#WPA/FAP

Text

Q&A with Mary Ann Calo

The author of African American Artists and the New Deal Art Programs discusses the significance of New Deal art projects, the Harlem Artists' Guild, and more.

How were the New Deal art projects significant to the history of African American art?

Historians have tended to think of the New Deal art projects as having had a generally positive effect on the development of African American art. The immediate purpose of the projects was to provide financial relief in the form of employment for artists during the Depression. In practical terms, the projects gave Black artists who were eligible time to work and unprecedented access to materials and instruction. There was strong consensus among participating artists that opportunities offered by the art projects at least partially redressed the chronic disadvantages and isolation they had faced. These art projects thus functioned as mechanisms to advance their careers and facilitate their entry into the mainstream of American cultural life.

My primary focus is on the programs of the Federal Art Project (FAP), the largest New Deal arts initiative, administered by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) from 1935 to 1943. The FAP was a branch of Federal Project Number One, which encompassed multiple government-supported initiatives to provide work relief not only for artists but also for writers and creative practitioners in theater and music. In a departure from historical accounts that concentrate on individual accomplishments within the FAP, I shift the analytical focus to educational projects such as Community Art Centers. These facilities, some of which were established to serve racially segregated populations, combined opportunities for technical instruction and art appreciation with a social service mentality. While centers in Harlem and Chicago have long enjoyed public visibility and distinction, I expand the discussion to include lesser-known initiatives in the South, noting the vast differences between specific locales.

The book moves beyond accounts of artists who personally benefitted from the projects, and the works they produced, toward broader issues informed by the uniqueness of Black experience and circumstances. I argue that the revolutionary vision of the New Deal art projects must be understood in the context of access to opportunity mediated by the realities of racism and segregation.

Were the federal art projects fair? Were they equitable?

While other divisions of Federal One, such as theater and writing, had units dedicated to African American culture, by design the FAP was “race blind.” But historians of the New Deal visual art programs have long had to reconcile optimism about expanded opportunity and nondiscrimination with the fact of low African American participation numbers, especially in the creative divisions. I examine the skill and relief requirements of the FAP in terms of their impact on choices open to African American artists and the emphasis within project administration on the primacy of educational, rather than creative, work in the Black community.

The elaborate skill classification system of the FAP, which distinguished between various levels of preparedness to perform certain kinds of work, contained obvious (but unacknowledged) pitfalls for African American artists. For example, individuals seeking to qualify for the creative divisions, which would provide support for time spent in the studio, were asked to furnish information on their training as artists and their exhibition history. This was a challenge for Black artists who lacked opportunities to attend art school or regularly show their work. Administrators were preoccupied with ensuring equal access to the benefits of the projects but disinclined to challenge existing norms of segregation or examine their consequences.

How crucial are archives and documents in writing African American art history?

Archival repositories and primary documents have always been essential to writing the history of New Deal art projects. Accounting for African American experience within them is hindered, as in many areas of American cultural history, by insufficient interest and a fragmented archival landscape. Because Black artists were largely overlooked during the documentary phase of early research on the New Deal art projects, when statistics were gathered and standard histories were being written, the task of tracking and sorting relevant data has been an ongoing challenge. And while a great deal of progress has been made in recent years, participation and program records are dispersed and not easily aggregated for purposes of analysis.

How did the Harlem Artists' Guild function, and to what extent was it a Popular Front organization?

On its face, the Harlem Artists Guild’s (HAG) was a prototypical artist advocacy organization of the New Deal era. But its agenda was also rooted in discourses about race and culture that had evolved decades earlier. In that sense, while emblematic of the impulse to unite and organize in the 1930s, the HAG existed in a different space of cultural meaning and significance.

The activities of the HAG can, to an extent, be located within the context of Popular Front ideology, which emphasized coalition building in the interest of maximizing the impact of progressive forces. Traditionally, New Deal historians have tended tend to think of the HAG as an offshoot of the Artists’ Union (AU). This suggests that it derived its energy from the dominant activist organization of the majority culture. I describe the nature of its alliances with groups central to this period, such as the AU and the American Artists’ Congress (AAC), but also with the National Negro Congress (NNC) and local civic organizations. This is consistent with more recent historical approaches that raise questions about the extent to which civil rights organizations such as the NNC may have intersected with this cultural energy and stimulated it.

African American Artists and the New Deal Art Programs: Opportunity, Access, and Community is now available from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09493-9.html. Save 30% w/ discount code NR23.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

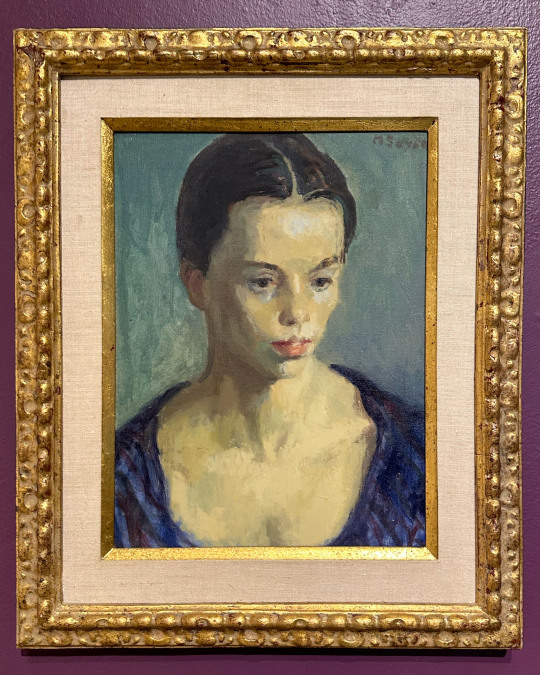

Moses Soyer’s oil painting, Young Girl, is one of the works on view in A New Deal: Artists of the WPA from the CMA Collection at Canton Museum of Art. The exhibition is a reminder of one of the best social programs ever created by the US government and the positive impact it had on the country during one of its hardest periods.

From the museum about the exhibition-

Against the backdrop of severe economic strife caused by the Stock Market Crash of 1929, President Franklin Roosevelt created the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which put roughly 8.5 million Americans, including more than 173,000 men and women in Ohio, to work building schools, hospitals, roads and more. Within the WPA was The Federal Art Project (FAP) which provided employment for artists to create art for municipal buildings and public spaces. The FAP had a non-discrimination clause that meant it attracted and hired artists of color and women, who previously received little attention in the art world. The only guidance the government offered about subject matter was to depict the “American scene” and stipulated no nudity or political issues. The goal was for artists to help the United States develop its own distinct American style of art, especially as artists in other parts of the world were forbidden freedom of expression and ordered to create artworks that projected the beliefs of their governments.

Though the WPA artists in the United States shared the common goal of capturing life in all its variety and promoting national pride, they each had different approaches, and many modified their typical subject matter to fit whatever project they were assigned. The arts before and after the New Deal relied on private patronage and the philanthropy of wealthy and elite institutions: galleries, museums, dealers. But during the WPA, art wasn’t a luxury good, it was seen as an essential part of our democracy. Artists were seen as professional workers who were making important and significant contributions to American life. The artworks made under the WPA became the collection of the American people and were put in public collections – hospitals, schools, post offices, housing projects, etc. – ensuring they were part of communities. The arts were seen as an important part of a democratic society and the American way of life, with a richness of experience and accessibility to culture.

While artists were offered opportunities through the WPA, they were far from immune to the distress caused by the Depression, and many still struggled to make a living. Will Barnet detailed a bleak scene he came across, saying:

“It was like a war going on. There were bread lines and men lined around three, four, five, six blocks waiting to get a bowl of soup. It was an extraordinary situation. And one felt this terrible dark cloud over the whole city.”

Moses Soyer also described the hardships artists experienced, saying,

“Depression–who can describe the hopelessness that its victims knew? Perhaps no one better than the artist taking his work to show the galleries. They were at a standstill. The misery of the artist was acute.”

The FAP supported the creation of thousands of works of art, including more than 2,500 murals that can still be seen in public buildings around the country. The FAP also supported art education and outreach efforts, including traveling exhibitions and art education programs for children. The WPA and FAP had a significant impact on the American art scene, and many of the artists who participated in the program went on to become important figures in the art world.

A New Deal: Artists of the WPA from the CMA Collection highlights the lives of artists from our Permanent Collection who worked for the WPA, and in doing so, fostered resilience for a struggling nation. You will learn about the projects they worked on, the subjects they were interested in, and how their own lives were affected by the Depression. Each of these artists helped to foster the nation’s spirit and prove that even in the darkest of times, art serves as a uniting force to collectively lead people into a brighter future.

And about Moses Soyer and his painting from the museum-

The Depression set the mood for most of Soyer’s art expression, and his portraits of people seem to be preoccupied with a sad secret. His portraits were often of solitary fi gures, using professional models or his friends, capturing in these paintings the spirit of his sitters, their dreams or disillusionment. He is best known for his introspective fi gure paintings of weary, melancholy women in muted colors, matching the mood of his sitters with the pigment in his paint. He was inspired by artist Edgar Degas, who used color expressively.

On the museum’s website you can find both the artwork on display for the exhibition and also a gallery of the museum’s entire collection organized into several categories.

#Moses Soyer#Art#Canton Museum of Art#Art History#Art Shows#Canton Art Shows#Works Progress Administration#Drawing#Federal Art Project#President Franklin D. Roosevelt#Franklin D. Roosevelt#Government Programs#Great Depression#History#Ohio Art Shows#Painting#The New Deal#WPA

0 notes

Text

Finding Lost Florida Art at the Chicago Century of Progress, 1933-1934

January 2, 2015 by Fred Frankel

Imagine how you might feel if national icons like John Trumbull’s painting of The Declaration of Independence or Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware were lost. On a state level, that’s exactly what happened in Florida. In 1931 the state sponsored an art competition to find six artists to paint large murals depicting important events in the states history for the Florida building at the Chicago Century of Progress. The murals, eventually to be placed in the capitol in Tallahassee,were commissioned, painted, exhibited and then lost. This is the story of those lost paintings and the recent discovery of works submitted for the competition.

It was a difficult time for Floridians: the Florida land boom ended in 1925 when real estate prices crashed; the hurricane of 1926 flattened Miami, and the Depression straight lined tourism.

When the state legislature met in 1931 they wanted to stimulate tourism. They learned that Chicago planned to celebrate the one hundredth anniversary of its incorporation with a World’s Fair: the Chicago Century of Progress. All states were invited. Florida and eleven others, including California and Georgia, decided to participate in a great central quadrangle, the Court of States. Here was a unique chance to tell the country about the Sunshine State.

In 1931 Florida was still a relatively small state with a population of 1.5 million and, with the exception of Osceola and the Seminole Indian Wars, unfamiliar with the national stage. That would change in Chicago. The state would go all out: even minting a small coin that proclaimed: “Florida where summer spends the winter.”

The Florida exhibit included a half acre orange grove, dozens of palm trees, an outdoor garden with wild orchids, a lily pond, and a Seminole village. Inside, the two floored pavilion designed by Phineas Paist, the architect of Coral Gables, featured a Spanish courtyard, its sky crossed by a flight of ibis, dioramas of state industries, the sculpture, Spirit of Florida, by George Ganiere, professor of sculpture at Stetson University, paintings of the sky lines of the larger cities, and six murals, each ten by ten feet, depicting the states’ history.

It all began in September of 1931 when the state legislature authorized a Florida exhibit at the Chicago fair. Governor Doyle Carlton appointed six senators and six representatives to the Florida Century of Progress Commission with Senator W.C. Hodges as chairman,

The commission began a statewide campaign to raise $250,000 for the exhibit and appointed a Florida Century of Progress Jury to find artists of recognized ability to execute paintings of important episodes in Florida’s history. The jury consisted of Mrs. Eve Alsman Fuller, of St. Petersburg, chairman, Mrs. Doyle Carlton, Mrs. Cary Landis, wife of the Attorney General, Senator Hodges, and sculptor C. Adrian Pillars of Jacksonville and Sarasota.

The state of Florida commissioned Pillars for sculptures of Confederate General Kirby Smith and John Gorrie, the inventor of air conditioning, that represent Florida in the United States Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C. Pillars’ sculpture, Life, a memorial to Florida’s dead in World War I, stands in Memorial Park in Jacksonville.

Eve Fuller was president of the Florida Federation of Art (FFA) and director of the Florida Art Project (FAP) sponsored by the Federal governments Works Progress Administration (WPA). The FFA, with both amateur and professional artist members, had clubs in almost every major city in the state. During the Depression the FAP put unemployed professional artists back to work.

Mrs. Fuller invited all artists working for the FAP to enter the competition. Members of the FFA were notified and invited to participate. On August 10, 1932 Senator Hodges issued a press release that appeared in newspapers around the state the following day with, “An invitation to all artists who live in Florida or who paint Florida scenes to submit paintings for use in the states exhibit at the World Fair in Chicago next year.”

Paintings were to be submitted in categories: Discovery, Exploration, Christianization, Colonization, Seminole War, and Reconstruction. Artists could enter one painting in each category. The paintings were to be of uniform size, 30 by 30 inches, in simple frames, and signed on the back by the artist.

The jury met at the Ringling Museum of Art in early November 1932. Mrs. Fuller as chairman of the jury expressed pleasure at the interest in the contest by so many of the artists throughout the state and in the character of the work submitted.

Some of the preliminary paintings for the competition have survived and illustrate the mural work done by the winning artists and those awarded honorable mention.

The winning artists were:Addison Burbank for Discovery: Ponce De Leon taking possession of the land for Spain. Burbank was born in California, the son of W. F. Burbank, founder of the Oakland Tribune. In 1926 after art study in Europe he had a solo exhibition of his paintings at the Ferargil Galleries in New York City. Burbank later moved to Miami. The St. Augustine Record, January 13, 1933, quotes Burbank on his visit to St. Augustine, “Through your courtesy Mrs. Burbank and I had the pleasure of visiting the Arts Club (of St. Augustine) Friday evening and viewing the splendid work of yourself and fellow members. We of the Miami Art League envy you your beautiful home and splendid facilities for study and play. St. Augustine is a mine for artists, and we hope the Arts Club will prove the nucleus of a famous art center. Our visit to St. Augustine was in search of material for the mural of Ponce de Leon’s discovery of Florida, for which I received the first award in the state competition held in November. Mrs. Underwood of the Historical Society gave me great help. Mr. Burbank is painting the murals for the Florida exhibits in the Century of Progress Exposition.” Burbank’s mural is lost.

Max Bernd-Cohen for Exploration: DeSoto explores the west coast of Florida. In 1931 Max Bernd-Cohen was one of the first instructors at the Ringling School of Art. Before coming to Sarasota Bernd-Cohen spent two years as a guest lecturer at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London, England. He taught at the Imperial University, Sapporo, Japan and was chairman of the art department at Florida Southern University in Lakeland. Art lovers from nearby cities attended his popular lectures at the Ringling School, and he was in demand as a speaker throughout the state of Florida. In 1955 he was honored with inclusion, in the Ringling Museum of Art exhibit, Fifty Florida Artists.

Wallace W. Hayn for Christianization: the Spanish building of the first missions in the state. Hayn, like his art, has been lost to history.

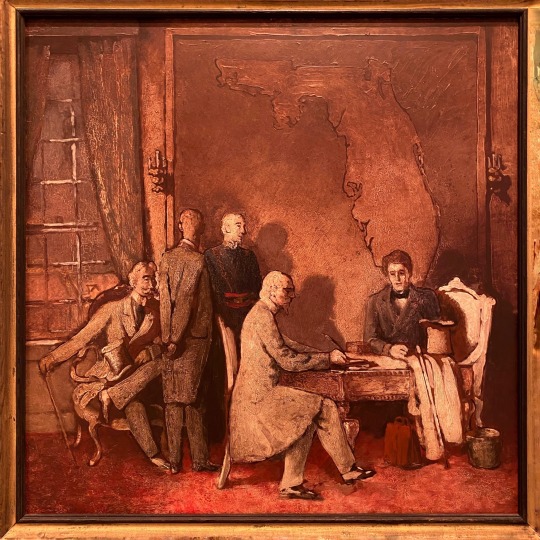

Chester J. Tingler for Colonization: Andrew Jackson taking over Florida for the United States. Chester Tingler was an important Miami muralist. Born in Sweden, he grew up in Buffalo, New York where his drawings for the Albright Art Gallery won him a one year art scholarship. After study at the Art Students’ League in New York City, Tingler was employed for some years as scenic and costume designer for Broadway shows produced by Flo Ziegfeld and the Schuberts. In 1917 he received the Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney award for mural painting. Tingler moved to Miami in 1922 and was later employed by the WPA and the FAP as supervisor of the mural art project for the Miami district. Tingler did murals for the Miami High School library, the Clewiston Airport, Shenandoah Junior High and Ponce de Leon High School. Tingler was named Artist of the Year in 1944-1945 by the Miami Women’s Club and the American Artists Professional League. He was an art instructor with the Terry Art Institute and a regular exhibitor at the Mirell Gallery in Coconut Grove and the Washington Art Galleries of Miami Beach.

Eleanor King was just twenty-three when she painted General Jackson Besieging Media de Luna of San Carlos for the state competition. One of the youngest artists to enter, she did not win, though her painting made the finals, where King lost to Chester Tingler. The Pensacola Journal noted, “Miss King is in receipt of a letter from Mr. Tingler asking her to help him with his painting in the matter of uniforms and accoutrements, both of American and Spanish soldiers. . . . In response . . . the young artist has made it clear that, should she assist in this work, she would expect recognition. She spent many months over her painting, and had the personal assistance of Julian Yonge, authority on Florida history. . . . It was never clear to Pensacola how it could be possible to present Florida historically without giving Pensacola a leading place in portraiture. . . . Is Mr. Tingler to paint a picture of Pensacola’s past? And if he is, will this young artist assist him? Pensacola will learn of this with interest, and every effort should be made to assure that both she and Pensacola are properly recognized in the painting that is to depict the early history of Florida.”

The Pensacola Journal of April 6, 1934, “Eleanor King, young Pensacola artist, is rapidly gaining more than local distinction. This scene was painted in competition for art work to be placed in the Florida exhibit at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago and received special mention. Miss King has exhibited in New York at the National Academy, and in Birmingham, Alabama at the annual exhibit of the Southern States Art League, her work attracted much attention….”

Later King married Lawrence Salley and moved to Tallahassee. Mrs. Salley was in New York City in 1939 for the New York World’s Fair. A letter home to her family is quoted in the Pensacola Journal, May 2, 1939, “The Montross Gallery on Fifth Avenue is going to handle my work all the time and plans to open their season in the fall with a one man show of my watercolors, thirty of them.” The Ferrigil Galleries on 57th Street carried her oils, landscapes, and seascapes. King did portraits of many prominent Floridians including historian Caroline Brevard, hung in the school named for her in Tallahassee; a portrait of Chief Justice Fred Davis, hung in the Supreme Court in Tallahassee; and a portrait of William Sheats, who for twenty years, was state superintendent of schools in Florida, hung in the education room of the state capitol.

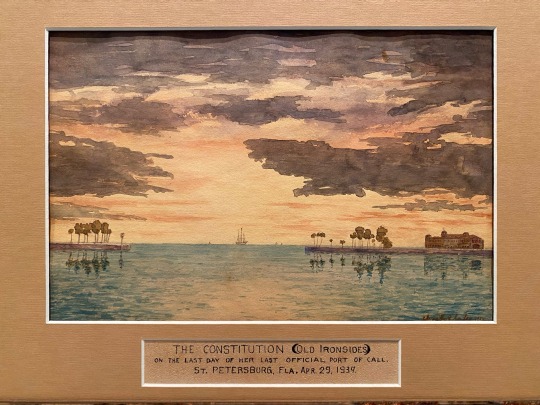

Mark Dixon Dodd for Seminole War: Osceola driving a knife through the peace treaty at Moultrie Creek. Mark Dodd moved from New York City to St. Petersburg in 1925. He soon became a prominent member of the city’s art community. Dodd opened the Mark Dixon Dodd School of Art on Beach Drive in 1930. In 1936, as his reputation as an artist and teacher grew, Dodd designed and built fifteen homes on Coffee Pot Bayou. In each he placed one of his paintings, usually anchored to the wall above the fireplace. Dodd later became head of the art department at St. Petersburg Junior College.

George Snow Hill for Reconstruction: Governor Bloxham, Hamilton Disston and the Florida Land Sale. George Snow Hill and his artist wife Polly Knipp were two of the most talented artists to work in Florida. Hill was the son of Captain George R. Hill, a longtime resident of St. Petersburg. After graduation from Syracuse University, George and Polly Knipp met, and were married, in Paris. The couple spent several years painting in Europe. On their return home both were acclaimed as among the most brilliant of young American artists, with an invitation to exhibit at the 1932 Olympic International Exhibit in Los Angeles. Competing against 1,100 paintings from thirty-two countries, George Snow Hill won honorable mention for his St. Petersburg, Florida scene, Surf Fishing. Hill worked in the tradition of American muralist Thomas Hart Benton. He should be remembered as one of Florida’s premier muralists, his work evoking and caricaturing the innocence and joy of life in Florida.

Denman Fink, chairman of the Department of Art at the University of Miami, was awarded a commission for “Lunettes” showing the skylines of Florida’s larger cities. Denman Fink made important contributions to art development in Florida. An illustrator and muralist, Fink was head of the art department at the University of Miami for twenty-five years. Fink first came to Miami in 1920 to complete a series of paintings on Florida subjects for a volume of verse by his nephew George E. Merrick. He moved permanently to Miami in 1924, joining Merrick in his development of Coral Gables. With Phineas Paist, Fink helped design plans for the city, its entrances, fountains, plazas’ and the Venetian Pool. In 1938 Fink won a federal competition to paint a large mural for the court house in downtown Miami. The mural, Law Guides Florida Progress, depicts the development of Florida from the days of the Seminoles to the evolution of law. When he died the Miami Herald, June 8, 1956 noted his passing, “Coral Gables is Fink’s Monument. Denman Fink has folded up his easel and laid aside his design board for the last time… the community has lost one of its outstanding citizens.”

Honorable mentions were awarded to Bernd-Cohen, Mark Dodd, Wallace Hayn, Chester Tingler, Emmaline Buchholz, Polly Knipp Hill, and Phillip Schlamp.

Emmaline Buchholz was instrumental in founding the Gainesville Association of Fine Arts in 1923, and in 1927, the Florida Federation of Art. She was the Federation’s first president and the first lady of Florida art. Buchholz remained an important figure in art appreciation and development in Gainesville, and throughout Florida, for many years. Her painting of George Washington, after Gilbert Stuart, hangs in the Florida House of Representatives chamber in Tallahassee.

Polly Knipp Hill was known nationally as one of America’s best etchers. Her etchings were chosen for exhibition in the Fine Prints of the Year, an annual collection which showed the 50 best prints made in America. She depicted, with great success, typical scenes in and around St. Petersburg, fishing from the bridge at Johns Pass, picnicking on the beach, local scenes concerned with people enjoying life in St. Petersburg.

A native of Kentucky, Philip Schlamp moved to Miami in 1926 where he and his wife Ethel were active members of the Miami art community. Ethel Schlamp was co-founder of the Miami Art League. The Miami Herald noted, “A portrait and mural artist, Philip Schlamp spent a good many years… studying historical mural painting, portraiture and sculpture. He is probably best known throughout Florida for an 18 by 10 foot historical mural, depicting Ponce de Leon returning to Spain, to announce the discovery of the land of flowers. The mural was painted for the Florida office of a Chicago firm, and was later shipped to Chicago and hung there….”

When the fair ended in October 1934 it was the beauty of the Florida exhibit, its ability to project the warmth of the state, and the art that stole the show. In the Official Guide Book World’s Fair 1938, Florida was the only state with a photograph of its interior court yard. The Official Guide noted, “Mural paintings of the history of Florida surround the gallery. Osceola, the war chief of the Seminoles, is shown driving his knife through the treaty which would deprive his people of independence.” Florida was one of the few states to use original art to enhance their exhibit. That made a difference.

If you’ve been to a great museum like New York’s Metropolitan, or Sarasota’s Ringling, you can imagine what we’ve lost. Six canvases, huge by today’s standard and, from what we’ve seen of the preliminary painting—beautiful–rivaling the work of John Trumbull or Emanuel Leutze. Happily, some of the smaller paintings have survived.

The commissioner in charge of Federal and state participation at the fair, H. F. Miller, sent the following letter to Senator Hodges: “Yesterday we had in the grounds over a quarter of a million people, and of this 12, 000 an hour passed through your beautiful exhibit. This is a big load. If we had not checked the figures from time to time, we could be inclined to doubt the evidence of our own eyes and observation. It simply goes to prove that if you put on a good show people will come regardless of the Depression….Florida has made an outstanding contribution to the success of the World’s Fair.”

Phineas Paist, George Ganiere and the award winning Florida artists had done well. In 1933 over nine million people visited the Florida exhibit. In 1934 over thirteen million came. Florida experienced the best tourist season in years.

0 notes

Photo

Sargent Claude Johnson was a ceramicist, painter, and lithographer based out of North Beach, San Francisco in the 1930s. Johnson, who was of Black and Cherokee heritage, is remembered for his soul-stirring sculptures and his commitment to creating self-affirming images of Black people. This graceful terracotta figure shows the influence of the Harlem Renaissance and the call for the celebration and integration of African ancestral traditions as expressed by Alain Locke. Johnson said he was “aiming to show the natural beauty and dignity” of African Americans, not to a white audience, but to themselves."

From 1937 to 1939 Johnson worked for the WPA/FAP (The Works Progress Administration/ Federal Art Project) which created work relief for artists during the Great Depression. He created large-scale artworks for the WPA such as the decorated interior of the San Francisco Maritime Museum, among others, some of which can still be seen today.

Like many artists in the Bay Area art scene, Johnson and his contemporaries drew inspiration from non-European art such Indigenous arts of the Americas and the Pacific, in addition to African art. They also looked to artists such as Diego Rivera, whose figurative techniques and illustration of social issues spoke to new ways of expressing the Black experience.

Are you familiar with any artworks created by other Black artists for the WPA? Let us know in the replies!

In honor of Black History Month, and in conjunction with the exhibition John Edmonds: A Sidelong Glance, we are highlighting contemporary artists in our collection whose work speaks to the complexity and beauty of Black American heritage.

Sargent Claude Johnson (American, 1888-1967). Untitled (Standing Woman), ca. 1933-1935. Terracotta, paint, surface coating. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Estate of Emil Fuchs and Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Steinhauer, by exchange, Robert B. Woodward Memorial Fund, and Mary Smith Dorward Fund, 2010.2

#bhm2021#Sargent Claude Johnson#bhm#black history month#bkmamericanart#John Edmonds#Black art#Black artist#art#artist#WPA/FAP#ceramicist#painter#lithographer#alain locke#harlem renaissance

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Target to Tamarind

In celebration of Women’s History Month, March Object of the Day posts highlight women designers in the collection.

In September of 1969, the Cincinnati Art Museum hosted a retrospective exhibition dedicated to the work of June Wayne (1918-2011). Although Wayne’s prolific design practice spanned multiple media, today she is especially celebrated for her work as a lithographer. The retrospective’s exhibition poster—seen here—features a print entitled The Target, which Wayne created in February 1951, during her first forays into lithography. [1]

During the Great Depression, Wayne dropped out of school and went to work at a Chicago factory to support her family. She found opportunities to paint in her spare time, though the activity was primarily for her own enjoyment rather than to explore a possible profession. In the late 1930s, she was hired by the WPA Federal Art Project (FAP), in a division focused on easel painting. [2] At the FAP, Wayne began a lifelong career of activism in support of the arts by banding together with fellow artists to form an Artists’ Union; later, as a key representative of the Union, Wayne was instrumental in successfully lobbying Congress for greater job security for FAP artists. Speaking about her experience, Wayne has suggested that in providing opportunities and funding for artists to practice their craft, the WPA Federal Art Project inadvertently fostered the development of a cohesive profession and identity for artists in the US. [3]

After her time with the FAP, while her husband was serving overseas during World War II, Wayne moved to California. She began taking classes at Cal Tech University, learning to read and produce technical engineering drawings and blueprints. A combination of this training, her dissatisfaction with the materials and production of painting, a new comfort with self-identifying as an artist, and a lifelong fascination with optics led Wayne to explore printmaking. [4] Wayne’s first experiments with lithography were serendipitous: her neighbor, Lynton Kistler, owned and operated a lithography studio. By the mid-1950s, Wayne had turned almost exclusively to lithography, which she used to explore abstract representations of light, space, and perspective.

In 1960, Wayne established the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles. Dedicated to cultivating printmaking in America, and sustained by funds from the Ford Foundation, Tamarind offered paid fellowships to artists interested in lithography. Artists such as Ruth Asawa, Anni Albers, Gego, and Louise Nevelson came to study what was then considered a dying medium in America. [5] Wayne resigned as Director in 1970, when Tamarind was reestablished in Albuquerque as part of the University of New Mexico, but continued to work with lithography and to find ways to champion fellow artists. The legacy of her work includes influential experimentations in symbolism, surrealism, abstract figuration, and visual manifestations of feminist political theory, as well as a legacy of extraordinary advocacy for printmaking in the United States.

Kristina Parsons is the E. McKnight Kauffer Cataloguer in the Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design Department at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

[1] “The Target,” National Gallery of Art, last modified 2018, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.73940.html#marks

[2] In an oral history conducted for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution in 1965, Wayne claims she cannot recall how she was admitted into the program. However, she had exhibited her paintings in a solo exhibition at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City in 1936.

“Oral History Interview with June Wayne, 1965 June 14,” Archives of American Art, accessed March 20, 2019, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-june-wayne-11642#transcript

[3] She goes on to say that this government initiative, “gave a sense of identity, however fragmentary, to artists who till that time really could not find a slot for themselves within society.” See note 2, above.

[4] Though Wayne spent enormous periods of time painting earlier in her life, she would later came to believe that “oil on canvas is a basically idiotic combination.” See note 2, above.

[5] “Inventory of the Tamarind Institute Records, 1959-[ongoing],” The University of New Mexico, Rocky Mountain Online Archive, accessed March 20, 2019, https://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmu1mss574bc.xml#idp5228240

from Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum https://ift.tt/2JvgZKL

via IFTTT

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#ArtAppreciation ♥️🖼🎨 "By the Light of the Sun" (1935) W. 30 in; H. 40 in; W. 76.2 cm; H. 101.6 cm; Artist: Harry Gottlieb Documentation: Signed Origin: United States Period: 1920-1949 Materials: Oil on canvas laid to board Condition: Good overall condition Creation Date: C.1935 Price: $3000 Styles / Movements: Other Incollect Reference #: 408262 Harry Gottlieb, painter, screenprinter, educator, and lithographer, was born in Bucharest, Rumania. He emigrated to America in 1907, and his family settled in Minneapolis. From 1915 to 1917, Gottlieb attended the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. After a short stint as an illustrator for the U.S. Navy, Gottlieb moved to New York City; he became a scenic and costume designer for Eugene O"Neill's Provincetown Theater Group. He also studied at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts and the National Academy of Design. He was one of America's first Social Realist painters, influenced by that Robert Henri-led Ashcan movement in New York City where Gottlieb settled in 1918. He was also a pioneer in screen printing, which he learned while working for the WPA. He married Eugenie Gershoy, and the couple joined the artist colony at Woodstock, New York. He lectured widely on art education. In 1923, Gottlieb settled in Woodstock, New York and in 1931, spent a a year abroad studying under a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1935, he joined the Federal Art Project; he was one of the first members of the WPA/FAP's Silk Screen Unit. Gottlieb remained active as a painter and screen printer after the closure of the Federal Art Project. #ArtAwarness #CelebrateTheArts #Kunstliebhaber #Art https://www.instagram.com/p/Cb3pMDrJc5d/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

Artists’ identification with labor soon led to political and social activism among the artistic community. Artists who had previously always worked in isolation now found strength in numbers. In 1934 the Artists Union was formed to agitate for better pay and working conditions for artists in the FAP’s employ, and to lobby against cuts in funding. The Artists Union was also a powerful supporter of labor rights in general, often adding their presence to picket lines for other industries. The American Artists’ Congress was formed in 1936 as part of the Communist Party’s Popular Front. Artists of many different political stripes came together through this organization to promote democracy and civil liberties, lobby for government support of the arts, and to combat fascism and censorship. Through solidarity, the climate changed from one of despair to one of empowerment and of hope for a more equitable and democratic future.

The Ukiah, California branch post office built in 1936 during the New Deal Era under President Franklin D. Roosevelt by the Works Progress Administration and opened in 1937. The mural inside the post office, “Resources of the Soil,” painted in 1938 by Ben Cunningham commissioned by the Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture, reflects the “American scene” of the surrounding community. The work features two leading industries in Mendocino County at the time of the painting of the mural: farming and lumber milling.

Abraham Lincoln laid out a vision of respectability that required avoiding a job: “In these free States, a large majority are neither hirers nor hired. Men, with their families—wives, sons, and daughters—work for themselves, on their farms, in their houses and their shops, taking the whole product to themselves, and asking no favors of capital on the one hand, nor of hirelings or slaves on the other.”

https://crystalbridges.org/blog/may-day-prints-for-the-people/

https://thetruthaboutthepostoffice.wordpress.com/2012/01/11/usps-uses-flawed-process-to-close-historic-ukiah-ca-new-deal-post-office-with-art-mural/

https://daily.jstor.org/why-do-we-take-pride-in-working-for-a-paycheck/

http://www.cleveland.com/arts/index.ssf/2014/02/cmha_partners_with_ica_art_con.html

https://whowhatwhy.org/2017/09/04/labor-day-paintings-great-depression-wpa/

http://www.wiu.edu/cofac/artgallery/collection/wpa/turzak.php

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

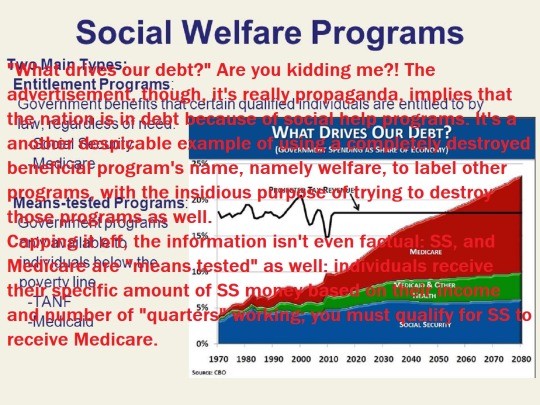

Currently, in the US, there is no Welfare program. Instead, we’ve got this (copied from the US fed website):

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

Recipients may qualify for help with:

Food

Housing

Home energy

Child care

Job training

Each state runs its TANF program differently and has a different name.

Alabama FA (Family Assistance Program)

Alaska ATAP (Alaska Temporary Assistance Program)

Arizona EMPOWER (Employing and Moving People Off Welfare and Encouraging Responsibility)

Arkansas TEA (Transitional Employment Assistance)

California CALWORKS (California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids)

Colorado Colorado Works

Connecticut JOBS FIRST

Delaware ABC (A Better Chance)

Florida Welfare Transition Program

Georgia TANF

Hawaii TANF

Idaho Temporary Assistance for Families in Idaho

Illinois TANF

Indiana TANF, TANF work program, IMPACT (Indiana Manpower Placement and Comprehensive Training)

Iowa FIP (Family Investment Program)

Kansas Kansas Works

Kentucky K-TAP (Kentucky Transitional Assistance Program)

Louisiana FITAP (Family Independence Temporary Assistance Program), STEP (Strategies to Empower People)

Maine TANF, TANF work program ASPIRE (Additional Support for People in Retraining and Employment)

Maryland FIP (Family Investment Program)

Massachusetts TAFDC (Transitional Aid to Families with Dependent Children), ESP (Employment Services Program), TANF work program

Michigan FIP (Family Independence Program)

Minnesota MFIP (Minnesota Family Investment Program)

Mississippi TANF

Missouri Beyond Welfare

Montana FAIM (Families Achieving Independence in Montana)

Nebraska Employment First

Nevada TANF

New Hampshire FAP (Family Assistance Program), NHEP (New Hampshire Employment Program)

New Jersey WFNJ (Work First New Jersey)

New Mexico NM Works

When the ‘New Deal’ was instituted, most of the programs currently being run by states from US fed funds, were covered by the WPA. Even after spending the most money it ever had on a war - WW 2 - then, compensating it’s allies and enemies for war losses with the biggest aid package ever - ‘the Marshall Plan’ - the US government was still solvent enough to maintain helpful, poverty preventing programs like Welfare, for over a decade.

#more welfare now#stop the war now#world peace three#stop the war on poverty#stop the war on terror#stop the war on the environment

0 notes

Photo

Exposition Art Blog Beatrice Mandelman

Beatrice Mandelman (December 31, 1912 – June 24, 1998), known as Bea, was an American abstract artist associated with the group known as the Taos Moderns. She was born in Newark, New Jersey to Anna Lisker Mandelman and Louis Mandelman,Jewish immigrants who imbued their children with their social justice values and love of the arts. After studying art in New York City and being employed by the Works Progress Administration Federal Arts Project (WPA-FAP), Mandelman arrived in Taos, New Mexico, with her artist husband Louis Leon Ribak in 1944 at the age of 32. Mandelman's oeuvre consisted mainly of paintings, prints, and collages. Much of her work was highly abstract, including her representational pieces such as cityscapes, landscapes, and still lifes

More

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In 1935, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt initiated the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP) as part of the New Deal recovery plan. The program substantiated the importance of the arts and artists to the US economy and recognized the need for new forms of cultural expression during a period of national uncertainty [Sheldon Art Museum]. [Balcomb Greene "Untitled #10" c. 1935 oil on canvas 30 x 40 inches] #FDR #WPA #newdeal #arts #artists #funding #balcombgreene #paintings #geometric #abstract #paintings #American #modernism #berrycampbell #gallery #nyc #chelsea #laborday (at Berry Campbell)

#geometric#nyc#modernism#wpa#10#berrycampbell#paintings#balcombgreene#abstract#laborday#fdr#arts#newdeal#artists#american#chelsea#gallery#funding

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arte Abstracto Americano

ORÍGENES:

Varios son los factores que contribuyeron al surgimiento de este movimiento como algo totalmente nuevo hacia 1945.

En primer lugar, los elementos formales provinieron de la abstracción post-cubista y del surrealismo. Y aunque los expresionistas abstractos rechazaron tanto el cubismo como el surrealismo, lo cierto es que resultaron muy influidos, sobre todo por el segundo de estos movimientos, en sus primeras fases.

En segundo lugar, es un movimiento estadounidense que surge en unas circunstancias problem

áticas desde el punto de vista social: primero, el crack de 1929 y la subsiguiente gran depresión, y después, la segunda guerra mundial. Estas circunstancias explican, en parte, el contenido emocional de los expresionistas abstractos. Ha de mencionarse organismos artísticos que fomentaron las artes durante la época crítica de los años treinta: el FAP y la WPA. En estas asociaciones artísticas se manifestaba el afán renovador del propio país norteamericano, y en ellas trabajaron algunos pintores que después destacarían como expresionistas abstractos. La pintura de la American scene típica de la llamada «Ash Can School» se vincula a este expresionismo a través de la obra de Arshile Gorky.

No pueden ignorarse, tampoco, las actividades de museos y galerías de arte que promovieron la exposición pública de las obras de estos artistas. Destaca sobre todo el nombre de la mecenas y coleccionista Peggy Guggenheim, por entonces casada con el surrealista Max Ernest. Peggy fundó en 1942, galería de arte y museo en la que presentó la obra de vanguardistas europeos y norteamericanos, promocionando la obra de los expresionistas abstractos, por entonces completamente desconocidos. En ella se celebraron las primeras exposiciones individuales de artistas como Jackson Pollock o Mark Rothko. Cerró en 1946.

Finalmente, contribuyeron al surgimiento de este movimiento los emigrados europeos que, en 1941, con el estallido de la guerra de Europa, llegaron a Nueva York. Ya con anterioridad habían llegado a Estados Unidos los dadaístas como Duchamp y Francis Picabia. Posteriormente, marcharon al continente americano Hans Hofmann y Josef Alber, quienes destacaron por su labor docente.

Entre los recién llegados con motivo de la guerra mundial estuvieron varios importantes artistas vanguardistas parisinos, provenientes sobre todo del surrealismo, como el francés André Masson y el chileno Robertto Matta. Con el estallido de la segunda guerra mundial en septiembre de 1939, Kurt Seligmann fue el primer surrealista europeo que llegó a Nueva York. Muchos otros artistas europeos influyente siguieron su ejemplo y se refugiaron en Nueva York, huyendo del nazismo: el neoplasticista Piet Mondrian, Léger, Max Ernest, el poeta Breton y Miró. Incluso Salvador Dalí, con su esposa Gala, se trasladaron a los Estados Unidos en 1940. Es en este momento cuando Nueva York se convierte en el centro artístico mundial desde donde irradian las nuevas tendencias plásticas.

Se celebraron exposiciones conjuntas de estos artistas exiliados con los emergentes artistas de la Escuela de Nueva York. Así, de octubre a diciembre de 1942 se celebró la exposición surrealista The First Papers of Surrealism, en la que junto a surrealistas europeos expusieron William Baziotes, David Hare y Robert Motherwell.

Los expresionistas tomaron del surrealismo aquello que de automático tenía el acto de pintar, con sus referencias a los impulsos psíquicos y el inconsciente. Pintar un cuadro era menos un proceso dirigido por la razón y más un acto espontáneo, una acción corporal dinámica. Les interesó, pues, el «automatismo psíquico» que hiciera salir de su mente símbolos y emociones universales.

No es extraño que les interesara entonces el surrealismo más simbólico y abstracto, el de Miró, Arp, Masson, Matta, Wolfgang Paalen y GordoOnslow Ford , más que el surrealismo figurativo. De ellos tomaron las formas orgánicas y biomórficas.

Varios son los factores que contribuyeron al surgimiento de este movimiento como algo totalmente nuevo hacia 1945.

En primer lugar, los elementos formales provinieron de la abstracción post-cubista y del surrealismo. Y aunque los expresionistas abstractos rechazaron tanto el cubismo como el surrealismo, lo cierto es que resultaron muy influidos, sobre todo por el segundo de estos movimientos, en sus primeras fases.

En segundo lugar, es un movimiento estadounidense que surge en unas circunstancias problemáticas desde el punto de vista social: primero, el crack de 1929 y la subsiguiente gran depresión, y después, la segunda guerra mundial. Estas circunstancias explican, en parte, el contenido emocional de los expresionistas abstractos. Ha de mencionarse organismos artísticos que fomentaron las artes durante la época crítica de los años treinta: el FAP y la WPA. En estas asociaciones artísticas se manifestaba el afán renovador del propio país norteamericano, y en ellas trabajaron algunos pintores que después destacarían como expresionistas abstractos. La pintura de la American scene típica de la llamada «Ash Can School» se vincula a este expresionismo a través de la obra de Arshile Gorky.

No pueden ignorarse, tampoco, las actividades de museos y galerías de arte que promovieron la exposición pública de las obras de estos artistas. Destaca sobre todo el nombre de la mecenas y coleccionista Peggy Guggenheim, por entonces casada con el surrealista Max Ernest. Peggy fundó en 1942, galería de arte y museo en la que presentó la obra de vanguardistas europeos y norteamericanos, promocionando la obra de los expresionistas abstractos, por entonces completamente desconocidos. En ella se celebraron las primeras exposiciones individuales de artistas como Jackson Pollock o Mark Rothko. Cerró en 1946.

Finalmente, contribuyeron al surgimiento de este movimiento los emigrados europeos que, en 1941, con el estallido de la guerra de Europa, llegaron a Nueva York. Ya con anterioridad habían llegado a Estados Unidos los dadaístas como Duchamp y Francis Picabia. Posteriormente, marcharon al continente americano Hans Hofmann y Josef Alber, quienes destacaron por su labor docente.

Entre los recién llegados con motivo de la guerra mundial estuvieron varios importantes artistas vanguardistas parisinos, provenientes sobre todo del surrealismo, como el francés André Masson y el chileno Robertto Matta. Con el estallido de la segunda guerra mundial en septiembre de 1939, Kurt Seligmann fue el primer surrealista europeo que llegó a Nueva York. Muchos otros artistas europeos influyente siguieron su ejemplo y se refugiaron en Nueva York, huyendo del nazismo: el neoplasticista Piet Mondrian, Léger, Max Ernest, el poeta Breton y Miró. Incluso Salvador Dalí, con su esposa Gala, se trasladaron a los Estados Unidos en 1940. Es en este momento cuando Nueva York se convierte en el centro artístico mundial desde donde irradian las nuevas tendencias plásticas.

Se celebraron exposiciones conjuntas de estos artistas exiliados con los emergentes artistas de la Escuela de Nueva York. Así, de octubre a diciembre de 1942 se celebró la exposición surrealista The First Papers of Surrealism, en la que junto a surrealistas europeos expusieron William Baziotes, David Hare y Robert Motherwell.

0 notes

Text

Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, NY: Story Circle #3, January 26, 2018

FIRST ROUND

Mark-Antonio: Introduce yourselves, who you are, region you live in the Hamptons.

I’m Mark-Antonio, educator for kids, I work with different organizations to promote sustainable living for children ages 4-13. I started working with organizations on Long Island last year. This is my first full year living in the Hamptons, and I am excited to work more with more agencies in the area.

Beverly: I am from the Shinnecock Indian nation, I live on the reservation. I attended Southampton public schools, Queens college, Missouri University, Colombia, I traveled a lot. Have a great grandson, just saw him. I’m the author of a book on the Shinnecock Indian Reservation. Its photographs and its purpose are to show we are still here. I don’t know what else to say, I love my family, very close to my family. Happy camper. My husband has Danish ancestors.

Darlene: I was born in the Bronx, parents from Puerto Rico, grew up on mid island. Came out here to high school, went to LIU. Went back and forth and moved around. Been out here since 1989, visual mixed media artist. Do mapmaking about who we are and our connections with humanity, interactions.

Scott: I’m a poet and farmer. Nice occupation. I’ve worked for the Peconic Land Trust for the last 28 years. I specifically farm in NYS. I lived here since 1989. I am here because we moved with my mother-in-law, a painter who showed at Parrish many times. She moved here in the late 70s and we followed.

Terrie: I’m the director of the Parrish, came in 2008 from Houston Texas, come from North Carolina. Even before I became the director, I’ve been coming out here since 1986, since I moved to NY and my brother Donald who is an artist lives in Sag Harbor. Came out a lot, felt lucky to live in Houston Texas and moving to the Hamptons. Terrific experience to oversee construction of this building, seeing the changes in the decade I’ve been here. For the Parrish to do Story Circles reinforces what we hope to happen in this museum as cultural and community engagement.

Joanne: I’m a docent, I do private tours for the Parrish and for a family and kids. I’m mentor to a new group of docents. We have two I’m mentoring. Trained as an artist, studied at SVU, moved to Hamptons (Southampton)—it was quiet in winter, so I started writing and joined a group. Went and got my MFA from Southampton College. I’ve segwayed from art directing to writer and have a column in the Southampton Press. I write about anything I feel like, family, children. I might write about the experience of the Story Circle, or I might not.

Bill: I’m an architect. I came out in 1950s as a kid, introduced by a WPA* artist, Harry Gottlieb. I moved the day I graduated from school, February 1972. I worked with the community and saw a lot of changes. Working now to turn the clock backwards on pollution and land quality, regenerating the landscape and restoring community and stopping social fragmentation, and preserving the natural environment. [*The government-funded Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) hired hundreds of artists who collectively created more than 100,000 paintings and murals and over 18,000 sculptures to be found in municipal buildings, schools, and hospitals in all of the 48 states.]

Mark-Antonio: Share a story about something you experienced that gave you insight into the state of our union; share a story of sense of belonging, or opposite, to the nation; or share a story about working through barriers to connect with someone different than yourself, someone you disagreed with.

Terrie: So, last year obviously was a year of a lot of turmoil and feelings that we felt disconnected from not only the government but our own communities, where to turn and what to do. For me, the most important thing that I’ve experienced in 2017 that doesn’t relate to the Parrish was participating in the Women’s March in NYC. To be part of that incredible energy was very uplifting for me, the sea of pink knitted hats, the comradery and bringing children and grandparents walking together. In my group, there was Chuck Schumer walking right in the center of my group with very little security, surrounded by people he didn’t know. It was a bit of a galvanizing force for people to feel, yes, they did have representation, the people who could help us were listening. You could barely move. It took forever to get from 42nd to 59th street. It was not frustrating or scary at all. It was just like this Story Circle, being crammed together with people you didn’t know; you could talk to people of where they came from, how they got there, who knitted their hat for them. Very uplifting thing that carried me through the whole year.

Joanne: Belonging—this is going to sound like a Parrish commercial. Living here full time, I have yoga groups and friends, but being a docent has been fulfilling to me. Everyone says thank you. Terrie handwrites thank-you notes for things we have done, the diverse programs. I give tours to be a teacher, but I learn more from the people I give tours to. It’s an interesting group of people out here. I love that it’s a place I can learn. I walk in and the guards say hey, Joanne, how are you? That’s very nice and there’s not many places you get that. The Historical Society I’m part of was nice to be connected to, but for me it’s serving to be here. I bring my husband here, he asks how long it will last?

Bill: I’ll talk about what I remember first as a kid. My mother was a teacher, she would take me and my brother for the summer out of the city for different experiences. We spent one summer in New Mexico, in a small town, Pojaque. I was 8 or 9 years old at the time, at the next table was a family with two girls our age, and my mother got talking. The head of the family was Harry Gottlieb, the artist involved in the WPA. He was involved in silk screening, we hit it off and stayed in touch for a couple of weeks. They said we had to come out to the East End. I grew up in the Bronx. No idea why so many people in NYC have never been out there. He rented a place, a barn, and trained us in painting. We went out with my family, in Hampton Bays; down toward the Ponquogue Bridge was a finger of water coming in from Shinnecock Bay. A fella who lived there, Captain Bill, was retired and ran a day camp for free for just boys. You could bring lunch in a paper bag. We didn’t pay him anything. He would watch boys 7-8 to up to 14 or so. We would jump in the water, swim. He had boats, a Chris-Craft mahogany boat and would take us out. It was beautiful and amazing, the 1950s.

Mark-Antonio: I didn’t go into much of who I was. My connection to the Hamptons is very different to most because I am an immigrant from Jamaica. I came to this country at a later age of 13, to Staten Island. Went to Holtsville, close to Ronkonkoma. My experience coming out to the Hamptons before, used to be I could feel I’m not from here or the USA, I didn’t feel a sense of belonging in general. It wasn’t until I moved here fulltime, which was last year, where I felt involved in committees in different areas, teaching with different schools in the area. I felt more a sense of belonging. Before the last election, it felt to me, in my experience, it was easy to talk about politics; after the election it became very rare, it never came up. It usually never ends well. That’s one of the things I’ve noticed for me—relating to belonging. Since the election, there’s been a sense of divisiveness.

Beverly: I’ll tell you something about this evening. I’ve never been here [at the Parrish] before. I came in, sat down, wanted to make sure I knew where to park. This man was walking down the sidewalk, he looked like a Shinnecock; sure enough, it was my cousin! He’s right over there. He had the walk that our men had. I recognized it and sure enough it was him.

Darlene: I jotted down notes, Awaiting a Vision. As an artist, I like to do this exercise. Fly up in the air, see where I am, again and again and again. Aerial views are so bizarre, going to another scale, being part of a flowing system. A skin of the earth of different species, I locate myself, there she is, that little point. What does she see, feel? I am aware of the other points as well. I expand before contracting a bit and coming back. I get nervous every time I go to some events. There’s something that developed over time, wherever I am, my skills are strange, looking at details might be unnoticed or less interesting, is part of everything else. The processing of senses. It gives a certain texture to an overall view. When we come together, at a friend’s house, serendipitously at the supermarket, or amazingly at this event tonight, we’re part of this process of co-evolving a vision. In my art, I like to see the vision evolve. In this body, I am in it, and even when I am in a bad move or do something stupid, I hope my cells will still want to be part of me and would want to make tomorrow better for all.

Scott: I have many stories I want to tell, but maybe I’ll tell a bit of each one. Because I’m a child of the late 60s, after that I left this country out of frustration to discover something new. I’m just as frustrated now with my country, but I don’t want to leave. I want to tell good stories, with a full knowledge of the divisiveness we are facing in this country. I’ll turn to this inspiring gathering of NOFA NY, North East Organic Farming Association of New York that I just attended. There used to be 150 people in their 40s, now it’s 1200 people in their 20s and 30s, and it’s so inspiring. It was in Saratoga Springs, and it housed so many people involved in sustainability. Not all farming, but mostly organic organizations. The other story I want to mention is an incredible experience in Santa Fe, New Mexico. We have some land out there, and we have been rediscovering that area. There was a Mexican Mariachi band with lots of horns, huge guitars, and base. It was really beautiful, there was a great diversity of people in support of the Dreamers. We sang the same song, which I have never felt so strongly about before that day: America the Beautiful. It was beautiful, I never had that experience, I sang the pledge of allegiance in that square in support of the Dreamers. The country is together in instances like that.

Mark-Antonio—summarizing this circle:

Some take-away was a sense of belonging. A major theme in our connections and stories. A sense of feeling a connection to a community. Joanne said, walking into a place and someone knowing your name is a big thing. Someone remembers who you are and your name, that’s huge. A sense of culture and recognition of culture. Noticing without even knowing who that person was. It’s nice to have that connection in just a community. The sense of recognizing a larger body was important. Sense of rediscovery, not just discovery and diversity. Really important to know. A real sense of disconnect and divisiveness, but also cohesiveness among a large number of us.

SECOND ROUND

Bill: I came out from NYC on a Friday night on the Jitney, with my son. We got seats together. The stewardess came up and did the tickets. Not an empty seat, jammed. People are just filled with their experiences from the city, no one is talking to each other. The stewardess is near the back lavatory. Then she gets to us, finally, I look up at her, and say, “Hi, how are you doing this evening?” She said to me, “Your ticket, please!” I said, “Sure.” Looking at her and making human contact, she took the ticket and started to cry. Did I do something wrong? She said, “No, you’re the first person to acknowledge me all day.” This was two years or so from now. Whenever I have an exchange, getting the paper or a cup of coffee, I look at them, say, Hi, how are you, make sure I’m connected. Since the current administration, I tell people how I feel. Because I understand that I felt that way on my own. It was not the general feeling of the community. I feel that I must be open to expressing myself. It allowed whoever I am with to tell me how they feel also. I think others should do the same thing, ask your neighbors how they feel, become a community who shares. There are talks about economic exchanges, but it’s good to talk about feelings. There are some contacts based on necessity, on exchange. In recognizing and solidifying our community, we will gain strength to make the changes that help us. I don’t think they are alone, we will change that.

Terrie: I lived in Paris for a whole [year?]. The idea of how you solidify yourself into a community is very much about eye contact and making personal relationships. If you move to Paris, you have two choices: Go to a bakery and buy something and walk out, and the person in the bakery will not talk to you. If you go in the first time, introduce yourself, tell them that you came from America, sorry for not great at speaking French, looking forward to seeing them, they will say, Madame, so happy to see you, I saved you the best of this or that. When we moved, we went to all the merchants and introduced ourselves, and at once we were part of that community. Just like Bill said, eye contact and introducing makes others know we want to be part of their world. There are hundreds of political parties in France, but it didn’t matter, we looked at them and said we want to be part of the community.

Bill: The young girl was happy that we acknowledged her. We all need that.

Joanne: That takes effort to make connections.

Bill: Yeah, probably, I don’t know any other way to do this… I think we’re all guilty more or less to some degree of burrowing under and avoiding what I think is actually a far more natural response to other people that you come in contact with. I don’t know if effort is the word I would use, I think if we change our habits, maybe thinking about it rather than what we do now.

Terrie: Beverly, when you recognized Leigh and knew he was part of your community, and coming here for the first time, did it make you feel more welcome?

Beverly: Yes, it did, I want to come back and learn more about the museum. I should be ashamed of myself.

Terrie: You have a personal guide to give you a tour.

Joanne: I’ll give you my email, not scheduled, half an hour whatever.

Bill: I want to ask, why didn’t you come before?

Beverly: I passed it [the Parrish] going to East Hampton, and thought, that’s a strange looking building, and asked myself, what did they do that for? I went to the old Museum when it was in the Village. Grew up with that one. Never thought of stopping actually. Knew it was there.

Mark-Antonio: A sense of connecting is powerful. Any other stories of connecting with someone? Or having a sense of connection?

Darlene: The idea of being challenged is here. I grew up on a street just off Union Avenue. Being a child who played with words and loved art I liked to search inside words, find hidden words within them and stitch them up in a picture I could carry around. “Ave” means bird in Spanish, “nue”—new of Union, of uniting, joining together, becoming or returning to one. It could be a superhero of sorts, this New Bird of Uniting…. swooping in whenever needed. Fast forward…2018. I look for this bird… think I/we need it. Maybe it had been like this, but now it felt so much stronger… that each time I tune into the radio or get into a current events discussion there seem to be so many forces trying to break us apart into smaller and smaller “Us and Them”s, dividing by race, by political affiliation, dividing by income, by religion. I see the term Resist…. And for me it takes on a slightly different tone: I want to constantly resist the divide. The Us versus Them. I picture new Birds of Union flocking down. I call out and welcome one to stay right on my shoulder now for 2018…. Reminding me every time I’m about to take some bait and help co-create a hated Other.

Scott: I like that your stories have to do with flight. New bird. Lovely.

Joanne: I liked the stewardess story.

Bill: It was shocking to me, my heart went to this little girl. I could feel what she would go through. It’s negating when you don’t recognize another person, she’s invisible. The wealthy people who live here want the service community to come, work, do deliveries, then disappear. They don’t want to see any of those people, I think. Such a common attitude in second home community. This was her second trip that day. Four trips in and out of the city.

Joe joined group, Scott joined another.

Joe: I’m a poet. So interested in being here. Last year, it was a great experience. Talking to Joanne about it, I think so many of us were shocked, coming out from our holes and caves, it gave us a chance to get a sense of what was going on in the world. Tonight, I’m interested to understand how we all progressed—is our balance better or not? Some of that sense of shock we are all feeling has settled down, and that’s good to see. It’s nice to be here and part of your circle.

Bill: A lot of talk of leaving the country, lots of shock. Everyone I knew was deeply upset that they needed to restructure their whole lives in a way. It really was an extremely profound trauma, and what I learned from other experiences in my life is that traumas of that nature actually rewire your brain. It’s your PTSD [Post Traumatic Stress Disorder]—that’s what we’re responding to. You’re right, Joe, it’s great to compare where we were. Some are settling, ways to reconnect to one another and respond in a way, the withdrawal and shock, fleeing…

Mark-Antonio: I want to keep in that frame of mind, some inflection of how you felt after the election and how you feel now. A personal story that might reflect upon that.

Beverly: I think I have a new sense—I don’t know where it came from—I sense a feeling of hope despite the chaos.

Darlene: Traumatic feeling, sometimes people I know didn’t expect it to happen this way. It was a disbelief, I basically stayed in bed and cried for a day. It was a realization that things aren’t the way I thought they were. I gradually came out of that with determination, more perspective I have been missing. Again, I am surrounded by a certain community, I hear stories—an echo chamber bringing up the same views as I. Looking at different views and hearing about them. Trying to understand. Developing a compassion for personal view, life, family and what’s going on. I feel more determined to hear different voices and find a solution.

Bill: You feel abled, before you couldn’t do anything.

Darlene: Right.

Joe: It’s been such a strange era. It’s hard to give a story from my own life, but I can share something that happened this year that reflects on what the experience has been for some. My wife and I—she is an animal person—wanted a dog for many years. Two dogs died in a short amount of time. This year she could no longer wait, needed another pet. She spent time looking, found a rescue dog that matched the dream dog. A lot of the Long Island animal organizations brought dogs from down South to be rescue dogs. This dog came up from Georgia or Alabama. We got the dog, a beautiful 1.5-year-old Chow mutt. That’s a very common breed in the South. I was drawn to it because—and I didn’t know it at the time—the Chow descended from Chinese emperors. One of my passions is Chinese poetry. I felt like I received a gift. This dog was a bit wild, she went through a trauma of her own at a home where the host died. She was not like herself. We didn’t know how she’d feel but she was at home right away. One of the first nights I was taking care of her, my wife was in the city, I turned my back, she went outside, chased something away–I thought I lost her. Somehow I lured her inside with a bone in the fridge, she dashed inside and I shut the door. How to get her to settle down and feel welcome despite the disruption in her life is as much we are all feeling, that she was in a place to feel trust. With passage of time, the same thing happened again about a month ago, when I was taking things in and out of the front door, she darted behind my back and got out. The back yard is fenced, but the front isn’t and I had a moment of panic. I looked outside; she was just sitting there, looking around. She never had really been in the front without a leash. She had gotten to that point. Part of what I realized is that she wasn’t running frantically because I wasn’t chasing her frantically. It’s a story relevant to my state of my mind. Much of how we reflect on the world is not so much on how the world is, but part of how you react is what you will get back. Part of the process is settling into our skills and understanding. That’s my story about my dog.

Terrie: For me, what’s been most interesting in settling into a new paradigm is an interior and exterior conversation for what it means to be a director of an art museum in a changing world. I always felt the Parrish should be a place of engagement for dialogue. But just that talk within the last year is not enough. Now, I think what I discovered, which is similar to your story, is that we need to learn to walk the walk. The only way to make it happen is to absorb what’s happening in the exterior, let it seep into the foundations of what the museum should be in this community, and hear what our community needs and wants from us. We need to try to figure out a way that we can come together in what we understand as the core values of the museum. From things like the Story Circle, it’s what we are about, how the boundaries and the attitudes of this institution can morph and change.

Joanne: I feel like I’m living in a soap opera, oh my god, I’ve never watched CNN so much in my life. What is he doing now? I don’t like that, but don’t want to miss anything of what’s going on. Today, whatever the latest thing is, there’s that. I want to know what’s going on, but don’t want to watch the news. Last year I was traveling a lot. The French have no idea of how it could happen. Can’t believe it. My husband is English, we visited his 90-year old mother, staying in St. Albans, just north of London, nice and affordable. It’s like sitting at the United Nations, never knowing who will be there. One morning, a very attractive mother and daughter came from Finland. The mother was getting the daughter settled into a local school near St. Albans. She kind of attentively, with perfect English, asked about our president. I was so much on the defensive, I didn’t want to defend him, I said it’s an embarrassment, but it was really interesting. Finland has one of the highest rates/standards of education, healthcare—we are sitting here, supposedly the wealthiest country in the world with nothing they have. Sometimes you have to go outside and look.

Mark-Antonio: I think that up until the last election we traveled so far as a nation in accepting one another. Bolstering our diversity in programs. Different races, peoples. We celebrated that for eight years. Then the seismic shift happened and I felt a sense of confusion, chaos. Something similar to what people are feeling with the dog running around, and I didn’t know what to do. I felt helpless. I made a commitment to myself to get out of that. I pulled myself closer to the chaos and sit still and listen. To get used to the new normal, and figure out how I can affect change. My dedication to seek out different organizations that were going to embolden my want of collaboration and felt the need of finding the same voices that go toward the same goal. It might be different in how we want it done, but my goal of taking action was to find a new normal. The new normal was a way of reaching the children in the community. Without the current administration, these truths of misunderstanding would have never come to the light. I felt that things were good before, I didn’t really need to push. I thought that our sense of community was building, they don’t really need me. I can sit back and let the administration do what they want and all the work. I was wrong, it’s a reawakening.

Terrie: This might be the take-away. We were all complacent, the voting percent is not very good. Until recently people felt like they didn’t need to be engaged. If there’s an upside, maybe that’s what you just described. If you want to live in this world, you must engage and be a part of the change. You can talk about community, take ownership of the community you want it to be.

Bill: I want to echo that, I’m extremely fortunate to be born into a family of political activists. I was there with Terrie at the Women’s March a year ago, and I found that’s the most comforting thing, getting in there and working is the best way to bring in the new world. If you don’t, you’re idle and weak. Best cure is to get engaged and it builds upon itself. It works on personal level, family level, state… the president isn’t going to be there forever. Worst case scenario is two terms, the administration won’t be there forever, the lesson taught us to get everyone together, working together.

Joanne: Especially women—a woman who has never run before in politics happened.

Terrie: If you have a vision of your future, you need to participate in it. Being hopeful is shared by everyone in a strange way, but having some power with our voices is important.

Bill: Healthy on a personal level to get involved.

Terrie: …like eating your Wheaties.

Bill: Exactly, and it makes that kind of difference. The benefit is going out there and seeing the change first hand. This activity included. And Terrie, I want to embarrass you a bit; since you’ve been in charge, I’ve seen the change and want to commend you on the success that allowed the community to come in. Very progressive way of engaging the public that the museum hasn’t seen in fifteen years.

Terrie: It’s not me… terrible cliché, but it involves a village. Every person in this room has ownership of what happens. Even people who don’t think that way, believe me, it’s true. This is everyone’s museum, and I’m comfortable having them thinking it’s theirs and part of their life. Otherwise what is the purpose of all the artworks held in public trust? What’s the point of the rooms if we can’t have people come and speak? Some of us know each other, some of us don’t. But we know each other now and will recognize each other. [to Beverly:] And I will never forget your story about your cousin! I asked him, told him about the Shinnecock walk. Explain what that means? He said tall, straight, and proud. All of us can benefit from tall, strong, and proud.

Mark-Antonio: Be the change you want to see.

Joanne: On my yoga wall, I have that.

Mark-Antonio: I felt that in the stories, being involved, making the connection. To do that, you need to make that step to make the connection, can’t just wait for that to happen.

Darlene: I love what you said, feeling the struggle, and being part of that. There’s a direction that’s happening that allows you to participate in the change. In this last year, I was asked to create a large commission, which I’ve never done. I listened to what was being asked, it was for Washington DC, for the community there, related to the idea of mapping. I did three pieces for a community room and they left it up to me, it was amazing and strange. I went through a whole list of ideas. Three pieces of different levels of our world where I felt so much right now. This conversation. The particular building had history, where was that in relation to everything else? I found where other important sites were. Focused on the space of community and interaction. That space through time, so many people were there through decades in the past trying to get through it together, through us, when we come together in any space. I did another piece called Seeds and Resonant Islands. This would be one of the seeds. This conversation tonight took place in many different areas. Looking from above, something is happening in energy, and that connects us all.