#victor vescovo

Text

since theres a lot of discussions about shipwrecks and deep sea submersibles happening right now, im just gonna quickly recommend this video which details how caladan oceanic found the samuel b roberts.

the samuel b roberts was a destroyer escort sank during the battle off samar during ww2. the wreck was found last year and is 22,621 feet/6885 metres deep which is almost 10,000 feet or 3000 metres deeper than the titanic and is currently the deepest wreck ever found.

in the video, you see a deep sea submersible (which can go down to 36,000 feet/10,973 metres) that isnt a tin can finished up with duct tape, super glue and glittery gel pens. it is piloted by an expert and they swap out pilots every day to avoid exertion or fatigue, and they have a very complex sonar system for finding wrecks. the longest they can go down is 16 hours and they keep in contact with their ship above and have to get clearance just for half an hour more.

when they find the wreck, they look around it to ensure they can identify it and map it out as well as they can, and then head back up to shore. they then hold a funeral service for those who died and leave a wreath on the ocean surface above where the wreck lays.

while im somewhat sketched out by the founder victor vescovo, the company does important work in terms of furthering our understanding of the ocean and finding wrecks which are the gravesites of those who passed. and they are not disrespectful to those whose graves lay 22,000 feet/6700 metres down on the seabed.

and what i would like to point out is how the samuel b roberts is protected against unauthorised disturbance by the sunken military craft act. you would need a permit from the naval history and heritage command (and a submarine that can withstand all the pressure) to go see it.

which, as ive said many times in the last two days, is something that the titanic should also have protection against. there should be laws in place that do not allow people to treat a mass fucking gravesite as a tourist spot.

#kai rambles#titanic#titanic wreck#titan#titan sub#caladan oceanic#oceangate#oceangate expeditions#victor vescovo#stockton rush#tourism#samuel b roberts#dark tourism#capitalist bullshit#capitalism#mass graves#tw mass graves#sunken military craft act#naval history and heritage command#sammy b#hamish harding#battle of leyte gulf#id 100% recommend watching the video#its a fascinating watch and it is so refreshing to see them actually respect those who perished with the ship#shipposting

928 notes

·

View notes

Text

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Deepest Shipwreck To Date

What is the deepest ever shipwreck discovered? Find out after the jump!

Off the coast of the Philipines, a WWII vessel, sunk by the Japanese has been found. The ship, USS Samuel B. Roberts, was a destroyer escort engaged in a 1944 WWII naval battle.

The discovery was headed by Victor Vescovo who also found the USS Johnston, which held the title of the deepest discovered wreck until now.

Developments in technology allow us to explore previously inaccessible worlds.…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

just reread this piece from a couple years ago about a different rich guy who got the itch to get into deep sea diving and not only commissioned a new type of vehicle to do[1] but also set a bunch of records for reaching the deepest ocean trenches... which is interesting in that like, a random multi-millionaire[2] can pull off this kind of stunt, repeatedly, and not die. the oceangate guy was just a particular type of rich reckless idiot who endangered the lives of his passengers to pioneer a newer, shittier vehicle than the vehicles that other rich guys already use for these things.

also notable that over the course of his "reach the bottom of five of the deepest trenches on earth" mission, a shitload of things went wrong at first—there were snags! conditions were bad! parts failed unexpectedly! but they crew he hired wasn't full of yes-men, and they tested the shit out of everything, and there were plenty of failsafes built into the submersible itself. so no one died.[3] and eventually they got so good at diving to the bottom of trenches that it became more or less routine.

[1] a vehicle that gabe newell now owns, by the way.

[2] it's not super clear how much this guy (victor vescovo) was actually worth before he spent about fifty million dollars on deep-sea shit, but someone specifically says he was "wealthy, but not paul allen wealthy," so I think it's safe to say firmly south of a billion. in a similar vein I've seen a lot of people refer to the now-ex CEO of oceangate (stockton rush) as a billionaire, but it seems like he was also "only" a multi-millionaire. the only billionaire on board the titan when it imploded was one of its passengers (two at most if you count the billionaire's son).

[3] unless you count all the marine specimens that their resident marine biologist hauled up out of the water. I don't think they respond well to non-pressurized environments.

(non-paywall link, but I actually recommend trying to read this one in an incognito tab or something instead because there's a lot of interactive-y stuff that breaks if you're not on the new yorker's site)

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh huh. Well, what's interesting is looking at the depth chart in merch and promo material, the entire second half of tpwbyt is labelled with depths that are squarely in the Hadopelagic/Hadal zone, which is for depths found I believe exclusively in oceanic trenches (>6000m), and even then less than 50 locations worldwide have been officially noted to go that deep. The final song is at depths only recorded in Challenger Deep, part of the Mariana Trench, which is actually in the Pacific Ocean and not the Atlantic but w/e, we'll ignore that for the sake of artistic liberty.

Anyways, a fun fact that's kind of interesting to mull over and I think actually meaningful, even if on an easter egg level, is that Missing Limbs, at 10924m, is simultaneously believed to be the deepest point reached by any manned deep sea vessel (The Limiting Factor, crewed by Victor Vescovo in 2019) as well as what several studies had concluded (at the point during which the album was likely written) to be the deepest observable point of Challenger Deep in its entirety. Depth accuracy is so hard to determine because of the conditions and topography of the location that the estimated numbers you find in different articles on the same subject will fluctuate by a few meters in either direction, but that number is what comes up the most frequently in the summaries and conclusions. Technically that also makes it a song at the Benthic level, which is cool and gives me song crossover ideas but that's a different post.

A large percentage of sediment's composition at that depth is the skeletal remains of plankton and similar organisms. The atmospheric pressure at that depth is roughly 600x the standard atmospheric pressure. The water constantly hovers at just above freezing temperatures. Taking Missing Limbs and putting that song in the context of the absolutely brutal conditions of that environment, the picture of Vessel having sunk all the way down to the absolute lowest point on the planet's surface in general, is really evocative and also, ow my heart! Equally brutal and heartbreaking imagery.

That zone's associated songs beginning with Alkaline is also interesting but I'm not going to look too heavily into that. I'm actually really curious about the other depth measurements now, though. I'd imagine this particular song is the one most likely to have an actual meaning compared to the others, but it's a fun exercise and a good excuse to read more about the deep sea. The choice to begin with Atlantic already near the bottom of the Mesopelagic zone especially is ??? but I haven't given that a look yet.

#sleep token#actually we have studied the hadal zone less than we have the moon and mars bc the extreme conditions found there. also v little funding.#anyways bye i'm gonna read some articles about the hadal zone now! autism activated i love the ocean so much <3#i'll come back to the others later but they'll probs be untagged unless they're very compelling

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I lied, I am making one more post about the OceanGate discourse because I am tired of the dehumanization and jokes.

I decided to look into two of the people on board that sub because I knew nothing about them and everyone keeps saying its just a bunch of rich tourists who deserved to die.

Today we are going to talk about Hamish Harding and Paul-Henri Nargeolet.

-------

Hamish Harding: What did he do during his life? Is he just some rich asshole?

-In 2017, Harding worked with Antarctic VIP tourism company, White Desert, to introduce the first regular business jet service to the Antarctic using a Gulfstream G550, landing on Wolfs Fang Runway, an ice runway. Harding also visited the South Pole several times, accompanying Buzz Aldrin in 2016 as he became the oldest person to reach the South Pole (age 86)

-In 2019, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, Harding, along with Terry Virts, led a team of aviators that took the Guinness World Record for a circumnavigation of the Earth via North and South Poles in a Gulfstream G650ER in 46 hours 40 minutes. The One More Orbit mission launched and landed at the Shuttle Landing Facility (Space Florida) at NASA Kennedy Space Center, US. Harding was the mission director and led a team of over 100.

-In 2021, Harding and Victor Vescovo dived to the deepest point of the Mariana Trench, the Challenger Deep at a depth of 36,000 feet (11,000 m), in a two-person submarine, setting the records for greatest length covered and greatest time spent at full ocean depth.

-In 2022, Harding's aviation company Action Aviation supplied a customized Boeing 747-400 aircraft to transport eight wild cheetahs from Namibia to India to launch the reintroduction of the cheetah to India project of the Indian Government and the Cheetah Conservation Fund in Namibia (CCF). Cheetahs have been extinct in India since independence in 1947. This conservation project was designated a "flagged expedition" by the Explorers Club with club members Harding and Laurie Marker, founder of the CCF, carrying the flag on the flight to India.

-------

Paul-Henri Nargeolet: What did he do during his life? Is he just some rich asshole?

-In the 1970s, he was appointed Commander of the Groupement de Plongeurs Démineurs de Cherbourg, whose mission was to find and neutralise underground mines.

-In the 1980s, he was transferred to the Underwater Intervention Group (GISMER), where he piloted intervention submarines. During this time, he travelled the world retrieving submerged French planes and helicopters, including the individuals and weapons upon them. Through this work, he found an Roman wreck, located at a depth of 70 metres. He also located a DHC-5 Buffalo that crashed in 1979 with 12 people on board, including several members of the Mauritanian government.

-Nargeolet piloted dives to the Titanic wreck site in 1987, 1993, 1994 and 1996. His 1987 expedition was the first to collect artifacts from the wreckage.

-In August 2007 RMS Titanic, Inc., owned by Premier Exhibitions, a company that organises travelling exhibitions, commissioned Nargeolet to locate RMS Carpathia, which had rescued survivors of RMS Titanic but was torpedoed in 1918.

-Nargeolet worked with RMS Titanic, Inc. to recover artifacts related to the Titanic as the Director of the Underwater Research Program. His work has included utilizing remotely operated vehicles (ROV), as well as piloting dives to the wreck site. His work has resulted in recovering nearly 6,000 artifacts over the course of 35 dives. In 2010, he was part of a mission to 3D map the wreck site and determine levels of deterioration using ROVs and autonomous underwater robots.

-In 2010, he participated in the search for the flight recorder of Air France Flight 447, which crashed the previous year while en route from Rio de Janeiro to Paris

-------

TLDR: They may be a couple of rich dudes, but they were more than that. They were actually qualified to be in such a vehicle with actual experience diving in real submarines and had reason to be there. They were not just some tourists. They did a lot more than any of you are ever going to do, but sure, lets dehumanize them and see them as just a bunch lazy rich people who deserve to die simply because they are rich.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

June 1907 Century Magazine published a letter said to be addressed to an Italian Count Victor A. Pepe, written by Victor Hugo, and translated into Italian "probably" by Hugo's secretary. The Count's daughter, Countess Rozwadowska, came into possession of the letter, believed to be unpublished, and shared it with the Century Magazine. However, I haven't been able to find out any more about Pepe or Rozwadowska.

You will probably recognize the letter in question (which I will put below the cut) as the one Hugo wrote to the publisher of the Italian translation of Les Miserables, M. Daelli of Milan. Perhaps it was first published in English in 1907 but it had definitely been published in French as early as 1890, at the end of the edition of Les Mis published by Émile Testard and I believe it was included in the original 1862/3 edition of the Italian translation, based on a google translate of this auction listing. The last mystery for me is the signature, which doesn't look to me like Victor Hugo's signature at all.

The letter was apparently quite interesting to English-speaking readers and I found several newspaper articles discussing its publication. If you know anything else about this letter please share!! I'm sure I've read something else about it...somewhere....

HAUTEVILLE-HOUSE, October 18, 1862.

You are right, sir, when you tell me that Les Misérables is written for all nations. I do not know whether it will be read by all, but I wrote it for all. It is addressed to England as well as to Spain, to Italy as well as to France, to Germany as well as to Ireland, to Republics which have slaves as well as to Empires which have serfs. Social problems overstep frontiers. The sores of the human race, those great sores which cover the globe, do not halt at the red or blue lines traced upon the map. In every place where man is ignorant and despairing, in every place where woman is sold for bread, wherever the child suffers for lack of the book which should instruct him and of the hearth which should warm him, the book of Les Misérables knocks at the door and says: "Open to me, I come for you."

At the hour of civilization through which we are now passing, and which is still so sombre, the miserable's name is Man; he is agonizing in all climes, and he is groaning in all languages.

Your Italy is no more exempt from the evil than is our France. Your admirable Italy has all miseries on the face of it. Does not banditism, that raging form of pauperism, inhabit your mountains? Few nations are more deeply eaten by that ulcer of convents which I have endeavored to fathom. In spite of your possessing Rome, Milan, Naples, Palermo, Turin, Florence, Sienna, Pisa, Mantua, Bologna, Ferrara, Genoa, Venice, a heroic history, sublime ruins, magnificent ruins, and superb cities, you are, like ourselves, poor. You are covered with marvels and vermin. Assuredly, the sun of Italy is splendid, but, alas, azure in the sky does not prevent rags on man.

Like us, you have prejudices, superstitions, tyrannies, fanaticisms, blind laws lending assistance to ignorant customs. You taste nothing of the present nor of the future without a flavor of the past being mingled with it. You have a barbarian, the monk, and a savage, the lazzarone. The social question is the same for you as for us. There are a few less deaths from hunger with you, and a few more from fever; your social hygiene is not much better than ours; shadows, which are Protestant in England, are Catholic in Italy; but, under different names, the vescovo is identical with the bishop, and it always means night, and of pretty nearly the same quality. To explain the Bible badly amounts to the same thing as to understand the Gospel badly.

Is it necessary to emphasize this? Must this melancholy parallelism be yet more completely verified? Have you not indigent persons? Glance below. Have you not parasites? Glance up. Does not that hideous balance, whose two scales, pauperism and parasitism, so mournfully preserve their mutual equilibrium, oscillate before you as it does before us? Where is your army of schoolmasters, the only army which civilization acknowledges?

Where are your free and compulsory schools? Does every one know how to read in the land of Dante and of Michael Angelo? Have you made public schools of your barracks? Have you not, like ourselves, an opulent war-budget and a paltry budget of education? Have not you also that passive obedience which is so easily converted into soldierly obedience? military establishment which pushes the regulations to the extreme of firing upon Garibaldi; that is to say, upon the living honor of Italy? Let us subject your social order to examination, let us take it where it stands and as it stands, let us view its flagrant offences, show me the woman and the child. It is by the amount of protection with which these two feeble creatures are surrounded that the degree of civilization is to be measured. Is prostitution less heartrending in Naples than in Paris? What is the amount of truth that springs from your laws, and what amount of justice springs from your tribunals? Do you chance to be so fortunate as to be ignorant of the meaning of those gloomy words: public prosecution, legal infamy, prison, the scaffold, the executioner, the death penalty? Italians, with you as with us, Beccaria is dead and Farinace is alive. And then, let us scrutinize your state reasons. Have you a government which comprehends the identity of morality and politics? You have reached the point where you grant amnesty to heroes! Something very similar has been done in France. Stay, let us pass miseries in review, let each one contribute his pile, you are as rich as we. Have you not, like ourselves, two condemnations, religious condemnation pronounced by the priest, and social condemnation decreed by the judge? Oh, great nation of Italy, thou resemblest the great nation of France! Alas! our brothers, you are, like ourselves, Miserables.

From the depths of the gloom wherein you dwell, you do not see much more distinctly than we the radiant and distant portals of Eden. Only, the priests are mistaken. These holy portals are before and not behind us.

I resume. This book, Les Misérables, is no less your mirror than ours. Certain men, certain castes, rise in revolt against this book,—I understand that. Mirrors, those revealers of the truth, are hated; that does not prevent them from being of use.

As for myself, I have written for all, with a profound love for my own country, but without being engrossed by France more than by any other nation. In proportion as I advance in life, I grow more simple, and I become more and more patriotic for humanity.

This is, moreover, the tendency of our age, and the law of radiance of the French Revolution; books must cease to be exclusively French, Italian, German, Spanish, or English, and become European, I say more, human, if they are to correspond to the enlargement of civilization.

Hence a new logic of art, and of certain requirements of composition which modify everything, even the conditions, formerly narrow, of taste and language, which must grow broader like all the rest.

In France, certain critics have reproached me, to my great delight, with having transgressed the bounds of what they call "French taste"; I should be glad if this eulogium were merited.

In short, I am doing what I can, I suffer with the same universal suffering, and I try to assuage it, I possess only the puny forces of a man, and I cry to all: "Help me!"

This, sir, is what your letter prompts me to say; I say it for you and for your country. If I have insisted so strongly, it is because of one phrase in your letter. You write:—

"There are Italians, and they are numerous, who say: 'This book, Les Misérables, is a French book. It does not concern us. Let the French read it as a history, we read it as a romance.'"—Alas! I repeat, whether we be Italians or Frenchmen, misery concerns us all. Ever since history has been written, ever since philosophy has meditated, misery has been the garment of the human race; the moment has at length arrived for tearing off that rag, and for replacing, upon the naked limbs of the Man-People, the sinister fragment of the past with the grand purple robe of the dawn.

If this letter seems to you of service in enlightening some minds and in dissipating some prejudices, you are at liberty to publish it, sir. Accept, I pray you, a renewed assurance of my very distinguished sentiments.

VICTOR HUGO.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the gravity or none of it

You're not going to get Musk in a submarine, or Bezos. You might get Zuck.

When you become a male millionaire, you get a form you have to fill in that binds to your soul, and defines you forever as either a boat millionaire, or a plane millionaire. You either get a yacht or a private plane, and whether you own the other, one defines you.

As you become a multi-millionaire, you evolve into either a Space Millionaire (Musk, Bezos, John Carmack, Branson) or a Deep Sea Millionaire (James Cameron, Gabe Newell, Victor Vescovo, Stockton Rush). Traditionally there was also the Mountain Millionaire, but up until the Space Millionaires provide access to new mountains, the shine's kind of worn off.

Space flight is a lot more safety conscious than sea exploration, partly - I suspect - because the last time sea exploration was predominantly publicly funded was the 1600s, whereas Space exploration has been a government project in the last fifty years, so it's less likely that the space billionaires will find themselves lost in a tin-can in space.

But don't give up hope! Space Billionaires are just as obsessed with out-debating physics as Deep Sea Billionaires!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Always interesting to see Pete and Blair rub shoulders with other Omega Brand ambassadors:

The event in Mykenos, Greece had an impressive guest list: Actor, producer, writer and director George Clooney; award-winning actress and James Bond star Naomie Harris; actor Jesse Williams; actor Diego Boneta; actor Paul Wesley; content creator and entrepreneur Jacob Rott; TV presenter, producer, author and wine expert Antoni Porowski; America’s Cup winners Blair Tuke and Peter Burling; rapper, singer and songwriter Ninho; world famous explorer Victor Vescovo. Swiss model/presenter Manuela Frey was also among the OMEGA guests.

Brand ambassadors Blair Tuke and Peter Burling of Emirates Team New Zealand were also present in Mykonos. The America’s Cup defenders and multiple Olympic medalists took time out of their busy schedules to travel for the occasion. The Kiwis are the founders of Live Ocean, a New Zealand charity that supports and invests in promising projects in ocean science, innovation, technology and conservation.

From https://lookcharms.com/omega-seamaster-in-the-spotlight-personality-and-interviews/

#blair tuke#peter burling#omegawatches#omega brand ambassadors#looking good boys#live ocean foundation#2023Jun28#mykonos greece#omega

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Titan Submersible Was “An Accident Waiting to Happen”

Interviews and e-mails with expedition leaders and employees reveal how OceanGate ignored desperate warnings from inside and outside the company. “It’s a lemon,” one wrote.

— By Ben Taub | July 1, 2023

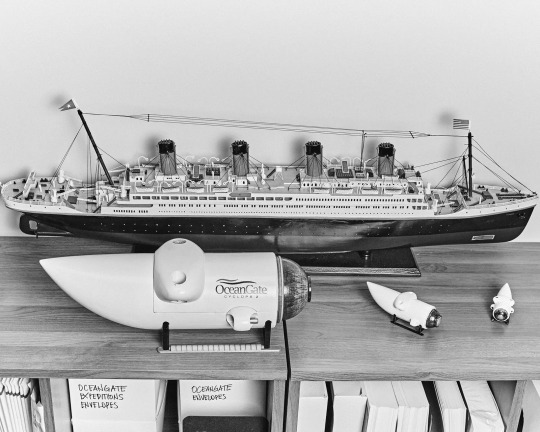

Stockton Rush, the co-founder and C.E.O. of OceanGate, inside Cyclops I, a submersible, on July 19, 2017. Photographs by Balazs Gardi

The primary task of a submersible is to not implode. The second is to reach the surface, even if the pilot is unconscious, with oxygen to spare. The third is for the occupants to be able to open the hatch once they surface. The fourth is for the submersible to be easy to find, through redundant tracking and communications systems, in case rescue is required. Only the fifth task is what is ordinarily thought of as the primary one: to transport people into the dark, hostile deep.

At dawn four summers ago, the French submariner and Titanic expert Paul-Henri Nargeolet stood on the bow of an expedition vessel in the North Atlantic. The air was cool and thick with fog, the sea placid, the engine switched off, and the Titanic was some thirty-eight hundred metres below. The crew had gathered for a solemn ceremony, to pay tribute to the more than fifteen hundred people who had died in the most famous maritime disaster more than a hundred years ago. Rob McCallum, the expedition leader, gave a short speech, then handed a wreath to Nargeolet, the oldest man on the ship. As is tradition, the youngest—McCallum’s nephew—was summoned to place his hand on the wreath, and he and Nargeolet let it fall into the sea.

Inside a hangar on the ship’s stern sat a submersible known as the Limiting Factor. In the previous year, McCallum, Nargeolet, and others had taken it around the Earth, as part of the Five Deeps Expedition, a journey to the deepest point in each ocean. The team had mapped unexplored trenches and collected scientific samples, and the Limiting Factor’s chief pilot, Victor Vescovo—a Texan hedge-fund manager who had financed the entire operation—had set numerous diving records. But, to another member of the expedition team, Patrick Lahey, the C.E.O. of Triton Submarines (which had designed and built the submersible), one record meant more than the rest: the marine-classification society DNV had certified the Limiting Factor’s “maximum permissible diving depth” as “unlimited.” That process was far from theoretical; a DNV inspection engineer was involved in every stage of the submersible’s creation, from design to sea trials and diving. He even sat in the passenger seat as Lahey piloted the Limiting Factor to the deepest point on Earth.

After the wreath sank from view, Vescovo climbed down the submersible hatch, and the dive began. For some members of the crew, the site of the wreck was familiar. McCallum, who co-founded a company called eyos Expeditions, had transported tourists to the Titanic in the two-thousands, using two Soviet submarines that had been rated to six thousand metres. Another crew member was a Titanic obsessive—his endless talk of davits and well decks still rattles in my head. But it was Paul-Henri Nargeolet whose life was most entwined with the Titanic. He had dived it more than thirty times, beginning shortly after its discovery, in 1985, and now served as the underwater-research director for the organization that owns salvaging rights to the wreck.

Nargeolet had also spent the past year as Vescovo’s safety manager. “When I set out on the Five Deeps project, I told Patrick Lahey, ‘Look, I don’t know submarine technology—I need someone who works for me to independently validate whatever design you come up with, and its construction and operation,’ ” Vescovo recalled, this week. “He recommended P. H. Nargeolet, whom he had known for decades.” Nargeolet, whose wife had recently died, was a former French naval commander—an underwater-explosives expert who had spent much of his life at sea. “He had a sterling reputation, the perfect résumé,” Vescovo said. “And he was French. And I love the French.”

When Vescovo reached the silty bottom at the Titanic site, he recalled his private preparations with Nargeolet. “He had very good knowledge of the currents and the wreck,” Vescovo told me. “He briefed me on very specific tactical things: ‘Stay away from this place on the stern’; ‘Don’t go here’; ‘Try and maintain this distance at this part of the wreck.’ ” Vescovo surfaced about seven hours later, exhausted and rattled from the debris that he had encountered at the ship’s ruins, which risk entangling submersibles that approach too close. But the Limiting Factor was completely fine. According to its certification from DNV, a “deep dive,” for insurance and inspection purposes, was anything below four thousand metres. A journey to the Titanic, thirty-eight hundred metres down, didn’t even count.

Nargeolet remained obsessed with the Titanic, and, before long, he was invited to return. “To P. H., the Titanic was Ulysses’ sirens—he could not resist it,” Vescovo told me. A couple of weeks ago, Nargeolet climbed into a radically different submersible, owned by a company called OceanGate, which had spent years marketing to the general public that, for a fee of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, it would bring people to the most famous shipwreck on Earth. “People are so enthralled with Titanic,” OceanGate’s founder, Stockton Rush, told a BBC documentary crew last year. “I read an article that said there are three words in the English language that are known throughout the planet. And that’s ‘Coca-Cola,’ ‘God,’ and ‘Titanic.’ ”

Nargeolet served as a guide to the wreck, Rush as the pilot. The other three occupants were tourists, including a father and son. But, before they reached the bottom, the submersible vanished, triggering an international search-and-rescue operation, with an accompanying media frenzy centered on counting down the hours until oxygen would run out.

McCallum, who was leading an expedition in Papua New Guinea at the time, knew the outcome almost instantly. “The report that I got immediately after the event—long before they were overdue—was that the sub was approaching thirty-five hundred metres,” he told me, while the oxygen clock was still ticking. “It dropped weights”—meaning that the team had aborted the dive—“then it lost comms, and lost tracking, and an implosion was heard.”

An investigation by the U.S. Coast Guard is ongoing; some debris from the wreckage has been salvaged, but the implosion was so violent and comprehensive that the precise cause of the disaster may never be known.

Until June 18th, a manned deep-ocean submersible had never imploded. But, to McCallum, Lahey, and other experts, the OceanGate disaster did not come as a surprise—they had been warning of the submersible’s design flaws for more than five years, filing complaints to the U.S. government and to OceanGate itself, and pleading with Rush to abandon his aspirations. As they mourned Nargeolet and the other passengers, they decided to reveal OceanGate’s history of knowingly shoddy design and construction. “You can’t cut corners in the deep,” McCallum had told Rush. “It’s not about being a disruptor. It’s about the laws of physics.”

The submersible Antipodes at the OceanGate headquarters, in Everett, Washington, on July 19, 2017.

Stockton Rush was named for two of his ancestors who signed the Declaration of Independence: Richard Stockton and Benjamin Rush. His maternal grandfather was an oil-and-shipping tycoon. As a teen-ager, Rush became an accomplished commercial jet pilot, and he studied aerospace engineering at Princeton, where he graduated in 1984.

Rush wanted to become a fighter pilot. But his eyesight wasn’t perfect, and so he went to business school instead. Years later, he expressed a desire to travel to space, and he reportedly dreamed of becoming the first human to set foot on Mars. In 2004, Rush travelled to the Mojave Desert, where he watched the launch of the first privately funded aircraft to brush against the edge of space. The only occupant was the test pilot; nevertheless, as Rush used to tell it, Richard Branson stood on the wing and announced that a new era of space tourism had arrived. At that point, Rush “abruptly lost interest,” according to a profile in Smithsonian magazine. “I didn’t want to go up into space as a tourist,” he said. “I wanted to be Captain Kirk on the Enterprise. I wanted to explore.”

Rush had grown up scuba diving in Tahiti, the Cayman Islands, and the Red Sea. In his mid-forties, he tinkered with a kit for a single-person mini-submersible, and piloted it around at shallow depths near Seattle, where he lived. A few years later, in 2009, he co-founded OceanGate, with a dream to bring tourists to the ocean world. “I had come across this business anomaly I couldn’t explain,” he recalled. “If three-quarters of the planet is water, how come you can’t access it?”

OceanGate’s first submersible wasn’t made by the company itself; it was built in 1973, and Lahey later piloted it in the North Sea, while working in the oil-and-gas industry. In the nineties, he helped refit it into a tourist submersible, and in 2009, after it had been sold a few times, and renamed Antipodes, OceanGate bought it. “I didn’t have any direct interaction with them at the time,” Lahey recalled. “Stockton was one of these people that was buying these older subs and trying to repurpose them.”

In 2015, OceanGate announced that it had built its first submersible, in collaboration with the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory. In fact, it was mostly a cosmetic and electrical refit; Lahey and his partners had built the underlying vessel, called Lula, for a Portuguese marine research nonprofit almost two decades before. It had a pressure hull that was the shape of a capsule pill and made of steel, with a large acrylic viewport on one end. It was designed to go no deeper than five hundred metres—a comfortable cruising depth for military submarines. OceanGate now called it Cyclops I.

Most submersibles have duplicate control systems, running on separate batteries—that way, if one system fails, the other still works. But, during the refit, engineers at the University of Washington rigged the Cyclops I to run from a single PlayStation 3 controller. “Stockton is very interested in being able to quickly train pilots,” Dave Dyer, a principal engineer, said, in a video published by his laboratory. Another engineer referred to it as “a combination steering wheel and gas pedal.”

Around that time, Rush set his sights on the Titanic. OceanGate would have to design a new submersible. But Rush decided to keep most of the design elements of Cyclops I. Suddenly, the University of Washington was no longer involved in the project, although OceanGate’s contract with the Applied Physics Laboratory was less than one-fifth complete; it is unclear what Dyer, who did not respond to an interview request, thought of Rush’s plan to essentially reconstruct a craft that was designed for five hundred metres of pressure to withstand eight times that much. As the company planned Cyclops II, Rush reached out to McCallum for help.

“He wanted me to run his Titanic operation for him,” McCallum recalled. “At the time, I was the only person he knew who had run commercial expedition trips to Titanic. Stockton’s plan was to go a step further and build a vehicle specifically for this multi-passenger expedition.” McCallum gave him some advice on marketing and logistics, and eventually visited the workshop, outside Seattle, where he examined the Cyclops I. He was disturbed by what he saw. “Everyone was drinking Kool-Aid and saying how cool they were with a Sony PlayStation,” he told me. “And I said at the time, ‘Does Sony know that it’s been used for this application? Because, you know, this is not what it was designed for.’ And now you have the hand controller talking to a Wi-Fi unit, which is talking to a black box, which is talking to the sub’s thrusters. There were multiple points of failure.” The system ran on Bluetooth, according to Rush. But, McCallum continued, “every sub in the world has hardwired controls for a reason—that if the signal drops out, you’re not fucked.”

One day, McCallum climbed into the Cyclops for a test dive at a marina. There, he met the chief pilot, David Lochridge, a Scotsman who had spent three decades as a submersible pilot and an engineer—first in the Royal Navy, then as a private contractor. Lochridge had worked all over the world: on offshore wind farms in the North Sea; on subsea-cables installations in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans; on manned submarine trials with the Swedish Navy; on submarine-rescue operations for the navies of Britain and Singapore. But, during the harbor trial, the Cyclops got stuck in shallow water. “It was hilarious, because there were four very experienced operators in the sub, stuck at twenty or twenty-five feet, and we had to sit there for a few hours while they worked it out,” McCallum recalled. He liked and trusted Lochridge. But, of the sub, he said, “This thing is a mutt.”

Rush eventually decided that he would not attempt to have the Titanic-bound vehicle classed by a marine-certification agency such as DNV. He had no interest in welcoming into the project an external evaluator who would, as he saw it, “need to first be educated before being qualified to ‘validate’ any innovations.”

That marked the end of McCallum’s desire to be associated with the project. “The minute that I found out that he was not going to class the vehicle, that’s when I said, ‘I’m sorry, I just can’t be involved,’ ” he told me. “I couldn’t tell him anything about the Five Deeps project at that time. But I was able to say, ‘Look, I am involved with other projects that are building classed subs’—of course, I was talking about the Limiting Factor—‘and I can tell you that the class society has been nothing but supportive. They are actually part of our innovation process. We’re using the brainpower of their engineers to feed into our design.

“Stockton didn’t like that,” McCallum continued. “He didn’t like to be told that he was on the fringe.” As word got out that Rush planned to take tourists to the Titanic, McCallum recalled, “people would ring me, and say, ‘We’ve always wanted to go to Titanic. What do you think?’ And I would tell them, ‘Never get in an unclassed sub. I wouldn’t do it, and you shouldn’t, either.’ ”

In early 2018, McCallum heard that Lochridge had left OceanGate. “I’d be keen to pick your brain if you have a few moments,” McCallum e-mailed him. “I’m keen to get a handle on exactly how bad things are. I do get reports, but I don’t know if they are accurate.” Whatever his differences with Rush, McCallum wanted the venture to succeed; the submersible industry is small, and a single disaster could destroy it. But the only way forward without a catastrophic operational failure—which he had been told was “certain,” he wrote—was for OceanGate to redesign the submersible in coördination with a classification society. “Stockton must be gutted,” McCallum told Lochridge, of his departure. “You were the star player . . . . . and the only one that gave me a hint of confidence.”

“I think you are going to [be] even more taken aback when I tell you what’s happening,” Lochridge replied. He added that he was afraid of retaliation from Rush—“We both know he has influence and money”—but would share his assessment with McCallum, in private: “That sub is Not safe to dive.”

“Do you think the sub could be made safe to dive, or is it a complete lemon?” McCallum replied. “You will get a lot of support from people in the industry . . . . everyone is watching and waiting and quietly shitting their pants.”

“It’s a lemon.”

“Oh dear,” McCallum replied. “Oh dear, oh dear.”

David Lochridge, OceanGate’s former director of marine operations, pilots Cyclops I during a test dive in Everett, on July 19, 2017.

Lochridge had been hired by OceanGate in May, 2015, as its director of marine operations and chief submersible pilot. The company moved him and his family to Washington, and helped him apply for a green card. But, before long, he was clashing with Rush and Tony Nissen, the company’s director of engineering, on matters of design and safety.

Every aspect of submersible design and construction is a trade-off between strength and weight. In order for the craft to remain suspended underwater, without rising or falling, the buoyancy of each component must be offset against the others. Most deep-ocean submersibles use spherical titanium hulls and are counterbalanced in water by syntactic foam, a buoyant material made up of millions of hollow glass balls, which is attached to the external frame. But this adds bulk to the submersible. And the weight of titanium limits the practical size of the pressure hull, so that it can accommodate no more than two or three people. Spheres are “the best geometry for pressure, but not for occupation,” as Rush put it.

The Cyclops II needed to fit as many passengers as possible. “You don’t do the coolest thing you’re ever going to do in your life by yourself,” Rush told an audience at the GeekWire Summit last fall. “You take your wife, your son, your daughter, your best friend. You’ve got to have four people” besides the pilot. Rush planned to have room for a Titanic guide and three passengers. The Cyclops II could fit that many occupants only if it had a cylindrical midsection. But the size dictated the choice of materials. The steel hull of Cyclops I was too thin for Titanic depths—but a thicker steel hull would add too much weight. In December, 2016, OceanGate announced that it had started construction on Cyclops II, and that its cylindrical midsection would be made of carbon fibre. The idea, Rush explained in interviews, was that carbon fibre was a strong material that was significantly lighter than traditional metals. “Carbon fibre is three times better than titanium on strength-to-buoyancy,” he said.

A month later, OceanGate hired a company called Spencer Composites to build the carbon-fibre hull. “They basically said, ‘This is the pressure we have to meet, this is the factor of safety, this is the basic envelope. Go design and build it,’ ” the founder, Brian Spencer, told CompositesWorld, in the spring of 2017. He was given a deadline of six weeks.

Toward the end of that year, Lochridge became increasingly concerned. OceanGate would soon begin manned sea trials for Cyclops II in the Bahamas, and he believed that there was a chance that they would result in catastrophe. The consequences for Lochridge could extend beyond OceanGate’s business and the trauma of losing colleagues; as director of marine operations, Lochridge had a contract specifying that he was ultimately responsible for “ensuring the safety of all crew and clients.”

On the workshop floor, he raised questions about potential flaws in the design and build processes. But his concerns were dismissed. OceanGate’s position was that such matters were outside the scope of his responsibilities; he was “not hired to provide engineering services, or to design or develop Cyclops II,” the company later said, in a court filing. Nevertheless, before the handover of the submersible to the operations team, Rush directed Lochridge to carry out an inspection, because his job description also required him to sign off on the submersible’s readiness for deployment.

On January 18, 2018, Lochridge studied each major component, and found several critical aspects to be defective or unproven. He drafted a detailed report, which has not previously been made public, and attached photographs of the elements of greatest concern. Glue was coming away from the seams of ballast bags, and mounting bolts threatened to rupture them; both sealing faces had errant plunge holes and O-ring grooves that deviated from standard design parameters. The exostructure and electrical pods used different metals, which could result in galvanic corrosion when exposed to seawater. The thruster cables posed “snagging hazards”; the iridium satellite beacon, to transmit the submersible’s position after surfacing, was attached with zip ties. The flooring was highly flammable; the interior vinyl wrapping emitted “highly toxic gasses upon ignition.”

To assess the carbon-fibre hull, Lochridge examined a small cross-section of material. He found that it had “very visible signs of delamination and porosity”—it seemed possible that, after repeated dives, it would come apart. He shone a light at the sample from behind, and photographed beams streaming through splits in the midsection in a disturbing, irregular pattern. The only safe way to dive, Lochridge concluded, was to first carry out a full scan of the hull.

The next day, Lochridge sent his report to Rush, Nissen, and other members of the OceanGate leadership. “Verbal communication of the key items I have addressed in my attached document have been dismissed on several occasions, so I feel now I must make this report so there is an official record in place,” he wrote. “Until suitable corrective actions are in place and closed out, Cyclops 2 (Titan) should not be manned during any of the upcoming trials.”

Rush was furious; he called a meeting that afternoon, and recorded it on his phone. For the next two hours, the OceanGate leadership insisted that no hull testing was necessary—an acoustic monitoring system, to detect fraying fibres, would serve in its place. According to the company, the system would alert the pilot to the possibility of catastrophic failure “with enough time to arrest the descent and safely return to surface.” But, in a court filing, Lochridge’s lawyer wrote, “this type of acoustic analysis would only show when a component is about to fail—often milliseconds before an implosion—and would not detect any existing flaws prior to putting pressure onto the hull.” A former senior employee who was present at the meeting told me, “We didn’t even have a baseline. We didn’t know what it would sound like if something went wrong.”

OceanGate’s lawyer wrote, “The parties found themselves at an impasse—Mr. Lochridge was not, and specifically stated that he could not be made comfortable with OceanGate’s testing protocol, while Mr. Rush was unwilling to change the company’s plans.” The meeting ended in Lochridge’s firing.

Soon afterward, Rush asked OceanGate’s director of finance and administration whether she’d like to take over as chief submersible pilot. “It freaked me out that he would want me to be head pilot, since my background is in accounting,” she told me. She added that several of the engineers were in their late teens and early twenties, and were at one point being paid fifteen dollars an hour. Without Lochridge around, “I could not work for Stockton,” she said. “I did not trust him.” As soon as she was able to line up a new job, she quit.

“I would consider myself pretty ballsy when it comes to doing things that are dangerous, but that sub is an accident waiting to happen,” Lochridge wrote to McCallum, two weeks later. “There’s no way on earth you could have paid me to dive the thing.” Of Rush, he added, “I don’t want to be seen as a Tattle tale but I’m so worried he kills himself and others in the quest to boost his ego.”

McCallum forwarded the exchange to Patrick Lahey, the C.E.O. of Triton Submarines, whose response was emphatic: if Lochridge “genuinely believes this submersible poses a threat to the occupants,” then he had a moral obligation to inform the authorities. “To remain quiet makes him complicit,” Lahey wrote. “I know that may sound ominous but it is true. History is full of horrific examples of accidents and tragedies that were a direct result of people’s silence.”

OceanGate claimed that Cyclops II had “the first pressure vessel of its kind in the world.” But there’s a reason that Triton and other manufacturers don’t use carbon fibre in their hulls. Under compression, “it’s a capricious fucking material, which is the last fucking thing you want to associate with a pressure boundary,” Lahey told me.

“With titanium, there’s a purpose to a pressure test that goes beyond just seeing whether it will survive,” John Ramsay, the designer of the Limiting Factor, explained. The metal gradually strengthens under repeated exposure to incredible stresses. With carbon fibre, however, pressure testing slowly breaks the hull, fibre by tiny fibre. “If you’re repeatedly nearing the threshold of the material, then there’s just no way of knowing how many cycles it will survive,” he said.

“It doesn’t get more sensational than dead people in a sub on the way to Titanic,” Lahey’s business partner, the co-founder of Triton Submarines, wrote to his team, on March 1, 2018. McCallum tried to reason with Rush directly. “You are wanting to use a prototype un-classed technology in a very hostile place,” he e-mailed. “As much as I appreciate entrepreneurship and innovation, you are potentially putting an entire industry at risk.”

Rush replied four days later, saying that he had “grown tired of industry players who try to use a safety argument to stop innovation and new entrants from entering their small existing market.” He understood that his approach “flies in the face of the submersible orthodoxy, but that is the nature of innovation,” he wrote. “We have heard the baseless cries of ‘you are going to kill someone’ way too often. I take this as a serious personal insult.”

In response, McCallum listed a number of specific concerns, from his “humble perch” as an expedition leader. “In your race to Titanic you are mirroring that famous catch cry ‘she is unsinkable,’ ” McCallum wrote. The correspondence ended soon afterward; Rush asked McCallum to work for him—then threatened him with a lawsuit, in an effort to silence him, when he declined.

By now, McCallum had introduced Lochridge to Lahey. Lahey wrote him, “If Ocean Gate is unwilling to consider or investigate your concerns with you directly perhaps some other means of getting them to pay attention is required.”

Lochridge replied that he had already contacted the United States Department of Labor, alleging to its Occupational Safety and Health Administration that he had been terminated in retaliation for raising safety concerns. He also sent the osha investigator Paul McDevitt a copy of his Cyclops II inspection report, hoping that the government might take actions that would “prevent the potential for harm to life.”

A few weeks later, McDevitt contacted OceanGate, noting that he was looking into Lochridge’s firing as a whistle-blower-protection matter. OceanGate’s lawyer Thomas Gilman soon issued Lochridge a court summons: he had ten days to withdraw his osha claim and pay OceanGate almost ten thousand dollars in legal expenses. Otherwise, Gilman wrote, OceanGate would sue him, take measures to destroy his professional reputation, and accuse him of immigration fraud. Gilman also reported to osha that Lochridge had orchestrated his own firing because he “wanted to leave his job and maintain his ability to collect unemployment benefits.” (McDevitt, of osha, notified the Coast Guard of Lochridge’s complaint. There is no evidence that the Coast Guard ever followed up.)

Lochridge received the summons while he was at his father’s funeral. He and his wife hired a lawyer, but it quickly became clear that “he didn’t have the money to fight this guy,” Lahey told me. (Lochridge declined to be interviewed.) Lahey covered the rest of the expenses, but, after more than half a year of legal wrangling, and threats of deportation, Lochridge withdrew his whistle-blower claim with osha so that he could go on with his life. Lahey was crestfallen. “He didn’t consult me about that decision,” Lahey recalled. “It’s not that he had to—it was his fight, not mine. But I was underwriting the cost of it, because I believed in the idea that this inspection report, which he wouldn’t share with anybody, needed to see the light of day.”

Stockton Rush in front of Cyclops I, on July 19, 2017.

A few weeks after Lochridge was fired, OceanGate announced that it was testing its new submersible in the marina of Everett, Washington, and would soon begin shallow-water trials in Puget Sound. To preëmpt any concerns about the carbon-fibre hull, the company touted the acoustic monitoring system, which was later patented in Rush’s name. “Safety is our number one priority,” Rush said, in an OceanGate press release. “We believe real-time health monitoring should be standard safety equipment on all manned-submersibles.”

“He’s spinning the fact that his sub requires a hull warning system into something positive,” Jarl Stromer, Triton’s regulatory and class-compliance manager, reported to Lahey. “He’s making it sound like the Cyclops is more advanced because it has this system when the opposite is true: The submersible is so experimental, and the factor of safety completely unknown, that it requires a system to warn the pilot of impending collapse.”

Like Lochridge, Triton’s outside counsel, Brad Patrick, considered the risk to life to be so evident that the government should get involved. He drafted a letter to McDevitt, the osha investigator, urging the Department of Labor to take “immediate and decisive action to stop OceanGate” from taking passengers to the Titanic “before people die. It is that simple.” He went on, “At the bottom of all of this is the inevitable tension betwixt greed and safety.”

But Patrick’s letter was never sent. Other people at Triton worried that the Department of Labor might perceive the letter as an attack on a business rival. By now, OceanGate had renamed Cyclops II “Titan,” apparently to honor the Titanic. “I cannot tell you how much I fucking hated it when he changed the goddam name to Titan,” Lahey told me. “That was uncomfortably close to our name.”

“Stockton strategically structured everything to be out of U.S. jurisdiction” for its Titanic pursuits, the former senior OceanGate employee told me. “It was deliberate.” In a legal filing, the company reported that the submersible was “being developed and assembled in Washington, but will be owned by a Bahamian entity, will be registered in the Bahamas and will operate exclusively outside the territorial waters of the United States.” Although it is illegal to transport passengers in an unclassed, experimental submersible, “under U.S. regulations, you can kill crew,” McCallum told me. “You do get in a little bit of trouble, in the eyes of the law. But, if you kill a passenger, you’re in big trouble. And so everyone was classified as a ‘mission specialist.’ There were no passengers—the word ‘passenger’ was never used.” No one bought tickets; they contributed an amount of money set by Rush to one of OceanGate’s entities, to fund their own missions.

“It is truly hard to imagine the discernment it took for Stockton to string together each of the links in the chain,” Patrick noted. “ ‘How do I avoid liability in Washington State? How do I avoid liability with an offshore corporate structure? How do I keep the U.S. Coast Guard from breathing down my neck?’ ”

But OceanGate had a retired Coast Guard rear admiral, John Lockwood, on its board of directors. “His experiences at the highest levels of the Coast Guard and in international maritime affairs will allow OceanGate to refine our client offerings,” Rush announced with his appointment, in 2013. Lockwood said that he hoped “to help bring operational and regulatory expertise” to OceanGate’s affairs. (Lockwood did not respond to a request for comment.) Still, Rush failed to win over the submersible industry. When he asked Don Walsh, a renowned oceanographer who reached the deepest point in the ocean, in 1960, to consult on the Titanic venture, Walsh replied, “I am concerned that my affiliation with your program at this late date would appear to be nothing more than an endorsement of what you are already doing.”

That spring, more than three dozen industry experts sent a letter to OceanGate, expressing their “unanimous concern” about its upcoming Titanic expedition—for which it had already sold places. Among the signers were Lahey, McCallum, Walsh, and a Coast Guard senior inspector. “OceanGate’s anticipated dive schedule in the spring of 2018 meant that they were going to take people down, and we had a great deal of concern about them surviving that trip,” Patrick told me. But sea trials were a disaster, owing to problems with the launch-and-recovery system, and OceanGate scuttled its Titanic operations for that year. Lochridge broke the news to Lahey. “Lives have been saved for a short while anyway,” he wrote.

OceanGate kept selling tickets, but did not dive to the Titanic for the next three years. It appears that the company spent this period testing materials, and that it built several iterations of the carbon-fibre hull. But it is difficult to know what tests were done, exactly, and how many hulls were made, and by whom, because Rush’s public statements are deeply unreliable. He claimed at various points to have design and testing partnerships with Boeing and nasa, and that at least one iteration of the hull would be built at the Marshall Space Flight Center, in Huntsville, Alabama. But none of those things were true. Meanwhile, soon after Lochridge’s departure, a college newspaper quoted a recent graduate as saying that he and his classmates had started working on the Titan’s electrical systems as interns, while they were still in school. “The whole electrical system,” he said. “That was our design, we implemented it, and it works.”

By the time that OceanGate finally began diving to the Titanic, in 2021, it had refined its pitch to its “mission specialists.” The days of insinuating that Titan was safe had ended. Now Rush portrayed the submersible as existing at the very fringe of what was physically possible. Clients signed waivers and were informed that the submersible was experimental and unclassed. But the framing was that this was how pioneering exploration is done.

“We were all told—intimately informed—that this was a dangerous mission that could result in death,” an OceanGate “mission specialist” told Fox News last week. “We were versed in how the sub operated. We were versed in various protocols. But there’s a limit . . . it’s not a safe operation, inherently. And that’s part of research and development and exploration.” He went on, “If the Wright brothers had crashed on their first flight, they would have still left the bonds of Earth.” Another “mission specialist” wrote in a blog post that, a month before the implosion, Rush had confessed that he’d “gotten the carbon fiber used to make the Titan at a big discount from Boeing because it was past its shelf-life for use in airplanes.”

“Carbon fibre makes noise,” Rush told David Pogue, a CBS News correspondent, last summer, during one of the Titanic expeditions. “It crackles. The first time you pressurize it, if you think about it—of those million fibres, a couple of ’em are sorta weak. They shouldn’t have made the team.” He spoke of signs of hull breakage as if it were perfectly routine. “The first time we took it to full pressure, it made a bunch of noise. The second time, it made very little noise.”

Fibres do not regenerate between dives. Nevertheless, Rush seemed unconcerned. “It’s a huge amount of pressure from the point where we’d say, ‘Oh, the hull’s not happy,’ to when it implodes,” he noted. “You just have to stop your descent.”

It’s not clear that Rush could always stop his descent. Once, as he piloted passengers to the wreck, a malfunction prevented Rush from dropping weights. Passengers calmly discussed sleeping on the bottom of the ocean, thirty-eight hundred metres down; after twenty-four hours, a drop-weight mechanism would dissolve in the seawater, allowing the submersible to surface. Eventually, Rush managed to release the weights manually, using a hydraulic pump. “This is why you want your pilot to be an engineer,” a passenger said, smiling, as another “mission specialist” filmed her.

Last year, a BBC documentary crew joined the expedition. Rush stayed on the surface vessel while Scott Griffith, OceanGate’s director of logistics and quality assurance, piloted a scientist and three other passengers down. (Griffith did not respond to a request for comment.) During the launch, a diver in the water noticed and reported to the surface vessel that something with a thruster seemed off. Nevertheless, the mission continued.

More than two hours passed; after Titan touched down in the silt, Griffith fired the thrusters and realized something was wrong.“I don’t know what’s going on,” he said. As he fiddled with the PlayStation controller, a passenger looked out the viewport.

“Am I spinning?” Griffith asked.

“Yes.”

“I am?”

“Looks like it,” another passenger said.

“Oh, my God,” Griffith muttered. One of the thrusters had been installed in the wrong direction. “The only thing I can do is a three-sixty,” he said.

They were in the debris field, three hundred metres from the intact part of the wreck. One of the clients said that she had delayed buying a car, getting married, and having kids, all “because I wanted to go to Titanic,” but they couldn’t make their way over to its bow. Griffith relayed the situation to the ship. Rush’s solution was to “remap the PS3 controller.”

Rush couldn’t remember where the buttons were, and it seems as though there was no spare controller on the ship. Someone loaded an image of a PlayStation 3 controller from the Internet, and Rush worked out a new button routine. “Yeah—left and right might be forward and back. Huh. I don’t know,” he said. “It might work.”

“Right is forward,” Griffith read off his screen, two and a half miles below. “Uh—I’m going to have to write this down.”

“Right is forward,” Rush said. “Great! Live with it.”

Shipwrecks are notoriously difficult and dangerous to dive. Rusted cables drape the Titanic, moving with the currents; a broken crow’s nest dangles over the deck. Griffith piloted the submersible over to the wreck, and passengers within feet of it, while teaching himself in real time to operate a Bluetooth controller whose buttons suddenly had different functions than those for which he had trained.

Various models of Cyclops II are exhibited alongside a model of the Titanic, at the OceanGate headquarters, on July 19, 2017.

“If you’re not breaking things, you’re not innovating,” Rush said, at the GeekWire Summit last fall. “If you’re operating within a known environment, as most submersible manufacturers do—they don’t break things. To me, the more stuff you’ve broken, the more innovative you’ve been.”

The Titan’s viewport was made of acrylic and seven inches thick. “That’s another thing where I broke the rules,” Rush said to Pogue, the CBS News journalist. He went on to refer to a “very well-known” acrylic expert, Jerry D. Stachiw, who wrote an eleven-hundred-page manual called “Handbook of Acrylics for Submersibles, Hyperbaric Chambers, and Aquaria.” “It has safety factors that—they were so high, he didn’t call ’em safety factors. He called ’em conversion factors,” Rush said. “According to the rules,” he added, his viewport was “not allowed.”

It seemed as if Rush believed that acrylic’s transparent quality would give him ample warning before failure. “You can see every surface,” he said. “And if you’ve overstressed it, or you’ve even come close, it starts to get this crazing effect.”

“And if that happened underwater . . .”

“You just stop and go to the surface.”

“You would have time to get back up?” Pogue asked.

“Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. It’s way more warning than you need.”

John Ramsay, who has designed several acrylic-hulled submersibles, was less sure. “You’ll probably never be able to find out the source of failure” of the Titan, he told me, in a recent phone call from his cottage in southwest England. But it seems as though Rush did not understand how acrylic limits are calculated. “Where Stockton is talking about those things called conversion factors . . .”

Ramsay grabbed a copy of Stachiw’s acrylic handbook from his spare bedroom. When Stachiw’s team was doing its tests, “they would pressurize it really fast, the acrylic would implode, and then they would assign a conversion factor, to tabulate a safe diving depth,” he explained. “So let’s say the sample imploded at twelve hundred metres. You apply a conversion factor of six, and you get a rating of two hundred metres.” He paused, and spoke slowly, to make sure I understood the gravity of what followed. “It’s specifically not called a safety factor, because the acrylic is not safe to twelve hundred metres,” he said. “I’ve got a massive report on all of this, because we’ve just had to reverse engineer all of Jerry Statchiw’s work to determine when our own acrylic will fail.” The risk zone begins at about twice the depth rating.

According to David Lochridge’s court filings, from 2018, Cyclops II’s viewport had a depth rating of only thirteen hundred metres, approximately one-third of Titanic’s depth. It is possible that this had changed by the time passengers finally dived. But, Lochridge’s lawyer wrote, OceanGate “refused to pay for the manufacturer to build a viewport that would meet the required depth.”

In May, Rush invited Victor Vescovo to join his Titanic expedition. “I turned him down,” Vescovo told me. “I didn’t even want the appearance that I was sanctioning his operation.” But his friend—the British billionaire Hamish Harding, whom Vescovo had previously taken in the Limiting Factor to the bottom of the Mariana Trench—signed up to be a “mission specialist.”

On the morning of June 18th, Rush climbed inside the Titan, along with Harding, the British Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood, and his nineteen-year-old son, Suleman, who had reportedly told a relative that he was terrified of diving in a submersible but would do so anyway, because it was Father’s Day. He carried with him a Rubik’s Cube so that he could solve it in front of the Titanic wreck. The fifth diver was P. H. Nargeolet, the Titanic expert—Vescovo’s former safety adviser, Lahey and McCallum’s old shipmate and friend. He had been working with OceanGate for at least a year as a wreck navigator, historian, and guide.

The force of the implosion would have been so violent that everyone on board would have died before the water touched their bodies.

For the Five Deeps crew, Nargeolet’s legacy is complicated by the circumstances of his final dives. “I had a conversation with P. H. just as recently as a few months ago,” Lahey told me. “I kept giving him shit for going out there. I said, ‘P. H., by you being out there, you legitimize what this guy’s doing. It’s a tacit endorsement. And, worse than that, I think he’s using your involvement with the project, and your presence on the site, as a way to fucking lure people into it.’ ”

Nargeolet replied that he was getting old. He was a grieving widower, and, as he told people several times in recent years, “if you have to go, that would be a good way. Instant.”

“I said, ‘O.K., so you’re ready to fucking die? Is that what it is, P. H.?’ ” Lahey recalled. “And he said, ‘No, no, but I figure that, maybe if I’m out there, I can help them avoid a tragedy.’ But instead he found himself right in the fucking center of a tragedy. And he didn’t deserve to go that way.”

“I loved P. H. Nargeolet,” Lahey continued. He started choking up. “He was a brilliant human being and somebody that I had the privilege of knowing for almost twenty-five years, and I think it’s a tremendously sad way for him to have ended his life.”

Lahey dived the Titanic in the Limiting Factor during the Five Deeps expedition, back in 2019. I remember him climbing out of the submersible and being upset at the fact that we were even there. “It’s a mess down there,” he recalled, this week. “It’s a tragic fucking place. And in some ways, you know, people paying all that money to go and fly around in a fucking graveyard . . .” He trailed off. But the loss of so much life, in 1912, set in motion new regulations and improvements for safety at sea. “And so I guess, on a positive note, you can look at that as having been a difficult and tragic lesson that probably has since saved hundreds of thousands of lives,” he said.

OceanGate declined to comment. But, in 2021, Stockton Rush told an interviewer that he would “like to be remembered as an innovator. I think it was General MacArthur who said, ‘You’re remembered for the rules you break.’ And I’ve broken some rules to make this.” He was sitting in the Titan’s hull, docked in the Port of St. John’s, the nearest port to the site where he eventually died. “The carbon fibre and titanium? There’s a rule you don’t do that. Well, I did.” ♦

— Ben Taub, A Staff Writer, is the recipient of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for feature writing. His 2018 reporting on Iraq won a National Magazine Award and a George Polk Award.

#Titanic | Ocean | Accident#Submarines | Innovation | Whistle-Blowers#Titan Submersible#The New Yorker#A Reporter At Large#Ben Taub

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-61723806

Scientists have made the most precise map yet of the mountains, canyons and plains that make up the floor of Antarctica's encircling Southern Ocean.

Covering 48 million sq km (18.5 million sq miles), this chart for the first time details a new deepest point - a depression lying 7,432m (24,383ft) down called the Factorian Deep.

Knowledge of the shape of the ocean's bottom is essential to safe navigation, marine conservation, and understanding Earth's climate and geological history.

But we still have much to learn.

Vast tracts of terrain have never been properly surveyed.

The IBCSO project and others like it around the world are gradually filling in the gaps in our scant knowledge of the bottom of the world's oceans.

Ships and boats are being encouraged to routinely turn on their sonar devices to get depth (bathymetric) measurements; and governments, corporations, and institutions are being urged not to hide away data and put as much as possible into the public domain. This is paying dividends.

The new map covers all the Southern Ocean floor poleward of 50 degrees South. If you divide its 48 million sq km into 500m grid squares, 23% of these cells now have at least one modern depth measurement.

That's a big improvement on nine years ago.

Better seafloor maps are needed for a host of reasons.

They are essential for safe navigation, obviously, but also for fisheries management and conservation, because it is around the underwater mountains that marine wildlife tends to congregate. Each seamount is a biodiversity hotspot.

In addition, the rugged seafloor influences the behaviour of ocean currents and the vertical mixing of water. This is information required to improve the models that forecast future climate change - because it is the oceans that play a pivotal role in moving heat around the planet.

"We can also study how the Antarctic Ice Sheet has changed over thousands of years just by looking at the seafloor," explained Dr Rob Larter from the British Antarctic Survey. "There's a record of where the ice flowed and where its grounded zones (places in contact with the seafloor) extended. This is beautifully preserved in the shape of the seafloor."

One key finding in the years between the first and second versions of IBCSO is the recognition of the Southern Ocean's deepest point. It's a depression called Factorian Deep at the far southern end of the South Sandwich Trench. It lies 7,432m down. It was measured and visited by the Texan adventurer Victor Vescovo in his submarine Limiting Factor in 2019.

The remote and often inhospitable nature of the Southern Ocean means substantial sections of it are unlikely to get mapped unless there is dedicated undertaking. There's high hope that an emerging class of robotic vessels could be given this task in the years ahead.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

since i seem to be becoming a titanic guy, ive decided to just lean into it and explain the best i can, in laymans terms, what happened to titan and why the design had been criticised by experts in the deep-sea diving community.

i will preface this with the fact that im not an engineer. i have a psychology degree so this is not in my wheelhouse; im simply attempting to relay the information that has been made public in a more layman-friendly way. if i get anything wrong, please correct me.

a second preface is that quite a lot of this post is relying on oceanliner design’s video on this topic. though hes less critical of oceangate than i am, mike does a great job of breaking everything down so anyone can understand it. [any statements i make without listing a source are likely to be information from this video]

so with that out of the way, lets jump into it:

first, lets talk about what titan was. ive seen it described as a submarine by many people and im pretty sure ive also described it as such, but titan was a deep-sea submersible with a guiding philosophy of simplicity.

whats the difference between them?

submarines are self-independent vehicles meaning they do not rely on exterior support.

meanwhile, submersibles can submerge and can act independently to an extent, they primarily rely on exterior support such as being tethered to the mother-ship, or in titans case, receiving navigational inputs from said ship.

and here we meet our first bit of criticism; almost all other submersibles do not rely on external navigational inputs. they have their own equipment and systems for this. it may seem trivial, but as oceanographer peter girguis points out, these systems are as important for navigation as they are for the safety of the crew. [x]

when you are in water that deep, you need to know your exact position and be in constant contact with the mother ship. and its not as if oceangate did not have access to this technology, the beacons they use are commercially available. instead, they relied on short texts as a form of communication which is simply unacceptable. the submersible limiting factor has real-time verbal communication between those in the sub and those on the mother ship on dives 27,000 feet deeper than the titanic wreck.

“titan [did] not appear to have some of the other kinds of sensors, beacons and other systems that we use in research, that are also important just to maintain contact.”

“titan was not designed with research in mind.”

most deep-sea submersible designs are based around the design for the dsv alvin as it was one of the first of its kind. you might ask why its alvin that designs are based around and not another. well that would be because alvin was launched in 1964 and is still in use today and has completed over 5000 dives.

and this is why so many in the deep-sea submersible community are so outraged at titans design. titan was around 5 or 6 years old when it imploded; alvin is 59 this year. we have the technology to create submersibles like alvin or limiting factor that are arguably safer to be in than on the deck of a ship [x]; this disaster should never have fucking happened.

okay, so now lets move onto the actual design of titan which differs very much to most other deep-sea submersible and this is not a good thing. the reason most designs are so similar is because these features have been shown time and time again to be safe. again, ill refer to what peter girguis stated:

anyway, ill get back on topic. this is alvins design:

alvins pressure vessel is a large sphere with titanium walls that are 2 inches or 5cm thick. titanium is used as it is a very strong metal as whathisname from 2012 sang about, and a sphere is used because its the best shape for equally distributing pressure. when designing these vessels, you do not want any areas where pressure can build up and a sphere does not have any; the entire structure reinforces itself.

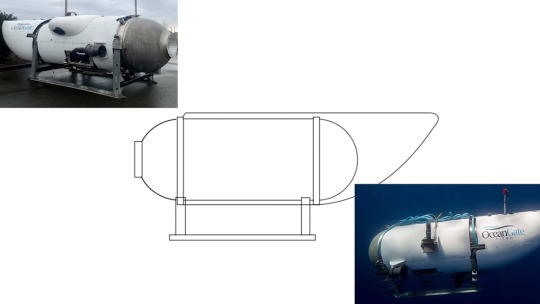

unlike literally every other deep-sea submersible, titans pressure vessel was not a sphere and not made of titanium, rather it was cylindrical with two hemisphere on either side and was built out of carbon fiber. see the shape below:

the important part is the big circle labelled “personal sphere”. this is called the pressure vessel and is where crew and any equipment needing protection from the water pressure reside. this vessel needs to be able to withstand around 6000 pounds or 3 tonnes of pressure per square inch, which is about 400 times the pressure on the surface.

if they had followed previous designs, they would have had to make a much larger sphere in order to fit everyone. but the bigger you make your sphere, the weaker it becomes so you then have to use thicker walls, and all of this makes the pressure vessel much heavier. and this is where youd run into problems because the submersible still needs to be able to plucked from the ocean at the end of the trip and to power itself in the water. the heavier it is, the harder this becomes.

first, well address the shape. as the design philosophy of titan was so that it could carry up to 6 passengers, it would have been very difficult for the pressure vessel to be shaped as a sphere. alvin, in comparison, can only fit three crew and equipment.

so instead, they chose a cylinder. this is not a terrible choice by itself. it is preferable to use round shapes in high-pressure environments as pressure builds up in corners, especially right angles. if youve ever wondered why plane windows have round corners, its because the square windows on the de havilland comet (the worlds first jetliner) gave areas where pressure could build up and caused the jet to suffer a series of explosive decompressions. it crashed many times. [x]

now, well get into where the design really has problems: the materials used. as i mentioned, the majority of the pressure vessel was made of carbon fiber. the ceo of oceangate, stockton rush, believed that carbon fiber would have a better strength-to-buoyancy ratio than titanium, and this was one reason why it was chosen. [x]

so in terms of shape, its not the worst choice. it is much preferable to use a sphere as a cylinder is not as adept at equally distributing pressure, but their choice was at least logical.

on the end of the cylinder, there were two titanium rings bonded to the carbon fiber hull (though the method of bonding is not publicly available), and these rings were then bolted to two titanium hemispheres. now, you might notice that titan does have four right angles in the pressure vessels, but these are within the vessel so as long as no pressure can get into vessel, these are fine.