#Mare Island Navy Yard

Text

USS Oregon (BB-3) in Dry Dock No. 2 at Mare Island Navy Yard, California, between September 20 and 30, 1917.

USN photo courtesy of Darryl L. Baker.

#USS Oregon (BB-3)#USS Oregon#Indiana Class#Predreadnought#Battleship#Warship#Ship#United States Navy#U.S. Navy#US Navy#USN#Navy#Mare Island Navy Yard#California#West Coast#Drydock#dry dock#September#1917#my post

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

USS Monterey (BM-6) in berth at Mare Island Navy Yard in August 1897

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

(6/21/1944) USS Salt Lake City (CA-25)

Off the Mare Island Navy Yard, . Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mare Island Submarine

Photograph showing the conning tower of a World War II submarine as her periscope appears to cleave the sky above. Over 500 ships were built during the 142 years Mare Island Naval Shipyard served the Nation. Those ships ranged from wooden hulled sidewheeler gunboats to a massive battleship, but it was because of the shipyard’s expertise with the complexities of submarine construction that it became known as a submarine yard in later years. All but one of the Mare Island built ships have fallen victim to scrappers torches or they lie on the ocean bottom, victims of the sea or enemy action. The USS Silversides (SS-236) is the lone surviving ship. She is a museum ship in, of all places, Muskegon Michigan. She is a Gato Class fleet-type submarine built at Mare Island just prior to the outbreak of World War II. She was christened by Mrs. James J. Hogan, wife of Dr. Hogan, Vallejo's civilian representative in Washington, and founder of Council No. l, Navy League, in Vallejo. Dr. Hogan was convinced that Mare Island was Vallejo's lifeblood, and he was one of its most effective champions until his death in 1942. Silversides was launched on August 26, 1941, and she was commissioned one week after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Silversides departed on her first war patrol on April 30, 1942, for which she was credited with sinking four ships and damaging one. She went on to establish one of the top submarine combat records in the Pacific. Her record reflected more war patrols than all but 5 submarines, while sinking the third greatest number of ships (23), totaling 145,400 tons. During these patrols, the quality of her construction allowed her to escape undamaged following seventeen counterattacks by the Japanese where a total of 163 depth charges were dropped. Following the war, Silversides was towed up the Mississippi River with her superstructure removed to permit passing under bridges. She then became the submarine training ship at Great Lakes Training Station where she continued to serve until 1969. She has been on display at the USS Silversides Submarine Museum in Muskegon, Michigan since 1987.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#Silversides#Submarine#world war 2#world war ii#world war two

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

USS Wahoo at Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, California, United States, July 14th, 1943.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Balao-class submarine, USS Lionfish was laid down on 15 December 1942, launched on 7 November 1943, and commissioned on 1 November 1944. Her first captain was Lcdr. Edward D. Spruance, son of the famous World War II admiral, Raymond Spruance.

After completing her shakedown cruise off of New England, she headed to the Pacific and commenced her first war patrol in Japanese waters on 1 April 1945. Ten days later, she dodged two torpedoes fired at her by a Japanese submarine and on 1 May destroyed a Japanese schooner with her deck guns. After a rendezvous with the submarine Ray, she transported B-29 survivors to Saipan and then made her way to Midway Island for replenishment.

On 2 June she started her second war patrol, and on 10 July she fired torpedoes at a surfaced Japanese submarine, after which Lionfish’s crew heard explosions and observed smoke through their periscope. She subsequently fired on two more Japanese submarines and ended her second and last war patrol performing lifeguard duty (the rescue of downed fliers) off the coast of Japan. When hostilities ended on 15 August she headed for San Francisco and was decommissioned at Mare Island Navy Yard on 16 January 1946.

Lionfish was recommissioned on 31 January 1951, and headed for the East Coast for training cruises. After participating in NATO exercises and a Mediterranean cruise, she returned to the East Coast and was decommissioned at the Boston Navy Yard on 15 December 1953.

In 1960, the venerable submarine was called to duty again, this time serving as a reserve training submarine at Providence, Rhode Island. In 1971, she was stricken from the Navy Register, and in 1973, she was unveiled for permanent display as a memorial at Battleship Cove, where she has evolved into one of the museum’s most popular exhibits and a revered monument to all submariners.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

US Navy tug USS Dreadnaught (YT 34)

Mare Island Navy Yard, c. 1922

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sailors load SC Seahawks into the amidships hangar of USS Indianapolis during her final overhaul at Mare Island Navy Yard, 12 July 1945. Circles denote the recent alterations to the ship

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Heavy Cruiser USS Baltimore,post refit pictured with Portland Class Heavy Cruiser USS Indianapolis at Mare Island Navy Yard on October 21st 1944.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

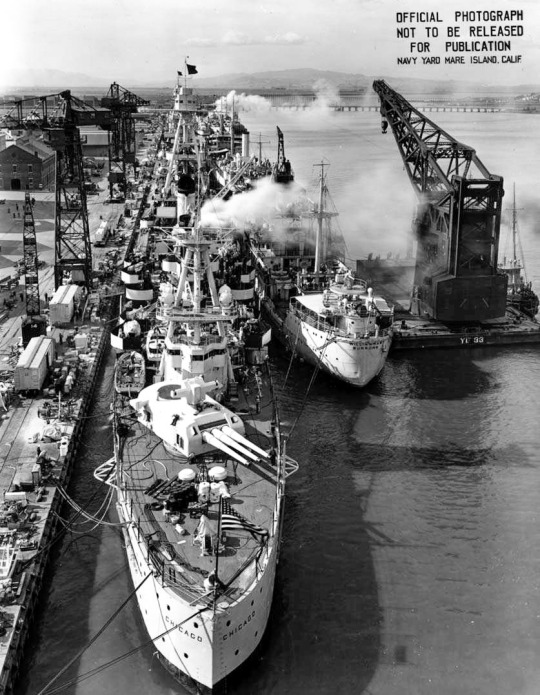

Cruisers docked at Mare Island Navy Yard, California, on September 10, 1940. From top to bottom, left to right: USS Houston (CA-30), USS Ramapo (AO-12), USS Chicago (CA-29) and USS William Ward Burrows (AP-6).

source

#USS Houston (CA-30)#USS Houston#USS Chicago (CA-29)#USS Chicago#Northampton Class#Cruiser#Warship#USS Ramapo (AO-12)#USS Ramapo#Patoka Class#Replenishment Oiler#Oiler#USS William Ward Burrows (AP-6)#USS William Ward Burrows#Troop Transport#Transport Ship#Ship#Mare Island Navy Yard#California#West Coast#United States Navy#U.S. Navy#US Navy#USN#Navy#September#1940#interwar period#my post

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The life, death, and immortality of James Heath, 1864-1894

“No sailor “home from sea” could wish a lovelier resting place, infinity above, the roll of the sea at the hill’s base, the lone cries of the gull patrol mourning forever.” –Fredericka Martin, 1942

The grave of James Heath sits atop Hutchinson Hill on St. Paul Island, in the middle of the Bering Sea, 300 miles west of the Alaskan mainland.

Fredericka Martin, who observed the tombstone in 1941, described it as being made from “polished granite” but, as years of weathering have made it harder to read, here’s the inscription written out:

[James Heath, Gunner’s Mate 1st Class, U.S.S. Concord, Born 1864, Died 1894.]

I took the photo above when I first visited St. Paul Island for birding in 2014. At the time, I didn’t give too much thought to the dead man that lay below me. I was fourteen and the baby Rock Sandpipers running across the tundra captivated my attention more than an old grave but, going back through my photos today I couldn’t help but wonder: Who was James Heath? Where was he from and how did he end up dying in a place like this? So, I took it upon myself to find out as much as I could about the late Gunner’s Mate of the U.S.S. Concord.

James Heath was born on November 17th, 1864 in Rochester, New York to parents who had recently emigrated from Ireland. His father, Richard Heath, was a machinery-worker while his mother, Winifred, worked as a housekeeper. His little brother John was born in 1869 and his father passed away some time after this, leaving his widowed mother to run the household on her own. She would later remarry and have two more children.

In September of 1882, at the age of seventeen, James joined the U.S. Navy and seems to have been occupied with that for the rest of his life. According to his enlistment records, he was 5 feet, three inches tall and had blue eyes and brown hair, as well as a distinctive dark patch on his left thigh.

His early service record is difficult to track but I was able to confirm that, after spending some time on the U.S.S. Vermont in the New York Navy Yard, he was assigned to the U.S.S. Trenton as an able seaman in 1888 and ended up in Panama. (Sidebar: just weeks after he left the Trenton, it was wrecked by a hurricane but, thanks to a heroic maneuver by the crew, only a single life was lost. They essentially formed a human sail to change the trajectory of the ship and keep it afloat until the storm abated which sounds very cool, if terrifying, and I recommend looking more into it if you’re interested.) After this, he spent some time on the U.S.S. Independence in the Mare Island Navy Yard and was then assigned to the U.S.S. Baltimore which took him to East Asia where he would make his final transfer to the U.S.S. Concord in January of 1894. I am reasonably certain that he never returned home from the Pacific in the six years preceding his death.

The U.S.S. Concord normally cruised on the Asiatic Station but, in the summer of 1894, they were diverted to another mission: sealing patrol. The Concord was to protect the Northern Fur Seal colonies of the Pribilof Islands from poachers or any vessels violating international laws that prohibited overhunting. While there, they also conducted scientific observations of the seals. Observe for yourself:

James is only mentioned in the Concord’s ship’s log to indicate his transfer to the ship and, months later, his death, so I can infer that he was good at his job and well-behaved since those who did substandard work or acted out were frequently punished. But it seems that the days leading up to his death were rather peaceful. My personal favorite notation in the log is from August 3rd, 1894: “Birds - saw numbers of birds.” As someone who has been to St. Paul Island twice now, I can definitively say Same.

On August 9th, 1894 though, it is sadly noted that, at the age of 29, James Heath died of pyaemia. I had to look that one up and I’m almost sorry I did because it sounds like a nasty way to go (to spare the gore-y details, it’s a type of sepsis). His body was taken to shore to be buried that same day and a funeral was held by the crew but oddly, without a reason given in the log, he was dug up again the following day and reinterred on Hutchinson Hill, his final resting place. A wooden marker memorialized his grave until the proper granite tombstone was added much later.

Soon after the burial, the Concord would sail back to Asian waters and… that’s pretty much the end of the story. In the words of Herman Melville, “...and the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago.” All of James’ assets were left to his brother and sister-in-law; his mother filed for a widow’s pension from the Navy. And all of them pretty much fall off the historical record after that as far as I’ve been able to find.

But there’s just something about that lonely grave on that tiny island in the middle of the Bering Sea. The way it causes travelers, far from home, just like James, to pause and wonder about what used to be.

“I wonder what sort of life James lived in that little gap between ‘born’ and ‘died’,” pondered John Weigel, of Australia who visited in 2019. “I wonder if anyone knows?”

Well, I’m glad to know as much as possible, at least, and I’m glad that you know now too.

#almost didn't wanna put this under a cut but there we are#i became predictably passionate about this dude and the vague details of his life#but still i wasn't gonna make such a serious post - i'm glad i went this route though#this is better - this is the memorial he deserves#also to be clear afaik i'm the first person to compile this much information about James Heath ever#i figured somebody must have gotten bored and looked into it considering how many tourists Saint Paul Island gets but nope#no complaints though - this was a joy to research#waiting to hear back from my pal Sulli who leads tours on the island to see if he knows why a proper tombstone was installed#that's the final piece of the mystery in my eyes#but as it is - i still managed to find a pretty coherent life story even if it's not as detailed as i'd like#and i'm happy with that#thanks for reading everybody!#James Heath#tagging him ig even though he definitely doesn't have a tag lol

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mare Island Navy Yard is across the Napa River from Vallejo, California.

From the photo album of my great uncle Lawrence Krettler's travels in the US Navy aboard the USS Altair 1923 - 1933 total mileage 85,020

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

USS Ohio (Battleship # 12) In Dry Dock # 2 at the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, circa 1915. USS Newport (Gunboat # 12) is also in the dry dock, astern of Ohio. Ship in the right background is USS Raleigh

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life and Death at the Gate

At dawn on Sunday, 25 June 1950, the North Korean army crossed the 38th parallel supported by massed artillery fire. With the support of the Soviet Union the invasion was based on a false claim by North Korea that South Korean troops had attacked first. The real aim of the invasion was to take by force and subjugate South Korea under rule of the current North Korean leader's grandfather and his sham democracy. Condemned by the Free World, the invasion drew the first ever response by the United Nations, primarily supported by U.S. troops and aid. The war has technically never ended, and it resulted in millions killed and over 100,000 U.S. servicemen wounded or killed in action. In recognition of the coming carnage, a short time after the invasion, the World War II era hospital ship USS Benevolence (AH-13) was towed from a mothball fleet to Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINS) in the San Francisco Bay Area to be taken out of mothballs and recommissioned. The US Navy Hospital Ship Benevolence would never make it to Korea. She tragically sank just minutes outside the Golden Gate while returning from sea trials.

Benevolence departed Mare Island at 0800 on 25 August 1950 for limited sea trials following recommissioning. Eight and a half hours later the fully loaded freighter SS Mary Luckenbac passed under the Golden Gate Bridge in thick fog bound for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Visibility was reported to vary from 300 to 400 yards. Radar had become common place by the 1950’s, but the Mary Luckenbac‘s radar had malfunctioned and was turned off. As the Mary Luckenbac passed under the bridge, she was on a collision course with the Benevolence returning from her sea trials. Aboard the Benevolence the radar was on and operating, but for some reason the crew was unaware of the approaching freighter. Both ships had bow lookouts posted and were operating their fog horns, but their combined closing speeds of 27 knots would doom the Benevolence. At an estimated 1,000 yards bow lookouts on the Benevolence sighted the bow wave of the approaching freighter. Benevolence began blasting the emergency signal on the ship’s horn as both ships attempted evasive action. It was too late, within three minutes the freighter slammed into the hospital ship raking her compartments open along the port side.

Following the collision both ships vanished into the fog. Unaware of the extent of the damage to his ship, Captain Barton E· Bacon on board the Benevolence gave no orders to prepare to abandon ship. However, within 5 minutes his ship’s main deck had sunk to sea level at the bow and she was listing 45 degrees, too far over to launch the lifeboats. The Benevolence had managed to transmit a message requesting emergency assistance just after the collision and then radio contact was lost. Twenty minutes later the Benevolence rolled over and sank in the shipping channel between Pt. Bonita and Seal Rocks. Five Hundred and twenty-five men and women went into the frigid water as the outgoing tide scattered them further out to sea. As word of the disaster spread a small armada of fishing boats, yachts, coast guard and naval vessels began scouring the seas in the thick fog looking for survivors. Survivors would continue to be found and pulled from the sea for nearly two days and as they were landed by rescue ships the Red Cross handed them a carton of cigarettes and the Service’s gave them booze. In the end eleven Navy, ten Military Sea Transportation Service and two MINS tradesmen were lost.

The Benevolence laid just beneath the waves in the south shipping channel as a hazard to navigation for sixteen months as separate courts of inquiry were held by the Navy and Coast Guard on Treasure Island and in San Francisco respectively. While the inquiries were underway MINS was directed to study the possibility of salvage. A no cure no pay request for proposals was sent to Bay Area salvage firms to evaluate the feasibility of salvage. A tanker suffered a minor collision with the Benevolence hulk, before MINS officials determined that salvage was not feasible, and the decision was made to remove the hazard with explosives. When you visit the USS San Francisco memorial near Lands’ End on the 49 Mile Scenic Drive and look out to sea you are overlooking the site of the Benevolence sinking.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#Korean War#Mary Luckenbac#Benevolence#Hospital Ship#Golden Gate#sink#collision#fog#survivor#drown

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

USS Henley at the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, United States, October, 1st 1937.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“USS Case (DD-370) underway off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California on 20 February 1942. Photo 80G13060."

(Source)

112 notes

·

View notes