#1940s extant garments

Text

Blue Silk Evening Dress, ca. 1940, French.

By House of Paquin.

MFA Boston.

#blue#womenswear#silk#dress#extant garments#mfa boston#20th century#france#french#1940#1940s#1940s dress#evening#evening dress#1940s evening#1940s France#house of paquin#ww2#occupation#1940s extant garments

148 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Phoenix” by Paquin, fall/winter 1949

From Tessier-Sarou

904 notes

·

View notes

Text

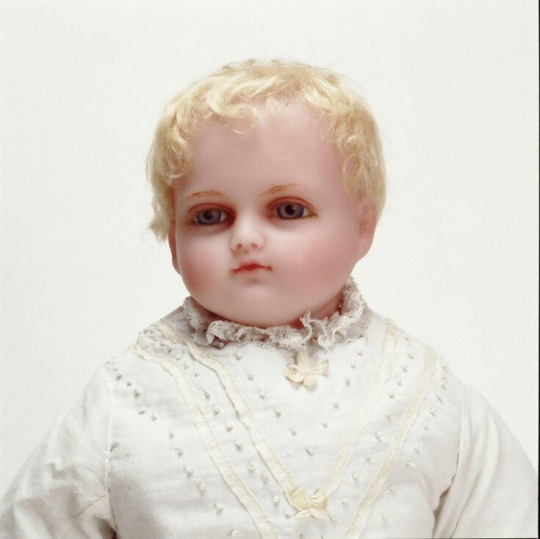

These Doll Descriptors Mean Nothing

I just saw an antique mechanical doll depicting a baby in a cradle listed as a “mourning doll" on eBay...when the mechanical elements make it move

right

this MOVING BABY is supposed to be dead. sounds legit

so let’s get into some outdated/meaningless antique doll terms, shall we?

1. Mourning doll. This old chestnut is so popular that even the great Caitlin Doughty of Ask A Mortician repeated it on her blog. Those death-obsessed Victorians just loved making wax models of their deceased children, dressed in the child’s clothes (or garments made from the fabric thereof) and wigged with the child’s hair. How spooky! How conveniently perfect for modern horror stories! How-

-fake.

I’ve heard exactly ONE confirmed story of a doll modeled after a dead child, and that was a single doll made by a family of dollmakers and never sold.

(wax doll c. 1900, allegedly modeled on Patrick Enrico Pierotti, a child of the famous Pierotti dollmaking family who died in infancy. V&A Museum)

You often see these labeled as “mourning dolls”:

(wax doll depicting a baby lying on its back, amongst flowers. probably 19th century. private sale.)

Hate to disappoint, but they were usually devotional pieces meant to represent the infant Christ. womp womp.

I’ve also seen no convincing evidence of alleged “death kits-” toy funeral kits sold to little Victorian girls so they could learn to care for the dead. Staging a doll’s funeral did happen, based on extant photographs, but kids play at every stage of life with their dolls even now. And most of those photos involve setups any child could create with things around the house, as well as perfectly ordinary dolls.

2. Frozen Charlotte. Another popular example of Those Spooky Macabre Victorians is the rumor that little one-piece ceramic dolls common in the era were named for the 1840s poem “Fair Charlotte,” about a young lady who freezes to death on the way to a winter ball.

(There are larger examples of one-piece ceramic dolls from this era, but most are small and rather crudely painted; see above)

However, that term seems to have originated among collectors in the 1940s. Contemporary sources simply call the dolls “penny dolls” or “penny babies,” in reference to their low prices.

3. Mignonettes. Little jointed all-bisque dolls have been commonly given this name among collectors for ages. However, there’s no evidence for its contemporary use- the French seem to have called them “poupees a poche,” (pocket dolls), and most of them came from Germany anyway.

(All-bisque doll by the Kestner firm, late 19th century)

4. Milliner’s models. Another bit of collecting jargon often used for dolls of the early to mid-19th century with papier-mache heads. Invented in the 20th century to reflect the fanciful and entirely unsupported notion that thy were used to model the latest fashions in shops, as opposed to being primarily toys with secondary, coincidental fashion-related functions for a child’s mother, older sister, etc. Contemporarily, they seem to have been called “varnished-head dolls” when referenced as a distinct category at all.

(Papier-mache headed doll c. 1830s)

There are many more, but there are four of the most common to look out for!

339 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last night’s complaining about period drama costuming inaccuracies has me thinking about how, if you watch a period drama made more than, say, two decades ago, you can generally see the styles contemporary to the time when the film was made creeping in to the decisions they make about how to present the era they’re trying to portray, with greater or lesser degrees of intentionality. This is not, inherently, a bad thing — the point of an adaption is basically never to appeal to a tiny subset of your audience who knows everything about the original text and it’s implications, meta-textual references, and the wider contemporary aesthetic culture in which is was created. That audience is pretty much guaranteed to a. buy tickets and b. complain about something, and if you get too obscure everyone else in your wider general audience will hate it anyways.

If it’s a good adaptation, the point is to translate the work in a way that preserves the greater part of the integrity of the original, while communicating with your audience in the languages and references that they understand.

So what I’m wondering is how to categorise period dramas in line with this theory of ‘period it’s set in via period it’s made in’. So far I’ve got:

1. The production team and audience thought it was scrupulously accurate at the time and were accordingly smug about it, but with the benefit of a few additional fashion cycles the contemporary influence starts to pop out:

Pride and Prejudice 1995. Sea of brown interior decor, men’s costumes fit like men’s suits of 1995 (ie they don’t), the women are in wonderbras and high pony tails curled to look like approximations of regency updos, all the fabric has the weight and sheen of a cotton bedsheet, and everyone’s wearing max factor lipstick in like, rustic rose. Hats and headwear make an appearance, but are not that accurate and are basically just...there. (I want a bonnet trimming scene!)

Pride and Prejudice, 2005. ‘But is was inspired by the 1790s!’ Yeah and it gets the 1790s wrong. Where’s the cool ‘Turkish’ fancy dress and big sashes? Why is Elizabeth wearing knee-high leather boots? Set design is good, though.

Any high-end BBC drama ever. See their War and Peace

Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries

Elizabeth (the Cate Blanchett one)

Marie Antoinette (the Norma Baker one). 1940s shoulders and makeup.

2. Highly accurate, but stylised. Contemporary influences are largely deliberate and often highlighted:

Marie Antoinette (the Sofia Coppola one). The converse shoes in the wardrobe, embroidered arm warmers and manic panic hair dye are obviously not accurate but they’re visually complementary to the actual fashions of the 1780s/90s, and function as character-establishing shorthand for an audience who does wear those things.

Emma., (2020). Fantastic and deliberate set styling and costuming, some very good replicas of extant garments. Emma’s hair is a slightly odd choice, but it gives her a bitch factor that’s vital to the character. Going to look ‘early 2020s’ in a decade or two (the colour palette is straight up VSCO girl).

The Great. Peter’s leopard skin coat is accurate, but Catherine’s hot pink robe sure ain’t.

Anna Karenina (the Joe Wright version). It looks like a very long ad for paspaley jewellery, but the silly moustaches are wonderful.

3. By and large Actually Accurate, featuring some obscure fads that don’t get remembered in the popular consciousness, and characters who are allowed to have actual personal taste:

Bright Star. The main character’s a very serious courturier and always looks very deliberate. What’s-his-name next door is equally deliberate, but he’s an asshole who wears ugly plaid trousers on purpose.

4. Our budget and time is limited and our extras crew is large, so we went with visual cohesion over really striking outfits except for one or two key characters and scenes. No one claims the fabric choices are accurate. People talk about silhouettes a lot. There are no soft furnishings anywhere:

The Crown

The Favourite (bonus points for putting men in high heels, wigs and makeup and still presenting them as conventionally masculine rather than as aberrations)

Mary Queen of Scots

5. ‘Foreign’ films. Set in a culture substantially distinct from that of the production crew, may or may not veer into weird exotic fantasy in a gross way:

Memoirs of a Geisha. Saying nothing of the plot (😬) there was a lot of work put into individualising the costumes in a way that a western audience could indentify.

6. Our budget is a hundred bucks and a packet of Doritos, we borrowed a dress made sixty years ago for the pivotal scene and the actors wore their own jewellery:

Mid-to-low end BBC adaptations

Doctor Who

7. Soap operas for history nerds who also watch The Bachelor:

The Tudors

Reign

Wildcard. The characters are time travellers:

Outlander, especially seasons 1&2 because the later seasons are ‘jail and on-the-run’ chic. Claire’s 1780s-by-1950s looks aren’t meant to be accurate, they’re meant to make her look stylishly out of place.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Aladin", Dior, f/w 1947

I've written a lot (a lot) about why it's wrong to put Chanel, and even Chanel plus Poiret, up on a pedestal as the pivot(s) of a sharp turning point in fashion, but I've only touched on Dior and the New Look once or twice. Just like the earlier narrative compresses time to juxtapose frothy Edwardian gowns against the short, narrow dresses of the mid-late 1920s, the centering of Christian Dior as the inventor of stereotypical 1950s fashion in 1947 is a big oversimplification.

Women's fashion for much of the 1930s was streamlined: the overall emphasis was on a sleek line from shoulder to ankle. At the beginning of the decade, the tubular figure of the 1920s was still common, but within a few years dresses and skirts were being worn with waistbands and belts at the natural waist. By 1935, it was common for jackets to be made with built-up or padded shoulders, turning the silhouette into a long, slender carrot shape.

In 1938, however, the skirt was shortened to hit below the kneecap, while high fashion in 1939 added flare to the hem. The width of the outfit at the shoulders and knees was balanced by a narrow waistline - the silhouette was an hourglass.

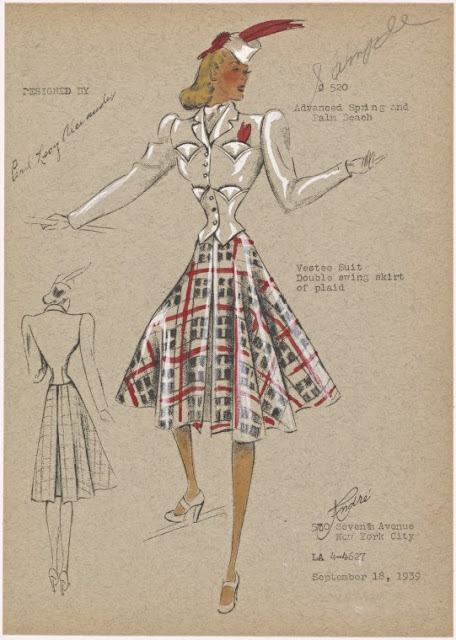

"Vestee Suit", Pearl Levy Alexander for André, Sept. 1939 - very similar to a design by Dior for Piguet in 1938!

Clothing was regulated during the war years, in order to ensure that there was enough fabric to go around for the war effort, and as a result fashion "froze" - and even moved back, to some extent.

The US War Production Board announced strictures regarding yardage, number of buttons and pleats, amount of stitching, etc. allowed on a garment in April 1942. Clothes rationing in the UK had been announced in June 1941, allowing hardly more than one new outfit or garment per year, and commercially-made clothing had to follow similar regulations, as did homemade and bespoke clothes after May 1942. Even neutral Ireland introduced rationing for clothing in June 1942, and fashions generally followed the lines of British "utility dress". In France, fabric was hard to come by from the beginning of the war, causing the spring/summer 1940 collections shown in Paris to be somewhat skimpy, and in January 1941 (under the occupation), a very strict rationing system was introduced.

Not everyone followed the regulations: there are numerous examples of extant American clothes from the war years that show supposedly banned notions like fabric-covered buttons and zippers. Still, the shape of the fashionable skirt changed across the West to have less fullness, something more like the silhouette of 1938 but still with a slight flare at the knee. The fashionable jacket of the period was typically long, often with the hips emphasized by patch pockets and the waistline tailored in - also similar to late 1930s styles.

These restrictions lasted beyond the length of the war in Europe: Irish clothing rationing would not end until 1948, and British rationing until 1949. The haute couture industry, however, bounced back relatively quickly. Its needs had bypassed rationing, although it had never flaunted that fact by showing designs based on a silhouette that was wildly inaccessible to the average person, and it was needed to encourage the wealthy to keep adding to the economy. While many of Paris's fashion houses had shut down during the occupation due to a lack of customers, the couturiers returned in 1944-45 to produce the Théâtre de la Mode, an opulent traveling fashion show done at a doll scale. Following the production, the couturiers re-dressed the dolls for 1946 and sent them abroad. The Parisian fashion industry then went back to full-scale, twice-yearly fashion shows and regained its prominent place in the market.

What is particularly important about the Théâtre de la Mode clothing is that the designers stepped back to 1940, picking up where fashion had paused as governments regulated the sweep of a skirt and the fullness of a sleeve. These garments - the collaborative work of more than fifty couturiers, including Dior, who was working for Lelong - very frequently show the luxuriously wide hemlines (as well as very narrow ones) that would become everyday dress in the coming years.

Christian Dior's first fashion show under his own name was in February of 1947, not very long after the Théâtre. This is the show where he premiered his Corolle and En Huit lines (the former with full skirts and the latter with pencil skirts), which contained the famous black and white Bar Suit and is said to have prompted Carmel Snow to declare that he had created a "new look".

Another suit from Corolle, 1947

But the Corolle designs were not a complete break from what was being worn before, as they're often represented. The overall cut of the long jackets, with built-up but not-too-broad shoulders, had been fashionable in 1946: the major innovation was the way the peplums were stiffened and shaped. The skirts also were made with more fabric, either knife-pleated like the Bar skirt or box-pleated like the one above, and were several inches longer, but were still worn in a long A-line shape. And as suggested by the fact that the collaborating couturiers came up with similar designs in miniature in 1945, Dior was not alone in shifting away from the wartime standards in early 1947. His work did stand out as belonging to an excellent newcomer, but as Vogue stated,

... almost all of the new Paris collections have this in common: they start no revolutions, but rather make new use of fashion themes that have been crystallizing for seasons past, and which look fresh and inviting.

Something I've discussed before when it comes to the early 1920s is the popular tendency to take primary sources at face value. If a columnist in the London Times in 1921 complained that young women were going out at night barely dressed, this is often taken as meaning that young women in 1921 could not get less covered up, when in fact there was still room to keep going in that direction - it's just that commentators were coming from a different context and couldn't see the future. Likewise, the changes that occurred between 1945 and 1955 get squished into this one fashion show in pop culture because commentators in early 1947 described the changes occurring as major, as they obviously couldn't tell that styles would continue to develop in the same direction to an extreme. They called the fuller skirts of 1947 "bouffant" because they were puffed out in comparison to the earlier straight ones, but the skirts that are bouffant by our standards, springing out from the waist in a wide froth of petticoats, did not come in until late 1951. The shoulders of suits and dresses in the 1947 shows were less wide than in the war years, but their sleeve heads were still usually well out on the shoulder and often padded or structured to give a firm counterbalance to the skirt and draw straight, diagonal lines down to the waist. This also lasted for some time, eventually phasing out as more and more dresses were made with wide necklines and/or without sleeves.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. Please introduce your chosen subject area. What interests you as potential starting points or areas of research? What influenced this choice? (650 words)

I have chosen to base my project on the book ‘The Starless Sea’ by Erin Morgenstern. This is a book following several characters set mostly in an expansive and sprawling underground library, separate from our world. At the time the book is primarily set in the library is in slight disrepair and, as is the natural order of things for the library, ready to be flooded by the sea of honey. I have chosen this book as the basis of my project for two reasons. Firstly this book, at the time of writing this, has no official illustrations, film, or visual media depicting the characters or much of the world. This gives me a great basis to start on as it will only be my own interpretation of the original text that will be influencing my work for this project. The second reason I have chosen this book is simply because I love it!

As a starting point for my research into this I have transcribed every quote in the book that relevantly mentions a character or their clothing/costume and sorted them by character. My next steps are to narrow this down to just a few areas of research about specific characters. Before that though I would like to explore my interpretation of the books world, specifically the library. To do this I plan to visit and record various libraries and places that hold lots of books like bookshops. I would also like to look into alternative ways of recording stories other than being written down in books, this is because the library in ‘The Starless Sea’ holds countless stories but not all of them are recored in bound form. I would like to explore stories held in tapestries, in scrolls, in paint, in performance, and many other methods. I also think it would be helpful for me to visit local vintage or junk shops to find and photograph interesting objects that I could take inspiration from. In the book the library has been around for a long time mostly separate from our society, I think it would be interesting to explore how the people who visited the library across eras have brought things over and how they could have influenced the library itself. The idea of the library as a place created by its visitors and furnished by things that people value from across time is how I would like to present it in this project.

In terms of characters I am interested in costuming I am less interested in the main characters and more drawn towards characters that are slightly more fantastical but maybe have less description about the specifics of what they are wearing and why. For example The Sun and The Moon are characters who appear only briefly but I am really interested in pursuing that as a potential avenue for this project. I think designing them as almost two sides of the same coin could be good, for example using similar constructions methods but with vastly different colour ways and embellishment design.

For gathering inspiration for any character garment I will visit museums to see extant garments so I can find things to be inspired by from a variety of time periods. The inhabitants of the library have no obligation to follow our society’s fashion trends so it could be interesting to explore how styles could have evolved within the library using only the clothes that people enter with or make. For example a garment that has the sleeves of an 1890’s gown but the body of an 1940’s blouse. It would also be helpful to make sure I research international historical fashion as well as just western fashion because the library is an inherently multicultural place, the doors aren’t just in one location they are all over the world and it is important to represent that as best I can.

0 notes

Text

Peach Coutil Girdle, 1942-1949, English.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#peach#coutil#girdle#corset#1940s#1942#1950s girdle#1940s corset#1940s undergarment#undergarments#extant garments#1940s extant garment#English#British#1940s England#1940s Britain#V&A

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold Leather Shoes, ca. 1935-1940, Scottish.

From Chalmers & Son.

National Museums Scotland.

#gold#leather#shoes#1935#1930s shoes#1930s Scotland#1930s britain#Britain#British#Scotland#scottish#1930s#national museums scotland#charmer & son#1936#1937#1938#1939#1940#1930s extant garment

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Green Velvet Evening Dress, ca. 1945, English.

MFA Boston.

#womenswear#extant garments#velvet#silk#dress#mfa boston#20th century#1945#1940s#1940s England#English#British#England#Britain#green#1940s britain#1940s dress#ww2

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Taffeta Cocktail Dress, 1949, French.

MFA Boston.

#womenswear#extant garments#silk#taffeta#20th century#dress#cocktail dress#france#french#1949#1940s dress#1940s France#black#mfa boston

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Girl’s Skating Ensemble, 1940s, English.

MFA Boston.

#mfa boston#blue#child#children#extant garments#skating#skating ensemble#1940s#English#England#British#Britain#dress#20th century#1940s England#1940s britain#1940s skating

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pale Pink and Grey Silk Shantung Evening Dress, 1947, American.

MFA Boston.

#pink#pale pink#grey#womenswear#extant garments#silk#shantung#dress#20th century#mfa boston#american#usa#1947#1940s#1940s dress#1940s usa#Hollywood#california#evening dress#1940s evening

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pink Silk Edwardian Style Pantomime Costume, 1944, English.

Worn by Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth II).

Royal Collection Trust.

#pink#silk#lace#20th century#costume#pantomime#pantomime costume#dress#stage costume#royal collection trust#queen Elizabeth ii#Elizabeth ii#extant garments#royal#womenswear#British#Britain#1944#1940s#1940s Britain#1940s costume#known wearer#english#england#1940s England#candy pink

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red and White Shirt Dress, ca. 1945, English.

By CC41.

MFA Boston.

#cc41#womenswear#extant garments#dress#20th century#mfa boston#red#English#England#British#Britain#1945#1940s#1940s britain#1940s dress#1940s England

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peach Pink Chiffon Boudoir Robe, 1940s.

Augusta Auctions.

#womenswear#extant garments#chiffon#20th century#peach#pink#peach pink#Augusta auctions#robe#boudoir robe#1940s#1940s robe

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Purple and Blue Striped Dress, ca. 1954, English.

By CC41.

MFA Boston.

#mfa boston#womenswear#extant garments#dress#cc41#20th century#1945#1940s#1940s dress#1940s England#1940s Britain#British#Britain#England#English#purple#blue#ww2

2 notes

·

View notes