#having written and changed my opinions about the characters during the course of a singular fic only happened for tainted Ambitions

Text

fanfic writing is always like:

questionable characterisation (not really familiar yet) => oh this is actually good => questionable characterisation (projecting)

#looking at my m/dzs fics and uh#uhhhhhh#J/C and L/WJ are the biggest victims of this#which is why I make a point to revisit the novel when I can esp for longfics#but sometimes I go back and see ''oh I really wrote this one shot well. Perhaps my writing at the beginning was actually good?'' and get#slapped in the face by four idiots and the City of ghosts#now that I think about it. Writing L/XC consistently as having an overprotective complex over his didi and writing W/WX having a weird#complex over his shidi is making me laugh so much#kk's rambles tag#having written and changed my opinions about the characters during the course of a singular fic only happened for tainted Ambitions#so you have the strange shift from the revenge fantasy drama to something that might actually be compelling if done well#(I want to do it well but I don't want to touch b/nha with a ten foot pole these days. Not because of the fandom but because I don't like#the source material anymore. Controversial opinion but anyways)#my opinions about dg/rp didn't change much during fic writing nor did the characterisation change that much#even if it has the second highest fic count after m/dzs. Hm.#probably because i mostly write for it as a writing exercise#and the one I did start as a proper fic is abandoned because I lost energy#(my personal opinion is that my j/c POV is the most suited to my writing due to my tendency to make similar protagonists in my original#works. It's a little funny because his manner of speech in his internal narrative is plenty similar to both Romila and Rajanya in the#''why in the ever living Fuck'' even if they all have different motives.#or maybe I am too used to writing cranky people with unresolved and unrequited love. Anyways)

1 note

·

View note

Text

aere perrenius

pairing: akaashi keiji x gn!reader

genre: fluff, strangers to lovers, writer!akaashi and librarian!reader

word count: 2.7k words

warnings: disgusting amounts of fluff

summary: more lasting than bronze. a once in a lifetime opportunity turns into a twice in a lifetime chance, and before you realize it, it just turns into a potential lifetime

dedicated: to miss issy ( @cafemiya ) kind beyond words, incredible beyond compare

You’d once thought that life was cruel to you, a single librarian that ended up helping children find picture books and nasty teenagers that had to pay their overdue library fees. You often just moved through the movements, walking to the library every single day, picking up coffees for everyone that worked with you that day, and nothing ever really changed.

Until today.

Today, when you walked into the coffee shop that was only a block away from the library—a small little out of the way place that served the best croissants with chocolate butter you’d ever had before—you were shocked to note that there was another singular figure in the shop with you.

Typically when you went in, it was early enough in the morning that you beat out the high schoolers and people who went to their 9-5 jobs, yet you always managed to miss the people who worked night shifts, so the barista often told you.

Today, however, there was a singular figure sitting at a table, laptop on the table with a small white mug of coffee in his hands, glasses perched precariously on the bridge of his nose as he seemed intent to read whatever it is was on his screen.

His hair was curling over thin golden frames, flowing over his forehead and spilling against his ears as he pressed his lips to the coffee mug, blue eyes focused on the words before him. The morning light had not yet seemed to crest the mountains of skyscrapers that littered the Japanese skyline, so the warm lights of the cafe seemed to soften the edges around him, making him angelic as he just relaxed there.

Perhaps it was the pure shock of seeing him, or even just the lack of sleep you always seemed to suffer from in the mornings following a weekend, but something led to your mistake of forgetting to conceal your admiration of him.

In your trance of adoration, you simply forget the cafe has a bell over the door.

He glances his up when he finishes taking a sip from his drink, offering a smile your way in the way that two people up way too early would share a smile with each other—as if only the two of you knew the secrets that the sunrise would whisper if only you would wake early enough to listen.

“Your usual?”

The barista, a sweet girl named Akira who seemed to be pumped full of espresso for she was way too peppy for this time of the hour, draws your attention away from the man sitting by himself at the window table.

“To go, right?” When you shake your head, she laughs slightly, inputting your usual order into the computer just for her to end up making it only a few seconds later, “What’s with the change today, you always take it straight to the library.”

When she sees you steal a glance at the mysterious stranger, she leans in with a hand cupped around her mouth, devastatingly wicked glint in her eyes as she whispers to you, “He came in a couple of minutes of go, saying he’s new in town. A writer, if you could believe it. Maybe you could warm him up to the area?”

“I have to go to work soon,” you hiss back softly, feeling the warmth take over your cheeks as you resolutely refuse to look back at him in case he heard her gossiping.

“Yet, you’re taking your coffee here?”

She, unfortunately, raises her eyebrows suggestively at you as she slides your drink to you in a small white mug resting on a dish, steaming and hot with a less heated croissant on a separate dish. You make a noise of disbelief as you carefully adjust your bag on your shoulder, taking your breakfast with you to a seat, not too close to the writer and yet not too far away that you are unable to admire him.

Pulling out a book from your bag, you are content to just read and settle in for a few minutes that you would normally spend in the library doing random work until the doors unlocked. It’s a newer novel you’d just picked up from a bookstore, and it was only because the author would be visiting the library soon, so you wanted to get a feel for the writing style, in case there were any questions that the people had for the staff.

“A good read, is it?”

You don’t really register that anyone is talking to you, at first, instead intent on just reading In Regards to Aces before it clicks in your mind two facts; one, that you are indeed holding a book and reading, and two, that you are only one of three people in the establishment, not to mention one of the three was just a barista making herself a coffee.

When it hits you that the stupidly attractive man at the window is indeed talking to you, you shove a bookmark in the spot you were reading as you turn to him, “Ah, yeah, it is, though I don’t have much to say on it considering I just started reading it.”

“Initial thoughts, then?” His smile soothes you a bit, making you relax from the initial tension you’d felt, “I’ve found the author tends to use verbiage that rambles on, but that’s my own opinion on it.”

“Well, from what I have read so far,” you set the book on the table, star embellished cover twinkling in the lights of the cafe, “I like the way that the author describes the character’s feelings—it felt really authentic, and added to the atmosphere for the story.”

“Well, just wait until you read the ending,” he raises an eyebrow at you and a playful look comes across his face for a second before disappearing, “it’s a real gutwrencher, honestly, I’m surprised the author had decided to take it in that direction.”

“Well, hopefully I’ll be able to read a good part of it before the end of the day,” you muse, hand running idly along the edges of the pages, “I’m hoping to be able to talk to the author during the meet and greet later today at the library.”

He makes a thoughtful noise, a small content smile on his face as he sets his mug down on the saucer. There’s a look in his eyes, something that says that he knows something that you don’t, and yet when you go to ask about it, he says instead, “Tell me what you think of it when you finish it, I’d love to hear your thoughts on it.”

You watch as he begins to pack up his things, tucking the laptop away into a sleek black backpack, all while sipping gingerly on your drink, “Of course, perhaps I’ll see you again, I’m usually here before work.”

“I look forward to it.”

He shoots you a smile over his shoulder as he leaves the cafe, throwing away his things and setting aside his dishes before he exits. Watching him walk down the street, you let out a breath you didn’t know you were holding.

“Gosh,” Akira’s voice makes you jump in your seat slightly, “he was really pretty; you think he was a model?”

“I don’t know, but he could be if he wanted to be,” you smile to yourself as you check your phone, swearing as you realize you might be a few minutes late, “I gotta get to work, I’ll see you tomorrow morning!”

Chugging the rest of your drink, of which has cooled significantly, you end up rushing out of the door of the coffee shop, leaving a good tip for Akira before you go.

A meet-cute. Is that what that would’ve been considered?

Walking into the library, you have a dopey smile on your lips, and the meeting from the morning lets you float your way through work as if your feet haven’t touched the ground.

The writer meet and greet wasn’t for another few hours so when you were putting books back on the shelves, and when the flow of people tended to slow down, your nose was tucked gently into the pages of the book you’d picked up.

It was wonderfully written, with words that seemed to suck you in and captivate you, unable to truly pay attention to what you needed to be doing. You were so ecstatic to be meeting the author, to be able to see what sort of person they’d turned out to be.

They had been pretty secretive, declining interviews left and right and no one has been able to figure out who they were. No one really knew if Akaashi Keiji was their real name, or just a pen name either, a ghost writer who wanted to leave their mark on the world without claiming any credit for the impression they’d leave behind.

Truth be told, it was something you admired in them.

There was something special about someone wanting to create something, and yet walking about their daily life knowing that not a single person would recognize them for it. They weren’t doing it for fame, or for money, but because they truly enjoyed writing and creating books for people to enjoy.

“If you keep yourself in that book, you’ll never get these shelves done,” shit, you’d thought you tucked yourself far enough into the autobiography section that your coworker, Kaori, wouldn’t be able to find you, “what book is it this time?”

“In Regards to Aces…”

She raises an eyebrow at you, glancing at the big poster of the book’s cover displayed only a few feet away from the pair of you, “Uh-huh, gonna suck up to the writer? Get you a rich, anonymous sugar daddy?”

“Pft,” you smile at her with a crooked grin, “let’s be inclusive here, we don’t know if they identify as a guy, Kaori.”

She shrugs a shoulder at you as you begin to push the cart filled with returned books into the aisle, making your way to the front of the library, “Actually, Akaashi and I went to high school together. When he got famous, everyone at our school, like, made a silent pact to respect his privacy.”

“You know the Akaashi Keiji?” You give her an incredulous look, feet planting firmly in front of the help desk of the library, “As in, coming to our library, has won multiple National Book Awards in a row for their novels Akaashi Keiji?”

“Yeah,” she picks something off of her shirt with a sour look on her face, “I’m pretty sure Bokuto threatened a guy that said he’d leak Akaashi’s school name, but it might’ve been the whole group of them, honestly.”

“Bokuto…” you look at her with a bewildered look in your eyes, “Bokuto Koutarou, MSBY wing spiker, Bokuto?”

“Yeah,” she smiles brightly at you, which you quickly erase with a hand smacking her firmly in the arm, “Oh my god, what was that for?!”

“For not telling me you were surrounded by future celebrities in high school?!”

“Oh, as if there isn’t one person from your school that got famous,” Kaori levels a glare at you as she rubs her arm.

The pair of you are sitting at the reception area now at the front of the library, watching people flow into the seating area set up for the meet and greet. A copy of the book’s cover is set up next to the author’s seat, which is on a small raised platform behind a small red barrier.

“I’m pretty sure a kid in the grade above me moved to Argentina?” She laughs at your answer, a hand over her mouth as someone steps up to the desk, taking both of your attention away from the conversation, “Hey, how can we help yo— oh! Hi, again, how are you?”

Standing before you, straps of his backpack slipping off of his shoulders and glasses sliding down the bridge of his nose. There’s a little bit of a smile on his lips as he sighs, “Oh. Hello, I’m good. I rushed here because I was worried about being late—Kaori?”

“Akaashi,” she smiles at him, hand reaching out to shake his hand easily as you stare at the both of them flabbergasted, “Didn’t you get my text earlier about you coming to the library?”

“No, I was busy with the moving vans,” he turns his gaze on you and you swear your mouth dries up a little bit, “After I got a cup of coffee, I was arguing with the movers about a van of stuff that got lost. Turns out they were on the wrong side of town.”

“You mean to tell me,” you interrupt, hand coming up to stop Kaori from speaking, eyes trained on the wavy-haired man in front of you, “that you asked for my opinion on your book? Your own book?”

He gives a cheeky grin, teeth showing as he raises an eyebrow, “It’s easier to hear honest opinions if people don’t know I’m the author.”

You roll your eyes at him before he turns back to Kaori for a quick second, “Kaori, would you mind getting me some water, oh and maybe even a snack?”

She nods easily, hair swishing lightly as she pats you on the back and leaves, “‘Course, meet you up on the stage, bigshot.”

When she leaves, there’s a bit of an awkward silence, something like you don’t know what to say, and yet you know if you were to say anything, something might change. It’s only a feeling, but you suddenly want to spend as much time with this man as possible.

Now in the late afternoon light, you study him in a way you didn’t get to before. The warm sunlight that filters in through the windows makes his hair seem a bit light, but still just as unruly as it was this morning. His eyes are inquisitive, sharp in a way that observes and analyzes all within a moment’s notice.

There are patches of red and blue light dancing along his shoulders, refractions from the sun through the stained glass windows. His shirt is a little wrinkled but otherwise neat, one of the sides untucked as his loose tie hangs from around his neck.

He’s even prettier in the daylight, you decide.

“I’m sorry lied to you this morning,” his voice drops a little bit, inflection careful as he looks at you, “I promise I won’t lie to you anymore, if that means anything.”

“Well, if I catch wind of you lying,” you start, sidestepping the swinging door of the counter to start walking towards the stage area, “I’ll make your life a living nightmare, I know where you get your coffee, sir.”

“Oh, not the coffee,” He holds his hands up in surrender, “I loved their dark roast, where else in the town am I supposed to get it?”

“That, mister, sounds like a you problem,” you want to see him smile more, is the first thing you think when he laughs, “but only if you get on my bad side.”

“Do you think going out for dinner sometime might put me on your good side?”

There are moments in life that can shatter and alter the way that you think and perceive things for the future. For instance, that one time a teacher had given you a recommendation on a book had jumpstarted your love of reading which had turned into a job with lovely friends. If not for that one teacher, who knew where you would be now, because life is funny and doesn’t work out the way you think it will when things aren’t set exactly in motion.

This is one of those moments, and you know it is, because as he asks you out on, assumably, on a date, you envision a life for yourself.

A life filled with moments and snapshots with Akaashi Keiji at your side. He kisses your cheek one morning as you both make coffee for each other, his hand is warm on the small of your back as he leads you through the grocery store, and his voice is loving as he whispers to you at night before you fall asleep.

Now, you’ve always been somewhat a romantic, but you think this is the first time you’ve ever envisioned a life like this upon a second meeting. As Akaashi waits for your response, face neutral but content, you smile to yourself.

“Yeah,” you respond, leaning close to bump your shoulder against his gently, “I think getting dinner might boost your standings with me.”

#akaashi keiji fanfiction#akaashi keiji x reader#akaashi keiji x you#akaashi x you#akaashi x reader#akaashi keiji#hq!! akaashi#hq!! fluff#haikyuu!! akaashi#haikyuu!! fluff#grind for the wealth

160 notes

·

View notes

Note

what do you think the biggest problems in the sns fandom are?

Okay the usual disclaimer, my opinion, don’t read if you can’t take healthy criticism. I have mentioned some problems in my separate posts already but I'll try to summarize;

Many people treat Naruto like a girl and Sasuke as his "man". It's all the terrible and boring straight girl fantasies without any connection to Naruto and Sasuke's actual characters or their relationship. Funnily enough, also liking the same awful tropes SS shippers like, except replacing Saku with Naruto.

Prioritising Naruto in the relationship. The relationship is mostly about Naruto being pleased and loved. It's not even enough Sasuke is Naruto's servant and entertainer, Naruto has to have multiple other boyfriends who also please and worship him. The relationship is just about Naruto being "sunshine princess" and Sasuke... well he's the sentient dick whose other relationships are forgotten. I also mentioned this tends to happen in most fandoms, because people project and they want the character they project onto to be the one who is more loved.

Basing their entire personalities/relationship/dynamic on singular out of context panels and also ignoring the fact they change a lot during the course of the manga.

Not bothering to look into the negative aspects of the relationship, acting like it's all sunshine and roses. Not understanding neither of them is perfect, and Naruto can't heal Sasuke with his dick/butthole.

Trying to prove points by using badly written filler or even worse, those horrible novels. I'm protective of Sasuke and all of these writers crap on him constantly, and to see it being praised by his supposed "fans" is upsetting.

Just people shipping themselves with their idealized version of Sasuke instead of shipping Naruto and Sasuke.

I probably forgot something but this will do for now.

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goop Plays Kill la Kill the Game: IF (Ryuko Episodes 5-8)

It’s been a while.

Episode 5

Writing about these episodes has been a struggle. I wouldn’t be able to narrow down a single reason for my eight-month hiatus from IF’s story mode, but I can say that it’s difficult to talk about content that is overwhelmingly—and disappointingly—a rehash of scenes I’d already watched before.

Ryuko’s fifth episode especially feels like a game of “spot the difference.” Segments of Satsuki’s story are repeated with astonishingly minor changes, and while this has been an issue with earlier Ryuko episodes (1 and 3), by episode 5, it’s starting to feel very tedious.

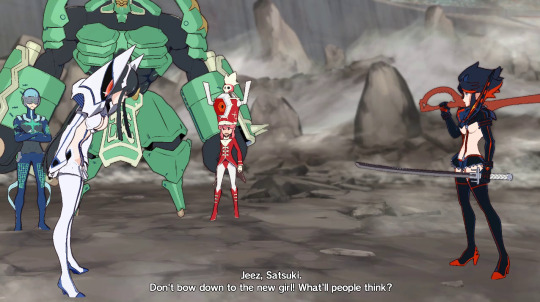

I won’t deny that the slight alterations are charming—they very much are! Mako’s contribution to Ryuko and Senketsu’s fight against Nui, for example, is adorable:

Mako: My dad says, “When you’re outnumbered, get more weapons!” An eye for an eye, a blade for a blade!

However, such minimal additions feel like a dishearteningly poor use of the player’s time. If I hadn’t already questioned it before, these chapters really made me question the choice of a two-campaign story mode.

It’s not that I don’t see the appeal of such a structure; there’s something fun in telling one side of a story and then changing the perception of that story by telling another side of it. Plus, with IF in particular, I think there was a goal—at least to some extent—of confounding players with Satsuki’s ending. I could see Ryuko’s campaign as a means of making the plot more interactive, which is of course fitting for a video game. By not spelling everything out right away, players are encouraged to unravel the mystery and put the pieces together.

Satsuki: I had a bad dream....

But... there’s just too much overlap for me to feel that the two-campaign structure was the most effective storytelling decision. The choice perhaps makes more sense from a gaming standpoint; it’s easier to focus on one playable character rather than jump around between two. But I don’t know—perhaps it could have been fun to give players a feel for more of this game’s roster all at once. Maybe we could have played as the Elite Four or Ragyo or Nui, too.

Because from a story standpoint? One major letdown of Ryuko’s fifth episode is that actually fighting Nui completely lacks the power that the cutscene in Satsuki’s campaign has.

Sure, that scene certainly doesn’t have the impact of similar moments in the anime (episodes 18 and 21/22), but you can’t really expect it to, and it works well within the context of IF. Ryuko and Senketsu haven’t been through as much together, but Ryuko still keeps her temper under control to prevent a repeat of hurting Senketsu from it again, they burst into battle with “Before my body is dry” playing, and though the animations in the game can be stiff and limited, it’s still sweet.

Ryuko: Won’t know ‘til I try! So let’s do this!

They sparkle! Their hearts are as one! They’re uniting to take down this threat.

But in Ryuko’s story? You just fight the fight. You miss out on Ryuko shit-talking Nui, you miss out on the song (seriously, was it just the struggling Steam port, or does “Before my body is dry” really not play during the fight?), and most importantly, the emotion I get from the cutscene is largely lost.

Don’t get me wrong—skipping a repetitive scene is appreciated. But at the same time, the omission makes me long for a single story mode. Players could have fought Nui with “Before my body is dry” playing and watched the Satsuki-story cutscene upon victory. That bit of “Satsuki’s” story already focuses so much on Ryuko that in some ways, it honestly feels more “Ryuko” than Ryuko’s story! Why not just have a unified story mode?

Ryuko’s episodes shine when they significantly differ from what players already witnessed in Satsuki’s campaign. The very beginning of episode 5 is charming because seeing Ryuko just wanting to smash things is legitimately amusing.

Ryuko: Oh! So, I just gotta smack ‘em all in the head.

But this could have easily fit into a single story that switched perspectives. And in fact, moving into episode 6...

Episode 6

It’s almost humorous that Satsuki’s story has purposeful omissions to “justify” the existence of Ryuko’s campaign. I am astounded at how Mako literally does not exist in the Satsuki equivalent of Ryuko’s sixth episode:

Seriously, what? This reminds me of Kingdom Hearts jokes about how it’s rude of Disney movies to totally edit out Sora, Donald, and Goofy.

But jokes aside, the Kingdom Hearts comparison actually has some real weight in regards to IF. In Kingdom Hearts, the Disney worlds are—at least, in my opinion—the most fun and engaging when they do more than simply rehash the films they’re based on with Sora, Donald, and Goofy added. In the same way, Ryuko’s campaign in IF is the most fun and engaging when it does more than simply rehash Satsuki’s campaign with Mako added.

And why was Mako even literally edited out of Satsuki’s cutscenes in the first place? It’s really a bigger discussion, but this choice only adds to my frustrations with how Kill la Kill handles Mako’s character. I’ve already written about my beef with the anime in that regard, but IF is even worse. Mako’s so inconsequential to the story (at least thus far) that she can be totally cut out and have absolutely nothing change. For goodness’ sake, she sleeps for a good chunk of her screentime!

Which... is actually an issue I have with the Grand Summoners crossover game, too....

Ryuko: She’s [Mako’s] already asleep!

But in any case, Mako’s presence in the IF story seems to be purely because she’s a popular character. It’s disappointing to me that Kazuki Nakashima couldn’t find more things for her to do.

And it’s sad that she’s literally edited out of Satsuki’s scenes. I really cannot get over that. What the what.

More to the actual content of Ryuko’s sixth episode, the first part is just old hash browns (plus Mako), but the second part is much more intriguing. I find it curious that Senketsu knows right away what the Primordial Life Fiber is, but Ryuko doesn’t. Does he have a connection with it that Ryuko lacks because her Life Fibers haven’t been awoken yet?

Senketsu: That... is what’s known as the Primordial Life Fiber.

Also, same, Mako, same. I also call Nui and Ragyo’s Primordial Life Fiber-y attacks in this game “meatballs.”

Mako: Ooooh! It looks like a big ol’ meatball!

I feel like my previous write-ups on IF already express a lot of what I could say regarding this episode, but I will again reiterate that the character interactions are charming. It’s nice to hear Ryuko laugh (even if in a taunting way), and the Elite Four are absolutely adorable.

Ryuko: Ha! Whatever. I’d like to see you try!

Houka: Oh, my God. Do they have to be so loud? Our enemies can hear us from a mile away.

And since this is a video game and all, in regards to the one fight in episode 6, it’s a bit of a pain; battling multiple enemies doesn’t make for the most enjoyable experience because of the camera and inability to properly lock on to targets. But IF excels in the little details. The dialogue when other characters join you for the fight is as amusing as always.

There really should be subtitles, though. It’s super poor accessibility.

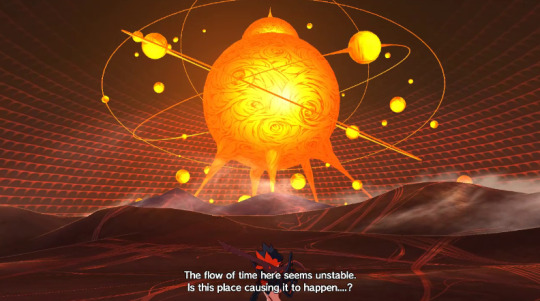

Episode 6 also briefly questions the nature of the world. Earlier episodes of Ryuko’s campaign had Senketsu—and Nui—note that something felt off about time. Here, Senketsu outright says that time in the Fiber Palace is “seems unstable,” and interestingly, the camera focuses on Ryuko when he wonders if it’s the location or “something else” that’s causing the abnormality.

Senketsu: The flow of time here seems unstable. Is this place causing it to happen...? Or... is something else triggering it....

It’s not in this episode, but given that Ragyo later describes Ryuko as “the singularity,” perhaps she is the one messing up the world.

I think Ryuko sums up my thoughts, though.

Ryuko: I don’t get what’s goin’ on.

Of course, probably the most notable aspect of episode 6 is the ending, and while I could see right through what was happening, I have to admit that Ryuko going at Mako with the Scissor Blades is a stellar finish.

Ryuko: I still gotta get revenge for my dad.

Senketsu: What are you doing, Ryuko?!

Episode 7

However...

Ryuko: Oh, blow it out yer ass... Nui Harime!

I got some issues with this.

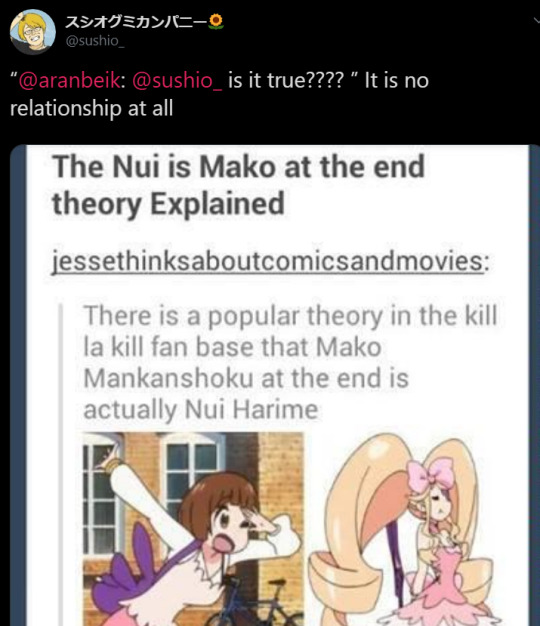

For those who have been Kill la Kill-ing for as long as I have, you might remember that there was a flood of Mako-is-Nui theories immediately after the show’s finale. Amusingly, character designer Sushio outright denied the idea in a Tweet, and a Studio Trigger panel at Anime Expo 2014 (6th post from the top) also shot the notion down.

aranbeik: is it [the Mako-is-Nui theory] true????

Sushio: It is no relationship at all

But fake Makos actually ain’t absent from Kill la Kill. In the official Drama CDs that came packaged with Japanese releases of the anime, there are two instances of fake Makos. The first happens in CD 1, where Maiko Ogure impersonates Mako for a huge portion of the runtime. The second happens in CD 4, where—“funnily” enough—Nui herself impersonates Mako after Ryuko has her heart brutally ripped out of her chest by her own mother.

And here’s my issue with IF’s portrayal: in both of these Drama CD cases, Ryuko is fooled. Mako isn’t Mako for tons of the first CD, and Ryuko doesn’t notice. And, in the Nui situation, it’s Senketsu who has to tell her that the “Mako” before them is not actually Mako. Which goes completely counter to what IF does!

It’s not that I’m against Ryuko recognizing a fraud, but her inability to in the Drama CDs lends insight into her character that I find fitting. Ryuko fails to identify the fake Makos in the CDs because Ryuko initially closes her heart off to the girl—something she outright admits in episode 22 (and which the English dub makes particularly prominent).

Ryuko: Yeah, you [Mako] too! You’re like the most persistent chick I ever met! You didn’t care if I pushed you away! You kept coming back and coming back like a yo-yo!

However, after ripping Junketsu from her body, Ryuko becomes far more open, and it’d be really powerful for her to correctly identify a fake Mako then. It’d show how their relationship has grown and become stronger.

In IF, Mako and Ryuko have hardly had the development they undergo in the anime, and further, Ryuko’s explanation for how she knew it was Nui doesn’t make a lick of sense!

Nui-Mako: How’d you know it was me?

Ryuko: Easy! After Mako wakes up, she’s always got drool on her face.

As Ryuko seemed to have already deduced that “Mako” was Nui before even looking at her, how in the world does this work?

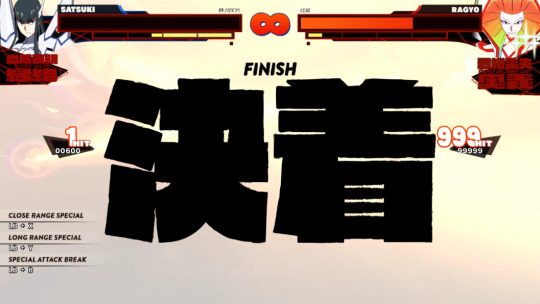

Episode 7 has more questionable character writing for Ryuko later on, too. I’ve already written at great lengths about how I find her attitude regarding murder totally OOC, but Nui’s death scene also has such a strange line regarding Ryuko’s feelings towards Satsuki:

Nui: Guess who ordered me to take the Rending Scissors from your daddy! Give up? It was Satsuki!

Ryuko: If she did, she musta had a good reason for it.

As sweet as the sentiment is, and as much as I understand that it’s there to point out how not even Nui can tear apart Ryuko and Satsuki’s bond, it leaves me totally baffled. Satsuki must have had a good reason to issue the order that killed her father, and Ryuko’s chill with that? At this point in the story, the kind of unwavering faith in Satsuki that Ryuko displays here is completely unearned. I could see Ryuko at the end of the anime feeling this way, but IF Ryuko? Not at all! She barely knows Satsuki!

But for all my gripes regarding the storyline, we Kill la Kill fans are starving. (Well, at least I am, anyway.) Even if Ryuko’s words to Nui make no sense, it is something I would have liked the anime to explore more, and the character interactions here are undeniably sweet. I love Ryuko and Senketsu’s banter and how it shows how comfortable and in tune with each other they are. I love Ryuko’s silly dialogue to Satsuki and how Satsuki smiles at it, telling us that even the “ice-cold” Student Council President can’t help but get a bit soft at this dorky shounen protagonist.

Ryuko: I hate family drama. But I said I’d save Satsuki, sooo...

Senketsu: I had a feeling you’d say that.

Ryuko: Looks like you’re having a really shitty day, Satsuki!

The battle that finishes up this episode, with “Blumenkranz” playing in the background and the Elite Four and Satsuki joining the fight with cute dialogue, is a joy, too. There are a lot of little details that I really appreciate.

(I also realized this time around that you can stop Ragyo’s Instant Kill and didn’t get obliterated by Shinra-Kouketsu like I did in Satsuki’s story.)

Ragyo: Your sins shall be purged along with your pathetic body!

Episode 8

But in regards to the plot of IF, Ryuko’s eighth episode finally starts dropping some more answers. As the ending of Satsuki’s story had implied, the world is outright said here to be her dream, created from Junketsu:

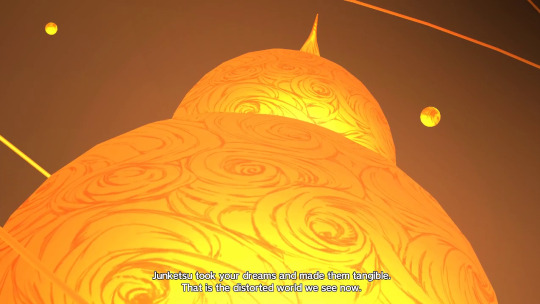

Ragyo: Junketsu took your [Satsuki’s] dreams and made them tangible. That is the distorted world we see now.

However, I still can’t say I get it. When Satsuki wakes up at the end of her story, it’s the start of episode 1 of the anime. She hasn’t come into contact with Junketsu yet, so how has this distorted world even been created in the first place? I guess Life Fibers can just mess with time?

I’m also kinda amused that the world is said to be what Satsuki wants to happen, yet she describes it as a “bad dream” when she wakes up.

But the big “new” information is Ragyo’s assertion that Ryuko is “the singularity”:

Ragyo: I knew it. You were the singularity, Ryuko Matoi.

As Ragyo explains, she could have taken over this fake world (and perhaps merged it with the real one, judging by her comment in Satsuki’s story about how such a world “can even be spun into a single yarn with the Primordial Life Fiber”), but Ryuko got in the way:

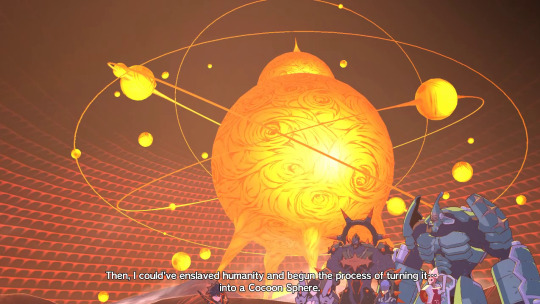

Ragyo: Since my Life Fibers are much more powerful than Junketsu’s, I could’ve taken this planet over. Then, I could’ve enslaved humanity and begun the process of turning it... into a Cocoon Sphere. Yes, I could’ve. If it wasn’t for your existence, Ryuko Matoi.

Now, there have been hints that something’s up with Ryuko all throughout IF, but I can’t say I really know what to make of it. Senketsu remarks that Ryuko’s oddly strong in the first episode of her campaign, Ragyo adds to this and suggests that Ryuko’s affecting the Primordial Life Fiber in the same episode, and then, there also seems to be the implication that Ryuko is triggering the weird sense of time in her sixth episode. The final episode of Satsuki’s story seems to feature Ryuko absorbing Life Fibers, too.

It makes sense for Ryuko to affect Satsuki’s dream world, of course; Ryuko has Life Fibers in her, and she’s also the sister whom Satsuki is ultimately fighting for. I’ve seen theories that the Primordial Life Fiber takes on the shape of a baby to represent the baby sister Satsuki thought she’d lost (and at least in the English dub, Ryuko does refer to the baby as a “she,” further connecting the baby to the lost sister); so perhaps, even if Satsuki doesn’t recognize her connection to Ryuko, maybe the Life Fibers do. Ryuko has power in the dream world because, in a lot of ways, Ryuko is Satsuki’s dream. Maybe that’s the reason that Satsuki only gets flashes of scenes between her and Ryuko in the anime when the baby connects with her, too.

Who knows? I can only hope that episodes 9 and 10 will clear this story up.

I’ve obviously got a lot of questions, but I know this is basically the end. I’m not sure how much explanation to expect going forward, and I’m still wondering about things that don’t even necessarily (?) have to do with the dream world, too. Like, whatever was the point of that moment with Ragyo and one of Senketsu’s scraps? And what was bothering Shiro?

Shiro: There’s just one thing that bothers me...

I said in the beginning of this tl;dr report that I couldn’t pinpoint a single reason for my inability to write it for eight months. But maybe part of the reason is that it’s kind of nice to not know the ending. As long as I don’t play it, there’s still some official Kill la Kill content that I haven’t experienced yet, and it could be anything.

But at the same time, I don’t know how much longer I can go without seeing Senketsu-Kisaragi, so.

The thing—i.e., this monstrous essay—that was holding me back from playing through to the end is now complete! And I’m ready to finally finish this game.

Here’s to hoping that the finale is satisfying 🤞

#kill la kill#kill la kill the game#klk spoilers#klk: if spoilers#goop plays klk: if#ramblings#shut up goop#gifs i made#confetti emoji wow i finally did it lol

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critical Role and Queer Perspective

There’s a little Critical Role analysis I’ve been thinking about that probably won’t fit in my thesis, mostly because it’s too narrow in scope. I wanted to talk about it, though, because it’s been one of the most interesting transitions to watch in terms of how the show thinks about its queer characters.

I have no idea where I read the comment, because it was a very long time ago, but I also remember it vividly. A Critter explained that Gilmore’s scenes made them uncomfortable, because Gilmore fell into the trope that “Queer People Are Funny”. That’s the very 90s-sitcom-esque tradition of writing jokes where the punchline is that the character is A Gay. It’s a problem because it makes people not take queerness seriously - being gay is literally a joke. The first time I saw this comment was when the Whitestone Arc was first airing, but I’ve seen it repeated here and there throughout the run.

I don’t think that argument holds true anymore. Critical Role might not be perfect, but its attitude toward queer representation is not only above average, but also constantly improving. The show started with its singular gay character, Gilmore, who first showed up in Episode 14, and by the end of the series we have a non-binary emperor, two queer happily-ever-afters (Larry and Tary, and Kima and Allura), and multiple characters confirming queer sexualities. More importantly, these characters aren’t just token sexual minorities - they’re quite varied and interesting, and have stories that don’t revolve around their queerness, but don’t ignore their queerness either. The cast does make mistakes with these characters sometimes, but they are very eager to correct them when they do.

I think a really good point of contrast is when Scanlan drinks the love potion and falls briefly in love with Percy near the end of the campaign. That entire scene is utterly hilarious, but it’s no longer made hilarious by relying on the Queer People are Funny trope. It’s hilarious because Scanlan is over the top in his declarations (”your eyebrows...I want to lick them”), because Percy is constantly miffed that Vox Machina is shocked that someone finds him attractive, and because Vex is trying to manage the whole thing and failing not to threaten Scanlan’s life.

This is obviously a matter of opinion, but while the argument that Critical Role uses the Queer People Are Funny trope doesn’t hold true now, back when Episode 14 first aired it sort of was true. For future context, if you didn’t know, I’m queer myself and this episode didn’t bother me at all at the time. Still, I could certainly see how it would put other people off, and it does make me a little uncomfortable in hindsight.

In Episode 14 there are two big moments where the show wrings a joke out of people being queer. The first one is Gilmore’s introduction. The party prepares Vax to flirt with Gilmore for discounts, and they erupt into giggles when Gilmore comes swishing in, and any time Vax initiates flirtation or contact there’s more laughter. I think it’s important to compare this scenes with Vax’s first love scenes with Keyleth in Whitestone - which were notoriously awkward - because it becomes pretty clear after doing that that Vax flirting with Gilmore was A Joke. I don’t think it was meant to be mean-spirited - the players loved Gilmore and the fans did too, pretty much instantly - but there was something giggle-inducing about Matt and Liam trying to out-flirt each other.

The far more uncomfortable moment in Episode 14 is when Kima and Allura reunite. Matt describes them hugging and talking, and Orion - whose character Tiberius has a crush on Allura - starts grumbling that it’s “the story of his life”, implying that Kima and Allura are either together or interested in each other. This one is less “queer people are funny” and more “Orion gets weirdly pissed at his dungeon master for implying a women is attracted to another woman instead of him.” Matt’s initial reaction was to claim the two were ‘just good friends’. Orion’s reaction felt bizarrely possessive and objectifying - like he was upset that the character he’d ‘called dibs’ on, Allura, had the gall to flirt with someone else in front of him. Matt’s denial doesn’t strike me as a bad thing - he was more defending himself from Orion saying “Seriously, Matthew?” - but regardless, he eventually changed his mind on what kind of ‘good friends’ they were.

So we’ve got two early scenes that fall loosely into poor representations of queer characters - one turning gay men into jokes, and one objectifying queer women. In my mind these are more bruises than deep cuts, mistakes that make some people uncomfortable and that are worth pointing out, but that don’t condemn the creators or the show as hateful. It’s worth pointing out that the show does have queer players on it (at least one, possibly more), who didn’t find the scenes disturbing either. The most interesting thing about these moments, though, is how they triggered plotlines that continued throughout Critical Role - plotlines that actually transformed the show’s representation in a really neat way.

Let’s back up a moment. CritRoleStats has previously pointed out that Critical Role now comprises more content than The Simpsons. We’ve spent a lot of time with Vox Machina and their allies; as much time as The Simpsons has spent as an icon of popular culture. In fact, it’s pretty much only sitcoms that can rival Critical Role in terms of sheer runtime and content, but their formulas for churning out this content are very different. Sitcoms are purposefully written so that each episode starts with the status quo being disrupted and ends with the status quo being somewhat restored by the end, with a few lessons learned along the way. Think about i:; nearly forty years later, none of the Simpsons have aged a day. Other long-running shows (like Law and Order or Star Trek) can wring years and years of programming out of single-episode stories, each one forming their own unique adventure. Sometimes the characters grow between seasons a little, and some are killed off or leave the show, but the characters largely remain consistent so their adventures can continue in perpetuity.

Dungeons and Dragons campaigns, by their very design, have to progress. Characters gain experience, learn more about the world, explore it, make new friends, and develop relationships. Change is anathema to sitcoms, but integral to tabletop gameplay.

And alongside the players’ concerted efforts to get better at queer representation, I think this sense of progression was what changed how Critical Role thought about queer characters. The other key factor was that the players are both the writers and actors for their PCs. They know their motivations intimately, and they write their lines on the spot from what they feel like their character would do. And there is only so long that you can inhabit a character before you have to stop taking them as a joke.

I think the moment that drives this home hardest for me is still Vax ‘breaking up’ with Gilmore in Episode 38. He takes Gilmore aside in a tavern, says he’s enjoyed the flirting and that he’s ‘been curious’, but he can’t take it further because he’s in love with someone else. Gilmore is hurt, but gracious, and leaves the tavern. A brief pall hangs over the group after that, until the game moves on and the pain fades a little. Gilmore remained funny, and charming, and bombastic, and flashy, and lovable, but that was a moment he utterly stopped being a joke. His infatuation with Vax, or his love, or whatever you want to call it, was not funny anymore. It was heartbreaking in the way that only love can be, queer or otherwise. As painful as the scene was, it was a huge step in everyone’s ability to understand how to play queer characters. Vax was devastated that he had to break Gilmore’s heart, and Liam still identifies Vax’s biggest regret as “causing Gilmore any pain.” Moreover, Liam was more open and enthusiastic about Vax’s bisexuality as the campaign went on after that scene.

And after that scene, Gilmore disappears in the dragon attack. The group rescues him, and Matt reveals that he nearly died trying to save Uriel’s children. In the Chroma Conclave arc we learn he crafts his own spells, seen when he kills the assassin during the Rakshasa attack and when he helps create the Whitestone barrier. The party meets his parents in Ank’Harel, and learns he changed his name to help his business succeed. We learn during the fight with Thordak that he’s a runechild sorcerer, one of Matt’s homebrew classes. It was like something had snapped, and Gilmore suddenly unfolded into three full dimensions of characterization. Of course, the storyline had gotten more dark in general, but some characters - think Viktor or the mapmaker - remained jokes, no matter how dire their situations were. Not so with Gilmore. The events of the campaign, and the party’s investment in Gilmore’s well-being and their constant instinct to seek his advice or his help, allowed Matt to play him more and to get to know him better. We saw how he reacted to tragedy and pressure and the destruction of his livelihood. He became perhaps the most beloved and fleshed-out of all Matt’s NPCs, to the point where he - along with Cass and Kaylie - was Vecna’s chosen sacrifice to hurt Vox Machina the most.

Coincidentally, Kima went through the exact inverse of this development. In the Underdark, she rebuffed Grog and Scanlan’s advances (both of them hit on her quite a bit) and seemed much happier to be reunited with Allura. The joke that Kima and Allura were a thing began to seem, over time, like much less of a joke. Fans (bless Charlotte Sandmael, for one) helped persuade Matt into getting on that ship. At the same time, though, Matt wouldn’t have gotten them together for kicks or just to please shippers. Instead, he let Kima and Allura develop through the story of the Conclave’s return. The dragons from their past brought them back together again. We saw snippets of their guilt and panic and mutual support, and even of their relationship in less hectic times (”you didn’t have to wear the dress, Kima, it was just a suggestion-”). The storyline would likely have fleshed out Kima regardless, due to her history with the Conclave, but in getting to know both Kima and Allura better, I think Matt eventually saw what the fans were seeing, and he realized that the pair of them falling in love wasn’t really a joke after all.

So, Gilmore started as a beloved if somewhat stereotypical queer cameo, and he evolved into a well-rounded and absolutely adored queer character; and two characters that likely would have been well-rounded regardless naturally developed a queer relationship out of their storylines. I think that happened because Matt is, by all evidence, an extremely empathetic person, and as a dungeon master he strives to understand all the characters he creates inside and out. Look at how well he understands Sylas and Delilah’s relationship: they’re sympathetic and understandable, despite the fact that they’re also despicable. He gets deep, deep inside their heads. And when you get that deep inside the head of someone who is openly queer, you learn to write and play them in a wonderfully rich way; and when you get that deep inside the head of someone whose orientation you don’t know, you might find out that queerness is a part of their personality.

Which brings me, finally, to Tary. I think Tary is just about the pinnacle of this development arc across the story. Up until Tary, the only player character who had a really in-depth queer storyline to explore was Vax, which almost accidentally emerged from him treating Gilmore as a flirtatious comedic bit and then realizing, through roleplay, how strong and conflicted his feelings were. Interesting in its own right, but also more or less concluded as a storyline by Episode 57. By the time Tary shows up in Episode 85, though, Kima and Allura are together, Gilmore’s super well-explored as a character, and the non-binary J’mon has been introduced. Most of the other characters were sort of locked into female-male relationships at this point (or into Epic Single-ness, in the case of Grog Strongjaw), and regardless of their identities (bisexual Vex and Panlan Scanlan) they didn’t get as much time to explore the stories of their orientation as Vax did. So when Scanlan left and Sam had an opportunity to explore a new character, he ended up with Taryon Darrington, who was later established as gay.

The most excellent thing about Tary, besides literally everything else about Tary, is that I still don’t know if Sam knew he was gay from the beginning or if he figured it out along the way. I can’t remember what Sam has said about this, and in a way it almost doesn’t matter. Tary only had about fifteen episodes to explore who he was, and in that time he had a really compelling and honest series of fears and revelations about his sexuality. To me, Tary is pretty much the pinnacle of all the hard work Critical Role has done to try and understand and play queer characters more sensitively. As a character, Tary is far more than his queerness, but he also has chances to explore that queerness in a very real way - and he even gets a happy ending!

And yeah, some things about Tary were a joke - even some things about Gilmore and Kima and Allura are still jokes - but the other thing about love is that, along with being heartbreaking, it can be pretty hilarious. Kima gets grumpy about how perfect Allura’s hair is in the morning. Tary morosely dubs his lost love affair “Larry and Tary”. Gilmore teleports into a hallway where Vax is (for some reason) naked, and cheerfully asks if it’s his birthday.

I think the reason I’ve been so proud to watch all this development is that it doesn’t just explode that Queer People Are Funny joke from the inside, it actually fixes one of the most difficult things about it. Because queer people want representation that doesn’t make a joke out of their identities, it can sometimes be hard to write funny or happy stories about being queer, and that’s part of why we end up with endless numbers of queer tragedies. And that sucks, because queer characters seriously lack for happy endings. They don’t even get to have fun, in some universes.

But being queer is fun. It’s fun and it’s funny. I loved the part where Kima was complaining to Allura about her dress. My first girlfriend was a wonderfully creative seamstress, and she and I used to cosplay together, so - let’s just say it brought back some nice memories. Critical Role remedied the problems that the Queer People are Funny trope created almost as a direct result of its format - as a result of spending so much time trying to understand those characters. Queer characters can be funny again, and they can be tragic, and they can be well-rounded and human. I think there’s a magnificent capacity for greater understanding here. It makes me very, very excited for the next campaign. If they came this far in round one, I really hope round two nets us a queer player character or three, and I can’t wait to meet them.

#critical role#critical role thesis#well it's more or less on that same road but#cut from the Final Product#for space#y'know

697 notes

·

View notes

Text

Masculinity and Indian Fascism

1857, the year of the Sepoy Mutiny, was a watershed period in South Asia. Despite the civilising efforts of the evangelicals and the Utilitarians, the Indians persisted in and insisted on barbarism. The (alleged) sexual violence against “the angel in the house”, the defenceless British woman, around a sexualised and racialised hatred of the dark-skinned Hindus and Muslims. After the Mutiny, some 50 novels were written on the subject in the century. The novels focused on the mutineers' desire for white women for the harem: The harem served to symbolise the lack of masculine restraint among orientals. The “treacherous” massacre at Kanpur, where the well had been stuffed with the mutilated bodies of British women and children despite a promise of safe passage, was a sign of the unmanly character of the natives (Peter Van Der Veer, Imperial Encounters (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2006), p 86 - 87).

For Flora Annie Steele, author of On the Face of the Waters (1896), the brutal suppression of the Mutiny was “the epic of the British race”. According to The Guardian, Charles Dickens said: “I wish I were commander-in-chief in India ... I should proclaim to them that I considered my holding that appointment by the leave of God, to mean that I should do my utmost to exterminate the race.”

At the time, the Mutiny was viewed as a satanic uprising against the forces of justice. Public opinion howled for blood, and it paved the way for hanging prisoners and blowing them away from the mouths of cannons without trial. The earlier Christian view of war as God’s punishment changed to one where war was regarded as rightful action for a just cause.

In short, divine violence.

Evangelicals were not inclined to hero-worship or the glorification of war, which they regarded as divine retribution for sin. This opened them to charges of disloyalty during the French revolution. They located their heroes in missionaries like Livingstone, instead of men like Nelson. The latter were objects of nationalist hero-worship by the Victorians. However, the evangelical temper became more bellicose over the course of the nineteenth century. “Like the rest of the British nation, they came to see warfare as a kind of police action, to quell unrest, to prevent injustice (p 85).” Christian heroism came to be celebrated in the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny. The latter gave rise to the image of the brave Christian soldier, especially in the person of General Henry Havelock. Havelock, Edwardes, and the two brothers John and Henry Lawrence were all devout evangelical Christians. Havelock attributed British victory to British artillery and “to the blessing of Almighty God on a most righteous cause, the cause of justice, humanity, truth, and good government in India”.

Even before the Mutiny, the charge of effeminacy was being levelled against Indians - and the most Westernised, and most loyal of them, the “babus”, the brown, Anglicised gentleman (indeed, in Bengali today, babu is used both for infants and the delicately refined). Thomas Babbington Macaulay wrote in his essay on Warren Hastings (1843): “The physical organisation of the Bengalee is feeble even to effeminacy. He lives in a constant vapour bath. His pursuits are sedentary, his limbs delicate, his movements languid. During many ages he has been trampled upon by men of bolder and more hardy breeds. Courage, independence, veracity, are qualities to which his constitution and his situation are equally unfavourable. His mind bears a singular analogy to his body. It is weak even to helplessness for purposes of manly resistance ....”

Hindus lacked world-ordering, masculine rationality. According to Hegel, Hindus were guided by “feminine fantasies and imagination rather than by masculine reason” (van der Veer, p 95). Their very subjugation by Muslim tribesmen and then by the British testified to their effeminacy. Ultimately, however, the test of the “real” man came to the question of “honour” - which in British India, meant loyalty to Britain. The pan-Islamic Muslims failed the test, as did all Indians, whose languages, according to Robert Baden-Powell had no equivalent for the word - “izzut” was dismissed by Baden-Powell. “When in India I asked one or two Scouters what word they used for ‘Honour’ in teaching their boys character and they said ‘Izzut’. I asked two or three other men what was the Hindustani for ‘Honour’ and they could only suggest ‘Izzut’. But Izzut does not convey the idea of Honour (p 94).” When Baden-Powell remained intransigent on the matter, in 1937 the Boy Scout Association of India broke with the mother organisation. The writer observes: “That ‘Izzut’ was the central concept in Indian masculinity could not have escaped him in the years he had been an officer in the colonial army in India. This denial of the masculinity of the colonised was a central theme in British colonialism. Indians were seen as effeminate and weak in character.” Notions of British masculinity went hand in hand with the feminising of the colonised. However, muscular Christianity echoed in the rise of muscular Hinduism.

The firestorm of protest around the Age of Consent Act revealed the threatened masculinity of the Indian psyche. In 1891, the age of consent was raised from 10 to 12 years for Indian girls (and from 13 to 16 by the Criminal Law Amendment of 1885 for British girls). No other piece of colonial legislation in the nineteenth century so roused public opinion as this law. It was a dead letter, thanks to the strenuous opposition of the antireformists, who argued that it was an interference with Hindu religion and custom. “The law’s real effect was a reassertion of Hindu patriarchal control over the domestic sphere as a nationalist cause (p 96).” The reformists were accused of being Westernised.

The British regarded premature sexual intercourse as a sign of effeminacy. It was held to lead to masturbation and diabetes, among other things: A guiding notion behind the law was an eugenic one, namely, to improve the Indian race. The opponents described and decried the law as a deliberate British attempt to emasculate Hindu men. What riled them even more was the marital rape clause, which argued that sexual intercourse without the wife’s consent was rape - especially when the law in Britain gave the husband sexual access to the wife, always. Even reformist nationalists regarded this as an attack on the honour of the Indian man.

That there was a striking difference in discussion and debate about the twin laws in the metropole and the colony is due to the secure self-perception of the British regarding their masculinity and the precarious self-consciousness of Indians in this regard: the latter, reeling from accusations of femininity, were resolute to at least stay master in their own house.

Bankim Chandra Chatterjea asked and answered thus: “Why are Bengalis not courageous? The reason is simple: the physical is father to the moral man (1874).” The charge of effeminacy had been particularly galling for the Bengali elite, who sought redress in martial arts and physical culture. “It is paradoxical that both the colonosing British and the colonised Bengalis saw ‘Westernisation’ as a main cause for this emasculation (p 98).”

Most of the educational institutions were in the hands of Christian missionaries, whose aim was not the strengthening of the Hindu race, but its proselytisation. In response, Hindus, Mulsims and Sikhs initiated their own educational institutions, within an Anglicised curriculum. A similar trajectory of physical activity marked both the metropole and the colony. Football and cricket were eagerly taken up. “Cricket was a quintessentially masculine activity and expressed the codes that were expected to govern all masculine behaviour: sportsmanship, a sense of fair play, through control over the expression of strong sentiments by players on the field, subordination of personal sentiments and interests to those of the side, unquestioned loyalty to the team (Arjun Appadurai, quoted by van der Veer).”

Nationalist masculinity required the morphing of martial ascetics into fervent sportsmen. Traditionally, ascetics were mercenaries as well as traders and moneylenders. Prior to British colonial expansion in the second half of the nineteenth century, they dominated trade and money-lending in North India. The Fakir-Sannyasi Rebellion (circa 1770 - 1780) saw the end, under the Pax Britannica, of the world of the migrant ascetic trader-soldiers who serviced a network of pilgrimage-cum-trading centres. The advent of roads and railways transformed trade. In the subsequent half-century, the militant asceticism was laicised into martial arts and wrestling.

Lay wrestlers follow in the religious footsteps of the fighting ascetics. For instance, their mutual devotion to Hanuman, the monkey-god, is based on a connection between divine power (shakti) and physical strength (bal). Hanuman’s divine power stems from his devotion to the god Rama and his wife Sita. Shakti is feminine power that men can acquire through celibacy. The disciplines of wrestling and celibacy lead to self-control and the realisation of inward feminine power, enabling them to attain another female capacity: selfless devotion. “With Hanuman, this is a selfless devotion to the divine couple, but this devotion can, for fighting ascetics and wrestlers, be transformed through nationalist discourse into a selfless devotion to the cause of the nation (p 100).”

The British preoccupation with national degeneration has its equivalent in India. However, here the preoccupation is focused on the body, bodily fluids and food intake. The degeneration of the Indian people, according to the wrestlers, is due entirely to Westernisation and the decline of India’s ancient martial arts.

“It is especially the articulation of the notions of gender and sexuality with notions of race that strike me as typical of this period,” writes the author. “In the early twentieth century the articulation of physicality and morality under the aegis of nationalism develops into fascist forms of xenophobia both in Europe and India (p 101).”

Unlike in Britain, where masculine notions were interwoven with empire and the German threat, Hindu discourse on masculinity focused on the Muslim threat to Mother India (“the rape of the motherland”). Muslims were perceived as excessively masculine and militant. Being able to have four wives seemed extravagantly pleasurable and aroused masculine envy. The threat of “Muslim lust” to Hindu women appeared magnified during the age-of-consent controversy when Hindu masculinity felt threatened.

Race came to play a major part in this “paranoid nationalism”. From Europeans, Hindu ideologues took up the idea of the “Aryan race”, “to racialise the Hindu community and make the religious difference between them and Muslims into an immutable, racial one (p 101)”. The militant Aryans were extremely masculine and appealed to the need for national regeneration. The idea of a common Hindu race would serve to unify a disparate society. “As in Germany and Britain we find in India in the 1920s the combination of an ideal masculinity and a racial superiority connected to a heightened nationalism and an extreme fear of a minority within the population.”

The most disturbing culmination of the focus on youth, masculinity and militant nationalism was the founding of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the National Volunteers Corps, in 1925 by K. B. Hedgewar. “This is Hindu India’s most violent youth organisation with an ultra-nationalist and strongly anti-Muslim message (p 102).” Nathuram Godse, Mahatma Gandhi’s murderer, was a former RSS member. In his statement to the court in 1948, Godse explicitly stated his fear that Gandhi’s ideas “would ultimately result in the emasculation of the Hindu community”. On several occasions the RSS was banned by the Indian government, led by the Congress Party, for its alleged role in communal violence.

Like the wrestlers and fighting ascetics, the RSS also espouses a religious emphasis on masculine celibacy and Hanuman as the paradigm of selfless devotion and physical strength. However, unlike the former, the RSS is a centralised organisation with an overt political purpose, the remaking of multicultural India into Hindu India.

Hedgewar’s influence was the writings of the Hindu nationalist ideologue Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (aka Vir - great hero). He coined the term Hindutva in his book, written in prison, called Hindutva: Who Is A Hindu? (1923). Today, Hindutva is a major nationalist ideology.

Savarkar was implicated in the murder of Gandhi, but he was acquitted in his subsequent trial because of insufficient evidence. It is not surprising that Savarkar was strongly attracted to European fascism and that he admired Hitler.

The battle against Muslims displaced the battle against the British - and long before the departure of the latter. “The myth that Hindus lost their masculinity “under foreign occupation” first by Muslims and later by the British underlies much of Hindu nationalist discourse (p 104).” The excessive Other are two-fold: the hedonistic Westerner and the lustful, wily and hedonistic Muslim.

“They are fantasies produced by a lack of self-esteem.”

The Economist article Orange evolution: Narendra Modi and the struggle for India’s soul, with the suggestive subtitle How India’s prime minister uses Hindu nationalism, notes that in return for throwing its full weight behind Narendra Modi’s electoral campaign, Modi has inserted RSS men, or like-minded ones, into every part of Indian politics. The accompanying chart shows the level of infiltration as of February 2019: the president (Ram Nath Kovind), vice-president (Venkaiah Naidu), prime minister (Narendra Modi), speaker of lower house (Sumitra Mahajan), cabinet (12 of 25), other ministers (11 of 49), state governors (15 of 33), state chief ministers (8 of 31). “But RSS influence also extends to university deans, heads of research institutes, members of the board of state-owned firms and banks (including the central bank) and, say critics, ostensibly politics-proof promotions in the police, army and courts.”

#sepoy mutiny#masculinity#hinduism#british india#the raj#hindutva#rss#fascism#vinayak damodar savarkar#aryans#effeminate

1 note

·

View note

Text

Francesco Gabbani - Italia 21 (translation and explanation)

So, this song was deleted from YT last week and I was very upset, since it’s one of those older songs from Francesco that made me instantly like him.

I knew that it needed both a translation and a ‘paraphrase’ (like you would with a Latin version in high school LOL) to fully understand it and that took me SO LONG. It was very hard and I believe it’s still not complete yet: there’s something I still don’t get.

But! The most is done and I hope you’ll like it!

This is “Italia 21″ (Italy 21).

I’m not sure if this song was already traslated, I’m just gonna post my version :D

I’m not a professional translator so there might be some mistakes. I just hope to convey the message of the song to non-Italian speakers.

Uno. Pane e vino certo non ci manca

Due. Neanche il sole in quest’Italia santa

Tre. Una penisola col tacco a spillo

Quattro. Tutti parlano, ci manca solamente il grillo

One. We surely don’t lack bread and wine

Two. Nor we lack the sun, in this holy Italy

Three. A peninsula wearing an high heel

Four. Everybody talks, last thing we need is the cricket

Notes:

- Bread, wine and sun are what Italy is known for in the entire world. So it’s religion, that’s why the ‘holy’ adjective.

- Italy is said to be shaped like a boot. We also call the southern regions in Apulia “tacco” (heel). I believe the “high heel” reference is related to fashion, another thing we are known for worldwide.

- We have a common saying: “Il paese è piccolo, la gente mormora” (it’s a small town, people talk) which means that basically in small communities everyone knows everything and always voices their opinions. Italy is pretty much like a big “small town” and everyone always likes to talk. We’re very good at talking and having all kind of opinions.

- The “grillo” (cricket) reference is what made me instantly fall in love with this song right during the first listening. It’s pure genius.

It has a double meaning: the first is related to the Jiminy Cricket (or Talking Cricket), a character from famous Italian author Carlo Collodi’s book “Pinocchio”. It basically says that since everybody likes to talk already, we really don’t need to hear from the Talking Cricket, known for being Pinocchio’s conscience and dispenser of good advices, but never listened to. The second reference I believe it’s about Beppe Grillo, infamous ex-comedian and now leader of political movement “Movimento Cinque Stelle” (the links lead to Wikipedia, if you’re curious about them).

The most interesting thing is noticing how Francesco made a subtle criticism of this (known for being loud and obnoxious) politician by using a word play and a very ironic and cultured reference.

Cinque. San Gennaro, grazie che ci Sei!

Sette. Senza di te che numeri giocherei?

Otto. La nazione piscia controvento

Nove. Ma noi siamo tutti fieri del Risorgimento

Five. St. Januarius, thanks for exSIXting!

Seven. Without you, which numbers would I bet?

Eight. The nation pisses upwind

Nine. But we are all proud of our Risorgimento

Notes:

- St. Januarius is a very important saint in the Italian culture, especially in the Neapolitan area. The “number betting” thing is related to another popular tradition (mainly in Naples, I believe) consisting in praying the Saint to suggestions about which numbers to play at the Lottery.

- Number six of this list is the “sei” at the end of the first line. Once again a word play: the word “six” is written and pronounced exactly like the second person singular of the “be” (essere) verb.

- Another saying: “Chi piscia controvento si bagna i pantaloni” (who pisses upwind wets his own pants), which means “never take challenges too big for you”. Related to Italy I believe it may mean that we consider our nation much bigger and more influential than how it actually is and we take challenges way bigger than our real potential. Why is that?

- Because we are conditioned by our long, rich history and heroical past. One example above all might have been Ancient Rome or the Reinaissance period, but Francesco wisely chose the Risorgimento: when Italy was reunited under the same flag and monarchy after a series of wars, battles and campaigns against foreign occupation. Why is that? Maybe once again to be very ironical about Italians being actually proud of being united in one country, since there are still a lot of differences and fights between North and South.

Dieci. Chi svolta il mese con il contagocce

Undici. A chi la polpa e a chi le bucce

Dodici. Per fortuna arriva il 1° maggio

Tredici. Abbiamo tante, tante fave ma non c’è il formaggio

Ten. Those who turn the month in dribs and drabs

Eleven. Some get the pulp and some the peels

Twelve. Luckily, the 1st of May always arrives

Thirteen. We’ve got lots and lots of beans but we haven’t got the cheese

Notes:

- “Svoltare il mese con il contagocce” (turning the month with the tear dropper) and “a chi la polpa e a chi le bucce” are there to express how the economy has a lot of flaws in Italy, especially in the relation between riches (who has got the “pulp”, the money and wellness) and poors (the ones having difficulties gaining enough to live by, month after month).

- The 1st of May is International Work Day and it’s an holiday. It’s also sometimes used as a “middle point” during the working year.

- Fave e pecorino (broad beans and sheep cheese) is a typical dish of Central Italy and Rome in particular. It’s a 1st of May tradition to eat them together, especially because since it’s an holiday and it’s Spring, people used to go have trips and pic-nics in the countryside, where they bought beans and cheese directly from the farmers. Francesco is using the dish as another way of saying we’ve got the side dish (vegetable or beans), the theories and good words, but we haven’t got the main course (the cheese), what matters.

Quattordici. C’è chi magna e non fa una piega

Quindici. Ma alla fine cosa ce ne frega?

Sedici. Tutti fermi, inizia la partita

Diciassette porta sfiga. Il corno in terra, cazzo! E’ già finita

Fourteen. There’s who eats and doesn’t bat an eye

Fifteen. But in the end who cares?

Sixteen. Everyone stay still, the game is on

Seventeen brings bad luck. The lucky horn on the floor, fuck! It’s already over

Notes:

- I am having some difficulties pin-pointing where the first sentence is from. It looks like another saying (”magna” is generally the dialect version of “mangia” and it’s mostly associated with Roman dialect) but I’ve never heard anything similar (it might be because I am from Northern Italy, tho). Anyway “non fare una piega” litterally translates to “don’t make a wrinkle” and it’s used both to say that something makes complete sense or that someone has absolute no reaction to something. So basically who eats (presumably those rich people from the previous verse?) doesn’t care about anything/anyone else and/or no one questions it.

- “Cosa ce ne frega” is, imho, the best way to describe the Italian attitude toward problems. It basically means “what do WE care?” with a very personal connotation. How do you solve unsolvable (or very hard) problems? Whatever, who cares anyway... not our business.

- Italians love football and that’s common knowledge. To quote Winston Churchill: “Italians lose wars as if they were football matches, and football matches as if they were wars.” So true, Winston.

- We are also very supertitious. The cornetto is one of the many objects believed to be lucky charms. I have no idea why you have to put it on the ground, tho? (Neapolitans, explain please!). The number 17 is also believed to be very unlucky (that’s why you need a corno to nullify its powers. But while you complete the rituals, you get distracted and the match ends!)

Diciotto. Viva l’Italia col microfono in mano

Diciannove. Canto anch’io che sono un italiano

Venti. Un bel bicchiere di rosso e due pennette

Ventuno. Due cazzeggi all’osteria e un Tressette

(Osteria numero sette! *paraponzi ponzi pò*

Il salame piace a fette

dammela a me, biondina

dammela a me, biondà!)

Eighteen. Long live Italy with a microphone in the hand

Nineteen. I sing I’m an Italian as well

Twenty. One fine glass of red (wine) and some penne

Twentyone. Some messing around at the pub and a round of Tressette

(Pub number seven! *paraponzi ponzi pò*

Salami is good cut in slices

give it to me, pretty blonde girl

give it to me, blondie!)

Notes:

- Pretty sure the “Italia con il microfono in mano” is a reference to Sanremo, the most famous singing competition in Italy. It may also mean in general everything that has to do with Italian music, tho. Something along the line of “long live Italian music!”, even though his relationship with the industry at the time wasn’t the best and he had struggles surfacing as an artist. Would he ever imagine, at the time, that he would win Sanremo two years in a row? Bless you, Francesco.

- A quote from the famous “L’italiano” song by Toto Cutugno. Just like “Italia 21″ that song too was an attempt to describe Italy and the Italians from within.

Another fun fact: Toto is the last Italian singer who won the Eurovision Song Contest. Is this a lot of foreshadowing or not? (Maybe too much!)

- A glass of wine and pasta. What’s better? Here’s a quick and easy prescription to happiness, by every Italian ever.

- “Cazzeggio” is litterally “a thing done with one’s dick” and means messing around, having fun with friends by basically doing nothing. Tressette is a popular card game in Italy.

- What follows is something we call stornello, a type of folk song which basically has a standard melody and ever changing lyrics. They are usually very funny, irreverent and sexual. “La canzone delle osterie” is famous everywhere and Francesco used it to end the song in the most carefree way.

- He rhymed “sette” with “fette” but I really don’t know how to explain if “salami is good cut in slices” is a sexual reference. Salami can definitely be associated with something sexual (c’mon...) but I have no clue about the rest. I’m an innocent soul XD

- “Give it to me” is DEFINITELY sexual. Especially referred to a pretty blonde girl XD That too is usually part of the standard stornello lyrics ;)

Wow, this took SO LONG.

I hope it helped understand this song in depth, even though something is still obscure even to me, after translating and spending a lot of time looking things up on the internet.

Have fun find other interpretations, maybe? ;)

73 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! My question follows one of your recent responses. You mentioned that your favorite 'husband' is Okita (yes! I share it completely), your favorite pairing is HeiChi (for solid reasons) and your favorite character is Kazama due to his complexity. If you want, could you expand this statement? Why is Kazama so complex in your opinion, what are the possible reasons of his complexity (his inner conflict, his motives etc)?

Ohhhh man… ‘If I want’? I’m always down to talk about my faves. You’d best be prepared for a goddamn characterization essay, because I love Kazama to death. Also, it’ll be good practice for getting started on an actual essay, so I thank you for this wonderful way to wake up the brain!!

I’m throwing this under a read-more for those of you who can see it, because wow I talk a lot:

First off, let me get one thing straight: I hate Kazama. I don’t hate him in the same way or as much as I hate Kaoru; my ‘hatred’ for Kazama is rooted more in awe (e.g. “Wow, that was badass, but what an asshole”) than in genuine dislike (e.g. “I AM GOING TO SKIP ALL YOUR TEXT AND THEN KILL YOU”). By no means is Kazama a good person, but one doesn’t have to be a good person to be a good character.