#allosauroidea

Text

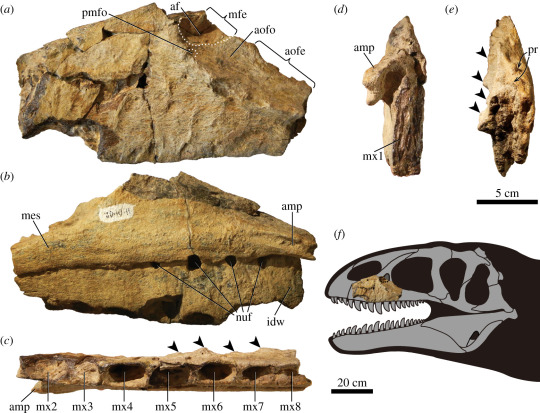

Meraxes gigas Canale et al., 2022 (new genus and species)

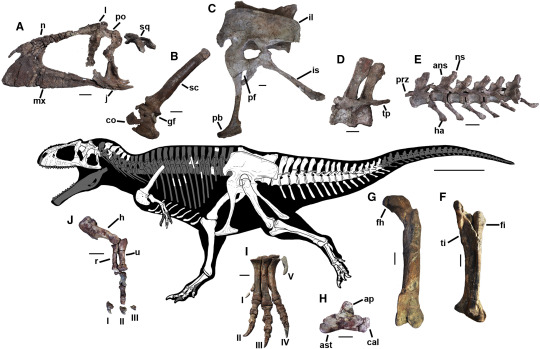

(Select bones and schematic skeletal of Meraxes gigas [scale bars = 10 cm for individual bones and 1 m for the skeletal], with preserved bones in white, from Canale et al., 2022)

Meaning of name: Meraxes = dragon character from the A Song of Ice and Fire novel series; gigas = giant [in Greek]

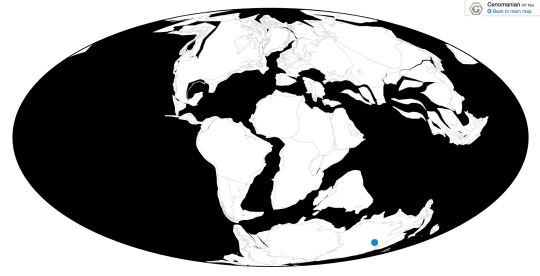

Age: Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian–Turonian)

Where found: Huincul Formation, Neuquén, Argentina

How much is known: Partial skeleton of one individual, including a nearly complete skull and limbs.

Notes: Meraxes was a carcharodontosaur, a group of large, carnivorous theropods that also includes Giganotosaurus and Acrocanthosaurus. It was probably closely related to other South American carcharodontosaurs like Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, and Tyrannotitan. These genera were among the largest known theropods, all of them (including Meraxes) having been estimated to have weighed over 4 tons.

Meraxes exhibits the most completely preserved skull and forelimbs of any Late Cretaceous carcharodontosaur discovered. Its forelimbs were greatly reduced in size, comparable in relative length to those of the famously short-armed tyrannosaurids. However, even though carcharodontosaurs had convergently evolved a similar body plan to tyrannosaurids, microscopic examination of their bone structure indicates that these two groups of large theropods grew in very different ways. Whereas giant tyrannosaurids reached their adult sizes by going through a growth spurt relatively early in life, Meraxes grew more slowly across a longer period of time. In fact, the type specimen of Meraxes is inferred to have been between 39–53 years old when it died, making it the oldest individual of a Mesozoic theropod known so far.

Reference: Canale, J.I., S. Apesteguía, P.A. Gallina, J. Mitchell, N.D. Smith, T.M. Cullen, A. Shinya, A. Haluza, F.A. Gianechini, and P.J. Makovicky. 2022. New giant carnivorous dinosaur reveals convergent evolutionary trends in theropod arm reduction. Current Biology advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.05.057

184 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beware of blue predatory Meraxes gigas. Is this the one with a sickle claw on its foot? Well yes. Could it be uses to pinning down its prey like both Dromaeosaurids and modern birds of prey? Probably not, it just rather be used for protection similar to cassowary when facing other foe. #sketchbookapp #paleoart #artistsoninstagram #myart #meraxes #meraxesgigas #giganotosaurini #carcharodontosauridae #allosauroidea #carnosauria #theropoda #dinosauria #dinosaur #theropoddinosaurs https://www.instagram.com/p/CgPQwemLiTe/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#sketchbookapp#paleoart#artistsoninstagram#myart#meraxes#meraxesgigas#giganotosaurini#carcharodontosauridae#allosauroidea#carnosauria#theropoda#dinosauria#dinosaur#theropoddinosaurs

0 notes

Text

It Came From The Wastebasket #07: Carnosaur Carnage

Carnosauria was originally named in the 1920s as a grouping for all of the large-bodied theropod dinosaurs known at the time.

For much of the 20th century it was used as a general wastebasket taxon collecting together all big carnivorous forms – including allosaurids, carcharodontosaurids, megalosaurids, spinosaurids, ceratosaurids, abelisauroids, and tyrannosaurids – and for a while it even included a species that later turned out to be closer related to crocodiles than to dinosaurs.

From left to right: Asfaltovenator vialidadi, Torvosaurus tanneri, Giganotosaurus carolinii, & Baryonyx walkeri

But then cladistic analysis in the 1980s and 1990s revealed that some of these theropods weren't actually closely related at all. Carnosaurs weren't a natural lineage but instead were highly polyphyletic, with the physical similarities between them seeming to be more due to convergent evolution than direct shared ancestry.

Some carnosaurs were split off and reclassified as more "primitive" types of theropod, while the tyrannosaurs were placed much closer to birds with the coelurosaurs. The remaining "carnosaurs" were just the allosaurids, carcharodontosaurs, and their closest relatives, and some paleontologists now prefer to use the name Allosauroidea for this group to distance it from the previous wastebasket mess.

…But Carnosauria might not be done just yet.

The discovery of Asfaltovenator in 2019 complicated matters once again, with a mixture of anatomical features linking it to both the allosauroids and the megalosauroids (megalosaurids, spinosaurids, and their relatives) – suggesting that these two groups might actually have been closely related to each other in a single lineage after all.

This would potentially return Carnosauria back to something surprisingly close to its original definition, with the various megalosauroids now forming an evolutionary grade leading to the allosauroids.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#it came from the wastebasket#wastebasket taxon#taxonomy#carnosaur#asfaltovenator#torvosaurus#giganotosaurus#baryonyx#theropod#dinosaur#paleontology#art#science illustration#paleoart#palaeoblr

338 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where would you fit Megaraptorans in the dinosaur family tree?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Species: Chandagurileos ("Lion of Chandaguru")

Clade: Allosauroidea

Diet: Carnivore

Size: 30 ft

Habitat: Forested Areas

Threat Level: 5/5 (Very Lethal)

Group Orientation: Pack Hunters

Fun Facts:

Unlike other large predators, Chandagurileos hunt in packs consisting of 3-6 members, but there have been reports of packs with up to 10 members. This allows them to have expansive territories, making them the most widespread member of the allosaur family. As pack hunters they also raise their young together and care for them even after they grow up, but fully grown males can go off on their own to form a new pack if they choose to. They are also extremely protective of their young, attacking and even killing any dinosaur that venture too close to their nests.

Chandagurileos can run down their prey without any problem. They are lightly built and more streamlined than other large predators, granting them greater speed over longer distances. They work together as a pack to bring down their prey and overpower it until exhaustion and blood loss takes its toll. They tend to hunt for smaller prey but will gang up to bring down large herbivores when hunting in a pack. Young Chandagurileos are effective hunters themselves, often straying from their nests to track down prey of their own.

Arkians of the Chandaguru forests come into contact with Chandagurileos more than any other southern predator. Arkians tend to be pretty easy targets, earning them a spot on the Chandagurileos' menu. The young go after them much more than the adults do and are considered more dangerous in that regard.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

#Siats was large powerful #predator, IF it is what all its fragmentary parts suggest it is! Siats marks a power transition between #Allosaurs and #tyrannosaurs.

#siats#theropod#dinosaur#dino#carnivore#natural history#scicomm#science#education#paleontology#fossils#fragmentary#carcharodontosaurid#neovenatorid#allosaur#allosauroidea#allosaurus#Utah#tyrannosaurs#early cretaceous

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

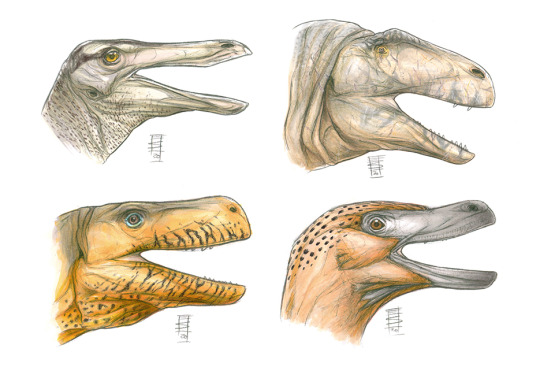

Exercise_Theropod Heads. Pencils and markers, 2020.

Top: Gallimimus (left), Acrocanthosaurus (right). Bottom: Herrerasaurus (left), Velociraptor (right).

References

Eddy DR, Clarke JA (2011) New Information on the Cranial Anatomy of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis and Its Implications for the Phylogeny of Allosauroidea (Dinosauria: Theropoda). PLoS ONE 6(3): e17932. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017932

Paul, G.S. 2002. Dinosaurs of the Air: the Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press (Baltimore)

#paleoart#dinosaur#theropod#ornithomimosaur#gallimimus#carnosaur#acrocanthosaurus#herrerasaurus#dromaeosaur#raptor#velociraptor#pencils#markers#exercise

270 notes

·

View notes

Text

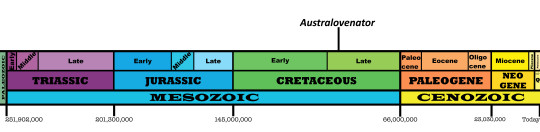

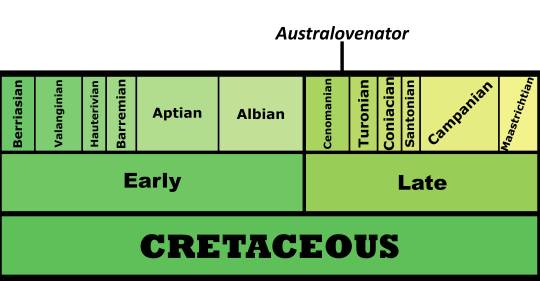

Australovenator wintonensis

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Southern Hunter

First Described By: Hocknull et al., 2009

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Megaraptora, Megaraptoridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: About 95 million years ago, in the Cenomanian of the Late Cretaceous

Australovenator is known from the Phimopollenites Pannosus Pollen Zone of the Winton Formation in Queensland, Australia

Physical Description: Australovenator was a Megaraptor, a group of fairly mysterious predatory dinosaurs that consistently confuse people since they were first discovered through today. The known parts of Australovenator are rather sparse - limbs and some parts of the torso, and a bit of the tip of the mouth. These elements show an animal with long legs, fairly long arms (for a theropod) with giant hand claws, and a slender jaw. The rest of our understanding of its size and shape is really based on its relatives. It would probably have been 6 meters long and 2 meters tall, weighing only 1,000 kilograms - making it a very lightweight, potentially fast predator. It had extremely flexible hands as well - more flexible than other theropods, almost able to pronate (ie, make “bunny hands”, which is not possible in other theropods). It also had extremely strong feet, built for kicking. Given that it was slender and small, it would have probably been covered in fluffy protofeathers all over its body.

By Ashley Patch

Diet: Australovenator would have been a major predator, able to eat a wide variety of small and medium sized animals in its environment - potentially even larger animals if it was able to work in groups.

Behavior: The behavior of Australovenator is not greatly known, given how mysterious Megaraptorans are as a general group. However, the extremely strong foot bones found with extensive signs of breakage indicates that Australovenator did use its feet to kick at prey, similar to modern emus. This would have greatly bruised and damaged the prey, potentially even breaking bones and causing internal bleeding and organ damage. The extremely flexible arms would have allowed it to use them to manipulate objects, grab at food, and easily claw at prey. In fact, the very large hand claws are notable for the Megaraptorans, since they were originally thought to be the giant foot claws of giant Dromaeosaurs. This ability to claw at and maim prey would have helped Australovenator extensively in taking down prey.

By José Carlos Cortés

Were Megaraptorans social? We aren’t sure. Australovenator was a powerful predator, clearly able to take down other animals in its environment without much help. It may have worked in small groups in order to get food larger than it, such as the sauropod Diamantinasaurus, since there weren't larger predators in its environment. However, there is no direct evidence to support that. Furthermore, in plenty of locations, Megaraptorans are very rare, indicating they wouldn’t have grouped up together much. Still, they usually aren’t the largest predators in a place, so the jury is out for Australovenator. As a dinosaur, it would have probably taken care of its young, though in what way is a question.

By PaleoEquii, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: The Winton Environment was a river basin, next to the former inland Eromanga Sea. This was a highly forested ecosystem with extensive swamps, creeks, lakes, and estuaries leading back to the sea. The dense vegetation made it a hotbed for herbivores, which were all sources of prey for Australoveantor. In fact, Australovenator was found directly with Diamantinasaurus, a 15 to 16 meter long sauropod (indicating that Australovenator may have been scavenging, or worked in a group and was killed by a group member). Other herbivores included the titanosaurs Wintonotitan and Savannasaurus, and the Somphospondylian Austrosaurus. There were a variety of Ornithischians there, though none were named, they may have been Rhabdodonts or Elasmarians; and there was at least one Ankylosaur (probably a basal Ankylosaurid). In addition, there was the large pterosaur Ferrodraco, and the narrow-snouted Crocodylomorph Isisfordia.

By Ripley Cook

Other: Megaraptors like Australovenator are a taxonomical quagmire. They are either closely related to the Carnosaurs - animals like Allosaurus and Giganotosaurus - or to early Coelurosaurs such as the Tyrannosaurs. It���s possible they are Tyrannosaurs, full stop, but an early group of them. Honestly, the question is still up in the air - but they combine a lot of the characteristics of the earlier theropods with the more bird-like ones, which leads to this confusion. Regardless, Australovenator was a very late derived Megaraptor, nested deep within the group.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Agnolin, F. L., M. D. Ezcurra, D. F. Pais and S. W. Salisbury. 2010. A reappraisal of the Cretaceous non-avian dinosaur faunas from Australia and New Zealand: evidence for their Gondwanan affinities. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 8(2):257-300.

Apesteguía, Sebastián; Smith, Nathan D.; Valieri, Rubén Juárez; Makovicky, Peter J. (2016-07-13). "An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157793.

Benson, R. B. J., M. T. Carrano, and S. L. Brusatte. 2010. A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic. Naturwissenschaften 97:71-78.

Brougham, T., E. T. Smith, and P. R. Bell. 2019. New theropod (Tetanurae: Avetheropoda) material from the ‘mid’-Cretaceous Griman Greek Formation at Lightning Ridge, New South Wales, Australia. Royal Society Open Science 6:180826:1-18.

Carrano, M. T., R. B. J. Benson, and S. D. Sampson. 2012. The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10(2):211-300.

Csiki-Sava, Z., S. L. Brusatte, and S. Vasile. 2016. “Megalosaurus cf. superbus” from southeastern Romania: the oldest known Cretaceous carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and its implications for earliest Cretaceous Europe-Gondwana connections. Cretaceous Research 60:221-238.

Hendrickx, C., and O. Mateus. 2014. Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal and dentition-based phylogeny as a contribution for the indentification of isolated theropod teeth. Zootaxa 3759(1):1-74.

Hocknull, S. A., M. A. White, T. R. Tischler, A. G. Cook, N. D. Calleja, T. Sloan, and D. A. Elliot. 2009. New mid-Cretaceous (latest Albian) dinosaurs from Winton, Queensland, Australia. PLoS ONE 4(7):e6190:1-51.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Molnar, Ralph E.; Currie, Philip J. (2004). Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Halszka, Osmólska (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 71–110.

Leahey, Lucy G.; Salisbury, Steven W. (June 2013). "First evidence of ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) from the mid-Cretaceous (late Albian–Cenomanian) Winton Formation of Queensland, Australia". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 37 (2): 249–257.

Molnar, Ralph E.; Flannery, Timothy F.; Rich, Thomas H.V. (1981). "An allosaurid theropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Victoria, Australia". Alcheringa. 5 (2): 141–146.

Novas, F. E.; Agnolín, F. L.; Ezcurra, M. D.; Canale, J. I.; Porfiri, J. D. (2012). "Megaraptorans as members of an unexpected evolutionary radiation of tyrant-reptiles in Gondwana". Ameghiniana. 49 (Suppl): R33.

Pentland, Adele H.; Poropat, Stephen F.; Tischler, Travis R.; Sloan, Trish; Elliott, Robert A.; Elliott, Harry A.; Elliott, Judy A.; Elliott, David A. (December 2019). "Ferrodraco lentoni gen. et sp. nov., a new ornithocheirid pterosaur from the Winton Formation (Cenomanian–lower Turonian) of Queensland, Australia". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 13454.

Porfiri, Juan D.; Novas, Fernando E.; Calvo, Jorge O.; Agnolín, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Cerda, Ignacio A. (2014). "Juvenile specimen of Megaraptor (Dinosauria, Theropoda) sheds light about tyrannosauroid radiation". Cretaceous Research. 51: 35–55.

Poropat, S.F.; Mannion, P.D.; Upchurch, P.; Hocknull, S.A.; Kear, B.P.; Kundrát, M.; Tischler, T.R.; Sloan, T.; Sinapius, G.H.K.; Elliott, J.A.; Elliott, D.A. (2016). "New Australian sauropods shed light on Cretaceous dinosaur palaeobiogeography". Scientific Reports. 6: 34467.

Salisbury, S. W., A. Romilio, M. C. Herne, R. T. Tucker, and J. P. Nair. 2016. The Dinosaurian Ichnofauna of the Lower Cretaceous (Valanginian–Barremian) Broome Sandstone of the Walmadany Area (James Price Point), Dampier Peninsula, Western Australia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 16. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36(6, suppl.):1-152.

Tucker, Ryan T.; Roberts, Eric M.; Hu, Yi; Kemp, Anthony I.S.; Salisbury, Steven W. (September 2013). "Detrital zircon age constraints for the Winton Formation, Queensland: Contextualizing Australia's Late Cretaceous dinosaur faunas". Gondwana Research. 24 (2): 767–779.

White, M. A.; Cook, A. G.; Hocknull, S. A.; Sloan, T.; Sinapius, G. H. K.; Elliott, D. A. (2012). Dodson, Peter (ed.). "New Forearm Elements Discovered of Holotype Specimen Australovenator wintonensis from Winton, Queensland, Australia". PLoS ONE. 7 (6): e39364.

White, M. A.; Falkingham, P. L.; Cook, A. G.; Hocknull, S. A.; Elliott, D. A. (2013). "Morphological comparisons of metacarpal I for Australovenator wintonensis and Rapator ornitholestoides: Implications for their taxonomic relationships". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 37 (4): 435–441.

White, Matt A.; Benson, Roger B. J.; Tischler, Travis R.; Hocknull, Scott A.; Cook, Alex G.; Barnes, David G.; Poropat, Stephen F.; Wooldridge, Sarah J.; Sloan, Trish (2013-07-24). "New Australovenator Hind Limb Elements Pertaining to the Holotype Reveal the Most Complete Neovenatorid Leg". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e68649.

White, M. A., P. R. Bell, A. G. Cook, D. G. Barnes, T. R. Tischler, B. J. Bassam, and D. A. Elliot. 2015. Forearm range of motion in Australovenator wintonensis (Theropoda, Megaraptoridae). PLoS ONE 10(9):e0137709:1-20.

White, Matt A.; Bell, Phil R.; Cook, Alex G.; Poropat, Stephen F.; Elliott, David A. (2015-12-15). "The dentary of Australovenator wintonensis(Theropoda, Megaraptoridae); implications for megaraptorid dentition". PeerJ. 3: e1512.

White, Matt A.; Cook, Alex G.; Klinkhamer, Ada J.; Elliott, David A. (2016-08-03). "The pes ofAustralovenator wintonensis(Theropoda: Megaraptoridae): analysis of the pedal range of motion and biological restoration". PeerJ. 4: e2312.

White, Matt A.; Cook, Alex G.; Rumbold, Steven J. (2017-06-06). "A methodology of theropod print replication utilising the pedal reconstruction of Australovenator and a simulated paleo-sediment". PeerJ. 5: e3427.

Zanno, L. E.; Makovicky, P. J. (2013). "Neovenatorid theropods are apex predators in the Late Cretaceous of North America". Nature Communications. 4: 2827.

#Australovenator wintonensis#Australovenator#Theropod#Megaraptor#Dinosaur#Factfile#Palaeoblr#Dinosaurs#Theropod Thursday#Cretaceous#Australia & Oceania#Carnivore#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

328 notes

·

View notes

Note

Carnosauria or Allosauroidea?

I favor using Carnosauria as “anything closer to Allosaurus than to crown-birds” and Allosauroidea as “the last common ancestor of Allosaurus and Sinraptor and all of its descendants”, as suggested in The Dinosauria. Given that, under these definitions, there are currently no non-allosauroid carnosaurs known, the two are functionally (but not technically) identical.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

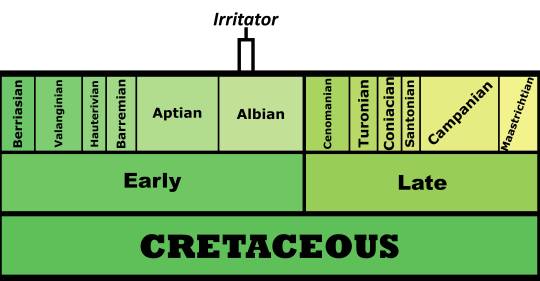

Ulughbegsaurus uzbekistanensis Tanaka et al., 2021 (new genus and species)

(Type maxilla [bone in the upper jaw] of Ulughbegsaurus uzbekistanensis, from Tanaka et al., 2021)

Meaning of name: Ulughbegsaurus = [Timurid sultan, astronomer, and mathematician] Ulugh Beg’s lizard; uzbekistanensis = from Uzbekistan

Age: Late Cretaceous (Turonian), about 90–92 million years ago

Where found: Bissekty Formation, Navoiy, Uzbekistan

How much is known: Several partial maxillae (bones in the upper jaw).

Notes: Ulughbegsaurus was a carcharodontosaur, a group of large, carnivorous theropods that also includes Giganotosaurus and Acrocanthosaurus. Estimated to have been 7.5–8 m long, Ulughbegsaurus was not one of the biggest carcharodontosaurs. However, it is the largest predator known from the Bissekty Formation, surpassing the size of tyrannosauroids and dromaeosaurids that have been previously described from the same horizon.

Reference: Tanaka, K., O.U.O. Anvarov, D.K. Zelenitsky, A.S. Ahmedshaev, and Y. Kobayashi. 2021. A new carcharodontosaurian theropod dinosaur occupies apex predator niche in the early Late Cretaceous of Uzbekistan. Royal Society Open Science 8: 210923. doi: 10.1098/rsos.210923

109 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I was originally gonna do something for this country fair as of today, but now they canceled because of pandemic of 2020, that won’t even stopped me for posting #paleoart like a siats meekerorum now being more Neovenatoridae than to Megaraptoridae with more realistic versions and even more better skin colors and especially with Saurian lip. As my paleoart of siats is being better than last time since in 2013 and early 2014, now I could see it good. On the side note, I just finished up with my last two pages from my sketchbook started from last year in college’s drawing class to all away to lockdown as the start of 2020 and now then cardboard covers is easy to use to sketch, inked and colored with colored pencils. #siats #siatsmeekerorum #coloredpencil #coloredpencils #neovenatoridae #carcharodontosauria #allosauroidea #carnosauria #avetheropoda #theropoda #dinosauria #artistsoninstagram #sketchbook #myart https://www.instagram.com/p/CDcb-VPFcr1/?igshid=vculhi42pxl5

#paleoart#siats#siatsmeekerorum#coloredpencil#coloredpencils#neovenatoridae#carcharodontosauria#allosauroidea#carnosauria#avetheropoda#theropoda#dinosauria#artistsoninstagram#sketchbook#myart

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

My sweet male Allosaurus gets colored :) <3

I decided this time to make a video of the drawing process.

#Allosaurus#allosaur#male#allosauroidea#theropod#dinosaur#feathered#digital art#gimp#sketch#drawing#video#art process#art creation#youtube#deviantart#myart

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 19-20 of the week 4: Your favorite dinosaur (as a baby) A baby allosaurus europaeus, based on the incomplete skull as unnamed specie of the latter hatching. I just went to sketch, inked and painted my favorite theropoda allosaurus as baby, after I’m done this from last 2 weeks ago. #sketchbookapp #paleoart #myart #dinocember #dinocember2021 #allosaurus #allosauruseuropaeus #sketchbookappart #sketchbookappartist #allosauridae #allosauroidea #carnosauria #artistsoninstagram #dinosaur #dinosauria #theropoda #avetheropoda https://www.instagram.com/p/CXthy-JFguM/?utm_medium=tumblr

#sketchbookapp#paleoart#myart#dinocember#dinocember2021#allosaurus#allosauruseuropaeus#sketchbookappart#sketchbookappartist#allosauridae#allosauroidea#carnosauria#artistsoninstagram#dinosaur#dinosauria#theropoda#avetheropoda

0 notes

Photo

Quick Doodle_Acrocanthosaurus Head Study.

Digital, 2020.

References

Eddy DR, Clarke JA (2011) New Information on the Cranial Anatomy of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis and Its Implications for the Phylogeny of Allosauroidea (Dinosauria: Theropoda). PLoS ONE 6(3): e17932. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017932

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

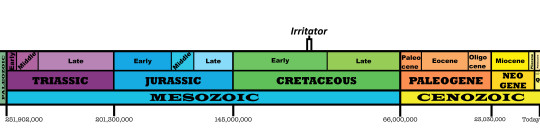

Irritator challengeri

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: The One That Irritated

First Described By: Martill et al., 1996

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Megalosauroidea, Megalosauria, Spinosauridae, Spinosaurinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 110 and 108 million years ago, in the Albian of the Early Cretaceous

Irritator is known from the Romualdo Member of the Santana Formation in Brazil

Physical Description: Irritator was a Spinosaurid, so the weird crocodile-mimicking theropods that roamed the Cretaceous landscape across the Southern hemisphere (and some of Europe). Irritator, however, is not known from very much material, despite having loads written about it. It was one of the smaller members of the Spinosaur group, only about 7.5 meters long and not weigh more than one tonne - which may actually indicate it could have still had some sort of fluffy integument, though this still seems unlikely based on its ecology. As a Spinosaur, Irritator would have been fairly bulky, with a long and vaguely crocodilian skull. Its skull also featured a long thin crest going from the midline to the eye, where it flattened into a bulge - this was probably some sort of display structure. Little is known of the rest of its skeleton, but it is known to have had a long and well-clawed hand. It probably had some sort of sail on its back, but it probably was a shorter one, and whether or not its legs were a normal size is unknown.

By Alexander Vieira, CC BY-SA 4.0 (Irritator is on the far right, in green)

Diet: Irritator would have mainly fed upon fish and other aquatic organisms.

Behavior: Irritator, being a Spinosaur, spent most of its time in the water, swimming about and searching for food. Since it was rather small, it would have been able to fit in smaller streams of water than most of its other relatives. Though, since it probably still had fairly decent legs, it also would have spent a good amount of time on the land, surveying the shore for food and seeking out prey. Its long snout would then be used to grab fish and other animals from the water, using the lightweight instrument to grab food it might not be able to reach otherwise. While swimming, it would be able to use that snout to reach even more food than before, ducking its head underwater or doing the reverse to hide from land sources of prey. Its very powerful neck muscles would have also been extremely helpful in grabbing and holding onto thrashing prey.

By Fred Wierum, CC BY 3.0

Irritator was probably warm-blooded, and used its sail more for display than for keeping warm. This display structure may have been able to change color based on blood circulation or environment in order to send different messages to other members of the species. The crest on the center of the snout also probably served similar features, for displaying to one another. It seems likely that Irritator, like most other dinosaurs, took care of its young; but there is no evidence either way to support that hypothesis.

By PaleoGeekSquared, CC BY 3.0

Ecosystem: Irritator lived in the Romualdo Environment of Brazil, which was a basin of lakes surrounded by rivers and other wetland environments, filled to the brim with a wide variety of plantlife. Nearby was the burgeoning Atlantic Ocean, making this a Spinosaur’s favorite place of all. Here there were a wide variety of early flowering plants like magnolias, seagrasses, and lilies - all of which were associated heavily with this aquatic environment. There were many types of ray-finned fish, which would have been the primary source of prey for Irritator, as well as lobe-finned fish which would have also been decent sources of food. Sharks seem to have been rare. There were plenty of turtles too, including one of the earliest sea turtles Santanachelys. This was the land of extreme pterosaurs, including Anhanguera, Arirpesaurus, Barbosania, Brasileodactylus, Cearadacytlus, Maaradactylus, Santanadactylus, Tapejara, Thalassodromeus, Tropeognathus, Tupuxuara, and Unwindia. There was also a Notosuchian, Araripesuchus. There were other dinosaurs there too - the compsognathid Mirischia and the Tyrannosauroid Santanaraptor, which would have mainly fed on small animal prey.

By Scott Reid

Other: Irritator was found as part of the illegal fossil trade, initially mistake for a pterosaur, then a maniraptoran, before being finally identified as a spinosaur. The confusion surrounding this fossil - and the fact that the snout had been artificially elongated by the fossil traders - lead to its name. Its position within the Spinosaurs is well supported, and it seems to have been at least somewhat closely related to Spinosaurus itself, rather than Baryonyx on the other end of the family tree.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Allain, Ronan; Xaisanavong, Tiengkham; Richir, Philippe; Khentavong, Bounsou (2012-04-18). "The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early cretaceous of Laos". Naturwissenschaften. 99 (5): 369–377.

Amiot, R.; Buffetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Wang, X.; Boudad, L.; Ding, Z.; Fourel, F.; Hutt, S.; Martineau, F.; Medeiros, A.; Mo, J.; Simon, L.; Suteethorn, V.; Sweetman, S.; Tong, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Z. (2010). "Oxygen isotope evidence for semi-aquatic habits among spinosaurid theropods". Geology. 38 (2): 139–142.

Arden, T.M.S.; Klein, C.G.; Zouhri, S.; Longrich, N.R. (2018). "Aquatic adaptation in the skull of carnivorous dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) and the evolution of aquatic habits in Spinosaurus". Cretaceous Research. In Press: 275–284.

Aureliano, Tito; Ghilardi, Aline M.; Buck, Pedro V.; Fabbri, Matteo; Samathi, Adun; Delcourt, Rafael; Fernandes, Marcelo A.; Sander, Martin (2018-05-03). "Semi-aquatic adaptations in a spinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 90: 283–295.

Bantim, Renan A.M.; Saraiva, Antônio A.F.; Oliveira, Gustavo R.; Sayão, Juliana M. (2014). "A new toothed pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea: Anhangueridae) from the Early Cretaceous Romualdo Formation, NE Brazil". Zootaxa. 3869 (3): 201–223.

Barrett, Paul; Butler, Richard; Edwards, Nicholas; Milner, Andrew R. (2008-12-31). "Pterosaur distribution in time and space: An atlas". Zitteliana Reihe B: Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung Fur Palaontologie und Geologie. 28: 61–107.

Benson, R.B.J.; Carrano, M.T.; Brusatte, S.L. (2009). "A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (1): 71–78.

Benyoucef, Madani; Läng, Emilie; Cavin, Lionel; Mebarki, Kaddour; Adaci, Mohammed; Bensalah, Mustapha (2015-07-01). "Overabundance of piscivorous dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) in the mid-Cretaceous of North Africa: The Algerian dilemma". Cretaceous Research. 55: 44–55.

Bertin, Tor (2010-12-08). "A catalogue of material and review of the Spinosauridae". PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 7.

Bertozzo, F., B. Favaretto, M. Bon and FM Dalla Vecchia. 2013. The wallpaper of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis Taquet, 1976 (Ornithischia, Ornithopoda) exhibited at the Natural History Museum of Venice: history of the find and perspectives for detailed studies [The paratype of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis Taquet, 1976 (Ornithischia, Ornithopoda) exhibited at the Museum of Natural History of Venice: history of discovery and prospects for detailed studies]. Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of Venice 64 : 119-130

Bittencourt, Jonathas; Kellner, Alexander (2004-01-01). "On a sequence of sacrocaudal theropod dinosaur vertebrae from the Lower Cretaceous Santana Formation, northeastern Brazil". Arq Mus Nac. 62: 309–320.

Brito, Paulo; Yabumoto, Yoshitaka (2011). "An updated review of the fish faunas from the Crato and Santana formations in Brazil, a close relationship to the Tethys fauna". Bulletin of Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History and Human History, Ser. A. 9.

Buffetaut, E.; Ouaja, M. (2002). "A new specimen of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Tunisia, with remarks on the evolutionary history of the Spinosauridae" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 173 (5): 415–421.

Buffetaut, E.; Martill, D.; Escuillié, F. (2004). "Pterosaurs as part of a spinosaur diet". Nature. 430 (6995): 33.

Candeiro, C. R. A., A. G. Martinelli, L. S. Avilla and T. H. Rich. 2006. Tetrapods from the Upper Cretaceous (Turonian–Maastrichtian) Bauru Group of Brazil: a reappraisal. Cretaceous Research 27:923-946

Candeiro, C. R. A., A. Cau, F. Fanti, W. R. Nava, and F. E. Novas. 2012. First evidence of an unenlagiid (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Maniraptora) from the Bauru Group, Brazil. Cretaceous Research 37:223-226

Carrano, M. T., R. B. J. Benson, and S. D. Sampson. 2012. The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10(2):211-300

Charig, A.J.; Milner, A.C. (1997). "Baryonyx walkeri, a fish-eating dinosaur from the Wealden of Surrey". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of London. 53: 11–70.

Cuff, Andrew R.; Rayfield, Emily J. (2013-05-28). "Feeding Mechanics in Spinosaurid Theropods and Extant Crocodilians". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e65295.

Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Buffetaut, Eric; Mendez, Marco A. (2005-12-30). "New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its size and affinities". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 888–896.

de Lapparent de Broin, F. (2000). "The oldest pre-Podocnemidid turtle (Chelonii, Pleurodira), from the early Cretaceous, Ceará state, Brasil, and its environment". Treballs del Museu de Geologia de Barcelona. 9: 43–95.

Evers, Serjoscha W.; Rauhut, Oliver W.M.; Milner, Angela C.; McFeeters, Bradley; Allain, Ronan (2015). "A reappraisal of the morphology and systematic position of the theropod dinosaur Sigilmassasaurus from the 'middle' Cretaceous of Morocco". PeerJ. 3: e1323.

Ezcurra, M. D. 2009. Theropod remains from the uppermost Cretaceous of Colombia and their implications for the palaeozoogeography of western Gondwana. Cretaceous Research 30:1339-1344

Figueiredo, R.G.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2009). "A new crocodylomorph specimen from the Araripe Basin (Crato Member, Santana Formation), northeastern Brazil". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 83 (2): 323–331.

Frey, E.; Martill, D.M. (1994). "A new Pterosaur from the Crato Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian) of Brazil". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 194: 379–412.

Furtado, M. R., C. R. A. Candeiro, and L. P. Bergqvist. 2013. Teeth of Abelisauridae and Carcharodontosauridae cf. (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from the Campanian- Maastrichtian Presidente Prudente Formation (southwestern São Paulo State, Brazil). Estudios Geológicos 69(1):105-114

Gaffney, Eugene S.; de Almeida Campos, Diogenes; Hirayama, Ren (2001-02-27). "Cearachelys, a New Side-necked Turtle (Pelomedusoides: Bothremydidae) from the Early Cretaceous of Brazil". American Museum Novitates. 3319: 1–20.

Gaffney, Eugene S.; Tong, Haiyan; Meylan, Peter A. (2009-09-02). "Evolution of the side-necked turtles: The families Bothremydidae, Euraxemydidae, and Araripemydidae". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 300: 1–698.

Gibney, Elizabeth (2014-03-04). "Brazil clamps down on illegal fossil trade". Nature. 507 (7490): 20.

Hassler, A.; Martin, J.E.; Amiot, R.; Tacail, T.; Godet, F. Arnaud; Allain, R.; Balter, V. (2018-04-11). "Calcium isotopes offer clues on resource partitioning among Cretaceous predatory dinosaurs". Proc. R. Soc. B. 285 (1876): 20180197.

Henderson, Donald M. (2018-08-16). "A buoyancy, balance and stability challenge to the hypothesis of a semi-aquatic Spinosaurus Stromer, 1915 (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". PeerJ. 6: e5409

Hendrickx, C., and O. Mateus. 2014. Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal and dentition-based phylogeny as a contribution for the indentification of isolated theropod teeth. Zootaxa 3759(1):1-74

Hirayama, Ren (1998). "Oldest known sea turtle". Nature. 392 (6677): 705–708.

Holtz, Thomas; Molnar, Ralph E.; Currie, Philip (2004-06-12). "Basal Tetanurae". The Dinosauria: Second Edition. University of California Press. pp. 71–110.

Ibrahim, N.; Sereno, P.C.; Dal Sasso, C.; Maganuco, S.; Fabbri, M.; Martill, D.M.; Zouhri, S.; Myhrvold, N.; Iurino, D.A. (2014). "Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science. 345 (6204): 1613–1616.

Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (1996). "First Early Cretaceous dinosaur from Brazil with comments on Spinosauridae". N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh. 199 (2): 151–166.

Kellner, A.W.A. (1996). "Remarks on Brazilian dinosaurs". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 39 (3): 611–626.

Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2000). "Brief review of dinosaur studies and perspectives in Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 72 (4): 509–538.

Kellner, A.W.A. (2001). "New information on the theropod dinosaurs from the Santana Formation (Aptian-Albian), Araripe Basin, Northeastern Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (supplement to 3): 67A.

Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2002). "The function of the cranial crest and jaws of a unique pterosaur from the early Cretaceous of Brazil". Science. 297 (5580): 389–392.

Kellner, A. W. A., S. A. K. Azevedo, E. B. Machado, L. B. Carvalho, and D. D. R. Henriques. 2011. A new dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Alcântara Formation, Cajual Island, Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 83(1):99-108

Lee, Yuong-Nam; Barsbold, Rinchen; Currie, Philip J.; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Lee, Hang-Jae; Godefroit, Pascal; Escuillié, François; Chinzorig, Tsogtbaatar (2014). "Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus". Nature. 515 (7526): 257–260.

Lopes, Reinaldo José (September 2018). "Entenda a importância do acervo do Museu Nacional, destruído pelas chamas no RJ". Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese).

Mabesoone, J.M.; Tinoco, I.M. (1973-10-01). "Palaeoecology of the Aptian Santana Formation (Northeastern Brazil)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 14 (2): 97–118.

Machado, E.B.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2005). "Notas Sobre Spinosauridae (Theropoda, Dinosauria)" (PDF). Anuário do Instituto de Geociências – UFRJ (in Portuguese). 28 (1): 158–173.

Machado, E.B.; Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2005). "Preliminary information on a dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) pelvis from the Cretaceous Santana Formation (Romualdo Member) Brazil". Congresso Latino-Americano de Paleontologia de Vertebrados. 2 (Boletim de resumos): 161–162.

Machado, E.B.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2008). "An overview of the Spinosauridae (Dinosauria, Theropoda) with comments on the Brazilian material". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28(3): 109A.

Martill, D. M., A. R. I. Cruickshank, E. Frey, P. G. Small, and M. Clarke. 1996. A new crested maniraptoran dinosaur from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Brazil. Journal of the Geological Society, London 153:5-8

Martill, David M. (2011). "A new pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Santana Formation (Cretaceous) of Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 236–243.

Martill, David; Frey, Eberhard; Sues, Hans-Dieter; Cruickshank, Arthur R.I. (2011-02-09). "Skeletal remains of a small theropod dinosaur with associated soft structures from the Lower Cretaceous Santana Formation of NE Brazil". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 37 (6): 891–900.

Mateus, Octávio; Araujo, Ricardo; Natario, Carlos; Castanhinha, Rui (2011-04-21). "A new specimen of the theropod dinosaur Baryonyx from the early Cretaceous of Portugal and taxonomic validity of Suchosaurus". Zootaxa: 54–68.

Medeiros, M. A. 2006. Large theropod teeth from the Eocenomanian of northeastern Brazil and the occurrence of Spinosauridae. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 9(3):333-338

Medeiros, Manuel Alfredo; Lindoso, Rafael Matos; Mendes, Ighor Dienes; Carvalho, Ismar de Souza (August 2014). "The Cretaceous (Cenomanian) continental record of the Laje do Coringa flagstone (Alcântara Formation), northeastern South America". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 53: 50–58.

Milner, Andrew; Kirkland, James (2007). "The case for fishing dinosaurs at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm". Utah Geological Survey Notes. 39 (3): 1–3.

Naish, D.; Martill, D.M.; Frey, E. (2004). "Ecology, Systematics and Biogeographical Relationships of Dinosaurs, Including a New Theropod, from the Santana Formation (?Albian, Early Cretaceous) of Brazil". Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 57–70.

Naish, D., and D. M. Martill. 2007. Dinosaurs of Great Britain and the role of the Geological Society of London in their discovery: basal Dinosauria and Saurischia. Journal of the Geological Society, London 164:493-510

Pêgas, R.V.; Costa, F.R.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2018). "New Information on the osteology and a taxonomic revision of the genus Thalassodromeus (Pterodactyloidea, Tapejaridae, Thalassodrominae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (2): e1443273.

Rauhut, Oliver W.M. (2003). The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. London: The Palaeontological Association.

Rayfield, Emily J.; Milner, Angela C.; Xuan, Viet Bui; Young, Philippe G. (2007-12-12). "Functional morphology of spinosaur 'crocodile-mimic' dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (4): 892–901.

Sales, Marcos A.F.; Lacerda, Marcel B.; Horn, Bruno L.D.; de Oliveira, Isabel A.P.; Schultz, Cesar L. (2016-02-01). "The 'χ' of the Matter: Testing the Relationship between Paleoenvironments and Three Theropod Clades". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): e0147031.

Sales, Marcos (2017). "Contribuições à paleontologia de Terópodes não-avianos do Mesocretáceo do Nordeste do Brasil" (in Portuguese). 1. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: 54.

Sales, Marcos A.F.; Schultz, Cesar L. (2017-11-06). "Spinosaur taxonomy and evolution of craniodental features: Evidence from Brazil". PLOS ONE. 12 (11): e0187070.

Sánchez-Hernández, B., M. J. Benton, and D. Naish. 2007. Dinosaurs and other fossil vertebrates from the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous of the Galve area, NE Spain. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 249:180-215

Sayão, Juliana; Saraiva, Antonio; Silva, Helder; Kellner, Alexander (2011). "A new theropod dinosaur from the Romualdo Lagerstatte (Aptian-Albian), Araripe Basin, Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31: supplement 2: 187.

Sereno, P.C.; Beck, A.L.; Dutheuil, D.B.; Gado, B.; Larsson, H.C.; Lyon, G.H.; Marcot, J.D.; Rauhut, O.W.M.; Sadleir, R.W.; Sidor, C.A.; Varricchio, D.; Wilson, G.P.; Wilson, J.A. (1998). "A long-snouted predatory dinosaur from Africa and the evolution of spinosaurids". Science. 282 (5392): 1298–1302.

Serrano-Martínez, Alejandro; Vidal, Daniel; Sciscio, Lara; Ortega, Francisco; Knoll, Fabien (2015). "Isolated theropod teeth from the Middle Jurassic of Niger and the early dental evolution of Spinosauridae". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Sues, H.D.; Frey, E.; Martill, D.M.; Scott, D.M. (2002). "Irritator challengeri, a spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 535–547.

Witmer, L.M. 1995.The Extant Phylogenetic Bracket and the Importance of Reconstructing Soft Tissues in Fossils. in Thomason, J.J. (ed). Functional Morphology in Vertebrate Paleontology. New York. Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–33.

Witton, Mark P. (2018-01-01). "Pterosaurs in Mesozoic food webs: a review of fossil evidence". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 455 (1): 7–23.

Xu, X.; Currie, P.; Pittman, M.; Xing, L.; Meng, Q.; Lü, J.; Hu, D.; Yu, C. (2017). "Mosaic evolution in an asymmetrically feathered troodontid dinosaur with transitional features". Nature Communications. 8: 14972.

#Irritator challengeri#Irritator#Dinosaur#Spinosaur#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Megalosaur#Water Wednesday#Piscivore#South America#Cretaceous#Spinosaurine#prehistoric life#paleontology#prehistory#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

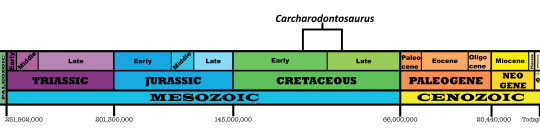

Carcharodontosaurus

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Jagged Tooth Reptile

First Described By: Stromer, 1931

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Carnosauria, Allosauroidea, Allosauria, Carcharodontosauria, Carcharodontosauridae, Carcharodontosaurinae

Referred Species: C. saharicus, C. iguidensis

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Carcharodontosaurus lived from about 112 million years ago until 93.5 million years ago, from the Albian through the Cenomanian of the Early to Late Cretaceous

Carcharodontosaurus lived in a wide variety of environments - the Continental Intercalaire Formation of Algeria and Tunisia, the Chenini Member of the Aïn el Guettar Formation of Tunisia, the Bahariya Formation of Egypt, the Mut Member of the Quseir Formation, the Aoufous and Ifezouane Formations of Morocco, and the Tagrezou Sandstone and Echkar Formations of Niger.

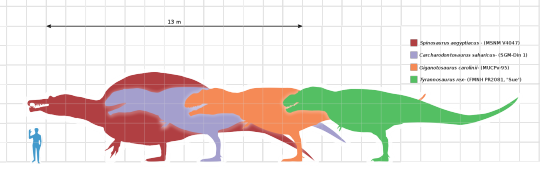

Physical Description: Carcharodontosaurus was a very large theropod dinosaur - one of the biggest known, in fact - and a Carnosaur, a group of predatory dinosaurs which were extremely common from the Jurassic through the early-middle Cretaceous. Like other large meat eating dinosaurs, they had short arms, strong necks, and huge heads - meaning, they manipulated and interacted with their environment primarily through their heads, and relied on their jaws for capturing and taking down prey. Carcharodontosaurus was one of the longest predatory dinosaurs, ranging up to 13.3 meters long, and weighing between 6.2 and 15.1 tons. A good chunk of that length was made up of the skull of Carcharodontosaurus, which was truly enormous - as long as 2 meters.

That mouth was filled with long, sharp, serrated teeth, reaching up to 8 inches in length - these teeth are so distinctive that the animal was named for them! Carcharodontosaurus had a brain very similar to that of its earlier relative, Allosaurus, and seemed to have a well developed sense of smell and sight. Still, it was of typical intelligence for a non-avian dinosaur. It had a triangle inner ear configuration like Allosaurus and other nonavian reptiles, but the brain projected into the area of the canals like the situation found in other theropods, birds, and pterosaurs.

Size Comparison (Carcharodontosaurus in purple, second from the left) by Dinoguy2, CC BY-SA 3.0

Carcharodontosaurus was fairly long in body besides the huge head, with a long tail and long torso. Its legs were fairly well developed, but not as thickly muscled as those found in, say, Tyrannosaurs and Abelisaurs. It also probably had a crest on its head, which would have been helpful in display. As a large animal, it is very unlikely for it to have had feathers - if it did, they would have been solely ornamental in function (it is important to note, of course, that its close relative Concavenator may have had proto-wings, but this is a hotly debated topic, and Concavenator was smaller than Carcharodontosaurus by a lot).

Diet: Carcharodontosaurus would have been a hypercarnivore, feeding primarily on other larger animals, especially sauropods.

Behavior: Carcharodontosaurus was an extremely common animal in North Africa during the middle Cretaceous, and so it isn’t unlikely that it lived at least in family groups, potentially forming mobs to take down particularly large sauropod prey. It would have used its jaws to take down food, opening them wide and using the teeth to slash at prey and leading to it bleeding out so that Carcharodontosaurus could proceed to feeding. It would have relied on it’s decent sense of smell to find food, using it to help pinpoint food from far and wide in its environment. It could even lift animals weighing up to a thousand pounds with its jaws, so if it didn’t want to work together in a group of bring down larger food, it could grab a variety of snacks just to have on its own.

If Carcharodontosaurus lived in groups, they weren’t the most congenial of family arrangements - there are fossils of Carcharodontosaurus that indicate it was wounded with something that made circle punctures in the bone, which sounds about right for fighting with another Carcharodontosaurus. Still, it seems at least somewhat likely that this animal would have cared for its young in some form.

By Fred Wierum, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: Carcharodontosaurus lived in a variety of ecosystems across North Africa in the middle Cretaceous, in a variety of different environments. It lived in open floodplains, as well as near mangrove forests, but not as associated with wet ecosystems as Spinosaurus was. It would have fed almost entirely on land-based prey, and thus, didn’t come into competition with Spinosaurus very frequently.

Carcharodontosaurus lived in the Bahariya Formation of Egypt, with Spinosaurus, Sigilmassasaurus, Deltadromeus, and Bahariasaurus as other theropods. There were huge titanosaurs for it to feed on, namely Aegyptosaurus and Paralititan. This was an environment filled with confirers, water ferns, and tree ferns, as the climate switched between the swamp to a drier environment due to dramatic seasonal fluctuations.

It was also found in the Mut Member of the Quseir Formation, a more muddy environment than the Bahariya Formation; though Carcharodontosaurus lived alongside Spinosaurus, it’s uncertain what Carcharodontosaurus would have eaten - no major land animals are known from this environment.

Carcharodontosaurus in Tunisia is known from the Chenini Member of the Aïn el Guettar Formation, which was also a water based environment with Spinosaurus and many fish, but the other dinosaurs present - which would have probably been Carcharodontosaurus’ main source of food - are not formally named.

Also in Tunisia, and Algeria, Carcharodontosaurus was in a drier, pebbled environment, probably at least something of a scrub environment, though there were some cycads and conifers. Here it lived alongside animals like the sailed sauropod Rebbachisaurus, and the weird theropod Elaphrosaurus. There was also the large crocodilian Sarcosuchus, and many different reptiles and fish.

By Scott Reid

In Morocco, Spinosaurus is known from the famous Kem Kem Beds - a flooding river ecosystem, with distinct dry and wet seasons. The Aoufous was the earlier environment, followed by the Ifezouane environment. Here, Carcharodontosaurus lived alongside Spinosaurus, Deltadromeus, and Sigilmassassaurus - as before - but also other theropods like Sauroniops and Inosaurus. Rebbachisaurus was here too, a good source of food for Carcharodontosaurus. There were large fish, crocodilians, and pterosaurs like Alanqa, Siroccopteryx, Colobrhynchus, and Xericeps - other decent sources of food, if only Carcharodontosaurus can catch them.

Carcharodontosaurus, finally, is known from the Echkar Formation of Niger. Here, it lived alongside Spinosaurus and Bahariasaurus, as well as Spinostropheus and Rugops, and the large sauropod Rebbachisaurus and Aegyptosaurus - a great place for Carcharodontosaurus to find food.

Other: Carcharodontosaurus, like Spinosaurus, was actually lost during World War II, because nazis literally ruin everything. Fossils of it have been found since, and luckily it doesn’t seem to be quite as much of a mystery as our old sailback friend.

Species Differences: C. saharicus comes from more northern locations of Africa, while C. iguidensis is more from the south. They also have somewhat differently shaped jaws and brains.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Apesteguía, S.; Nathan D. Smith; Rubén Juárez Valieri; Peter J. Makovicky (2016). "An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". PLoS ONE. 11 (7): e0157793.

Amiot, R., X. Wang, C. Lécuyer, E. Buffetaut, L. Boudad, L. Cavin, Z. Ding, F. Fluteau, A. W. A. Kellner, H. Tong, and F. Zhang. 2010. Oxygen and carbon isotope compositions of middle Cretaceous vertebrates from North Africa and Brazil: Ecological and environmental significance. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 297(2):439-451

Bassoullet, J.-P. and J. Iliou. 1967. Découverte des Dinosauriens associés à des Crocodiliens et des Poissons dans le Crétacé inférieur de l'Atlas saharien (Algérie) [Discovery of dinosaurs associated with crocodilians and fish in the Lower Cretaceous of the Saharan Atlas (Algeria)]. Société Géologique de la France, Comptes Rendus Sommaire des Sciences 1967:294-295

Bouaziz, S., E. Buffetaut, M. Ghanmi, J.-J. Jaeger, M. Martin, J.-M. Mazin, and H. Tong. 1988. Nouvelles découvertes de vertébrés fossiles dans l'Albien du sud tunisien [New discoveries of fossil vertebrates in the Albian of southern Tunisia]. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 8e série 4(2):335-339

Brusatte, S.L. and Sereno, P.C. (2007). "A new species of Carcharodontosaurus (dinosauria: theropoda) from the Cenomanian of Niger and a revision of the genus." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 27(4).

Buffetaut, E. 1989. New remains of the enigmatic dinosaur Spinosaurus from the Cretaceous of Morocco and the affinities between Spinosaurus and Baryonyx. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Monatshefte 1989(2):79-87

Calvo, J.O.; Coria, R.A. (1998). "New specimen of Giganotosaurus carolinii (CORIA & SALGADO, 1995), supports it as the largest theropod ever found" Gaia. 15: 117–122.

Churcher, C. S., and D. A. Russell. 1992. Terrestrial vertebrates from Campanians strata in Wadi el-Gedid (Kharga and Dakleh Oases), western desert of Egypt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 12(3, suppl.):23A

Deparet, C.; Savornin, J. (1925). "Sur la decouverte d'une faune de vertebres albiens a Timimoun (Sahara occidental)". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris. 181: 1108–1111.

Deparet, C.; Savornin, J. (1927). "La faune de reptiles et de poisons albiens de Timimoun (Sahara algérien)". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 27: 257–265.

Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011

Lapparent, A. F. d. 1951. Découverte de Dinosauriens, associés à une faune de Reptiles et de Poissons, dans le Crétacé inférieur de l'Extrême Sud tunisien [Discovery of dinosaurs associated with a reptile and fish fauna in the Lower Cretaceous of extreme southern Tunisia]. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences à Paris 232:1430-1432

Lapparent, A. F. d. 1953. Gisements de Dinosauriens dans le "Continental intercalaire" d'In Abangarit (Sahara méridional) [Dinosaur localities in the "Continental Intercalaire" of In Abangarit (southern Sahara)]. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences à Paris 236:1905-1906

Lapparent, A. F. d. 1957. The Cretaceous dinosaurs of Africa and India. Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India 2:109-112

Lapparent, A. F. d. 1959. Les dinosauriens du Sahara central [The dinosaurs of the central Sahara]. Comptes Rendus de la Société Géologique de France 1959:87

Lapparent, A. F. d. 1960. Les Dinosauriens du "Continental intercalaire" du Saharal central [The dinosaurs of the "Continental Intercalaire" of the central Sahara]. Mémoires de la Société géologique de France, nouvelle série 39(88A):1-57

Larsson, H.C.E. 2001. Endocranial anatomy of Carcharodontosaurus saharicus (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) and its implications for theropod brain evolution. pp. 19–33. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Ed.s Tanke, D. H., Carpenter, K., Skrepnick, M. W. Indiana University Press.

Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press.

Russell, D. A. 1996. Isolated dinosaur bones from the Middle Cretaceous of the Tafilalt, Morocco. Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 4e série, section C 18(2-3):349-402

Schlüter, T., and W. Schwarzhans. 1978. Eine Bonebed-Lagerstätte aus dem Wealden Süd-Tunisiens (Umgebung Ksar Krerachfa) [A bonebed from the Wealden of southern Tunisia (near Ksar Krerachfa)]. Berliner Geowissenschaften Abhandlungen A 8:53-65

Seebacher, F. (2001). "A New Method to Calculate Allometric Length-Mass Relationships of Dinosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 51–60.

Sereno, P. C.; Dutheil, D. B.; Iarochene, M.; Larsson, H. C. E.; Lyon, G. H.; Magwene, P. M.; Sidor, C. A.; Varricchio, D. J.; Wilson, J. A. (1996). "Predatory Dinosaurs from the Sahara and Late Cretaceous Faunal Differentiation". Science. 272 (5264): 986–991.

Smith, J. B., M. C. Lamanna, K. J. Lacovara, P. Dodson, J. R. Smith, J. C. Poole, R. Giegengack and Y. Attia. 2001. A giant sauropod dinosaur from an Upper Cretaceous mangrove deposit in Egypt. Science 292:1704-1706

Stromer, E. 1915. Results of research trips by Prof. E. Stromer in the deserts of Egypt. II. Vertebrate remains of the Baharîje stage (lowest Cenomanian). 3. The original of the Theropod Spinosaurus aegyptiacus nov. gen., nov. spec. Treatises of the Royal Bavarian Academy of Sciences Mathematical-physical class Treatise 28 (3) : 1-31

Stromer, E. (1931). "Wirbeltiere-Reste der Baharijestufe (unterestes Canoman). Ein Skelett-Rest von Carcharodontosaurus nov. gen." Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung, 9(Neue Folge): 1–23.

Therrien, F.; Henderson, D.M. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 108–115.

#Carcharodontosaurus#Dinosaur#Carnosaur#Palaeoblr#Carcharodontosaurus saharicus#Carcharodontosaurus iguidensis#Dinosaurs#Theropod Thursday#Carnivore#Africa#Cretaceous#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile

443 notes

·

View notes