#Adeimantus

Text

"The Republic: Plato's Timeless Exploration of Justice, Politics, and the Philosopher's Quest"

"The Republic," translated by Benjamin Jowett, stands as a timeless cornerstone in the philosophical canon, an intellectual odyssey that navigates the intricate landscapes of justice, politics, and the philosopher's pursuit of truth. Penned by Plato in the 4th century BCE, this Socratic dialogue remains a foundational work in political philosophy, ethics, and metaphysics. Jowett's translation, undertaken in the 19th century, preserves the essence of Plato's probing inquiries and dialectical brilliance, allowing readers to engage with the profound ideas that continue to shape the foundations of Western thought.

Plato's magnum opus unfolds as a series of dialogues, primarily led by Socrates, engaging with various interlocutors. The central exploration revolves around the question of justice, which becomes a metaphorical vessel for the examination of the ideal state, the role of individuals within society, and the nature of knowledge itself. The allegory of the cave, the tripartite division of the soul, and the philosopher-king are just a few facets of this multifaceted work that have reverberated through the corridors of academia for centuries.

The dialogue begins with an inquiry into the nature of justice as Socrates engages with characters like Thrasymachus, Glaucon, and Adeimantus. The discourse takes a dramatic turn as Plato introduces the allegory of the cave, an enduring metaphor for the journey from ignorance to enlightenment. This vivid imagery captures the transformative power of education and the philosopher's duty to ascend from the shadows of ignorance into the illuminating realm of true knowledge.

"The Republic" also ventures into the construction of an ideal state, led by philosopher-kings who possess both intellectual acumen and a commitment to the common good. Plato's vision challenges conventional notions of governance and explores the intricacies of a society governed by wisdom rather than mere political expediency. The dialogue delves into the organization of classes, the role of education, and the philosopher's ability to perceive the ultimate Form of the Good.

Benjamin Jowett's translation captures the nuances of Plato's intricate prose while maintaining accessibility for modern readers. His careful rendering of Socratic dialogues preserves the conversational tone and intellectual rigor that characterize the original work. Jowett's translation, though dated, remains widely used and respected, emphasizing the enduring appeal and significance of "The Republic" across generations.

"The Republic" is not merely an exploration of political theory; it is a profound meditation on the human condition. Plato's insights into the nature of knowledge, the complexities of justice, and the philosopher's role in society transcend the historical and cultural contexts in which they were conceived. The work prompts readers to question the foundations of their beliefs, to examine the societal structures they inhabit, and to consider the eternal pursuit of wisdom as a guiding principle.

In conclusion, "The Republic" by Plato, in Benjamin Jowett's translation, is a philosophical masterpiece that continues to shape the intellectual landscape. Its profound inquiries into justice, governance, and the nature of reality invite readers to embark on a philosophical journey that transcends time. The enduring relevance of Plato's ideas, coupled with Jowett's insightful translation, ensures that "The Republic" remains an indispensable text for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the complexities of human existence and the perennial quest for a just society.

Plato's "The Republic" is available in Amazon in paperback 16.99$ and hardcover 24.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 471

Language: English

Rating: 10/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Plato#The Republic#Socratic dialogue#Benjamin Jowett#Political philosophy#Ethics#Metaphysics#Ideal state#Justice#Knowledge#Allegory of the cave#Tripartite division of the soul#Philosopher-king#Thrasymachus#Glaucon#Adeimantus#Education#Allegory#Ideal society#Common good#Organization of classes#Form of the Good#Intellectual acumen#Political expediency#Conversational tone#Intellectual rigor#Human condition#Philosophical journey#Wisdom#Historical context

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Republic: Plato's Timeless Exploration of Justice, Politics, and the Philosopher's Quest"

"The Republic," translated by Benjamin Jowett, stands as a timeless cornerstone in the philosophical canon, an intellectual odyssey that navigates the intricate landscapes of justice, politics, and the philosopher's pursuit of truth. Penned by Plato in the 4th century BCE, this Socratic dialogue remains a foundational work in political philosophy, ethics, and metaphysics. Jowett's translation, undertaken in the 19th century, preserves the essence of Plato's probing inquiries and dialectical brilliance, allowing readers to engage with the profound ideas that continue to shape the foundations of Western thought.

Plato's magnum opus unfolds as a series of dialogues, primarily led by Socrates, engaging with various interlocutors. The central exploration revolves around the question of justice, which becomes a metaphorical vessel for the examination of the ideal state, the role of individuals within society, and the nature of knowledge itself. The allegory of the cave, the tripartite division of the soul, and the philosopher-king are just a few facets of this multifaceted work that have reverberated through the corridors of academia for centuries.

The dialogue begins with an inquiry into the nature of justice as Socrates engages with characters like Thrasymachus, Glaucon, and Adeimantus. The discourse takes a dramatic turn as Plato introduces the allegory of the cave, an enduring metaphor for the journey from ignorance to enlightenment. This vivid imagery captures the transformative power of education and the philosopher's duty to ascend from the shadows of ignorance into the illuminating realm of true knowledge.

"The Republic" also ventures into the construction of an ideal state, led by philosopher-kings who possess both intellectual acumen and a commitment to the common good. Plato's vision challenges conventional notions of governance and explores the intricacies of a society governed by wisdom rather than mere political expediency. The dialogue delves into the organization of classes, the role of education, and the philosopher's ability to perceive the ultimate Form of the Good.

Benjamin Jowett's translation captures the nuances of Plato's intricate prose while maintaining accessibility for modern readers. His careful rendering of Socratic dialogues preserves the conversational tone and intellectual rigor that characterize the original work. Jowett's translation, though dated, remains widely used and respected, emphasizing the enduring appeal and significance of "The Republic" across generations.

"The Republic" is not merely an exploration of political theory; it is a profound meditation on the human condition. Plato's insights into the nature of knowledge, the complexities of justice, and the philosopher's role in society transcend the historical and cultural contexts in which they were conceived. The work prompts readers to question the foundations of their beliefs, to examine the societal structures they inhabit, and to consider the eternal pursuit of wisdom as a guiding principle.

In conclusion, "The Republic" by Plato, in Benjamin Jowett's translation, is a philosophical masterpiece that continues to shape the intellectual landscape. Its profound inquiries into justice, governance, and the nature of reality invite readers to embark on a philosophical journey that transcends time. The enduring relevance of Plato's ideas, coupled with Jowett's insightful translation, ensures that "The Republic" remains an indispensable text for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the complexities of human existence and the perennial quest for a just society.

Plato's "The Republic" is available in Amazon in paperback 16.99$ and hardcover 24.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 471

Language: English

Rating: 10/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Plato#The Republic#Socratic dialogue#Benjamin Jowett#Political philosophy#Ethics#Metaphysics#Ideal state#Justice#Knowledge#Allegory of the cave#Tripartite division of the soul#Philosopher-king#Thrasymachus#Glaucon#Adeimantus#Education#Allegory#Ideal society#Common good#Organization of classes#Form of the Good#Intellectual acumen#Political expediency#Conversational tone#Intellectual rigor#Human condition#Philosophical journey#Wisdom#Historical context

0 notes

Text

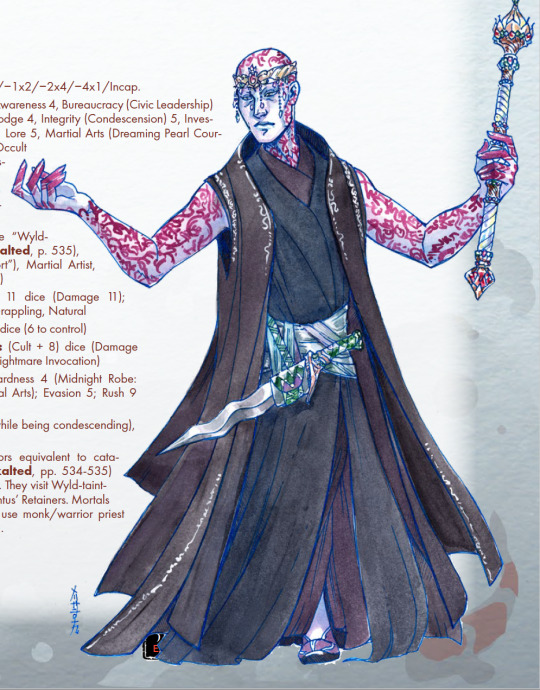

Beginning Chapter 2 of Adversaries of the Righteous for Exalted with a new thread. Chapter two covers "strange folk" so it's the catchall chapter for everyone who doesn't fit the category of mortal, spirit, or Exalt. First up is Adeimantus, the Fair Folk custodian of the perfect city of Beimeni-Ta. His city was lost to the Wyld and exists only as figments and illusions, until it's king inflicts it upon Creation, instantiating the city through dreams and drawing mortals in to be subjects in his utopia.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE RING OF POWER

Zach Reynolds

August 31, 2009

Phil 1301

Homework 1

Benefits of Being Unjust

In Book II of Plato’s Republic, Glaucon and Adeimantus put forth the theory that the life of an unjust person is better than the life of a just person because it is more rewarding in order to bait Socrates into arguing with them in defense of justice. They show Socrates a cynical view of justice and injustice that they claim to have found is common among the people. They develop their point in a number of ways: by telling the story of the shepherd boy, by comparing the theoretical lives of an absolutely corrupt, unjust man and that of an absolutely just man, by arguing that the gods can be persuaded to absolve and favor an unjust man through ritual and sacrifice, and by criticizing those who do preach justice for doing so only for the rewards.

The story of the shepherd boy tells of a shepherd who discovers a magic ring that grants him the ability to turn invisible at will. The shepherd boy discovers that with this power he can get away with doing injustice to anybody, and using his power he murders the King, takes his wife, and takes over the kingdom. According to Glaucon, who tells this story, even if there were two rings, one falling into the hands of a just person, and the other into the hands of an unjust person, that the outcome would be the same – the just person would not act any differently than the unjust person. His reasoning is based on his claim that it is always more advantageous to be unjust, and that the only reason why so many uphold the code of justice in the first place is because they are too weak to do injustice to others and get away with it, and because they fear suffering injustice onto themselves by others, and thus are using justice as a shield to hide behind. However, with the power to turn invisible, and thus do as many unjust deeds as one wants without facing the consequences for them, he argues that only an absolute fool would not take advantage of his newly discovered powers.

The second argument that Glaucon puts forth is the theoretical separation made between a completely just man, and a completely unjust man. In his demonstration, Glaucon argues that the unjust man would be a clever craftsman who would use guile to gain wealth and power through unjust means, while at the same time creating a false public image so that he appears to be just to everyone who knows him. He would enjoy the status of having a good reputation by pretending to be just, and also great wealth by participating in unscrupulous acts. Furthermore, Glaucon argues that even the gods would fall for the unjust man’s charade, or at any rate forgive him for it, because the Greek gods are easily won over through sacrifice and ritual. The just man, meanwhile, would make no attempts to create a good reputation for himself, and in fact Glaucon determines that it is absolutely necessary to strip the just man of everything but his justice in order to prove that justice alone is not enough to make the man’s life better than the unjust man’s. So, the just man does good, but he is not believed to be good. He is poor, has a bad reputation, and likely to be tortured and punished as if he were a criminal. Since he cannot afford to make adequate sacrifices to the gods, Glaucon argues that even they would favor the unjust man, and clearly the unjust man has the better life in this scenario, but it appears that he would be rewarded with a better afterlife also.

After making his separation, Glaucon’s brother, Adeimantus pipes in, saying that even those who teach justice teach it only for the rewards it brings. He uses the example of a father and his sons, claiming that even when the father tells his sons of justice, he praises not justice itself, but the rewards that justice brings: good reputation, honor, public office, marriage, wealth, etc. He seems to be arguing that nobody is just for the sake of simple justice, rather they act just for the selfish reason that they want to reap the benefits of the rewards that appearing to be just brings, not unlike the crook theorized in Glaucon’s argument. He also further elaborates on the proposition that the gods are easily swayed to favor those who are willing to spend money in order to appear pious, so that those who are unjust can escape punishment in their lives currently as well as in their afterlives in Hades simply by spending a fraction of the fruits of their injustices on sacrifices, rituals, and prayers.

Together, Glaucon and his brother Adeimantus paint a cynical caricature of reality in which justice is a farce, and all people really would rather behave unjustly because it is always to their advantage to do so as long as they can weasel out of the consequences. Though, of course, they do not necessarily agree with the arguments that they have put forth, it is only to elicit a reaction from Socrates that they do so. However, they face him with a daunting task, as from a materialistic viewpoint, it does appear that the life of the unjust person will always be better than that of the just person, and so it is up to Socrates to persuade the two brothers that the spiritual consequences are so great as to render all the material rewards of being unjust obsolete.

0 notes

Text

Socrates should come back from the dead: my thoughts on Democracy.

This blog is for our Philosophical Anthropology's thought piece.

I stumbled across a certain video on youtube during election season's campaign months. Out of curiosity, I watched it and ended with a new found perspective on Democracy.

youtube

I never thought of democracy beyond its surface level because I'm not really super smart in terms of politics, so having this video on my youtube recommendations by chance was a nice way to discover something new to learn or to re-learn.

The video discussed Socrates' views on democracy. I think he didn't really hate democracy per se, only criticized it because he saw faults in this system. In a conversation he had with Adeimantus that was documented by Plato, he brings up a scenario wherein he compared society to a ship. He argued (lectured, more so) if you were heading out on a journey in the vast sea, which group of people would you want deciding to take charge of the vessel? Just anyone or a group of people knowledgeable about seafaring? In which Adeimantus replied with “the latter.” Socrates rebuts with, so then why do we keep thinking that any old person should be fit to judge and choose who will rule a country? He had opened this conversation in an attempt to show the flaws of democracy.

Socrates points that voting is a skill and not a random intuition and like any skill—needs to be taught systematically. He claims that letting just anyone vote without education supporting their choices is as irresponsible as letting them in charge of a trireme sailing to Samos in a frenzied storm. It's not that Socrates believed that only a few can vote, though he infers that the only ones who be let near a vote are people who think of issues deeply and rationally.

Upon hearing Socrates' take away about democracy, I've came to realize that he has a point and that I kind of agree.

It's a good point that the only ones who should vote are people that are concerned of the country's issues and well-being because that way a nation can have a leader who wants to help. Don't get me wrong, I'm all for everyone having the right to vote for someone they want but like Socrates' point—have you thought of your vote rationally? Did wisdom came with your choices?

Sometimes I wonder, when will the people think of who the country needs instead of who they want? These days, it just seems like the people only vote for the sake of winning and not because they care at all.

What would Socrates' say or think if he sees what democracy has evolved to? Will he be shocked? Give a lecture like what he did with Adeimantus? Point out the flaws?

Sometimes I think Socrates should come back from the dead—but I doubt anyone today would listen, I bet that he will be forced to take hemlock again.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Exalted 3e Villain Analysis

When I was first going through the various Adversaries of the Righteous, I skipped right past Adeimantus, because I’m shallow. His art just isn’t evocative. But ho boy! Beneath that pale, bland exterior lurks a villain worthy of an entire campaign. So let’s talk about that.

Adeimantus is the ruler of a utopian City from the Shogunate named Beimeni-Ta. A city which was consumed by the Wyld ages ago. It now creeps into Creation like an infection transforming cities and slums into itself.

What a great freaking idea, wow. The sidewalks the towers, the people all transform into echoes of a golden age lost to time. Can’t you just see the brick back alley suddenly becoming a marvelous marble tunnel? The building torn halfway between one style and material and the next? The crowds of excited peasants waiting for their shacks to complete their transformation into mansions? Now that’s a threat! How do you even deal with something like that? Do you burn down the infected part of your city to keep it from spreading? Do you jail the new citizens to stop the from singing the praises of utopia, and converting more people to their cause? Or do you go after the Raksha that’s behind it all?

What I like most about Adeimantus is that he’s totally on the up and up, at least in my interpretation. He’s not doing this because he wants to eat every baby in Creation. He genuinely wants everyone in the world to live in his perfect city. So much in fact that he has a charm that not only changes the city to match the desires of an individual, but he himself changes to match that desire.

After the players have defeated Adeimantus and sent his city back to the mists: “That’s alright, we’ll start over as many times as you need. This is all for you.”

Which brings another terrifying aspect of Adeimantus into view. When he vanishes, so too does the city, and all of it’s people. Any buildings and individuals changed by Beimeni-Ta get whisked away to the Wyld, even victory can mean that a entire slice of a city is amputated. Spooky.

As far as a combatant, meh. If you’re using Adeimantus to beat people down, you’re doing it wrong. Although he does have a knife that can make you ugly to anyone who can read, which is fun. His main power in combat comes from his ability to summon battle groups of his followers to attack the pcs. Plus ya gotta involve the city itself in any combat you do. Potholes open up beneath your feet, shingles slide off the roofs onto your head, and other such irritants. Maybe give the city it’s own initiative, and stat block, why not?

His real strength comes from his ability to manipulate intimacies. Not only can he instill them in people through their dreams, but he can also make you disregard any that make you oppose him. Very fun, and could be interesting if you have players who are very dedicated to rp. Otherwise think of all the NPCs you can target, and turn against the players. Now that’s high drama. Solars want to live in Utopia too right?

Especially since as I said before Adeimantus is a chill dude. He doesn’t want to resort to violence, he rules a utopia, and wants to share it’s bounty with the world. Of course his Utopia ends up being pure madness when it returns to the Wyld, but no one seems to be dissatisfied.

So I’ve gushed on about this beautiful bald man long enough. What are some ways you can use him in a game?

1. A world saving device was once held in Beimeni-Ta, and it’s needed once more. Do you: look for a city infected by Beimeni-Ta. Crusade into the wild to reclaim the lost city. Or maybe infect a nearby city, long enough for the vaults of Beimeni-Ta to manifest.

2. Beimeni-Ta begins to arise within Great Forks. How does the city of a thousand gods react to such an intrusion? Is the draw of Utopia enough to tempt even a deity? Or do they hold firm as more and more of their followers join the cult of Adeimantus?

3. Every Winter Adeimantus visits a struggling village in the north, and provides them with supplies needed to survive the harsh winter. What scheme is he up to? It’s been generations since he started doing this, and no apparent harm has been done. The villages are convinced he’s a benevolent god of winter, how will they react when the players try to destroy him before he can corrupt their village?

4. Beimeni-Ta is ruled not only by Adeimantus, but also a Senate of Demons. So this Fair Folk, has an alliance with demons, as well as a permanent city in the Wyld. There’s something deeply interesting going on with Adeimantus. In his Stat block it does say the Senators are Raksha too, but I much prefer him being a complete weirdo. But as for plot hooks. A city has already fully fallen to Beineni-Ta. Now there is only one thing left to do. Characters must introduce a bill to the demon senate which will revoke the city’s hold on creation, at least this part of it. Can the pcs, get it through sub-committees, and over come a filibuster lead by a second circle demon?

5. Burns 100 Poets is a monk of the Immaculate order who has thrice vanquished Adeimantus from creation. He carries the weight of the many poets he’s killed to keep Adeimantus from spreading his corruption. He is retired now nearly 200, and works day and night to craft the poems which could have been were it not for his diligence. He may hold valuable information in how to stop Beimeni-Ta from spreading. However this gentle poet of an old man may suggest methods the pcs would consider frightful.

Finally let’s talk about a campaign that has Adeimantus as it’s big bad.

I call this one: Lookshy, Rise of The Shogun.

The basic premise of it being Beimeni-Ta was a city during the Shogunate Era, a pretty important one. Reclaiming it would finally give The 7th Legion reason to accept a new individual as Shogun.

Act 1

The Players, Dragon-Blooded protectors of Lookshy are tasked with looking into strange happenings around the city. The marching band plays a song hundreds of years out of date, a new building appears seemingly out of nowhere. Things escalate when a section of the city’s rampart’s becomes infected with shiny new lightning ballista. Suddenly the General Staff is torn on how to deal with the situation. with some opting to let the infection spread to access Beimeni-Ta’s ancient resources, to others wanting to combat the plague before it’s too late. The group is forced to navigate this tenuous situation, while beating back Adeimantus’ growing cult, and corrupted gentes. Culminating in the final confrontation with Adeimantus, and a member of the general staff he’s corrupted. Adeimantus vanishes with his pawn defeated, and takes however much of Lookshy he’s corrupted away with him, back to the wild. The walls are breached, the city is in ruins, the army is divided, and things are looking dire. Were The Realm not crippled by The Scarlet Empresses’ disappearance, this would be the end.

Act 2

After a brief recovery clarity comes to the surviving populace of Lookshy. The Shogunate Bureaucracy has records detailing this Beimeni-Ta many of the afflicted citizens were rambling about. It was once a seat of power for the Shogunate a place of immense importance, that fell into the Wyld never to be seen again, until now. Most importantly it was the final resting place of The Imperial Seal. The stamp with which The Shogun made words on paper law. With it, a simple document can be stamped and a new Shogun can be appointed, the shogunate will live once more. If only Beimeni-Ta can be dragged back out of The Wyld. If only... we could find it.

No maps of Beimeni-Ti’s location survive, only records of military assignments. Letters for a general to withdraw from the defense of the city, a general by the name of Tepet...

With the only lead they have the players are sent under cover to The Realm to find what they can about Beimeni-Ta from it’s ancient defenders. There’s investigation, spy work, a heist. All of which ends in a social confrontation with Tepet’s ruling Council which presents them with an offer: fulfill their oath to the Shogunate, regain their honor by retaking Beimeni-Ta.

Act 3

The impossible has happened. The players have convinced Lookshy to break with tradition, and march on the Wyld. House Tepet has given their only legion to the cause. The two armies of the Shogunate unite like something unseen in anyone’s time, and march through the river lands towards the end of the world. It’s a long grueling march, through an untold number of kingdoms. The centuries of Lookshy’s political favors, and military threats fray with each border they cross. Threats seeks to divide them with armies and from within. The Lookshy soldiers see their Tepet allies as traitors, and the Tepet aren’t too fond of the scavengerland barbarians either. The players must use their genius to get their army through in one piece. Until they reach, the border marches.

Act 4

From here on it’s all out warfare. The players and their small army must reclaim creation step by step enduring every machination the Wyld can through at them, from raining lava, to forests of grass as tall as a warstrider, and as sharp as a blade. All until they lay siege to Beimeni-Ta. At last the jewel is within their sight. They just have to overcome Beimeni-Ta’s endless militia of maddened citizens, their 100 Demon Senate, and of course Adeimantus fully empowered by the wyld and Beimeni-Ta itself. Who can with but a look, a touch, who’s very presence beckons you to join him in Utopia, in oblivion.

And what are the rewards for such an epic journey? A brand new city to rule over? The title of Shogun, and resurrections of the shogunate? An arsenal of first age weapons from the shogunate’s richest city? Who’s to say what dreams await you in Beimeni-Ta?

Only Adeimantus knows.

Only Adeimantus can show you the way.

#ttrp#ttrpg campaign#exalted rpg#exalted#exalted essence#exalted 3e#campaign ideas#rp#rp ideas#rpg#onyx path#white wolf#lookshy#Adeimantus#adversaries of the righteous#plot hooks

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

I didn't know you did a pic of Hera seducing Zeus with Aphrodite belt! For shame, I'd have loved to see it! And how can Plato see it as bad example, they're married and a woman has to sue what she's got to one up her man lol also, I'm all for them having sex, keeps Zeus from others.

Do you mean this one? In Plato's eyes the gods were faultless and endowed with natural virtue. In the dialogue of The Republic he lets Glaucon and Adeimantus come to the conclusion that all stories ascribing various wrongdoings to the gods are not true and shouldn't be taught to the youth. The problem with that scene in The Iliad with Zeus and Hera wasn't that they had sex, the problem was that Zeus was shown to have no self-control and let himself be fooled. Self-control was central to the conceptions of masculinity in Classical Greece, and that passage wouldn't exactly set a good example for the young men.

“Or to hear how Zeus lightly forgot all the designs which he devised, watching while the other gods slept, because of the excitement of his passions, and was so overcome by the sight of Hera that he is not even willing to go to their chamber, but wants to lie with her there on the ground and says that he is possessed by a fiercer desire than when they first consorted with one another, ‘Deceiving their dear parents’".

Plato, The Republic, translated by Paul Shorey.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing that I don’t think enough people know is that “Plato” might be a wrestling nickname meaning “Broad,” like broad chest, and we that might not actually know his given name—but we do know the names of his brothers Adeimantus and Glaucon, and his sister Potone!

So it’s like all of Western Philosophy is footnotes to the work of “the Rock,” and 2400 years from now, people know that “the Rock” had siblings named Dave, Bob, and Susan, but have no idea that he himself was named Dwayne. They cite “the Rock” with utmost seriousness, and without irony.

#it just makes me happy#classics#plato#his name might have been#aristocles#but that literally just means ‘best in reputation’#and might have been made up by an unreliable biographer#*cough* Diogenes Laertius *cough*

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Het leven van Plato

Plato (Πλάτο) is geboren rond ca. v. Chr. 427 in Athene en is in 347 v. Chr in dezelfde stad gestorven. Hij werd 84 jaar oud. Plato was een zeer bekende Griekse filosoof en schrijver. Zo heeft hij heel veel boeken geschreven over allerlei verschillende onderwerpen, Zo beschreef hij In de Phaedo met zeer veel detail de dood van Socrates.

Plato had 2 broers: Glaucon & Adeimantus. Hij had ook nog 1 zus, zij heette Potone. Plato is de zoon van Ariston en Perictione, zijn vader stierf echter al toen de kleine Plato twee jaar oud was. In de tijd dat Ariston overleed was het door de Atheense wet verboden voor vrouwen om juridisch zelfstandig te zijn, waardoor Perictione werd uitgehuwelijkt aan Pyrilampes, Perictione’s Neef. Dit zouden wij nu raar vinden, maar vroeger was dit heel normaal.

Plato wordt door vele een van de meest invloedrijke denkers in de westerse filosofie genoemd, zo heeft hij in zijn leven ook een school geopend, die de Atheense Akademia heette, dit was het eerste instituut van het westen.

(op het plaatje kan je de Atheense Academie zien)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

READING THE REPUBLIC

Why does every teacher from an introductory philosophy class to one about political theory seem to be obsessed with assigning Plato’s Republic? If you glance thought the text, it seems to be better suited to a drama class, written as it is as a dialogue instead of the more traditional academic essay or treatise. However the Republic acts a good introductory text to so many subjects precisely because the characters of the text, through the course of their conversation, ask many of the same questions that subsequent thinkers will continue to ask and try to answer, questions that are the central inquiry of Western thought.

The Republic touches on questions regarding justice, what it means to be happy and lead a good life, the role of education in a society, what the ideal form of political government is, to what it means to have knowledge of something versus simply having an opinion. Plato was an educator and a philosopher, and reading the text can help teach the reader how philosophical inquiry can be embarked on, simply through having a conversation with your peers and asking questions about the world, and seeking an answer to them to with the goal of finding the truth.

What readers have taken from the text is myriad. By some, Plato has been read as providing an outline to a political society where power was given through individual merit, while others claim that the political society that Plato outlines is a totalitarian one, similar to Hitler’s Germany or Stalin’s Russia. This shows the importance the role you, the reader, have. How you interpret the text and the arguments of the characters gives the text its meaning.

As a result, the Republic can, in some ways, be analyzed as a drama or a novel. In some accounts it is said that Plato once did have aspirations of becoming a poet. According to those accounts, when Plato showed Socrates some of his works, Socrates asked him questions about every line of the text, and as a result Plato burned all his works and never wrote again. In reading the text as students then, we should channel Socrates’ annoying inquisitive spirit, and carefully read the text line by line.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Plato has a reputation of being an ambiguous author, especially to the modern reader, who is not familiar with the historical events and characters present in the text in the same way that Plato’s contemporary readers would have been. To navigate these ambiguities it is important to have a bit of a background of the historical settings that the Republic was written in.

Plato was born in 427 BC (that’s around 2500 years ago!) to an influential aristocratic family at the end of the Golden Age of Athens, an age of Athenian domination and prosperity which had begun in the early fifth century with Athens’ defeat of Persia. This Golden Age would come to an end with the commencement of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. Plato was born during the Peloponnesian War, and was around five years old when Athens entered into a truce with Sparta in 423 BC, called the Peace of Nicias. For some hopeful Athenians, this was a chance for Athens to rebuild its former empire and influence, free of the drain of warfare.

Unfortunately, that was not the case. Only eight years later in 415 BC, Athens’ decided to send a fleet of ships to Sicily, refered to as the Sicilian Expedition. As a result, the unthinkable happened. Athens’ fleet, which had made it a dominant naval power, was destroyed at Syracuse in 413 BC. By this point in Plato’s short lifetime (he was fourteen when the news of the failure of the Sicilian expedition broke), Athen’s had gone from being a dominant power to receiving a crippling blow in a an international conflict that it had entered into in a dominant position. Ten years later, when Plato was around twenty-four, the Peloponnesian War ended with Athen’s surrender.

The decline of Athens would have had a great part in molding Plato’s political concerns, and thoughts of reforming Athen’s to its former glory would have been heavy on his mind. While Plato was influenced by other philosophers, it is of course Socrates that had one of the greatest influences in his thinking. When Plato was twenty he started to join the other young aristocrats who hung around Socrates in the marketplace.

Some of his family members were already part of Socrate’s group, such as his uncle Charmides and his mother’s cousin Critias. These were the same relative’s of Plato who, at the end of the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC, would lead a group of conservatives to overthrow Athen’s democracy to rule as members of the Thirty Tyrants for nine corrupt and bloody months. Another infamous member of Socrates group was Alcibiades, who was the one to convince Athen’s to embark on the disastrous Sicilian Expedition, which lead to the destruction of Athen’s fleet.

So while, to Plato, Socrates represented the image of a philosopher who asked questions in the search for the truth, to the citizens of Athens Socrate’s probing questions, which he claimed to have no answer to, served only to undermine the city by questioning its traditions and established order. The democratic government which took power after the Thirty Tyrants was the one to sentence Socrates to death on the charge of corrupting the youth and, disbelieving in the gods of the city, introducing new gods into Athens. Socrates was sentenced to death and drank the hemlock in 399 BC, when Plato was twenty-eight years old.

Plato lived to be about eighty years old, but the first thirty years of his life were the most formative. The rest of his life would be spent doing what he admired most in Socrates – searching for knowledge. He became an educator in his own right, and founded the Academy, remembered historically as the first university.

This important period – the Peloponnesian War, the rise of the Thirty, their downfall to the democracy, which would execute Socrates – casts a shadow on the dialogue of the Republic through its characters, whose fates were embroiled in its events. The dialogue was set during the Peace of Nicias, meaning that many of the events that lead to the decline of Athens had not yet come to pass, and neither had the Thirty come into power – but they would have been fresh on the minds of Plato’s readers, who knew the future that was to come.

Many of the characters would be dead by the time the Republic was written. Socrates was sentenced to death for the same philosophizing he characterized in the Republic, Cephalus (the old man who opened his home to the visitors) would have his family fortune seized by the Thirty, who were relatives of the brothers Glaucon and Adeimantus. Polemarchus would also be executed by the Thirty, and his brother Lysias and father Cephalus would be sent into exile in the Piraeus, which during the time of the Thirty acted as the center of democratic opposition, and would be recognizable to us as the setting of the Republic.

For me this knowledge makes the dialogue that much more poignant. It is almost as if Plato is saying “Look, pay attention! What may seem like an idle conversation to pass the time, asking grand questions about justice and the good life, will lead to the death of these men.” It is a warning to those that think these questions aren’t important, and what should happen if we decide to stop the pursuit of knowledge regarding the truth. It is my belief that it is this message that the Republic has preserved through its study by generations of students.

BOOK I

Cephalus (328b-331d)

The Question is Introduced – What is Justice?

Techne (332e)

Types of human government (338d)

Violence of tyrants (344b-c)

The burden/difficulty of rule (345e-346a)

Comparison between the city and the individual (352a)

Proper task of things (352d-353a)

Polemarchus (331d-336a)

Thrasymachus (336b-354b)

The old order, introduction of Cephalus

The first definition of justice to be introduced is through an old man named Cephalus, who is the father of Polemarchus. In ancient Greek, Cephalus means “head”, which he could be named because he is the head of the family. He is happy to see Socrates, and partly insults him by saying to him that, due to his old age, his desire for conversation has grown so he wishes that Socrates would visit him more often to talk. Either intentionally or not, Cephalus has thus regaling the philosophical conversations to which Socrates has devoted his life to idle talk to pass the time in old age.

Cephalus is a “metic” meaning is not a citizen of Athens, despite his monetary wealth. It is here, where they sit down with Cephalus that the rest of the dialogue of the Republic is going to be held.

Cephalus begins the conversation by looking back on his life, and states that while old age has given him freedom from the sex and money that ruled his younger years, in his old age he has also began to wonder if he lived a just life. Cephalus wonders, if when he dies, he will go to the afterlife peacefully. It is Cephalus who poses the question of justice, due to the fact that he is approaching the end of his life and is worried about the judgement of the gods.

We can think of justice loosely as “acting in a right way” – for an example in a way that the gods would approve of in the afterlife. The English word “justice” is how the word “dikaiosune” found in the original Greek text is translated. Dikaiosune refers to behaviour that is regular and predictable, such as law-abiding behaviour, in contexts that involve behaviour towards other people. This stands in opposition to virtues like courage and honesty, which can exist in the absence of other people.

Pause here, my dear reader, to think about what justice would look like to you. How should we treat other people?

Say you think that justice is acting towards others as you would like to be treated. If this is your conception of justice, then are there circumstances where acting according to justice is made easier? What about harder?

Think about your conception of justice and argue against it. Some standards you should see if your conception of justice can meet are (1) if it is universal, meaning you should ask if it guides everyone’s actions in the same way, no matter the circumstances (2) if it can be taught, and if so, how.

He then continues to say that the money he has is now good because he can offer sacrifices to the gods and pay back his debts to those he owns them to, and does not have to commit injustices because of a lack of money.

From this statement, Socrates asks him if that is what he thinks justice is “speaking the truth and paying back what one has borrowed” (331d).

Socrates has an argument against this definition of justice. He asks – what about if you borrowed a weapon from a friend that was not mentally sane? Under this definition of justice, which says that you must pay your debts and return what you have borrowed, you must give the weapon to this friend, even if he could hurt himself or someone else with it. This cannot be justice.

Here, Socrates has pointed out that Cephalus’ definition is deficient because it only describes an instance of what actions can be seen as just, without really telling us what justice is. There’s a famous story that once, Plato defined man to be “a featherless biped”, only to have the philosopher Diogenes run into his villa holding a plucked chicken, exclaiming “Behold, a man!”. Socrates has done much the same to Cephalus, and through his counter example made the point that merely describing what actions are just, does not explain why they are just.

Cephalus’ definition also does not give much guidance to those, like the sword lender in Socrates example, who do not have the ability to act according to it. Cephalus’ definition is one that is very much tailored to the position in life Cephalus is in, as an older person with money and few temptations, and has little to offer to those who are not in the same position. As Socrates says, it is a definition that outlines actions that are “sometimes just, sometimes unjust” (331c).

Cephalus agrees with Socrates, and admits that Socrates had made a good point against his definition of justice, but before he can hear Socrates’s argument he leaves the conversation, tasking his heir Polemarchus with continuing the debate on his behalf. With the exit of Cephalus, who will not return, tradition and the old order has left the conversation. This leaves the remaining characters – Socrates, Glaucon, Polemarchus, Thrasymichus and Adeimantus – to converse over a new definition of justice.

This is the primary topic of dialogue for the rest of Book I of the Republic. Similar to the conversation with Cephalus, a character tries to give a definition of justice, only to have Socrates come up with examples and arguments that show inconsistencies in the definition, such as how it is applied (as he did with Cephalus) or lead to a conclusion that is extreme (as he will later do with Thrasymichus).

Polemarchus, a dead man talking

Polemarchus is the next character to give a definition of justice. Polemarchus is a name that means “war lord”. Polemarchus is concerned with honor, and to him justice is a type of loyalty to your friends, to those that you identify as belonging to the same community as you. This is a very “us versus them” view, making it a view of justice that lends itself very well to international relations.

Prompted by Socrates, Polemarchus states that, like the art of medicine is to give “drugs, food and drink to bodies” and the art of cooking is to give “seasoning to meat”, the art of justice is “the one that gives benefits and harms to friends and enemies” or in other words “Justice is doing good to friends and harm to enemies” (332d).

This is a definition that is more general than the one Cephalus had provided, and therefore harder to disprove with just a simple counter example. To argue against it, Socrates will show that if this is truly the definition of justice, it will lead to unacceptable conclusions if applied.

Remember, to say something about justice is to say something about how we should treat other people, so in saying that we “should give others what they are due”, Polemarchus is saying that to act justly is to fulfill our social obligations to the people in our community and those outside of it.

If you were Socrates, how would you argue against this definition of justice? Keep in mind what acting according to Polemarchus’ definition would entail. In 332c, the word “craft” is a translation of the Greek word techne, which to those of Plato’s time would have the same connotations as the word “science” would have to us.

So when Socrates asks “what the craft we call justice gives”, he is asking what type of knowledge is needed in order to fulfill our social obligations to those in our community and those outside of it. By treating justice as a techne, Socrates requires that Polemarchus’ definition of justice require knowledge. Look back on Polemarchus’ definition – what type of knowledge is required to “do good to friends, and bad to enemies”?

Much of the diffuculty that Polemarchus’ definition faces is that Socrates treats the type of knowledge required by justice as a techne, or a skill. This sets justice to the same standard of knowledge as the skills that the term techne encompassed in Plato’s time, such as that of a medicine or navigation. These skills usually made up a persons occupation (such as doctor or ship captain), and therefore not only require abstract, theoretical knowledge but a way to apply that knowledge, and subsequently, teach it to others.

If we are to say we have knowledge of justice, of how we should treat others, then Socrates and Plato maintain this is the standard we must aim for in our search for justice. By having Polemarchus agree that justice is a skill or a craft, Socrates traps Polemarchus into having to show that there is a specific subject that is the sole domain of justice, in the same way that we have a defined view of the purpose of medicine or navigation. So if justice is something that guides the activity of “doing good to friends and bad to enemies” is there a specific field of knowledge that belongs to justice?

Socrates argument is to show that, if we are to follow Polemarchus’ definition of justice, that no, there is not. This is because the skill to do good or bad to someone is already accounted for by other crafts. If, as Polemarchus claims, the domain of justice is in matters of war’s and alliances (332e) and in peace-time, that of contracts,

Socrates asks Polemarchus how a person can determine who their friends are. People make mistakes, so can’t a person then think someone who is their friend, whom they consider to be good, be in fact their enemy? Since this is obviously the case, and people often mistake their enemy for their friend, Polemarchus’ definition of justice can mean that it is just to treat good men unjustly. This seems like a bad definition of justice.

In response to this, Polemarchus amends his definition of justice to state that “it is just to do good to the friend, if he is good, and harm to the enemy, if he is bad” (335a). Socrates is quick in his rebuttal, and asks if it is ever just for a just man to harm anyone? When you harm a horse or a dog they become worse. So therefore, cannot it also be said that the same is true of a human being, and in respect to human virtue a person would become worse? If human virtue must be a part of justice, just as “musicians cannot make men unmusical through music”, it does not make sense that a just man can make others unjust through justice. That is the work of his opposite, an unjust man.

Through these arguments Socrates has silenced Polemarchus, but we shall see later on that his definition of justice will make a reappearance. The best city is one that is peaceful, but that might not be so between the relations of states, meaning that a warrior force that protects the polis will be needed. The fact that this definition makes a reappearance is not a surprise, since is not a sense of community central to the citizenship that makes up political life? Can a political society even survive without a sense of what it is, and what it is not?

Thrasymachus, Socrates’s evil twin

The next to take up the challenge of giving a definition of justice is Thrasymachus, who has been sitting eagerly through Socrates’s conversation with Polemarchus, barely restrained by those around him from speaking. He is describes “hunched up like a wild beast” and once Socrates finishes his conversation with Polemarchus, he flings himself at Socrates and demands that he give a definition of justice himself instead of just refuting the definitions of others. This outburst startles Socrates so much that he thinks to himself that “he was frightened when he heard [Thrasymachus], and, looking at him, he was frightened” (336d).

But Socrates had noticed Thrasymachus’ agitation while he was speaking to Polemarchus and was ready to answer him. Socrates says that if he is making any mistake, it is not intentionally, since he would not stand in the way of someone looking for something as valuable as justice. At this response Thrasymachus exclaims in humor, and accuses Socrates of engaging in his “habitual irony” in not giving an answer. Thrasymachus is a sophist, who in ancient Greece would teach rhetoric for a fee. Philosophy was defined in contrast to sophistry, which was characterized by skepticism and a reputation for making anything look like the truth, while philosophy was the search for what was true and objective.

Thrasymachus gives his definition of justice, stating “the just is nothing but the advantage of the stronger” (338c). In other words, might is right.

Thrasymachus points out that every polity makes a distinction between the rulers and the ruled, and each ruling group, no matter the form of government, sets down the laws. “A democracy sets down democratic laws; a tyranny, tyrannical laws” (338e) for their own advantage and declare these laws to be what is just for the ruled, and punish their breaking as injustice. Justice is the rules of the ruling class, which they set to their benefit.

Socrates challenges Thrasymachus in a similar way to his challenge to Polemarchus. He asks Thrasymachus is if rulers can make mistakes, and therefore make laws that are disadvantageous and harmful to them. If it is so, which Thrasymachus agrees to be true, then the ruled are made to follow rules that are a disadvantage of the stronger. This shows a flaw in Thrasymachus’s thinking. Thrasymachus’s response to this challenge is that those who make mistakes are not true rulers, since they are not the stronger in having made their mistake. The true ruler acts on their own interest, as well as knowing what is in their own interest.

Socrates argues that an art is not made for the benefit of the practitioner but for the advantage of its use. Medicine does not consider the advantage of medicine, but of the body, and horsemanship does not consider the advantage of horsemanship, but of horses. Therefore, Socrates concludes, a ruler, in practicing the craft of ruling, considers not their own advantage but, instead, that of which is ruled (342e). Thrasymachus blows up again, and insults Socrates. He says that the relationship between the rulers and the ruled is like that of a shepherd and their sheep. The shepherd does not raise the sheep looking for the good, but for their own self-interest.

The value of Injustice

In giving his speech about shepherds and sheep, Thrasymacus makes some bold statements about the value of living a just life. He says that “the just man everywhere has less than the unjust man” and injustice is to one’s benefit if it is done on a larger scale, as a ruler, since no one will call it injustice. After all “for it is not because they fear doing unjust deeds, but because they fear suffering them, that those who blame injustice do so” (344c). The just is then what is profitable for the stronger, and the unjust is what is profitable and advantageous for oneself. Here, Thrasymachus has changed the topic of debate from the question of what justice is, to if a life lived according to justice is the best one.

Thrasymachus is claiming that perfect injustice is more profitable than perfect justice (348b). In response to this Socrates asks him if he thinks if justice is a virtue, and injustice is a vice. Thrasymacus agrees that justice is a virtue and injustice a vice, but adds that injustice is more profitable, and is good and prudent. Prompted by Socrates’s questions, Thrasymachus is also made to agree that the just man will be willing to only get the better of the unjust man, while the unjust man is willing to get the better of both those that are just and unjust. Put plainly, Socrates is making the point that the unjust are the sort of people who would take advantage of other people, both those who are just and unjust,

If, as Thrasymachus is also made to agree, those that are learned are not willing to get the better of those that are like them, but the unlearned are willing to get the better of both the learned and the unlearned, the just have been revealed themselves to be good and wise, while the unjust are unlearned and bad. It is at this point that Thrasymachus is made to blush, for he realizes that instead of defending justice as a virtue, he has been defending the unjust life, and those people who would take advantage of others.

Socrates’ second point is that even those that are involved in some unjust enterprise, such as thieves, would have to act justly towards one another in order to accomplish anything. It is injustice that produces factions and fighting among those factions, and justice that produces peace and friendship (351d). If the gods are just, the unjust man will also be an enemy of the gods.

But despite all this conversation, Socrates proclaims, the importance of this discussion is to determine the question of how one should live. The point of disagreement between Socrates and Thrasymachus is not only on what justice is, but if the just life is the best life (in being the most profitable).

Socrates goes on to say that each thing has a virtue in the work that it does. For example the purpose of an eye is to see, but if instead of being governed by virtue it was ruled by its vice, that is blindness, then its work would be done poorly. The same can be said of living, which is the work of the soul, so that a soul ruled by vice does not live well. Since justice is the virtue of the soul and injustice its vice, the just soul and the just man will live a good life, and the unjust one a bad one (353e). The just man will therefore be happy, which is profitable, while the unjust one will be wretched, which is not.

This conclusion seems to be an unsatisfactory one. It seems like Socrates did not really disprove Thrasymachus’s argument, more that Thrasymachus got frustrated and gave up. Glaucon and Adeimantus agree, and are not satisfied with this conclusion, as we will see in Book II.

The main point to take away from the debate around Thrasymachus’s definition of justice is that it hinges on what type of knowledge is necessary to rule. The central concession that Thrasymachus makes to Socrates is in saying that one needs knowledge in order to determine what is in ones self-interest. So if justice is self-interest, then justice requires knowledge. If the true ruler will act unjustly in order to pursue their own interests, justice, like all knowledge, is for the purpose of self-interest. By Thrasymachus’s view the strong are better of disregarding justice, and pursuing their own self-interests directly.

Why do we read Book I?

Having been introduced to the question of justice, and having been given three diverse accounts of how to define justice, we are left at the end of Book I with little answered. This leads many frustrated students to ask why we even need to read Book I? We will move on to Book II only to have Glaucon pose the same questions, mainly (1) what is justice, and (2) is the just life the good life – questions which, unlike in Book I, Socrates actually attempts to give an answer to.

This leaves many students tempted to skip Book I, but while tempting, I would not recommend it. The reason that Book I is still read in teaching the Republic is because it introduces many of the themes of the book, and in my opinion functions as a good primer to those who are unfamiliar with the Socratic method of philosophizing, asking questions and arguing. Plus, Book I sets important groundwork in the common ways that one may approach asking the question of what justice is, and the problems that those approaches will face.

While frustrating (which is in part the point, the search for the truth is not an easy thing!) the work of Book I is rewarding. As you will see, it is likely that you will return to Book I in your essay on the Republic in order to trace Socrates’ line of argument, since after Book I Socrates does not face much opposition in laying out his definition of justice.

#plato#the republic#reading notes#political science#political philosophy#some old notes i wrote for a tutoring session#political theory has my heart#if you ever want to discuss it#leave an ask!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Republic Book 3 &4

In book 3 Socrates keeps discussing the content of stories that can be told to the guardians, continuing to stories about heroes. The most important purpose of this class of stories is to inject the young guardians against a fear of death. In book 4 Adeimantus interrupts Socrates to point out that being a ruler sounds unpleasant. Since they cant have things that people think make them happy

1 note

·

View note

Text

19 Thargelion

Bendideia Festival

Bendidia or Bendideia was an ancient religious festival celebrated at Athens since 429 BC in honor of Bendis, a Thracian goddess whom the Greeks identified with Artemis.[1]

Bendideia, festival in honor of Bendis- processions. “Perhaps we do not know that the Bendidia intend to worship Artemis according to the Thracian usage and that this name, Bendis, is Thracian? Thus also the Theologian from Thrace (Orpheus) among the many names of the Goddess Selene refers to Her also the name of Bendis: ‘Plutonide and Euphrosine and mighty Bendis.’ As for the Panathenaic festival, I mean the Lesser, which come after the Bendidia, and had as reason for the feast Athena. Well, the one and the other are the daughters of Zeus, both are virgins, then you add that both are 'bearers of light’, although Bendis as the one who brings to light the invisible principles of nature, while Athena as the one who gives intellectual light to the souls .. and also as the one who dispels the darkness, whose presence prevents souls to see what is the divine reality and what is the human. Now, since these are the characteristic properties of both, it is clear that Bendis is the guardian of becoming and presides over the births of the principles that belong to the becoming …” (Proklos, In RP. I, 19).

Sacrifice to Menedeios. (Sacrificial Calendar of Erchia)

The nineteenth is always dedicated to purifications and apotropaic rites. “The traditional laws of the Athenians have attributed the eighteenth as well as the nineteenth to the lustral and apotropaic rituals, as told by Philochorus and <***>, both interpreters of the uses of their Ancestors. So, perhaps for this reason, Hesiod says that this day is sacred, and especially after noon, because this part of the day is suitable for the purification's…” (Scholia Erga, 810).[2]

Other times, Bendis is conflated with Persephone or Selene. These associations also have their similarities. Bendis’ ceremonies were indeed practiced at night, by Thracians and (after the Oracle of Dodona told them to) by Greeks as well. One such ceremony is mentioned as the setting for Plato’s Republic, and appears in other classical works. It is called the Bendidia.

Bendidia involved torchlight processions on horseback and revels under darkness, like those celebrated by other Thracian and Orphic deities like Sabazios and Dionysos. Bendis is sometimes accompanied, like Dionysos, by satyrs and maenads, or simply by athletes running toward Her temple.[3]

The Goddess Bendis:

A Thracian mother goddess. Bendis was often identified with the huntress goddess, Artemis and the moon goddess, Hecate. She is also the goddess of healing.

Bendis first appeared in Athens, during the Peloponnesian War, where she was Hellenised. An annual feast, Bendidea, was held in her honour. The geographer Strabo says that the rites and customs of the Bendidea are like those found in Thracian and Phrygian types of revelry - Bacchus (Dionysus) and Rhea (actually Cybele). The philosopher Plato also mentioned the festival in the dialogue between Adeimantus and Polemarchus of The Republic (Plato) about a horse-race at night, where each rider carried a torch.

Her attributes include Thracian-style pointed hat and boots made of fox-skin, while holding up a torch in one hand.[4]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

glaucon and adeimantus: socrates man PLEASE shut up about the city and just give us a definition of justice ok

socrates: okay :)

socrates:

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I had the complete opposite reaction to Afondha as I did to Adeimantus. I saw her and was like “Wowie wow what a pretty lady.” Plus the idea of a fertility goddess as a villain is very fun and different. Then you read her stuff and meeeeeh, she’s pretty boring. No particularly cool powers or motivations. She wants a war between the three princedoms who worship her… because.

She really has no reason other than, she wants it. She’s just a self absorbed goddess, the type that needs a beat down from an immaculate monk.

So is there anything interesting about her? Sure. She has a defensive charm that I think would make her pretty Tanky, doubly so when she’s inside her manse. Also she has the ability to give a positive intimacy with anyone she wins a bargain with, or who she chooses to let win a bargain. Which I assume is anyone she’s blessed.

So with very little to go on, let’s try to think of some plot hooks for her.

1. Peace is often bound by a balance of power, so in an effort to stir war between the princedoms Afondha seeks to disrupt that balance. While she continues to give strong healthy children to two of the kingdoms, she has only gives one, sickly meek children. She’ll continue to do this for as long as it takes until the entire royal line is filled with weak invalids. She hopes the thin blood in a royal line will cause the other two kingdoms to move against them. But who knows? Perhaps this generation of ill fated royalty has wisdom and courage that soars above their physical frames.

2. Afondha has a little known ability to ensure that a dragon-blooded child will exalt. This ability remains little known due to the efforts of House Nellens who want to keep Afondha as their own private resource. As such they use her sparingly to avoid unnecessary questions.

3.Afondha has blessed so many in the princedoms with children that even if the pcs unite to depose her a great number of people may come together to seek revenge. The princedoms themselves might, (ironically) unite to protect such an important part of their society. A bloody conflict with a group of exalted might actually satisfy her bloodlust.

4.Afondha considers her children to be a part of her, but how do they feel about it? Dutiful Deer recently managed to overcome his mother’s command to destabilize the princedoms, a feat of will which caused him to Exalt, much to his horror. He is anathema now, his disobedience to his mother caused him to turn to a being of pure evil. He has thrown himself at his mother’s feet begging for her forgiveness, and now this new born solar acts as his mother’s most powerful and zealous agent.

5. Afondha wins! Thanks to her influence the three princedoms engage in a terrible war that turns the water in her manse blood red. Her superiors in the celestial bureaucracy are impressed with her initiative and promote her to her direction’s new god of war. Afondha goddess of war and fertility blesses all the wombs in her domain with strong aggressive children. The crops boom as the population increases dramatically, more bodies for a yet greater war.

So that’s Afondha pretty disappointing, but that’s okay. Maybe they thought pregnancy and birth was too sensitive to do anything really out there with. Plus I had a hard time thinking of plot hooks with her, so maybe it’s just hard dude. Oh well hopefully the next villain is more exciting (he says, knowing it’s a boring Kung fu lady.)

I give Afondha 3/10 God Babies.

2 notes

·

View notes