#Crime

Text

Peter Lorre in M - Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder (1931)

#m - eine stadt sucht einen mörder#m#peter lorre#elsie beckmann#1930s movies#1931#fritz lang#crime#thriller#classics

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

#park chaeyoung#pinterest#dark fashion#[text post]#havana ginger#vampires#babymetal#belly expansion#oneus#crime#bd/sm kitten#try guys

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

#historical fashion#babymetal#crime#bd/sm kitten#fall#try guys#wolfstar#dianna agron#arctic monkeys#grimm#hp cast#miniskirt#bodymantap#buy my premium

127 notes

·

View notes

Photo

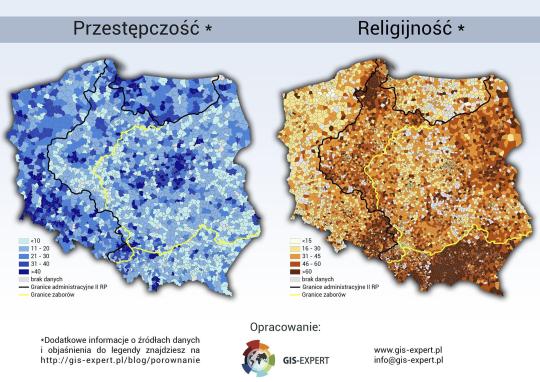

Crime rate (left) and religiosity (right) in Poland

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

He's so girlypop

#will graham hannibal#will graham cosplay#will graham#hannibal tv show#hannibal lecter#hannigram#hannibal#hannibal bts#horror#thriller#crime#glasses#tortoise shell#costume design#costume#person suit

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

HIStory3: Trapped | S03E03

Taiwanese Drama - 2019, 20 episodes

Episodes | Viki | YouTube | Netflix | WeTV | Tencent | Prime | Catalogue

#Drama: HIStory3: Trapped#TWDrama#LGBTQ+#Crime#Romance#Mafia Male Lead#Detective Male Lead#Enemies to Lovers#Adapted from a Novel#HISt♂ry3-圈套#Jake Hsu#Chris Wu#Andy Bian#Kenny Chen#Taiwanese BL#BL GIFS#Taiwanese Drama - 2019#Drama: 2019#Post: Repost

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ian Millhiser at Vox:

The Supreme Court will hear a case later this month that could make life drastically worse for homeless Americans. It also challenges one of the most foundational principles of American criminal law — the rule that someone may not be charged with a crime simply because of who they are.

Six years ago, a federal appeals court held that the Constitution “bars a city from prosecuting people criminally for sleeping outside on public property when those people have no home or other shelter to go to.” Under the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Martin v. Boise, people without permanent shelter could no longer be arrested simply because they are homeless, at least in the nine western states presided over by the Ninth Circuit.

As my colleague Rachel Cohen wrote about a year ago, “much of the fight about how to address homelessness today is, at this point, a fight about Martin.” Dozens of court cases have cited this decision, including federal courts in Virginia, Ohio, Missouri, Florida, Texas, and New York — none of which are in the Ninth Circuit.

Some of the decisions applying Martin have led very prominent Democrats, and institutions led by Democrats, to call upon the Supreme Court to intervene. Both the city of San Francisco and California Gov. Gavin Newsom, for example, filed briefs in that Court complaining about a fairly recent decision that, the city’s brief claims, prevents it from clearing out encampments that “present often-intractable health, safety, and welfare challenges for both the City and the public at large.”

On April 22, the justices will hear oral arguments in City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, one of the many decisions applying Martin — and, at least according to many of its critics, expanding that decision.

Martin arose out of the Supreme Court’s decision in Robinson v. California (1962), which struck down a California law making it a crime to “be addicted to the use of narcotics.” Likening this law to one making “it a criminal offense for a person to be mentally ill, or a leper, or to be afflicted with a venereal disease,” the Court held that the law may not criminalize someone’s “status” as a person with addiction and must instead target some kind of criminal “act.”

Thus, a state may punish “a person for the use of narcotics, for their purchase, sale or possession, or for antisocial or disorderly behavior resulting from their administration.” But, absent any evidence that a suspect actually used illegal drugs within the state of California, the state could not punish someone simply for existing while addicted to a drug.

The Grants Pass case does not involve an explicit ban on existing while homeless, but the Ninth Circuit determined that the city of Grants Pass, Oregon, imposed such tight restrictions on anyone attempting to sleep outdoors that it amounted to an effective ban on being homeless within city limits.

There are very strong arguments that the Ninth Circuit’s Grants Pass decision went too far. As the Biden administration says in its brief to the justices, the Ninth Circuit’s opinion did not adequately distinguish between people facing “involuntary” homelessness and individuals who may have viable housing options. This error likely violates a federal civil procedure rule, which governs when multiple parties with similar legal claims can join together in the same lawsuit.

But the city, somewhat bizarrely, does not raise this error with the Supreme Court. Instead, the city spends the bulk of its brief challenging one of Robinson’s fundamental assumptions: that the Constitution’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishments” limits the government’s ability to “determine what conduct should be a crime.” So the Supreme Court could use this case as a vehicle to overrule Robinson.

That outcome is unlikely, but it would be catastrophic for civil liberties. If the law can criminalize status, rather than only acts, that would mean someone could be arrested for having a disease. A rich community might ban people who do not have a high enough income or net worth from entering it. A state could prohibit anyone with a felony conviction from entering its borders, even if that individual has already served their sentence. It could even potentially target thought crimes.

Imagine, for example, that an individual is suspected of being sexually attracted to children but has never acted on such urges. A state could potentially subject this individual to an intrusive police investigation of their own thoughts, based on the mere suspicion that they are a pedophile.

A more likely outcome, however, is that the Court will drastically roll back Martin or even repudiate it altogether. The Court has long warned that the judiciary is ill suited to solve many problems arising out of poverty. And the current slate of justices is more conservative than any Court since the 1930s.

[...]

The biggest problem with the Ninth Circuit’s decision, briefly explained

The Ninth Circuit determined that people are protected by Robinson only if they are “involuntarily homeless,” a term it defined to describe people who “do not ‘have access to adequate temporary shelter, whether because they have the means to pay for it or because it is realistically available to them for free.’” But, how, exactly, are Grants Pass police supposed to determine whether an individual they find wrapping themselves in a blanket on a park bench is “involuntarily homeless”?

For that matter, what exactly does the word “involuntarily” mean in this context? If a gay teenager runs away from home because his conservative religious parents abuse him and force him to attend conversion therapy sessions, is this teenager’s homelessness voluntary or involuntary? What about a woman who flees her violent husband? Or a person who is unable to keep a job after they become addicted to opioids that were originally prescribed to treat their medical condition?

Suppose that a homeless person could stay at a nearby shelter, but they refuse because another shelter resident violently assaulted them when they stayed there in the past? Or because a laptop that they need to find and keep work was stolen there? What if a mother is allowed to stay at a nearby shelter, but she must abandon her children to do so? What if she must abandon a beloved pet?

The point is that there is no clear line between voluntary and involuntary actions, and each of these questions would have to be litigated to determine whether Robinson applied to an individual’s very specific case. But that’s not what the Ninth Circuit did. Instead, it ruled that Grants Pass cannot enforce its ordinances against “involuntarily homeless” people as a class without doing the difficult work of determining who belongs to this class.

That’s not allowed. While the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure sometimes allow a court to provide relief to a class of individuals, courts may only do so when “there are questions of law or fact common to the class,” and when resolving the claims of a few members of the class would also resolve the entire group’s claims.

The Grants Pass v. Johnson case at SCOTUS could make life worse for unhoused Americans.

#Unhoused People#Homelessness#Grants Pass v. Johnson#SCOTUS#Crime#Martin v. Boise#9th Circuit Court#8th Amendment#Poverty#Grants Pass Oregon

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANNE HATHWAY AS DAPHNE KLUGER

OCEAN’S EIGHT (2018) dir. Gary Ross

#ocean's eight#ocean's 8#2010s#comedy#crime#anne hathaway#oceans8edit#userclara#usersavana#userbru#usergiu#userjean#tuserhan#userashe#userabs#userraffa#usertreena#userhella#*#by mia

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Link

#donald trump#Trump#january 6#Jack Smith#trump indictment#indicted#crime#sorry sorry#I know some people hate this format#sorry!

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

miss Stephanie Soo you might have deleted your many true crime mukbangs but I will never forget about them nor the harm they caused

#not a dream#stephanie soo#rotten mango#true crime#mukbang#food#eating#disgusting#crime#murder tw#death tw#violence tw

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

#one piece#monkey d. luffy#luffy#one piece luffy#straw hat pirates#straw hat luffy#straw hat crew#gear 5 luffy#gear 5th#gear 5 fanart#gear five#gear fifth#crime#funny memes#meme#memes#anime and manga#anime#anime art

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

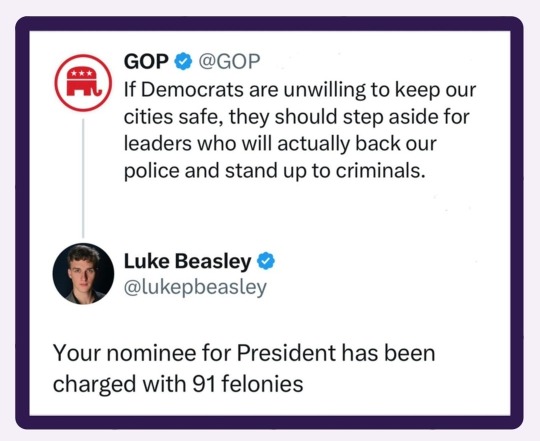

Crime is theatre, a mirage, for delusional Republicans. They can't see it when it happens to Trump, but they can hallucinate the worst prejudices on every person not committing crimes.

Also, GOP wants to cut budgets for FBI, ATF, and DOJ. They literally want to create/legislate safe spaces for conservative criminals.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

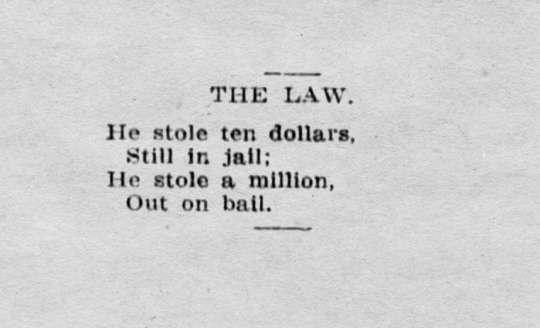

The Age-Herald, Birmingham, Alabama, September 12, 1913

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

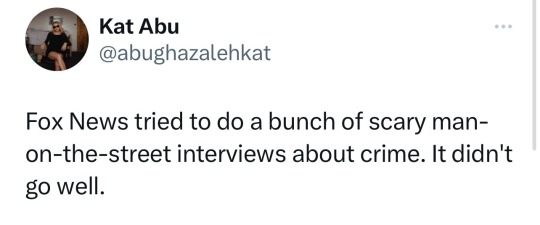

More of this for Fox News interviews, please.

👉🏿 https://colorofchange.org/newsaccuracyratings/

👉🏿 https://blog.oup.com/2018/04/crime-news-media-america/

👉🏿 https://aninjusticemag.com/white-shooters-are-most-often-responsible-for-mass-school-shootings-6e7b647b5cce

5K notes

·

View notes