#now biden is almost reaching obama's levels

Link

It is a measure of Krugman’s increasing despair that by 2013 his jaundiced view of American class society converged with his worries about the intellectual framing of economics. As Republican and Democratic centrists struggled to fashion a bipartisan majority around a programme to slash the deficit, it dawned on Krugman that the entirety of what he had once confidently described as ‘responsible’ economic policy was shot through with class interest. Talk of fiscal sustainability wasn’t just bad economics; it was, Krugman now believed, class war by stealth. In End This Depression Now (2012), Krugman broke one of the taboos that separate mainstream New Keynesians from their left-wing heterodox counterparts. He invoked the Polish economist Michał Kalecki, whose work is commonly cited as having bridged Keynesianism and Marxism. In 1943, in wartime exile in Oxford, Kalecki had explained why delivering stabilisation policy in a sustained way, as Keynes envisioned, might not be possible in a class-divided society. At the depths of the crisis, Keynesians would be summoned by the powers that be to do the minimum that was necessary, but as soon as the worst had passed, well before the economy reached full employment, the same policies would be anathematised as undermining ‘confidence’. The balance of what was ‘sensible’ would be set by the interests of the wealthiest and most secure. Their principal concern wasn’t full employment, but profit, which dictated stimulus in a slump and restraint whenever profits were squeezed by increased wages in a tightening labour market. Five years before Samuelson, in his classic textbook of 1948, laid out his vision of the complementarity of macroeconomic management and market-based microeconomics, Kalecki had already shown why it would end in failure.

As Krugman remarked, when he first read Kalecki’s essay he ‘thought it was over the top. Kalecki was, after all, a declared Marxist ... But, if you haven’t been radicalised by recent events, you haven’t been paying attention; and policy discourse since 2008 has run exactly along the lines Kalecki predicted.’ After a short burst of emergency Keynesianism, by 2010 deficits not unemployment were the problem. And any effort to push for better conditions was immediately countered with the insistence that it would induce ‘economic policy uncertainty’ and hold the economy back. It wasn’t unemployed Americans, Krugman raged, but imaginary ‘confidence fairies’ that were dictating policy.

Krugman reassured himself by adding that Kalecki was far more of a Keynesian than he was a Marxist, but quibbles aside, Krugman’s own transformation could hardly be denied. The members of the American left he had savaged in the 1990s were now his friends. He was talking about power in the starkest terms. But the question was unavoidable: once you lost your faith in the state as a tool of reformist intervention, once you truly reckoned with the omnipresence of class power, what choices remained but fatalism or a demand for a revolutionary politics? Between those alternatives, respectively unappetising and unrealistic, there was perhaps a third option. America had, after all, been here before. FDR’s New Deal too had been hemmed in. It had delivered far less than promised, until the floodgates were finally opened by the Second World War. The Great Depression, Krugman wrote, ‘ended largely thanks to a guy named Adolf Hitler. He created a human catastrophe, which also led to a lot of government spending.’ ‘Economics,’ he wrote in another essay, ‘is not a morality play. It’s not a happy story in which virtue is rewarded and vice punished.’

‘If it were announced that we faced a threat from space aliens and needed to build up to defend ourselves,’ Krugman said in 2012, ‘we’d have full employment in a year and a half.’ If 21st-century America needed an enemy, China was one candidate. On foreign policy, Krugman is perhaps best described as a left patriot. Where he had once downplayed the impact of Chinese imports on the US economy, he now declared that China’s currency policy was America’s enemy: by manipulating its exchange rate Beijing was dumping exports on America. But to Krugman’s frustration Obama never turned the pivot towards Asia into a concerted economic strategy.

You might argue that in Covid we have found an enemy of precisely the kind Krugman was imagining. As far as Europe is concerned, an alien space invasion isn’t an implausible model for Covid. This novel threat broke down inhibitions in Berlin, and the Eurozone’s response was far more ambitious than it was after 2008. But America isn’t the Eurozone. For all Krugman’s gloom, it didn’t take a new world war to flip the economic policy switch. All it took was an election. Almost immediately after Trump’s victory in November 2016, the fiscal taps were opened. As under Reagan in the 1980s and Bush in the 2000s, all fear of deficits disappeared.

Compelling as Krugman may have found the Kaleckian vision, it does not describe the United States in the 21st century. The balance of class forces Kalecki had assumed in the 1940s no longer exists. In America in 2017 big business did not object to running the economy hot. There was no real threat of wage pressure: a flutter of strikes perhaps, but nothing serious. No chance of inflationary expectations becoming embedded in adjustments to the cost of living. No wage-price spiral. Everything to gain from tax cuts for corporations and the rich. The Kaleckian scenario, from today’s point of view, presumed too much countervailing force from the left and by the same token too many constraints on active economic policy.

Trump opened a new era of voluntarism in economic policy. You really could do what you liked. Neither external threats in the form of bond market vigilantes, nor domestic counterpressure in the form of contending social classes, were any longer effective constraints. American conservatives had never been as keen on the slogan There Is No Alternative as Margaret Thatcher or Angela Merkel. Under Trump there was simply no limit to the GOP’s opportunism. Typically, the centre and left did more intellectual work to come to terms with the new situation. The IMF’s former chief economist, Olivier Blanchard, had painstakingly demonstrated the sustainability of much higher levels of debt in a world of low interest rates. Meanwhile, Modern Monetary Theory had its moment in the sun. Blending state theories of money, radical Keynesianism of 1940s vintage and inside knowledge of the plumbing of the modern financial markets, MMT argued that debt wasn’t a problem at all. The only limit on an expansionary economic policy should be the inflation rate; otherwise the overriding priority should be full employment.

It’s telling that despite the apparent political affinity between Krugman and the proponents of MMT, its heresies revived his impulse to play policeman. After long and fruitless exchanges, Krugman declared that MMT was either silly or merely old-fashioned Keynesianism warmed over. In 2020 these doctrinal debates were overtaken by the reality of the Covid shock. In March 2020, as more than twenty million Americans lost their jobs in a matter of weeks, Congress united around a gigantic fiscal stimulus. At the Fed, the centrist Republican Jerome Powell embarked on a programme of intervention that dwarfed anything contemplated by Bernanke. And with a Democratic majority in Congress the impetus has carried through to 2021. The mantra on everyone’s lips is a blunt statement of Krugman’s position. Do not repeat the mistakes of the early Obama administration. Go large. If the Republicans have now decided to be fiscal conservatives, ignore them. There has been no opposition from big business. What the Chamber of Commerce did not like was the $15 minimum wage. Once that was dropped, it did not oppose the $1.9 trillion plan; it seems that business fears legislative intervention more than it does Kalecki-style pressure in the labour market.

The Krugmanification of the Democrats wasn’t won without a fight. There are fiscal hawks in Biden’s entourage. At one point he even counted Larry Summers as an adviser. That didn’t last: the empowered left wing of the Dems wouldn’t stand for it. But although he is no longer in the inner circle, Summers hasn’t surrendered. Opposing untargeted stimulus checks, calling for more focus on investment, he recently declared the Biden administration’s fiscal policy the most irresponsible in forty years – the result, he remarked bitterly, of the leverage handed to the left of the Democratic Party by the absolute refusal of the GOP to co-operate.

The first instinct of the wonks inside the Biden administration is to counter Summers’s arguments on his own terms. Their models show, they insist, that the risks of overheating and inflation are slight. What they don’t say is that being credibly committed to running the economy hot is precisely the point. This is what Krugman meant in 1998 when he called on the Bank of Japan to make a credible commitment to irresponsibility. To avoid the risk of a liquidity trap what you want to encourage is precisely a general belief that inflation is set to pick up. In the late 1990s Krugman, like a good New Keynesian, envisioned monetary and fiscal policy as substitutes for each other. In 2021 America is getting a massive dose of both. As the Fed announced in August last year, the plan is to get inflation above 2 per cent and to dry out the labour market. The bond markets may flinch, but if the sell-off gets too bad, the Fed can always buy more bonds.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Israel’s Second Struggle for Independence

The USA has been Israel’s greatest friend and supporter in recent years.

It is also Israel’s biggest problem.

Our dependence on American military aid has sharply limited our freedom of action, distorted our decisions about procurement of weapons, crippled the development of our own military industries, corrupted our decision-makers, and damaged our standing as a sovereign state.

It is true that on some occasions Israel has acted against America’s wishes, such as the bombing of the Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981. It is also true that far more frequently, Israel has been forced to bow to US demands, even when they are not in her best interests. In several wars and smaller operations, cease-fires have been dictated by American pressure, although Israel would have preferred to continue fighting longer in order to achieve a decisive victory. During the Gulf War, the US prevented Israel from retaliating for Iraqi Scud attacks. In peacetime, US pressure has prevented Israel from building in Judea and Samaria, and forced Israel to accept Palestinian demands for the release of prisoners. American opposition was a major factor in the decision not to attack Iranian nuclear facilities in the 2010-2012 period.

Israel’s relationship with the US has been better or worse depending on the direction of political winds there, but pressure to reverse the outcome of the 1967 war has been a constant ever since – with the notable exception of the Trump administration, which for the first time recognized Israeli rights to Jerusalem and the Golan heights. But now it seems that the US is taking a turn in the other direction; and this time – thanks to Israel’s conclusive loss of the cognitive war for the consciousness of American elites, the partisan division of attitudes toward Israel, and the new strength of the radical Left in American politics – our time in the wilderness may turn out to be much longer than before.

The inroads being made by elements hostile to Israel into the American educational system, previously limited to higher education, but now reaching into high school and even grade school levels, are troubling. The “intersectional” connections being made between every progressive cause, and the politicization of almost every field of endeavor, have injected the issue of Israel vs. the Palestinians into places where it was not found before.

This is a problem, because our enemies – particularly Iran – are taking advantage of the less pro-Israel climate in the US. The Biden Administration, which has already significantly released the pressure on Iran, appears to be galloping toward a full removal of sanctions, whether or not it will gain significant leverage over their nuclear weapons program. Trump’s sanctions had sent the Iranian economy into a tailspin, which helped energize the Iranian opposition to the repressive and backward regime of the Ayatollahs. Even today, Iranians are in the streets protesting against the regime. But the removal of sanctions will not help them; the regime will funnel cash into its nuclear program, into the pro-Iranian militias in Iraq, Yemen, and Syria, and to build up Israel’s most dangerous enemy, Hezbollah.

At the same time, the Biden Administration, which has staffed its echelons dealing with the Middle East with people less than friendly to Israel – including some with a history of anti-Israel activism (see here, here, and here) – has already restored funding to the Palestinian Authority and UNRWA, plans to re-open the Jerusalem consulate, the unofficial “US Embassy to the State of Palestine” in Jerusalem, and to allow the PLO to restore its embassy in Washington.

A recent poll shows that the Democratic Party, which now controls the House, Senate and the Presidency, has moved significantly away from its formerly solid support for Israel in recent years, with sympathy for Israel among Democrats maintaining a slight edge of only 3 percentage points over sympathy for the Palestinians. The “liberal” wing of the party is far worse, with the Palestinians holding a 15% margin over Israel. Younger respondents also were more likely to favor the Palestinians, which argues for a continuation of the trend. And there is a very vocal contingent in the US Congress that is strongly anti-Israel, and not at all constrained from giving voice to the most extreme anti-Israel propaganda.

The Israeli leadership must come to understand that the continued expectation that Israel will receive military and diplomatic support from the US is unrealistic and dangerous. Israel needs to take action now, to reduce its dependence on the US, to increase its freedom of action, and to build up its own resources in important areas.

There is only one way for a small country in a strategic area to obtain independence from the various empires that wish to make it a satellite, and it is difficult and precarious. That is to play the empires off against one another, and to make alliances with other unaligned nations. I believe that Binyamin Netanyahu understood this, and made small but steady progress in this direction. It remains to be seen if the present government, whose foreign policy appears to be in the hands of the obsequious Yair Lapid, can pull this off.

From the military standpoint, Israel needs to be its own main source of supply. That has implications for the kind of military forces it can field. For example, it may be unrealistic to try to maintain a large fleet of the most sophisticated manned combat aircraft. Drones and precision-guided missiles are far less expensive than F-35s, and while they can’t entirely replace conventional aircraft, a small country will find it more practical to produce and maintain them.

There are also economic considerations. Iron Dome is a wonderful thing, but if it costs $100,000 to intercept a $500 rocket, then massive-scale use of it will bankrupt us. It is much less expensive to deter rocket attacks with the threat of forceful reprisals than to depend on antimissile systems to ward them off. The former strategy is more appropriate for a smaller country whose defense budget is not bottomless. I don’t suggest doing away with antimissile systems entirely, just changing our strategy so that we will not need so many of them.

I recommend that we start moving in this direction now, by agreeing with the US to a gradual phase-out of military aid. At the same time, we will have to revitalize our domestic military industries. Barack Obama very cleverly did not decrease the level of military aid we received, to maintain the maximum leverage over our actions. But the percentage of that aid that could be spent outside of the US was set to gradually drop to zero over the next few years. This had the effect of increasing the subsidy that aid to Israel provided to US defense contractors, and weakening Israel’s home-grown industry. This made us more dependent and at the same time reduced the competition to American weapons suppliers in the world market. A win-win-win for the US, but a loss for us.

America is changing in ways that are not good for America, and not good for us. I hope that the political/cultural pendulum in the US will swing the other way. Probably it will, if the nation survives the present storm intact. But here on the other side of the world, Israel’s enemies are not waiting with their hands folded. She will either adapt to the new situation or find herself in deep trouble.

Abu Yehuda

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Satan

By Daymond Duck Published on: August 1, 2021

The writer of this article was recently asked, “Why do the globalists who are supposed to be very intelligent make decisions that are so clearly wrong?”

Most don’t realize it, but Satan is behind their evil.

He has blinded them to the extent that they don’t believe the Bible is the Word of God.

They push a godless world government, world religion, same-sex marriage, tracking everyone, etc., because they are not Christians (even though some falsely claim to be good Catholics, etc.).

Many were appointed by like-minded people, not elected by voters or nations.

They wouldn’t dare have an election because they don’t believe they can get elected.

The globalists overlook what the Clintons and Bidens have done because they share similar views on the issues listed above.

Their puppets impeached Trump twice because he opposed their views.

Their prosecution of Trump supporters for what happened at the capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, while ignoring the rioting, looting, destruction of property, etc. by Antifa, Black Lives Matter, and others, should concern every conservative and Christian because when the globalists get the upper hand (and they will), they will destroy the U.S. Constitution, and persecute and destroy those that disagree with them.

When they give their Antichrist power, he will go forth conquering and to conquer (Rev. 6:1-2; 13:4-7).

The following events indicate that the latter years and latter days, globalism, global pandemics, food shortages, persecution, etc., are on the horizon.

One, concerning the Battle of Gog and Magog in the latter years and latter days: on July 20, 2021, Sen. Lindsey Graham said, “The Iranians are progressing (on their development of nuclear weapons) at a dangerous pace.”

“Israel may need to take pre-emptive military action against Iran.”

“I’ve never been more worried about Israel having to use military force to stop the program than I am right now.”

Two, also concerning the Battle of Gog and Magog: it was reported on July 21, 2021, that Israel’s military and foreign intelligence agency said Israel needs a variety of plans to sabotage, disrupt and delay Iran’s development of nuclear weapons, and they will probably be asking for the money and resources to do that.

Three, also concerning the Battle of Gog and Magog: Israeli Prime Min. Netanyahu and Russian Pres. Putin agreed that Israel would give Russia advance notice of Israeli attacks in some areas of Syria, and Russia would not intervene.

Israel jets recently fired several missiles at Iranian targets near Aleppo, Syria, and a Russian official said Syria used Russian-made anti-missile systems to shoot down all of Israel’s missiles.

On July 24, 2021, DEBKAfile, an Israeli intelligence and security news source group, reported that a Russian official confirmed that Russia has changed its policy on not intervening in Israeli attacks in some areas of Syria because Russia has received confirmation from the Biden White House that the U.S. does not condone the continuous Israeli raids.

Thus, while the Biden administration is publicly saying Israel has a right to defend itself, it is telling Russia that some of Israel’s efforts to do that are unacceptable.

The Bible clearly teaches that the merchants of Tarshish and all the young lions (perhaps includes the U.S.) will not help Israel during the Battle of Gog and Magog (Ezek. 38:13).

Corrupt world leaders, deceit, and lying are also signs of the end of the age.

Four, on July 27, 2021, i24NEWS reported that Israel has notified the Biden administration that Iran is on the verge of crossing the nuclear threshold, and it could happen at any moment.

Because Pres. Obama sent Iran a planeload of money during his administration and seems to be influencing events in the Biden administration, notifying Biden might be a waste of time.

This may help explain the belief that the U.S. will not help Israel during the Battle of Gog and Magog (Ezek. 38:13).

Five, concerning famine: it is common knowledge that the Covid-19 lockdowns disrupted the world’s food chains (farmers and farmhands were quarantined; stores ran out of toilet paper, some foods, etc.; food processors closed or cut back; some trucks stopped rolling, etc.).

On July 23, 2023, it was reported that there are still bare shelves in some food stores in the U.K., the food supply chains are “at risk of collapse,” millions of workers have been ordered to self-quarantine, the food industry is running out of workers to keep the stores supplied, and the U.K. could be just a few months away from a major crisis.

Under the guise of stopping the spread of Covid, the U.K. government may be creating “food shortages and mass famine.”

Note: It was recently reported that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell warned that there will be another lockdown in the U.S. if American citizens “don’t wise up and get vaccinated against Covid-19.”

Note: On July 28, 2021, in an interview on “Fox & Friends,” Stuart Varney said an important business group is predicting that supply shortages will last until 2023.

Some prophecy teachers believe that Covid-19 is a created crisis (a pretext, a set-up, perhaps an engineered cluster of catastrophes) that globalists are using to prepare the world for a world government.

According to the pro-liberty group, Brighteon, on July 22, 2021, “very few people are prepared to survive a multi-layered, engineered cluster of catastrophes that are unleashed on top of each other.”

God’s Seal, Trumpet, and Bowl judgments during the Tribulation Period will be multi-layered catastrophes (pandemics, famine, economic collapse, etc.) on top of each other, and very few will survive.

Note: This writer believes we could be watching the development (early stages) of those multi-layered judgments.

Six, concerning deceit: on July 20, 2021, Sen. Rand Paul said on Sean Hannity’s T.V. program, “I will be sending a letter to the Department of Justice asking for a criminal referral (of Dr. Anthony Fauci) because he has lied to Congress” (about the involvement of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the research at China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology).

Note: This writer does not know how to verify it but has seen reports that Fauci owns stock in one or more of the companies that have been approved to sell the Covid-19 vaccine (If true, he is likely profiting off forcing people to be vaccinated and opposing the use of Hydroxychloroquine and Ivermectin).

Second Note: It has been reported that Fauci could spend up to 5 years in prison, but it is the opinion of this writer that the globalists (also called the Shadow Government, Deep State, super-wealthy elitists, etc.) will protect him because they are pro-vaccination. They want him to keep using his ever-changing fake science.

Seven, concerning world government and open borders: on July 21, 2021, it was reported that keeping the U.S. border with Mexico open is costing about 3 million dollars a day in suspension and termination payments to contractors to guard steel, concrete, and other materials they have in the desert.

Eight, militant Muslims say Jews should not be allowed on the Temple Mount because the entire Temple Mount is an Islamic site and none of it belongs to Israel.

For this reason, Jewish officials have allowed Jews to visit the Temple Mount at certain times, but they have not been allowed to pray on the Temple Mount.

On July 17, 2021, the eve of Tisha B’ Av (a holiday for remembering the destruction of the first 2 Jewish Temples; July 17-18 in 2021), it was reported that Jews were praying (and some were teaching Torah, a name for the Scriptures in the first 5 books of the Bible) on the Temple Mount.

On July 20, 2021, Prime Min. Bennett came out in support of freedom of worship for Jews on the Temple Mount.

This may lead to more violence, but it is worth noting that the Jews have gone from not being allowed to pray on the Temple Mount to praying and teaching on the Temple Mount, and Israel’s new Prime Min. supports it.

According to the Bible, the Jews will eventually get permission to rebuild the Temple.

Update: On July 25, 2021, it was reported that the temporary truce between Israel and the Palestinians is fragile, may be coming unraveled, and another war could be on the horizon.

Nine, concerning pestilence: on July 22, 2021, Israeli Prime Min. Bennett said as of Aug. 8, 2021, Israeli citizens will not be allowed to enter synagogues and other facilities without a vaccine certificate or proof of a negative Covid-19 test.

U.S. citizens are not having to prove that they have been vaccinated to attend places of worship, but some companies are requiring it.

Ten, concerning natural disasters: on July 26, 2021, it was reported that June in North America was “the hottest in recorded history.”

Record high temperatures were broken in several western states.

On June 28, 2021, the temperature was 117 degrees in Salem, OR; 110 in Redmond OR; 110 in Quillayute, WA; 110 in Olympia, WA etc.

The southwest U.S. is experiencing the worst drought in 122 years.

It covers almost 90% of the southwest, and much of that is classified as severe to exceptional drought.

Reservoirs and rivers are drying up, fish are dying, wildlife is suffering, farmers and ranchers are hurting, crop and cattle production is down, some ranchers and dairy farmers are going out of business, water rationing is beginning to kick in, and more than 60 million people are impacted.

Lake Mead, a 112-mile-long water reservoir, is at its lowest level since it was built 85 years ago (It is now only 35% full).

Utah’s Great Salt Lake has reached a record low.

86 wildfires are burning in 12 states, drought conditions have made them worse, two major wildfires have merged, and more than 10,000 houses are in danger.

The long-range forecast is for the high temperatures to continue through the fall.

Call it what you want; some officials are already blaming it on global warming because it fits their globalist agenda. But natural disasters will be like birth pains (increase in frequency and intensity) at the end of the age, and this record-breaking event seems to qualify.

As I close, understand that as bad as things are right now, Satan and the Antichrist are limited or partly restrained (II Thess. 2:7-9).

But the time will come (the Tribulation Period) when Satan and the Antichrist will no longer be restrained, and the events will be worse than anything that has ever happened or ever will happen (Matt. 24:22).

Finally, are you Rapture Ready?

If you want to be rapture ready and go to heaven, you must be born again (John 3:3). God loves you, and if you have not done so, sincerely admit that you are a sinner; believe that Jesus is the virgin-born, sinless Son of God who died for the sins of the world, was buried, and raised from the dead; ask Him to forgive your sins, cleanse you, come into your heart and be your Saviour; then tell someone that you have done this.

#tumblr#tic tok#facebook#anime#memes#twitter#water#wildfires#farmers#ranchers#famine#drought#crops#cattle#forecast#news#lockdown#the#great#reset#NWO#globalist#evil#agenda

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

A Democratic president just entered the White House, so it’s time for Republican state officials to start discussing secession once again. After Barack Obama’s reelection in 2012, disaffected conservatives flooded the White House petition site with calls to leave the Union. (They were predictably denied.) Now a smattering of state party leaders and lawmakers are once again raising the question: Should we stay or should we go?

“We need to focus on the fundamentals,” Wyoming GOP chairman Frank Eathorne said in an interview with Steve Bannon last week, according to The Casper Star-Tribune. “We are straight talking, focused on the global scene, but we’re also focused at home. Many of these Western states have the ability to be self-reliant, and we’re keeping eyes on Texas too, and their consideration of possible secession. They have a different state constitution than we do as far as wording, but it’s something we’re all paying attention to.”

Kyle Biedermann, a Republican state lawmaker in Texas, recently claimed that he plans to introduce a bill to hold a referendum on leaving the United States. “The federal government is out of control & doesn’t represent the values of Texans,” he wrote on Twitter last month. “That is why I am committing to file legislation that will allow a referendum to give Texans a vote for the State of Texas to reassert its status as an independent nation.” Allen West, the Texas GOP chair, said after the Supreme Court refused to overturn Biden’s lawful victory that “law-abiding states should bond together and form a Union of states that will abide by the Constitution.” Many took this as a reference to secession.

I’ve previously tried to make a moral and democratic case for the Union. Balkanizing ourselves over transitory political differences is short-sighted and anti-democratic. But as this feeble specter rears its head once more, it’s also worth also considering the practical and economic case for the Union. And to truly understand that, we need look no further than those responsible for the Union’s existence in the first place: the British.

Four and a half years ago, Britons narrowly voted to leave the European Union, the economic and political bloc that tore down borders and barriers across the continent. Brexiteers sold the country’s departure as a way for the U.K. to take back control of those borders and build new trade relationships outside Europe. It was a fantastical exercise in populism that spent little time grappling with the hard reality of how Britain would extract itself from a 40-year governance relationship, let alone with the rocky roads that a United Kingdom would traverse once it was disunited from the continent. Four years of bargaining and two toppled governments later, Prime Minister Boris Johnson finally signed an exit deal with EU leaders last month.

How have Britain’s first few weeks of “independence” gone? Not great. Goods and services used to flow nearly frictionlessly across British soil and the rest of the continent. Now they’re ensnared in a complex system of border controls and customs checks. Perishable goods are hardest hit. Scottish seafood is struggling to get into continental Europe; Northern Ireland is experiencing food shortages because goods can’t easily cross over from the south. The Bank of England warned that the country’s gross domestic product could drop by 2 to 4 percent because of Britain’s withdrawal, largely as a result of the added paperwork and regulation.

And then there’s the long-term damage. Nostalgic Brexiteers sold the referendum as a potential boon for Britain’s once-dominant manufacturing sector. But roughly four-fifths of the modern British economy is actually driven by its service industries, which were largely left uncovered by the exit agreement with the EU. London is unlikely to lose its status as a world financial hub any time soon, but firms are already relocating jobs and accounts to Paris, Amsterdam, Dublin, and other European capitals—the better to retain smooth access to the EU financial sector. Britain is also forsaking its role in the EU’s Erasmus program, cutting off British students from study opportunities across Europe—and blocking European students from easily studying at British universities. That sort of lost potential is hard to quantify but easy to mourn.

But in many ways, the U.K. leaving the European Union is easy compared to Texas Texiting the U.S. Britain was already an independent country, despite what the pro-Brexit enthusiasts liked to suggest, with a highly skilled civil service and a world-class diplomatic corps. It already possessed all the trappings and organs of a modern developed country. The economic tumult it’s experienced over the past few weeks—and negotiated over the past four years—largely comes down to a mismatch of paperwork between two different regulatory systems.

Extracting oneself from the U.S. would be far more complicated. For starters, Texas would have to fund and staff something resembling a modern regulatory state. Some of this framework already exists at the state level, but not all of it. There would need to be a Texas Food and Drug Administration, a Texas Environmental Protection Agency, a Texas Securities and Exchange Commission, and much more. Texas would have to buy property to build embassies in foreign capitals and hire diplomats to staff them. It would have to build its own army, navy, air force, intelligence service, and postal system. That costs a lot of money. Texas doesn’t even have a state income tax; one-third of its budget comes from the federal government.

Would Texas use its own currency? It would have to create its own central bank and monetary policy if it did. Since Britain never adopted the euro, this is one major complication of leaving the EU that never came up. When Scotland weighed leaving the rest of the U.K. in 2014, Scottish independence leaders proposed that they would keep the pound sterling and maintain some sort of currency union with the rest of their former country. But London itself wasn’t keen on the idea, and the Scottish National Party now favors adopting the euro in a post-Brexit world. Texas could always take the route adopted by El Salvador and adopt the U.S. dollar outright as its currency. So much for national sovereignty if it did, though.

Free movement would be another issue. It’s virtually impossible to denaturalize a U.S. citizen against their will, so most Texans would retain their American citizenship unless they voluntarily renounce it. And even though birthright citizenship would obviously not apply within a foreign country, the children of those U.S. citizens could still be eligible for citizenship under existing federal laws. Texas’s Republican leaders often brag about how its growth is fueled by businesses and residents leaving other states for lower taxes and lighter regulations. But that formula would invert itself after independence: Most of Texas’s population would easily be able to decamp back to the U.S., while residents of the other 49 states would have to go through some sort of immigration process to live in Texas.

And then there’s the problem of trade barriers. The Constitution forbids one state from imposing tariffs or taxes on goods from another state. It’s also virtually impossible for states to lawfully block Americans from entering or exiting them. (The current system of “travel restrictions” due to the pandemic is one of the only exceptions to that rule.) Indeed, the entire American economy is built around the free flow of goods and most services between California, Texas, New York, Florida, and everywhere in between. Without that freedom, Texas would have to negotiate some sort of Nafta-like deal between itself and the rest of the U.S. to carry out basic economic functions without significant difficulty.

That’s where the #Texit dreams really fall apart. Why would Texas and the U.S. need to create some sort of trade deal? Again, look no further than Brexit. If Britain had not reached an accord with the EU before the legal deadline of December 31, 2020, it would have crashed out of the union in what was called a hard, no-deal Brexit. Trade between the U.K. and the EU would have defaulted to World Trade Organization rules, raising all manner of tariffs and duties on everyday goods. The resulting economic fallout spurred leaders on both sides to strike a bargain. While Europe is not as dependent on British trade as Britain is on EU trade, enough of its businesses would have been affected that few leaders truly wanted to see a no-deal break happen.

So, in addition to funding and creating all of the features of modern nationhood, Texas would have to negotiate some sort of trade agreement with the U.S. to actually survive. Like Britain, it would be somewhat at the mercy of the much larger trading partner. But the U.S. also has no interest in making it easier for states to leave the Union, so it would have no incentive to play as nicely as the Europeans did with the British. At minimum, Texas would almost certainly have to compensate the U.S. for the loss of all sorts of federal property: Fort Hood and other military bases, Johnson Space Center and other NASA facilities, various post offices, courthouses, prisons, and so on. It would likely also have to play by rules set by U.S. regulatory agencies and conduct most of its business on terms set by U.S. trade negotiators. Texas, like Britain, could easily end up in a much worse position than the status quo it enjoys now.

All of this assumes that Texas peacefully leaves the Union with Congress’s assent. That’s the only constitutionally valid scenario suggested by the Supreme Court’s ruling in, ironically, Texas v. White in 1869, in which the justices held that states can’t unilaterally secede and the so-called Confederacy never lawfully existed. We’ll set aside the unlikelihood of a peaceful departure for now, and instead ponder its alternative. Secession was a gambit at best in 1860 when almost a dozen rebel-led states tried to withdraw by force. It took the U.S. five years and 600,000 dead to force the Confederate armies to surrender in the Civil War. The asymmetry between the modern U.S. military and whatever state militia Texas could muster is so great that putting down a rebellion this time might only take five weeks.

But let’s go back to the peaceful option once again. If the Texas legislature voted to secede tomorrow, there is zero chance that a Democratic Congress and a Democratic president would support its departure. And if a Republican president and a Republican Congress held power—as they did not but two years ago—Texas, Wyoming, or any other Republican-led state wouldn’t want to secede in the first place. Why would Donald Trump or any future Republican president want to let their biggest batch of electoral votes walk out the door? Secession’s greatest challenge isn’t that it’s a bad idea but that the incentives make it all but impossible to carry out.

Finally, notice that I used Texas as the example here instead of Wyoming. That’s because Texas stands a better chance of actually surviving as an independent country than any other state, except perhaps California. It would be among the largest economies in the world if it became a sovereign country tomorrow—and it would immediately struggle to maintain anything resembling its current standard of living. Wyoming, despite the dreams of its state GOP chair, would be doomed to failure if it seceded. That’s one reason why the Union is so great in the first place, of course. Everything may be bigger in Texas, but everything is ultimately better in the U.S.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

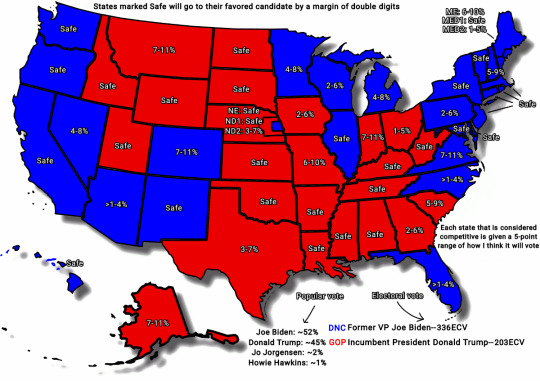

Final election prediction map:

Explanation time. Going from left to right.

Nevada: this state is known for overestimating republican support in the polls. Even republican-biased pollsters like Trafalgar(R) think Biden is going to win here. Regular polls tend to give Biden about a six point lead. So I think 4-8% is the most likely margin for this state.

Arizona: A very close state. It voted for Trump last time by a margin of three percent, and Biden generally leads in the polls here from 2% or 4% depending on which polling group most recently posted. Discounting obviously biased polls like Trafalgar, CNN, and Rasmussen, it is most likely that Biden will narrowly win Arizona. FiveThirtyEight and RealClearPolitics agree on this and so do I.

Alaska and Montana: States that would normally be more decisively red but aren't this time around. Still, trump is leading in these two by enough that it won't matter. Just something to keep in mind, that Biden has moved republican states more towards the democrats.

Colorado: Used to be a swing state, but now is about at the same level of closeness as in Montana. RealClearPolitics says Biden is leading by ten percent, FiveThirtyEight says by fourteen percent, predicting that they will vote within a 7-11% range is a modest estimate not Democrat bias. Not only that but like Nevada and Texas, it voted more blue than expected in 2016.

New Mexico: Republicans have been trying to get this state but it's just not happening. They have a 15% poll lead for Biden on my most recent map. Even if the polls are off some, in Trump's favor, Biden still wins by double digits.

Nebraska: Both the main state and the first district are going to Trump, no real question there. But the second district has held some polls and they all lean towards Joe Biden winning. It's just one extra electoral vote though.

Texas: A state that has been all over the place lately with large amounts of early voting (which favors dems) and a court that denied throwing out a hundred thousand ballots. It's not out of reach that democrats could win Texas, but if I'm being wholly honest with myself, what I want to happen is not necessarily what will happen. The polls do lean in Trump's favor. And Republican support is still large in Texas. Worst of all, there is only one early voting drop off box per county in Texas. I think it's going to the reds this time around, although at a narrower margin than 2016.

Minnesota: This one I can't be too sure about to be honest. On one hand, the police brutality there and protests (mainly the government's response to the protests) will likely mean more dem turnout. But at the same time, people protesting racism and the authoritarian gov? Also means more Republican turnout for Trump. But Republicans already turn out to vote regularly, so it's not so much that they can expand from here and more than they can try and use the protests as a means to convince people to not vote got Biden. Still, Biden's campaign has generally brought in more support to the democrats than Hillary's across the nation and Minnesota went to her last time. And 4-8% does match up pretty well with polling data which ranges around a 6% to 7% lead for Biden.

Iowa: Sometimes leans Biden, other times it leans Trump, but in general it's a pretty close state. But Trump had a 9% margin of victory in 2016 and I think that is going to be very hard to overcome. Of course Biden has moved the country towards the democrats, but probably not by the ten percent margin it would take to win Iowa. It just has a lot of conservative support, and unless something is drastically off in my analysis, Trump is going to win Iowa by a few percentage points.

Missouri: Like a couple other states already mentioned, it's strange that it isn't automatically safe. RealClearPolitics even considered Missouri a toss up state at one point. Based on the polling data involving this state and how it's voted previously, I think it's going to Republicans by a margin of 6-10%.

Wisconsin: Oh boy. The one state who's polling data was well outside the margin of error in 2016. It was seven percent off. And current polls for the state range from a slight one or two point win for trump to a seventeen point landslide for Biden. It's a bit absurd how hard this state is to predict. But, I think it is landing on the Biden side of the aisle and will vote Democrat by about the same amount as Iowa votes Republican. Biden is more liked there than Hillary Clinton, and that is true for the whole Midwest. Not only that but most Midwestern states including Wisconsin voted more democratic in the 2018 midterms. Less biased polls put Biden at a six percent lead in Wisconsin. Which is roughly the same as Clinton's state. In most states Biden is doing better than Clinton was, but I suppose some really biased towards dems polls came out for Clinton in Wisconsin right before the election as it's the only logical explanation. Several polls also have shown Biden winning in double digits in Wisconsin, hopefully these are the ones that are exaggerating democratic support and not the more average polls. Assuming the more biased polls are the ones that could be seven points off in Republicans favor, Biden wins by a few percent.

Michigan: Without Trafalgar(R) and Rasmussen, Michigan looks as decisive for Biden as South Carolina is for Trump. It's polling average on RCP had Biden nine points up. In a state that just barely went to Trump in 2016. Michigan is almost certainly going to Biden if everyone who prefers Biden actually turns out to vote for him. Many polls show Biden up in double digits there. Trump has personally hurt his reputation in Michigan. Largely due to personally refusing them covid aid while the state run by democrats was handling the pandemic better than any other state according to a covid response study. Which is bound to increase their approval of democrats and decrease it of Trump. His supporters even tried to kidnap the governor to do god knows what to her, and Biden won Michigan in the primaries over Sanders, who beat Clinton there in the 2016 primaries. It's very likely that Biden will see a win in Michigan, and by fairly strong margins assuming all the votes get counted in time. Whether you look at the polls, how they voted in the midterms, the margin at which Trump won in 2016, other factors that could effect the vote, Biden is set to win the state of Michigan. A voting margin of 4-8% is a rather modest prediction all things considered. Even some conservative biased polls have shown Biden winning by a percent or two. Polling groups like Trafalgar(R) voted about two points to the right of the final results in the rust belt states.

Indiana: Not a whole lot to say here. Much like Missouri and Montana, it's closer than it should be and that's a bad sign for Republicans in neighboring swing states.

Ohio: This state has voted 8 points in favor of the Republicans in 2016, and the polls have gone back and forth between the candidates recently. But they are very close. I think Trump will take the state by at least one point though. And no more than five. Going to be as close as Iowa at least, maybe a little closer, but Biden will be hard pressed to flip the state completely.

Virginia: Polling shows Biden possibly leading in double digits and Clinton won fairly decisively here. Even the most narrow recent Virginia polls show Biden eight points ahead. It's barely competitive, luckily for Biden.

North Carolina: Like Arizona, this state is a hard call because of how close it is. I wouldnt be surprised if either won. But Biden does have the overall edge and is more likely to take the state by a close margin.

South Carolina: Usually a solid red state. But this time around, it got fairly close in the polls. Closer than some traditional blue leaning swing states. Still almost definitely going to Trump, but, it did vote in a new Democrat in 2018 and if this momentum keeps up who knows, South Carolina could end up more like Iowa. A red leaning swing state. Probably not tomorrow though. It's going to have a pretty solid margin of victory for Trump.

Georgia: Very similar story as Texas but a little more towards dems. Biden does narrowly lead in the polls, but republican support in this state is historically usually strong and racial voter surpression could unfortunately have an effect by a percent or two. It's certainly possible for Democrats to win here, but it's probably not going to happen this election. Trump will likely have a pretty close lead of two to six percent. Like Texas, it's sort of a "What if dems get a landslide" scenario. It would certainly be closer if there wasn't so much concern about voter surpression and gerrymandered voting districts. I would say Biden has about as much chance of winning in Georgia as Trump does of winning Pennsylvania.

Florida: It is very close in every election. The best and least biased polls put it at a Biden win though. A narrow one, but with strong turnout it's more likely dems take this state. If GOP does take Florida it will be by a hair margin. Less than one percent. But I think it will land on Biden's side of the aisle due to factors such as the Coronavirus mainly effecting the elderly the worst and Florida being an older state, Florida voting more blue in 2018 like several other states, and the only polls showing Trump winning there are the ones with biased weights and faulty methods of polling. Biden is also a favorite in Florida, as they elected him decisively during the primary. And he was on the twice winning Obama/Biden ticket.

Pennsylvania: Like Wisconsin, I estimated a 2-6% margin of victory and this state has been fairly consistently showing a five point lead for Biden in the FiveThirtyEight model. It has overall moved to the left since 2016 and the administration there has been fighting Trump's attempts of rigging its vote count. I think this state is going to Biden, RealClearPolitics thinks this state is going to Biden, FiveThirtyEight thinks this state is going to Biden, but it all relies on Pennsylvanians actually going out and making those poll averages come true. But unlike last time, they actually know Trump can win and won't just assume it's over simply because of the polls. Even Rasmussen, a conservative biased polling group republicans love to tout, shows Biden winning by three percent. It's going to be pretty close though, so it comes down to the turnout.

New Hampshire: You're probably tired of having me say things are going to be close. Well, New Hampshire was close last time but I don't think it will be this time. The polls for this state are quite decisive (11% lead for Biden on average!) and Clinton did win last time in this state although narrowly. Estimating it to be a 5-9% margin of victory for Biden is not unreasonable, even though Biden didn't do well in the New Hampshire primary, he is bound to win this small swing state by a similar margin as Trump will win South Carolina, which is not known to be a swing state.

Maine: Biden is bound to get at least 3/4 of the electoral votes here, but I think it's likely that his campaign has won back enough support here that he can get all four. A recent poll by an A+ rated pollster puts him three points ahead in the remaining district. But I wouldn't be surprised if Trump picks up one district. One electoral point likely won't matter to the overall election though.

National:

Biden has been consistently leading over trump since before the primary voting started. His national lead on trump is the main factor why he won the primary in the first place. Biden will get the popular vote, as the popular vote was barely off in the 2016 polls and this time around Biden consistently has at least double, sometimes TRIPLE, the poll lead Clinton had by the day before the election. The lowest I've seen it was four points ahead of Trump. The highest was ten points ahead. He will most likely get around a seven point lead in the popular vote, which indirectly increases his likelihood of winning the electoral college as well. Even though winning one does not necessarily mean winning the other, it is VERY unlikely that someone could get a seven percent popular vote lead and not win the election. Remember, Clinton had less than a three percent popular vote lead and trump only won key states she was expected to win by a sliver.

Third parties probably won't make a whole lot of difference. In 2016, it was a big year for them although it may not look like it. Lots of people assumed Clinton would win, and it made it easy to justify using one's vote on a third party candidate. Nowadays people can see how close it will be and how it is anyone's game, and some will choose to vote either Trump or Biden instead of their preferred candidate like in 2016. Third party polling is not looking good. And it always tightens up on election day. If any do split the vote enough, it's probably not something that said party not running would help anyway. If you're voting green party still, you're probably not willing to vote for Biden even IF the greens didn't run in your state. And if you're voting Libertarian, you're probably not going to vote for Trump even IF Libertarians didn't run in your state.

In conclusion, I think Biden will win both in terms of having the most actual votes, and in terms of having the most electoral votes which are the real deciding factor. But the election could still be contested by the Supreme Court if it's close enough which it likely could be. And the vote count could be stopped prematurely to erase tens of thousands of dem-majority mail-in ballots.

What constitutes a correct prediction?

I will consider it correct if all of these are true:

1: Biden wins overall

2: I get at least 95% of the state colors correct

3: I get at least 90% of the state margins correct

4: I'm right about Biden's popular vote lead within a margin of a percent in one direction or another.

This prediction also assumes that all of the legitimate votes cast are counted. We may not see the end result until a couple of days after election day. If the election is halted with tens of thousands of mail-in votes unaccounted for, I will consider it inconclusive.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 Keys to the White House

Political historian Allan Lichtman developed a method which has allowed to correctly predict every presidential election since 1984, and working backwards this same method retroactively accounts for every single election since 1860. The only hiccup was in 2000, when he predicted Gore would win, which he technically did.

Every election comes down to 13 keys, 13 yes or no questions on the state of the union during the previous presidential term. Lichtman claims that voters are smarter than we give them credit for, and won’t just blindly follow one party or the other, but will consciously reward whichever party maintains some semblance of order during their time in office. He claims that campaigning and advertisements are irrelevant, because people have usually already made up their minds, and the only thing that matters is election day itself.

Each election, Lichtman asks 13 questions directed towards the incumbent party, to determine how they’ve done over the past few years. If 8 or more of the questions are true, then the incumbent party is predicted to win. If 6 or more are false, the challenging party is predicted to win.

Party Mandate: After the midterm elections, the incumbent party holds more seats in the U.S. House of Representatives than after the previous midterm elections. FALSE (Democrats won more in 2018 than Republicans won in 2014)

Contest: There is no serious contest for the incumbent party nomination. TRUE (Donald Trump faces no real challengers)

Incumbency: The incumbent party candidate is the sitting president. TRUE (barring the coronavirus, or a heart attack brought on by all the fast food he eats, Donald Trump will be the nominee this November)

Third party: There is no significant third party or independent campaign. True, as of right now (Justin Amash is running as a Libertarian, but it’s unclear if he’ll reach Gary Johnson/Jill Stein levels, certainly not Ross Perot levels. Frankly, he’s only running for president to save face because he doesn’t stand a chance of winning his House seat back; he left the Republican party, so all of his constituents hate him, and he’s too conservative for the Democrats. We’ll see how this goes)

Short-term economy: The economy is not in recession during the election campaign. FALSE (The Great Shutdown, the second once-in-a-lifetime economic collapse in less than 15 years. We’re only four months into it right now; things are going to get so much worse before they get better.)

Long-term economy: Real per capita economic growth during the term equals or exceeds mean growth during the previous two terms. Unclear (Obama’s first time saw only 3.9% growth due to the end of the Great Recession, but his second term saw dramatic improvement with 8.8%. This averages to 6.35% growth per term. As of 2019, Donald Trump’s first term has seen 7.6% growth, but taking into account the recession, it is almost certain that our 2020 GDP will drop because of this. It only needs to drop 1.25% to be below Obama’s average, so maybe)

Policy change: The incumbent administration effects major changes in national policy. Maybe (this is incredibly subjective, now more than ever. What constitutes “major” change? The McConnell controlled Senate has been blocking all major legislature since 2015, and Trump still hasn’t managed to meet any of his campaign promises; he didn’t build the wall, he didn’t lock her up, he didn’t get rid of Obamacare. Then again, he has greatly expanded the executive branch, giving the president total power to just ignore Congress is he so desires, so it could go either way)

Social unrest: There is no sustained social unrest during the term. Probably false? (again, this is subjective; what constitutes “unrest?” There are regular protests, but they’re all organized and civil. Some nut jobs stormed the Michigan state capitol with guns to “take back the state,” and nobody was arrested, which seems like unrest to me, except they were on the president’s side. I don’t think it will get to civil war levels, or martial law declarations, but rest assured the country is not happy with him)

Scandal: The incumbent administration is untainted by major scandal. Almost certainly false. (indictments galore; so many of his associates are in jail, almost all of his original cabinet secretaries quit or were fired, and he admitted to trying to blackmail Ukraine to dig up dirt on Joe Biden, was impeached for it, and got away with it. This man is a walking scandal. The question is, what does “untainted” mean? Yes, there have been endless scandals, one after another, but have any of them really stuck around?)

Foreign/military failure: The incumbent administration suffers no major failure in foreign or military affairs. Maybe true? (on the one hand, Iran didn’t retaliate when we killed their general, but on the other hand we retreated out of Syria, let thousands of ISIS fighters go, and aided the Turks in a Kurdish genocide. The tit-for-tat sanctions against China threatened to crash the global economy, but then the coronavirus came in and did that all by itself, so it’s unclear whether we’ve “failed” or simply “not succeeded”)

Foreign/military success: The incumbent administration achieves a major success in foreign or military affairs. Maybe false? (for the same reason as above, it is hard to judge what is or isn’t a success. USMCA is unpopular and small potatoes. The North Korean talks are all show with no substance; Kim will never get rid of his nukes. We’re still caught up in W’s endless wars, and I don’t see an end in sight, so I’d say this is definitely not a success).

Incumbent charisma: The incumbent party candidate is charismatic or a national hero. FALSE (Trump is a hero among Republicans, but reviled among everyone else. He has never had majority approval, and will not go down as one of the universally beloved presidents like Washington, Lincoln, or the Roosevelts)

Challenger charisma: The challenging party candidate is not charismatic or a national hero. TRUE (Joe Biden is the Walter Mondale of Al Gores. Republicans hate him, and only half of Democrats really like him. He’s old and senile, he keeps making gaffe after gaffe after gaffe, and doesn’t seem to know how the game is played anymore. Someone needs to find Grampa a nice home so he can retire and talk to his nurse about how he used to get into fist fights with ne’er-do-wells, “buncha malarkey, I tell ya”)

Lets review the scores, from Best to Worst

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

Almost certainly false

Probably false

Maybe false

Unclear

Maybe

Maybe true

True as of right now

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

Incumbent Trumps needs 8 true to win. Challenger Biden needs 6 false to win.

Biden definitely has 3, with 3 teetering towards him, which is a good sign. He could even flip the unclear key in his favor if the economy continues to tank.

As it stands, both parties seem to have 6 keys each, which predicts that the challenging party will win the election. The scandal key is tentatively in Biden’s favor, as are the social unrest and military success keys. This could change in the coming months if Trump does something erratic like assassinating the Ayatollah and declaring that a victory (which would lead to an endless oil war with Iran; it’d be 2003 all over again). Trumps needs to flip more keys than Biden does, so he’s going into it with as disadvantage, perhaps the only time in his life he has ever not had an advantage.

But then again, there’s always the possibility that it could be a 2000/2016 repeat, where Biden wins the popular vote but Trump ekes by with the electoral college victory yet again. This model doesn’t take that into account because the popular vote winner almost always wins the EC too.

Trump is not more popular today than he was 4 years ago. He’s never had majority approval. While his base loves him more now than ever, they represent a minority of voters, and pretty much everyone else hates him. Anyone who was on the fence in 2016 is definitively over the fence in 2020. If he “wins,” it’s not going to be a 1972/1984 blowout, that’s just not gonna happen, too many states hate him too much. It will be very close; I will not rule out the possibility of a 269-269 tie in the electoral college, triggering a contingent election where the House of Representatives has to pick the president. Democrats have a majority in the House right now, but in contingent elections they don’t vote as 435 individuals, they vote as 50 state blocs; even though there are more Democrats than Republicans, they’re packed together into as few states as possible, giving Republicans over 26 stateside majorities, enough to ensure they would pick Trump in a contingent election.

It’s a bullshit system, and I pray it doesn’t come to that.

#allan lichtman#lichtman#13 keys to the white house#13 keys#politics#political#2020 election#election prediction#prediction#2020 predictions#election#electoral college#popular vote#joe biden#donald trump#biden#trump#fuck trump#fuck republicans#fuck conservatives#civil war#1972#1984#2000#2016#2020#true or false

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Democratic debate analysis

I’ve read the transcripts. I read the fact-checkers’ analysis. I have ranked them.

Due to the size of the field, I’ll be splitting my analysis into four groups. This first one will be the Please Do Not Make Me Vote For Them group:

Ryan, Hickenlooper, Williamson, Bennet, Delaney, O’Rourke, and Biden.

Under the break, I’ll be analyzing their debate performance, how effectively they represented themselves on the issues, and how much I hate them, in reverse order of preference. Let’s begin.

20) Biden

Biden is so… so out of touch. Even the moderators asked if he was out of touch, and when the moderators of a debate you’re participating in think you don’t know what you’re talking about? For a career politician, that has got to hurt. Frankly, they were right. Biden thinks that the reason people can’t pay their student loans without sacrificing everything else they want to do with their lives is because we’re not earning more than $25k a year, that freezing payments and interest until the graduated student crosses that threshold would magically make everything ok. If he were right, there’d be no Fight for 15. A $15 minimum wage, assuming full time hours, is more than $30k per year.

His response to accusations of racism was to point to his “black friend,” former President Obama, which… dude. You’ve got to know better than that by now. Please tell me you know having been the first and only black President’s VP does not immediately absolve you of being an old white guy who worked with Southern Segregationists against integrating schools.

His entire platform seems to be “remember when I was a senator/the vice president? Wasn’t I great, back when I had ideas and did things?” and I gotta say, No. No, you weren’t that great, Joe. Even his closing comments were lackluster, talking about “restoring the soul of America,” and “restoring the dignity of the middle class,” and “building national unity.” His answers to simple questions were, frankly, terrible.

Joe, what would you do, day one, if you knew you’d only be able to accomplish one thing with your Presidency? Thanks for asking, I’d BEAT DONALD TRUMP! Joe. Joe, that’s how you get to Day One. Unless you mean “grab him by the collar, haul him out on the White House lawn, and bludgeon him with heavy objects,” you’re not answering the question.

Joe, which one country do you think we need to repair diplomatic ties with most? NATO! Joe. Joe, NATO is more than one country. I just… *sigh*

To his credit, Biden trotted out many of the same old campaign promises Democrats have been making for as long as I can remember. Closing tax loopholes, universal pre-K and increased educational funding, let Medicare negotiate prescription drug prices. These are tried and true campaign promises because they’re things we can all generally agree we want. But they’re old, a lot like Biden. They’re not the bold solutions we need. His newer ideas all sound pretty moderate and old, too: free community college (not 4 year public university), creating a public option for healthcare so people can choose between insurance companies and Medicare, rejoining the Paris Climate Accord, and instituting national gun buybacks. His suggestion of requiring all guns to have a biometric safety is also a vague gesture in the direction of a solution.

Biden is too old, too timid, and too arrogant to understand that he’s got nothing to offer in an election where Millenials and Gen Z are going to be the largest portion of the electorate.

19) O’Rourke

Beto, or as I like to call him, Captain Wrongerpants, got off to a roaring start by giving a non-answer in two languages. This incredible display of pandering, and wasting precious time, made him seem pretentious and obnoxious in twice the number of languages most politicians aspire to.

Possibly more than any other candidate, O’Rourke completely failed to answer any question he was asked. He presented a few good ideas, saying that he sees climate change as the most pressing threat to America and calling for an end to fossil fuel use. He supports universal background checks and reinstating the assault weapons ban. He wants comprehensive immigration reform, to reunite families separated by the Trump administration, and to increase the corporate tax rate.

Unfortunately, he wants to increase the tax rate from the new-for-2019 level of 21% to a lower-than-2018 28%. He wants immigration reform to protect asylum seekers, but thinks other immigrants should “follow our laws” and makes no guarantee to decriminalize undocumented border crossings. Like Biden, he supports healthcare “choice,” meaning that for-profit healthcare would continue in this country until everyone, in every city, state, county, and cave, can be convinced that insurance companies don’t care about them.

In short, O’Rourke reaches for relevance and relatability, and lands in pretension and centrism.

18) Delaney

John Delaney is the first candidate on my list to have been caught in a bald-faced lie by Politifact. Good job, John. His lie, by the way, was about Medicare for All. He claimed that the bill currently before Congress required that Medicare pay rates stay at the current levels, and that if every hospital in America had been paid at Medicare levels for all services, every hospital would have to close. The truth? The Medicare for All bill does not require that pay rates stay at current levels, and even if it did no one knows what effect that would have on the country’s hospitals. There is no data to support his assertion, even if he was right about the terms of the legislation being considered.

Unsurprisingly, John is another healthcare “choice” advocate. I think I’ve said enough about why this position doesn’t fly for me, so I won’t rehash it again.

In a discussion of family separation, he interjected that his grandfather was also a victim of family separation, which must make him feel so relevant. He also referred to company owners as “job creators,” a lovely little conservative talking point, and claimed that America “saved the world,” in some vague appeal to American Exceptionalism. He also agrees with Nancy Pelosi about not pursuing impeachment proceedings.

On the “I don’t hate him quite as much as Beto and Biden” front, he’s in favor of tax breaks for the middle class, increasing the minimum wage, funding education, family leave policies, a carbon tax (which he imagines would fund a tax dividend paid to individual citizens, rather than, I don’t know, paying for green infrastructure development?), thinks China is our biggest geopolitical threat, and is scared of nuclear weapons (a very sane, reasonable position, really).

If you want to pick a candidate based on who your moderately conservative uncle will yell about least if they win the White House, Delaney might be your guy. If you want to pick a candidate based on issues like student loan debt and healthcare, keep looking.

17) Bennet

I had never heard of Michael Bennet before the debates. In fact, I just Googled him to find out his first name. After the debates, though? You guessed it: I hate him.

His closing statement was an appeal to the American Dream. He thinks there are too many people in America to make a single payer healthcare system work. Asked to identify one country to prioritize diplomatic repairs with, he named two continents. And he believes the world is looking to America for leadership.

However, he did rate higher than three whole candidates, and here’s why:

He supports a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. He wants to end gerrymandering and overturn Citizens United. He wants to expand voting rights and electoral accessibility. He considers climate change and Russia to be the biggest threats to America, and he didn’t use any obvious racist dogwhistles. He’s from Colorado, so he’s kinda proud of the state’s marijuana legalization and reproductive health policies, but he’s way too quick to see partnership with private businesses as the ideal path forward.

16) Williamson

Oh man. Marianne Williamson. I almost threw something every time she opened her mouth. She is like a walking, talking, uninformed Tumblr guilt trip post. At a nationally televised debate, she asked why no one was talking about… something. I didn’t write it down in my notes because I would have had to gouge out my own eyes if I had. According to Google, she is a self-help speaker and that explains So Much.

In her closing statement, Williamson claimed that she would be the candidate to beat Trump, not because she has any plans, but because she will harness love to counter the fear that fuels Trump’s campaign. I am not making this up and I wish I was.

She claimed that Americans have more chronic health issues than anywhere else in the world, and attributed this to all sorts of factors, starting with diet and chemical contamination and extending, I assume, to solar activity and Bigfoot. According to Politifact, the only American demographic with a higher incidence of chronic illness than other countries is senior citizens, and I’m going to guess that has a lot more to do with our crappy healthcare system than it does a lack of detox teas.

When asked what policy she would enact if she could only get one, she said that on her first day in the White House she’d call the Prime Minister of New Zealand and tell her that New Zealand is not the best place in the world to raise a child, America is.

When asked which one country she’d make a diplomatic priority, she said “European leaders.”

By now you must be wondering how she rated higher than the bottom four, and I can sum it up in eight words: She supports reparations and the Green New Deal.

Please, please do not make me vote for Marianne Williamson.

15) Hickenlooper

John Hickenlooper is the former Governor of Colorado, and proudly takes credit for everything good that has ever happened in the state. He is also proud of being a small business owner, a statement that makes me immediately suspicious of any politician.

To his credit, he supports “police diversity,” a charmingly non-specific term that could mean one gay Latine nonbinary single parent in an otherwise entirely white male department, or could mean he wants the demographics of the police force to match the demographics of the population being policed. He also considers climate change a serious threat, and China. The best thing he said all night? He supports civilian oversight of police, a policy which has improved police relations with citizens.

Sounds pretty good, right? Wrong.

He also supports ICE “reform,” as if there is anything redeemable about that agency, and thinks that the worst thing the eventual Democratic candidate could do is allow their name to be connected to anything socialist. He said it twice, it wasn’t an accident.

14) Ryan

That brings us to the last of the worst, Tim Ryan. Tim here cannot stop using conservative dogwhistles, like talking about “coastal elites,” and saying that acknowledging differences between people is divisive. He is a basic ass white boy in the worst, most boring sense.

He wants to bring about a green tech boom, supports decriminalizing border crossing, supports gun reform, and thinks China is a serious threat to America. He also thinks that, in addition to dealing with the issues that allow school shootings to happen, we need to address the trauma kids are growing up with as a result. Unfortunately, he thinks that school shooters are misunderstood victims of bullying.

His confrontation with Tulsi Gabbard was very instructive and possibly the most damning exchange all night. He mis-identified the terrorists who attacked the World Trade Center as being “the Taliban” (they were Al-Qaeda) and said that our military forces have to “stay engaged” for… stability? I guess? As a veteran, I’m with Tulsi on this one: that’s not acceptable.

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

The early signs are not auspicious. Almost lost in the welter of top economic jobs leaked to the Times, Post, and Wall Street Journal by the transition staff on Sunday (the Prospect reported most of these earlier in the week) was an unfamiliar name, Adewale Adeyemo, known as Wally. He is to be Yellen’s deputy Treasury secretary.

Who is Wally Adeyemo? If he is typical of what’s coming, we can expect that what the Biden team gives progressives with one hand, they may take away with the other.

Adeyemo, 39, came to the U.S. as a child from Nigeria with his parents. He excelled in school, graduating from the University of California and then Yale Law School. While at Yale, he worked in the Obama campaign. He joined the administration while still in his late twenties, working for then–Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner.

Among the red flags for progressives is the fact that after leaving government, Adeyemo followed a well-worn path of Obama alums seeking to cash in, and went to Wall Street. And not just anywhere on Wall Street—he went to BlackRock, the world’s largest financial firm with $7 trillion under management, where he served as a political adviser and for a time as chief of staff to CEO Larry Fink.

So Adeyemo begins with a conflict of interest, since Fink’s top priority is to prevent BlackRock from being designated as a systemically important financial institution (SIFI), which would subject it to a higher level of regulatory scrutiny. The Treasury is the key player on this decision, and scores of others that affect BlackRock’s business model.

And there are more red flags. Before joining the Obama administration, Adeyemo worked at the Hamilton Project. That’s the outfit housed at Brookings and created and underwritten by Robert Rubin to promote a very centrist and Wall Street–friendly brand of watered-down liberalism.

Adeyemo subsequently worked for Treasury Secretary Jack Lew as his deputy chief of staff in 2015. Lew is another Rubin protégé. In between Lew’s two stints in government (Clinton, then Obama), Lew was chief operating officer at Citigroup, where Rubin was a top executive.

(Why does Rubin turn up just about everywhere in launching and promoting the careers of the wrong kind of Democrat? That’s not just a rhetorical question but a deeply structural one, if you want to understand the corruption and political failures of the Democratic Party.)

Following his post at Treasury, Adeyemo took a version of the key international economics post once held by Rubin protégé Mike Froman, serving on both the NSC and the NEC as the international economics chief. He was a key negotiator on the late and little lamented Trans-Pacific Partnership, the brainchild of Froman, and the quintessence of the corporate brand of “free trade” deal.

From there he went to BlackRock. After two years at Black Rock, Adeyemo became the first president of the Obama Foundation.

His trajectory offers a perfect rendition of the Washington–Wall Street revolving door. Can we imagine Adeyemo urging tougher regulation of BlackRock?