#heidi ann heiner

Text

I've now reached the last of the main list of Cinderella stories from Cinderella Tales Around the World. The book is nowhere near over, though: after this it goes into the various "subtypes" of Cinderella, such as Donkeyskin.

The last few "official" Cinderella stories in this book are from Mexico and Chile. I was disappointed not to see more South American versions, and particularly that there were none from Brazil for @ariel-seagull-wings. But the Donkeyskin tales later in the book do include a Brazilian version, which I look forward to sharing!

Meanwhile...

*As in the versions from the Philippines, the heroine is named Maria in all three of these Latin American tales.

*The Mexican version is called Maria Cenzia, or "Cinder-Mary." The title character is a homeless orphan who lives in an ash-hole belonging to a household of black Moorish witches. They eventually discover her, take her in as a servant, and send her to the river with a black sheepskin, ordering her to wash it until it's white. But a lady appears and magically does the task for her, then gives her a magic wand to grant her wishes and puts a shining star on her forehead. When the jealous daughter of one of the witches sees this, she takes a black sheepskin to the river too, but the lady puts an ugly growth on her forehead instead of a star. Maria later uses her magic wand to give herself finery to wear to church and to give herself wings to fly home before the witches can catch her. She loses a shoe, of course, which leads to her marriage to the prince. But then the witches turn her into a dove with a magic pin. Yet one day, her father-in-law the king finds her and takes out the pin, breaking the spell, and when all is revealed, the witches are burned at the stake.

*The two Chilean versions, Maria the Cinder-Maiden and Maria the Ash-Girl, are nearly identical to each other and very similar to Maria Cenzia too. Maria persuades her father to marry a seemingly-kind widow with a daughter of her own, but is abused afterwards. She has a pet cow, which the stepmother spitefully has killed, but inside its body Maria finds a magic wand. She then has to wash the cow's organs in a stream, but they fall in and are swept away. An old woman comes along and offers to get them for her, and in return Maria cleans her house and cooks supper for her; for this, the old woman gives Maria a shining star on her forehead. The next day the envious stepsister has her own pet cow killed, takes the organs to the stream, and loses them on purpose, but she shows the old woman no kindness, and so she receives a turkey wattle on her forehead instead of a star. Some time later, there's a ball at the royal palace. Maria uses her wand to give herself finery and a coach, and of course she loses a shoe, and the prince uses it to search for her. The stepsister binds her own foot with tight bandages to make the slipper fit, but either a dog or a parrot alerts the prince, and Maria is found.

*It's interesting that the motif of the heroine receiving a shining mark on her forehead (a star, a moon, or a jewel) is found in Cinderella tales from both Latin America and Iran, yet rarely seen elsewhere. My guess is that the motif originated in the Middle East, was brought to Spain by the Arabs, and then traveled from Spain to Latin America.

*This is probably as good a time as any to discuss another recurring theme I've noticed. While around the world it varies whether the heroine's abusers are punished, forgiven, or neither, it seems that when they are punished, the worst punishment usually falls on the (step)sister(s), not the (step)mother. Just look at the Grimms' version: the stepmother is Aschenputtel's main antagonist, and she abuses her own daughters too by forcing them to cut off parts of their feet, yet in the end she goes unpunished, while her daughters' eyes are pecked out by birds. Yet even in versions where the (step)mother does get a punishment, the more brutal killing, maiming, or permanent disfigurement tends to be reserved for her daughter(s). Some versions try to justify it by portraying the sisters as abusing Cinderella more than their mother does, but most don't bother. In many versions, the simple "crime" of being Cinderella's rival is treated as if it were worse than being her chief abuser.

@ariel-seagull-wings, @adarkrainbow, @themousefromfantasyland

#cinderella#fairy tale#variations#cinderella tales from around the world#heidi ann heiner#mexico#chile#tw: violence#tw: racism

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

i just wanted to ask, where do you find fairy tales? i never knew so many existed and i feel like i stumbled upon an entire world previously hidden, but im not sure how to get into them apart from your blog since, well, i feel like ive missed a class on how to locate fairy tales

Aw, I'm honoured I could be your introduction!

In my heart of hearts I will always believe fairy tales should be either read in books or told to you, but there are great websites where you can find many of them collected! (That also has the advantage of not needing to know a specific collector or culture you're interested in, which you do kind of need to choose a book.)

If you want a full database of all kinds of fairy tales from all over, try Heidi Anne Heiner's website:

If you want to read several stories from various places that fit into the same sort of category, have a look at Ashliman's folklore page:

I hope you have fun discovering! <3

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beauty and the Beast Liveblog: Intro Post

Because I'm under the delusion that I don't already have enough hobbies and projects to keep me busy, I've decided to do another liveblog! This time, I'm reading "Beauty and the Beast" written by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve and published in 1740.

I'll be reading the translation by Ernest Dowson, thanks to the book "Beauty and the Beast: Tales From Around the World" edited by Heidi Anne Heiner of Sur La Lune fame.

For context: I'm an American who grew up watching Disney's 1991 animated Beauty and the Beast; I have been a fan of fairy tales for decades; I was an English major; I have a little knowledge of 17th-18th century France. I know a few of the details from Villeneuve's original story but am mostly going into this blind. I'm excited to find out what I'm already familiar with and what takes me completely by surprise.

For anybody who's not in the mood for fairy tale nerdery, the rest of my posts will be under the tag beauty and the beast villeneuve liveblog so I don't spam the "beauty and the beast" tag.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Gift of Nothing. Fun Xmas Prank for Friends.

Take "Less is more." to the max with the hilarious Gift of Nothing!

Some people think something is better than nothing, well think again! Introducing the fabulous Gift of Nothing. It's the best gift for the dad who has everything, the mom who always says "You don't need to get me anything, sweetie." or the girlfriend who is definitely testing you when says she doesn't want anything for her birthday.

Make it the gift that keeps on giving!

Your husband may have bought it for you on Valentine's Day, but watch out because Xmas is right around the corner and he's next! Pass this hilarious gift idea around the family and see who gets nothing next. Men and women alike will get a kick out of this extra special gift - even grandpa could get in on this action! Other presents can't compete with this ultimate unforgettable silly gift.

Family friendly gift everyone can enjoy.

Enjoy some good old fashioned family fun with the funniest fake gift! Appropriate for kids, teenagers, and adults of all ages! Whether it's for a bday, Father's Day, Mother's Day, or Xmas, nothing could be better than this. This anti-gift contains no nuts, no meat, or anything at all so even vegans and people with peanut allergies can enjoy!

Office making you participate in Secret Santa?

Just bring nothing! The Gift of Nothing, that is. Share laughs with coworkers when you break this out at the office White Elephant Christmas party. This weird (and definitely not stupid or useless) toy will be a smash hit this holiday season.

What’s in the box?

You will receive one (1) "Gift of Nothing" novelty package with nothing inside.

Lifetime 100% money-back satisfaction guarantee!

If you aren’t completely satisfied with your order, simply email us, and we will respond within 24 hours to make it right even on the weekends. We absolutely guarantee your satisfaction or your money back!

Some customers review:

Ray Rauch

Great white elephant gift or the gift for someone who said they wanted "Nothing" for the holidays. This fits the bill super nicely. I think they are going to love that I was thoughtful enough to get them nothing and that's all for this Christmas season. It's really what they deserved after all.

Jess

I love this gag gift and laughed at all the clever labels describing what's in it/what it's for (nothing of course) etc.. What's better than to make someone laugh and put a smile on their face? It's peanut free, sugar free and emotion free! I love it. I would recommend this.

Heidi Anne Heiner

Okay, this is hilarious and we giggled over it all weekend. I got it to give to my dad for Christmas and have already teased him that it is something that he's always wanted. It's true since he is not big on getting stuff and doesn't care about receiving gifts. So I finally found his perfect gift. This will make the entire family laugh when he opens it up. I like that I can keep teasing that it is sugar free, gluten free, etc. in the meantime.

If you care about this product. Click here: https://gift-of-nothing.com/

0 notes

Text

SBWC: 8 / 24 / 18, Books and Flowers

#slytherinbookwormchallenge#the frog prince#fairytales#books#book photo challenge#august#surlalune fairy tale series#heidi anne heiner#books and flowers#booklr#surlalune fairy tales

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you know that there is a version of Beauty and the Beast where the Beast is a white wolf???

The Beast is a White Wolf???

THE BEAST IS A WHITE WOLF???

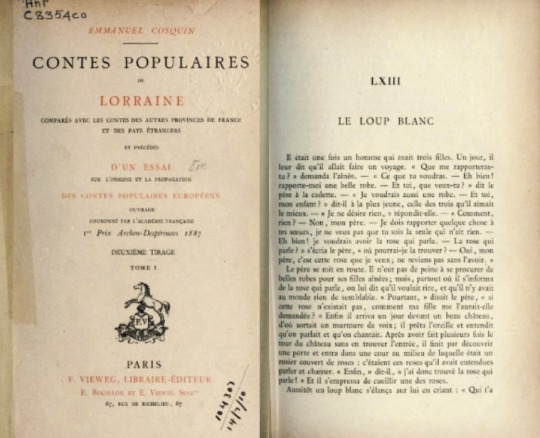

Yes, there is a French version of Beauty and the Beast called 'Le Loup Blanc' (The White Wolf) that appears in the book Contes Populaires de Lorraine by Emmanuel Cosquin, published in 1887.

And if I think about a white wolf is really hard not to associated it with Jon Snow and his own white wolf, Ghost.

As I said before, Sansa and Jon fit perfectly in the classic roles of Beauty and the Beast, so this new discovery is really interesting.

More under the cut.

There are various online sources of 'Le Loup Blanc' in French, its original language. Sadly, I haven’t found an english translation of the complete tale, just a synopsis in Spanish and an english translation of the ending.

But, from the synopsis in Spanish and the google translation of the French sources, I can tell you the following:

A father has three daughters and before he goes on a trip, his two older daughters ask him for gifts.

The youngest daughter asks for nothing, but at his father insistence she asks him to bring her a “talking rose”.

The father gets surprised by his youngest daughter’s request because he never heard of a “talking rose” before, but he accepts the request anyway.

As expected, the father can't find a “talking rose” anywhere, not until he found a beautiful castle where he discovers a bush of roses that could talk and sing.

The father takes one of the talking roses but at that moment the White Wolf appears saying that the father must die for taking the rose.

The father begs for his life and tells the White Wolf that his youngest daughter asked him to bring her a talking rose.

At the father’s confession, the White Wolf tells him he will be pardoned and allowed to keep the talking rose only if he accepts to bring the first person he meets at home to him.

The first person the father meets at home is his youngest daughter.

The girl accepts to go to the White Wolf’s castle in her father’s place. The father takes the girl to the castle.

The White Wolf reveals, among other details, that he was cursed to be a white wolf but only during the day. At night he returns to his human form.

The White Wolf asked them to keep his secrets.

The secrets are revealed at the end and...

...Unfortunately, the tale has an unhappy ending.

Talking about unhappy endings, Heidi Anne Heiner, the author of the book Beauty and the Beast Tales From Around the World, tells us:

Finally, the third and final unhappy ending in Beauty and the Beast Tales From Around the World is found in a tale that I translated myself for the book, The White Wolf. There are three tales by that title in the book, but this version was originally "Le Loup blanc” from Contes Populaires de Lorraine by Emmanuel Cosquin, a French tale. To my knowledge it has never been published in English translation before.

It is a short tale and is a straightforward ATU 425C (Beauty and the Beast) tale. But it is especially abbreviated for it ends like this:

After spending another night at the castle, the father returned home. The girl remained and soon began to enjoy the castle. She discovered all that she could desire, each day there were music concerts and nothing was forgotten for her entertainment.

However, her mother and her sisters were filled with anxiety. They said, “Where is our poor child?” and “Where is our sister?”

The father, upon his return, at first would not tell what had transpired, but in the end he yielded to their entreaties and told them where he had left his daughter.

One of the eldest visited the sister and asked her what had happened. The girl resisted for a long time, but her sister persisted and ultimately she revealed her secret.

Immediately, they heard horrible screams. The girl stood up, shuddering with fright. As soon as she went outside, the white wolf came to die at her feet. She then comprehended her mistake, but it was too late and she was unhappy for the rest of her life.

That one is particularly brutal for she has no second chances, no way to redeem herself for simply revealing the secret which most tales in this group provide so she can find redemption. Which makes it all the more fascinating. [Source]

How dare you?

Despite the unhappy ending, let’s talk about all the new information. Now we know that, according to Heidi Anne Heiner, there are at least three versions of Beauty and the Beast called “The White Wolf”, versions she compiled in her book, although I’m not sure if the three of them have the same sad ending.

The rose in this tale is not just a rose, but a talking and singing rose. Roses and Songs are two themes that reminds me of Sansa Stark.

The White Wolf being a secret prince reminds me of Jon Snow.

The prince's curse, being a white wolf during the day and returning to his human form at night, reminds me of Jon's ability of warg inside his albino direwolf, Ghost. It also reminds me of the possibility of Jon living inside Ghost before his resurrection.

Also, in the Show, during his proclamation as King in the North, Jon was called “The White Wolf”.

The promise of keeping the White Wolf’s secrets reminds me of Jon’s true parentage secret and Ned’s promise to protect him of the dangers its revelation could create.

In the tale, the White Wolf asks the father and daughter not to tell anyone what they see and hear at the castle, but both of them breaks their promise. While the father only reveals the castle’s location, the girl reveals the White Wolf true identity.

I know there is not certainty that the Books ending being the same as the Show ending, but this tale unhappy conclusion reminds me of what happened in the Show: Sansa revealing Jon’s true parentage and Jon not “entirely” forgiving her for doing that, no matter her good intentions.

There is also no certainty that GRRM knows about this particular version of Beauty and the Beast; this could be only an interesting coincidence.

On a happier note, I found this beautiful fan-art of the tale:

(Art credit: Le Loup blanc by Sieskja)

You can read the 'Le Loup Blanc' tale here (French - Complete Book), here (French - PDF), here (French - Complete Tale) and here (Spanish - Synopsis).

The author of the book Beauty and the Beast Tales From Around the World, also has a very extensive list of tales similar to Beauty and the beast that you can check here.

And on an even happier note, I must tell you that in many illustrations of Beauty and the Beast tales, Beauty is a redhead girl [you can see them here and here], and I will leave you with my favorite one:

This illustration came from: Boyle, Eleanor Vere. Beauty and the Beast: An Old Tale New-Told. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle, 1875.

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading list for 2020

2019 reading list

literature recommendations

last updated 7.1.2020

crossed = finished

bolded = currently reading

plain = to read

* = reread

+ = priority

ask if you want PDFs!

currently reading:

The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon by David Sylvester

We Eat Our Own by Kea Wilson

Frankissstein by Jeanette Winterson

Inferno by Dante Aligheri

novels (unsorted)

The Border of Paradise by Esmé Weijun Wang

+Justine by Lawrence Durrell

Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy

+Death in Venice by Thomas Mann*

The Robber Bride by Margaret Atwood

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco*

The Letters of Mina Harker by Dodie Bellamy

Story of the Eye by Georges Bataille

+Nightwood by Djuna Barnes

+Malina by Ingeborg Bachman

A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing by Eimear McBride

Monsieur Venus by Rachilde

+The Marquise de Sade by Rachilde

+A King Alone by Jean Giono

+The Scarab by Manuel Mujica Lainez

+The Invitation by Beatrice Guido

Operation Massacre by Rodolfo Walsh

She Who Was No More by Boileau-Narcejac

Mascaro, the American Hunter by Haroldo Conti

European Travels for the Monstrous Gentlewomen by Theodora Goss

Kiss Me, Judas by Christopher Baer

Possession: A Romance by A.S. Byatt

The Grip of It by Jac Jemc

Celestine by Olga Ravn

The Girl Who Ate Birds by Paul Nougé

The Necrophiliac by Gabrielle Wittkop

Possessions by Julia Kristeva

classics

The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio*

Purgatio by Dante Aligheri

Paradiso by Dante Aligheri

short story collections

The Wilds: Stories by Julia Elliot

The Dark Dark: Stories by Samantha Hunt

Severance by Robert Olen Butler

Enfermario by Gabriela Torres Olivares

Sirens and Demon Lovers: 22 Stories of Desire edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling

The Beastly Bride edited by Ellen Datlow

+Vampire In Love by Enrique Vila-Matas

Collected works of Leonora Carrington

Collected works of Silvina Ocampo

Collected works of Everil Worrel

Collected works of Luisa Valenzuela

theatre

+Faust by Goethe

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

Phaedra’s Love by Sarah Kane

nonfiction (unsorted)

Countess Dracula by Tony Thorne

+The Bloody Countess by Valentine Penrose

Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsebet Bathory by Kimberly L. Craft

Blake by Peter Akroyd

Lives of the Necromancers by William Godwin

A History of the Heart by Ole M. Høystad

On Monsters by Stephen T. Asma

+Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination by Avery Gordon

+Consoling Ghosts : Stories of Medicine and Mourning from Southeast Asians in Exile by Jean M. Langford

essays (unsorted)

When the Sick Rule the World: Essays by Dodie Bellamy

Academonia: Essays by Dodie Bellamy

‘On the Devil, and Devils’ by Percy Shelley

+An Erotic Beyond: Sade by Octavio Paz

poetry

+100 Notes on Violence by Julia Carr

academia (unsorted)

Essays on the Art of Angela Carter: Flesh and the Mirror edited by Lorna Sage

The Routledge Companion to Literature and Food edited by Lorna Piatti-Farnell, Donna Lee Brien

Cupid’s Knife: Women's Anger and Agency in Violent Relationships by Abby Stein

Traumatic Encounters in Italian Film: Locating the Cinematic Unconscious by Fabio Vighi

The Severed Flesh: Capital Visions by Julia Kristeva

Feast and Folly: Cuisine, Intoxication, and the Poetics of the Sublime by Allen S. Weiss

on horrror

Terrors in Cinema edited by Cynthia J. Miller and A. Bowdoin Van Riper

Robin Wood on the Horror Film: Collected Essays and Reviews by Robin Wood

Monster Theory: Reading Culture by Jeffrey Cohen

The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart by Noël Caroll

Dark Dreams 2.0: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film from the 1950s to the 21st Century by Charles Derry

Monsters of Our Own Making by Marina Warner

Monster Culture in the 21st Century: A Reader edited by by Marina Levina and Diem My Bui

the gothic

Woman and Demon: The Life of a Victorian Myth by Nina Auerbach

Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters by J. Halberstam

+Perils of the Night: A Feminist Study of Nineteenth-Century Gothic by Eugenia C. Delamotte

Art of Darkness: A Poetics of Gothic by Anne Williams

Body Gothic: Corporeal Transgression in Contemporary Literature and Horror Film by Xavier Aldana Reyes

On the Supernatural in Poetry by Ann Radcliffe

The Gothic Flame by Devendra P. Varma

Gothic Versus Romantic: A Reevaluation of the Gothic Novel by Robert D. Hume

A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful by Edmund Burke

Over Her Dead Body by Elisabeth Bronfen

The Contested Castle: Gothic Novels and the Subversion of Domestic Ideology by Kate Ellis

Gothic Documents: A Sourcebook, 1700-1820 by E. Clery

Limits of Horror: Technology, Bodies, Gothic edited by Fred Botting

The History of Gothic Fiction by Markman Ellis

The Routledge Companion to the Gothic edited by Catherine Spooner and Emma McEvoy

Gothic and Gender edited by Donna Heiland

Romanticism and the Gothic Tradition by G.R. Thompson

Cryptomimesis : The Gothic and Jacques Derrida’s Ghost Writing by Jodie Castricano

bluebeard

Bluebeard’s legacy: death and secrets from Bartók to Hitchcock edited by Griselda Pollock and Victoria Anderson

The tale of Bluebeard in German literature: from the eighteenth century to the present Mererid Puw Davies

Bluebeard: a reader’s guide to the English tradition by Casie E. Hermansson

Bluebeard gothic : Jane Eyre and its progeny Heta Pyrhönen

Bluebeard Tales from Around the World by Heidi Ann Heiner

religion

The Incorruptible Flesh: Bodily Mutation and Mortification in Religion and Folklore by Piero Camporesi

Afterlives: The Return of the Dead in the Middles Ages by Nancy Caciola

Discerning Spirits: Divine and Demonic Possession in the Middle Ages by Nancy Caciola

“He Has a God in Him”: Human and Divine in the Modern Perception of Dionysus by Albert Henrichs

The Ordinary Business of Occultism by Gauri Viswanathan

The Body and Society. Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity by Peter Brown

cannibalism

Eat What You Kill: Or, a Strange and Gothic Tale of Cannibalism by Consent Charles J. Reid Jr.

Consuming Passions: The Uses of Cannibalism in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe by Merrall Llewelyn Price

Cannibalism in High Medieval English Literature by Heather Blurton

+Eating Their Words: Cannibalism and the Boundaries of Cultural Identity edited by Kristen Guest

Dinner with a Cannibal: The Complete History of Mankind’s Oldest Taboo by Carole A. Travis-Henikoff

crime

Savage Appetites by Rachel Monroe

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

The Mind Hunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit by John Douglass

theory/philosophy

Life Everlasting: the animal way of death by Bernd Heinrich

The Ambivalence of Scarcity and Other Essays by René Girard

Interviews with Hélène Cixous

Symposium by Plato

Phaedra by Plato

Becoming-Rhythm: A Rhizomatics of the Girl by Leisha Jones

The Abject of Desire: The Aestheticization of the Unaesthetic in Contemporary Literature and Culture edited by Konstanze Kutzbach, Monika Mueller

The Severed Head: Capital Visions by Julia Kristeva

perfume & alchemy

Perfume: The Alchemy of Scent by Jean-Claude Ellena

The Perfume Lover: A Personal Story of Scent by Denyse Beaulieu

Past Scents: Historical Perspectives on Smell by Jonathan Reinarz

Fragrant: The Secret Life of Scent by Mandy Aftel

Das Parfum by Patrick Süskind*

Scents and Sensibility: Perfume in Victorian Literary Culture by Catherine Maxwell

The Foul and the Fragrant by Alain Corbin

+throughsmoke by Jehanne Dubrow

“The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Perfume” by Katy Kelleher

medicine

The Butchering Art by Lindsey Fitzharris

Finished

(Vampires): An Uneasy Essay on the Undead in Film by Jalal Toufic

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

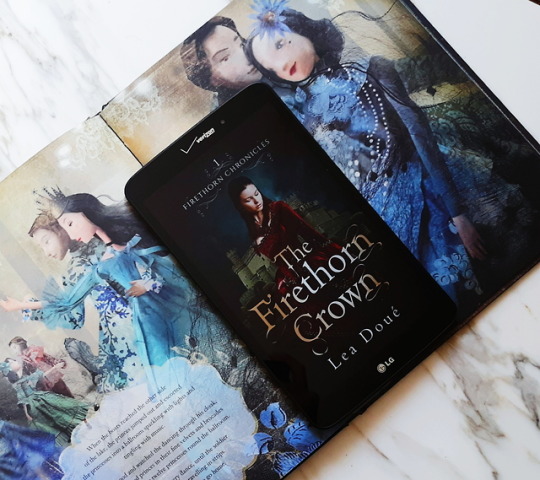

The Firethorn Crown by Lea Doué

Warning: Contains spoilers

Welcome back to Fairy Tale Friday! By popular vote, we are looking at another retelling of “The Twelve Dancing Princesses.” The timing couldn’t be better because this month marks the one year anniversary of this feature, and the first book I posted on was also a retelling of this tale. You can read that post here. Now let’s jump into The Firethorn Crown!

As a Retelling:

As with the majority of this tale’s retellings, The Firethorn Crown focuses on the eldest princess, Lily. This is common because in the Grimms’ version of the tale--which is the best known--the soldier marries the eldest. This is also the case with many variations, though in some it is the youngest instead. Also following the German version, Lily’s love interest, Eben, is a former soldier. Unlike in the various variations, Eben does not come into the picture after the princesses begin their nightly dancing. He is their guard and has known them for years, which provides a strong relationship between him and Lily from the beginning of the book.

Also like the German version and the majority of other variations, Doué’s princesses dance in an underground realm. However, the entrance the realm is in a different location than it is in most of the tales. Usually the entrance is in the princesses’ bedroom, often beneath the bed of the eldest sister. We can find this not just in the Grimms’ tale, but also in French, Russian, Romanian, and Danish variants, among others. The entrance to Doué’s underground realm, called the undergarden, is in a hedge maze in the royal garden. Most people avoid the maze since it’s dark and creepy, but the princesses enjoy playing in there. They discover the undergarden while running through the maze trying to avoid Lord Runson, an unwanted suitor of Lily’s. When they return each night, they have to sneak out of their room and into the garden. There are a few variants that involve the princesses leaving their rooms to attend the balls, usually by flight. In a Russian version called “Elena the Wise” the girls turn into doves while in the Hungarian “The Hell-Bent Misses” they fly on brooms. The way the princesses in this book sneak out is more similar to how the final suitors in most of the tales follow them: they turn invisible. Generally the suitor uses a magical article of clothing, such as a cloak or a cap, but in some versions he uses a flower from a magical plant. Doué’s princesses gain the ability to become invisible when holding hands during their first trip to the undergarden. They use this along with a series of distractions to get by the guards at their door.

Doué borrows the concept of a curse causing the princesses to dance from the French and Romanian tales. Most versions of this story are vague even by fairy tale standards, which allows her to create her own backstory behind the curse. Her villain is Tharius, a sorcerer prince cursed to live in the undergarden. He can only leave if someone willingly marries him, rather in the style of “Beauty and the Beast.” When Lily and her sisters enter the undergarden, he tricks them and lays a curse of his own to force them back each night so he can court Lily. The girls can’t speak about the curse, providing a reason for them to keep everything a secret, and Lily can’t speak at all outside of the undergarden. This does not come from any version of “The Twelve Dancing Princesses” that I know of, but it does have an origin in fairy tales such as “The Six Swans.” Lily can only break the curse by declaring her love and having it returned.

While Doué does use a lot from the original stories, she also makes a number of changes. The most interesting to me is the inclusion of the princesses’ mother. In every version of the tale, their mother is either dead or not mentioned at all. Every retelling I’ve encountered other than this has followed suit and killed her off, sometimes incorporating it into the plot, as in Princess of the Midnight Ball and Entwined. Not only is she alive in The Firethorn Crown, she is also a large presence throughout the story. In fact, it is her, not the king, who declares that anyone who solves the princesses’ mystery can marry one of them. This is done in a moment of anger, and she ultimately doesn’t mean it. However, it is said in front of witnesses, so she cannot redact it. In the original tale, depending on how you choose to read it, the king can be seen as anything from well-meaning yet overprotective to an overbearing patriarchal figure trying to control his daughters’ autonomy. Switching the father for the mother is a fascinating choice and is probably the most unique aspect of the book as a retelling. Perhaps Doué felt a story of tension between mother and daughter would resonate more with a modern, teenage audience. Whatever her reasoning, I liked the change!

This leads to another notable change: neither Eben nor anyone else stays in the princesses’ quarters to find out their secret. This plot point is featured in almost every version of the fairy tale, and I was surprised to see it left out here. I’m not sure why Doué didn’t use it, but it could be because the timeline is condensed. In the fairy tale, we get the impression that the princesses have been wearing their shoes out night after night for months, if not years. This provides enough time for each suitor to try and fail for three nights. The Firethorn Crown takes place over the course of a few days, which obviously isn’t enough time for any of that to happen. Another reason may be the issue of how creepy it is to let random men sleep in the princesses’ quarters. It’s kind of hard to swallow from a modern perspective. Even Eben, who is close with the girls, does not stay in their rooms. He doesn’t even follow them without their knowledge. When he goes to the undergarden, they actually bring him along so he can help. The condensed timeline also causes one last change: the princesses don’t go through nearly as many shoes. By my count, they only wear out two pairs each. After the first pairs get ruined, one of the girls places an order for the new ones. These get worn out quickly as well, but they never get more. Their mother finds out about the new shoes and becomes furious. It is at this point that she makes the declaration about marrying one of them to whoever solves the mystery.

My Thoughts:

This is a solid retelling of the tale and an overall enjoyable read. I cared about Lily and Eben, and I thought Doué handled the relationship well. I was rooting for them the whole time. And I always appreciate when there isn’t insta-love. Tharius is also an intriguing villain. He’s manipulative to the point where I wasn’t even sure if he was the villain for a while. And even once I was sure, I still felt bad for him. His actions are deplorable, but I understood his reasons. I love finding a villain with a good, and even sympathetic, motive.

Even though I liked the book, there were several problems that kept my rating from being higher. The first is a problem that plagues most retellings of this story: the characterization of the princesses suffers due to the number of them. The only one I felt I knew was Lily; the rest I couldn’t even really tell apart. I talked about this same issue in my post on Princess of the Midnight Ball and in my (really old) review of Entwined (which you can read here). I remain convinced that the only way to solve this is to cut out some princesses, as Juliet Marillier does in Wildwood Dancing. Not all variants of this tale use twelve girls; there are Hungarian, Russian, and Czech versions that feature three and Danish and Portuguese versions that only have one.

My other big problem is the lack of explanation we get for some characters’ motivations and backstories. The queen’s motivations in particular confused me. We are told early on that the king has allowed Lily to take her time choosing a husband. He is mostly absent during the story, and it seems that as soon as he’s gone the queen starts pushing Lily to make a choice. She nags her about supposedly leading Lord Runson on and sets up private outings with a visiting prince. When Lily isn’t speaking due to the curse, the queen gives her a deadline in order to force her into making a choice. We’re never given a reason for any of this, so she just ends up seeming like a controlling jerk. I was also left with a lot of questions regarding the relationship between Lily and Lord Runson. At some point before the start of the story, the two were good friends. However, some kind of betrayal occurred and caused Lily to hate him. We never get any other information on this backstory, and I really want to know. Since he is a major part of the story, it felt like it should have been explained more.

My Rating: 3 stars

Other Reading Recommendations:

The starred titles are ones I have read myself. The others are ones I want to read and may end up being future Fairy Tale Friday books. To keep the list from getting too long, I’m limiting it to four that I’ve read and four that I haven’t.

Other Retellings of “The Twelve Dancing Princesses”:

Wildwood Dancing by Juliet Marillier*

Princess of the Midnight Ball by Jessica Day George*

Entwined by Heather Dixon*

The Door in the Hedge by Robin McKinley*

The Night Dance by Suzanne Weyn

House of Salt and Sorrows by Erin A. Craig

The Midnight Dancers by Regina Doman

The Girls at the Kingfisher Club by Genevieve Valentine

More Retellings by Lea Doué:

The Midsummer Captives

The Red Dragon Girl

The Moonflower Dance

Snapdragon

Red Orchid

Mirrors and Pearls

About the Fairy Tale:

Twelve Dancing Princesses Tales from Around the World by Heidi Anne Heiner*

Coming in July:

Thank you to everyone who voted in the July poll! “Rapunzel” won, and the retelling of it that I picked just came into the library this evening! The post will hopefully be up by the second week of July. “Bluebeard” and “East of the Sun, West of the Moon” tied for second place, and I’m not quite sure what to do about that. I could try to do both, but I’m not sure if I’ll have time. I have options on the way for both tales. If I can only do one, does anyone have a preference? Comment to let me know!

Have a recommendation for me to read or a suggestion to make Fairy Tale Friday better? Feel free to send me an ask!

#booklr#aliteraryprincess fairy tale friday#the firethorn crown#lea doue#book photography#fairy tale retellings#the twelve dancing princesses#books

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Heidi Ann Heiner's Cinderella Tales From Around The World, I've now read the variants from Germany, Belgium, and France.

*Of course the most famous German Cinderella story is Aschenputtel by the Brothers Grimm. If you don't know it from reading it, you probably know it from Into the Woods, and if you don't know it from there, you've probably heard of it in pop culture. Too many people mistakenly think it's the "original" version of Cinderella. But there are other German Cinderella stories too – all similar to the Grimms' version, but with differences here and there.

*In nearly every German version, and in both of the two Belgian versions the book features, the heroine gets her elegant gowns and shoes from a tree. It throws them down to her, or opens up to reveal them, after she either recites a rhyme underneath it or knocks on it.

**Some variants, like the Grimms', have the archetypal "father goes on a journey and asks for gift requests" plot line, and the heroine gets a hazel twig, which she plants on her mother's grave and which grows into a tree. But in other versions, the tree is seemingly a random one, which either a dove, a dwarf, or a mysterious old man or woman advises her to ask for finery.

**That said, there's one exception: a German version called Aschengrittel, where the heroine meets a dwarf who, like the fairies in some Italian versions, gives her a magic wand to grant her wishes.

*As in the Egyptian, Greek, and Italian versions, it varies whether the German versions have the heroine abused by a stepmother and stepsister(s) or by her own mother and sister(s), whether her father is alive or not, and whether the special event she attends is a royal ball/festival or a church service. In both of the two Belgian versions, the heroine's abusers are her own mother and sister(s).

*While in the Mediterranean versions, the heroine's future husband is always either a prince or (more rarely) a king, in the German versions he's occasionally a knight or a rich merchant instead.

*Other typical German and Belgian details are (a) the (step)mother forcing the heroine to sort lentils, seeds, or grain, usually by picking them out of the ashes, which is usually resolved by birds doing the job for her, (b) the prince (or king, or merchant) having the palace or church steps smeared with pitch so that the heroine loses her shoe, and (c) the notorious detail of the (step)sisters cutting off parts of their feet to make the shoe fit, which is revealed when either birds or a dog call out that there's blood in the shoe.

**One Greek version has the prince catch the heroine's shoe by having the church steps smeared with honey, but the Mediterranean Cinderellas usually lose their shoes either by accident or by choice, while in Germany and Belgium it's usually the prince's doing.

**The foot-cutting episode is clearly typical of German and Belgian versions, but the Grimms' other notorious detail, where the stepsisters' eyes are pecked out by doves at the end, isn't typical. The Grimms themselves added that grisly detail to give the story a more "moral" ending with the stepsisters appropriately punished.

*The Grimms' footnotes for their version are included in this book. They mention several other German variants, including two that continue after the heroine's marriage and have the stepmother and stepsister try to murder her, and one where the stepmother starts out as the heroine's childhood nurse and murders the girl's mother by pushing her out a window, then claims she committed suicide.

*The German, Belgian, and French Cinderellas aren't quite so cunning and unfazed as the Greek and Italian Cinderellas. Now we see more heroines who cry over their hardships, and/or who beg to be allowed to go to the ball/festival or church, and whose magical help is more given to them and less in their own control. One notable French exception to this pattern, though, is Madame d'Aulnoy's cunning and self-reliant Finette Cendron.

*France doesn't seem to have the same pattern of culturally-distinct oral versions of this tale that other countries do. Instead, the French examples in this book are nearly all literary versions, and each one is almost completely different from the others.

**Of course the most wildly famous and important French Cinderella is Charles Perrault's Cendrillon. This is the Cinderella we all know best, with the fairy godmother, the pumpkin coach, the magic only lasting until midnight, and the glass slipper.

**Published in the same year as Perrault's version was Madame d'Aulnoy's Finette Cendron. This is an interesting, much longer variation that starts out as a Hop o'My Thumb/Hansel and Gretel story, where three sisters are abandoned in the woods and nearly eaten by an ogre, only for the clever youngest, Finette, to outwit him, but then turns into a Cinderella story when the older sisters abuse Finette after they make the dead ogre's castle their home, but Finette follows them to a ball in finery she finds in a chest.

**Another French literary variant is The Black Cat, which starts out as a Cinderella tale, but then has the heroine be stranded on an island and give birth to a black cat son (long story), then turns into a Puss in Boots tale as the cat helps his mother. Yet another is The Blue Bull, where the heroine runs away from her stepmother with her only friend, a magical bull, only for the bull to be killed protecting her from lions, and which then becomes a Donkeyskin/All Kinds of Fur-type of story, where she becomes a servant at the prince's palace and gets her ballroom finery from the bull's grave.

*Perrault and d'Aulnoy's versions are the only two Cinderellas so far where the heroine has a fairy godmother. Yes, in some others there are fairies or mysterious old women who help her, but the concept of a fairy godmother seems to have French literary origins.

*These same two versions, Perrault's and d'Aulnoys are also where we first see strong emphasis on the heroine's virtue and kindness, even to her cruel (step)family. While some oral versions do have her forgive them in the end, these literary versions not only have her do that, but have her constantly be gracious and kind to them (Perrault) or save their lives even at great personal sacrifice (d'Aulnoy).

*Now that I've read Finette Cendron, I can see its slight influence on Massanet's opera Cendrillon. In Finette Cendron, instead of Perrault's choice to have the slipper taken from house to house, all the ladies are invited to the palace to try it on, and Finette's fairy godmother sends her a horse to ride there – just like Cinderella's fairy godmother transports her to the slipper-fitting at the palace in the opera. Finette Cendron's Prince Cherí also falls deathly ill with love for the mystery girl, but is cured when he finds her. (A recurring theme in many different variants, which I forgot to mention when I covered the Mediterranean versions.) In the opera, this has its parallel when Prince Charming faints in despair over the seeming failure of the slipper-fitting, and before that when Cinderella herself becomes gravely ill because she thinks she'll never see her prince again.

@adarkrainbow, @ariel-seagull-wings, @themousefromfantasyland

#cinderella#fairy tale#variations#germany#belgium#france#the brothers grimm#charles perrault#madame d'aulnoy#cinderella tales from around the world#heidi ann heiner#tw: violence#tw: murder#tw: suicide mention

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

Actually Neil Philip's book The Illustrated Book of Fairytales has Puss in boots type story. Featuring the fox who tricks evil sorcerer landlord drowning himself so the miller protagonist can have his castle pretending to be a prince so he can marry princess like Perrault's story. Story was possibly from Eastern Europe maybe polish or czech origin i don't quite remember it, because it's bee very, very long time when i read that version.

Yes, there are many versions of this type of story where it's a fox in stead of a cat! Both from Italy and France, but I've also seen Armenia mentioned, maybe that's the one you read?

I didn't mean there was never any magic in the Puss In Boots type stories, only that it's likely that Perrault added the magic ogre in his version while he was drawing on Italian and French variants that didn't have a magic landowner. (In a 1555 publication by Straparola the owner of the castle just happens to be away and dies tragically, leaving the castle unclaimed and the Miller's son and his cat unchallenged when they claim it.)

As a tale type in general it is very widespread too, so while scholars seem to think it's Italian in origin, I imagine it's very hard to tell. I've never looked very deeply into this story myself, but Heidi Anne Heiner has! She has a lot of info on this particular tale and it's variants on her website ^^

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beauty and the Beast by neonpuppy featuring a weave basket ❤ liked on Polyvore

Pink Off the Shoulder Sleeved Princess Wedding Dress with Lace... / Clarisse long sleeve dress / Blue floral dress, $18 / Aviù cropped cardigan, $170 / Capezio black suede shoes / Capezio Dance brown leather shoes / Drop earrings / Highlight kit / Beauty product / Garden Trading weave basket / Romeo and Juliet (Barnes Noble Collectible Editions) / Beauty and the Beast Tales From Around the World: Heidi Anne Heiner:... / Light Blue Hair Bow

0 notes

Text

Book with 150 waterspirit tales

Mermaid and Other Water Spirit Tales From Around the World (Surlalune Fairy Tale) Paperback – June 17, 2011

by Heidi Anne Heiner (Author, Editor)

Appearing under many different guises, mermaids have a long, varied history dating back many centuries. Our modern day perception of mermaids is primarily based upon the mermaids and merrows of northern Europe, especially Scandinavia, Scotland and Ireland, as well as the sirens of ancient Greece.

However, water spirits of some type exist in almost every culture situated near bodies of water, be they oceans, lakes, rivers or even wells and springs.

This collection gathers together examples of the earliest scholarship on mermaids and their folkloric relatives, including several articles about their history from ancient times to the nineteenth century when mermaids captured the public and literary imagination during the folklore renaissance of the 1800s.

In addition to the articles, over 150 tales and ballads about mermaids and other water spirits from around the world are compiled into this one convenient anthology.

The emphasis is on the European mermaid in her many guises, but stories from Africa, Asia, and the Americas are also included. Whether you are a mermaid enthusiast or a student of folklore, this anthology offers a diverse array of tales with a unifying theme that both entertains and educates, all gathered for the first time in one helpful collection.

1 note

·

View note

Note

The original 'The Story of Beauty and the Beast' by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot De Villeneuve, as found in Heidi Anne Heiner's 'Beauty and the Beast: Tales from Around the World.'

Alright, cool. 👍🏽

1 note

·

View note

Text

I'm now reading Heidi Ann Heiner's book Cinderella Tales From Around the World. Hopefully it will make me as knowledgable about those stories as that inescapable old post of mine has probably made people think I am.

The different Cinderella stories are arranged in geographical order. So far I've read all the variants from Egypt, Greece, and Italy, and I'm about to start reading the German versions.

For now, I'll share the most interesting points from the versions I've read so far:

*Not all versions of the tale feature a stepmother and stepsisters. The Egyptian variants don't have any parents in them at all. In the proto-Cinderella story of Rhodopis, the title character is just a Greek slave-turned-courtesan with no family, while the other Egyptian tale, The Magic Jar, just has three sisters living together. Meanwhile, the Greek versions usually give the heroine a loving mother and two cruel biological sisters, with no father. In the Italian versions, there's almost always a father, but it varies whether the wicked women are the heroine's stepmother and stepsisters, or her own mother and sisters, or just two sisters with no mother.

*Greek versions typically have the heroine living with her mother and two older sisters. The sisters murder their mother, then cook and eat her flesh, but the grieving heroine lays her mother's bones to rest in a place of honor. Forty days later, the bones turn into three beautiful dresses and other finery and riches for her.

*Italian versions tend to come in two variants.

***One variant uses the archetypal "heroine's father goes on a journey" scenario, much like the Grimms' Aschenputtel or Beauty and the Beast. When he asks his daughters/stepdaughters for gift requests, the sisters want clothes, but the heroine asks for something unusual (e.g. a bird or a tree sapling), or else she asks him just to greet someone for her (e.g. a fairy, or a far-away relative), and when he does, that person gives him a tiny gift for her. Either way, the gift he brings back is what produces her finery.

***In the other variant, the heroine's stepmother or mother sends her out every day to pasture an animal (a cow, a sheep, or a goat), along with an impossible amount of spinning, weaving, or sewing to do. The animal tells the girl to place her work on its horns, and when she does so, it's magically done. Eventually, the (step)mother finds out and has the animal killed, but the heroine saves either the animal's bones or a golden ball she finds inside its body, and from there she gets her finery.

***That said, a few Italian versions include a fairy godmother-like figure: a kind old woman or a fairy who meets the heroine when she's out in the pasture and gives her a magic wand.

*In Italian versions with a stepmother as the villain, she typically starts out as the heroine's teacher or governess. She treats her kindly then, and urges the girl to convince her father to marry her, which she does. But after the marriage she turns cruel. (Some Italian versions of Snow White also begin this way.)

*Another detail from the Italian versions: in the "father goes on a journey" variants, the heroine warns her father that if he forgets her request, then his ship or his horse won't be able to move either forward or backward. He forgets, and sure enough, his ship or his horse freezes in place until he remembers.

*In the Greek versions, the special event the heroine attends in her magic finery is typically a Sunday church service. Some Italian versions have her go to church too, while others have a royal ball or festival, as does Egypt's The Magic Jar.

*In The Magic Jar, the heroine loses a bracelet instead of a shoe. I wonder if Gioachino Rossini and Jacopo Feretti knew about that version when they replaced the slipper with a bracelet for the sake of "propriety" in the opera La Cenerentola?

*In nearly all these versions, the heroine already has her magic source of finery and knows what it can do before the ball/church. So at no point does she beg to go, or cry because she thinks she can't go. She just lets her (step)family leave, then magically dresses herself.

*In both Greek and Italian versions, there are typically three balls or church services. Each time the heroine leaves, the prince has his servants chase after her. But the cunning heroine throws gold coins or jewels behind her, and the servants scramble to pick them up, letting her escape. Sometimes instead, or when she runs out of riches, she throws sand in their eyes to blind them. In a few versions, she doesn't lose her shoe by accident, but throws it to distract the servants because she has nothing else left to throw.

*Very rarely in any of these versions do the heroine and her prince actively "fall in love." They're not described as dancing together the way they do in the familiar Perrault and Grimm versions. The prince just sees her and falls in love with her beauty, with no mention of whether she ever speaks to him or not.

*In all three of these cultures, some versions continue after the heroine's marriage in the vein of the Grimms' Brother and Sister. The (step)mother and (step)sisters turn the newlywed heroine into a bird, or throw her into a river when she's weak from childbirth, or find some other way to get rid of her. But somehow or other she comes back to her husband in the end.

*The fate of the (step)mother and (step)sisters varies. In some versions, namely the ones where they try to get rid of the heroine after her wedding, they're executed. In some Italian versions that have just one stepsister, the stepmother puts the heroine in a pot or a barrel and plans to fill it with boiling water to kill her, but somehow or other she escapes and the stepsister takes her place, so the stepmother accidentally boils her own daughter to death. But in others, they're just left with their envy, and in still others, the heroine forgives them and shares her wealth with them.

I'll share more about different countries' variants as I read them!

@adarkrainbow, @ariel-seagull-wings, @themousefromfantasyland

#cinderella#fairy tale#variations#egypt#greece#italy#cinderella tales from around the world#heidi ann heiner#tw: murder#tw: cannibalism#tw: violence

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm now reading another of Heidi Ann Heiner's fairy tale collections. Sleeping Beauties: Sleeping Beauty and Snow White Tales from Around the World. Since I enjoyed Cinderella Tales from Around the World so much, I couldn't resist opening another of Heiner's books.

The first part of the book is devoted to the different international versions of Sleeping Beauty, the second part to the different versions of Snow White. This is followed by other tales of "sleeping beauties" that don't fit nearly into either category.

We start with the medieval Sleeping Beauty prototype tales from the 13th and 14th centuries.

*The earliest known prototype of the Sleeping Beauty story is the Norse and Germanic legend of Brynhild (a.k.a. Brunhild, Brunhilda, Brünnhilde, or other variations). This legend first appears in the Poetic Edda, the Prose Edda, and the Volsunga Saga from 13th century Iceland. It also appears in the German Nibelungenlied (although that version doesn't include the enchanted sleep), and its most famous modern adaptation is in Richard Wagner's four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen. The figure of Brynhild also inspired the Marvel superheroine Valkyrie.

**The Sleeping Beauty-like portion of the legend is this. The beautiful and strong-willed Brynhild is one of the valkyries, the warrior maiden servants (and in some versions daughters) of Odin (or Woden, Wotan, etc.) who preside over battlefields and bring the souls of fallen heroes to Valhalla. But Brynhild disobeys Odin by saving (or trying to save) the life of a warrior who was marked for death. (The man's identity, why he was meant to die, why she defends him, and whether she succeeds in saving him or not varies between versions.) As punishment, Odin banishes her to the mortal realm, pricks her with a "sleep thorn," and places her in a castle (or just on a rock) surrounded by a ring of fire, condemning her to sleep until a man brave enough to venture through the flames arrives to wake her and become her husband. (In some versions, she has attendants and servants who all sleep along with her.) Many years later, the fearless hero Sigurd, or Siegfried, succeeds in passing unharmed through the flames and wakes Brynhild by cutting off her valkyrie armor (or in later retellings influenced by Sleeping Beauty, with a kiss). The couple doesn't live happily ever after, however: their further adventures and eventual tragic fates are a story for another day.

**Even though it's a well-known fact that in "the original Sleeping Beauty stories," the prince (or his counterpart) impregnates the sleeping heroine and she wakes after she gives birth, no such thing happens in this earliest proto-version. If we assume that this really is the Western world's first tale of a heroine in an enchanted sleep, then it seems as if that sordid detail was a later addition.

*Next in Heiner's book come several medieval French Sleeping Beauty tales, mostly from Arthurian romances. These are the tales where we first see the motif of the heroine's love interest raping her in her sleep and fathering a child. Since few of them have ever been translated into modern English, the book simply summarizes them instead of printing them in full.

**The best-known of these stories, which most resembles Sleeping Beauty as we know it today, is the tale of Troylus and Zellandine from Le Roman de Perceforest, an Arthurian romance from 14th or 15th century France. In this tale, a knight named Troylus loves a princess named Zellandine. Then learns that while spinning, Zellandine has suddenly fallen into a deep sleep, from which no one can wake her. With the help of a spirit named Zephir and the goddess Venus, Troylus enters the tower where she lies and, at Venus's urging, he takes her virginity. Nine months later, Zellandine gives birth to a son, and when the baby sucks on her finger, she wakes. Zellandine's aunt now arrives, and reveals the whole backstory, which only she knew. When Zellandine was born, the goddesses Lucina, Themis, and Venus came to bless her. As was customary, a meal was set out for the three goddesses, but then the room was left empty so they could enter, dine, and give their blessings unseen; but the aunt hid behind the door and overheard them. Themis received a second-rate dinner knife compared to those of the other two, so she cursed the princess to someday catch a splinter of flax in her finger while spinning, fall into a deep sleep, and never awaken. But Venus altered the curse so that it could be broken and promised to ensure that it would be. When the baby sucked Zellandine's finger, he sucked out the splinter of flax. Eventually, Zellandine and Troylus reunite, marry, and become ancestors of Sir Lancelot.

***This tale provides some answers for questions that the traditional Sleeping Beauty raises. In the familiar tale, the king, the queen, and their court know about the curse, so why do they keep it a secret from the princess? Yes, they avoid upsetting her by doing so, but the end result is that when she finally sees a spindle, she doesn't know to beware of it. Why not warn her? And why is there a random old woman in the castle, spinning with presumably the kingdom's one spindle that wasn't destroyed, and why, despite living in the castle does she not know about the curse? (It's no wonder that most adaptations make her the fairy who cursed the princess in disguise.) Yet in this earlier version, there are no such questions: no one except the eavesdropping aunt knows about the curse, because it was cast in private, so no one can take precautions against it. Another standout details is the fact that Zellandine's sleep doesn't last for many years, and that the man who wakes her already loved her before she fell asleep. Disney didn't create those twists after all!

**The other medieval French Sleeping Beauty tales are Pandragus and Libanor (where Princess Libanor's enchanted sleep only lasts one night, just long enough for Pandragus to impregnate her), Brother of Joy and Sister of Pleasure (where the princess isn't asleep, but dead – yet somehow the prince still impregnates her – and is revived by an herb that a bird carries to her), and Blandin de Cornoalha (a knight who, refreshingly, doesn't impregnate the sleeping maiden Brianda, but breaks her spell by bringing a white hawk to her side).

*All of these early Sleeping Beauty tales are just one part of bigger poetic sagas. Maybe this explains why Sleeping Beauty is fairly light on plot compared to other famous fairy tales (i.e. we're told what's going to happen, and then it does happen, and it all seems inevitable from the start). Of course one argument is that it's a symbolic tale: symbolic of a young girl's coming-of-age, as the princess's childhood ends when she falls asleep and her adulthood begins when she wakes, and/or symbolic of the seasons, with the princess as a Persephone-like figure whose sleep represents winter and whose awakening represents spring. That's all valid. But maybe another reason for the flimsy plot is that the earliest versions of the tale were never meant to stand alone. They were just episodes in much longer and more complex narratives.

@ariel-seagull-wings, @adarkrainbow, @themousefromfantasyland

#sleeping beauty#fairy tale#variations#sleeping beauties: sleeping beauty and snow white tales from around the world#heidi ann heiner#norway#iceland#germany#norse mythology#france#england#italy#tw: rape#tw: cannibalism

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've still been reading Heidi Ann Heiner's Cinderella Tales From Around the World. I've just finished reading all the variants from Ireland, Scotland, and England.

Here are the patterns:

*In Gaelic variants (e.g. two Irish versions and one Scottish), the heroine and her two sisters typically have names that describe their appearance or demeanor, with the sisters' names implying that one is blonde and the other brunette. For example, Fair, Brown, and Trembling, or Fair-Hair, Brown-Hair, and Mangy-Hair, or the Fair Maid, the Swarthy Maid, and the Snow-White Maid.

*As usual, it varies whether the heroine is abused by a stepmother and stepsister(s) or by her own mother (or both parents) and sister(s), or just by her sisters alone, and whether there are two (step)sisters or just one. In the three Gaelic versions with hair-themed naming, the girls are biological sisters, though in The Snow-White Maid, the Fair Maid, the Swarthy Maid, and Bald Pate Their Mother, they're half-sisters and Balt Pate is the Snow-White Maid's stepmother.

*It seems far more common in these versions for the heroine and her (step)sister(s) to be princesses. This has sometimes turned up in other countries' variants so far, most notably in Finette Cendron, but so far the British Isles seem to have the biggest number of Cinderellas who are princesses by birth.

**In the Irish Fair, Brown, and Trembling, not only is Trembling seen by her own prince at church, but the fame of her beauty spreads throughout the world, and all the princes of Ireland come to see her, as do princes from other countries like Spain and Greece. They all want to marry her and agree to duel for her hand after the slipper fits her, but after four days of fighting they all concede to the prince who first fell in love with her.

*The heroine's magical helper is either an old woman or an animal in these variants, and if it's an animal, it's almost always either a black sheep or a red calf. The beginning of one Irish version explains that black ewes were considered good luck.

**In almost all the versions with an animal, as in the Grimms' One-Eye, Two-Eyes, Three-Eyes or French tale of The Blue Bull, the (step)mother sends the heroine out to pasture each day with barely anything to eat, hoping to slowly starve her, but the animal magically provides her with good food.

**As usual, the animal companion tends to be killed by the (step)mother, but unusually, it doesn't stay dead in these variants. Instead, after the heroine gathers up the bones, the animal comes back to life, limping because the heroine lost one shank bone, but otherwise none the worse for wear. There are also some variants where the animal doesn't die at all. In one Scottish version, the heroine is ordered to behead the calf herself, but instead she kills her sister (!), takes the calf and runs away.

*In both Irish and Scottish versions, the special event the heroine attends is always church, not a festival or party. Several versions take place at Christmas and have her attend the special Yuletide Masses.

*The old woman or animal typically not only provides the girl with finery and a horse to ride, but cooks the family's dinner for her by the time she gets back. In one Scottish version, Ashpitel, the black lamb doesn't even give her finery – she just dresses herself in her own fine clothes that she rarely gets to wear, while the magic the lamb provides is just to cook the dinner for her.

*In the Gaelic versions, the prince rides after the heroine the third time she rides away from church, and grabs her by the foot, but only succeeds in pulling off her shoe. Whereas in the Scots versions, she just loses her shoe by accident.

*In Scotland, the story (and the heroine) is most often called Rashin Coatie (a.k.a. Rashie Coat, or Rushen Coatie), because the heroine wears a coat made of rushes, or "rashes" in Scots dialect.

** It varies whether Rashin Coatie is simply forced to serve her (step)mother and (step)sister(s) at home, or whether she runs away, to escape either from a cruel family or from an arranged marriage, and becomes a servant at the prince's castle, a la Donkeyskin.

*Both Irish and Scottish versions tend to include the motif of foot-cutting to make the slipper fit, just like the German versions do. A bird alerts the prince, typically in a rhyme which says that "nipped foot and clipped foot" is riding with him while "pretty foot and bonny foot" is elsewhere. But it's not always the (step)sisters who do it. In the Donkeyskin-like versions of Rashin Coatie, where the heroine runs away and becomes a servant at the prince's castle, the rival who tries to trick the prince is a henwife's daughter instead.

**Henwives are ubiquitous in these variants. But in the Gaelic versions (both Irish and Scottish), the henwife is benevolent, often serving as the heroine's magical helper, while in the Scots-dialect Rashin Coatie variants, she's a secondary villain, with the above-mentioned daughter who aspires to marry the prince.

*The Gaelic versions usually continue the story after the heroine's marriage, and have her eldest sister (the blonde one) throw her into the sea or a lake, then take her place. But either the princess's bed stays afloat so she doesn't drown, or she's captured by a whale or a water monster that keeps her a prisoner in the deep, yet briefly lets her onto the shore now and then. A cowherd sees her and alerts her royal husband, who rescues her, slaying the whale or monster if there is one, and the sister is executed.

*There doesn't seem to be a strong tradition of localized, oral Cinderella stories in England the way there is in Ireland and Scotland. But this book does include an English literary version: The Cinder-Maid by Joseph Jacobs, the folklorist who gave us the best-known versions of Jack and the Beanstalk and The Three Little Pigs.

**As usual in Jacobs' retellings of folktales, he borrows motifs from various different oral versions in an attempt to write down the "definitive" version of the tale. So The Cinder-Maid is basically the Grimms' Aschenputtel, with the three-day royal festival, the heroine getting her finery from a hazel tree on her mother's grave, the prince smearing the palace steps with tar to catch her golden slipper, and the stepsisters cutting off parts of their feet. But Jacobs also includes the motifs of "finery from a nutshell" and "hollow tree opens to reveal gifts" from other versions – each dress and pair of shoes comes from inside a hazelnut from the tree, and then the trunk opens to produce a coach and horses. And the bird in the tree instructs Cinder-Maid to leave by midnight, as in Perrault. (The midnight deadline is a rare motif in international Cindrellas, despite the fame Perrault gave it; in most versions she just leaves early to ensure that she gets home before her family does.)

**In his footnotes to The Cinder-Maid, Jacobs notes the existence of Rhodopis, but he argues that the entire Cinderella story (the persecuted heroine, magical help to attend an event, etc.) most likely originated in Germany, because it was a German betrothal tradition for a man to put a shoe on his fiancée's foot. He makes no mention of Ye Xian, or the more common belief that the story was born in China from the Chinese view of tiny feet as the height of feminine beauty. This reminds me of a hypothesis I once read that maybe Ye Xian isn't really as ancient a tale as it's believed to be – that maybe the story originated in Germany, then spread to China by way of the Silk Road, and that the name "Ye Xian" may derive from the similar-sounding "aschen," the German word for "ashes" that starts every German form of Cinderella's name (Aschenputtel, Aschenbrödel, etc.). Personally, though, I don't see why the reverse can't be true: couldn't the story just as easily have travelled from China to Germany? Maybe the heroine's association with ashes started when Germans heard the name "Ye Xian" and thought it sounded similar to "aschen"!

But I'm getting ahead of myself talking about China. The next several Cinderellas I'll be reading come from Scandinavia.

@adarkrainbow, @ariel-seagull-wings, @themousefromfantasyland

#cinderella#fairy tale#variations#cinderella tales from around the world#heidi ann heiner#ireland#scotland#england#tw: violence

35 notes

·

View notes