#“Eruption of Vesuvius with Destruction of a Roman City”

Text

𝔖𝔢𝔟𝔞𝔰𝔱𝔦𝔞𝔫 𝔓𝔢𝔱𝔥𝔢𝔯 (յԴգօ-յՑկկ)

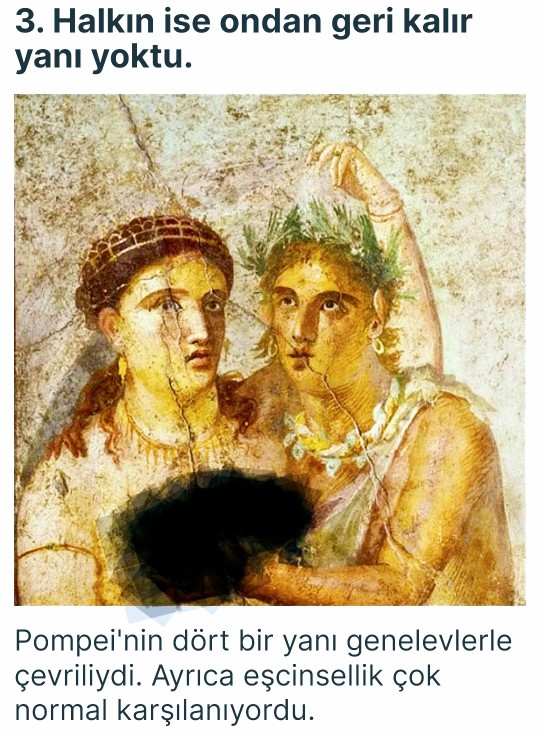

"𝔈𝔯𝔲𝔭𝔱𝔦𝔬𝔫 𝔬𝔣 𝔙𝔢𝔰𝔲𝔳𝔦𝔲𝔰 𝔴𝔦𝔱𝔥 𝔇𝔢𝔰𝔱𝔯𝔲𝔠𝔱𝔦𝔬𝔫 𝔬𝔣 𝔞 ℜ𝔬𝔪𝔞𝔫 ℭ𝔦𝔱𝔶" յՑշկ

#Sebastian Pether (1790-1844)#“Eruption of Vesuvius with Destruction of a Roman City”#1824#Sebastian Pether#vesuvius#vulcan#art#artwork#painting#illustrations#illustration

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Tango In Time -- Chapter #1

Summary: While on your walk through the marketplace, a strange man appears in weird clothing; bidding bad tidings. He sweeps you into his arms, and all of a sudden...you're not in Pompeii anymore.

Pairing: TVA!Loki x Roman!Reader

Warning(s): mentions of death and destruction, Loki being a mischievous scamp

As a resident of Pompeii, you lived a simple life in the shadow of the great Mount Vesuvius. You had always known that there was the possibility that the volcano could erupt at any moment, but you never truly expected it to happen; let alone when you were enjoying the sights of the marketplace.

But as the sky turned grey and the ground began to tremor beneath your feet, you knew that it was the end. You closed your eyes, waiting for the inevitable, but when you opened them again, you saw a man in some sort of beige cloth standing in front of you. He had a mischievous smile on his face and a glint in his eyes that made you uneasy.

"Nothing matters," he declared, his sultry voice ringing in your ears. He seemed to be talking to someone else, but you were the only one standing there. Suddenly, he grabbed your hand and pulled you towards him.

"What are you doing?" you asked, trying to pull away.

"I'm proving a point," he replied, a smirk on his lips.

You had no idea what he was talking about, but before you could protest, he began to swing you around. You stumbled at first, but soon found your footing and began to move with him. The world around you was crumbling and falling apart, but in that moment, all that mattered was the two of you dancing in the midst of destruction.

As the ground continued to shake and the sky turned black, the man in beige continued to dance with you. You had no idea who he was or what he wanted, but you couldn't help but feel drawn to him. His confidence and charm were intoxicating, and for a moment, you forgot about the impending doom.

But just as quickly as it had started, the dancing stopped. The man in beige suddenly let go of your hand and seemingly disappeared, leaving you alone in the chaos of your city's impending doom.

A shaky sigh was all you managed to get out before someone grabbed your arm and pulled you through some sort of glowing light. And the next thing you knew, you were standing in a strange room surrounded by people in strange clothes.

Confused and disoriented, you stumbled forward, trying to find your bearings. Suddenly, the man in beige appeared again, this time with another man in what you're assuming to be formal garb.

"Welcome to the TVA," he said, his mischievous smile never leaving his face. "You're not supposed to be here, but I couldn't resist bringing you along."

You had no idea what he was talking about; what was a TVA? But before you could ask, the man in the formal clothes interrupted.

"Loki, what have you done?" he asked, his voice sounded stern, but the words he spoke were extremely foreign.

The man in beige's -- now known as Loki's-- smile faltered for a moment, but he quickly regained his composure. "Relax, Mobius. She's not going to cause any harm."

You sent a confused glance to Loki, "What is this man saying? Where is he from? Greece? Persia?"

Loki's eyes seemed to widen with realisation, "Ah, I apologise my lady. Let me fix this problem." With that, a green haze washed over you, a startled yelp slipping from between your lips.

"Are you two done with your little show?" The older man--who you assumed to be Mobius--asked.

Loki scoffed, "I was not putting on a show! She couldn't comprehend a word that slipped through your lips; so I gave her a little help."

Mobius just sighed, "She's not supposed to be here, Loki. You know the rules," his frustration evident in his tone.

"But isn't that the point? To show you that apocalypses don't affect the timeline?" Loki retorted.

"I was there with you! I saw the evidence on the Tempad! There was no need for you to bring a random woman back with you," Mobius said, crossing his arms.

"Ah, but where's the fun in that? Besides, she seemed like she needed some excitement in her life. Being burned alive or suffocated by volcanic ash doesn't seem like a good pass time," Loki replied with a sly grin.

Your eyes practically bulged out of your head, "What?"

A/N I've had this idea in my drafts for so long...so it's amazing to finally have something to post. This is probably going to be a short story, maybe 5 or 6 part at most.

This is one of my many ideas for my 500 followers celebration!

🏷 @thewaithfuckingannoyme @evelyn-kingsley @moonlight-ee @dryyoursaltyoceantears @avahiddlestonstan @fall-myriad

lemme know if you wanted to be added to any of my taglists!

#loki#loki laufeyson#loki x reader#loki laufeyson x reader#fem!reader#tva#tva loki#mobius#mobius m mobius#tva mobius#loki series fanfic#loki fanfic#tom hiddleston#tom hiddleston character

230 notes

·

View notes

Video

Remains of Three New Pompeii Victims Discovered

The remains of three new Pompeii victims have been unearthed beneath the towering shadow of Mount Vesuvius - almost 2000 years after its catastrophic 79 CE eruption.

The skeleton remains are believed to have belonged to two women and a child, aged between three and four years old.

The trio are believed to have died while seeking shelter in what is suspected to be a bakery, during the first stage of the eruption.

"In these last rooms the bone remains of three victims of the eruption have surfaced," a statement from Pompeii Archaeological Park said.

"Three Pompeians who had taken refuge in search of salvation and who instead found their death under the collapsed attics.

"The individuals were found in an already excavated environment, where only 40cm remained of intact stratigraphy (earth).

"They rested in direct contact with the floor, and presented - together with evidence of important postmortem settlement processes - a series of perimortem traumas due to the collapse of the attic above."

A structure with two intact fresco walls were also discovered as part of the ongoing excavations in an area called Regio IX, a commercial part of town.

One of the walls depicted the sea god Poseidon and Amimone, the other portrays the sun god Apollo and his first love Daphne, who swore to remain a virgin and spurned his advances.

The discoveries come weeks after the remains of two victims, believed to be men, were found beneath a collapsed wall.

The ancient Roman city was destroyed when Vesuvius roared to life the morning of August 24, 79 CE.

By lunchtime the volcano had sent a towering ash and debris cloud into the stratosphere, which rained pumice down on the town as earthquakes rumbled foundations.

This is known as the Plinian phase, which lasted for about 20 hours, and is thought to have been when the three victims perished.

Destruction came for Pompeii in the second eruption stage, known as the Pelean phase.

Pyroclastic surges of molten rock and hot gases surged down the volcano's slopes, burning and asphyxiating people before they had a chance to flee, burying the city.

The eruption is said to have released 100,000 times the energy of the Hiroshima-Nagasaki atomic bombings in World War II.

It's estimated 2000 people died in Pompeii.

However, the exact death toll from the eruption is not known as casualties also occurred in the nearby settlements of Herculaneum, Oplontis, and Stabiae.

#Pompeii#Remains of Three New Pompeii Victims Discovered#Mount Vesuvius#ancient grave#ancient tomb#skeletons#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

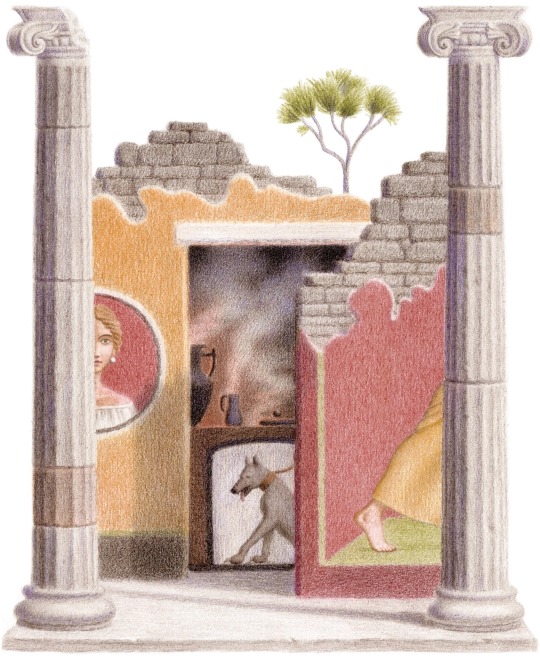

Title: Eruption of Vesuvius with Destruction of a Roman City

Artist: Sebastian Pether

Date: 1824

Style: Romanticism

Genre: History Painting

158 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius

The Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE remains one of the deadliest natural disasters in recorded history. Not only did the volcano destroy the economically powerful city of Pompeii, but Herculaneum, Oplontis, Stabiae were also buried and thus lost to the Roman Empire. The number of victims is unknown, but given the size of the four cities, estimates have reached over 18,000 individuals.

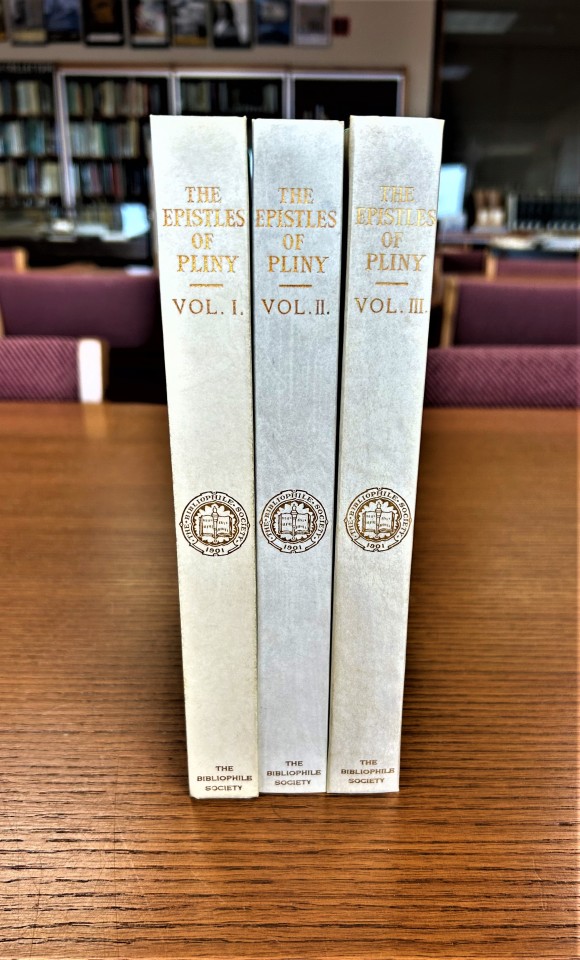

Today only one first-hand account of this horrific event survives in two letters from Pliny the Younger to the Roman historian Tacitus. They are preserved as letters 6.16 and 6.20 in the collected Epistles of Pliny. Among our holdings of the works of Pliny is this 3-volume set of the Epistles with William Melmoth’s 18th-century translation edited by Clifford Herschel Moore, and printed by the Harvard University Press in an edition of 405 copies for members of The Bibliophile Society, Boston, in 1925.

While the term ‘volcanic eruption’ evokes scenes of lava and fire, the reality is much more frightening. Curiously, there is no word for volcano in the Latin language. While ancient Romans were aware of the destructive power of volcanoes, there’s some debate about whether they were aware that Vesuvius was a volcano before its eruption. Signs of the eruption began back in 62CE with a great earthquake that caused much of the city to collapse. Smaller earthquakes continued over the next 15 years until one was accompanied by the rise of a column of smoke from Mt. Vesuvius in October 79 CE.

The hot gases that made up the column of smoke began to cool, darkening the sky, and not long after a rain of pumice began to fall, and after 15 hours ceilings began to collapse. Nevertheless, many residents chose to take shelter rather than flee. At 4am the first 500C pyroclastic surge barred down the volcano, burying Herculaneum. Six more of these surges occurred before the end of the eruption, destroying Pompeii, Oplontis, and Stabiae.

The 17-year old Pliny was in the port town of Misenum across the Bay of Naples from the volcano at the time. Pliny’s uncle, Pliny the Elder, commander of the Roman fleet at Misenum, launched a rescue mission and went himself to the rescue of a personal friend. The elder Pliny did not survive the attempt. In Pliny the Younger’s first letter to Tacitus, he relates what he could discover from witnesses of his uncle's experiences. In a second letter, he details his own observations after the departure of his uncle.

Mt. Vesuvius is still active and according to volcanologists, erupts about every 2000 years, which would be right about now. Who will be our next Pliny the Younger?

Our copy of The Epistles of Pliny is another gift from our friend and benefactor Jerry Buff.

View more of my Classics posts.

– LauraJean, Special Collections Undergraduate Classics Intern

#Classics#classical history#Roman History#Mt. Vesuvius#Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius#Pliny the Younger#Epistles of Pliny the Younger#Pliny the Elder#Tacitus#William Melmoth#Clifford Herschel Moore#Harvard University Press#The Bibliophile Society#volcanic eruptions#Pompeii#herculaneum#Oplontis#Stabiae#Jerry Buff#LauraJean

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Villa of the Papyri is the name given to a private house that was uncovered in the ancient Roman city of Herculaneum. This city, along with nearby Pompeii, is perhaps best remembered for its destruction during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. Because of this natural disaster, the buildings of these cities were preserved under a thick layer of volcanic ash.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legend during the Roman-era Horrors

--------------October 3rd, 79 AD-----------

----------Eruption of Mount Vesuvius-------

Legend palmed his hands through the descended barrages of smoke and ash, sprinting through streets of splintering pavement and burning civilization. The panicked crowds of civilians ran from the ruins of their homes, thinking their fate punishment from the gods.

A fair assessment; one that Legend didn’t fault them for. When the shadows of hades blotted out the sun, and it’s armies rampaged your torched streets; It was hard not to take it personally.

The truth of the matter was far less grandiose; the truth of the matter was that those behind this atrocity were hijacking Mount Vesuvius for their vile rituals, and Pompeii had the unfortunate position of being the first city caught in the crossfire.

And by the names of all that’d perished today; Legend would ensure it’d be the last.

He tried not to blame himself for the death and destruction before him, for the countless people he’d be unable to save. It tore his heart asunder to ignore the plight of so many, to not help in their hour of need. It was his uncle all over again; cradling his dying body in his arms, his sorrowed guilt snowballing into a crippling avalanche of regrets and newfound responsibility.

But he couldn’t spare a moment, as much as it pained him. If he didn’t slay the source of this darkness soon, then there’d be nothing short of divine intervention able to stop it from rolling over all of europe--and then the world. The whole of humanity rendered extinct in less then a week.

To say the stakes were high would be the understatement of the millennium; an impressive feat considering that the current year hadn’t even reached the triple digits.

At least he didn’t have to go it alone.

Legend, having reached the city’s central plaza, stopped at the cremated remains of it’s marketplace--seeing a familiar face--just the person he wanted to see, in fact.

“Legend! I just got the southern districts evacuated, how is it on your end?”

It was Traveler, and by the look of the tar-like blood soaking his boots; he’d gotten busy.

“Not good, sorry to say,” Legend explained, frustration evident, ”I barely escaped the northwest before it got cratered, and the northeast has more moblins than citizens.”

Traveler recoiled at the news, his face souring to a scowl not unlike Legend’s, “Why does our rain always pour?” Traveler said.

“I’d tell you if I could, but that’s for later. What’s the word on the Captain? Have you been able to contact him?” Legend asked.

Traveler shook his head, “He’s either out of range, or can’t pick up a stone.”

Legend narrowed his eyes, confusion overtaking him, “Wild made their ringing sound like a flock of keese going through a Wizzrobe’s windpipe,” Legend exasperated, ”How in Din’s name can he not hear i--You know what, you know what, he can explain himself later-”

A chorus of ear splitting explosions ruptured the air, deafening the rest of Legend’s words. Miles upon miles of smoke spewed from Vesuvius’s peak, blistering waves of primeval fire and lava-coated meteors hailing down to the already destroyed city.

“-...We’ve got bigger fish to fry,” Legend said,

Legend put a hand in his adventuring bag, scrounging around, eventually pulling out a slender staff, prismatic light twinkling from it’s crystallized tip; gusts of frigid wind emanating forth from it’s cerulean body.

“Fire and brimstone aren’t the only things that are going to be crashing. You need to find Warriors, and stem this tide before it hits other settlements,” Legend said, his scowl pointed at the mountain.

“I understand but what about *you?* I’m not going to just leave you to fight all of that alone,” Traveler responded, placing a concerned hand on Legend’s shoulder.

For a split second, Legend’s expression softened, the care of his brother not lost on him.

“I’ve beaten Onox before, and I can do it again. Just because he has the strength to capture an oracle, and wrangle a mountain--doesn’t mean he’s anything close to intelligent,” Legend said, “And we aren’t going to leave the captain to the wolves, nor the people of rome.”

Traveler nodded, a pang of distress flashing over his focused gaze, “Your right..I’ll get going.

The younger hero went to leave, stopping to turn back at his brother, resolute, “When the smoke clears, I’m coming back to get you--one way or another.”

Legend cracked a smile, the direness of their troubles briefly washing away.

“There wasn’t a doubt in my mind; now go! This armageddon isn't gonna wait around for any one of us."

#linkeduniverse#linked universe#i call hyrule traveler this is not a negotiation#oneshot#lu hyrule#lu legend#drabble#blurb#short fic#fanfic#linked universe fanfic#light angst#eclipse au#kovac fic

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Did the City of Pompeii Perish?

Pompeii is an ancient city located in the Campania region of Italy, near the city of Naples. Like Sodom and Gomorrah, Pompeii is one of the cities punished by God.

Pompeii is in Italy, a symbol of the degeneration of the Roman Empire. The city of Pompeii, like the people of Lot, was also bankrupt due to sexual perversion.

THE DESTRUCTION OF THE PEOPLE OF POMPEI

Historical records report the state of the city before its destruction as a complete perversion, rudeness, and immorality that has come to the end. Seventy years after Jesus -aleyhisselam-, with a sudden eruption of Mount Vesuvius, lava wiped the city off the map, and no one could escape from divine torment. The foolish wretched ones are petrified while in a state of overt perversion.

This incident happened in an instant. All immoral people were caught in this divine torment at once. Its ruins have come to the present day without any deterioration and show a great lesson.

In the Qur'an, similar events of sudden extinction are mentioned as follows:

“(Them) only one cry (it was enough); they went out instantly.” (Yasin, 29)

The people of Pompeii were instantly destroyed in this way. The ugly sights of those petrified miserable people, dating back nearly nineteen hundred years, are one of the exemplary paintings of history.

Allah Almighty says:

“We destroyed many human generations before them. Do you see any of them or hear any of their faint voices?” (Mary, 98)

The exemplary pages of history are almost like a graveyard of nations. Unbelief, immorality and cruelty are the main causes of destruction and extinction of nations. What a magnificent manifestation of divine vengeance is the "sekerat-i mawt" of unbelieving and cruel tribes. Despite the long centuries that have passed, today Pompeii displays the petrified warning signs of immoral people. It's like human silhouettes that become spiritually animalistic!..

These exemplary manifestations also consist of simple sculptures for the unconscious minds who cannot see their truth and watch the events with a soulful sense.

Today, only owls are cheering up Sodom-Gomorrah, the place of ruthless, lewd and immoral wretches, and the magnificent stone-carved mansions of Ad and Thamud, who idolize their souls and think that the world is a throne that always grants them happiness!

Source: Osman Nuri Topbaş, Series of Prophets 1, Erkam Publications....... Pompeii Şehri Neden Yok Oldu?

Pompeii, İtalya'nın Campania bölgesinde, Napoli şehri yakınlarında bulunan antik bir şehirdir. Sodom ve Gomorra gibi Pompei de Tanrı tarafından cezalandırılan şehirlerden biridir.

Pompeii, Roma İmparatorluğu'nun yozlaşmasının bir simgesi olan İtalya'dadır. Lut halkı gibi Pompei şehri de cinsel sapıklık nedeniyle iflas etmişti.

POMPEİ HALKININ YIKILMASI

Tarihi kayıtlar şehrin yıkılmadan önceki durumunu tam bir sapıklık, terbiyesizlik ve sonuna gelmiş ahlaksızlık olarak bildirmektedir. İsa aleyhisselam'dan yetmiş yıl sonra, Vezüv Yanardağı'nın aniden patlamasıyla lavlar şehri haritadan sildi ve kimse ilahi azaptan kurtulamadı. Aptal zavallılar, aleni bir sapıklık halindeyken taşlaşırlar.

Bu olay bir anda oldu. Bütün ahlaksızlar bir anda bu ilahi azaba kapıldılar. Kalıntıları herhangi bir bozulma olmadan günümüze kadar gelebilmiş ve büyük bir ders vermektedir.

Kuran'da benzer ani yok oluş olayları şöyle anlatılır:

“(Onlar) sadece bir çığlık (yeterdi); anında dışarı çıktılar.” (Yasin, 29)

Pompeii halkı bu şekilde anında yok edildi. Yaklaşık bin dokuz yüz yıl öncesine dayanan bu taşlaşmış sefil insanların çirkin manzaraları, tarihin örnek tablolarından biridir.

Yüce Allah diyor ki:

“Onlardan önce birçok insan neslini yok ettik. Onlardan herhangi birini görüyor musun ya da zayıf seslerini duyuyor musun?” (Meryem, 98)

Tarihin örnek sayfaları adeta bir milletler mezarlığı gibidir. Küfür, ahlâksızlık ve zulüm, milletlerin yok olmasının ve yok olmasının başlıca sebepleridir. Kafir ve zalim kavimlerin "şekerat-i mevt"leri, ilahi intikamın ne kadar muhteşem bir tecellisidir. Aradan geçen uzun yüzyıllara rağmen, bugün Pompeii ahlaksız insanların taşlaşmış uyarı işaretlerini sergiliyor. Ruhsal olarak hayvanileşen insan silüetleri gibi!..

Bu ibretlik tezahürler, kendi hakikatini göremeyen ve olayları duygulu bir duyguyla izleyemeyen bilinçsiz zihinler için de basit heykellerden oluşmaktadır.

Acımasız, ahlaksız ve ahlaksız zavallıların yurdu Sodom-Gomorra'yı, Ad ve Semud'un nefis taştan köşklerini, ruhlarını putlaştıran, dünyayı kendilerine hep mutluluk veren bir taht zanneden bugün sadece baykuşlar neşelendiriyor. !

Kaynak: Osman Nuri Topbaş, Peygamberler Dizisi 1, Erkam Yayınları. بومبي ��ي مدينة قديمة تقع في منطقة كامبانيا بإيطاليا بالقرب من مدينة نابولي. مثل سدوم وعمورة ، بومبي هي إحدى المدن التي عاقبها الله.

تقع مدينة بومبي في إيطاليا ، وهي رمز لانحطاط الإمبراطورية الرومانية. مدينة بومبي ، مثل شعب لوط ، أفلست أيضًا بسبب الانحراف الجنسي.

تدمير شعب بومبي

تشير السجلات التاريخية إلى حالة المدينة قبل تدميرها على أنها انحراف كامل ووقاحة وفجور وصل إلى النهاية. بعد مرور سبعين عامًا على يسوع -عليهيسيلام- ، مع ثوران مفاجئ لجبل فيزوف ، قضت الحمم البركانية على المدينة من الخريطة ، ولم يتمكن أحد من الهروب من العذاب الإلهي. البؤساء الحمقى مرعوبون وهم في حالة من الشذوذ العلني.

حدث هذا الحادث في لحظة. تم القبض على جميع الفاسقين في هذا العذاب الإلهي دفعة واحدة. لقد وصلت أنقاضها إلى يومنا هذا دون أي تدهور وتظهر درسًا كبيرًا.

ورد في القرآن أحداث مشابهة للانقراض المفاجئ على النحو التالي:

"(لهم) صرخة واحدة فقط (كانت كافية) ؛ خرجوا على الفور ". (ياسين ، 29)

تم تدمير شعب بومبي على الفور بهذه الطريقة. المشاهد القبيحة لهؤلاء الناس البائسين المتحجرين ، التي يعود تاريخها إلى ما يقرب من ألف وتسعمائة عام ، هي واحدة من اللوحات النموذجية للتاريخ.

يقول الله تعالى:

لقد دمرنا العديد من الأجيال البشرية التي سبقتهم. هل ترى أيًا منهم أو تسمع أيًا من أصواتهم الخافتة؟ " (ماري ، 98)

تكاد صفحات التاريخ النموذجية تشبه مقبرة الأمم. الكفر والفسق والقسوة هي الأسباب الرئيسية لتدمير وانقراض الأمم. يا له من مظهر رائع من مظاهر الانتقام الإلهي هو "السكيرات" للقبائل غير المؤمنة والقاسية. على الرغم من القرون الطويلة التي مرت ، تظهر بومبي اليوم علامات التحذير المتحجرة للأشخاص اللاأخلاقيين. إنها مثل الصور الظلية البشرية التي تصبح حيوانية روحيا! ..

تتكون هذه المظاهر النموذجية أيضًا من منحوتات بسيطة للعقول اللاواعية التي لا تستطيع رؤية حقيقتها ومشاهدة الأحداث بإحساس روحي.

اليوم ، البوم فقط هم الذين يفرحون لسدوم-عمورة ، مكان البؤساء القساة ، البذيئين والفاسقين ، والقصور الرائعة المنحوتة بالحجارة في عد وثمود ، الذين يعبدون أرواحهم ويعتقدون أن العالم هو العرش الذي يمنحهم دائمًا السعادة. !

المصدر: عثمان نوري طوبس ، سلسلة الأنبياء 1 ، منشورات إركام

#italy#pompeii#Vezüv#arkeoloji#tarihiyer#felaket#quran#kuranıkerim#vezüv yanardağı#yanardağ#lut kavmi#felaketten ders almak#homosexuality#lgbtq#great disasters#disaster#tarih#roma#UNESCO#europe#ibretlik#travel destinations#travel photography#travel#sapıklık#günah#fuhuş#zina#Allah#islamic

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pompeii Still Has Buried Secrets

The first major excavations in decades shed light on how ordinary citizens shopped and snacked—and where slaves slept.

— By Rebecca Mead | Published November 22, 2021 | Friday June 30, 2023

The ancient city was two miles in circumference. A third of it is still unexcavated. Illustration By Daniele Castellano

The journey from Naples to the ruins of Pompeii takes about half an hour on the Circumvesuviana, a train that rattles through a ribbon of land between the base of Mt. Vesuvius, on one side, and the Gulf of Naples, on the other. The area is built up, but when I travelled the route earlier this fall I could catch glimpses of the glittering sea behind apartment buildings. Occasionally, the mountainous coast across the bay came into sight, in the direction of the old Roman port of Misenum—where, in 79 A.D., the naval commander and prolific author Pliny the Elder watched Vesuvius erupt. Pliny, who led a rescue effort by sea, was killed by one of the volcano’s surges of gas and rock; his nephew, Pliny the Younger, provided the only surviving eyewitness account of the disaster. My view sometimes opened up in the opposite direction, toward the volcano, to reveal farmland or a stand of umbrella pines, their tall trunks giving way to billowing needle-covered branches. Pliny the Younger compared the shape of these trees to the volcanic eruption, with its column of smoke rising to a puffy cloud of ash that hovered, and then collapsed, burying a good part of what is now the Circumvesuviana’s route.

I got off at the stop called Pompeii Scavi—“the ruins of Pompeii”—and headed toward the modern gates that surround the ancient city. Before Pompeii was drowned in ash, it had a circumference of about two miles, enclosing an area of some hundred and seventy acres—a fifth the size of Central Park. Its population is estimated to have been about eleven thousand, roughly the same number as live in Battery Park City. After the ruins were rediscovered, in the mid-eighteenth century, formal excavations continued throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, with successive directors of the site exposing mansions, temples, baths, and, eventually, entire streets paved with volcanic rock. About a third of the ancient city has yet to be excavated, however; the consensus among scholars is that this remainder should be left for future archeologists, and their presumably more sophisticated technologies.

At some ancient Roman sites, such as nearby Herculaneum, unexcavated areas have been topped with contemporary buildings. But at Pompeii, once you walk inside the gates, you can almost block out the modern world: the ancient city is full of spectacular vistas, with the straight lines of its gridded streets leading to Vesuvius in the distance. And, every so often, a visitor comes across a street or an alleyway that dead-ends at a twenty-foot-high escarpment covered with scrubby grass. This is the boundary between Pompeii’s revealed past and its still buried one.

I had come to Pompeii to explore one such boundary, at the abrupt terminus of the Vicolo delle Nozze d’Argento—the Street of the Silver Wedding—in a corner of what archeologists have designated as Regio V, the city’s fifth region. For many years, the formal excavations stopped here, just past one of Pompeii’s grandest mansions: the House of the Silver Wedding, which was uncovered in the late nineteenth century and named, in 1893, in honor of the twenty-fifth wedding anniversary of the Italian monarch, Umberto I, and his wife, Margherita of Savoy. The spacious house, which is believed to have belonged to a Pompeiian bigwig named Lucius Albucius Celsus, included a salon fitted with a barrel-vaulted ceiling supported by columns of trompe-l’oeil porphyry, and an atrium, decorated with frescoes, that scholars regard as the finest of its kind in the city.

In the ruins of Pompeii, discovery has often gone hand in hand with destruction. Photograph by Michele Amoruso/Getty

I discovered that the mansion was closed for renovations: the clattering of workmen emanated from behind its high brick walls. But I wasn’t too disappointed—my interest was in what lay just beyond it, at a newly exposed crossroads. This is the site of the first significant excavations in decades of ruins embalmed by the 79 A.D. eruption. Since 2018, restoration work has been under way in Regio V to reshape and shore up the escarpment. Made up of impacted ash and lapilli, or pebbles of pumice, it had become increasingly vulnerable to collapse, especially after heavy rain. (When chunks of the escarpment broke off, artifacts and structures buried inside it were often obliterated.) Collapses aside, the weight of the unexcavated land in Regio V put the adjacent excavated area at risk by exerting immense pressure on exposed walls, some of which date to the first or second century B.C. The fragile escarpment threatened to make a ruin of the ruins.

Through a careful combination of archeology and engineering, the escarpment has been reshaped into a more gradual slope, with an exposed surface of rocky fragments secured by sturdy mesh. In order to lessen the gradient, it has been necessary to unearth a small area of previously buried streets and structures. In recent decades, most archeological excavations at Pompeii have been of layers that predated the first-century city—digging down to reveal, for example, that several of the town’s temples were built on structures that dated to the sixth century B.C. The new excavations in Regio V—conducted with the latest archeological methods, and an up-to-the-minute scholarly focus on such issues as class and gender—have yielded powerful insights into how Pompeii’s final residents lived and died. As Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, a professor emeritus at Cambridge University and an authority on the city, told me, “You only have to excavate a tiny amount in Pompeii to come up with dramatic discoveries. It’s always spectacular.”

My guide to the restorations of Regio V was Gabriel Zuchtriegel, who this past February was appointed the director of the Archeological Park of Pompeii. Forty years old, the German-born Zuchtriegel was formerly the director of the archeological site at Paestum, forty-odd miles south of Pompeii. As we walked around Regio V, he deftly navigated the uneven roads and talked about ongoing work: “We are not going to excavate just for the sake of excavating. It would be very problematic, and somehow irresponsible.” However, in the course of stabilizing this stretch of the boundary, in 2019, archeologists realized that they had come upon a structure worthy of a full excavation: a thermopolium, or snack bar, which was situated just across the street from the House of the Silver Wedding, as if the Frick mansion were cheek by jowl with a Gray’s Papaya.

The thermopolium, which opened to visitors in August, is a delight. A masonry counter is decorated with expertly rendered and still vivid images: a fanciful depiction of a sea nymph perched on the back of a seahorse; a trompe-l’oeil painting of two strangled ducks on a countertop, ready for the butcher’s knife; a fierce-looking dog on a leash. The unfaded colors—coral red for the webbed feet of the pitiful ducks, shades of copper and russet for the feathers of a buoyant cockerel that has yet to meet the ducks’ fate—are as eye-catching now as they would have been for passersby two millennia ago. (Today, they are protected from the elements and the sunlight by glass.) Another panel, bordered in black, is among Pompeii’s most self-referential art works: a representation of a snack bar, with the earthenware vessels known as amphorae stacked against a counter laden with pots of food. A figure—perhaps the snack bar’s proprietor—bustles in the background. The effect is similar to that of a diner owner who displays a blown-up selfie on the wall behind his cash register.

It turns out that few of Pompeii’s more straitened residents had a place at home to cook. “Rich people had kitchens in their houses, and banquet rooms and gardens,” Zuchtriegel told me, as we walked around the thermopolium. “But most inhabitants didn’t live in such places—they had small apartments, or even one-room flats. During the daytime, their place was a shop or a workshop, and at night the family would just close up the front and sleep there. And, when they could afford it, they would come here and have a warm meal, and take their plate and eat it on the street.”

Several tourists were peering through the glass into the thermopolium, as if they were hungry Pompeiians surveying the fare on offer. Zuchtriegel took a step back, toward a fountain; it would have provided fresh water for drinking, bathing, or cooling down. “It was life on the street, as today we can still see in Naples,” he said.

In 2018, a fresco of Cupid was discovered inside a sumptuous, newly excavated villa that has been named the House of the Garden. Photograph by Carlo Hermann/Getty

The thermopolium on the Vicolo delle Nozze d’Argento is far from unique—through the centuries, about eighty such establishments have been identified in Pompeii. But archeological science is now more evolved, Zuchtriegel told me, and at the new site scholars “can use modern technologies and methodologies to analyze what was inside the pots.” Fragments of duck bone were discovered in one of the containers, which are known as dolia, suggesting that the paintings of ducks served not just as decoration but as advertising. In other dolia, scholars found traces of cooked pig; what appears to be a stew of sheep, fish, and land snails; and crushed fava beans. A book of recipes attributed to Apicius, a celebrated Roman gourmet from the first century A.D., explains that “bean meal” can be used to clarify the color and flavor of wine.

These near-invisible remains of foodstuffs do not just provide information about the diet of Pompeii’s working classes. According to Sophie Hay, a British archeologist who has worked extensively at Pompeii, they also shed new light on the rhythms of civic life. “Up until this bar was excavated, people who study these things have gone around believing that the dolia contained only dry foodstuffs,” she told me. “There are Roman laws that said bars shouldn’t serve this kind of warm food, like hot meat, so we’ve been guided by the classical sources. Then, suddenly, there is this one bar that is definitely serving hot food. And is it the only bar in the Roman world to have done this? Unlikely. So that is huge.” A new story appears to be emerging from the lapilli: of a cunning bar owner who reckons that an authority from distant Rome isn’t likely to shut down his operation, or who is confident that the local authorities—the kind of Pompeiians who live in grand houses—will turn a blind eye to an illegal takeout business that keeps their less affluent neighbors fed with cheap but tasty fish-and-snail soup.

A decade or so ago, a different story about the walls of Pompeii prevailed—that they were crumbling from neglect and from the ineptitude of the site’s custodians. In late 2010, a stone building known as the House of the Gladiators imploded after heavy rains, severely damaging valuable frescoes inside. That disaster was followed by the collapse elsewhere in the city of several other walls. The media responded with a wave of alarmed stories; a typical headline, from National Geographic, asked, “pompeii is crumbling—can it be saved?” Italy’s President at the time, Giorgio Napolitano, declared the condition of Pompeii “a shame for Italy.” Pompeii was also afflicted with human corruption, with the Camorra—the Neapolitan Mafia—exerting influence over its custodial ranks and on the local businesses that catered to the 2.3 million tourists who visited annually. In 2012, the European Union intervened, underwriting the Great Pompeii Project, which offered a hundred and forty million dollars to Pompeii for conservation and restoration.

Despite this narrative of decline—much of which presumed that Italy was unwilling, or unable, to take care of its greatest asset, its cultural patrimony—the deterioration at Pompeii was inevitable. In some instances, what had given way and caused walls to crumble were not bricks laid by ancient Romans but concrete restorations carried out after the Second World War, during which Pompeii was assaulted by Allied forces who mistook corrugated-metal roofs covering excavation sites for Nazi barracks. Mary Beard, a professor at Cambridge University who is among the Anglophone world’s best-known interpreters of Roman history, told me, “The fate of Pompeii is quite mythologized, and has become a shorthand symbol for lots of other issues in heritage management. The P.R. used to be ‘Well, we can’t even keep Pompeii up, the place is falling down, it’s a terrible disgrace.’ Of course the place is falling down—it’s a ruin. There are totally unreasonable expectations of what Pompeii can be, and how it can be preserved.”

In 2014, the archeologist Massimo Osanna was appointed director of Pompeii, and he immediately launched an effort to restore confidence in the future of the ancient past. Sophie Hay told me, “I went to Pompeii shortly after Osanna got the job, and after five minutes on the site with him I got the idea of where he was going. He walked down the main street, the Via dell’Abbondanza, and there was all this horrible plastic netting in the doorways of buildings, the sort used on building sites to keep people out.” The site looked bandaged and bruised. “He was absolutely horrified—he called people over who were working there and said, ‘Can’t we just remove all of this?’ ” Osanna made Pompeii more inviting to visitors, and by 2019 their numbers had swollen to four million annually. That year, the House of the Gladiators reopened to the public after a reconstruction of its damaged frescoes, becoming a symbol not of Pompeii’s decline but of its renewed vitality.

Meanwhile, the charismatic Osanna won over the press by trumpeting discoveries resulting from the restoration work in Regio V. “He was absolutely brilliant at it,” Beard told me. “Without actually doing any major excavation, he gave a series of carefully timed bits of good news.” A headless male skeleton was discovered at a crossroads next to the House of the Silver Wedding, as was a huge block of stone, which lay, almost cartoonishly, right where the skull should have been. (The gruesome suggestion that the man had been decapitated was overturned by later analysis, which suggested that he had been suffocated by the pyroclastic flow—superheated rock, ash, and gases that rushed down Vesuvius’s flank.) In a house that had been buried beneath a swath of rough land, a fresco depicting the god Priapus weighing his oversized member on a scale was uncovered. The press hailed the new discoveries, and in 2020 Osanna was named director general of Italy’s state-run museums.

One day during my visit to Pompeii, I was wandering alone when I came upon the house with the Priapus, which is around the corner from the House of the Silver Wedding, on the Via del Vesuvio. The fresco of the erect god was in the entrance hall. Phallic imagery was common in Pompeii, and according to scholars such images were usually seen as symbols of good luck, rather than of ostentatious lewdness. It would have been interesting to know whether Priapus’ facial expression was one of pride or discomfort, but the fresco was missing the disk-shaped area where his head had once been. In a nearby room, a better-preserved painting depicted the mythical story of Leda and the Swan, in which Zeus assumes the form of a bird and copulates with a Spartan queen. After archeologists discovered the painting, in late 2018, and peeled back its curtain of gray, crumbly lapilli with scalpels, Osanna unveiled it to the public by describing the “pronounced sensuality” of Leda, who, he declared, was “welcoming the swan into her lap.” Examining the painting, I decided that Leda could just as easily be said to have an expression of trepidation, even panic.

Archeologists have since excavated the room to which the painting belonged: a small, richly decorated chamber featuring wall panels festooned with floral motifs. The lower half of the walls were painted in the rich red color indelibly associated with Pompeii. This look is consistent with what historians have classified as the city’s Fourth Style, which was prevalent in the years immediately before the cataclysm. The décor—now nearly two thousand years old—had been freshly installed when the volcano exploded.

In 2019, archeologists realized that they had come upon a structure worthy of a full excavation: a thermopolium, or snack bar, replete with still vivid paintings and amphorae. Photograph by Patrick Zachmann/Magnum

Since the remains of Pompeii and the other ancient Roman settlements inundated by Vesuvius first came to light, some three hundred years ago, discovery has often gone hand in hand with destruction. An eighteenth-century visitor to the site of Herculaneum described the methods used by the workmen under the command of Roque Joachim Alcubierre, the artillery engineer who had been appointed to oversee the excavation by the Bourbon monarchy then ruling the Kingdom of Naples. Unlike Pompeii, Herculaneum was not blanketed with ash and pumice; it was buried only by a series of pyroclastic flows, which hardened into a layer of deep rock, through which workmen could dig narrow tunnels only with great difficulty.

The workmen of that era, upon finding a mansion or other building, would extract any objects of obvious value, such as marble statues, bronze lamps, and decorative mosaics, without taking note of their location or of the architectural context. Because of the treacherous conditions—among them, inadequate light and air—workmen did not trouble to excavate doors. They broke through walls to get from one room to another, regardless of what decorations in the adjoining room they might be destroying. At Pompeii, it is not uncommon to see a wall with a hole smashed through it, including the wall perpendicular to the Leda and the Swan, where another painting has been partially destroyed—the handiwork of heedless laborers in centuries past, who dug down and rooted around through the ash and lapilli, which is shallower and easier to penetrate than the rock of Herculaneum.

Alcubierre operated with barbaric efficiency, especially when it came to wall paintings that his workers hacked off from their brick underpinnings. When a painting was deemed insufficiently different from those already unearthed, workmen pulverized it underground. These excavations were focussed on finding masterpieces to augment royal or aristocratic collections, rather than on discovering the mundane objects of everyday life—or material evidence of the complexities of Roman social structures. Today’s archeologists are happy to retrieve beautiful objects, but they are also intent on finding clues that will help them better understand how slavery functioned in the Roman world, or how women could acquire power.

Even the best-intentioned archeologists are only as good as their methodologies, and the primitive approaches of eighteenth-century pioneers are sometimes enough to make a modern observer shudder. In the seventeen-fifties, a large villa near Herculaneum was discovered, and archeologists were so transfixed by its handsome courtyards and garden that they barely registered the lumps of blackened charcoal that workmen were tossing aside. Many had crumbled before the lumps were belatedly identified as charred scrolls of papyrus. Did they record any lost works of antiquity? The first efforts to render the scrolls legible—by soaking them in mercury, or dunking them in boiling water—resulted in the scrolls turning to dust or mush. In a potent example of the advantage of waiting a few hundred years for technological advances to occur, scientists are now hoping to develop techniques for reading carbonized scrolls virtually, using microscopic-imaging tools devised for use in the drug and chemical industries.

Archeological techniques became more sophisticated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and at Pompeii there was a breathtaking innovation. Preserved in the compacted ash were numerous oddly shaped holes, and artisans made plaster casts of these cavities, thereby creating vivid representations of the city’s residents in their final moments: writhing helplessly on the ground, seeking to protect a loved one from the rain of ash. But Pompeii’s rising popularity as a tourist destination paradoxically contributed to the site’s erasure. Charles Dickens, who visited in 1844, writes, in “Little Dorrit,” about a family of tourists who made off with pocketed fragments—“morsels of tessellated pavement . . . like petrified minced veal.”

Less than a century after Dickens’s visit, much of the buried city had been unearthed, largely under the watch of Amedeo Maiuri, Pompeii’s director from 1924 to 1961. At the bidding of Mussolini, who sought to connect the grandeur of ancient Rome with the triumphs of contemporary Italy, Maiuri significantly accelerated the pace of excavation, exhuming residential areas of the city, and also the buildings that lined the Via dell’Abbondanza. The scale of activity made it hard to protect the site from weeds and looters. But experts praise Maiuri for having a scholarly interest not only in grand houses but also in the simpler structures—workshops, brothels, public latrines—that have increasingly become a focus of Pompeii scholars.

About a third of Pompeii has yet to be excavated; the consensus among scholars is that this remainder should be left for future archeologists, and their presumably more sophisticated technologies. Photograph by Patrick Zachmann/Magnum

Astonishingly, the new excavations in Regio V have prompted historians to reconsider one of the fundamental facts they thought they knew about Pompeii: the date of the eruption. In Pliny the Younger’s first-person account, he writes that the disaster occurred on August 24th. But, in a house down the street from the newly discovered thermopolium, archeologists have found a wall bearing the charcoal inscription of a date: the Roman equivalent of October 17th. Though the inscription doesn’t include a year, many scholars suspect that it dates from 79 A.D. Paul Roberts, a Pompeii scholar at the Ashmolean Museum, at Oxford University, told me, “Charcoal doesn’t tend to hang around too long. I am quite convinced that this was put on the wall not long before it was buried.” The inscription backs up a theory that another former director of Pompeii, Grete Stefani, proposed in 2006: that the correct eruption date was late October. Stefani based her argument on an array of archeological evidence, including the discovery of fruit that would have been out of season in August.

The charcoal marking is in a newly excavated residence that has been named the House of the Garden, because it once featured a lovely, verdant courtyard surrounded by a low wall decorated with images of plants. I visited it not long before the site closed for the day, when the declining sun was casting slanted light over Pompeii’s largely emptied streets, tinting the clouds beyond Vesuvius a gorgeous gold-pink. The inscription, at eye level on a wall, had a makeshift shield propped in front of it, protecting it from light damage. When a custodian removed the shield to show me the writing, I found it both indecipherable and disconcertingly familiar—it was the jotting of someone keeping track of housekeeping, just as I might use a whiteboard calendar to note a forthcoming appointment with the dentist.

The other rooms of the mansion were sumptuous, especially one in which a round fresco of a woman’s face—handsome, with deep-set eyes and a long, straight nose—looked out from a wall. Perhaps it was a portrait of the lady of the house. During the excavation of the mansion, a horrifying scene had been found: the skeletons of men, women, and children who had sought refuge in an inner room of the house, trying to shield themselves from the ash, the heat, and the gases spewed by the volcano. In the same building, archeologists discovered a box filled with amulets: figurines, phalluses, and engraved beads. In announcing the find, Massimo Osanna, ever the showman, had called it a “sorcerers’ treasure trove,” noting that the items contained no gold and therefore might have belonged to a servant or an enslaved person. Such items were commonly associated with women, Osanna had noted, and might have been worn as charms against bad luck.

Other scholars have warned that the suggestion of a sorcerer, or sorceress, verges on embellishment, given the paucity of material evidence. The contents of the box are now displayed in the Pompeii museum, with no mention of a sorcerer in the accompanying text. Yet, as the daylight dwindled in Pompeii, it was tempting to follow Osanna’s lead and imagine the scene: terrified members of the household clutching one another, their social differences levelled by disaster, as a Pompeiian who believed in dark magic made unavailing imprecations against unrelenting gods. My mystical vision evaporated, however, after the mansion’s custodian showed me another inscription, which had been scratched into the lintel of the house’s external doorway. It read “Leporis fellas”: “Leporis sucks dick.”

When Zuchtriegel, the current Pompeii director, was overseeing the site at Paestum, where three Greek temples have stood since the fifth and sixth centuries B.C., he made a number of innovations. Visitors were invited to watch ongoing excavations, and the storerooms inside the site’s museum were opened for public perusal.

Zuchtriegel told me that, in his leadership role at Pompeii, he intends to continue embracing new approaches. As we walked along the Via Stabiana, with its narrow, elevated sidewalks that helped Pompeii’s residents skirt the muck of its streets, he emphasized that archeology “is a field that is very much evolving, thanks to new discoveries and methodologies, but also thanks to new questions.” He went on, “Today, we have a much broader view of ancient society. Archeology started as a field dominated by male, upper-class, European, white scholars, and noblemen and connoisseurs, and this very much conditioned archeological research, and what people were interested in. Now, thanks to new perspectives—post-colonial studies, and gender studies, and feminism—we have a really different perspective on antiquity.”

Among the discoveries being examined through these new interpretative lenses was the first significant find announced under Zuchtriegel’s tenure: the remains of a man identified as Marcus Venerius Secundio. The tomb was found not in Regio V but east of Pompeii, where a necropolis had been unearthed close to one of the city gates. Unusually for an adult burial, the deceased had been embalmed rather than cremated, and the body was so well preserved that hair and even part of an ear were intact.

Secundio, Zuchtriegel explained, was a freedman, having formerly been a public slave—essentially, a municipal worker owned by the city. “Of course, nobody wanted to be a slave—it was very humiliating to be the property of someone,” Zuchtriegel said. “On the other hand, if you were a very poor freedman you were less well off than a household slave, some of whom were educators of the children of rich people, or secretaries who were part of the team that carried on the business of the owner.” It is unknown how Secundio gained his freedom, but historical records indicate that a public slave could raise funds to buy himself out of servitude. Evidently, Secundio ascended within Pompeiian society, becoming an augustalis, or a priest in the imperial cult—one of the few high-ranking positions open to men who were not freeborn. According to the funerary inscription on his tomb, Secundio was a patron of the arts, paying for ludi—musical or theatrical events that were performed in Latin and, significantly, in Greek. “This is the first time we have this direct evidence of Greek plays in Pompeii,” Zuchtriegel told me. Scholars had hypothesized, based on evidence in wall paintings and graffiti, that such events took place, but the inscription provides exciting confirmation.

In the decades before the eruption of Vesuvius, Zuchtriegel went on, there was a fashion in the Roman Empire for Greek-language performance, which was established by the emperor Nero, who ruled from 54 to 68 A.D., and who fancied himself not just an aficionado of Greek drama and song but also a performer. (According to the historian Suetonius, Nero “made his début” as a singer in Naples, so enjoying himself onstage that he ignored the rumblings of an earthquake in order to finish his performance.) Nero’s reputation as a tyrant has lately been reconsidered by scholars, and the evidence of Greek-language ludi in Pompeii buttresses the revised image of the Emperor as a popular leader; it also underscores the extent to which even a provincial city like Pompeii was influenced by the cultural fashions of the capital. “Pompeii and Campania had this really multicultural environment,” Zuchtriegel said. “People came from the Eastern Mediterranean, and there were the old Greek colonies at Naples and Paestum. We have evidence of Jewish people here at Pompeii.” (Graffiti found in the city cite individuals with the names Sarah, Martha, and Ephraim.)

Zuchtriegel told me that, as director, he intended to build on Osanna’s work, a decade after the rescue operation of the Great Pompeii Project was initiated. Other damaged fringes of Regio V are to be shored up, and new, limited excavations are to take place in another district, Regio IX. Similarly, work is continuing to protect areas outside the gates of Pompeii which have remained vulnerable to the incursion of illegal diggers. Scholars have made various new discoveries in these outlying areas, such as the remains of a horse that died during the eruption; the cavity formed in the rubble by the horse’s body has now been cast in plaster. Earlier this month, Zuchtriegel announced the discovery of slave quarters: a humble room, equipped with three wooden beds and amphorae stacked in a corner. “It is certainly one of the most exciting discoveries during my life as an archeologist, even without the presence of great ‘treasures,’ ” Zuchtriegel said. “The true treasure here is the human experience, in this case of the most vulnerable members of ancient society.”

But Zuchtriegel is likely to be less hyperbolic in his promotion than Osanna sometimes sought to be. I asked him how he could make preservation as exciting as discovery. He paused, then said, “Well, it doesn’t have to be so exciting. But we have to do it, anyway. I think what Massimo showed in these years is that excavation, research, and preservation are not opposites. As we see with the thermopolium, this was an excavation that had as a primary goal to preserve the conservation of the site.” He went on, “It’s very important to explain that archeology is very complex—from the excavation to the restoration to the exhibition, analysis, publication, and study. It’s important to make this transparent, and share it with the public, so that people understand that archeology is not about treasures and precious objects—that’s only a small part. It’s really about reconstructing the life of people in the distant past.”

Zuchtriegel and I wandered over to a section of the city that was closed to visitors. A custodian holding a bunch of keys seemed on the verge of warning us off when he recognized his relatively new boss. We then entered another of Pompeii’s grand mansions, the house of Maximus Obellius Firmus, one of the city’s most prominent citizens in the period before the eruption. This mansion also demonstrated the Pompeiian fascination with Greek culture, Zuchtriegel explained. An interior garden was surrounded by a peristyle—a rectangular perimeter of covered columns—which was popular in classical Greece. “There is an attempt to transform a traditional Roman house into a Greek space,” Zuchtriegel said. “You could be here in the middle of Pompeii, and feel like you were in a different space.”

He encouraged me to look upward. A restored rafter was serving as a perch for a few pigeons, whose droppings are especially damaging to wall paintings and stucco. Zuchtriegel had introduced a program whereby trained hawks sweep the ruins, frightening off the pigeons. “I did the same in Paestum,” he said. “You can reduce the pigeon population by eighty-five to ninety per cent!”

One of the challenges facing any director of Pompeii is coping with the tourists who flock, like pigeons, to explore the ruins. As Italy reopens for both domestic and international tourism, crowds are again lining up to enter Pompeii’s more celebrated locations, including the street-corner brothel in which partitioned chambers equipped with masonry beds are decorated with obscene wall paintings—an X-rated version of the dead ducks painted on the counter of the thermopolium in Regio V. A feminist interpretation of the practice of sex work, and its role in Pompeiian society, has not yet been incorporated at the site. An official guide who showed me around the city one day regaled me uncritically with the anecdote, found in the satires of the poet Juvenal, that Messalina, the wife of the emperor Claudius, liked to moonlight in a brothel—a story that Mary Beard and other contemporary critics view with a witheringly skeptical eye.

Counterintuitively, one of Zuchtriegel’s goals as director of Pompeii is to persuade visitors to go elsewhere—to the ruins of Herculaneum and to other, smaller sites that lie in the shadow of Vesuvius. One day, I got off the Circumvesuviana at Torre Annunziata Oplonti, and walked from the station for ten minutes through the town’s steep, scruffy streets to reach a site known as the Villa Poppaea—once a luxurious suburban domicile with views of the islands of Ischia and Capri. The villa gets its name from Nero’s second wife, Poppaea Sabina, whose family is believed to have come from Pompeii; it is thought to have been her country residence.

The site had just opened for the day, and I had it to myself as I descended to the 79 A.D. level and walked through a garden, where what looked like carbonized tree stumps remained in the ground. The villa, a sprawling complex of reception rooms and gardens and walkways which dates to the first century B.C., was stunning. First rediscovered at the end of the fifteenth century, when engineers were digging a canal, it was partially excavated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, then more fully exposed in the late twentieth century. Archeologists cleared away pumice and ash, and in rooms edging a garden they uncovered magnificent frescoes of the birds and plants that appear to have once flourished there. A large, decorated peristyle surrounded another garden: Greek-style living at its finest.

For all the interest offered by the new discoveries of the modes of everyday living at Pompeii—with its snail stews and its Greek theatrics—an empty, unfamiliar, luxurious villa retains an irresistible allure. The grandeur of the Villa Poppaea brought to mind images of an élite class of individuals who thought themselves safely removed from the grubbing hardships endured by the poor, but whose vast wealth provided them with no protection from a titanic natural disaster. At the eastern perimeter of the site, there was a feature to stir the envy of a Silicon Valley plutocrat: a swimming pool more than sixty metres in length. It was filled with weeds and gravel now, but in 79 A.D. it would have been edged by lavishly decorated salons and gardens—and it was easy to imagine Roman aristocrats lounging around a glittering pool, gazing across the sea with the dormant mountain at their backs, confident that the world was—and always would be—theirs to enjoy. ♦

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Natural and Geography: Mount Vesuvius - Italy:

Vesuvius or Mount Vesuvius (also known as Monte Vesuvio in Italian, ) is an Italian Somma-stratovolcano with an altitude of 1,281 meters, bordering the Bay of Naples, east of the city. It is the only volcano in continental Europe to have erupted in the last hundred years, its last eruption in 1944. Vesuvius consists of a large cone partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera, caused by the collapse of an earlier and originally much higher structure.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 destroyed the Roman cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis and Stabiae, as well as several other settlements. The eruption ejected a cloud of stones, ashes and volcanic gases to a height of 33 km (21 mi), erupting molten rock and pulverized pumice at the rate of 6×10 cubic meters (7.8×10 cu yd) per second. More than 1,000 people are thought to have died in the eruption, though the exact toll is unknown. The only surviving eyewitness account of the event consists of two letters by Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus.

Vesuvius was a name of the volcano in frequent use by the authors of the late Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. Its collateral forms were Vesaevus, Vesevus, Vesbius and Vesvius. Writers in ancient Greek used Οὐεσούιον or Οὐεσούιος. Many scholars since then have offered an etymology. As peoples of varying ethnicity and language occupied Campania in the Roman Iron Age, the etymology depends to a large degree on the presumption of what language was spoken there at the time. Naples was settled by Greeks, as the name Nea-polis, "New City", testifies. The Oscans, an Italic people, lived in the countryside. The Latins also competed for the occupation of Campania. Etruscan settlements were in the vicinity. Other peoples of unknown provenance are said to have been there at some time by various ancient authors.

Mount Vesuvius has erupted many times. The eruption in AD 79 was preceded by numerous others in prehistory, including at least three significantly larger ones, including the Avellino eruption around 1800 BC which engulfed several Bronze Age settlements. Since AD 79, the volcano has also erupted repeatedly, in 172, 203, 222, possibly in 303, 379, 472, 512, 536, 685, 787, around 860, around 900, 968, 991, 999, 1006, 1037, 1049, around 1073, 1139, 1150, and there may have been eruptions since then. The volcano erupted again in 1631, six times in the 18th century , eight times in the 19th century, and in 1906, 1929 and 1944. There have been no eruptions since 1944, and none of the eruptions after AD 79 were as large or destructive as the Pompeian one.

Vesuvius has a long historic and literary tradition. It was considered a divinity of the Genius type at the time of the eruption of AD 79: it appears under the inscribed name Vesuvius as a serpent in the decorative frescos of many lararia, or household shrines, surviving from Pompeii. An inscription from Capua to IOVI VESVVIO indicates that he was worshipped as a power of Jupiter; that is, Jupiter Vesuvius.

The Romans regarded Mount Vesuvius to be devoted to Hercules. The historian Diodorus Siculus relates a tradition that Hercules, in the performance of his labors, passed through the country of nearby Cumae on his way to Sicily and found there a place called "the Phlegraean Plain" (Φλεγραῖον πεδίον, "plain of fire"), "from a hill which anciently vomited out fire ... now called Vesuvius." It was inhabited by bandits, "the sons of the Earth," who were giants. With the assistance of the gods, he pacified the region and went on. The facts behind the tradition, if any, remain unknown, as does whether Herculaneum was named after it. An epigram by the poet Martial in 88 AD suggests that both Venus, patroness of Pompeii, and Hercules were worshipped in the region devastated by the eruption of 79.

#super wings#super wings cultural#cultural geographic#geography#cultural history#historical geography

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worthy Brief - February 12, 2024

Focus on eternal rewards!

1 Timothy 6:6-10 But godliness with contentment is great gain. For we brought nothing into this world, and it is certain we can carry nothing out. And having food and raiment let us be therewith content. But they that will be rich fall into temptation and a snare, and into many foolish and hurtful lusts, which drown men in destruction and perdition. For the love of money is the root of all evil: which while some coveted after, they have erred from the faith, and pierced themselves through with many sorrows.

Last week, three students won the top award for using AI to translate Pompeii scrolls, discovered by an 18th-century farmer. The scroll, central to the AI contest, was named after Herculaneum, a Roman town destroyed by the Vesuvius eruption. These texts, trapped in carbon for 2,000 years, were preserved under the debris that buried Julius Caesar's father-in-law's villa.

Pompeii was a flourishing city in Southern Italy until 79 AD. Suddenly, for two days Mt. Vesuvius erupted and completely destroyed Pompeii in all its pomp. The city was covered in meters of ash and pumice for 1700 years until it was accidentally discovered in 1748. When archaeologists began excavations in 1910 they uncovered a petrified woman clutching some of the finest jewelry ever recovered from the ancient world. She was apparently attempting to flee the doomed city, and in her haste, holding desperately onto her valuable possessions –- she lost her life.

During its time Pompeii was a magnificent city, yet its destiny was destruction by a nearby volcano –- and so it is with our world today. There's so much beauty on our planet earth –- yet its destiny is certain! The day is soon coming when it's elements will be destroyed with fire, the earth and everything in it, laid bare, [2 Peter 3:10] –- and our earthly possessions will not come with us into glory, (only what we have done with them).

As the Apostle Paul said, we came into this world with nothing – and when we leave this world, we take nothing with us. We can make the mistake of holding too dearly onto our earthly possessions, making them our "treasure", (rather than storing treasure where moth and rust do not corrode etc.) – but this is a costly error, as illustrated by our "petrified lady". Instead, let's remind ourselves that we are stewards of God's possessions, responsible to use them with His interests in mind, to further His Kingdom with the things He has entrusted to us.

With so much work to be done, let's never allow our earthly possessions to petrify us with greed or fear thus preventing the eternal work we were preordained for, and stealing our eternal rewards.

Your family in the Lord with much agape love,

George, Baht Rivka, Obadiah and Elianna (Dallas, TX)

(Tulsa, Oklahoma)

Editor's Note: During this war, we have been live blogging throughout the day -- sometimes minute by minute on our Telegram channel. - https://t.me/worthywatch/ Be sure to check it out!

Editor's Note: We are planning our Winter Tour so if you would like us to minister at your congregation, home fellowship, or Israel focused event, be sure to let us know ASAP. You can send an email to george [ @ ] worthyministries.com for more information.

0 notes

Text

The Destructive Atmosphere of Volcanoes: Understanding the Hazards of Mount Vesuvius and Beyond

Mount Vesuvius is one of the most infamous and active volcanoes in the world. The mountain is located about 9 km (5.6 mi) east of Naples and is best known for its eruption in AD 79 that destroyed the Roman cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis and Stabiae.

Geologically speaking, Mount Vesuvius, or more correctly, the Somma-Vesuvius complex, is about 400,000 years old, as dating of lava…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Archaeologists Uncover Two New Pompeii Victims Killed by Earthquake

Archaeologists working at Pompeii have found two new victims that they say were killed by an earthquake that accompanied the volcanic eruption of 79 AD.

The Italian city may be most closely associated with the destruction wrought by the eruption of Vesuvius, but these two men were in fact killed by walls knocked down by a simultaneous earthquake, according to the official Pompeii archaeological site.

“Part of the south wall of the room collapsed, crushing one of the men whose raised arm offers a tragic image of his vain attempt to protect himself from the falling masonry,” reads a press release on Tuesday.

“The conditions of the west wall demonstrate the tremendous force of the earthquakes that took place at the same time as the eruption: the entire upper section was detached and fell into the room, crushing and burying the other individual,” it continues.

The pair, who were at least 55 years old, were found during excavations of the Insula of the House of the Chaste Lovers during work to improve the safety of the building.

They were found lying in a utility room where they had sought refuge, and were killed by multiple traumas as parts of the building collapse.

Archaeologists found organic matter, which they believe to be a bundle of fabric, as well as glass paste, which is thought to be the beads of a necklace and six coins. The team also found an amphora leaning against a wall and a number of vessels, bowls and jugs.

In an adjoining room, archaeologists found a stone kitchen counter covered in powdered lime, which they say suggests that building work was being undertaken nearby at the time of the eruption.

The discovery “shows how much there is still to discover about the terrible eruption of AD 79 and confirms the necessity of continuing scientific investigation and excavations,” said Italy’s Minister of Culture Gennaro Sangiuliano in the release.

“Pompeii is an immense archaeological laboratory that has regained vigour in recent years, astonishing the world with the continuous discoveries brought to light and demonstrating Italian excellence in this sector,” he added.

Details of the excavation were published in the E-Journal of Pompeii.

The Roman city of Pompeii was buried under meters of pumice and ash in the calamitous eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Archaeologists have uncovered only around two thirds of the 66-hectare (163 acres) site since excavations began 250 years ago.

By Jack Guy.

#Archaeologists Uncover Two New Pompeii Victims Killed by Earthquake#Pompeii#Mount Vesuvius#ancient grave#ancient tomb#skeleton#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

OCPL: February 23 — 7 p.m.: The Tragedy of Pompeii

Before Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD, Pompeii was a thriving, dynamic, and international city whose story intertwined with the key events of Roman history. In this course, we will consider the complex past of Pompeii before and after its cataclysmic destruction. Using unique archeological sources from graffiti to sewage, we will explore the very real people who lived, loved, and died in the most well-preserved of ancient cities.

Instructor: Dr. Laura Michele Diener

Watch LIVE on Facebook

Watch LIVE on YouTube

Thurs. March 2: Field Trip

For those students announced on Feb. 23, please meet at 7 PM at the Carnegie Museum Of Natural History in Pittsburgh for a tour of the Ancient Egypt Exhibit. Note: You must arrange your own transportation.

FINALE: March 9 at 7 PM

Rome Part 2-Rise & Fall of Empire

By the time of Julius Caesar was murdered during the Ides of March, the Romans had been living through almost a century of civil wars marked by massacres, betrayal, and upheaval. During the first century BC, the Republic had begun to break down under the pressures of expansion and ambition. In this class, we will cover the cataclysmic end of the Republic and the formation of imperial rule under Emperor Augustus and his successors. Despite its blood-soaked beginnings, the Empire ushered in a golden age of Roman peace and prosperity known as the Pax Romana.

Instructor: Dr. Laura Michele Diener

Facebook Event

Recommended Reading for the series:

- Aegean Bronze Age Art: Meaning in the Making by Karl Knappett

- Antony and Cleopatra by Adrian Goldsworthy

- Creators, Conquerors, and Citizens by Robin Waterfield

- A History of Ancient Greece in 50 Lives by David Stuttard

- The Odyssey by Homer, Emily Wilson's Translation

- Phillip and Alexander: Kings and Conquerors by Adrian Goldsworthy

- Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt by Barbara Mertz

- SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome by Mary Beard

- When Women Ruled the World by Kara CooneyNovels:

- Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

- Circe by Madeline Miller

- Mythos by Stephen FryNote: Search the OCPL's Catlog HERE.The Library is in the process of acquiring as many of the above titles as possible. If you see a book above in our catalog that you'd like to check out that's on hold, please send us an email.

The new People's University series being offered at the Ohio County Public Library in Wheeling on Thursday evenings beginning January 5 will explore the ancient world, including Egypt, Greece, and Rome. The eight classes begin at 7 pm in the Library's auditorium through February 23. The classes will also be livestreamed on the Library's People's University Facebook and People's University YouTube channels.

What is the People's University?

In 1951, the Ohio County Public Library's head librarian, Virginia Ebeling, referenced British historian Thomas Carlyle, who said, “the public library is a People’s University,” when she initiated a new adult education program with that name. Miss Ebeling charged the Library with the responsibility of reaching “as many people in the community as possible.” In keeping with that tradition of public libraries as sanctuaries of free learning for all people, the Ohio County Public Library revived the series in 2010.

The People’s University is a free program for adults who wish to continue their education in the liberal arts. It features courses—taught by experts in each subject—that enable patrons to pursue their goal of lifelong learning in classic subjects such as history, philosophy, and literature. Patrons may attend as many classes as they wish. There are no tests of other requirements and all programs are free and open to the public.

For more information about the People's University Ancient History or other Library programs, call 304-232-0244 or stop by the Reference Desk.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Detailing a disastrous autumn day in ancient Italy

Detailing a disastrous autumn day in ancient Italy

Volcanic eruptions evoke images of lava, fire, and destruction; however, this is not always the case. The Plinian eruption of Mount Vesuvius around 4,000 years ago—2,000 years before the one that buried the Roman city of Pompeii— left a remarkably intact glimpse into Early Bronze Age village life in the Campania region of Southern Italy.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Enjoy Naples Shore Excursions Independently

What to do when you arrive on a cruise ship or flight or Train in Naples? It is a common question travelers ask when they book a Naples shore excursion in Italy. With shore excursions from Naples International Airport or Naples cruise port, you have different options to explore Naples and the Southern Italian region of Campania. It may be a bus, a train, or a public transfer. But the best opportunity to do it is hiring a limousine and enjoy Naples shore excursions independently. It will give you freedom and flexibility for your Naples shore excursions, and you will do it at more favorable rates.

While Naples is one of the most famous cities in Italy, most vacationers head to its more famous and glamorous neighbor's, such as the fabulous ancient ruins of Pompeii and the glorious Amalfi Coast. So let's discuss a few points of interest.

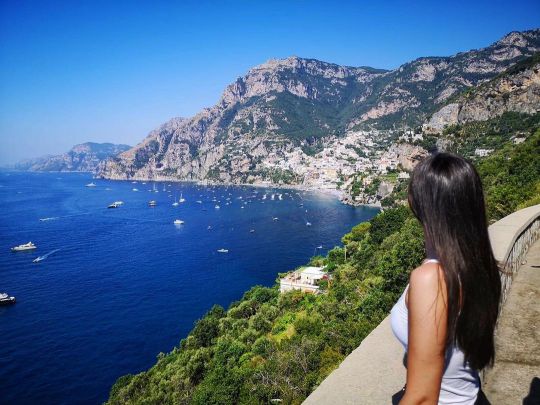

Positano

Resting on the slopes of cliffs that make up the unique coast of Amalfi, the seaside town of Positano is indeed the jewel of the Amalfi Coast. One of the most elegant coastal resort towns along the Amalfi Coast, Positano is a much sought-after destination for jet setters, cruisers, and travelers wishing to experience this iconic village. So it's no wonder Amalfi Coast is a must in Naples shore excursions, and it is the most popular place in the region.

Sorrento

Sorrento is a vibrant historic centre with lovely squares and narrow alleys lined with landmark buildings. It is a rich historic center overlooking the Bay of Naples. It boasts splendid yet sweeping water views of the Sorrentine Peninsula. Your Naples shore excursions make you wander through the city while taking you to the unique marquetry shops, sample the

Sorrentine lemon liquor, and savour the local flavor's at traditional restaurants.

Pompeii

Explore the ruins of the ancient bustling city of Pompeii that was tragically destroyed by Mount Vesuvius' violent eruption in 79 AD. Stroll along the storied streets, wander through well-preserved buildings buried under Mount Vesuvius' volcanic ash for centuries and admire ancient frescoes, mosaics, and architectural elements of everyday life in this ancient city.

Herculaneum

Herculaneum is another smaller ancient Roman-era city that suffered the same destructive fate as Pompeii. Rich in archaeological discoveries, intact buildings, marble floors, mosaics, and statues make this UNESCO World Heritage site a great site to visit.

Mount Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius is one of the most famous volcanoes in the world and one of the two active volcanoes in Continental Europe. Mount Vesuvius National Park is dotted with wineries and farms, but visiting the crater is what makes this mountain exciting. From the crater's rim, visitors are rewarded with an extraordinary view of Naples, Pompeii, and the shimmery bay on the horizon.

Plan your Naples Shore Excursion with Naples Limousine Services

It is recommended to plan what to do when you arrive at the airport or train terminal, or cruise port in Naples. Hire a limousine service in advance, ensuring you have a great Naples shore excursion ahead. It is an excellent option for most independent-minded travelers who prefer private tours. Please call Naples Limousine Service to book a safe & comfortable ground transfer today!

0 notes