Text

Letters from Eisenbrauns: Q&A w/ María Almansa-Villatoro and Silvia Štubňová Nigrelli

María Almansa-Villatoro and Silvia Štubňová Nigrelli, editors of Ancient Egyptian and Afroasiatic: Rethinking the Origins, joined Eisenbrauns for a Q&A about their current research and how they hope it will shape future research.

Can you tell us about your current research, and how you became interested in the topic?

Almansa-Villatoro: I am mostly working on understanding how ancient Egyptians used language in specific social contexts, and how their choices to say things in certain ways, or omit information inform us about the way hierarchy, power, and ethics functioned. I study how Egyptians used politeness in personal letters, and what themes the king wants to emphasize in his royal discourse. What drew me to this topic is my conviction that we can learn so much about a specific culture by studying their use of language. As a scholar who has worked and lived in different countries, I am aware that when learning a new language, it is not enough to memorize rules and vocabulary, but one needs to know how to use indirectness, humor, or ambiguity in certain ways to convey specific things. And the way this is done is very variable across different cultures, but by looking at what is acceptable or unacceptable in certain contexts we can learn a lot about the underlying social and cultural values. I found for example that in Old Kingdom Egypt (c. 2600–2200 BCE) overt authoritarianism and coercion (even by the king) is frowned upon, and it is often camouflaged by indirect requests or euphemisms for acts of command. This teaches us that we can’t always take ancient texts literally and need to sometimes be able to read between the lines, but perhaps more importantly, that Egyptians considered impositions ethically reproachable.

Nigrelli: My research aims to elucidate the complexities of the ancient Egyptian grammatical system and to better understand the world and lived experiences of ancient Egyptians through linguistic and philological analyses of written sources. Most recently I have been working on refining our understanding of some medical terms associated with visual impairment. I became interested in the ancient Egyptian language already in high school, when I came across a crash course of hieroglyphs in a popular history magazine and knew immediately that that was something I had to study. I love reading the original texts as they open up the door to the world of the ancient Egyptians and show us that, in many respects, they were people like us. The medical aspect of my research comes from my husband, who is an eye doctor, so we tend to talk a lot about eye diseases and treatments, both modern and ancient.

How do you anticipate your research will help inspire other research in your discipline?

Almansa-Villatoro: I have striven to raise awareness among my colleagues about the potential of applying the latest research methods in pragmatics and linguistics to the study of ancient sources, particularly (im-)politeness research and discourse analysis. These frameworks can bring us closer to the meaning of texts in their original ancient contexts, disentangled from what we, as modern scholars, think that the function of these documents should be. The use of interdisciplinary approaches not only shed new light on ancient data, but also enable a more nuanced understanding of the communicative or practical function of texts that we have imprecisely labelled as “propagandistic”, “religious”, or “literary.”

Nigrelli: I am hoping to show that our traditionally accepted translations of some words/phrases can be interpreted in a different way, leading to a new look at how the Egyptians perceived their world, and that we should devote more time to studying ancient Egyptian semantics and linguistics. It seems to me that nowadays the language plays a rather minor role in Egyptological curricula and research, which is unfortunate, because its knowledge is crucial for our understanding and interpretation of ancient Egyptian written materials and the world of ancient Egypt in general.

What are the advantages of examining ancient Egyptian in its African context?

Almansa-Villatoro: The complicated history of ancient Egyptian has been traditionally dominated by a semito-centric approach which Egyptologists are now generally rejecting. The relationships within the Afroasiatic family are still not well understood, and scholars (including the contributors of our volume) do not even agree on what languages to include in the phylum. Ancient Egyptian in particular has the added difficulty of being attested for several millennia without a close relative. The other Afroasiatic languages that co-existed with Egyptian for much of its history were Semitic (e.g. Akkadian), and this contemporaneousness may have resulted in a bigger number of perceived similarities. In contrast, other African languages do not appear in the written record until much later, when Egyptian had gone through millennia of development. However, it is undeniable that most of the Afroasiatic languages are nowadays located in Africa, and Egyptian probably interacted with them for many centuries before the earliest texts. This is why we wanted to invite the contributors of our volume to rethink the origins of Afroasiatic and try and reconstruct the history of ancient Egyptian through its similarities to other languages in the phylum from the point of view of phonology, lexicon, and syntax. The surprise was that, depending on what aspect of the language one chooses to focus on, the resulting trees and genetic links are completely different. Hopefully these results will pave the way for future research on ancient Egyptian and Afroasiatic.

Nigrelli: Looking at the ancient Egyptian language within its Afroasiatic context is important for our understanding and classification of the languages in this family and it should also help us with studying the interrelations among the early cultures, i.e., the speakers of the Afroasiatic languages. Trying to figure out the proto-language of each member of this language family should be the first step in reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic. However, since ancient Egyptian constitutes a single branch in the Afroasiatic language family, we can’t compare it to other languages when trying to reconstruct Pre-Egyptian. We can work on its internal reconstruction to some extent, but that’s very difficult. That’s also why we organized this workshop – to explore, despite all these drawbacks, whether there is any methodological framework that could be employed to determine a more precise relationship among the Afroasiatic languages.

Ancient Egyptian and Afroasiatic: Rethinking the Origins is now available from Eisenbrauns. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.eisenbrauns.org/books/titles/978-1-64602-212-0.html. Save 30% w/ discount code NR24.

Eisenbrauns, an imprint of Penn State University Press, publishes books in in Ancient Near East studies, biblical studies, biblical archaeology, Assyriology, linguistics, and related fields. Find more information and Eisenbrauns books here: https://www.eisenbrauns.org/.

#PSU Press#Penn State University Press#Eisenbrauns#Ancient Egyptian#Egyptian#Egypt#Afoasiatic#African#Africa#Language#Archaeology

0 notes

Text

Unlocked Book of the Month: Transcending Textuality

Each month we’re highlighting a book available through PSU Press Unlocked, an open access initiative featuring scholarly digital books and journals in the humanities and social sciences.

About our April pick:

In Transcending Textuality, Ariadna García-Bryce provides a fresh look at post-Trent political culture and Francisco de Quevedo’s place within it by examining his works in relation to two potentially rival means of transmitting authority: spectacle and print. Quevedo’s highly theatrical conceptions of power are identified with court ceremony, devotional ritual, monarchical and spiritual imagery, and religious and classical oratory. At the same time, his investment in physical and emotional display is shown to be fraught with concern about the decline of body-centered modes of propagating authority in the increasingly impersonalized world of print. Transcending Textuality shows that Quevedo’s poetics are, in great measure, defined by the attempt to retain in writing the qualities of live physical display.

Read more and access the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-03775-2.html

See the full list of Unlocked titles here: https://www.psupress.org/unlocked/unlocked_gallery.html

#Spain#Early Modern#Early Modern History#Spanish Baroque#Baroque#Saavedra Fajardo#Gracián#Politics#PSU Press Unlocked

0 notes

Text

The Fascinating Lens of Online Video

John Jordan, author of The Rise of the Algorithms, discusses short-form content, AI and privacy, and more.

If you look closely, online video is at or near the heart of several current, complex issues: the emergence of new dopamine-driven forms of engagement, the role of Internet technologies in geopolitics, AI, and privacy. TikTok, Twitch, YouTube, and their kin are shaping large segments of contemporary life.

If we consider the history of music, technology has driven music to get shorter and shorter. Symphonies could run well over an hour, LP records had two twenty-minute sides, radio drove the rise of the three-minute single, and now TikToks are measured in seconds. The benefit of these brief “works” is that they give the viewer a series of chemical rewards, shortening attention spans for both entertainment and education. Just ask any teacher. (The music and cultural critic Ted Gioia has an excellent series of Substack posts on the topic.)

If we look back to the 1990s, considering Microsoft as an actor in geopolitics would have overstated the company’s role: its revenue and market capitalization were a fraction of, say, Ford’s, not to mention Exxon’s. But now Facebook measures its global user base in the billions, TikTok’s parent company ByteDance is the subject of both presidential and congressional threats, and YouTube wrestles with how to treat what might be satire in France but is considered heresy in the Arab world. Tech, including misinformation purveyed through it, sways elections, spurs boycotts, and challenges national norms.

Speaking of misinformation, AI is leading to creative uses of online video. Identifying and potentially removing fakes, whether in porn—ask Taylor Swift—or politics, grows more difficult every month as tools of synthetic creation outrun tools of detection. There might also be an emerging category of deep fakes used for good. Recently, a group of parents of children killed by gun violence created deep fakes of their children to create a message urging legislators to address the issue. Machine learning also powers the algorithms that feed us an endless stream of clickworthy content, so in many ways the history of AI is entwined with the development of online video.

Given the scale and ubiquity of online video, there are inevitably related privacy issues. YouTube was originally used to post videos intended for family and close friends, typically fewer than a hundred viewers. Now we have a system where viewers and followers are counted in the tens of millions. The kind of fame that Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson or a Kardashian brings to online video is markedly different from how people view Charli d’Amelio or Mr. Beast, who feel more relatable and inspire a false sense of familiarity. Creators in the latter vein frequently burn out from trying to satisfy the needs of their viewers for bigger stunts, better dances, edgier humor. Users also sacrifice privacy in return for ever more precisely targeted algorithmic clickbait.

All told, understanding online video gives one multiple insights into the state of politics, emotional health, and culture in the 2020s. It’s a fascinating lens, at once dynamic and enduring, personalized and massive, trivial and consequential.

The Rise of the Algorithms: How YouTube and TikTok Conquered the World is now available from PSU Press. Learn more and pre-order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09692-6.html. Save 30% w/ discount code NR24.

#YouTube#TikTok#Content#Twitch#Internet#AI#Privacy#Media#Communications#Taylor Swift#Politics#Mr. Beast#Charli d'Amelio#Microsoft#The Rock#Kardashian#ByteDance#Algorithm#PSU Press#Penn State University Press

0 notes

Text

Q&A with Kerry Wallach

The author of Traces of a Jewish Artist discusses Rahel Szalit, Szalit's relationship to other Jewish artists of her time, and more.

What made you want to write a book about Rahel Szalit?

I first discovered Rahel Szalit while doing research in Berlin archives. I kept finding her artwork in newspapers from the 1920s, but there wasn’t much information available about the artist herself. Her images enchanted and haunted me, and I couldn’t stop wondering about the person who created them. Like so many who were murdered in the Holocaust, Szalit’s story had never been told at length. I realized that if I didn’t tell her story, no one would.

How did Szalit differ from other women artists of her time?

Rahel Szalit (née Markus; also Szalit-Marcus; 1888–1942) came to Germany as an outsider from Eastern Europe with a working-class background. Many German women artists in the early twentieth century had middle-class backgrounds and were supported financially by their families or husbands. Szalit couldn’t afford enrollment fees for art academies, though she eventually learned painting and lithography. Yet no matter how successful she became, Szalit’s situation always remained precarious. She made ends meet by giving lessons in drawing, painting, and fencing.

Probably the biggest difference between Szalit and most of her female contemporaries is that Szalit was relatively successful in Jewish circles, perhaps even more so than in mainstream artists’ circles. Szalit is known for lithographic prints, and it makes sense to compare her with Käthe Kollwitz, who likewise depicted impoverished members of the working class. Around 1927, Szalit became active in the Association of Women Artists in Berlin. Through this group, she exhibited alongside artists including Käthe Kollwitz, Lotte Laserstein, Renée Sintenis, and Milly Steger. Many depicted women as subjects, though only a few (such as Julie Wolfthorn) were known for portraying Jewish subjects.

What did Szalit have in common with other Jewish artists?

Because of her personal connections to Eastern Europe (Lithuania, Poland), Szalit’s work conveyed a sense of authenticity that was in demand. She contributed to the Jewish Renaissance in Germany alongside Jakob Steinhardt and Ludwig Meidner, who—like Szalit—depicted Jewish subjects in an Expressionist style that emphasized distorted, angular shapes and powerful colors. In fact, Szalit was one of only a handful of women mentioned in studies of Jewish art of this period.

What was Szalit's relationship to modern art movements?

Both Expressionism and New Objectivity were important for Szalit’s career in Germany. Whereas many of Szalit’s lithographic illustrations from the early 1920s experiment with an Expressionist style, many of her later paintings and drawings offered realistic portraits of social types more in line with New Objectivity. Additionally, we know Szalit was friends with painter Karl Hofer and other artists in his networks.

In 1933, Szalit fled Germany for France, where she became affiliated with the School of Paris. Here she exhibited with Marc Chagall, Eugen Spiro, Emmanuel Mané-Katz, Chana Orloff, and other Jewish artists, including many who hailed from Eastern Europe. Szalit was later included in Hersh Fenster’s Yiddish memorial volume, which commemorated over eighty Jewish artists of France who died in the Holocaust. In the epilogue to my book, I discuss how Szalit—whose life and work spanned several countries and movements—could be claimed and remembered.

Traces of a Jewish Artist: The Lost Life and Work of Rahel Szalit is now available from Penn State University Press. Find more information and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09559-2.html. Save 30% with discount code NR24.

#Rahel Szalit#Szalit#Art#Art History#Jewish Art#Judaism#Gender Studies#LGBTQ#LGBTQ Studies#PSU Press#Penn State University Press

1 note

·

View note

Text

Q&A with the editors of the Troubling Democracy series

Lisa Flores and Christa Olson, the editors of our new Troubling Democracy series, discuss the aim of the series, what "troubling democracy" means, and more.

How do you conceive the series and what excites it?

The fact that Troubling Democracy stems from the Rhetoric and Democratic Deliberation series absolutely shapes how we approached our work as new series editors. It felt important to keep “democracy”—both as a key term for the series and as an idea that’s long been resonant in scholarly and public circles.

We’re grateful for the leadership and vision that Cheryl Glenn and Stephen Browne brought to the RDD series. They made space for a wide range of scholarship and a wide range of scholars—that’s something we’re excited to continue and expand even further.

At the same time, neither of us is particularly comfortable with democracy as a so-called god term. In fact, as we’ve been putting the series together, we’ve talked (and laughed) about how we each almost didn’t submit our work to the RDD series because it didn’t feel like it fit. We don’t quite do democracy. But Cheryl and Steve made space for us, and that helped shape our thinking about how to make this new series a place that welcomes lots of ways of thinking through governance and public life—how to make Troubling Democracy a democratic place, even, because of course we both actually do do democracy in all its troubling imperfections.

That means for the series we view trouble and democracy capaciously—maybe even with a hint of irreverence. It’s what makes this next stage of the series particularly exciting. We want to see what scholars today are doing when they launch from the field’s longstanding interests in the public and the civic and take them in new directions. We wonder what comes out of grappling with our past ways of relating to one another—inspiring or troubling—and (re)imagining (and/or reclaiming) our presents and futures together.

How do you define "troubling democracy"?

We’re excited by the possibilities of “trouble”—we are locating this series in the discomfort of democracy. To trouble is one thing, to be troubled is another, and to cultivate trouble is perhaps a third. Each has a place in this series. We believe seeming disparities signal space for generative conversations. It is so easy to fall back on democracy as a clear good, even as our research, our teaching, and our lives remind us that democracy is not—its failures and exclusions fall hardest on some bodies and beings while protecting and privileging others. As a result, some of the most interesting scholarship in the last decade has seen democracy as a site of contention, failure, and struggle, pushing scholars and activists to think at impossible intersections. We want to help cultivate that kind of scholarship, and we see the Troubling Democracy series as a home for it.

Who is this series for? What kind of projects are you looking for?

If your manuscript is about democracy qua democracy, it fits in this series. But if your manuscript is about world-making, about breakdowns in public life, about imagining relations among humans (and nonhumans) that are outside the bounds of Western democracy, it also definitely fits. We hope that our own histories of not-quite-fitting into democracy invite others to see themselves and their work in this series.

A focus on “democracy” isn’t just about narrow modes of governance. This series is premised in simultaneous skepticism and hope, and we hope it will foster critical conversations that break open democracy’s possibilties. We’re looking forward to reading manuscripts about the power and limits of communication, about governance, resistance, control, and revolution. We’d like scholars to share work that engages in new methods, theories, and locations and that centers neglected or marginalized archives and conversations.

What are your long-term hopes for this series?

We want to support people in creating the best scholarly books they can—helping them navigate the publication process and achieve their intellectual goals. That’s the bread and butter of editing a series like this.

We also hope that Troubling Democracy can become a home for innovative scholarly projects—texts that don’t function exactly like traditional monographs—and for more public-facing publications. We’re excited to collaborate with authors looking to showcase how scholarship can speak to contemporary issues and those invested in contributing to public conversations. We’ve got some learning to do before we can launch anything specific in that vein, but we’re hoping our inspiring colleagues will come to us with ideas.

As scholars/teachers invested in and committed to building critical race/feminist/queer collaboration, we invite you into conversation: [email protected] and [email protected]

#Democracy#Troubling Democracy#Public Life#Governance#Global#Interdisciplinary#Civic Life#Social Change#Penn State University Press

0 notes

Text

Unlocked Book of the Month: Juniata Memories

Each month we’re highlighting a book available through PSU Press Unlocked, an open access initiative featuring scholarly digital books and journals in the humanities and social sciences.

About our March pick:

Published in 1916, Juniata Memories was Henry W. Shoemaker’s eighth volume of Pennsylvania folklore. Written in the author’s typical literary style, this volume includes twenty-six legends set in Central Pennsylvania and the Juniata Valley. These stories, “secured from old people, hermits, farmers, lumbermen, teamsters, hostlers, hunters, trappers, old soldiers, and their ladies,” prominently feature the Stone, Kishacoquillas, and Penn’s Valleys and the many towns that lie within and around them, such as Huntingdon, Lewistown, and Selinsgrove. The stories share a common theme with those in many of Shoemaker’s other volumes, portraying Pennsylvania’s pioneers as having a decidedly spiritual connection with nature.

Juniata Memories includes some of Shoemaker’s best-known legends, such as “Nita-Nee: A Tradition of a Juniata Maiden” (the story of Mount Nittany’s formation in Centre County) and “The Standing Stone: A Legend of the Ancient Oneidas” (set in Huntingdon County). These popular tales stand alongside Shoemaker’s telling of famous area love stories, ghost lore, supposed Indian legends, hunting lore, and even a story of buried treasure along the Susquehanna River. The volume is illustrated with scenic turn-of-the-century photographs taken by the Pennsylvania Railroad’s official photographer.

Read more and access the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-05239-7.html

See the full list of Unlocked titles here: https://www.psupress.org/unlocked/unlocked_gallery.html

#Juniata#Pennsylvania#Pennsylvania History#PA History#Folklore#Central Pennsylvania#Juniata Valley#PSU Press Unlocked#PSUP Unlocked

0 notes

Text

Unlocked Book of the Month: History, Manners, and Customs of the Indian Nations Who Once Inhabited Pennsylvania and the Neighbouring States

Each month we’re highlighting a book available through PSU Press Unlocked, an open access initiative featuring scholarly digital books and journals in the humanities and social sciences.

About our February pick:

First published by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1818, History, Manners, and Customs of the Indian Nations provides an account of the Lenni Lenape and other tribes in the mid-Atlantic region, looking at their history and relations with other tribes and settlers, as well as their spiritual beliefs, government and politics, education, language, social institutions, dress, food, and other customs. The text, written by the Reverend John Heckewelder, a Moravian missionary based in Ohio and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, includes the author’s observations, anecdotes, and advice, preserving not only his knowledge about the Indian nations in the eighteenth century but also his perspective, as a missionary and settler, on Native Americans and the often-fraught relationships between the tribes and European settlers. This version of the text, published in 1876, contains an introduction and notes by the Reverend William C. Reichel as well as a glossary of Lenape words and phrases and letters between the author and the then-president of the American Philosophical Society concerning the study of the Indian nations and their languages.

Read more & access the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-06701-8.html

See the full list of Unlocked titles here: https://www.psupress.org/unlocked/unlocked_gallery.html

#Pennsylvania#Pennsylvania History#PA History#Lenni Lenape#Indian#Native American#Mid-Atlantic#Atlantic#Moravian#John Heckewelder#Ohio#Eighteenth Century#Nineteenth Century#Lenape#American Philosophical Society#PSU Press#PSU Press Unlocked

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Delicate Matter: An excerpt

What is the relationship between the exquisite delicacy of art and the debased flimsiness of disposable commodities? Few people today would deny that a distinction exists between these two forms of perishability. The Louvre may sit atop an enormous mall, but no one would confuse the art in the galleries with the fashionable goods in the basement shops. A world of difference separates, for example, the delicate brushstrokes of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s paintings from the latest season of trinkets and fragrances on display downstairs in the Fragonard perfumery. A painting by Fragonard such as The Warrior’s Dream of Love may, like perfume, conjure evanescent pleasure, but the museum ensures that we regard the fragility of the painting itself as much more than an expression of commercial ephemerality. When the museum’s informational brochure cautions us that “works of art are unique and fragile” and that “touching, even lightly” can cause irreparable harm, the warning makes no reference to market worth. The significance of art’s fragile materiality goes unspecified, but we are told that whatever unnamed essence it contains “must be preserved for future generations.” If the perishability of a commercial product reflects the fleetingness of fashion, then the fragility of art here stands for the opposite, representing something whose value transcends time.

This book is devoted to disputing such a neat division between the delicacy of art and the ephemerality of consumer goods. More specifically, it is a book about the fragile and decaying objects from eighteenth-century France that first prompted people to wish this slippery distinction into existence. The period witnessed an unprecedented proliferation of materially unstable art. Some artists made objects that were fragile by design, creating enormous pastel portraits that were vulnerable to the slightest touch, or constructing spectacularly breakable sculptures from attenuated pieces of clay. For other artists, impermanence was an unintended by-product of a search for novel and spontaneous effects. The Warrior’s Dream of Love provides a telling example from this second category. Until the painting’s restoration in 1987, it was considered unworthy of exhibition because it was in such poor condition. The painting’s decay stemmed from the process of its production: Fragonard employed an unusual quantity of a drying agent when painting it, which soon caused broad cracks to form across its surface. The use of these siccative oils was a notorious problem among painters at the time, so much so that the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture had issued warnings about it in the decades before Fragonard produced the picture. These ingredients allowed artists to work more quickly and to produce atmospheric effects, but they resulted in damage within a matter of years, rendering paintings nearly unrecognizable.

Such techniques developed in tandem with broader changes in the artistic economy. The eighteenth century was a pivotal moment in the history of the art market: private collections grew in both number and size, art increasingly changed hands at auction, and art dealers acquired a new professional status. These commercial developments subjected art to competing temporal pressures. On the one hand, the commodification of art led to a new concern for issues of conservation. Collectors prized art’s materiality as the bearer of an artist’s autographic touch and as a source of sensory pleasure, which meant that art’s value became intertwined with its physical condition. On the other hand, the market created short-term incentives that were at odds with the expectation of durability. Artists had to work quickly to make a living and to keep up with trends in taste, which could lead them to take technical shortcuts. In addition, the demand for sensuous surfaces and novel techniques among collectors pushed artists to become more experimental, sometimes causing them to sacrifice permanence in the process. The painter Jean-Baptiste Oudry warned about this tendency in a 1752 lecture to the Academy, explaining that artists had been led astray in their search for beguiling surface effects: “The seduction that it achieves passes like a dream, and all this beautiful work turns yellow in no time at all.”

A Delicate Matter: Art, Fragility, and Consumption in Eighteenth-Century France is available for pre-order from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09528-8.html

#Painting#Art#Art History#Europe#European Art#Eighteenth Century#Eighteenth Century Art#18th Century#18th Century Art#Jean-Honoré Fragonard#Fragonard#French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture#The Warrior's Dream of Love#PSU Press#Penn State University Press

0 notes

Text

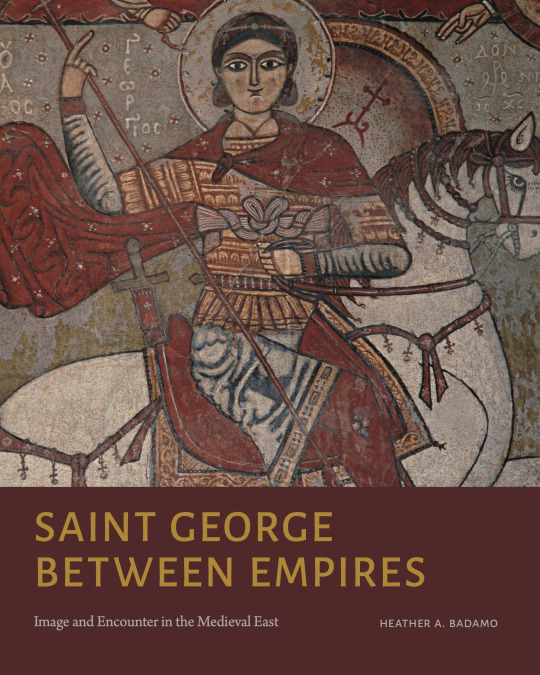

Q&A with Heather Badamo

The author of Saint George Between Empires: Image and Encounter in the Medieval East discusses images of Saint George in the Medieval East, why this perspective is important, and more.

Why investigate images of Saint George during this period?

Saint George is one of the most revered saints in the Christian tradition, with devotees across the globe. For audiences in America and Europe, he is best known as the patron saint of England, a dragon slayer, and a paradigm of medieval chivalric ideas. Yet long before Saint George became a model of Christian knighthood in Europe, he was venerated as a warrior saint in the Eastern Mediterranean. By studying images of Saint George from the eleventh through fifteenth centuries, I draw attention to the period in which he rose to global prominence. Not coincidentally, this period corresponds with the emergence of an integrated world system, which connected peoples across Afro-Eurasia via extensive trade networks. These routes enabled representations of Saint George to travel far and wide.

This is also the period in which Saint George acquired his most famous miracles, including his defeat of a dragon, rescue of a Christian captive, and intervention at the Battle of Antioch in 1098. Image makers developed new ways to represent Saint George that displayed his saintly talents, continuously redefining his significance in relation to their political, military, and devotional needs. Much of the imagery developed during this period is still in use today—including depictions of miracles that remain popular among East Christian communities but never gained a major audience in Western Europe and the Americas.

Why examine Saint George from the perspective of the Eastern Mediterranean?

Prior to the sixteenth century, Europe was situated at the periphery of several trade circuits centered in the Eastern Mediterranean, which connected Europe to Asia and East Africa. The East was home to important political and religious centers: the imperial cities of Constantinople and Baghdad, and the holy cities of Jerusalem and Mecca. Eastern Mediterranean states, moreover, were characterized by complex demographics at all levels of society, which profoundly shaped the meanings of Saint George. In many places, Christian and Muslim elites intermarried, coinage bore multiple languages, and artworks combined different visual systems. These cultural crossings made the region an incubator for new stories and images of the saint.

We can get a sense of how intercultural encounters shaped Saint George when we turn to his dragon-slaying miracle. It probably emerged in the medieval Kingdom of Georgia, where royal patronage of Persian poets introduced epics that celebrated dragon-slaying heroes, often rewarded with marriage to a ruler’s daughter. Once Saint George acquired his own dragon-slaying feat, hagiographers translated the story into numerous languages, facilitating its circulation across Afro-Eurasia and inspiring the representations that made him a “world-wide” model of pious heroism. These images were—and remain—important resources for political self-fashioning. A focus on the Eastern Mediterranean, then, shows the complex story of interfaith borrowings that underlie this well-known European exemplar of Christian chivalry. It’s also notable that images of Saint George battling a dragon moved in multiple directions, eschewing a linear trajectory from the medieval East to Latin Europe and the present “West.” This means we can use images of him to chart other paths from antiquity to modernity.

How does a focus on representations of Saint George open up new avenues for exploring intercultural encounters in the Middle Ages?

Saint George is probably one of the most popular postbiblical saints in the Christian tradition. He was venerated by various Christian confessions in the Eastern Mediterranean, and also by Muslims. In this respect, he resembles other exemplars of global exchange, like Alexander the Great—a world conqueror whose story was retold across Afro-Eurasia. A focus on the mutable representations of Saint George provides us with a way to consider image making and storytelling as vital means of exchanging ideas about sanctity, heroism, violence, and empire.

To make sense of his movement and transformations across communities, I turned to translation studies, which draw attention to the political stakes of appropriating texts and recontextualizing them for audiences of different ethnic, religious, and linguistic affiliations. In doing so, I show how Saint George acted as a common resource for negotiating the relationships among diverse states and the constituencies within them. Since Saint George was represented primarily as a warrior saint, a focus on him also prompts us to think about the role of violence in mediating intercultural encounters. Though often omitted from studies of the arts and exchange, thinking about conflict can help us clarify the stakes of intercultural exchange and better appreciate the period’s more peaceable instances of interfaith and cross-cultural mingling.

Saint George Between Empires: Image and Encounter in the Medieval East is available for pre-order from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09522-6.html. Save 30% w/ discount code NR23.

0 notes

Text

Q&A with Monica Chiu

The author of Show Me Where It Hurts: Manifesting Illness and Impairment in Graphic Pathography discusses the growing field of graphic pathography, its benefits, and more.

Why is graphic pathography such a fast-growing field, and how does it "work" for the drawing subject?

Graphic pathography allows subjects who have fallen ill or experienced a medical or clinical challenge to have their say—or rather, to draw their own representations. If the internal workings of the body disappear from consciousness when we are in good health, according to Drew Leder, their appearance as aches and pains during illness, I argue, invites artists to reenvision or revise Leder’s “recessed body.” Graphic pathography illustrates the experiences of illness, sometimes to critique a subject’s care and caregivers, other times to offer fresh perspectives on the effects of receiving chemotherapy, living with clinical depression, or struggling against anorexia, among many other experiences. Because the artists are freed from confining clinical representations to express themselves through the graphic line—one with infinite possibilities of showing what sometimes telling cannot achieve—graphic pathography invites aesthetic and personal responses by which others can learn and empathize. That medical schools increasingly are incorporating courses in graphic medicine, in addition to existing courses in narrative medicine (writing about one’s experiences of illness or impairment), teachers, students, and medical practitioners alike find that art can assist in healing.

What subjects do artists of graphic pathography pursue and why?

Artists attend to illnesses and diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer’s, depression, dementia, anorexia, COVID—every experience is different depending on a multitude of factors, including support, race, economic class, gender, community ideology, and sexual orientation. Artists also address sexual reassignment surgery to offer needed information for those uninformed of the procedures, to dispel fictions about trans subjects, and to highlight their challenges. Others draw comics about caring for the old and infirm—assuring their readers that no one correct way exists by which to provide comfort—or tending to the very young who die young, in illustrations of grief. Health care providers cogitate, by reading or creating comics, on how to be a compassionate doctor, nurse, or other caregiver by highlighting the pressures and pleasures as well as the challenges and victories of their professions. Medical students illustrate how their exhaustion and sometimes lack of thoughtful pedagogy leads to self-critique and self-doubt.

What benefits accrue in creating graphic pathography for artists, readers, and healthcare providers?

Artists bestow agency on their cartoon selves through thoughtful depictions of their corporeality drawn against disciplining representations created for them under health care and within health care spaces. We might usefully remind ourselves that the Latin-derived term “patient” is defined (by the Online Etymology Dictionary) as the “quality of being willing to bear adversities; a calm endurance of misfortune; bearing of suffering.” Where do we see the unpatients (the nonpatient subjects) of graphic pathography, those characters who unwillingly bear adversity? Through comics artists’ self-representations, traces of the imputations of illness and impairment, or of medicine’s sometimes cold and categorizing gaze, are slowly chipped away, and sometimes completely demolished, in the artist’s manifestation. The term manifestation references showing by illustration, the man of the drawing “hand,” and that of keeping a log, like a ship’s manifest.

Why do so many graphic pathographies by and about white subjects exist in relation to the paucity of works by artists of color?

This is the question that concludes my study, among related inquiries that invite other scholars in the field to participate in writing about graphic medicine’s many representations beyond those by and about white subjects: if predominantly white bodies self-represent, what does this glaring omission portend for the larger field of graphic medicine and its readers? To whom does medicine cater? Historically, black men and women unknowingly served as experimental bodies for medical science; meanwhile, Asian immigrant bodies were grounded in cultural narratives of both disease and palliation, the former playing out currently during the COVID pandemic, the latter in the conception of them as model minorities. In what unfortunate ways do images of black, yellow, and brown bodies intersect with illness and disability? I ask us to inquire: how is an academic focus on comics by white subjects consciously exposing or unconsciously contributing to a historical convergence among race, disease, and/or disability?

Show Me Where It Hurts: Manifesting Illness and Impairment in Graphic Pathography is now available from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09682-7.html. Save 30% w/ discount code NR23.

#Graphic Pathography#Pathography#Medicine#Healthcare#Graphic Studies#Art#Graphic Medicine#Drawing#PSU Press#Penn State University Press

1 note

·

View note

Text

Unlocked Book of the Month: Black Forest Souvenirs

Each month we’re highlighting a book available through PSU Press Unlocked, an open access initiative featuring scholarly digital books and journals in the humanities and social sciences.

About our December pick:

Black Forest Souvenirs was inspired by Henry Shoemaker’s early experience in the Black Forest of Germany and the mystical draw of its vast expanse of hemlocks, spruces, and pines interspersed with lumbermen and roaming wildlife. On trips to Clinton, Potter, McKean, and Lycoming Counties in Pennsylvania between 1899 and 1902, Shoemaker discovered forests still intact, evoking the romantic ideal of the German Schwarzwald. However, upon returning to the mountains five years later, he found these forests desolated by the logging industry, practically a ruin—a vision far from the romanticized wilderness he had encountered early in life. This destruction inspired Shoemaker to attempt to preserve the region’s folklore, recording stories and tales told by elderly residents of the area. Traversing the line between fact and fiction, Black Forest Souvenirs reveals a pristine landscape preserved in the minds of its people.

This collection of legends from the northern regions of the state was originally printed by the Bright-Faust Printing Company in Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1914 and includes photographs by William T. Clarke.

Read more & access the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-05644-9.html

See the full list of Unlocked titles here: https://www.psupress.org/unlocked/unlocked_gallery.html

#Forest#Pennsylvania#Pennsylvania History#PA History#Nature#Hemlock#Spruce#Pine#Germany#Henry Shoemaker#PSU Press Unlocked

0 notes

Text

Q&A with Sabrina Fuchs Abrams

The author of New York Women of Wit in the Twentieth Century discusses how women have used humor as social critique, the relationship of women of wit to feminism, and more.

How has humor been used by women and other marginalized groups as an indirect form of social critique?

Humor offers women and other marginalized groups an effective way to mask their criticism through the socially acceptable form of laughter. Satire, in particular, is often used by outsiders to voice protest against dominant racial, class, and gender norms and social stereotypes. The female satirist is in a unique position as somewhat of an outsider operating within mainstream society; this dual perspective shapes the often ironic, double-voiced, or dialogical nature of much of women’s humor. The aggressive posture of the satirist, however, is often seen as being “unfeminine” and is one reason why women’s humor has been overlooked and even resisted. For many of these women writers, the double-voiced irony of humor as well as the female self-fashioning of their appearances offers a necessary masking of their subversive messages in order to have their voices heard.

Why have you selected this particular group of authors, and why this time and place?

New York women of wit in the interwar period went beyond domestic subjects of marriage and motherhood of previous female humorists to address larger issues of political and social reform. Many of these writers stood on the periphery of predominantly male New York intellectual circles, which gave them a vantage point from which to critique a world to which they partially belonged. I further undertake the feminist project of uncovering the contribution of lesser-known female satirists in a new light.

These writers include Edna St. Vincent Millay, who wrote satiric sketches under the pseudonym Nancy Boyd; Tess Slesinger among the Menorah Journal group; Dorothy Parker among the Algonquin wits; Jessie Redmon Fauset among the Harlem Renaissance writers; Dawn Powell of the Lafayette Circle; and Mary McCarthy among the Partisan Review crowd. These women writers developed a more urban and urbane form of humor that reflects the increasingly cosmopolitan and sophisticated time and place in which they lived.

New York City in the 1920s and ’30s was a place of social change and urban possibility: the rise of modernism, the fight for women’s suffrage, the advent of birth control, the emergence of the New Woman and the New Negro Woman, and the growth of urban centers gave rise to a new voice of women’s humor, one that was at once defiant and conflicted in defining female identity and the underlying assumptions about gender roles in US society.

What is the relationship of these women of wit to feminism, and how have they influenced feminist humorists today?

While many of these writers defied social categories and may not have identified as feminists or even women writers, they embodied feminist ideals of being smart, sassy, sexy, and at times strident. These female humorists often found themselves in a double bind of being seen as too feminine (in their appearance or in their subject matter) or not feminine enough for their outspoken and often uncensored treatment of taboo subjects. Given such labels as a “modern American bitch” and “our leading bitch intellectual,” writers like Mary McCarthy and Dorothy Parker broke boundaries for the more overt feminist humorists of today like Amy Schumer, Wanda Sykes, Ali Wong, Hannah Gadsby, and Samantha Bee, who have turned the labels of bright, bold, bitchy, and baudy from a stigma into a rallying cry for future generations.

New York Women of Wit in the Twentieth Century is available for pre-order Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09571-4.html. Save 30% w/ discount code NR23.

0 notes

Text

Unlocked Book of the Month: Multilingualism and Mother Tongue in Medieval French, Occitan, and Catalan Narratives

Each month we’re highlighting a book available through PSU Press Unlocked, an open access initiative featuring scholarly digital books and journals in the humanities and social sciences.

About our November pick:

The Occitan literary tradition of the later Middle Ages is a marginal and hybrid phenomenon, caught between the preeminence of French courtly romance and the emergence of Catalan literary prose. In this book, Catherine Léglu brings together, for the first time in English, prose and verse texts that are composed in Occitan, French, and Catalan-sometimes in a mixture of two of these languages. This book challenges the centrality of "canonical" texts and draws attention to the marginal, the complex, and the hybrid. It explores the varied ways in which literary works in the vernacular composed between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries narrate multilingualism and its apparent opponent, the mother tongue. Léglu argues that the mother tongue remains a fantasy, condemned to alienation from linguistic practices that were, by definition, multilingual. As most of the texts studied in this book are works of courtly literature, these linguistic encounters are often narrated indirectly, through literary motifs of love, rape, incest, disguise, and travel.

Read more & access the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-03672-4.html

See the full list of Unlocked titles here: https://www.psupress.org/unlocked/unlocked_gallery.html

#Occitan#Middle Ages#French#France#Catalan#Literary Studies#Romance#Multilingualism#Linguistics#Linguistic Studies#PSU Press Unlocked

0 notes

Text

COVID-19, Anosmia, and the Importance of Smell

Hannah Gould and Gwyn McClelland, editors of Aromas of Asia, discuss anosmia as it relates to the COVID-19 pandemic, the tricky nature of olfaction, and where the phenomenon of smell as transnational exchange began.

Of the many serious, and still emerging, impacts of infection with COVID-19, anosmia, or a loss of the sense of smell, is less often discussed. Yet the condition is said to affect almost half of all diagnosed patients, and although most people regain olfaction within a month, for some, anosmia lingers, transforming how they eat, drink, and interact with the world. People may also experience a condition of paranosmia, or phantom, and often unpleasant, smells.

In the introduction to our new interdisciplinary edited collection, Aromas of Asia: Exchanges, Histories, Threats, we discuss how this phenomenon speaks to the tricky nature of olfaction: its profound impact in shaping one’s everyday experience of the world and the popular dismissal of its significance. For, perhaps it is only in losing a sense that we are troubled and thus realise its significance. Anosmia is a condition that demonstrates how smell (or its lack) moves between bodies and traverses scales, as an intimate, personal experience of the world created by the transnational movement of pathogens within a global pandemic.

Smell is thus a particularly generative phenomenon to draw upon when theorizing the dynamics of transnational exchange. And this particular transnational exchange of the pandemic, of course, began in Asia.

Western cultural hierarchies and intellectual traditions have tended to elevate the importance of vision, or hearing, while marginalizing senses including smell, taste, or touch. With a few notable exceptions, contemporary scholarship still remains strongly wedded to English-language or Western scholarly concerns and contexts.

Our new collection of essays relocates the discussion of olfaction to the Asian region, considering how the mobility of olfaction makes social worlds, identifies prejudices or threats, and implements power games of scent and odor. Wherever smell is interpreted as threat, and has potential to be used to violently enforce differences in ethnicity, gender, caste, and class, questions of smell can have serious implications.

We were concerned in this work to critique sensory colonialist tropes that align Asia and its peoples with more “debased” senses, thus resisting a dichotomy of “West-vision-logic” and “Asia-smell-emotion.” Where associated with smell, Asian peoples and cultures have been historically cast in two extremes: on the one hand heavily perfumed or “stinky,” and on the other overly sanitized, odorless or antiseptic. While examining and critiquing these sensory stereotypes, our collection engages with Asia as a heterogeneous and changing complex of scentscapes that have blended together and come apart throughout history. The boundaries of this region are not presumed to exist before olfaction but rather emerge through histories of sensory exchange.

Our contributors consider periods from antiquity to the present and examine various transnational contexts across East, Southeast, and South Asian regions. We do not claim the spread as representative or exhaustive, but the chapters provide a robust cross section of the “scentscapes” that traverse the region. Thus, incisive essays and careful research was essential to achieve the methodological richness and conversation between disciplines evidenced in this book. Besides the editors, the authors, in order of their contributions, are Lorenzo Marunucci, Peter Romaskiewicz, Qian Jia, Gaik Cheng Khoo, Jean Duruz, Gwyn McClelland, Shivani Kapoor, Aubrey Tang, Saki Tanada, Adam Liebman, and Ruth E. Toulson. The disciplines brought together in this volume include anthropology, history, film studies, fine arts, food studies, literature, philosophy, political studies, and religious studies.

Strong-smelling miasmas, or drifting clouds of noxious air, have been central to human understandings of disease transmission. Well after the emergence of germ theory, fear of smells in the form of miasma continues to this day. Some commentators used olfactory evidence in positioning Chinese “wet markets” as the site of origin for COVID-19 virus. For example, in one paper in The COVID-19 Reader (2021), the writer suggests that “a lack of hygiene [at wet markets] was obvious from the smells and scattered wastes.” From this olfactory experience, the authors describe their lack of surprise that a pandemic might emerge from this place. We compare this in our introduction to another study of 2020 that shows how freshness is constructed and valued in sensory experiences of markets within China. Perceiving smells or odors as threats can reinforce, especially during the pandemic, the alterity of Asia as the other to the West. COVID-19 illustrated how olfaction is an intimately embodied, individual experience, but also a social phenomenon traveling between bodies and communities—and around the globe. In our collection, Aromas of Asia, we focus on the interconnections of sensory worlds, but we do so by offering a transnational and located approach to scentscapes in Asia, even as they are founded on mobility and exchange.

Aromas of Asia: Exchanges, Histories, Threats is now available from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09541-7.html. Save 30% w/ discount code NR23.

#COVID-19#COVID 19#COVID19#Pandemic#Smell#Anosmia#Miasma#Olfactory#Scent#Asia#China#PSU Press#Penn State University Press#Penn State

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unlocked Book of the Month: The Moravian Graveyards of Lititz, Pa., 1744–1905

Each month we’re highlighting a book available through PSU Press Unlocked, an open access initiative featuring scholarly digital books and journals in the humanities and social sciences.

About our October pick:

Originally published in 1906 within the Transactions of the Moravian Historical Society, this volume contains the names, gravesite locations, and available personal details for 1,219 people interred at the Moravian graveyard in Lititz, Pennsylvania, between 1758 and 1905. Also included are 181 names of those interred at Saint James Graveyard in Lititz between the years 1744 and 1812. A map of the primary graveyard and a comprehensive name index add to the volume’s accessibility as a guide for visits and research.

Read more & access the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-06037-8.html

See the full list of Unlocked titles here: https://www.psupress.org/unlocked/unlocked_gallery.html

#Graveyard#Graveyards#Grave#Graves#Moravian#Pennsylvania#Pennsylvania History#PA History#Lilitz#1700s#1800s#1900s#PSUP Unlocked#PSU Press Unlocked

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unlocked Book of the Month: Pennsylvania Railroad

Each month we’re highlighting a book available through PSU Press Unlocked, an open access initiative featuring scholarly digital books and journals in the humanities and social sciences.

About our September pick:

In Pennsylvania Railroad, William Sipes provides a detailed history of the railroad, its construction, its management, and its various lines and their stations, starting with the first experimental track laid down in 1809 in Delaware County and continuing with the railroad’s westward expansion across the state. Sipes discusses the attractions and history of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s destinations, including landmarks in Philadelphia, Lancaster, Altoona, Pittsburgh, New York, and New Jersey. Published in 1875, this book explores the world of transportation in the nineteenth century and takes its readers on an informative journey through the state of Pennsylvania, following the trajectory of its railroad’s development.

Read more & access the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-06541-0.html

See the full list of Unlocked titles here: https://www.psupress.org/unlocked/unlocked_gallery.html

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

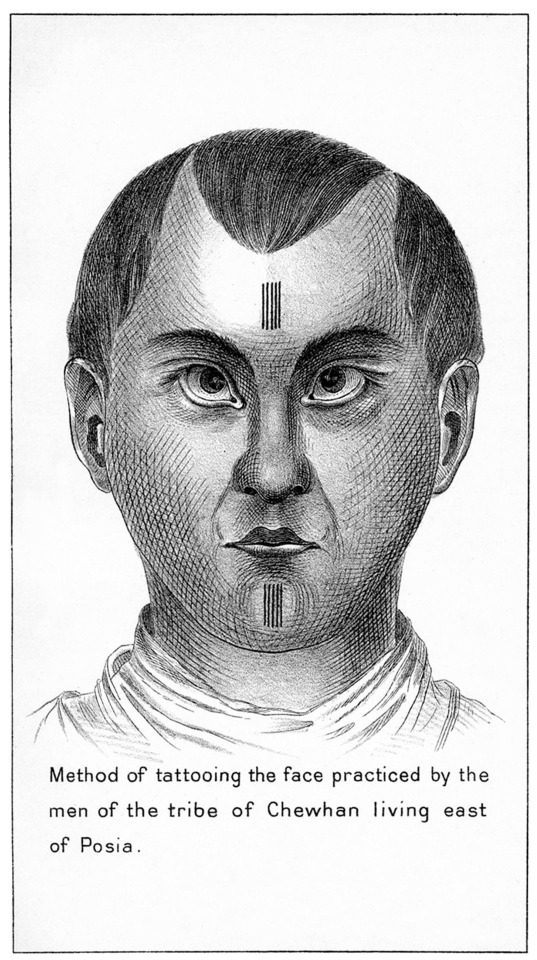

The Early Modern Tattoo

By the year 1800, tattooing had become a global phenomenon. Stigma authors Katherine Dauge-Roth and Craig Koslofsky discuss how and why tattoos circulated in the early modern world.

We think of tattooing as a contemporary phenomenon, now ubiquitous in the twenty-first century. We see elaborately tattooed skin daily—at the beach, in the street, and in the college classroom. Nearly half of all Americans under forty today have chosen to adorn their skin with tattoos, often multiple times, and tattoos mark the skin of people of all ages, backgrounds, and genders. But tattooing has been with us since prehistory as a locally defined but widespread and permanent form of cutaneous marking. This form of skin marking carries an extraordinary range of meanings and has traveled across diverse cultures, especially during the early modern period. The years 1450–1800 were a new age of dermal encounters, as forms of marking skin native to the Americas, Asia, Africa, Oceania, and Europe came into contact as never before. Cast simultaneously as a mark of belonging and of distinction, the tattoo held particular prominence as a sign of identity in this period of unprecedented global movement. Global tattooing practices, largely recorded in written archives by European travelers and colonists, but also preserved in archeological findings and oral histories, were an object of fascination, but also familiarity.

Native nations across the Americas practiced tattooing to communicate identity, commemorate valiant deeds, and signal honorable status long before the arrival of Europeans in the late fifteenth century. Using sharpened bird or fish bones and plant- or mineral-based dyes such as genipap, red lead, sap, or charcoal, Native Americans would prick a design into the skin and then rub dye or powder into the incisions, creating a permanent mark. Some European colonists in the Americas chose to be tattooed by Native people, often adopting the practice to fashion new hybrid identities for themselves. While some Europeans discouraged getting marked, seeing tattoos as a sign of “savagery,” French fur traders and military men making their lives in North America were especially open to receiving Native tattoos. Plant, animal, and celestial designs from Native American tradition were placed on their skin alongside crosses and coats of arms borrowed from European Christian tradition.

Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, and Chinese colonizers, on the other hand, were more hostile to Indigenous tattoo traditions. European and Chinese observers alike noted the “barbarity” of Indigenous Formosan tattooing when they reported on Taiwan in parallel seventeenth-century accounts, though Chinese officials also looked for signs of filial piety consistent with their own Confucian values. Spanish officials and Catholic missionaries worked hard to repress the rich tattoo traditions of the Philippines among the Indigenous Bizayas, reading marks on skin as essential and indelible signs of their inferior identity.

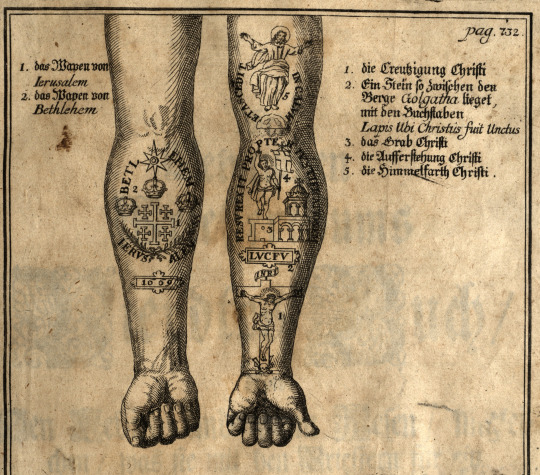

Whatever European colonists might have thought about the marking practices of Indigenous peoples around the globe, tattoos were well known to Europeans prior to these encounters. Indeed, tattoos were familiar in early modern Europe—and had been for centuries—as signs of identity, belonging, love, and piety. Though the Polynesian word tatau came into European languages only in the late eighteenth-century following the South Seas voyages of Bougainville and Cook, the practice of permanently marking the body through pricking and ink had long existed on the European continent. European travelers writing about Native American tattooing in the seventeenth century often referred their readers back to stories of elaborately painted Ancient Picts, indigenous to Britain and France. From their own time, they referenced devoted courtiers who wore their beloveds’ monograms permanently pricked on their arms, alchemists who inscribed their skin with astral characters to harness their power, and Holy Land pilgrims. In Jerusalem and Bethlehem, local Christians “marked” the bodies of Coptic, Armenian, and European pilgrims with scenes of Christ’s passion and representations of sacred sites. Pilgrims would choose from a range of woodblock designs that the tattoo artist would rub in charcoal and imprint on their arm. The tattooist would then use a series of fine needles bound together, dipped in an ink made of fine soot and ox gall, and prick along the lines of the stamped figure, finally washing it with wine, sometimes repeating the process. For European Holy Land pilgrims, tattoos commemorated their arduous travels, signaling their devotion and bravery. Given the pain they experienced—swelling and fever often lasting for days—they may also have imagined their tattoos as stigmata or a form of imitatio Christi.. Even today, Christians visiting Jerusalem can get marked at the Razzouk Tattoo shop, where Wassim Razzouk and his sons still use centuries-old wooden stamps passed down in his family for generations.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Europeans increasingly associated Indigenous forms of tattooing with cultural inferiority and tied tattoos in European traditions exclusively to criminals and sailors. This denial of the age-old use of the tattoo as a desirable and honorable global and European sign lasted until the “tattoo Renaissance” of the late twentieth century.

Stigma: Marking Skin in the Early Modern World is now available from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09442-7.html. Save 30% w/ discount code NR23.

19 notes

·

View notes