#the theory of Heliocentrism

Text

The Jagiellonian University a public research university in Kraków, Poland.

The Jagiellonian University a public research university in Kraków, Poland.

The main assembly hall of the university’s Collegium Maius.

The Jagiellonian University (Polish: Uniwersytet Jagielloński (UJ) a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great.

The Jagiellonian University comprises 16 Faculties, where nearly 4 thousand academic staff conduct research and provide education to almost 40 thousand students, within the…

View On WordPress

#Andrzej Duda#Jagiellonian University#John III Sobieski#King Casimir III the Great#King of Poland#Kraków#Krakow#Nicolaus Copernicus#Nobel Prize in Literature#Notable alumni#Poland#Polish Enlightenment#Pope John Paul II#President of the Republic of Poland#Renaissance#Stanisław Lem#the first UNESCO World Heritage Site in the world#The Jagiellonian University#the theory of Heliocentrism#UJ#Uniwersytet Jagielloński#Wawel Royal Castle#Wisława Szymborska

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Heliocentricity"

The universe doesn't revolve around us.

Made in Procreate.

#album cover#album art#album cover art#record cover#vinyl cover#graphic design#trippy art#graphic art#glitch art#glitch aesthetic#glitchcore#glitch#retro computers#conspiracy theories#heliocentrism#procreate

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

every time people act like Copernicus and/or Galileo personally invented modern astronomy I take one million psychic damage.

#*banging head into a wall*#their work WAS revolutionary#and it SHOULD be celebrated#but to act like they completely reinvented astronomy is just! no!#the heliocentric theory existed as far back as ancient greece!#abu said al-sijzi built a heliocentric astrolabe during the eleventh century!#kepler was already working on his laws of planetary motion before galileo’s observations of jupiter!#fucking god. it ignores all the astronomical work of medieval muslim societies too!#you would not think this would be a problem but i see this a concerning amount. hrrgghh.#Adra rambles#space things

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

going to just scream into the void about health issues and parents because at least the void isn’t supposed to care

so the indeterminate mess that is the downstairs organ-ization (see what i did there?) of my body has been bothering me. best case scenario was “oh it’s just a UTI” and worst case scenario was “well that wasn’t there before”. figured i might as well go gt it checked out by way of regular gynecologist check-up, which i was past due for anyway. get some tests done. get baby’s first mammogram, too, which had me feeling like that pompeii man crushed by that rock. (you think it’s done squeezing and then it crushes you more.)

had to go to the clinic today (third time going two towns over this week fuck everything and the public transport it didn’t ride in on) to pick up a note for the technician for yet another oh my fucking god MRI and grab two lab results on the way. lab results were clear except for some white blood cell action getting over the line in the blood-work. apparently not a UTI. or a yeast infection. or anything else. which...would’ve been better if it had been a simple UTI, man. so, y’know, monsieur concern is back with his top hat.

so my mother. when she picked me up from the mammogram, she didn’t ask me how it went. when i came back with my results, she didn’t ask me how they were. and now, when i went to her to tell her, because *stares into the middle distance* i didn’t get one sentence out before she’s already trying to interrupt me, which she then does. repeatedly. and the conversation ends with her going “yeah i’ve been having pee symptoms lately too you know” like wow. wowowow. it’s always got to be about you, doesn’t it.

#i ain't saying she's a narcissist but heliocentrism looking like a real logical theory in her case omfg#dear mom#randomness

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Stars of Discovery: How Tycho Brahe's Night Sky Observations Paved the Way for Modern Science

In the late 16th century, Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe embarked on an ambitious project. Night after night, for years, he meticulously observed and drew the night sky. This practice, though seemingly simple, was revolutionary. Brahe’s detailed recordings of the positions and movements of stars and planets provided a treasure trove of data that had never been systematically compiled…

View On WordPress

#Data#data collection#empirical data#formulation of a theory#heliocentric model#journey of discovery#knowledge#Nicolaus Copernicus#pattern recognition#scientific method#theory formulation#Tycho Brahe

0 notes

Text

A BIT OF A PONDER

We all know what we believe, what our gut tells us. But before we get too comfortable with even consensus reality – much less the highly suspect “my truth” – just remember how many previous claims of truth or innocence have fallen in the face of fresh evidence.

For instance, it took a while, but recall how the Geocentric model of the universe was made obsolete by the Copernican Heliocentric…

View On WordPress

#Copernican Heliocentric Theory#Dr. Moreau#Eliud Kipchoge#FloJo#Grand Biocentric Design.#Haile Gebrselassie#Kenenisa Bekele#Lance Armstrong#Marion Jones#Schrödinger&039;s cat#Sifan Hassan#Tigst Assefa

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ebook Discount

From June 29 – July 6, Legatus Legionis will be discounted to 99c on Amazon in the US and 99p in the UK. The second book in a series. This is a mix of science fiction and historical fiction. In Athene’s Prophecy. Gaius Claudius Scaevola is required by Pallas Athene to do three things, one of which is to show that the Earth goes around the sun. I issued a challenge to readers: could they do it…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Inquisition. Galileo Galilei

1633年 - ガリレオ・ガリレイの異端審問の正式な尋問が始まる。

0 notes

Text

Universe Creation for Purpose – ASTROTECH HUB

Everything in the universe—stars, galaxies, planets, comets, etc.—has this in common. And the Universe is that. Many people have an interest in the worlds other than our own. Additionally, there is a lot that has yet to be discovered. This is what draws inquisitive minds. The planet, the universe, and everything else that is beyond of our reach were all created with a purpose. Exploring all of the behaviours that occur in the universe is incredibly fascinating, seen from the viewpoint of the innumerable academics and experts. There are also a lot of lessons that one may undoubtedly acquire from a location that they may not have previously considered. The effects of all cosmic events are what make knowledge of them important and will help to find out universe creation for purpose.

There must be a larger universe than just the Earth. And with the aid of astronomy, you can sort of investigate it all. One can simply immerse themselves in a thorough analysis of the universe's phenomena with the aid of the best astronomy website. All the characteristics of any cosmic event, which you may or may not have heard of, may be found in one location, including the analysis of solar system models and direct impacts. Astro Tech Hub is the best astronomy website if you fall into the category of people who find astronomy to be fascinating.

All of the learning have been verified by researchers and specialists. Not only may one discover the many aspects and universal rules, but one can also observe how these affect the human species as a whole. The universe must be explored, if not literally then certainly with the knowledge that our resources can give us about its unique traits and behaviours.

#The Journey of Life Creation#Theory of General Relativity#Universe Creation for Purpose#The Sidereal Day Statistics#The Geocentric Model#The Heliocentric Model#Earth Rotation Around axis#Best Astronomy Website#Solar system models#About solar system#The Facts of the Solar System#About earth gravity

0 notes

Note

Hi, i just learned about the scientific revolution in europe at school. Can you tell me why you dont think scientific revolutions exist? im curious!

So I feel like I have to lead with the fact that I'm kind of arguing two different points when I say scientific revolutions aren't really a thing

One is that I'm objecting to a specific, extremely foundational theory of scientific revolutions that was put forth by the philosopher Thomas Kuhn, which I think really misrepresents how science is actually practiced in the name of fitting things to a nice model. The other is that I think the fundamental problem with the idea is that it's too vague to effectively describe an actual process that happens.

It's certainly true that there are important advances in science that get referred to as "revolutions" that fundamentally changed their fields -- the shift from the Ptolemaic model of the Solar System to the Copernican one, Darwin's theory of evolution, etc. But there are historians of science (who I tend to agree with) that feel that terming these advances "revolutions" ignores the fact that science is an continuous, accretional process, and somewhat sensationalizes the process of scientific change in the name of celebrating particular scientists or theories over others.

Kuhn's model that he put forth in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (which is one of those books that itself stirred a great deal of activity in a number of fields) suggests science evolves via what he called "paradigm shifts," where new ideas become fundamentally incompatible with the old model or way of doing things, causing a total overturn in the way scientists see the world, and establishing a new paradigm -- which will eventually cave to another when it, too, ceases to function effectively as a model. This theory became extraordinarily popular when it was published, but it's somewhat telling who it's remained popular with. Economists, political scientists, and literary theorists still use Kuhn, but historians of science, in my experience at least, see his work as historically significant but incompatible with how history is actually studied.

Kuhn posits that between paradigm shifts there are periods of "normal science" where paradigms are unquestioned and anomalies in the current model are largely ignored, until they reach a critical mass and cause a scientific revolution. In reality though, there is often real discussion of those anomalies, and I think the scientific process is not nearly so content to ignore them as Kuhn thinks. Throughout history, we see people expressing a real discontent with unsolved mysteries the current scientific model fails to explain, and glossing over those simply because the individuals in question didn't manage to formulate breakthrough theories to "solve" those problems props up the somewhat infamous "great men" model of history of science, where we focus only on the most famous people in the field as significant instead of acknowledging that science is a social enterprise and no research happens in a vacuum!

Beyond disagreeing with Kuhn specifically though, I think the idea of scientific revolutions vastly simplifies how science evolves and changes, and is ultimately a really ahistorical way of thinking about shifts in thinking. Take the example of the shift from Ptolemaic, geocentric thought to the heliocentric Copernican model of the solar system. When does this supposed "revolution" in thought actually start, and when does it "end" by becoming firmly established? You could argue that the publication of Copernicus' De revolutionibus orbium coelestium in 1543 was the beginning of the shift in thinking -- but of course, then you have the problem of asking where Copernicus' ideas came from in the first place.

The "great men" model of history would suggest Copernicus was a uniquely talented individual who managed to suggest something no one else had ever put forth, but realistically, he was influenced by the scientists who came before him, just like anyone else. There were real objections to the Ptolemaic model during the medieval era! One of the most famous problems in medieval astronomy was the fact that assuming a geocentric model makes the behavior of the planets seem really weird to an observer on Earth, referred to as retrograde motion, which had to be solved with a complicated system of epicycles that people knew wasn't quite working, even if they weren't able to put together exactly why. There were even ancient Greek astronomers who suggested that the sun was at the center of the solar system, going all the way back to Aristarchus of Samos who lived from around 310-230 BCE!

Putting an end point to the Copernican revolution poses similar challenges. Some people opt to suggest that what Copernicus started, either Galileo or Newton finished (which in and of itself means the "revolution" lasted around 100-150 years), but are we defining the shift in terms of new theories, or the consensus of the scientific community? The latter is much harder to pinpoint, and in my opinion as an aspiring historian of science, also much more important. Again, science doesn't happen in a vacuum. Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton may be more famous than their peers, but that doesn't mean the rest of the Renaissance scientific community didn't matter.

Ultimately it's a matter of simple models like Kuhn's (or other definitions of scientific revolutions) being insufficient to explain the complexity of history. Both because science is a complex endeavor, and because it isn't independent from the rest of history. Sure, it's genuinely amazing to consider that Copernicus' De revolutionibus orbium coelestium and the anatomist Andreas Vesalius' similarly influential De humani corporis fabrica were published the same year, and it says something about the intellectual climate of the time. But does it say something about science only, or is it also worth remembering that the introduction of typographic printing a century prior drastically changed how scientists communicated and whose ideas stuck and were remembered? On a similar note, we credit Darwin with suggesting the theory of evolution (and I could write a similarly long response just on the many, many influences in geology and biology both that went into his formulation of said theory), but what does it say that Alfred Russel Wallace independently came up with the theory of natural selection around the same time? Is it sheer coincidence, or does it have more to do with conversations that were already happening in the scientific community both men belonged to that predated the publication of the Origin?

I think that the concept of scientific revolutions is an important part of the history of the history of science, and has its place when talking about how we conceive of certain periods of history. But I'm a skeptic of it being a particularly accurate model, largely on the grounds of objecting to the "great men" model of history and the idea that shifts in thinking can be boiled down to a few important names and dates.

There's a famous Isaac Newton quote (which, fittingly, did not originate with Newton himself, but can be traced back even further to several medieval thinkers) in which he states "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants." I would argue that science, as an endeavor, is far more like standing on the shoulder of several hundred thousand other people in a trenchcoat. This social element of research is exactly why it's so hard to pull apart any one particular revolution, even when fairly revolutionary theories change the direction of the research that's happening. Ideas belong to a long evolutionary chain, and even if it occasionally goes through periods of punctuated equilibrium, dividing that history into periods of revolution and stagnancy ignores the rich scientific tradition of the "in-between" periods, and the contributions of scientists who never became famous for their work.

#SORRY FOR WRITING A NOVEL#i hope this makes sense and that i am not too deep in the history of science theory to give a good explanation#a much shorter tl;dr answer would be that my stance towards scientific revolutions is more skepticism than total rejection#but hyperbole gets the job done a lot faster haha#getting to the point that i really should have a#history of science tag

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love the unique dynamic of jedtavius so much, but why does everyone usually pit Jed as the dumb one?Jedediah Strong Smith was an accomplished explorer with a decent education, who could fully read and write in a time when literacy wasnt always standard (he also learned some latin, fanfiction writers do with that what you will). Meanwhile, Octavius not only probably believes the earth is flat but genuinely believes that the sun revolves around the earth. It doesn't come into conversation much, so no one has corrected him. (Heliocentrism wasn't really accepted until the mid 1700s).

Not to say that Jed doesn't have his own historical misconceptions. The theory of evolution didn't really get off the ground until well into the 1800s, and the real Jedediah Smith died in 1831 (same year Charwin left on the HMS Beagle). So he probably initially thought Rexy was some kind of dragon monster.

It's weird the think about wat the early days of the museum were like before everyone figured what was really going on.

But imagine, Octavius makes some off handed comment about falling off the "edge of the earth"

Jed: what in the Sam hill are you talking about partner?🤨

Octavius *loves Jedediah dearly, but genuinely thinks that he's a sweet simple bafoon sometimes* because the world is flat my love. Don't be embarrassed for not knowing that😊

Eventually, this leads to a fight bad enough that they need Larry to intervene. From then on, once a week, Larry holds family meetings so the exhibits can ask questions about the outside world and update their knowledge.

#night at the museum#jed and octavius#jedediah smith#gaius octavius#larry daley#jedtavius#this post kinda got away from me#still a neat idea

212 notes

·

View notes

Note

came across a post by astriiformes (astriiformes(.)tumblr(.)com/post/742882591316803584/hi-i-just-learned-about-the-scientific-revolution) that objected to Kuhn's theory of scientific revolution on the basis that they felt it leant in to the "great men of history" model. I never understood it this way, but I haven't read the book—I thought it was more about explaining the lag between accumulation of evidence that goes against the current paradigm and full paradigm shift. thoughts?

kuhn's model of 'paradigm shifts' is certainly prone to inviting 'great man' explanations of scientific developments. i would even go further, and say that this is due to a fundamental issue in kuhn's methodology, which is a tendency toward idealist analysis that fails to consider material and sociological factors. astriiformes points out that these days, kuhn is more popular with economists and political scientists than with practicing historians of science; this is true and not a coincidence.

astriiformes also walks through a valuable line of objection to kuhn, which is that the scientists we tend to credit with having made singlehanded discoveries were in fact usually embedded in vibrant scientific communities and ongoing debates, and were influenced by their contemporaries as well as their intellectual forebears. this is all true. another critical angle to interrogate here, and one where the Great Man often pops up again, is in kuhn's version of how scientific ideas are actually adopted: in other words, how he considers a 'paradigm shift' to actually occur, even once we assume the idea in question has already been formulated. let me chuck a few case studies at you because it's easier than talking in generalities.

for much of the 20th century, the 'standard story' of galileo's trial and imprisonment was that, having dared to become a lone voice defending heliocentrism, he was made a martyr to truth by the church, which was threatened on theological grounds. however, in the last several decades historians of science have studied much more seriously the patronage networks of renaissance italy: the structure of funding and epistemological authority whereby a scientist like galileo secured money, university or court positions, and respect by gaining mutually beneficial relationships with various nobles and other wealthy people. galileo had defended heliocentrism prior to the church's crackdown on him and his work; so had certain other astronomers. although it's true the church had theological objections to what galileo was saying, they were pretty much forced to tolerate him as long as he had sufficient patronage protection: wealthy, powerful people using their social clout to defend him. but this fragile truce was shattered when galileo lost the support of certain of his patrons, particularly some jesuits, in the early 1630s and thus became a much more vulnerable target of church censorship. it was only at this point that the church placed him on trial and then eventually under house arrest, and forced to recant.

evolutionary ('transmutationist') ideas were not new by the time darwin published the 'origin' in 1859. most french biologists at this time supported some variant of transmutationist ideas, and even in britain, transmutation of species had long been hotly discussed in the edinburgh medical schools in particular. the challenge for the wealthier london gentleman-naturalist set was that transmutationism had previously been associated with radical, materialist, atheist politics (this was precisely what appealed for many in edinburgh), and although evolutionary ideas had circulated in the wider reading public, these had typically been carefully framed to remain compatible with dominant anglican morals (eg, robert chambers's 'vestiges' of 1844). so, why were charles darwin's ideas accepted where others had been suppressed, ignored, or mired in controversy? a few reasons: again, a strong patronage network and powerful social connections (familial and personal); also, darwin very consciously avoided talking about human descent in 1859 (he did not do so until 1871's 'descent of man', which remains less widely read to this day) and avoided open avowal of materialism or atheism in his published works. furthermore, despite what lay histories may suggest nowadays, darwin's ideas were not embraced immediately or uncritically. they circulated piecemeal, with the help of 'popularisers' like haeckel and th huxley whose teachings often varied pretty widely from what darwin actually said or thought. and, prior to the 'modern synthesis' unifying 'darwinian' evolution with mendelian genetics, one of the most common objections to darwin's ideas was that he had provided proof of no actual mechanism of heredity, which resulted in a retrospectively fascinating period of anglo and french scientific writing between about 1890–1940 that often circulated the claim that darwin had been proven embarrassingly wrong, and it was jean-baptiste lamarck who had instead been vindicated by the biologists of the middle victorian era.

louis pasteur has historically been credited with ushering out the last vestiges of 'miasmatic' and 'environmentalist' theories of disease in france, and replacing them with good solid bacteriology. this is simply a misrepresentation of scientific beliefs among the lay public, technical experts like public health officials, and even working scientists under the third republic. because hygienists and sanitation engineers had spent much of the 19th century creating professional prestige for themselves as managers of the insalubrious environmental factors plaguing particularly the urban poor, you can imagine they were not generally thrilled at the proposition that someone had actually confirmed the existence of a microscopic 'germ' of disease, a foreign entity that could be studied and eradicated by a laboratory scientist with entirely different credentials and training. so, as it became clear that the actual eradication part was still a challenge, and that disease risk did not strike all people or demographics equally, french hygienists by and large simply altered their rhetoric a little. yes, germs existed—in fact, clearly, these were what the hygienists had been protecting people from all along by encouraging cleaner air, open spaces, gymnastic exercise, &c! this is the root of what's now known in the historical literature as the 'sanitary-bacteriological synthesis'—not an overturning of an old 'environmentalist' paradigm for a modern bacteriological one, but rather a melding of the two that enfolded pasteur's and koch's discoveries whilst still shoring up the professional authority of the hygienists and sanitarians.

in all three of these cases you can see how a strictly kuhnian analysis of 'paradigm shifts' over-emphasises the role of the Great Man (here in his guise as Genius Scientist) because it overlooks critical factors like the social and professional networks that actually allow knowledge to spread, and the professional and pecuniary interests that motivate people, consciously or not, when they evaluate new theories or ideas. galileo did not suffer from 'failing' to spark a paradigm shift, any more than darwin singlehandedly succeeded; their ideas circulated, mutated, and provoked on the strength of relationships as much as pure cerebral Theory. pasteur's claims likely could not have achieved the renown they did, had they not been helped along by hygienists who saw in them a change to re-form and reinforce their own profession and authority.

kuhn's work was an important departure from earlier positivist, largely teleological histories of science: the 'paradigm shift' allowed people to talk about massive and notable changes in science without having to accede to a model that assumed constant, linear progress. in this sense, much of today's history of science (still a comparatively immature and evolving field!) belongs to a citational lineage that will eventually pop up with kuhn's name. but, methodologically, kuhn leaves a lot to be desired, because his analysis is generally founded in an intellectual history that configures Science as a world of disembodied ideas unburdened by social, material, and economic considerations and practices.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

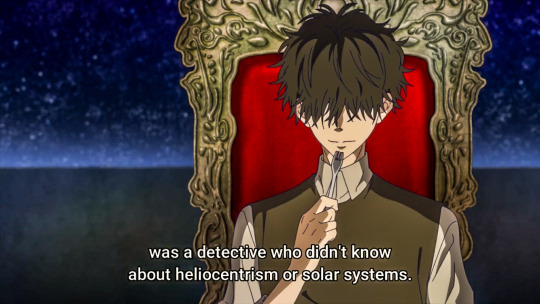

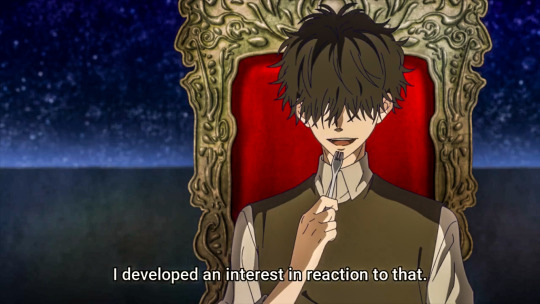

An ancestor of mine five generations ago was a detective who didn't know about heliocentrism or solar systems. I developed an interest in reaction to that.

—Ron Kamonohashi

Are you connecting the dots?

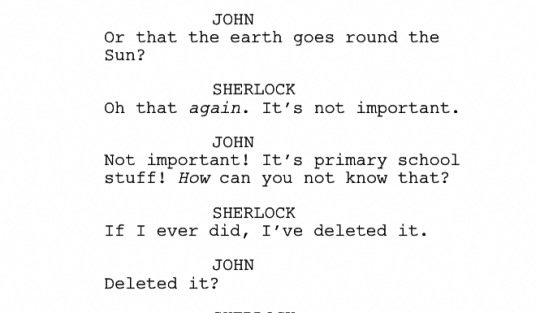

From Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “A Study in Scarlet”:

My surprise reached a climax, however, when I found incidentally that he was ignorant of the Copernican Theory and of the composition of the Solar System. That any civilized human being in this nineteenth century should not be aware that the earth travelled round the sun appeared to be to me such an extraordinary fact that I could hardly realize it.

…

‘But the Solar System!’ I protested.

‘What the deuce is it to me?’ he interrupted impatiently; ‘you say that we go round the sun. If we went round the moon it would not make a pennyworth of difference to me or to my work.’

From Sherlock BBC:

Sherlock BBC, The Great Game (final shooting script)

We are on the verge of uncovering Ron’s past including his ancestors.

Interesting that Akira Amano wants to change that.

(Tagging you again Andy and D @clouds-of-peach and @anitazara. Sorry I find this really hilarious)

#kamonohashi ron no kindan suiri#ron kamonohashi#totomaru isshiki#akira amano#episode 7#sir arthur conan doyle#sherlock holmes#john watson#sherlock bbc#rkdd anime#rkdd spoilers#deranged detective#ron kamonohashi’s forbidden deductions#the great game

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 to c. 170 CE) was an Alexandrian mathematician, astronomer, and geographer. His works survived antiquity and the Middle Ages intact, and his theories, particularly on a geocentric model of the universe with planets following orbits within orbits, were hugely influential until they were replaced by the heliocentric model of the universe proposed by Copernicus and Galileo.

Continue reading...

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two flashbacks I would love to see in S3 (apart from a third 1941 installment, obviously):

In a universe where canonically heaven and angels created the universe according to God's plan and didn't put the Earth at the centre of it, I'd love to see Crowley and Aziraphale's reactions to the first heliocentric theories or to Galileo's trial, particularly Aziraphale's reaction.

In a universe where canonically Adam and Eve existed I'd love to see Crowley and Aziraphale discuss about and/or with Darwin, particularly what Crowley thinks of his theories.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

i see rowen's heliocentric A and i raise miasma theory A

#giving dorotea an ulcer this man has NOT engaged with human bullshit for the last 900 years#idk if im keeping this in the chapter but ohhh does it tickle me#ramblings

17 notes

·

View notes