Text

WILLIAM GEORGE 'BILL' BONIN

THE FREEWAY KILLER

Born: January 8, 1947. Willimantic, Connecticut, USA

Died: 12:13 a.m. February 23, 1996 (aged 49) Executed by Lethal Injection. San Quentin, California, USA

Religion: Catholic

I.Q: 121

Psychiatric Diagnosis: Bipolar Disorder

Physical Diagnosis: substantial damage to prefrontal cortex may have reduced his ability to hold back violent impulses. Extensive scar tissue noted on head and buttocks.

Criminal Charges:

16 counts of murder

5 counts of kidnapping

5 counts of sodomy

1 count of oral copulation

1 count of oral copulation

1 count of rape

1 count of forcible copulation of a minor

1 count of attempted kidnapping

11 counts of robbery

1 count of mayhem

Span of killings: May 28, 1979 – June 2, 1980

Country: USA State: California

Date apprehended: June 11, 1980

Final Meal: Two large pepperoni and sausage pizzas, three pints of coffee ice cream and three six-packs of regular Coca Cola.

Identified Victims:

1. Thomas Lundgren (13): May 28, 1979

2. Mark Shelton (17): August 4, 1979

3. Markus Grabs (17): August 5, 1979

4. Donald Ray Hyden (15): August 27, 1979

5. David Murillo (17): September 9, 1979

6. Robert Wirostek (18): September 17, 1979

7. John Doe (19–25): c. November 1, 1979

8. Frank Dennis Fox (17): November 30, 1979

9. John Kilpatrick (15): December 10, 1979

10. Michael McDonald (16): January 1, 1980

11. Charles Miranda (15): February 3, 1980

12. James Macabe (12): February 3, 1980

13. Ronald Gatlin (18): March 14, 1980

14. Glenn Barker (14): March 21, 1980

15. Russell Rugh (15): March 21, 1980

16. Harry Todd Turner (15): March 24, 1980

17. Steven Wood (16): April 10, 1980

18. Darin Lee Kendrick (19): April 29, 1980

19. Lawrence Sharp (17): May 17, 1980

20. Sean King (14): May 19, 1980

21. Steven Wells (18): June 2, 1980

▶️ The Freeway Killer (documentary)

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#William Bonin#bill Bonin#Freeway Killers#Freed to kill again

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

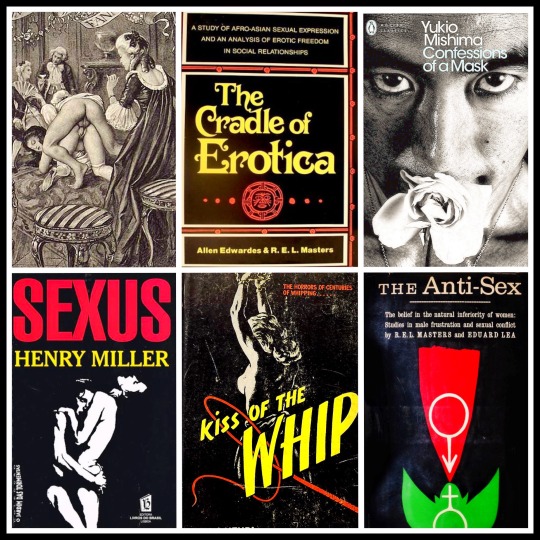

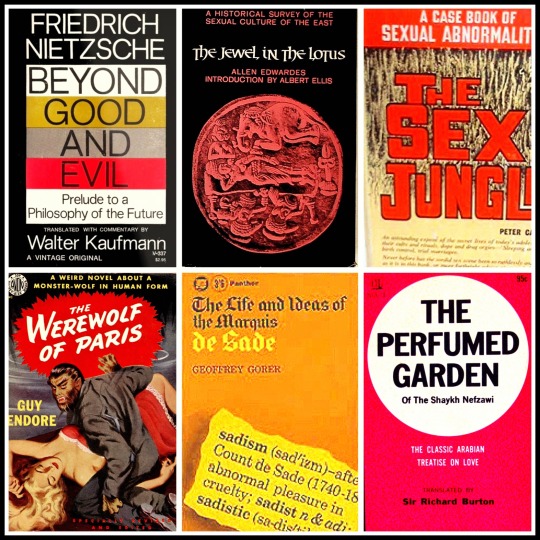

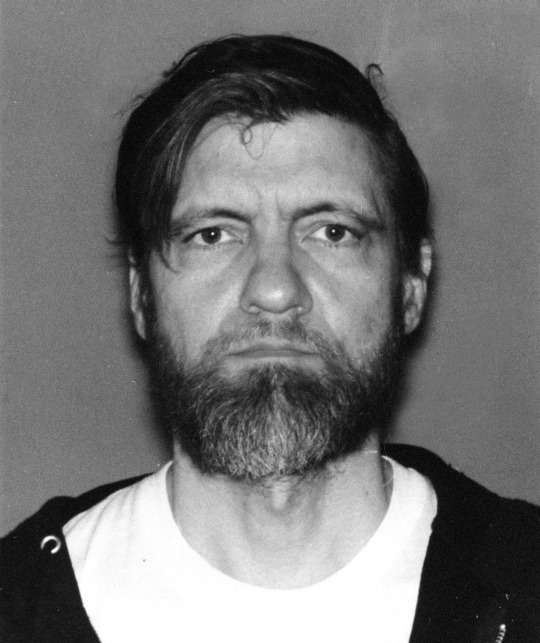

Ian Brady: Literary Indulgences

All men are divided into ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary.’ Ordinary men live in submission and don't have the right to transgress the law, because, don’t you see, they are ordinary. But extraordinary men have a right to commit any crime and to transgress the law in any way, just because they are extraordinary

)c(

There are certain persons who can... that is, not precisely are able to, but have a perfect right to commit breaches of morality and crimes, and that the law is not for them.

)c(

but never try to answer for what is between a husband and his wife, or a lover and his mistress. There is always one little corner which remains hidden from all the world, and is known only to the two of them. Crime and Punishment Fyodor Dostoevsky

Ian Brady's childhood was one of loss and instability. His birth was eclipsed by the death of his father which left his mother unable to care for him. She worked as a waitress for hours a day, but couldn't afford a babysitter to watch her new born. This meant she'd be forced to leave Ian home alone, and after several months she decided to give her son away. With the truth of his identity protected by lies, young Ian struggled to trust authority and had no respect for the rules. He was nicknamed Dracula, for his solemn appearance and love of horror movies. His praise of Hitler didn't win him any friends and he'd learn to survive as an outsider. He despised weak people and loved power. He looked down on society and called them all maggots. Ian became his own god and would create his own kingdom. Without the restraint of common law or morality, Brady was free to act on all his sordid desires.

The discovery of Brady's photography, literature and music provided an insight into his sadistic world. There seemed to be a code between the two killers. Photos of Myra posing on the moors, led police to the burial sites of 3 victims. Were they taken as trophy pics to gloat of their conquests or markers for murder locations ?

Before each murder, Brady would buy Myra a new pop record. This was his way of telling her, he had the urge to kill again.

▶️ Theme from 'The Hill' movie

▶️ Theme from The Legion’s Last Patrol: Ken Thorne and His Orchestra.

▶️ 24 Hours From Tulsa: Gene Pitney

▶️ It’s Over: Roy Orbison

▶️ Girl Don’t Come: Sandie Shaw

▶️ Joan Baez: It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#moors murders#david smith#Ian Brady#marquis de sade#frederick nietzsche#crime and punishment#literature#fyodor dostoevsky#compulsion#mein kampf#myra hindley#joan baez#sandie shaw

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

David Smith talks about Ian Brady & Myra Hindley )c(

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#documentary#youtube#moors murders#David smith#Ian Brady#Myra hindley#manchester

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

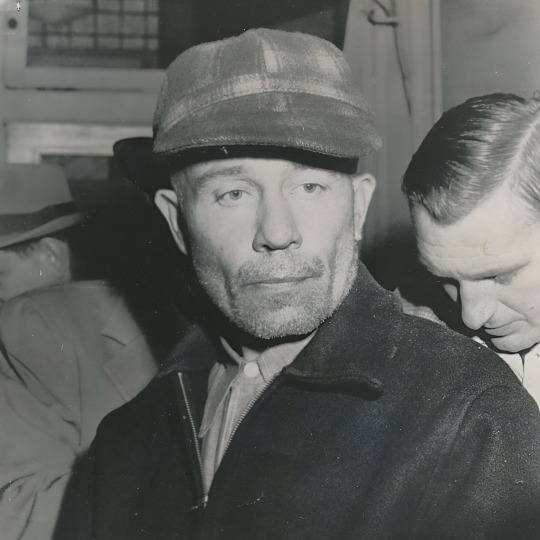

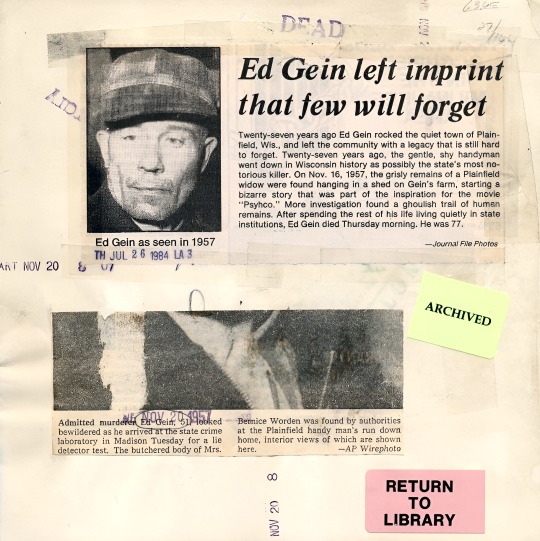

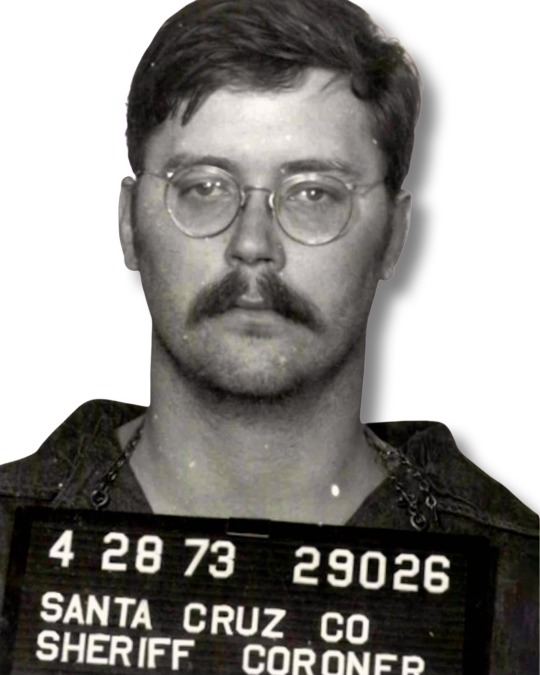

ED GEIN

)c(

The depths of Ed Gein's depravity sank beneath the morals of civilized society. His deranged thoughts fed a dark desire, that motivated him to commit unimaginable crimes.

What began as casual Friday night grave robbing soon turned into murder. Gein needed freshly deceased female bodies to create his Corpse-couture. In a town with only 503 residents, freshly deceased ladies were limited. As a result of these dry spells, Gein had no choice but to kill. The laborious task of perfecting his artistry gave Ed Geins' life a sense of purpose and connection.

Gein transformed the family home into a palace of death. He covered wastebaskets and chair seats in a patchwork of hand stitched human skin; Female skulls adorned his bedposts while others were sawn in half and used as bowls. A pair of lips made a window shade drawstring; A collection of noses which he saved for a rainy day and cutlery made from bones. Gein dressed his naked body in skin garments that symbolized female beauty. A corset made from freshly skinned torso empowered the once emasculated virgin. In his new skin lady Gein was born. He assumed the role of 'woman of the house'. Death made it possible for Ed Gein to connect to the world. He gave life to dead bodies by dressing in their skin. For the first time in his life, he felt a sense of power and control.

He worshipped and feared his dominant mother, a religious tyrant who condemned the young Gein as a sinner in his masculine form. After his mothers death, Gein was distraught. He lacked the strength and discipline to live in the world without his mothers control. Increasingly, he craved her feminine power.

Ed's farming upbringing gave him some useful skills in butchery. He'd also dabbled in taxidermy when other kids were playing sport. With his lazy eye, speech impediment and antisocial family, young Ed was regularly picked on at school.

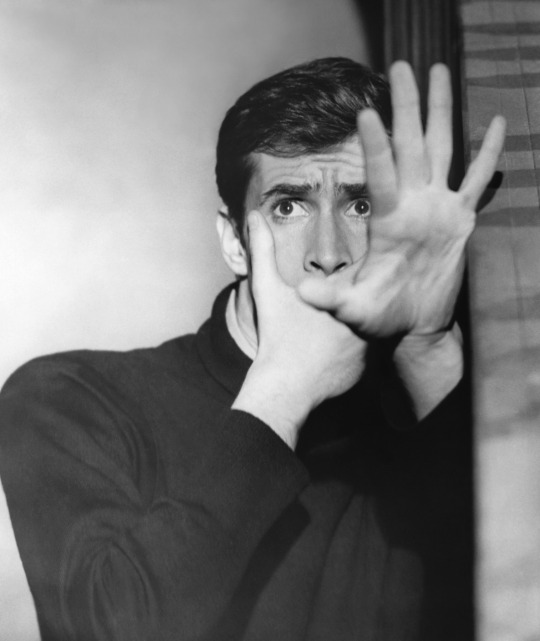

The gruesome nature of Ed Gein's crimes not only captured the collective fear of the public but also created a blueprint for three of the most unattractive antagonists in American cinema history: Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" (1960) was directly inspired by Gein's overbearing relationship with his mother and his habit of dressing in women’s clothing. He kind've became the poster boy for psychopaths; Leatherface in “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” (1974) wore the skin of his victims, but stuck to more traditional gender roles; Buffalo Bill in “The Silence of the Lambs” (1991) is a composite of several real-life murderers, including Gein.

Locals in small town Plainfield described Gein as a quiet man who may have been a little odd, but harmless. They regarded Gein as one of their own. He had dined at their tables and even babysat their children. But this was well before they knew about his fetish for pelt-belts.

The case of Ed Gein significantly contributed to Criminal Studies & Understanding of Psychopathy: Although Gein was not a diagnosed psychopath, his case has illuminated aspects of disturbed behavior, contributing to our understanding of mental disorders in the context of criminality. For instance, Gein's unhealthy relationship with his mother has influenced theories regarding the impact of familial relations on disturbing behavior. His obsession with female body parts also led specialists to understand more about fetishism and necrophilia.

Additionally, Ed Gein's case promoted the development of FBI's criminal profiling methods. Robert Ressler, a former FBI agent and one of the pioneers in this field, especially used Gein's case, among others, to understand the motivations and behavior of serial killers.

Bx

Ed Gein-The Lost Tapes 2023

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#documentary#Ed Gein#Psycho#macabre#horror#texas chainsaw massacre#silence of the lambs#leatherface

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

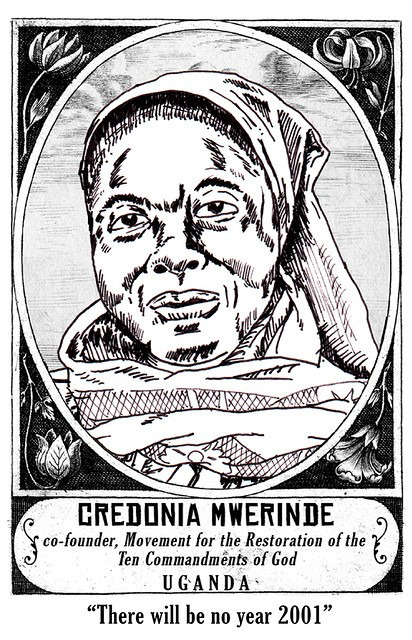

The Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God

was a religious cult that sprouted in Uganda during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The group was led by Credonia Mwerinde (a former prostitute) Joseph Kibweteere, Bee Tait, and Ursula Komuhangi, whom all professed visions of the Virgin Mary and the impending apocalypse.

The cult had a following mainly composed of disenchanted Catholics, Seventh-day Adventists, and other Christian denominations alongside some converts from other faiths. Initially, followers were attracted by the core belief of the group, which was a strict adherence to the Ten Commandments, embodied in the group's name.

This strict adherence was taken to an extreme where breaking of any commandment was strictly criticized, requiring members to communicate mainly through signs and the use of formal codes. It was believed this hard-lined approach would help followers avoid damnation come the apocalypse.

Notably, the leaders prophesied that the world would end on January 1, 2000. However, when this prophecy failed, an alternative date of March 17, 2000, was given. This was claimed to be the day God's wrath would consume the world, sparing only the cult members.

Their teachings included end-of-day prophecies, abstaining from sex to prepare for the end of times, fasting, and the banning of soap. The group's leaders discouraged speaking, claiming that it led to sin, and consequently, the followers communicated primarily through sign language.

The group came to global attention when, on the prophesied date of March 17, 2000, a fire broke out in the group's main church in Kanungu. Approximately 778 members of the cult died in the inferno, which is believed to have been a mass murder ignited by the cult leaders. This event followed the murder of various members across multiple cult properties.

BBC link

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#cults#movement of the restoration of the ten commandments of god#credonia#uganda

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

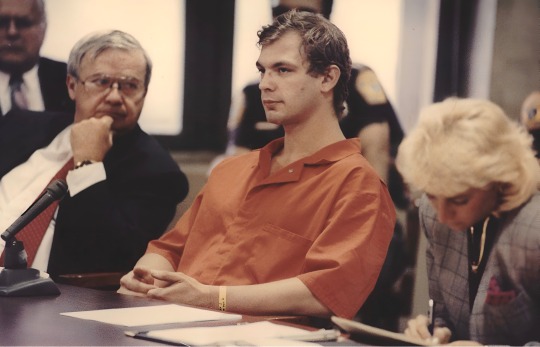

The Case of Jeffrey Dahmer:

Sexual Serial Homicide from a Neuropsychiatric Developmental Perspective

J. Arturo Silva, M.D

Michelle M. Ferrari, M.D

Gregory B. Leong, M.D

)c(

"Sexual serial homicidal behavior has received considerable attention during the last three decades. Substantial progress has been made in the development of methods aimed at identifying and apprehending individuals who exhibit these behaviors. In spite of these advances, the origins of sexual serial killing behavior remain for the most part unknown. In this article we propose a biopsychosocial psychiatric model for un- derstanding the origins of sexual serial homicidal behavior from both neuropsychiatric and developmental perspectives, using the case of convicted serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer as the focal point. We propose that his homicidal behavior was intrinsically associated with autistic spectrum psy- chopathology, specifically Asperger’s disorder. The relationship of Asperger’s disorder to other psychopathology and to his homicidal behavior is explored. We discuss potential implications of the proposed model for the future study of the causes of sexual serial homicidal criminal."

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#killer queen#jeff dahmer#jeffery dahmer#aspergers#psychology#criminal psychology#dahmer trial#gay true crime#Arturo silva#thesis#forensics#mental health#Jeffrey Dahmer

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

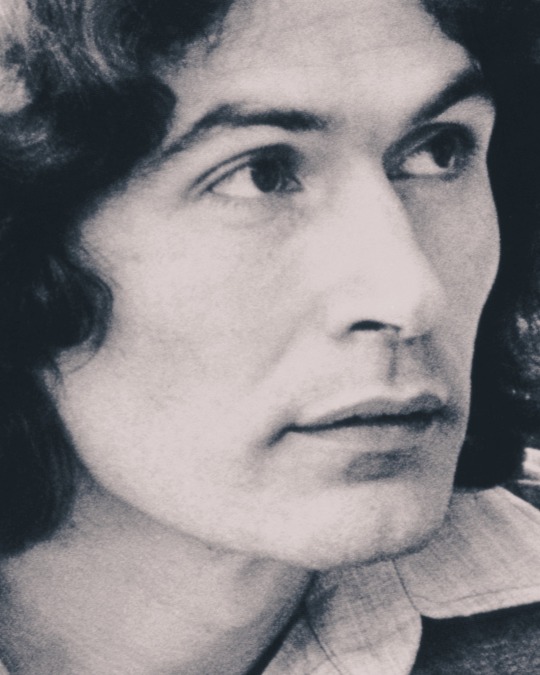

Myra Hindley

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

True Crime Essentials: Part One

)c(

A personal selection of my favourite True crime documentaries

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#documentary#cults#ed kemper#john wayne gacy#jeffery dahmer#tell me who I am#netflix#true crime series#killer queen#ted bundy#Lawrence Bittaker#night stalker#capturing the Friedmans#the imposter#Jonestown#Jim Jones#Youtube#la vida loca#maitredj#Brandon Marlo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

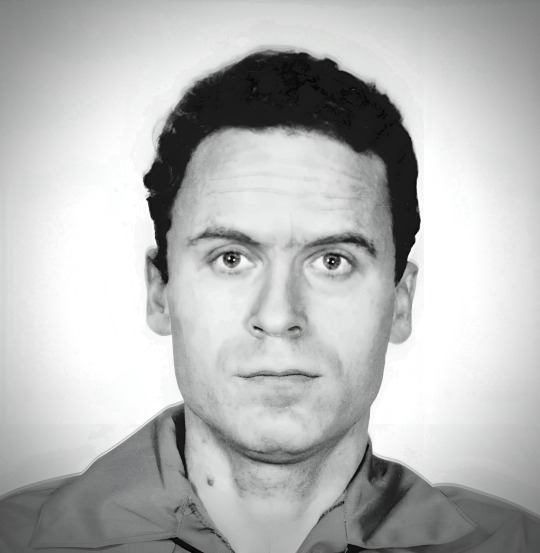

Ethics: Discovering Right and Wrong

)c(

On the basis of subjectivism, Adolf Hitler and the serial murderer Ted Bundy could be considered as moral as Gandhi, as long as each lived by his own standards whatever those might be. Witness the following paraphrase of a tape-recorded conversation between Ted Bundy and one of his victims, in which Bundy justifies his murder:

Then I learned that all moral judgments are 'value judgments', that all value judgments are subjective, and that none can be proved to be either "right" or "wrong." I even read somewhere that the Chief Justice of the United States had written that the American Constitution expressed nothing more than collective value judgments. Believe it or not, I figured out for myself, what apparently the Chief Justice couldn't figure out for himself: That if the rationality of one value judgment was zero, multiplying it by millions would not make it one whit more rational. Nor is there a "reason" to obey the law for any-one, like myself, who has the boldness, daring and strength of character to throw off its shackles. I discovered that to become truly free, truly unfettered, I had to become truly uninhibited. And I quickly discovered that the greatest obstacle to my freedom, the greatest block and limitation to it, consists in the insupportable "value judgment", that I was bound to respect the rights of others. I asked myself, who were these "others"? Other human beings, with human rights? Why is it more wrong to kill a human animal than any other animal, a pig or a sheep or a steer? Is your life more to you than a hog's life to a hog?

Why should I be willing to sacrifice my pleasure more for the one than for the other? Surely, you would not, in this age of scientific enlight-enment, declare that God or nature has marked some pleasures as "moral" or "good" and others as "immoral" or "bad"? In any case, let me assure you, my dear young lady, that there is absolutely no comparison between the pleasure I might take in eating ham and the pleasure I anticipate in raping and murdering you. That is the honest conclusion to which my education has led me after the most conscientious examination of my spontaneous and uninhibited self.

)c(

Notions of good and bad or right and wrong cease to have evaluative meaning beyond the individual. We might be revulsed by Bundy's views, but that is just a matter of taste.

)c(

Ethics: Discovering Right and Wrong (8th Edition)

LOUIS P. POJMAN Late of the United States Military Academy, West Point

JAMES FIESER University of Tennessee, Martin

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#ted bundy#Theodore Bundy#killer confessions#Ethics: Discovering Right and Wrong#LOUIS P. POJMAN#JAMES FIESER#subjective relativism#value Judgments

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The abandoned house of serial killer Steven Brian Pennell, in Delaware

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#documentary#delaware#1-40 killer#highway killer#Steven Brian Pennell#Steven Pennell#Route 40 killer#Shirley A. Ellis#creepy dolls#abandoned house#ghost house#house of horrors

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

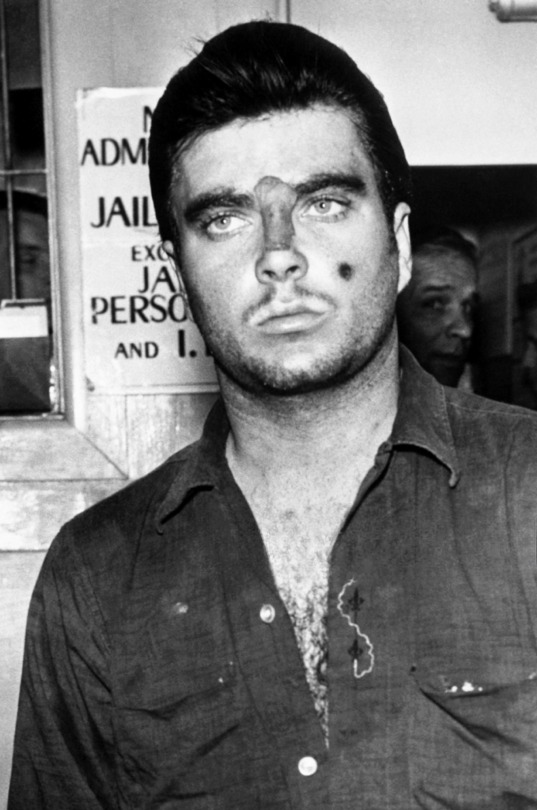

Gary Gilmore & The Death Penalty

C)(C

GARY GILMORE was the first person to be executed in the USA after the death penalty was reinstated in 1976. At the time there were 358 other American prisoners on death row throughout the USA. His death publicly marked the resumption of capital punishment within certain states. A previous ruling in 1973 banned the practice altogether, declaring the act to be unconstitutional. Gilmores case sparked lots of media attention, dividing public opinion.

c)(c

Twenty-four states currently allow the death penalty. Twenty-three states have abolished capital punishment altogether. Three states, California, Oregon, and Pennsylvania, have governor-issued moratoriums in place, halting executions in the state. Michigan became the first state to abolish, in 1846. Virginia is the most recent state to abolish the practice on July 1, 2021. Crimes eligible to receive capital punishment include murder, espionage, war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and treason. Since, 1972, all executions performed have been for acts of homicide. Gilmore was found guilty of killing two young men during an armed robbery. The men were Max Jensen and Bennie Bushnell.

c)(c

Gilmore gained notoriety due to his insistence on being executed and his refusal to appeal his sentence. He thought he had a good case for 'insanity', given the lack of control he experienced leading up to these crimes. Gilmore's lawyers fought to have his death sentence overturned, arguing that he was mentally ill and therefore not fit for execution. This led to Gilmore firing both of them. Four separate psychiatrists examined Gilmore and stated in court that, while he did have an antisocial personality disorder, which may have been aggravated by drinking and the prescription drug Fiorinal, he did not meet the legal criteria for insanity.

c)(c

Gilmores brother claims that Gary had undergone earlier medical examinations during his previous 15 year incarceration. According to him, the results indicated that Gilmore suffered from psychopathic personality disorders and was deeply scarred from childhood abuse. He was highly intelligent and continually educated himself in prison. He was naturally creative and a gifted artist.

c)(c

Unfortunately, prison increased his tendency to resist authority and find conflict in social situations. He gained a reputation for violence, frequently attacking other inmates and guards. He was constantly subdued with prolixin, an antipsychotic drug. The days leading up to the murders, friends noted Gilmores' irrational and threatening behaviour. He was angry and somewhat disconnected.

c)(c

The courts ultimately upheld his sentence and the death penalty was administered. Upon hearing his guilty verdict, Gilmore told the judge: "it's been sanctioned by the courts and I accept that" He publicly denounced activists and religious spokespeople who protesting the death penalty. "It's my life, and my death" he told journalists. He rejected his own mothers efforts to appeal and get a stay. He quoting Nietzsche, saying " the time comes when a man should rise to meet the occasion"

c)(c

His attitude towards his impending execution was unusual, as most death row inmates fight their sentences through appeals and other legal means. Before his execution, Gilmore gave numerous interviews to the media, expressing regret for his crimes but insisting that he deserved to die for them. On the day of his execution activists protested outside the prison, opposing the death sentence. His story became the basis for Norman Mailer's book "The Executioner's Song" which won a Pulitzer Prize and was later made into a movie starring Tommy Lee Jones.

c)(c

The execution itself was also controversial. Gilmore had chosen to be executed by firing squad, which was still legal in Utah at the time, but not common.

The night before Gilmour's sentence was fulfilled, the death row prisoner was granted permission for family to visit his cell. His uncle smuggled a bottle of booze into jail. Gary enjoyed a robust last supper in jolly drunkenness. Johnny Cash even called Gary to sing a song for him over the phone.

17/01/1977 At approximately 8:00 am Gary Mark Gilmore is escorted to a large padded room, historically named The Slaughterhouse. A small group of family, media & friends attend the event but won't witness the killing. The act is so brutal and performed by a voluntary firing squad. Strapped to a leather chair with a target across his heart, Gilmore sits motionless, showing no resistance. Despite earlier requests to keep his face exposed, Gilmores head is covered with a black corduroy slip. His last spoken words were reportedly "Let's do it". The killers death-wish was adapted by Nike, who changed it to "Just Do It" in the early 80's. The slogan became a positive affirmation encouraging confidence, spontaneity and personal empowerment. Gilmore was definitely fearless, hailed by some as an antihero, a martyr among outlaws 'sticking' it to the man.' Despite the city's Mormon influence, Gilmore was born a catholic. A priest was present to reads his last rites before the final countdown begins. From behind a curtain five shots are fired from 30-30 deer rifles. Four of them are loaded with steel-jacketed shells and the first one contains a blank. All effort is made to ensure the executioners conscience and identity are protected. The gunmen remain anonymous, permanently unaware of which gun fired a blank and which shot the fatal bullets.

c)(c

Gilmores body jerks upon impact as Thirty Six years of life bleed from a hole in his heart. Four bullet holes have passed through the man's body to become permanently lodged in the leather behind him. Two minutes pass before Gilmore is pronounced 'officially dead.' The heart must be silent and the blood flow must cease before doctors are permitted to undertake the organ removal procedure. The surgery is prompt, unsightly and undeniably final. There's no chance of return for an organ donor.

c)(c

In 1977 punk band The Adverts reference this in their song 'Gary Gilmores Eyes'. Imagined from the perspective of an organ recipient awaking to discover whose eyes they've just inherited.

"The doctors are avoiding me. My vision is confused. I listen to my earphones, I catch the evening news. A murderer's been killed and he donates his sight to science. I'm locked into a private ward. I realize that I must be...Looking through Gary Gilmore's eyes."

C)(C

#true crime#serial killers#criminal investigations#crime after crime#documentary#death penalty#gary gilmore#1970's#american crime story

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Songs About Murderers

)c(

#true crime#serial killers#criminal investigations#crime after crime#psycho killer#murder ballads#songs about serial killers#john wayne gacy#true story#Charles Starkweather#Rose West#albert desalvo#boston strangler#spree killer#Neko case#bruce springsteen#interpol#Rolling stones#sufjan stevens#brenda spencer#the boomtown rats#Spotify

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Killer Queen

)c(

In the mid 1980's Paulin & Mathurin went on a savage killing spree that would send shockwaves through Paris..

The couple met in a gay bar, where Paulin performed drag and worked as a waiter. They both dreamed of fame and were drawn to the bright lights, but Champagne, cocaine and all night parties required a lot of money. The lovers began pickpocketing in order to fund their lavish drug-fuelled lifestyle although Petty theft soon escalated to home invasions and then murder. The motive was always money. They tortured victims to get what they wanted then killed them to avoid getting caught.

What made these two so nasty was their choice of victim, vulnerable old ladies. Most of them were in their 80's but one poor girl was in her 90's. All the granny's were strangled. No sexual crimes were committed against the victims but Paulin stabbed some, beat others and forced one to drink caustic soda.

After killing 21 grandmas Thierry Paulin was finally caught and blamed his now ex-partner Jean-Thierry Mathurin's name for everything.

Shortly after his arrest in 1989, Thierry died of an HIV related illness, leaving Mathurin to face the consequences of the trial.

#true crime#serial killers#criminal investigations#crime after crime#documentary#Thierry Paulin#Jean Thierry Mathurin#France#granny killer#gay#drag queen#killer queen#montmartre#Paris#spree killer

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Avery Family Murders

)c(

Jeffrey Lundgren and RLDS

#Kirkland Temple#Avery Family Murders#Jeffrey Lundgren#mormon#Cult#cults#true crime#serial killers#criminal investigations#crime after crime#documentary#RLDS

1 note

·

View note

Text

Serial Killers listed by highest I.Q

1. Ted Kaczynski IQ:167

2. Charlene Gallego IQ:160

3. Rodney Alcala IQ:160

4. Carroll Edward Cole IQ:152

5. Edmund Kemper IQ:145

6. Robert Browne IQ: 140

7. Charles Albright IQ:140

8. Michael Bear Carson IQ:138

9. Lawrence Bittaker IQ:138

10. Ted Bundy IQ:136

11. Thomas Dillon IQ:134

12. Gerard John Schaefer IQ:130

13. Marcel Petiot IQ:130

14. Harvey Glatman IQ:130

15. Angel Maturino Resendiz IQ:130

16. Juan Vallejo Corona IQ:130

)c(

#true crime#serial killers#criminal investigations#crime after crime#documentary#IQ#Charles Albright#Gerard Schaefer#marcel Petiot#Ed Kemper#emotional intelligence

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

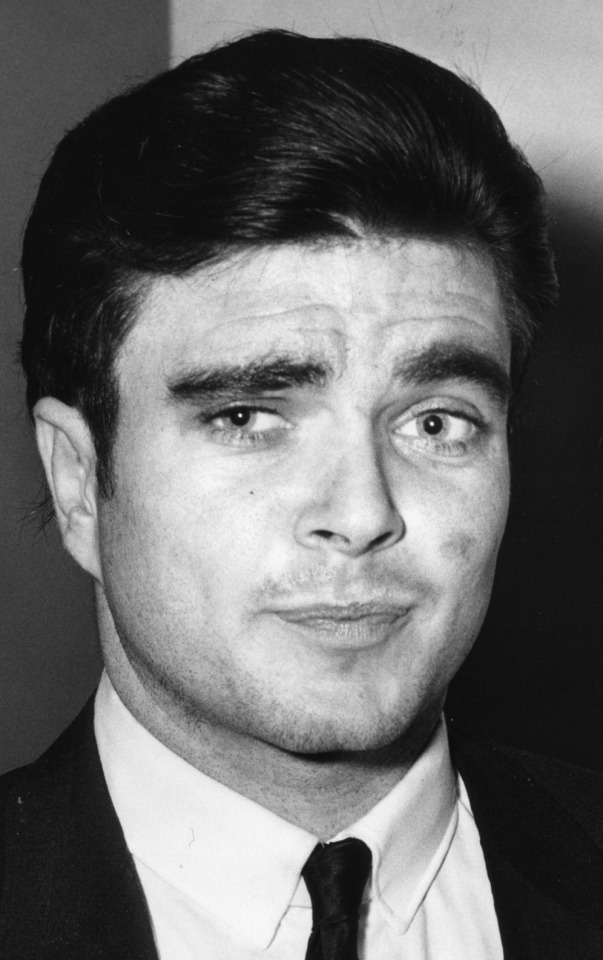

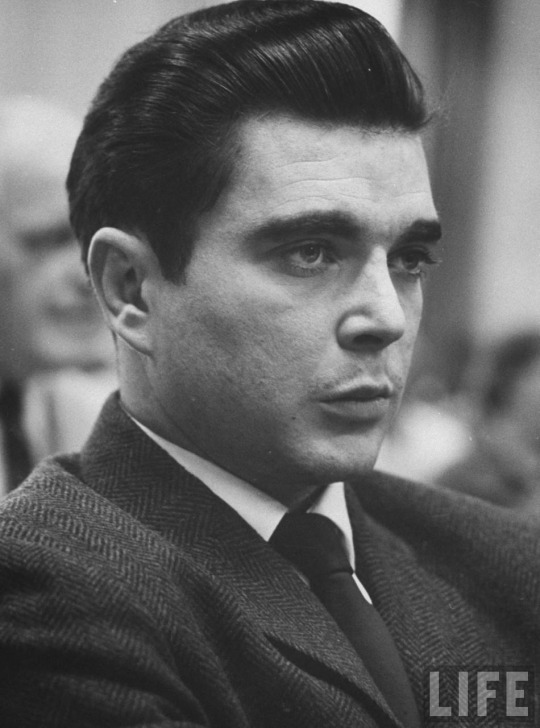

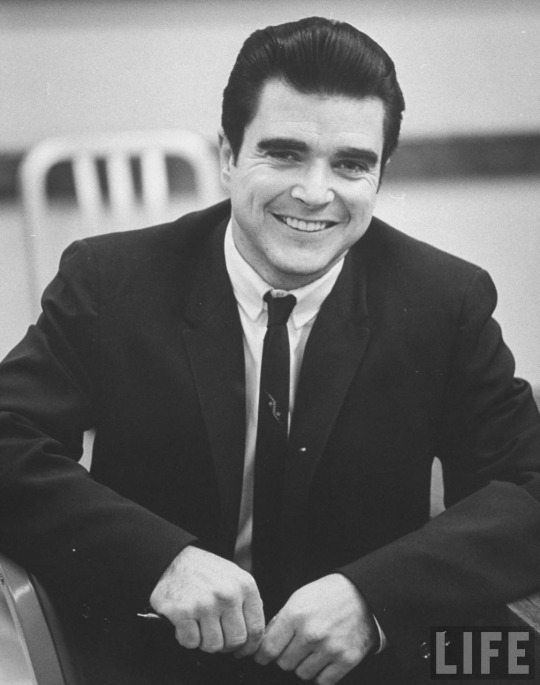

Charles Schmid: The Pied Piper Of Tucson

)c(

Originally published in LIFE magazine, March 4th, 1966. Written by Don Moser

At dusk in Tucson, as the stark, yellowflared mountains begin to blur against the sky, the golden car slowly cruises Speedway. Smoothly it rolls down the long divided avenue, past the supermarkets, the gas stations and the motels; past the twist joints, the sprawling drivein restaurants. The car slows for an intersection, stops, then pulls away again. The exhaust mutters against the pavement as the young man driving takes the machine swiftly, expertly through the gears. A car pulls even with him; the teenage girls in the front seat laugh, wave and call his mane. The young man glances toward the rearview mirror, turned always so he can look at his own reflection, and he appraises himself.

The face is his own creation; the hair dyed raven black, the skin darkened to a deep tan with pancake makeup, the lips whitened, the whole effect heightened by a mole he has painted on one cheek. But the deepset blue eyes are all his own. Beautiful eyes, the girls say.

Approaching the HiHo, the teenagers’ nightclub, he backs off on the accelerator, then slowly cruises on past Johnie’s Drivein. The cars are beginning to orbit and accumulate in the parking lot—near sharp cars with deepthroated mufflers and Maltesecross decals on the windows. But it’s early yet. Not much going on. The driver shifts up again through the gears, and the golden car slides away along the glitter and gimcrack of Speedway. Smitty keeps looking for the action.

Whether the juries in the two trials decide that Charles Howard Schmid Jr. did or did not brutally murder Alleen Rowe, Gretchen Fritz and Wendy Fritz has from the beginning seemed of almost secondary importance to the people of Tucson. They are not indifferent. But what disturbs them far beyond the question of Smitty’s guilt or innocence are the revelations about Tucson itself that have followed on the disclosure of the crimes. Starting from the bizarre circumstances of the killings and on through the ugly fragments of the plot—which in turn hint at other murders as yet undiscovered, at teenage sex, blackmail, even connections with the Cosa Nostra—they have had to view their city in a new and unpleasant light. The fact is that Charles Schmid—who cannot be dismissed as a freak, an aberrant of no consequence—had for years functioned successfully as a member, even a leader, of the yeastiest stratum of Tucson’s Popular teenage society.

As a high school student Smitty had been, as classmates remember, an outsider—but not that far outside. He was small but he was a fine athlete, and in his last year—1960—he was a state gymnastics champion. His grades were poor, but he was in no trouble to speak of until his senior year, when he was suspended for stealing tools from a welding class.

But Smitty never really left the school. After his suspension he hung around waiting to pick up kids in a succession of sharp cars which he drove fast and well. He haunted all the teenage hangouts along Speedway, including the bowling alleys and the public swimming pool—and he put on spectacular driving exhibitions for girls far younger than he.

At the time of his arrest last November, Charles Schmid was 23 years old. He wore face makeup and dyed his hair. He habitually stuffed three or four inches of old rags and tin cans into the bottoms of his hightopped boots to make himself taller than his fivefootthree and stumble about so awkwardly while walking that some people thought he had wooden feet. He pursed his lips and let his eyelids droop in order to emulate his idol, Elvis Presley. He bragged to girls that he knew 100 ways to make love, and that he ran dope, that he was a Hell’s Angel. He talked about being a rough customer in a fight (he was, though he was rarely in one), and he always carried in his pocket tint bottles of salt and pepper, which he said he used to blind his opponents. He liked to use highfalutin language and had a favorite saying, “I can manifest my neurotical emotions, emancipate an epicureal instinct, and elaborate on my heterosexual tendencies.”

He occasionally shocked even those who thought they knew him well. A friend says that he once saw Smitty tie a string to the tail of his pet cat, swing it around his head and beat it bloody against a wall. Then he turned calmly and asked, “You feel compassion—why?”

Yet even while Smitty tried to create an exalted, heroic image of himself, he had worked on a pitiable one. “He thrived on feeling sorry for himself,” recalls a friend, “and making others feel sorry for him.” At various times Smitty told inmates that he had leukemia and didn’t have long to live. He claimed that he was adopted, that his real name was Angel Rodriguez, that his father was a “bean” (local slang for Mexican, an inferior race in Smitty’s view), and that his mother was a famous lawyer who would have nothing to do with him.

What made Smitty a hero to Tucson’s youth?

Isn’t Tucson—out there in the Golden West, in the grand setting where the skies are not cloudy all day—supposed to be a flowering of the American Dream? One envisions teenagers who drink milk, wear crewcuts, go to bed at half past 9, say “Sir” and “Ma’am,” and like to go fishing with Dad. Part of Tucson is like this—but the city is not yet Utopia. It is glass and chrome and wellweathered stucco; it is also gimcrack, ersatz, and urban sprawl at its worst. Its suburbs stretch for mile after mile—a level sea of bungalows, broken only by mammoth shopping centers, that ultimately peters out among the cholla and saguaro. The city has grown from 85,000 to 300,000 since World War II. Few who live there were born there, and a lot are just passing through. Its superb climate attracts the old and the infirm, many of whom, as one citizen put it, “have come here to retire from their responsibilities to life.” Jobs are hard to find and there is little industry to stabilize employment. (“What do people do in Tucson?” the visitor asks. Answer: “They do each other’s laundry.”)

As for the youngsters, they must compete with the army of semiretired who are willing to take on parttime work for the minimum wage. Schools are beautiful but overcrowded; and at those with split sessions, the kids are on the loose from noon on, or from 6 p.m. till noon the next day. When they get into trouble, Tucson teenagers are capable of getting into trouble in style: a couple of years ago they shocked the city fathers by throwing a series of beerdrinking parties in the desert, attended by scores of kids. The fests were called “boondockers” and if they were no more sinful than any other kid’s drinking parties, they were at least on a magnificent scale. One statistic seems relevant: 50 runaways are reported to the Tucson police department each month.

Of an evening kids have nothing to do wind up on Speedway, looking for action. There is the teenage nightclub (“Pickup Palace,” the kids call it). There are the rock’n’roll beer joints (the owners check ages meticulously, but young girls can enter if they don’t drink; besides, anyone can buy a phony I.D. card for $2.50 around the high schools) where they can Jerk, Swim, and Frug away the evening to the roomshaking electronic blare of Hang on Sloopy, The Pied Piper and a number called The Bo Diddley Rock. At the drivein hamburger and pizza stands their cars circle endlessly, mufflers rumbling, as they check each other over.

Here on Speedway you find Ritchie and Ronny, out of work and bored and with nothing to do. Here you find Debby and Jabron, from the wrong side of the tracks, aimlessly cruising in their battered old car looking for something—anything – to relieve the tedium of their lives, looking for somebody neat. (“Well if the boys look bitchin’ you pull up next to them in your car and you roll down the window and say ‘Hey, how about a dollar for gas?” and if they give you the dollar then maybe you let them take you to Johnie’s for a coke.”) Here you find Gretchen, pretty and rich and with problems, bad problems. Of a Saturday night, all of them cruising the long, bright street that seems endlessly in motion with the young. Smitty’s people.

He had a nice car. He had plenty of money from his parents, who ran a nursing home, and he was always glad to spend it on anyone who’d listen to him. He had a pad of his own where he threw parties and he had impeccable manners. He was always willing to help a friend and he would send flowers to girls who were ill. He was older and more mature than most of his friends. He knew where the action was, and if he wore makeup—well, at least he was different.

Some of the older kids—those who worked, who had something else to do—thought Smitty

was a creep. But to the youngsters—to the bored and the lonely, to the dropout and the delinquent, to the young girls with beehive hairdos and tight pants they didn’t quite fill out, and to the boys with acne and no jobs—to these people, Smitty was a kind of folk hero. Nutty maybe, but at least more dramatic, more theatrical, more interesting than anyone else in their lives: a semiludicrous, sexyeyed pied piper who, stumbling along in his ragstuffed boots, led them up and down Speedway.

On the evening of May 31, 1964, Alleen Rowe prepared to go to bad early. She had to be in class by 6 a.m., and she had an examination the next day. Alleen was a pretty girl of 15, a betterthanaverage student who talked about going to college and becoming an oceanographer. She was also a sensitive child—given to reading romantic novels and taking long walks in the desert at night. Recently she had been going through a period of adolescent melancholia, often talking with her mother, a nurse, about death. She would, she hoped, be some day reincarnated as a cat.

On this evening, dressed in a black bathing suit and thongs, her usual costume around the house, she had watched the Beatles on TV and had tried to teach her mother to dance the Frug. Then she took her bath, washed her hair and came out to kiss her mother good night. Norma Rowe, an attractive, womanly divorcee, was somehow moved by the girl’s clean fragrance and said, “You smell so good—are you wearing perfume?”

“No, Mom,” the girl answered, laughing, “it’s just me.”

A little later Mrs. Rowe looked in on her daughter, found her apparently sleeping peacefully, and then left for her job as a night nurse in a Tucson hospital. She had no premonition of danger, but she had lately been concerned about Alleen’s friendship with a neighbor girl named Mary French.

Mary and Alleen had been spending a good deal of time together, smoking and giggling and talking girl talk in the Rowe backyard. Norma Rowe did not approve. She particularly did not approve of Mary French’s friends, a tall, gangling boy of 19 named John Saunders and another named Charles Schmid. She had seen Smitty racing up and down the street in his car and once, when he came to call on Alleen and found her not at home, he had looked at Norma so menacingly with his “pinpoint eyes” that she had been frightened.

Her daughter, on the other hand, seemed to have mixed feelings about Smitty. “He’s creepy,” she once told her mother, “he just makes me crawl. But he can be nice when he wants to.”

At any rate, later that night—according to Mary French’s sworn testimony—three friends arrived at Alleen Rowe’s house: Smitty, Mary French and Saunders. Smitty had frequently talked with Mary French about killing the Rowe girl by hitting her over the head with a rock. Mary French tapped on Alleen’s window and asked her to come out and drink beer with them. Wearing a shift over her bathing suit, she came willingly enough.

Schmid’s accomplices were strange and pitiable creatures. Each of them was afraid of Smitty, yet each was drawn to him. As a baby, John Saunders had been so afflicted with allergies that scabs encrusted his entire body. To keep him from scratching himself his parents had tied his hands and feet to the crib each night, and when eventually he was cured he was so conditioned that he could not go to sleep without being bound hand and foot.

Later, a scrawny boy with poor eyesight (“Just a skinny little body with a big head on it”), he was taunted and bullied by larger children; in turn he bullied those who were smaller. He also suffered badly from asthma and he had few friends. In high school he was a poor student and constantly in minor trouble.

Mary French, 19, was—to put it straight—a frump. Her face, which might have been pretty, seemed somehow lumpy, her body shapeless. She was not dull but she was always a poor student, and she finally had simply stopped going to high school. She was, a friend remembers, “fantastically in love with Smitty. She just sat home and waited while he went out with other girls.”

Now, with Smitty at the wheel, the four teenagers headed for the desert, which begins out Golf Links Road. It is spooky country, dry and empty, the yellow sand clotted with cholla and mesquite and stunted, strangely green palo verde trees, and the great humanoid saguaro that hulk against the sky. Out there at night you can hear the yip and kiyi of coyotes, the piercing screams of wild creatures—cats, perhaps.

According to Mary French, they got out of the car and walked down into a wash, where they sat on the sand and talked for a while, the four of them. Schmid and Mary then started back to the car. Before they got there, they heard a cry and Schmid turned back toward the wash.

Mary went on to the car and sat in it alone. After 45 minutes, Saunders appeared and said Smitty wanted her to come back down. She refused, and Saunders went away. Five or 10 minutes later, Smitty showed up. “He got into the car,” says Mary, “and he said ‘We killed her. I love you very much.’ He kissed me. He was breathing real hard and seemed excited.” Then Schmid got a shovel from the trunk of the car and they returned to the wash. “She was lying on her back and there was blood on her face and head,” Mary French testified. Then the three of them dug a shallow grave and put the body in it and covered it up. Afterwards, they wiped Schmid’s car clean of Alleen’s fingerprints.

More than a year passed. Norma Rowe had reported her daughter missing and the police searched for her—after a fashion. At Mrs. Rowe’s insistence they picked up Schmid, but they had no reason to hold him. The police, in fact, assumed that Alleen was just one more of Tucson’s runaways.

Norma Rowe, however, had become convinced that Alleen had been killed by Schmid, although she left her kitchen light on every night just in case Alleen did come home. She badgered the police and she badgered the sheriff until the authorities began to dismiss her as a crank. She began to imagine a highlevel conspiracy against her. She wrote the state attorney general, the FBI, the U.S. Department of health, Education and Welfare. She even contacted a New Jersey mystic, who said she could see Alleen’s body out in the desert under a big tree.

Ultimately Norma Rowe started her own investigation, questioning Alleen’s friends, poking around, dictating her findings to a tape recorder; she even tailed Smitty at night, following him in her car, scared stiff that he might spot her.

Schmid, during this time, acquired a little house of his own. There he held frequent parties, where people sat around amid his stacks of Playboy magazines, playing Elvis Presley records and drinking beer.

He read Jules Feiffer’s novel, Harry, the Rat with Women, and said that his ambition was to be like Harry and have a girl commit suicide over him. Once, according to a friend, he went to see a minister, who gave him a Bible and told him to read the first three chapters of John. Instead Schmid tore the pages out and burned them in the street. “Religion is a farce,” he announced. He started an upholstery business with some friends, called himself “founder and president,” but then failed to put up the money he’d promised and the venture was shortlived.

He decided he liked blondes best, and took to dyeing the hair of various teenage girls he went around with. He went out and bought two imitation diamond rings for about $13 apiece and then engaged himself, on the same day, both to Mary French and to a 15yearold girl named Kathy Morath. His plan, he confided to a friend, was to put each of the girls to work and have them deposit their salaries in a bank account held jointly with him. Mary French did indeed go to work in the convalescent home Smitty’s parents operated. When their bank account was fat enough, Smitty withdrew the money and bought a tape recorder.

By this time Smitty also had a girl from a higher social stratum than he usually was involved with. She was Gretchen Fritz, daughter of a prominent Tucson heart surgeon. Gretchen was a pretty, thin, nervous girl of 17 with a knack for trouble. A teacher described her as “erratic, subversive, a psychopathic liar.”

At the horsy private school she attended for a time she was a misfit. She not only didn’t care about horses, but she shocked her classmates by telling them they were foolish for going out with boys without getting paid for it. Once she even committed the unpardonable social sin of turning up at a formal dance accompanied by boys wearing what was described as beatnik dress. She cut classes, she was suspected of stealing and when, in the summer before her senior year, she got into trouble with juvenile authorities for her role in an attempted theft at a liquor store, the headmaster suggested she not return and then recommended she get psychiatric treatment.

Charles Schmid saw Gretchen for the first time at a public swimming pool in the summer of 1964. He met her by the simple expedient of following her home, knocking on the door and, when she answered, saying, “Don’t I know you?” They talked for an hour. Thus began a fierce and stormy relationship. A good deal of what authorities know of the development of this relationship comes from the statements of a spindly scarecrow of a young man who wears pipestem trousers and Beatle boot: Richard Bruns. At the time Smitty was becoming involved with Gretchen, Bruns was 18 years old. He had served two terms in the reformatory at Fort Grant. He had been in and out of trouble his whole life, had never fit in anywhere. Yet, although he never went beyond the tenth grade in school and his credibility on many counts is suspect, he is clearly intelligent and even sensitive. He was, for a time, Smitty’s closest friend and confidant, and he is today one of the mainstays of the state’s case against Smitty. His story:

“He and Gretchen were always fighting,” says Bruns. “She didn’t want him to drink or go out with the guys or go out with other girls. She wanted him to stay home, call her on the phone, be punctual. First she would get suspicious of him, then he’d get suspicious of her. They were made for each other.”

Their mutual jealousy led to sharp and continual arguments. Once she infuriated him by throwing a bottle of shoe polish on his car. Another time she was driving past Smitty’s house and saw him there with some other girls. She jumped out of her car and began screaming. Smitty took off into the house, out the back and climbed a tree in his backyard.

His feelings for her were an odd mixture of hate and adoration. He said he was madly in love with her, but he called her a whore. She would let Smitty in her bedroom window at night. Yet he wrote an anonymous letter to the Tucson Health Department accusing her of having venereal disease and spreading it about town. But Smitty also went to enormous lengths to impress Gretchen, once shooting holes through the windows of his car and telling her that thugs, from whom he was protecting her, had fired at him. So Bruns described the relationship.

On the evening of Aug. 16, 1965, Gretchen Fritz left the house with her little sister Wendy, a friendly, lively 13yearold, to go to a drivein movie. Neither girl ever came home again. Gretchen’s father, like Alleen Rowe’s mother, felt sure that Charles Schmid had something to do with his daughters’ disappearance, and eventually he hired Bill Heilig, a private detective, to handle the case. One of Heilig’s men soon found Gretchen’s red compact car parked behind a motel, but the police continued to assume that the girls had joined the ranks of Tucson’s runaways.

About a week after Gretchen disappeared, Bruns was at Smitty’s house. “We were sitting in the living room,” Bruns recalls. “He was sitting on the sofa and I was in the chair by the window and we got on the subject of Gretchen. He said, ‘You know I killed her?’ I said I didn’t, and he said ‘You know where?’ I said no. He said, ‘I did it here in the living room. First I killed Gretchen, then Wendy was still going “huh, huh, huh,” so I ... [Here Bruns showed how Smitty made a garroting gesture.] Then I took the bodies and I put them in the trunk of the car. I put the bodies in the most obvious place I could think of because I just didn’t care anymore. Then I ditched the car and wiped it clean.’”

Bruns was not particularly upset by Smitty’s story. Months before, Smitty had told him of the murder of Alleen Rowe, and nothing had come of that. So he was not certain Smitty was telling the truth about the Fritz girls. Besides, Bruns detested Gretchen himself. But what happened next, still according to Bruns’s story, did shake him up.

One night not long after, a couple of toughlooking characters, wearing sharp suits and smoking cigars, came by with Smitty and picked up Bruns. Smitty said they were Mafia, and that someone had hired them to look for Gretchen. Smitty and Bruns were taken to an apartment where several men were present whom Smitty later claimed to have recognized as local Cosa Nostra figures.

They wanted to know what had happened to the girls. They made no threats, but the message, Bruns remembers, came across loud and clear. These were no streetcorner punks: these were the real boys. In spite of the intimidating company, Schmid lost none of his insouciance. He said he didn’t know where Gretchen was, but if she turned up hurt he wanted these men to help him get whoever was responsible. He added that she might have gone to California.

By the time Smitty and Bruns got back to Smitty’s house, they were both a little shaky. Later that night, says Bruns, Smitty did the most unlikely thing imaginable: he called the FBI. First he tried the Tucson office and couldn’t raise anyone. Then he called Phoenix and couldn’t get an agent there either. Finally he put in a persontoperson call to J. Edgar Hoover in Washington. He didn’t get Hoover, of course, but he got someone and told him that the Mafia was harassing him over the disappearance of a girl. The FBI promised to have someone in touch with him soon.

Bruns was scared and said so. It occurred to him now that if Smitty really had killed the Fritz girls and left their bodies in an obvious place, they were in very bad trouble indeed—with the Mafia on one hand and the FBI on the other. “Let’s go bury them,” Bruns said.

“Smitty stole the keys to his old man’s station wagon,” says Bruns, “and then we got a flat shovel—the only one we could find. We went to Johnie’s and got a hamburger, and then we drove out to the old drinking spot [in the desert]—that’s what Smitty meant when he said the most obvious place. It’s where we used to drink beer and make out with girls.

“So we parked the car and got the shovel and walked down there, and we couldn’t find anything. Then Smitty said, ‘Wait, I smell something.’ We went in opposite directions looking, and then I heard Smitty say, ‘Come here.’ I found him kneeling over Gretchen. There was a white rag tied around her legs. Her blouse was pulled up and she was wearing a white bra and Capris.

“Then he said, ‘Wendy’s up this way.’ I sat there for a minute. Then I followed Smitty to where Wendy was. He’d had the decency to cover her—except for one leg, which was sticking up out of the ground.

“We tried to dig with the flat shovel. We each took turns. He’d dig for a while and then I’d dig for a while, but the ground was hard and we couldn’t get anywhere with that flat shovel. We dug for twenty minutes and finally Smitty said we’d better do something because it’s going to get light. So he grabbed the rag that was around Gretchen’s legs and dragged her down in the wash. It made a noise like dragging a hollow shell. It stunk like hell. Then Smitty said wipe off her shoes, there might be fingerprints, so I wiped them off with my handkerchief and threw it away.

“We went back to Wendy. Her leg was sticking up with a shoe on it. He said take off her tennis shoe and throw it over there. I did, I threw it. Then he said, ‘Now you’re in this as deep as I am.’” By then, the sisters had been missing for about two weeks.

Early next morning Smitty did see the FBI. Nevertheless—here Bruns’s story grows even wilder—that same day Smitty left for California, accompanied by a couple of Mafia types, to look for Gretchen Fritz. While there, he was picked up by the San Diego police on a complaint the he was impersonating an FBI officer. He was detained briefly, released and returned to Tucson.

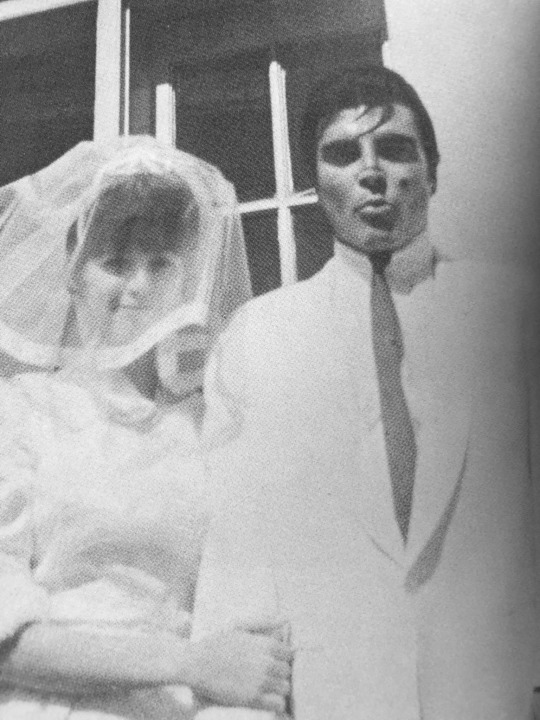

But now, it seemed to Richard Bruns, Smitty began acting very strangely. He startled Bruns by saying, “I’ve killed—not three times, but four. Now it’s your turn, Ritchie.” He went berserk in his little house, smashing his fist through a wall, slamming doors, then rushing out into the backyard in nothing but his undershorts, where he ran through the night screaming, “God is going to punish me!” He also decided, suddenly, to get married—to a 15yearold girl who was a stranger to most of his friends.

If Smitty seemed to Bruns to be losing his grip, Ritchie Bruns himself was not in much better shape. His particular quirk revolved around Kathy Morath, the thin, pretty, 16yearold daughter of a Tucson postman. Kathy had once been attracted to Smitty. He had given her one of his two cutglass engagement rings. But Smitty never really took her seriously, and one day, in a fit of pique and jealousy, she threw the ring back in his face. Ritchie Bruns comforted her and then started dating her himself. He was soon utterly and irrevocably smitten with goofy adoration.

Kathy accepted Bruns as a suitor, but halfheartedly. She thought him weird (oddly enough, she did not think Smitty in the least weird) and their romance was shortlived. After she broke up with him last July, Bruns went into a blue funk, a nosedive into romantic melancholy, and then, like some loveswacked Elizabethan poet, he started pouring out his heart to her on paper. He sent her poems, short stories, letters 24 pages long. (“My God, you should have read the stuff,” says her perplexed father. “His letters were so romantic it was like ‘Next week, East Lynne.’” Bruns even began writing a novel dedicated to “My Darling Kathy.”

If Bruns had confined himself to literary catharsis, the murders of the Rowe and Fritz girls might never have been disclosed. But Ritchie went a little bit around the bend. He became obsessed with the notion that Kathy Morath was the next victim on Smitty’s list. Someone had cut the Moraths’ screen door, there had been a prowler around her house, and Bruns was sure that it was Smitty. (Kathy and her father, meantime, were sure it was Bruns.)

“I started having this dream,” Bruns says. “It was the same dream every night. Smitty would have Kathy out in the desert and he’d be doing all those things to her, and strangling her, and I’d be running across the desert with a gun in my hand, but I could never get there.”

If Bruns couldn’t save Kathy in his dreams, he could, he figured, stop a walking, breathing Smitty. His scheme for doing so was so wild and so simple that it put the whole Morath family into a state of panic and very nearly landed Bruns in jail.

Bruns undertook to stand guard over Kathy Morath. He kept watch in front of her house, in the alley, and in the street. He patrolled the sidewalk from early in the morning till late at night, seven days a week. If Kathy was home he would be there. If she went out, he would follow her.

Kathy’s father called the police, and when they told Bruns he couldn’t loiter around like that, Bruns fetched his dog and walked the animal up and down the block, hour after hour.

Bruns by now was wallowing in feelings of sacrifice and nobility—all of it unappreciated by Kathy Morath and her parents. At the end of October, he was finally arrested for harassing the Morath family. The judge, facing the obviously woebegone and smitten young man, told Bruns that he wouldn’t be jailed if he’d agree to get out of town until he got over his infatuation.

Bruns agreed and a few days later went to Ohio to stay with his grandmother and try to get a job. It was hopeless. He couldn’t sleep at night, and if he did doze off he had his old nightmare again.

One night he blurted out the whole story to his grandmother in their kitchen. She thought he had had too many beers and didn’t believe him. “I hear beer does strange things to a person,” she said comfortingly. At her words Bruns exploded, knocked over a chair and shouted, “The one time in my life when I need advice and what do I get?” A few minutes later he was on the phone to the Tucson police.

Things happened swiftly. At Bruns’s frantic insistence, the police picked up Kathy Morath and put her in protective custody. They went into the desert and discovered—precisely as Bruns had described them—the grisly, skeletal remains of Gretchen and Wendy Fritz. They started the machinery that resulted in the arrest a week later of John Saunders and Mary French. They found Charles Schmid working in the yard of his little house, his face layered with makeup, his nose covered by a patch of adhesive plaster which he had worn for five months, boasting that his nose was broken in a fight, and his boots packed full of old rags and tin cans. He put up no resistance.

John Saunders and Mary French confessed immediately to their roles in the slaying of Alleen Rowe and were quickly sentenced, Mary French to four to five years, Saunders to life. When Smitty goes on trial for this crime, on March 15, they will be principal witnesses against him.

Meanwhile Ritchie Bruns, the perpetual misfit, waits apprehensively for the end of the Fritz trial, desperately afraid that Schmid will go free. “If he does,” Bruns says glumly, “I’ll be the first one he’ll kill.”

As for Charles Schmid, he has adjusted well to his period of waiting. He is polite and agreeable with all, though at the preliminary hearings he glared menacingly at Ritchie Bruns. Dressed tastefully, tie neatly knotted, hair carefully combed, his face scrubbed clean of makeup, he is a short, compact, darkly handsome young man with a wide, engaging smile and those deepset eyes.

The people of Tucson wait uneasily for what fresh scandal the two trials may develop. Civic leaders publicly cry that a slur has been cast on their community by an isolated crime. High school students have held rallies and written vehement editorials in the school papers, protesting that they all are being judged by the actions of a few oddballs and misfits. But the city reverberates with stories of organized teenage crime and vice, in which Smitty is cast in the role of a minorleague underworld boss. None of these later stories has been substantiated.

One disclosure, however, has most disturbing implications: Smitty’s boasts may have been heard not just by Bruns and his other intimates, but by other teenagers as well. How many—and precisely how much they knew—it remains impossible to say. One authoritative source, however, having listened to the admissions of six high school students, says they unquestionably knew enough so that they should have gone to the police—but were either afraid to talk, or didn’t want to rock the boat. As for Smitty’s friends, the thought of telling the police never entered their minds.

“I didn’t know he killed her,” said one, “and even if I had, I wouldn’t have said anything. I wouldn’t want to be a fink.”

Out in the respectable Tucson suburbs parents have started to crack down on the youngsters

and have declared Speedway hangouts off limits. “I thought my folks were bad before,” laments one grounded 16yearold, “but now they’re just impossible.”

As for the others—Smitty’s people—most don’t care very much. Things are duller without Smitty around, but things have always been dull.

“There’s nothing to do in this town,” says one of his girls, shaking her dyed blond hair. “The only other town I know is Las Vegas and there’s nothing to do there either.” For her, and for her friends, there’s nothing to do in any town.

They are down on Speedway again tonight, cruising, orbiting the driveins, stopping by the joints, where the words of The Bo Diddley Rock cut through the smoke and the electronic dissonance like some macabre reminder of their fallen hero:

All you women stand in line,

And I’ll love you all in an hour’s time.... I got a cobra snake for a necktie,

I got a brandnew house on the roadside Covered with rattlesnake hide,

I got a brandnew chimney made on top, Made out of human skulls.

Come on baby, take a walk with me, And tell me, who do you love? Who do you love? Who do you love? Who do you love?

The Pied Piper of Tucson—Life Magazine March 4, 1966 http://books.google.com/books

#true crime#serial killers#criminal investigations#crime after crime#Charles Schmid#tucson arizona#pied piper#life magazine#Bnw#60’s

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Born To Kill COMPLETE SERIES 2005-2016

“Going back to the age-old Nature vs Nurture debate, a good way to think about it is that genetics provide an individual with a spectrum and the individual’s environment, developmental and otherwise, determines where you lie on it. A predisposition may lie dormant for eternity, but feed it a stressful environment and increased risk factors such as malnourishment and trauma, and it will manifest. Clinical facts must be tempered with ethical concerns when applying science to society.” Source

)c(

Season 1

S01E01 Fred West

S01E02 Harold Shipman

S01E03 Jeffrey Dahmer

S01E04 Myra Hindley

S01E05 The Washington Snipers

S01E06 Ivan Milat

)c(

Season 2

S02E01 Ted Bundy

S02E02 Charles Starkweather

S02E03 John Wayne Gacy

S02E04 Aileen Wuornos

S02E05 Richard Chase

S02E06 Albert DeSalvo

)c(

Season 3

S03E01 Gary Ridgway

S03E02 Edmund Kemper

S03E03 Richard Ramirez

S03E04 Donald Gaskins

S03E05 David Berkowitz

S03E06 Dennis Nilsen

)c(

Season 4

S04E01 Charles Manson

S04E02 Dennis Rader

S04E03 Beverly Allitt

S04E04 Hillside Stranglers (Kenneth Bianchi and Angelo Buono)

S04E05 Colin Ireland

S04E06 Herbert Mullin

)c(

Season 5

S05E01 Peter Sutcliffe

S05E02 Donald Nielson

S05E03 Patrick Mackay

S05E04 John Linley Frazier

S05E05 Cary Stayner

S05E06 The Briley Brothers

S05E07 Hadden Clark

S05E08 Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka

S05E09 Thor Christiansen

S05E10 Dale Hausner and Samuel Dieteman

S05E11 Wesley Shermantine and Loren Herzog

S05E12 Douglas Clark and Carol Bundy

)c(

Season 6

SE06E01 Robert Napper

SE06E02 John Duffy and David Mulcahy

SE06E03 Gerald and Charlene Gallego

SE06E04 Levi Bellfield

SE06E05 Tony Costa

SE06E06 Richard Cottingham

SE06E07 Cleophus Prince Jr.

SE06E08 Sean Gillis

SE06E09 Timothy Wilson Spencer

SE06E10 David Alan Gore and Fred Waterfield

SE06E11 David Carpenter

SE06E12 Bobby Joe Long

)c(

Season 7

SE07E01 Peter Moore

SE07E02 Trevor Hardy

SE07E03 William Suff

SE07E04 Charles Albright

SE07E05 Allan Legere

SE07E06 Robert Reldan

)c(

Born to Kill/Class of Evil 2017

Season 1

SE01E01 Peter Tobin

SE01E02 Altemio Sanchez

SE01E03 Alton Coleman and Debra Brown

SE01E04 Stephen Griffiths

SE01E05 Graham Young

SE01E06 Joanna Dennehy

)c(

Killing Spree 2014

Season 1

SE01E01 Suffolk Strangler

SE01E02 Terror in Paradise

SE01E03 Northumbria Rampage

SE01E04 The Miami Murders

SE01E05 Horror at the Mall

SE01E06 Columbine Massacre

)c(

Season 2

SE01E01 The Hungerford Massacre

SE01E02 Soho Nail Bomber

SE01E03 New York Knifings

SE01E04 Revenge Cop Killer

SE01E05 The Family Slayer

SE01E06 Woman On The Rampage

)c(

Criminal psychologists: Louis B Schlesinger, Helen Morrison, Katherine Ramsland, David Wilson and Robert Ressler.

Narrator: Christoper Slade

TwoFour productions

#true crime#serial killers#crime after crime#criminal investigations#documentary#youtube#wayne henley#spree killers#born to kill#class of evil#jeffery dahmer#Ted Bundy#ed kemper#carol Bundy#peter sutcliffe#Norway Massacre#Bill Suff#Pee Wee Gaskins#The Black Panther#Richard Cottington#myra hindley#Fred West#Charles Starkweather

18 notes

·

View notes