#uaf secret santa

Text

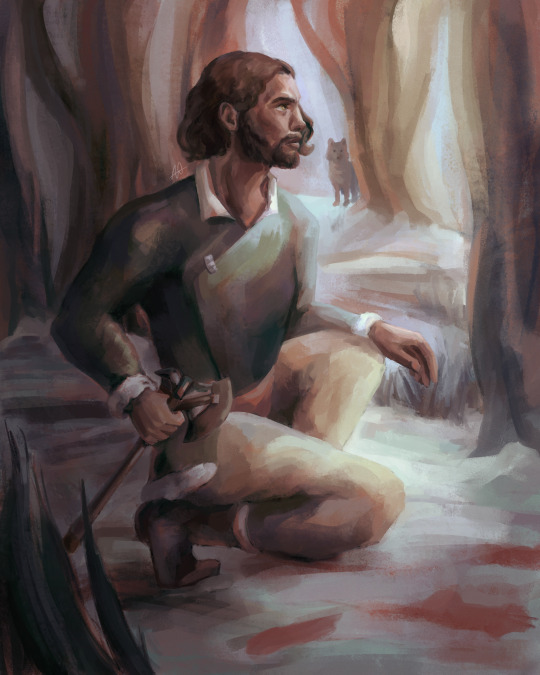

Happy holidays @bannerman-for-the-band! Here’s a wintery Perrin following a bloody trail in the snow-covered woods, along with some canine company 😄

#wot secret santa 2022#wheel of time#unreasonably attractive fandom#perrin aybara#uaf#wot secret santa#listen so I didn’t remember if you have seen/like the show so I didn’t do show!Perrin#also this painting killed me#idk why#i just forgot how to draw#as one does#anyway#my art#digital art#fan art

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy holidays @adurna0! This is @miekkamaisteri as your @feast-of-lights secret santa. Have an Ishamael :)

#wheel of time#the wheel of time#unreasonably attractive fandom#wot secret santa 2020#wot secret santa#uaf secret santa#ishamael#cw: animal death#nothing serious but the rat is technically being killed to lets play safe

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fic: Fly Me To The Moon

Happy Holidays @rosie-with-knives! I'm your Secret Santa for @feast-of-lights.

You had a preference for gen fic, so I very logically wrote you 12,350+ words of Talaan din Gelyn and Bodewhin Cauthon teleporting to the moon. It's about friendship and family and Robert Jordan's batshit worldbuilding.

I really hope you like it!

https://archiveofourown.org/works/28398306/chapters/69585366

(Thank you to @anyboli for the quick beta-read!)

#rosie-with-knives#wheel of time#unreasonably attractive fandom#wot secret santa 2020#uaf secret santa#wheel of time fanfic#talaan din gelyn#bodewhin cauthon#fly me to the moon#my art

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wheel of Time Secret Santa: Sign-Ups Are Open

The end of the year grows near (finally!) and it’s time for Secret Santa again!

This year we’re starting a little late so there will be some minor changes to the schedule (which could be found here).

Sign-up form could be found in the reblog because Tumblr hates links.

There is no quality requirement or word count, your gift can be a fanart, fic, edit, playlist or anything else as long as you put your heart into it!

Also, please respect your giftee’s Do Not Wants and don’t spoil them if they haven’t finished the series yet.

Please let me know if you have any questions!

#wheel of time#wot secret santa#wot secret santa 2020#uaf secret santa#unreasonably attractive fandom

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

This year has been extremely stressful for us all and we have a lot on our minds but are we doing any winter holidays' fandom events this year? People who are usually organising things, as far as I know, weren't active here on tumblr for quite a while.

It's November already so there would be less time, but if people are interested I could take a stab at organising something.

#wheel of time#unreasonably attractive fandom#uaf secret santa#i have never done anything like that before but i could give it a go#dasha speaks

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

UAF Secret Santa

Merry Christmas unreasonably attractive fandom! This is my Secret Santa gift to @herenya-sedai. You asked for Post-AMOL Mat dealing with a daughter who can channel, and, wow, did that open up a can of worms in my brain. I hope you enjoy this fic! It’s also on AO3, if you have a preference for platform <3

.

Nora, Nora

The first few months are the hardest. He sees them in the gardens, in the halls, in unfamiliar Seanchan streets, grey dresses swishing around thin ankles, silver bands making red rings around gaunt necks. They walk with their eyes lowered, lips pale and thin, betraying no emotion, followed, always, by tall pale women with cold faces, silver bracelets glinting under the harsh sun. Some of them are dark, others pale, some willowy and tall, others short and homely, but he sees one face on all of them: dark eyes, lips quirked just so, mouth opening to berate him, most likely, with the words of a harried mother despite the fact that she was the youngest of them all, always in such a hurry to grow up, growing up too fast, burning too bright until she burned out—

He left all that behind when he came to Seanchan, but it clings to him, still. His days are wide open and empty; Tuon has crushed the rebellions against her, but Seanchan politics are a web rivalled only by the White Tower itself and she spends her days fixed firm on her throne, Min rarely released from her side. There are no more battles to be fought. Mat feels himself fading, drifting into the background, a small piece of the scenery. He spends long hours wandering the city, studying the winding streets, acquainting himself with the taverns, memories flitting in and out of sight. Sometimes he drifts into an alley, or an alcove, or a dusty bazaar, and stands there for hours, dreaming of lives lived and long passed in this strange empire.

In his wanderings, he learns where they are kept. It’s a dark room, deep underground, walls studded with pegs holding gleaming bracelets. The new ones huddle in quivering groups on the cold floor. The old ones lie alone, eyes blank and dull, breaths so shallow they could almost be dead. It takes him a week, even with his luck, to find a way in: a tunnel from a bygone Age, forgotten by everyone in this generation, perhaps, but not by the men in his memories. He doesn’t use a torch, the first time, half-afraid of being caught, and as he creeps slowly through the dark, he wonders what Tuon would say.

He can’t do much. There are so many of them. He brings them sweetbreads and kaf, and it’s not enough. He brings them balms for their wounds and wine for their souls, and it’s not enough. He brings them stories of the outside world, of hope, of home, and it’s not enough, never enough. Most days, as he slips back into the darkness, he thinks all he can bring them is more disappointment.

.

On the third day of the eighth month, he lets one go. It is a foolish idea and he is not, contrary to popular belief, a fool, but she’s so young and scared, still with a spark of defiance in her large, dark eyes as she sits, unattended, in the garden, waiting for her sul’dam to collect her, and he’s done it before, knows how, and when he unlocks the necklace she smiles—

They catch her before dusk. They do not put the silver band back around her neck. When they are done with her, she has no neck to put it on.

Tuon is silent in court. She lets the girl’s sul’dam make the decision, and gives only an imperial shake of the head when asked if further inquiry is needed. Her eyes remain fixed on the girl throughout, never straying.

In the night, she comes early to the room they share. She sits there in bed, thin blankets pulled around her waist, back straight as the mast of a ship despite how large her stomach has grown, almost half her own size, it seems. It’s the first time he’s seen her by moonlight in weeks.

“Never do that again,” she says softly. “Remember that I will soon have my heir. I can kill you now, if I wish.”

Mat looks at her. He almost can’t see her eyes in the darkness. “Egwene told you—”

“The Amyrlin Seat was mistaken.” An edge of frost coats her words. “I know how to protect my people.”

“That girl wasn’t dangerous. She was barely a woman. In the Two Rivers she might not yet be allowed braids.”

Tuon’s voice softens, but her eyes are hard and cold. “You have a kind heart, Toy. I will forgive you this time.” Hard and cold—the eyes of one who was born with a crown already fixed on her head. “But never again.” She holds out a hand for him.

“Never again,” Mat echoes, and goes to her.

He passes the tunnel, sometimes, and there is a catch in his step before he keeps walking.

.

It’s raining the day everything changes—but a pleasant rain, if there is such a thing. It’s the kind of rain that reminds him of summer afternoons spent splashing through the creek, tearing newly bloomed wildflowers from trees, sticking them haphazardly in Perrin’s hair because the stems slid so smoothly between his curls and stuck. He watches the rain drip off the tiled cover above the window, falling heavily on petals in pink, yellow, and white. He watches for so long that he forgets the bouquet is getting soaked, but it doesn’t matter, because, when he hears the first cries, he jumps so hard he drops it out the window anyway.

He turns around, and there is Min, eyes wide, arms wrapped gingerly around a bundle of white, while on the bed Tuon sobs and laughs, for once too drained to keep composure. Mat walks to Min, takes the bundle into his arms. He looks down at a round face, brown in hue, eyes clenched shut, but he knows they will be the darkest brown. His daughter. His daughter.

It’s so terrifying a thought that he nearly drops the baby. Min catches his eye, grins, takes the child back and hands her off to Tuon’s waiting arms. Tuon looks at their daughter, and then at him, and, for once, smiles.

“You look frightened.”

“I never saw myself as a father,” Mat says, honestly. “I’m— I’m just— the village idiot.”

Min snorts. Tuon’s smile deepens.

“You are the greatest general that has ever lived,” she says, and her voice is so warm. “This is nothing.”

Mat gives her his most impish grin, and turns away before she can see it strain. Not for the first time, he wonders who it is his wife really loves.

.

Years pass faster than comprehension. Mat steals hours with his daughter like the rarest diamonds, moments between long sessions under locked doors when Tuon and her Court teach Enoura how be an empress. Tuon complains every day that five minutes with Mat undo three days of her work at a time. Mat takes it as a the highest honor.

He teaches his daughter how to dance, how to gamble, how to look at a horse and know how fast and how true it will run. She has Tuon’s eyes, Tuon’s steel spine, Tuon’s imperious voice—but she has his smile, he thinks, and his laugh.

When Enoura is one year old, she says her first word: “Dada.” Mat gloats for hours, and his satisfaction is barely touched by the fact that Tuon does not speak to him for the two weeks it takes before Enoura learns to say “Mama.” Even then, a coat of ice frosts her eyes for several weeks longer. Their marriage is only mended a month later, when Min, having drunk slightly too much, reveals that Enoura’s first word was actually, in fact, “Min.”

When Enoura is four years old, she splashes through a mud puddle half as deep as she is tall, and ruins the dress given to her specially for her True Name Day. She trails back into the palace half an hour later, tugged along by her latest tutor (none of them seem to last longer than a few weeks), face sullen, thoroughly disgraced. Tuon arches a single eyebrow when she sees her, fingers drumming on her knees—which, for Tuon, is the equivalent of pitching a fit. Mat fails to bite back a laugh—Light, but how many times had his own mother given him that same expression?— and is sent out of the room.

When Enoura is six years old, she wanders out of the garden gate and disappears. The Seanchan Empire itself seems to grind to a halt. Servants and soldiers alike are sent out in droves, and Tuon locks herself in a dark room with Min, admitting one courtier at a time, until she is certain that none of them are to blame. Mat finds the hidden spaces no one else can; for once, he is grateful for the memories in his head. He finds her when the sun has almost set, crouched behind the thick creeper plant obscuring a shallow alcove where two abandoned buildings meet. She is crying, and she cries harder when she sees him, and as he presses her to him, feeling relief wash over his bones, he decides that she will never cry like this again.

When Enoura is nine years old, Mat feels his medallion go cold. His daughter is standing behind him when he turns, palms stretched in front of her, face scrunched with concentration. She drops the pose when she sees him looking, blowing a mound of brown curls away from her face, and sticks out her lip. “I’m trying to blow you over.” As if to illustrate, a faint gust of wind drifts past Mat. Enoura huffs. “It’s not working.”

The medallion is so cold—and then it isn’t. He feels a shiver run through his body—part of him thinks it can still feel the thin weaves of Air, saidar spinning nets around him. Spun by his daughter. Mat feels his feet move; he goes to her very slowly, kneels in front of her, takes her hands. His eyes flit around the room; the door is closed, the window is shut and barred, there are no servants present, Tuon is far away in the throne room. No one is here. No one has seen. No one but him. He looks at his daughter, at her bright eyes, large and dark. He thinks of a rainbow stole around too-small shoulders, a thin scar around a thin neck that never quite went away.

“Nora,” he says. “Never do that again.”

.

Saidar, it turns out, is not something that can be controlled so easily. He learns this as he stands in a room full of broken pots and spilled dirt and flowers that weren’t there five minutes ago, and he screams at his daughter for the first time.

Enoura starts to cry and Mat feels all the air leave his body. He drops to his knees in front of her, gathers her into his arms, smooths a hand over her frizzy hair, feels the little leaves and twigs still hidden amongst the curls from the floral rain she created moments earlier.

“I’m sorry,” he whispers, so quiet he can’t quite tell if he’s really said it out loud. “It’s going to be okay. I’m so sorry.”

Slowly, gulping big shallow breaths, Enoura starts to calm down. Mat releases her and draws a cloth from his pocket. Carefully, he wipes her tears away, so that her face is dry. He sits her down with her back to him and picks out the leaves, one by one, until her hair is fit for the royal court. Her eyes stay red-rimmed and fearful, though, and he tries not to look at them, feels them bore holes into him as he tugs her quickly through the halls.

Min jumps when he slams the door open, brows drawing sharply down. Then she sees Enoura and her eyes widen, flitting between them.

“The One Power,” she says slowly. Enoura’s lip begins to tremble. It takes all of Mat’s strength not to let himself have the same response. He nods. He and Min look at each other, and Mat can see his face reflected in her eyes, pale and afraid. Min hugs her arms. “Right,” she says. “Right.”

“Can you help her?” Mat’s voice is strained and hoarse; he has to force the words out. “You were in the Tower before— can you help her?”

Min bites her lip. She looks so sad. “I don’t know. Maybe. I can— we can try.”

“I’m sorry,” Enoura whimpers. Her hand is trembling in Mat’s. “I’m sorry. I won’t do it again. I won’t do it again, I promise!”

Mat grips her hand tighter. “You didn’t do anything wrong, Nora. Don’t let anyone tell you you ever did anything wrong. We just— we need to be careful.”

“Careful,” Min echoes. She closes her eyes, shakes her head, takes a deep breath. “I heard... sometimes, when I got bored, I would talk to the Novices or sit in on their lessons. I might… I don’t remember much, but I might be able to… help her control it better. With luck.”

“Luck is all I have,” Mat says.

The sun begins to set. Enoura sits on the ground, legs crossed, mirroring Min’s posture, hands clutched in Min’s, eyes closed.

“Picture yourself as the bud of a rose,” Min murmurs. Mat sags against the wall as a faint ball of light hovers over their hands and Enoura smiles. “You are the bud and the bud is you…”

“I am the bud and the bud is me,” Enoura echoes.

Mat closes his eyes.

.

Years pass faster than comprehension. Enoura turns twelve. The palace is abuzz as sul’dam prepare to test their proxies—and their new damane . Mat sits locked away in his chambers, Enoura curled in his lap. She is getting too big for that, now, but even as he begins to lose feeling in his legs, he can’t fathom letting her go, not when he looks out of the window and sees the rows of girls her age all lined up, sul’dam circling them like sharks in the water.

Tuon will know what to do. He tells himself that, over and over, as the clock ticks. Tuon is the Empress, and she is Enoura’s mother, and she will not let their daughter be harmed, will not let her be collared, will not let her be used. Memories flit behind his eyes of a girl in a grey dress, only slightly older than Enoura, eyes wide and frightened as she is dragged into the Court, made to kneel before Tuon, made to face judgement for Mat’s mistake—

He shakes the memories away. Enoura will not be— protecting his child will not be a mistake. It can’t be.

Tuon will know what to do.

He grips Enoura’s hand as they hurry to the gardens. Tuon sits on an elevated throne, gaze unwavering, almost unblinking as girl after girl is brought forward and tested. Mat’s grip on Enoura’s hand becomes so tight that he can almost feel her bones shifting. He takes deep breaths, loosens his grasp, runs a hand through his hair, tries to look calm and presentable. He approaches his wife.

Tuon does not look away from the assembled girls when she says, “What is it?”

“I need to speak with you. Please,” he adds belatedly, as the sharp eyes of her guards swing reproachfully his way. “It’s about Nora.”

“Enoura,” Tuon corrects, as she always does. Her eyes flick to their daughter and grow warm. “It is almost time for you testing, daughter.”

Enoura shivers, pressing close to Mat. Mat looks down at her, and then at Tuon. “Can we speak privately?”

Tuon sighs, but she lifts a hand to the sul’dam and rises from her throne. Pulled Enoura gently away from Mat, she deposits her with the guards and follows Mat out of the garden. Her guards stare after her, eyes narrowed, as Mat leads her away from listening ears, into an alcove sheltered by creeping vines and blue roses. It was in a place not unlike this that Enoura was conceived.

“Tuon,” he says.

She looks at him, half expectant, half impatient. Even now, away from everyone, her back is straight, her hands folded primly over her stomach. As always, though she stands at half his height, she seems to be looking down at him with those cold, piercing eyes. She will know what to do. She will know how to keep their daughter safe. She has to.

“Tuon.”

She lifts an eyebrow. “Toy.”

He has to tell her. He opens his mouth. He has to tell her. For Enoura’s sake. For Enoura…

“Tuon,” he says, “Min had a viewing.”

Tuon’s eyes glow as he talks. He is barely aware of his own words; they tumble out of his mouth like rocks making deep pits in his stomach. He tells a story. He has always been good at lying.

Tuon returns to the garden. She sits in her throne, overlooking the rows of trembling girls, some weeping because they are damane, some because they are not. Enoura is summoned. She stands beside her mother and watches with wide, frightened eyes as a silver band is strapped to her wrist.

“Enoura,” Tuon announces, the hints of a smile touching her lips. “My daughter, destined to be the most powerful sul’dam this land will ever see.”

A cheer goes up. Enoura’s head swings around; she stares at Mat.

Mat turns away.

.

“She will make a fine Empress,” Tuon hums, seated on her garden throne, silken white dress draped so that the cloth falls open to frame crossed legs. Her fingers drum silently against the stone armrest. Mat stands at her side and they watch Enoura instruct her damane together. “A fine Empress,” Tuon muses, “if only she would learn to be stricter with them.” Her eyes flit briefly to Mat, hints of warmth just breaking through. “She has too much of your kindness, Toy. I wish she would display more of that lion you keep so well hidden, too.”

I am not a lion, Mat wants to tell her. I am a fox with a loud bark and silver feet. I am a raven with clipped wings. I am a man trapped in the weaves of a Pattern I cannot comprehend. I am not the memories in my head.

Instead he nods silently, and watches his daughter struggle to keep the pain off her face as her damane again tries, again fails, to pour a pitcher of water. How long before that smooth, blank face ceases to be a struggle? How long before it comes naturally to her? How long before she stops feeling the damane’s pain at all? Enoura glances back at him, eyes large and dark and pained and lost, and he looks away.

It has been weeks since he was able to meet his daughter’s eyes.

.

Enoura is sixteen years old and sobbing. The full moon gleams in the tears that stream down her face, thin creeks of silver starlight making lines down her cheeks, splashing onto the cold stone of the terrace wall. Mat watches her and feels like weeping himself. In one hand she clutches the silver bracelet, and it trembles in her grasp. The other hand strays to her neck, lacquered fingernails pressing into it, hard enough to leave angry red marks.

“I should be wearing this here,” she sobs. “I should be one of them, I should—”

Mat pulls her close, pressing her face to his chest, muffling her words, eyes scanning the darkness for watching eyes, listening ears. With one hand he smooths her hair, over and over, as he did when she was little. Her curls are not as unruly as they used to be, cut short and flattened by a gleaming crown she used to complain hurt her ears. She doesn’t complain any more. She doesn’t laugh like she used to, or smile, or chatter. Mat wonders how there could ever have been days when he wished she would stop talking, if only for a moment. She is not talking now. Her muffled sobs pierce his ears with every other breath. He holds her tighter.

What can he do? What can he say to help her, to comfort her? There is no silver lining to Enoura’s struggle, only the simple fact that she is alive and uncollared. How much comfort is that, when the price of her freedom is the slavery of women who in any other life would be her sisters?

Tuon once told him that empresses do not love, but Mat doesn’t think that is true. He sees love in her when she smiles at their daughter. He sees it in her eyes when she travels into the city, when she looks out at her people, shining with pride for her empire. He sees love in her smile when they stay up together into the dawn and she calls him a lion, and he wonders if there is any part of him she loves more than the men in his head, and the battles they have won.

Empresses love, Mat is certain of that, but he is not certain how far that love can be tested. He is not certain how love measures up against the world’s most powerful empire, an empire built on slavery, an empire with servitude so deeply ingrained into its culture that the very notion of viewing damane as people is not worth consideration, because it is a notion that would tear the empire apart if given more than a moment’s thought.

Enoura’s sobs fade into shuddering breaths. Mat rests his head on hers and thinks of a girl, not ten years old, making little balls of light and laughing.

“Luck is all I have,” he had said, that night.

He wonders how far his luck can carry him. He wonders if he can trust it one last time. Choices spin through his head and he wishes, for the first time, that the dice would come back and spin, and spin, so that he could know which decision is the right one. He hopes he can trust his luck.

Mat pushes Enoura gently away. Cupping her face in his hands, he wipes away her tears, and tries to smile.

“It’s going to be okay, Nora,” he whispers. “Here is what we’re going to do.”

.

el’Nynaeve ti al’Meara Mandragoran turns from the window as a liveried servant slips through the door. She has to bring a hand up to steady the crown that threatens to slip at her quick movement; it has been so many years, and yet the Crown of Malkier still feels foreign against her forehead. Not that she would trade it, nor what it signifies, for all the world.

“Yes?”

“Queen Nynaeve, two travellers seek audience with you.”

Nynaeve blinks. “With me? Not with Lan— I mean, not with the King?”

“Yes, Queen Nynaeve.”

“And without any notice…” Nynaeve’s hands stray to her braid. “See them in.”

The servant bows and slips back out of the room, and Nynaeve sighs, her frown half of impatience and half of concern. Who would ask to see her, and only her, so suddenly, without notice?

The door opens. Two cloaked figures enter the room, one half the height of the other. Nynaeve’s frown deepens.

“Who are you?”

The smaller figure shrinks back, pulling down the hood to reveal unruly brown curls—some motherly instinct in Nynaeve screams the need to brush this child’s hair—and dark, strangely familiar eyes. But it is the second, taller figure that draws a gasp from the Queen of Malkier, as the hood is pulled back to reveal gleaming brown eyes and a wide, impish grin. Nynaeve’s fingers tighten around her braid. She can already feel a headache approaching.

“Hello, Wisdom,” Mat Cauthon says, insolent as ever. “Could I trouble you for a place to stay?”

.

#uaf secret santa#wheel of time#wot#wot fic#mat cauthon#can you tell i have Strong Emotions about mat cauthon#the wheel of time#tuon paendrag#nynaeve al'meara#min farshaw#seanchan#saidar#wot spoilers#wot spoiler#amol spoilers#wot a memory of light

125 notes

·

View notes

Photo

UAF Secret Santa gift for @insomnia-productions. Mat and Rand back home, where nothing bad is happening, herding sheep being cute with flowers.

#UAF Secret Santa#rand al'thor#mat cauthon#Wheel of Time#wot#wotart#mine own#still not over the fact that mat canonically puts flowers in his hair#also sorry this is not very in season#i mean unless you're in the southern hemisphere

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

did you know that chromebooks have the most godawful cameras?

anyways, for this year's uaf secret santa, I was assigned @sielustaja, who requested egwene being a badass. hope this contains an acceptable amount of badassery, and happy holidays!!!

#uaf secret santa#Wheel of Time#wot#egwene#egwene al'vere#matt scribbles#i actually had a lot of fun making this not gonna lie

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

WOT fic: Not So Different

For @sun-dari, for the UAF Secret Santa. With many apologies for being so late.

Tam tries to understand why his son is hurt.

Sometimes being a father was not so different from being a captain.

Tam had served under men who liked to rant and roar whenever young men stumbled in with grazed hands and red puffy faces: “What are you doing fighting each other, you addled sons of goats? Keep it for the battlefield!” When he became a captain himself, Tam chose instead to save his breath. It was far more effective to have a quiet word with a lad’s friends, if the lad needed help tending to his injuries or getting to bed, and then assign him to dig latrines for the next week. Arduous tasks which kept the hands busy and gave the mind time to think was all that some needed to sort out their own problems, and as for the rest, at least then they were too busy to get into any more trouble.

But when it was his own small son who came home bruised and teary, Tam could not feel so indifferent.

“Tell me what happened,” he ordered as he lifted Rand up onto the table to better inspect his injuries. “Tell me everything important.”

But Rand’s idea of everything was not the same as his father’s, nor was his idea of important. He told Tam about the birds he had seen and the funny shapes his friends had found in the clouds, and the number of stones the two of them had thrown into the pond. His account was about as useful as that of a certain sentry Tam remembered who had been too busy watching the sunset to notice how many horses were coming over the hill. (Although if Rand had stood in the sentry’s boots, with his newly discovered enthusiasm for counting things, he would have known the number of horses. Just not what direction they were headed in. Or whose army they belonged to. But Rand had not known how to lace his own boots for very long, which could not be said for the sentry.) Tam refrained from sighing. He had a lot of practice at that.

As Rand kept talking, his breathing became steadier and the indignant tone faded from his voice. This was fine if Tam’s objective was to calm his son so that they could eat their supper and go to bed. There were days when that was all Tam wanted to achieve. His career had been a series of exercises in choosing his battlefields carefully, and even though he had left that life behind him, he kept finding a new appreciation for wisdom that had been drummed into him through years of advice and experience. Know your goal. Know your enemy. Stay focused.

Sometimes being a father was not so different from being a captain.

There were gaps in this story of Rand’s. There were often gaps in Rand’s stories and Tam had reason to be grateful for them, because if Rand recited his every thought and action, there would be neither peace nor sleep in their house. The question was: Are these gaps important?

Tam considered carefully. Rand neither looked nor smelled like someone who had fallen into a pond. But it was still likely he had fallen off something. Tam had trained and commanded soldiers who had made him despair of their chances of surviving a battle, but none of them had ever given him moments of terror like the sight of Rand tumbling down. Last spring, Rand had been climbing a tree when one of the branches had cracked. Tam had been leaning against the trunk and had looked up at the noise in time to catch Rand. Rand’s gasp of surprise had quickly been replaced with giggling delight and he appeared to have forgotten all about it by supper time, but Tam had not forgotten. Rand was stronger and taller now, but he had friends to play with and did not always want his father waiting at the bottom of the tree.

“Did you climb any trees?” Tam asked as he finished washing -- and examining -- the scrapes along Rand’s small hands.

“Yes,” Rand said. “Father, you know the big trees along--”

Tam attempted to redirect their conversation before it could turn down yet another meandering path. “Did you fall?”

“No.” Rand paused. Frowned. “My tower,” he said slowly.

“Your tower?”

“It fell! My tower was taller and it fell, and --” Suddenly he was crying again, and leaning forward to press his face against his father’s shirt.

Tam persisted. Fruitlessly. Afterwards, he thought he should have recognised that Rand had no further intelligence to offer when he was in this state and there was nothing to be gained except more tears by trying to persuade Rand to eat all of his supper.

Sometimes Tam wanted to ask other parents if their children also had similar, and similarly inexplicably, outbursts. But he knew how Two Rivers folk liked to gossip. If he ever said anything like that, he would end up with people urging him to marry again, to give Rand a mother.

Kari had been part of Tam’s life for so long that he could not contemplate replacing her so lightly, as if she had been a boot that had worn through at the toe or a tool that had broken. She had been as close, and as important, to him as part of his own body. He had met men who had lost a limb in battle -- and known many more who had lost a limb in accidents off from the battlefields. No one told them to replace their missing hands or legs. Instead they had to learn to live without. Tam had to do the same.

As for Rand, Tam could recall enough of his own childhood to know that small boys cried whether or not they had a mother. And Tam would just have to do his best to unravel any trouble Rand got into, because if Tam did not, no one else would.

Tam hoped that a new morning would bring with it new clarity. He would take his lead from his son, he decided. If Rand was unconcerned, then Tam would trust that what had happened had not been so very serious.

When Rand awoke, his bruises had darkened, but Rand paid them no heed. He was quiet as he and Tam worked their way through their morning chores. Tam watched and waited.

“Father,” Rand said solemnly, as they walked back across their fields. “I am never going to play with Mat ever again.”

Well here it is, thought Tam. “Why?” he asked.

It was not an unreasonable question, he thought, but Rand could be stubborn when he wanted to be. He gave no further explanation.

A part of Tam was tempted to leave the matter there. If Rand meant it, then Tam would not have to worry about Matrim dragging his lad away from his chores and into mischief.

However, he and Kari had been determined that they were not going to give their son any reason to run away to join a foreign army, and Tam suspected that growing up in the Two Rivers would be easier if Rand was friends with the other boys his own age. Leaving home had led Tam to Kari, and to Rand, and he could not regret the the person he had become nor the lessons he had learnt. But he wanted something better for his son. An easier, more peaceful path.

It was a few days before he found the time to take Rand into Emond’s Field. Usually Rand would have disappeared somewhere with Mat before Tam could even see the Cauthon’s front door but this time he marched along at Tam’s side like a small shadow. Tam kept expecting to feel a hand to grab ahold of the hem of his coat, as Rand had done when he was smaller.

They found Abell out in his yard. “Can I have a word with your lad, Abell?” Tam asked.

Abell sighed. “What’s he gone and done now?”

Tam chose to be evasive. “I wanted to ask him about something Rand said.”

“You are welcome to try.”

Young Matrim had a knack for disappearing when he was wanted, and it was tempting to tell Natti that there was no need to hunt for her son today. He bit back the words, because Tam did not like seeing Rand standing so stiff and uneasy. Tam wanted to understand. He wanted answers.

But when Matrim was finally dragged out, wriggling and grumbling, he had no answers. Not ones that satisfied Tam. Asked what he and Rand had done the other day, Mat looked up into Tam’s eyes and said: “I forgot.”

Tam knew how to question a man for information, but it did not matter how carefully he picked his words nor which of the details, told to Tam by Rand, he reminded Mat about. Mat remained adamant that he could not remember.

It was possible. Oh, it was very possible. Tam could remember a time in his own life when a day had felt like forever and yesterday seemed like an age ago. And if it was a deception, Mat carried it out with more confidence than many grown men Tam had met.

Tam did not know what to do with Matrim’s lies any more than he knew what to do with Rand’s stubborn silences. He had had a successful military career, and here he was, thwarted by two boys. Small boys hardly old enough to tie their own boot laces.

“What’s going on?” Abell came over and looked from Tam to the boys. The boys were resolutely not looking at each other, and Tam felt like he was digging a deeper hole for himself.

“Could you send Matrim out to our farm one day next week?” Tam asked. “I want the boys to help me dig some holes.”

Tam did not need any latrines dug and it was not quite the right time of year to be planting, but he could find an excuse for a new fence. If Rand and Mat were not friends again after digging together, then Tam doubted that there was nothing else he could do.

The squabbles of five-year-old boys could not be resolved exactly like the troubles of young men in the army.

But Tam was going to try.

Notes:

here it is, finally. (i’d like to edit further but it is very late and i’d probably just typoes.)

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

happy holidays to @ladypoetess!

i’m happy i got to be your secret santa this year - i wouldve posted from my art blog but i was worried it’d be too confusing. and since i NEVER draw min, elayne, and aviendha i decided to draw them here!

i hope your december is going well! happy holidays and a happy upcoming 2020 to you and the rest of the unreasonably attractive fandom! (ノ◕ヮ◕)ノ*:・゚✧

#angie's art#wheel of time#elayne trakand#min farshaw#aviendha (wot)#uaf secret santa#uaf secret santa event 2019

35 notes

·

View notes

Link

Happy holidays @liancrescent - I’m your WoT Secret Santa! You asked for Forsaken, so have some missing scenes from the Worst Roadtrip Ever

Title: To the City, Lost and Forsaken

Characters: Asmodean, Lanfear, Rand al’Thor (briefly)

Summary: Lanfear and Asmodean's Great and Terrible Roadtrip: it's all fun and games until someone gets betrayed.

Wordcount: 2821

Warnings: none

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

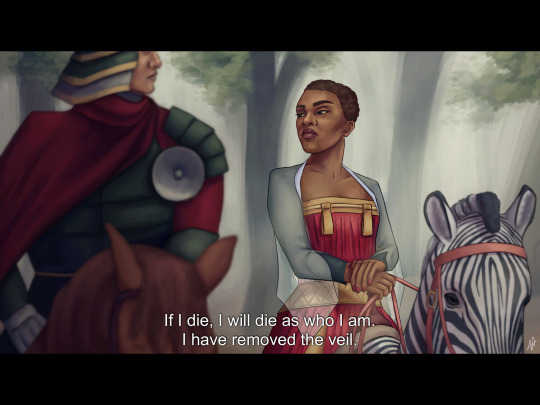

Happy holidays @highladyluck! I’m your secret santa for @feast-of-lights! I’ve spent the past days dying not to make a comment about the zebra 🦓

#wheel of time#the wheel of time#unreasonably attractive fandom#wot secret santa#UAF Secret Santa#wot secret santa 2020#tuon paendrag#my art#digital art#fan art

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

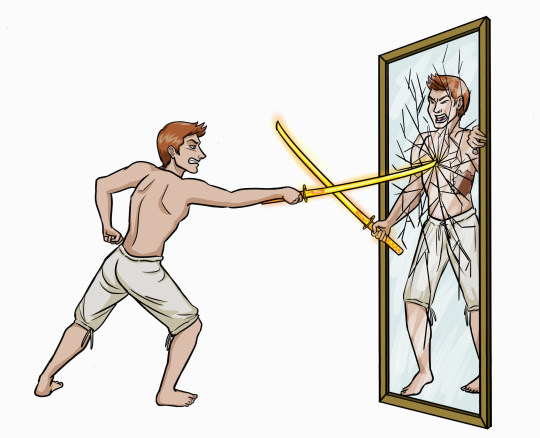

Happy holidays @neuxue!

This is @miekkamaisteri as your Secret Santa, via my artblog. You had the mirror scene from TSR listed in your wishes, so here’s a Rand stabbing at his murderous reflection. May angst this holiday season be fictional only!

#uaf secret santa#uaf secret santa 2019#wheel of time#rand al'thor#the shadow rising#wot secret santa

87 notes

·

View notes

Photo

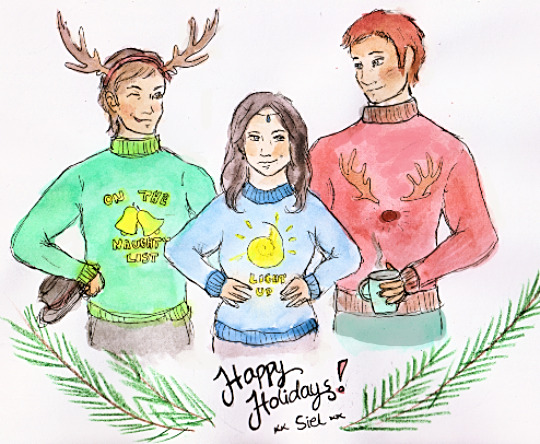

Happy Holidays @glorthelions! I hope you’re having a great time & the year 2020 treats you well.

Bless, Sanni / sielustaja

#uaf secret santa#uaf#wheel of time#moiraine damodred#matrim cauthon#rand al'thor#faux-christmas sweaters are my jam#yes moiraine is standing on a box#rand does not know what to think of mat's head decoration#my art#mine#traditional art

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sign-Up for the WoT Secret Santa!✨

This winter holidays’ party need more people and sign-ups are still open!

Details about the event and the link to the sign-up form could be found here and the schedule -- here

#wheel of time#wot secret santa 2020#wot secret santa#uaf secret santa#unreasonably attractive fandom

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy Holydays @miekkamaisteri !

You asked for Rand/Asmodean, and I was happy to draw them. ‘In Desperate Need Of A Hug’ seems to be the constant mood for both of them, so here it is!

28 notes

·

View notes