#ca. 1510-1520

Video

Unidentified Netherlandish artist, Christ Carrying the Cross, ca. 1510-1520, Oil on wood panel, 11/21/23 #legionofhonor by Sharon Mollerus

#fine art#Legion of Honor Museum#Oil on wood panel#Christ Carrying the Cross#ca. 1510-1520#Unidentified Netherlandish artist#San Francisco#CA#flickr

0 notes

Photo

Albrecht Dürer, Eight Studies of Wild Flowers. Watercolor, ca. 1510-1520

768 notes

·

View notes

Text

⚜️ Cuirass and Tassets (Torso and Hip Defense), ca. 1510–1520

Medium: Steel, leather

Dimensions:

Height - 105.4 cm

Weight - 8845 g

Armorer: Attributed to Kolman Helmschmid (German, Augsburg 1471–1532)

Decorator: Etching attributed to Daniel Hopfer (German, Kaufbeuren 1471–1536)

⠀

The decoration of this armor is an outstanding example of German figural etching. The etching has been attributed to Daniel Hopfer, a noted printmaker and armor etcher. Hopfer may have pioneered the technique of making prints from an etched metal plate, which revolutionized printmaking in the sixteenth century.

⠀

The figures on the breastplate depict major Christian saints and include the Virgin and Child flanked by Saint George and Saint Christopher. On the backplate, Saint Anne with the Virgin and Child is flanked by Saint James the Great and Saint Sebastian. The figure of Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows is copied from a woodcut made about 1507 by Hans Baldung Grien (1484 or 1485–1544).

🏛️ The Met

- -

⚜️ Кираса и тассеты (защита туловища и бедер), около 1510–1520 г.

Материалы: сталь, кожа

Размеры:

Высота - 105,4 см

Вес - 8845 г

Изготовление приписывается Коломану Кольману (Кольман Хельмшмид), Аугсбург (1471–1532)

Декораторативные элементы приписываются Даниэлю Хопферу (Кауфбойрен, 1471–1536)

⠀

Украшение этого доспеха является выдающимся образцом немецкого фигурного травления. Травлёный рисунок приписывается Даниэлю Хопферу, известному граверу и декоратору доспехов. Хопфер, возможно, был основоположником в технике изготовления отпечатков с травленой металлической пластины, которая произвела революцию в гравюре в XVI в.

⠀

Фигуры на нагруднике изображают главных христианских святых, в том числе Деву Марию с младенцем в окружении святых Георгия и Христофора. На оборотной стороне изображена Святая Анна с Девой Марией и младенцем по бокам от святого Иакова Великого и святого Себастьяна. Фигура святого Себастьяна, пронзенного стрелами, скопирована с гравюры на дереве, выполненной около 1507 года Хансом Бальдунгом Грином (1484/1485-1544).

🏛️ Метрополитен-музей, США

⠀

#armour #medievalarmour #armsandarmor #history #Cuirass #Tassets #Etching #Кираса #травление #тассеты #armor

#medieval#средневековье#middleages#history#armor#armours#история#harnisch#armadura#armour#cuirass#tassels#etching#травление#кираса#доспехи

86 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A stunning Cuirass attributed to Kolman Helmschmid with etching by Daniel Hopfer,

Height: 41.5 in/105.4 cm

Weight: 19.5 lbs/8845 g

Augsburg, Germany, ca. 1510-1520, housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

#armor#armour#cuirass#europe#european#germany#german#augsburg#hre#holy roman empire#renaissance#themet#metmusuem#art#history

507 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christ between the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, by Jan Gossaert, Flemish, ca. 1510-1520

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

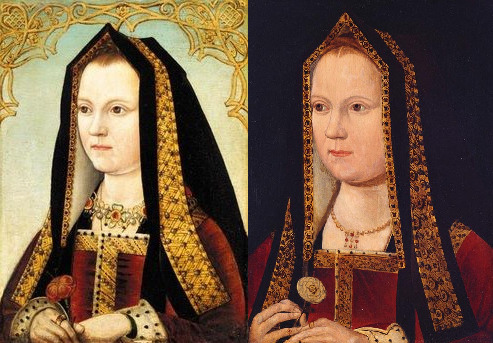

Meynnart Wewyck’s workshop-part 1-proven paintings

Meynnart Wewyck has for long been hidden in shadow of Hans Holbein the Younger. Everybody knows Holbein’s work, but very few of us know of Meynnart’s work. Even though he was working for Tudors in between 1502-1525. For 23 years! Holbein only for 11 years had royal patronage.

So how come we only have 6 confirmed portraits by Meynnart Wewyck?

It’s complicated. Because most likely Wewyck didn’t work alone. He probably was a master overlooking workshop of artists(painters)-yet only he would be on royal records as the one who would be paid. Work of same workshop can be difficult to identify as painters could come and go(or be sick when certain stage of painting needed to be finished) the resulting work from same workshop could be very different. Their skillset varied, the brushstrokes varried. Depending on turnover of painters-this can be nightmare to try to identify.

Even with all the perks of modern technology. And in case of Meynnart Wewyck’s work, it might be even more complicated. Because yes, dendrology(testing of the wood to determine painting’s age) is helpful, but might not be a deal-breaker when it comes to workshops. Which will sound crazy at first, as you’ll read this, so read entire thing.

Currently I know of 6 paintings which are identified as Meynnart’s work-and experts have no doubt about it.

1.Posthumous portrait of Lady Margaret Beaufort, comissioned in c.1510,

180 x 122 cm , location: the Master's Lodge, St John’s College, Cambridge, UK

2.Portrait of Henry VII, 38 x24.5 cm, location: Society of Antiquaries of London: Burlighton House, UK

3.Portrait of Henry VIII, location: Denver Art Museum, USA, supposedly ca. 1509

4.Portrait of Henry VIII, 44,5 x 29,8 cm location: Anglesey Abbey(National Trust Collection), UK. Supposedly ca 1515 - 1520

5.Portrait of Henry VIII, location: Private collection, supposedly ca 1519

6. Portrait of Henry VIII, location: Private collection, supposedly ca 1513

Why did I put number 4 there twice and crossed one? Because the Henry VIII we look at is not the original. There is painting beneath(which I presume to be Henry too):

How could they then possibly know this one is by same artists? Well, the cloth of gold has same pattern as in 5 and 6-but imo they didn’t come to that conclusion based upon painting we can see. But due to exhamining all of the painting, not just visual exterior.

Bit of background on the research done by professionals, which I aplaud:

Before 2019, no painting was 100% identified as by Meynnart. Then research into lady Margaret’s painting(1) has been proven to be an original work by Wewyck. They also found evidence that it belonged to John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester and probably never was in hands of Henry VIII.

(So presumably he had some other painting of her, perhaps the 1506 one.)

We can contribute this confirmation to art historians Dr Charlotte Bolland of the National Gallery, London and Dr Andrew Chen of St John's College, Cambridge.

They published their research in the April 2019 issue of Burlighton Magazine. Based on their work with the portrait of Lady Margaret Beaufort, they also attributed a stylistically and structurally similar portrait of one portrait of Henry VII(2) to Wewyck.

Based upon identifying this one, very quicky, still in 2019, a group of specialists from the Yale Center for British Art, with support from the National Portrait Gallery, London and the Hamilton Kerr Institute Cambridge, initiated a research project at the Denvert Art Museum. (Lots of different institutions doing combined research.)

They found 5 paintings painted on wood from same tree. Henry VII(2) and 4 portraits of Henry VIII (3,4,5,6) were painted on that wood.

And according to some sources also they laso identified 2 portraits of Elizabeth of York. While they studied it, and it was part of their project. But ‘being fairly certain’ they are tributable to Wewyck’ is not same as being certain.

What is madening to me, is that I went to websites of all those institutions, searched on interenet for weeks-and yet I cannot find any detailed report about this 2nd project! I have no real idea what they found! I give up. I can’t find it.

Just know only few tidbits about number 4 and then I found out on Denvert Art Museum short article-which deals with few more tidbits. But that is it. And it irritates me to no end that I don’t have more about this!

I’d really love to know what the actual findings were.

It took me ages to even find out which paintings they meant(those in private collections-those were the problem). After going through several articles and ending up empty handed each time(about those in private collection), eventually I found them on this webpage:

https://web.archive.org/web/20200603202704/http://damscout.squarespace.com/comparisons The link for it was actually on wikipedia the whole time!

And I know they found way more. I know it. There are at least 6 different methods they use! Here they are:

DENDROCHRONOLOGY & PANEL EXAMINATION

Deals with exhamining the wood of frame or wooden pannel painting is painted upon. Not all paintings are done on wooden pannels, some are on canvases only, and you can only hope the frame is original.

PIGMENT AND MEDIA ANALYSIS

This is very important because certain painters could always use same pigment mixture or varnish mixture, or glue etc. Or pigments in painting have changed colour, and you need to prove it.

MICROSCOPIC EXAMINATION

This is crucial in order to know artist technique and to determine if it is by same hand. Very HD image can be also be used for it(I use them as amateur). It’s especially great to use if you have two paintings and wish to compare how the painter did the details.

The other 3 methods all deal with allowing us to see beneath the layers of the paint. Like different filters:

INFRA-RED REFLECTOGRAPHY

Particularly good to see the original sketches/drawing-which is likely to be done from life. (and hence to realise if painting wasn’t altered)

X-RAY EXAMINATION

Tbh, I don’t really understand in what way it is different from Infra-red, other that than you can see different layer. It just reveals some details better.

ULTRA VIOLET EXAMINATION

Another method to see what we can’t with naked eye. This one I know what it is for-it reveals overpaint on the painting. Even minor retouching can be seen with this.

Denvert Art Museum on September 1st 2019, posted a short article and it, it credits the people, who did this expert analysis:

Ian Tyers, dendrochronologist, who undertook the dendro on the five linked portraits;

Pam Skiles, senior paintings conservator at the DAM, who facilitated the examination and did the initial infrared examination;

Natalie Feinberg Lopez, architectural conservator, who was contracted in to do the XRF analysis;

Kathleen Stuart, former Berger Collection curator,

and then the author of the article: Christine Slottved Kimbriel, Paintings conservator (of Cambridge University’s Hamilton Kerr Institute in the United Kingdom).

She mentions in the article exhamining the picture under the microscope, analyzying the paint using a technique called x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and taking tiny paint samples for chemical analysis back in the lab in Cambridge.

And also, working together with an imaging specialist using infrared reflectography to reveal images of what lay beneath the top paint layer.

All methods are nice, but here is what they found. Denvert Art Museum’s portrait of Henry VIII originally had blue background. And it wasn’t only painting in that project, where blue background was revealed. 3/4 had it. Which? Idk. They exhamined 1 of Henry VII and 3 of Henry VIII in Denvert Art Museum. I can only be sure of number 3. Out of 5 paintings, 1 had blue background, 4 had green-and of those 3 turned out to be originally blue.

Furthermore they found traces of gold and paint frame of number 3, which made them believe originally its frame and edge was once decorated as number 2 was:

with golden motive above above the sitter, and red trim and green-and-white striped “barber’s pole” trim:

But back to dendrology. So, numbers 2-6 are all done on wooden pannels cut from same tree. 5 paintings painted on wood of same baltic oak, which was felled between 1500-1515. Which gives us date cca 1500-1520, when these were used-according to proffesionals.

(It is presumed that is when they should be used. Imo it should be stretched to 1500-1525 at least.)

Lady Margaret’s posthumous portrait is made out of wood of two baltic oaks(different ones than the remaining 5 paintings), and testing shows one oak was felled after c.1487 and the other after c.1489. So timeframe for these two oaks to be cut and used is ca 1490-1510.

So it is possible that oak was cut 10 or even 20 years before it was used.

Why would they wait so long before using it? Excellent question.

I believe I might know the answer. I heard of practise certain monasteries allegedly did. They would leave cut tree trunks intended to be used for roofs in forest for several years. If nothing touched them(no bug started to eat it, etc.) until certain time was over, then they’d use the wood. Because then it was way less likely that any woodworm would attack the wood later on. Hence insuring the quality. Such wood would last.

If the painters also prefered older untouched wood, it’d explain it. They’d buy one such tree trunk(or part of it) from reliable source and then use it all, over course of many years.

So the dendrology analysis is helpful, in letting us know the paintings are early 16th century works and very likely same workshop, but there is a big issue.

Except lady Margaret’s portrait-where we know portrait’s history, we cannot be sure if the painting is original or very early copy.

Even knowing that some portraits originally had blue background(number 6 still does), and green damask background is alteration in some of them-the traces of blue found, are not conclusive proof that it is an original painting from life.

Because we have portrait of clearly young adult Henry VIII(number 6) with this blue background-suggesting it was still popular at least in 1st half of 1510s.

(Then in mid 1510s in my opinion green damask background took on and continued to be popular up to late 1520s(for half-lenght portraits, miniatures from mid 1520s have ultramarine blue backgrounds).)

If for example young King Henry decided in 1510 to have posthumous portrait of his father made(and we know Henry VIII loved to have posthumous portraits of his relatives), it’d still have the blue background. Dendrology would still fit, the artist/workshop would be the same. If this is the case-how on earth as an expert do you determine if it is an original? I don’t see how. Unless there is some alteration in costume or if you have some proof that artist(s) in this timeframe did something differently.

But for that you’d need to identify a more of paintings by this workshop.

But we’re long way from that still. But we know Wewyck’s workshop certainly made more paintings, that is clear from records. He appears in them as Dutchman, Flemish or Netherlandish-a region known for its artists.

There was no universal spelling back then, so there is at least 15 different ways his name was spelled like, and in Scottland he was even refered to as an English painter called Mynour, instead of a painter in service of English King.

Scotland is actually where he starts in records. In September 1502, Meynnart Wewyck delivered 4 paintings to King James IV of Scotland.

Those paintings were of King Henry VII, Queen Elizabeth of York, Princess Margaret(James’ bethrohed) and Prince Harry(future Henry VIII).

Why no prince Arthur? Because he died in April that year.

Why no princess Mary(Future Queen of France)? Because she was child of 6 and of no importance to Scottish King, unlike Margaret or young Harry.

So prior to September 1502, Wewyck was already in service of English royals.

He then appears to have stayed in Scotland up to November 1503.

Records show he made portraits of James and his bride in 1503.

He might have also done portrait of James IV located in Abbotsford House in Scotland(it is atributed to him, but as far as I know it is not confirmed), dated as 1502: (although on painting it looks more like 1507-but that might be alterated date, or added date)

It is also suggested that portrait of James IV in inventary of Henry VIII was also made by Wewyck in between 1502-1503. But few portraits of James survive and we have mostly just drawings or engravings of them.

Do we have any clue how those lost Scottish paintings looked like? Maybe.

It’s likely that sketch of Margaret Tudor in Receuil d'Arras, a collection of portraits copied by Jacques de Boucq, done cca 1570, is based upon one of the two paintings of Margaret by Meynnart Wewyck:

(And yes, this commonly mislabelled as drawn from life)

The same collection of drawings also consist sketch of James IV(on left) and of his son Alexander Steward(on right)- Both could have been done by Wewyck. If those are who the text beneath drawing says they are.

Later, in March 1505 Henry VII paid Mennart Wewyck £1 for pictures(paintings).

(we don’t know which, if it was for past work or for future work. For example painter Sittow was not paid for works commissioned by Queen Isabella of Castile many years after she died.)

Wewyck also made 2 portraits of lady Margaret Beaufort.

1st was comissioned in 1506-presumably from life, 2nd posthumous was comissioned around 1510(that is our number 1).

He also made drawings/sketches then used by sculptor Pietro Torrigiano who made lady Margaret’s tomb.

But even though he was on royal payroll still in 1525(then he presumably died), as far as I know, we don’t know about which other paintings he made in between 1510-1525.

(Perhaps somebody can recommend a source which would give us a clue.)

Let’s look at his proven work again:

1)Posthumous portrait of Lady Margaret Beaufort, the Master's Lodge, St John’s College, Cambridge(UK):

It’s huge! (no wonder it was refered to as a table) And sadly the painting doesn’t look exactly as it used to when it was made. It suffered localised paint loss, particularly in the lower-left corner, and is also partly obscured by discoloured varnish and retouchings. Further more, the face when being made was bit off, and painter moved it about an inch(this happens a lot, sometimes you sketch it all-come to get snack and return and realise it is iffy!) Normally, you’d not see that painter did this. But sadly, due to thinning of layers you can. You see lady Margaret’s nose twice.

So if you wish to know how originally those parts of painting looked like, I recommend looking at a copy by Rowland Lockey, commissioned in 1598 (it’s also in St. John’s Colledge, University of Cambridge):

it’s really great copy(unlike so many copies of Tudor paintings)

2)Portrait of Henry VII in Society of Antiquaries of London:Burlighton House(UK):

3)Portrait of Henry VIII, Denver Art Museum(USA):

4)Potrait of Henry VIII Anglesey Abbey(National Trust Collection), (UK):

Once again, this is actually not the original portrait. Beneath the layers of the paint is another portrait of Henry VIII(or at least it seems like him to me)

Sadly I am still searching for bigger picture which would show the painting beneath it.

5)Portrait of Henry VIII , Private collection:

6)Portrait of Henry VIII, Private collection:

As for Elizabeth of York, they were looking at these two portraits of her:

Queen Elizabeth of York, about 1470–98. Royal Collection Trust, Haunted Gallery, Hampton Court Palace( UK):

38.7 cm x 27.8 cm

Queen Elizabeth of York, about 1500(supposedly). Bryan Collection, Crab Tree(supposedly- I couldn’t find it):

And imo they are not drawn from life. But are very early copies. Very early indeed. Maybe even 1510s or 1520s. Because they have turned frontlets-just as on her tomb. Due to fabric upon hood being black(only paste is white), this details is so hard to spot-that it is unlikely it could have been copied when artist no longer knew how it was supposed to look like.

But what exactly made them believe in first place that these might be by same artist/same workshop? The artistic similiarities-are kind of vague term. Sadly, I couldn’t find what exactly they mean. It’s not written down in April 2019 article, and as I said nor could I find detailed report about the fallowing research. Just tidbits

However, if you just look at those paintings in HD(or at good photos), even as amateur you can spot some the similiarities. So which are they? Imo:

1)the fur

number 2(on left) and number (3)-shading of it suggests same hand

Problem is, different kinds of fur would require different shading and hence it could be hard to spot.

2)the cloth of gold pattern. You might think King could have cloth of with this pattern-and be painted by several different artists-and they’ve still end up same. Not entirely true.

Idk if you ever attended drawing lessons. I have and one of the exercises we were to do-was to draw picture of certain actor based upon his photography. And each person’s same actor-came out completely different.

Of course trained painter, with good eye, might be able to do very good copy, and few even copy as good as the original. But usually that is not the case.

Each person does it bit differently even if they try not to. So it should be recognizeable feature. But it is isn’t in many cases-because they weren’t just painting the area. In most cases these painting were gilded. And sometimes re-gilded later on.

And way too often the re-gilding was done poorly, destroying the original pattern beneath and skill of previous artists hence doesn’t show. Details are often gilded over!

I am 90% sure that brooch(above) on Henry VII’s hat on number 2 is same as on multiple painting(including number 6), all of which have it with red stone:

On Henry VIII, which grew to bigger than his father, it looks tiny! But it’s very likely same brooch.

Also, rather often silver or golden gilding comes off(that is why so often it gets re-gilded), revealing just the basic under layer made in beige or yellowish colour.

And only traces of gold(which in same cases disappeared completely) are later found during proffesional exhaminations.

Why not every painting has issues like that? Due to different conditions painting is kept in=(enviroment vs glue), and due to different people taking care of them.

3)thinning of layers

Not all paintings must have this necessarly(different envirement might or might not make this occur). But certain painters’ work tend to to have the same issues more often. It might not be so obvious all the time as with potrait of lady Margaret. But number 5 has lines under eyes and sketches of brows which shouldn’t be visible.

So thinning of layer might suggest it is same artist. But also it can also mean master and apprentice, or same workshop. It’s definitely no proof by itself.

4)the fabric-how it is painted. In most of these recognizably it is crimson velvet. And while one time(number 5) it doesn’t have the vivid colour(probably because somebody else made the mixed the pigments), the style of this velvet is same or very similar. It could be same workshop, in several cases even same painter.

(I think it is possible that some people within workshop specialized in painting just 1 part of portrait-just fur, just velvet, just golden details, just the face. While in non-royal commissions(or not high status) perhaps 1 painter would be allowed to do even entire painting, I think for the high status, they’d really combine their skills for the best result.)

5)The other details-pearls, jewelry, hair, flowers etc.

Each of these can be as big as clue, as any of the much larger things.

Here very notable are the roses on number 2 and 3(again):

-that is by same hand for sure

if you look at neck of men in 2 and 3, you can also notice the same v-like shape.

That imo is not just painter’s skill showing-but hereditary feature between father and son(a detail which copies usually don’t bother to copy). Imo it’s this:

According to anatomy sketches on google-in that area should be jagular notch(the dip) between clavicles(which are to the sides and not forming that v) and then sternal head( sternocleidomastoid muscle).

So if the outfit allows you to see young Henry VIII’s neck in full, it might be there.

But number 5 already doesn’t have even hint of it and overall the visible differenes between the two are big. Yet experts say it is same by Wewyck(or his workshop):

And imo it’s indeed possible. The jewelry and gilded patterns are done in same way. The velvet too-but clearly somebody new mixed the pigment for the crimson-and it eventually faded away, and didn’t stay vivid as in other paintings.

But it’s just same workshop in different time.(and that is why you need experts to have look at those paintings and say-yeah this was also crimson, the drawing beneath is done in same way, etc. etc.)

Another detail are the male hats-often done in black, which hides the details actually), the type and size of hat can be helpful in dating the piece.

But rather often somebody tried to ‘correct’ the hat. It’s one of the most altered things on male portraits(imo). Very likely these portraits originally(3,6) showed same type of hat:

their hands also are folded in alost exact same way, and they sit same way.

Different roses suggest some time passed between their paintings, and noses do too(yes, in one he could be teen and in other adult), but their philtrum(that part above lip under nose), the chin, very likely at least sketched by same original painter, if the skin was not done by him too.

6)background

By now we know that very early work by Meynnart Wewyck(’s workshop) originally had blue background-very likely like this-blue fading into white, in lower part:

It reminds me of blue sky on nice summer day. Recently we had a lot of such days near my home, and especially when seeing the fields with grain growing and harvest aproching, several times I had thought-ideal day for grain harvest.

And in Tudor times, grain was staple of the diet, and good weather throughout the year and for the harvest would be crucial. So imo this kind of background symbolizes prosperity, good days, brought by the Tudor dynasty.

And the golden details at top of painting are also part of that background. But such background on its own is not enough of proof, it just helps to date the painting-because at certain times such background was popular and later it was not. Same goes with damask background. Such fabrics could spread around Europe and appear in paintings by multiple workshops. By its own, they are not a proof of same workshop. In Netherlands that’d be impossible to tell which imo. But in England, where there weren’t that many painters, it could help. If nothing else to pinpoint aproximate date when fabric with this pattern was fashionable(based upon other paintings featuring it elsewhere in Europe).

So imo both types of these backgrounds can actually be interesting detail to look out for.

However when it comes to damask backrgound, since most don’t survive in original nor good condition, finding two paintings with exact match can be extremely difficult. But not impossible.

But what I’d recommend against using as conclusive proof-is the skin.

Certain aspects of it such as thinning of it and shading, yes you can use that. But I know for sure that paintings of same person even if painted in exact same time by 1 same artist, if kept in different conditions/different envirement-the skin can look drastically different. Really different. Skin is not realiable proof, ok?

So can we find based upon these details more work of Meynnart Wewyck’s workshop? Well, not conclusively, we cannot prove it! Because the expert analysis and exhamination of the paintings would be also necessarly.

But we can find some where we see the same details as which I just listed above. So in part 2 I’ll show you some of those and my other picks for ‘possibly by Wewyck’s workshop’ and reasons why I believe experts should take look at them.

I hope you’ve enjoyed it.

#long post#historical portraits#meynnart wewyck#tudors#Lady Margaret Beaufort#henry viii#henry vii#henry vii of england#elizabeth of york

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

al things considered — when i post my masterpiece #1127

first posted in facebook october 29, 2022

giorgione -- "sleeping venus" (ca. 1520)

"he was one of the greatest of all venetian artists, but who was giorgione?" ... john-paul stonard

"the painting, one of the last works by giorgione (if it is), portrays a nude woman whose profile seems to echo the rolling contours of the hills in the background. it is the first known reclining nude in western painting" ... wikipedia

"scarcely five paintings can be ascribed with absolute certainty to [giorgione's] hand. yet these suffice to secure him a fame nearly as great as that of the great leaders of the new [venetian] movement" ... ernst gombrich

"the 'sleeping venus' [...] is a painting traditionally attributed to the italian renaissance painter giorgione, although it has long been usually thought that titian completed it after giorgione's death in 1510. the landscape and sky are generally accepted to be mainly by titian. in the 21st century, much scholarly opinion has shifted further, to see the nude figure of venus as also painted by titian, leaving giorgione's contribution uncertain" ... wikipedia

"he seems more of a myth than a man. no poet on earth has a destiny to compare with his. almost nothing is known of him, some people even doubt his very existence [...] yet all the art of venice seems inflamed by his revelation" ... gabriele d'annunzio

"giorgione MUST have had a helluva public relations agent, no?" ... al janik

#giorgione#sleeping venus#wikipedia#john-paul stonard#venetian artists#first known reclining nude#western painting#ernst gombrich#attribution#titian#gabriele d'annunzio#more of a myth than a man#public relations agent#al things considered

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Satyrca. 1510–ca. 1520

Antico (Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi) Italian

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 537

Half man and half goat, satyrs are hybrid creatures of Greco-Roman myth that often appear in Renaissance art as hoary, lustful denizens of the wild forests—fierce primordial beings symbolizing the raw forces of nature.[1] Yet satyrs could also personify humanity’s natural, instinctual state;[2] and in this guise, they take on an aura of beauty that evokes an elegiac longing for lost innocence. Such is the mood conveyed by this remarkable statuette, in which a satyr crowned with grape vines is depicted as a handsome youthful creature utterly absorbed in playing a thin flute. The strong goatish legs firmly support the human torso, and the joining of thighs to loins and buttocks is left hairless to reveal the seamless muscular transition from goat to man.

Source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/206996

0 notes

Text

Women painters from the seventeenth century and before

I have compiled a small, incomplete list of women painters, working mainly in Europe, who were born before the year 1700. You can find works by all of them by searching for them on my blog or by looking through my early women artists tag. Alternatively, here is a post featuring self-portraits by some of them.

Artemisia wasn’t the only one. We have always been here.

Lucia Anguissola (Italian, 1536 or 1538 - c. 1565, before 1568)

Sofonisba Anguissola (Italian, c. 1532 - 1625)

Mary Beale (English, 1633 - 1699)

Marie Blancour (French, 17th century)

Cornelia toe Boecop (Dutch, 1551 - 1629)

Mechteld toe Boecop (Dutch, c. 1520 - 1598)

Alijda Boelens (Dutch, 1557 - 1630)

Gesina ter Borch (Dutch, 1633 - 1690)

Madeleine Boullogne (French, 1646 - 1710)

Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Italian, 1482 - 1548)

Margherita Caffi (Italian, 1650 - 1710)

Ginevra Cantofoli (Italian, 1608 - 1672)

Joan Carlile (English, ca. 1606 - 1679)

Elizabeth Dormer, Countess of Carnarvon (English, 1633 - 1678)

Rosalba Carriera (Italian, 1675 - 1757)

Elisabeth-Sophie Chéron (French, 1648 - 1711)

Maria Giovanna Clementi (La Clementina, Italian, c. 1692 - 1761)

Suzanne de Court (French, active ca. 1600)

Anna Folkema (Dutch, 1695 - 1768)

Lavinia Fontana (Italian, 1552 - 1614)

Fede Galizia (Italian, 1578 - 1630)

Giovanna Garzoni (Italian, 1600 - 1670)

Artemisia Gentileschi (Italian, 1593 - c. 1656)

Maria de Grebber (Dutch, 1602 - 1680)

Guda (German, 12th century)

Margareta de Heer (Dutch, c. 1600 - before 1665)

Catharina van Hemessen (Flemish, 1528 - ca. 1587)

Johanna Helena Herolt (Johanna Helena Graff) (German, 1668 - 1723)

Sarah Hoadly (English, 1676 - 1743)

Louise Hollandine of the Palatinate (German, 1622 - 1709)

Antonina Houbraken (Dutch, 1686 - 1736)

Anna Maria Janssens (Belgian, before 1620 - after 1668)

Henrietta Johnston (American, c. 1674 - 1729)

Gisela von Kerzenbroeck (German, 13th century)

Ann Killigrew (English, 1660 - 1685)

Katherina Van Knibbergen (Dutch, 17th century)

Anna Maria de Koker (Dutch, 1640 - 1698)

Giulia Lama (Italian, c. 1685 - after 1753)

Herrad of Landsberg (Alsatian, c. 1130 - 1195)

Judith Leyster (Dutch, 1609 - 1660)

Barbara Longhi (Italian, 1552 - 1638)

Elisabetta Marchioni (Italian, active 17th century)

Diana De Rosa, called Annella di Massimo (Italian, 1601 - 1634)

Maria Sibylla Merian (German, 1647 - 1717)

Princess Mitsuko (Gen’yo) (Japanese, 1634 - 1727)

Louise Moillon (French, 1610 - 1696)

Maria Monninckx (Dutch, 1673 or 1676 - 1757)

Jacoba Maria Nickele (Dutch, c. 1690 - 1749)

Plautilla Nelli (Italian, 1524 - 1588)

Josefa de Óbidos (Portuguese, 1630 - 1684)

Maria van Oosterwijck (Dutch, 1630 - 1693)

Arcangela Paladini (Italian, 1596 - 1622)

Geronima Cagnaccia Parasole (Italian, c. 1569 - 1622)

Magdalena van de Passe (Dutch, c. 1600 - 1638)

Catharina Peeters (Dutch, 1615 - 1676)

Clara Peeters (Flemish, 1584 - 1657)

Angela Maria Pittetti (Italian, 1690 - 1763)

Elena Recco (Italian, active 17th - 18th century)

Cornelia de Rijck (or de Ryck, Dutch, 1653 - 1726)

Marietta Robusti (Italian, c. 1550 - c. 1590)

Geertruydt Roghman (Dutch, 1625 - 1657)

Anna Elisabeth Ruysch (Dutch, 1666 - after 1741)

Rachel Ruysch (Dutch, 1664 - 1750)

Maria Schalcken (Dutch, 1645 - 1699)

Anna Maria van Schurman (Dutch, 1607 - 1678)

Elisabetta Sirani (Italian, 1638 - 1665)

Levina Teerlinc (Flemish, c. 1510-1520 - 1576)

Maria Verelst (English, 1680 - 1744)

Johanna Vergouwen (Flemish, 1630 - 1714)

Charlotte Vignon (French, before 1639 - after 1685)

Anna Waser (Swiss, 1678 - 1714)

Michaelina Wautier (or Woutier, Woutiers, Belgian, d. 1689)

Alida Withoos (Dutch, 1670 - 1715)

Aleida Wolfsen (Dutch, 1648 - after 1692)

Margaretha Wulfraet (Dutch, 1678 - 1760)

Kiyohara Yukinobu (Japanese, 1643 - 1682)

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

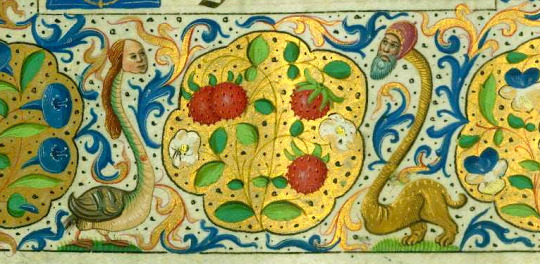

Almugavar Hours (1510 - 1520 ca), The Walters Art Museum.

#Almugavar Hours#medieval art#renassaince art#1500 art#liturgies#religious art#drollery#drolleries#illustration#early modern art#details#art details#hours#dragons#boy riding a snail#angels#animals with human heads#drawings#funny drawings#I really hope compression doesn't ruin the quality#so basically this book is a list of medieval chantries#but it is also illustrated#and it sent me on a rabbit hole of paleography#I found one of its illustration in#How to live like a Monk#Because I wanted to study late medieval history some days ago

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tannhäuser in the Venusberg by Henri Fantin-Latour 1836-1904. Made in 1864. Title: Tannhäuser on the Venusberg. Height: 118.1 cm (46.5 in); Width: 151.1 cm (59.5 in). Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

"The narrative of La Sale's ballad becomes conflated with the name of Tannhäuser in German folklore of the early 16th century. A German Tannhauser folk ballad is recorded in numerous versions beginning around 1510, both in High German and Low German variants. Folkloristic versions were still collected from oral tradition in the early-to-mid 20th century, especially in the Alpine region (a Styrian variant with the name Waldhauser was collected in 1924). Early written transmission around the 1520s was by the means of printed single sheets popular at the time, with examples known from Augsburg, Leipzig, Straubing, Vienna, and Wolfenbüttel. The earliest extant version is from Jörg Dürnhofers Liederbuch, printed by Gutknecht of Nuremberg in ca. 1515. This Lied von dem Danheüser explores the life of the legendary knight Tannhauser, who spent a year at the mountain worshiping Venus and returned there after believing that he had been denied forgiveness for his sins by Pope Urban IV. The Nuremberg version also identifies Venusberg with the Hörselberg hill chain near Eisenach in Thuringia, although other versions identify other geographical locations, as for instance in Swabia, near Waldsee.

The popularity of the ballad continues unabated well into the 17th century. Versions are recorded by Heinrich Kornmann (1614) and Johannes Preatorius (1668)."

-taken from Wikipedia

https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2020/05/tannhauser-in-venusberg-by-henri-fantin.html

#venus#aphrodite#freyja#germanic#pagan#europe#european art#paganism#tannhäuser#folklore#art#19th century art#museums#paintings#teutonic order#goddess#henri fantin latour

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

▪The Rothschild Lamp.

Maker: Andrea Briosco, called Riccio (Italian, Trent 1470–1532 Padua)

Date: ca. 1510–20

Culture: Italian, Padua

Medium: Bronze

238 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of a Cardinal in his Study, attributed to Lorenzo Costa, c. 1510-1520, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Paintings

70.17ter the old frame for this piece is on P65B MS; Italian wood tabernacle cassetta frame, ca. 1600 (reframed 1992), H.46-1/4 x W.44 in. The unknown sitter in this portrait, wearing the crimson cassock and cap of a cardinal, is depicted as a humanist scholar. Through the open window can be seen the figure of Saint Jerome, the 4th-century biblical scholar, often portrayed in medieval art as a kneeling hermit. He is identified by a broad-brimmed cardinal's hat and the lion that was his legendary companion. During the Renaissance, however, Saint Jerome was frequently shown as a cultured man of learning in his study—a representation this sitter clearly wished his portrait to suggest. The identities of both artist and sitter have long been debated. The most persuasive evidence indicates that Lorenzo Costa painted a high-ranking prelate, possibly Cardinal Bibbiena, while court painter in Mantua, a sophisticated center of humanist culture.

Size: 32 1/4 x 30 in. (81.92 x 76.2 cm) (panel)

Medium: Oil and tempera on poplar panel

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1784/

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

School of Raphael

1483-1520

Italy, ca. 1510.

Morgan Library

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tree of Jesse by Master of James IV of Scotland, Flemish, ca. 1510-1520

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A composite Maximilian harness with some modern parts,

Height: 66.1 in/168 cm

Germany, ca. 1510-1520, from Hermann Historica.

#armor#armour#composite#maximilian#europe#european#germany#german#hre#holy roman empire#renaissance#hermann historica#art#history

239 notes

·

View notes