#Orchid Pavilion Preface

Text

#help im addicted#Lan Ting Xu#Orchid Pavilion Preface#jay chou#兰亭序#周杰伦#can't believe I've only discovered this song now#i admit i don't really like jay chou's singing style#but his composing talent is *chef kiss*#Spotify

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four Treasures of the Study · 文房四宝

蒲一永 Pu Yi Yong · The Brush

Eight Principles of Yong. Traditionally, it was believed that practicing the eight common strokes in regular script, all of which can be found in the character "Yong," could lead to writing all characters well. According to legend, it was created by Wang Xizhi in the Eastern Jin Dynasty, "Yong" is also the first character in his famous work 蘭亭集序 Lantingji Xu (Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion).

The surname "Pu" could potentially be a homage to the famous Chinese writer Pu Songling in the Qing Dynasty. In his most popular work 聊齋誌異 Liaozhai Zhiyi (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio), the focus of the tales are on the emotional entanglements between humans and supernatural beings in the world.

陳楮英 Chen Chu Ying · The Paper

Chu, which refers to the paper mulberry plant, was historically used in ancient China as the raw material for making mulberry paper and Xuan paper. Additionally, "Chu" was used as a term synonymous with paper in ancient times. In EP4, Chuying mentioned that the "chu" in her name means paper.

曹光硯 Cao Guang Yan · The Inkstone

Yan, also known as Yantai, is the name of the inkstone used in calligraphy. The inkstone is used to grind the ink stick into powder, which is then mixed with water on the inkstone to create ink suitable for calligraphy.

執念 The Obsessions · The Ink

The obsessions are one of the ever-changing elements in the show, the elegiac couplets are uniquely written with whole heart and mind for the different obsessions.

#oh no! here comes trouble#oh no here comes trouble#不良執念清除師#不良执念清除师#twdramaedit#asiandramasource#dailyasiandramas#cdramasource#dramasource#twdrama#taiwanese drama#caps#chinese stuff#pu yiyong#Tseng Jing Hua#chen chuying#vivian sung#sung yun hua#Peng Cian You#cao guangyan#i dont even know if this is even interesting to anyone im just splurging thoughts and random meta#this post took 10yrs to make can you believe trying to do the write up was harder than trying to make the gifs#half way through making the gifs i realised i did it in simplified and when i tried to switch to traditional the font didnt work 🥴#i was trying to find a scene where guangyan was in his doctor action but i didnt want to use the cpr scene bc sads#this is he best one i could find where he's wearing a lab coat

322 notes

·

View notes

Photo

【Historical Artifacts Reference】

Chinese Tang Dynasty Female Figurines in “乌蛮髻/Wū mán Hairstyle”

some will put lotus flowers in the middle of the hair

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Tang Dynasty(618-907A.D) Traditional Clothing Hanfu & Hairstyle Based On Tang Dynasty Female Figurines

High Tang Period Women Attire and Hairstyle

————————

📸Recreation Work: @吃货娃娃

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1868003212/MD7GFiYs0

————————

【Shangsi Festival/Double Third Festival/上巳節】

Double Third Festival or Shangsi Festival (traditional Chinese: 上巳節) is a Chinese festival celebrated on the third day of the third month of the Chinese calendar.

It is said that the origin of this festival comes from the Dinner Party at the Qushui River during the Zhou Dynasty (about 1100–221 BC). Others say its origins come from the ceremonial custom of getting rid of evils by bathing in the river. On this day, people would hold a sacrificing ceremony on a riverside to honor their ancestors, and then take a bath in the river with herbs to cleanse their bodies of filth. Following that, young men and women would then go for a spring outing in which many of these scenes were described in Shi Jing (The Book of Songs).

The Shangsi Festival activities have changed over the course of subsequent dynasties. The entertainment feast and praying for descendants along the riverside were added in the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). It was after the Wei and Jin dynasties (220–420 AD) that the festival developed into the Double-Third (Shangsi) Festival that is fixed on the third day of the third lunar month.

In modern times, to observe this festival, people would go for an outing by the water, have picnics, and pluck orchids. It is also a day for invoking cleansing rituals to prevent disease and get rid of bad luck. The day is also traditionally considered to be a possible birthday of the Yellow Emperor.

The ancient traditions of Shangsi are mostly celebrated by several communities spread out among the provinces today, such as the ancient village of Xinye

The great calligrapher Wang Xizhi mentions this festival in his famous work Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Poems, written in regard to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering during the Six Dynasties era.

The Han ethnic people in some places also have special customs on March 3rd. For example, Hunan and other places have the tradition of "March 3rd, boiled eggs with ground (shepherd's) purse", while Anhui and other places have the tradition of eating Baba( a kind of bread, with meat):

#Chinese Hanfu#Tang Dynasty(618-907A.D)#High Tang Period (650-755 AD)#hanfu#hanfu history#Shangsi Festival#Double Third Festival#上巳節#chinese food#hanfu accessories#hanfu artifacts#Tang Dynasty Female Dancer Figurine#chinese traditional clothing#chinese history#historical clothing#historical hairstyles#chinese coustume#China History#吃货娃娃#齊胸衫裙 qixiong shanqun#pibo 披帛#乌蛮髻(Wū mán Hairstyle)

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

arlo’s song rec of the day #1!

兰亭序 (Orchid Pavilion Preface) cover by 西瓜JUN (Xigua Jun) & 王胖子 (Wang Pangzi) -- original by Jay Chou

youtube

lyrics and english translation can be found on this page!

#nov 2022#im gonna tag the months so i can find them later lmao#if u listen i hope u like it!#i love jay chou but i just think the cover is better tee hee...also i really like jun's voice#a.mp3#<- tag for blacklist

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

臨摹 王羲之蘭亭序 唐代馮承素摹本

Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Manuscript e by Wang Xizhi

0 notes

Text

forbidden city

In the Pavilion of the Purification Ceremony, there is a twisting water channel measuring twenty-seven metres long. It was designed in accordance with the verse of "a twisting water channel for floating wine cup and enjoying the drinking festival" in The Preface for the Orchid Pavilion Gathering written by Wang Xizhi of the Jin dynasty(265-420). Modelling himself on Wang Xizhi, the Emperor and his ministers often sat along the channel composing poems and drinking.

0 notes

Text

It's a lovely morning during the Jin Dynasty in Shānyīn, Kuaiji, and you are a Horrible Helpful Goose.

Next on your “To Do” List:

Teach Wáng Xīzhī the secrets of how to turn one's wrist using your graceful goose neck so that he may go on to become regarded as the Sage of Calligraphy, the most acclaimed practitioner of that art in all of China's history.

#untitled goose game#Wáng Xīzhī#Wang Xizhi#Sage of Calligraphy#Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion

52 notes

·

View notes

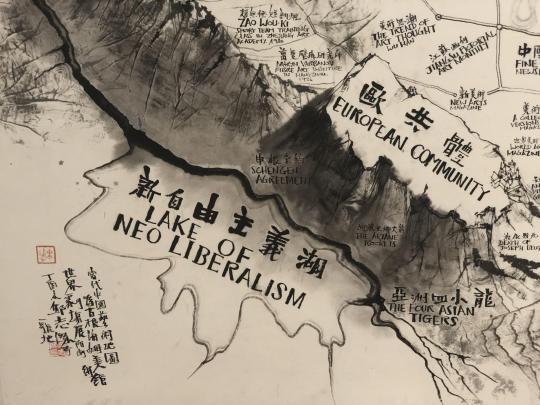

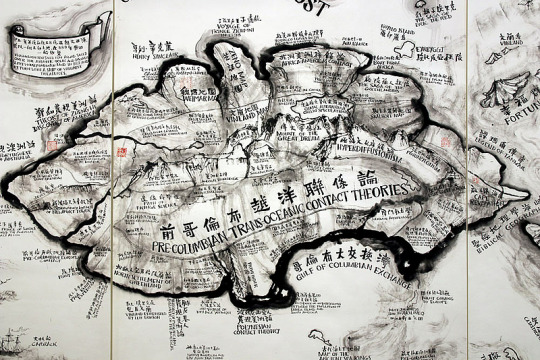

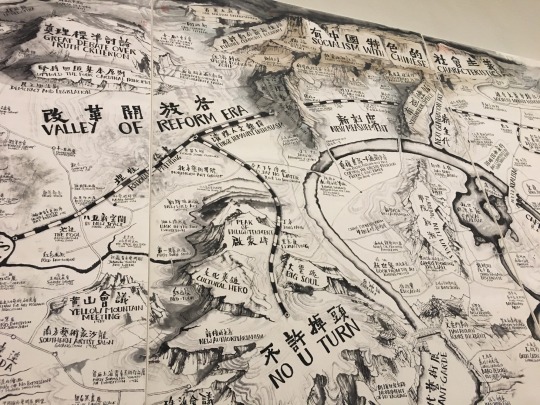

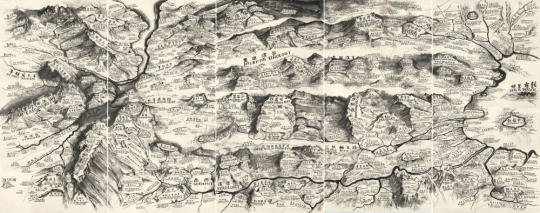

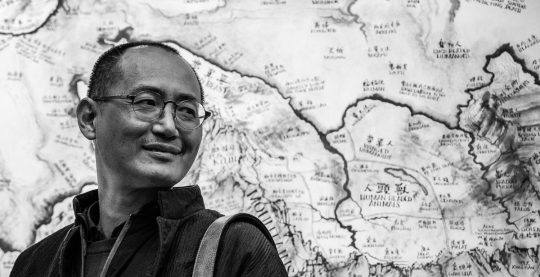

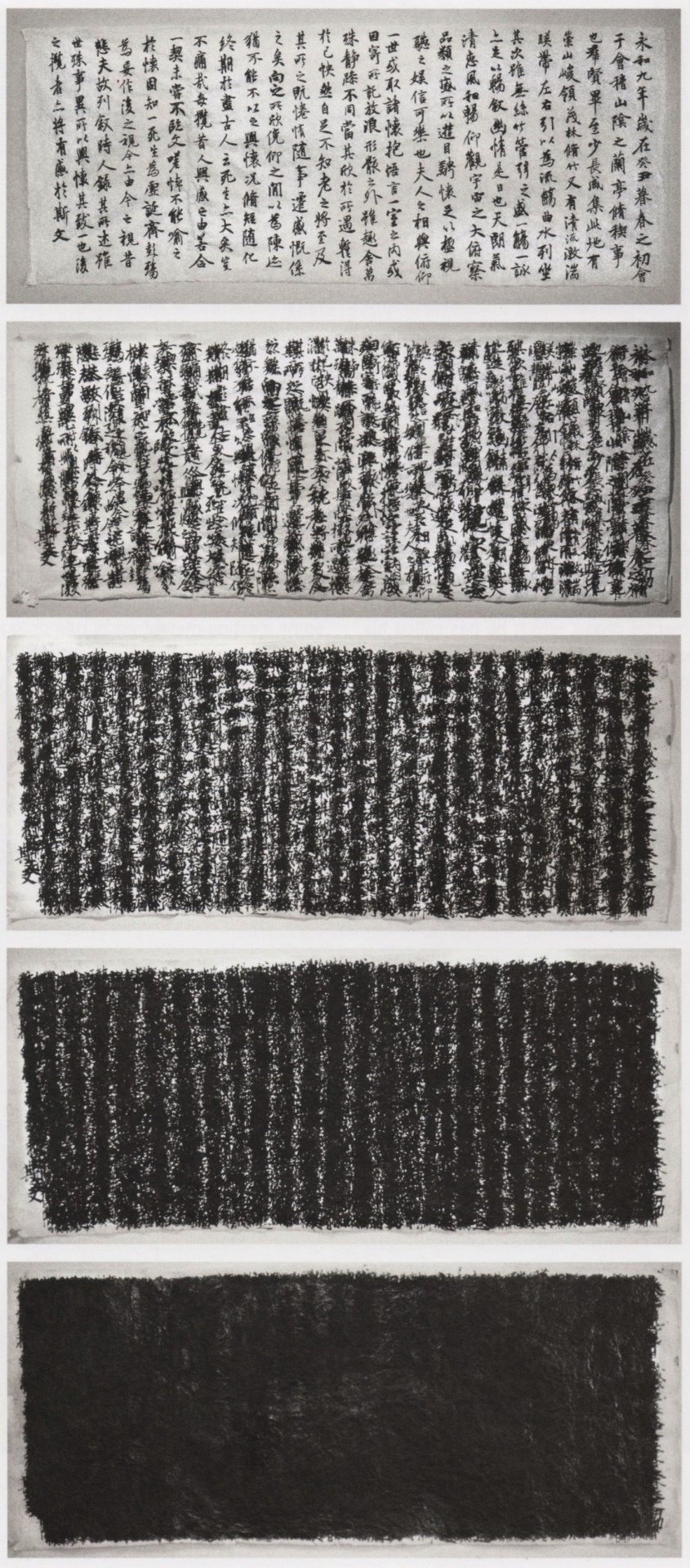

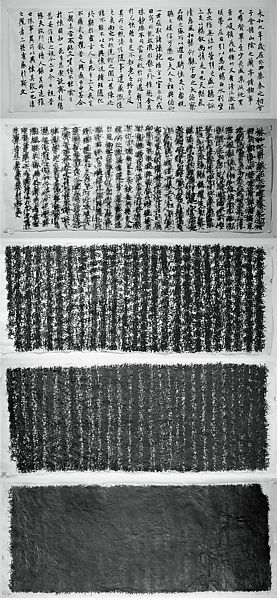

Photo

One of China’s most influential artists is forty-eight-year-old Qiu Zhijie (now 52). A native of southern China’s Fujian province, Qiu studied art in the eastern city of Hangzhou before moving to Beijing in 1994 to pursue a career as a contemporary artist. At the time, contemporary art was illegal in China and artists often lived in villages on the outskirts of town, held underground exhibitions, and were patronized almost exclusively by foreigners.

Qiu quickly made a name for himself as one of China’s leading artists, creating one of the most famous images of that era: a picture of himself from the waist up, shirtless, against a white wall with an enormous red character, 不, or “No,” painting across his face and torso. Another was a video of him copying a classic piece of calligraphy, the fourth-century Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion, one thousand times until it became illegible. More recently, he has embarked on major conceptual art projects, such as an exploration of the suicides that take place at a major bridge that for decades was a symbol of Communist self-reliance, and dozens of enormous idea maps that juxtapose mythology, politics, and social critique.

I got to know Qiu in 1999 when I wrote about the controversy surrounding an influential exhibition called “Post-Sense, Sensibility, Alien Bodies & Delusion.” Held in the basement of an apartment block, it was a backlash against the political pop art of that era, purposefully creating art that couldn’t be sold or collected: a human cadaver encased in a block of ice, for instance, or dead animals nailed to the wall. Disgusted, the authorities closed the show the day it opened—a response reminiscent of the one that greeted the Guggenheim’s current major retrospective of Chinese art, with authorities forcing the museum to remove live animals from several exhibits.

https://www.nybooks.com/.../the-biggest-taboo-an.../

14 notes

·

View notes

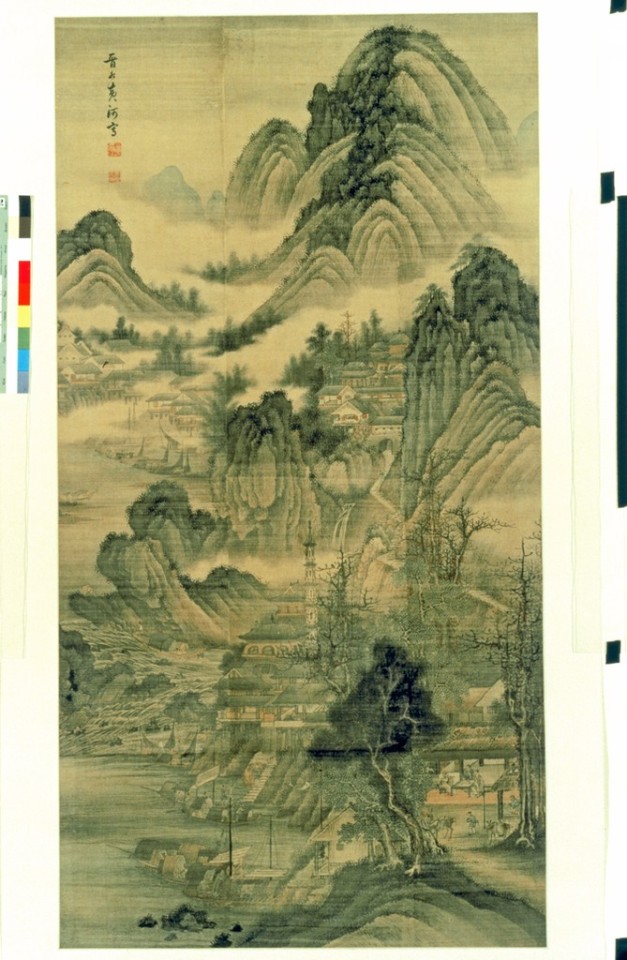

Photo

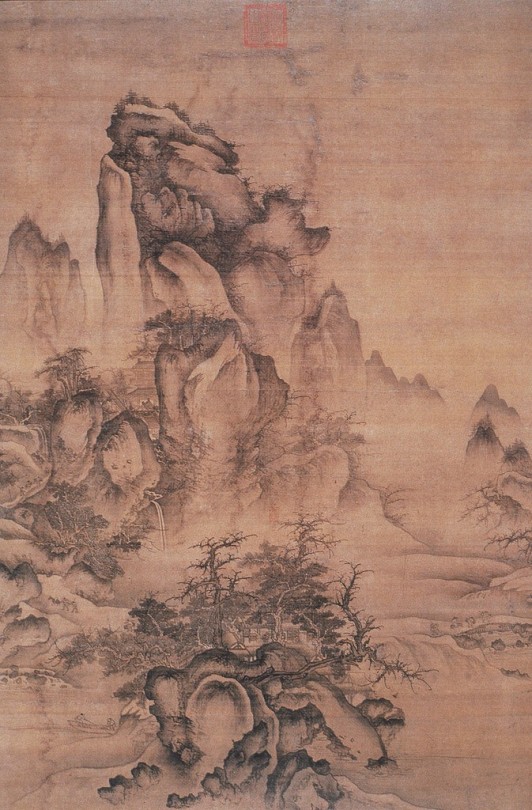

Purification at the Orchid Pavilion, Fan Yi, 1671, Cleveland Museum of Art: Chinese Art

This painting records a historic event in the year AD 353. During the Spring Purification Festival on the third day of the third month in the Chinese calendar, 42 scholars gathered at the Orchid Pavilion near Shaoxing in southeast China to compose poems and engage in a drinking contest. Wine cups were floated down a winding creek as the men sat along its banks; whenever a cup stopped, the one closest to the cup had to empty it and write a poem. At the end of the day, the calligrapher Wang Xizhi assembled 37 poems and wrote the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering in his elegant script style. It became the most famous model for calligraphy in Chinese art history.

Size: Image: 28.4 x 392.8 cm (11 3/16 x 154 5/8 in.); Overall: 29.8 x 763.3 cm (11 3/4 x 300 1/2 in.)

Medium: handscroll, ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1977.47

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

omf well if u want to know how insane i am i paused on this screenshot from joy of life and spent 45 minutes trying to figure out what dynasty that painting is from (if any). my gut instinct was to say tang bc of the blue/green coloration but obvs that doesnt say much bc like every other dynasty after them did the same shit LOLLL and the jol one doesnt seem to have much a traveller/wanderer story vibe so it probably isnt tang and anyway all the tang ones on artstor werent promising except the one on the bottom left which is part of the orchid pavilion preface i think. anyways i was like ok no luck so i searched thru qing bc they had a similar style in terms of mountain shape and plant shape and they did some blue/green stuff but they r way way later (its the one in the middle btw) but i thought this one looks sort of similar if you were to mirror it vertically maybe and like... erase a lot of the filler in the middle... and my final guess was southern song just bc their stuff was waaaay softer lots of empty space and evaporating mists n shit u know anyway thats the bottom right which i felt pretty good about except song def didnt use the green/blue color scheme so what im assuming happened is they painted an amalgamation of all diff types of chinese landscape and slapped it on. which is fair but as an art historian i did sigh a little. anyways thats all

#i need help gary i need my asian art history professor back#maybe i should email her w the screenshot and ask LOLLL#joy of life

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jade Mountain Illustrating the Gathering of Scholars at the Lanting Pavilion .. [3.1 / 3.3]

Light green jade sculpture made in 1790, exhibit at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN.

The Qing dynasty emperor Qianlong (r. 1736–95) commissioned this jade boulder, apparently the largest piece of historic carved jade outside of China. It depicts a literary gathering of scholar-officials at Lanting, the Orchid Pavilion described in “Lanting jixu”, by Wang Xizhi (303–361), a scholar official and recognized as the greatest calligrapher of the Far East. The prose itself is carved on the front.

The theme represented on this jade boulder, the largest piece of jade carving outside of China, refers to an event that occurred on March 3 in the lunar calendar of 353. Wang Xizhi, together with forty-one other renowned scholar-officials, gathered at Lanting, or Orchid, Pavilion in Shaoxing (in presend-day Zhejiang province), celebrating the Spring Purification Festival. The scholars engaged in a drinking contest: wine cups were floated down a small winding creek as the men sat along its banks; whenever a cup stopped, the man closest to the cup was required to drink it and write a poem. In the end, twenty-six of the participants composed thirty-seven poems. Emperor Qianlong’s own poem appears carved on the reverse.

Wang Xizhi was asked to write an introduction to the collection of these poems. Written in semi-cursive script and known as the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion (transcribed on the top of the mountain by the Qianlong Emperor), it is the best known and most copied calligraphic work in art history. While the mountain image alone is enough to convey a close association between the jade sculpture and many painted landscapes, the Qianlong Emperor's seal and poem carved at the top on the other side of the boulder reinforces the idea of the jade mountain as a three-dimensional landscape painting.

#Sony#Walkcam#RX100M2#history#sculpture#museum#Minneapolis Institute of Art#Minneapolis#Minnesota#USA#monochrome

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wang Xizhi and Calligraphy

Just recently I found out that calligraphy is considered the best and most noble art form in China. I was aware that it was an art form that existed in many cultures, but honestly, I was kind of shocked to find that the Chinese hold it in such high regard. In my view calligraphy often just seems more like writing than art, so what makes it the undisputed best art form to the Chinese? As it turns out, there is some history behind writing in China that helps explain the value of calligraphy. Thousands of years ago Chinese characters were inscribed on the bones of turtles. These were perhaps the earliest examples of Chinese writing, and they were often used in divination rituals. Having a connection between those that knew how to write and these early sorts of religious practice has placed a special importance on the drawing and writing of Chinese characters even today. Additionally, it was intriguing to discover that many Chinese characters were originally pictographic. This means that they look similar to the idea that they are trying to represent. Although simplified modern Chinese characters have changed over the years, these pictographs can sometimes still be seen in many Chinese characters. In this way, calligraphy becomes much more like drawing a picture than simply just writing a word. Perhaps this is why it is considered such a noble art form. Oddly enough not only is calligraphy considered to be the best art form in China, but there is also one individual who is considered the best calligrapher. This calligrapher is Wang Xizhi ( 王羲之), he lived during the Jin dynasty and sadly none of his original works still remain today. Only copies of his work keep it alive, but luckily these copies use tracing which make them very accurate depictions for what Wang Xizhi’s original calligraphy would have actually looked like. He became especially famous for what is known as semi-cursive script. This is similar to cursive or writing something quickly in English. Perhaps Wang Xizhi’s most celebrated and popular work is his Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion. This work was an especially beautiful introduction to the work of many popular poets during this dynasty. There is a popularized story that Wang Xizhi learned to move his wrist so perfectly when writing from watching the way geese move their necks. This gave me an understanding of just how delicate and precise calligraphy truly is. Oddly enough Wang Xizhi’s son Wang Xianzhi ( 王獻之), later became a well renowned calligrapher like his father. In the modern-day calligraphy is still an art form used in China, but it is looked as something classical and traditional. There will probably never be another Wang Xizhi, but calligraphy will always be an important and unique piece of the Chinese artistic sphere.

-Luke T

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the exploration and thinking of the "time" in art, Qiu Zhijie has contributed to the completeness of the calligraphy classic "Orchid Pavilion Preface" written on the same rice paper a thousand times. The first time of writing is imitation, and the text is recognizable and literary. As the number of temporary writing increases, the ink marks occupy more blank space on the paper, and the function of writing gradually disappears until the fiftieth time. The face was completely dark. The video recorded the writing process of the first fifty times, showing the process of gradually disappearing from the blank space to the gradual appearance of the black space on the paper. After the fiftieth pass, the writing is done entirely on the black background. Qiu Zhijie wrote in the self-statement of this work: What was first unfolded in time was the knowledge archeology of the principles of Chinese calligraphy, using the method of peeling onions to gradually clean up the insubstantial factors in traditional calligraphy. The first thing to exclude is Literariness is to restore calligraphy to modeling activities, that is, the composition of ink marks, thereby achieving abstract visual purity. The second step is to restore writing to the writing action itself rather than the creation of the shape... Repeated writing on the ink base, That is, it strictly abides by all the classical norms of Chinese calligraphy and strengthens its inherent connotation as a "calligraphy"...so write it 1000 times.

"Orchid Pavilion Preface" is a restoration of Chinese calligraphy as far as its medium is concerned, rather than an innovation in any sense. "He also mentioned that 1000 times is a arbitrarily set goal, in terms of its function, the number can be extended or mixed with water. Choosing "Orchid Pavilion Preface" is not mainly because of the special feelings for the motherland culture, but because of its high popularity. Because the corpses of acquaintances are more attractive than the corpses of strangers, it also makes the gestures performed by the deceased have their presence.

In the invisible writing, the awareness of classical norms is truly clarified. The existence of these rules shows the fundamental function of art: dividing life into purposeful labor and intellectual labor, into rationality and irrationality. The self-rest of the subject in its search for rules is a necessary death and the foothold of reflective imagination. At this time, writing "Orchid Pavilion Preface" 1,000 times becomes an ontological argument for art.

0 notes

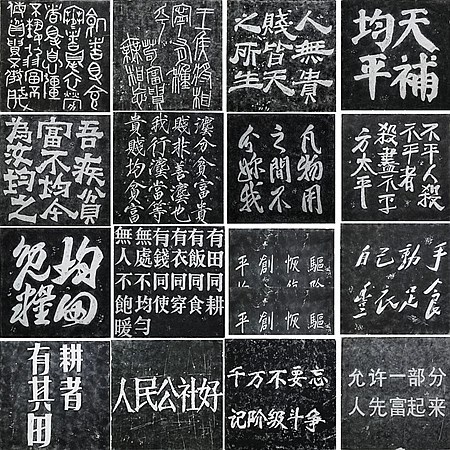

Photo

Writing the “Orchid Pavilion Preface” One Thousand Times, 1990-1995

Qiu Zhijie

0 notes

Photo

RESEARCH:

Qiu Zhijie

Writing the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" One Thousand Times, 1990–97

Five chromogenic prints

Each: 48.9 × 73.7 cm

Chinese artist Zhijie's work Writing the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" One Thousand Times (1990–97) process is as vital to the piece as the completed work. Zhijie continuously re-writes the 353 AD "Orchid Pavillion Preface" text in a contemporary context over a period of seven years (Tewksbury, 2009). Catapulting this ancient text into the 21st century was a catalyst to my use of the ancient Japanese writing 'Kanji' as seen in my first work.

Zhijie has instigated thoughts around old methods like calligraphy as he demonstrates the use of an ancient medium and language in a contemporary context, cementing my use of porcelain and Kanji in my current bodies of work. Despite Zhijie being of Chinese descent and me of Anglo/ Japanese, there is a similarity in the uses of our culture's language. However, Zhijies work is inspired by an ancient text well known within China, whereas my work is a focus on more personal interactions regarding my biracial experience in Australia.

The evident repetition in Zhije's work as he continuously copies the text onto the same piece of paper over seven years is similar to my last work as it visually repeats text, although less intensely and in a shorter period (Hopfener, 2014). Mainly the repeated action of writing the Chinese characters is similar to my continuous recreation of the same few Kanji in, You don't pronounce my name that way. Both works point to identity using parts of our cultures as a catalyst for our works. Zhije has allowed me to consider the use of tradition, traditional knowledge, cultural history, as well as forging the old and new as I continue to explore conceptual art discussing cultural identity.

References:

Tewksbury, N. T. (2009). Sinographics: Becoming Chinese art (Order No. 3385416). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (pp.90-97) (304891411). Retrieved from https://gateway.library.qut.edu.au/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezp01.library.qut.edu.au/docview/304891411?accountid=13380

Hopfener, B. (2014). Qiu zhijie's self-conception as an artist - doing art in a critical historical and transcultural perspective. Journal of Art Historiography, (10), (pp.1-4). Retrieved from https://gateway.library.qut.edu.au/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1545685887?accountid=13380

Image source:

MET. Qiu Zhijie. (1990–97). Writing the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" One Thousand Times [Image]. Retrieved April 2020, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/77606.

0 notes

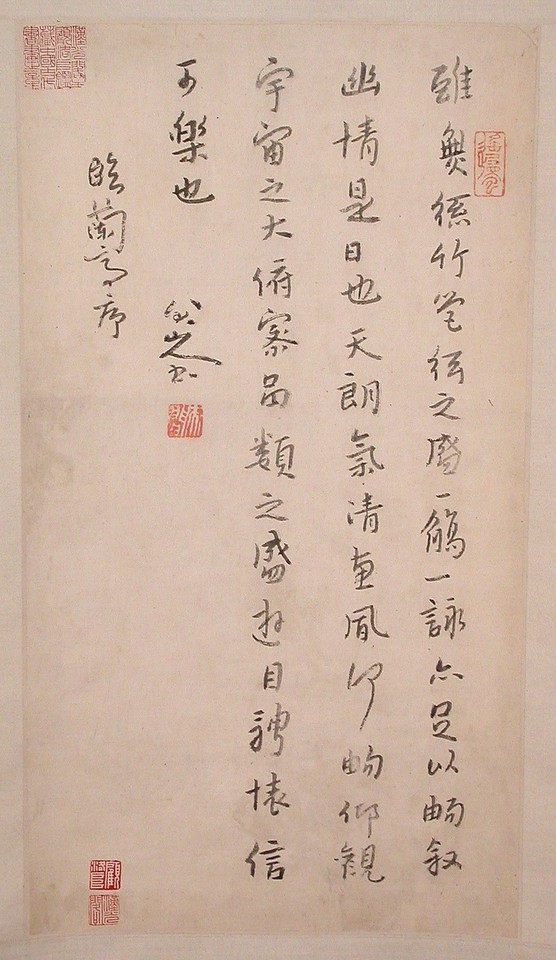

Photo

清 朱耷 (八大山人) 倣王羲之 蘭亭序 軸|After Wang Xizhi's (303?-361?) "Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering" by Bada Shanren via Asian Art

Medium: Hanging scroll; ink on paper

Bequest of John M. Crawford Jr., 1988 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/49144

1 note

·

View note