#saxon switzerland

Text

Hohnstein Castle in Saxon Switzerland by Ernst Ferdinand Oehme

#ernst ferdinand oehme#art#switzerland#hohnstein castle#castle#castles#landscape#architecture#architectural#romantic#romanticism#saxon#europe#european#swiss#saxon switzerland#burg hohnstein

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Martin Rak

Saxon Switzerland National Park, Saxony, Germany

#curators on tumblr#nature#landscape#travel#saxon switzerland#germany#europe#western europe#saxony#martin rak

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Breathtaking

A surreal evening on the rocks above the Elbe River in Saxon Switzerland, Germany

📸 Kilian Schonberger

Note: It's Saxon Switzerland, a region in Germany famous for it's rock towers. 500 miles from real Switzerland

#Kilian Schonberger#Breathtaking#Elbe River#Saxon Switzerland#Germany#Rainbow#Amazing#Beautiful#Nature#Travel#regenbogen#Landscape#saechsischeschweiz#elbsandsteingebirge#Landscape Photography

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saxon Switzerland National Park | By Andrea Trept / Impressum

1 note

·

View note

Text

Saxon Switzerland: Bastei 💚💚

An amazing rock formation consisting of sedimentary rocks (sandstone). It’s on the border between Germany and Czechia. Definitely worth visiting, although I wish there weren’t so many tourists and one had to pay for every single thing.

#kamaarts#saxony#Sächsische Schweiz#saxon Switzerland#Germany#Bastei#travel#travel photography#travel blog

0 notes

Text

Autumn Evening on the Rock in Saxon Switzerland by Alexandr Kolovratnik

#saxony#saxon#switzerland#autumn#fall colours#autumnal#autumnal colours#seasons#changing seasons#change of the seasons

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saxon Switzerland

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

howdy yall, I’m gonna be spending some time next month in northern Germany and would love to know of anyone’s recommendations for small towns to stop in or nice hiking, anywhere from Berlin/Dresden/Hamburg area

#already know about Saxon Switzerland which is sick#but yeah I need some trip pointers#going with a friend of mine i just like do not care about cities rn I wanna see SMALL TOWNS AND CHILL#personal#travel advice pls?#I’ve been before but I was in the south#and it was 12 years ago lmao

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

Saxon Switzerland par Rafael Wagner

Via Flickr :

Before I visited Saxon Switzerland, I wondered why Swiss artists were so fascinated by this landscape. Today after my visit I know the reason:). Saxony, Germany. Nikon D810 + Laowa 12 mm f/2.8 Zero-D

#Laowa 12mm f/2.8 Zero-D#Nikon#D810#Deutschland#Germany#Sachsen#Saxony#Saxon#Switzerland#Sächsische#Schweiz#Wald#Forest#Nebel#fog#morning#mood#Morgen#Stimmung#Steine#Stones#Rocks#Felsen#Herbst#autumn#Sonne#Sun#Sonnenlicht#Sonnenaufgang#sunrise

0 notes

Video

Postcrossing DE-11868131 by Gail Anderson

Via Flickr:

Postcard with a photo of a landscape in Saxon Switzerland. Sent by a Postcrossing member in Germany.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Clouds of fog in Saxon Switzerland (Carl Gustav Carus, 1828)

340 notes

·

View notes

Note

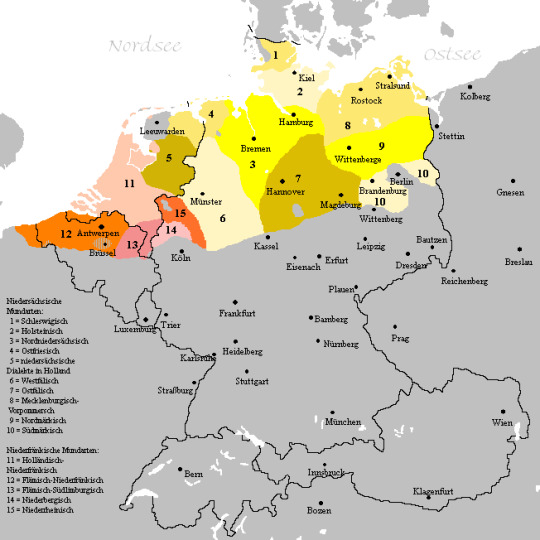

So I noticed something interesting linguistically during my Spanish lessons but then I couldn't find a reason why and thought maybe you would have an idea?

Why does the word 'German' change so much from language to language? I mean you said Deutsch but we say German. But then in Spanish, it's Alemán. That's a massive change across three language. And I know they're from different language families but it still seems like a big change, I wonder why

I mean...yeah, it's kind of a situation

The thing is, Germany was only united as a single country in 1871. Before that, it was really a conglomerate of many different small cities, dukedoms, and kingdoms under the Holy Roman Empire (and before that: Tribes)

Modern-day Germany was just beyond the edge of civilisation during ancient times - Everything to the west and South, including France and England, was conquered and named and cartographed by the Romans but Germania was what was on the "other side":

The beige part was where civilisation ended for the Romans. Everything beyond the Limes was barbarian woods and most attempts to conquer there ended in military disasters like the battle of the Teuteburger Forest so ...not much progress was being made.

The name "Germania", that was used for EVERYTHING beyond the Limes border was apparently adopted from the word the Gauls used for the peoples they knew were living right there on the other side - and which meant something like "people of the forest" or possibly "neighbours" (which means the Romans might have done that ancient thing where they asked the Gauls: "Who lives over there?" and the Gauls were "Oh, yeah, those guys are our neighbours who sometimes come to our markets and that we fight with sometimes and who talk a little weird" and the Romans were like: "Ah, so the name of everyone living in the great beyond is 'Neighbours' and just stamped that name on a large chunk of the continent full of people who had never met a Gaul and had never heard of the word "Germania")

And because that area wasn't centralised the way the former colonies of Rome were, this pattern continued - when "states" (there was no modern-day statehood then, I guess the closest word would be "Reiche" but that would be Empires in English but that also doesn't describe it accurately and Reich has a Connotation in English and kingdom suggests a kind of continuity that didn't exist yet...) interacted with the people who lived in these lands, they often falsely assumed a level of social cohesion that didn't exist. One example is when Charlemagne pushed East, he would often make deals with the pagan Saxon tribes to please stop raiding all the nice monasteries he tried to establish - but it happened again and again, and people at the time concluded that the Saxons simply didn't honour their word. The problem was, that the Saxons were not united under one ruler and were not one cohesive tribe - so just because one of them made a deal to stop raiding monasteries, this doesn't mean anyone else got the memo or felt obliged to stop plundering those monks.

Even today, this kind of happens: Like "teutonic" being used for "german" because Teutons were a German tribe or people identifying Germany with Bavaria bc they hear a lot about the Oktoberfest or "Prussian" and "German" being equated because between 1871 and 1918, the Hohenzollern, being both the royal House of Prussia and the Kaiserhaus, largely dictated Germany's foreign policy and impression to the rest of the world, and even before that posing the biggest counter-weight to the Austrian/Austro-Bavarian role on the German-speaking playing field and often symbolising the different cultures (e.g. protestant vs catholic) existing across the German-countries-minus-Switzerland.

And this is also how the name thing happened: "Deutsch" just means "of the people" and was largely used for the language (hence "Dutch", being a very similar language to German, also having that very similar name, except, since they were the "Low Countries" (flat as a pancake land) of the Holy Roman Empire, they eventually took that name for themselves and their language when they became independent - the Netherlands speaking nederlands, while Belgish dutch-speakers speak "vlaams" after the region "Flanders") But since Germany never "separated" from the Holy Roman Empire but is largely considered its successor, there was no reason to make a regional name the name for a new nation. It just remained "the nation/the people".

Over the centuries, the other countries usually took whatever name there was for the regional tribe of Deutsche/people they dealt with and applied that to the whole thing: If you dealt primarily with the Alemanni people, you would use a word like the French "Allemagne", the English lived on an island and mostly kept using the Latin name "Germania" - which became "Germany". In Finland and Estonia it's "Saksa" and "Saksamaa" because being in the East, they mostly dealt with Saxons.

This also turned into an international game of telephone eventually: People who didn't have much contact with different kinds of Europeans would just pick up whatever name the people they dealt with used for Germany. If you had a lot of contact with the French or Spanish, you would pick up a variation of "Alman", if you dealt primarily with the English or Italians, it would be a variety of "Germania"

Then you have countries like Japan, which entered international exchange very late and had a lot of contact with Dutch and German speakers - which is why they say ドイツ - "doitsu". In Mandarin it's "Déguó" - guó meaning "land" and "Dé" for Deutschland.

Then there is also the language barrier: The modern nation-states of Germany and Italy both were once part of the Holy Roman Empire and neither had a standardised language (even today, on the European continent, Germany and Italy might take the prize for the most variations of their own language on the home continent) or considered themselves "German" or "Italian" until very late. So they distinguished between the people who spoke all the variations of their own language and those people above/below the Alps who were absolutely incomprehensible to them due to speaking an entirely different language family - so the Italians also spoke of "tedesco", which is related to the word "deutsch". (Italy cleverly spared itself most of this chaos by not having a lot of neighbours to begin with).

Another language barrier issue was in the East, because that's where Germanic languages and Slavic languages meet. This meant that while everyone who was part of the German(ic) dialect family could communicate with their neighbouring towns and tribes and everyone on the Slavic side could communicate with their neighbouring towns and tribes, they were also faced with those weirdos from the other side of the language barrier who were speaking absolute gibberish (or maybe just stared at you like an idiot and said nothing when you asked them a basic question) That's why in many Slavic languages, the name for "Germany" is a variation of "Niemcy" or "Německo" - which means "mute" or "non-speaker" or "foreigner" - because those were the people they couldn't talk to. Vācija, Vokietija, and Vuoceja also work this way)

Meanwhile, in Germanic languages, it's often names that also incorporate the word "deutsch & land"- Duitsland, Tyskland, Deytshland, Däitschland, Þýskaland etc

(I think to do the language diversity and mutual communication argument some justice, I think it's also important to point out that there wasn't a lot of personal mobility for the average person at the time, so they probably also identified themselves by what little they saw of the world. If even today there are German-speakers that don't understand each other, that issue was bound to be amplified by 1000000 at a time with no standardised writing, no mobility, a thin population, small towns etc. So even if everyone between the furthest North-East of the Germanic language continuum and the lowest South-West could maybe somehow communicate with their respective neighbouring towns and tribes in pre-nation times, if you had snatched two peasants from the respective ends even of what is today Germany and sat them down on the table in the middle, there probably would have been to have even the most basic conversation or know that the other person spoke a variation of the same language - there is an old saying that "a language is a dialect with an army" - and for German, it's more "a dialect-continuum with a bunch of armies fighting each other until eventually, they got 1 army 2000 years late". Meanwhile for the educated, the lingua franca at the time was Latin.)

Now, a lot of countries ...well, eventually became countries. Which meant they could do some marketing of their own and establish their own name for themselves - but Germany, as I mentioned, was only united in 1871. Even if they considered their language "deutsch", they didn't consider themselves "deutsch" for a long time (and when they did, it was considered a radical idea) and as such, there was no centralised government saying "We are deutsch" the way the French kings said "We are French" or the English kings said "We are English" - in fact, the central authority until the early 19th century was the Holy Roman Empire. Their rulers considered themselves the successors of the old Roman Emperors - this was called the "translatio imperii" according to which Charlemagne was the first "new" Emperor" and the Empire continued until Franz II was forced to abdicate bc of Napoleon. Eventually, it was officially considered "Das heilige römische Reich deutscher Nation" - "the holy roman Empire of the german nation" - but that wasn't really a central aspect of anyone's identity.

The average person just identified by whatever colour their personal patch on this map was:

#InOurFlickenteppichEra

So no one really challenged to disagreed with someone speaking of them as "Saksa" or "German" and that's pretty much why everyone has a different name for Germany.

335 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elly Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari (Nelly’s) :: Dancers of Mary Wigman School in Saxon, Switzerland, 1922-1923. From the major exhibition "Nelly's" © Benaki Museum

#nelly's#mary wigman dance school#open air dance#mary wigman tanzschule#1920s#nellys#elli seraidari#elli souyioultzoglou seraïdari#Elly Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari#Elli Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari#Elli Sougioultzoglou Seraidari#dancer#dancers#danzatrici#tanzerinnen#bailarinas#danseuses#jump#mid air#suspended#midair#women artists#benaki museum

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

top five most humorless nations on earth:

1. Singapore: a cruel anglo-saxon experiment to create the most vapid metropolis possible

2. South Africa: self explanatory

3. Switzerland: a horrid orgy of western europe’s most austere bourgeois banging away at cuckoo clocks in their damp cave dwellings

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

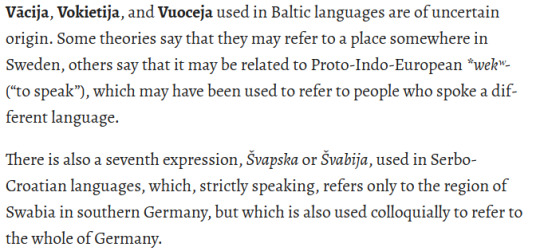

German dialects and varieties

German is spoken by around 155 million people and is the official language in six countries and one subdivision (South Tyrol in Italy), including Austria, Belgium, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and Switzerland.

There are three main dialect groups: Upper German (Oberdeutsch), Central German (Mitteldeutsch), and Low German (Plattdütsch). Upper and Central German form the High German (Hochdeutsch) subgroup [not to be confused with Standard High German (Standardhochdeutsch or simply Hochdeutsch as well)].

The descriptors “high/upper” and “low” refer to the dialects of the German states in the mountainous South and the flat North.

Standard German is pluricentric, with different national varieties, namely, German Standard German, Austrian Standard German, and Swiss Standard German (Schweizerdeutsch/Schwiizerdütsch). German Standard German is based mainly on the Upper Saxon and Eastphalian varieties.

The German dialects are the traditional local varieties and are traced back to the different Germanic tribes. Many of them are unintelligible to someone who only knows Standard German, since they often differ in lexicon, phonology, and syntax.

Dialects differ from each other by how much the so-called High German consonant shift affected them. This High German consonant shift took place between the 6th and 8th centuries and primarily affected the consonants [p], [t] and [k]:

In the consonant shift, [p] became [pf] or [f]. The word appel became Apfel, and the word schip was later pronounced Schiff.

The consonant [t] changed to [s] or [t͡s]. This is why even today, speakers in Northern Germany say dat, wat, and Water, like they did before the shift, while in the South they say das, was, and Wasser.

The [k]-sound changed to the fricative -ch- [x], so ik became ich and maken became machen.

The Low German spoken in the flat part of the country was largely unaffected by this shift. The dialects of higher regions, however, were affected to varying degrees.

Varieties refer to the different local varieties of Standard German. They differ only slightly in lexicon and phonology. In certain regions, they have replaced the traditional German dialects, especially Low German.

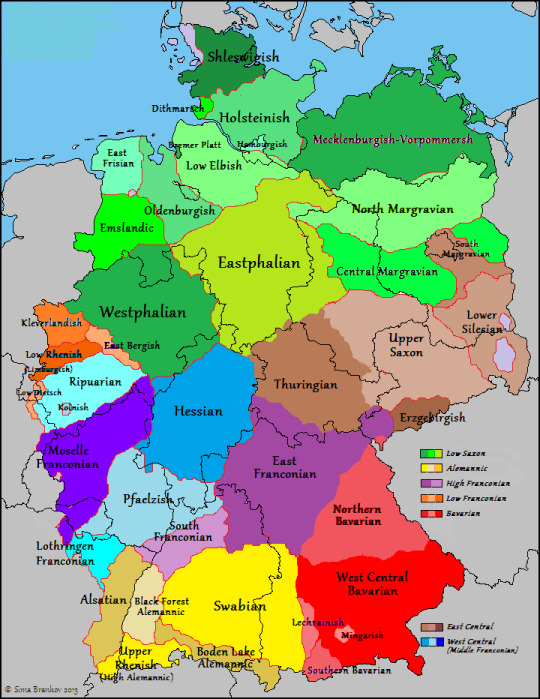

Upper German

Upper German (Oberdeutsch) is spoken in southern Germany, northern and central Switzerland, Austria, Liechtenstein, South Tyrol, and Alsace (France).

It is subdivided into the following groups: Upper Franconian (Oberfränkisch), Alemannic (Alemannisch), and Bavarian (Boarisch). Upper Franconian includes East Franconian (Ostfränkisch or Mainfränkisch; 1 in the map) and South Franconian (Südfränkisch; 2).

Alemannic comprises Swabian (Schwäbisch; 3), Low Alemannic (Niederalemannisch; 4), and High (Hochalemannisch) and Highest Alemannic (Höchstalemannisch; 5).

Bavarian includes Northern Bavarian (Nordboarisch; 6), Central Bavarian (Mittelbairisch; 7), and Southern Bavarian (Südbairisch; 8). It is one of the dialects that diverges the most from Standard German. Some of its features are the following:

Pronouncing -r- as an alveolar trill [r] (the “rolled r”, also found in Spanish)

Pronouncing -a- as -o-

Other vowel differences. For example, Bavarian is called Bairisch in Standard German and Boarisch in Bavarian German.

Vocabulary differences, such as I (pronounced [i]) instead of ich.

Here are some expressions in Upper German compared to Standard German:

Grüß Gott/Grüß dich/Servus — Hallo (Hello)

Pfiat eich — Tschüss (Goodbye)

Deesch mr abr arrg — Es tut mir Leid (I’m sorry)

Central German

Central German (Mitteldeutsch) is spoken in western and central Germany, southeastern Netherlands, eastern Belgium, Luxembourg, and northeastern France.

It is subdivided into the following groups: Central Franconian (Mittelfränkisch), Rhine Franconian (Rheinfränkisch), and East Central German (Ostmitteldeutsch). Central Franconian includes Ripuarian (Ripuarisch; 1), Moselle Franconian (Moselfränkisch; 2), and Luxembourgish (Lëtzebuergesch; 3).

Rhine Franconian comprises Hessian (Hessisch; 4), Palatinate (Pälzisch; 5), and Lorraine Franconian (Lottrìnger Plàtt; 6).

East Central German includes Thuringian (Thüringisch; 7), Upper Saxon (Obersächsisch; 8), Erzgebirgisch (Arzgebirgsch; 9), Lusatian-Silesian (Niederlausitzisch-Schläsisch; 10), and South Marchian (Südmärkisch; 11). Upper Saxon differs from Standard German in many of its vowel sounds. Its speakers pronounce Bühne (“stage”) as Biine, böse (“wicked”) as beese, and Schwester (“sister”) as Schwaster. The pronunciation of the letters -o- and -u- is also distinctive. To speakers of other German dialects, it sounds more like the Standard German -ö- and -ü-.

Here are some expressions in Central German (Colognian/Kölsch) compared to Standard German:

Jode Dach — Hallo (Hello)

Tschö — Tschüss (Goodbye)

Dat deit mir leid — Es tut mir Leid (I’m sorry)

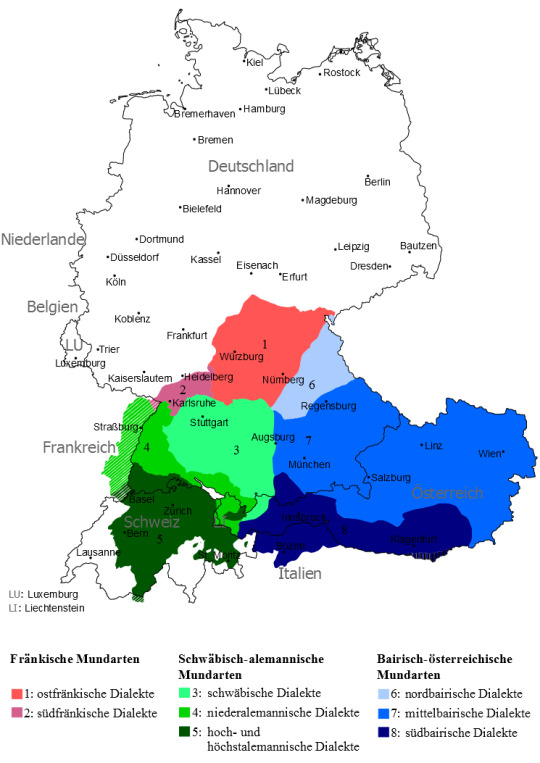

Low German

Low German (Plattdütsch) is spoken in northern and western Germany, eastern Netherlands, and southern Denmark. It is actually a language, not a dialect.

It is subdivided into the following groups: North Low Saxon (Nordniedersächsisch; 3), Westphalian (Westfälisch; 6), and East Low German (Ostniederdeutsch). North Low Saxon includes Holstenian (Hosteinisch; 2), Schleswigian (Schleswigsch; 1), Dithmarsch (Dithmarsisch; 2), North Hanoverian (Nordhannoversch; 7), Emslandish (Emsländisch; 6), Oldenburgish (Oldenburgisch; 3), and Gronings (Grönnegs; 4).

Westphalian comprises West Münsterlandian (Westmünsterländisch; 6), Münsterlandian (Münsterlandisch; 6), South Westphalian (Südwestfälisch; 6), East Westphalian (Ostwestfälisch; 6), Stellingwarfs (Stellingwarfs; 5), Drents (Drèents; 5), Tweants (Twents; 5), Gelderland-Overijssel (Gelderland-Overijssel; 5 and 11), Veluws (Veluws: 5), and Eastphalian (Ostfälisch; 7).

East Low German includes Brandenburgian (Brandenburgisch; 9 and 10), Mecklenburgian-Western Pomerian (Mecklenburgisch-Vorpommersch; 8), Central Pomerian (Mittelpommersch; 9), East Pomerian (Ostpommersch), Low Prussian (Niederpreußisch), and Mennonite Low German (Plautdietsch).

Low German is very close to Standard German in terms of pronunciation. The written forms of the two varieties are completely the same, but Low German often more closely resembles Dutch and English than Standard German. However, it is disappearing because fewer and fewer people speak it.

Here are some expressions in Low German compared to Standard German:

Moin — Hallo (Hello)

Tschüüs — Tschüss (Goodbye)

Dat deit mi Leed — Es tut mir Leid (I’m sorry)

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

Funny to me what different demonyms mean. "Saxon" originates from the seax/sax, a kind of knife/machete/sword (depending on size, though most were the size of a long dagger or a short sword) that was alternately used as a stabbing weapon in a shield wall (probably inspired by the Roman gladius?) and as a common tool, for cutting trees, slicing meat and bread, etc. While it does not directly indicate that the Saxons were/are a warlike people, it does indicate they were/are traditionally known for their long knives, which admittedly were often used in war. On the other side of the scale are the Hopi. Their name means the Peaceful People. No idle boast; they've been peaceful for many centuries, a lot longer than even Switzerland (and they haven't sold weapons like the Swiss have, either). And then, you have people whose names just mean "(The) People". Deutsch (German)? From "Theodisch". The People. Diné (Navajo)? "The People". So many "The People"s across the world. Humanity fascinates me.

47 notes

·

View notes