#Indigenous literature

Text

I saw this book entitled "Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do is Ask" by Mary Siisip Genuisz and i thought oh I HAVE to read that. The author is Anishinaabe and the book is all about Anishinaabe teachings of the ways of the plants.

Going from the idiotic, Eurocentric, doomerist colonialism apologia of that "Cambridge companion to the anthropocene" book, to the clarity and reasonableness of THIS book, is giving me whiplash just about.

I read like 130 pages without even realizing, I couldn't stop! What a treasure trove of knowledge of the ways of the plants!

Most of them are not my plants, since it is a different ecosystem entirely (which gives me a really strikingly lonely feeling? I didn't know I had developed such a kinship with my plants!) but the knowledge of symbiosis as permeating all things including humans—similar to what Weeds, Guardians of the Soil called "Nature's Togetherness Law"—is exactly what we need more of, exactly what we need to teach and promote to others, exactly what we need to heal our planet.

She has a lot of really interesting information on how knowledge is created and passed down in cultures that use oral tradition. The stories and teachings she includes are a mix of those directly passed down by her teacher through a very old heritage of knowledge holders, stories with a newer origin, and a couple that have an unknown origin and (I think?) may not even be "authentically" Native American at all, but that she found to be truthful or useful in some way. She likes many "introduced" plants and is fascinated by their stories and how they came here. (She even says that Kudzu would not be invasive if we understood its virtues and used it the way the Chinese always have, which is exactly what I've been saying!!!)

She seems a bit on the chaotic end of the spectrum in regards to tradition, even though she takes tradition very seriously—she says the way the knowledge of medicinal and otherwise useful plants has been built, is that a medicine person's responsibility is not simply to pass along teachings, but to test and elaborate upon the existing ones. It is a lot similar to the scientific method, I would call it a scientific method. Her way of seeing it really made me understand the aliveness of tradition and how there is opportunity, even necessity, for new traditions based upon new ecological relationships and new cultural connections to the land.

I was gut punched on page 15 when she says that we have to be careful to take care of the Earth and all its creatures, because if human civilization destroys the biosphere the rocks and winds will be left all alone to grieve for us.

What a striking contrast to the sad, cruel ideas in the Cambridge companion of the Anthropocene, where humans are some kind of disease upon the Earth that oppresses and "colonizes" everything else...!...The Earth would GRIEVE for us!

We are not separate from every other thing. We have to learn this. If I can pass along these ideas to y'all through my silly little posts, I will have lived well.

#symbiosis#the ways of the plants#you are a caretaker#you are not separate from every other thing#indigenous literature#books

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sun makes the day new.

Tiny green plants emerge from earth.

Birds are singing the sky into place.

There is nowhere else I want to be but here.

I lean into the rhythm of your heart to see where it will take us.

Joy Harjo, For Keeps

#Joy Harjo#For Keeps#Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings#sun#sunny day#green#plants#growth#spring#spring quotes#birdsong#birds#sky#heart#love#love quotes#American literature#Indigenous literature#Indigenous poetry#BIPOC author#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

rainy morning with a good book 😌

#book tumblr#bookaholic#bookblr#bookish#booklr#books#books and literature#bookworm#book aesthetic#book blog#book photography#reading#indigenous literature#books and reading#books and coffee#bibliophile

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I came into this world already scarred by loss on both sides of my family. My Indigenous side; my European side. My father and my mother were the kind of damaged people who should never have had children. But of course, they had me, and so my first language was loss."

Deborah Miranda, When Coyote Knocks on the Door (2021)

#quotes#literature#lit#poetry#spilled ink#modern literature#poets of color#native literature#indigenous literature#native authors#native writers#women authors#women writers#queer authors#queer writers#indigenous writers#indigenous authors#indigenous women#native american literature#deborah miranda#american literature

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

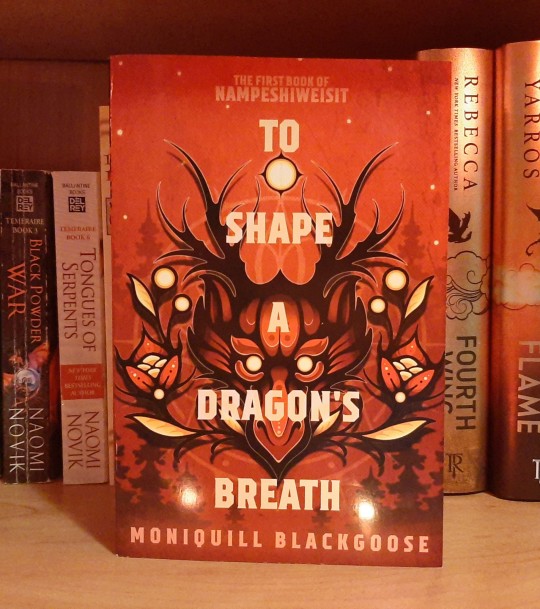

Mixing Magic and Science to Shape Dragon Breath

I'd be lying if I said dragons weren't my favorite magical creatures. There are literally two of them on my desk right now, and I have handed more people the Temeraire books than I care to count. That said, the vast majority of my dragon experience is with what I'm gonna call white westerner dragons. If they're not literally fantasy British, they're inspired by fantasy British dragons, and the dragon world is just a lot bigger than that. So I was absolutely delighted to find a book with a Nampeshiwe and broaden my dragon horizons. Let's talk To Shape A Dragon's Breath.

When Kasaqua chooses Anequs to be Nampeshiweisit, it is largely a matter of safety that first convinces Aneques to leave Masquapaug to learn the skiltakraft to effectively Shape Kasaqua's breath. However, this is an Indigenous woman walking into the heart of Fantasy North America with flavors of Fantasy Nordic Countries, so... colonialism, white supremacy, racism, and imperialism are massive themes and major roadblocks that Anequs experiences. And experiences again. And again. And again. From literally everyone, from her friends, to uneasy allies, to indifferent classmates to bitter enemies. The nuance and variation in the racism that Anequs goes head to head with was stunning--as in it left me absolutely stunned.

On top of that, the world is developed to the point that Frau Kuiper keeps laying out multifaceted, multi-party political issues and Anequs just keeps having to go "literally all of these perspectives share the assumption that my people are uncivilized and need either exterminating or civilizing. What if we tried assuming we are people just as civilized as you with a culture culture traditions just as deeply held?" It's amazing how many characters tell Anequs that she is rude for suggesting that she is a person. Like the number of people I wanted to punch while reading was astounding.

That said, no character in this book is a simple allegory or one-dimensional caricature. Theod Knecht was separated from his family and his people at birth and raised to believe that the other way to be a person was to be Anglish--and even then, he could never be Anglish enough to be fully human. His arc is the complicated emotions of unlearning a system that says you have no worth and reconnecting with your people.

Sander is Anglish and coded as Autistic, but he and Anequs have one of my favorite friendships in this book. They take each other day by day on their own terms and at their own paces, and honestly Sander is just a sweetheart.

Liberty is in an interesting position because she is indentured and living in an Anglish society, which prohibits same-sex relationships. Which does not stop Anequs from expressing her feelings for Liberty in ways that are safe and supportive of Liberty. These two are darling and I genuinely cannot wait to see where they go in the sequel.

Then we come to Kasaqua. Kasaqua is just literally playfulness and joy in dragon form, and she is a delight. She isnt as talkative as say Naomi Novik or Rebecca Yarros's dragons are, but she is expressive and personality-filled nonetheless. There is also her deep-seated joy at [redacted because that's kind of a major spoiler and I don't want to spoil this book].

All these relationships really form and solidify at Kuiper's Academy of Natural Philosophy and Skiltakraft, to which Anequs receives a full sholarship. The school is like a mix of senior high school and undergrad at university, since students between 16 and 20 attend. Most of the students are male, with Anequs and Marta the only female students in attendance for this book. The school is run by Frau Kuiper, who, in her day, basically pulled a Mulan/Alanna of Trebond to get chosen by a dragon, trained, and then sent to the front of a war where she distinguished herself. Her "pet project" to to use Anequs and Theod to "prove that nackies can be civilized" which is honestly pretty gross and causes a metric ton of friction between her and Anequs. In the process though, Anequs learns lessons that it is debatable whether Frau Kuiper meant to teach her that I think will let her be heard in Anglish society enough to support and preserve her people.

Overall, this book was amazing. It was HEAVY, but it needed to be, and that weight just adds to the reading experience. This is one of those books that just literally everyone should have to read at some point.

#to shape a dragon's breath#moniquill blackgoose#anequs#kasaqua#indigenous literature#indigenous main character#indigenous dragons#dragons#books and reading#books and novels#books#books & libraries#book recommendations

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

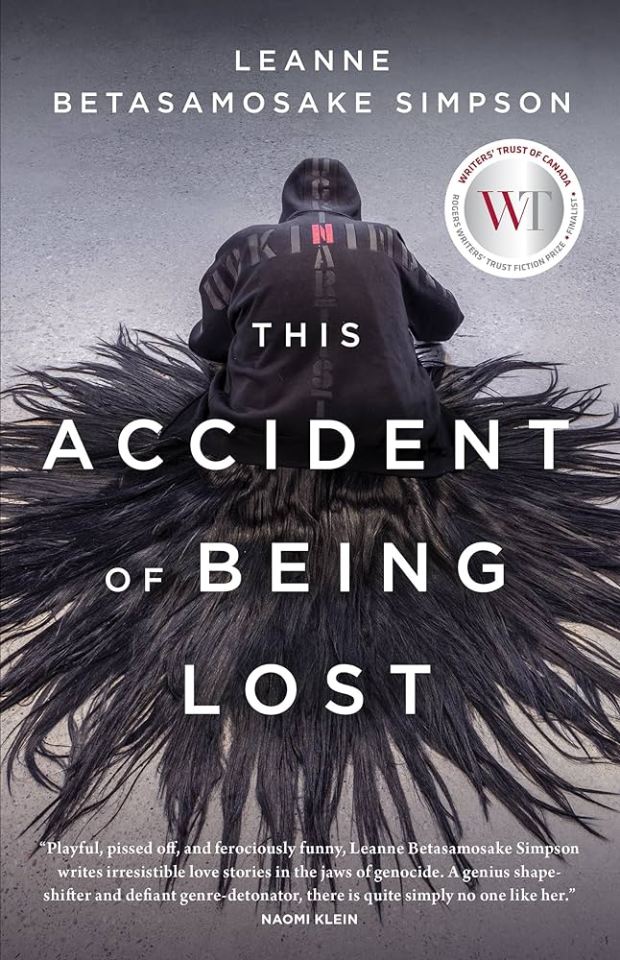

#short story collections#short story collection#the accident of being lost: songs and stories#leanne betasamosake simpson#21st century literature#canadian literature#indigenous literature#mississauga literature#english language literature#have you read this short fiction?#book polls#completed polls

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am doing my best to not become a museum

of myself. I am doing my best to breathe in and out.

I am begging: let me be lonely but not invisible.

Natalie Diaz, “American Arithmetic”

#natalie diaz#American arithmetic#postcolonial love poem#american literature#indigenous literature#quote#literature#lit#poetry#trauma#mindfulness

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Angels don't come to the reservation.

Bats, maybe, or owls, boxy mottled things.

Coyotes, too. They all mean the same thing—

death. And death

eats angels, I guess, because I haven't seen an angel

fly through this valley ever.

Abecedarian Requiring Further Examination of Anglikan Seraphym Subjugation of a Wild Indian Rezervation by Natalie Diaz

#abdecedarian#natalie diaz#quote#poetry#literature#dark academia#aesthetic#dead academia#original post#native authors#indigenous authors#indigenous literature#native poetry#death#dark things

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

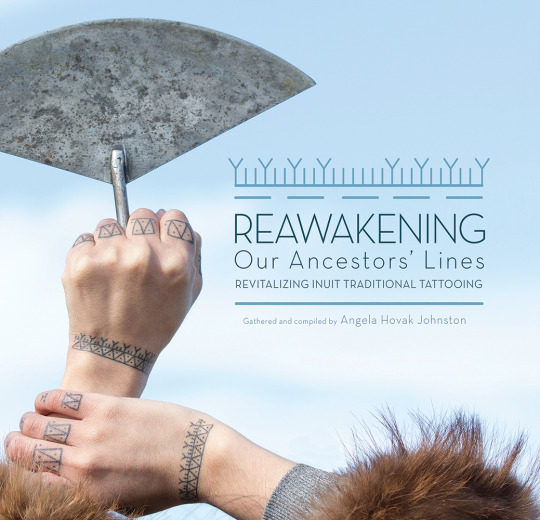

Reawakening Our Ancestor’s Lines and Other AIYLA Titles

When I was in the library the other day, a book cover caught my eye. Somehow I had missed out on this book that was released in 2017. I’m sure I saw the list when it was honored by The American Indian Library Association back in 2020, but I never got my hands on Reawakening Our Ancestors’ Lines: Revitalizing Inuit Traditional Tattooing until this week. It’s a gorgeous book that features Inuit women who are reviving the traditional art of tattooing. The author, Angela Hovak Johnston, learned how to tattoo herself and others and the book shares that journey with others.

For thousands of years, Inuit women practiced the traditional art of tattooing. Created with bone needles and caribou sinew soaked in seal oil or soot, these tattoos were an important tradition for many women, symbols stitched in their skin that connected them to their families and communities.But with the rise of missionaries and residential schools in the North, the tradition of tattooing was almost lost. In 2005, when Angela Hovak Johnston heard that the last Inuk woman tattooed in the traditional way had died, she set out to tattoo herself and learn how to tattoo others. What was at first a personal quest became a project to bring the art of traditional tattooing back to Inuit women across Nunavut, starting in the community of Kugluktuk. Collected in this beautiful book are moving photos and stories from more than two dozen women who participated in Johnston’s project. Together, these women are reawakening their ancestors’ lines and sharing this knowledge with future generations. [publisher summary]

This book is just one of the many that have won or been honored over the years. In case you’ve missed any of the titles, here are a few other YA books that have made the American Indian Youth Literature Award lists:

Apple Skin to the Core by Eric Gansworth (Onandoga)

The term “Apple” is a slur in Native communities across the country. It’s for someone supposedly “red on the outside, white on the inside.” Eric Gansworth is telling his story in Apple (Skin to the Core). The story of his family, of Onondaga among Tuscaroras, of Native folks everywhere. From the horrible legacy of the government boarding schools, to a boy watching his siblings leave and return and leave again, to a young man fighting to be an artist who balances multiple worlds. Eric shatters that slur and reclaims it in verse and prose and imagery that truly lives up to the word heartbreaking.

Firekeeper’s Daughter by Angeline Boulley (Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians)

As a biracial, unenrolled tribal member and the product of a scandal, Daunis Fontaine has never quite fit in—both in her hometown and on the nearby Ojibwe reservation. When her family is struck by tragedy, Daunis puts her dreams on hold to care for her fragile mother. The only bright spot is meeting Jamie, the charming new recruit on her brother’s hockey team.

After Daunis witnesses a shocking murder that thrusts her into a criminal investigation, she agrees to go undercover. But the deceptions—and deaths—keep piling up and soon the threat strikes too close to home. How far will she go to protect her community if it means tearing apart the only world she’s ever known?

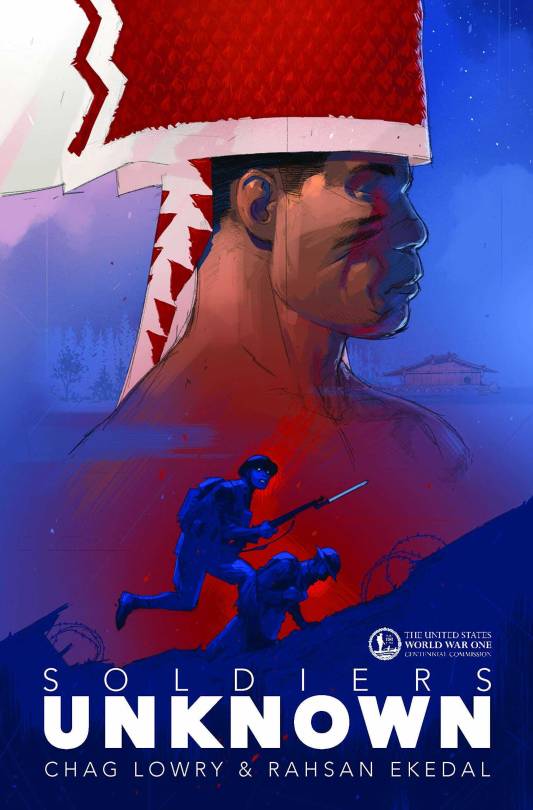

Soldiers Unknown by Chag Lowry (Yurok, Maidu and Achumawi)

The graphic novel Soldiers Unknown is a historically accurate World War One story told from the perspective of Native Yurok soldiers. The novel is based on extensive military research and on oral interviews of family members of Yurok WW1 veterans from throughout Humboldt and Del Norte counties. The author Chag Lowry is of Yurok, Maidu, and Achumawi ancestry, and the illustrator Rahsan Ekedal was raised in southern Humboldt. Soldiers Unknown takes place during the battle of the Meuse-Argonne in France in 1918, which is the largest battle in American Army history.

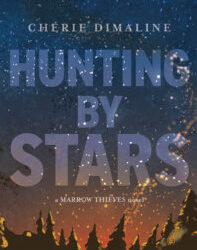

Marrow Thieves and the sequel Hunting by Stars by Cherie Dimaline (Metis Nation of Ontario)

Marrow Thieves – Just when you think you have nothing left to lose, they come for your dreams.

Humanity has nearly destroyed its world through global warming, but now an even greater evil lurks. The Indigenous people of North America are being hunted and harvested for their bone marrow, which carries the key to recovering something the rest of the population has lost: the ability to dream. In this dark world, Frenchie and his companions struggle to survive as they make their way up north to the old lands. For now, survival means staying hidden – but what they don”t know is that one of them holds the secret to defeating the marrow thieves.

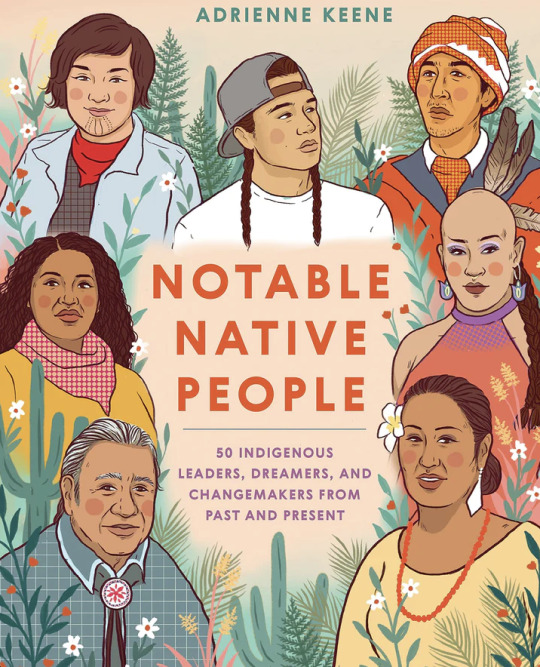

Notable Native People: 50 Indigenous Leaders, Dreamers, and Changemakers from Past and Present by Adrienne Keene (Cherokee Nation) and illustrated by Ciara Sana (Chamoru)

An accessible and educational illustrated book profiling 50 notable American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian people, from NBA star Kyrie Irving of the Standing Rock Lakota to Wilma Mankiller, the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Celebrate the lives, stories, and contributions of Indigenous artists, activists, scientists, athletes, and other changemakers in this beautifully illustrated collection. From luminaries of the past, like nineteenth-century sculptor Edmonia Lewis--the first Black and Native American female artist to achieve international fame--to contemporary figures like linguist jessie little doe baird, who revived the Wampanoag language, Notable Native People highlights the vital impact Indigenous dreamers and leaders have made on the world.

Elatsoe by Darcie Little Badger (Lipan Apache Tribe)

Elatsoe—Ellie for short—lives in an alternate contemporary America shaped by the ancestral magics and knowledge of its Indigenous and immigrant groups. She can raise the spirits of dead animals—most importantly, her ghost dog Kirby. When her beloved cousin dies, all signs point to a car crash, but his ghost tells her otherwise: He was murdered. Who killed him and how did he die? With the help of her family, her best friend Jay, and the memory great, great, great, great, great, great grandmother, Elatsoe, must track down the killer and unravel the mystery of this creepy town and it’s dark past. But will the nefarious townsfolk and a mysterious Doctor stop her before she gets started? A breathtaking debut novel featuring an asexual, Apache teen protagonist, Elatsoe combines mystery, horror, noir, ancestral knowledge, haunting illustrations, fantasy elements, and is one of the most-talked about debuts of the year.

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States for Young People adapted by Debbie Reese (Nambé Owingeh) and Jean Mendoza from the adult book by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Spanning more than 400 years, this classic bottom-up history examines the legacy of Indigenous peoples' resistance, resilience, and steadfast fight against imperialism.

Going beyond the story of America as a country "discovered" by a few brave men in the "New World," Indigenous human rights advocate Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz reveals the roles that settler colonialism and policies of American Indian genocide played in forming our national identity.

The original academic text is fully adapted by renowned curriculum experts Debbie Reese and Jean Mendoza, for middle-grade and young adult readers to include discussion topics, archival images, original maps, recommendations for further reading, and other materials to encourage students, teachers, and general readers to think critically about their own place in history.

Surviving the City written by Tasha Spillet (Nehiyaw-Trinidadian) and illustrated by Natasha Donovan (Métis Nation of British Columbia)

Tasha Spillett's graphic novel debut, Surviving the City, is a story about womanhood, friendship, colonialism, and the anguish of a missing loved one. Miikwan and Dez are best friends. Miikwan is Anishinaabe; Dez is Inninew. Together, the teens navigate the challenges of growing up in an urban landscape - they're so close, they even completed their Berry Fast together. However, when Dez's grandmother becomes too sick, Dez is told she can't stay with her anymore. With the threat of a group home looming, Dez can't bring herself to go home and disappears. Miikwan is devastated, and the wound of her missing mother resurfaces. Will Dez's community find her before it's too late? Will Miikwan be able to cope if they don't?

To learn about even more books that have received this award, be sure to check out the AILA page.

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring the Shadows of Indigenous Dark Fiction: Never Whistle at Night Anthology

Shaina Tranquilino

October 27, 2023

In a world where diverse voices are increasingly being heard, literature plays a crucial role in amplifying marginalized perspectives. One such remarkable work is the anthology "Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology," edited by Shane Hawk and Theodore C. Van Alst Jr. This collection of haunting stories offers readers a unique glimpse into the rich tapestry of indigenous folklore, horror, and speculative fiction. As we delve into the depths of this book, we discover tales that challenge stereotypes and provide a fresh perspective on traditional storytelling.

Diverse Voices Unleashed:

Never Whistle at Night stands as an important literary milestone in its ability to bring together Indigenous authors from various tribes and backgrounds. Each story is crafted with immense care, capturing the essence of cultural heritage while embracing the dark realms of fiction. The authors skillfully blend elements of horror, fantasy, and suspense to create narratives that both entertain and educate.

Exploring Indigenous Folklore:

One notable aspect of this anthology is its exploration of Indigenous folklore, which has often been overlooked in mainstream literature. With each turn of the page, readers are transported into worlds filled with spirits, supernatural creatures, and ancient traditions—elements deeply rooted in native cultures. These stories serve as powerful reminders that Indigenous peoples have their own myths and legends that deserve recognition.

Challenging Stereotypes:

A prominent theme throughout Never Whistle at Night is challenging stereotypes surrounding Indigenous communities. By weaving these narratives within dark fiction genres, the authors subvert expectations and offer nuanced portrayals far removed from common clichés. They confront issues such as colonialism, displacement, identity struggles, and generational trauma head-on while simultaneously delivering captivating plots.

Blending Darkness and Light:

The editors' expert curation allows for an engaging balance between darkness and light within the anthology's pages. While some stories may leave readers trembling with fear, others offer solace and hope. This careful equilibrium serves as a reminder that Indigenous experiences encompass both the shadows and the light, just like any other culture.

Impactful Storytelling:

"Never Whistle at Night" showcases the immense talent of its contributors, each story delivering a unique experience to the reader. From chilling tales set in contemporary urban environments to more traditional stories deeply rooted in cultural heritage, there is something for everyone within these pages. The authors' ability to effortlessly blend genres creates an anthology that transcends labels and speaks to a universal human experience.

In "Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology," editors Shane Hawk and Theodore C. Van Alst Jr. skillfully bring together Indigenous voices that deserve wider recognition. This collection offers readers an opportunity to immerse themselves in captivating narratives while challenging preconceived notions about Indigenous cultures. By showcasing dark fiction infused with rich folklore and thought-provoking themes, this anthology leaves a lasting impact on its audience—a testament to the power of diverse storytelling and literature's ability to bridge gaps between cultures.

#never whistle at night#Indigenous#Indigenous dark fiction anthology#stories#legends#Indigenous dark fiction#anthology review#book recommendation#Indigenous authors#horror#Indigenous literature

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am the evergreen with fading needles

roots deep in sandy soils

slightly burned from ancient fires

a home to only the survivors

Tenille K. Campbell, I am not a wild strawberry

#Tenille Campbell#I am not a wild strawberry#nedi nezu#Good Medicine#evergreen#nature#nature quotes#ancient fires#survivors#Indigenous literature#poetry#poetry quotes#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

maybe go read some Indigenous feminist lit and shut the FUCK up lmao

I have! indigenous literature is actually an interest of mine. my personal favorite is paula gunn allen. just for you & for the sake of indigenous feminist lit, i'm going to list some indigenous women authors here. not all of these are specifically feminist literature, but many are!

paula gunn allen (laguna pueblo)

louise erdrich (ojibwe)

heid e erdrich (ojibwe)

leslie marmon silko (laguna pueblo)

robin wall kimmerer (potawotami)

joy harjo (muscogee)

linda legarde grover (ojibwe)

Zitkála-Šá (dakota)

wilma mankiller (cherokee)

natalie diaz (mojave)

bamewawagezhikaquay, aka jane johnston schoolcraft (ojibwe)

if any woman has more recommendations, please feel free to share! i love to share indigenous literature

#berry talks#radical feminism#radblr#radfem safe#radfems do touch#radfems do interact#hatemail#radical feminists do interact#feminism#radfem#indigenous literature#indigenous women writers#indigenous feminism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"the histories of our queerness, transness, non-binaryness, arc back to originality and our vertebrae are blooming heart berries and dripping seedlings"

Joshua Whitehead, "Introduction," Love After the End: An Anthology of Two-Spirit and Indigiqueer Speculative Fiction

#quotes#literature#lit#poetry#spilled ink#modern literature#native literature#indigenous writers#indigenous authors#indigenous literature#indigiqueer#two spirit writers#two spirit authors#queer literature#queer authors#queer writers#native authors#native writers#joshua whitehead#love after the end

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes You Grow Into Your Books

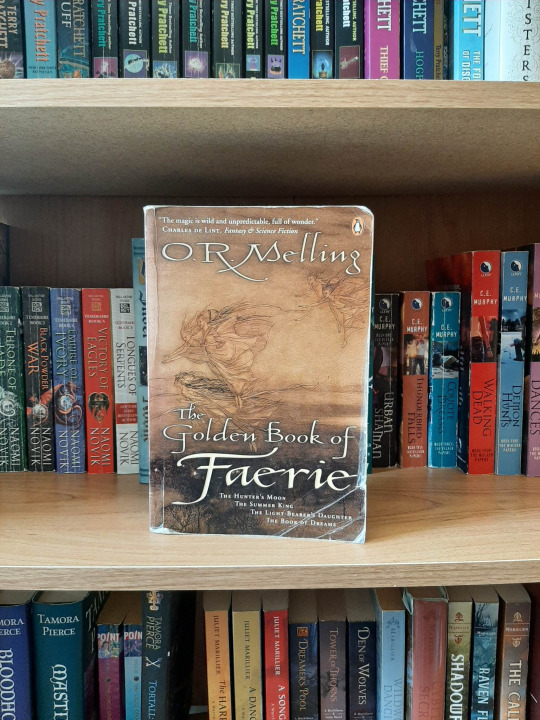

I was objectively too young when I picked up this book at like, ten or eleven, having just read Terri Windling and Ellen Steiber's The Raven Queen and wanting more faeries with some edge to them, and read my way through four novels about magic and fairies in Canada and Ireland. On that first read, solidly 80% of it went straight over my head, and I couldn't figure out why. (Reader, the reason is because I was a tiny human who was still at a middle grade level and this book is pretty firmly YA but literally nobody ever told me no where books were concerned--and thank you to everyone who supported my reading from a young age!) That said, there was something about the book that wouldn't stop worrying at the back of my mind, so over the next three years, I kept reading and rereading, and slowly the stories took shape in my head and I learned why the books stayed with me. I spent a long time with this book, so let's talk The Golden Book of Faerie.

This is a spoilery post, so be aware if this book is for some reason on your TBR!

A word I didn't know when I decided I wanted to read this book is omnibus, but that's what this book is--an omnibus edition of four OR Melling novels.

The Hunter's Moon is the first of the four books, and it really sets up the complex relationship between family and faerie that will permeate the rest of the books. It follows Gwen and Findabhair's (fin-ah-veer's) reunion in Ireland after a while apart, and Findabhair's entanglement with Finvarra, a faerie king. Finvarra either falls in love with/selects for the Hunter's Moon sacrifice Findabhair, and Findabhair decides she is in love enough to go through with it. Gwen basically decides that no, this is not acceptable, and finds help fron Dara, cute guy and folkloric king of Ireland; Granny (Grania Harte, not Granny Weatherwax) who is a fairy doctress; Katie Quirke, who is a farmer with big dreams; and Mattie O'Shea, a middle-aged Managing Director of a firm who is also a married new dad. I would be absolutely remiss to point out the resemblances to Lord of the Rings here, because Gwen quite literally pulls together a fellowship to try to save Findabhair and faerie.

The fellowship faces down Crom Cruac, the Great Worm. It...does not go great. I wasn't kidding when I made the LotR comparison, there is no great, glorious, heroic battle at the climax of this book. They are overpowered and beaten to a pulp, and Findabhair gets Laterose-ed into the ground, and suddenly the company's reason for fighting lies dying. Finvarra chooses a heroic sacrifice, and the rest of the company takes itself home to recover. A year and a day later, the Company of Seven gather again to mark to day, and Finvarra--a notably human Finvarra--returns.

The overarching mood of this story is of how love and grief intertwine, and it is really truly well done.

The Summer King shifts protagonists to focus on Laurel and Honor Blackburn, a pair of twin sisters violently separated by what seems, on the surface, to be a hang-glider accident. We find later that it was, in truth, a faery attack, but for the long year between Honor's death and Laurel's introduction to Faery, all Laurel knows is that her sister is dead. And the kicker for the family--although this is implied rather than stated explicitly on page--is that they didn't even have a body to bury because Honor crashed into water, and the glider took her too far down to be recovered.

Along for the ride with Laurel is Ian Gray, troubled young pastor's son and the new--and EXTREMELY reluctant--Summer King. He and Ian more share a body and mind than are the same person, so poor Ian is fighting a massive battle and Laurel is still so wounded by Honor's death. The pair bond a bit on Grace O'Malley's ship, and even when it is revealed that Honor was a casualty of the Summer King's violence, Laurel and Ian still work together to light the midsummer pyre and keep the human and faerie worlds together.

Dead is dead in the human world still, so Honor cannot return to her life. But thanks to Laurel, she can live on in Faerie. And Laurel also grows enough to pull Ian back from the edge as well.

So as the eldest of three girls, literally the worst thing I can imagine is losing a sister, so this book made me SOB. But the compassion required for forgiveness and healing stuck, and the book expands the theme of the intertwining of love and grief while giving it some nuance and complexity by weaving in compassion and forgiveness.

The Light-Bearer's Daughter is possibly the closest thing to a traditional "fairy tale" in this book, because Dana is all of eleven in this book, far younger than the teen protagonists of the last two. That is why when Dana stumbles ass-backwards into the woods and is handed a mission by the Summer Queen--none other than Honor Blackburn, for those of you playing along at home--she ends up terrifying her single dad by bailing on him right before a move from Ireland to Toronto to complete her mission.

This book is very much a fairy tale because it's Dana learning, growing, getting square with the fae mother who left her and her father, and then accepting the move to Canada. This is possibly my least favorite of the three novels, but it's important background for Dana for the next book.

The Book of Dreams takes Dana as its protagonist again, but now she is a troubled thirteen who has not adjusted to life in Toronto. It also weaves in the major players from the three previous books, because whether Dana is ready or not, something big enough to threaten the existence of faerie is coming, and Laurel and Gwen need to make sure that this teenager survives to battle this.

The best part of this book is how the mythology and lore expands. We get the Irish/English faerie lore that we've been accustomed to in three previous books, but thanks to the multiculturalness of Toronto, we also get First Nations and Indian (that's as in India, not as in Native American) lore as well, and the three work together beautifully. This was the first time I had ever seen Irish and North American Indigenous mythologies together, but CE Murphy does a version of it in the Walker Papers, and these two seem to work together really well.

I also love the way the different threads of this book weave together, although we are never free of the balance between love and grief and the costs of having a foot in both the mortal and faerie worlds.

Overall, despite being objectively too young for this book when I first picked it up, it was foundational in shaping what I prefer in faerie stories (and actually probably explains part of why how the fae in the Dresden Files are handled pisses me off) and it really helped show me that there was nothing that was too hard for me to read. It might take spending some time with a text and rereading and reflection to parse my responses, but this book really was my first experience with a challenging text that I had to work to really get through, understand, and appreciate.

It's the combination of the lesson on how to approach challenging texts and the vibes that I learned to appreciate that really made this book stick with me, and I adore The Hunter's Moon unreasonably.

#faeries#fae#or melling#the golden book of faerie#ya fantasy#ya fiction#canadian literature#irish literature#indigenous literature#books and reading#books and novels#books#books & libraries#book recommendations

6 notes

·

View notes