#whose time in power was referred to by contemporaries as her 'reign'

Note

Who do you think is the most successful of Henry’s wives child bearing aside??

I don't know how to measure success? 'Survived' is obviously Parr and to a greater extent Anne of Cleves, so that's sort of the Game of Thrones answer.

Anne Boleyn was, however, a greater landowner than her predecessor, and, actually, a greater landowner than any other Tudor consort. So, if we measure success by that, ie power held during the reign, not necessarily over time or the length of reign, I suppose it would be her?

#and by 'great' = largesse#so owned the most#katherynparr#if it's by who was regent it would be the first and final catherine; right ?#but i do think to some extent land is wealth and wealth is power#also anne is actually the only tudor consort#whose time in power was referred to by contemporaries as her 'reign'#which is not nothing.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Princess Louise Hippolyte of Monaco (1687-1731) by Jean Baptiste van Loo

About Louise Hippolyte of Monaco: Louise Hippolyte (10 November 1697 – 29 December 1731) was one of only two women to rule Monaco, reigning as Princess of Monaco from 20 February 1731 until her death in December the same year. She was the second daughter of Antonio I of Monaco and Marie de Lorraine-Armagnac. The second of six children born to her parents, she was the first of their children to survive infancy. She had sisters, but no brothers. Her father decided, with the permission of Louis XIV, that her future husband should assume the surname of Grimaldi and rule Monaco jointly with her. On 20 October 1715, at the age of eighteen, she married Jacques François Goyon, Count de Matignon. His candidacy was supported by King Louis XIV, who wanted to consolidate French influence in Monaco. Prior to this, Louise Hippolyte's father was eager to wed his daughter to a Grimaldi cousin. This marriage did not materialise due to the poor finances of the Grimaldis at the time. The marriage was not happy. Louise Hippolyte was described as a shy, while Jacques openly flaunted his mistresses in the royal court at Versailles. They had nine children together. Her father died on 20 February 1731. Louise Hippolyte traveled without her family from Paris to Monaco. As was customary in the case of female monarchs, it had originally been the plan to proclaim Jacques as her joint co-regent. However, it became clear that the people of Monaco did not welcome a Frenchman as co-ruler of Monaco and would prefer Louise Hippolyte as their sole ruler. Louise took advantage of this and took the oath as ruler of Monaco herself before Jacques had arrived. Finding himself without power, he soon returned to France.Princess Louise-Hippolyte ruled Monaco for seven months. She is described as a popular ruler during her short reign. She died of smallpox at the end of 1731.Following her death, her husband took power in Monaco, her son being a minor. Jacques neglected the affairs of Monaco and had to leave the country in May 1732. His ambition was to be declared regent until his son reached the age of 25, after which his son should abdicate his throne to him, but this was not accepted in Monaco. He abdicated in favor of their son, Honoré, the next year.

About the artist and his family: Jean-Baptiste van Loo (14 January 1684 – 19 December 1745) was a French subject and portrait painter.He was born in Aix-en-Provence, and was instructed in art by his father Louis-Abraham van Loo, son of Jacob van Loo (a painter of the Dutch Golden Age, known particularly for his mythological and biblical scenes. He was especially celebrated for the quality of his nudes to the extent that, during his lifetime, particularly his female figures were said to have been considered superior and more popular than those of contemporary and competitor Rembrandt.Though his father also painted, Jacob's success ensured that he would forever be referred to as the founder of the Van Loo family of painters; a dynasty which was influential in French and European painting from the 17th to the beginning of the 19th century.) Jean-Baptiste van Loo was patronized by the prince of Carignan, who sent him to Rome, where he studied under Benedetto Luti. In Rome he was much employed painting for churches.At Turin he painted Charles Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy and several members of his court. Then, moving to Paris, where he was elected a member of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, he executed various altar-pieces and restored the works of Francesco Primaticcio at Fontainebleau. He also painted portraits of aristocrats living in or visiting Paris. In 1737 he went to England. He also painted Sir Robert Walpole, whose portrait by van Loo in his robes as chancellor of the exchequer is in the National Portrait Gallery, London, and the prince and princess of Wales. He did not, however, practise long in England, because of his failing health; he retired to Paris in 1742, and afterwards to Aix-en-Provence, where he died on 19 December 1745. His likenesses were striking and faithful, but seldom flattering. (I might post more about his work and his family's)

#new post#historical fashion#costume drama#dress#period piece#new to tumblr#pretty#princess#portrait#painting#politics#royalty#royals#monaco#house of grimaldi#monte carlo#oil on canvas#oil painting#fun facts#historical drama#historical#fashion history#history#long post#arranged marriage#louis xiv#palace of versailles#versailles#art#artist

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myths around Kösem Sultan's execution / A Köszem szultána halála körüli legendák

One of the most frequently discussed topics about the Sultanate of Women is the brutal execution of Kösem Sultan. Usually, the casual people think that she was assassinated by her son-in-law Turhan Hatice Sultan during a long power struggle. We have plenty of accounts of the events, but there are quite a few of them that are contemporary. In this post, I would like to summarize what we know, who were the characters of the events, and what might have happened that night. In the comments section or in Tellonyme, I look forward to everyone's opinion and comment about the topic so that we can discuss it! :) If you don't know Kösem Sultan, you can read her biography HERE.

What do we know for sure?

- After Ibrahim's dethronement and execution, Kösem Sultan became a regent to her grandson Mehmed IV.

- Turhan, Mehmed’s mother, and Kösem Sultan were on different sides during the political games.

- Kösem Sultan was killed by her enemies on September 2, 1651.

- Turhan Hatice became the new regent, Kösem Sultan's executioners were not punished, but her supporters were soon killed.

Backstory

Kösem Sultan came to power for the second time in February 1640. Along with her crazy son, Ibrahim I, she began to rule the Ottoman Empire as regent. Everyone loved her, she had a huge experience in rule, she did a lot of charity. Everything seemed perfect, but her son, Ibrahim, soon came under the influence of bad advisers. Cinci Hoca was a religious leader in occult sciences who took advantage of the Sultan’s mental problems and seriously influenced him. As a result, the Sultan executed his Grand Vizier in 1644 and exiled his mother. He originally intended to send his mother to the island of Rhodes, but eventually, his concubines persuaded him to send her only to another palace. Kösem Sultan spent the next few years there in exile, but during that time she corresponded regularly with the statesmen and tried to keep everything under control. She probably wrote her well-known letter to Hezarpare Ahmed Pasha here, saying, "In the end, he will not leave you or me alive and we will lose control of the state again, thereby destroying our society." The situation deteriorated to the point that in 1647 Kösem Sultan and the new Grand Vizier, Salih Pasha and Seyhülislam Abdürrahim Efendi tried to dethrone Ibrahim but they failed. The next year, both the Janissaries and the Ulema joined the rebellion, and on August 8, 1648, the mad sultan was easily dethroned and imprisoned and his followers were removed from positions.

Ibrahim was succeeded by his son, Mehmed, who was barely 6 years old, andso he needed a regent. The statesmen asked Kösem Sultan for the honorary task. The position of regent was usually held by teachers, pashas, or mothers (in the case of Mehmed II, the Grand Vizier was regent; in Ahmed I, his mother and teacher; in Murad IV, and Ibrahim's case their mother), so Kösem Sultan was the first grandmother to become regent. According to the most accepted opinions, this happened because Mehmed’s mother, Turhan Hatice, was not even 25 years old at the time, too young and inexperienced to run the empire. Anyhow Kösem Sultan started her third regency and she constantly disregarded Mehmed’s mother, Turhan. Because of Turhan’s youth, she might truly would not have been the best regent, yet she had every right to control the harem. Kösem Sultan, however, did not allow this to the young woman either. So Turhan, in vain was the mother of the reigning sultan, all her duties were ruled by Kösem Sultan. Kösem Sultan gained more and more enemies both in the divan and the harem, so both places split into two sides: Kösem Sultan and her supporters and Turhan Sultan and her supporters.

Two opposite sides and characters

Kösem Sultan and her supporters

Kösem Sultan ruled the empire as a regent for decades, and when she was not a regent, she followed events as valide sultan. Earlier in her life, she worked together with most of the pashas. During her first regency, she said that she, as the representative of the ruler, intended to be there at the divan meetings in person. This was not allowed by the pashas and so she was forced to accept. During her third regency, however, she was not bowing before anyone’s will. She had lost all her sons, buried at least one daughter, sacrificed her whole life for the empire, so then she refused to compromise on anything anymore. She wished to rule the empire as an absolute monarch. And in the divan she dismissed everyone who disagreed with her. More and more people began to debate her right for ruling. One of her well-known divan speeches happed around this time. Kösem Sultan accused the Grand Vizier Sofu Ahmed Pasha of wanting to kill her, then she continued: “Thank God I survived four rulers and I ruled for a long time myself. The world will neither collapse nor reform with my death.”

Kösem Sultan went too far. She didn't just change the pashas she did not like but replaced them with Janissary officers. The Janissaries have served her with allegiance since the first regency of Kösem Sultan. Back then, in 1623, she went against everyone and gave the Janissaries a huge amount of money after Murad IV's accession to the throne. Although there were rebellions and disagreements, basically the Janissaries - but at least some of their corps - were loyal to Kösem Sultan. Representation of the Janissaries has been a thing for centuries, but to make Janissaries — or simply soldiers — vizieres was too much. Pashas learnt a lot and bore a lot to reach the highest possible positions and they were aware of how to be good veziers. This was their only aim and Kösem put Janissary officers there instead of educated statesmen. Everyone in the divan felt that Kösem Sultan wanted to build a military rule so that she could lead the empire in a way she liked. Thus, by 1651, only a few corps of Janissaries were actually on the side of Kösem in political terms. Although the people still loved her for her generous charity, in political terms their support did not mean much.

In addition to the growing tension with the pashas, Kösem Sultan had a rival in the harem also. Although most sources treat it as a fact that the relationship of Kösem Sultan and Turhan was terrible, there is no evidence to that effect. The relationship between the two of them only began to deteriorate over time, but in general, it can be said that Kösem Sultan just did not care about Turhan at all. She certainly looked down on her and didn't think much about Turhan. Kösem Sultan, although she had her own harem staff, did not have the most influential eunuch. Moreover, some said most of her servants also found her unworthy after realizing the way she treated Turhan. Perhaps it is no coincidence that so many sources mention a servant named Meleki Hatun, who famously switched sides and betrayed Kösem Sultan and began to strengthen Turhan’s side.

Turhan Hatice Sultan and her supporters

Turhan Hatice had more allies and so was in a better position in the harem than Kösem Sultan. She received help from an influential eunuch, Suleiman Agha. Suleiman aga was the leader of the harem agas, an ambitious eunuch with great power and contact system, with significant political influence. The harem was actually torn in two, thanks to the supporters of Kösem Sultan and Turhan Hatice. Both sides had their own chief eunuchs, which caused immense chaos within the harem, people did not know whose instructions to follow. And although the title of Valide Sultan belonged to Turhan Hatice as the mother of the sultan, the vernacular referred to her only as “small valide,” while Kösem Sultan was called “big valide”. Suleiman Agha's support, however, was worth its weight in gold. The eunuch looked primarily at his own interests throughout his life, and he had a great understanding of how to exploit and influence people. This is precisely why the possibility arises that it was Suleiman who set Turhan up and turned her against Kösem Sultan. Perhaps it was Suleiman who - hoping for his own rise from the young valide - persuaded her to take what was her right. In addition, Suleiman Agha was very liked by the young sultan, becoming a kind of father figure for the boy. Of course, it is not my intention to underestimate the role of Turhan in the events, but at the same time, I feel that the role of Suleiman Agha is actually underrated and I would like to make that clear. I’m not saying Turhan was a naive girl led by the evil Suleiman Agha, I just think that without Suleiman’s support and incitement, Turhan probably wouldn’t have, or much later, confronted Kösem Sultan.

In addition to Suleiman, three other major eunuchs also sided with Turhan: Hoca Reyhan Agha, Lala Hajji Ibrahim Agha, and Ali Agha. Hoca Reyhan Agha was closest to Turhan as his associate and religious leader, but Lala Hajji Aga was also a long-term partner in Turhan’s life. In addition to the eunuchs, we must also mention Meleki Hatun, whose legend is well known. According to this, she was the one who betrayed the plan of Kösem Sultan to Turhan, thus saving the little Sultan Mehmed from death and dethronement. However, the reality is probably less romantic. It is unlikely that a previously insignificant, never-ever mentioned servant like Meleki would have known about Kösem Sultan's plans and so could betray her. Certainly, Meleki was given a bigger role in the legend than she actually had. Maybe Meleki has agreed to be a scapegoat, testifying against Kösem Sultan if she gets goods in return. Given what a huge fortune Meleki gained after Kösem Sultan’s death, we can’t rule out this option either. Even if Meleki brought supporters for Turhan within the harem, she could have had quite a bit of an impact on the whole event. In addition to Turhan, the key figure was Suleiman Agha, who also had a close relationship with the divan, so he could easily connect members of the divan who were dissatisfied with Kösem Sultan. The most influential supporter was none other than the Grand Vizier, Siyavuş Pasha, but practically the entire divan turned against Kösem Sultan so far. It should also be mentioned that although most formations of the Janissaries were impartial or were on Kösem Sultan's side, the Sipahies tended to the group of Turhan and her supporters.

What led to the tragic night?

Before turning to the immediate causes, we need to jump back a bit in time to better understand Kösem Sultan's behavior. As is well known, Ibrahim I was succeeded by his son, Mehmed, barely 6 years old, who needed a regent. The statesmen asked Kösem Sultan for the honorary task. However, the request was rather strange. Why is that? The regent position was usually held by teachers, pashas, or mothers, and Kösem Sultan was none. Moreover, Kösem Sultan rejected the request for the first time on the grounds that she no longer has the strength to rule further.

Why did Kösem Sultan take on the task? Did she really want to retire?

To understand Kösem Sultan's thoughts, we need to jump a little further back in time. Kösem Sultan was in exile for years during Ibrahim's reign. From her exile, she repeatedly attempted a coup against her own son. From one of her surviving letters in exile, it is clear that she was part of the coup that eventually dethroned her son. Outwardly, however, she showed a very different picture. After Ibrahim was shut down, they wanted to put his son, Mehmed, on the throne. Kösem Sultan then met with the statesmen at Topkapi Palace to discuss with them what Ibrahim's fate should be. They negotiated for hours, but Kösem Sultan all along refused to give Ibrahim's eldest son to the statemen. The statesmen had to publicly convince Kösem Sultan for hours. Kösem Sultan who had previously done everything to dethrone her son is now standing by his son. Why? Of course, we will never know exactly what happened in her mind. However, it seems probable, that Kösem Sultan wanted to keep the image of a loving mother in front of the soldiers and the people. If she would just agree to Ibrahim's dethronement and Mehmed's enthronement that would be strange from a loving mother. Therefore, she held a sham debate with the pashas not to lose the sympathy of the people, but at the same time to keep the empire safe. Kösem Sultan was an experienced politician who was able to rule for years, and her loving and caring mother image was essential to that. Thus, with Kösem Sultan's consent, Sultan Ibrahim was eventually closed up and Mehmed has proclaimed their new sultan. Perhaps the first rejection of regency in 1648 was also part of a play like this. Kösem Sultan maybe felt the people expect this of her, so she offered to retire, while maybe in the background she had already agreed with the pashas.

And why did the members of the divan let Kösem Sultan to be the regent? After all, any of the members of the divan or even Mehmed's teacher could have applied for the task. And that would give huge power to them. So why did they give this opportunity to Kösem Sultan?

Ibrahim I was executed on August 18, 1648. Some say Kösem Sultan gave her consent to the execution but it cannot be ruled out that the execution took place behind her back. As I mentioned above, the mother of the dethroned or assassinated sultans has traditionally retreated to the Old Palace, where they lived their remaining years politically inactive. In her case, however, this did not happen. This raises the possibility that Kösem Sultan was unaware of Ibrahim’s execution and the pashas tried to reconcile the shattered woman with this gesture. Maybe Kösem gave her consent, knew what will happen, but still in the end she couldn't bear the pain. Either way, after the execution Kösem Sultan has changed. She turned against the pashas with whom she had always cooperated before. Whichever version is true, we can clearly see that the Kösem Sultan who became a regent to Mehmed IV, was no longer the same woman who had previously been considered the beloved mother of the empire.

But who ordered the execution of Ibrahim? Do we know? No, we do not know. Actually any of the statesmen could do it, but either Suleiman Agha or Turhan Sultan could make the little sultan to sign the fetwa petition and then send it to the Seyhülislam to authorize. Anyhow, the fetwa was authorized with full right, as Ibrahim was very harmful to the empire.

The murder

As can be seen from the above summary, Kösem Sultan was trying to build an absolute monarchy in which no one but a few Janissary corpses supported her, so a huge team gathered against her. According to the well-known version, over time, the strife between Kösem Sultan and the statesmen escalated to the point that, with the support of Turhan Hatice, the statesmen tried to remove her from her position. Kösem Sultan in response to this planned to dethrone Sultan Mehmed and put her other grandson on the throne instead. To do this, she wanted to let the Janissaries into the palace so that they could carry out the coup at night, which is why she left the gate to the harem open for the night. However, Kösem Sultan's plan was revealed to her enemies. According to some it was a servant named Meleki Hatun, who betrayed Kösem and told her plans to Turhan. Thus, as soon as the men of Kösem Sultan opened the gate on September 2, 1651, the men of Turhan Hatice, led by Chief Eunuch Suleiman Agha, closed it and sent an execution squad to the residence of Kösem Sultan. When she heard knocking on her door Kösem Sultan thought that her own allies had come, so she shouted at them, “Have you come?”. However, instead of the voice of the Janissaries, she heard the voice of the eunuch Suleiman Agha, which made her panic and flee. It’s not exactly known if she did get out of her apartment and if yes then how because the descriptions don’t match. Some said she hid in a closet inside her apartment, others said she tried to get to the Janissaries, but she couldn’t get through the closed gate, so she finally hid in the room next to the gate.

The execution squad, which consisted of several eunuchs (Suleiman Agha, Hoca Reyhan Agha, Lala Hajji Ibrahim Agha, and Ali Agha, as well as some unknown eunuchs) continued the search. Kösem Sultan hid in a closet from which the edge of her dress protruded, revealing her hiding place. When they found her, she threw money at her executioners, trying to pay them off, but she had no chance against Turhan's loyal men. Legend has it that while the men tried to capture and strangle the valide sultan they ripped out her diamond earrings - which she had received from Sultan Ahmed - from her ears; torn apart her clothes as they tried to take away the precious ornaments from her. Kösem Sultan beyond her sixties fought very hard but in the end, the eunuchs overcame her. Some say she was strangled with her own hair, others said with a curtain. She survived the first strangulation attempt but did not survive the second.

However, there are several points in the story above that raise doubts:

- Kösem Sultan's problem was not Mehmed but was the pashas, Turhan and Suleiman Agha. Then why didn't she get rid of them? Wouldn’t it have been easier and more logical to kill these people than to dethrone one child sultan for the benefit of another child? Of course, we can justify this with the fact that Kösem Sultan was no longer sane, so let’s not even look for logic in her actions. However, it may also raise the possibility that perhaps Kösem Sultan was completely or at least partially innocent throughout the series of events. She may not have planned anything with the Janissaries, the whole plan was only invented by Turhan and her men to legitimize their own actions. However, it contradicts that the Janissaries were indeed preparing to gather on the tragic night, and it is unlikely that Turhan and her team could successfully cheat the Janissaries without Kösem Sultan realizing it. It is possible that Kösem Sultan was indeed prepared for a minor coup, but it was perhaps not directed against Mehmed. Kösem Sultan had to realize that besides the pashas, Suleiman Aga was behind the "rebellious" behavior of Turhan and Mehmed. I think Kösem Sultan planned a smaller coup in which she would have got rid of the eunuchs and servants she didn’t like and would have scared Mehmed and Turhan. This would have ensured her own power and that neither Turhan nor Mehmed would question her anymore.

- Why was Kösem Sultan killed in such a strange way? After all, the lawful, usual method of execution was by an execution squad with Seyhülislam fetwa and silk/bow string. (It is important to note, however, that female members of the dynasty have not been executed before, women have typically been punished only with exile.) Kösem Sultan in contrast was killed by inexperienced eunuchs, with a kind of fake fetwa, and by her own hair or a curtain. The question arises that perhaps the execution of Kösem Sultan was not even planned. If the execution would be planned, executioners could clearly kill her after a legal fetwa. About the fetwa... There was, of course, a fetwa, but the temporality is somewhat disturbed by the fact that the Seyhülislam was replaced by one of Turhan's trusted men just when the execution took place. Precisely because of this, and because of the unusual brutality of the execution, there is a possibility that perhaps the execution of Kösem Sultan was not originally planned, only things slipped out of control, and in the heat of the moment, the Eunuchs executed Kösem Sultan. In retrospect, to legalize the events, they produced a fetwa with the new Seyhülislam.

- But then who and why did finally decide that Kösem Sultan should die? Turhan was not present at the events, and since the murder was not planned in advance - based on the fetwa and executioners - I would remove her from the list of suspects. Of course, it cannot be ruled out that Turhan Hatice Sultan and Suleiman Agha talked about this possibility also. It is more probable, however, that they originally merely wanted to scare Kösem Sultan, to show her that she had been exposed, that time had passed over her. In my opinion, Turhan hoped that Kösem Sultan would admit her defeat and simply retire to the Old Palace. It would have been too risky to kill a venerate and beloved valide, especially knowing that none of the female members of the dynasty had ever been executed before. They probably wanted to resign her, but so far there was nothing to lose for Kösem Sultan. The only thing that still made her vivid was power, so she certainly objected to the idea of forced retreat. When Suleiman Agha realized that Kösem Sultan was not listening to them, perhaps out of fear, he decided they had to kill her. After all, if the enraged Kösem Sultan had come out of the palace, Suleiman and the other eunuchs would have found themselves headless at once. Although there is no evidence of it, my personal opinion is that Suleiman may have wanted this from the first minute, as he knew full well that Kösem Sultan would never retire. Either way, the eunuchs eventually defeated and executed the elderly valide in a way that could not be called professional at all.

- Can we completely rule out that Kösem Sultan was executed with a truly legal fetwa and by an execution squad? Unfortunately, this cannot be ruled out either. The English ambassador, for example, reported that an execution squad had killed Kösem Sultan after a fetwa requested by the young sultan. He said that the execution happened in front of Mehmed eyes. We must admit though that the English ambassador was not among the best-informed ones. It is likely that everyone at the time believed that the fetwa was pre-issued. Only later, after historians’ research, it became very possible that the fetwa was presumably made after the execution of Kösem Sultan. It is not seems reasonable that Kösem Sultan would have been executed before the eyes of her 10-year-old grandson, Mehmed. Turhan tried very hard to protect her son, unlikely to have exposed him to such a trauma. Mustafa Naima agrees with the English ambassador that the execution was planned in advance, but he said it was not the eunuchs but an execution squad that killed Kösem Sultan. However, then why was the execution brutal? Why wasn't there a silk/bow string? Why was it performed by unfit eunuchs?

The aftermath of the murder

To prevent any resistance, during the night, Turhan Hatice and her men removed all statesmen who would have endangered them. The first man to be appointed that night was Ebu Said Efendi, the new Seyhülislam. He was the one who eventually issued the fetwa for the execution of Kösem Sultan (in retrospect). Turhan then sent a message to all statesmen and soldiers to immediately go to an audience where they would take allegiance to Sultan Mehmed. Most, out of fear or out of sincere feelings, immediately approached the Sultan, and those who did not, the new Seyhülislam issued a fetwa for them. Thus it became lawful to execute the supporters of Kösem Sultan, since they did not appear before the Sultan either. And the rebellious Janissaries were thus stigmatized as traitors and were legally executed. For commoners, they became the scapegoat for the death of Kösem Sultan. After the murder, Kösem Sultan was transported to the Old Palace, where her body was prepared for the funeral. She received an imperial funeral, and the people of Istanbul voluntarily held 3-day mourning, closing all shops and stores. Kösem Sultan has always been popular among the people, but interestingly the same people did not turn against Turhan because of the death of Kösem Sultan, in fact, Turhan became as loved and revered valide sultan just as Kösem Sultan was.

What happened to the real culprits? Turhan and Mehmed escaped, of course, but it is questionable whether they had any part in the murder at all. It is true that a rebellion in 1656 seriously shook their power, but in the end, they did not lose it. The main reasons for this were the weak Grand Veziers, the resurgent Celali rebellion, and the war with the Venetians. Due to the war people of the capital did not get enough grain, the soldiers were not properly paid, but ordinary people were also increasingly dissatisfied, especially angered by the extreme wealth of those close to the Sultan. Eventually, under the leadership of the Janissaries and Spahis, the people revolted on the fourth of March 1656. During the rebellion, several of those close to the sultan were brutally executed, the whole capital was ravaged. The mob hung all 31 people on trees next to the Blue Mosque. Among them was Meleki Hatun, whom the sultan especially loved. Although the capital has been shaken by riots in the past, such a rebellion has never happened before. Not only did the soldiers revolt, but the people also stood by the soldiers as one. Everyone closed their shops, a general strike took place during the rebellion.

Suleiman Agha was no longer in power when the rebellion took place and perhaps this held his head on his neck. After the assassination of Kösem Sultan, he became the chief black eunuch, but he could only enjoy the position until July 1652. Suleiman continued to stretch beyond his blanket, trying to change political issues that had nothing to do with him. Turhan Hatice also began to realize that Suleiman was not on their side at all, but only on his own. Of particular interest is that Lala Ibrahim Agha convinced Turhan of this, who himself took part in the execution of Kösem Sultan. Lala Ibrahim Agha was Turhan’s personal eunuch and he never longed (or wisely didn’t show her) for a higher position. Turhan was thus finally dismissed Suleiman Agha in 1652 and exiled him to Egypt. The refined eunuch even invented himself in exile, growing into an influential figure who became one of the main figures in Cairo’s local politics. He died in 1676/7.

Epilogue

We will probably never know exactly what led to the execution and how it took place. Nor was my aim with the post to present a perfect solution in the manner as Hercule Poirot usually does. I merely wished to shed light on the fact that the generally known and accepted theory should be regarded with some healthy doubts. The fact that it is the most generally accepted theory, does not mean it is the most thorough. There are plenty of question marks, dubious information which makes it clear that this whole situation was more complicated than two women fighting for domination over the harem.

Kösem Sultan was the sultana who broke the highest, who could have been at the top for a long time, but from the great heights, she finally fell down and became the only murdered valide sultana ever. Kösem Sultan had several titles during her life: Naib-i Sultanat (regent of the Ottoman Empire), Umin al-Mu'minin (mother of all muslims), Büyük Valide Sultan (great Valide Sultan), Valide-i Sehide (martyred mother), Valide-i Maktule (murdered mother), Valide-i Muazzama (magnificent mother).

Used sources: M. Kocaaslan - IV. Mehmed Saltanatında Topkapı Sarayı Haremi: İktidar, Sınırlar ve Mimari; L. Peirce - The Imperial Harem; Ö. Kumrular - Kösem Sultan: iktidar, hırs, entrika; C. Finkel - Osman’s Dream: the History of the Ottoman Empire; M. P. Pedani - Relazioni inedite; N. Sakaoğlu - Bu Mülkün Kadın Sultanları; G. Börekçi - Factions and Favorites at the Courts of Sultan Ahmed I and His Immediate Predecessors; F. Davis - The Palace of Topkapi in Istanbul; Faroqhi - The Ottoman Empire and the World; C. Imber - The Ottoman Empire 1300-1650; F. Suraiya, K. Fleet - The Cambridge History of Turkey 1453-1603; F. Suraiya - The Cambridge History of Turkey, The Later Ottoman Empire, 1603–1839; Ö. Düzbakar - Charitable Women And Their Pious Foundations In The Ottoman; G. Junne - The black eunuchs of the Ottoman Empire, Networks of Power in the Court of the Sultan.

* * *

A Nők szultánátusának egyik legtöbbször tárgyalt témája Köszem szultána brutális kivégzése. Általában a laikusok elintézik annyival, hogy Köszem szultánát menye, Turhan Hatice gyilkoltatta meg hosszas hatalmi harc lezárásaként. Rengeteg beszámoló áll rendelkezésünkre az eseményekről, ám meglehetősen kevés van köztük, mely konkrétan korabeli lenne. Ebben az írásban szeretném összegezni, hogy mit tudunk, kik voltak a szereplők az eseményekben és hogy mi történhetett azon a bizonyos éjjelen. A kommentszekcióban várom mindenki véleményét, megjegyzését a témáról, hogy meg tudjuk vitatni a posztot! :) Aki nem ismerné Köszem szultánát, az ITT tudja elolvasni életrajzát.

Mit tudunk biztosan?

- Köszem I. Ibrahim trónfosztása és kivégzése után régens lett unokája IV. Mehmed mellett.

- Turhan, Mehmed anyja és Köszem külöböző oldalon álltak a politikai játszmák során.

- Köszemet 1651. szeptember 2-án meggyilkolták ellenségei.

- Turhan Hatice lett az új régens, Köszem gyilkosai nem lettek megbüntetve, támogatóitól azonban rövidesen megszabadultak.

Előzmények

Köszem szultána 1640 februárjában másodjára került hatalomra. Zavart elméjú fia, I. Ibrahim mellett régensként kezdte irányítani az Oszmán Birodalmat. Köszemet mindenki szerette, az uralkodásban hatalmas tapasztalata volt, rengeteget jótékonykodott. Minden tökéletesnek tűnt, azonban fia, Ibrahim hamarosan rossz emberek befolyása alá került. Cinci Hoca okkult tudományokkal foglalkozó vallási vezető volt, aki kihasználta a szultán mentális problémáit és komolyan befolyásolta őt. Ennek az lett az eredménye, hogy a szultán 1644-ben a nagyvezírét kivégeztette, édesanyját pedig száműzte. Eredetileg Rodosz szigetére szándékozta küldeni anyját, de végül ágyasai meggyőzték, hogy csak egy másik palotába küldje. Köszem elkövetkezendő éveit ott töltötte száműzetésben, ám ezalatt az idő alatt is rendszeresen levelezett az államférfiakkal és igyekezett kézben tartani mindent. Valószínűleg itt írta meg jól ismert levelét is Hezarpare Ahmed Pasának, mely így szólt: “Végül sem titeket, sem engem nem hagyna életben és újra elveszítenénk az uralmat az állam felett, ezzel pedig lerombolnánk társadalmunkat.” Odáig fajult a helyzet, hogy 1647-ben Köszem szultána és az új nagyvezír, Salih Pasa és a Seyhülislam Abdürrahim Efendi megpróbálták trónfosztani Ibrahimot, azonban lebuktak. A következő évben a janicsárok és az ulema is csatlakozott a lázadáshoz és 1648 augusztus 8-án könnyűszerrel trónfosztották és bebörtönözték az őrült szultánt, követőit pedig eltávolították a pozíciókból.

Ibrahimot a trónon fia, az alig 6 éves Mehmed követte, aki mellett szükség volt egy régensre. Az államférfiak Köszemet kérték fel a megtisztelő feladatra. A régensi pozíciót általában tanítók, pasák vagy édesanyák látták el (II. Mehmed esetében a nagyvezír volt régens, I. Ahmednél anyja és tanítója, IV. Muradnál és I. Ibrahimnál anyjuk), így Köszem volt az első nagymama, akiből régens lehetett. Erre a legelfogadottabb vélemények szerint azért kerülhetett sor, mert Mehmed édesanyja, Turhan Hatice még 25 éves sem volt ekkor, túl fiatal és tapasztalatlan volt a birodalom irányításához. Köszem tehát belekezdett harmadik régensségébe és folyamatosan semmibe vette Mehmed édesanyját, Turhant. Turhan fiatalsága okán talán tényleg nem lett volna jó régens, ugyanakkor a hárem irányításához minden joga megvolt. Köszem viszont ezt sem engedte meg a fiatal nőnek. Turhan tehát hiába volt a regnáló szultán anyja, minden feladatkörét Köszem uralta. Emellett Köszem a divánban is egyre több ellenségre tett szert, így a hárem és a divan is két oldalra szakadt: Köszem támogatóira és Turhan támogatóira.

Két, szemben álló oldal és a szereplők

Köszem oldala

Köszem évtizedeken át uralta régensként a birodalmat, amikor pedig nem régens volt, valideként követte figyelemmel az eseményeket. Életének korábbi szakaszában a legtöbb pasa mellette állt, ami nem volt elmondható harmadik régensségéről. Köszem első régenssége alatt is jelezte, hogy ő, mint az uralkodó reprezentálása ott kíván lenni a divan gyűléseken személyesen. Ezt akkor a pasák nem engedték meg neki, amit ő kénytelen-kelletlen el is fogadott. Harmadik régenssége során azonban szó sem lehetett arról, hogy meghajoljon bárki akarata előtt. Elveszítette összes fiát, legalább egy lányát is eltemette már, egész életét a birodalomnak áldozta, nem volt hajlandó többé bármiben is kompromisszumot kötni. Gyakorlatilag egyeduralkodóként kívánta irányítani a birodalmat. A divanban pedig aki nem értett vele egyet, azt eltiporta és menesztette. Köszem jogát az uralkodáshoz egyre többen kezdték el vitatni, egyik ilyen divan vita során hangzott el a jól ismert beszéde is. Ekkor Köszem megvádolta a nagyvezír Sofu Ahmed Pasát azzal, hogy meg akarta őt öletni, majd így folytatta: “Istennek hála négy uralkodót segítettem és én magam is hosszú ideig uralkodtam. A világ nem fog sem összeomlani sem megreformálódni a halálommal.”

Köszem azonban nem elégedett meg a pasák megalázásával, tanácsaik el nem fogadásával. Még csak nem is neki tetsző más pasákra cserélte le őket, hanem janicsárokat kezdett vezíri rangra emelni. A janicsárok Köszem első régenssége óta hűséggel szolgálták az asszonyt, amiért az mindenkivel szembe menve 1623-ban hatalmas trónralépési jussot adott a janicsároknak IV. Murad trónralépése után. Bár voltak lázadások és egyet nem értések, alapvetően a janicsárok - de legalábbis néhány hadtestük - hűségesek voltak Köszemhez. A janicsárok képviselete évszázadok óta működött, azonban az, hogy janicsárokat - vagy egyszerűen katonákat - tegyenek vezírré a kitanult államférfiak helyett, több volt a soknál. Mindenki úgy érezte a divanban, hogy Köszem egy katonai uralmat kíván kiépíteni, hogy a neki tetsző módon vezethesse a birodalmat. Így Köszem oldalán 1651-re tulajdonképpen csak a janicsárok néhány hadteste állt politikai értelemben. Bár a nép továbbra is szerette őt bőkezű jótékonykodása miatt, politikai értelemben az ő támogatásuk nem jelentett sokat.

Amellett, hogy a pasákkal egyre nőtt a feszültség, Köszem a háremben is riválisra akadt. Bár a legtöbb forrás tényként kezeli, hogy Köszem és menye, Turhan viszonya tragikus volt, nincs erre utaló bizonyíték. Kettejük viszonya csak az idő előrehaladtával kezdett megromlani, általánosan azonban inkább az mondható el, hogy Köszem egyáltalán nem foglalkozott menyével. Mindenbizonnyal lenézte és nem tartotta sokra Turhant, így komolyan sem vette a nőt. Köszemnek bár megvolt a saját hárem személyzete, a legbefolyásosabb eunuch nem volt a kezében. Mindemellett egyesek szerint szolgálói nagyrésze is méltatlannak találta, ahogy Köszem Turhannal bánt. Talán nem véletlen, hogy oly sok forrás említi a Meleki Hatun nevű szolgálót, aki híresen oldalt váltott és Köszemet elárulva Turhan oldalát kezdte erősíteni.

Turhan Hatice oldala

Turhan Hatice a háremben jobban állt, mint Köszem. Segítséget kapott egy befolyásos eunuchtól, Szulejmán agától. Szulejmán aga volt a hárem agák vezetője, aki nagy hatalommal és kapcsolatrendszerrel rendelkező, ambíciózus eunuch volt, jelentős politikai befolyással. A hárem tulajdonképpen két oldalra szakadt, Köszem és Turhan Hatice támogatóira. Mind a két oldalnak megvolt a saját főeunuchja, ami hatalmas káoszt okozott a háremen belül, az emberek nem tudták, kinek az utasításait kövessék. És bár a valide szultána titulus a szultán anyjaként Turhan Haticét illette meg, a köznyelv csak “kis valide”-ként hivatkozott rá, míg Köszem volt a “nagy valide”. Szulejmán Aga támogatása ugyanakkor aranyat ért. Az eunuch első sorban a saját érdekeit nézte egész élete során, azonban remekül értett ahhoz, hogyan használjon ki és vezessen meg embereket. Épp emiatt felmerül annak a lehetősége is, hogy Szulejmán volt az, aki Turhant felbújtotta és Köszem ellen hangolta. Talán Szulejmán volt az, aki saját felemelkedését remélve a fiatal validétől, meggyőzte arról, hogy vegye el ami a saját jussa. Emellett Szulejmán Aga az ifjú szultánnal is megkedveltette magát, egyfajta apafigurává vált a fiú számára. Természetesen nem célom alábecsülni Turhan szerepét az eseményekben, ugyanakkor úgy érzem, hogy Szulejmán Aga szerepe ténylegesen alábecsült és ezt szeretném mindneképpen érzékeltetni. Nem azt mondom, hogy Turhan egy naíva volt, akit megvezetett a csúf, rossz Szulejmán Aga, csupán azt gondolom, hogy Szulejmán támogatása és felbújtása nélkül, Turhan valószínűleg nem, vagy sokkal később szállt volna szembe Köszemmel.

Szulejmán mellett három másik jelentősebb eunuch is Turhan oldalán állt, Hoca Reyhan Aga, Lala Hajji Ibrahim Aga és Ali Aga. Hoca Reyhan Aga állt legközelebb Turhanhoz, mint társalkodója és vallási vezetője, de Lala Hajji Aga is hosszútávú partner volt Turhan életében. Az eunuchok mellett meg kell említenünk Meleki Hatunt is, akinek legendája jól ismert. Eszerint ő volt az, aki Köszem tervét elárulta Turhannak, ezzel megmentve a kis Mehmed szultánt a haláltól és trónfosztástól. A valóság azonban valószínűleg kevésbé romantikus. Valószínűtlen, hogy egy korábban sosem említett, jelentéktelen szolgáló, mint Meleki tudott volna Köszem terveiről és el tudta volna árulni. Minden bizonnyal Melekit csupán oldalváltása miatt ruházták fel nagyobb szereppel, mint ami valójában volt. Talán Meleki elvállalta, hogy lesz bűnbak, tanúskodik Köszem ellen, ha cserébe javakat kap. Legalábbis tekintettel arra, hogy Meleki milyen hatalmas vagyonra tett szert Köszem halála után, nem zárhatjuk ki ezt az opciót sem. Meleki ha a háremen belül hozott is támogatókat Turhan számára, az egész eseményre meglehetősen kevés ráhatása lehetett. A kulcs figura Turhan mellett Szulejmán aga volt, akinek komoly kapcsolata volt a divánnal is, így könnyedén tudta csapatukhoz kapcsolni a divan Köszemmel elégedetlen tagjait is. A legbefolyásosabb támogató nem volt más, mint a Nagyvezír, Siyavuş Pasa, de gyakorlatilag szinte a teljes divan Köszem ellen fordult eddigre. Azt is meg kell említeni, hogy bár a jancsiárok legtöbb alakulata pártatlan vagy Köszem párti volt, a szpáhik inkább húztak a Turhan támogatói csoport felé.

Mi vezetett a tragikus éjszakához?

Mielőtt a közvetlen okokra rátérnék, kicsit vissza kell ugranunk az időben, hogy jobban megérthessük Köszem viselkedését. Mint ismert, trónfosztása után, I. Ibrahimot a trónon fia, az alig 6 éves Mehmed követte, aki mellett szükség volt egy régensre. Az államférfiak Köszemet kérték fel a megtisztelő feladatra. Ugyanakkor a felkérés meglehetősen furcsa volt. Miért is? A régensi pozíciót általában tanítók, pasák vagy édesanyák látták el, Köszem pedig egyik sem volt. Sőt, Köszem a felkérést először elutasította arra hivatkozva, hogy már nincs ereje tovább uralkodni.

Miért vállalta el Köszem mégis a feladatot? Valóban vissza akart vonulni?

Ahhoz, hogy megértsük Köszem gondolatait, még egy kicsit visszább kell ugranunk az időben. Köszem Ibrahim uralkodása során száműzetésben volt éveken át. Száműzetéséből pedig többször kísérelt meg puccsot saját fia ellen. Egyik száműzetésben írt levele alapján egyértelmű, hogy részese volt a puccsnak, mely végül fiát trónfosztotta. Kifelé azonban egészen más képet mutatott. Miután Ibrahimot elzárták, trónra szerették volna léptetni fiát, Mehmedet. Köszem szultána ekkor találkozott a Topkapi Palotában az államférfiakkal, hogy megvitassa velük mi legyen Ibrahim sorsa. Órákon át tárgyaltak, Köszem azonban végig megtagadta, hogy kiadja Ibrahim legidősebb fiát, Mehmedet. Így pedig nem lehetett őt kikiáltani szultánnak. Az államférfiaknak órákon keresztül kellett nyilvánsoan győzködniük Köszemet. Az a Köszem, aki korábban mindent elkövetett fia trónfosztásáért, most fia mellett állt ki. Miért? Természetesen sosem fogjuk megtudni, hogy Köszem fejében pontosan mi játszódott le. Valószínűnek tűnik azonban, hogy Köszem szerette volna megtartani a katonák és nép előtt a szerető anya képét, melybe nem fért bele saját fiának trónfosztása. Ezért egy álvitát tartott a pasákkal, hogy ne veszítse el a nép szimpátiáját, de ugyanakkor a birodalomnak is jót tegyen. Köszem tapasztalt politikus volt, aki éveken át tudott vezető szerepben maradni, ehhez pedig nélkülözhetetlen volt az imázs is. Így végül Köszem beleegyezésével elzárták Ibrahim szultánt, Mehmedet pedig új szultánjukká kiáltották ki. Talán a régensség első elutasítása is egy ehhez hasonló színjáték része volt. Köszem talán úgy érezte, hogy a nép ezt várja tőle, ezért felajánlotta visszavonulását, miközben talán a háttérben már régen megegyezett a pasákkal.

És a divan tagjai miért hagyták, hogy Köszem legyen a régens? Hiszen a divan tagjai közül akárki vagy akár Mehmed tanítója is jelentkezhetett volna a feladatra. Ez pedig hatalmas befolyást tett volna a férfiak kezébe. Miért engedték hát akkor át ezt a lehetőséget Köszemnek?

I. Ibrahimot 1648. augusztus 18-án kivégezték. Egyesek szerint Köszem szultána beleegyezését adta fia kivégzésébe, ám az sem zárható ki, hogy a kivégzés a háta mögött történt meg. Mint már fentebb említettem a trónfosztott vagy meggyilkolt szultánok édesanyja a tradíció szerint a Régi Palotába vonult vissza, ahol politikamentesen élték hátralévő éveiket. Köszem esetében azonban nem ez történt. Ez felveti annak eshetőségét, hogy Köszem nem tudott Ibrahim kivégzéséről és a pasák ezzel a gesztussal igyekeztek kiengesztelni az összetört nőt. De akkor ki rendelte el Ibrahim kivégzését? Gyakorlatilag bárki megtehette az államférfiak közül, de akár Szulejmán aga vagy Turhan is aláírathatta a fetwa kérvényt a kis szultánnal, melyet aztán a Seyhülislam teljes joggal engedélyezett, hiszen Ibrahim nagyon kártékony volt a birodalomra nézve. Akárhogyan is, Köszem a kivégzés után megváltozott. Vagy azért fordult a pasák ellen - akikkel korábban mindig együttműködő volt -, mert azok átverték őt Ibrahim kivégzésével kapcsolatban; vagy egyszerűen anyai szíve nem bírta elviselni, hogy beleegyezését adta fia kivégzésébe és megbomlott az elméje. Bármelyik verzió is igaz, azt tisztán látjuk, hogy az a Köszem, aki IV. Mehmed mellett régens lett, már nem ugyanaz az ember volt, akit korábban a birodalom imádott anyjának tekintettek.

A gyilkosság

Ahogy a fenti összefoglalásból is kiderül, Köszem egyeduralmat próbált kiépíteni, melyben néhány janicsár hadtesten kívül senki nem támogatta, így hatalmas csapat gyűlt össze ellene. A jól ismert verzió szerint, idővel a viszály Köszem és az államférfiak között odáig fajtult, hogy Turhan Hatice támogatásával az államférfiak megpróbálták Köszemet eltávolítani pozíciójából. Köszem válaszul erre azt tervezte, hogy trónfosztja IV. Mehmed szultánt és helyette másik unokáját ülteti a trónra. Ehhez a janicsárokat be kívánta engedni a palotába, hogy azok az éj leple alatt elvégezzék a puccsot, emiatt nyitva hagyatta éjszakára a hárem bejáratát. Köszem terve azonban ellenségei fülébe jutott, egyesek szerint egy Meleki nevű szolgáló által. Így amint Köszem emberei 1651. szeptember 2-án, kinyitották a kaput, Turhan Hatice emberei, a főeunuch Szulejmán Aga vezetésével bezáratták azt és kivégzőosztagot küldtek Köszem szultána lakrészébe. Mikor emberei Köszem lakrészéhez érve bekopogtak az ajtón, Köszem azt hitte, hogy saját emberei jöttek, ezért kikiabált nekik, hogy “Megjöttetek?”. Erre azonban a janicsárok hangja helyett Köszem az eunuch Szulejmán Aga hangját hallotta meg, amitől bepánikolt és menekülni kezdett. Nem pontosan tudni, hogy hogy jutott ki lakrészéből vagy ki jutott e egyáltalán, mert a leírások nem egyeznek. Egyesek szerint lakrészén belül bújt el egy szekrényben, mások szerint megpróbált kijutni a janicsárokhoz, azonban a zárt kapun keresztül nem tudott, így végül a kapu melletti szobában bújt el.

A kivégzőosztag, amely több eunuchból (Szulejmán Aga, Hoca Reyhan Aga, Lala Hajji Ibrahim Aga és Ali Aga, valamint néhány ismeretlen eunuch) állt folytatta a keresést. Köszem egy szekrényben rejtőzött el, melyből ruhájának széle kilógott, ezzel felfedve rejtekhelyét. Amikor megtalálták, kivégzői elé pénzt dobott, ezzel próbálva lefizetni őket, ám esélye sem volt Turhan hű embereivel szemben. A legenda szerint a férfiak próbálták lefogni a validét, miközben füléből kitépték gyémánt fülbevalóit, melyeket Ahmed szultántól kapott; ruháját is megtépkedték, ahogy próbálták leszedni róla az értékes díszeket. Köszem túl a hatvanon is erősen ellenállt kivégzőinek, ám végül felülkerekedtek rajta. Egyesek szerint saját hajával, mások szerint egy függönnyel fojtották meg. Az első fojtogatási kísérlet után még magához tért, a másodikat azonban már nem élte túl.

Van azonban több olyan pont a fenti történetben, ami kétségeket ébreszt:

- Köszem problémája nem Mehmed volt, hanem a pasák, Turhan és Szulejmán Aga. Miért nem tőlük szabadult meg? Nem lett volna egyszerűbb és jogszerűbb meggyilkoltatni ezeket az embereket, mint trónfosztani az egyik gyermek szultánt egy másik gyermek javára? Természetesen megindokolhatjuk annyival a dolgot, hogy Köszem nem volt már épelméjű, így ne is keressünk logikát cselekedeteiben. Ugyanakkor felmerülhet az is, hogy talán Köszem teljesen vagy legalább részben ártatlan volt az egész eseménysorozatban. Elképzelhető, hogy nem tervezett semmit a janicsárokkal, az egész terv csak Turhan és emberei által lett kitalálva, hogy legitimizálják saját tetteiket. Ennek azonban ellent mond, hogy a janicsárok a tragikus éjszakán valóban gyülekezni készültek, az pedig nem valószínű, hogy Turhan és csapata sikerrel vezette meg a janicsárokat úgy, hogy Köszem erről ne szerzett volna tudomást. Lehetséges, hogy Köszem valóban készült egy kisebb puccsra, de az talán nem Mehmed ellen irányult. Köszemnek látnia kellett, hogy a pasák mellett Szulejmán Aga a fő felbújtó Turhan és Mehmed "rebellis" viselkedése mögött. Úgy vélem, Köszem egy kisebb puccsot tervezett, melyben megszabadult volna a neki nem tetsző eunuchoktól, szolgálóktól és ráijesztett volna Mehmedre és Turhanra. Ezzel biztosíthatta volna saját hatalmát és azt, hogy többé se Turhan se Mehmed ne kérdőjelezze őt meg.

- Miért gyilkolták meg Köszemet ilyen furcsa módon? Hiszen a jogszerű, szokásos kivégzési mód kivégző osztag által, Seyhülislami fetwával és selyemzsinórral történt. (Fontos ugyanakkor megjegyezni, hogy a dinasztia nő tagjain nem alkalmaztak korábban kivégzést, a nőket jellemzően száműzetéssel büntették.) Köszemet ezzel szemben képzetlen eunuchokkal, hamis fetwával és a saját hajával vagy egy függönnyel gyilkolták meg. Felmerül a kérdés, hogy talán Köszem kivégzése nem is volt eltervezve. Ha a kivégzés el lett volna tervezve, könnyedén tudtak volna kivégzőket szerezni selyemzsinórral és a fetwa kikérésének körülményei is egyértelműek lennének. Volt természetesen fetwa, de az időbeliséget kissé megzavarja a tény, hogy a régi Seyhülislamot ugyanakkor váltották le Turhan egyik megbízható emberére, mikor a kivégzés zajlott. Épp emiatt, és a kivégzés szokásostól eltérő brutalitása miatt, felmerülhet annak a lehetősége is, hogy talán Köszem kivégzése nem volt eredetileg eltervezve, csupán menet közben csúszott ki az irányítás Turhan kezéből és a pillanat hevében az eunuchok kivégezték Köszemet. Utólag pedig, hogy legalizálják az eseményeket gyártattak egy fetwát az új Seyhülislámmal.

- De akkor ki és miért döntött végül úgy, hogy Köszemnek meg kell halnia? Turhan nem volt jelen az események során, és mivel a gyilkosság nem volt előre eltervezve, őt kihúznám a gyanúsítottak listájáról. Természetesen az nem zárható ki, hogy Szulejmán Agával beszéltek erről az eshetőségről is. Valószínűbb azonban, hogy eredtileg csupán rá akartak ijeszteni Köszemre, megmutatni neki, hogy leleplezték, eljárt felette az idő. Véleményem szerint Turhan azt remélte, hogy Köszem beismeri vereségét és egyszerűen visszavonul a Régi Palotába. Túl kockázatos lett volna megölni egy ennyire tisztelt és szeretett validét, úgy, hogy korábban sosem végezték ki a dinasztia egyik nőtagját sem. Nem vall épelmére szánt szándékkal előrekitervelten, ilyen módon megölni Köszemet. Valószínűleg le akarták mondatni, Köszemnek azonban eddigre már nem volt vesztenivalója. Az egyetlen dolog, ami még éltette az a hatalom volt, így minden bizonnyal ellenkezett a kényszer visszavonulás gondolatától. Mikor Szulejmán Aga felismerte, hogy Köszem nem hallgat rájuk, talán félelemből úgy döntött meg kell őt ölniük. Hiszen ha a felbőszített Köszem kijutott volna a palotából Szulejmán és a többi eunuch azon nyomban fej nélkül találta volna magát. Bár nem utal rá bizonyíték, de személyes véleményem az, hogy Szulejmán talán az első perctől kezdve ezt akarta, hiszen tudta jól, hogy Köszem sosem fog visszavonulni. Akárhogyan is az eunuchok végül professzionálisnak egyáltalán nem mondható módon legyűrték az idős validét és kivégezték.

- Teljesen kizárható, hogy legális fetwa és kivégző osztag végzett Köszemmel? Sajnos ezt sem zárhatjuk ki. Az angol követ például arról számolt be, hogy kivégző osztag ölte meg Köszemet, az ifjú szultán által kért fetwa után, Mehmed szeme láttára. Igaz, hogy az angol követ nem a legjobban informáltak közé tartozott. Valószínű, hogy mindenki úgy hitte akkoriban, hogy a fetwa előre volt kiadva, csak később, a történészek kutatásai világítottak rá arra, hogy a fetwa feltehetőleg Köszem kivégzése után készült el. Azt pedig, hogy Köszemet a 10 éves Mehmed szeme láttára végezték volna ki, nem tartom valószínűnek. Turhan nagyon erősen igyekezett óvni fiát, nem valószínű, hogy kitette volna őt egy ilyen traumának. Mustafa Naima abban egyetért az angol követtel, hogy a kivégzés előre megtervezett volt, ám szerinte nem eunuchok, hanem kivégző osztag végzett a valide szultánával. Azonban akkor miért volt brutális a kivégzés? Miért nem volt selyemzsinór? Miért alkalmatlan eunuchok vitték véghez?

A gyilkosság utóhatása

Hogy megakadályozzanak bármiféle ellenállást, Turhan Hatice és emberei az éjszaka folyamán minden olyan államférfit eltávolítottak posztjáról, aki veszélyeztette volna őket. Az első ember, akit kineveztek akkor éjjel, az Ebu Said Efendi lett, az új Seyhülislam. Ő volt az, aki végül kiadta a fetwát Köszem kivégzésére (utólagosan). Ezekután Turhan megüzente az összes államférfinak és katonának, hogy azonnal menjenek audienciára, ahol hűséget fogadnak Mehmed szultánnak. A legtöbben félelemből vagy őszinte érzések által vezérelve, azonnal a szultán elé járultak, akik pedig nem, azokra az új Seyhülislám fetwat adott ki. Így vált jogszerűvé Köszem támogatóinak kivégzése is, hiszen ők sem jelentek meg a szultán előtt. A lázadó janicsárok pedig így árulóként lettek megbélyegezve és legálisan kivégezték őket. A nép szemében végül ők lettek bűnbaknak kikiáltva Köszem haláláért. Köszemet a gyilkosság után a Régi Palotába szállították, ahol előkészítették testét a temetésre. Birodalmi temetést kapott, Isztambul népe pedig önkéntesen 3 napos gyászt tartott, bezárva minden boltot és üzletet. Köszem mindig népszerű volt az emberek között, ám érdekes módon ugyanaz a nép, nem fordult Turhan ellen Köszem halála miatt, sőt, Turhan hasonlóan szeretett és tisztelt valide szultána lett, mint amilyen Köszem volt.

Mi történt a valódi bűnösökkel? Turhan és Mehmed természetesen megúszták, ugyanakkor kérdéses, hogy a gyilkosságban egyáltalán volt e részük. Igaz egy 1656-os lázadás komolyan megrengette hatalmukat, de végül nem veszítették el azt. A lázadásnak a legnagyobb oka a gyenge nagyvezírek, az újjáéledő Celali lázadás és a velenceiekkel vívott háború voltak. A körülmények miatt nem jutott elég gabona a fővárosba, a katonák nem kaptak rendesen fizetést, de az egyszerű emberek is egyre elégedetlenebbek voltak, különösen dühítette őket a szultánhoz közelállók extrém gazdagsága. Végül a janicsárok és szpáhik vezetésével a nép fellázadt 1656 március negyedikén. A lázadás során a szultánhoz közelállók közül többeket brutálisan kivégeztek, az egész fővárost feldúlták. A csőcselék Mehmed 31 közeli emberét a Kék Mecset mellett akasztotta fel egy egy fára. Köztük volt Meleki Hatun is, akit a szultán különösen szeretett. Bár korábban is rázták meg lázadások a fővárost, ehhez fogható még sosem történt. Nem csak a katonák lázadtak fel, a nép is egy emberként állt ki a katonák mellett és állt be mögéjük. Mindenki bezárta boltjait, általános sztrájk lépett érvénybe a lázadás idejére.

Szulejmán Aga már nem volt hatalmon amikor a lázadás megtörtént és talán ez tartotta helyén a fejét. Szulejmán Köszem meggyilkolása után a fő hárem eunuch lett, ám a pozíciót csupán 1652 júliusáig élvezhette. Szulejmán tovább nyújtózkodott, mint a takarója ért, olyan politikai témákba is igyekezett beleszólni, amihez semmi köze nem volt. Turhan Hatice is kezdte felismerni, hogy Szulejmán egyáltalán nem az ő oldalukon áll, hanem csak a saját magáén. Külön érdekesség, hogy az a Lala Ibrahim Aga győzte meg erről Turhant, aki maga is részt vett Köszem kivégzésében. Lala Ibrahim Aga Turhan személyes eunuchja volt és maga sosem vágyott (vagy bölcsen nem mutatta ki) ennél magasabb pozícióra. Turhan így végül 1652-ben megfosztotta pozíciójától Szulejmán Agát és száműzte Egyiptomba. A rafinált eunuch még a száműzetésben is feltalálta magát, befolyásos személlyé nőtte ki magát, aki Kairó helyi politikájának egyik főszereplője lett. 1676/7-ben halt meg.

Epilógus

Valószínűleg sosem fogjuk pontosan megtudni, hogy mi vezetett a kivégzéshez és hogyan zajlott az le. A poszttal nem is az volt a célom, hogy egy tökéletes megoldást mutassak be Hercule Poirot módjára, csupán szerettem volna rávilágítani arra, hogy az általánosan ismert és elfogadott teória, inkább megszokásból tekintendő a legáltalánosabban elfogadottnak, nem pedig alapossága miatt. Rengeteg a kérdőjel, kétes információ és helyzet a kivégzés körülményei között, ami egyértelműsíti, hogy ez az egész helyzet bonyolultabb volt annál, minthogy két nő harcot vívott a hárem feletti uralomért.

Köszem volt az a szultána, aki a legmagasabbra tört, aki sokáig lehetett a csúcson, azonban a nagy magasságból zuhant végül alá és vált az egyetlen meggyilkolt valide szultánává. Élete során több címet is kapott: Naib-i Sultanat (az Oszmán Birodalom régense), Umin al-Mu'minin (minden muszlimok anyja), Büyük Valide Sultan (nagy valide szultána), Valide-i Sehide (a mártír anya), Valide-i Maktule (a meggyilkolt anya), Valide-i Muazzama (a csodálatos anya).

Felhasznált források: M. Kocaaslan - IV. Mehmed Saltanatında Topkapı Sarayı Haremi: İktidar, Sınırlar ve Mimari; L. Peirce - The Imperial Harem; Ö. Kumrular - Kösem Sultan: iktidar, hırs, entrika; C. Finkel - Osman’s Dream: the History of the Ottoman Empire; M. P. Pedani - Relazioni inedite; N. Sakaoğlu - Bu Mülkün Kadın Sultanları; G. Börekçi - Factions and Favorites at the Courts of Sultan Ahmed I and His Immediate Predecessors; F. Davis - The Palace of Topkapi in Istanbul; Faroqhi - The Ottoman Empire and the World; C. Imber - The Ottoman Empire 1300-1650; F. Suraiya, K. Fleet - The Cambridge History of Turkey 1453-1603; F. Suraiya - The Cambridge History of Turkey, The Later Ottoman Empire, 1603–1839; Ö. Düzbakar - Charitable Women And Their Pious Foundations In The Ottoman; G. Junne - The black eunuchs of the Ottoman Empire, Networks of Power in the Court of the Sultan.

#mahpeyker kösem#Kösem sultan#kösem#kosem#Mahpeyker#valide-i muazzama#valide sultan#valide kösem sultan#Turhan Hatice Sultan#turhan hatice#turhan#Mehmed IV#süleyman aga#suleiman agha#valide-i maktule#valide-i şehide#valide-i sehide#büyük valide sultan#büyük valide#küçük valide#küçük valide sultan#naib-i sultanat#umin al-mu'minin#umin almuminin#umin al-muminin

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Early modern England maintained a deeply ambivalent outlook toward old age, whose inception was variably set anywhere from about forty onward: gérontocratie in its formal ideology, the society simultaneously displayed a "pessimistic" or even disdainful regard for a stage of life associated with "a wretched time of physical deterioration." Moreover, women in this setting experienced if anything a compounded version of such conflicted attitudes. Freed from the substantial physical hazards of parturition and often from the dependencies and demands of earlier life stages, as Amy M. Froide has argued, single women of the day were perhaps "best positioned to enjoy a positive old age," yet those who had avoid ed marriage altogether "faced derogatory epithets such as ‘old maid’ and ‘ superannuated virgin’ that made direct reference to their advanced age."

Exploring the social impact of menopause in sixteenth-century culture, Lynn Botelho likewise refocuses the emphasis on physical appearance with which women in the era especially had to reckon: "the end of regeneration probably did not signal the beginning of old age to early modern society," she observes, "but menopause did coincide with a host of culturally significant visual changes that resulted in women being labelled old at this stage." Given the unquestionable centrality of "outwardly observable signifiers of status in early modern England," Botelho concludes that "A woman became old when she looked old." This notion takes an expressly humiliating turn in the gerontophobic, antifeminist bias informing contemporary pictorial traditions that rendered figures like Helen, Cleopatra, or even Lucretia as elderly grotesques who might never have exerted the power they did over men could they have been envisioned in their decrepitude.

Keenly sensitive to such contexts, Elizabeth as head of state appreciated how the need to manage constructions of her appearance was a matter of political order. From early in her reign, she aimed to exert as much control over this critical domain as possible, an impulse that took on ever greater urgency amid the growing generational animosities that came to mark her regimes later decades. Educated in the multiform terms of Elizabeth’s public iconography, we have yet to investigate adequately the queens complex sense of her own physical body as it aged. As a result, darker evaluations of the "Mask of Youth" convention so prominent toward the end of the reign have come to overdetermine modern judgments.

As early as 1563, after all, her council had circulated a draft of a proclamation "to prohibit all manner of other persons to draw, paint, grave, or portray her majesty's personage or visage for a time until, by some perfect pattern or example, the same may be by others followed." Our readiness to read her later self-representations as governed by vanity rather than strategy in many respects invests too literally in Ben Jonson's famous sneer that "Queen Elizabeth never saw herself after she became old in a true glass." Wallace MacCaffrey’s more generous construction of the monarch's own designs puts only a slightly more positive spin on this late "posturing": while Elizabeth's (failed) effort to institute a homogenous portrait had intended clearly "to display to her subjects an unchanging, ageless countenance," he feels that such "outward manifestations are faithful reflections of a fundamental inward reality."

Whatever else we know about this "inward reality," however, we cannot doubt the profound circumspection that Elizabeth brought to all her political endeavors, the formulation of a public image not least among these. We need to resist presumptions that the elder queen was so casually seduced by her own propaganda, and to be willing to recognize her discreet capacity to embrace the advanced age that her body duly registered, less as a physical liability than as an index of the experience that empowered her reign. Always protective of the way others saw fit to represent her for supportive or derogatory purposes, she knew what her subjects expected, and within reason was willing to honor their demands. Beyond this, answerable only to herself, she knew how to project her fully embodied sense of self with a disarming authenticity.

In age as in youth, Elizabeth had the common sense to discern that, however much control a public figure exercised over her own representation, she could never fully govern her audiences response. Over the course of her long career, she grew adept at parrying the "narrative of decline" with which she increasingly had to contend. Interestingly, the first serious critical foregrounding of public discussion about her age came in response to French marriage prospects of the late 1570s, when she belatedly appeared to entertain the Duke dAlençon, over twenty years her junior, as a serious political match. However sincerely and to whatever end Elizabeth pursued the engagement, it indisputably drew national attention specifically to the subject of her years. As far back as 1570, Alençon's older brother, who would go on to take the throne as Henry III, had rejected any suggestion of courtship with such "an old creature."

A decade later, English subjects proved no less tactless in their own violent enmity to the subsequent venture. So respectful a minister as Ralph Sadler delivered a speech in which he boldly recalls how "The inequalyte of yeres" between the parties was such that "her majestie myght be his mother," where John Stubbs in his Discoverie of a Gaping Gulf lodged an even more egregious protest against the unhealthiness of matching "youth with decrepit age." But for all her public fury at such presumptuous commentary, Elizabeth in her correspondence acknowledged the age discrepancy freely. When the French king and queen mother first proposed the marriage in the summer of 1572, Elizabeth was the first to remark repeatedly on "the youngness of the years of the Duke of Alençon being compared to ours," insisting on a personal conference before anything can proceed since "nothing can make so full a satisfaction to us for our opinion nor percase in him of us in respect of the opinion he may conceive of the excess of our years above his."

She later indulges Alençon with wry self-caricatures of "the poor old woman who honors you as much (I dare say) as any young wench whom you ever will find" (CW, 251). Even apart from her most remarkable lyric reflection, the poem "When I was fair and young," which likely dates to the period following the courtship, we have sufficient evidence that Elizabeth harbored no vain illusions about her perpetual youth. Between the demise of the Alençon affair and the year of de Maisses embassy, Elizabeth faced down an almost continuous sequence of reminders of time's corrosive force. The stress of Mary Stuarts increasingly desperate plots and eventual execution in 1587 clearly took a heavy toll, provoking Essex's prediction to James VI of Scotland "that hir Majeste could not lyve above a yere or ii by reson of sum imperfección."

She of course weathered this event and the even grander trauma of the Armada that it helped precipitate the following year, only to witness the deaths of such long-standing ministers as Leicester, Walsingham, Mildmay, and Hatton ushering in what John Guy has termed the queen's "second reign." Alongside the deaths of three more trusted members of her privy council (Puckering, Hunsdon, and Knollys) in 1596, she was then forced to suffer another, more emphatic wave of commentary on her senescence as she achieved the "critical" climacteric of her sixty-third year, when an array of well-intentioned but exasperating sermons taxed her patience. Bishop Anthony Rudd, for instance, preached before her on the way Samuel “cast a right account of his yeares, who when he was become olde, made his sonnes Iudges of Israeli, because he was not able to beare the charge."

After offering for meditation an extended catalogue of the effects of bodily decline, he startlingly presumes to ventriloquize the queen herself in reflection upon her "long temporall life": "Lord, I have now put foote within the doores of that age, in the which the Almond tree flourisheth: wherein men begin to carry a Calender in their bones, the senses begin to faile, the strength to diminish, yea al the powers of the body daily to decay." Sir John Harington reported how Elizabeth, "perceiving wherto it tended, began to be troubled with" the discourse, and rebuked the preacher that "he should have kept his arithmetick to him selfe," but also reports how she later relented, protesting annoyance "Only, to show how the good bishop was deceaved" in his ageist presumption.

John Manningham's diary adds Elizabeth's sardonic but composed remark to Rudd afterwards, "M[aste]r D[octo]r, you have made me a good funeral sermon; I may dye when I will." Cultivating the "wisdom" pose she had taken up at least since the mid-1580s, when she expressed confidently to James that "we old foxes can find shifts to save ourselves by others' malice" (CW, 262), Elizabeth had by 1597 become inured to her role as elder stateswoman. She proudly wore her "years," conjuring them as leverage over her junior subjects, as we find in her 1593 assurance to the MPs that "having my head by years and experience better stayed (whatsoever any shall suppose to the contrary) than that you may easily believe I will enter into any idle expenses, now must I give you all as great thanks as ever prince gave to loving subjects" (CW, 332).

In July 1597 she reprimanded Essex's impetuosity, reminding him how "Eyes of youth have strong sights, but commonly not so deep as those of elder age" (CW, 386), Her famous rebuttal to the Polish ambassador that same month likewise sniped at his master's youth: "seeing your king is a young man and newly chosen," she answered the emissary's presumption in perfect Latin, "that doth not so perfectly know the course of managing affairs of this nature with other princes as his elders have observed with us, so perhaps others will observe which shall succeed in his place thereafter" (CW, 332-33). At the same time—and another extreme altogether—she would remain the subject of fetish and fantasy, in spite of if not because of her age.

If she could not have known Simon Forman's notorious erotic dream of her in age, presented by A. L. Rowse as evidence of the "erotic stimulus that the menfolk derived from having a Virgin Queen upon the throne," she could not have ignored the very public allegation of the executed Jesuit Thomas Portmort that his persecutor Richard Topcliffe had claimed intimate familiarity with the queen's naked features, claiming hers "the softest belly of any womankind." She was aware, in other words, of the broadly various reactions that the sight of her body might have provoked from even so amicable and compliant a character as de Maisse.”

- Christopher Martin, “The Breast and Belly of a Queen: Elizabeth After Tilbury.” in Early Modern Women

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Taylor Swift Album Ranked

We revisited each of the singer’s original studio albums and ranked them from best to worst.

FEATURESEvery Taylor Swift Album Ranked

We revisited each of the singer’s original studio albums and ranked them from best to worst.

By Slant Staff on July 6, 2021

Taylor Swift started off as a country artist at a time when the genre was both less respectful and accommodating of the voices of women than at any other point in its storied history. The singer’s first four albums barely scan as country music in a meaningful way, instead embracing her preternatural gifts for pop conventions, and her output has gotten stronger the more openly she’s embraced those skills. In the 15 years since the single “Tim McGraw” launched Swift to country stardom, she’s jettisoned the genre’s ill-fitting signifiers and overcome the limitations of her early recordings—improvements captured in her “Taylor’s Version” re-recordings of those albums as a powerful statement of artistic agency.

As Swift takes an apparent break from new music to re-record those early releases, including Fearless (Taylor’s Version) and this fall’s highly anticipated Red redux, we revisited each of her original studio albums and ranked them from best to worst.

9. Taylor Swift (2006)

Though she was praised for her songwriting right out of the gate, what Swift’s self-titled debut truly shows in hindsight is how diligently she’s worked to hone her craft over the years. Some of her trademarks—her gift for melody, her third-act POV reversals—were already present here, but there’s a sloppiness to the writing that she’s long since cleaned up. Whether that’s emphasizing the wrong syllables of words because she hadn’t quite mastered the meter of language (most notable on “Teardrops on My Guitar”) or mixing metaphors (on “Picture to Burn” and the otherwise catchy “Our Song”), there’s a lack of polish and editing on Taylor Swift

8. Fearless (2008)

Nearly every track on Swift’s sophomore effort, Fearless, builds to a massive pop hook. But while her grasp of song structure at this point in her career suggested an innate talent for how to develop a melody, Fearless also highlights Swift’s then-limited repertoire and lack of creativity in constructing her narratives of doe-eyed infatuations and first loves gone wrong. It’s admirable that she tries to incorporate more sophisticated elements into a few of the songs here, but dancing with or kissing someone in the rain is a default image that crops up with nearly the same distracting frequency as references to princesses, angels, and fairy tales. Fearless, however, just as strongly made the case that Swift had the goods for a long, rich career. The bridge to “Fifteen” includes a great, revealing line about a friend’s lost innocence (“And Abigail gave everything/She had to a boy/Who changed his mind/And we both cried”), while the playful melody of “Hey Stephen” captures the essence of what makes for indelible teen-pop.

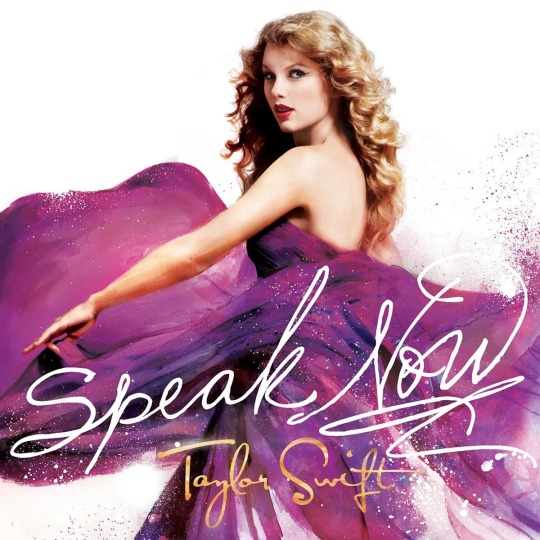

7. Speak Now (2010)

Swift’s third album, Speak Now, is problematic in precisely the same ways that its predecessors are, but there isn’t a song here that isn’t an absolute wonder of technical construction. Perhaps even more impressive is Swift’s mastery of song structure. Consider how the instrumentation drops out during the last two words of the hook in “Last Kiss,” allowing the singer’s breathy vocal delivery to bear the entirety of the song’s emotional weight, or how a simple acoustic guitar figure on “Enchanted” slowly crescendos behind each repetition of the line “I was enchanted to meet you.” Unfortunately, the greater complexity and range found in Swift’s sound and in her song constructions doesn’t necessarily translate to her songwriting. Her narrators often seem to lack insight because Swift writes with the point of view that hers is the only story to be told, which makes songs like “Dear John” and “Better Than Revenge” come across as shallow and shortsighted. And though she does vary her phrasing in ways that attempt to mask her limited voice, Swift is still noticeably off-pitch at least once on every song on the album.

6. Red (2012)

Considering that Swift’s previous material was almost always better when she tossed the ill-fitting country signifiers and focused on her uncanny gift for writing pop hooks, Red was a smart, if overdue, move for the singer. The album plays as a survey course in contemporary pop, and Swift is game to try just about anything, from the uninhibited dance-pop of standout “Starlight” to the thundering heartland rock of “Holy Ground.” The tracks that work best are those on which the production is creative and modern in ways that are in service to Swift’s songwriting. The distorted vocal effects and shifts in dynamics on “I Knew You Were Trouble” heighten the sense of frustration that drives the song, and the driving rhythm section on “Holy Ground” reflects Swift’s reminiscence of a lover who “took off faster than a green light, go.” Not all of the songs here are so keenly observed—“State of Grace” and “I Almost Do” lack the specificity that’s one of Swift’s songwriting trademarks, while the title track underwhelms with its train of pedestrian similes and metaphors—but if Red is ultimately too uneven to be a truly great pop album, its highlights were career-best work for Swift at the time.

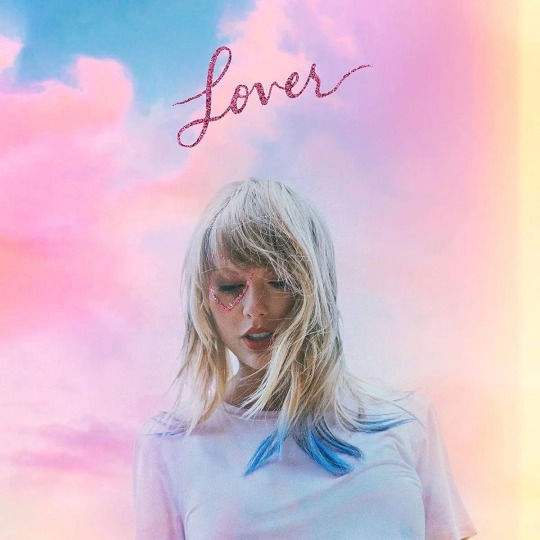

5. Lover (2019)

Swift’s seventh album, Lover, lacks a unified sonic aesthetic, ostensibly from trying to be something to everyone. The title track, whose lilting rhythm and reverb-soaked drums and vocals are reminiscent of Mazzy Star’s ‘90s gem “Fade Into You,” and the acoustic “Soon You’ll Get Better,” a tribute to Swift’s mother, hark back to the singer’s pre-pop days, while “I Think He Knows” and “False God” evoke Carly Rae Jepsen’s brand of ‘80s R&B-inflected electro-pop. When it comes to things other than boys, though, Swift has always preferred to dip her toes in rather than get soaking wet; her transformation from country teen to pop queen was, after all, a decade in the making. Less gradual was Swift’s shift from political agnostic to liberal advocate. Her once apolitical music is, on Lover, peppered with references to America’s current state of affairs, both thinly veiled (“Death by a Thousand Cuts”) and more overt (“You Need to Calm Down”). “Miss Americana & the Heartbreak Prince,” however, is her stock in trade, a richly painted narrative punctuated by cool synth washes and pep-rally chants, while “The Archer” is quintessential Swift: wistful, minimalist dream pop that displays her willingness to acknowledge and dismantle her own flaws, triggers, and neuroses.

4. Reputation (2017)