Text

Rose Bowl

The college football season culminates each year in the granddaddy of bowl games on New Year’s Day. For over one hundred years the pinnacle of college football has been the Rose Bowl Game played in Pasadena, California.

In the game’s early years, except during World War I, the Rose Bowl always pitted a team from the Pacific Coast Conference (PCC), the predecessor of the current Pacific-12 Conference, against an opponent from the Eastern U.S. Then came World War I, and so many college players were drafted for military service that colleges were unable to field teams in 1918 and 1919. To boost morale, President Wilson decided that it would appropriate for teams from military bases to play in the Rose Bowl.

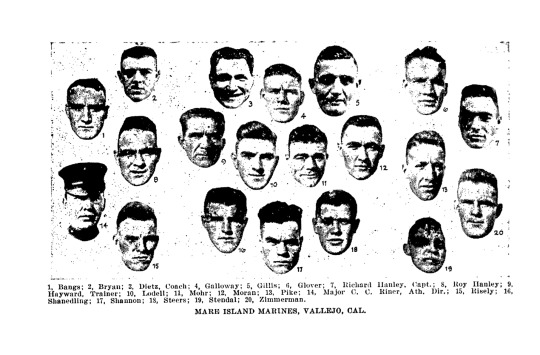

In 1918 the game was played with players from Vallejo, California’s, Mare Island Marines and the Camp Lewis Army Base from American Lake, Washington. Not only did Mare Island field a team in the Rose Bowl, but they also won. The Mare Island Marines also fielded a team in 1919, but in that year their opponent was Navy, and, in that contest, they lost.

The Rose Bowl is nicknamed "The Granddaddy of Them All" because it is the oldest bowl game. Originally titled the "Tournament East–West football game." The first Rose Bowl was played on January 1, 1902, starting the tradition of New Year's Day bowl games. The inaugural game featured a dominating 1901 Michigan team, representing the East, which crushed a previously 3-1-2 team from Stanford University, representing the West, by a score of 49–0 after Stanford quit in the third quarter. Michigan finished the season 11–0 and was crowned the national champion.

In 1918 the Mare Island Marines defeated Army ending the game on top 19 to 7. Within weeks of the 1918 Rose Bowl Game, most of the players from both teams were deployed overseas. John Beckett, left tackle for Mare Island, acknowledged this fact and said that “this would be the last battle that we would fight in the name of sports."

So next time you drive by Morton Field on Mare Island, imagine those warriors from the turn of the century practicing doing battle in the Rose Bowl. A sporting event that they would fight and win before being deployed in one of the bloodiest conflicts in our history.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#Marines#Football#world war i#world war one#world war 1#Rose Bowl#College

0 notes

Text

Lady Justice

In 1905 naval officers from around the country began assembling in a court room in the Mare Island Naval Shipyard administration building (building 47) for the Court Martial of the Captain and the Chief Engineer of a navy gunboat. A Navy Board of Inquiry had already determined the men were guilty of negligence and the Board’s recommendation for Court Martial was approved by the Secretary of the Navy. Their purported negligence during peacetime had resulted in the death of over half of the crew (62 men) of the USS Bennington (Gunboat 4) in the most horrible fashion imaginable and the Nation was up in arms demanding accountability.

The Navy had no need for this scandal and the administration of President Theodore Roosevelt, intent on sending the Great White Fleet around the world in an imperialistic demonstration of US power, wanted the distraction in the rear-view mirror. Despite the desire for expediency by those in charge, an effort to sacrifice the two officers and quickly move on, they found themselves confronted by Lady Justice in a Mare Island courtroom. Lady Justice is a mythological figure for the belief that courts protect the rights of the people with fair and equal administration of the law, without corruption, avarice, prejudice or favor.

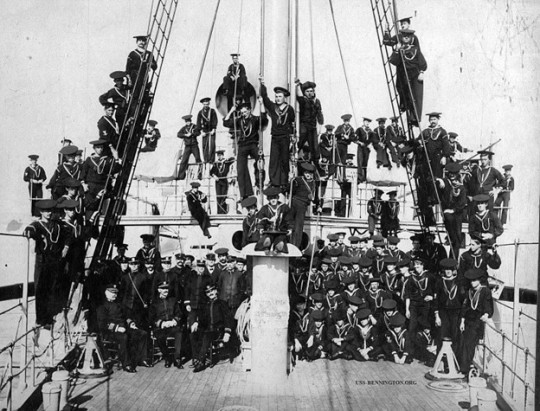

Several months earlier on a typical placid morning on July 21, 1905, the USS Bennington was moored just off H Street in San Diego Bay. Having returned from the Hawaiian Islands her crew had eagerly looked forward to shore leave prior to cruising to South America. Fate intervened as they learned that the aging monitor USS Wyoming (M-10) enroute to San Francisco had lost a propeller and the USS Bennington was to be dispatched to aid and a tow if necessary. Instead of shore leave the entire crew had to spend the previous day doing the back breaking and filthy work of coaling the ship. Now, as the morning went on, the black gang and machinists were busy below firing her four boilers and raising steam to get underway.

She would never make it out of the harbor. As the crew of the USS Bennington went through the routine of raising steam, at 10:38AM things went horribly wrong. Boiler B suddenly exploded crushing bulkheads and ripping other boilers from their mounts. The resulting explosion of scalding steam from all four boilers coursed through nearly every compartment. All the sailors in the boiler rooms were scalded alive and some sailors on deck were observed to be thrown 100 feet in the air. As the boilers and boiler fragments became missiles within the ship, they tore the connections to sea chests apart and sea water rushed into the doomed warship. Heroic crew members and responders beached the doomed vessel preventing her from sinking beneath the waves as her flooded boiler and engine rooms on the starboard side entombed everyone within.

Three days later under orders of the Secretary of the Navy a three-man Court of Inquiry was convened in San Diego. After another three days, the Court of Inquiry submitted its findings to the Secretary of the Navy. The Court recommended the Court Martial of the Chief Engineer, 25-year-old Ensign Charles Wade for not maintaining the safety valves on the boilers and for not demanding written reports (instead of the oral reports he received) demonstrating that they had been overhauled. The Secretary of the Navy concluded from the report that the Captain of the Bennington should also be Court Martialed as he found evidence that the engineering force under his command had potentially fallen into “habits of laxity and inattention to the discharge of their duties.”

On September 15, the hottest part of the year, the Court Martial convened in the courtroom in the Mare Island’s Administration Building. Captain Young was tried first to be followed by Ensign Wade. The prosecution was confident of their case based on the Court of Inquiry. Only one man was alive from the fireroom of Boiler B which had exploded first. He testified that the boiler had been drained of water after the ship arrived from Hawaii and, when ordered to proceed to assist the Wyoming, the boiler was refilled. At the completion of that operation a seaman had been sent up to secure the air valve that vented the boiler. The pressure gauge on the boiler read zero and the fires were started. After over two hours the gauge still read zero while a companion boiler’s pressure had risen to 135 lbs. Then a small leak developed in the furnace of Boiler B and a coal-passer was sent to fetch the boilermaker to assess the problem.

After the coal-passer left the compartment, the ship exploded and he was the only survivor from that boiler room. From his testimony the prosecution’s experts concluded that seaman sent to close the air valve had instead closed the valve leading to the steam gauge. The pressure simply built until the design pressure of the boiler was exceeded and the boiler blew up. The safety valves failed to open and release the pressure because the lack of maintenance by the lax crew left them rusted and inoperable. It was a neat and simple story, but as reported in newspapers nationwide, the defense was relentless and far more technically qualified than the prosecution's witnesses, or the members of the Court of Inquiry.

As noted by the defense, if the air valve had been left open as surmised by the Court of Inquiry, then why wasn’t the boiler venting massive amounts of steam through the air valve? There was no report of such venting. With respect to the relief valves and faulty maintenance, the defense had conducted experiments to deliberately try to cause them to fail to open, including filling them with debris and even concrete. They couldn’t cause them to fail to open. So, what was the defense’s theory of what caused the explosion?

The defense presented that oil that contaminated the boiler feed water was a known problem in the type of boilers on the Bennington. When the crew drained Boiler B a layer of oil scum was deposited on the bottom of the boiler on what is known as the crown sheet that separated the intense fire in the furnace from the boiler water. Such a layer was known to act as insulation between the steel and the water which could cause the plating to overheat. The original plan following the draining of the boilers was to flush them to remove any such oil and debris prior to departure for South America, but the order to proceed immediately to assist Wyoming pre-empted that. The defense examination of the damaged boiler caused them to conclude that, denied direct contact with the boiler water due to the insulation provided by the oil scum, the crown sheet had simply been overheated to the point of distortion. As the crown sheet distorted, rivets designed to carry only shear forces were placed in tension. The rivets were inspected by the defense and were also found to be defective, weaker than called for.

The defense stated that the leak that sent the coal passer out to find the boilermaker was likely the first rivet letting go in the crown sheet with the entire riveted joint ripping apart shortly thereafter. The theory was that the boiler had failed from the overheating of the crown sheet and not from over-pressurizing the boiler as maintained by the prosecution. The pressure relief valve never opened, because boiler pressure never reached the relief point before the crown-sheet failed. The defense never explained why the pressure gauge on Boiler B never registered any pressure, but it could have been an out-of-position valve as maintained by the prosecution, a line blockage or simply a failed gauge. The Court sided with the defense and in January of 1906 the Secretary issued a mildly worded letter of censure that also recognized Young’s “brilliant service in the past.” Chief Engineer, Ensign Wade, was subsequently tried by the same court and quickly acquitted.

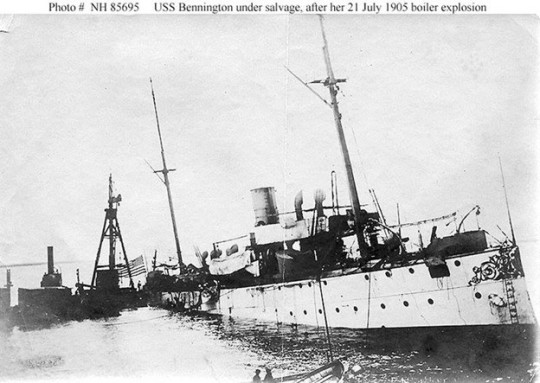

Mare Island dispatched divers and a repair ship to San Diego immediately upon being notified of the disaster. After completing interim repairs, the gunship was towed to Mare Island for further assessment. There she was determined to be beyond repair, and she was converted to a barge. The Bennington disaster did have some long-term beneficial effects within the Navy. It spotlighted the fact that the Chief Engineer Wade had never stood an engine room watch before being assigned to the billet. He knew nothing of machinery, and he did not have the technical knowledge to stop the chain of events that led to the tragedy. Not only had he never been required, nor had he been given the opportunity, to acquire the necessary knowledge. When the Mare Island representatives arrived on scene to salvage the ship it was found that he had none of the ship’s plans were available and when asked where the bottom blows were located so they could be plugged he had no idea what such a thing was. The situation helped to force the tradition bound Navy to elevate the status of the engineer within the increasingly complex and technical fleet.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#Bennington#disaster#justice#court martial#explosion#san diego

0 notes

Text

Murphy’s Law

There is an adage known as Murphy’s Law that states "Anything that can go wrong will go wrong." The wisdom of the adage has been proven since time immemorial, and hard experience demonstrates that its application is universal, and it certainly applies to the operation of naval warships.

Surface warships have operated in close formations since the age of sail. While those close formations have a strategic purpose, there is also a downside. Close formations introduce the prospect of collisions. Before the inventions of radio, radar and electronic navigations systems collisions were often caused by fog, bad weather, human error, incorrect communications or any of a myriad of other things. One tragic example of a collision caused by human error involved a five-year-old destroyer that was pulled out of Mare Island Naval Shipyard’s reserve fleet in September of 1950. She had been built at the end of World War II and was placed in reserve as part of the massive drawdown following that war. When North Korea invaded South Korea the United Nations initial response was to recommend a naval blockade, but this strategy quickly morphed to active “boots on the ground” combat when President Truman was stunned to learn that demobilization had progressed to the point that the assets needed to impose a naval blockade did not exist. Recommissioning Frank E. Evans was part of a massive response to the outbreak of the Korean War.

The USS Frank E. Evans (DD 754) was equipped with all the latest communication, navigation and radar systems allowing her to serve with minimal casualties and with distinction through the Korean and Vietnam Wars until she met her fate at the hands of human error nineteen years later. Following a deployment to the Vietnam War the Frank E. Evans was assigned to the South China Sea as part of a Southeast Asia Treaty Organization exercise. During the exercise she was to operate in formation with a multinational fleet including the light aircraft carrier Her Majesty’s Australian Ship (HMAS) Melbourne (R21) of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and four other escorts: the US destroyers; the USS Everett F. Larson (DD-830); USS James E. Kyes (DD-787) , and the frigates Her Majesty’s New Zealand Ship (HMNZS) Blackpool (F77) and Her Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Cleopatra (F28). In the dark of night on 3 June 1969, the Frank E. Evans was ordered to a new escort station from in front of the MELBOURNE to the plane guard position behind the Melbourne.

Captain John Phillip Stevenson of the Melbourne was extremely sensitive to the dangers inherent in maneuvering ships in formation as five years earlier the Melbourne rammed and sank the RAN destroyer HMAS Voyager (D04), when the latter altered course across her bow. Eighty-two of Voyager’s personnel were killed. Captain Stevenson dined with all the escort captains and emphasized the importance of turning away from Melbourne’s bow when shifting stations from ahead to astern the carrier. Despite that warning, when the Frank E. Evans was ordered to plane guard position at 3 am her bridge personal turned her to port directly into the path of the Melbourne. The Melbourne sounded collision alerts and notified the bridge of the Frank E. Evans, but it was too late. The 22,000-ton Melbourne rammed into the 2,200-ton Frank E. Evans amidships. The force of the collision rolled the Frank E. Evans 90 degrees over and sheared her in two. The bow section then rolled upside down and sank in minutes while the stern section remained afloat. Seventy-four of Frank E. Evans crew were killed. Undoubtedly, many were spared because the stern section remained afloat.

The Court of Inquiry that followed became a bit of a circus as blame for the collision was placed on both ships, but there were charges that the American Admiral chairing the inquiry steered it to that conclusion. Whatever the conclusions of the Court of Inquiry 74 men died on a calm clear night when a state-of-the-art warship equipped with every navigational system available was turned directly into the path of another.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#Murphy's law#Frank E. Evans#sink#collision

1 note

·

View note

Text

Prejudice

The “Panic of 1873” was a global depression caused by American inflation, speculative investments (especially in railroads), demonetization of silver, and economic dislocation in Europe due to the Franco-Prussian War. Our Nation descended into the deepest and longest economic depression in history. The economy of the time was dominated by a few major railroad companies that responded to a resulting excess labor pool by cutting wages thus precipitating massive unrest nationwide. That unrest soon morphed from protests into riots in nearly every major city and the National Guard and military were called out to restore order. Railroad facilities were burned, protesters and rioters shot, and strike breakers threatened and beaten.

Then, in the summer of 1877, racism reared its ugly head as riots broke out in San Francisco. The situation quickly deteriorated, and military resources from Mare Island Naval Shipyard were called on to restore order. For years business had imported Chinese workers as a cheap source of labor to work in the mines, building the railroad, and in sweatshops throughout San Francisco. Those workers were subject to indentured servitude and controlled by Chinese Tongs. As the depression deepened in California protests took on a racist turn. Cheap Chinese labor was tolerated when they were employed in the dangerous jobs of hard rock mining and building the railroad, but by the time of the depression jobs in those industries had dwindled and the Chinese were in direct competition for wages with other California residents and immigrants of European descent. The Democratic and Republican political parties were united against the Chinese with the Democrats demanding legislation to prevent the “immigration of Mongolians” and the Republicans demanding investigation of the “Mongolian problem.” It was in that environment, that riots broke out in San Francisco in July of 1877. As mobs roamed San Francisco, Chinese workers were beaten or killed, and homes and businesses were destroyed and burned.

Responding to the disorder a “Committee for Public Safety” reminiscent of the “Vigilante Committees” of the 1850’s was formed as thousands armed themselves to put down the rioters who they referred to as hoodlums. The chair of that committee remembered the effect that the US warship John Adams had on the city when its commanding officer threatened to turn its guns on the city during another period of insurrection, and he telegraphed the President requesting federal support. Army troops were stationed on Angel Island and Alcatraz and the Secretary of the Navy ordered resources from Mare Island to the City. Included in the Mare Island response was the Monterey, the Corvette Pensacola and the screw sloop of war Lackawanna with a Marine contingent. The overwhelming show of force had the desired effect, and the violence and rioting were soon quelled. Several weeks later the Mare Island ships and forces were recalled and, other than providing a threatening presence, there is no record that they participated in any action.

One can imagine that those marines and sailors did not relish the duty they were assigned. Intervention in domestic civil disturbance is a complex, demanding, and controversial mission. Upholding lawful government when the threat to law and government comes from among our own citizens is a mission no one in the military would want to become involved in. As unappealing as the image of American soldiers and sailors confronting American citizens may be, the military responsibility to assist in securing domestic tranquility has deep constitutional roots, and for over two hundred years our military has often proved the instrument of last resort when such chaos seemed imminent. Fortunately, in this case it appears the military did not participate in active enforcement; however, the idea that the civilian head of a self-appointed committee could request and receive military support from the President seems dubious at best.

As for the racial bias against Chinese, it continued for decades with laws passed to stop Chinese immigration and openly discriminate against them. Boycotts of the Chinese were common as well as boycotts by the Chinese in retaliation. Nearly 30 years later little had changed, when in 1906 the San Francisco School Board voted to segregate Asian children from other students to protect those other students from undue influence “by association with pupils of the Mongolian race.” This open discrimination carried the force of Law until well into the 1940’s.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#predjudice#racism#Chinese#san francisco#discrimination#riot#Exclusion Act

0 notes

Text

Rules are Rules

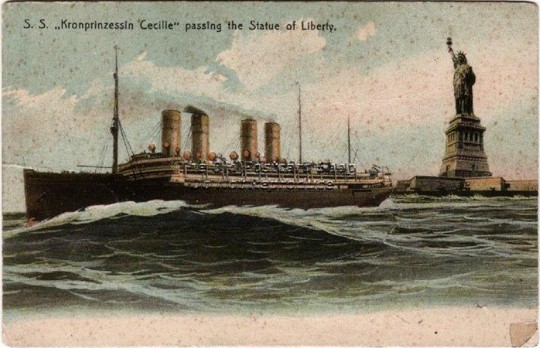

The US Army transport ship USS Mount Vernon (ID-4508) was originally the huge German passenger liner S.S. Kronprinzesin Cecilie, built in Stettin, Germany, in 1906. As a US Army ship she had an eventful history including a humorous event at Mare Island Naval Shipyard.

When World War I broke out in 1914 the S.S. Kronprinzesin Cecilie and 113 Austrian and German merchant vessels sought shelter in US Ports from the English and French fleets who would have hunted them down and sunk them. Those ships sat unused until the US entered the war in 1917 at which time they were all seized in a coordinated action. Aware of the pending seizure, all the ships were sabotaged by their crews on orders from the German High Command to prevent their use against Germany. It did not work, even though the S.S. Kronprinzesin Cecilie’s huge cast cylinders for her steam engines were smashed, US naval personnel pioneered a process to weld repair the castings returning her and others like her to service much quicker than the German’s anticipated. Together with other US flag ships, they carried two million American servicemen to France leading to the defeat of the Germans by Allied Forces.

The Mount Vernon made the first of nine trips across the Atlantic, hauling troops to and from the battlefields in October of 1917. Then one year later Mount Vernon was headed for the US with a load of wounded soldiers. 200 miles off the French port of Brest gun crews sighted a submarine periscope. It was too late to take evasive action as a torpedo slammed into her side and water began rushing in. The captain reversed course and personnel manned lifeboats to abandon ship if necessary as he steamed back towards Brest with damage control parties fighting the flooding. She made it to safety and was quickly repaired and put back in service. Then in 1919 with war over she was sent out to the Pacific.

On 17 October 1919 Mount Vernon was transferred to operation by the Army Transport Service where the ship was assigned to the Army's Pacific fleet based at Fort Mason in San Francisco. She steamed through the Panama Canal and into San Francisco Bay on Monday, November 10, 1919. At 706 ft long and 32,000 tons displacement she was the largest ship ever to transit the canal or sail into San Francisco Bay. Her mission was to sail to Vladivostok, Russia to return US troops and repatriate German prisoners of war and Czechoslovak troops who had been fighting the Russian Bolsheviks. But before she headed to Russia, she went to Mare Island for repairs. The process for ships heading to the shipyard was for the Mare Island Pilot to board the ship out in the Carquinez Straits and guide it to the pier through the narrow channel in the Mare Island Straits. No doubt the pilot was looking forward to the opportunity to guide this massive ship up the waterway. People would talk about it for years, and they did, but probably not for the reasons he supposed.

When the massive ship arrived off the Mare Island Straits her Army Captain did not pause as expected and, instead, he proceeded up the Strait to a position opposite the shipyard. Alarmed by the sudden appearance of the huge ship, Mare Island officials radioed her advising the captain that he was not authorized to proceed up the channel without the Mare Island pilot on board. In response, the Army Captain swung the giant ship around and sailed back down the channel to await the pilot out in the Carquinez Straits. Once the Mare Island pilot was on the bridge of the Mount Vernon, she then proceeded yet again up the straits to the shipyard. Fortunately for the pilot, the trip was as uneventful as the first or he never would have heard the end of it (he probably never did anyway).

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#world war 1#world war i#world war one#bay area#California#northbay#solano#sonoma#napa#wine country#military#tourism

0 notes

Text

Wooden Dry-Docks?

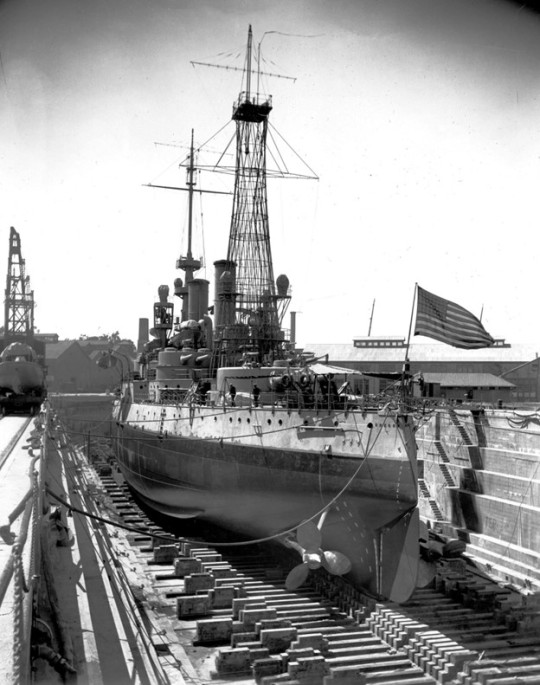

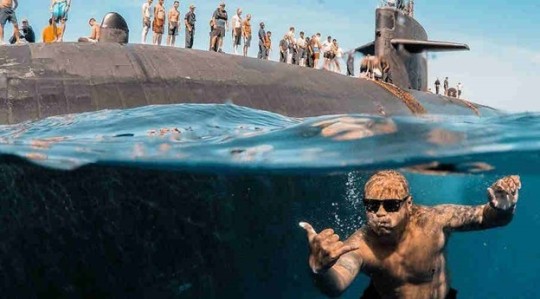

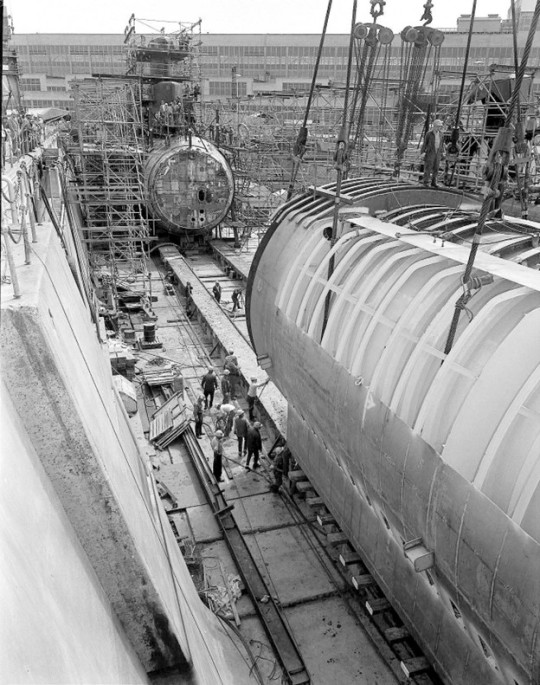

The USS Emory S. Land (AS-39), a submarine tender, has recently docked a couple of times for overhaul in Mare Island’s dry dock 2. She owed her presence in that dry dock to decisions made a century and a quarter ago. Then, like now, the US Navy was limited by the lack of shoreside infrastructure and specifically, dry docks.

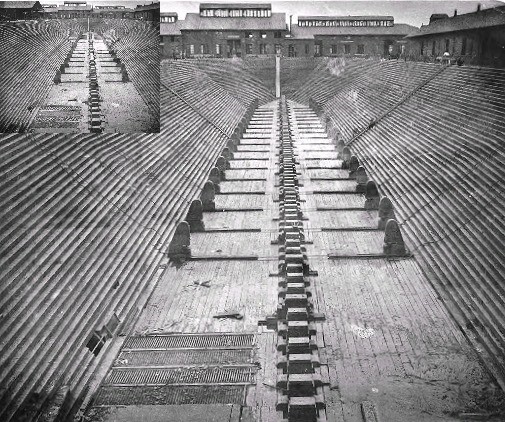

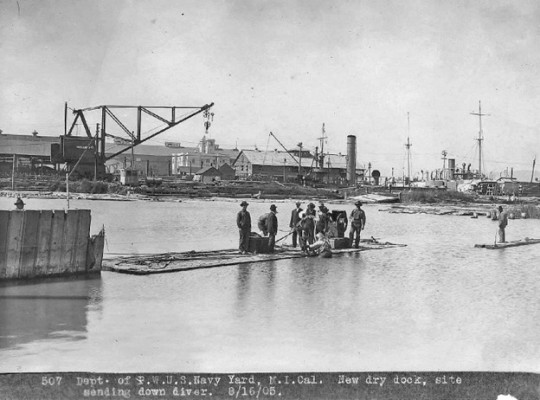

In 1897 Rear Admiral Francis Bunce chaired a board investigating the lack of shore infrastructure. That board recommended a forty percent increase in the number of dry docks at naval shipyards which included a new dry dock 2 at Mare Island Naval Shipyard that was to accommodate the largest naval warship envisioned. To save money, the new Mare Island dry dock was to be constructed of timber rather than stone or concrete. Believe it or not timber dry docks were considered by some to be just as durable as a stone dock (Mare Island’s first floating drydock was constructed of wood and lasted nearly 40 years before it was completely worn out and scrapped). The dock was so long that it had to be angled in from the waterfront to fit without impacting existing facilities. Following debate, the new dry dock was authorized and funded by Congress, but the Navy Bureau of Yard and Docks was not happy with the proposed timber construction. Experience had taught them that timber graving docks deteriorated in 20-25 years and were subject to catastrophic flooding.

As a result, the Secretary of the Navy became engaged to obtain additional funds to allow the proposed timber dock at Mare Island to be changed to concrete. In late 1899 the Board of Trade of San Francisco and the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce adopted resolutions asking the California delegation, in Congress to aid the Secretary of the Navy and the Chief of the Navy Bureau of Yard and Docks in their efforts to have the construction material changed. The effort was successful, and a concrete dry dock was constructed. The new dry dock was the largest dry dock at any naval shipyard at that time. The decision to use concrete was to prove wise as the new dry dock was to serve the Navy through two world wars, the Korean, Vietnam, and Cold Wars. The dry dock continues in use to this day by the private Mare Island Dry Dock LLC. It is hard to say what would have happened if the dry dock had been built of timber as originally proposed, but certainly the dock would not have been available during our Nation’s greatest hour of need during World War II.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#Bay Area#San Francisco#California#shipyard#Solano#Sonoma#Napa#Wine Country#Military#Tourism#Old Navy

0 notes

Text

Unsinkable

the USS Tuna (SS-203) is an example of durability of a submarine built at Mare Island. The Japanese couldn’t sink her, friendly fire couldn’t, and nuclear weapons were not up to the task. In the end only the U.S. Navy could sink her when it was decided to scuttle her. USS Tuna was a United States Navy Tambor-class submarine launched at Mare Island on October 2 in 1940 as part of an arms build-up as the world grew ever more consumed by war. She served throughout the Pacific during World War II and earned seven battle stars. After the war, she was used as a test platform during the Bikini Atoll atomic bomb testing in 1946.

Tuna departed San Diego, California, on 19 May 1941 for Pearl Harbor and shakedown training. In one of those rare moments when adversity is twisted into opportunity the operations in Hawaiian waters revealed that the submarine's torpedo tubes were misaligned. This builder’s flaw took a positive turn when correcting the problem necessitated her returning to Mare Island for repairs. During the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, Tuna lay safely in drydock at Mare Island. Following repairs, she set out for Pearl Harbor an war patrols on 7 January 1942.

Tuna conducted 13 war patrols in the East China Sea, the Japanese home islands, the Aleutian Islands, the waters off the east coast of Vella LaVella; off New Ireland and Buka, and the Bismarck Archipelago, off Lyra Reef, on the northeast side of New Ireland. In mid-1943, as Tuna set out from Brisbane on her eighth patrol, a Royal Australian Air Force patrol bomber attacked her, dropping three bombs close aboard. The resultant damage necessitated 17 days of major repairs at Brisbane, delaying her departure for the eighth patrol. She then set off for the East Caroline Basin on the traffic lanes to Rabaul, and the Java Sea and Flores Sea before returning to Hunters Point Navy Yard in California, where she arrived on 6 April 1944 for a major overhaul. After refitting, she headed for the Palau Islands. Tuna roamed the sea lanes of the Japanese home islands, off Shikoku and Kyūshū. She then supported the invasion and liberation of the Philippines.

Tuna’s final war patrol began on 6 January as she left Saipan to take position off the west coast of Borneo. From 28 January to 30 January 1945, Tuna conducted a special mission, reconnoitering the northeast coast of Borneo. She did not attempt a landing due to enemy activity. From 2 March to 4 March, Tuna accomplished her second special mission of the patrol, landing personnel and 4400 pounds of stores near Labuk Bay.

Following the war Tuna was selected as a target vessel for the upcoming atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Tuna was assigned a place among the target vessels anchored in the atoll. The first atomic bomb was detonated on 1 July 1946, and the second followed 24 days later. Receiving only superficial damage, following the Atomic bomb test Tuna was decommissioned on 11 December 1946, she was retained as a radiological laboratory unit and subjected to numerous radiological and structural studies while remaining at Mare Island. She was then towed from Mare Island for the submarine's "last patrol." On 24 September 1948, Tuna was sunk in 1,160 fathoms (6,960 ft) of water off the West Coast and struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 21 October 1948.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#submarine#world war 2#world war ii#world war two#Tuna#Unsinkable#atomic bomb#Bikini#Scuttle

0 notes

Text

Like a Rolling Stone

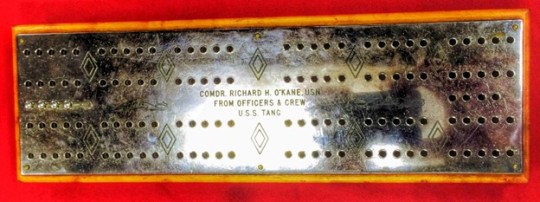

In the 2nd year of US involvement in World War II a submarine departed Midway Island for an audacious war patrol. The USS Wahoo (SS-238) was taking the war into Japanese home waters. The Mare Island built Wahoo was to be the first US submarine to enter the dangerous but target rich environment of the Yellow Sea. Tension within the boat was reported to be high as the submarine proceeded to its patrol area. Executive Officer (XO), Richard “Dick” O’Kane broke out a cribbage game board and challenged the commanding officer (CO), Commander Dudley “Mush” Morton to a game of cribbage. A Navy tradition and legend that lives to this day was about to be born.

Cribbage is a simple two-person card game, and the cribbage board is used to keep score. As CO Morton and XO O’Kane squared off, Morton dealt O’Kane the highest possible cribbage hand, a “perfect 29.” The odds against such a hand were so high that the crew took it as a good omen, they were right. That night, the Wahoo sank two Japanese freighters. Three days later, in another game, Morton dealt a 28-point hand. The following day, they sank two freighters and a third the next day. This fourth war patrol of the Wahoo continued to be highly successful and O’Kane’s cribbage board began to assume legendary status among the crew. Following Wahoo’s fifth patrol, she returned to Mare Island Naval Shipyard for overhaul and O’Kane and his cribbage board left the Wahoo so he could assume command of another Mare Island built submarine, the USS Tang (SS-306). Wahoo reentered the war zone in mid-August 1943 and two months later she was lost.

Meanwhile, Tang with O’Kane, and that cribbage board went on to become the single most successful submarine in US history until sunk by her own torpedo in a surface attack during 1944. O’Kane survived the sinking only to be rescued and interred in a Japanese prisoner of war camp until the end of the war. The cribbage board went down with the ship, but then in 1951 Portsmouth Naval Shipyard was set to launch a new submarine to be named Tang, the USS Tang (SS-563). Mrs. Richard H. O'Kane was selected as the Sponsor; and during the launch events Commander Richard H. O'Kane was presented with a new ceremonial cribbage board by the officers and crew of the new submarine. After Richard O’Kane died in Petaluma, California in 1994, that new cribbage board was presented to the oldest operating fast attack submarine in the Pacific.

The submarine was the Mare Island built USS Kamehameha (SSN-642). USS Kamehameha was the last surviving 41 for Freedom nuclear powered ballistic missile submarine and it had been converted from a missile boat to a special operations boat and designated a fast attack. When the Kamehameha was decommissioned, the cribbage board was then transferred to USS Parche (SSN 683), a former Mare Island based Ocean Engineering Boat. The Parche was decommissioned in 2005 and the cribbage board passed to the USS Los Angeles (SSN-688), again, the then oldest fast attack in the fleet.

To this day the cribbage board has continuously traveled beneath the oceans of the world aboard the oldest fast attack submarines in the fleet. On Sunday, September 8, 2019, the USS Olympia (SSN-717) arrived back at Pearl Harbor with the cribbage board following her final patrol. Like a rolling stone the cribbage board has gathered no moss as the Olympia transferred the board to the USS Chicago (SSN-721) and from there it went to another Los Angeles Class nuclear powered submarine Key West (SSN-722) as the tradition that dates to the Wahoo’s 4th World War II war patrol continues.

The submarines that carry that cribbage board today would have amazed the crew of the Wahoo with respect to every aspect of their design, weapons and technological capability. No doubt Wahoo’s skipper, Cdr. Mush Morton, who has been on eternal patrol with his crew since they were sunk of the coast of Japan in 1943 would have been both fascinated and stunned by the performance of the current holder of the cribbage board.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#submarine#world war 2#world war ii#world war two#wahoo#O'Kane#Morton#cribbage#cribbage board

0 notes

Text

Passing the Baton

The seemingly mundane 1975 vintage photograph of two old submarines on the San Francisco Bay Area’s San Pablo Bay is quite forgettable until one digs a little deeper. The picture captures the symbolic hand off of one of the Nation’s most secret spy operations from the Cold War. It has been widely reported that these two submarines conducted an underwater telephone tapping operation on Soviet undersea cables throughout the 1970’s and well into the 1980’s in an operation code named “Ivy Bells.” That operation was so highly classified that few were aware of its existence, and it has been credited with obtaining information that hastened the end of the Cold War. Presidents anxiously awaited the information gleaned by their missions. Unbeknownst to our government, the existence of the capability, and missions, was sold to the Russians by the American traitor Ronald Pelton, a former National Security Agency intelligence analyst, for $37,000 in 1980. The missions continued, but it was not until late 1985 that our government became aware that the enemy had been onto them for five years.

In the picture on the quiet bay, the nuclear-powered USS Halibut (SSN 587) is to the right and the USS Seawolf (SSN 575) is to the left. Halibut originated Ivy Bells operations in 1970 and she was replaced in 1976 by the SEAWOLF when she was decommissioned. At the time of the photograph, both boats reportedly had been converted at Mare Island Naval Shipyard for their clandestine missions. Each ship had side thrusters installed; sea locks for divers; anchoring winches with fore and aft mushroom anchors; a saturation diving habitat; long- and short-range side-looking sonar; video and photographic equipment; a mainframe computer; induction tapping and recording equipment; port and starboard, fore and aft seabed skids; a towed underwater search vehicle and winch; and other oceanographic equipment.

While much of this equipment was hidden from view, Soviet analysts could not have missed the fact that both ships had been modified to install side thrusters (they are plainly visible), they both operated from Mare Island, and the Seawolf suddenly became 52 feet longer when she emerged from overhaul at Mare Island in 1973. Side thrusters on an attack submarine was a dead giveaway the something was up. The Soviet analysts were probably also aware of how highly decorated these old boats were becoming, but for what? Many of their crews even had little idea of what their missions entailed. We don’t know what the Soviets had deduced regarding the mission of the boats, perhaps the Soviets bought the cover story that the boats were collecting the pieces of Soviet missile tests from the bottom of the Pacific. Whatever they may have believed initially, they got their answer regarding the mission from the traitor Pelton in 1980. Unless you were one of a select few, if you worked at Mare Island and you worked on these boats, you too didn’t know what their mission was. Even if you were briefed into the program and were aware of the configuration and equipment they carried, the lack of a need to know that was strictly limited protect their mission.

To learn of the reported mission of these boats, and those that came after, the public had to wait until two years after Mare Island Naval Shipyard closed. In 1998 the book “Blind Man’s Bluff” was published. Two authors, Sherry Sontag and Christopher Drew, had pieced together the story of submarine espionage and released a book detailing the program and its missions. While the extent of operations may, or may not, have been accurately described in that book, other books and documentaries have subsequently been published supporting much of what was described in Blind Man’s Bluff.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#submarine#ocean engineering#spy#halibut#Parche#Sea Wolf#587#575#683#Ivy Bells#Blind Man's Bluff#clandestine

0 notes

Text

Digging Himself Into a Hole

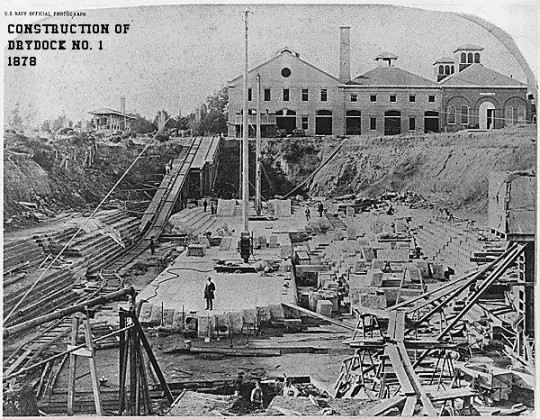

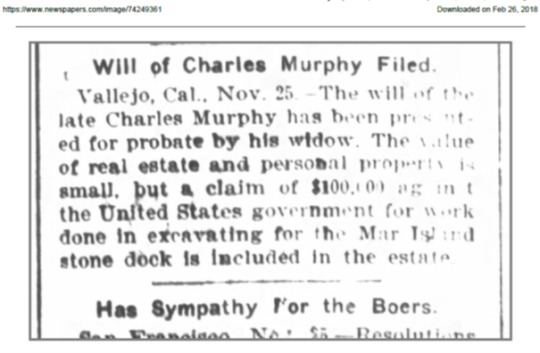

November 25, 1899, the will of Charles Murphy of Vallejo, California, was presented by his widow for probate. The value of the real estate and personal property was insignificant with one huge exception, a claim of $100,000 against the United States Government (nearly $3 million dollars today). That claim was associated with the construction of Mare Island’s first graving dock, often referred to as the “stone dry dock.” Twenty-five years before Charles Murphy had won a big contract with the government and that day proved to be both the best and worst day of his life (at least as he says it).

Under the direction of Civil Engineer Calvin Brown construction of the stone dry dock began in 1872 with the building of a cofferdam (think of a dam) to hold back water in the river and then excavation of the pit that would become the dry dock. For nearly a year, Mare Island employees dug that pit by hand, hauling the spoils out by horse drawn carts, and succeeding in excavating nearly nineteen thousand cubic yards of earth, before the decision was made to contract the work out to a private company.

The private company that won the contract was owned by Charles Murphy. The contract stipulated that Mr. Murphy had 120 days to complete the excavation, but he did not complete the work within the period of performance. Work was allowed to continue for one year, but when the excavation was still incomplete the government terminated his contract in 1874 (he had excavated nearly 80,000 cubic yards when the contract was terminated). Mr. Murphy charged that he could not complete the work in time as the government had failed in its responsibility to maintain the excavation free of water, had prohibited him from using explosives to facilitate the excavation, had failed to provide access to the entire site, and required the spoils to be hauled an unreasonable distance from the site of the excavation greatly increasing costs. He submitted a bill for $149,199 for the added scope and he was paid $59,260. But like every story, there were two sides.

Three years after Charles Murphy’s contract was terminated, both Mr. Murphy and Mr. Brown drew the attention of the San Francisco Chronicle that had investigated Mare Island and the construction of the Dry Dock. The Chronicle poked holes in Murphy’s claims and labeled Civil Engineer Brown as both incompetent and accused him of favoring incompetent contractors such as Murphy who were perpetrating fraud upon the government. In addition to not supporting Murphy’s claims, the article went on to claim that Murphy owed the government penalty fees for failing to comply with contract and it severely criticized Brown’s design of the dry dock. The article undoubtedly caused a stir at the time, but it did not deter Murphy from seeking restitution for what he believed was reasonable compensation.

Not satisfied with the $59,260 payment, Mr. Murphy filed a claim with the government for that extra $100,000 mentioned at the start of this post. That claim was adjudicated by the Commander of Mare Island Naval Shipyard, Adm. John Rogers, and a settlement of $5,685 was authorized. Mr. Murphy took the money with the stipulation that he was not satisfied and that he intended to challenge the settlement, which he did. For the next thirteen years he pursued his claim through the US Court of Claims all the way through the Supreme Court where he lost. He lost because the government treated his acceptance of the $5,685 as a release of all further claims even though that was not the case as testified by the government agents and by the receipt, he provided at the time that clearly stated that he was accepting the funds as partial payment. As a matter of interest, he had that receipt drafted by General Frisbie, the man who is widely accepted as the city Vallejo’s true founder.

Failing in the courts, Mr. Murphy then turned to the US Congress for relief and for eight years petitioned the 48th through the 50th Congress. Twice he succeeded in the US House of Representatives as they found in his favor based on the merits, but in both cases the bill to make him whole was overturned in the US Senate. As we discussed at the beginning of the post, Mr. Murphy went to his grave with his claim still outstanding. As for Calvin Brown’s design of the dry dock, it worked out OK. That dry dock was used up until Mare Island Naval Shipyard’s closure in 1996 and it can be seen to this day outside the Mare Island Museum still holding out the waters of the North Bay despite thousands of dockings and multiple earthquakes. Seems as though the Chronicle may have been a little unfounded in their criticisms of Calvin Brown’s design.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#Charles Murphy#Dry Dock#Supreme Court#Construction Dispute

0 notes

Text

Fire Pump

Horse drawn fire pump on Mare Island in 1914. The pump is seen just in front of the central fire house on the north side of Mare Island’s historic granite dry dock. Imagine the chain of events when a fire call came in. Horses would have to be harnessed and hitched, the fire in the boiler would need to be stoked to raise steam and off the horses and firemen would go. Fire was kept banked below the boiler to shorten the time to raise steam when a call came in. The firehouse was moved to expand the building ways behind soon after this picture was taken.

0 notes

Text

Life and Death at the Gate

At dawn on Sunday, 25 June 1950, the North Korean army crossed the 38th parallel supported by massed artillery fire. With the support of the Soviet Union the invasion was based on a false claim by North Korea that South Korean troops had attacked first. The real aim of the invasion was to take by force and subjugate South Korea under rule of the current North Korean leader's grandfather and his sham democracy. Condemned by the Free World, the invasion drew the first ever response by the United Nations, primarily supported by U.S. troops and aid. The war has technically never ended, and it resulted in millions killed and over 100,000 U.S. servicemen wounded or killed in action. In recognition of the coming carnage, a short time after the invasion, the World War II era hospital ship USS Benevolence (AH-13) was towed from a mothball fleet to Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINS) in the San Francisco Bay Area to be taken out of mothballs and recommissioned. The US Navy Hospital Ship Benevolence would never make it to Korea. She tragically sank just minutes outside the Golden Gate while returning from sea trials.

Benevolence departed Mare Island at 0800 on 25 August 1950 for limited sea trials following recommissioning. Eight and a half hours later the fully loaded freighter SS Mary Luckenbac passed under the Golden Gate Bridge in thick fog bound for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Visibility was reported to vary from 300 to 400 yards. Radar had become common place by the 1950’s, but the Mary Luckenbac‘s radar had malfunctioned and was turned off. As the Mary Luckenbac passed under the bridge, she was on a collision course with the Benevolence returning from her sea trials. Aboard the Benevolence the radar was on and operating, but for some reason the crew was unaware of the approaching freighter. Both ships had bow lookouts posted and were operating their fog horns, but their combined closing speeds of 27 knots would doom the Benevolence. At an estimated 1,000 yards bow lookouts on the Benevolence sighted the bow wave of the approaching freighter. Benevolence began blasting the emergency signal on the ship’s horn as both ships attempted evasive action. It was too late, within three minutes the freighter slammed into the hospital ship raking her compartments open along the port side.

Following the collision both ships vanished into the fog. Unaware of the extent of the damage to his ship, Captain Barton E· Bacon on board the Benevolence gave no orders to prepare to abandon ship. However, within 5 minutes his ship’s main deck had sunk to sea level at the bow and she was listing 45 degrees, too far over to launch the lifeboats. The Benevolence had managed to transmit a message requesting emergency assistance just after the collision and then radio contact was lost. Twenty minutes later the Benevolence rolled over and sank in the shipping channel between Pt. Bonita and Seal Rocks. Five Hundred and twenty-five men and women went into the frigid water as the outgoing tide scattered them further out to sea. As word of the disaster spread a small armada of fishing boats, yachts, coast guard and naval vessels began scouring the seas in the thick fog looking for survivors. Survivors would continue to be found and pulled from the sea for nearly two days and as they were landed by rescue ships the Red Cross handed them a carton of cigarettes and the Service’s gave them booze. In the end eleven Navy, ten Military Sea Transportation Service and two MINS tradesmen were lost.

The Benevolence laid just beneath the waves in the south shipping channel as a hazard to navigation for sixteen months as separate courts of inquiry were held by the Navy and Coast Guard on Treasure Island and in San Francisco respectively. While the inquiries were underway MINS was directed to study the possibility of salvage. A no cure no pay request for proposals was sent to Bay Area salvage firms to evaluate the feasibility of salvage. A tanker suffered a minor collision with the Benevolence hulk, before MINS officials determined that salvage was not feasible, and the decision was made to remove the hazard with explosives. When you visit the USS San Francisco memorial near Lands’ End on the 49 Mile Scenic Drive and look out to sea you are overlooking the site of the Benevolence sinking.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#Korean War#Mary Luckenbac#Benevolence#Hospital Ship#Golden Gate#sink#collision#fog#survivor#drown

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abandoned

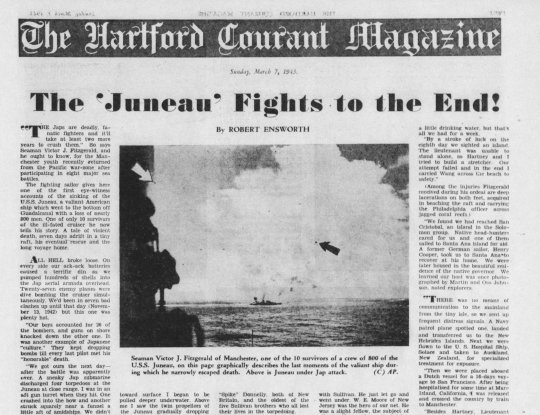

On January 31, 1943, Navy Lieutenant (LT) Charles Wang checked into the hospital at Mare Island Naval Shipyard. His journey to the hospital had been epic as he joined the flood of World War II casualties to be treated at the hospital since the Pearl Harbor casualties arrived on Christmas Day two years before. Lt. Wang’s stay in hospitals stretched out to two years and 30 operations as doctors struggled to repair the damage that a plummeting radar antenna and 6 days of exposure had done to his mangled leg. By all rights, Lieutenant Wang should have been dead, but luck and two sailors had collaborated to save his life.

In the pitch black of night on Friday the 13th of November 1942, Lt. Wang with two other officers, were in charge of Gun Control 2 and had survived unscathed an epic naval battle in Iron Bottom Sound off Guadalcanal. US forces had captured a Japanese airfield on the island of Guadalcanal and in a desperate gamble Japanese Admiral Yamato was throwing everything he had at the US troops to dislodge them. The Americans had broken the Japanese codes and knew that the Japanese were coming. Forty-eight ships, including battleships, heavy cruisers, light cruisers and destroyers were coming through a narrow feature known as the slot intent on pummeling the US troops on Guadalcanal and destroying any warships they might encounter.

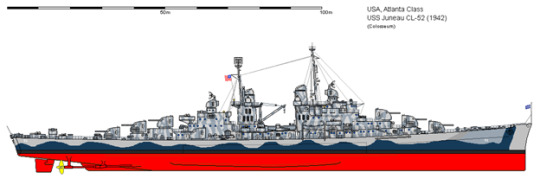

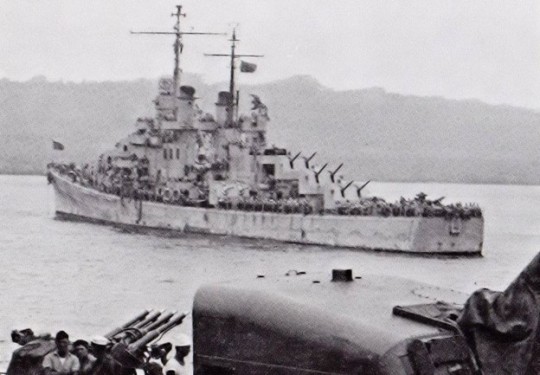

Steaming towards the Japanese fleet was a much smaller US fleet that Admiral Bull Halsey had hastily assembled to counter the Japanese move. The US fleet was outgunned and consisted of only two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and eight destroyers. As the two fleets approached each other the Japanese searchlights suddenly lit up at about two in the morning. All hell broke loose as both sides opened on the other. By morning the two fleets were limping apart. While the Japanese had suffered heavy losses they had scored a tactical victory. Only six ships of the American fleet had survived and except for one destroyer all the remaining ships were heavily damaged. Lt. Wang’s light cruiser the USS Juneau (CL-52) was struggling back to the US base at Espiritu Santo 600 miles away. Lt. Wang survived the battle with no injuries, but the same was not true for his ship and shipmates both of which had been decimated.

The Juneau was built to provide anti-aircraft fire to protect carriers and was never expected to slug it out in a surface engagement. Juneau was riddled with gunfire and a Japanese torpedo had struck her forward boiler room killing everyone in it. Her mess hall had been converted to a sick bay during the battle and suffered a direct hit that reduced it to twisted metal and body parts. Juneau was down at the bow as she limped along on one engine while being steered from a jury-rigged apparatus at the rudder post. As Lt. Wang gazed across the water to the heavy cruiser USS San Francisco (CA-38) he was looking at a similar mess. Her topsides had been struck numerous times leaving a jangle of twisted metal. Her crew had suffered hundreds of casualties, and her bridge was gone because of nearly the entire Japanese fleet focusing on her. Lt. Wang was not the only person looking at the San Francisco.

Staring through his periscope Commander Yokota of the Japanese submarine I-26 fired two torpedoes at the San Francisco. Those torpedoes missed their intended target streaking across her bow. One of the torpedoes found a different victim. Unseen until seconds before impact, that torpedo slammed into Juneau’s magazine. In a massive explosion the huge ship was blown in two and ceased to exist. As the hull sections slipped beneath the waves the ship's radar antenna came hurtling down and broke Lt. Wang’s right leg before he was dragged underwater. Lt. Wang survived the suction of the sinking and ended up on an improvised raft with about 140 survivors most of whom were also badly wounded.

As the men struggled to survive, they were stunned to see the entire fleet sail away. The fleet commander had reasoned that no one could have survived the massive explosion, and it was too dangerous to stay in the area with a Japanese submarine lurking. The men’s injuries, sharks, exposure and lack of fresh water now began whittling away at the survivors. Lt. Wang was in such bad shape that two men determined to set off with him in a raft to a nearby island to seek help. They reached the island 6 days after the sinking, dehydrated, sunburned and starving. Found by natives they were eventually rescued, and Lt. Wang was brought to Mare Island for treatment.

Lt. Wang and his companions were shocked to learn that of original 140 survivors, only 10 men were still alive. Included in the dead were the now famous five Sullivan brothers who had fought hard to serve together on the same ship despite Navy policy against such a practice. Lt. Wang’s war was over as his stay in hospitals stretched out for two years and 30 operations as doctors struggled to repair the damage that the plummeting radar antenna and 6 days of exposure had done to his mangled leg. He returned home to Philadelphia, married, and earned his medical degree, perhaps influenced by his experiences at the Mare Island hospital.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#world war 2#world war ii#world war two#Sullivans#Sullivan brothers#Juneau#San Francisco#Wang#hospital#treatment#medicine#shark#survivor#cruiser#torpedoed#Guadalcanal#sunk#submarine

0 notes

Text

Spirit Ship

The “Spirit Ship,” a sculpture executed by San Francisco artist William Wareham and dedicated in honor of former workers and ships constructed at Mare Island Naval Shipyard. This Art Tribute to the island and its workforce was selected in competition held among area artists when the shipyard was closing in 1996. The sculpture sits atop the high bluffs on the south end of the island pointing out to the Golden Gate and the open ocean. Each of the tags you see hanging from the structure represent some of the ships built at Mare Island.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poisoned

December 5, 1908, was a momentous occasion on the west coast and for naval shipyards. The largest steel ship to have ever been constructed on the Pacific Coast sat perched on the building ways of Mare Island Naval Shipyard. Mare Island’s performance in constructing the 464-foot-long, 9,000-ton collier, USS Prometheus (AR-3) was proving to influential in the future of the shipyard; however, events following the launch place quite a damper on the euphoria of the day.

Mare Island was building Prometheus in competition with the premier navy yard in the nation, the New York Naval Shipyard. This was a competition Mare Island Naval Shipyard could not possibly have been expected to win. After all, the New York Naval Shipyard was an experienced builder of steel battleships, and Mare Island had never built a large steel ship. In addition, Mare Island’s labor costs were 25% higher than in New York, the costs and schedule impacts of shipping steel and equipment from the east coast had to be absorbed, and Mare Island was deficient in the shop facilities needed for such a project, whereas the New York yard had all the necessary facilities to maximize efficiency.

Thousands of people from around the Bay Area took ferries to the island to witness the christening and launch which is a significant and one of the most dramatic milestones in the construction of a ship. As the Governor and dignitaries from all parts of central California looked on, Miss Dolly Evans, the daughter of the naval officer who oversaw the construction, christened the ship just before she slipped into the Mare Island channel in a flawless launching ceremony. Following the launch, the lucky crowd was treated to a sumptuous luncheon and speeches by dignitaries. The luncheon was prepared by a noted San Francisco caterer and featured shrimp salad, chicken, beef tongue, ham and turkey sandwiches which were enthusiastically consumed by the crowd. Leftovers were donated to the Good Templar orphanage in Vallejo to feed the over 100 children housed there.

By the next morning, Miss Evans, the Governor, the children at the orphanage, and many others found themselves in great distress. All available physicians were soon called into service at the Mare Island hospital and in surrounding areas as more and more became violently ill. Most of those that had consumed food at the luncheon were suffering from severe bouts of nausea with no signs of immediate recovery. Ultimately, two of the nearly 1,000 people sickened by the food would die. The poisoned food was first assumed to be meat improperly stored by the caterer: however, the incident was investigated by the state Health Board and the San Francisco coroner’s office as well as local officials.

Ultimately a jury was assembled by the San Francisco coroner at the insistence of the Governor and nearly 70 witnesses were subpoenaed to testify. Those testifying included the caterer, the suppliers of the food and many technical and regulatory officials. Aided by an investigation conducted by Dr. Hogan of Vallejo and physicians at the Mare Island hospital, the cause of the poisoning was identified as bacteria not associated with the handling of the meat. The bacteria, which was known to cause typhoid fever and food poisoning (and can be used as a bioweapon), was determined to have resulted from meat supplied to the caterer from an infected cow that had been slaughtered. The unfortunate conclusion of the investigation was that the incident essentially could not have been prevented.

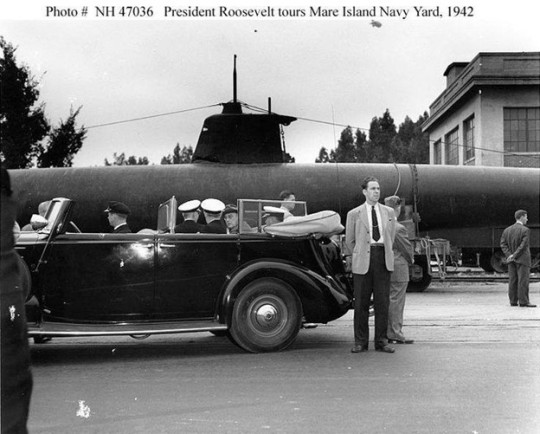

Despite the unfortunate events surrounding the launch of Prometheus, it foreshadowed the beginning of a building boom at Mare Island that continued unabated for years. Despite the constraints affecting cost and schedule, Mare Island delivered the Prometheus at a lower cost than the New York Naval Shipyard delivered her ship, it proved in transforming Mare Island’s image from not only a highly efficient shipyard, but also that of a major building yard. Mare Island’s performance on the Prometheus and the exigencies of World War I led to the ever-increasing workload and investment in infrastructure that led President Franklin Roosevelt to refer to Mare Island as the Nation's #1 public yard when he visited during World War II.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#Prometheus#Poisoned#Poisoning#orphanage#disaster#ship#launch

1 note

·

View note

Text

Accident?

The Russian Cruiser Lena rushes along with a bone in her teeth. In 1904 during the Russo-Japanese War she was impounded by President Roosevelt for failure to comply with neutrality laws. The ship was held at Mare Island Naval Shipyard under constant guard and her crew was paroled pending the end of the war. There was a bit of high drama when Captain Ginter of the Lena announced his intent to curtail a string of 28 desertions by invoking strict Russian military discipline by hanging four deserters. Mare Island’s Shipyard Commander intervened, and the men weren’t hung; however, Ivan Peskov, one of the deserters, mysteriously died of a broken neck a couple of days later. It was variously reported that he had tripped and fell 42 feet down a hatch, that he was being beaten by the LENA’s officers and was knocked down the hatch and that he was hung. The Marines guarding the LENA reported that Peskov was beaten and knocked down the hatch. Whatever the cause of his death, he was buried with full military honors in the Mare Island cemetery.

1 note

·

View note

Text

On the Brink of War!

Early on the morning of 7 December 1941 a Mare Island built ship was just off the mouth of the entrance to Pearl Harbor. While the world was at war, the United States was at peace and the crew of the USS Ward (DD 139) undoubtedly anticipated another quiet sunrise in tropical paradise, but that was not to be. The morning proved surreal as crew members were suddenly engaged in a life and death struggle that presaged the massive aerial assault that was about to unfold. That crew drew first blood against the surprise Japanese onslaught on Pearl Harbor. Unlike the rest of Pearl Harbor’s defense forces, the Captain and crew of this warship were not caught sleeping.

The Ward, under the command of LCDR William W. Outerbridge, was conducting a precautionary patrol off the entrance to Pearl Harbor. This was his first command and his first day in command. Then at 03:57, he was informed by visual signals from the coastal minesweeper USS Condor of a submarine periscope sighting within the "Defensive Sea Area." Submarines were required to travel surfaced in that area, but this one was mostly submerged. Ward began searching for the contact and several hours later Ward's lookout spotted the conning tower of a midget submarine. By then the destroyer had increased its speed to 20 knots and range was down to 100 yards. The Ward opened fire with a 4” round. The Ward was now steaming at more than 22 knots and, as she closed to 50 yards, the gunners fired a second 4-inch shell almost straight down at the sub’s conning tower. The shell struck the base of the midget submarine's conning tower blowing a 4” hole through its port side. This explosive shell is thought to have instantly killed both crewmembers. Ward continued over the submarine’s bow, which bounced around and floundered for a few seconds then sank out of sight. Capt. Outerbridge swung his ship hard around and ordered four depth charges to be dropped on the spot where the sub was last seen. Six minutes after opening fire on the sub, at 06:51, Captain Outerbridge signaled 14th Naval District Headquarters:

“WE HAVE ATTACKED FIRED UPON AND DROPPED DEPTH CHARGES UPON SUBMARINE OPERATING IN DEFENSIVE SEA AREA.”

Unfortunately, that warning did not cause the island's defense forces to go on alert, nor would the newly installed radar operators report nearly an hour later:

"LARGE NUMBER OF PLANES COMING IN FROM THE NORTH, THREE POINTS EAST."

The operator taking that report passed on the information repeating that the operator emphasized he had never seen anything like it, and it was:

"AN AWFUL BIG FLIGHT."

Of course, we now know that flight was the first wave of the Japanese aerial attack and at 07:45 the attackers achieved complete surprise. In addition to the success of the aerial attack, two of five Japanese midget submarines made it into Pearl Harbor, and one is believed to have fired a torpedo that struck the USS Oklahoma (BB-37) which then turned turtle and sank. The next day President Roosevelt would declare "I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire." America was engaged in what was the bloodiest war in world history. Ward was built at Mare Island in a still unbroken record of 17 days. Under the pressure of an urgent World War need for destroyers; her construction was pushed rapidly from keel-laying on 15 May 1918 to launching on 1 June and commissioning on 24 July 1918. While she was built too late to contribute to WWI, she performed admirably in the first encounter with the enemy of World War II. Her sinking of the Japanese submarine was not credited for years, but then in 2009 the submarine was located by researchers from the University of Hawaii. It was found 1200 ft down off the entrance to Pearl Harbor with a visible shell hole at the base of the conning tower just as LCDR Outerbridge reported 68 years before.

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#Ward#Destroyer#Pearl Harbor#world war 2#world war ii#world war two#Japanese#submarine#december 7

0 notes