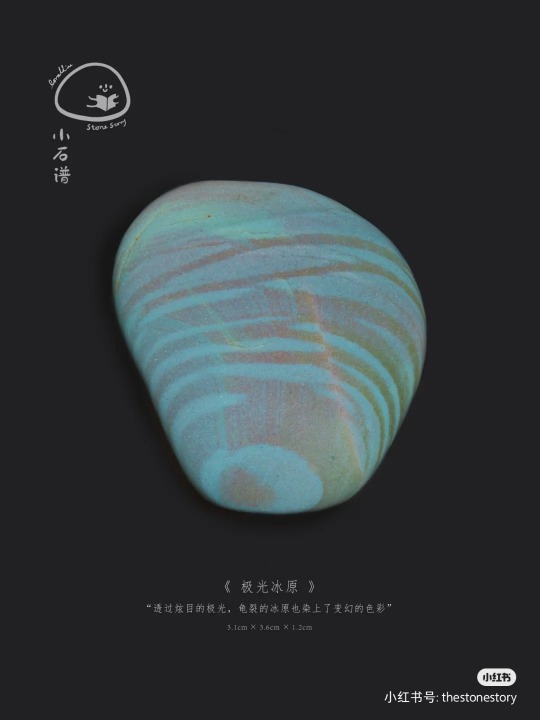

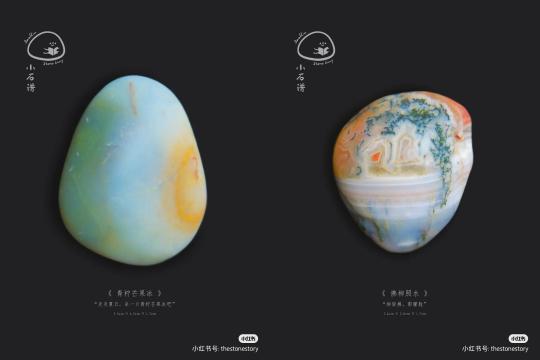

#ninth aurora ice field

Photo

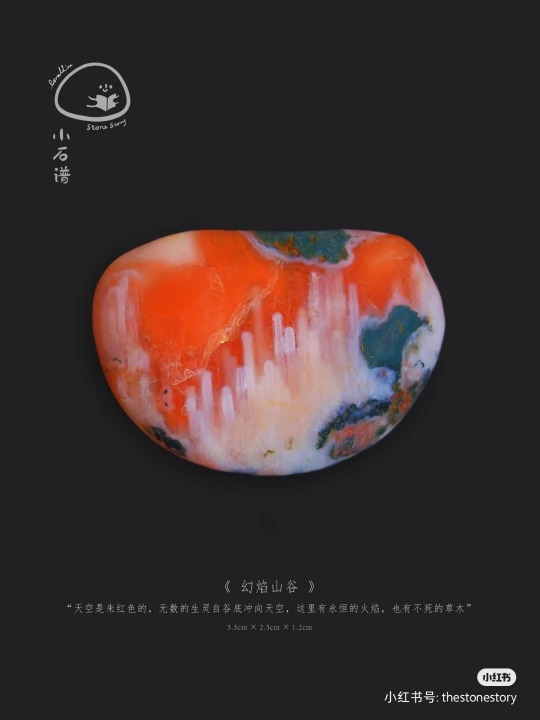

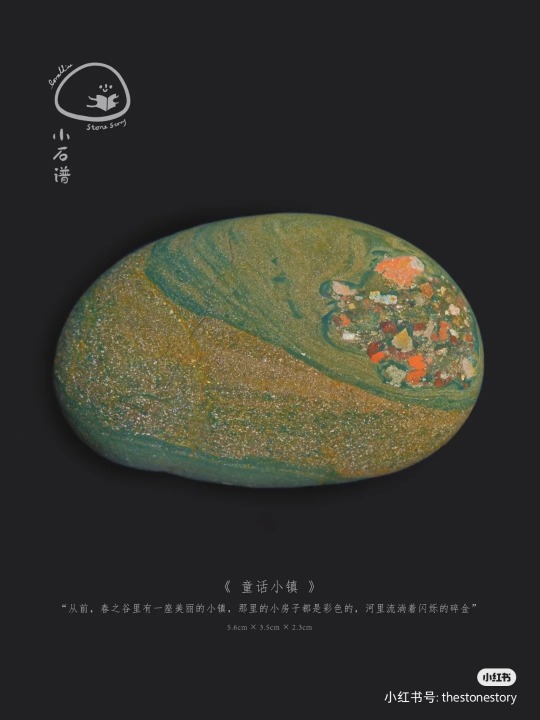

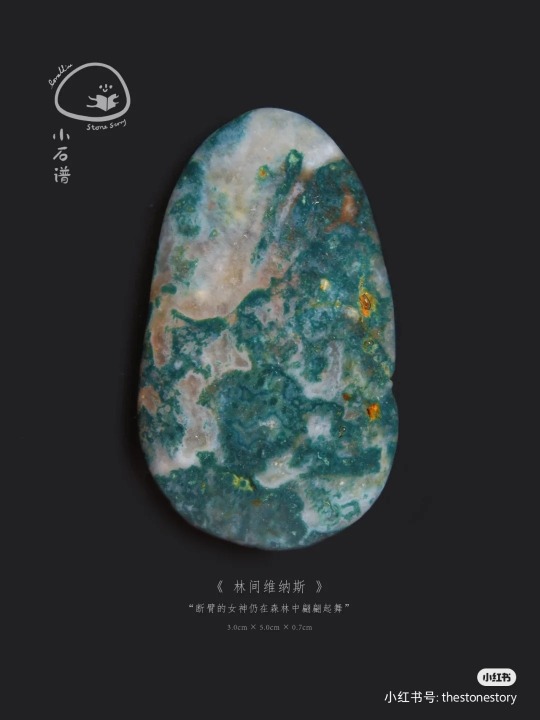

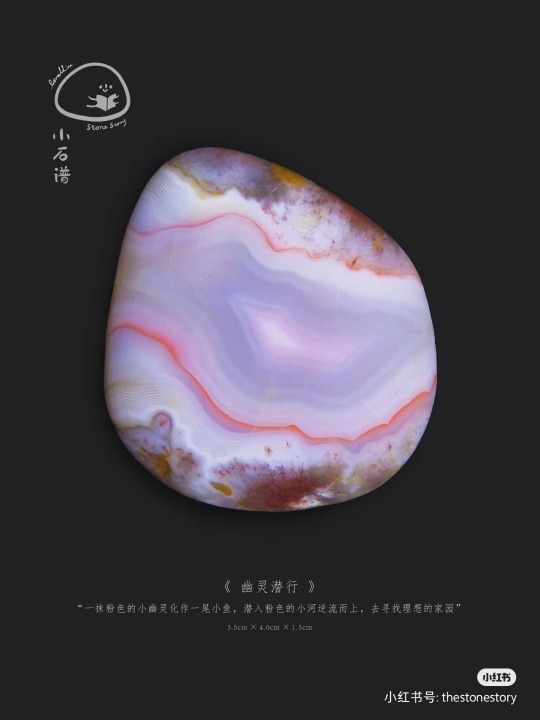

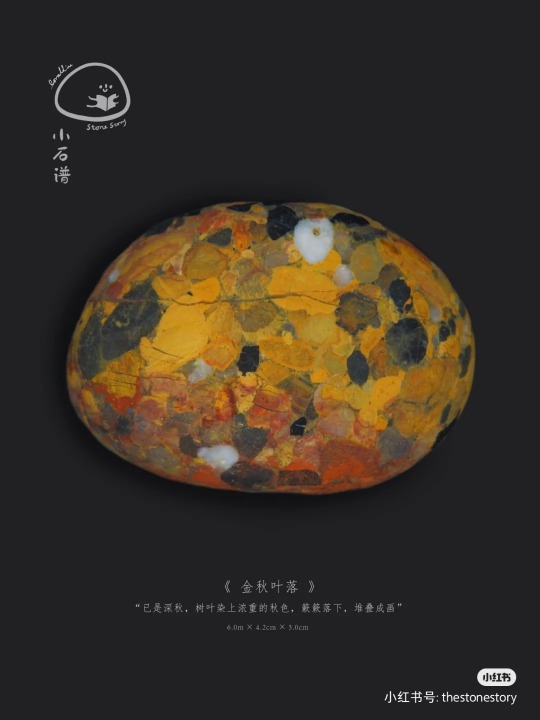

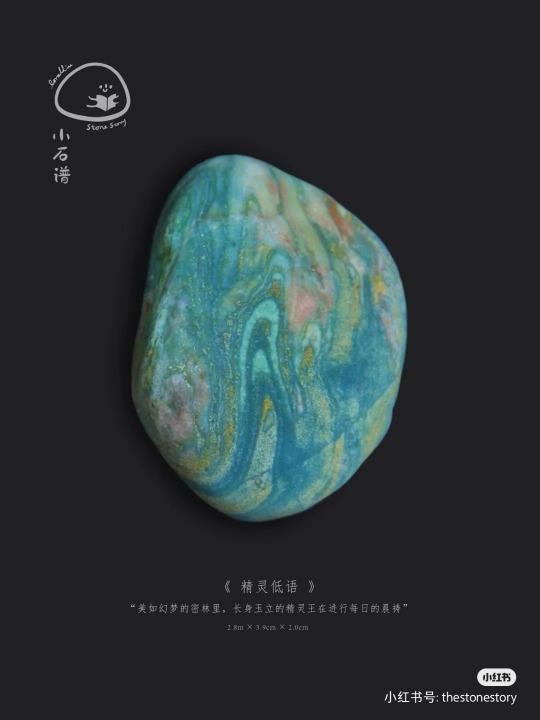

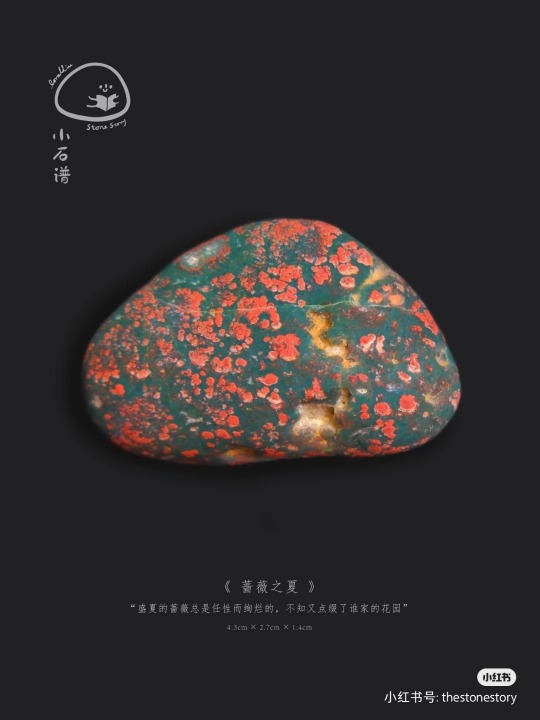

various stones with names by thestonestory

#china#fun#miscellaneous#stones#aesthetic#these names are so pretty#e.g. the first one Phantom Flame Valley#fourth Wraith stealth?#seventh The sea of clouds reflects the rosy clouds#ninth aurora ice field#tenth summer of rambler#sixth whisper of elves#mineral#rocks

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

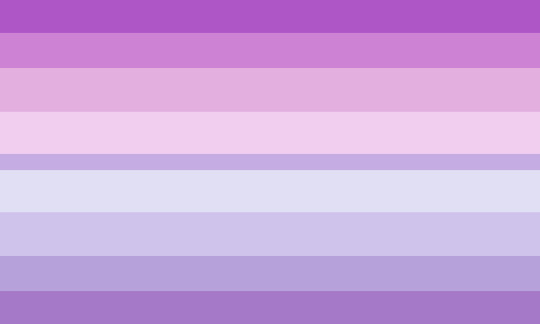

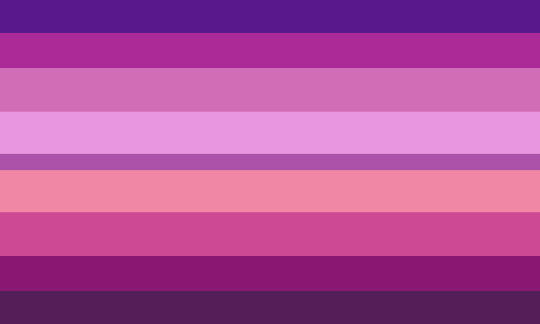

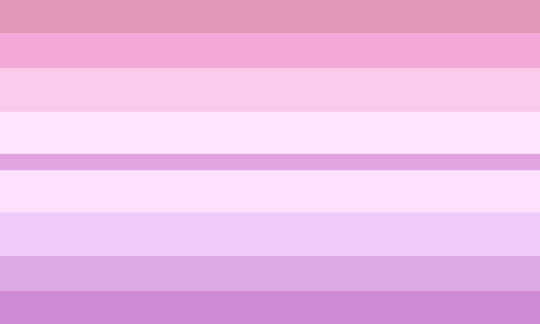

flag id: six flags with 9 stripes, with the second and eighth being smaller than the others, the first and ninth smaller than those, and the fifth the smallest.

the top left flag's stripes are blue-black, dark indigo, purple, golden yellow, dark pink, cream, light yellow-green, faded purple, and dark purple. the top right flag's stripes are blue-black, dark purple, medium dark faded purple, soft purple, dark faded indigo, bright purple, purple, medium dark pink, and very dark teal.

the middle left flag's stripes are faded purple, soft pink-purple, pale pink, very light pink, pale indigo, very light blue, light blue, soft indigo, and faded indigo. the middle right flag's stripes are dark indigo, medium dark pink, faded pink, light pink, medium dark faded purple-pink, light pink-red, pink, dark pink, and very dark purple.

the bottom left flag's stripes are dull light pink, very light pink, pale pink, pinkish-white, light faded pink, purplish-white, pale purple, very light purple, and dull light purple. the bottom right flag's stripes are extremely dark indigo, very dark purple-pink, dark faded pink, golden yellow, faded indigo, pale green, dull indigo, dark faded blue, and very dark indigo. end id.

banner id: a 1600x200 teal banner with the words ‘please read my dni before interacting. those on my / dni may still use my terms, so do not recoin them.’ in large white text in the center. the text takes up two lines, split at the slash. end id.

amethystcolauric | purplecolauric

lilacolauric | orchidcolauric

lavendercolauric | mauvecolauric

amethystcolauric: a colorgender related to the color amethyst, earrings, violet corts, parades, gemstones, insect wings, grape bushels, and outer space

purplecolauric: a colorgender related to the color purple, geodes, club lights, ferris wheels, sunglasses, hummingbirds, eyeshadow, and outer space

lilacolauric: a colorgender related to the color lilac, tulips, lavender cookies, glitter, watercolors, heart lockets, pressed flowers, and twilight

orchidcolauric: a colorgender related to the color orchid, blooming flowers, butterflies, sunsets, text messages, hair dye, auroras, and neon lights

lavendercolauric: a colorgender related to the color lavender, rock candy, daydreams, chapstick, ribbons in hair, crayons, flower fields, and sleepovers

mauvecolauric: a colorgender related to the color indigo, shooting stars, grapevines, velvet curtains, evening skies, mirrors, tarot cards, and bookmarks

[pt: amethystcolauric: a colorgender related to the color amethyst, earrings, violet corts, parades, gemstones, insect wings, grape bushels, and outer space

purplecolauric: a colorgender related to the color purple, geodes, club lights, ferris wheels, sunglasses, hummingbirds, eyeshadow, and outer space

lilacolauric: a colorgender related to the color lilac, tulips, lavender cookies, glitter, watercolors, heart lockets, pressed flowers, and twilight

orchidcolauric: a colorgender related to the color orchid, blooming flowers, butterflies, sunsets, text messages, hair dye, auroras, and neon lights

lavendercolauric: a colorgender related to the color lavender, rock candy, daydreams, chapstick, ribbons in hair, crayons, flower fields, and sleepovers

mauvecolauric: a colorgender related to the color indigo, shooting stars, grapevines, velvet curtains, evening skies, mirrors, tarot cards, and bookmarks. end pt]

third set of colorgenders based on the results of this 'what color is your aura?' uquiz for anon!

these are in the colorgender flag format with the aura color from the uquiz as the center stripe and colors inspired by the listed things as the rest of the stripes. the terms are the aura color, 'col' from 'color, 'aur' from 'aura', + 'ic'!

tags: @radiomogai, @colorgendered | dni link

#amethystcolauric#purplecolauric#lilacolauric#orchidcolauric#lavendercolauric#mauvecolauric#colauric#colorgender#aesthetigender#my flags#my terms#new flag#new term#mogai flag#mogai term#mogai#long post

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is in your itinerary?

Aries Ninth House/Mars in the Ninth House

Under the Australian sun, you will indulge in the ancient sands and mystical waters. You’ll stand and stare into the Indian ocean, peer into reefs of sharks and stingrays, look onto endless roads through the red desert, listen to the stories of dreamtime, sense old energies, old spirits, and fall in love with the down under.

Taurus Ninth House/Venus in the Ninth House

You’ll find luxury in France, where good food and wine, fashion, and art is celebrated. You’ll spend your mornings in Parisian cafés, your afternoons in trendy boutiques, and your nights in sweetly scented vineyards. You’ll ponder the meaning of beauty as you stand in cathedrals or in front of hundred year old paintings.

Gemini Ninth House/Mercury in the Ninth House

Beside the Atlantic Ocean, grey skyscrapers stand over the noisy, busy city of New York. You’ll be lured in by every “World’s Best,” dance at the most exclusive clubs, and stand at the top of the tallest towers. You’ll find beauty in this city’s rugged imperfection and vibrance with its people.

Cancer Ninth House/Moon in the Ninth House

Home of the world’s roots, you’ll find yourself tracing back to ancient lands in Botswana. You’ll find yourself reflecting over a lively delta of birds, elephants, and hippos as the sun sets and the moon begins to greet you. You’ll raise your own sun, a campfire, where stories can be told. Listen to what nurtured this land for thousands of years and what traditions have been sacredly preserved.

Leo Ninth House/Sun in the Ninth House

The Polynesian triangle that holds islands of beauty afloat, you will discover vibrant greens coving pools of blue. Rigid, hot rocks mantel ancient statues. Plump fruit hanging from every tree. Sunsets that are celebrated with dance. You’ll forget about the Western world on these happy, secret islands.

Virgo Ninth House/Vesta in the Ninth House

The hidden gems that lie within India, such as the Ajanta Caves, reveal elaborate religious history. Peregrinating the whole country, you’ll discover intricate architecture, diverse culture, remote beaches, and rolling hills. Realign with what matters in the Parvati valley with mountain views and spiced tea.

Libra Ninth House/Juno in the Ninth House

Far from the capital, Tokyo, you’ll find peace and simplicity in rural Japan. You’ll wander through forests greeted by torii and guarded by shrines. This island accentuates the beauty in ceremony and the comfort of a familiar meal. During a week in spring, you’ll drink underneath a cherry tree and witness the wind carry its petals.

Scorpio Ninth House/Pluto in the Ninth House

In the deserts of Jordan, you’ll float in the Dead Sea, explore sandstone ruins, and walk with camels through dunes and canyons. You’ll feel the energy of ancient traders and travels who once navigated through this country. Sunsets here paint the sky pink over the orange Petra.

Sagittarius Ninth House/Jupiter in the Ninth House

The old worlds that sit at the Mediterranean Sea who fascinate the endlessly curious. Where philosophers pondered in Athens, where pharaohs reigned along the Nile, where Gods blessed the lands of Turkey and Israel. You’ll embrace the ancient walls and scriptures, the magickal textiles and wares, and the religiousness, culture, and knowledge.

Capricorn Ninth House/Saturn in the Ninth House

In the chill of Scandinavian air, you will look up at auroras that dance over Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Beneath your feet is volcanic earth, fresh snow, and the footprints of reindeer herders. You’ll feel warmed by valleys, the traditional art, the culture, and the sound of ancient joik.

Aquarius Ninth House/Uranus in the Ninth House

Within the other worldly landscapes of Russia, you’ll find solitude and rediscover how large this planet is. You’ll be in awe at the active volcanos in Kamchatka, the endless fields of ice around Siberia, and the beautiful architecture in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The geographical diversity of this alien world is yet to be known.

Pisces Ninth House/Neptune in the Ninth House

In the haunting and mysterious Northern Canada lies untouched or forgotten places. Fragrant pine trees conceal its silent world. You’ll find secret roads that lead to creeks, rivers, falls, relics, and old, forgotten mine towns. The very North faces the blackness of the Arctic Ocean. A lonely sight that makes you wonder if anyone else has stood where you have.

© 2021 – @star-astrology

372 notes

·

View notes

Text

NASA Juno Takes First Images of Jovian Moon Ganymede's North Pole

NASA - JUNO Mission logo.

July 23, 2020

Infrared images from Juno provide the first glimpse of Ganymede's icy north pole.

Image above: These images the JIRAM instrument aboard NASA's Juno spacecraft took on Dec. 26, 2019, provide the first infrared mapping of Ganymede's northern frontier. Frozen water molecules detected at both poles have no appreciable order to their arrangement and a different infrared signature than ice at the equator. Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM.

On its way inbound for a Dec. 26, 2019, flyby of Jupiter, NASA's Juno spacecraft flew in the proximity of the north pole of the ninth-largest object in the solar system, the moon Ganymede. The infrared imagery collected by the spacecraft's Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument provides the first infrared mapping of the massive moon's northern frontier.

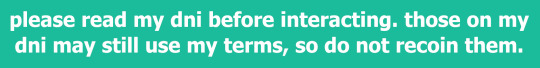

The only moon in the solar system that is larger than the planet Mercury, Ganymede consists primarily of water ice. Its composition contains fundamental clues for understanding the evolution of the 79 Jovian moons from the time of their formation to today.

Ganymede is also the only moon in the solar system with its own magnetic field. On Earth, the magnetic field provides a pathway for plasma (charged particles from the Sun) to enter our atmosphere and create aurora. As Ganymede has no atmosphere to impede their progress, the surface at its poles is constantly being bombarded by plasma from Jupiter's gigantic magnetosphere. The bombardment has a dramatic effect on Ganymede's ice.

"The JIRAM data show the ice at and surrounding Ganymede's north pole has been modified by the precipitation of plasma," said Alessandro Mura, a Juno co-investigator at the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome. "It is a phenomenon that we have been able to learn about for the first time with Juno because we are able to see the north pole in its entirety."

Image above: The north pole of Ganymede can be seen in center of this annotated image taken by the JIRAM infrared imager aboard NASA's Juno spacecraft on Dec. 26, 2019. The thick line is 0-degrees longitude. Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM.

The ice near both poles of the moon is amorphous. This is because charged particles follow the moon's magnetic field lines to the poles, where they impact, wreaking havoc on the ice there, preventing it from having an ordered (or crystalline) structure. In fact, frozen water molecules detected at both poles have no appreciable order to their arrangement, and the amorphous ice has a different infrared signature than the crystalline ice found at Ganymede's equator.

"These data are another example of the great science Juno is capable of when observing the moons of Jupiter," said Giuseppe Sindoni, program manager of the JIRAM instrument for the Italian Space Agency.

JIRAM was designed to capture the infrared light emerging from deep inside Jupiter, probing the weather layer down to 30 to 45 miles (50 to 70 kilometers) below Jupiter's cloud tops. But the instrument can also be used to study the moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto (also known collectively as the Galilean moons for their discoverer, Galileo).

Juno spacecraft orbiting Jupiter. Animation Credit: NASA

Knowing the top of Ganymede would be within view of Juno on Dec. 26 flyby of Jupiter, the mission team programmed the spacecraft to turn so instruments like JIRAM could see Ganymede's surface. At the time surrounding its closest approach of Ganymede - at about 62,000 miles (100,000 kilometers) - JIRAM collected 300 infrared images of the surface, with a spatial resolution of 14 miles (23 kilometers) per pixel.

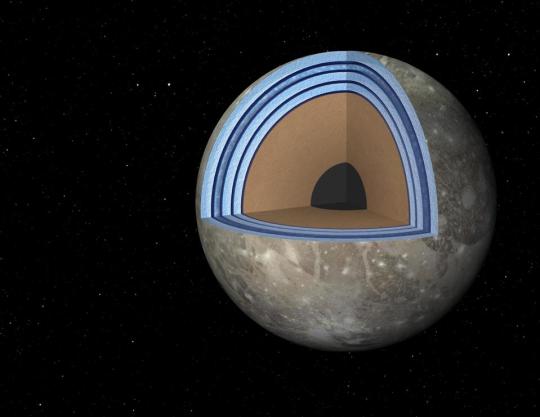

The secrets of Jupiter's largest moon revealed by Juno and JIRAM will benefit the next mission to the icy world. The ESA (European Space Agency) JUpiter ICy moons Explorer mission is scheduled to begin a 3 1/2-year exploration of Jupiter's giant magnetosphere, turbulent atmosphere, and its icy moons Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa beginning in 2030. NASA is providing an Ultraviolet Spectrograph instrument, along with also subsystems and components for two additional instruments: the Particle Environment Package and the Radar for Icy Moon Exploration experiment.

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA's New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Italian Space Agency (ASI) contributed the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft.

More information about Juno is available at:

https://www.nasa.gov/juno

https://www.missionjuno.swri.edu

More information on Jupiter is at:

https://www.nasa.gov/jupiter

The public can follow the mission on Facebook and Twitter at:

https://www.facebook.com/NASAJuno

https://www.twitter.com/NASAJuno

Images (mentioned), Animation (mentioned), Text, Credits: NASA/Alana Johnson/Grey Hautaluoma/INAF - National Institute for Astrophysics/Marco Galliani/Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio/Deb Schmid/JPL/DC Agle.

Greetings, Orbiter.ch

Full article

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Juno Takes First Images of Jovian Moon Ganymede's North Pole Infrared images from Juno provide the first glimpse of Ganymede's icy north pole. On its way inbound for a Dec. 26, 2019, flyby of Jupiter, NASA's Juno spacecraft flew in the proximity of the north pole of the ninth-largest object in the solar system, the moon Ganymede. The infrared imagery collected by the spacecraft's Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument provides the first infrared mapping of the massive moon's northern frontier. Larger than the planet Mercury, Ganymede consists primarily of water ice. Its composition contains fundamental clues for understanding the evolution of the 79 Jovian moons from the time of their formation to today. Ganymede is also the only moon in the solar system with its own magnetic field. On Earth, the magnetic field provides a pathway for plasma (charged particles from the Sun) to enter our atmosphere and create aurora. As Ganymede has no atmosphere to impede their progress, the surface at its poles is constantly being bombarded by plasma from Jupiter's gigantic magnetosphere. The bombardment has a dramatic effect on Ganymede's ice. "The JIRAM data show the ice at and surrounding Ganymede's north pole has been modified by the precipitation of plasma," said Alessandro Mura, a Juno co-investigator at the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome. "It is a phenomenon that we have been able to learn about for the first time with Juno because we are able to see the north pole in its entirety." The ice near both poles of the moon is amorphous. This is because charged particles follow the moon's magnetic field lines to the poles, where they impact, wreaking havoc on the ice there, preventing it from having an ordered (or crystalline) structure. In fact, frozen water molecules detected at both poles have no appreciable order to their arrangement, and the amorphous ice has a different infrared signature than the crystalline ice found at Ganymede's equator. "These data are another example of the great science Juno is capable of when observing the moons of Jupiter," said Giuseppe Sindoni, program manager of the JIRAM instrument for the Italian Space Agency. JIRAM was designed to capture the infrared light emerging from deep inside Jupiter, probing the weather layer down to 30 to 45 miles (50 to 70 kilometers) below Jupiter's cloud tops. But the instrument can also be used to study the moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto (also known collectively as the Galilean moons for their discoverer, Galileo). Knowing the top of Ganymede would be within view of Juno on Dec. 26 flyby of Jupiter, the mission team programmed the spacecraft to turn so instruments like JIRAM could see Ganymede's surface. At the time surrounding its closest approach of Ganymede - at about 62,000 miles (100,000 kilometers) - JIRAM collected 300 infrared images of the surface, with a spatial resolution of 14 miles (23 kilometers) per pixel. The secrets of Jupiter's largest moon revealed by Juno and JIRAM will benefit the next mission to the icy world. The ESA (European Space Agency) JUpiter ICy moons Explorer mission is scheduled to begin a 3 1/2-year exploration of Jupiter's giant magnetosphere, turbulent atmosphere, and its icy moons Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa beginning in 2030. NASA is providing an Ultraviolet Spectrograph instrument, along with also subsystems and components for two additional instruments: the Particle Environment Package and the Radar for Icy Moon Exploration experiment. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA's New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Italian Space Agency (ASI) contributed the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft. TOP IMAGE....These images the JIRAM instrument aboard NASA's Juno spacecraft took on Dec. 26, 2019, provide the first infrared mapping of Ganymede's northern frontier. Frozen water molecules detected at both poles have no appreciable order to their arrangement and a different infrared signature than ice at the equator. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM LOWER IMAGE....The north pole of Ganymede can be seen in center of this annotated image taken by the JIRAM infrared imager aboard NASA's Juno spacecraft on Dec. 26, 2019. The thick line is 0-degrees longitude. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

Hubble finds first evidence of water vapour at Jupiter’s moon Ganymede by European Space Agency

Via Flickr:

Astronomers have used archival datasets from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope to reveal the first evidence for water vapour in the atmosphere of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the result of the thermal escape of water vapour from the moon’s icy surface. Jupiter’s moon Ganymede is the largest moon — and the ninth-largest object — in the Solar System. It may hold more water than all of Earth's oceans, but temperatures there are so cold that water on the surface freezes and the ocean lies roughly 160 kilometres below the crust. Nevertheless, where there is water there could be life as we know it. Identifying liquid water on other worlds is crucial in the search for habitable planets beyond Earth. And now, for the first time, evidence has been found for a sublimated water atmosphere on the icy moon Ganymede. In 1998, Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) took the first ultraviolet (UV) pictures of Ganymede, which revealed a particular pattern in the observed emissions from the moon’s atmosphere. The moon displays auroral bands that are somewhat similar to the auroral ovals observed on Earth and other planets with magnetic fields. These images were therefore illustrative evidence that Ganymede has a permanent magnetic field. The similarities between the two ultraviolet observations were explained by the presence of molecular oxygen, O2. The differences were explained at the time by the presence of atomic oxygen, O, which produces a signal that affects one UV colour more than the other. As part of a large observing programme to support NASA’s Juno mission in 2018, Lorenz Roth, of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden, led a team that set out to capture UV spectra of Ganymede with Hubble’s Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) instrument to measure the amount of atomic oxygen. They carried out a combined analysis of new spectra taken in 2018 with the COS and archival images from the STIS instrument from 1998 and 2010. To their surprise, and in contrast to the original interpretations of the data from 1998, they discovered there was hardly any atomic oxygen in Ganymede's atmosphere. This means there must be another explanation for the apparent differences between the UV aurora images. The explanation was then uncovered by Roth and his team in the relative distribution of the aurorae in the two images. Ganymede's surface temperature varies strongly throughout the day, and around noon near the equator it may become sufficiently warm that the icy surface releases some small amounts of water molecules. In fact, the perceived differences between the UV images are directly correlated with where water would be expected in the moon’s atmosphere. “Initially only the O2 had been observed,” explained Roth. “This is produced when charged particles erode the ice surface. The water vapour that we have now measured originates from ice sublimation caused by the thermal escape of H2O vapour from warm icy regions.” This finding adds anticipation to ESA’s upcoming JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (Juice) mission — the first large-class mission in ESA's Cosmic Vision 2015–2025 programme. Planned for launch in 2022 and arrival at Jupiter in 2029, it will spend at least three years making detailed observations of Jupiter and three of its largest moons, with particular emphasis on Ganymede as a planetary body and potential habitable world. Ganymede was identified for detailed investigation because it provides a natural laboratory for the analysis of the nature, evolution and potential habitability of icy worlds in general and the role it plays within the system of Galilean satellites, and its unique magnetic and plasma interactions with Jupiter and its environment (known as the Jovian system). “Our results can provide the Juice instrument teams with valuable information that may be used to refine their observation plans to optimise the use of the spacecraft,” added Roth. Understanding the Jovian system and unravelling its history, from its origin to the possible emergence of habitable environments, will provide us with a better understanding of how gas giant planets and their satellites form and evolve. In addition, new insights will hopefully be found into the potential for the emergence of life in Jupiter-like exoplanetary systems. Credits: ESA/Hubble, NASA, J. Spencer; CC BY 4.0

#Jupiter#ESA#European Space Agency#Space#Universe#Cosmos#Space Science#Science#Space Technology#Tech#Technology#HST#Hubble Space Telescope#Galaxy#Supernova#NASA#Creative Commons#Ganymede#moon#Juice#Jovian#system#Jovian system

1 note

·

View note

Text

NASA Is On A Moonhunt. Its First Stop Next Week Is Ganymede, The Largest, Wettest And Weirdest Satellite In Our Solar System

https://sciencespies.com/news/nasa-is-on-a-moonhunt-its-first-stop-next-week-is-ganymede-the-largest-wettest-and-weirdest-satellite-in-our-solar-system/

NASA Is On A Moonhunt. Its First Stop Next Week Is Ganymede, The Largest, Wettest And Weirdest Satellite In Our Solar System

What’s the largest moon in the Solar System? Bigger than the planet Mercury and not much smaller than Mars, Ganymede is about to be explored by a NASA spacecraft that will next week begin an exciting extended mission.

A satellite of Jupiter, Ganymede will on June 7, 2021 be visited by NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which has just completed its core five-year mission surveying the giant planet.

Juno finished that mission in April with its 33rd perijove (close flyby), but instead of then preparing for “death dive” into Jupiter in July 2021, as initially planned, humanity’s furthest solar-powered spacecraft had its mission extended through to at least September 2025.

The north pole of Jupiter’s giant moon Ganymede can be seen in this composite image of infrared data … [+] from the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft. Five infrared images were taken every 20 minutes, beginning at time of closest approach (far left) on Dec. 26, 2019, when Juno was about 62,000 miles (100,000 kilometers) distant. The infrared imagery provides the first infrared mapping of the massive moon’s northern frontier.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM

June 7’s flyby of Ganymede will see Juno get to within 600 miles/1,000 kilometers.

That’s super-close. T

his low-altitude flyby—part of its perijove 34—will involve a course correction that will see Juno’s orbital period around Jupiter reduced from 53 days to 43 days. It will orbit the giant planet a further 42 times, but in a much more targeted manner.

That will enable it to conduct a close flyby of Europa, which it will get to within 200 miles/320 kilometers of in on September 29, 2022. It will then be in position to flyby the volcano moon of Io twice, getting to within 900 miles/1,500 km of it on both December 30, 2023 and on February 3, 2024.

Juno has already had a brief look at Ganymede, returning the first-ever images of its north pole after a flyby on December 26, 2019.

An ocean moon: why Ganymede is so interesting

Although incredibly cold and with a thin atmosphere, Ganymede remains a tantalising prospect for finding life beyond Earth.

That’s largely because it’s thought to contain an ocean of salt water under about 93 miles/150 kilometres of ice. Astrobiologists maintain that it could be home to extremophiles—single-cell microbial life.

Possible “Moonwich” of Ice and Oceans on Ganymede (Artist’s Concept). This artist’s concept of … [+] Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system, illustrates the “club sandwich” model of its interior oceans. Scientists suspect Ganymede has a massive ocean under an icy crust. In fact, Ganymede’s oceans may have 25 times the volume of those on Earth.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

7 other things you didn’t know about Ganymede

It’s the biggest of Jupiter’s 79 moons and one of the four so-called Galilean satellites—icy moons—around Jupiter, the others being Europa, Callisto and Io.

It’s the largest moon and the ninth-largest object in the Solar System.

It’s the only moon in the Solar System to have its own magnetic field.

That magnetic field causes aurorae, changes in which suggest an underground ocean containing possibly 25 times the volume of water of Earth’s oceans.

It has a thin oxygen atmosphere, but it’s not breathable so it’s almost certainly too thin to support life as we know it.

It’s 26% larger than Mercury, but only 45% as massive. In fact, it’s only slightly smaller than Mars.

It’s been previously photographed by NASA’s Pioneer 10, Voyager and Galileo spacecraft.

What is Juno?

Part of NASA’s New Frontiers program of medium-sized planetary science spacecraft, Juno’s extended mission means it’s now moving from a mission focused on studying the giant planet’s gravity and magnetic fields to a full system-explorer.

The JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission will launch next year.

Spacecraft: ESA/ATG medialab; Jupiter: NASA/ESA/J. Nichols (University of Leicester); Ganymede: NASA/JPL; Io: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona; Callisto and Europa: NASA/JPL/DLR

When is the next mission to Jupiter’s moons?

Juno’s extended mission should help NASA and the ESA (European Space Agency) plan their upcoming missions to Jupiter and its moons:

ESA (European Space Agency) JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission (scheduled to launch in 2022)

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission (scheduled to launch in 2024)

NASA’s Io Volcano Observer (IVO) mission (now under consideration for a possible launch in 2026-2028)

China is also planning two missions, the Jupiter Callisto Orbiter (JCO) and the Jupiter System Observer (JSO), which are scheduled to launch in 2030 and arrive in 2036. The JCO is expected to include a landing on Callisto.

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.

#News

#06-2021 Science News#2021 Science News#Earth Environment#earth science#Environment and Nature#freaky#Nature Science#News Science Spies#oddities#Our Nature#outrageous acts of science#planetary science#rare#scary#Science#Science Channel#science documentary#Science News#Science Spies#Science Spies News#Space Physics & Nature#Space Science#weird#News

0 notes

Video

NASA Juno Takes First Images of Jovian Moon Ganymede's North Pole by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center

Via Flickr:

Infrared images from Juno provide the first glimpse of Ganymede's icy north pole. On its way inbound for a Dec. 26, 2019, flyby of Jupiter, NASA's Juno spacecraft flew in the proximity of the north pole of the ninth-largest object in the solar system, the moon Ganymede. The infrared imagery collected by the spacecraft's Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument provides the first infrared mapping of the massive moon's northern frontier. The only moon in the solar system that is larger than the planet Mercury, Ganymede consists primarily of water ice. Its composition contains fundamental clues for understanding the evolution of the 79 Jovian moons from the time of their formation to today. Ganymede is also the only moon in the solar system with its own magnetic field. On Earth, the magnetic field provides a pathway for plasma (charged particles from the Sun) to enter our atmosphere and create aurora. As Ganymede has no atmosphere to impede their progress, the surface at its poles is constantly being bombarded by plasma from Jupiter's gigantic magnetosphere. The bombardment has a dramatic effect on Ganymede's ice. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM Read more More about Juno NASA Media Usage Guidelines

#NASA#Marshall Space Flight Center#MSFC#Jet Propulsion Laboratory#JPL#Solar system and beyond#Juno#Jupiter#Space#planets#Ganymede#Now Playing#3rd#August#2020#August 3rd 2020

0 notes

Text

Wild Lands and Cosy Camps in Iceland

Driving and camping along Iceland’s Ring Road takes a couple to iridescent geothermal sites, whale sightings, and national parks.

Bubbling mud pots, iridescent mineral deposits and steaming fumaroles at the geothermal site of Hverir are the stuff

of dreams. It’s worth driving east of Lake Mývatn to witness this spectacle. Photo By: ProMedia Sudath/Shutterstock

Húsavík, Day 7

The sperm whales showed up one and a half hours into our journey across the Arctic sea. The sky had turned leaden and the sea had merged with it, and the only line differentiating the two was the school of six whales spouting water from their blowholes. The sprays spread into the air and disappeared like dandelions in a storm, reappearing every few minutes. Next to me, a six-foot-tall American doubled over with sea-sickness was retching into the Arctic. His wife, although sympathetic to his plight, looked a bit annoyed at having to let go of this ecstatic photographic moment of whale sighting. I observed the whales, swaying between dizziness and exhilaration, grateful to have finally seen them, regretful that the puffins had not shown, and impatient to stand firm on land once again.

***

My husband, S, and I are in the whaling town of Húsavík in the north coast of Iceland and we’ve been driving and camping for over a week now. Having started with sunny weather, our undependable luck caught up with us by Day 4 and we’ve had the rains chasing us for days. They come and go, leaving the campsites damp and muddy, making our task of pitching tents every evening before dinner a Herculean effort that we’ve been managing so far with steady swigs of whiskey. But after the whales have been seen, and the nightmare of a boat ride endured without messy accidents, I insist that we need the comfort of a warm B&B. After we’ve had the most luxurious sleep in days, we’re refreshed and ready for some more camp living. But the sky outside still bears down on the sea with its dark clouds and I ask the man at the reception doing our bills if the weather is always this challenging? He looks up at me with eyes full of remorse and says, “I have to say you have real bad luck because until the day before the sun was out and shining and the sea was the bluest of blues. I wish you better luck when you come next.” I thank him with the saddest smile I can muster and leave the building hoping against hope for the sun to show.

Hvolsvöllur, Day 2

Camping in Vatnajökull National Park is a pinch-yourself-to-see-if-it’s-real sort of experience. Photo By: Henn Photography/Cultura/Getty images

We’ve left behind the lights and tin-walled dwellings of Reykjavik to go deeper into the south on Route 1 or the Ring Road which goes in a complete circle surrounding most of Iceland, giving the fjords in the west a miss. As far as the eye can see, there are no people, just table-topped mountains covered in a spill of moss and lichen and black volcanic soil. Years ago, when the unpronounceable Eyjafjallajökull erupted, halting air traffic in most of Europe, I had looked at stock images and marvelled at its scale. Now looking at other lava fields spreading out around us I feel like I’m inside a movie. Each scene reveals an even more improbable landscape—a desolate, untouched wilderness of low shrubbery, blue rivers and gushing waterfalls which appear with the regularity of punctuation in a very long, artful sentence. There are sheep grazing, their coats so bulky and furry they look like white and black hay bales on a limitless farm. And then there are the horses—stout, docile, their manes flowing in the chilly wind like a mythical beast’s. The animals and fields seem suspended in time as if they’ve always been there and always will be irrespective of days passing and seasons changing.

As we enter the campsite at the town of Hvolsvöllur, 106 kilometres southeast of Reykjavik, and set up our tents and ready our portable stove for dinner, we see a woman with a shock of silver, frizzy hair approaching us. “Are you going to need a shower?” she asks. We nod in obviousness. She then holds out her palm for 800 krónas as fee for using the hot shower at the campsite. We pay her quick and watch her go knocking on every other parked vehicle or pitched tent. She tells us cheerily that she comes every evening to clean the camp kitchen and bathrooms, housed in two red-painted portable structures, and collects the charges for maintenance. As we wait for our sausages and eggs to cook and sip on coffee from camping mugs, we watch the quiet campsite slowly fill up with cars and the hum of chatter, and then tents pop up like colourful igloos dotting the ground with oranges, army greens, and dark blues. The late-summer wind makes us shiver and finally, when the long day is taken over by a darkening sky, we wait for the stars to come slowly aglow.

Skaftafell and Vatnajökull National Park, Day 4-5

Driving on Route 1 has felt more like comfort than chore. We’ve escaped a tourist-saturated south for the moonscape of Skaftafell, a scenic area in Vatnajökull National Park in Iceland’s southeast. The summer night is feeble and the volcanic beaches inky black; an unknown deserted universe laid out flat and open just for us. We’ve driven past vast green treeless expanses; strolled along cold, black-sand beaches strewn with ice blocks broken off from Vatnajökull—Iceland’s largest ice cap—shining like diamonds under a timid sun. We’ve been soaked from the spray of the mighty Dettifoss waterfall as it frothed and foamed its way into the Jökulsá á Fjöllum river. We’ve set up our moveable home at Skaftafell, on fields of green bordered by hills that looked as if the skies had parted and poured giant buckets of emerald felt down them for years.

The waters around Húsavík (bottom-left) are a fertile home for humpback and sperm whales; Icelandic horses (bottom-right) are descendants of ponies first brought here by Norse settlers in the ninth century; Unexpected furry guests (top-left) often greet drivers on Ring Road; Diamond Beach (top-right), is a glacial outwash plain in southeast Iceland and a big draw for tourists. Photos By: Horstgerlach/iStock Unreleased/Getty images (boat), ROM/imageBROKER/Getty images (horses); Alexey Stiop/Shutterstock (animals); Technotr/E+/Getty images (beach)

Mývatn, Day 6

Thanks to the eye-popping landscape we’ve had so many stops on the way that we have lost track of time and are running quite late. The rain hasn’t shown any sign of remission and S, in order to get ahead of the clock, has taken a turn onto a gravel road that would get us to the northern volcanic lake of Mývatn just in time for sun down. We bounce over hills, and slow down like a cautious cat at bends looking out for blind turns. A dense, impenetrable fog swirls outside and at one point I’m certain we’re about to crash to our deaths. Then as suddenly as it had descended, the fog lifts and clears our vision to a wall of waterfalls on the horizon. We drive down the slim, gravel track leading back to Route 1.

We continue our drive down the almost buttery smooth Ring Road flanked by mountains and clear, sparkling lakes. We occasionally spot an iron letterbox and reckon the lone house that stood a mile away from the highway overlooking the sea. Here is isolation and its gift of abundance—each individual on his or her own acre in the midst of nowhere and with a window on the infinite blue horizon. Here it is possible to respect nature and to take refuge in it.

Watching the aurora (top-left) spill colours on the Icelandic night sky isn’t a memory you’ll likely forget; Húsavík (bottom) sits on the eastern shore of Shaky Bay and has the distinction of being the whale capital of Iceland; The Church of Akureyri (top-right) is the town’s most enduring symbol and holds a notably large 3,200-pipe organ. Photos By: Olivier Bergeron/500Px Plus/Getty images (northern lights); Alexeys/iStock/Getty images (lake),; Coolkengzz/iStock/Getty images (church)

Slowly we approach Mývatn, our stop for the night. Steam rises from grey muddy pits bubbling with boiling mud sediments, and the air reeks of sulphur. The landscape has yet again, unmistakeably and without warning, changed. A vast ochre desert lies open before us against the setting sun and steam columns reach up to kiss the sky. We drive further down into the town and pitch our tent by the calm, teal Mývatn lake. While stuffing our faces with steaming pasta, we watch ducks swim past us and count the sad-eyed sheep that flock on the hill right across.

Akureyri and Hvammstangi, Day 8-9

When we arrive in the northern town of Akureyri, the rain has finally left us and the sun is high in the sky. We visit cafés and bookshops and drink beer at hipster bars. We see trees like poplar and rowan, which we hadn’t seen anywhere else in the country, and walk past gardens bursting with scarlet and golden flowers. We take the most spirit-restoring dip in the town’s public hot pool—a complex with four pools set to different cool and hot temperatures just to afford you the best sleep that will surely follow. Elderly men and women sit in extended circles murmuring like politicians—a daily ritual for most Icelanders.

***

We get back on the road again and drive past farms alternated with steep, mountainous descents until we take a right and drive into the northwestern village of Hvammstangi standing right next to the sea. The Arctic has turned rough again, and the wind has picked up after an afternoon’s rest. We struggle to pitch our tent against the strong currents but finally manage to make it steady for our last night out in the open. After dinner, we venture out to spot the Milky Way. As we train our eyes on the northern sky, dark over the sea, we notice it dapple with green spreading like an approaching wave. The wave flickers, fades, recedes, darkens and reappears until it dances ever so slightly. A streak of faint light spills slowly illuminating the sky with a tender, iridescent glow. The aurora comes alive for us—we watch, our eyes fixated.

All flights between Delhi and Mumbai and Reykjavik require at least one layover at a European gateway city such as Amsterdam, Frankfurt, or Paris.

Indian travellers need a tourist visa to visit Iceland. Applications for the Schengen visa can be made online through VFS (dk.vfsglobal.co.in) and relevant documents (list on website) must be handed in at the visa application centre in person. The 3-month tourist visa costs Rs4,680 (plus Rs780 service fee), and takes about 15 working days to process.

Camping

The best time to camp in Iceland is Jun-Sept. Temperatures in June through August hover at 15-20°C, whereas night temperatures in September can dip to 5°C. September is usually the start of the Aurora season too, though there are no guarantees; weather is pretty unpredictable across seasons here.

Between May and August, the tiny island of Lundey, just off Húsavík, hosts nearly 2,00,000 Atlantic puffins, who gather here to breed. Photo By: FedevPhoto/iStock/Getty images

Campsites are easily found in almost all towns and national parks, and most are equipped with toilets, showers, a tiny kitchen (though not everywhere), and washing facilities. Summers are busy and it’s advisable to book ahead. Charges per person per night vary between €11-20/Rs850-Rs1540. At national parks, pay for designated areas at the visitors’ centre (sites are usually equipped with toilets, showers, and eating areas).

Camping essentials include tent, stove (can be rented, or bought from supermarkets), cooking utensils and cutlery, shower shoes, car charger, solar powered battery charger and a head lamp. Food is pretty expensive in Iceland, so draw up a menu that’s easy to cook, or stock up on sandwiches.

If you’re camping in the open, hire an SUV (www.bluecarrental.is is a good option; from ISK51,606/Rs28,475 for a small, automatic car for 10 days, including insurance, minus petrol).

(function(d, s, id) var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "http://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.5&appId=440470606060560"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); (document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));

from Cheapr Travels https://ift.tt/2nNeMAk

via https://ift.tt/2NIqXKN

0 notes

Text

Epic Antarctic voyage maps seafloor to predict ocean rise as glacier the size of California melts

Global research group will trace Totten glaciers history back to last ice age, in hope of predicting future melting patterns

In East Antarctica, 3,000km south of the West Australian town of Albany, an ice shelf the size of California is melting from below.

The concerning trend was confirmed by Australian scientists in December, who reported that warming ocean temperatures were causing the rapid melt of the end of the Totten glacier, which is holding back enough ice to create a global sea rise of between 3.5 metres and six metres.

On Saturday, a team of international scientists left Hobart aboard the Australian research ship Investigator to map the seafloor ahead of the glacier to trace its history back to the last ice age, in the hopes of predicting its future melting patterns.

The 51-day mission is one of the longest ever voyages by Australian scientists to Antarctica and will involve mapping the unexplored Sabrina Coast seafloor and taking samples of piles of glacial sediment left behind by the retreating ice sheet.

It has been four years in the planning for the chief scientist Dr Leanne Armand, an associate professor with Sydneys Macquarie University.

The focus will be the area around the base of the Totten glacier, which is usually surrounded by ice. Reports from researchers aboard the Aurora Australis, which was in the area in December, show that fast ice has melted back.

If that goes, then well be able to get in and provide the very first seafloor maps on the continental shelf itself and that will be really critical to a whole bunch of different sciences, Armand said.

She will head a team of 22 researchers from Australia, Italy, Spain and the United States. They will be assisted by 12 support staff from the Marine National Facility, a subdivision of the CSIRO, which operates the Investigator; a Tasmanian high school science teacher; and 20 crew.

Also on board is Dr Tara Martin, a CSIRO scientist who helped design the Investigator and will act on this mission as the ships geophysicist, monitoring the sonar and seismic equipment used to map the seafloor.

Martin said the seismic equipment, borrowed from the Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia in Italy, would be used to examine the composition of the sediment layers to help researchers pinpoint the best locations for extracting rock cores, which will in turn be used to map past glacial melting patterns.

One of the things were trying to understand here is, is this [glacial] retreat normal, has this kind of retreat happened before, and has this speed of retreat happened before, Martin said. If its not normal, how much of what were observing today can we isolate from what is normal, and therefore maybe see what could be an anthropogenic effect.

The worst scenario, Martin said, was that the ice tongue of the glacier could disappear.

If you remove that ice tongue, in theory youre releasing the break on the rate of flow of the glacier, she said. So the concern is … if the whole ice tongue melts away, potentially the whole glacier could rush out to sea over a geological timescale, and we dont know what that timescale is. Losing an ice tongue and having it break off its already in the water, that doesnt add to sea level rise very much. But losing a glacier the size of California thats currently on land and dumping that in the water thats going to change sea level rise estimates.

The expedition is authorised to take a maximum of 15 cores, measuring 10cm in diameter and up to 24 metres long.

The cores will be cut into one metre lengths in an area known as the wet and dirty lab, capped at both ends, and placed in cold storage until they can be transported to Geoscience Australia, where interested researchers will hold a party to divide up the samples.

It is Armands ninth voyage to the Antarctic, and Martins 14th. Both have refined their list of items to bring to stave off boredom on the lengthy voyage, in the little downtime provided at the end of a 12-hour shift.

The ship is kitted out with a gym, a video and games room, and twin bunk rooms with en suites, as well as sophisticated scientific equipment and laboratories.

The bunk beds have curtains to help roommates on opposite shifts.

But even in those comparatively comfortable environments, Armand says, most people bring some form of creature comfort.

Armands must-have is natural raspberry cordial, followed by a box of her favourite muesli and her own mug. Martins is more extensive: a a seriously embarrassing amount of books, as well as a camera, binoculars and field guide for spotting wildlife. She also brings knitting.

Her list of books is eclectic: Dickens, Austen, a few popular science geology books recommended to her by a geeked out pack of geoscientists on her last sub-Antarctic voyage, the memoirs of Philip Law, who directed the Australian Antarctic Division in the 1950s, and a standard range of fiction.

On top of personal luxuries, and Martins small library, everyone on board is required to bring, at minimum: two pairs of gloves (one waterproof, one woollen); one beanie; two pairs of woollen or thermal pants, two woollen or thermal tops, three pairs of woollen socks; one polar fleece jacket; one pair of polar fleece pants; one pair of steel-toe boots; and one pair of polarised sunglasses.

A strap for said sunglasses, a balaclava, a snood, an insulated down jacket, and steel-toe gumboots are highly recommended.

Other safety gear, such as hard hats and high-visibility jackets, is provided.

Read more: http://bit.ly/2iu6Wmd

from Epic Antarctic voyage maps seafloor to predict ocean rise as glacier the size of California melts

0 notes

Text

NASA Is On A Moonhunt. Its First Stop Next Week Is Ganymede, The Largest, Wettest And Weirdest Satellite In Our Solar System

https://sciencespies.com/news/nasa-is-on-a-moonhunt-its-first-stop-next-week-is-ganymede-the-largest-wettest-and-weirdest-satellite-in-our-solar-system/

NASA Is On A Moonhunt. Its First Stop Next Week Is Ganymede, The Largest, Wettest And Weirdest Satellite In Our Solar System

What’s the largest moon in the Solar System? Bigger than the planet Mercury and not much smaller than Mars, Ganymede is about to be explored by a NASA spacecraft that will next week begin an exciting extended mission.

A satellite of Jupiter, Ganymede will on June 7, 2021 be visited by NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which has just completed its core five-year mission surveying the giant planet.

Juno finished that mission in April with its 33rd perijove (close flyby), but instead of then preparing for “death dive” into Jupiter in July 2021, as initially planned, humanity’s furthest solar-powered spacecraft had its mission extended through to at least September 2025.

The north pole of Jupiter’s giant moon Ganymede can be seen in this composite image of infrared data … [+] from the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft. Five infrared images were taken every 20 minutes, beginning at time of closest approach (far left) on Dec. 26, 2019, when Juno was about 62,000 miles (100,000 kilometers) distant. The infrared imagery provides the first infrared mapping of the massive moon’s northern frontier.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM

June 7’s flyby of Ganymede will see Juno get to within 600 miles/1,000 kilometers.

That’s super-close. T

his low-altitude flyby—part of its perijove 34—will involve a course correction that will see Juno’s orbital period around Jupiter reduced from 53 days to 43 days. It will orbit the giant planet a further 42 times, but in a much more targeted manner.

That will enable it to conduct a close flyby of Europa, which it will get to within 200 miles/320 kilometers of in on September 29, 2022. It will then be in position to flyby the volcano moon of Io twice, getting to within 900 miles/1,500 km of it on both December 30, 2023 and on February 3, 2024.

Juno has already had a brief look at Ganymede, returning the first-ever images of its north pole after a flyby on December 26, 2019.

An ocean moon: why Ganymede is so interesting

Although incredibly cold and with a thin atmosphere, Ganymede remains a tantalising prospect for finding life beyond Earth.

That’s largely because it’s thought to contain an ocean of salt water under about 93 miles/150 kilometres of ice. Astrobiologists maintain that it could be home to extremophiles—single-cell microbial life.

Possible “Moonwich” of Ice and Oceans on Ganymede (Artist’s Concept). This artist’s concept of … [+] Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system, illustrates the “club sandwich” model of its interior oceans. Scientists suspect Ganymede has a massive ocean under an icy crust. In fact, Ganymede’s oceans may have 25 times the volume of those on Earth.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

7 other things you didn’t know about Ganymede

It’s the biggest of Jupiter’s 79 moons and one of the four so-called Galilean satellites—icy moons—around Jupiter, the others being Europa, Callisto and Io.

It’s the largest moon and the ninth-largest object in the Solar System.

It’s the only moon in the Solar System to have its own magnetic field.

That magnetic field causes aurorae, changes in which suggest an underground ocean containing possibly 25 times the volume of water of Earth’s oceans.

It has a thin oxygen atmosphere, but it’s not breathable so it’s almost certainly too thin to support life as we know it.

It’s 26% larger than Mercury, but only 45% as massive. In fact, it’s only slightly smaller than Mars.

It’s been previously photographed by NASA’s Pioneer 10, Voyager and Galileo spacecraft.

What is Juno?

Part of NASA’s New Frontiers program of medium-sized planetary science spacecraft, Juno’s extended mission means it’s now moving from a mission focused on studying the giant planet’s gravity and magnetic fields to a full system-explorer.

The JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission will launch next year.

Spacecraft: ESA/ATG medialab; Jupiter: NASA/ESA/J. Nichols (University of Leicester); Ganymede: NASA/JPL; Io: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona; Callisto and Europa: NASA/JPL/DLR

When is the next mission to Jupiter’s moons?

Juno’s extended mission should help NASA and the ESA (European Space Agency) plan their upcoming missions to Jupiter and its moons:

ESA (European Space Agency) JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission (scheduled to launch in 2022)

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission (scheduled to launch in 2024)

NASA’s Io Volcano Observer (IVO) mission (now under consideration for a possible launch in 2026-2028)

China is also planning two missions, the Jupiter Callisto Orbiter (JCO) and the Jupiter System Observer (JSO), which are scheduled to launch in 2030 and arrive in 2036. The JCO is expected to include a landing on Callisto.

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.

#News

#06-2021 Science News#2021 Science News#Earth Environment#earth science#Environment and Nature#freaky#Nature Science#News Science Spies#oddities#Our Nature#outrageous acts of science#planetary science#rare#scary#Science#Science Channel#science documentary#Science News#Science Spies#Science Spies News#Space Physics & Nature#Space Science#weird#News

0 notes

Text

Wild Lands and Cosy Camps in Iceland

Driving and camping along Iceland’s Ring Road takes a couple to iridescent geothermal sites, whale sightings, and national parks.

Bubbling mud pots, iridescent mineral deposits and steaming fumaroles at the geothermal site of Hverir are the stuff

of dreams. It’s worth driving east of Lake Mývatn to witness this spectacle. Photo By: ProMedia Sudath/Shutterstock

Húsavík, Day 7

The sperm whales showed up one and a half hours into our journey across the Arctic sea. The sky had turned leaden and the sea had merged with it, and the only line differentiating the two was the school of six whales spouting water from their blowholes. The sprays spread into the air and disappeared like dandelions in a storm, reappearing every few minutes. Next to me, a six-foot-tall American doubled over with sea-sickness was retching into the Arctic. His wife, although sympathetic to his plight, looked a bit annoyed at having to let go of this ecstatic photographic moment of whale sighting. I observed the whales, swaying between dizziness and exhilaration, grateful to have finally seen them, regretful that the puffins had not shown, and impatient to stand firm on land once again.

***

My husband, S, and I are in the whaling town of Húsavík in the north coast of Iceland and we’ve been driving and camping for over a week now. Having started with sunny weather, our undependable luck caught up with us by Day 4 and we’ve had the rains chasing us for days. They come and go, leaving the campsites damp and muddy, making our task of pitching tents every evening before dinner a Herculean effort that we’ve been managing so far with steady swigs of whiskey. But after the whales have been seen, and the nightmare of a boat ride endured without messy accidents, I insist that we need the comfort of a warm B&B. After we’ve had the most luxurious sleep in days, we’re refreshed and ready for some more camp living. But the sky outside still bears down on the sea with its dark clouds and I ask the man at the reception doing our bills if the weather is always this challenging? He looks up at me with eyes full of remorse and says, “I have to say you have real bad luck because until the day before the sun was out and shining and the sea was the bluest of blues. I wish you better luck when you come next.” I thank him with the saddest smile I can muster and leave the building hoping against hope for the sun to show.

Hvolsvöllur, Day 2

Camping in Vatnajökull National Park is a pinch-yourself-to-see-if-it’s-real sort of experience. Photo By: Henn Photography/Cultura/Getty images

We’ve left behind the lights and tin-walled dwellings of Reykjavik to go deeper into the south on Route 1 or the Ring Road which goes in a complete circle surrounding most of Iceland, giving the fjords in the west a miss. As far as the eye can see, there are no people, just table-topped mountains covered in a spill of moss and lichen and black volcanic soil. Years ago, when the unpronounceable Eyjafjallajökull erupted, halting air traffic in most of Europe, I had looked at stock images and marvelled at its scale. Now looking at other lava fields spreading out around us I feel like I’m inside a movie. Each scene reveals an even more improbable landscape—a desolate, untouched wilderness of low shrubbery, blue rivers and gushing waterfalls which appear with the regularity of punctuation in a very long, artful sentence. There are sheep grazing, their coats so bulky and furry they look like white and black hay bales on a limitless farm. And then there are the horses—stout, docile, their manes flowing in the chilly wind like a mythical beast’s. The animals and fields seem suspended in time as if they’ve always been there and always will be irrespective of days passing and seasons changing.

As we enter the campsite at the town of Hvolsvöllur, 106 kilometres southeast of Reykjavik, and set up our tents and ready our portable stove for dinner, we see a woman with a shock of silver, frizzy hair approaching us. “Are you going to need a shower?” she asks. We nod in obviousness. She then holds out her palm for 800 krónas as fee for using the hot shower at the campsite. We pay her quick and watch her go knocking on every other parked vehicle or pitched tent. She tells us cheerily that she comes every evening to clean the camp kitchen and bathrooms, housed in two red-painted portable structures, and collects the charges for maintenance. As we wait for our sausages and eggs to cook and sip on coffee from camping mugs, we watch the quiet campsite slowly fill up with cars and the hum of chatter, and then tents pop up like colourful igloos dotting the ground with oranges, army greens, and dark blues. The late-summer wind makes us shiver and finally, when the long day is taken over by a darkening sky, we wait for the stars to come slowly aglow.

Skaftafell and Vatnajökull National Park, Day 4-5

Driving on Route 1 has felt more like comfort than chore. We’ve escaped a tourist-saturated south for the moonscape of Skaftafell, a scenic area in Vatnajökull National Park in Iceland’s southeast. The summer night is feeble and the volcanic beaches inky black; an unknown deserted universe laid out flat and open just for us. We’ve driven past vast green treeless expanses; strolled along cold, black-sand beaches strewn with ice blocks broken off from Vatnajökull—Iceland’s largest ice cap—shining like diamonds under a timid sun. We’ve been soaked from the spray of the mighty Dettifoss waterfall as it frothed and foamed its way into the Jökulsá á Fjöllum river. We’ve set up our moveable home at Skaftafell, on fields of green bordered by hills that looked as if the skies had parted and poured giant buckets of emerald felt down them for years.

The waters around Húsavík (bottom-left) are a fertile home for humpback and sperm whales; Icelandic horses (bottom-right) are descendants of ponies first brought here by Norse settlers in the ninth century; Unexpected furry guests (top-left) often greet drivers on Ring Road; Diamond Beach (top-right), is a glacial outwash plain in southeast Iceland and a big draw for tourists. Photos By: Horstgerlach/iStock Unreleased/Getty images (boat), ROM/imageBROKER/Getty images (horses); Alexey Stiop/Shutterstock (animals); Technotr/E+/Getty images (beach)

Mývatn, Day 6

Thanks to the eye-popping landscape we’ve had so many stops on the way that we have lost track of time and are running quite late. The rain hasn’t shown any sign of remission and S, in order to get ahead of the clock, has taken a turn onto a gravel road that would get us to the northern volcanic lake of Mývatn just in time for sun down. We bounce over hills, and slow down like a cautious cat at bends looking out for blind turns. A dense, impenetrable fog swirls outside and at one point I’m certain we’re about to crash to our deaths. Then as suddenly as it had descended, the fog lifts and clears our vision to a wall of waterfalls on the horizon. We drive down the slim, gravel track leading back to Route 1.

We continue our drive down the almost buttery smooth Ring Road flanked by mountains and clear, sparkling lakes. We occasionally spot an iron letterbox and reckon the lone house that stood a mile away from the highway overlooking the sea. Here is isolation and its gift of abundance—each individual on his or her own acre in the midst of nowhere and with a window on the infinite blue horizon. Here it is possible to respect nature and to take refuge in it.

Watching the aurora (top-left) spill colours on the Icelandic night sky isn’t a memory you’ll likely forget; Húsavík (bottom) sits on the eastern shore of Shaky Bay and has the distinction of being the whale capital of Iceland; The Church of Akureyri (top-right) is the town’s most enduring symbol and holds a notably large 3,200-pipe organ. Photos By: Olivier Bergeron/500Px Plus/Getty images (northern lights); Alexeys/iStock/Getty images (lake),; Coolkengzz/iStock/Getty images (church)

Slowly we approach Mývatn, our stop for the night. Steam rises from grey muddy pits bubbling with boiling mud sediments, and the air reeks of sulphur. The landscape has yet again, unmistakeably and without warning, changed. A vast ochre desert lies open before us against the setting sun and steam columns reach up to kiss the sky. We drive further down into the town and pitch our tent by the calm, teal Mývatn lake. While stuffing our faces with steaming pasta, we watch ducks swim past us and count the sad-eyed sheep that flock on the hill right across.

Akureyri and Hvammstangi, Day 8-9

When we arrive in the northern town of Akureyri, the rain has finally left us and the sun is high in the sky. We visit cafés and bookshops and drink beer at hipster bars. We see trees like poplar and rowan, which we hadn’t seen anywhere else in the country, and walk past gardens bursting with scarlet and golden flowers. We take the most spirit-restoring dip in the town’s public hot pool—a complex with four pools set to different cool and hot temperatures just to afford you the best sleep that will surely follow. Elderly men and women sit in extended circles murmuring like politicians—a daily ritual for most Icelanders.

***

We get back on the road again and drive past farms alternated with steep, mountainous descents until we take a right and drive into the northwestern village of Hvammstangi standing right next to the sea. The Arctic has turned rough again, and the wind has picked up after an afternoon’s rest. We struggle to pitch our tent against the strong currents but finally manage to make it steady for our last night out in the open. After dinner, we venture out to spot the Milky Way. As we train our eyes on the northern sky, dark over the sea, we notice it dapple with green spreading like an approaching wave. The wave flickers, fades, recedes, darkens and reappears until it dances ever so slightly. A streak of faint light spills slowly illuminating the sky with a tender, iridescent glow. The aurora comes alive for us—we watch, our eyes fixated.

All flights between Delhi and Mumbai and Reykjavik require at least one layover at a European gateway city such as Amsterdam, Frankfurt, or Paris.

Indian travellers need a tourist visa to visit Iceland. Applications for the Schengen visa can be made online through VFS (dk.vfsglobal.co.in) and relevant documents (list on website) must be handed in at the visa application centre in person. The 3-month tourist visa costs Rs4,680 (plus Rs780 service fee), and takes about 15 working days to process.

Camping

The best time to camp in Iceland is Jun-Sept. Temperatures in June through August hover at 15-20°C, whereas night temperatures in September can dip to 5°C. September is usually the start of the Aurora season too, though there are no guarantees; weather is pretty unpredictable across seasons here.

Between May and August, the tiny island of Lundey, just off Húsavík, hosts nearly 2,00,000 Atlantic puffins, who gather here to breed. Photo By: FedevPhoto/iStock/Getty images

Campsites are easily found in almost all towns and national parks, and most are equipped with toilets, showers, a tiny kitchen (though not everywhere), and washing facilities. Summers are busy and it’s advisable to book ahead. Charges per person per night vary between €11-20/Rs850-Rs1540. At national parks, pay for designated areas at the visitors’ centre (sites are usually equipped with toilets, showers, and eating areas).

Camping essentials include tent, stove (can be rented, or bought from supermarkets), cooking utensils and cutlery, shower shoes, car charger, solar powered battery charger and a head lamp. Food is pretty expensive in Iceland, so draw up a menu that’s easy to cook, or stock up on sandwiches.

If you’re camping in the open, hire an SUV (www.bluecarrental.is is a good option; from ISK51,606/Rs28,475 for a small, automatic car for 10 days, including insurance, minus petrol).

(function(d, s, id) var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "http://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.5&appId=440470606060560"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); (document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));

source http://cheaprtravels.com/wild-lands-and-cosy-camps-in-iceland/

0 notes

Text

Wild Lands and Cosy Camps in Iceland

Driving and camping along Iceland’s Ring Road takes a couple to iridescent geothermal sites, whale sightings, and national parks.

Bubbling mud pots, iridescent mineral deposits and steaming fumaroles at the geothermal site of Hverir are the stuff

of dreams. It’s worth driving east of Lake Mývatn to witness this spectacle. Photo By: ProMedia Sudath/Shutterstock

Húsavík, Day 7

The sperm whales showed up one and a half hours into our journey across the Arctic sea. The sky had turned leaden and the sea had merged with it, and the only line differentiating the two was the school of six whales spouting water from their blowholes. The sprays spread into the air and disappeared like dandelions in a storm, reappearing every few minutes. Next to me, a six-foot-tall American doubled over with sea-sickness was retching into the Arctic. His wife, although sympathetic to his plight, looked a bit annoyed at having to let go of this ecstatic photographic moment of whale sighting. I observed the whales, swaying between dizziness and exhilaration, grateful to have finally seen them, regretful that the puffins had not shown, and impatient to stand firm on land once again.

***

My husband, S, and I are in the whaling town of Húsavík in the north coast of Iceland and we’ve been driving and camping for over a week now. Having started with sunny weather, our undependable luck caught up with us by Day 4 and we’ve had the rains chasing us for days. They come and go, leaving the campsites damp and muddy, making our task of pitching tents every evening before dinner a Herculean effort that we’ve been managing so far with steady swigs of whiskey. But after the whales have been seen, and the nightmare of a boat ride endured without messy accidents, I insist that we need the comfort of a warm B&B. After we’ve had the most luxurious sleep in days, we’re refreshed and ready for some more camp living. But the sky outside still bears down on the sea with its dark clouds and I ask the man at the reception doing our bills if the weather is always this challenging? He looks up at me with eyes full of remorse and says, “I have to say you have real bad luck because until the day before the sun was out and shining and the sea was the bluest of blues. I wish you better luck when you come next.” I thank him with the saddest smile I can muster and leave the building hoping against hope for the sun to show.

Hvolsvöllur, Day 2

Camping in Vatnajökull National Park is a pinch-yourself-to-see-if-it’s-real sort of experience. Photo By: Henn Photography/Cultura/Getty images

We’ve left behind the lights and tin-walled dwellings of Reykjavik to go deeper into the south on Route 1 or the Ring Road which goes in a complete circle surrounding most of Iceland, giving the fjords in the west a miss. As far as the eye can see, there are no people, just table-topped mountains covered in a spill of moss and lichen and black volcanic soil. Years ago, when the unpronounceable Eyjafjallajökull erupted, halting air traffic in most of Europe, I had looked at stock images and marvelled at its scale. Now looking at other lava fields spreading out around us I feel like I’m inside a movie. Each scene reveals an even more improbable landscape—a desolate, untouched wilderness of low shrubbery, blue rivers and gushing waterfalls which appear with the regularity of punctuation in a very long, artful sentence. There are sheep grazing, their coats so bulky and furry they look like white and black hay bales on a limitless farm. And then there are the horses—stout, docile, their manes flowing in the chilly wind like a mythical beast’s. The animals and fields seem suspended in time as if they’ve always been there and always will be irrespective of days passing and seasons changing.

As we enter the campsite at the town of Hvolsvöllur, 106 kilometres southeast of Reykjavik, and set up our tents and ready our portable stove for dinner, we see a woman with a shock of silver, frizzy hair approaching us. “Are you going to need a shower?” she asks. We nod in obviousness. She then holds out her palm for 800 krónas as fee for using the hot shower at the campsite. We pay her quick and watch her go knocking on every other parked vehicle or pitched tent. She tells us cheerily that she comes every evening to clean the camp kitchen and bathrooms, housed in two red-painted portable structures, and collects the charges for maintenance. As we wait for our sausages and eggs to cook and sip on coffee from camping mugs, we watch the quiet campsite slowly fill up with cars and the hum of chatter, and then tents pop up like colourful igloos dotting the ground with oranges, army greens, and dark blues. The late-summer wind makes us shiver and finally, when the long day is taken over by a darkening sky, we wait for the stars to come slowly aglow.

Skaftafell and Vatnajökull National Park, Day 4-5

Driving on Route 1 has felt more like comfort than chore. We’ve escaped a tourist-saturated south for the moonscape of Skaftafell, a scenic area in Vatnajökull National Park in Iceland’s southeast. The summer night is feeble and the volcanic beaches inky black; an unknown deserted universe laid out flat and open just for us. We’ve driven past vast green treeless expanses; strolled along cold, black-sand beaches strewn with ice blocks broken off from Vatnajökull—Iceland’s largest ice cap—shining like diamonds under a timid sun. We’ve been soaked from the spray of the mighty Dettifoss waterfall as it frothed and foamed its way into the Jökulsá á Fjöllum river. We’ve set up our moveable home at Skaftafell, on fields of green bordered by hills that looked as if the skies had parted and poured giant buckets of emerald felt down them for years.

The waters around Húsavík (bottom-left) are a fertile home for humpback and sperm whales; Icelandic horses (bottom-right) are descendants of ponies first brought here by Norse settlers in the ninth century; Unexpected furry guests (top-left) often greet drivers on Ring Road; Diamond Beach (top-right), is a glacial outwash plain in southeast Iceland and a big draw for tourists. Photos By: Horstgerlach/iStock Unreleased/Getty images (boat), ROM/imageBROKER/Getty images (horses); Alexey Stiop/Shutterstock (animals); Technotr/E+/Getty images (beach)

Mývatn, Day 6

Thanks to the eye-popping landscape we’ve had so many stops on the way that we have lost track of time and are running quite late. The rain hasn’t shown any sign of remission and S, in order to get ahead of the clock, has taken a turn onto a gravel road that would get us to the northern volcanic lake of Mývatn just in time for sun down. We bounce over hills, and slow down like a cautious cat at bends looking out for blind turns. A dense, impenetrable fog swirls outside and at one point I’m certain we’re about to crash to our deaths. Then as suddenly as it had descended, the fog lifts and clears our vision to a wall of waterfalls on the horizon. We drive down the slim, gravel track leading back to Route 1.

We continue our drive down the almost buttery smooth Ring Road flanked by mountains and clear, sparkling lakes. We occasionally spot an iron letterbox and reckon the lone house that stood a mile away from the highway overlooking the sea. Here is isolation and its gift of abundance—each individual on his or her own acre in the midst of nowhere and with a window on the infinite blue horizon. Here it is possible to respect nature and to take refuge in it.

Watching the aurora (top-left) spill colours on the Icelandic night sky isn’t a memory you’ll likely forget; Húsavík (bottom) sits on the eastern shore of Shaky Bay and has the distinction of being the whale capital of Iceland; The Church of Akureyri (top-right) is the town’s most enduring symbol and holds a notably large 3,200-pipe organ. Photos By: Olivier Bergeron/500Px Plus/Getty images (northern lights); Alexeys/iStock/Getty images (lake),; Coolkengzz/iStock/Getty images (church)

Slowly we approach Mývatn, our stop for the night. Steam rises from grey muddy pits bubbling with boiling mud sediments, and the air reeks of sulphur. The landscape has yet again, unmistakeably and without warning, changed. A vast ochre desert lies open before us against the setting sun and steam columns reach up to kiss the sky. We drive further down into the town and pitch our tent by the calm, teal Mývatn lake. While stuffing our faces with steaming pasta, we watch ducks swim past us and count the sad-eyed sheep that flock on the hill right across.

Akureyri and Hvammstangi, Day 8-9

When we arrive in the northern town of Akureyri, the rain has finally left us and the sun is high in the sky. We visit cafés and bookshops and drink beer at hipster bars. We see trees like poplar and rowan, which we hadn’t seen anywhere else in the country, and walk past gardens bursting with scarlet and golden flowers. We take the most spirit-restoring dip in the town’s public hot pool—a complex with four pools set to different cool and hot temperatures just to afford you the best sleep that will surely follow. Elderly men and women sit in extended circles murmuring like politicians—a daily ritual for most Icelanders.

***

We get back on the road again and drive past farms alternated with steep, mountainous descents until we take a right and drive into the northwestern village of Hvammstangi standing right next to the sea. The Arctic has turned rough again, and the wind has picked up after an afternoon’s rest. We struggle to pitch our tent against the strong currents but finally manage to make it steady for our last night out in the open. After dinner, we venture out to spot the Milky Way. As we train our eyes on the northern sky, dark over the sea, we notice it dapple with green spreading like an approaching wave. The wave flickers, fades, recedes, darkens and reappears until it dances ever so slightly. A streak of faint light spills slowly illuminating the sky with a tender, iridescent glow. The aurora comes alive for us—we watch, our eyes fixated.

All flights between Delhi and Mumbai and Reykjavik require at least one layover at a European gateway city such as Amsterdam, Frankfurt, or Paris.

Indian travellers need a tourist visa to visit Iceland. Applications for the Schengen visa can be made online through VFS (dk.vfsglobal.co.in) and relevant documents (list on website) must be handed in at the visa application centre in person. The 3-month tourist visa costs Rs4,680 (plus Rs780 service fee), and takes about 15 working days to process.

Camping

The best time to camp in Iceland is Jun-Sept. Temperatures in June through August hover at 15-20°C, whereas night temperatures in September can dip to 5°C. September is usually the start of the Aurora season too, though there are no guarantees; weather is pretty unpredictable across seasons here.

Between May and August, the tiny island of Lundey, just off Húsavík, hosts nearly 2,00,000 Atlantic puffins, who gather here to breed. Photo By: FedevPhoto/iStock/Getty images