#and she’s 72% certain it was Jessica that told him about it

Note

you have such amazing art! I love the way you draw Jennifer and Matt. Wanted to tell you that you should defiantly keep up the good work!

ꕥ| My attorney’s at law

Aw shucks — thank you! I’m flattered.

#see dove you didn’t delete the ask this time#phew lol#thanks for the ask!#and the really sweet compliment#oof these two#matt murdock#jen walters#I’m pretty sure Matt’s trying to persuade Jen to change her screen saver from being his butt#she’s like ‘nah’#and she’s 72% certain it was Jessica that told him about it#lol it was Frank#I need all my Defenders and Frank and Elektra to hang with Jen#that’s a fun group#matthew murdock#jennifer walters#daredevil#she hulk#jen x matt#matt x jen#mattjen#attorneys at law#marvel#mcu#my art#asks#my asks#you can ask me things#dovelywind#dovely draws

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cody Fern Interview for Out Nagazine

Out: What is it like to play the Antichrist?

Cody: It’s been the greatest privilege of my acting career so far. Between this and Versace, if for some reason the apocalypse came tonight, I’d be pretty happy with what I’ve done.

Out: How much did you know going into the season?

Cody: I didn’t know anything, I didn’t even know the theme, we found out when everybody else found out. We did know obviously that there had been an apocalypse, but I found out that I was playing Michael Langdon two days before we started filming. My first scene was the interrogation with Venable. All that Ryan had told me was that I’d be wearing a long, blonde wig and that I would have an affinity for capes. I went into the piece thinking I was the protagonist.

Out: Do you think that in a way, Michael is the protagonist of Apocalypse?

Cody: I think he is, but that’s from my perspective. I understand that the witches are the protagonists, particularly Cordelia. It’s in many ways a continuation of the Coven story, but running parallel is the story of how I see Michael, which is this very betrayed, broken, lost young man who finds his way into the apocalypse because of circumstance, not because of destiny.

Out: There’s a conversation of nature vs. nurture: we know from Murder House that there was evil in Michael from birth, he wouldn’t have been murdering his babysitters if there wasn't, but it’s become clear in the latter half of the season that he’s lost and is being manipulated by people with their own agendas.

Cody: We see him at 15 when he’s grown 10 years overnight, and the way that I always played Michael was that the murders are an impulse that he can’t control and he doesn’t understand. His consciousness is that of a 6-year-old boy when he’s a teenager, but he’s struggling to come to terms with his body and his desires, but he’s not fully formed. When you follow that, to me Michael’s story is a parable. There’s two ways of looking at the story of the devil: the way that people have interpreted the bible, and this polar opposite that Lucifer so loved god that he refused to bow down before men. Here we have god’s favorite angel in this kingdom of heaven, who was then made to bow down before god’s next making, and ultimately that leads to him being cast out of Heaven, and it wasn’t like Lucifer was wrong. Man then goes about destroying the earth. That’s what we’re doing right now, we’re destroying planet Earth, and it seems that there’s no remorse for it. I really leaned into that with Michael, this young boy who was cast from the kingdom of Heaven, who was cast out of the normal rigors of society, out of what people find acceptable, and then is used and abused and abandoned and broken, and what happens when you have no love in your life, where does that energy go?

Out: One of the ways I’ve been reading this season is a commentary about the state of gender politics. The warlocks essentially bring about Armageddon by attempting to topple the matriarchal power the witches have over the coven. Michael in a way is this avatar for misogyny and male entitlement. Was that intentional?

Cody: I absolutely believe that was intentional. The thing about Ryan Murphy is he’s able to weave these incredible social commentaries into this fascinating world he’s created. Certainly in this season we are looking at bringing down the patriarchy, about what happens when a matriarchal society is enforced and the hubris of men begins to take flight. It’s not dissimilar to what’s happening in society today or what has been happening for hundreds of years. Ryan certainly weaves that into his writing. The gender battle is being fought and Michael is the avatar for it but is certainly not a part of of it. He is manipulated into this gender battle but he himself is not misogynistic, but there’s certainly something to be said for the fact that he needs a very strong mother figure in his life and has mommy issues. His mother tries to kill him in the Murder House, Constance commits suicide, Cordelia takes away Mead and he has this robot who he has to program into loving him. I think he has an enormous respect for Cordelia. He needs strong women in his life, and if he just took Cordelia’s hand when she offered it, if he just overcame his insatiable thirst for revenge, he could’ve gone another way.

Out: One of the standout episodes of the season was “Return to Murder House,” what was it like to find out that not only was Jessica Lange returning but that you’d get to act opposite her?

Cody: My ovaries exploded. I can’t begin to describe to you how overwhelmed I was. The first scene I shot with Jessica was the scene where Michael finds her dead body after she’s committed suicide, and I was so excited and nervous and afraid of that scene that I spent the whole day shaking like a life. When we got to it I was so excited and overwhelmed, it was very hard for me to drop into the chaos around what I needed to go into. Sarah, who is just the most exceptional human being in the world not to mention the hardest working and the most talented, took my hand and said, “Don’t be afraid of this, you’ve got to really go there,” and then jokingly, “Imagine that at the end of this if you didn’t get it that Jessica would think you’re a bad actor.” It was terrifying! I was certainly able to move past a wall, that’s what was blocking me, I was so afraid of judgement, that wasn’t coming from Jessica of course, it was coming from myself and my own process. Working with Jessica will go down as one of my life’s greatest achievements.

Out: What was it like to not only act alongside Sarah Paulson but to be directed by her in “Return to Murder House?”

Cody: One of the greatest joys. As an actor, to step into the director’s chair, you have a certain upper hand because you understand how actors work and how to communicate with actors. Sarah very much comes from a place of absolute respect for the emotional process of the artist. First and foremost she’s looking out for you as an artist, which elicits such extraordinary performances because you have so much trust in her, so you’re willing to give her anything and everything. She’s got such a deft hand as a director, watching it was gobsmacking, and was working under the most extreme pressures imaginable. Not only was she playing Billie Dean and Cordelia in another episode in the same time as this was filming, she had to film 72 scenes. In contrast, the episode before had 32, so she was filming almost double what any other director on the series was filming, while playing two other characters in two other episodes with under one week of preparation, it was truly a feat.

Out: She certainly wears a lot of hats...speaking of which, you had a very special hat yourself. Let’s talk about that wig.

Cody: I loved that wig. If I could wear that wig on a daily basis I would. Wearing that wig was everything.

Out: How long does it take to get into the Rubber Man suit?

Cody: It takes about 20 minutes and a lot of lube, and once you’re in it you’re in it, you can’t take it off. So I was in that suit for 16 hours. I think I held the record for being in the suit the longest.

Out: Can you settle this debate: was Michael the Rubber Man suit who has sex with Gallant?

Cody: No, not physically anyway. The Rubber Man is also a demon, so when someone is wearing the suit, they become the Rubber Man, but when nobody is wearing the suit, Rubber Man — through the power of Murder House — becomes a demon, and that demon is in many aspects controlled by Langdon. Langdon uses every means at his disposal to warp and manipulate and draw out the innermost desires in a human being, he draws out their shadow self and he’s able to play with that shadow and create scenarios that tempt a person into giving into the evil inside of them. Because the Rubber Man is there and then Gallant realizes he’s killed Evie. There’s some mind games going on there in how Michael reveals Gallant’s innermost desire, which is deeply Oedipal, because we [we wonder], is he fucking his grandmother? Because the realization is that the Rubber Man is Evie and he’s just slaughtered her in his bed. There’s so many layers of darkness there. That’s certainly how I thought about it.

Out: I’m sure you can’t reveal anything about the finale tonight, but can you tease a bit about how Michael’s journey ends?

Cody: There’s something deeply beautiful and tragic about the way that the story ends for Michael. It was genuinely one of the hardest scenes that I shot in the series. The end of the series, knowing that this was going to be the last time I — I’m getting sad about it now — I loved Michael so much, the past nine days since we finished filming it have been very hard. I loved Michael so much and I wanted so much for him, I just wanted love for him. The way the series ends for Michael is very moving.

Out: Are you open to returning for another season of AHS?

Cody: Oh my god, in a heartbeat. The experience is beyond comparison. Moving forward there will hopefully be great triumphs in my career, hopefully I’ll get to play characters that are as complex and layered as Michael, but this will forever have been the most formative experience of my acting career and of my development as an artist. To work with these extraordinary women at such an early point in my career, to work with Sarah Paulson and Frances Conroy — fuck me, Frances Conroy is one of the most talented, hard working, fierce actresses. To work with Kathy Bates and Joan Collins, the list goes on and on. To be in the same room as Billy Porter, who is an American treasure. The entire experience was so exceptional and magic. I know I’ll never have that back, that moment, it’s gone. I would come back in a heartbeat.

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

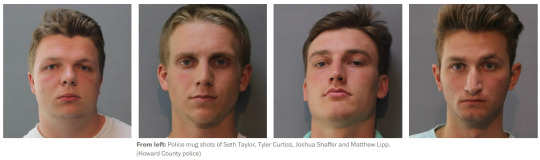

A black principal, four white teens and the ‘senior prank’ that became a hate crime

By Jessica Contrera July 9, 2019

The principal saw a swastika first. It was inky black, spray painted on a trash can just beside the entrance to the high school. David Burton switched off the engine of his SUV, unaware, even then, of the magnitude of what he was about to see.

This was the last day of the year for the class of 2018 at Glenelg High School. There was going to be an awards ceremony, a picnic, that end-of-a-journey feeling that always made Burton so proud of his job. But as he was on his way to work at 6:25 a.m., the assistant principal had called, agitated and yelling about graffiti. “It’s everywhere,” he kept saying, so Burton had leaned on the gas and rushed the last few miles.

Soon, everyone would be telling him how shocked they were. This was Howard County, after all: a Maryland suburb between Washington and Baltimore that is extremely diverse, extremely well-educated and home to Columbia, a planned community founded on the principles of integration and inclusion. People moved their families here for that reputation just as much as for the good schools.

“Pleasantville,” Burton liked to call it, but as a black man, and as the principal of the county’s only majority-white school, he knew this place was more complicated. When he stepped out into the bright spring day, he confronted the reality of just how much more.

Beneath his dress shoes, there were more swastikas. Spray painted around them were crude drawings of penises.

Then Burton saw the letters “KKK.” He saw the word “Fuck” again and again next to the words “Jews,” “Fags,” “Nigs” and “Burton.”

He kept walking, following the graffiti around the building’s perimeter. It was on the sidewalks, the trash cans, the loading dock, the stadium around back. There were more than 100 markings in total, though he didn’t bother to count.

He turned a corner and saw something written in large capital letters on the sidewalk: “BURTON IS A NIGGER.”

He paused only for a moment, looking at the words, trying to comprehend that all of this was real.

Later, school district officials, county administrators and prosecutors would have a name for what happened here. They would repeat it, condemn it and vow to prevent it from occurring again. Hate crime.

The phrase has become inescapable as hate-fueled incidents have spiked across the country. A quarter of all hate crimes reported to the FBI, more than any other category, are similar to the attack discovered at Glenelg on May 24, 2018. Vandalism and destruction of property, a physical marking of an age-old threat: You don’t belong here.

The majority are repaired, washed away or painted over without anyone arrested. When the perpetrators are caught, they are rarely charged with a hate crime. Here, there would be consequences, and with them, a division between those who wanted to confront the racism in their midst and those determined to explain it away.

But first, Burton, 50 years old and dressed in one of his best black suits, would walk back over the graffiti, retreat into his office, close the door and pray.

His staff scrambled to cover the spray paint with tarps, carpet pads, anything they could find. The maintenance team searched for a sandblaster. But there was too much to cover and too little time before the students and parents began arriving. The seniors were wearing red caps and gowns, ready for their awards ceremony. Everyone was directed to alternative entrances, away from the worst of the damage. But photos of the graffiti were already being texted, emailed and Snapchatted.

In the auditorium, Imani Nokuri looked for her family, who had come to see her perform the national anthem. She was one of fewer than 20 black students in the class of more than 260 seniors. She and her younger sister, a freshman at Glenelg, had been rapid-fire texting all morning, comforting each other. But when Imani saw the look of deep concern her grandmother gave her, she forced a smile onto her face. “It’s okay,” she promised. “I’m fine.”

In the central office, teachers who had led diversity and empathy training for students were crying. Police were arriving, asking to see security footage. Phones were ringing with calls from reporters. Photos of the damage were about to be broadcast on TV, making their way into homes across the region.

In one of those homes, 72-year-old Susan Sands-Joseph was watching. She knew Glenelg well. She was one of the first black students to attend the school after desegregation. Suddenly, all the memories that she tried not to dwell on were dredged up again: the words she was called, the tomatoes thrown at her head, the looks her parents gave her when she came home saying scalding hot soup had been pushed into her lap again. “It’s okay,” she had promised them. “I’m fine.”

By the time the awards ceremony was about to begin, Principal Burton had rewritten the speech he had been planning to give. “We are not going to let this ruin your celebration,” he would now tell students.

He emerged from his office with notes clutched in his hand and stopped to check in with the police. The security footage, they told Burton, confirmed what he had suspected.

The principal entered the auditorium to a burst of applause. He stepped up to the podium. He stood before his students, looked out into their faces and felt certain: The people who did this were looking back at him.

Seth Taylor tipped his head down so his graduation cap would block his view of the podium. It felt, he said later, like the principal was staring right at him. But he and the others hadhidden their faces behind masks the night before, Seth reminded himself. How could anyone know they were the ones who had done it?All morning, he had been replaying the vandalism in his mind. He’d been at his buddy Matt Lipp’s house, where the parents of all their friends had gathered the evening of May 23 to sort out the details of Senior Week. The teens’ parents had rented them a house in Ocean City, the annual destination for thousands of local students celebrating graduation, and were divvying up tasks: who would drive the group to the beach, who would stock their fridge, who would cook them dinners before leaving them for a week of beer pong, sunburns and meetups with houses full of girls.Afterward, Seth stayed to watch a Washington Capitals playoff game. He loved these kinds of nights and, really, everything about high school. Cheering crowds at his football and baseball games, late-night Xbox sessions, fishing trips, parties in their parents’ basements. He could do without the academic part — he was a B student, at best — but he was planning to join the Army Reserve and maybe go to community college.With him at Matt’s was Josh Shaffer, a hockey player he’d been friends with since seventh grade, and Tyler Curtiss, the baseball team captain who had been homecoming king and prom king.Matt and Josh declined interview requests, but Seth and Tyler agreed to talk to The Washington Post about the vandalism. When they tell the story of that evening, they start with the end of the Caps game, when everyone but Seth was deep into a supply of Bud Light, and the conversation turned, once again, to their senior prank.

Seth Taylor

Tyler Curtiss

Tyler wanted to superglue locks. Seth suggested they grease up three pigs and release them into the school.

Or, somebody said, they could go spray paint the words “Class of 2018.”

Within minutes, they were driving to the school with spray paint from Matt’s parents’ garage. They parked at the church next door, tied T-shirts into masks over their faces and sprinted through the woods.

A shake of the can, the smell of fumes. The words went down easily, just as they had planned: “Class of 2018,” they wrote across the sidewalk.

And then Seth watched as Josh wrote something else: “BURTON IS A” it began.

Later, this was the moment he agonized over — the point at which he could have turned back. “I wish I said something, like, ‘This is stupid, guys. It’s not worth it. We could actually get in trouble for this.’”

Why he didn’t, he would always struggle to explain: “I don’t know. Everyone was doing it. We didn’t realize the consequences.”

“It was just spray paint. It just happened. It is all a blur.”

The blur went on for about seven minutes, during which all of them sprayed something hateful. Josh targeted the principal. Matt attacked Jewish, gay and black people. Tyler drew two swastikas. Seth drew swastikas, “fags” and “KKK.”

When a car drove by, they leaped behind the brick columns near the front entrance, hiding. A moment later, they started spraying again.

Finally, they ran back to their cars. They chucked their paint cans in the woods. They swore to each other that they would never admit what they did.

Seth came home to a quiet house. His sister was away at college, his father was on a business trip, and his mother was asleep. He went to the fridge and found the breakfast she had made for him to eat the next morning. Seth popped the eggs into the microwave. When he went to grab them, the plate slipped. The hot eggs tumbled onto his arms and legs. The shock somehow made it hit him. What had he just done?

Panicked, he started Googling:

“How long do you go to jail for vandalism?”

And then: “Can you get a hate crime for painting swastikas?”

Now he was sitting in the Glenelg auditorium, thinking about what he’d told his mom. Early that morning, she’d received an email from the school informing parents about the graffiti. Horrified, she texted Seth, warning him what he would find when he arrived at the awards ceremony.

“Who would do that?” he had texted back.

And in a sense, he meant it. He had already begun to separate what he’d done from who he believed himself to be. He hadn’t intended to hurt anyone, he said. He would always maintain he wasn’t an anti-Semite, a homophobe or a racist.

From the podium a voice said: “Tyler Curtiss.”

Seth looked up. His friend was walking toward the stage. But Tyler wasn’t getting in trouble. He was accepting an athletic leadership award. He was walking across the stage and shaking the principal’s hand.

Seth felt a tap on his shoulder. The athletic director was standing over him. “Seth,” he said quietly. “You need to come with me.”

Seth followed him out, trying not to look at his classmates. On the other side of the auditorium doors, two police officers were waiting to take him to the office of the school resource officer, Steve Willingham.

On the TV screen inside was security footage from the night before. Seth could see his own stout frame, paint can in hand, frozen in high definition.

“I bet you don’t want to see that, do you?” he remembers Willingham saying.

“No,” Seth answered.

“Do you know why you’re in here?”

“Yes,” Seth said. He didn’t know then that the officers had been strategic in pulling him out first. Willingham had coached Seth’s sister in soccer. He was friends with Seth’s dad. He suspected that of all the boys, Seth was the most likely to confess.

It took only one question: “What happened?”

“Things got out of hand,” Seth recalls telling him. “I was under the impression we were going to do a prank, and it got bad.”

He started to cry. He would be the only one who immediately admitted what they did. The others, court records show, would deny it. Tyler wished Willingham good luck in finding out who did it.

Eventually they were told: The school’s WiFi system requires students to use individual IDs to get online. After they log in once, their phones automatically connect whenever they are on campus.

At 11:35 p.m. on May 23, the students’ IDs began auto-connecting to the WiFi. It took only a few clicks to find out exactly who was beneath those T-shirt masks.

“You have the right to remain silent,” an officer said to Seth before long. “Anything you say or do . . . ”

They told him to remove his graduation cap and gown. They cuffed his arms behind his back.

Seth realized they were about to march him outside, past the windows of the cafeteria. By now it would be filled with students eating lunch.

“Can you cover my face so that the kids don’t videotape me?” he asked.

“No,” an officer replied. “You deserve this.”

By the end of the day, charges had been filed. Not just vandalism and destruction of property, but a hate crime. Prosecutors believed the young men had committed their acts with animosity toward protected groups — and that they could prove it. In Maryland, that meant that the punishment could be intensified. It meant they were looking at up to six years of incarceration.

Before they were released from jail that night, the four students watched on a small TV screen outside their holding cell while their crime was broadcast on the local news — as it would be over and over in the coming days. Viewers saw four white teens, scowling at the camera, and the school system’s superintendent vowing at a news conference to hold them accountable.

“Howard County stands out as a place where diversity and acceptance are cherished,” Michael Martirano said. It sounded like something any superintendent would say. But here, many knew, it came with a story: one taught to children in school, bragged about to visitors and proclaimed on signs.

In the early 1960s, before the Fair Housing Act and the legalization of interracial marriage in Maryland, a white developer named James Rouse began purchasing huge swaths of Howard County farmland to build a planned community named Columbia.

He envisioned it as a mixed-race, mixed-income utopia. “The next America,” he called it, and although racial tensions could never be completely erased, to many people, that is what it became. Today, the suburb — home to a third of the county’s 300,000 residents — is renowned for its ethnic diversity, interracial marriages, interfaith centers and high-achieving schools. It appears frequently on national “Best Places to Live” lists.

Most are unaware of the history that came before Columbia. The farmland Rouse purchased included former slave-holding plantations. An estimated 2,800 people were enslaved in the county at the beginning of the Civil War. A century later, when the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 that schools must be desegregated, Howard County was so resistant that it took more than a decade for the black-only school, Harriet Tubman, to close its doors. The opposition to black students learning alongside white ones was so fierce, a cross was burned. It happened outside a school dance at Glenelg High School.

Glenelg is in western Howard, the most rural part of the county, then and now. While the rest of Howard’s high schools have no racial majority, 76 percent of Glenelg students are white.

On the news that night, though, only students of color were interviewed.

“It’s just a small number of students who decide to make these decisions that negatively impact the image of our school,” one said.

“This is not representative of what Glenelg stands for,” said another.

That week, after Seth, Tyler, Matt and Josh were released from jail without having to pay bail, their classmates began to argue over whether those statements were true.

Tyler Hebron, a senior who was president of the school’s black student union, typed her feelings into an Instagram post. “It shouldn’t have taken this event to occur for us to observe the hateful actions of our peers,” she remembers writing. “We shouldn’t say we are surprised. We are not.”

During her freshman year, a student flew a Confederate flag at a football game. Swastikas were scratched into the bathroom stalls. In 2017, someone had written the n-word and Principal Burton’s name on a baseball dugout. She had heard boys play a game to see who could yell the n-word the loudest. To her, this crime was just high-profile proof of the hostility she had always felt.

Soon, comments started appearing beneath her Instagram post.

“You’re racist,” one said. “All you do is blame straight white males.”

The night before graduation, she found herself thinking about whether she should pack pepper spray in her purse. She wasn’t sure, she told her parents, that she felt safe.

Among black families like hers, there were doubts that the white teens would face the kind of punishment black teens receive for similar crimes. Two years earlier, a group of students had painted swastikas on a historic black schoolhouse in Northern Virginia. A Loudoun County judge sentenced them not to jail time or community service, but to reading: along with visiting the Holocaust museum, each had to choose a single book about Nazi Germany or the Jim Crow era and write a report on it.

Two black families came to Burton and told him they were pulling their kids out of Glenelg before the next school year. The principal tried to persuade them not to go.

But in his own house, his wife, Katrina, was wondering if he should leave, too.

They had two daughters to think about, an eighth-grader and a senior at another Howard County high school, who on the day of the hate crime had come home and collapsed in her mother’s arms, sobbing. Katrina knew about the parents who warned Burton not to talk about the incident in his speech at the graduation ceremony, and watched as some of them refused to stand and clap for him that day.

“Are you safe?” she kept asking her husband.

There had been so many incidents in his life that had made Burton question just that. When he was 16, and the parents of a white friend in his Michigan hometown called him the n-word. In college, when he and his fraternity brothers were pulled over and questioned by a group of white cops seemingly for no reason. At a convenience store in South Carolina just a few years ago, when a hostile clerk refused to serve him and his family.

But inside a school, he was an authority figure, the man in charge. For most of his career, he’d led schools in Prince George’s and Howard counties filled with students of color.

And then to his surprise, he was asked in 2016 to leave Howard County’s Long Reach High School, where a third of the students are black, and take over at Glenelg, where less than 5 percent are black. Here, he suspected, it would take time to win over the community.

He started standing in the halls every morning and every class break, looking students in the eye as he said hello. He attended as many games and plays and art shows as he could. He made sure the swastikas scratched in the bathroom were documented and investigated, but quietly, to avoid giving those who drew them the attention they were seeking.

After two years, he felt that he had earned the respect of this place, and these people. They welcomed him when he arrived at the annual end-of-the-year celebration for the senior class at an Ellicott City resort. Parents gave him hugs and thanked him for what he had done for their kids.

That night, he learned that one senior had been caught trying to order alcohol at the bar. The student was kicked out of the event, but the next day, Burton decided he didn’t want to be overly harsh in his punishment.

“Even though you did this, I am going to allow you to go to the school picnic,” he told the teen.

Less than a week later, it was the same student, Josh Shaffer, who would scrawl Burton’s name and the n-word onto the sidewalk.

“The person you married is not about to cower,” the principal told his wife. He wouldn’t be leaving Glenelg.

He could use the summer, he thought, to plan what he was going to do the following school year, the message he needed to send.

And if the prosecutors sought his help in holding his students accountable, he knew what his answer would be.

Every time Seth walked from the parking lot of the Howard County Circuit Court to its entrance, he passed a small, decaying building with barred windows and a slanted roof. He rushed by with his head down, passing a plaque that explained the structure's history. Here, slaves who'd tried to run to freedom were held before being returned to the people who owned them.

In late March, Seth entered the courthouse dressed in one of his father’s suits, accompanied by his parents. It was his final appearance in front of the judge overseeing all four Glenelg cases: William V. Tucker, a black man with a reputation for his interest in the way the criminal justice system handles young people.

One by one, they had come before him and pleaded guilty, or been found guilty after agreeing to a statement of facts.

Two of them had tried to have the hate-crime charges dismissed. Their attorneys claimed that their First Amendment rights were being violated. They could be punished for the vandalism, the argument went, but not for what they wrote.

It didn’t work.

Now, it was Tucker’s job to answer a question the community had been debating for nearly a year: What consequences did these young men, now 19, deserve?

They hadn’t been allowed to walk at graduation. Their post-high-school plans had been derailed, and they were working in landscaping, asbestos removal and, in Seth’s case, office furniture construction. Their names and mug shots were seared into Howard County’s memory and the Internet’s search results. It was up to Tucker to decide whether, on top of that, they should spend time in jail.

His view became clear when Joshua Shaffer was the first to be sentenced on March 8, 2019. Seth stayed home and kept refreshing his Internet browser, waiting for news. Finally, the local TV station published a video: Josh was being walked out of the courthouse in cuffs. He had been sentenced to three years of probation, 250 hours of community service and 18 consecutive weekends in Howard County Jail.

Seth’s parents called his attorney, Debra Saltz, in a panic. His case was different, she reminded them. He was different. They just had to persuade the judge to see that.

Saltz stood in court that March morning and pointed to her client.

“Your honor, I truly believe justice and mercy call on us to consider who he is,” she said. “And I believe it requires the court to consider what has happened in his life, what he has done since May 24.”

Seth, she explained, had been working to make amends. He’d completed 181 hours of community service. He’d written an apology letter to Principal Burton. He’d visited the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and volunteered at the Jewish Museum of Maryland. He’d spent time with an African American pastor and attended regular diversity training with an African American counselor.

He did it all with the support of his parents, who had spent the year agonizing over how their son could have done something so heinous. Seth’s father, Scott Taylor, stood to tell the judge he blamed himself.

“The letters ‘KKK’ were painted on the school. Seth didn’t understand the pain, suffering and terror associated with those letters, because I never told him,” the father said. “I never told him how the Klan used to collect money after church in my neighborhood when I was growing up in the South, and how they would stand in the road like the fire department.”

“I’ve come to realize I did fail,” he continued. “It’s not what I said in my home; it’s what I didn’t say.”

When it was Seth’s turn to speak, he assured his parents that it was not their fault.

“You taught me better,” he said. “This isn’t who you raised.”

He apologized to the principal and to the communities he hurt.

“It was the worst decision I have ever made in my entire life. What I did there keeps me up at night. I deserve whatever punishment I get,” he said. “I have worked hard since that day to show my family, my school, my community and Principal Burton how sorry I am.”

Seth said he just wanted all of them to understand: He is not a racist.

Later, he would explain himself this way: “I never really understood the symbol of the swastika. I knew it was wrong to plaster it somewhere. I didn’t learn exactly what [the Nazis] were doing to the Jews until I went to the Holocaust Museum. I never learned that they were mutilated. I knew that they were, like, burned. But I never learned that they had experiments done on them, were injected with diseases. The school didn’t include that. They just included the burning and the train cars.”

His understanding of the KKK was limited, too, he said. “Some people think it’s just a word, or a symbol or three letters put together. . . . But they were lynching people, hurting people for no good reason.”

Now, he said, he knows. But he still doesn’t believe his actions that night make him a bigot.

“I spray paint one racist thing and, suddenly, I become a racist? Just because I did it doesn’t mean I hate Jews, gay people or black people.”

He was standing before the judge, pleading guilty to a hate crime, but he would not admit that he harbored any hate.

All around him, the adults agreed.

“He will forever be known as the racist kid at Glenelg, but that’s not who Seth is,” his father said in court that day.

“I told him that his act was racist, but don’t let it define him as a racist. He can and I pray that he will go on and do better,” Maxwell Ware, the African American pastor he met with, wrote in a letter supporting him.

“He is not a racist . . . he has a good heart,” his attorney told the judge.

Behind her, Principal Burton was listening. He’d heard Joshua Shaffer’s attorney give a similar speech. When Matthew Lipp was sentenced, he would hear it then too. Tyler Curtiss had written it in a Facebook apology the day after the crime. Tyler, Burton knew, had turned to Jesus, joining a church where he talked openly about the swastikas he painted that night. He had spent months telling his story to Jewish congregations, interfaith groups and the county’s board of rabbis. Come the day of his sentencing, Tyler would say: “I hold no hatred toward any human being, especially those in the communities that were affected.”

They all believed it was possible to do what they did without really meaning it.

Burton wanted to look them in the eye and say: “You did something very racist. How you don’t think you’re a racist, I don’t know.”

What he did know was what they’d been taught in school: Glenelg covered the Holocaust and the Klan in detail, in U.S. history and American government and world history and in the books they read for language arts.

He believed what possessed them to draw those words and symbols that night wasn’t a lack of knowledge, but something deeper, something ugly, something taught to them, consciously or unconsciously, along the way. If they couldn’t admit that now, maybe they never would. But it wasn’t his responsibility to educate them any more.

When it was Burton’s turn to speak at Seth’s sentencing, he didn’t say the word “racism.” He talked about all the people the crime had affected — the teachers crying in his office, the parents who pulled their kids out of his school, his daughter in tears, and for just a few moments, himself: “I know I give up my time, my effort, I give up my life for my students,” he said. “I think the only thing I am asking in return is just a little bit of respect.”

The courtroom waited in silence for Judge Tucker to reach his decision. Seth kept his gaze on the table. His father rubbed his mother’s back.

“I appreciate the fact that you are now trying to show that you are not a racist, that you committed a racist act,” Tucker finally told Seth. “But part of what I need to do is punish you. So the sentence is going to be as follows.”

Three years probation. Two hundred fifty hours in community service. And nine consecutive weekends in jail.

“A normal weekend incarceration is Friday 6 p.m. to Sunday 6 p.m.,” Tucker said. It was a Thursday. “For this weekend, it begins today.”

A black sheriff’s deputy stepped behind Seth and pulled out her handcuffs. His mother began to cry.

“Alright, Mr. Taylor, good luck to you,” the judge said, and the metal closed around Seth’s wrists.

Six weeks later, Seth backed his car out of his parents' driveway, headed to his final weekend in jail.

Good behavior during his weekends locked up meant he had to serve only two-thirds of them.

The following weekend, Tyler Curtiss, who had painted two swastikas, would finish his weekends, five in all.

Matt Lipp, whose graffiti attacked Jewish, black and gay people, would serve 11 of the 16 he was sentenced to. He has filed an appeal, still arguing that his First Amendment rights had been violated.

Josh Shaffer, who targeted the principal, was sentenced to the most jail time: 18 weekends. He would serve 12.

All four will be eligible to get the hate crimes expunged from their record when their probation is finished.

Together they had figured out how to navigate their 48-hour stints locked up: how to make the time pass, how to hide their toilet paper so it wouldn’t be stolen, what to do when the other inmates threw dominoes at their heads.

Seth didn’t know the names of the people who gave them trouble, but he had nicknames he made up for them. “String Bean,” for the tall, lanky one. “Pistachio” for the one with the mustache.“

Two black kids who just do not like us,” he called them.

Now he drove past the high school, yawning as he turned toward the highway. He’d been up late the night before, playing Mortal Kombat with strangers on his Xbox. He felt comfortable there, behind the anonymity of his username. He didn’t feel that way anywhere in Howard County. He grew nervous anytime he saw a person of color, wondering if they recognized him and knew what he had done.

He didn’t think anyone would recognize him come Monday, when he was going to start a new job in a heating and cooling apprenticeship program an hour away. It was going to pay $14 an hour. If he liked it, he might get his HVAC license. And then in three years when his probation was over, he thought he might move to Florida. Do some fishing. Start over.

He pulled into the jail parking lot 20 minutes early, switched off his engine and pulled out his phone. He turned on Kodak Black, who started rapping about “nigga s---.”

A truck pulled up beside him and Seth rolled down his passenger window.

“Hey,” he called to Josh. The two were the only ones in the group who had stayed close friends. During the week, they went to the gym together late at night, when they wouldn’t see other people.

“You ready to play three hours of checkers?” Josh asked.

“I’m finding a book, man,” Seth said. “I can’t play Uno again. I’m never playing Uno again in my life as soon as I leave this jail.”

Josh pulled out a can of tobacco dip. Seth took a hit from his strawberry-flavored Juul. They sat there until Josh said, “You ready?” and then Seth followed him inside.

The principal steered into the high school lot a month later and parked in the same spot he had a year before. He stepped out of his SUV in one of his best black suits. It was the last day of school for the class of 2019.

Once again, there was going to be an awards ceremony and a picnic, but this year, there was no graffiti waiting for him.

In the weeks since his former students were sent to jail, he and his wife had been asked again and again what they thought of the punishment. People were outraged — either that the young men had received a “slap on the wrist” or that they had been so persecuted. Burton wouldn’t take a side. “To me, it felt like a crime,” he said. “But what happens because of that crime is not up to me to figure out.”

He had to focus on his 1,200 current students: the LGBTQ kids who still felt isolated. The Jewish girl who told the local paper she still wishes she could transfer. Whoever was still scrawling swastikas on the bathroom stalls.

In the past year, he’d created a task force of diverse students to work on the school’s climate. Soon every freshman would go through an empathy workshop. And nearly 40 of his employees had spent the year meeting to discuss the book “Waking Up White,” a memoir of a white woman who comes to understand that racism is a system that she had been shaped by and contributed to her entire life without even realizing it. Maybe, he thought, that lesson would get passed on to Glenelg’s students.

But on this morning, his job was to celebrate his seniors. He stood outside as they arrived in their red caps and gowns. Their parents and grandparents followed behind, cameras in hand.

Then he saw it: this year’s version of a senior prank. A tractor was pulling into the parking lot. On the front was an old couch bolted to the forklift, a sign that read “2019,” and a few students sprawled on the cushions. On the back was a blue flag. “TRUMP,” it read, “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN.”

The assistant principal set off after them, and Burton decided to let him handle it. Instead he made his way to the auditorium. He stepped up to the podium, looking out at his students’ faces. Then their names were called, and they came on stage to shake his hand.

#Seth Taylor#Matt Lipp#Josh Shaffer#Tyler Curtiss#Glenelg High School#racism#hate crime#Maryland#donald drumpf#donald tRump#drumpf#drumpfster fire#dumpster fire#make donald drumpf again#this is not normal#this isn't normal#tRump#tRump is not normal#tRump isn't normal#tRumpster fire#fuck this republican administration

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobody asked but I'm doing it cause who even reads my blog anyway? Questions time 1: is there a boy/girl in your life? No 2: think of the last person who hurt you; do you forgive them? Yeah, cause I wasn't exactly an angel to him either. 3: what do you think of when you hear the word “meow?” A cat? What else would I think of? 4: what’s something you really want right now? To fall in love. Also candy. 5: are you afraid of falling in love? Hell yeah. 6: do you like the beach? Hell yeah. 7: have you ever slept on a couch with someone else? All the time. 8: what’s the background on your cell? The lyrics to my favorite song. 9: name the last four beds you were sat on? Mine, my parents, my Jessica's, and my brothers. 10: do you like your phone? Yeah. I wish it was a 6 cause this one is so small, but at least it's not an android. 11: honestly, are things going the way you planned? For the most part. There are things missing and things undecided, but I'm still on track. 12: who was the last person whose phone number you added to your contacts? My neighbor's, I think. 13: would you rather have a poodle or a rottweiler? A poodle, because they are hypoallergenic. 14: which hurts the most, physical or emotional pain? Physical. 15: would you rather visit a zoo or an art museum? An art museum hands down. Zoos are cool, but a lot of them are cruel. 16: are you tired? Very much so, in many ways. 17: how long have you known your 1st phone contact? Not long, she was my driving instructor. 18: are they a relative? No 19: would you ever consider getting back together with any of your exes? Don't have one 20: when did you last talk to the last person you shared a kiss with? Never kissed anyone. 21: if you knew you had the right person, would you marry them today? Yes. Well, I would want to date them first, but if I had to I would. 22: would you kiss the last person you kissed again? I would kiss no one again, sure. 23: how many bracelets do you have on your wrists right now? None, just a hair tie. 24: is there a certain quote you live by? Not really, though I have one that I try to keep in mind, which is "the end cannot begin at the start" because I tend to forget that. 25: what’s on your mind? Boys, food, auditions. 26: do you have any tattoos? No 27: what is your favorite color? White or gray. 28: next time you will kiss someone on the lips? I don't know? 29: who are you texting? No one right now. 30: think to the last person you kissed, have you ever kissed them on a couch? Why are there so many questions about people I've kissed? 31: have you ever had the feeling something bad was going to happen and you were right? Hell yeah, all the time. 32: do you have a friend of the opposite sex you can talk to? Not talk deeply to. 33: do you think anyone has feelings for you? It's possible. 34: has anyone ever told you you have pretty eyes? Yeah. 35: say the last person you kissed was kissing someone right in front of you? OMFG (this sounds like something a fuckboy would ask) 36: were you single on valentines day? Babe, I'm always single 37: are you friends with the last person you kissed? For fuck sake 38: what do your friends call you? Ceci or Cec (not really how it would be spelled) 39: has anyone upset you in the last week? Oh yeah 40: have you ever cried over a text? Yeah, lots 41: where’s your last bruise located? I can't remember 42: what is it from? Still can't remember 43: last time you wanted to be away from somewhere really bad? Now. Winter makes me hate where I live. So does high school sometimes. 44: who was the last person you were on the phone with? My mom I think. 45: do you have a favourite pair of shoes? Yeah, just simple brown boots. 46: do you wear hats if your having a bad hair day? No (I don't really have bad hair days) 47: would you ever go bald if it was the style? I don't know. Probably not but that's easy for me to say. 48: do you make supper for your family? Not really, maybe once a year or less. 49: does your bedroom have a door? Yeah... whose doesn't? 50: top 3 web-pages? What? If this means websites, then Pinterest, Instagram, and tumblr. 51: do you know anyone who hates shopping? Yeah. 52: does anything on your body hurt? Not right now. 53: are goodbyes hard for you? They're easier for me than some people because I let go really easily, but depending on who it is, they're hard. 54: what was the last beverage you spilled on yourself? Water 55: how is your hair? It's good, how are you? It silky and shoulder length and brown, if that's what this meant. 56: what do you usually do first in the morning? Put on makeup. 57: do you think two people can last forever? Yes. 58: think back to january 2007, were you single? Lol, definitely. 59: green or purple grapes? Green. 60: when’s the next time you will give someone a big hug? I don't know... 61: do you wish you were somewhere else right now? Yeah, somewhere warm and calm and without trump. 62: when will be the next time you text someone? Maybe my mom when she picks me up, or my friends. 63: where will you be 5 hours from now? In bed. 64: what were you doing at 8 this morning. Sitting in class. 65: this time last year, can you remember who you liked? Jordan. 66: is there one person in your life that can always make you smile? Not really. Well, Alex kinda, but that's kinda relative. 67: did you kiss or hug anyone today? No, I probably will though. 68: what was your last thought before you went to bed last night? I can't really remember. Probably about college. 69: have you ever tried your hardest and then gotten disappointed in the end? Plenty. Musical auditions for one. 70: how many windows are open on your computer? I'm on my phone. 71: how many fingers do you have? 10....? 72: what is your ringtone? Kids by MGMT 73: how old will you be in 5 months? Still 18 74: where is your mum right now? Driving home 75: why aren’t you with the person you were first in love with or almost in love? I've never been in love or almost in love, but Jordan was the closest I got and that's because we never talked and now he has a girlfriend. 76: have you held hands with somebody in the past three days? I don't think so. 77: are you friends with the people you were friends with two years ago? Yeah. 78: do you remember who you had a crush on in year 7? Year 7 is 3rd grade and I think I had a crush on Johnny then, though that may have started in 4th. 79: is there anyone you know with the name mike? Yeah, but no one I know well. 80: have you ever fallen asleep in someones arms? When I was young I'm sure, but not since. 81: how many people have you liked in the past three months? Plenty of people I thought were attractive but not one crush. 82: has anyone seen you in your underwear in the last 3 days? My mom saw me in a bra. 83: will you talk to the person you like tonight? No. I don't really like anyone anyway. 84: you’re drunk and yelling at hot guys/girls out of your car window, you’re with? What? 85: if your bf/gf was into drugs would you care? Hell yeah. I'm not really in 86: what was the most eventful thing that happened last time you went to see a movie? 87: who was your last received call from? 88: if someone gave you $1,000 to burn a butterfly over a candle, would you? 89: what is something you wish you had more of? 90: have you ever trusted someone too much? 91: do you sleep with your window open?i that type of person anyway, I don't like self-destructive guys. 92: do you get along with girls? Yeah. 93: are you keeping a secret from someone who needs to know the truth? No 94: does sex mean love? No 95: you’re locked in a room with the last person you kissed, is that a problem? No because I'm locked in a room alone. 96: have you ever kissed anyone with a lip ring? FUCKING!!!! 97: did you sleep alone this week? Yes god stop making me feel bad about myself 98: everybody has somebody that makes them happy, do you? Yeah. 99: do you believe in love at first sight? No 100: who was the last person that you pinky promise? I'm not sure. This one sucked all it wanted to know was who I fucking kissed.

0 notes