#Australian healthcare

Text

An Overview of the Australian Healthcare System

The "Australian healthcare system" is a complex network designed to provide comprehensive and accessible healthcare services to its citizens. Known for its universal approach to healthcare, the system aims to ensure that all Australians have access to high-quality medical care regardless of their socio-economic status. Read More:

An Overview of the Australian Healthcare System

0 notes

Text

'A ROCK THE SIZE OF MY FIST' BY JENNIFER DOWN

September 11, 2017 | The Lifted Brow

Photo by Alexina McDougall. Supplied with permission.

1.

There are so many things in the world that I love. Dozing in the sun at the beach after swimming, limbs exhausted, salt drying stiff in my hair. Cutting up vegetables into neat, symmetrical pieces. Any food preparation, really, particularly if I’m listening to a good podcast. The way my dog presses his warm flank against my leg. Fragrant flowers: daphne, freesias, gardenias, violets, jasmine. Dramatic flowers: peonies, magnolias, proteas, foxgloves, hydrangeas, pansies. The strange sick swelling in my chest evoked by certain moments in particular songs, even happy ones, as though my body is unable to metabolise so much emotion. Flying into a city at night and seeing the lit gauze of its streets from the air. The scrunch of a stranger’s fingers at my scalp when the hairdresser gives me a perfunctory shampoo head massage. Cycling on a balmy night when the streets are quiet. Taking a bath when I’m a little drunk. Most things when I’m a little drunk, when my body loosens and the world softens at its edges. The quickening I get when I think of an idea for a story, or a solution to a problem of plot, or when a knot of words unravels in a clean sentence unexpectedly. Stretching out my muscles, sitting on the floor with my nose to my knees. The pearly pink light of a winter dusk.

So many happy memories. My grandfather pricking our names into the skin of green tomatoes in his garden so that when they ripened fat and full, the size of my fist, they were tattooed for us. He told me and my sister the fairies did it. Or him seated at the old player piano with its yellowed keys, badly in need of tuning. He’d never had lessons, and could not read music, but he had a wonderful ear, and turned out credible show tunes and ragtime numbers. He had a non-Parkinsonian tremor in his hands, which more or less disappeared when he played; or, at any rate, did not interfere with his playing. I remember the thud of the sustain pedal beneath his foot, the warped, tinny tone of the notes.

I remember the thud of the sustain pedal beneath his foot

The rare bioluminescent algae I once saw at night down in far-east Gippsland, at a friend’s parents’ house, sparkling in the black salt lake water. My friends and I lay on our bellies on the wooden jetty, transfixed by it. Phosphorescence as bright as the constellations in that country sky. Starlight prickled all around us.

Mountain hiking alone, very happy, a thirty-three-degree afternoon; lactic acid burning in my calves, hot air burning in my lungs; body feeling strong and capable.

Dancing with a friend at a Lee Fields show on a hot summer night in Berlin, moving in helpless ecstasy as he sings La-a-a-a-dies, right at the front of the stage, ahead of all the sober Germans; Fields reaching out to shake our hands at the end of his set, the three of us laughing and spangled with sweat.

Last week I cut through the Fitzroy Gardens at nightfall, walking home from work, and saw the jonquils with their tender faces turned to the sky. The Gardens smelled earthy. It was the last week of winter. The air was blue. The streetlights shone in that way that always makes me think of the line in the Sara Teasdale poem – all the lights are dim and pearled – and overhead, the leaves were sibilant. I watched a man throwing a ball for his dog again and again using one of those moulded plastic scoops, and it pleased me in a gentle way because I could see the dog was having a really good time, and it made me think of my own dog, who is not so interested in chasing balls as being as he is in being touched.

But when I’m depressed, all of it ceases to matter

Pretty light, cold air, turned soil, a quiet walk, a stranger’s kelpie: these things mollify me at my normal, baseline level of mental health. They are enough to constitute a pleasant walk home. But when I’m depressed, all of it ceases to matter. The world is still there, but it’s ugly and futile. My brain attaches semantic attributes to the shapes of things so that I recognise them as ‘a dog’ or ‘some jonquils’, but these stir in me no feeling, no mild joy.

In a dissociative episode, I might doubt that I am, in fact, seeing a dog chasing a ball, and become momentarily convinced that rather than crossing through the Gardens, I was obliterated by a car as I crossed Victoria Parade.

This was not, by the way, leading to a metaphor about the old black dog – which I’ve always found an idiotically benign metaphor for a debilitating and endemic illness with a high mortality rate. Sometimes a dog is just a dog.

In Teasdale’s Spring Night she laments a loss:

'Oh, is it not enough to be

Here with this beauty over me?

My throat should ache with praise, and I

Should kneel in joy beneath the sky.

O, Beauty are you not enough?

Why am I crying after love?’

So many things in the world that I love, so many happy memories. But, as Teasdale wrote, there are times when none of it is enough.

2.

To frame depression as beautiful is to imagine it, falsely, as John Everett Millais’ Ophelia: an alabaster body wreathed in wildflowers, drowning prettily.

3.

Driving in his old Holden Commodore, my dad played his favourite rock and roll tapes and told me stories about the songs. Jimi Hendrix’s ‘The Stars that Play with Laughing Sam’s Dice’ was said to be a code for LSD, the name of which I also recognised from another of dad’s tales about ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’; ‘Tears in Heaven’ was written for Eric Clapton’s son, who’d fallen from a 53rd-floor balcony and died; ‘Wish You Were Here’ was about Syd Barrett, whose breakdown led to his eventual departure from Pink Floyd. My parents always talked to me as though I were an adult, so even at five or six, I had developed a strange collection of stories, many of them tragic, about these fantastically gifted but ill-fated stars. They were friendly ghosts to me, those dead rock stars in swimming pools. Poor Jimi. Poor Karen Carpenter, poor Janis Joplin, poor Buddy Holly. Poor Jim Morrison, Robert Johnson, Mama Cass, Marc Bolan, Sid Vicious, Muddy Waters. Many of them hadn’t died from anything related to mental illness at all, but their stories swam together in my head. Car accident, heart attack, heroin. Some drug overdoses were dubiously accidental.

As a child I was mesmerised by Don McLean’s ‘Vincent’, which imagines the life of the gifted but blighted Dutch painter in bittersweet, folky tones. You took your life, as lovers often do, he sings, but I could’ve told you, Vincent / this world was never meant for / one as beautiful as you. The ‘tortured artist’ trope appears again and again in Western art, history and fiction. Woolf and Plath and Eliot and Cobain, and others too many to name. Of course, there have been thousands more institutionalised, medicated, subjected to experimental therapeutic practices, who suffered terribly from mental illness, but who history has forgotten. They were not known for their art, or for anything much, by the general public; they were washerwomen and abattoir workers and railway workers and accountants and schoolteachers and store clerks, and no one documented their lives. Their illness was ugly and shameful instead of something wretchedly exquisite that could be mined for their work. It cost them jobs and houses and marriages and children, and no one remarked, in rose-tinted recollection, on what poisonous genius it all might be ascribed to.

Some research suggests that that high levels of schizotypy...are positively associated with creativity

Some research suggests that that high levels of schizotypy – a cluster of personality traits which are evident, in varying degrees, in us all – are positively associated with creativity. Moreover, self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety have been shown to be positively associated with psychometric ratings of schizotypy. But while a variety of studies have demonstrated a correlation between creativity and psychopathology, this link is not necessarily causative, if, in fact, it exists at all. Much of this research has been criticised for the way it defines and measures both creativity and mental illness. Much of it has been undertaken in the United States and in Europe. And much of it is conflicting: American clinical psychologist Kay Redfield Jamison notes that while individuals with bipolar disorder are overrepresented in creative professions, “[the] lack of association between unipolar depression and creative occupation is seemingly inconsistent with studies that have found an elevated rate of depression in artists, writers and composers.” How can we possibly find the answers when we’re effectively asking questions in one language, and answering in another? How can we know so much, and so little? And what role do situational or environmental factors play in depression?

A 2015 report by Victoria University and Entertainment Assist surveyed a cross-section of almost three thousand people who worked in entertainment industries across Australia, from performers to technicians. It found that Australian entertainment industry workers experienced symptoms of depression at a rate five times higher than in the general population, and attempted suicide more than double as often as members of the general population. They experienced ‘moderate to severe’ symptoms of anxiety at a rate ten times higher than in the general population. But the report concluded that rather than being linked to an inherent susceptibility toward mental illness, these statistics were attributable to a range of factors associated with working in the industry – financial instability and poor wages, irregular work hours and sleep disturbances, and rampant bullying, racism, sexism and sexual assault. The report recommended the development of industry-specific early intervention programs. Anecdotally and through personal experience, I know many of these problems are present in the literary industry, too. And I can posit half-baked theories about my own anxiety, for example, in relation to my writing: most writers I know are hyper-sensitive people, and most good writers are finely attuned to others and to their environments. This sensitivity is often a positive trait in terms of their work; in day-to-day life it can be terrifying, smothering and exhausting.

For centuries, people have made art despite their depression, not because of it

It is indubitably critical that we better support people dealing with mental illness, irrespective of their occupation. But we must, too, dispel the idea that anguish breeds art; that depression is somehow fecund.

The painter Edvard Munch was famously fearful that, cured of his illness, he would no longer be an artist: “[Treatment] would destroy my art. I want to keep those sufferings.” But a century on, we know more about mental illness, though there is undoubtedly much more research to be done. For centuries, people have made art despite their depression, not because of it.

Photo by Justin Wolfers. Supplied with permission.

4.

The sound of depression, for me, is The Drones’ ‘Shark Fin Blues’, or Harmony’s ‘Cacophonous Vibes’, songs which move me enormously, but to which I can only bear to listen when I’m well. Both songs that build slowly, with restrained guitar and drums giving way to frenzied, distorted noise, both songs that feature swelling female backing vocals as the male singer’s voice cracks and shreds with emotion. Both songs whose berserk grief is most keenly felt when they’re played at great volume.

5.

My GP, a fiercely intelligent, emotionally astute physician who has treated me since I was a child, retires. At some point in the months that follow, the efficacy of the anti-depressant I have taken on and off for three years begins to wane, and I decide to consult a new doctor. I find a general practice near my house, and make an early-morning appointment. The doctor is in his early fifties, perhaps, and he’s handsome in a TV doctor way – crinkly eyes and wavy grey hair. The bio on the practice website informs me he is also interested in music. I sit in his cold room with its leadlight window and explain that for some time now, I have been feeling progressively more and more depressed. I am articulate, I am lucid, I am stolid. Perhaps too stolid. Perhaps one should not be able to discuss their despair with relative equanimity.

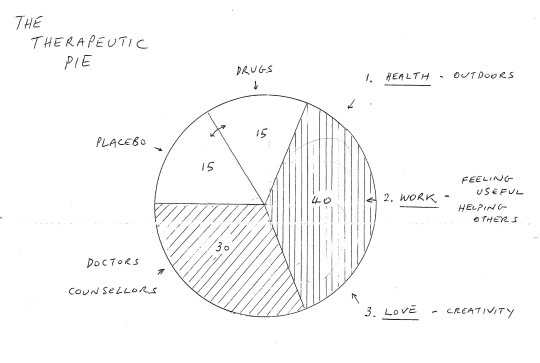

The handsome doctor sighs. The way I like to approach mental health is to treat it holistically, he says. Then something about being reluctant to prescribe medication to every sad person who walks into his office. He asks if I’m familiar with the therapeutic pie. I am not. From his desk drawer he extracts a photocopied, hand-drawn pie chart, which he places on the table between us. Medication, he tells me, is just one part of the therapeutic pie. On the chart, this is marked as ‘DRUGS’, and represents 15 per cent. Another segment the same size is labelled ‘PLACEBO’. The next segment is ‘DOCTORS COUNSELLORS’; 30 per cent. The largest segment, the remaining 40 per cent of the pie, is made up of the following:

1. HEALTH – OUTDOORS

2. WORK – FEELING USEFUL HELPING OTHERS

3. LOVE – CREATIVITY

Supplied by the author.

The good doctor sighs almost imperceptibly. His demeanour changes; he becomes abrupt. He prescribes a different variety of SSRI. The dosage on the new script appears radically different from my current drug. When I query this, he tells me the chemical composition is different. I ask whether I should taper off the current drug. The doctor says no; I should not take it anymore. I should have three days ‘clean’, with no medication, then start the new drug the following day. He barely looks at me as I scuttle from the room, still wearing my winter coat.

SSRI discontinuation syndrome is, in fact, well-documented, a fact I’m aware of from previous medical advice; when withdrawing in the past, I’ve been told to gradually lower my dosage. But my depressed brain is passive; no longer able to argue; no longer trusts its knowledge, so I don’t mention it.

My depressed brain is passive; no longer able to argue; no longer trusts its knowledge

For a week, I walk around in a daze. I am forgetful. I am unable to concentrate long enough to finish typing an email. My fingers neglect to hold objects; my coffee cup slips to the floor. When I blink, my vision shudders. The world seems vertiginous. These are common withdrawal symptoms. Months later, this episode will enrage me. But for now, I start the new medication. I wait for it to take effect. The days are so long.

6.

Depression is different things to different people. For some, it’s sleeping all the time to escape consciousness. For others, it’s being kept awake all night by bleak insomnia. It might involve overeating, or disordered eating, or not eating at all; it might be able to be disguised in front of family or colleagues, or it might be readily apparent; it might manifest in physical symptoms, like fatigue, headaches and muscular pain, or in behavioural symptoms, like withdrawing from loved ones, difficulty performing personal hygiene tasks, and substance abuse. It might be several of these things or none of them. Symptoms might change, or disappear and reappear with different episodes.

I am descended from worriers on both sides of my family tree. My grandparents were of an era and class that rarely treated, if acknowledged, illnesses like depression, bipolar disorder and clinical anxiety. My maternal grandmother was raised by her father and her grandmother after her mother left, or was told to leave – I’ve heard several versions of the story – following what would likely today be diagnosed as postpartum psychosis. My maternal grandfather learned yoga and meditation, in the community hall classes where his florist wife, the same woman abandoned by her mother as a baby, taught flower-arranging techniques on a different weeknight. He used to practice daily, after arriving home from work, to alleviate his anxiety. My mother recalls sneaking into her parents’ bedroom as a child to peek in on him where he sat at the foot of his bed, concentrating on his breath, and tickle his feet.

After the handsome doctor and the therapeutic pie, it takes me two months to conjure the velleity, energy and confidence to seek out another GP. In this time, my depression worsens so that I begin to fantasise about stepping out in front of the trucks that hurtle past on the major arterial I cross walking to work. As it happens, the new physician is thorough, sympathetic and practical. She takes copious notes, then gives me the K10 to fill out. The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale is a simple checklist-style test that asks the patient to self-report the frequency of a range of symptoms associated with clinical depression and/or anxiety. It is not infallible, but it is a quick, simple and cost-effective starting point for assessing the mental health of someone you’ve just met, and how to best proceed with treatment. Based on my score, the doctor decides to increase my dosage, with a view to switching medication if it remains ineffective. She will consider psychologists she believes to be a ‘good fit’ for me, and give me a referral. She will get the ball rolling with a psychiatrist in case I require one at a later date, to avoid waiting lists should things become critical. She draws my blood and tells me I need more iron, more vitamin D, and so on; that these dietary factors won’t cure depression, but have been linked to it. She makes a plan with small steps, achievable by even someone paralysed by depression.

She makes a plan with small steps, achievable by even someone paralysed by depression

It takes many months and yet another change in medication, but slowly, things begin to change, and I begin to feel human once more. It is not lost on me how fortunate I am to have found this doctor. And I’m acutely aware, even as I write this, of the privilege I hold, and the ways in which it enables me to seek medical advice and receive treatment, even when the process is fraught with difficulty. I’m a white, cisgender, able-bodied woman; a tertiary-educated native English speaker with higher-than-average medical literacy.

I’m aware of my brothers and sisters incarcerated in detention centres, who, having already suffered traumas greater than I can imagine, and fled their homes, are subjected to further human rights abuses sanctified by the government whose protection they sought.

I’m aware of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who experience, daily, the ongoing violence of colonialism, and whose health outcomes – already poorer than those of non-indigenous Australians – are at the mercy of a largely white-centric healthcare model.

I’m aware of people of colour and people who experience quotidian discrimination on the basis of their ethnicity or religion. There’s a wealth of medical literature identifying racism as a pathogen of depression and anxiety.

I’m aware of the LGBTQI+ community, who face a variety of barriers in accessing medical care, such as homophobia, transphobia and heterosexism, as well as unique risk factors for psychological distress associated with their sexuality and/or gender identity; indeed, LGBTQI+ people have the highest suicide rates of any population in Australia.

I’m aware of people whose physical disabilities present a challenge in accessing certain services and buildings, and those whose hearing impairments or intellectual disabilities, for example, can render communication difficult.

I’m aware of migrants and non-native English speakers who may experience complex linguistic and cultural barriers to accessing healthcare – and the native English speakers whose literacy skills make it arduous or daunting to navigate the system.

If it’s this hard for someone like me to get the help I need, there are many, many others for whom it’s nigh on impossible

I’m aware of children in out-of-home care, exposed to far greater rates of physical, psychological and sexual abuse than any of us would like to imagine possible – often at the hands of the very figures supposed to protect them.

I’m aware of people who can’t afford the price of getting to a clinic, or the prescription, or the psychologist, or the outpatient care.

Photo by the author.

7.

Once I stood with some friends at the top of a colossal waterfall. We were humbled by its size and splendour, and kept discovering in it new wonder as we examined it from different vantage points. A stranger took a picture of the four of us standing in front of it in our spray jackets. In the photo, the waterfall’s scale is not readily apparent, but our faces are full of joy. Before we turned to go, one friend joked that we each pick up a rock from the ground and hurl it into the water while naming something we wanted to let go of. She cried Manipulative people! and we all applauded and laughed. The second friend yelled her ex’s name as she flung a sizeable rock into the rushing water. The third hollered Workplace sexism! as her stone sailed toward the falls. I was self-conscious, torn between a pisstake and sincerity. It was the daggy, theatrical kind of faux-symbolic act my friends dream up all the time. Sometimes when we eat dinner as a group, we go around the table and say our favourite thing about the day. We clap for one another’s potluck dishes, or driving stints on long car trips. At last I tossed my rock and yelled Bad mental health! The other three whooped and cheered. It felt like a naff team-building exercise, but it was oddly cathartic. That’s it, said a friend as we walked back to the carpark. You’re cured. We laughed and laughed. This was in 2015, before last year’s episode; at the time, I was perfectly healthy. But I was under no illusion, as I hurled a rock the size of my fist into the white-rushing water, that I was divesting myself of the complex bundle of neurological, genetic, environmental and personality factors that, every so often, causes me to unravel.

To conceive of depression as Ophelia is a delusion borne of privilege

When I read an article in a major daily newspaper suggesting depression is “less a treatable pathology than a spur to spiritual discovery,” I’m struck by the recklessly out-of-touch attitude and dismissiveness of literal decades’ worth of research. How one treats their mental illness is a highly personal decision, but one best informed by medical advice and the patient’s individual needs in relation to their diagnosis. To conceive of depression as Ophelia is a delusion borne of privilege, and only an affluent white woman could describe therapy as the “best fun ever […] Enjoyable, satisfying.” Romanticising it risks discouraging people from seeking the treatment they need, or from continuing their existing treatment. It undermines the severity and the danger of the illness. “Sorrow, at least the knowledge of it, adds depth. And of course beauty […] We know that huge proportions of poets and thinkers suffer depression. Perhaps they're the chosen – prescients, warning us that life is too short, too precious to tie to the treadmill.” What utter codswallop, I think. What irresponsible bullshit.

It must be nice to have the luxury of conceptualising clinical depression as a “melancholy hinterland” instead of a cognitive and emotional wasteland. To divide a circle into segments and pass it across a desk as a remedy for “spiritual malaise”. Must be nice to think of a sweet-faced, chlorotic woman slipping silently below the river’s surface.

0 notes

Text

My sister has been having joint pain recently. We all know what’s causing it. But until they get to see the geneticist, the gp won’t do anything. And they don’t know how long it will be till they see the geneticist, because instead of scheduling appointments like a normal fucking person, the geneticist just gives a time to show up, and if you can’t make that time, you have to wait months/years, for another appointment that might not even be possible to attend. What a stupid fucking system.

#they have ehlars-danlos#same as me#same as my dad#but we need a geneticist to give a proper diagnosis#in order for them to get the necessary treatment#I’m going to start fucking maiming#ehlars-danlos syndrome#eds#Australia#australian healthcare#the healthcare here is so shit at meeting patients needs#it’s unreal how difficult it is to navigate#no wonder so many people give up

0 notes

Text

Jacob Elordi | Workout | DOGPOUND gym.

#jacob elordi#dogpound gym#workout#fitness#dogpound#physical training#training session#training#men fitness#australian actor#actor#healthcare#health#jacob elordi gifs#euphoria: jacob elordi#euphoria: nate jacobs#nate jacobs#men#beautiful men#man#my gifs#mine: gifs#gifs: mine#gifset#*gifs

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

ending up with a crowd sourced cunt seems like the only feasible way of me every affording that shit

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Australian Medical Coding Certification Course in Idukki

Who is a Medical Coder ?

A Medical Coder, often known as a clinical coder, is a health information management specialist who works in a public or private hospital. Medical coders convert information from patient files into alphanumeric codes for convenient storage and retrieval. The codes can be gathered and analysed for research purposes. They also assist hospitals in staying organised and maintaining confidentiality rules when billing patients and processing public and private health insurance claims.

Roles and Responsibilities of a Medical Coder

1. Examining patient medical records for diagnoses and procedures

2. Clarifying ambiguous or conflicting information on medical records with visiting nurses or doctors

3. Determining which diagnoses and procedures meet medical coding requirements

4. Coding relevant diagnoses and procedures using a recognized medical coding system

5. Checking code sets for accuracy

6. Mentoring junior medical coders

7. Making suggestions for how to improve clinical documentation practices

8. Helping with medical records audits as needed

Transorze Solutions is a leading provider of medical coding and billing training in Australia, accredited by the Australian Medical Coding Training Institute (AMCTI). Our programmes are designed to provide you with the skills, knowledge, and confidence you need to succeed as a medical coding and billing professional. Our courses include medical coding fundamentals such as diagnosis and procedure coding, ICD-10 and CPT-4 coding, medical terminology and anatomy, and medical coding and billing principles. Our educators are skilled medical coding and billing specialists who can offer sound advice and direction. We also provide extra tools, such as online lectures and practice exams, to assist you in developing the skills required for success in the medical coding and billing sector.

#australian medical coding#medicaljobs#healthcare careers#medicalcareers#medical coding#transorzesolutions#medicalcodingtraining

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease."

Given the rising importance of the medical profession today, Medical Transcription is one of the most common words that has gained attention in the recent period. Join Transorze Solutions

#medical coding#health professionals#doctors#medical scribing#healthcare#medical transcription#nursing#australian medical coding#jobs#career#courses

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Australian Medical Coding Certification Courses in Nagercoil

AUSTRALIAN MEDICAL CODING

Australian Medical Coding is the method of classifying medical operations and services using a set of codes in order to bill patients' medical insurance plans and other payers. Medical coders only use codes that are appropriate for the Australian healthcare system. These codes are used to specify the medical operation or service, its price, and the applicable insurance coverage.

Australian medical coding certification courses are useful because they give students a comprehensive understanding of medical coding methods and jargon. In order to submit payments to health insurance providers, learners must master accurate coding, an additional skill taught in the courses. For people seeking employment in the field of medical coding, a certification programme can help improve job chances and earning possibilities.

Transorze is an ISO 9001:2015 certified company for delivering high quality “Healthcare BPO” training and placement services, totally dedicated in providing the services of Medical Transcription Training,Medical Coding Training , Medical Scribing Training, ,Digital Marketing Training.

Contact details

Phone no: +919495833319

E Mail:[email protected]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Certified Clinical Hypnotherapist#hypnosis#Hypnotherapy Training Centre#Best Hypnotherapy Course In Australia#Best Hypnotherapy Training In Australia#Clinical Hypnosis Training Australia#Hypnotherapy Training Australia#Institute Of Clinical Hypnotherapy#Training Center For Hypnotherapist#Australian Institute Of Hypnotherapy#Accredited Hypnotherapy Training#Become A Certified Clinical Hypnotherapist#hypnotherapist#australian institute of hypnotherapy#myperthhypnotherapyclinic#Australia’s Best Hypnotherapy Training#Training Centre#Diploma in hypnotherapy#Therapeutic#healthcare#health & fitness#mental fitness#Hypnotherapycoaching#Hypnotherapypractitioner#Hypnotherapymasterpractitioner#lifecoach#success#happiness#personaldevelopment#businessdevelopment

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

australian culture has been very influenced by the many many italian and greek people who’ve lived here for generations, which i feel is a part of why the concept of people resenting feeding their guests is such a What The Fuck moment for me

#also italians being a cornerstone of our culture is something australia and america have in common! yeehaw!#i think thats neat#i was gonna add that i think the only ppl who'd disagree with me on this point is Posh Australians (a nasty breed of people)#but it occured to me: my rich friend's parents still allowed me food at their house!#i ate their mango ice blocks!#man even the assholes in our country got nothing on this nonsense#have you no fucking manners#at least give 'em snacks >:(#some people buy boxes of little chip packets for their kid's friends#anyways come to australia: you will get fed and you will get healthcare#....also our economy has been fucky the last couple years so Bring Money

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

every time you successfully submit an assignment at the last minute it increases your self-confidence in re: completing assignments at the last minute and therefore increases the total incidences in which you; you guessed it: complete assignments at the last minute. ‘tis but another instance of last minute hyperfocused glory. this one too shall go on the hall of fame. i really gotta start medicating my adhd. oh well.

#i am currently not medicating my adhd#owing to the fact that i cannot medicate my adhd#because the only healthcare professionals who can legally medicate adhd are psychiatrists#and guess which group of professionals collectively decided theyre no longer taking adhd referrals#thats right#psychiatrists#okay mack to my coffee refueling#after this assignment imma fught the australian board of psychiatry with my bare hands

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Study Abroad & Live There Forever? Top 10 PR Paradises & Pro-Tips for Students! Unlock a world of opportunity with Permanent Residency after graduation. ️ Get details on Canada, Australia, Europe & more!

#uglyandtraveling#travel around the world#travel vlog#travel#travel channel#traveling vlog#travel blogger#ugly & traveling#ugly and traveling#travel backpack#Australian PR for international students#benefits of permanent residency#Canada PR for students#citizenship eligibility for international students#citizenship test for PR#connect with professionals abroad#cost of permanent residency#Denmark PR for international students#documentation for PR application#education with PR#educational consultancies for PR#expat communities for PR#factors to consider for PR destination#Germany PR for international students#Graduate Route visa#healthcare with PR#immigration consultant for PR#immigration news for PR#immigration updates for PR#international student organizations

0 notes

Text

Jacob Elordi | Workout time at DOGPOUND gym.

#jacob elordi#dogpound#dogpound gym#workout#fitness#physical training#training session#training#australian actor#actor#jacob elordi gifs#euphoria: jacob elordi#euphoria: nate jacobs#nate jacobs#mens health magazine#men fitness#health#healthcare#sport#man#beautiful men#men#mine: gifs#gifs: mine#edits: gifs#gifset#*gifs#*gifset

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leadership in Nursing!

Our client is looking for an experienced Nurse Manager to lead their team in Sydney, NSW. Drive excellence in patient care and foster a supportive nursing team.

0 notes

Text

#Medical Scrubs#Medical Scrubs in Australia#scrubs#healthcare scrubs#pediatric scrubs\#Australian Medical Scrubs

0 notes

Text

The foundation of the healthcare sector is medical coding, which provides the vital information required to guarantee payment for the services rendered. Join Transorze Solutions

#medical coding#health professionals#aapc#icd10#doctors#healthcare#nursing#medical scribing#medical transcription#australian medical coding

3 notes

·

View notes