#residuals

Text

youtube

41K notes

·

View notes

Text

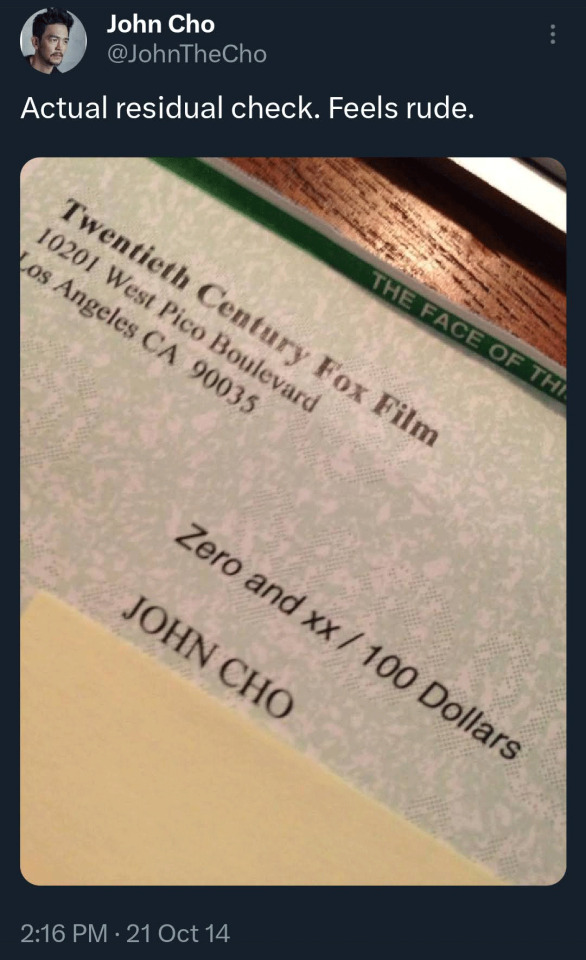

With the actors and writers strike in the U.S., I'm reminded of this tweet from John Cho who got zero payment from a residual check.

[x]

#john cho#the postage stamp costs more than the check#sag strike#writers strike#wga strike#sag-aftra#sagaftra#writers guild of america#sagaftra strike#actors#actors strike#residuals#the afterparty#star trek#harold & kumar#userspicy#tvarchive#cinemapix#cinematv#userbbelcher#chewieblog#usersnat#userksena#usermandie#usersophie#useraurore#hollywood#johncho

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

My 1 cent residuals dad on the picket line today :)) he says thanks for all the support!! WGA strong!!! 💪🪧📝

#gingerswagfreckles#wga strike#wga#wga strong#residuals#esp thanks to neil gaiman 😆❤️#do the write thing

432 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today I found out that the residuals from Quentin Tarantino’s guest role on the Golden Girls (he played an Elvis impersonator in an episode) helped him pay to make reservoir dogs.

Ok, but as someone who loves movie trivia, this one still blows my mind.

The Golden Girls, of all people, helped fund one of the most bloody, foul-mouthed and violent movies of the 90s. I should be shocked…

But it does makes a certain amount of sense.

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

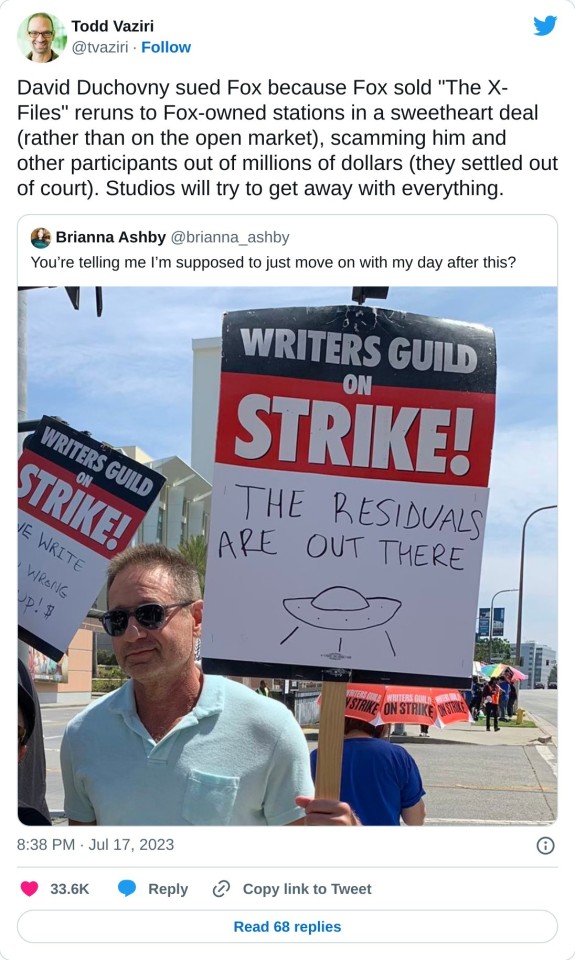

#twitter#tweet#tweets#David Duchovny#x-files#tv#1990s#fox corporation#residuals#wga solidarity#wga strike

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

In December, 2020, in the depths of pandemic winter, the actress Kimiko Glenn got a foreign-royalty statement in the mail from the screen actors’ union, SAG-AFTRA. Glenn is best known for playing the motormouthed, idealistic inmate Brook Soso on the women’s-prison series “Orange Is the New Black,” which ran from 2013 to 2019, on Netflix. The orchid-pink paper listed episodes of the show that she’d appeared on (“A Whole Other Hole,” “Trust No Bitch”) alongside tiny amounts of income (four cents, two cents) culled from overseas levies—a thin slice of pie from the show that had thrust her to prominence. “I was, like, Oh, my God, it’s just so sad,” Glenn recalled. With many television and movie sets shuttered, she was supporting herself with voice-over jobs, and she’d been messing around with TikTok. She posted a video in which she scans the statement—“I’m about to be so riiich!”—then reaches the grand total of $27.30 and shrieks, “WHAT?”

The post got more than four hundred thousand likes and nearly two thousand comments, many from disbelieving fans: “Wait how is that even legal??” “how is this even real you were on one of the biggest netflix shows.” This past May, with screenwriters on strike and labor unrest sweeping Hollywood, Glenn reposted the video on Instagram, where she has almost a million followers. This time, not only fans but castmates weighed in. Matt McGorry, who played a corrections officer: “Exaccctttlllyyy. I kept my day job the entire time I was on the show because it paid better than the mega-hit TV show we were on.” Beth Dover, who played a manager at the company taking over the prison: “It actually COST me money to be in season 3 and 4 since I was cast local hire and had to fly myself out, etc. But I was so excited for the opportunity to be on a show I loved so I took the hit. Its maddening.”

Television actors have traditionally had a base of income from residuals, which come from reruns and other forms of reuse of the shows in which they’ve appeared. At the highest end, residuals can yield a fortune; reportedly, the cast of “Friends” has each made tens of millions of dollars from syndication. But streaming has scrambled that model, endangering the ability of working actors to make a living. “So many of my friends who have nearly a million followers, who are doing billion-dollar franchises, don’t know how to make rent.”

Despite the Beatlemania-like fame, many cast members had to keep their day jobs for multiple seasons. They were waiting tables, bartending. DeLaria continued doing live gigs to keep up with her rent. Diane Guerrero, who played the fashionable inmate Maritza Ramos, worked at a bar, where patrons would recognize her.

These are just some highlights, but the entire article is worth a read, especially if someone you know is (or you are) so deep into watching celebrity culture that you’re having a hard time understanding why actors could possibly want more than they’re getting now.

#orange is the new black#netflix#streaming#actors#residuals#royalties#wga strike#sag-aftra strike#solidarity forever#hot union summer#summer of strikes

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

But why are are actors expecting to work for few years and be able to get residuals or money from that work for lifetime? Normal jobs don't work like that? We work for few years with an organization, get our salary, and when we leave our jobs we get nothing more from that company. I've never understood why actors expect to keep getting something for life? Am I missing something? I'm not from US so I don't know how the normal blue/white collar salary structure works there. I can understand if an actor is paid less for a job and they want to be paid more for that specific time/contract. But to keep on making money from one time job for life? I just don't get it.

You sound like a studio executive back in the 1950s. Back then, actors didn't make anything beyond what they made during production. The main argument for residuals is studios are re-selling the same product over and over again for years, decades even. If you made one unique lemonade that was so good that your boss keeps selling and re-selling your one lemonade for years and pocketing the profit, wouldn't you feel you should get a cut of the profit too?

Ronald Reagan was the SAG President back in the 1950s and he was able to negotiate residuals for TV actors, but movie studios executives said a hard no. Why? Because television was killing the movie industry. Today studios are complaining that less people are going to movie theaters since Covid. Same thing was happening in the 1950s, theater attendance fell by 65% thanks to television.

Studio executives told Reagan, "Why should any employee be paid more than once for the same job?". So Reagan had to up the ante and authorized the actor strike of 1960. After 5 weeks of high-stake contentious showdown with studio executives, they finally agreed on residual systems for all films produced from 1960 and onward, and retroactive residuals for most but not all films pre-1960, meaning Reagan would not be getting residuals for some of his early films.

Since 1960, about $8 billion in residuals have been paid out to actors and their heirs and supported the middle class for the next 50 years. And, thanks to Reagan and the strike he engineered, working actors are also eligible for both health insurance and a pension. This is one of the reasons why I always had a soft spot for President Reagan (for non-American readers, Reagan went on to become U.S President in the 1980s and was one of the most popular President in history).

"I've never understood why actors expect to keep getting something for life?"

The short answer is actors are paid 60% of their salary during the first few years of the show, banking on they will be paid the rest after 4 years when the show is syndicated, and if they're lucky they'll make 60% more than their previous salary. So if you were only paid 60% of your salary for the first 3 or 4 years of your job, you bet you would want to be paid the rest through residuals that will push your salary over 100%. And if your show is a hit, your pay raise will go though the roof.

Actors outside of the U.S system are usually paid upfront. A few European actors during the '90s and '00s tried to convince their colleagues to convert to the residual systems, but most actors couldn't conceive the idea for waiting for the rest of their salary a few years down the line even if they can reap far larger fiscal benefits.

However you may think of the residual system, for 50 years it supported the middle class in Hollywood. The middle class is what prevents a country from de-evolving into a third world country. Now Hollywood has become a third world country with just the rich and the working class, like a less fun version of Veronica Mar's life in the town of Neptune.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I believe my first residual check was $7000 when it was on network, then the last one I got was $74.

When you negotiate with Hulu, Netflix, [and other streaming services], they will say we're giving you bonus points up front. So you say, "What are those points based on: engagements, subscriptions, views? What are they based on?" And they say, "We won't tell you that, and we won't negotiate points either."

Writers on RESIDUALS: THEN VS. NOW

– @/moreperfectunion on TikTok

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digital and animation archival work is getting more and more important as companies stop producing dvds and start DRM protecting and paywalling streaming.

Already we’re seeing shows taken down to not pay creators residuals, Disney stopping dvd distribution in Australia after GOTG3, and other screenshare issues esp with Crunchyroll (and teleparty making it premium sharing only, a bonus fee ON TOP of subbing to the site just so you can have guests for free)

The internet wasn’t meant to have every action of creating and connecting monetized and I’m SO TIRED of the clownery 🤡

#archive art initiative#preserved archived accessible#amethyst rambles#animation#residuals#hot strike summer#late stage capitalism#digital media#physical media

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"cost-saving"

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know Lola, Chris, & Gavin probably receive more in residuals from narrating the books than they do from starring in the show.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Jump to Streaming - Was It Worth It?

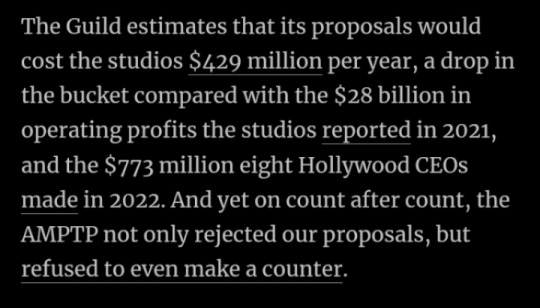

I’ve been watching and covering the streaming wars for a few years now, and looking at the current state of it, along with the pandemic and the ongoing WGA and SAG-AFTRA strike exposing how broken the industry is, it’s left me thinking this: was the jump and transition to streaming worth in the end? Because at this point, it sucks for everyone involved: the studios, the creatives, and the consumers.

Studios who decided to hop in the game and compete with Netflix by creating their own streaming services have found out that streaming isn’t profitable (or at the very least, it’s nowhere near as profitable as the box office, physical media, VOD, and linear TV) because the revenue generated is almost entirely based on subscriptions. Putting out a show or a movie on a streaming service is practically putting it out for free since those individual titles aren’t generating profit as they would on the aforementioned release avenues. Streamers just have to hope that the release of a show or film on their platform drives enough sign-ups to break even and generate profit. And as a result, studios lose millions, if not billions on their services.

The creatives (specifically the writers and actors striking right now) behind shows and movies made for streamers are getting little to no residuals from them. Writer Kyra Jones shared that the first residual check she got from writing on the ABC show Queens was $12,000. The first residual check she got from writing on the Hulu show Woke was $4. Writer Cody Ziglar’s episode of She-Hulk netted him just $396 in residuals, despite the episode (the one where Daredevil returns) being one the most watched episodes of one of the most watched series on Disney+. Kimiko Glenn, who played Soso on Orange Is the New Black, mentioned that many of the actors on the show still worked second jobs because they weren’t being paid enough to sustain themselves. For shows licensed to streamers, it’s essentially the same. Gilmore Girls, which ran on The WB in the 2000s, has been one of the most popular shows on Netflix since they started streaming it. Sean Gunn, who played Kirk Gleason on the show, said in an interview that he’s seen almost no money from licensing fee Netflix pays Warner Bros. to stream the show.

And for the consumer, the convenience of it has been diluted. In the early days of streaming, it was just Netflix and Hulu, and between the two services, they had pretty much everything you’d need to drop cable. Now there are too many streaming services, and with all the price hikes that occurred in the last few years, just subscribing to a few of the major ones costs the same, if not more, than cable at this point. Not to mention streamers have made it so that we can’t get attached to any original they produce. A streamer puts out a show that’s not an instant hit that you, me, and everyone we know watched, it gets prematurely canceled (Hey remember when Netflix use to save canceled shows? Oh how the tables have turned). And thanks to a certain studio introducing this precedent, prematurely canceled streaming shows now get yanked off the service, written off in taxes, thrown into the abyss, and then banished to the Shadow Realm. And since streaming media rarely get physical releases, they’re to stay in the Shadow Realm, never to be seen again.

As much as it doesn’t feel like it is now, and I think it’s safe to say it’s done more harm than good at this point, streaming is still ultimately the future. There’s no turning back from it unless every service goes under and shuts down. And even if that were to happen, I’m not sure if those who cut the cord are going to want to buy a new one. And as a strong proponent for physical media, nothing would make me happier than to see everyone start buying DVDs and Blu-Rays again and video stores making a comeback - but that’s likely not going to happen either.

I don’t know what the future holds for streaming. Truth be told, I don’t think it will ever be as profitable as physical media, VOD, or linear TV. But that isn’t going to stop from studios from trying to make streaming as profitable as the days of physical media, VOD, and linear TV. I won’t pretend to have the answers here, but it ain’t hard to tell that the current streaming model is unsustainable. Trying to cut costs by replacing writers and actors with AI won’t make streaming more profitable. Continuing to prematurely cancel new shows when they’re not instant smash hits and not giving them the chance to find an audience as well as having streaming services full of one-season shows won’t make it more profitable either.

Streaming may still be the future, but it clearly shouldn’t be relied upon as the primary means of media distribution. Perhaps studios should let films sit on VOD and physical media for longer than they currently do before dropping them on a streaming service. I remember growing up, a new film wouldn’t make it to TV until several months to a year later. And speaking of TV, linear TV may be dying, but it’s a slow death and for the studios who still have broadcast channels, it’s still a way to reach people and get sign-ups. In November of last year, Disney aired the first two episodes of Andor across ABC, FX, and Freeform. Earlier this year, they did this again by airing the pilot episode of The Mandalorian across the networks. And this fall they’re about to do it again with Ms. Marvel (although this is likely more as a result of the fact that they’ll be nothing on TV this fall).

But do you know what could ultimately help? By paying the actors and writers the residuals they deserve, not automating their jobs away, and giving them opportunities and tools to create more new and exciting films and shows, and in the case of television, not prematurely canceling them when they’re not hits straight off the bat and allow them to find audiences.

What do y’all think? Let me know and keep supporting the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strike. Solidarity forever.

#streaming#WGA#WGA Strike#sag-aftra#sag#sag strike#writers strike#actors strike#workers solidarity#Solidarity Forever#residuals#current events#was it worth it?#i stand with the wga#wga solidarity#essay#in this essay i will

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the office#david denman#residuals#residual pay#netflix shows#netflix#streamers#wga solidarity#wga#support the wga#wga strike#wga strong#sag strike

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stone's indictment of the majors focuses on two types of crimes, which, to use his terms, might be divided into Thievery and Thuggery, although there seems to be some overlap. In the Thievery category is the formula the studios use to apportion the vast new millions that come from the videocassette market. The dastardly formula which perpetrates the thievery, Stone says, is called the "videocassette override."

"Major, major thievery," he says. "It's $12 million on [my film] Wall Street."

Twelve million dollars is a large sum to have been lost to "theft," even by Hollywood standards. I ask him how he calculated that.

"The majors declare that only 20 percent of a film's videocassette revenues are allocated back to the film's gross."

"I thought gross was gross," I say, relieved to have seen Speed-the-Plow.

Gross isn't gross when it comes to tape revenues because of the override formula, he says. "They keep 80 percent," which means that profit participants on the creative end—like the director and screenwriter, who start collecting only if the gross is massive—can end up shut out of the tape-revenue windfall. "They say they're treating videocassettes as a separate entity. It's been going on for years, but it's a complete misunderstanding of the way that videocassettes were originally supposed to be distributed. Wall Street's video revenues were more than $16 million in sales. They will allocate around $4 million. Ripping off $12 million." (Nick Counter, president of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, calls this account "confused." He says that "the formula is an industrywide negotiated figure which is the minimum and can be negotiated higher. The economics of the marketplace—marketing costs and the like— have justified the formula.")

Stone calls the other category of crime committed by the cocksucker vampires at the major studios Thuggery: using monopolistic muscle to strangle the once promising growth of nonmajor independents and boutique studios such as Hemdale (which brought out Salvador and Platoon when no one else would). "It's an incredible struggle that's going on," he says. "It's very subtle. Critics don't pick up on it. In 1985-86, the independent films started to break through. The Salvadors, the Room with a Views, the Platoons."

He contends the majors reacted to this by increasing the quantity of the films they release, which resulted in the independents' being squeezed out, because they're locked out of distribution to movie theaters. "Hemdale, Cannon, Dino [De Laurentiis], all of them have been hurting. They're hurting because they can't get the theater time." (In fact, a recent Variety story confirmed a "screen crunch'' for indies, although collusion is another question.)

-Oliver Stone to Vanity Fair, January 1989 [x]

Commenting on the ongoing 11-week WGA strike, Stone suggested the roots of the current industrial action lie in the deal brokered to end the five-month writers strike in 1988.

“There was a basic miscarriage of justice way back when, when Brian Walton was the head of the WGA, when we gave in. I wasn’t on the front line, but I supported that strike,” said Stone.

“We gave in to the producers. They got away with murder on one of these deals where all that DVD money was deferred. They claimed they were in the hole, in the red, and that they had to get their money back from DVD.

“I forgot what the percentage was, but they took something like the first 75% off the top. The DVD business was huge, especially for my films. So, the gross was never divided fairly.”

Stone said this trend had continued with residuals and profits.

“Not so much residuals, as profits really. Residuals are important for some of the writers who don’t make as much money. But people who do make money, they don’t touch the profits from the film, the studio does,” he said.

“The studio is always telling you that they’re losing money, but they always find a way to make a new level of profit for 10, 15 years. … It’s that perpetual industrial problem with a capitalist group that pays its executives more and more money and screws the average writer.”

-Oliver Stone to Deadline, Jul 14 2023

#oliver stone#vanity fair#sag aftra strike#sag strike#wga strike#writers strike#then and now#residuals#profits

2 notes

·

View notes