#youthculture

Text

8:00 pm

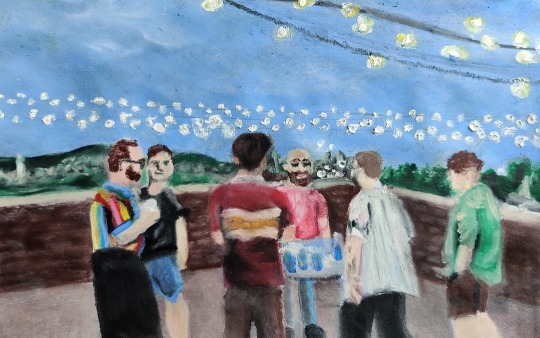

The Paladin Bin EP

#art#rave#illustration#nightlife#oilpastel#sketchbook#underpainting#illustrator#editorial#artmagazine#profiledrawing#portrait#youthculture

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh, yeah, I should really be promoting my videos more.

Like this playlist that sounds like swelling feelings at a carnival.

youtube

#beyonce#beyoncé#pink#p!nk#yeah yeah yeahs#jennah bell#moodboard#mood music#romance#young love#rnb#pop music#folk music#alt rock#art#playlist#pinterest#carnivalcore#youthculture#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

COOL CHANNEL !

#COOL#CHANNEL#PLATESOFMEAT#MAGAZINE#TYOUTH#YOUTH#TSHIRT#CLOTHING#HEHEHEHEHHEEH#HAHAHA#BTOHWORK#BOTH#MAGAZZINE#ZINE#YOUTHCULTURE

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

my generation, part 1

Everything was different when I was a kid.

There was no such thing as a colour television or a personal computer, and the internet hadn’t been invented. If you wanted music, there was the ‘wireless’ or what my grandmother referred to as a gramophone and the rest of us called a record‐player. Discs were vinyl — twenty‐ minute‐a‐side LPs and smaller, three‐minute‐a‐side 45s — and musicians recorded them on two‐ or four‐track reel‐to‐reel tape. The first portable transistor radio was sold in the USA just two months after I was born, but neither eight‐track stereo nor videocassettes were even imagined yet. MTV was launched when I was in my twenties, not long before the first compact disc and the cellular mobile phone. ‘Touch‐tone’ phones with digital keyboards turned up in the USA in the early ’60s. Until then, every phone used slow, rotary dialling. International voice communications were carried only on terrestrial cables, not relayed through satellites, and you still had to ask an operator to connect a call. Facsimile machines — we hadn’t yet learnt to call them faxes — were the size of a coffee table, with a bit‐rate that transmitted a single typewritten page in ten minutes. Even time was analogue. I was a teenager when the first digital watch, the Pulsar, with its bulky, faux‐gold casing and red LED display, went on sale. There were no microwaves, no pocket calculators and no game consoles (arcade games were large and electro‐mechanical, like pinball machines). Credit cards were for the rich — Diner’s Club, Carte Blanche and American Express — and there were no bank cards, no automatic teller machines, and no point‐of‐sale processors. A bank’s customer records were still kept in a file drawer. Your signature was your main form of ID.

It’s a sure sign that you’re growing old when you start to talk about how things used to be. I’m a Baby Boomer, born almost at the mid‐point of a generation whose first members were conceived just before the end of World War II. We came of age in the ’60s, in time for a few of us to be drafted into the first large‐scale deployment of Australian and American soldiers to Vietnam. We were the first generation to be raised in the suburbs, in the identikit, planned estates of low‐rise apartments and brick‐veneer houses that spread like a blight from the edges of Western cities during the economic boom of the ’50s, and the first whose experience of the world was to be shaped not by direct experience, but by mass media. We were also the first to be immersed in a media‐driven culture of consumerism. Ask a Boomer about their earliest childhood memory, and chances are they’ll tell you about a TV show.

Now we’re the first generation to reach old age within this new millennium — the oldest of us turn sixty this year — and, unlike our parents and grandparents, maybe unlike our own children, we’re reluctant to let go of our youth. If anything, we reject ageing altogether, marketing to ourselves the idea that it’s just a state of mind: with the right science and medicine (preferably synthesised within a viable consumer product), a healthy diet, regular exercise and a little hybrid spirituality, we might be able to live forever.

Don’t trust anyone over thirty. This was the unifying sentiment behind the barricades we built between previous generations and us during the ’60s. It didn’t just inspire the raucous anthems of post‐Beatles rock groups like The Who — People try to put us d-down/ Just because we get around/ Things they do look awful c-c-cold/ I hope I die before I get old — it became the underpinning of a societal upheaval that, in many ways, was as subversive in its bid for power and ideological unity as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution conceived by Mao Zedong in China at about the same time. And yet, by the end of the ’60s, before any of the Boomer generation had actually reached thirty, there were few among us who felt a part of it any more. We had learnt not to trust anybody, and there was a tacit resolve to extend the barricades so that we were insulated from not just the generations that preceded us, but the generations that would follow as well. Popular culture had become synonymous with youth — although it only really became known as youth culture with the launch of MTV, the source of a whole new vernacular for mass media and marketing — and we were determined not to let it be pried from our grasp, even when our youth was done.

Baby Boomers didn’t invent youth culture. We weren’t even the first to recognise the economic and social power that youth had begun to acquire, almost inadvertently, in the decade or so after World War II — how could we have been, we were infants, if we were born at all? The sudden demographic up‐welling that spilled across the USA, Western Europe and Australasia to become a surging counter‐current of new attitudes and ideas was unarguably a singularity of the ’60s, but the source of it was actually a generation whose own youth was muted by the uncertainty and hardships of the Great Depression and World War II. Rock’n’roll, the twentieth century’s great, twisted take on an ancient Bardic tradition, was the invention of the Silent Generation. From the hellfire performers who emerged from the God‐fearing rural ghettoes of the former Confederacy states — among them, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, Roy Orbison and Elvis Presley — to unsettle the consciousness and sexual mores of ’50s America’s too‐tightly wrapped middle class, to the younger, working‐ class, urban Englishmen who hero‐worshipped them and went on to form bands — The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Yardbirds, The Animals and, in Australia, The Easybeats — that would eventually overshadow, if not outlast, even Elvis’s unprecedented fame, none was a Baby Boomer.

The ’50s was the first decade in modern history in which youth laid claim to a discrete identity of its own, and instigated a cultural, social, sexual, political and economic revolution that, half a century later, has yet to run its course. Never before had youth gained the upper hand in a developed society — let alone, as it has turned out, held on to it for over half a century. The allure of youth has haunted the middle‐aged of every generation, but you only have to look at movies produced before the ’50s to see that, in the popular imagination, youth used to be what today’s Baby Boomer demographers might describe as ‘aspirationally older’: Bacall chasing Bogart, not the other way around, until James Dean came along. They wanted more than just acceptance by an older generation: they wanted admission to what was presented as its more responsible, rational and coherently structured society — they couldn’t wait to grow up.

Again, the tectonic cultural shifts that disrupted this had nothing to do with Baby Boomers. These began with the frustrated restiveness of the Silent Generation, and the times’ nagging apprehension of an intensifying Cold War between the West and the then Soviet Union, with its sombre, ever‐present nuclear threat of MAD, or mutually assured destruction. There were also fateful connections made, with what was to become a generational inclination to apophenia, between what were, on the surface, a series of apparently disparate events in the decade between 1950 and 1960 — among them, the American witch‐hunts for communist sympathisers between 1950 and 1954, incited by the cynical, ambitious and corrupt Republican senator Joseph McCarthy, the emergence of an Afro‐American civil rights movement, and the defiant Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, inspired by the refusal of a middle‐aged black woman Rosa Parks to give up her seat on a segregated public bus in Alabama, USA, led by a young black minister (another member of the Silent Generation), Martin Luther King, the launch of the first living creature — a dog named Laika — into space in 1957 aboard the Russian Sputnik 4, or the foundation of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in England in 1958 (when the oldest Baby Boomers were just adolescents) by the elderly Bertrand Russell, Victor Gollancz and J.B. Priestley, and the middle‐aged Michael Foot and E.P. Thompson. (This last event prompted the designer and artist Gerald Holton to create the peace symbol — a simple, upside‐down trident based on the semaphore signals for the letters ‘N’ and ‘D’; in a world cluttered by graphics and logos, it endures as one of the 20th centuryʹs most recognisable and best understood icons.

In North America, Western Europe and even Australia, the twenty‐ and thirty-somethings of the Silent Generation were increasingly ready to break with traditional social orders: in their eyes, the so‐called Greatest Generation that went before them had done nothing but drag them through economic chaos and war (albeit in pursuit of the worthy ideal of creating a better world), then marginalise them in the aftermath. Nearly a decade of economic growth spurred by the postwar reconstruction of Europe and the demand it created for North America’s industries — and Australia’s natural resources — had given the Silent Generation economic independence, while prolonged peace and prosperity had encouraged it to invest in leisure, despite the slightly puritanical disapproval of older, more frugal generations. As the 63‐year‐old British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan admonished his fellow Conservatives in a 1957 speech, “Most of our people have never had it so good.”

Maybe we over‐estimate the impact of a twenty‐one‐year‐old Elvis in his first nationally broadcast TV appearance in 1956, but his hyper‐sexual posture and sardonic disdain (mirroring James Dean’s character, Jim Stark, in Nicholas Ray’s now‐ classic film Rebel Without A Cause, released the year before) channelled perfectly the pent‐up desire of the Silent Generation to get up into the face of its elders. Rock’n’roll, James Dean and the reckless swagger of Jack Kerouac’s semi‐fictional Dean Moriarty in the novel On The Road, which was published in 1957 and became an unexpected best‐seller, were the iconic foundations of a very real cultural identity that would gather momentum over the next decade.

It was an identity that Baby Boomers would usurp and, with the unseemly disregard that was to become a generational trait, eventually ‘productize’ and exploit — as they would so many others.

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) –

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

Philip Larkin, from Annus Mirabilis

Even in 1967, when Britain’s repressed poet laureate appropriated the title of a seventeenth century John Dryden poem for his own celebration of a year of miracles – in which the commercial introduction of the oral contraceptive pill in the USA coincided with The Beatles’ first hit records there – it was impossible not to be struck by the irony that, as in the Dryden poem, the year in question was as remarkable for its awfulness as for its chronicle of achievements: 1963 was the year 70,000 British supporters of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament marched from the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment in Aldermarston to London, and American networks shocked their prime‐time TV audiences with footage of a Vietnamese monk setting fire to himself in a Saigon street. It was the year British spy Kim Philby sought asylum in Moscow, and the Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman to voyage into space aboard Vostok 6. It was the year Betty Friedan published the first feminist best‐seller, The Feminine Mystique, revitalising the American women’s movement, and Richard Neville, Martin Sharp and Richard Walsh published the first issue of the Australian satirical magazine Oz. It was the year Martin Luther King, delivered his most famous speech — I have a dream — to more than a quarter of a million people from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC. It was the year one of the most popular US Presidents in history, John F. Kennedy, was gunned down in the back seat of an open‐topped limousine during a motorcade through Dealey Plaza, in downtown Dallas, Texas.

It was a year of lost innocence, in every sense. The last of the Silent Generation turned eighteen, not then old enough to vote or to drink, but old enough to be drafted into the military.

It was probably a Baby Boomer who came up with the hoary old line that if you can remember the ’60s, then you weren’t there. The Silent Generation and the Baby Boomers shared their cheap alcohol, cannabis, psilocybin and LSD, but the context of their experience of those years was different. “There was a pissed‐offness about the ’60s that gets covered over by flower power now, but it was an angry time,” American playwright and actor Sam Shepard recalled in an interview with The Guardian this year. Today, the NRMA resorts to nostalgie de la boue to advertise its insurance policies to aging Baby Boomers — speckled monochrome newsreel footage of us dancing in the mud at some long‐forgotten rock festival — but that decade began not with peace and love but with France testing an atomic bomb in the Sahara, the U.S. deploying 3,500 American troops in Vietnam, the Soviet Union shooting down an American U‐2 spy plane, and the East Germans beginning the construction of the Berlin Wall. For the Silent Generation, whose childhood and adolescence had spanned a prolonged economic depression and a world war, the escalation of the Cold War and the imminent threat of nuclear annihilation tainted their perception of the early ’60s and incited a dark, jittery sense of déjà vu.

As it turned out, 1963 was a pivotal year. It marked the beginning of what would become an acute divergence between the attitudes of the Silent Generation and the Baby Boomers. By then, the Silent Generation had had enough. When their best‐loved poet – a geeky Jewish kid from Hibbing, Minnesota, Robert Zimmerman, who had reinvented himself as Bob Dylan and earned enough agit‐prop credibility to sing for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the occasion for Martin Luther King’s memorable address – scored a commercial and emotional hit with his generational anthem, The Times They are A-Changin’, the times already had.

By the early ’60s, the Silent Generation had the economic clout — not to mention a determination inspired by a childhood in which their parents’ attention had been distracted, if not lost completely, in the pervasive tensions of the war — to change the existing order of society, to make it different if not necessarily better. If any generation could be said to have given the late twentieth century its social conscience, it was the Silent Generation. Over the next twenty years, its influence on public attitudes to issues such as the proliferation of nuclear arms, the war in Vietnam, civil liberties, racial and sexual equality, gay rights and the abuse of political power (specifically, the Nixon presidency and its collapse under the weight of the Watergate scandal) was so constant and deeply felt that we took it for granted.

When, inevitably, the Silent Generation grew tired of the fight, no other generation stepped up to take its place. Quite the opposite. Nowadays, in a post‐9/11 world, Baby Boomers appear to be almost complicit with the erosion of civil rights, the increasing, covert surveillance of public and virtual spaces, the rejection of accountability by elected governments and the oppressive atmosphere of intolerance that are the antitheses of everything the essential spirit of the ’60s – its vibe – was supposed to be about.

Except it never was.

As the hardened ex‐con played by an aged ’60s icon, Terence Stamp, in the 1999 Steven Soderbergh film The Limey recalls: “Did you ever dream about a place you never really recall being to before? A place that maybe only exists in your imagination? Some place far away, half‐remembered when you wake up. When you were there, though, you knew the language. You knew your way around. That was the ’60s. [Pause] No. It wasn’t that either. It was just ’66 and early ’67. That’s all.”

The so‐called Summer Of Love in Haight‐Ashbury, San Francisco in 1967 embodied the hippie ethos of ‘turn on, tune in, and drop out’ — a phrase coined by the psychologist and high‐profile advocate of better living through psycho‐ pharmacology, Timothy Leary — but the idyll was less than the season itself.

In 1966 as a million people gathered along Sydney’s streets to welcome Lyndon Baines Johnson, the first US president to visit the country — they had been exhorted to ‘Make Sydney gay for LBJ’, which, from the perspective of today’s sexually more enlightened age, gave a whole new meaning to Harold Holt’s infamous election slogan, ‘All the way with LBJ’ — 10,000 anti‐war protesters fought a pitched battle with the city’s police, prompting the NSW Premier Rob Askin to order his chauffeur to “drive over the bastards”. Neither peace nor love were to be found anywhere by 1968. When a performance by a rock group, The MC5, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago degenerated into a full‐scale riot, the then mayor of the city, Richard J. Daley authorised “whatever use of force necessary” to quell the situation. Much the same orders had been given (at about the same time) to the commanders of the Warsaw Pact tanks that rolled into Prague in Czechoslovakia, to suppress what Moscow portrayed as an uprising (even it was really just a badly managed attempt at social and economic reform) and, three months earlier, to French riot police, les Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité, when over a million striking students and other protesters took to the streets of Paris.

In 1969, the Woodstock Music and Art Festival, held on a dairy farm in upstate New York, billed itself as “three days of peace and music” — and it was, probably, for most of the half a million people who turned up there — but four months later, at a festival at Altamont Raceway Park in Northern California, a gang of Hell’s Angels hired as security by the Rolling Stones stomped an eighteen‐year‐old African‐American boy to death in front of the stage.

Whatever illusions we still had about the live‐and‐let‐live, love‐the‐one-you’re‐with attitude of the ’60s were lost or abandoned at the bitter end of the decade. Peace and love were as dead as Wyatt and Billy after the rednecks shot‐gunned them off their motorcycles in the final frames of Easy Rider.

In 1970, a company of National Guards opened fire on 2,000 students protesting the American invasion of Cambodia on the campus of Kent State University in Ohio. Four students, including two women, were killed and nine were injured. Ten days later, police, supported by the National Guard, opened fire on protesting students at Jackson State University in Mississippi. Two were killed and twelve were injured. It appeared that the emergence of a cohesive, politicised youth counter‐culture had shaken up the status quo enough that the first reaction of those charged with maintaining it — the vestigial guardians of the Great Generation, the unambivalent defenders of the moral high ground and the guys who had fought the last ‘good’ war for us — had been to try, quite literally, to kill it. “They’re worse than the brown‐ shirts and the communist element and also the nightriders and the vigilantes,” the Republican governor of Ohio, James Allen Rhodes, said of the Kent State protesters in a fit of indignant hyperbole at a press conference, just twenty‐four hours before the fatal shootings. “They’re the worst type of people that we harbour...I think that we’re up against the strongest, well‐trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.”

The oldest of the four Kent State students killed was twenty, the youngest nineteen. Unsurprisingly, two of these Baby Boomers had had no part in the protest at all. They were walking from one lecture to another.

Part one of three.

First published as part of a single essay in Griffith Review, Australia, 2006.

#babyboomers#generationaldivides#the60s#youthculture#rocknroll#culturewar#vietnam#summeroflove#postwar

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

urban dragonborn

#UrbanStyle#AnimeInfluence#StreetFashion#YouthCulture#Butterflies#GoldenAccents#ContemplativePose#ModernArt#CharacterIllustration#FashionIllustration#EdgyLook#DigitalArtwork#TransformationSymbolism

0 notes

Text

earlier this year at ucla

#ucla bruins#ucla#photography#creative photography#youthculture#digital camera#digitialphotography#flash photography#student life#college#fashion photography#photoshoot#original art#my photos

0 notes

Text

The Global Impact of Pop Culture on Vietnam's Youth

Pop culture has become increasingly influential in today’s society. Young people are particularly drawn to the latest trends in music, fashion, and entertainment. They eagerly follow their favourite celebrities on social media and emulate their style. In Vietnam, K-pop has gained a massive following among the youth. They are captivated by the catchy melodies and synchronized dance routines of K-pop groups. Vietnamese fans often gather to learn the choreography and sing along to their favourite songs. However, it is important to note that pop culture is not just limited to music and entertainment. It also encompasses movies, TV shows, fashion trends, and even internet memes.

0 notes

Text

Is the Rice Purity Test only for college students?

The Rice Purity Test is not exclusively for college students; it is a poll intended to evaluate a singular's degree of blamelessness and encounters in different parts of life. Initially made by Rice College understudies, this test has acquired prevalence on school grounds, however it isn't restricted to this segment. Individuals of any age and foundations might decide to remove the test from interest or as a social movement. The test covers a scope of subjects, from heartfelt encounters to individual propensities, giving a mathematical score that mirrors one's apparent purity. It fills in as a carefree and diverting manner for people to look at and share their encounters.

#LifeExperiences#RicePurityTest#InnocenceLevel#SocialQuiz#PersonalHabits#YouthCulture#TrendingTests#MindfulLiving#SelfDiscovery#DigitalWellness

0 notes

Text

Millennials, reportedly essentially the most tattooed generation in Western society, are taking to TikTok to share their tattoo regrets with members of Gen Z, lest they too develop as much as rue their ink.

Although 13% of child boomers and 32% of Gen X-ers sport tattoos, following a 2022 YPulse examination, millennials at present carry the titl...

0 notes

Text

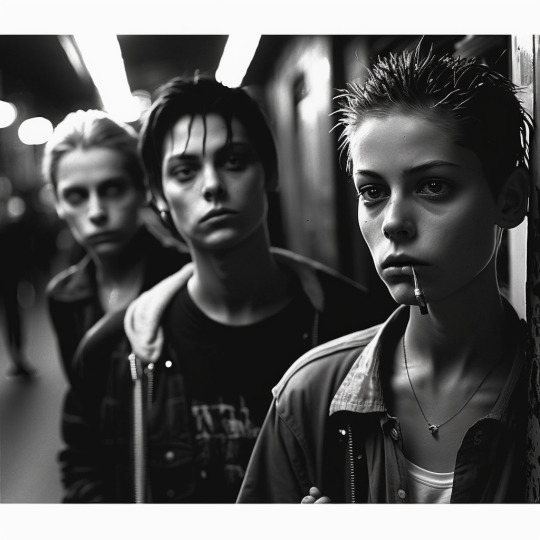

Looking for an edgy and cool photo? Check out this JPG image captured with ISO 200, f/4, and 1/60 sec settings! It features a group of attractive and rebellious teenagers standing in a dimly-lit alley, smoking cigarettes and drinking beer, evoking a moody and atmospheric vibe. The photo is inspired by the style of Larry Clark, showcasing the raw and unfiltered essence of youth culture.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Taking over the streets in NiZED Youth Culture 🔥 Seit wenigen Wochen ist die neue 23 Kollektion bei uns im Store erhältlich. . . Youth Culture Z Kapuzenpullover . . #nized #streetwear #streetwearstyle #trippyhoodie #youthculture (hier: Berlin, Germany) https://www.instagram.com/p/CmOfueJsCP9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

12:00 am

The Paladin Bin EP

#art#rave#illustration#nightlife#oilpastel#new years eve#sketchbook#underpainting#illustrator#editorial#artmagazine#profiledrawing#portrait#youthculture

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Another great bus advert showcasing my work for @stcgdigital @mertoncollege #education #youthculture #thefuture #londonadvertisingphotographer #happy @scoutprod_creatives @wonderfulmachine @curated_artists_inc @squint_box @squint_showcase @foundartists @photopolitic @assocphoto https://www.instagram.com/p/ClGIaufNqv5/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

#youthskills#youth#worldyouthskillsday#wysd#skills#education#youthskillsday#youthforchange#youthculture#nigeria#beshubhargava#youths#withinyou#drsmitadipankar#speakers

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Ocean Wide “When I was 15, I met a successful photographer and I remember thinking ‘well if he’s doing this as a job, maybe I could too.’” - Kane Ocean (successful) Photographer. Kane Ocean is a Montreal based photographer. Ocean is passionate about fashion, music and travel, so he’s in the right business then. Ocean manages the diverse aspects of his career as a freelance fashion photographer - working with clients like ‘SSENSE’ and ‘Dime’ - and co-leading his party and record label, ’00:AM’ which showcases local and global artists. Ocean’s photography is a thoughtful translation of fashion-fusing eccentricity which he brings to every shoot. This includes meticulous attention to develop the set, environment and lighting - down to scouting distinct models. Ocean is also known for his street photography and situational photography - capturing the experiences of youth and friends at play. Now he’s an author to - the first monograph from Ocean ‘WAYN’ is a tribute to youth culture in Canada and beyond. ‘WAYN’ by Kane Ocean is out now. #neonurchin #neonurchinblog #dedicatedtothethingswelove #suzyurchin #ollyurchin #art #music #photography #fashion #film #design #words #pictures #monograph #youthculture #friendship #nightlife #contemporary #photographer #skateboarding #canadian #musicscene #00AM #travel #fashionphotography #wayn #kaneocean (at Worldwide) https://www.instagram.com/p/CdsVX4fo5bU/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#neonurchin#neonurchinblog#dedicatedtothethingswelove#suzyurchin#ollyurchin#art#music#photography#fashion#film#design#words#pictures#monograph#youthculture#friendship#nightlife#contemporary#photographer#skateboarding#canadian#musicscene#00am#travel#fashionphotography#wayn#kaneocean

0 notes

Text

santa monica

1 note

·

View note