#old german folk tale

Text

youtube

FAUN feat. Fatma Turgut - Umay (Official Video)

#that's the new song I just had in my spotify ads. very appreciated#i love this band#they basically bring old historical songs folk tales melodies lyrics and poems back to live#whenever i get the chance to see them live i do#faun#fatima turgut#german band#turkish singer#pagan folk#music#historical music

3 notes

·

View notes

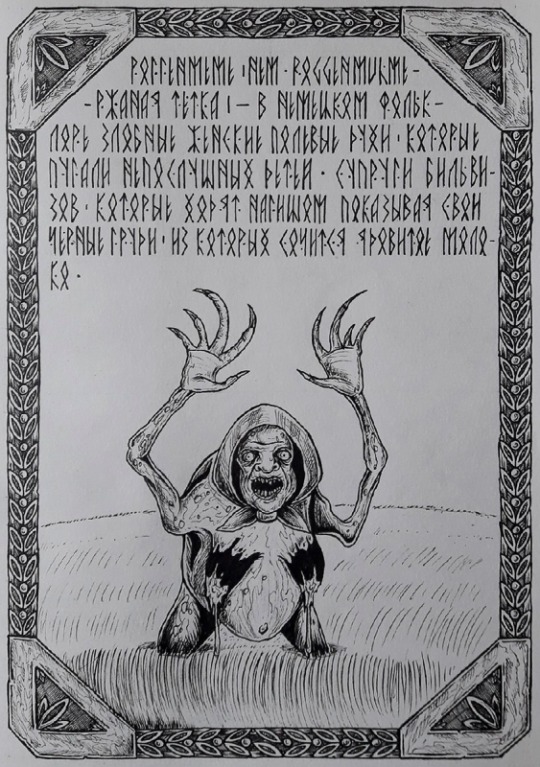

Text

Frau Gauden

In the German region of the Prignitz, Frau Gauden (Mrs. Gauden) is the leader of the Wild Hunt. She leads this army of supernatural hunters together with her 24 dog-shaped daughters.

The Wild Hunt, also known as the Wild Army or the Wild Ride, is the German name for a folk tale widespread in many parts of Europe, particularly in the north, which usually refers to a group of supernatural hunters who hunt across the sky. The sighting of the Wild Hunt has different consequences depending on the region. On the one hand, it is considered a harbinger of disasters such as wars, droughts or illnesses, but it may also refer to the death of anyone who witnesses it. There are also versions in which witnesses become part of the hunt or the souls of sleeping people are dragged along to take part in the hunt. The term “Wild Hunt” was coined based on Jacob Grimm’s German Mythology (1835).

The phenomenon, which has significantly different regional manifestations, is known in Scandinavia as Odensjakt (“Odin's Hunt”), Oskorei, Aaskereia or Åsgårdsrei (“the Asgardian Train”, “Journey to Asgard”) and is closely linked to the Yule season here. The reference to Wotin/Odin in the name Wüetisheer (with numerous variations) is also clear in the Alemannic and Swabian dialects; In the Alps, people also speak of the Ridge Train. In England the train is called the Wild Hunt, in France it is called Mesnie Hellequin, Fantastic Hunt, Hunt in the Air, or Wild Hunt. Even in the French-speaking part of Canada, the Wild Hunt is known under the term Chasse-galerie. In Italian, the phenomenon is referred to as caccia selvaggia or caccia morta.

The Wild Army or the Wild Hunt takes to the skies particularly in the period between Christmas and Epiphany (the Rough Nights), but Carnival, Corporal Lent and even Good Friday also appear as dates.

Christian dates have superseded the pagan dates, which see the Wild Hunt moving, especially during the Rough Nights. This period of time is assumed to be originally between the winter solstice, i.e. December 21st and, twelve nights later, January 2nd. In European customs, however, since Roman antiquity, people have usually counted from December 25th (Christmas) to January 6th (High New Year).

The ghostly procession races through the air with a terrible clatter of screams, hoots, howls, wails, groans and moans. But sometimes a lovely music can be heard, which is usually taken as a good omen; otherwise the Wild Hunt announces bad times.

Men, women and children take part in the procession, mostly those who have met a premature, violent or unfortunate death. The train consists of the souls of people who died “before their time”, that is, caused by circumstances that occurred before natural death in old age. Legend has it that people who look at the train are pulled along and then have to move along for years until they are freed. Animals, especially horses and dogs, also come along.

In general, the Wild Hunt is not hostile to humans, but it is advisable to prostrate yourself or lock yourself in the house and pray. Whoever provokes or mocks the army will inevitably suffer harm, and whoever deliberately looks out of the window, gaping at the army will have his head swell so much that he cannot pull it back into the house.

The first written records of the Wild Hunt come from early medieval times, when pagan traditions were still alive. In 1091, a Normannic priest named Gauchelin wrote about the phenomenon, describing a giant man with a club leading warriors, priests, women and dwarfs, among them deseased acquaintances. Later references appear throughout the High and Late Middle Ages.

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is an old copy-paste moving around the internet regarding discussions asserting the inherent Slavicness of The Witcher, and I will record it here for posterity.

(translated from polish)

-write eight books

-have their main character suffer from otherness, prejudice and erroneous stereotypes

-insert anti-racist references at every turn

-make dwarves into Jews

-and use to criticise anti-Semitism

-criticise nationalist attitudes

-criticise xeno- and homophobia at every turn

-show support for a multicultural society and acceptance of otherness

-describe how victims become executioners

-show how violence begets violence

-make it the central theme of the last three volumes

-have the hero and his lover die during a racist pogrom

-defend the persecuted to the lastHear from every corner of the internet that "a black witcher would be a disaster."

-write thirteen stories

-based three on Andersen's fairy tales

-three more on the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm

-seventh on an Arabian fairy tale

-mock folklore and folk beliefs in the first one

-but also make fun of them in the story "The Edge of the World"

-mock the Polish legend in "The Limits of Possibility"

-name the main character "Żerard" (Jerald)

-generally use mainly names with Celtic roots like Yenefer or Crach

-and those derived from Romance languages such as Cirilla, Falka or Fringilla or Triss

-a few English names such as Merigold

-and those derived from other Germanic languages such as Geralt

-and Italian

-German

-and even French

-borrow monsters from American games, especially from Advanced Dungeons and Dragons

-from Irish, make an elf language

-and from German, make it the language of dwarves

-make the characters celebrate Irish folk holidays

-write an article about where you got your inspiration from

-pour bile on Slavic fantasy in it

-finally write an eighth book

-make one of the key characters a Japanese demoness

Become a champion of turbo-slavism.

/s

#the witcher#the witcher 3#the witcher books#nobody contests The Witcher is the product of the time-place-history and culture experienced by its author#what very much ought to be contested are attempts at painting TW as symbolic of an ideology it very much criticizes#aside ethnonationalism criticism applies to imperialism likewise. not like eastern europe has extensive experience with both or anything#as goes for creative and intellectual inspiration it would be trite to reduce it to the local circle only (and inaccurate)#Sienkiewicz or no Sienkiewicz#at some point the audience must simply read more to know more. helpfully AS has provided a plethora of references + an entire other trilogy#9/10 when you see a discussion about the inherent Slavicness of The Witcher it's thanks to CDPR's excellent marketing strategy#which is a shame

121 notes

·

View notes

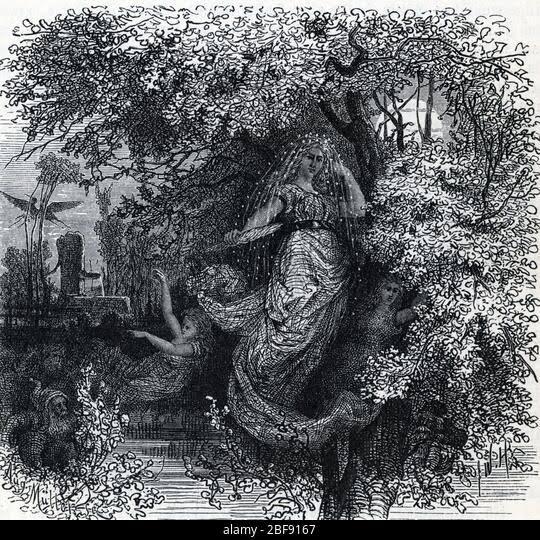

Photo

Old German Folk Tale - Hermann Hendrich

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Njuggel [Shetland/Scottish folktales]

The Scottish Kelpie is one of the most popular and well-known water spirits. An unsuspecting victim comes upon a malicious creature that poses as an innocent horse. Enticed to ride it, the victim soon finds himself magically unable to dismount and can only scream as the horse plunges beneath the waves to drown its meal. The story certainly speaks to the imagination, but there are actually many variants of it: The Norwegian Nøkk, the German Nixe, the Welsh Ceffyl Dŵr, the Flemish Nikker, the Icelandic Nykur and many others are all variations of the same creature.

This relation can also be seen in their etymology: most of these names are similar, because they are thought to be derived from an old Germanic term for washing (as in, bathing something in a river, like the horse monsters do with their victims in the stories).

But I’m digressing. One of the most obscure variations of the tale comes from the Shetland Islands. Here, people told stories about the monstrous Njuggel (also called Njogel, Njuggle and in northern Shetland ‘Shoopiltee’ or ‘Sjupilti’). Like its relatives, this creature is an aquatic horse, usually depicted as a horse with fins. It also has a wheel for a tail (or a tail shaped like the rim of a wheel, depending on who you ask), but most modern interpretations drop that detail. Its hooves are backwards.

It lives near waterways and lakes and pretends to be a peaceful horse, taking care to hide its strange tail between its legs. Though it usually takes the form of a particularly beautiful horse, sometimes it is an old, thin horse. When a traveller finds the Njuggel, the creature influences them and convinces them to mount it. When the victim climbs into the saddle however, the creature runs away to the nearest lake to drown its prey. It runs at an extremely high speed, keeping its wheel-tail in the air. After accelerating to a high speed, its hooves burst in flames and its nostrils emit smoke or fire.

The victim cannot dismount, but if they can speak the monster’s name out loud, the Njuggel loses its powers and the victim can escape. What happens then varies between stories: sometimes the creature slows down and can be dismounted, and sometimes he vanishes into thin air.

Sometimes, you can see them at night: such sightings usually involve a white or grey horse emerging from water and run some distance before disappearing in a flash of light.

The Njuggel is not entirely the same creature as the Kelpie and the Ceffyl Dŵr. It has a connection with watermills and demands offerings such as flour and grain. If these gifts cease, it will halt the wheel of its mill. To avoid having to offer grain to this creature, people would light fires when a Njuggel appeared, for they are afraid of flames (usually peat was burned, although throwing a torch also did the trick). There is a story in Tingwall about a group of young men who tried to capture a Njuggel for themselves. They succeeded in chaining the creature but couldn’t hold it for long, and the Njuggel broke free and fled. But the standing stone to which it was chained is still there between the Asta and Tingwall lochs, and the marks that were supposedly made by the chain can still be seen.

Sources:

Lecouteux, C., 2016, Encyclopedia of Norse and Germanic Folklore, Mythology, and Magic.

Marwick, E., 2020, The Folklore of Orkney and Shetland, Birlinn Ltd, 216 pp.

Teit, J. A., 1918, Water-beings in Shetlandic Folk-Lore, as Remembered by Shetlanders in British Columbia, The Journal of American Folklore, 31(120), p.180-201.

(image source: Davy Cooper. Illustration for ‘Folklore from Whalsay and Shetland’ by John Stewart)

#Scottish mythology#Shetland mythology#water horse#aquatic creatures#monsters#mythical creatures#mythology

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 10 Most Anticipated TTRPGs For 2024!

EN World's annual vote on the most anticipated titles of the coming year, and yes, some games have appeared on this list in previous years.

10 Tales of the Valiant (Kobold Press)

1st appearance

Kobold Press joins the 'alternate 5E' club with this rewritten, non-OGL version of the game! A million dollar Kickstarter last year, and a new one for the GM's book going on right now, Kobold Press announced this as 'Project Black Flag' during the OGL crisis of 2023, but being unable to trademark that name opted for Tales of the Valiant instead. The system, however, is still called the Black Flag Roleplaying System.

9. Mothership 1E (Tuesday Night Games)

3rd appearance

On this list three years running, the boxed Mothership 1E game should be coming out this year! This is sci-fi horror at its best -- you can play scientists, teamsters, androids, and marines using the d100 'Panic Engine'. Yep, it's Alien(s), pretty much.

8. Monty Python's Cocurricular Mediaeval Reenactment Program (Exalted Funeral)

2nd Appearance

Exalted Funeral made quite a splash when they announced this game last year, which went on to make neary $2M on Kickstarter. And how could they not? It's Monty Python fergoodnessake! A rules-lite gaming system, spam, a minigame with catapults, spam, coconut dice rollers, spam, and an irrepressible Python-eque sense of humour. Did I mention the spam? It was at #10 on this list last year, but it's claimed to #8 this year.

7. Daggerheart (Darrington Press)

1st appearance

From the Critical Role folks, Daggerheart is a new fantasy TTRPG with its own original system coming out this year with "A fresh take on fantasy RPGs, designed for long-term campaign play and rich character progression."

6. Cohors Cthulhu (Modiphius)

1st appearance

It's Ancient Rome. It's Cthulhu. It uses Modiphius' in-house 2d20 System. You can be a gladiator, a centurion, or a Germanic hero. Did I mention Cthulhu?

5. Dolmenwood (Necrotic Gnome)

1st appearance

The British Isles, a ton of folklore, and a giant Kickstarter--Dolmenwood is a dark, whimsical fantasy TTRPG drawing from fairy tales and lets you "journey through tangled woods and mossy bowers, forage for magical mushrooms and herbs, discover rune-carved standing stones and hidden fairy roads, venture into fungal grottoes and forsaken ruins, battle oozing monstrosities, haggle with goblin merchants, and drink tea with fairies."

4. Pendragon 6E (Chaosium)

4th appearance

Last year's winner was on this list waaaaay back in 425 AD, and it's still here! Well, maybe not that far back, but it's shown up in 2021 at #4, 2022 at #3, 2023 at #1, and now 2024 at #4! What can we say? People are clearly anticipating it... still.

3. 13th Age 2nd Edition (Pelgrane Press)

2nd appearance

13th Age is over a decade old now, and was our most anticipated game way back in 2013. Now the new edition is coming! It's compatible with the original, but revised and with a ton more... stuff! 13th Age 2E was #3 in last year's list!

2. The Electric State Roleplaying Game (Free League)

1st appearance

Free League is always on these lists, and for good reason. This gorgeous looking game is described as "A road trip on the verge of reality in visual artist and author Simon Stålenhag's vision of an apocalyptic alternate 1990s".

1. Shadow of the Weird Wizard (Schwalb Entertainment)

3rd appearance

First announced by Rob Schwalb a couple of years ago, this is a more family-friendly version of his acclaimed RPG, Shadow of the Demon Lord. SHADOW OF THE WEIRD WIZARD is a fantasy roleplaying game in which you and your friends assume the roles of characters who explore the borderlands and make them safe for the refugees escaping the doom that has befallen the old country. Unsafe are these lands: the Weird Wizard released monsters to roam the countryside, cruel faeries haunt the shadows, undead drag themselves free from their tombs, and old, ancient evils stir once more. If the displaced people would rebuild their lives, they need heroes to protect them. Finally at the top of the list after being #7 in 2022, and #6 in 2023!

#RPG#Tales of the Valiant#Mothership#Monty Python#Daggerheart#Cohors Cthulhu#Dolmenwood#Pendragon#13th Age#The Electric State#Shadow of the Weird Wizard

27 notes

·

View notes

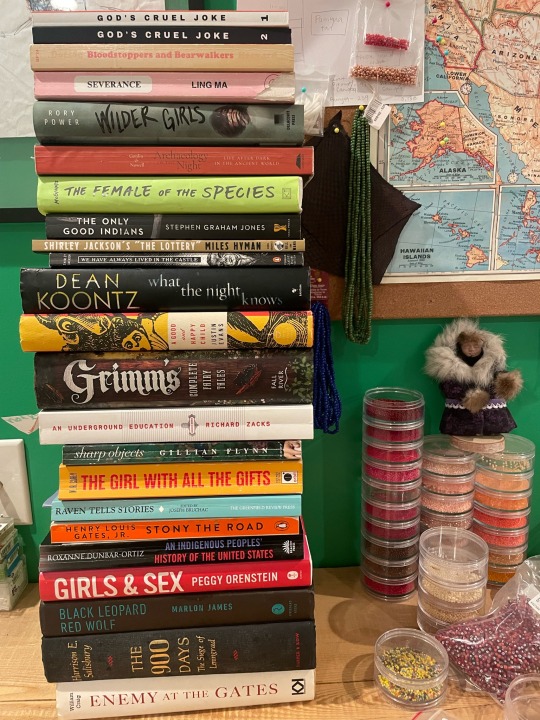

Note

Hello! I'm really curious, what books/authors would you recommend to someone who's new to writing horror?

Hi! Here is what I have on hand (minus my loaned out copies of my favorite book ever Mongrels by Stephen Graham Jones and Never Whistle At Night: an indigenous anthology of dark fiction which made me cry on an airplane and made the person next to me very uncomfortable, like she was just trying to build a cart at banana republic, apologies to seat 17B)

God’s Cruel Joke Lit Mag because I’m in them and will be in issue 4, too :) published either mid-January or February 2024– @labyrinthphanlivingafacade is in issue 3 with a great short story that I won’t spoil ***right now the magazines are available to purchase in physical copies but I was told all issues will be free to download as pdfs pretty soon!

Severance by Ling Ma (body horror but not in the way you think, the real horror is repetition and loneliness)

Wilder Girls by Rory Power (body horror)

The Female of the Species by Mindy McGinnis (adjacent the horror genre but a hell of a read)

ANYTHING BY STEPHAN GRAHAM JONES ANYTHING

We Have Always Lived in a Castle by Shirely Jackson (I read this for the first time last spring boy howdy, I also included The Lottery for its suspense)

Dean Koontz because my husband suggested it for the list— this was just the first title I grabbed, I think he said Patrician Crowell too but I was busy looking for Mongrels

A Good and Happy Child by Justin Evans (I didn’t finish this because depression set in shortly after I started but the first chapter plays with second pov which I really liked, I’m determined to read it this year)

Sharp Objects by Gillian Flynn (I really enjoyed HBO’s adaptation)

The Girl With All The Gifts by M.R. Carey (likely the only zombie stories that made me weep uncontrollably)

Girls & Sex by Peggy Orenstein (non-fiction: explores modern young women navigating sexuality and because I have a thing for loss of autonomy— it’s been a few years since I read it but there is discussion of sexual assault, but I appreciate the expanse of her research and even included a conversation with someone who is asexual)

Black Leopard Red Wolf by Marlon James (got a chill just typing this out— the audio book is exquisite)

You’ll notice some nonfiction because, as a historian undergrad, nothing scares me more than man. The battles of Leningrad and Stalingrad are particularly stomach churning. America’s Reconstruction Era is full of acted out malice and under taught in my opinion.

An Indigenous People’s History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

The 900 Days, The Siege of Leningrad by Harrison E. Salisbury

Enemy at the Gates by William Craig

(On the other side of WW2 I have a book of the experiences of German solider’s left over from a paper I wrote on the inadequacy of Nazi uniforms and how it expedited their failure in Russia, Frontsoldaten by Stephen G. Fritz)

Stony the Road by Henry Louis Gates, Jr (one of my favorite authors, try finding “How Reconstruction Still Shapes American Racism” Time Magazine, April 2, 2019, I used it as a source for a paper on the history of voting rights)

Bloodstoppers and Bearwalkers— folk tales of Canadians, Lumberjacks & Indians by Richard M. Dorson (published around 1952 but content collected from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in the 40’s)

Raven Tells Stories: An Anthology of Alaskan Native Writing (I’m Alutiiq and the museum on Kodiak has a lot of stories recorded under Alutiiq Museum Podcast— my kids and I listen on Spotify)

I think the genre of horror is really mastering tension and playing on peoples fears which is why I included old school folk stories (An Underground Education had a great write up on the Grimm Brothers and the original fairy tales from around the world such as the Chinese and Egyptian Cinderella, as well as several different sections of funny tales, torture techniques, absolute weirdos etc etc) in this vein of thought The Uses of Enchanment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales by Bruno Bettelheim could prove to be useful

If you’re writing a character with Bad Parents— Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents and Toxic Parents (it has a longer subtitle but I don’t see my copy anywhere) might be able to help you shape character traits

I reached out to @littleredwritingcat who has a mind plentiful in sources who recommended

The Gathering Dark: an anthology of folk horror (I will be picking this one up asap)

Toll by Cherie Priest (southern gothic)

Anything by Jennifer MacMahon

The Elementals by Michael McDowell

#book recommendations#answered#is that my ask box tag? I never get them and forget everytime lmao#I feel like I should have prefaced this with how I’m just dipping my toes into horror myself#so I’d love to hear what other people are reading too!!!!

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ségurant, the Knight of the Dragon (1/4)

In order to do my posts about Ségurant, I will basically blatantly plagiarize the documentary I recently saw - especially since it will be removed at the end of next January. If you don't remember from my previous post, it is an Arte documentary that you can watch in French here. There's also a German version somewhere.

The documentary is organized very simply, by a superposition of research-exploration-explanation segments with semi-animated retellings of extracts of the lost roman.

0: The origin of it all

The documentary is led by and focused on the man behind the rediscovery of Ségurant, the Knight of the Dragon – Emanuele Arioli, presented simply as a researcher in the medieval domain, expert of the Arthurian romances, and deeply passionate by the Arthurian legend and chivalry. If you want to be more precise, a quick glimpse at his Wikipedia pages reveals that he is actually a Franco-Italian an archivist-paleographer, a doctor in medieval studies, and a master of conferences in the domain of medieval language and medieval literature.

It all began when Arioli was visiting the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, at Paris. There he checked a yet unstudied 15th century manuscript of “Les prophéties de Merlin”. Everybody knows Monmouth’s Prophetiae Merlini, but it is not this one – rather it is one of those many “Merlin’s Prophecies” that were written throughout the Middle-Ages, collecting various “political prophecies” interwoven with stories taken out of the legends of king Arthur and the Round Table. And while consulting this specific 15th century “Prophéties de Merlin”, Arioli stumbled upon a beautiful enluminure (I think English folks say “illumination”) of a knight facing a dragon. Interested, he read the story that went with it… And discovered the tale of Ségurant, a knight he had never heard about during the entirety of his studies.

Here we have the first fragment of Ségurant’s story: “Ségurant le Brun” (Ségurant the Brown, as in Brown-haired, you could call him Ségurant the Dark-haired, Ségurant the Brunet), a “most excellent and brave knight”, sent a servant to Camelot, court of king Arthur, and in front of the king the servant said – “A knight from a foreign land sends me there, and asks you to go in three days onto the plain of Winchester, with your knights of the Round Table, to joust. You will see there the greatest marvel you ever saw.”

Checking the rest of the manuscript, Arioli found several other episodes detailing Ségurant’s adventures, all beginning with illuminations of a knight facing a dragon. And this was the beginning of Arioli’s quest to reconstruct a roman that had been forgotten and ignored by everybody – a quest that took him ten years (and in the documentary he doesn’t hide that he ended up feeling himself a lot within Ségurant’s character who is also locked in an impossible quest).

I: Birth of king, birth of myth

The first quarter of the documentary or so is focused on Arioli’s first step in his quest for Ségurant: Great-Britain of course! However, slight spoiler alert, Arioli didn’t find anything there – and so the documentary spends a bit more time speaking about king Arthur than Ségurant, though it does fill in with various other extracts of Ségurant’s story.

Arioli’s first step was of course the National Library of Wales, where the most ancient resources about king Arthur are kept, and where old Celtic languages and traditions are still very much alive, or at least perfectly preserved. The documentary has Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan presenting the audience with the oldest record of the name Arthur in Welsh literature – if not in European literature as a whole. The “Y Gododdin”, where one of the characters described is explicitly compared to Arthur in negative, “even though he was not Arthur”. The Y Gododdin is extremely hard to date, though it is very likely it was written in the 7th century – and all in all, it proves that Arthur was known of Welsh folks at the time, probably throughout oral poems sung by bards, and already existed as a “good warrior” or “ideal leader” figure.

From there, we jump to a brief history lesson. Great-Britain used to be the province of the Roman Empire known as Britannia – and when the Romans left, it became the land of the Britons (in French we call them “Bretons” which is quite ironic because “Breton” is also the name of the inhabitants of the Britany region of France – Bretagne. This is why Great-Britain is called Great-Britain, the Britany of France was the “Little-Britain”, and this is also why the Britain-myth of Arthur spreads itself across both England and France – but anyway). However, ever since the 5th century, Great-Britain had fallen into social and political instability, as two Germanic tribes had invaded the lands: the Angles and the Saxons. In the year 600, the Angles and the Saxons were occupying two-thirds of Great-Britain, while the Britons had been pushed towards the most hostile lands – Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. This era was a harsh, cruel and dark world, something that the Y Gododdin perfectly translates – and thus it makes sense that the figure of Arthur would appear in such situation, as the mythical hero of the Briton resistance against the Anglo-Saxons.

However we had to wait until a Latin work of the 12th century for Arthur’s fate to finally be tied to the history of the kings of England: Geoffrey of Monmouth, a Welsh bishop, wrote for the king of England of the time the “Historia Regum Britanniae”, “History of the Kings of Britain”, in which we find the first complete biography of Arthur as a king – twenty pages or so about “the most noble king of the Britons”. Geoffrey’s record was a mix of real and imagination, weaving together fictional tales with historical resources – it seems Geoffrey tried to make Arthur “more real” by including him into the actual History with a big H, and it is thanks to him that we have the legend of Arthur as we know it today ; even though his Arthur was a “proto-Arthur”, without any knight or Round Table. The tale begins in Cornwall, at Tintagel, where Arthur was conceived: one night, Uther Pendragon, with the help of Merlin, took the shape of the Duke of Cornwall to enter in his castle and sleep with his wife Igraine. This was how Arthur was born.

The documentary then has some presentations of the archeological work on Tintagel – filled with enigmatic and mysterious ruins. The current archeological research, and a scientific project in 2018, allowed for the discovery of proof that the area was occupied as early as 410, and then all the way to the 9th and 10th century, maybe even the years 1000. There are many elements indicating that Tintagel was inhabited during the post-Roman times when Arthur was supposed to have lived: post-Roman glass, and various fragments of pottery coming from Greece or Turkey and other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea – overall the area clearly was heavily influenced by Mediterranean commerce and cultures. Couple that with the fact that we have the ruins of more than a hundred buildings built solidly with the stone of the island – that is to say more buildings than what London used to have during the same era – and with the fact that there are scribe-performed inscriptions for various families and third parties (meaning people were important or rich enough to buy a scribe to write things for them)… All of this proves that Tintagel was important, wealthy and connected, and so while it does not prove Arthur did exist, it proves that a royal court might have existed at Tintagel – and that Geoffrey of Monmouth probably selected Tintagel as the place of birth of Arthur because he precisely knew of how ancient and famous the area was, through a long oral tradition.

2: After birth, death

The next area visited by the documentary is Glastonbury. “On a Somerset hill formerly surrounded by swamps and bogs”, medieval tradition used to localize the fabulous island of Avalon – where Arthur, mortally wounded by his son Mordred, was taken by fairies. Healed there, he ever since rests under the hill, and will, the story says, return in the future to save the Britons when they need it the most… More interestingly fifty years after Monmouth’s writings, the actual grave of king Arthur was supposedly discovered in the cemetery of the abbey of Glastonbury, and can still be visited today. It is said that in 1191, the monks of the abbey were digging a large pit in their cemetery, 12 feet deep, when they find a rough wooden coffin with a great lead cross on which were written “Here lies king Arthur, on the island of Avalon”. Now, you might wonder, why were monks digging a pit in their cemetery? Sounds suspicious… Well it is said that Henry II was the one who told the monks that, if they dug in their cemetery, they might find “something interesting”… Why would Henry II order a research for the grave of king Arthur? Very simple – a political move. Henry II was a Plantagenet king, aka part of a Norman bloodline, from Normandy, and the House of Plantagenet had gained control of their territory through wars. The Plantagenet was a dynasty that won large chunks of territory through battles (or through marriage – Henri II married Aliénor d’Aquitaine in 1152, which allowed him to extend his empire so that it ended up covering not just all of Great-Britain but also three quarters of France). But as a result, the Plantagenet House had to actually “justify” themselves, prove their legitimacy – prove that they were not just ruling because they were conquerers that had beaten or seduced everybody. They needed to tie themselves to Briton traditions, to link themselves to the legends of Britain – and the “discovery” of king Arthur’s tomb was part of this political plan. And it was a huge success – Glastonbury became famous, and so did king Arthur, who went from a mere Briton war-chief that maybe existed, to a true legend and symbol of English royalty.

However, so far, there are no traces of Ségurant in the Welsh tradition, and here we get our second extract of Ségurant’s roman, which actually seems to be the beginning of his adventures.

Ségurant comes from a fictional island (or at least going by a fictional name): l’île Non-Sachante. There Ségurant le Brun was knighted on the day of the Pentecost by his own grandfather. There was great merriment and great joy, and after the party, Ségurant openly declared he wanted to see the court of king Arthur and all the great wonders in it that everybody kept talking about. He claimed he would go to Winchester – and thus it leads to the invitation mentioned above. Yep, he decided that the best way to go see king Arthur’s court and his wonders was to basically challenge the king and his knights…

3: No place at the Round Table

Of course, the next step of the documentary is Winchester, former capital of Saxon England. Some traditions claim that it was at Winchester that Camelot was located, king Arthur’s castle and the capital of his Royaume de Logres, Kingdom of Logres. Logres itself being actually clearly the dream of a land rebuilt and given back to the Britons, once all the Germanic invaders are kicked out.

The documentary goes to Winchester Castle, built by William the Conqueror, and takes a look at the famous “Round Table” kept within its Great Hall – a table on which are written the name of 24 Arthurian knights, with a painting of king Arthur at the center… Above the rose of the Tudors. Because, that’s the thing everybody knows – while the Round Table itself was built in the 13th century and presented as an “Arthurian relic”, it was repainted in the shape it is today during the 16th century, by Henry the Eight (you know, the wife-killer), who used it as yet another political tool to impose and legitimize the rule of the Tudor line – and he wasn’t subtle about it, since he had Arthur’s face painted to look like his… On this table you find the names of many of the famous Arthurian knights: Galahad, Lancelot of the Lake, Gawain, Perceval, Lionel, Mordred, Tristan, the Knight with the Ill-Fitting Coat… They were organized according to a hierarchy (despite the very principle of the table being there was no hierarchy): at the top are the most famous and well-known knights, with their own stories and quests, such as Galahad, Lancelot of Gawain. At the bottom are the less famous ones: Lucan, Palamedes, Lamorak, Bors de Ganis…

And Ségurant is, of course, absent. Which can be baffling when you consider what the story about Ségurant actually says…

NEW EXTRACT! We are on the field of Winchester. All the tents are prepared for the greatest tournament Logres ever knew. The tent of Ségurant is very easy to spot, because there is a precious stone at the top, that shines day and knight, constantly emitting light as if it was a flaming torch. In front of king Arthur, all the bravest and most courageous knights of the Round Table appear and joust between them: Lancelot and Gawain are explicitly named. Suddenly, Ségurant appears and defies them all in combat! One by one, the knights of the Round Table battle with Ségurant – but all their spears break themselves onto his shield, and in the end, no knight wants to defy him, realizing they could not possibly defeat him. And in the audience, a rumor start spreading… “For sure, it will be him, the knight who will find the Holy Grail!”

So we have a knight who managed to defeat all the knights of the Round Table, in front of king Arthur, and yet nobody talks about him? But as the documentary reminds the audience – the Winchester Round Table only contains knights that the British tradition is familiar with. There many Arthurian knights with their own story and quests, such as Erec or Yvain the Knight of the Lion, who are absent from it… Because they are part of the French tradition, and thus less popular if not frankly ignored by England (a specific mention goes to Erec who was only translated very recently into English apparently, and for centuries and centuries stayed unknown in the English-speaking world).

Anyway – the conclusion of this first part of the documentary is simple. Ségurant is not from Great-Britain, he is not British nor Welsh, and so his origins lie somewhere else.

ADDENDUM

In the first part of this documentary, they stay quite vague and allusive about the story of Ségurant (because the documentary is obviously about the quest and research behind the reconstruction of the roman, not about what the roman contains in every little details). So to flesh out a bit the various extracts above I will use some information from the very summary Wikipedia page about this recently rediscovered knight (I didn’t had the time to get my hands on the book yet).

In the version that is the “main” one reconstructed by Arioli and that is the basis for the documentary’s retelling, soon before being knighted, Ségurant had proved his worth by performing a successful “lion hunt” onto the Ile Non-Sachante. Said island is actually said to have originally been a wild and deserted island onto which his grand-father, Galehaut le Brun, and his grand-father’s brother, Hector le Brun, had arrived after a shipwreck – they had taken the sea to flee an usurper on the throne of Logres named Vertiger (it seems to be a variation of Vortigern?). Galehaut le Brun had a son, Hector le Jeune (Hector the Young), Ségurant’s father. However, unlike the documentary which presents Ségurant as immediately wishing to see Camelot and defy its knights as soon as he is knighted, the Wikipedia page explains there is apparently a missing episode between the two events: in the roman, Ségurant originally leave the Ile Non-Sachante to defeat his uncle (also named Galehaut, like his grandfather) on the mainland. After beating his uncle at jousting, rumors of his various feats and exploits reached Camelot, and it was king Arthur himself who decided to organize a tournament in Ségurant’s honor at Winchester, so that the Knights of the Round Table could admire Ségurant’s exploits.

The fact that the documentary presents a version of the story when the Knights of the Round Table are already in search for the Holy Grail when Ségurant arrives at Winchester is quite interesting because according to the Wikipedia article, Ségurant’s name is mentioned in a separate text (a late 15th century armorial) as one of the knights of the Round Table who was present “when they took the vow of undergoing the quest of the Holy Grail, on Pentecost Day”. The same armorial then goes on to add more elements about Ségurant’s character. Here, instead of being the son of “Hector the Young”, he is son of “Hector le Brun” (so the whole family is “Brown” then), and this title is explained by the color of his hair, which is actually of a brown so dark it is almost black. Ségurant is described here as a very tall man, “almost a giant”, and to answer this enormous height, he has an incredible and powerful strength, coupled with a great appetite making him eat like ten people. But he is actually a peaceful, gentle soul, as well as a lone wolf not very social. He also is said to have a beautiful face, and to be “well-proportioned” in body. A final element of this armorial, which is the most interesting when compared to the main story given by the documentary (where the dragon comes afterward) – in this armorial, Ségurant is actually said to have killed a dragon BEFORE being knighted, a “hideous and terrible” dragon, and this is why his coast of arms depict a black dragon with a green tongue over a gold background.

Again, this all comes from an armorial kept at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal – which has a small biography and drawing of Ségurant over one page (used to illustrate the French Wikipedia article). It is apparently not in the “roman” that Arioli reconstructed – especially since in the comic book adaptation, and the children-illustrated-novel adaptations, not only is Ségurant depicted as of regular size, but he is also BLOND out of all things…

As for the name of the island Ségurant comes from, “l’île Non-Sachante”, it is quite a strange name that means “The Island Not-Knowing”, “The Unknowing island”, “The island that does not know”. This is quite interesting because, on one side it seems to evoke how this is an island not known by regular folks – this wild, uncharted, unmapped island on which Ségurant’s family ended up, and from which this mysterious all-powerful knight comes from (and you’ll see that the fact nobody knows Ségurant’s island is very important). But there is also the fact that the adjective “Sachante” is clearly at the female form, to match the female word “île”, “island”, meaning it is the island that does not “know”. And given it is supposed to be this wild place without civilization, it seems to evoke how the island doesn’t know of the rest of the world, or doesn’t know of humanity. (Again I am not sure, I haven’t got the book yet, I am just making basic theories and hypothetic reading based on the info I found)

#ségurant#segurant#the knight of the dragon#le chevalier au dragon#arthurian myth#arthuriana#arthurian literature#arthurian legend#king arthur#arthurian romance

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I love days when I get an excuse to post music hre, and I hope you enjoy the third helping, the tale bhind the song is a cracker too......

Johnny Ramensky, the Scottish safe cracker was born on April 6th 1905 in Glenboig, Lanarkshire.

His father was a Lithuanian immigrant miner who died when Johnny was young and the young Ramensky also became a miner. It was while he was down the pit that he learned his skills with dynamite which were to prove so useful to him in later years.

Johnny drifted in and out of trouble from the age of eleven and moved to the Gorbals area of Glasgow during the Depression with his mother and two sisters. He developed an amazing physical strength and acrobatic ability but in order to obtain some money, he became a burglar, specializing in robberies involving climbing up external rone-pipes to gain entry to premises. He also developed skills in picking locks and safe-cracking with explosives.

He won the nickname Gentle Johnny because he never used violence. And he escaped from prison several times, even staging a rooftop protest at Barlinnie in 1931. Johnny was what you would call now a career criminal, his life of crime saw him spend an estimated 40 years in prison, which was only punctuated by his extraordinary service during the Second World War.

When the war started he wanted to contribute something. He went to the governor of Peterhead Prison, where he was being held at the time, and asked for help to join the forces after he got out. The governor recognised he was something special and that he could be extremely helpful to our secret services. He served his full sentence and was collected by MI5 agents at the gate.

Ramensky was known for his athleticism and aced basic military training before he was parachuted behind enemy lines in Nazi-occupied Europe. One early success was at the Italian port city La Spezia.

Johnny was able to hide himself in the mountains and used a compass to direct RAF bombers to the harbour. He was also a smashing saboteur and blew up a lot of railway lines. And after the Germans fled Rome, Johnny was able to recover a huge volume of secret documents from locked safes, which were very helpful in the conclusion of the war.

Ramensky also spent time in North Africa and almost had the opportunity to kill Nazi military commander Erwin Rommel. He broke into Rommel’s headquarters and unfortunately Rommel was on the front line. Had Rommel been there the course of the war would have changed because he would have been prepared to kill him. Of course, he did also break into Rommel’s safe and got plans that were helpful.

Mr.Ramensky’s wartime exploits formed the basis of the 1958 film ‘The Safecracker’, starring Mr.Ray Milland.

After the war Johnny went back to his old ways, even jumping off the train to blow open a safe on the way back to Glasgow hours after he was demobbed. . He went to blow a safe at a bank in York because his criminal contacts tipped him off. He has been described as an adrenaline addict. He seemed to like danger.

When he got back to Glasgow he became a folk hero because people had heard about his exploits in the army. Various people offered him employment, including one of the big demolition companies. But that wasn’t exciting enough for him.

Even in his declining years when his physicality began to leave him he still couldn’t settle down. He tried to be a bookie but lost all of his own money, because he was a gambler. He never really went straight.

Ramensky died aged 67 in 1972 while a prisoner in Perth. He kept diaries which were burned by prison authorities, but one early extract survived.

It read: “Each man has an ambition and I have fulfilled mine long ago. I cherish my career as a safe blower. In childhood days my feet were planted in the crooked path and took firm root. To each one of us is allotted a niche and I have found mine. Strangely enough, I am happy. For me the die is cast and there is no turning back.”

There has been talk a fmovie about Johnny being made, but it is still to happen.

There’s a 7 minute film bout Johnny with the author of his biography, Robert Jeffrey, who I sourced most of the info for this post, and retired Glesga polisman, Les Brown, who tells of his dealings with Gentle Johnny. The Roddy McMillan song is playing throughout the clip.

That’s not the end of Johnny Gently though, he lives on at Peterhead Prison, now a museum where Ramensky served so many years behind bars, has created a exhibition space which highlights different aspects of his career.

You can get his biography by Robert Jeffrey for only £3.39, kindle version and £5.56 hardback at Amazon, I have also seen it on Ebay uk delivered for as low as £2.11

Let Ramensky Go.

There was a lad in Glesga town, Ramensky was his name

Johnny didnae know it then but he was set for fame

Now Johnny was a gentle lad, there was only one thing wrong

He had an itch to strike it rich and trouble came along

He did a wee bit job or two, he blew them open wide

But they caught him and they tried him and they bunged him right inside

Alley-ee alley-ay alley-oo alley-oh

Open up your prison gates

And let Ramensky go

And when they let him out he said he’d do his best but then

He yielded tae temptation and they bunged him in again

Now Johnny made the headlines, entertained the boys below

When he climbed up tae the prison roof and gave a one-man show

Alley-ee alley-ay alley-oo alley-oh

Open up your prison gates

And let Ramensky go

But when the war was raging the brass-hats had a plan

Tae purloin some information, but they couldnae find a man

So they nobbled John in prison, asked if he would take a chance

Then they dropped him in a parachute beyond the coast of France

Alley-ee alley-ay alley-oo alley-oh

Open up your prison gates

And let Ramensky go

Then Johnny was a hero, they shook him by the hand

For stealing secret documents frae the German High Command

So Johnny was rewarded for the job he did sae well

They granted him a pardon frae the prison and the cell

Alley-ee alley-ay alley-oo alley-oh

Open up your prison gates

And let Ramensky go

But Johnny was in error when he tried his hand once more

For they caught him at a blastin’, and it wasnae worth the score

The jury pled for mercy, but the judge’s voice was heard

Ten years without remission, and that’s my final word

Ten years, my lord, that’s far too long, wee Johnny cried in vain

For if you send me up for ten I’ll never come out again

Oh give me another chance, my lord, I’m tellin’ you no lie

But if you send me up for ten I’ll sicken and I’ll die

Alley-ee alley-ay alley-oo alley-oh

Open up your prison gates

And let Ramensky go

Now Peterhead’s a fortress, its walls are thick and stout

But it couldnae hold wee Johnny when he felt like walking out

Five times he took a powder, he left them in a fix

And every day they sweat and pray in case he makes it six

Alley-ee alley-ay alley-oo alley-oh

Open up your prison gates

And let Ramensky go

Alley-ee alley-ay alley-oo alley-oh

Open up your prison gates

And let Ramensky go

Alley-ee alley-ay alley-oo alley-oh

Open up your prison gates

And let Ramensky go………

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

theres a german folk tale about swarms of birds flying in a formation that looks like the face of an old man. hes supposed to be a personification of spring and i guess its implied that he controls the birds and ok u can stop now i lied btw i was distracting u while my friend escaped. and i forgot to tell u that ur the prison warden

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE LEGEND OF SLEEPY HOLLOW

@themousefromfantasyland @tamisdava2 @the-blue-fairie @grimoireoffolkloreandfairytales @thealmightyemprex @minimumheadroom @professorlehnsherr-almashy @amalthea9

(WASHINGTON IRVING)

FOUND AMONG THE PAPERS

OF THE LATE DIEDRICH KNICKERBOCKER

A pleasing land of drowsy head it was,

Of dreams that wave before the half-shut eye;

And of gay castles in the clouds that pass,

Forever flushing round a summer sky.

CASTLE OF INDOLENCE.

In the bosom of one of those spacious coves which indent the eastern shore of the Hudson, at that broad expansion of the river denominated by the ancient Dutch navigators the Tappan Zee, and where they always prudently shortened sail and implored the protection of St. Nicholas when they crossed, there lies a small market town or rural port, which by some is called Greensburgh, but which is more generally and properly known by the name of Tarry Town. This name was given, we are told, in former days, by the good housewives of the adjacent country, from the inveterate propensity of their husbands to linger about the village tavern on market days. Be that as it may, I do not vouch for the fact, but merely advert to it, for the sake of being precise and authentic. Not far from this village, perhaps about two miles, there is a little valley or rather lap of land among high hills, which is one of the quietest places in the whole world. A small brook glides through it, with just murmur enough to lull one to repose; and the occasional whistle of a quail or tapping of a woodpecker is almost the only sound that ever breaks in upon the uniform tranquillity.

I recollect that, when a stripling, my first exploit in squirrel-shooting was in a grove of tall walnut-trees that shades one side of the valley. I had wandered into it at noontime, when all nature is peculiarly quiet, and was startled by the roar of my own gun, as it broke the Sabbath stillness around and was prolonged and reverberated by the angry echoes. If ever I should wish for a retreat whither I might steal from the world and its distractions, and dream quietly away the remnant of a troubled life, I know of none more promising than this little valley.

From the listless repose of the place, and the peculiar character of its inhabitants, who are descendants from the original Dutch settlers, this sequestered glen has long been known by the name of SLEEPY HOLLOW, and its rustic lads are called the Sleepy Hollow Boys throughout all the neighboring country. A drowsy, dreamy influence seems to hang over the land, and to pervade the very atmosphere. Some say that the place was bewitched by a High German doctor, during the early days of the settlement; others, that an old Indian chief, the prophet or wizard of his tribe, held his powwows there before the country was discovered by Master Hendrick Hudson. Certain it is, the place still continues under the sway of some witching power, that holds a spell over the minds of the good people, causing them to walk in a continual reverie. They are given to all kinds of marvellous beliefs, are subject to trances and visions, and frequently see strange sights, and hear music and voices in the air. The whole neighborhood abounds with local tales, haunted spots, and twilight superstitions; stars shoot and meteors glare oftener across the valley than in any other part of the country, and the nightmare, with her whole ninefold, seems to make it the favorite scene of her gambols.

The dominant spirit, however, that haunts this enchanted region, and seems to be commander-in-chief of all the powers of the air, is the apparition of a figure on horseback, without a head. It is said by some to be the ghost of a Hessian trooper, whose head had been carried away by a cannon-ball, in some nameless battle during the Revolutionary War, and who is ever and anon seen by the country folk hurrying along in the gloom of night, as if on the wings of the wind. His haunts are not confined to the valley, but extend at times to the adjacent roads, and especially to the vicinity of a church at no great distance. Indeed, certain of the most authentic historians of those parts, who have been careful in collecting and collating the floating facts concerning this spectre, allege that the body of the trooper having been buried in the churchyard, the ghost rides forth to the scene of battle in nightly quest of his head, and that the rushing speed with which he sometimes passes along the Hollow, like a midnight blast, is owing to his being belated, and in a hurry to get back to the churchyard before daybreak.

Such is the general purport of this legendary superstition, which has furnished materials for many a wild story in that region of shadows; and the spectre is known at all the country firesides, by the name of the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow.

It is remarkable that the visionary propensity I have mentioned is not confined to the native inhabitants of the valley, but is unconsciously imbibed by every one who resides there for a time. However wide awake they may have been before they entered that sleepy region, they are sure, in a little time, to inhale the witching influence of the air, and begin to grow imaginative, to dream dreams, and see apparitions.

I mention this peaceful spot with all possible laud, for it is in such little retired Dutch valleys, found here and there embosomed in the great State of New York, that population, manners, and customs remain fixed, while the great torrent of migration and improvement, which is making such incessant changes in other parts of this restless country, sweeps by them unobserved. They are like those little nooks of still water, which border a rapid stream, where we may see the straw and bubble riding quietly at anchor, or slowly revolving in their mimic harbor, undisturbed by the rush of the passing current. Though many years have elapsed since I trod the drowsy shades of Sleepy Hollow, yet I question whether I should not still find the same trees and the same families vegetating in its sheltered bosom.

In this by-place of nature there abode, in a remote period of American history, that is to say, some thirty years since, a worthy wight of the name of Ichabod Crane, who sojourned, or, as he expressed it, “tarried,” in Sleepy Hollow, for the purpose of instructing the children of the vicinity. He was a native of Connecticut, a State which supplies the Union with pioneers for the mind as well as for the forest, and sends forth yearly its legions of frontier woodmen and country schoolmasters. The cognomen of Crane was not inapplicable to his person. He was tall, but exceedingly lank, with narrow shoulders, long arms and legs, hands that dangled a mile out of his sleeves, feet that might have served for shovels, and his whole frame most loosely hung together. His head was small, and flat at top, with huge ears, large green glassy eyes, and a long snipe nose, so that it looked like a weather-cock perched upon his spindle neck to tell which way the wind blew. To see him striding along the profile of a hill on a windy day, with his clothes bagging and fluttering about him, one might have mistaken him for the genius of famine descending upon the earth, or some scarecrow eloped from a cornfield.

His schoolhouse was a low building of one large room, rudely constructed of logs; the windows partly glazed, and partly patched with leaves of old copybooks. It was most ingeniously secured at vacant hours, by a withe twisted in the handle of the door, and stakes set against the window shutters; so that though a thief might get in with perfect ease, he would find some embarrassment in getting out,—an idea most probably borrowed by the architect, Yost Van Houten, from the mystery of an eelpot. The schoolhouse stood in a rather lonely but pleasant situation, just at the foot of a woody hill, with a brook running close by, and a formidable birch-tree growing at one end of it. From hence the low murmur of his pupils’ voices, conning over their lessons, might be heard in a drowsy summer’s day, like the hum of a beehive; interrupted now and then by the authoritative voice of the master, in the tone of menace or command, or, peradventure, by the appalling sound of the birch, as he urged some tardy loiterer along the flowery path of knowledge. Truth to say, he was a conscientious man, and ever bore in mind the golden maxim, “Spare the rod and spoil the child.” Ichabod Crane’s scholars certainly were not spoiled.

I would not have it imagined, however, that he was one of those cruel potentates of the school who joy in the smart of their subjects; on the contrary, he administered justice with discrimination rather than severity; taking the burden off the backs of the weak, and laying it on those of the strong. Your mere puny stripling, that winced at the least flourish of the rod, was passed by with indulgence; but the claims of justice were satisfied by inflicting a double portion on some little tough wrong-headed, broad-skirted Dutch urchin, who sulked and swelled and grew dogged and sullen beneath the birch. All this he called “doing his duty by their parents;” and he never inflicted a chastisement without following it by the assurance, so consolatory to the smarting urchin, that “he would remember it and thank him for it the longest day he had to live.”

When school hours were over, he was even the companion and playmate of the larger boys; and on holiday afternoons would convoy some of the smaller ones home, who happened to have pretty sisters, or good housewives for mothers, noted for the comforts of the cupboard. Indeed, it behooved him to keep on good terms with his pupils. The revenue arising from his school was small, and would have been scarcely sufficient to furnish him with daily bread, for he was a huge feeder, and, though lank, had the dilating powers of an anaconda; but to help out his maintenance, he was, according to country custom in those parts, boarded and lodged at the houses of the farmers whose children he instructed. With these he lived successively a week at a time, thus going the rounds of the neighborhood, with all his worldly effects tied up in a cotton handkerchief.

That all this might not be too onerous on the purses of his rustic patrons, who are apt to consider the costs of schooling a grievous burden, and schoolmasters as mere drones, he had various ways of rendering himself both useful and agreeable. He assisted the farmers occasionally in the lighter labors of their farms, helped to make hay, mended the fences, took the horses to water, drove the cows from pasture, and cut wood for the winter fire. He laid aside, too, all the dominant dignity and absolute sway with which he lorded it in his little empire, the school, and became wonderfully gentle and ingratiating. He found favor in the eyes of the mothers by petting the children, particularly the youngest; and like the lion bold, which whilom so magnanimously the lamb did hold, he would sit with a child on one knee, and rock a cradle with his foot for whole hours together.

In addition to his other vocations, he was the singing-master of the neighborhood, and picked up many bright shillings by instructing the young folks in psalmody. It was a matter of no little vanity to him on Sundays, to take his station in front of the church gallery, with a band of chosen singers; where, in his own mind, he completely carried away the palm from the parson. Certain it is, his voice resounded far above all the rest of the congregation; and there are peculiar quavers still to be heard in that church, and which may even be heard half a mile off, quite to the opposite side of the millpond, on a still Sunday morning, which are said to be legitimately descended from the nose of Ichabod Crane. Thus, by divers little makeshifts, in that ingenious way which is commonly denominated “by hook and by crook,” the worthy pedagogue got on tolerably enough, and was thought, by all who understood nothing of the labor of headwork, to have a wonderfully easy life of it.

The schoolmaster is generally a man of some importance in the female circle of a rural neighborhood; being considered a kind of idle, gentlemanlike personage, of vastly superior taste and accomplishments to the rough country swains, and, indeed, inferior in learning only to the parson. His appearance, therefore, is apt to occasion some little stir at the tea-table of a farmhouse, and the addition of a supernumerary dish of cakes or sweetmeats, or, peradventure, the parade of a silver teapot. Our man of letters, therefore, was peculiarly happy in the smiles of all the country damsels. How he would figure among them in the churchyard, between services on Sundays; gathering grapes for them from the wild vines that overran the surrounding trees; reciting for their amusement all the epitaphs on the tombstones; or sauntering, with a whole bevy of them, along the banks of the adjacent millpond; while the more bashful country bumpkins hung sheepishly back, envying his superior elegance and address.

From his half-itinerant life, also, he was a kind of travelling gazette, carrying the whole budget of local gossip from house to house, so that his appearance was always greeted with satisfaction. He was, moreover, esteemed by the women as a man of great erudition, for he had read several books quite through, and was a perfect master of Cotton Mather’s ���History of New England Witchcraft,” in which, by the way, he most firmly and potently believed.

He was, in fact, an odd mixture of small shrewdness and simple credulity. His appetite for the marvellous, and his powers of digesting it, were equally extraordinary; and both had been increased by his residence in this spell-bound region. No tale was too gross or monstrous for his capacious swallow. It was often his delight, after his school was dismissed in the afternoon, to stretch himself on the rich bed of clover bordering the little brook that whimpered by his schoolhouse, and there con over old Mather’s direful tales, until the gathering dusk of evening made the printed page a mere mist before his eyes. Then, as he wended his way by swamp and stream and awful woodland, to the farmhouse where he happened to be quartered, every sound of nature, at that witching hour, fluttered his excited imagination,—the moan of the whip-poor-will from the hillside, the boding cry of the tree toad, that harbinger of storm, the dreary hooting of the screech owl, or the sudden rustling in the thicket of birds frightened from their roost. The fireflies, too, which sparkled most vividly in the darkest places, now and then startled him, as one of uncommon brightness would stream across his path; and if, by chance, a huge blockhead of a beetle came winging his blundering flight against him, the poor varlet was ready to give up the ghost, with the idea that he was struck with a witch’s token. His only resource on such occasions, either to drown thought or drive away evil spirits, was to sing psalm tunes and the good people of Sleepy Hollow, as they sat by their doors of an evening, were often filled with awe at hearing his nasal melody, “in linked sweetness long drawn out,” floating from the distant hill, or along the dusky road.

Another of his sources of fearful pleasure was to pass long winter evenings with the old Dutch wives, as they sat spinning by the fire, with a row of apples roasting and spluttering along the hearth, and listen to their marvellous tales of ghosts and goblins, and haunted fields, and haunted brooks, and haunted bridges, and haunted houses, and particularly of the headless horseman, or Galloping Hessian of the Hollow, as they sometimes called him. He would delight them equally by his anecdotes of witchcraft, and of the direful omens and portentous sights and sounds in the air, which prevailed in the earlier times of Connecticut; and would frighten them woefully with speculations upon comets and shooting stars; and with the alarming fact that the world did absolutely turn round, and that they were half the time topsy-turvy!

But if there was a pleasure in all this, while snugly cuddling in the chimney corner of a chamber that was all of a ruddy glow from the crackling wood fire, and where, of course, no spectre dared to show its face, it was dearly purchased by the terrors of his subsequent walk homewards. What fearful shapes and shadows beset his path, amidst the dim and ghastly glare of a snowy night! With what wistful look did he eye every trembling ray of light streaming across the waste fields from some distant window! How often was he appalled by some shrub covered with snow, which, like a sheeted spectre, beset his very path! How often did he shrink with curdling awe at the sound of his own steps on the frosty crust beneath his feet; and dread to look over his shoulder, lest he should behold some uncouth being tramping close behind him! And how often was he thrown into complete dismay by some rushing blast, howling among the trees, in the idea that it was the Galloping Hessian on one of his nightly scourings!

All these, however, were mere terrors of the night, phantoms of the mind that walk in darkness; and though he had seen many spectres in his time, and been more than once beset by Satan in divers shapes, in his lonely perambulations, yet daylight put an end to all these evils; and he would have passed a pleasant life of it, in despite of the Devil and all his works, if his path had not been crossed by a being that causes more perplexity to mortal man than ghosts, goblins, and the whole race of witches put together, and that was—a woman.

Among the musical disciples who assembled, one evening in each week, to receive his instructions in psalmody, was Katrina Van Tassel, the daughter and only child of a substantial Dutch farmer. She was a blooming lass of fresh eighteen; plump as a partridge; ripe and melting and rosy-cheeked as one of her father’s peaches, and universally famed, not merely for her beauty, but her vast expectations. She was withal a little of a coquette, as might be perceived even in her dress, which was a mixture of ancient and modern fashions, as most suited to set off her charms. She wore the ornaments of pure yellow gold, which her great-great-grandmother had brought over from Saardam; the tempting stomacher of the olden time, and withal a provokingly short petticoat, to display the prettiest foot and ankle in the country round.

Ichabod Crane had a soft and foolish heart towards the sex; and it is not to be wondered at that so tempting a morsel soon found favor in his eyes, more especially after he had visited her in her paternal mansion. Old Baltus Van Tassel was a perfect picture of a thriving, contented, liberal-hearted farmer. He seldom, it is true, sent either his eyes or his thoughts beyond the boundaries of his own farm; but within those everything was snug, happy and well-conditioned. He was satisfied with his wealth, but not proud of it; and piqued himself upon the hearty abundance, rather than the style in which he lived. His stronghold was situated on the banks of the Hudson, in one of those green, sheltered, fertile nooks in which the Dutch farmers are so fond of nestling. A great elm tree spread its broad branches over it, at the foot of which bubbled up a spring of the softest and sweetest water, in a little well formed of a barrel; and then stole sparkling away through the grass, to a neighboring brook, that babbled along among alders and dwarf willows. Hard by the farmhouse was a vast barn, that might have served for a church; every window and crevice of which seemed bursting forth with the treasures of the farm; the flail was busily resounding within it from morning to night; swallows and martins skimmed twittering about the eaves; and rows of pigeons, some with one eye turned up, as if watching the weather, some with their heads under their wings or buried in their bosoms, and others swelling, and cooing, and bowing about their dames, were enjoying the sunshine on the roof. Sleek unwieldy porkers were grunting in the repose and abundance of their pens, from whence sallied forth, now and then, troops of sucking pigs, as if to snuff the air. A stately squadron of snowy geese were riding in an adjoining pond, convoying whole fleets of ducks; regiments of turkeys were gobbling through the farmyard, and Guinea fowls fretting about it, like ill-tempered housewives, with their peevish, discontented cry. Before the barn door strutted the gallant cock, that pattern of a husband, a warrior and a fine gentleman, clapping his burnished wings and crowing in the pride and gladness of his heart,—sometimes tearing up the earth with his feet, and then generously calling his ever-hungry family of wives and children to enjoy the rich morsel which he had discovered.

The pedagogue’s mouth watered as he looked upon this sumptuous promise of luxurious winter fare. In his devouring mind’s eye, he pictured to himself every roasting-pig running about with a pudding in his belly, and an apple in his mouth; the pigeons were snugly put to bed in a comfortable pie, and tucked in with a coverlet of crust; the geese were swimming in their own gravy; and the ducks pairing cosily in dishes, like snug married couples, with a decent competency of onion sauce. In the porkers he saw carved out the future sleek side of bacon, and juicy relishing ham; not a turkey but he beheld daintily trussed up, with its gizzard under its wing, and, peradventure, a necklace of savory sausages; and even bright chanticleer himself lay sprawling on his back, in a side dish, with uplifted claws, as if craving that quarter which his chivalrous spirit disdained to ask while living.

As the enraptured Ichabod fancied all this, and as he rolled his great green eyes over the fat meadow lands, the rich fields of wheat, of rye, of buckwheat, and Indian corn, and the orchards burdened with ruddy fruit, which surrounded the warm tenement of Van Tassel, his heart yearned after the damsel who was to inherit these domains, and his imagination expanded with the idea, how they might be readily turned into cash, and the money invested in immense tracts of wild land, and shingle palaces in the wilderness. Nay, his busy fancy already realized his hopes, and presented to him the blooming Katrina, with a whole family of children, mounted on the top of a wagon loaded with household trumpery, with pots and kettles dangling beneath; and he beheld himself bestriding a pacing mare, with a colt at her heels, setting out for Kentucky, Tennessee,—or the Lord knows where!

When he entered the house, the conquest of his heart was complete. It was one of those spacious farmhouses, with high-ridged but lowly sloping roofs, built in the style handed down from the first Dutch settlers; the low projecting eaves forming a piazza along the front, capable of being closed up in bad weather. Under this were hung flails, harness, various utensils of husbandry, and nets for fishing in the neighboring river. Benches were built along the sides for summer use; and a great spinning-wheel at one end, and a churn at the other, showed the various uses to which this important porch might be devoted. From this piazza the wondering Ichabod entered the hall, which formed the centre of the mansion, and the place of usual residence. Here rows of resplendent pewter, ranged on a long dresser, dazzled his eyes. In one corner stood a huge bag of wool, ready to be spun; in another, a quantity of linsey-woolsey just from the loom; ears of Indian corn, and strings of dried apples and peaches, hung in gay festoons along the walls, mingled with the gaud of red peppers; and a door left ajar gave him a peep into the best parlor, where the claw-footed chairs and dark mahogany tables shone like mirrors; andirons, with their accompanying shovel and tongs, glistened from their covert of asparagus tops; mock-oranges and conch-shells decorated the mantelpiece; strings of various-colored birds eggs were suspended above it; a great ostrich egg was hung from the centre of the room, and a corner cupboard, knowingly left open, displayed immense treasures of old silver and well-mended china.

From the moment Ichabod laid his eyes upon these regions of delight, the peace of his mind was at an end, and his only study was how to gain the affections of the peerless daughter of Van Tassel. In this enterprise, however, he had more real difficulties than generally fell to the lot of a knight-errant of yore, who seldom had anything but giants, enchanters, fiery dragons, and such like easily conquered adversaries, to contend with and had to make his way merely through gates of iron and brass, and walls of adamant to the castle keep, where the lady of his heart was confined; all which he achieved as easily as a man would carve his way to the centre of a Christmas pie; and then the lady gave him her hand as a matter of course. Ichabod, on the contrary, had to win his way to the heart of a country coquette, beset with a labyrinth of whims and caprices, which were forever presenting new difficulties and impediments; and he had to encounter a host of fearful adversaries of real flesh and blood, the numerous rustic admirers, who beset every portal to her heart, keeping a watchful and angry eye upon each other, but ready to fly out in the common cause against any new competitor.

Among these, the most formidable was a burly, roaring, roystering blade, of the name of Abraham, or, according to the Dutch abbreviation, Brom Van Brunt, the hero of the country round, which rang with his feats of strength and hardihood. He was broad-shouldered and double-jointed, with short curly black hair, and a bluff but not unpleasant countenance, having a mingled air of fun and arrogance. From his Herculean frame and great powers of limb he had received the nickname of BROM BONES, by which he was universally known. He was famed for great knowledge and skill in horsemanship, being as dexterous on horseback as a Tartar. He was foremost at all races and cock fights; and, with the ascendancy which bodily strength always acquires in rustic life, was the umpire in all disputes, setting his hat on one side, and giving his decisions with an air and tone that admitted of no gainsay or appeal. He was always ready for either a fight or a frolic; but had more mischief than ill-will in his composition; and with all his overbearing roughness, there was a strong dash of waggish good humor at bottom. He had three or four boon companions, who regarded him as their model, and at the head of whom he scoured the country, attending every scene of feud or merriment for miles round. In cold weather he was distinguished by a fur cap, surmounted with a flaunting fox’s tail; and when the folks at a country gathering descried this well-known crest at a distance, whisking about among a squad of hard riders, they always stood by for a squall. Sometimes his crew would be heard dashing along past the farmhouses at midnight, with whoop and halloo, like a troop of Don Cossacks; and the old dames, startled out of their sleep, would listen for a moment till the hurry-scurry had clattered by, and then exclaim, “Ay, there goes Brom Bones and his gang!” The neighbors looked upon him with a mixture of awe, admiration, and good-will; and, when any madcap prank or rustic brawl occurred in the vicinity, always shook their heads, and warranted Brom Bones was at the bottom of it.

This rantipole hero had for some time singled out the blooming Katrina for the object of his uncouth gallantries, and though his amorous toyings were something like the gentle caresses and endearments of a bear, yet it was whispered that she did not altogether discourage his hopes. Certain it is, his advances were signals for rival candidates to retire, who felt no inclination to cross a lion in his amours; insomuch, that when his horse was seen tied to Van Tassel’s paling, on a Sunday night, a sure sign that his master was courting, or, as it is termed, “sparking,” within, all other suitors passed by in despair, and carried the war into other quarters.

Such was the formidable rival with whom Ichabod Crane had to contend, and, considering all things, a stouter man than he would have shrunk from the competition, and a wiser man would have despaired. He had, however, a happy mixture of pliability and perseverance in his nature; he was in form and spirit like a supple-jack—yielding, but tough; though he bent, he never broke; and though he bowed beneath the slightest pressure, yet, the moment it was away—jerk!—he was as erect, and carried his head as high as ever.

To have taken the field openly against his rival would have been madness; for he was not a man to be thwarted in his amours, any more than that stormy lover, Achilles. Ichabod, therefore, made his advances in a quiet and gently insinuating manner. Under cover of his character of singing-master, he made frequent visits at the farmhouse; not that he had anything to apprehend from the meddlesome interference of parents, which is so often a stumbling-block in the path of lovers. Balt Van Tassel was an easy indulgent soul; he loved his daughter better even than his pipe, and, like a reasonable man and an excellent father, let her have her way in everything. His notable little wife, too, had enough to do to attend to her housekeeping and manage her poultry; for, as she sagely observed, ducks and geese are foolish things, and must be looked after, but girls can take care of themselves. Thus, while the busy dame bustled about the house, or plied her spinning-wheel at one end of the piazza, honest Balt would sit smoking his evening pipe at the other, watching the achievements of a little wooden warrior, who, armed with a sword in each hand, was most valiantly fighting the wind on the pinnacle of the barn. In the mean time, Ichabod would carry on his suit with the daughter by the side of the spring under the great elm, or sauntering along in the twilight, that hour so favorable to the lover’s eloquence.

I profess not to know how women’s hearts are wooed and won. To me they have always been matters of riddle and admiration. Some seem to have but one vulnerable point, or door of access; while others have a thousand avenues, and may be captured in a thousand different ways. It is a great triumph of skill to gain the former, but a still greater proof of generalship to maintain possession of the latter, for man must battle for his fortress at every door and window. He who wins a thousand common hearts is therefore entitled to some renown; but he who keeps undisputed sway over the heart of a coquette is indeed a hero. Certain it is, this was not the case with the redoubtable Brom Bones; and from the moment Ichabod Crane made his advances, the interests of the former evidently declined: his horse was no longer seen tied to the palings on Sunday nights, and a deadly feud gradually arose between him and the preceptor of Sleepy Hollow.