#Prison architect designs

Text

Prison architect designs

What next? Concentration Camp Tycoon? As a matter of act, a game along those lines already exists: it's called Train and it was designed in 2009 by Brenda Braithwaite. When Prison Architect was first announced, some considered it to be in poor taste. (The UK has no cause to be smug in this area, incidentally, and the situation here is worsening daily.) The racist torture hives that America calls prisons are a deep stain on the country's soul, made exponentially more vile by the fact that many are run for private profit. It is rife with violence, hard drugs, brutality and squalor. Prison Architect might have a pretty, toy-like look and simple, cute moving shapes for its inmates, guards and workers, but its aim is detailed realism in the present-day world of the (American) prison system. But the former also had a jokey fantasy setting, and the latter was cartoonish and farcial. Dungeon Keeper, an evergreen classic of the genre, was a raucous exercise in literal anti-heroism and bathed in gore and torture. Management simulators have ventured into some pretty dark territory in the past. Games can be designed to make powerful moral arguments Prison Architect follows in the grand tradition of design and management games such as Dungeon Keeper, Railroad Tycoon and Theme Hospital, which have been keeping this writer entertained since he was a teenager. So what we now have is the polished, stable, fleshed-out, beautiful version of a project that has already sold more than a million units, earned almost $20 million, and has been attracting attention, accolades and controversy for months. This allows players to buy test versions of the game as a way of raising funds and getting early feedback on game mechanics and bugs.

"Officially" because Introversion is a small, independent developer and, as is now fairly common practice for small, independent developers, has had the game in open alpha for several years. Related story Mas d’Enric Penitentiary by AiB and PSPĪrchitects can now rehearse this question in the comfort of their own home with Prison Architect, a new PC game from Introversion Software, which was officially released this month. "Would you design a prison?" has become one of the profession's ethical shibboleths. This laissez-faire approach isn't exactly impressive, but she's right in one regard: architects do self-select. Architects self-select, depending on where they feel they can contribute best." 'Would you design a prison?' has become one of the profession's ethical shibboleths "Members with deeply embedded beliefs will avoid designing those building types and leave it to their colleagues. "It's just not something we want to determine as a collective," former AIA president Helene Combs Dreiling told the New York Times's architecture critic Michael Kimmelman. It's a debate that is echoed, at varying volumes, wherever architecture is practised and prisons are built – which is to say, pretty much everywhere.

The petition, which attracted more than 2,000 signatures, and the AIA's response, briefly focused a now long-established debate about the culpability of architects in supporting the atrocious moral swamp that is the American prison system. At the beginning of this year, the American Institute of Architects rejected a petition calling for it to censure architects who designed solitary confinement cells and death chambers for American prisons.

0 notes

Text

HOLY SHIT I WAS RECOMMENDED A VIDEO ABOUT A THING MY HIGH SCHOOL DID. I’d recognize the shitty design anywhere.

#literally was a rumor that the building was designed by a prison architect#it wasnt but#not hard to see how that started#its a box#no i will not elaborate iykyk

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

How a Man in Prison Stole Millions From Billionaires

With smuggled cell phones and a handful of accomplices, Arthur Lee Cofield, Jr., took money from large bank accounts and bought houses, cars, clothes, and gold.

— By Charles Bethea | August 28, 2023

Illustration By Max Guther

Early in 2020, the architect Scott West got a call at his office, in Atlanta, from a prospective client who said that his name was Archie Lee. West designs luxurious houses in a spare, angular style one might call millionaire modern. Lee wanted one. That June, West found an appealing property in Buckhead—an upscale part of North Atlanta that attracts both old money and new—and told Lee it might be a good spot for them to build. Lee arranged for his wife to meet West there.

She arrived in a white Range Rover, wearing Gucci and Prada, and carrying a small dog in her purse. She said her name was Indiana. As she walked around the property, she FaceTimed her husband, then told West that it wasn’t quite what they had in mind, and that he should keep looking. West said that he’d need a retainer. She reached into her purse and pulled out five thousand dollars. “That was a little unusual,” West recalled.

Later that summer, Lee called again, with a new proposal. His wife, he said, had been “driving around Buckhead, and she came across this amazing modern house and thought it had to be a Scott West house.” She was right. The house, on Randall Mill Road, wasn’t quite finished, and it had not been on the market—but Lee told West that he was already buying it, from the owner, for four and a half million dollars. Now he wanted West to redo the landscaping and the outdoor pool, plus some interior finishes. West took another retainer, but he had other clients to attend to, and Lee grew impatient. Eventually, Lee asked West for his money back and began planning the renovations without him.

The renovations were supervised, as far as the neighbors could tell, by Indiana’s father, Eldridge Bennett, a sturdy man who drove an old Jaguar and wore a pair of dog tags around his neck. Neighbors described him as friendly but hard to pin down. He told one that he worked in the concrete business—and that he’d been on the team that killed Osama bin Laden—but gave another a card that identified him as the marketing manager for an accounting company. This neighbor noticed that a wine tower in the house was being stocked with Moët & Chandon (“thousands of bottles, like, twenty feet tall”) and asked who was paying for it all. Bennett told him that the new owner was in California, “working on music stuff.” Like many residents of Randall Mill Road, this neighbor is white. The Bennetts are Black. “It seemed like they didn’t come from money,” the neighbor said, “but they had sure found a lot of it.”

A closing meeting was scheduled for early September at a bank in Alpharetta, north of the city. By then, Lee and the Bennetts had made three down payments on the house, totalling seven hundred thousand dollars, most of which Indiana and Eldridge had delivered in rubber-banded bundles of cash. Lee told the seller’s attorney that they would deliver the rest—about three and a half million dollars—in similar fashion, at the closing. He couldn’t be there himself, he said, because he was still busy in California. (Lee, the lawyer recalled, said that he “represented a variety of entertainers and got paid in a variety of ways,” and also that he’d made money in Bitcoin.)

Because so much cash was going to be exchanged, the bank arranged for the closing to be held in its kitchen and break room, which offered some privacy. The bank also asked a local cop to be present. At the appointed time, Eldridge and a younger man carried several black duffelbags into the room and began handing stacks of bills to a bank employee, who spent the next three and a half hours counting them all. Afterward, on the phone, Lee asked the seller to complete a few punch items on the property. When the seller got to the house, he noticed that the door to a large safe that he’d installed—and which he’d left open—was locked, and that the combination had already been changed.

A few weeks after the close, Lee sent Scott West another e-mail. “I’m buying land in a month or so to start planning on designing a house 100% to my liking,” he wrote. “I want to give you the ball and let you run the entire project. Let you go insane on your ideas. I’m thinking of a seven million dollar budget just for the house, not including the landscaping.” He suggested that the two of them “become a team.” West replied, as gently as he could, that he was too busy. A week before, he’d received a call from a federal agent, who asked him if he knew a man named Arthur Cofield. West said that he did not, and the agent began rattling off names. “He kept going through aliases until he said ‘Archie Lee,’ ” West told me. Arthur Lee Cofield, Jr., the agent said, resided in a maximum-security prison in Georgia. He had been incarcerated for more than a decade.

Arthur Cofield probably stole more money from behind bars than any inmate in American history. His methods were fairly straightforward, if distinctly contemporary: using cell phones that he’d had smuggled into prison, and relying on a network of people on the outside, he accessed the bank accounts of the very wealthy, then used their money to make large purchases—often of gold, which he’d typically have shipped to Atlanta, where it was picked up by his accomplices. Some of that gold he seems to have converted to cash: he and his associates bought cars, houses, and clothes, and they flaunted all of it on social media. (At one point, Cofield wrote on Instagram, “Making millions from bed.”) By the time Cofield was charged—with identity theft and money laundering, among other crimes—he had likely stolen at least fifteen million dollars. “I don’t know of anything that’s ever happened in an institutional setting of this magnitude,” Brenda Smith, a law professor at American University who has researched crime in prison, told me. Cofield, she said, was “something of an innovator.”

He didn’t arrive in prison as a man with a lot of connections or a history of fraud. He didn’t have much history at all—he was just sixteen. He had grown up in East Point, a poor and predominantly Black suburb southeast of Atlanta. A number of gangs operate there, but, if Cofield belonged to one back then, no one seems to have noticed. When he was a kid, dirt bikes were his passion. He began riding at a motocross track northwest of the city when he was little; at eight, he finished fourth at the Amateur National Motocross Championship, in Tennessee. A friend from his riding days told me that Cofield stuck out among the motocross crowd for two reasons: “He was African American, and he was freaking badass.” Cofield told the friend that he was called racial slurs by fans and other racers. “Nasty stuff,” the friend said. “It almost fuelled the fire.”

Competing in motocross is expensive, and Cofield’s father, who mostly made his living hanging drywall, converted a box truck into a trailer, with living quarters, so that the family could get Arthur to the big races. At one of those races, when Cofield was about fourteen, a gate collector noticed that more than eight thousand dollars had gone missing from the till, and told the track’s operators that Cofield had been lingering nearby when it vanished. “We went into Arthur’s mobile home and he had the money hidden in there,” a member of the family who owned the track told me. The family was fond of Cofield and his father, and declined to press charges, but it was the last time that they saw the Cofields at a race. Soon, Cofield began to “slack off from racing,” his friend said, adding, “That’s when everything happened.”

In October, 2007, when Cofield was sixteen, he brought a gun into a bank in Douglasville, just west of Atlanta, and demanded that the tellers give him all the money they had. He walked out with twenty-six hundred dollars and headed for a stolen station wagon, where a friend of his older brother’s was behind the wheel. A smoke-and-dye pack hidden in a stack of bills exploded as he got into the car; the young men crashed soon after getting on the road. They ran but didn’t get far. The driver was sentenced to ten years and was paroled after three. Cofield got a fourteen-year prison sentence and ended up in a maximum-security facility in middle Georgia.

It took a few years and a couple of prison transfers before he became a more successful thief. Early in 2010, Cofield sustained cuts on his arm from a razor blade; according to a prison report, he initially told a guard that he’d cut himself shaving. But he later handwrote a carefully argued lawsuit alleging that he’d been attacked by a fellow-inmate and that prison staff had not only failed to intervene but knowingly allowed the assault to take place. Citing the damage to his motocross career, which he slightly embellished, he demanded more than a million dollars. A judge dismissed the suit on procedural grounds. Cofield was sent to another prison. Later that year, he was mailed a package containing bottles of shampoo and conditioner. Inside each bottle was a cell phone.

As smartphones have become more powerful and more ubiquitous, the barrier between life in prison and life on the outside has become more porous. Thousands of phones are confiscated from Georgia prisons every year, according to the state’s Department of Corrections. Prison guards are generally not well paid, and they are often bribed to assist in the smuggling or simply to look the other way. Most people in prison use phones in innocuous ways: to talk to loved ones, for instance—prison phone services are notoriously expensive—and to keep up with what’s going on in the world. In 2010, inmates at seven Georgia prisons used smuggled cell phones to organize a protest for better living conditions. But phones are also used to carry out drug dealing and other crimes. Authorities have recognized this problem for more than a decade now, but the phones keep coming.

In the years that followed Cofield’s first prison transfer, he was found with phones in his soapbox, taped around his waist, and inside his undershorts. Many more seem to have gone undiscovered. On one occasion, he told a guard seizing yet another phone, “I don’t give a fuck about that phone. I’ve had hundreds of phones.”

In 2014, he was transferred again, to Telfair State Prison, in south Georgia. There he met a man named Devinchio Rogers, who was serving a seven-year sentence for manslaughter. Rogers grew up not far from Cofield, but he was a few years older, and flashier. Cofield is stocky and gruff—he was lean and muscular in his motocross days but put on weight in prison. Rogers was tall and stylish. He shared Cofield’s knack for getting cell phones behind bars. He’d attained some brief local notoriety in 2011, when he began tweeting from inside Fulton County Jail. (His tweets were “littered with foul language and pictures of prison food, something that appears to be marijuana and himself,” a local TV station reported.)

Cofield and Rogers started a crew, which they called yap, for Young and Paid. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of similar crews in Atlanta, many with three-letter names, most of them small-time. They are typically founded in prisons or on particular city blocks. Some are involved in the drug trade; some flaunt a connection to nationally known gangs, such as the Bloods; some aspire to be movers and shakers in hip-hop. The most famous of these crews is Y.S.L., which was allegedly co-founded by the rapper Young Thug, whose real name is Jeffery Williams. Like Cofield, Williams, who is Cofield’s age, grew up in East Point. He and more than two dozen other alleged members of Y.S.L. are currently facing rico charges in Fulton County. They stand accused of crimes that range from drug dealing to murder. (Williams, who started a record label also called Y.S.L., has denied involvement in criminal activity.)

Cofield and Rogers adopted aliases, like hip-hop m.c.s, incorporating the name of their crew. Rogers went by yap Football, or just Ball. Cofield called himself yap Lavish. In March, 2017, they filed paperwork to establish yap Entertainment as a limited-liability partnership in the state of Georgia. yap Entertainment, according to its filing, planned to provide “agents and managers for artists, athletes, entertainers, and other public figures.” Within about a year of the partnership’s formal creation, three hundred thousand dollars went missing from a bank account in Alabama.

The Alabama Theft was probably not Cofield’s first big score, but it is the earliest, from his prison career, of which he has been formally accused. The target was a wealthy doctor. Cofield got hold of the doctor’s personal information, logged in to the doctor’s bank account, used money from the account to buy gold, and had the gold shipped to a UPS center near Atlanta, where someone else picked it up for him. According to a detective who has investigated Cofield and Rogers, the Secret Service, during the previous several months, had noticed a string of similar thefts, and began making inquiries. (The agency, which has jurisdiction over some federal financial crimes, declined to comment.) Eventually, the agency opened an investigation, and dubbed the case Gold Rush.

The year that followed, 2018, was a big one for Cofield and Rogers. They were, evidently, beginning to bring in a lot of money, and they also seem to have been actively recruiting associates. This recruitment could allegedly be quite direct. A young woman named Selena Holmes was approached by a friend, who, according to Holmes’s former lawyer, said, “Look, there’s these guys in prison. They’re really rich. And all you got to do is talk to them. They’ll look out for you.” A few days later, the lawyer said, Cofield called Holmes on the phone. She was nineteen and had grown up poor on the west side of Atlanta. (Cofield may have known her through a family connection.) She had dropped out of high school after becoming pregnant and was working at Panera. Shortly after Cofield called, according to the detective, a man named Keonte Melton found her outside work and handed her fifteen thousand dollars. (Melton could not be reached for comment.)

Soon, Holmes and Cofield were spending hours together on the phone. She got a yap tattoo and people began calling her yap Missus—the queen to Cofield’s king. He bought her a Mercedes-Benz and rented a penthouse apartment for her in Buckhead. He also flew her first class to Los Angeles, to shop on Rodeo Drive, where she bought a three-thousand-dollar purse. (The detective believes that Holmes was running yap-related errands.)

In May, 2018, a video was posted to YouTube of a pool party that yap threw at a “secret location” that looks a lot like a Buckhead mansion. The party was hosted by an aspiring rapper, Anteria Gordon, who had adopted the name yap Moncho. Gordon, in the front seat of a Bentley, gives a shout-out to Lavish. “Nobody doing it bigger than us,” he says later, amid drinking and twerking revellers. Around this time, Gordon released a single called “Lavish,” mostly about spending large amounts of money (“two hundred thousand, blow it on a stripper”), and gave an interview to the YouTube channel Hood Affairs, sitting in an ornate gold chair at the same mansion where the party was held. Wearing a diamond chain that spelled “yap,” Gordon shows his interviewer around the mansion, praising Missus and thanking Lavish, seeming to call him “the most richest motherfucker in the city.”

In June, Rogers was released from prison, and quickly began throwing money around, according to a person who knew him before he was incarcerated. “He bought four hundred and thirty-six pairs of Reeboks,” this person told me. “He had a line around Greenbriar Mall—people lined up to get those shoes that he paid for. He was giving them to kids.” This person also saw pictures of Rogers “standing on top of Mercedes-Benz trucks” and “living in penthouses.” (In one of them, there was a shark tank.) A lawyer for Rogers told me, “I’ve seen the photos, but he gets paid a lot because he’s attractive and he does social-media posts wearing different clothes and things of that nature. I don’t know if it’s called ‘influencing,’ but he’s a fashionista type.” As for yap, the lawyer said, “their business did sign people and do social media and marketing—club things—and that’s what our client Mr. Rogers is good at.”

The detective who has investigated Cofield and Rogers believes that the two men were both building a brand and enlisting accomplices—mostly young men who had spent time in prison, plus a handful of young women with whom one of them had been romantically involved. The detective pointed, for example, to an attempted theft for which neither man was charged. A woman who worked at Wells Fargo, in Atlanta—and who had, according to the detective, exchanged “affectionate text messages” with Rogers—gave Keonte Melton access to a large account at the bank in August, 2018. (Melton is the man who allegedly delivered Cofield’s cash to Selena Holmes.) The account belonged to one of the family businesses of John Portman, a famous Atlanta architect and developer who had died several months before. Melton tried to withdraw eight hundred and fifty thousand dollars; another Wells Fargo employee called two of the account’s signatories, who said that they had no idea who this withdrawer was. Melton was charged with an attempt to commit a felony; he pleaded guilty and is on probation.

The woman left Wells Fargo for another bank, then went into real estate. (She has also appeared in multiple episodes of the reality show “Love & Hip Hop: Atlanta.”) When I reached her on the phone, she denied knowing any of the men involved. She does follow Rogers on Instagram; on her own account, she often posts pictures of herself in Lamborghinis or wearing diamond-encrusted watches, not only in Atlanta but in places like Dubai and Aruba. She was questioned by police in connection with the Wells Fargo theft but was never charged. (As part of Melton’s plea deal, he was ordered not to have contact with her.) “It was like a big ring that all of them were part of,” the detective said.

In the summer of 2018, Cofield heard that Selena Holmes was growing close to a man she had met named Antoris Young. Cofield, perhaps flexing his growing power and resources, allegedly hired someone to kill him. The hit man, Teontre Crowley, tailed Young in a car; Rogers and Holmes followed in a separate vehicle so that Holmes could I.D. the target. Prosecutors say that the pair was on the phone with Cofield so he could be sure that the hit was carried out. Crowley shot Young around ten times outside a recording studio. Young survived but was paralyzed from the waist down.

Days later, according to the detective, Rogers threw a birthday party for Cofield at Club Crucial, on Atlanta’s west side. “They had ‘Lavish’ on the club’s marquee,” the detective told me. Within months, Holmes, Rogers, and Crowley had been arrested for the shooting. All pleaded guilty and are now in prison. (Cofield was also charged, and pleaded not guilty; the case against him is ongoing.) A lawyer for Holmes maintained that she had been forced at gunpoint to help Crowley identify Young; Holmes later filed to withdraw her guilty plea but was denied. Last summer, at a hearing related to her sentence, an investigator said, of Cofield, “He finds these women from the outside and kind of pretends like he owns them from the inside, using money and things like that, and they enjoy the life style, so they go along with it. And they’re O.K. with it, as long as the money is good.”

“I Was a Pretty Girl in a Strip Club,” Eliayah Bennett, who goes by Indiana professionally, told me recently. “I wouldn’t say that I’m, like, a million-followers type of girl. But people know me. I danced for big people and stuff like that.” I had asked her how she and Cofield met. The full story would “probably take about two hours,” she said. I asked for the CliffsNotes. “Somebody seen my picture,” she said. “I don’t know who it was. And people was trying to find me. I was out of town. I think I was dancing in Miami or something, because, in the summer, Georgia gets slow. So one of my homegirls, they would have, like, stripper parties and I was invited to one. And that was it.” I waited for more. “It’s a real long story,” she said.

The detective offered me a shorter version: Cofield “wanted Selena to recruit a stripper and for them to have a girl-on-girl encounter in front of him on FaceTime,” the detective said, explaining that this detail came from Holmes. “That’s how Eliayah got involved. Then she and Cofield developed a relationship behind Selena’s back.”

Bennett told me that she and Holmes are very different. She said she comes from a more middle-class background and went to a good school—a charter school just north of the city. But, like Holmes, she began to live more fabulously after coming into Cofield’s orbit. She moved into a Buckhead home with separate floors for her mother and her father; she bought two Range Rovers and a four-hundred-thousand-dollar Rolls-Royce S.U.V.; she got breast implants and a nose job, though she said she funded those procedures herself. (“I’ve always had my own before Arthur,” she told me.) “When I talk to him, really it’s just to see me naked,” she told an investigator, downplaying the role of money in their relationship. “And that’s about it. And we’ll watch movies together.” They liked true crime, she told me.

She and Cofield were married, online, in July, 2019. Afterward, she was approved to handle his finances. As his spouse, she received another privilege: she could no longer be compelled to testify against him. Meanwhile, Cofield’s reputation within the prison system continued to grow. A month after his marriage, Cofield was moved temporarily to Fulton County Jail to attend a court hearing related to the Antoris Young shooting. “The jail was buzzing,” a person familiar with the case told me. “You could hear it on calls from inmates using the jail phone system: ‘That guy Lavish is here!’ ”

Cofield was transferred to the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison and later placed in solitary confinement in its Special Management Unit—a notorious facility that had been described by a social psychologist, a few years earlier, as “one of the harshest and most draconian such facilities I have seen in operation anywhere in the country.” There, he was kept alone for around twenty-three hours a day. But every prison has guards, and smuggling happens at all of them. Jose Morales was the warden of the prison when Cofield arrived. He described him as an unusual inmate. “The others were boisterous, loud, violent,” he told me. “Cofield was the opposite of that. Very cordial, very respectful.” Morales thought he was up to something.

In September, 2019, the Secret Service was contacted by Fidelity Bank. Someone had breached a large account belonging to Nicole Wertheim, the wife of the billionaire investor Herbert Wertheim. This person had used more than two million dollars from the account to purchase gold coins and had then had the coins shipped to a suburb near the Atlanta airport. Investigators traced the I.P. addresses of devices that had accessed the account: one led to an apartment building in Buckhead, and another led to a Verizon cell tower near the Special Management Unit of the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison.

Investigators informed Georgia’s Department of Corrections, which began looking for the second device. In November, guards at the Special Management Unit found two phones on Cofield, including one hidden in the rolls of his stomach. They gave the phones to prison investigators, who matched one of them to the Wertheim breach. The phone had a virtual private network that could mask its user’s identity by routing its connection through a private server, and it had a free app called TextNow, which is marketed as a provider of affordable phone service but can be used to disguise the number that a call or text is coming from. It also had several saved Yahoo and Gmail accounts that incorporated, presumably for the purposes of impersonation, the names of some of the richest men in the country, including the real-estate tycoon Sam Zell, the media mogul Sumner Redstone, the hair-care entrepreneur John Paul DeJoria, the businessman Thomas Secunda, and multiple founders of the global investment firm the Carlyle Group.

Cofield had apparently narrowed his targets to aging billionaires: men who were rich enough to not notice if millions went missing—and old enough, perhaps, not to have set up personal online-banking accounts. Secunda, who is in his late sixties, was the youngest person on the list. Two men on the list have since died: Redstone, less than a year later, at ninety-seven, and Zell, at the age of eighty-one, this past May. Before Redstone died, his Fidelity account was breached twice. (Secunda and the founders of the Carlyle Group declined to comment for this story; DeJoria told me that he hadn’t heard anything about Cofield’s scheme.)

Having identified a likely suspect in Georgia, the Secret Service turned the case over to Scott McAfee, an Assistant U.S. Attorney in the state’s Northern District. In August, 2020, one of McAfee’s investigators was contacted by the brokerage firm Charles Schwab. Two people, working in tandem, had successfully impersonated the ninety-five-year-old clothier and Hollywood producer Sidney Kimmel and his wife, Caroline Davis. Kimmel, who had recently executive-produced “Crazy Rich Asians,” reportedly had a net worth of around one and a half billion dollars, and had several accounts with Schwab. Cofield created an online brokerage account in Kimmel’s name, then called Schwab, claiming to be Kimmel, in order to connect the new account to a checking account. Over the phone, he provided Kimmel’s Social Security number, his mother’s maiden name, his date of birth, and home address. Three days after that, someone claiming to be Kimmel’s wife called Schwab and asked about making a wire transfer. Half an hour later, Cofield submitted a signed form authorizing such a transfer. The transfer was for eleven million dollars. It was used to purchase gold coins.

An investigator who has listened to these phone calls told me that the vocal impersonations were not sophisticated. “It was a bad old man’s voice,” he said, of Cofield’s Kimmel. “Just gravelly.” Even so, he said, the representative from Schwab was deferential. “I don’t know if they checked every single security-protocol box before transferring that money,” the investigator said. “It really seemed, like, ‘Yes, Mr. Kimmel. Yes, sir.’ ” Schwab, at the phony Kimmel’s behest, wired funds to a company called Money Metals Exchange L.L.C., in Idaho. This company was also deferential, the investigator told me: “They’re, like, ‘Folks, I’ve researched this Sidney Kimmel guy, this could be a really good client. Let’s give him the V.I.P. treatment! Let’s get him that gold!’ ” (When I asked the company’s director, on the phone, for comment, he hung up.)

Illustration By Max Guther

Cofield, still impersonating Kimmel, contacted security and logistics firms capable of transporting highly valuable assets from Idaho to Atlanta; that job was ultimately subcontracted to a man named Michael Blake. One night in June, just after 2 a.m., Blake landed on a private runway in Atlanta, during a heavy storm, with millions in gold coins in tow. He was met by two men in a Jeep Cherokee. The car was a rental, with Florida plates, which struck Blake as a little off. The driver showed him a license, and Blake loaded the gold into the car. He asked for a ride to a nearby hotel, due to the late hour and the weather, but the driver said no.

After the handoff, Cofield texted Blake with instructions to delete any photos that he had taken of the car or the driver’s license—and to send him a screenshot of his photo library and his deleted-files folder as proof. Blake, who had Googled Kimmel, thought this was an odd request to get, in the middle of the night, from a ninetysomething-year-old man. He complied, but he also kept a screenshot of the folder with the photos for himself.

Later, Cofield initiated another Schwab transfer, of eight and a half million dollars, again for the purchase of gold. But, before the transfer was complete, he cancelled the order and asked Schwab for a credit-line increase instead. At that point, a Schwab employee contacted a lawyer for Kimmel, who told Schwab that neither he nor his client had requested the transfer, or the previous one. (Kimmel’s lawyer did not respond to requests for comment. Last fall, he told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that neither he nor Kimmel had knowledge of anything related to the theft, adding, “Mr. Kimmel was unaffected by whatever occurred.” According to the investigator, the Kimmel breach alone doubled Schwab’s average annual loss from fraud. Schwab, which reimbursed Kimmel, declined to comment on this figure.)

In the meantime, guards at Cofield’s prison found two more phones in his cell in the S.M.U. and gave them to a prison forensics unit. The timing was fortunate: Cofield had been using the TextNow app, on which messages can permanently expire, to communicate with Money Metals Exchange and with someone listed in the phone as Yum. Prosecutors believe that Yum is a bank employee who provided Cofield with a driver’s license and a utility bill that belonged to Kimmel. Federal investigators also contacted Michael Blake, who sent them his screenshot of the I.D. that the driver in the Jeep Cherokee had shown him. Investigators enlarged the screenshot and determined that the photograph on the I.D. was of Eldridge Bennett.

Cofield Was Indicted in December, 2020, and charged with aggravated identity theft, conspiracy to commit bank fraud, money laundering, and conspiracy to commit money laundering. His lawyer, a prominent Atlanta attorney named Steven Sadow, declined to comment. (Sadow currently represents Donald Trump in the ex-President’s election-interference case in Georgia; Cofield’s legal team also includes Drew Findling, who represented Trump until Trump replaced him with Sadow, in late August.) Eldridge and Eliayah Bennett were indicted on conspiracy and money-laundering charges.

Soon afterward, a resident of Randall Mill Road was working at his kitchen table when he looked out the window. “Up comes a white locksmith truck followed by maybe ten black unmarked S.U.V.s,” he said. Armed federal agents circled the house. “I’m, like, ‘This ain’t good.’ It was right out of the movies.” The agents couldn’t get the house’s large safe open; McAfee, the Assistant U.S. Attorney, became convinced that that’s where the gold was. He tried, unsuccessfully, to subpoena the man who designed the safe, in Arizona. (“He was, like, ‘You’re not the real government,’ ” McAfee told me.) A team of six safecrackers finally got it open. It was empty. The vast majority of the gold that Cofield is known to have purchased with stolen money has never been accounted for. Laundering tens of millions of dollars in gold coins is not easy—it often requires dealing with transnational organizations capable of smuggling the gold out of the country.

Agents also searched the Bennetts’ place, seizing electronic devices, a Range Rover, a firearm, three hundred thousand dollars, and six Buffalo Tribute Proof gold coins, which were found on Eliayah’s desk. Cofield entrusted his wife with much of what he stole, and text messages between the two, discovered by investigators, suggest that this strained their relationship: on several occasions, Cofield seems to have become convinced that Bennett was going to steal, in turn, from him. “I get why u mad,” Bennett wrote at one point. “Cause U think I’ll steal a house from u. Like I don’t steal money from u I had Millions in my house for months. I know u love that house probably more than me I’ll never do that to u.”

“Phones were the key to his success,” Scott McAfee said, of Cofield, “but also his downfall. For me, it’s all there.”

A Few Months after Cofield was indicted, McAfee was appointed inspector general of Georgia. He handed the case off to another U.S. Attorney, who left the post after two years and then handed the case off yet again. McAfee’s successors both declined to comment for this story. (McAfee has since become a judge in Fulton County’s Superior Court. In August, he was appointed to oversee Donald Trump’s election-interference trial.)

In March, I got a call from Eliayah Bennett, who told me that she had Cofield on the other line. She then patched him through. Calmly and firmly, with a cool Georgia drawl, he told me that he was going to take a plea on the fraud and conspiracy charges. With Bennett listening in, the only matter he seemed intent on discussing, apart from the plea, was his connection to Selena Holmes, which he insisted did not exist. “In the story, if you don’t mind, don’t put this lady’s name anywhere close to mine, because she don’t know me,” he said.

The detective who investigated Cofield and Rogers described listening to hundreds of calls that Holmes made from a county-jail phone—many of which, the detective said, were obviously with Cofield. “He’d disguise his voice like he was an old lady when they talked, the same way he disguised it as an old man when he called the banks to take over the accounts. It was crazy Madea-type stuff,” the detective added, referring to the grandmother played, in several movies, by Atlanta’s own Tyler Perry. “They’d usually try to talk in code, and she’d slip up every now and then. When she’d get really angry, she’d write e-mails saying she was gonna tell everything that happened.”

Several people I spoke to expressed a fear that Cofield could try to retaliate against anyone whom he perceives to be working against him. He has, after all, been charged with ordering the murder of one person, and he committed most of his crimes while detained in maximum-security prisons—it’s not clear what authorities can do to make things more difficult for him than they are. Earlier this year, Georgia’s attorney general, Chris Carr, announced that he and twenty-one other attorneys general were pushing Congress to pass a law allowing states to jam phone reception in correctional facilities, which is forbidden as a result of the Communications Act of 1934. Todd Clear, a criminal-justice professor at Rutgers, told me that the better approach would be to allow people in prison to have cell phones, and to closely monitor their use. This, he noted, would also make prison life more humane.

A month after I spoke with Cofield, I attended his plea hearing, at a downtown courthouse. His high-priced lawyers made small talk about their ties while he hunched between them in his jumpsuit. He has a large tattoo on his neck, which was partly visible: “Laugh now, cry later,” it reads, alongside drawings of clowns.

After he pleaded guilty, lawyers for the government laid out the agreement that they had reached with him: a hundred and fifty-one months for fraud committed in Georgia and Alabama. The judge asked Cofield to explain what he’d done.

“What did I do,” he began. He took a deep breath. Without visible emotion, he described gaining access to bank accounts belonging to Sidney Kimmel and to the doctor in Alabama, using their funds to buy gold coins, and shipping the coins to Atlanta. “I got possession of it,” he started to say, when one of his attorneys cut him off. “I think that’s enough,” the lawyer said. The judge accepted this, then shook his head. “If you would have taken the ability and knowledge you have and put it towards something that was legal and right—” he said, in Cofield’s direction.

“I would be investing my money with him,” one of the lawyers said.

Eliayah Bennett, who has not yet entered a plea in her case, sat a few rows behind Cofield in the gallery. (Her father, who declined to comment for this story, has pleaded guilty and is awaiting sentencing.) Cofield smiled at her before a U.S. marshal escorted him out of the room. Later, the detective told me that another phone had recently been found in Cofield’s cell, and that he’d been Googling “U.S. marshal uniforms.” The detective suspected that he was trying to formulate an escape—that he wanted to get back to the free world, where he hasn’t set foot since he was sixteen. Devinchio Rogers is now in Ware State Prison, in south Georgia. His lawyer told me that, in July, he was stabbed multiple times. He is currently recovering, the lawyer said.

On one of my last visits to the house on Randall Mill Road, I saw that weeds had grown in the yard and around the unfinished pool. “Someone smashed a basement window,” a neighbor told me. “It’s attracted lots of activity and gawkers.” Neighbors said that they had also seen Eliayah Bennett around, late last year, in a Mercedes. “She was taking everything that wasn’t screwed down to the ground,” one said (including the Moëts). Bennett has opened a business in a North Atlanta strip mall offering facials and ombré brows. When I asked her on the phone whether she’d been by the house, she said, “I don’t want to talk about that.” Earlier this year, the government seized the property and put it on the market for around two and a half million dollars. It went under contract quickly. The new owner is an ophthalmologist. Proceeds will go to Cofield’s victims.

When I visited, it had not yet sold. As I stood outside, a black Lamborghini pulled up and parked nearby. Two well-dressed young men got out and ventured onto the property. When they returned to the street, one of them said to me, “The guy who built this house is in prison. Have you walked up on it? It’s nice.” This man turned out to be a real music producer, with the stage name of BricksDaMane. He mentioned his work with Drake, Future, and Lil Baby. (The Lamborghini was his.) I told him that I’d spoken with the architect who designed the house, and the producer asked me for his number. He wanted to chat with him, he said. He had some ideas for how it might be finished. ♦

#Georgia#Crime#Fraud#Scams#Prison#Millions#Billionaires#Smuggling | Cell Phones 📱#Arthur Lee Cofield#Money#Large Bank Accounts#Purchase: Houses | Cars | Clothes | Gold#Charles Bethea | The New Yorker#Max Guther#Lamborghini#Architect | Design Houses 🏠

0 notes

Text

The pictures on Wikipedia of my campus look soooooo nice <3

1 note

·

View note

Text

WELCOME IN MY PRISON - THE ONLY ONE THAT OFFERS ALL PLEASURES OF ALL AMERICAN PENITENTIARIES TOGETHER

It always starts with arrest and being handcuffed at your back. Then you're driven to the police station. There follows the intake, the inevitable alcohol test and the finger prints. As the test is positive your brandnew prison uniform is already waiting for you, the one you will have to wear from now on, as is the bare cell, to spend your first night locked up and think all over. A few days later you're already for trial on your way to court, of course in full restraints, shuffling along with difficulty in your uneasy leg irons, while your wrists in handcuffs are fixed to a thick leather belt around your waist, with which the jailer leads you als a dog on the leash to the dock to get sentenced.... A new, harsh, unknown life with a lot of strict rules is waiting for you!

EXPERIENCE THE UNIQUE AMERICAN WAY OF PRISON LIFE!

I have started this new blog about one of my greatest phantasies: to experience a real American prison from the inside. After being transported to a huge state penitentiary of the maximum security category, surrounded by barbed wire, walls and moats, and the obligatory humiliating stripsearch immediately at arrival, a hidden severe world is welcoming all new inmates for many years to come, offering a lot of rest, partly to be spend in solitary confinement:

barred cells, serious shackles, rattling chains, prison stripes and the chain gang - always secured in full restraints: that's the way i like it!

Be prepared for what you a as new inmate will be confronted with after entering the long, long corridor beyond the reception building. Indeed endless rows and rows of identical barred cells are waiting for new inmates - and one still empty one is reserved exclusively for you!!!

Here you are, your neighbor is already beckoning to you invitingly....

NO FEAR, ONCE YOU'RE INSIDE MY PRISON, YOU WON'T ESCAPE...

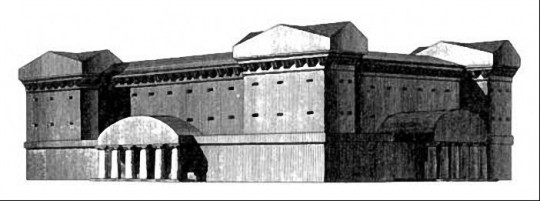

This last picture shows that in earlier times, even outside America, professionals had already given careful thought to terrifying prison architecture from which there was no escape. It shows the (never executed) design of the famous French revolutionary architect Claude-Nicholas Ledoux for a prison in Aix-en-Provence from 1786. We do not know exactly what it was supposed to look like from the inside. But the picture suggests the worst. Who would (not) want to stay there for a while? Imagine yourself stored somewhere inside...

#American Prison#prisonexperience#prison#prison cell#jail#prisoner#locked up#prison uniform#shackles#chains#handcuffs#restrained#leg-irons#prison stripes#behind bars#chain gang#full restraints#prison jumpsuit#perp walk#inmate#solitary confinement#handcuffed inmate#barred cell#strip search#prison intake#prisoner transport#American jail

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

// dsmp rp

@sam-and-dream-week day 2 — "warden"

Sam was the one to suggest the prison as an alternative. Mercy, instead of destruction. Life, instead of death. The relief that swelled in Dream’s heart was not fake; there had been a second there, with one life remaining and an axe leveled at his throat, where he had been worried.

But ultimately, there had been nothing to worry about. The plan had worked. Now, safely inside obsidian walls, this was his domain.

“Face forward,” said Sam, shoving Dream onto the bridge. Dream kept walking. There was a grin on his face, one that he wasn't used to anyone being able to see, so he made sure to show it off to his new warden on the way over to his cell. He could play it off as some form of insanity, probably. It might not be too far from the truth.

“So this is my bedroom?” asked Dream, once they had docked. It probably couldn't qualify as a bedroom, seeing as how there was no bed, but the word choice seemed to annoy Sam, and that was good enough for him.

“You already know that,” said Sam, with a world-weary exhaustion. He sounded faltering, almost; unsure of himself. “You helped design it.”

“I did,” Dream agreed. “And you betrayed me.” He made himself actually sound bitter about it, for the show. He wasn't bitter about it. It would be stupid if he was; this was all calculated in his favor, every detail of it. The builder and the mastermind. Sam had no idea who he was dealing with. “How’s it feel? After all this, building this together, you just. Y’know. Stabbed me in the back.”

“I didn’t stab you in the back,” said Sam, mildly disgusted. “You did this to yourself.”

Dream leaned against the wall, one leg up against it. It was difficult not to feel immensely pleased with himself. “Eh. I guess— I guess I did.”

Dismissive, Sam went over to the back corner, heavy armor clanking as he walked. It was good armor. Layers on layers of enchantments over netherite. Dream could give it to him, he did make for a formidable figure.

“Come stand here,” Sam instructed.

Dream did as he was told, although he was in no rush. He knew what Sam wanted him to do. Even as Sam was making his demands, Dream was already reaching up into the hole in the ceiling, setting his spawn. There was a strange tightness in his chest at the knowledge that this was now permanent.

When Sam began walking back towards the bridge, Dream called after him, “Aw, Sam, you’re not staying to hang out?”

Sam paused. Went still. Gods, he was so lost—the perfect architect for the prison had no idea how to actually run it. Like a beautiful bird with no wings. Eventually, though, he shook his head. “Don’t call me that.”

Dream chuckled before he could think it through. “What? Call you what?”

Sam eyed him in warning. “Dream.”

“Sam,” Dream replied. He had no idea what to even do, this was so random. He put a hand on his heart in fake offense.

“Don’t call me that. Don’t call me— Sam. We’re not friends, not after—” He cut himself off. Dream might mock the man for the dramatics if he wasn't so surprised. Maybe Sam did have a backbone after all.

Dream nodded slowly, just once. “Alright,” he said, and he swept as gracefully as he could, with the wounds Tommy had gifted him, into a low bow. “Mister almighty prison warden, sir.”

Sam made a dismissive sound in his throat. “I’ll— be back in an hour,” he said. As he headed for the bridge and back across the gap, Dream realized that Sam hadn't corrected him the second time.

~

[ part 1 | part 2 | part 3 | part 4 | part 5 ]

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

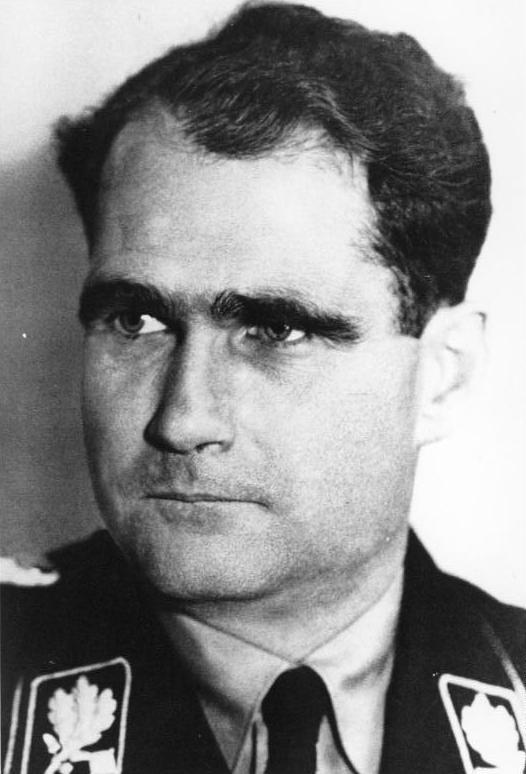

Albert Speer

These are some facts and curiosities about Albert Speer, the Fuhrer's architect:

He was born in March 19, 1905.

He spent his youth in the Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg, the luxurious family home in Heidelberg, and cultivated a wide range of interests, including skiing, mountain excursions, rugby and, above all, mathematics, a discipline towards which he had a fervent passion.

However, due to his father's opposition, Speer ultimately chose to follow in his uncle's footsteps and study to become an architect.

After studying at the University of Karlsruhe, he moved to Munich, where he studied at the Berlin Institute of Technology, under the guidance of the famous architect Heinrich Tessenow.

During his university years Speer never adhered to any specific faith or political opinion.

This substantial "apoliticality" ceased during his discipleship at Tessenow, when Albert was persuaded by some of his students to participate in a Nazi party demonstration

Speer came into contact with Hitler in 1933 through the intercession of Rudolf Hess, by whom the architect was commissioned to design the apparatus for the Nuremberg rally that year.

Despite some initial doubts, the project met with the sympathy of the Führer and, above all, of Joseph Goebbels, who asked him to renew the Ministry of Propaganda.

An immediate understanding was established between Speer and Hitler: the Führer, in fact, was looking for a young architect capable of giving life to his architectural ambitions for a new Germany and therefore immediately included Speer in his closest circles.

Upon Troost's death in 1934, Speer was chosen by Hitler to replace him as chief architect of the Party.

In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt (which occurred in a mysterious plane crash), Hitler surprisingly appointed Speer, who had no experience in industrial production, "Minister for Armaments and War Production".

In 1945 Speer refused to carry out the "scorched earth" strategy (established by the Nero decree), which aimed to completely destroy everything in German territories that would fall into enemy hands.

He was a great friend of Karl Brandt (one of the major exponents of Aktion T4) and they acted to save each other's lives: in 1944 Brandt used his powers as General Commissioner of Medical Services and his friendships to save Speer , already ill, from the assassination attempt plotted by Himmler. In 1945 Speer saved Brandt from the death sentence for ''treason''.

Speer was arrested by Allied forces in Flensburg immediately after the end of the conflict, and tried in Nuremberg on charges of using slave labor to run the German war industry.

He was sentenced to twenty years' imprisonment, to be served in Spandau prison in West Berlin.

Prison and solitary confinement provided Speer with the opportunity to write his memoirs, which made him an international celebrity and a very wealthy man.

He died on September 1, 1981, in London.

Some documents discovered after Speer's death prove, without a shadow of a doubt, that as early as 1943 Speer was aware of what really happened in Auschwitz.

Sources:

Wikipedia: Albert Speer

The Nazi Doctors by Robert Jay Lifton ( for the part of Brandt )

Hitler and his loyalists by Paul Roland

I DON'T SUPPORT NAZISM, FASCISM OR ZIONISM IN ANY WAY, THIS IS AN EDUCATIONAL POST

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

One time we had to evacuate my high school because there was a sawdust fire and once they put tit out there were only like 30 minutes left in the school day but they still made us go back in. The very next day part of the roof collapsed and started leaking chemicals. Sent the school security guard to the hospital. Yes, they did make us go back in after blocking that part of the school off. Also all the gas leaks, but they did send us home for those. Not sure if this is an American school thing or just a my school thing. Fun fact: it was designed by a prison architect!

this did not contain a single normal sentence

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

archangel GAMALIEL, GAOLER OF SIN (they/them)

the main designer / “architect” behind the likes of the Flesh Prison and Panopticon, they are frighteningly skilled at what they do.

whatever life they have is tightly controlled and monitored by the Heavenly Council. it’s unlikely they’ve made a decision for themself in centuries.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Goulburn Correctional Centre, (also known as The Circle, top) is an Australian supermaximum security prison for males. The facility was opened on July 1st 1884. In 2001 a High-Risk Management Correctional Centre was added (middle). The structure incorporates a massive hand-carved sandstone gate and façade based on designs by the colonial architect James Barnet (bottom, picture by Matilda from Wikimedia Commons). The complex is listed on the Register of the National Estate and the New South Wales State Heritage Register as a site of State significance.

Wikipedia

34°44′29″S 149°44′26″E

96 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know why daedalus arc is called that? I guessed it was from some greek mythology but I dont know alot about it :(

Who the hell is daedalus????????

Daedalus is, among other things, the architect who designed the famous Labyrinth in which the Minotaur was imprisoned. In an ironic twist of fate, he was later imprisoned in the same prison he designed. Hence the name Daedalus arc.

#I don’t remember exactly who coined it but I think it arose from dreblr discussions?#daedalus arc#Sam done got daedalus’ed

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Spandau Seven

Despite having a name that sounds like a cheesy nineties boyband or even some form of crappy Justice League, 'The Spandau Seven' was the name given to the Nazi war criminals who had been handed down prison sentences. These seven were held in Spandau Prison in West Berlin, a prison designed to hold 600 inmates, built in 1876 and demolished in 1987 shortly after the death of it's final remaining prisoner, Rudolf Hess. This post will go over the seven Spandau inmates briefly, from prisoner 1 to prisoner 7.

Prisoner No.1: Baldur von Schirach

Baldur von Schirach started off as the Reichsjugendführer (Reich Youth Leader) and Reichsführer for the Hitler Youth. From 1940 until the end of WW2, von Schirach became Gauleiter of Vienna. At the Nuremberg Trials, he was found guilty of Crimes Against Humanity and sentenced to twenty years in prison. He was the youngest of the prisoners, aged 40 when he arrived. Eugene Bird describes him in his book "The Loneliest Man in the World" as a "tall, superior man, hair brushed back from his forehead, an air of aloofness about him." as well as "arrogant" and "knowledgeable". During his time in prison he went through a divorce with his wife Henriette, and had suffered a detached retina which had to be operated on. He was released from prison on the 1st of October 1966 having served his full sentence. He died in 1974, aged just 67.

Prisoner No.2: Karl Dönitz

From 1943, Karl Dönitz (a career naval officer) had replaced Erich Raeder (we'll get to him later) as Commander-in-chief of the navy and Grand Admiral of the Naval High Command. In Hitler's last will and testament, Hitler named Dönitz as the Reichspräsident and the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. Under his order, the instrument of unconditional surrender was signed, marking the end of WW2 in Europe. At the Nuremberg Trials, he was found guilty of Planning, Initiating and Waging Wars of Aggression Crimes Against the Laws of War. He was sentenced to ten years in prison. He was released on the 30th of September 1956, having served his full sentence. He died in 1980, aged 89.

Prisoner No.3: Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin von Neurath was a diplomat by career, having even worked for the SPD Weimar president Friedrich Ebert before the rise of the Nazi Party. He is probably most notable for serving as the Minister for Foreign Affairs under previous chancellor Franz von Papen and then under Hitler, a post which he held from 1932 until 1937 from which he was succeeded by the more compliant Joachim von Ribbentrop. He was subsequently made Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia. He remained a member of the Nazi government until 1943. At the Nuremberg Trials he was found guilty on all four counts, but the tribunal acknowledged that his successor, Joachim von Ribbentrop, was more culpable for the atrocities committed under the Nazis than Neurath was, and so was sentenced to only fifteen years in prison. However, von Neurath was released early on the 6th of November 1954 on the grounds of advanced age and ill health. He died two years later, aged 83.

Prisoner No.4: Erich Raeder

Erich Raeder was the former Grand Admiral and Commander-in-chief of the Navy, prior to the appointment of Karl Dönitz in 1943 after Raeder's resignation. At Nuremberg he was found guilty of Conspiracy to Commit Crimes Against Peace; Planning, Initiating, and Waging Wars of Aggression; and Crimes Against the Laws of War and was sentenced to life imprisonment. Raeder was released early on the grounds of ill-health however on the 26th of September 1955. He died five years later, aged 84.

Prisoner No.5: Albert Speer

Albert Speer had started off as Hitler's architect. He had been commissioned by many of the Nazi inner circle (including Göring, Goebbels and von Ribbentrop) for the design and construction of new homes for them, as well as the 1934 Nuremberg Rally which is arguably his most well-known work. Speer had a very close relationship with Hitler, with some regarding him as Hitler's "only real friend". In 1942, after a plane crash caused the death of Dr Fritz Todt (which Speer had in fact narrowly avoided himself!), Speer was appointed as the Minister of Armaments and Munitions and held this position until the end of the war. At Nuremberg, Speer was found guilty of War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity (on the grounds of his use of slave and forced labour). He was sentenced to twenty years in prison (this was the result of a compromise, some of the judges wanted Speer to hang). Eugene Bird described him in his book as "hard-working, pleasant, resigned to his remaining time in prison." During his time in prison, Speer would keep a record of the distances he walked each day as part of his 'world tour', and had claimed to have walked more than 30,000 kilometres. Speer's parents also died during his incarceration. He was released from prison on the 1st of October 1966 and became a media sensation, giving countless interviews (as well as that one Playboy interview). He died in 1981, aged 76.

Prisoner No.6: Walther Funk

Walther Funk was an economist. He was made Reich Minister for Economic Affairs in 1938 and President of the Reichsbank in 1939, and he held both of these posts until the end of the war. In these roles he signed laws that "aryanized" Jewish property and as Reichsbank President he accepted the forwarding of gold teeth extracted from concentration camp victims to be melted down to yield bullion. At the Nuremberg Trials, he was charged with Planning, Initiating and Waging Wars of Aggression, War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity and was sentenced to life imprisonment. Eugene Bird described him as the "sad clown". Due to failing health he was released on the 16th of May 1957. He died three years later, aged 69.

Prisoner No.7: Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Hess was Deputy Führer of the Nazi Party and third in line to the role of Führer (behind Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring) in the event of Hitler's death up until 1941. In May of 1941, Hess took off in a Messerschmitt from Augsburg and flew to Scotland in an attempt to begin peace talks with the British in the Second World War. His attempt massively backfired and was apprehended as a prisoner of war. While in prison, Hess began to show signs of memory loss and would sometimes refuse to eat as he claimed he was being poisoned by the British. At the Nuremberg Trials he admitted that this amnesia was simulated. He was charged with Conspiracy to Commit Crimes Against Peace and Planing, Initiating, and Waging Wars of Aggression, but due to his flight to Britain he was found not guilty of War Crimes or Crimes Against Humanity. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and the Soviets made sure that he would serve out his full sentence. During his time in prison, Eugene Bird had made an attempt to get close to Hess. He described him in his book as "cantankerous", "difficult to manage", and a "problem-child". From 1966 until his death he was the sole prisoner. Although Raeder and Funk (who were also imprisoned for life) were released from prison on grounds of ill health, this was never the case for Rudolf Hess. In late 1969, Hess was taken into hospital for a stomach ulcer and it seemed as though he was close to death. However, despite this, Hess was not released. Support was growing for Hess's release in Germany as well as three of the four allied nations (UK, US and France). The Soviets vetoed every attempt to release him. Rudolf Hess died in Spandau Prison on the 17th of August 1987 at the age of 93, reportedly of suicide, however debate remains as to whether he really committed suicide or whether he was murdered. Shortly after his death, Spandau Prison was destroyed to prevent it becoming a shrine for Neo-Nazi pilgrimages.

#reichblr#rudolf hess#baldur von schirach#albert speer#Konstantin von neurath#walther funk#karl dönitz#Erich raeder#spandau prison#ww2

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cygnus - Character Analysis and Fanmade lore + Backstory

So to make a decent Cygnus background I need to break down like everything about him. From appearance to character.

shall we start with the appearance?

From top to bottom; a top hat with a swan on it. It’s known that he’s an apprentice to night swan, however swan pieces also appear on jacks outfit. He also has goggles Idrc though

his hair and makeup are both blue; which is Iconas outfit color.

he wears a ruby red trenchcoat, red being jacks signature color.

his vest is pink; like iconas hair. Also a brown button up, it doesn’t mean anything to me, though.

then there’s the pants, those also mean nothing to me.

his whole aesthetic is steampunk, which fits with him being a personal architect for Night Swan.

And, of course, the glove.

I think that gloves can help determine your personality type, his glove is gold meaning his core Values are Tradition, Loyalty, and Family.

Ill get more into that later.

Next: Name.

Cygnus Is both a type of flower and a constellation, a SWAN constellation.

This also fits his character because he’s an apprentice to night swan and Jacks literal name has ROSE in it.

Yeah, his name is a reflection of what his character is.

part 3: LOOORRREEEE

ok so we all know the showdown, and that he was calling out to a lost love. I think he was actually talking about both Icona Shard and Night Swan.

Night Swan we will get into, however I have a whole different post for Icona

Part 3: the clock tower trap and it’s prisoners

it’s pretty known now that I think the tower trap is like wonderland, I’m also going to make separate posts on why and how these prisoners got trapped.

Part 4: Cygnus the City

in DH/SDAMOT, the City that Leda is in is called Cygnus, designed and named after Cygnus.

I also believe he’s made different things for Leda, kind of like the tower, the boat, etc.

NOW THE FUN PART!

actually making up the Backstory.

Cygnus was always a strange man, His name was originated from a family of swans, but unlike a normal swan, Cygnus was the most beautiful swan of his family. In Eternyx, not many people appreciate gracefulness, which was fine for him.

He grew up odd, however. He began to build but not just that, he’d plot odd things, he started mentioning the concept of death before he was even fifteen. His parents never cared, they never even payed attention to their son, which made him even more insane as he grew up.

the early age of 19, he met a woman named Icona Shard. She was a powerful sorceress, but also very flawed and sharp. He saw her in himself, they go on a few dates, fall in love, he becomes soft and loyal to her, eventually Mercury Fahrenheit and Naomi were born, Icona was excited to be a mother, However in fear Cygnus leaves the family.

A month after that he meets another woman, Leda Nox. She was fascinated by him and he was interested in her abilities. They both bond over their connections to swans, they get married, And then Leda strides for nothing but perfection. This turned her into Night Swan, she chose Cygnus as her right hand and personal architect, forcing him to make too much in too little time with no mistakes.

Eventually, Night Swan and Cygnus have a child, he named him “Jack Rose” After Night Swans favorite Flower. However, regret and guilt comes to him and he leaves them, as well.

He tries to get either one back during showdown, however Icona rejects him and refuses.

Later on he finds out that he may not even be jacks real father and that his life with Leda could have been a Lie and that Leda could have been sneaking off to have affairs with the traveler. This causes Cygnus to have a mental breakdown and mass kidnap about fourteen people.

#jdlore#just dance#just dance 2024#jd23#Cygnus#cygnus just dance#jd cygnus#night swan just dance#night swan jd#jack rose

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Across a sterile white table in a windowless room, I’m introduced to a woman in her forties. She has a square jaw and blonde hair that has been pulled back from her face with a baby-blue scrunchie. “The girls call me Marmalade,” she says, inviting me to use her prison nickname. Early on a Wednesday morning, Marmalade is here, in a Finnish prison, to demonstrate a new type of prison labor.

The table is bare except for a small plastic bottle of water and an HP laptop. During three-hour shifts, for which she’s paid €1.54 ($1.67) an hour, the laptop is programmed to show Marmalade short chunks of text about real estate and then ask her yes or no questions about what she’s just read. One question asks: “is the previous paragraph referring to a real estate decision, rather than an application?”

“It’s a little boring,” Marmalade shrugs. She’s also not entirely sure of the purpose of this exercise. Maybe she is helping to create a customer service chatbot, she muses.

In fact, she is training a large language model owned by Metroc, a Finnish startup that has created a search engine designed to help construction companies find newly approved building projects. To do that, Metroc needs data labelers to help its models understand clues from news articles and municipality documents about upcoming building projects. The AI has to be able to tell the difference between a hospital project that has already commissioned an architect or a window fitter, for example, and projects that might still be hiring.

Around the world, millions of so-called “clickworkers” train artificial intelligence models, teaching machines the difference between pedestrians and palm trees, or what combination of words describe violence or sexual abuse. Usually these workers are stationed in the global south, where wages are cheap. OpenAI, for example, uses an outsourcing firm that employs clickworkers in Kenya, Uganda, and India. That arrangement works for American companies, operating in the world’s most widely spoken language, English. But there are not a lot of people in the global south who speak Finnish.

That’s why Metroc turned to prison labor. The company gets cheap, Finnish-speaking workers, while the prison system can offer inmates employment that, it says, prepares them for the digital world of work after their release. Using prisoners to train AI creates uneasy parallels with the kind of low-paid and sometimes exploitive labor that has often existed downstream in technology. But in Finland, the project has received widespread support.

“There's this global idea of what data labor is. And then there's what happens in Finland, which is very different if you look at it closely,” says Tuukka Lehtiniemi, a researcher at the University of Helsinki, who has been studying data labor in Finnish prisons.

For four months, Marmalade has lived here, in Hämeenlinna prison. The building is modern, with big windows. Colorful artwork tries to enforce a sense of cheeriness on otherwise empty corridors. If it wasn’t for the heavy gray security doors blocking every entry and exit, these rooms could easily belong to a particularly soulless school or university complex.

Finland might be famous for its open prisons—where inmates can work or study in nearby towns—but this is not one of them. Instead, Hämeenlinna is the country’s highest-security institution housing exclusively female inmates. Marmalade has been sentenced to six years. Under privacy rules set by the prison, WIRED is not able to publish Marmalade’s real name, exact age, or any other information that could be used to identify her. But in a country where prisoners serving life terms can apply to be released after 12 years, six years is a heavy sentence. And like the other 100 inmates who live here, she is not allowed to leave.

When Marmalade first arrived, she would watch the other women get up and go to work each morning: they could volunteer to clean, do laundry, or sew their own clothes. And for a six hour shift, they would receive roughly €6 ($6.50). But Marmalade couldn’t bear to take part. “I would find it very tiring,” she says. Instead she was spending long stretches of time in her cell. When a prison counselor suggested she try “AI work,” the short, three-hour shifts appealed to her, and the money was better than nothing. “Even though it’s not a lot, it’s better than staying in the cell,” she says” She’s only done three shifts so far, but already she feels a sense of achievement.

This is one of three Finnish prisons where inmates can volunteer to earn money through data labor. In each one, there are three laptops set up for inmates to take part in this AI work. There are no targets. Inmates are paid by the hour, not by their work’s speed or quality. In Hämeenlinna, around 20 inmates have tried it out, says Minna Inkinen, a prison work instructor, with cropped red hair, who sits alongside Marmalade as we talk. “Some definitely like it more than others”. When I arrive at the prison on a Wednesday morning, the sewing room is already busy. Inmates are huddled over sewing machines or conferring in pairs over mounds of fabric. But the small room where the AI work takes place is entirely empty until Marmalade arrives. There are only three inmates in total who regularly volunteer for AI shifts, Inkinen says, explaining that the other two are currently in court. “I would prefer to do it in a group,” says Marmalade, adding that she keeps the door open so she can chat with the people sewing next door, in between answering questions.

Those questions have been manually written in an office 100 kilometers south of the prison, in a slick Helsinki coworking space. Here, I meet Metroc’s tall and boyish founder and CEO, Jussi Virnala. He leads me to a stiflingly hot phone booth, past a row of indoor swings, a pool table, and a series of men in suits. It’s an exciting week, he explains, with a grin. The company has just announced a €2 million ($2.1 million) funding round which he plans to use to expand across the Nordics. The investors he spoke with were intrigued by the company’s connection to Finland’s prisons, he says. “Everyone was just interested in and excited about what an innovative way to do it,” says Virnala. “I think it’s been really valuable product-wise.”

It was Virnala’s idea to turn to the prisons for labor. The company needed native Finnish speakers to help improve its large language model’s understanding of the construction-specific language. But in a high-wage economy like Finland, finding those data laborers was difficult. The Finnish welfare system’s generous unemployment benefits leaves little incentive for Finns to sign up to low-wage clickwork platforms like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. “Mechanical Turk didn’t have many Finnish-language workers,” says Virnala. At the same time, he adds, automatic translation tools are still no good at Finnish, a language with only 5 million native speakers.

When Virnala pitched his idea to Pia Puolakka, head of the Smart Prison Project at Finland’s prison and probation agency, she was instantly interested, she says. Before the pandemic, another Finnish tech company called Vainu had been using prisoners for data labor. But Vainu abruptly pulled out after a disagreement between cofounders prompted Tuomas Rasila, who had been in charge of the project, to leave the company.

By the time Virnala approached her with his proposal in 2022, Puolakka was eager to resurrect the AI work. Her job is to try and make the relationship between Finnish prisons and the internet more closely resemble the increasingly digital outside world. So far, she has been installing laptops in individual cells so inmates can browse a restricted list of websites and apply for permission to make video calls. She considers data labor just another part of that mission.

The aim is not to replace traditional prison labor, such as making road signs or gardening. It’s about giving prisoners more variety. Data labeling can only be done in three-hour shifts. “It might be tiring to do this eight hours a day, only this type of work,” she says, adding that it would be nice if inmates did the data labeling alongside other types of prison labor. “This type of work is the future, and if we want to prepare prisoners for life outside prison, a life without crime, these types of skills might be at least as important as the traditional work types that prisons provide,” she says.

But how much data labeling offers inmates skills that are transferable to work after prison is unclear. Tuomas Rasila, the now estranged cofounder of Vainu, who managed the prison project there for a year, admits he has no evidence of this; the project wasn’t running for long enough to collect it, he says. “I think asking people, who might feel outside of society, to train the most high-tech aspect of a modern society is an empowering idea.”

However, others consider this new form of prison labor part of a problematic rush for cheap labor that underpins the AI revolution. “The narrative that we are moving towards a fully automated society that is more convenient and more efficient tends to obscure the fact that there are actual human people powering a lot of these systems,” says Amos Toh, a senior researcher focusing on artificial intelligence at Human Rights Watch.

For Toh, the accelerating search for so-called clickworkers has created a trend where companies are increasingly turning to groups of people who have few other options: refugees, populations in countries gripped by economic crisis—and now prisoners.

“This dynamic is a deeply familiar one,” says Toh. “What we are seeing here is part of a broader phenomenon where the labor behind building tech is being outsourced to workers that toil in potentially exploitative working conditions.”

Toh is also skeptical about whether data labor can help inmates build digital skills. “There are many ways in which people in prison can advance themselves, like getting certificates and taking part in advanced education,” he says. “But I'm skeptical about whether doing data labeling for a company at one euro per hour will lead to meaningful advancement.” Hämeenlinna prison does offer inmates online courses in AI, but Marmalade sits blank-faced as staff try to explain its benefits.

Science

Your weekly roundup of the best stories on health care, the climate crisis, genetic engineering, robotics, space, and more. Delivered on Wednesdays.

By the time I meet Lehtiniemi, the researcher from Helsinki University, I’m feeling torn about the merits of the prison project. Traveling straight from the prison, where women worked for €1.54 an hour, to Metroc’s offices, where the company was celebrating a €2 million funding round, felt jarring. In a café, opposite the grand, domed Helsinki cathedral, Lehtiniemi patiently listens to me describe that feeling.

But Lehtiniemi’s own interviews with inmates have given him a different view—he’s generally positive about the project. On my point about pay disparity, he argues this is not an ordinary workforce in mainstream society. These people are in prison. “Comparing the money I get as a researcher and what the prisoner gets for their prison labor, it doesn't make sense,” he says. “The only negative thing I’ve heard has been that there’s not enough of this work. Only a few people can do it,” he says, referring to the limit of three laptops per prison.

“When we think about data labor, we tend to think about Mechanical Turk, people in the global south or the rural US,” he says. But for him, this is a distinct local version of data labor, which comes with a twist that benefits society. It’s giving prisoners cognitively stimulating work—compared to other prison labor options—while also representing the Finnish language in the AI revolution.