood daughter Pandora Black. She gets to hang out with Bellatrix, Narcissa, Andromeda, Walburga, and Druella. The whole Black fam!

Oh, and she kicks ass while doing it.

Longer snippet and link below:

Dora and Al appeared at Grimmauld Place. Tonks felt a familiar sense of foreboding upon seeing the Black family home again. This time, she would see Walburga Black, alive and in the flesh. A shiver ran up her spine as she braced herself for her first Black family reunion.

Al led Tonks up the memorable steps and knocked on the serpent door-knocker. The door opened and Kreacher, the Black family house elf, bowed deeply.

“Master Alphard,” Kreacher started, “Mistress is waiting for you in the drawing room.”

Kreacher looked at Tonks quizzically, as if trying to place her properly. “The new young Miss?” Kreacher asked.

“Yes, Kreacher,” confirmed Al. “You’ll know more when you need to.”

“Kreacher lives to serve the House of Black,” Kreacher croaked, and led Al and Tonks down the hall towards the drawing room.

Tonks was genuinely surprised to see Grimmauld Place so clean. The last time she had been in the house, it was grimy, dusty, and gloomy. The house was still creepy and dark, but it was at the very least clean. Kreacher’s devotion to his Mistress was unwavering.

Al put his hand on Dora’s shoulder and led her into the drawing room. He gave her shoulder a slight squeeze, and she curtsied to the Black family members gathered there.

Dora’s eyes grew wide as she viewed the scene. She swallowed bile as she looked at Bellatrix Lestrange, sitting calmly in front of her new husband, Rodolphus Lestrange. Tonks twitched her hand slightly towards her wand. She insisted on carrying it with her. She would be passing it off as her “mother” Rosemary’s old wand, explaining why a pre-Hogwarts student had a wand so early.

“Alphard,” Walburga greeted. “We’ve been expecting you.”

“We have been looking forward to this meeting,” Alphard replied. “Please allow me to introduce my daughter, Pandora Rosemary Black.”

Tonks stepped forward, focusing all her efforts on not tripping over the robes hanging on her frame. She glanced up briefly, and curtsied as well as she could towards the gathered. She glanced back up and then shuffled back near Al.

“Her manners are sufficient for now,” commented an older woman. “She will need further instruction if she should truly be a daughter of the House of Black.”

“Kreacher!” Walburga called. The elf appeared in the room and bowed deeply before his Mistress.

“Is this child a Black?” she demanded. “Is there a bond?”

Kreacher appraised Tonks. A heavy lump was forming in her stomach. I have Black blood, she thought, my mother is Andromeda Black. My mother is a Black.

Kreacher croaked, “Kreacher sees the bond. The child is a Black,” he declared, and bowed before Tonks. She let out a sigh of relief.

“Give him an order, Dora” urged Alphard. “That will confirm if you are truly my daughter.”

Tonks nodded. She said, “Kreacher, bring me a glass of water.” Kreacher disappeared for a moment and returned with a glass of water, presenting it to Tonks.

“Is that all, Miss Dora?” he asked.

“Yes, Kreacher, you are dismissed,” Tonks commanded. The elf disappeared, and everyone in the room nodded approvingly. Tonks was truly a Black.

“Why have you kept her from us, Al?” thundered an old man. Ah, that must be Pollux, Sirius’ grandfather, Tonks thought. The woman who commented on my manners must be Irma, the grandmother.

“I did not wish to marry, Father,” replied Al, calmly. “If the child had been a true heir, then perhaps I would have been more inclined.” What was left unsaid: as Dora was a female child, marrying her off to bear someone else’s heirs was more of a burden than a boon for House Black.

“She is a bright child and her grandparents felt it appropriate for her to return to England to be educated here,” Al continued.

“She cannot be raised by you alone, Alphard,” cut in Irma. “It is highly improper for a single man to raise a daughter. She shall be raised with Walburga or Druella.”

Shit. Shit. Shit. Sirius was raised by Walburga and that was clearly a terrible childhood. Druella was her own grandmother who allowed Andromeda to be blasted off the family tree. Shit. Shit. Shit.

“I very much agree, Mother,” Alphard admitted. “However, I will see my daughter weekly to determine her progress. No child of mine will be lacking in manners.” He looked sternly at Tonks, before looking back at the rest of the family.

“Walburga, Druella,” drawled Pollux. “Which one of you will take the child?”

“I’m not raising another daughter,” a man snarled. “I hardly need a replacement for the traitor.” That must be dear old granddad, Cygnus. Scowls and hisses spread throughout the room, apparently in protest against Andromeda’s recent betrayal as a blood traitor. If this is what mum suffered while she was here, Tonks thought, she’s much stronger than I ever knew.

“Walburga?” demanded Pollux.

“If I must,” Walburga accepted. “If only to educate the girl as a true Black.”

Dora was aghast at the family dynamic. They treated her as if she were a prop, rather than a human being. It was simply ludicrous, and it explained Sirius’ absolute hatred of his mother.

“Excellent,” stated Alphard. “Perhaps we can arrange introductions now?” No one said anything, which Tonks assumed meant they agreed to introduce themselves. When no one spoke, Al nudged Tonks towards the seated couples. Evidently she was expected to curtsy repeatedly as she introduced herself to everyone.

Dora began with the first set of grandparents, Pollux and Irma. She curtsied, and Pollux kissed her knuckles. Irma nodded. Pollux said, “I am your grandfather, Pollux Black. This is your grandmother, Irma Black.”

“Very nice to meet you both,” Tonks said.

Irma tsked and scowled at Tonks. “Walburga, you’ll need the finest governess for this one.”

Dora held her disgust in and moved to the next couple. She met Cygnus and Druella. They were slightly kinder than Pollux and Irma, but not by very much.

She then moved to Walburga and her husband, Orion. They would be raising her now, with weekly breaks for her “father” Alphard. Orion looked deeply uninterested in Tonks. Walburga examined Tonks from head to toe and tsked as Irma had.

Finally, Dora turned to the couple she most dreaded: Bellatrix and Rodolphus. It took far more effort for her to curtsy to them than to the others. Tonks held in a scowl and hiss as Rodolphus kissed her knuckles. Bellatrix didn’t bother to look at or acknowledge Tonks. Apparently, even after confirming her blood status as a Black, Tonks wasn’t good enough for her Aunt Bellatrix.

“Kreacher!” called Walburga. Kreacher appeared at her feet. “Yes, Mistress,” he croaked, bowing deeply once more. “Fetch Regulus.”

A few moments later, a young boy appeared at the threshold of the drawing room, eyes downcast.

“Enter,” Orion commanded. Tonks gasped; the young boy was truly Regulus! Sirius’ younger, Death Eater brother.

Regulus eyed the room hesitantly before setting his eyes on Dora. He acknowledged everyone in the room and then strode towards Tonks, bowing before her and kissing her knuckles, as the other men had.

Alphard spoke. “This is your cousin, Regulus,” he introduced. “Regulus, this is your cousin, Pandora. You may call her Dora.”

“Yes, mother,” Regulus said softly. Walburga cleared her throat loudly. Regulus flinched, but then offered his arm to Dora. “May I escort you to the dining room?” he asked, tentatively.

Dora smiled at him, and he returned the smile. “Yes, you may, Regulus.” Dora accepted his offered arm as he led them out towards the dining room.

“Are you really my cousin?” Regulus asked shyly when they arrived in the nursery.

“Yes, and are we really in a nursery?” Dora asked, looking at various toys and games littered throughout the room.

“This is where children are supposed to be when we aren’t being tutored or in school yet,” Regulus shrugged. “You didn’t answer my question.” He stared intensely at Dora, his grey eyes so like Sirius, without the kindness and warmth she was accustomed to from her older cousin.

“Whether or not I’m really your cousin?” Dora asked, and Regulus nodded. “I am. I’m half Black. Kreacher answers to me.”

“Prove it,” Regulus contested.

“Kreacher!” Dora called. The ancient elf appeared in the room with a pop!

“Miss Dora calls for Kreacher?” the elf asked, bowing before her.

“Bring Regulus and I some chocolate, please,” she ordered. Kreacher disappeared and returned moments later with two sizable bars of chocolate for Dora and Regulus.

“Thank you, Kreacher,” Dora smiled at the little elf, who looked nervously back up at her before popping away.

“So you are related to us,” Regulus said, in a still-dissatisfied tone. “Are you a pureblood?”

“Yes, but does that really matter?” Dora challenged. “Would you have treated me any differently if I wasn’t a pureblood?”

“I’m supposed to,” Regulus drawled. “You’re a pureblood, so it hardly matters.”

“Blood purity isn’t everything, Regulus,” Dora said hotly. “That’s what doesn’t matter.” She stomped her foot at the boy angrily, furious that the child had already been indoctrinated to believe in blood purity.

“Kreacher!” Dora called. The elf materialized again with a pop!

“Yes, Miss Dora?” Kreacher asked.

“Take me to the room I’m to stay in,” she ordered. “Regulus can come see me another time.”

“Yes, Miss Dora,” Kreacher replied, leading Dora to the room she’d be staying in at Grimmauld Place until she went back to Hogwarts for the second time.

from The Nymph of House Black

#nymphadora tonks#the time traveling nymph#remadora#andromeda black#narcissa malfoy#bellatrix lestrange#walburga black#sirius black#regulus black#orion black#the black family#the black sisters

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

my record collection 2023 :)

Vinyl

Scary Monsters & Super Creeps - David Bowie

The Dreaming - Kate Bush

Never For Ever - Kate Bush

The Songs of Leonard Cohen - Leonard Cohen

Wind on the Water - Crosby & Nash

Crosby, Stills & Nash - CSN

Songs of the Sea - Pete Dawson

Ultraviolence - Lana del Rey

Lust for Life - Lana del Rey

Norman Fucking Rockwell - Lana del Rey

Romance in 1600 - Sheila E.

Liege & Lief - Fairport Convention

Tusk - Fleetwood Mac

Close up the Honky-Tonks - The Flying Burrito Bros

Transangelic Exodus - Ezra Furman

A Trick of the Tail - Genesis

Godspell (original cast recording)

Dookie - Green Day

Hair (original cast recording)

Live Through This - Hole

Celebrity Skin - Hole

Living In the Past - Jethro Tull

Jesus Christ Superstar (1973 motion picture soundtrack)

Greatest Hits (1974) - Elton John

Joanne - Lady Gaga

Court & Spark - Joni Mitchell

On The Threshold Of A Dream - The Moody Blues

The Black Parade/Living with Ghosts - My Chemical Romance

Bella Donna - Stevie Nicks

Songs for our Times - John O'Connor

GP - Gram Parsons

Raising Sand - Robert Plant & Alison Krauss

Queen - Queen

Queen II - Queen

Sheer Heart Attack - Queen

A Night at the Opera - Queen

A Day at the Races - Queen

News of the World - Queen

Jazz - Queen

The Works - Queen

Live at the Rainbow 1973 - Queen

New Again - Taking Back Sunday

Man on Fire - Roger Taylor

Goats Head Soup - The Rolling Stones

Through the Past, Darkly - The Rolling Stones

Metamorphosis - The Rolling Stones

Get Yer Ya-Yas Out! - The Rolling Stones

Linda Rondstadt - Linda Rondstadt

It’s My Way! - Buffy Sainte-Marie

Parsley, Sage, Rosemary & Thyme - Simon & Garfunkel

The Sound of Music (motion picture soundtrack)

Nebraska - Bruce Springsteen

The River - Bruce Springsteen

Below the Salt - Steeleye Span

Stephen Stills - Stephen Stills

Under Soil & Dirt - The Story So Far

Grave New World - Strawbs

Crime of the Century - Supertramp

GLA - Twin Atlantic

Hesitant Alien - Gerard Way

Blunderbuss - Jack White

_

CD

Almost Famous (motion picture soundtrack)

Little Earthquakes - Tori Amos

Odelay - Beck

Daisy - Brand New

Grace - Jeff Buckley

Hounds of Love - Kate Bush

Let Love In - Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds

Push The Sky Away - Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds

Everybody Else Is Doing It… - The Cranberries

Blue Bannisters - Lana del Rey

Flowers of Flesh & Blood - Nicole Dollanganger

Observatory Mansions - Nicole Dollanganger

Ode to Dawn Weiner - Nicole Dollanganger

I Told You I Was Freaky - Flight of the Conchords

Ceremonials - Florence + the Machine

High As Hope - Florence + the Machine

Born This Way - Lady Gaga

Wolfways - Michael Hurley

A Creature I Don’t Know - Laura Marling

The Mask & Mirror - Loreena McKennitt

Elemental - Loreena McKennitt

The Book Of Secrets - Loreena McKennitt

The Visit - Loreena McKennitt

Blue - Joni Mitchell

Clouds - Joni Mitchell

Jagged Little Pill - Alanis Morissette

Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge - My Chemical Romance

Danger Days - My Chemical Romance

GP/Grievous Angel - Gram Parsons

Trio - Dolly Parton, Linda Ronstadt & Emmylou Harris

Meds - Placebo

Band of Joy - Robert Plant

The Bends - Radiohead

OK Computer - Radiohead

The King of Limbs - Radiohead

Transformer - Lou Reed

Darkness on the Edge of Town - Bruce Springsteen

The Promise - Bruce Springsteen

Western Stars - Bruce Springsteen

Carrie & Lowell - Sufjan Stevens

Suede - Suede

Dog Man Star - Suede

Dead & Born & Grown - The Staves

Velvet Goldmine (motion picture soundtrack)

Want Two - Rufus Wainwright

Harvest - Neil Young

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statcat's official list of favorite Cats performers

(I'm horrible with specific ranking so performers are listed in alphabetical order gfiuedw)

Alonzo: Jason Gardiner, Matt Huet

Bombalurina: Erica Lee Cianiculli, Rosemarie Ford, Chelsea Nicole Mitchell, Christine Cornish Smith

Cassandra: Lexy Bittner, Emily Pynenburg, Mette Towley

Demeter: Nora DeGreen, Kim Faure, Juliann Kuchocki, Aeva May, Madison Mitchell, Cornelia Waibel

Electra: Lili Froehlich

Grizabella: Tayler Harris, Jennifer Hudson, Elaine Paige, Mamie Parris

Gus: Christopher Gurr, John Mills, Tony Mowatt

Jellylorum: Sara Jean Ford, Kayli Jamison

Jemima/Sillabub: Arianna Rosario, Ahren Victory

Jennyanydots: Eloise Kropp, Susie McKenna, Emily Jeanne Phillips

Macavity: Daniel Gaymon

Mistoffelees: Jacob Brent, Tion Gaston

Mungojerrie: Danny Collins, Max Craven, John Thornton, Drew Varley

Munkustrap: Robbie Fairchild, Michael Gruber, Matthew Pike, Kade Wright

Old Deuteronomy: Ken Page

Plato: Daniel Gaymon, Tyler John Logan

Rum Tum Tugger: Jason Derulo, John Partridge, Hank Santos, Siegmar Tonk

Rumpleteazer: Jo Gibb, Shonica Gooden, Bonnie Langford, Taryn Smithson

Skimbleshanks: Jeremy Davis, Geoffrey Garratt, Steven McRae, Christopher Salvaggio

Tumblebrutus: Daymon Montaigne-Jones, Devin Neilson

Victoria: Phyllida Crowley Smith, Francesca Hayward, Yuka Notsuka, Georgina Pazcoguin

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

Indie Top 20 Country Countdown Show April 13th, 2024 from Indie Chart on Vimeo.

Top 20 Indie Country Songs April 13th, 2024

#1 ALCOHOL OF FAME

Lee Sims - Adelphos Records

#2 I'm A Ramblin' Man

Mike Hughes - Big Bear Creek Music

#3 MARGARITA MOURNING

Rickie Joe Wilson - Colt Records

#4 The Grand Tour

Burt Winkler - Colt Records

#5 REDNECK MONEY

Colt McLauchlin - Steam Whistle Records

#6 OPEN AIR BAR

Donny Smith - Colt Records

#7 RHYMIN' IN THE RYMAN TONITE

Michael Lusk - Triple Jct. Records

#8 WHEN YOU LAND

Dennis DiChiaro & WNO - Colt Records

#9 HONKY TONK HIPPIE

Henry Jackson - Independent

#10 CLOSING TIME

Dan Knight - Steam Whistle Records

#11 COLD SIDE OF THE BED

Dave Nudo & Dusty Leigh Huston - Emanant Music

#12 LEAVIN' AND SAYIN' GOODBYE

Mike Hughes - Big Bear Creek Music

#13 SHIP WITHOUT A SEA

Trevor Carlesi - Bongo Boy Records

#14 FIGHTING FOR YOUR FREEDOM

Hammond Brothers - Dynasty Records

#15 I'LL PICK YOU UP

Brendan Kelly - Independent

#16 BROTHERLY LOVE

Cody & Burt Winkler - Colt Records

#17 MAGIC IN THIS MOONSHINE

Jeff Orson - Independent

#18 ANYWHERE THERE'S A JUKEBOX

J.K. Coltrain - Colt Records

#19 UNDER THE RIGHT CIRCUMSTANCES

Rosemarie - Colt Records

#20 GOOD WOMAN BLUES

Mike Hughes - Big Bear Creek Music

0 notes

Text

main trio. HEADCANON GAME.

finn weiss.

WHAT THEY SMELL LIKE: lavender and orange, from his apartment. ivory soap, aftershave, and paco rabanne pour homme (top notes are rosemary, clary sage and brazilian rosewood; middle notes are lavender, geranium and tonka bean; base notes are oakmoss, honey, musk and amber). faintly of tobacco, from toby. a bit like the kitchen, too, when he’s been in there for a good portion of the day. basically, he smells really nice.

HOW THEY SLEEP: one hundred percent a cuddler, and not too picky about whether he’s the big or little spoon. when alone, on his side, usually his left.

WHAT MUSIC THEY ENJOY: classical, particularly mozart’s requiem, showtunes, jazz standards, sixties/seventies pop, and the folk revival of the sixties. he loved the baroque pop era. soft spot for the cheesy teenager songs of his youth.

HOW MUCH TIME THEY SPEND EVERY MORNING GETTING READY: depends! give him about thirty minutes, minimum. FAVORITE THING TO COLLECT: records, paints, cookbooks, restaurant take-out menus.

LEFT OR RIGHT HAND: right-handed.

FAVORITE SPORT: cricket and horseback riding! he played golf with malcolm once or twice, but he found it boring. then toby radicalized him against golf, so he’s never doing that again. enjoys baseball games. he went to a few of greta’s softball games when she was younger. does not like american football.

FAVORITE TOURISTY THING TO DO WHILE TRAVELING: art museums, trying restaurants, bar-hopping. he stayed in hostels and locals’ homes the first few times he went overseas.

FAVORITE KIND OF WEATHER: warm, midsummer nights right as the sun starts to go down. he loves sitting outside and listening to the city. quiet mornings after it has snowed, and the sky is still overcast and grey, but in a pleasant way.

FEAR THEY HAVE: getting dementia and forgetting everything and everyone he knows.

THE ONE CARNIVAL / ARCADE GAME THEY ALWAYS WIN WITHOUT FAIL: for carnivals, ring toss. for arcades, pinball.

toby aldshaw-sharif.

WHAT THEY SMELL LIKE: ivory soap and english leather (top notes are bermagot, lavender, lemon, rosemary, and orange; middle notes are honey, iris, and rose; base notes are leather, musk, cedar, vetiver, and tonka bean). tobacco and brandy.

HOW THEY SLEEP: curled in on himself, on his side. big fan of falling asleep sitting up.

WHAT MUSIC THEY ENJOY: country. god, he’s crazy about the western aesthetic. he knows it’s weird to be in a cowboy bar and hear his accent, the novelty hasn’t worn off. all like genres, such as bluegrass and honky-tonk. his favorite artists are johnny cash, john denver (who looks a little like finn, so), george jones, linda martell, patsy cline, and charley pride. what little he got to hear him, he also likes randy travis. he also likes the blues. sister rosetta tharpe, lead belly, etc. he has a big fat crush on teddy pendergrass.

HOW MUCH TIME THEY SPEND EVERY MORNING GETTING READY: like maybe five minutes. sometimes he combs his hair, sometimes he doesn’t.

FAVORITE THING TO COLLECT: dumb graphic tees and sweaters. finn sometimes makes him the latter. also big on records. matchbooks. toby’s a big guitar pick guy – they have a big jar in their apartment they’re always adding to.

LEFT OR RIGHT HAND: left-handed.

FAVORITE SPORT: rodeo sports. soccer.

FAVORITE TOURISTY THING TO DO WHILE TRAVELING: checking out the local music scene.

FAVORITE KIND OF WEATHER: he wishes every day could be about 65f / 18c and sunny, with a little wind to cool off.

FEAR THEY HAVE: above all, being alone.

THE ONE CARNIVAL / ARCADE GAME THEY ALWAYS WIN WITHOUT FAIL: for carnivals, anything that involves aiming – think shooting games, darts. for arcades, pac-man.

june elbus.

WHAT THEY SMELL LIKE: like the woods, but (usually) pleasantly. some really generic deodorant. sometimes, very rarely, love’s baby soft (musk, lavender, vanilla, rose, jasmine, geranium, patchouli), which smells vaguely powdery.

HOW THEY SLEEP: on her stomach.

WHAT MUSIC THEY ENJOY: classical. art pop, like kate bush, her favorite artist of all time. new wave and alternative, because she’s an eighties kid.

HOW MUCH TIME THEY SPEND EVERY MORNING GETTING READY: not very long. she often sleeps in her braids, and doesn’t bother redoing them every day. she doesn’t wear makeup. it’s usually just putting on what she’s going to wear that day.

FAVORITE THING TO COLLECT: books on medieval history, art, and society. d&d dice.

LEFT OR RIGHT HAND: right-handed.

FAVORITE SPORT: she likes the demonstrations they do at the ren faire. so, like, jousting. falconry. she wants to be a falconer. archery. FAVORITE TOURISTY THING TO DO WHILE TRAVELING: art museums. trying restaurants. going to theatres. basically, whatever she did when she was with her uncle ❤️

FAVORITE KIND OF WEATHER: crisp fall days, preferably a little cloudy. the woods are best when it is cold. even better when it has snowed.

FEAR THEY HAVE: losing loved ones. you can imagine how she’s feeling right now.

THE ONE CARNIVAL / ARCADE GAME THEY ALWAYS WIN WITHOUT FAIL: she doesn’t. hope this helps.

0 notes

Text

Rosemary Tonks, "The Sofas, Fogs, and Cinemas" from Bedouin of the London Evening: Collected Poems.

0 notes

Text

The danger is that I shall get fond of him if he goes on letting me insult him...

Rosemary Tonks, The Bloater

0 notes

Text

The Sofas, Fogs, and Cinemas

Rosemary Tonks

I have lived it, and lived it,

My nervous, luxury civilisation,

My sugar-loving nerves have battered me to pieces.

... Their idea of literature is hopeless.

Make them drink their own poetry!

Let them eat their gross novel, full of mud.

It’s quiet; just the fresh, chilly weather ... and he

Gets up from his dead bedroom, and comes in here

And digs himself into the sofa.

He stays there up to two hours in the hole – and talks

– Straight into the large subjects, he faces up to everything

It’s ...... damnably depressing.

(That great lavatory coat...the cigarillo burning

In the little dish... And when he calls out: ‘Ha!’

Madness! – you no longer possess your own furniture.)

On my bad days (and I’m being broken

At this very moment) I speak of my ambitions ... and he

Becomes intensely gloomy, with the look of something jugged,

Morose, sour, mouldering away, with lockjaw ....

I grow coarser; and more modern (I, who am driven mad

By my ideas; who go nowhere;

Who dare not leave my frontdoor, lest an idea ...)

All right. I admit everything, everything!

Oh yes, the opera (Ah, but the cinema)

He particularly enjoys it, enjoys it horribly, when someone’s ill

At the last minute; and they specially fly in

A new, gigantic, Dutch soprano. He wants to help her

With her arias. Old goat! Blasphemer!

He wants to help her with her arias!

No, I ... go to the cinema,

I particularly like it when the fog is thick, the street

Is like a hole in an old coat, and the light is brown as laudanum.

... the fogs! the fogs! The cinemas

Where the criminal shadow-literature flickers over our faces,

The screen is spread out like a thundercloud – that bangs