#feminist spatial theory

Text

[“… Jensen states in the imperative that one cannot liberate masculinity from itself; one instead must destroy it. In Jensen’s words: “One response to this toxic masculinity has been to attempt to redefine what it means to be a man, to craft a kinder-and-gentler masculinity that might pose less of a threat to women and children and be more livable for men. But such a step is inadequate; our goal should not be to reshape masculinity but to eliminate it.”

The allusion to “elimination” here is extremely noteworthy. Eliminate, comes from the Latin eliminatus, meaning “to be turned out of doors” or “through a threshold”—which also connotes to put an end to something; to kill, destroy, or make somebody or something ineffective; to defeat and put a player or team out of a competition; to remove something as irrelevant or unimportant; and interestingly, last but nowhere near least, to expel waste from the body. This is curious. Part of what Jensen suggests with this rhetoric of elimination is that, in addition to surrendering the desire to reconstruct masculinity—something he claims is an inadequate response—masculinity instead needs to be categorically destroyed, removed, killed off, and, expelled as waste.

Of course, the claim here is supported by both of the teleologies and tautologies in Jensen’s logic: “I get erections from pornography. I take that to be epistemologically significant.” Jensen concludes two points about the male body and its sexual responses: first, it is involuntary in its responsiveness; and second, that such responsiveness itself is a priori evidence of abject, irresolvable culpability and guilt. Masculinity writ noncomplicitous remains unthinkable.

Such corporeal self-evidence and abjection are precisely what Judith Butler has cautioned against in her work while, at the same time, acknowledging the vitality of the unthinkable in other ways and on different terms. Although Jensen, Dworkin, and Butler each write the impossible body as the effect of heteronormative hegemonies, Butler’s construction of embodiment differs from Jensen’s. Where he details a body constructed by its overdetermined biological need to occupy and destroy femaleness as a drive toward achieving normalized manhood, for Butler, the body is the effect of normative social processes and can, in turn, “occupy the norm in myriad ways, exceed the norm, rework the norm, and expose realities to which we thought we were confined as open to transformation.”

In other words, where matter for Jensen must inscribe no possibility of excess, Butler finds rearticulation as a fundamental part of why matter must be inhabited in excess of itself and incoherently for both theory and politics.

“Bodies are not,” Butler writes, “inhabited as spatial givens. They are, in their spatiality, also underway in time: aging, altering shape, altering signification—depending upon their interactions—and the web of visual, discursive, and tactile relations that become part of their historicity, their constitutive past, present, and future.”

What emerges vis-à-vis Jensen’s rearticulation of antipornography feminism and masculinity is precisely the opposite of what Butler seeks to map. Jensen’s is a flow of affect not only grounded in mimesis, or an assumption of realism without mediation. Instead it is affect produced relationally (as a mediation between text and audience), an affect that is also heavily invested in constituting masculinity through problematic and very limited subject positions: the only feminist affect available for masculinity is self-punishment, despair, and debilitating pathos. Jensen punctuates and performs such pathos throughout his text by lamenting, “I am sad. It feels like there are few ways out” for a masculinity trapped in the guilty male body and for whom elimination is the only remedy.”]

bobby noble, from Knowing Dick: Penetration and the Pleasures of Feminist Porn’s Trans Men, from the feminist porn book: the politics of producing pleasure, edited by tristan taormino, constance henley, and celine perreñas shimizu, 2013

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Care to Cure and Back

Under the umbrella of the LINA platform a program From Care to Cure and Back was initiated by Ana Dana Beroš in collaboration with the Association of Architects of Istria (DAI-SAI). "Treat, cure and give care again", is the idea behind this program, says Ana Dana and stress how important is to deal with experimental publishing practices in architecture.

Ana Dana Beroš at the Publishing Acts: The Publishing School Pedagogies of Care in Rijeka (2020). | Photo © Matija Kralj Štefanić

She is referring how care was and is missing in the formal education of architecture, in the form of a humanistic way of thinking and asking background questions, which primarily concern the users of buildings. With the construction of the state, public projects fell into the background. It became clear that we must learn from our own history, repair, preserve and take care together, and not build unnecessarily.

How will architecture change in the future?

ADB: It will change drastically. I ask myself all the time is it ethical to build anymore? Or should we be focusing on “the great repair” of the broken world? Or is it broken architecture, or mankind, or more than human environment? This question are arising because we were witnessing for more than half of century the capitalist modernity, with its emphasis on innovation, growth, and progress, its economic system based on consumerism and wasteful use, and profligacy, has led to a ruthless exploitation of humans and nature.

Architecture has played a huge small part in this, as the statistics on greenhouse gas emissions and construction and demolition waste prove. As a counter-strategy to capitalism’s creative destruction, we should focus on the repair, in which nurturing and maintenance that should become the key strategies for the action.

Publishing Acts I-II-III (2017-2020) | Photo © Matija Kralj Štefanić, collage Ana Dana Beroš

This is not just mine thinking, the notions of care in architecture have been part of many international exhibitions starting from the Critical Care at the Architektur Zentrum in Viena curated by Elke Krasny and Angelika Fitz, the term The Great Repair was used by Milica Topalović and her team at ETH, then are here Pedagogies of the Broken Planet. This is how I see the future.

What does your critical spatial practice include?

ADB: My critical spatial practice has components of artistic research, documentary filmmaking, curating, publishing/broadcasting, exhibition design, activism and post-disciplinary de-schooling. This is work that overlaps, diverges, converges, runs in parallel, in circles, and in many cases came before and goes beyond.

A whole multitude of practitioners and theorists have been developing work in an expanded field such as this, quite different perhaps from the one Rosalind Krauss identified in 1979. Critical spatial practice was coined by the theorist Jane Rendell in 2000s as a helpful way of describe projects located between art and architecture, that both critiqued the sites into which they intervened as well as the disciplinary procedures through which they operated.

LINA - DAI-SAI programme From Cure to Care and Back. | Photo © Ana Dana Beroš

Taking into account the wide spectrum of intellectual fields close to architecture and space - from urban anthropology to human geography - I consider connecting architecture with feminist theory crucial for the development of critical spatial practices. Gender-based analysis of architecture, its multiple forms of representation, where subjects and spaces are viewed as performatives and constructs, is aimed primarily at questioning the world around us.

Moreover, critical spatial practices are necessarily self-critical and tend to change society, in contrast to orthodox architectural practices that seek to maintain and strengthen the existing social and spatial order of inequality.

How is the LINA platform important for your development on architecture of care?

ADB: I have started Architecture of Care actually developing through the concept of Pedagogies of Care within the predecessor platform to LINA, the former Future Architecture. The Publishing School: Pedagogies of Care is an exploration on how we learn and produce knowledge collectively through emancipatory practices of care. The program builds upon the three Publishing Acts and their collective efforts in shaping unordinary publications, unlikely publics and unorthodox spatial imaginaries.

Publishing Acts, The Publishing School -Pedagogies of Care (Rijeka, 2020). | Design © Marin Nižić

Can radio become again a media for architecture (like in the time of Wright) and in which way you work with it?

ADB: Regarding the radio, as a powerful architectural tool, or to the media that architecture uses, I can agree with many who say that architecture has nowadays become transmedial. We don’t create only in the offline dimension, in concrete and brick, but in the online sphere as well. All media are allowed, or rather necessary, to attain goals of architecture. I have been involved in radio forever as been working for Croatian radio HR3, I have been developing the Radio Schools with artists during the Pedagogies of Care. As our colleagues from dpr-barcelona we claim to this cover that radio is louder than bombs that relates to their motto.

Beside radio you work is also dedicated on documentary film?

ADB: My documentary work is dedicated both to architecture and migration topics. Within the Croatian Architects’ Association I have been leading, then co-leading a documentary project Man and Space and working as a scriptwriter on long feature documentaries dedicated to the life achievement laureates.

Geotrauma - Ana Dana Beros and Matija Kralj Štefanić at the V Magazine. | Foto © Marija Gašparović

In pluriannual research on the relational reading of migrant bodies and migrant territories, conducted together with the artistic partner and cinematographer Matija Kralj Štefanić, we have been departing from nonrepresentational theories, the practices of witnessing that produce knowledge without contemplation. The experimental documentary trajectory builds on previous investigations in the Mediterranean: in reception camps (Contrada Imbriacola, Lampedusa), hotspots (Moria, Lesbos), makeshift camps (Idomeni, Greece), urbanized camps (Dheisheh, Palestine), city refugees (Mardin, Turkey), and, recently, in the Balkans, where we live.

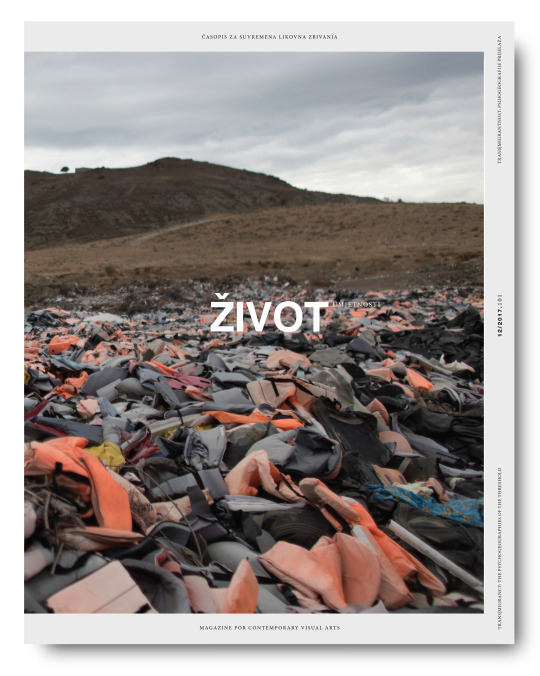

Transmigrancy - Life of Art Magazine, 101-2017 edited by Ana Dana Beroš: Geotrauma. Photo © Matija Kralj Štefanić (design bilic mueller studio)

We refined methods of producing critical, nonrepresentational images, and of gathering and documenting evidence found in borderscapes, in order to make a transmedial and migratory archive, a border documentarism, that is in constant articulation. After the pandemic, from mute images of migrants’ residuals that speak for themselves, we have started creating a polyphony of protagonists of migrant origin and those involved in the No Border movement in a documentary series Three-Voiced: Stories on the Move, broadcast in Croatia. As a contemporary response to the rise of fascist phenomena in Europe, In the era of fetishizing borders and territorialization of bodies, it was crucial to start resonating in a new voiced register for topics that are not heard, or rather systematically not listened to in our societies.

It is just one of many attempts at confronting structures of silencing, asking: Can we, through collective vibration, transform silence into a path of newfound hope and solidarity?

How Intermundia opened an important topic of transmigration in Europe?

ADB: Back in 2014, Intermundia research project questioned alternating border-scapes of trans-European and intra-European migration. The focus was put on the Italian island of Lampedusa, metonymy for contemporary Western conditions of confinement. For me, back then it was clear that the dominant discourses on illegal migration obscure the role of international migration as a regulatory labour market tool. It was important to stress that migrants must be conceived primarily as workers, not only as immigrants. It seemed that, in the pre-pandemic times of constant mobility, involuntary territorial shifts of the precarious workers was parallel to the detention of undesired migrants.

Intermundia at the Venice Biennial in 2014. | Foto © Ana Opalić

Instead of observing Lampedusa as a consolidated institution of the waiting room, as a jailed zone in the middle of conflict, Intermundia attempted a post-human perspective in order to investigate the ambivalent state of in-betweenness. I was aware of the impossibility of cultural translation of such a condition, the understanding of the Other, so the project Intermundia, exhibited and awarded at the Architecture Biennial in Venice 2014, challenged visitors to immerse themselves into a coffin-like light and sound installation. Inducing Verfremdungseffekt, the project asked for solemnity and re-action, and not simply empathy.

I am not sure Intermundia opened the important topic of migration in Europe, but for sure it was a predecessor to the summer of migration in 2015, with the great influx of migrants, refugees and the formation of the so-called Balkan Route.

What does architecture mean to you?

ADB: I dare to say that the fundamental task architecture has is to articulate spatial thinking, thinking capable of asking questions about burning issues of our society in a different way, hence of also creating a different reality. Architecture must offer a space for understanding of the existential condition of an individual and of society, and must also construct a foundation for a life with dignity. We know who we are, and where we belong, precisely through human constructions, both material and intellectual.

Intermundia "Io sono Africanicano". | Photo © Ana Dana Beroš

Ana Dana Beroš (b. 1979) is an architect based in Zagreb, but often explores contested borderscapes of Europe and beyond. Co-founder of ARCHIsquad - Division for Architecture with Conscience and its educational program UrgentArchitecture in Croatia. Her interest is architectural theory, experimental design and publishing as spatializing practice led her to co-found Think Space (2010-2015) and Future Architecture (2016-2021) international platforms, and currently LINA (2022-2025). The LINA member DAI-SAI ongoing project From care to cure and back, under her curation, explores critical architectural heritage on the case of The Children’s Maritime Health Resort of Military Insured Persons in Krvavica, and encourages transformation of both material and immaterial environments from spaces of a common disease into places of common healing. Her project Intermundia on trans- and intra-European migration was a finalist for the Wheelwright Prize at GSD Harvard, and received a Special Mention at the XIV Venice Architecture Biennale curated by Rem Koolhaas (2014). In her pluriannual research and relational reading of migrant bodies and migrant territories, she departs from non-representational theories, the practices of “witnessing” that produce knowledge without contemplation. The fragments of the migratory archive, a border documentarism formed together with the filmmaker and cinematographer Matija Kralj Štefanić, have been made public in different forms and formats, exhibitions and publications (2016-2022) – and lately within a documentary series Three-voiced: Stories on the move (2022-).

Here You can listen to the WELTRAUM interview

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

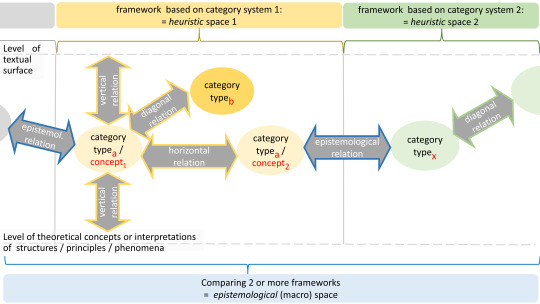

"The complexity and multi-layered nature of “topos” as a category, historically going back to antiquity, provides an opportunity to systematize the interdependencies between categorial elements in the concrete research design. The starting point was the “relationality” of topoi – i.e. the assumptions that a topos needs to be (re)constructed in relation to other topos concepts and that the category “topos” should be defined in relation to other categories. The basic principles observable in this specific context of the development and application of categories are transferable to other contexts. The paper proposes a typology differentiating vertical, horizontal, heuristic and episte"

"A decision in designing the conceptual model is that categories and categorial relations can be organized within a heuristic space. [...] The heuristic space consists of three axes: In addition to the vertical and horizontal relations, there is the diagonal relation between categories that do not belong to the same class. [...] Another important conceptual distinction of the spatial model are three different levels: The level of the textual surface refers directly to the object of investigation, e.g. a text corpus. On the opposite side lies a deep structure, which represents the level of theoretical concepts or interpretations of the realm of phenomena. In the middle or in the space in between, categories and concepts operate, building a bridge between the other two levels."

Maria Hinzmann: Categorial Relations in (Re)constructing Topoi and in (Re)modeling Topology as a Methodology: Vertical, horizontal, heuristic and epistemological interdependencies. Digital Humanities Quarterly Volume 17 Number 3 2023

---------------------------------

Cut zurück zur anderen Notiz über Dietmar Dath's Topologie

---------------------------------

Dietmar Dath - Neptunation. 2019

Über Topologien, und Netzwerke in der digitalen Kunstgeschichte:

Wenn seit Emmy Noether die Kartierungen Teil der mathematischen Forschung sind (vgl. Lee, C. (2013) Emmy Noether, Maria Goeppert Mayer, and their Cyborgian Counter-parts: Triangulating Mathematical-Theoretical Physics, Feminist Science Studies, and Feminist Science Fiction), bis hin zu Maryam Mirzakhani (in Dietmar Daths Nachruferzählung und in der Raumerzählung “Du bist mir gleich” wird das was diese Mathematik mit dem Denken macht in seiner Tragik und transformativen Kraft spürbar), dann ist das was die Netzwerk-Coder (z.B. Fan/Gao/Luo (2007) “Hierarchical classication for automatic image annotation”, Eler/Nakazaki/Paulovich/Santos/Andery/Oliveira/Neto/Minghim (2009) “Visual analysis of image collections”) und Google Arts & Culture in die digitale Kunstwissenschaft eingeführt haben, man kann es nicht anders sagen, das Gegenteil von all dem. Unhinterfragte Kategorien und unhinterfragte konzeptuelle Graphen (also sowohl Lattice Theorie, als auch Topologie ignorierend), werden ohne Binaritäten oder Äquivalente einfach als gerichtete Graphen, entweder strukturiert von den alten Ordnungen, oder, das soll dann das neue sein, als Mapping von visueller Ähnlichkeit gezeigt (vgl. die Umap Projekte von Google oder das was die Staatlichen Museen als Visualisierungs-Baustein in der neuen Version ihrer online Sammlung veröffentlicht haben). Wenn dann das Met Museum mit Microsoft und Wikimedia kooperiert, um die Kontexte durch ein Bündnis von menschlicher und künstlicher Intelligenz zu erweitern - nämlich Crowdsourcing im Tagging, und algorithmisches Automatisieren der Anwendung der Tags, dann fehlen einfach die radikalen Mathematiker*innen, die diese Technologien mit dem Implex der Museumskritik verbinden können, um ein Topos-Coding durchzuführen, das die Kraft hätte den Raum des Sammelns zu transformieren, so das nichts mehr das Gleiche bliebe. Während die heutigen Code-Künstler*innen großteils im Rausch der KI-Industrie baden, bleiben es einzelne, wie Nora Al-Badri (“any form of (techno)heritage is (data) fiction”), die zum Beispiel in Allianz mit einer marxistischen Kunsthistorikerin die Lektüre des Latent Space gegen das Sammeln wenden (Nora Al-Badri, Wendy M. K. Shaw: Babylonian Vision), und so Institutional Critique digitalisieren.

“Was Künstlerinnen und Künstler seit Erfindung der »Institutional Critique«, deren früher erster Blüte auch einige der besten Arbeiten von Broodthaers angehörten, an Interventionen in die besagten Räume getragen und dort gezündet haben, von neomarxistischer, feministischer, postkolonialer, medienkritischer, queerer Seite und aus unzähligen anderen Affekten und Gedanken, die sich eben nicht allesamt auf eine Adorno’sche »Allergie« wider das Gegebene reduzieren lassen, sondern oft auch aus einer Faszination durch dieses, einer Verstrickung in sein Wesen und Wirken geprägt war, liegt in Archiven bereit, die ausgedehnter und zugänglicher sind als je zuvor in der Bildgeschichte. Den Tauschwert dieser Spuren bestimmen allerorten die Lichtmächte. Ihr Gebrauchswert ist weithin unbestimmt. Man sollte anfangen, das zu ändern.” Dietmar Dath Sturz durch das Prisma. In: Lichtmächte. Kino – Museum – Galerie – Öffentlichkeit, 2013. S. 45 – 70

0 notes

Text

Aledis the Blue Yorkie

Meet Aledis, a Littlest Pet Shop OC (original character) that I created on October 2019. Before I could tell information about this character, I like to say what I have done on February 2, 2024 in the morning. Initially, I was going to archive more files that I considered necessary and that were only found in a desktop computer that used to run Windows 7. Unfortunately, when I started up said desktop computer, I found out that it has been broken down sometime after the end of support of the Professional and Enterprise volume licensed versions, making most of them lost media. What a pity that I couldn't archive them before that software rot!

In compensation of what happened to the older computer, I had to write the following information of this original character from memory:

Name: Aledis

Age: More or less the same as Brown Yorkie

Species: Dog (Yorkshire Terrier)

Gender: Cisgender female

Personal gender pronoun: She/Her

Alignment: Social good

Likes: Literature (especially fiction books and poems), rationalism, science (especially physics) and art

Dislikes: Pseudoscience, fringe theories, blockchain and similar concepts, negative evaluation

Description: Aledis is a blue-furred Yorkshire Terrier that is commonly seen wearing a wreath of flower in her left ear and a green bandana in one of her forelegs. She also has a white star-shaped birthmark that is slightly hidden in her neck's fur. Namewise, Aledis' attitude is described as being intelligent, innovative, progressive, adventurous, and slightly rebellious. As a result, Aledis herself is feminist and will fight for animal rights. Despite being a ratter, Aledis can spare the lives of rodents, including mice and rats. However, she has fear of negative evaluation and a slight spatial anxiety. In some occasions, she is able to take one for the team when necessary. She is depicted as the cousin of Brown Yorkie and is rational enought to be skeptical about magic and paranormal events.

Biography: Aledis was born in Pets Plaza (a place that is found exclusively on the 2008 video game adaptation of Littlest Pet Shop) along with her two siblings. One day, Aledis was suddenly become displaced from her original dimension. To make matters worse, she discovers that the planet she is sent to, the Glade of Dreams, contains hostile beings that are more dangerous compare to that of her native parallel world. In order to deal with it, Aledis uses the survival skills her mother taught earlier. During the journey, she meets a like-minded dweller of the Glade of Dreams that she befriends. Eventually, both of them are sent to a more peaceful world and, over time, she befriends two more female nonhuman characters from different parallel universes.

If anyone asks when Aledis appeared for the first time, the earliest drawings featuring her were first posted on Rayman Pirate Community, as I have a currently inactive account and Aledis used to be the co-mascot of this account along with a Rayman OFC (original female character). As drawn in an approximately five-year-old paper, she originally looked like this in an old artstyle:

Yes, the older picture is a model sheet in the form of traditional art, and it is written in Spanish. By January 2023, I have improved this art style to the current one (such as the digital art I have made for Aledis) so that I removed these drawing quirks found on her head for consistency. Therefore, it's time to give her a chance to make a comeback.

Aledis the Blue Yorkie © Me (@piscessheepdog)

Littlest Pet Shop © Hasbro (previously owned by Kenner)

#aledis the blue yorkie#littlest pet shop#lps art#digital art#fan art#fanart#lps oc#original character#original female character#littlestpetshop#yorkshire terrier#oc original character#dog oc

1 note

·

View note

Note

Helloww, as a fellow literature student... what's a favourite theory/critic/movement of yours?

Oh hi, what a fun question, thank you so much!!!! 🥰

I'd say I'm generally not very set on any school or theory which is most likely due to the fact that my uni isn't very keen on teaching different theories, sadly.

But I looooove anything coming out of cultural studies! So obviously feminist and gender and queer theory, but what I reeeeeaaaally love as well is spatial theory, idk if that even counts as a distinct theory tbh, but.... spaces. My beloved <3

Oh and I love theories that go a bit into sociology, like field theory, my beloved <3

As for critics, can't say I have a favorite. I mean there are the "classics" that inform lots of my views on literature, but no one I know a lot from.

As for movements!!! Honestly, anything from the 19th century on is very much my jam. I love naturalism and I love expressionism, but also lots of the smaller (sub)movements like Wiener Moderne or Dada. All in all I'm a big fan of Modernism and some of the stuff that happened like... on the brink of Modernism (depending on the definition of Modernism you wanna go by)!

1 note

·

View note

Text

In general, men tend to have thicker tails than women in IQ distribution tables, which are the extreme values.[16] Technically speaking, men have larger standard deviations. The further away from the mean you go, the more men are at both the bottom and the top, and the more women are in the middle to upper quartile, which is closer to the mean.[17] A 2016 meta-study by Baye and Monseur, which pooled databases from the Program for International Educational Achievement and the Program for International Student Assessment, found that men fluctuate about 14% more than women.[18] However, an extended meta-study by Helen Gray and colleagues in 2019 found that regions with higher female labor force participation tended to have higher female variability, which in turn narrowed the gap between men and women.[19] Although these are all findings from meta-studies, meta-studies are not perfect, and statistical trends vary across different social contexts, and there is a risk of perpetuating gender stereotypes, so the variability hypothesis continues to stimulate debate in modern academia.

This is largely due to the fact that the extremes are found in "math"[20] and "spatial"[21] skills[22], whereas most (if not all) other intellectual abilities do not show extremes and, on average, do not show significant gender differences.[23][24][25][26] Recent research suggests that variability also exists in reading comprehension: while math and spatial are evenly represented at the top and bottom of the scale, reading comprehension is uniquely male-dominated, with a greater proportion of men at the bottom than at the top of the scale. This is called the "Greater Male Variability Hypothesis" (GMVH) in the jargon.[27][28] The difference is greatest at the bottom, where males show a greater variance, but females also show a higher proportion at the top. The standard deviation is about twice as large when standardized to a normal distribution, and various theories and hypotheses have been proposed to explain this, but none of them have been conclusively proven. In any case, it is clear that there is a statistical difference between the two. There is also a clear tendency for the variability between men and women to change depending on the social situation in each region, so there is a view that the difference between the sexes is not explained solely by biology, but is also influenced by cultural differences, differences in test subjects, or circumstances. It may be necessary to look at it from a comprehensive perspective.

In addition, modern IQ tests cannot accurately test innate intelligence, which is absolutely influenced by education. A 2017 meta-study in the Archives of Psychology confirmed that education raises IQ scores by 1-5 points per time period, or at least improves performance on IQ tests."[29]

A recent meta-study confirmed that the gender gap in variability is closing in some developed countries. While it is true that men have always been more variable in most populations, there have been a few outliers in some countries and some races where male extremes have been absent. There is also evidence to suggest that a number of social factors are driving much of the variability."[30] In conclusion, the difference in the distribution of IQs between men and women (larger standard deviations for men) is more likely to be due to cultural factors than innate differences. However, the meta-study cites research by a feminist scholar specializing in women's studies, as well as some controversial statistics, so there may be some room to jump to conclusions.

A 2002 study by Dr. Horst Hameister of the University of Ulm in Germany, published in the British scientific journal New Scientist, found that as many as 10 percent of genetic defects that can cause mental disorders are X-chromosome abnormalities, and that the X-chromosome contains a gene associated with superior intelligence. In women, the X chromosome of this gene has a 1 in 2 chance of being inactivated instead of the X chromosome with the other normal intelligence-related gene, but men, who are XY chromosomal, have only one X chromosome, so it is hypothesized that inheriting an X chromosome with a gene associated with mental disorders or high intelligence from a parent may cause the gene to be expressed, resulting in male extremes. Of course, this hypothesis is not without controversy, as the fact that the X chromosome is larger, heavier, and X-inactivated (but not completely inactivated) means that XX is potentially more likely to produce more diverse genetic combinations than XY.

There is also research that suggests that male and female sex hormones explain the intelligence gap described above. "Research has shown that testosterone promotes the development of brain regions responsible for spatial and math skills, while the female hormone estrogen develops parts of the brain associated with language skills," says Mark Brosnan, who led the study. "These same hormone secretions also appear to correlate with the length of the index and ring fingers."

In addition, psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen argues that higher prenatal testosterone levels favor the brain's ability to systemize, which is why men are more likely than women to have an aptitude and interest in math and science. However, as a side effect, they are less likely to be empathetic and verbal, and more likely to have autism. Conversely, lower prenatal testosterone levels favor the development of empathy in the brain, making women more likely to be good at communication and language than men.

0 notes

Text

_thinkMake Week 3 Reading

This week's reading was 'Only Resist - a feminist approach to critical spatial practice' by Jane Rendell. I found this text quite hard to decipher.

This key parts I picked out from this text were:

Architecture as a profession was historically ‘masculine’ and male dominated in the early 1900s and before, due to the lack of women’s right to work.

Identity is an important aspect of the human condition and so should have the space to exist.

Representation is important when making spaces.

From the text, I picked out the 5 main qualities that characterise the feminist approach to critical space practice:

Collectivity - the importance of collaboration in the creation of something. Women's voices must be heard during the design process of anything, as women are often ignored and not considered, or designed for without being consulted.

Subjectivity - life is often thought about in binary opposites, whereas most things in life are subjective and rely on contextual clues. Historically, architecture has been a men's profession and interior design was a woman's. However, this is not the case.

Alterity - the state of being 'other' or different. Intersectionality is the combination of race, class and gender and how they overlap to create further discrimination and disadvantage. It is important to consider everyone when designing something so that no one is disadvantaged.

Performativity - the interdependent relationship between certain words and actions. Using text as a platform to create performance and action allows a deeper understanding of the text, and has been developed through feminist practices.

Materiality - an object being composed of a material and its qualities. It is important to think about where materials are sourced from, and the processes that take place for that material to be where it is today. It is also important to think about what using a particular material in a design means for the human and non-human actants of the space.

The 7 words I picked out were:

Radical

Marginalisation

Historical - to archive

Critique - to critique

Intersectionality

Theory

Contribution - to provide

The drawing that I created represents the 'normal' way of doing something, and how this conflicts with a 'new' way of doing something. This relates to the idea of being radical and having new theories.

0 notes

Text

“Queer Phenomenology” By Sarah Ahmed

Sara Ahmed shows how phenomenology can be effectively applied to queer studies in this ground-breaking work. Ahmed explores what it means for bodies to be placed in space and time by focusing on the "orientation" component of "sexual orientation" and the "orient" in "orientalism." As people move through the world, directing their movements towards or away from people and objects, their bodies create shape. Being "orientated" refers to having a sense of security, awareness of one's location, or access to objects. What is close to the body or what can be reached depends on the orientation. According to Ahmed, a queer phenomenology demonstrates how social ties are spatially organised, how queerness disrupts and reorders these relations by deviating from the norm, and how a politics of disorientation brings additional objects into reach, even if they initially appear to be out of the ordinary.

Ahmed suggests that a queer phenomenology might investigate both the orientation of phenomenology itself as well as how the concept of orientation is informed by it. She considers the relevance of the items that show as signals of orientation—and those that do not—in early phenomenological works like Husserl's Ideas. She integrates ideas from queer studies, feminist theory, critical race theory, Marxism, and psychoanalysis with readings of phenomenological works by Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Fanon to create a queer model of orientations. Queer Phenomenology offers radical new directions for queer theory.

Phenomenology means, the study of appearance and how people interact with things in the world as they encounter us through our senses. Phenomenology is the study of these interaction, how we interact with things in their immediacy, how we think about them, reflect on them and how they become meaningful to us. Ahmend interrogates how some objects seem to draw some more, than others. Why are we oriented to some objects in some ways, as opposed to others, in other ways. Ahmed examens how phenomenology is always to some extent, queer, in that it doesn’t point in a single, neutral direction it instead picks and chooses some things to understand to grasp over others, it doesn’t assume a single linear form. Drawing upon history, being that of colonization, patriarchy, racism, all these histories influence what phenomenology is capable of recognizing, and what it is not capable of recognizing.

How can we intergrade theses different perspectives so that phenomenology is not biased because of these things. How can we expand the category of phenomenology to account for its own queerness, its own skewedness, but do it to undo the very specific skewedness that we have, to include different perspectives.

Ahmed explains how we should rethink phenomenology to such an extent, in the sense that the world is not organized to accommodate all people in a neutral way, but only reflects the interest of those who are in power. And that world then conforms to them, and they can move freely and easily for them. Because of that it is even more difficult for them to recognize that there is anything wrong at all, especially in the case of disability, with something like the height of doorknobs, which seems perfectly normal for someone able bodied of a certain height, but for people with difficulty using doorknobs, it becomes a huge barrier of someone trying to move freely though the world.

The operation of queer phenomenology is to break through the neutral mindscape to consider the possibility that some spaces, experiences and appearances aren’t so neat as to just lend themselves into our senses and can be huge hinderances, limitations for certain people and the phenomenological engagement that they will have with it is not a neutral one. Queer phenomenology is the practice then, of considering how certain spaces, certain objects, have been given the status of neutrality, of objectivity but then undoing that through the consideration of other perspectives, allows space in the world for everyone to move freely rather than conform to privilege.

Ahmed engages in a discussion with Judith Butler, whom she quotes: “Heterosexual genders form themselves through the renunciation of the possibilities of homosexuality, as a foreclosure which produces a field of heterosexual objects at the same time as it produces a domain of those whom it would be impossible to love” (Butler, 1993). Through repeated movements that bend our bodies in a specific direction, this heterosexual field is generated. This reasoning, although with a phenomenological twist, makes us think of what Butler defines as "repetitive performativity" (Butler, 1993). Ahmed illustrates how bodies take on the shape against the predetermined background over time by thinking back on events in her own family's home, such as how they sat at the dinner table and the generations' worth of family photos hanging on the wall, all of which point in the general direction of heterosexual lines.

Acting and existing in accordance with these principles shapes bodies into forms that "enable some action only insofar as they restrict the capacity for other kinds of action”. (Ahmed, 2006, p. 91). The internalised societal norms and actions orientate our bodies towards heterosexual objects, just as our act of writing causes our orientation towards the writing table and other gathered objects. This creates a field where some objects are drawn closer while other objects become non-perceptible. So how do bodies develop a queer orientation in the face of such a dominant force?

But a keen reader would see that forced heterosexuality occasionally fails to control our bodies. When bodies encounter an object that is not supposed to be there, such as another queer body or another "contingent lesbian," new lines of direction are created (p. 107). Ahmed points out that the Latin word for "contact" and contingent share a common root. A body departs the grid of heterosexual lines after being drawn by desire.

As a result, the body needs to be reoriented by assembling and drawing closer other items that are normally invisible or out of reach in the heterosexual field. In other words, for a body to change its orientation and become a lesbian, it needs to make touch with other items. Of course, there are risks associated with these options. The straightening tools and other people's perspective are always trying to bring bodies that wander offline back into the field of heterosexual objects. Ahmed's empowering voice, which addresses gay bodies at the chapter's conclusion and cautions against interpellation:

“Yes, we are hailed; we are straightened as we direct our desire as women toward women. For a lesbian queer politics, the hope is to reinhabit the moment after such hailing...we hear the hail, and even feel its force on the surface of the skin, but we do not turn around, even when those words are directed toward us. Having not turned around, who knows where we might turn. Not turning also affects what we can do. The contingency of lesbian desire makes things happen” (Ahmed, 2006, p.107).

In conclusion, Ahmed states: “The question is not so much finding a queer line but rather asking what our orientation toward queer moments of deviation will be. If the objects slip away, if its face becomes inverted, if it looks odd, strange, or out of place, what will we do?” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 179). We can perceive how our actions change our bodies and our orientation towards the things we work with thanks to queer phenomenology. We become aware of other items that may have been hidden from view during the procedure. That doesn't mean other orientations should be replaced by gay orientation.

With this awareness, we could, nevertheless, think about many paths that connect our body to various objects. We are grouped around various items, which congregate on various grounds, as stated throughout the text. Perhaps the issue is ethical: while we are disoriented, we must be aware that there is a chance to learn about ourselves, other people, and entire worlds that we were previously unable to notice. Only then can we rapidly put the unfamiliar thing out of our line of sight and regain our bearings.

0 notes

Photo

𝗙𝗟𝗘𝗔𝗕𝗔𝗚

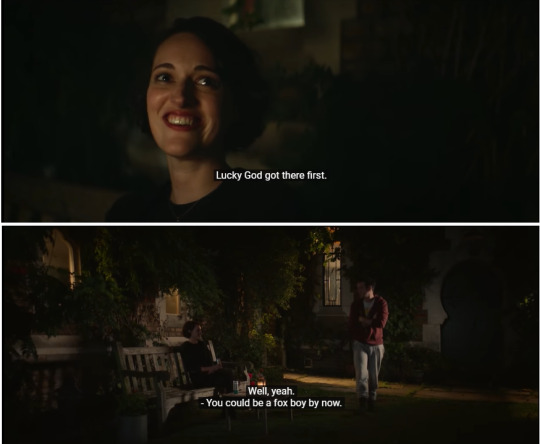

Fleabag is a British comedy-drama series about a woman in her 30's who is navigating her life and finding love while coping with the death of her bestfriend. The protagonist's coping mechanism in the difficulty of life were expressed through thick sarcasm, sexual liberation, and humor which made the other characters think that she is obnoxious and exhausting to be with. Fleabag seems to be very distant from everyone and seems to have a thick layer of walls which makes her perceived as a difficult woman, when, in fact, she is having a hard time in directing her own life and she is genuinely longing to be loved. There are so many things to unpack in this series including its feminist narrative and its nameless main character — Fleabag. The series has very few characters and some of them are just labeled as Dad, Godmother, and The Priest or Hot Priest, which makes it very open to character interpretations while being enclosed in the mystery of not knowing who they really are. Moreover, the greatest twist of the series, which is Fleabag's routine of breaking the fourth wall, has ignited speculations all through out the series. In this blog, I will focus on the semiotics of one scene in Episode 3 from Season 2 where the Hot Priest shared his great fear on foxes.

Before we dig in this particular episode, the context is that there is already an unspoken tension between The Priest and Fleabag; Fleabag fancies the Hot Priest. In this episode, the Hot Priest and Fleabag were having drinks in the garden in a night time and they were talking about existence and religious beliefs. The Priest have said that Fleabag's meaningless existence challenges him, but he ends up getting closer to God. In the middle of their casual conversation, The Priest panicked because he kind of heard scratches behind the bush and he assumes that it is a fox. The audience did not a see a fox, but there is this sound effects that makes everyone think that there is indeed something behind the bush. The scene effectively conveyed that the Priest is frightened because of his facial expression. His wide eyes, anxious movements, and shaky hands were signifying that he is very scared of the possible presence of the fox. There is also a spatial mode that conveys his fright because he really moved away from the bush. Meanwhile, Fleabag is unbothered and amused of the situation. She was just laughing while observing the nervous movements of the Priest.

Through a verbal narrative, the Priest shared his encounters with foxes and he talked about how he think that they are always after him. One of the many encounters he had with a fox was in the middle of his sleep in a monastery. He woke up to a fox sitting underneath his window which he thinks it was trying to say to him that they are watching him and they will be having him. Fleabag said, "Lucky God got there first. You could be a fox boy by now." The Priest replied, " Well yeah. And we all know what happened to them." This entire fox scene can be perceived as a mere fear on something — a fox in literal. But if we will pay attention to the possible connotation out of these multimodal and semiotics, we can arrive in a deeper and meaningful interpretation from the Priest's character and his fear on foxes.

There are already a lot of theories in the internet as to what does the fox represents; there are theories that it signifies either God, the Priest's trauma, or sin. I do agree with the latter theory because the Priest always jumps and says, "I thought you were a fox" in occasions that he did not anticipate Fleabag's presence. In the previous paragraph, I have mentioned that the Priest admitted that Fleabag's meaningless existence challenges his faith. Fleabag unapologetically admits her behavior that are sinful for a religiously devoted person and she did not deny that she wants something to happen between them. This is a strong foundation to derive that the fox's signified meaning is a sin. The temptations of being sinful follows the Priest for a long time and he is again challenged upon meeting Fleabag.

At the end of the series, Fleabag and the Hot Priest confessed their love for each other but the Priest chose God. They literally parted ways at the end; going to opposite directions which also signifies the different paths in life that they are both taking. After the Priest went on his way, a fox appeared on the street and Fleabag directed the fox on which way the Priest went. The fox followed the way to the Priest which gives rise to another speculation that sins would still follow him.

Superficially, scenes are just scenes. It depends on the audience as to what extent would they make out of something. In this episode, the fox scene could just be another humorous scene but if we will really analyze a film, it opens to a wider scope of imagination by considering the signifiers used by the creatives and paying attention to the dialogues of the characters.

Artwork Credits: @weeean from Pinterest

0 notes

Text

Assistant Professor Tenure-track Position in GIS, Cartography and Transformation

The University of British Columbia

Application Deadline: 2022-09-15

The Department of Geography at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver) invites applications for a tenure-track Assistant Professor position in GIS, Cartography and Transformation.

The successful candidate will use and advance theories, methods, and technologies in cartography, GIS, spatial analysis, or geographical computing to address theoretical and empirical insights from other areas of geography. We are particularly interested in applicants whose work in GIS and cartography intersect with one or more of emerging and long-term strengths in our department, including the study of climate change, climate justice, political ecology, urban geography, migration, feminist and Black geographies, political economy, Indigenous geographies, socio-spatial inequality, physical geography, health geography, and environmental sustainability.

Applicants are expected to have a record of or demonstrated potential for research excellence and an ability to initiate and maintain an outstanding e...

See the full job description on jobRxiv: https://jobrxiv.org/job/the-university-of-british-columbia-27778-assistant-professor-tenure-track-position-in-gis-cartography-and-transformation/?feed_id=18960

#ScienceJobs #hiring #research

0 notes

Text

The Dead Ladies Club

“Ladies die in childbed. No one sings songs about them.”

The Dead Ladies Club is a term I invented** circa 2012 to describe the pantheon of undeveloped female characters in ASOIAF from the generation or so before the story began.

It is a term that carries with it inherent criticisms of ASOIAF, which this post will address, in an essay in nine parts. The first, second, and third parts of this essay define the term in detail. Subsequent sections examine how these women were written and why this aspect of ASOIAF merits criticism, exploring the pervasiveness of the dead mothers trope in fiction, the excessive use of sexual violence in writing these women, and the differences in GRRM’s portrayals of male sacrifice versus female sacrifice in the narrative.

To conclude, I assert that the manner in which these women were written undermines GRRM’s thesis, and ASOIAF -- a series I consider to be one of the greatest works of modern fantasy -- is poorer because of it.

*~*~*~*~

PART I: WHAT IS THE DEAD LADIES CLUB?

Below is a list of women I personally include in the Dead Ladies Club. This list is flexible, but this is generally who people are talking about when they’re talking about the DLC:

Lyanna Stark

Elia Martell

Ashara Dayne

Rhaella Targaryen

Joanna Lannister

Cassana Estermont

Tysha

Lyarra Stark

the Unnamed Princess of Dorne (mother to Doran, Elia, and Oberyn)

Brienne’s Unnamed Mother

Minisa Whent-Tully

Bethany Ryswell-Bolton

EDIT - The Miller’s Wife - GRRM never named her, but she was raped by Roose Bolton and she gave birth to Ramsay

I might be forgetting someone

Most of the DLC are mothers, dead before the series began. I deliberately use the word “pantheon” when describing the DLC because, like the gods of ancient mythology, these women typically loom large over the lives of our current POVs, and it is their deification that is largely the problem. The women of the Dead Ladies Club tend to be either heavily romanticized or heavily villainized by the text, either up on a pedestal or down on their knees, to paraphrase Margaret Attwood. The DLC are written by GRRM as little more than male fantasies and tired tropes, defined almost exclusively by their beauty and desirability (or lack thereof). They have no voices of their own. Too often they are nameless. They are frequently the victims of sexual violence. They are presented with few or no choices in their stories, something I consider to be a particularly egregious oversight when GRRM says it is our choices which define us.

The space in the narrative given over to their humanity and their interiority (their inner lives, their thoughts and feelings, their existence as individuals) is minimal or nonexistent, which is quite a shame in a series that is meant to celebrate our common humanity. How can I have faith in the thesis of ASOIAF, that people’s “lives have meaning, not their deaths,” when GRRM created a coterie of women whose main if not sole purpose was to die?

I restrict the Dead Ladies Club to women one or two generations back because the Lady in question must have some immediate connection to a POV character or a second-tier character. These women tend to be of immediate importance to a POV character (mothers, grandmothers, etc), or at most they’re one character removed from a POV character in the main story (AGOT - ADWD+).

Example #1: Dany (POV) --> Rhaella Targaryen

Example #2: Davos (POV) --> Stannis --> Cassana Estermont

*~*~*~*~

PART II: "NOW SAY HER NAME.”

Lyanna Stark, “beautiful, willful, and dead before her time.” We know little about Lyanna other than how much men desired her. A Helen of Troy type figure, an entire continent of men fought and died because “Rhaegar loved his Lady Lyanna”. He loved her enough to lock her in a tower, where she gave birth and died. But who was she? How did she feel about any of these events? What did she want? What were her hopes, her dreams? On these, GRRM remains silent.

Elia Martell, “kind and clever, with a gentle heart and a sweet wit.” Presented in the narrative as a dead mother, a dead sister, a deficient wife who could bare no more children, she is defined solely by her relationships with various men, with no story of her own outside of her rape and murder.

Ashara Dayne, the maiden in the tower, the mother of a stillborn daughter, the beautiful suicide, we get no details of her personality, only that she was desired by Barristan the Bold and either (or perhaps both) Brandon or Ned Stark.

Rhaella Targaryen, a Queen of the Seven Kingdoms for more than 20 years. We know that Aerys abused and raped her to conceive Daenerys. We know that she suffered many miscarriages. But what do we know about her? What did she think of Aerys’s desire to make the Dornish deserts bloom? What did she spend 20 years doing when she wasn’t being abused? How did she feel when Aerys moved the court to Casterly Rock for almost a year? We don’t have answers to any of these questions. Yandel wrote a whole history book for ASOIAF giving us lots and lots of information on the personalities and quirks and fears and desires of men like Aerys and Tywin and Rhaegar, so I know who these men are in a way that I don’t know the women in canon. I don’t think it’s reasonable that GRRM left Rhaella’s humanity virtually blank when he had all of TWOIAF to elaborate on pre-series characters, and he could have easily made a little sidebar on Queen Rhaella. We have a lot of dairies and letters and stuff about the thoughts and feelings of real medieval queens, so why didn’t Yandel (and GRRM) give us a little more about the last Targaryen queen in the Seven Kingdoms? Why didn’t we even get a picture of Rhaella in TWOIAF?

Joanna Lannister, desired by both a King and a King’s Hand and made to suffer for it, she died giving birth to Tyrion. We know there was “love between” Tywin and Joanna, but details about her are few and far between. With many of these women, the scant lines in the text about them often leave the reader asking, “well, what does that mean exactly?” What does it mean exactly that Lyanna was willful? What does it mean exactly that Rhaella was mindful of her duty? Joanna is no exception, with GRRM’s teasing yet frustratingly vague remark that Joanna “ruled” Tywin at home. Joanna is merely the roughest sketch in the text, seen through a glass darkly.

Cassana Estermont. Honestly I tried to recall a quote about Cassana and I realized that there wasn’t one. She is the drowned lover, the dead wife, the dead mother, and we know nothing else.

Tysha, a teenage girl who was saved from rapers, only to be gang-raped on Tywin Lannister’s orders. Her whereabouts become something of a talisman for Tyrion in ADWD, as if finding her will free him from his dead father’s long, black shadow, but aside from the sexual violence she suffered, we know nothing else about this lowborn girl except that she loved a boy deemed by Westerosi society to be unloveable.

For Lyarra, Minisa, Bethany, and the rest, we know little more than their names, their pregnancies, and their deaths, and for some we don’t even have names.

I often include Lynesse Hightower and Alannys Greyjoy as honorary members, even though they’re obviously not dead.

I said above that the DLC are either up on a pedestal or down on their knees. Lynesse Hightower is both, introduced to us by Jorah as a love story out of the songs, and villainized as the woman who left Jorah to be a concubine in Lys. In Jorah’s words, he hates Lynesse, almost as much as he loves her. Lynesse’s story is defined by a lot of tired tropes; she is the “Stunningly Beautiful” “Uptown Girl” / “Rich Bitch” “Distracted by the Luxury” until she realizes Jorah is “Unable to support a wife”. (All of these are explained on tv tropes if you would like to read more.) Lynesse is basically an embodiment of the gold digger trope without any depth, without any subversion, without really delving into Lynesse as a person. Even though she’s still alive, even though lots of people still alive know her and would be able to tell us about her as a person, they don’t.

Alannys Greyjoy I personally include in the Dead Ladies Club because her character boils down to a “Mother’s Madness” with little else to her, even tho, again, she’s not dead.

When I include Lynesse and Alannys, every region in GRRM’s Seven Kingdoms has at least one of the DLC. That was something that stood out to me when I was first reading - how widespread GRRM’s dead mothers and cast off women are. It’s not just one mother, it’s not just one House, it’s everywhere in GRRM’s writing.

And when I say “everywhere in GRRM’s writing,” I mean everywhere. Mothers killed off-screen (typically in childbirth) before the story begins is a trope GRRM uses throughout his career, in Fevre Dream and Dreamsongs and Armageddon Rag and in his tv scripts. It’s unimaginative and lazy, to say the least.

*~*~*~*~

PART III: WHO ARE THEY NOT?

Long dead, historical women like Visenya Targaryen are not included in the Dead Ladies Club. Why, you ask?

If you go up to the average American on the street, they’ll probably be able to tell you something about their mother, or their grandmother, or their aunt, or some other woman in their lives who is important to them, and you can get an idea about who these women were/are as people. But the average American probably won’t be able to tell you a whole lot about Martha Washington, who lived centuries ago. (If you’re not American, substitute “Martha Washington” with the name of the mother of an important political figure who lived 300 years ago. I’m American, so this is the example I’m using. Also, I can already hear the history nerds piping up - sit down, you’re distinctly above average.)

In this same fashion, the average Westerosi should (misogyny aside) usually be able to tell you something about the important women in their lives. In real life history, kings and lords and other noblemen shared or preserved information about their wives or mothers or sisters or w/e, in spite of the extremely misogynistic medieval societies they lived in.

So this isn’t “OMG a woman died, be outraged!!1!” kind of thing. This isn’t that.

I generally limit the DLC to women who have died relatively recently in Westerosi history and who are denied their humanity in a way that their male contemporaries are not.

*~*~*~*~

PART IV: WHY DOES IT MATTER?

The Dead Ladies Club are the women of the previous one or two generations that we should know more about, but we don’t. We know little more about them than that they had children and they died. I don’t know these women, except through transformative fandom. I know a lot about the pre-series male characters in the text, but canon gives me almost nothing about these women.

To copy from another post of mine on this issue, it’s like the Dead Ladies exist in GRRM’s narrative solely to be abused, raped, give birth, and die, later to have their immutable likenesses cast in stone and put up on pedestals to be idealized. The women of the Dead Ladies Club aren’t afforded the same characterization and growth as pre-series male characters.

Think about Jaime, who, while not a pre-series character, is a great example of how GRRM can use characterization to play with his readers. We start off seeing Jaime as an asshole who pushes kids out of windows, and don’t get me wrong, he’s still an asshole who pushes kids out of windows, but he’s also so much more than that. Our perception as readers shifts and we understand that Jaime is so complex and multi-layered and grey.

With dead pre-series male characters, GRRM still manages to do interesting things with their stories, and to convey their desires, and to play with reader perceptions. Rhaegar is a prime example. Readers go from Robert’s version of the story that Rhaegar was a sadistic supervillain, to the idea that whatever happened between Rhaegar and Lyanna wasn’t as simple as Robert believed, and some fans even progress further to this idea that Rhaegar was highly motivated by prophecy.

But we don’t get that kind of character development with the Dead Ladies. For example, Elia exists in the narrative to be raped and to die, and to motivate Doran’s desires for justice and revenge, a symbol of the Dornish cause, a reminder by the narrative that it is the innocents who suffer most in the game of thrones. But we don’t know who she is as a person. We don’t know what she wanted in life, how she felt, what she dreamed of.

We don’t get characterization of the DLC, we don’t get shifts in perception, we barely get anything at all when it comes to these women. GRRM does not write pre-series female characters the same way he writes pre-series male characters. These women are not given space in the narrative the same way their male contemporaries are.

Consider the Unnamed Princess of Dorne, mother to Doran, Elia, and Oberyn. She was the only female ruler of a kingdom while the Robert’s Rebellion generation was coming up, and she is also the only leader of a Great House during that time period that we don’t have a name for.

The North? Ruled by Rickard Stark. The Riverlands? Ruled by Hoster Tully. The Iron Islands? Ruled by Quellon Greyjoy. The Vale? Ruled by Jon Arryn. The Westerlands? Ruled by Tywin Lannister. The Stormlands? Steffon, and then Robert Baratheon. The Reach? Mace Tyrell. But Dorne? Just some woman with no name, oops, who the hell cares, who even cares, why bother with a name, who needs one, it’s not like names matter in ASOIAF, amirite? //sarcasm//

We didn’t even get her name in TWOIAF, even though the Unnamed Princess was mentioned there. And this lack of a name is so very limiting - it is so hard to discuss a ruler’s policy and evaluate her decisions when the ruler doesn’t even have a name.

To speak more on the namelessness of women... Tysha didn’t get a name until ACOK. Although they were named in the appendices in book 1, neither Joanna nor Rhaella were named within the story until ASOS. Ned Stark’s mother wasn’t named until the family tree in the appendix of TWOIAF. And when will the Unnamed Princess of Dorne get a name? When?

As I think about this, I cannot help but think of this quote: “She hated the namelessness of women in stories, as if they lived and died so that men could have metaphysical insights.” Too often these women exist to further the male characters, in a way that doesn’t apply to men like Rhaegar or Aerys.

I don’t think that GRRM is leaving out or delaying these names on purpose. I don’t think GRRM is doing any of this deliberately. The Dead Ladies Club, imo, is the result of indifference, not malevolence.

But these kinds of oversights like the Princess of Dorne not having a name are, in my opinion, indicative of a much larger trend -- GRRM refuses these dead women space in the narrative while affording significant space to the dead/pre-series male characters. This issue, imo, is relevant to feminist spatial theory, or the ways in which women inhabit or occupy space (or are prevented from doing so). Some feminist scholars argue that even conceptual “places” or “spaces” (like a narrative or a story) have an influence on people’s political power, culture, and social experience. Such a discussion is probably beyond the scope of this post, but basically it’s argued that women/girls are socialized to take up less space than men in their surroundings. So when GRRM refuses narrative space to pre-series women in a way that he does not do to pre-series men, I feel like he is playing into misogynistic tropes and tendencies rather than subverting them.

*~*~*~*~

PART V: THE DEATH OF THE MOTHER

Given that many of the DLC (although not all) were mothers, and that many died in childbirth, I want to examine this phenomenon in more detail, and discuss what it means for the Dead Ladies Club.

Popular culture has a tendency to prioritize fatherhood by marginalizing motherhood. (Look at Disney’s long history of dead or absent mothers, storytelling which is merely a continuation a much older fairytale tradition of the “symbolic annihilation” of the mother figure.) Audiences are socialized to view mothers as “expendable,” while fathers are “irreplaceable”:

This is achieved by not only removing the mother from the narrative and undermining her motherwork, but also by obsessively showing her death, again and again. […] The death of the mother is instead invoked repeatedly as a romantic necessity […] there appears to be a reflex in mainstream popular visual culture to kill off the mother. [x]

For me, the existence of the Dead Ladies Club is perpetuating the tendency to devalue motherhood, and unlike so much else about ASOIAF, it’s not original, it’s not subversive, and it’s not great writing.

Consider Lyarra Stark. In GRRM’s own words, when asked who Ned Stark’s mother was and how she died, he tells us laconically, “Lady Stark. She died.” We know nothing of Lyarra Stark, other than that she married her cousin Rickard, gave birth to four children, and died during or after Benjen’s birth. It’s another example of GRRM’s casual indifference toward and disregard for these women, and it’s very disappointing coming from an author who is otherwise so amazing. If GRRM can imagine a world as rich and varied as Westeros, why is it so often the case that when it comes to the female relatives of his characters, all GRRM can imagine is that they suffer and die?

Now, you might be saying, “dying in childbirth is just something that happens to women, so what’s the big deal?” Sure, women died in childbirth in the Middle Ages at an alarming rate. Let’s assume that Westerosi medicine closely approximates medieval medicine - even if we make that assumption, the rate at which these women are dying in childbirth in Westeros is inordinately high compared to the real Middle Ages, statistically speaking. But here’s the kicker: Westerosi medicine is not medieval. Westerosi medicine is better than medieval medicine. To paraphrase my friend @alamutjones, Westeros has better than medieval medicine, but worse than medieval outcomes when it comes to women. GRRM is putting his finger down on the scales here. And it’s lazy.

Childbirth, by definition, is a very gendered death. And it’s how GRRM defines these women - they gave birth, and they died, and nothing else about them matters to him. (“Lady Stark. She died.”) Sure, there’s some bits of minutia we can gather about these women if we squint. Lyanna was said to be willful, and she had some sort of relationship with Rhaegar Targaryen that the jury is still out on, but her consent was dubious at best. Joanna was happily married, and she was desired by Aerys Targaryen, and she may or may not have been raped. Rhaella was definitely raped to conceive Daenerys, who she died giving birth to.

Why are these women treated in such a gendered manner? Why did so many mothers die in childbirth in ASOIAF? Fathers don’t tend to die gendered deaths in Westeros, so why isn’t the cause of death more varied for women?

And why are so many women in ASOIAF defined by their absence, as black holes, as negative space in the narrative?

The same cannot be said of so many fathers in ASOIAF. Consider Cersei, Jaime, and Tyrion, but whose father is a godlike-figure in their lives, both before and after his death. Even dead, Tywin still rules his children’s lives.

It’s the relationship between child and father (Randyll Tarly, Selwyn Tarth, Rickard Stark, Hoster Tully, etc) that GRRM gives so much weight to relative to the mother’s relationship, with notable exceptions found in Catelyn Stark and Cersei Lannister. (Though with Cersei, I think it could be argued that GRRM isn’t subverting anything -- he’s playing into the dark side of motherhood, and the idea that mothers damage their children with their presence -- which is basically the flip side of the dead mother trope -- but this post is already a ridiculous length and I’m not gonna get into this here.)

*~*~*~*~

PART VI: THE DLC AND SEXUAL VIOLENCE

Despite his claims to historical verisimilitude, GRRM made Westeros more misogynistic than the real Middle Ages. Considering that the details of their sexual violence is the primary information we have about the DLC, why is so much sexual violence necessary?

I discuss this issue in depth in my tag for #rape culture in Westeros, but I think it deserves to be touched on here, at least briefly.

Girls like Tysha are defined by the sexual violence they experienced. We know about Tysha’s gang rape in book 1, but we don’t even learn her name until book 2. So many of the DLC are victims of sexual violence, with little or no attention given to how this violence affected them personally. More attention is given to how the sexual violence affected the men in their lives. With each new sexual harassment Joanna suffered because of Aerys, we know per TWOIAF that Tywin cracked a little more, but how did Joanna feel? We know that Rhaella had been abused to the point that it appeared that a beast had savaged her, and we know that Jaime felt extremely conflicted about this because of his Kingsguard oaths, but how did Rhaella feel, when her abuser was her brother-husband? We know more about the abuse these women suffered than we do about the women themselves. The narrative objectifies rather than humanizes the DLC.

Why did GRRM’s messianic characters have to be conceived through rape? The mother figure being raped and sacrificed for the messiah/hero is an old and tired fantasy trope, and GRRM does it not once, but two (or possibly even three) times. Really, GRRM? Really? GRRM doesn’t need to rely on raped dead mothers as part of his store-bought tragic backstory. GRRM can do better than that, and he should do better. (Further discussion in my tag for #gender in ASOIAF.)

*~*~*~*~

PART VII: MALE SACRIFICE, FEMALE SACRIFICE, AND CHOICE

Now, you might be asking, “It’s normal for male characters to sacrifice themselves, so why can’t women sacrifice themselves for the messiah? Isn’t female sacrifice subversive?”

Male sacrifice and female sacrifice are often not the same in popular culture. To boil it down - men sacrifice, while women are sacrificed.

Women dying in childbirth to give birth to the messiah isn’t the same thing as male characters making some grand last stand with guns blazing to give the Messianic Hero the chance to Do The Thing. The male characters who get to go out guns blazing choose that fate; it’s the end result of their characterization to do so. Think of Syrio Forel. He chooses to sacrifice himself to save one of our protagonists.

But women like Lyanna and Rhaella and Joanna they didn’t get a choice, were afforded no grand moment of existential victory that was the culmination of their characters; they just died. They bled out, they got sick, they were murdered -- they-just-died. There was no grand choice to sacrifice themselves in favor of saving the world, there was no option to refuse the sacrifice, there wasn’t any choice at all.

And that’s key. That’s what lies at the heart of all of GRRM’s stories: choice. As I said here,

“Choice […]. That’s the difference between good and evil, you said. Now it looks like I’m the one got to make a choice” (Fevre Dream). In GRRM’s own words, “That’s something that’s very much in my books: I believe in great characters. We’re all capable of doing great things, and of doing bad things. We have the angels and the demons inside of us, and our lives are a succession of choices.” It’s the the choices that hurt, the choices where good and evil hang in the balance – these are the choices in which “the human heart [is] in conflict with itself,” which GRRM considers to be “the only thing worth writing about”.

Men like Aerys and Rhaegar and Tywin make choices in ASOIAF; women like Rhaella don’t have any choices at all in the narrative.

Does GRRM not find the stories of the Dead Ladies Club worth writing about? Was there no moment in GRRM’s mind when Rhaella or Elia or Ashara felt conflicted in their hearts, no moment they felt their loyalties divided? How did Lynesse feel choosing concubinage? What of Tysha, who loved a Lannister boy, but was gang-raped at the hands of House Lannister? How did she feel?

It would be very different if we were told about the choices that Lyanna and Rhaella and Elia made. (Fandom often speculates about whether, for example, Lyanna chose to go with Rhaegar, but the text remains silent on this issue as of ADWD. GRRM remains silent on these women’s choices.)

It would be different if GRRM explored their hearts in conflict, but we’re not told anything about that. It would be subversive if these women actively chose to sacrifice themselves, but they didn’t.

Dany is probably being set up as a woman who actively chooses to sacrifice herself to save the world, and I think that’s subversive, a valiant and commendable effort on GRRM’s part to tackle this dichotomy between male sacrifice and female sacrifice. But I don’t think it makes up for all of these dead women sacrificed in childbirth with no choice.

*~*~*~*~

PART VIII: CONCLUSIONS

I hope this post serves as a working definition of the Dead Ladies Club, a term which, at least for me, carries a lot of criticism of the way GRRM handles these female characters. The term encompasses the voicelessness of these women, the excessive and highly gendered abuse they suffered, and their lack of characterization and agency.

GRRM calls his characters his children. I feel like these dead women -- the mothers, the wives, the sisters -- I feel like these women were GRRM’s stillborn children, with nothing left of them but a name on a birth certificate, and a lot of lost potential, and a hole where the heart once was in someone else’s story. From my earliest days on tumblr, I wanted to give voice to these voiceless women. Too often they were forgotten, and I didn’t want them to be.

Because if they were forgotten -- if all they were meant to do was die -- how could I believe in ASOIAF?

How can I believe that “men’s lives have meaning, not their deaths” if GRRM created this group of women merely to be sacrificed? Sacrificed for prophecy, or for someone else’s pain, or simply for the tragedy of it all?

How can I believe in all the things ASOIAF stands for? I know that GRRM does a great job with Sansa and Arya and Dany and all the other female POVs, and I admire him for it.

But when ASOIAF asks, “what is the life of one bastard boy against a kingdom?" What is one life worth, when measured against so much? And Davos answers, softly, “Everything” ... When ASOIAF says that ... when ASOIAF says that one life is worth everything, how can people tell me that these women don’t matter?

How can I believe in ASOIAF as a celebration of humanity, when GRRM dehumanizes and objectifies these women?

The treatment of these women undermines ASOIAF’s central thesis, and it didn’t need to be like this. GRRM is better than this. He can do better.

I want to be wrong about all this. I want GRRM to tell us in TWOW all about Lyanna’s choices, and I want to learn the name of the Unnamed Princess, and I want to know that three women weren’t raped to fulfill GRRM’s prophecy. I want GRRM to breathe life into them, because I consider him to be the best fantasy writer alive.

But I don’t know that he will do that. The best I can say is, I want to believe.

*~*~*~*~

“Ladies die in childbed. No one sings songs about them.”

But I sing of them. I do. Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story...

*~*~*~*~

PART IX: FOOTNOTES AND MISCELLANEOUS

**I am 90% certain that I am the person who invented the term “Dead Ladies Club”, but I am not 100% certain. It sounds like a name I would make up, but a lot of my friends who I would talk to about this on their blogs in 2011 and 2012 have long since deleted, so I can’t find the first time I used the term, and I can’t remember anymore. Some things that should not have been forgotten were lost, history became legend, legend became myth, y'all know the drill.

To give you a little more about the origins of this term, I created my sideblog @pre-gameofthrones because I wanted a place for the history of ASOIAF, but mostly I wanted a place where these women could be brought to life. During my early days in fandom, so many people around here were writing great fanfiction featuring these women, fleshing out these women’s thoughts and feelings, bringing them to life and giving them the humanity that GRRM denied them. I wasn’t very interested in transformative works before ASOIAF, but suddenly I needed a place to preserve all of these fanfics about these women. Perhaps it sounds silly, but I didn’t want these women to suffer a second “death” and to be forgotten a second time with people deleting their blogs and posts getting lost in tumblr’s terrible organization system.

Over the years, so many other people have talked about and celebrated the Dead Ladies Club: @poorshadowspaintedqueens, @cosmonauthill, @lyannas, @rhaellas, @ayllriadayne, @poorquentyn, @goodqueenaly, @arielno, @gulbaharsultan, @racefortheironthrone and so many others, but these were the people I remembered off the top of my head, and I wanted to list them here because they all have such great things to say about this, so check them out, go through their archives, ask them stuff, because they’re wonderful!

#asoiaf meta#the dead ladies club#rhaella targaryen#elia martell#lyanna stark#joanna lannister#asoiaf#feminist spatial theory#lynesse hightower#lannister thoughts#gender in asoiaf#ashara dayne#cassana estermont#tysha#the princess of dorne#the unnamed princess of dorne

3K notes

·

View notes

Link

This brilliant researcher supports a theory that vindicates important Feminist Thought, but removes some hopeful biological validation of the pre-adolescent Transgender rationale! And she is totally correct, there IS No Gendered Brain! - Phroyd