#mixtec puebla

Text

A twin-chambered Mixtec tomb discovered in San Juan Ixcaquixtla, Mexico, reveals the secrets of ancestor worship and funerary rituals amongst ancient traders.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Important, but also the racism came out here in this reply I got:

Like wtf is this person's problem. Can't even see indigenous people take pride in their roots without being racist, smh. Really be here using the derogatory and racist "indio," huh. Just proves the point in the TikTok. And the worst part is they are part of different minority groups and decide to act like a clown:

Proud indigenous Zapotec forever 🇲🇽

Fck racists and racism.

#🇲🇽#this clown also said they were northern mexican and are superior to 'indios' so this racism in mexico against indigenous people also needs#to be addressed and talked about#racism#mexico#native#indigenous#oaxaca mexico#puebla mexico#mixtec#zapotec#discrimination against mexicans

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pedestal bowl, Mixtec-Puebla, 10th-16th century

from The Cleveland Museum of Art

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Representation of a Skull.

Culture: Mixtec-Puebla

Region Central plateau (?), Mexico

Period : Late Postclassic

Date: A.D. 1200-1521

Medium: Carved obsidian, inlaid with shell and bone

#history#museum#archeology#archaeology#mesoamerica#mexico#mexican#Mixteca-Puebla#late Postclassic#obsidian#skull#representation of a skull#a.d. 1200#a.d. 1521

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Repost @archaeologyart

Vessel in the Shape of an Eagle. Place of origin: Mexico, Puebla, Tlaxcala, or Oaxaca, Nahua or Mixtec Period: Late Postclassic Period Date: 1250–1521 Medium: Ceramic with pigment.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vessel in the Shape of an Eagle. Place of origin: Mexico, Puebla, Tlaxcala, or Oaxaca, Nahua. Culture: Mixtec. Period: Late Post classic Period. Date: 1250–1521 Medium: Ceramic with pigment.

Eagle effigy vessel. Date: ca. A.D. 1450. Period: Late Postclassic. Place of origin: Eastern Nahua. Medium: Ceramic with polychrome slip. Collection: Princeton University Art Museum.

Ancient terracotta horse on wheels from Cyprus. Possibly dating to 6th century BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 74.51.815.

Acrobat Vessel. Date: c. 2nd century BC–3rd century AD. Geography: Mexico, Mesoamerica, Colima. Culture: Colima Medium: Ceramic. Collection: The Met.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold skull and shell bead necklace, Mixtec or Puebla, 900 - 1500 AD

from Dumbarton Oaks

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skull-Shaped Censer

Mexico, Mixtec-Puebla, 1400–1521

Ceramics

Slip-painted ceramic

LACMA

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sinaloan businessmen arrive in Puebla, announce a pig farm and it turns out to be a drug laboratory

United and organized, the residents of this Mixtec municipality of Puebla managed to remove from their territory supposed Sinaloan businessmen who arrived with the pretense that they would invest in a pig farm, when in reality they installed and operated a laboratory for the production of synthetic drugs.

The “La Cástula” area, where the alleged businessmen left 51 50-liter drums and 28…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Blog Post #5

With the country that I am studying, there are many different types of languages. For example, the English language came from England which means that we talk more of a slang English. That is how it works over in Mexico. When we think about speaking Spanish, that originated from Spain. According to Native-languages.org there are about 30 different forms of Spanish throughout Mexico. They are:

Language name

Country/region spoken

Approximate number of speakers

1. Spanish

Throughout Mexico

110 million

2. Nahuatl

Mostly central Mexico

2 million

3. English

Throughout Mexico

2 million

4. Mayan languages

Mostly southeastern Mexico

1.5 million

5. Mixtec

Southwestern Mexico

475,000

6. Zapotec

Oaxaca and surrounding area

450,000

7. Otomi

Eastern Mexico

285,000

8. German and Plautdietsch

Various communities throughout Mexico

275,000

9. Totonac

Eastern Mexico

240,000

10. Mazatec

Oaxaca and surrounding area

220,000

11. Mazahua

Mexico State

150,000

12. Chinantec

Oaxaca and Veracruz

135,000

13. Mixe

Oaxaca

130,000

14. Purepecha

Michoacan

125,000

15. Tlapanec

Guerrero

120,000

16. Tarahumara

Northwestern Mexico

85,000

17. Zoque

Chiapas and surrounding area

60,000

18. Tojolabal

Chiapas

50,000

19. Amuzgo

Oaxaca and Guerrero

50,000

20. Chatino

Oaxaca

45,000

21. Huichol

Durango and surrounding area

45,000

22. Popoluca

Veracruz and surrounding area

40,000

23. Mayo

Sonora and Sinaloa

40,000

24. Tepehuan

Durango and surrounding area

35,000

25. Triqui

Oaxaca

30,000

26. Popoloca

Puebla

20,000

27. Cora

Nayarit

20,000

28. Huave

Southeastern Mexico

18,000

29. Yaqui

Sonora

17,000

30. Cuicatec

Oaxaca

13,000

If you take Spanish classes in high school or even college, then you learn the proper Spanish. When I talk to my co-workers, there are times that people cannot understand one another as there are different words for different things, depending on their slang. If we relate that to how we talk to each other in America, depending on where you go in the country they have different slang. They not only pronounce words differently, but if you use the word pancakes for example, to them it is hotcakes. This is just the tip of the ice berg, but point being where ever you go, there are different language styles.

0 notes

Photo

Gold Lip Plug in the Form of an Eagle Head (teocuitcuauhtentetl)

ARTIST CULTURE Mixtec

PERIOD Late Postclassic period, c.1200–1521

DATE c.1200–1521

POSSIBLY ASSOCIATED WITH Puebla or Oaxaca, México

Provenience unknown, possibly looted

With its exquisitely detailed feather arrangement around the head, prominent eyes, and menacing claw-like beak, this beautifully cast gold eagle head would have been worn by a warrior preparing for battle or ritual ceremony. The labret would have been inserted through a hole in his lower lip, with the radiance of the metal reflecting the light of the sun. Metalworking in central Mexico was probably introduced to the Mixtecs as a fully developed art from South America sometime in the thirteenth century. The neighboring Aztecs purchased such objects from their neighbors to use in sacred and political rituals; they called such objects teocuitlacuauhtentetl.

SLAM

#archaeology#arqueologia#mixtec#mesoamerica#oaxaca#puebla#mexico#gold#lip plug#piercings#eagle#aguila#art#arte#history#historia#native american

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Mixtecan Tree of Life

Growing out of the body of Tepeyollotl - the masculine jaguar god of the Earth; Jaguars representing primordial Earth. The eagle representing one of the first sons of humanity, roost atop the tree where a lake is formed, to give rise to creation.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

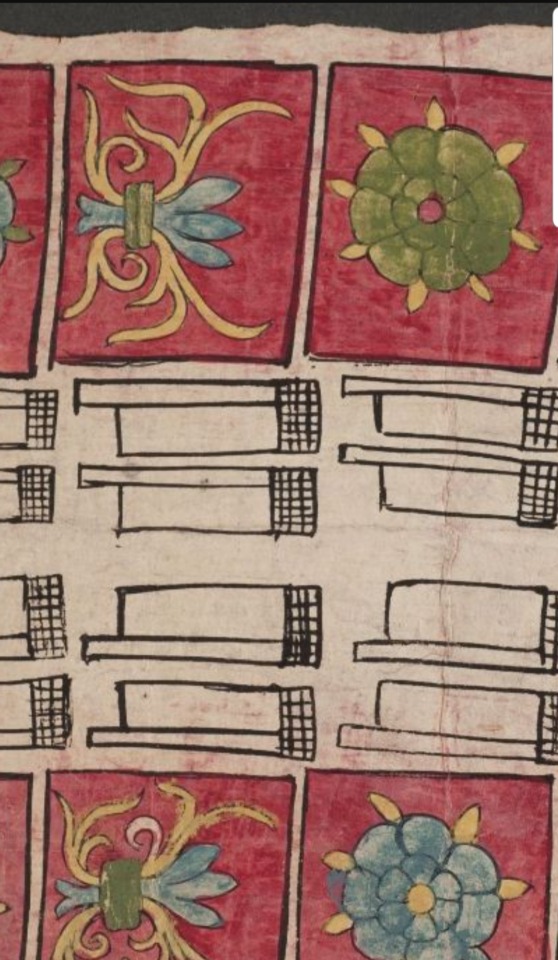

For centuries, the Indigenous cultures of present-day Mexico manufactured a brilliant red colorant called "prickly pear blood."

Nocheztli was the name the Mexica (Aztecs) gave this red colorant in their language Nahuatl. That is because in Nahuatl, the cacti were called nopalli and nochpalli, and their fruits were called nochtlí. Thus nocheztlí means blood (eztli) of the cactus (nochtlí,) or "prickly pear blood."

The colorant was actually made, however, from a parasitic insect of the prickly pear cactus, rather than the red prickly pear itself. The vivid carmine red color obtained from this insect evoked the image of blood and the juice of the red fruit.

The insect from which the dye is obtained is popularly called cochineal grana. Its scientific name is Dactylopius coccus . In Nahuatl it was called nocheztli which means "nopal blood" and in Mixtec ndukun which means "blood insect".

Both the insect and the colorant are known as cochineal.

Each pre-Hispanic indigenous culture had a different name for the insect. This ethnolinguistic element indicates the knowledge and early use of coloring by different ethnic groups before the arrival of the Spanish.

The colorant made from the cochineal insect was an astonishingly vivid red. Red was an important color for Mesoamerican cultures as it signified blood, and therefore life.

Indigenous peoples had many uses for it including as a medicine, a cosmetic, a dye for textiles, and a paint for hand-drawn manuscripts.

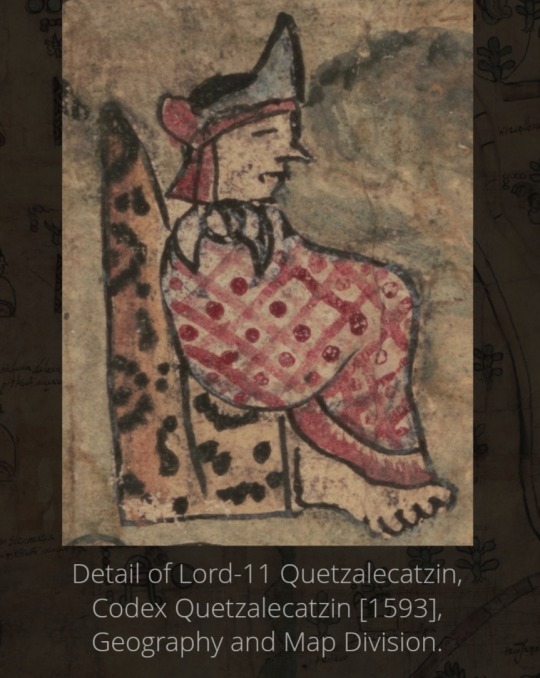

Mesoamerican manuscripts are important because they give insight into the people represented on them, as well as aspects of their culture. These colorful manuscripts also shed light on the expertise of the Indigenous craftspeople that made them.

The Library of Congress has three significant 16th-century Mesoamerican manuscripts that were all painted with carmine red: the Huexotzinco Codex, the Oztoticpac Lands Map, and the Codex Quetzalecatzin.

But what do we know about cochineal?

Cultivation of Cochineal

Cochineal was primarily cultivated by individuals from cactus plots found on their lands. The production of cochineal was time-consuming and involved several steps.

First the cacti were planted and allowed to grow for up to three years in order to host the insects. After the cacti reached the appropriate size, the Indigenous farmer attached nests containing female insects to the cacti. For 90 to 120 days cochineal insects were allowed to infest the host cacti. After this period of infestation, harvesting involved removing the insects from the cacti by hand with the aid of a pointed stick or a brush. Harvesting domesticated cochineal occurred two or three times per year.

Interestingly, only female insects were harvested because the component responsible for the red dye is solely carried by wingless females. The female of this species, whose life cycle is three months, is the one that contains carminic acid, a substance that is synthesized as a dye. The insect uses this substance as a defense mechanism against predators such as ants. For its part, the male does not require this defense since its vital cycle is brief, it is reduced to a week in which it fulfills the reproductive function and then dies.

A glimpse into cochineal cultivation is provided by the French botanist Nicolas-Joseph Thiéry De Menonville who published an account of his travels in 1777 to Oaxaca to obtain, albeit illegally, the insect for France.

"On arriving at Galiatitlan, I saw a garden full of nopals, and had no doubt I should there find the precious insect I was so desirous to examine. I therefore leapt from my horse, under pretense of altering my stirrup leathers, entered the grounds of the Indian proprietor, began a conversation with him, and enquired to what use he put those plants? He answered, “to cultivate la grana.” I seemed astonished, and begged to see the cochineal; but my surprise was real when he brought it to me, for instead of the red insect I expected, there appeared one covered with a white powder. I was tormented with the doubts I entertained, and to resolve them bethought me of crushing one on white paper; and what was the result? It yielded the truly royal purple hue.”

Grana is the Spanish term for cochineal that translates as "grain," possibly because the dried cochineal insect look like grains or seeds.

What then do we know about how the brilliant carmine colorant was made from the cochineal insect?

Cochineal Colorant Preparation

Sixteenth-century sources provide eyewitness accounts of the production of Indigenous Mexican artist materials. One of the most important sources is the Florentine Codex, or The General History of the Things of New Spain, compiled by Franciscan Friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Twelve books describe the culture and peoples of central Mexico, with detailed descriptions in Spanish and Nahuatl, as well as illustrations of artists materials like cochineal.

After harvesting, the insects were then prepared for processing into a colorant. The first part of the process involved killing the cochineal insects. This was accomplished by drying in the sun, heating in ovens or on hot plates, boiling, or steaming. Regardless of the method employed, the end result of this process was dried insects.

To make a red dye or paint, the dried silver cochineal "grains" are ground into a powder that is then boiled in water. Since the cochineal is an organic colorant, its coloring agent carminic acid must be stabilized with the addition of a mordant, a metallic salt. Powdered alum (potassium aluminum sulfate) was a mordant commonly used by Mesoamerican craftspeople.

Cochineal is sensitive to changes in pH, and as such, its color can vary. Cochineal colorants can range from orange when an acid, like vinegar, is added to the recipe to purple when a base, like ammonia, is added.

The primary uses for cochineal were as a dye for textiles and as a paint. To make a paint, the cochineal insects were soaked in water, ground into a paste with alum, and formed into tablets that were allowed dry.

Tablets of cochineal paint, as well as other paints and artist materials, were made available to artisans in markets throughout Mexico. It is likely that Indigenous scribes painted the red areas on manuscripts with cochineal tablets obtained from these markets.

A large variety of items were sold in Mesoamerican markets including food, raw materials, and artist pigments. The largest market was in Tlatelolco, a neighborhood in present-day Mexico City. Descriptions of the Tlatelolco market were published by Spanish conquistadors Hernán Cortés and Bernal Díaz who were astounded by its large size and the variety of items sold there.

Markets remain an important cultural tradition in Mexico to this day.

Mesoamerican Manuscripts at the Library of Congress

The Codex Quetzalecatzin resides in the Geography and Map Division. Created circa 1593, it is a genealogy map showing the ancestral lands of Lord-11 Quetzalecatzin and his descendants, the de Leon family, between the years 1480 and 1593. It is also known as the Mapa de Ecatepec-Huitziltepec because the de Leon holdings ranged from Ecatepec (near Mexico City) to the north, to Huitziltepec in Oaxaca to the south, with southern Puebla in between.

An Indigenous scribe, or scribes, likely created the codex because it is drawn in a mostly Indigenous artistic style with pictographs that convey information relating to space and time, and toponyms (place-glyphs) relating to specific locations.

Codex Quetzalecatzin

Brilliant carmine red was liberally painted all over the Codex Quetzalecatzin.

The color red is prominently used on the garments of the Indigenous elites. A rich red decorates the borders of the noble women's blouses and skirts and the cloaks of the noble men. Not surprisingly, Lord-11 Quetzalecatzin has the most splendid garments of all with his richly patterned red cloak and headdress.

It is not surprising that red paint appears on the codex in many areas, since Puebla and Oaxaca were primary regions of cochineal cultivation during the 16th century. As nopal cacti are prominent features on the codex, it is possible that the de Leon estate produced cochineal.

The Oztoticpac Lands Map, also part of the Geography and Map Division collections, was created around 1540. It concerns the litigation of the estate of the Texcoco lords after one of their members, Don Carlos Ometochtli, was executed for idolatry. Texcoco, a neighbor to Mexico City, was a partner to the Mexica (Aztecs.) The map depicts the Palace of Oztoticpac, land plots of villagers.

Oztoticpac Lands Map

Color was sparsely used on the map, and has faded over the years. Purplish-red lines and Indigenous counting numerals (bars and dots) were used to denote the borders and size of lands owned by the Texcoco nobility.

The Huexotzinco Codex is part of the Harkness Collection in the Manuscript Division. It is one of the earliest Mesoamerican manuscripts from the early colonial era of Mexico. As such, it is a thoroughly Indigenous manuscript as its story is told through pictographs showing the types of tribute items and the Indigenous counting systems.

The Huexotzinco Codex was created in 1531 for the legal case that conquistador Hernán Cortés brought against three members of the first Spanish colonial government in Mexico. The case accused the three government officials of stealing from Cortés by demanding excessive tribute from the people of Huexotzinco when he was in Spain. After the Spanish invasion, Cortés considered the land, natural resources, and the people of Huexotzinco to be his property because the Huexotzincas allied themselves with him during the war against the Mexica. Included in the court proceedings are eight Indigenous paintings submitted as evidence that depict the tribute handed over to the officials.

The eight paintings were produced by Indigenous scribes with Indigenous materials. While seven of the paintings are painted with red, vivid carmine red features prominently on two of them.

Huexotzinco, in the Mexican state of Puebla, was a major producer of cochineal in the 16th century.

Huexotzinco Codex

Painting III shows twenty cotton cloths, each richly decorated with an Indigenous calendrical pictograph (Rabbit, Reed, or Flower) representing the count of years or days. A brilliant red background offsets the pictographs. Notably red was used as the background on all of the twenty cloths and was also the most-used colorant.

Colorful, ornamented clothing of cotton and rabbit fur were reserved for the elites of Mesoamerican societies. Thus the carmine red textiles prominently featured on two codex paintings provide insight into the Huexotzinco community as well as the artisans working there.

The three Library of Congress Mesoamerican manuscripts (the Codex Quetzalecatzin, the Oztoticpac Lands Map, and the Huexotzinco Codex) have a shared history. They were created during the first century of the newly formed Spanish colony of Mexico.

Another shared aspect found on all three manuscripts is the use of carmine red paint to illuminate features that were important and specific to the people depicted on them, and to the scribes who painted them.

While visually the reds on the three Library of Congress manuscripts appear to be cochineal, to date material analysis has only confirmed the red on the Huextzinco Codex paintings to be cochineal. Hopefully future scientific analysis will also identify the reds of the Codex Quetzlecatzin and the Oztoticpac Lands Map.

While Spain profited from the production and export of cochineal, credit must be given to the Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples who developed this stunning red, this "prickly pear blood," and gave it to the world.

Once discovered by Spaniards, cochineal became one of the most valuable commodities in Europe. In 1758 alone, Oaxaca exported more than 1.5 million Spanish pounds of it for various uses, including the dying of fabrics for red uniforms worn by British soldiers. It was the most exported from New Spain during the 16th century, after gold and silver.

For centuries Europe sought an intense red that would last over time in textiles such as wool and silk. They had not found a dye with these characteristics until the discovery of cochineal. It was so prized, Spain kept secret that it came from a bug instead of a plant.

The Italian dyers of the 16th century, based in Venice and Florence, were the main buyers of dyes.

Later, in later centuries, this changed and it was the French, the Dutch and later the English who bought the scarlet, both in formal and informal trade through smuggling.

Apart from the textile industry, which is where it had its most widespread use, famous painters such as Rubens, Velázquez and El Greco, among others, also used pigments based on the cochineal grana to add unique colors in their works.

Museum conservation and restoration laboratories in different parts of the world have confirmed the presence of the dye bug in many important works.

The cochineal cochineal from New Spain produced a "boom" in European markets , says Huémac Escalona. It was the second good that generated the most profits for the people involved in its trade, both Spanish and Indian.

The Spanish crown retained the monopoly of this product throughout the colonial period; For this, it kept the secret of its nature and production, preventing the live insect from leaving New Spain. When the Spanish referred to the large cochineal they always used terms that referred to agriculture, so that competitors from other nations believed that it was a vegetable product, a fruit of a plant or a seed.

Today it can also be found as a natural food coloring.

Production of dye in Oaxaca

In the 16th century and the first part of the 17th century, the most intense production of cochineal was located in the Tlaxcala and Puebla areas. Oaxaca was the cradle of domestication of the large cochineal; it also produced in those years but not so intensely. It was not until the second half of the seventeenth century when its production increased, until it produced 99 percent of the scarlet that was exported to the entire world in the eighteenth century.

The relationship between indigenous producers and Spanish merchants around the grana was not without tensions and conflicts, despite this, the wealth it generated allowed that relationship to last over time.

The historian recalls that the indigenous communities accepted to produce the cochineal because it allowed them to have their own social organization and allowed them to have money for their festivals and to pay taxes. Although these were impositions of the colonial regime, these burdens were assumed in such a way as to allow them to have an organizational structure according to their traditions.

The rearing of the insect was an economic activity in which the whole family participated and could be combined with other tasks. The production and trade of grana articulated the economy of various regions of Oaxaca. There were towns that specialized in grana, others combined its production with the manufacture of blankets or the cultivation of corn and wheat. While others were dedicated to making the various containers where the dye was transported.

Most of the indigenous peoples, for their part, became producers of the dye because it meant a more or less secure way of obtaining resources to cover their community expenses and cover tax burdens. This was not exempt from the enrichment of sectors of its population. However, it was not the norm but rather the exception.

Grana connected the economy of societies so different and so far away : Indigenous peoples from the Oaxacan regions with European, African and Asian societies. For the Oaxacan indigenous people, the scarlet was the product that gave them benefits but also caused them discomfort. The constant international demand for dye led to the adaptation of their collective life, governed by a set of beliefs and traditions of their own, to an intense production system.

The traces of the scarlet in Oaxaca are everywhere: in civil and religious public buildings, in merchants' houses, in textiles, in its archaeological remains, in pre-Hispanic and colonial documents, painted with pigments made from the cochineal or where its production and trade were registered. It shows the importance that the precious dyeing insect known as grana cochineal had for the history of Oaxaca and Mexico.

A red color, really Mexican?

In recent years, there has been a debate about the American zone of origin of the dye . A group of scholars assured that the cochineal was domesticated in South America, in the Andean area, due to the discovery of textiles dyed with this dye in various archaeological sites and whose dating dates back to the first centuries after Christ.

Other specialists affirmed that it was in Mesoamerica, specifically in Oaxaca, where the first domestication of the insect was carried out together with the nopal. It is believed that it passed from Mesoamerica to Central America and from there to South America through the cabotage trade.

Recently, a scientific study was carried out that analyzed the mitochondrial DNA of the cochineal cochineal samples from Oaxaca and Peru. The results showed that the genetic variety from Oaxaca is older and more diverse. This confirms that the domesticated dyeing insect is native to the Mesoamerican region corresponding to the current state of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico.

Sources: (×) (×) (×)

#indigenous#mexico#aztec#france#Nicolas-Joseph Thiéry De Menonville#animal#insect#spain#europe#hernan cortes#🇲🇽#italy#dutch#new spain#history#mexican history#oaxaca#puebla#oaxaca mexico#puebla mexico#long post#asia#africa#south america#central america#latin america#peru#nahuatl

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold necklace, Mixtec-Puebla, 950-1520 AD

from Dumbarton Oaks

409 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Vessel in the Shape of an Eagle.

Place of origin: Mexico, Puebla, Tlaxcala, or Oaxaca, Nahua or Mixtec

Period: Late Postclassic Period

Date: 1250–1521

Medium: Ceramic with pigment.

#ancient art#history#museum#archaeology#ancient america#pottery#vessel#vessel in the shape of an eagle#eagle#mexico#puebla#Tlaxcala#Oaxaca#nahua#mixtec#late Postclassic period#1250#1521

545 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like certain colors, crests, and beadwork can give away your tribe, clan, and even family in the northern nations, the style and pattern of textile you wear in Mexico and Central America give away what people, and what town you come from. These patterns for weaving and brocading have been passed down for decades, mee notably in Mesoamerica, such as with the Tenek, Otomi, Maya, Nahua, Mixtec, Zapotec, and more Indigenous groups.

Otomi girl wearing a distinctive quechquemitl from San Pablito Pahuatlán, Puebla.

Most often, you see these unique designs woven into shirts, quechquemitls (shawls), rebozos, sashes, and most famously, huipiles. These traditions of weaving are extremely, extremely old, with some designs and styles unique to certain areas dying out quickly due to lack of interest, and some textile traditions being almost entirely gone (tilmatlis, or tilmas, being one of them).

Maya woman from Tenejapa, Chiapas.

Personalized textiles (such as huipiles) can have stories of folklore and history woven into them, but most often, they can tell your social status, such as how many animals you own, your marriage status, or other social standings. These clothes can be simple, or elaborate, but what matters is how we have kept these clothes for hundreds of years and how important these traditions are.

220 notes

·

View notes