#U.S. Refugee Act (1980)

Text

Problems in U.S. Asylum System Help Promote Increases in U.S. Immigration

A lengthy Wall Street Journal article provides details on the well-known promotion of increases in U.S. immigration by the many problems in the U.S. asylum system. Here then is a summary of the basic U.S. law of asylum, the current U.S. system for administering such claims and a summary of the current problems with such administration.

The Basic Law of Asylum

On July 2, 1951, an international…

View On WordPress

#asylum law#Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees#Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees#REAL ID Act of 2005#refugee law#U.S. asylum officers#U.S. Board of Asylum Appeals#U.S. Congress#U.S. federal courts#U.S. immigration judges#U.S. Office of the Chief Immigration Judge#U.S. Refugee Act of 1980#U.S. State Department’s U.S. Refugee Admissions Program#U.S.-Mexico border

1 note

·

View note

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

November 13, 2023

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

NOV 13, 2023

In a speech Saturday in Claremont, New Hampshire, and then in his Veterans Day greeting yesterday on social media, former president Trump echoed German Nazis.

“In honor of our great Veterans on Veteran’s Day [sic] we pledge to you that we will root out the Communists, Marxists, Racists, and Radical Left Thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our Country, lie, steal, and cheat on Elections, and will do anything possible, whether legally or illegally, to destroy America, and the American Dream…. Despite the hatred and anger of the Radical Left Lunatics who want to destroy our country, we will MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN.”

The use of language referring to enemies as bugs or rodents has a long history in genocide because it dehumanizes opponents, making it easier to kill them. In the U.S. this concept is most commonly associated with Hitler and the Nazis, who often spoke of Jews as “vermin” and vowed to exterminate them.

The parallel between MAGA Republicans’ plans and the Nazis had other echoes this weekend, as Trump’s speech came the same day that Charlie Savage, Maggie Haberman, and Jonathan Swan of the New York Times reported that Trump and his people are planning to revive his travel ban, more popularly known as the “Muslim ban,” which refused entry to the U.S. by people from some majority-Muslim nations, and to reimpose the pandemic-era restrictions he used during the coronavirus pandemic to refuse asylum claims—it is not only legal to apply for asylum in the United States, but it is a guaranteed right under the Refugee Act of 1980—by claiming that immigrants bring infectious diseases like tuberculosis.

They plan mass deportations of unauthorized people in the U.S., rounding them up with specially deputized law enforcement officers and National Guard soldiers contributed by Republican-dominated states. Because U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) doesn’t have the space for such numbers of people, Trump’s people plan to put them in “sprawling camps” while they wait to be expelled. Trump refers to this as “the largest domestic deportation operation in American history.”

Trump’s people would screen visa applicants to eliminate those with ideas they consider undesirable, and would kick out those here temporarily for humanitarian reasons, including Afghans who came here after the 2021 Taliban takeover. Trump ally Steve Bannon and his likely attorney general, Mike Davis, expect to deport 10 million people.

Trump’s advisors also intend to challenge birthright citizenship, the principle that anyone born in the U.S. is a citizen. This principle was established by the Fourteenth Amendment and acknowledged in the 1898 United States v. Wong Kim Ark Supreme Court decision during a period when native-born Americans were persecuting immigrants from Asia. That hatred resulted in Wong Kim Ark, an American-born child of Chinese immigrants, being denied reentry to the U.S. after a visit to China. Wong sued, arguing that the Fourteenth Amendment established birthright citizenship. The Supreme Court agreed. The children of immigrants to the U.S.—no matter how unpopular immigration was at the time—were U.S. citizens, entitled to all the rights and immunities of citizenship, and no act of Congress could overrule a constitutional amendment.

“Any activists who doubt President Trump’s resolve in the slightest are making a drastic error: Trump will unleash the vast arsenal of federal powers to implement the most spectacular migration crackdown,” Trump immigration hardliner Stephen Miller told the New York Times reporters. “The immigration legal activists won’t know what’s happening.”

In addition to being illegal and unconstitutional, such plans to strip the nation of millions of workers would shatter the economy, sparking sky-high prices, especially of food.

For a long time, Trump’s increasingly fascist language hasn’t drawn much attention from the press, perhaps because the frequency of his outrageous statements has normalized them. When Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in 2016 referred to many Trump supporters as “deplorables,” a New York Times headline read: “Hillary Clinton Calls Many Trump Backers ‘Deplorables,’ and G.O.P.* Pounces.” Yet Trump’s threat to root out “vermin” at first drew a New York Times headline saying, “Trump Takes Veterans Day Speech in a Very Different Direction.” (This prompted Mark Jacobs of Stop the Presses to write his own headlines about disasters, including my favorite: “John Wilkes Booth Takes Visit to the Theater in a Very Different Direction.”)

Finally, it seems, Trump’s explicit use of Nazi language, especially when coupled with his threats to establish camps, has woken up at least some headline writers. Forbes accurately headlined yesterday’s story: “Trump Compares Political Foes to ‘Vermin’ On Veterans Day—Echoing Nazi Propaganda.”

Republicans have refused to disavow Trump’s language. When Kristen Welker of Meet the Press asked Republican National Committee chair Ronna McDaniel: “Are you comfortable with this language coming from the [Republican] frontrunner,” McDaniel answered: “I am not going to comment on candidates and their campaign messaging.” Others have remained silent.

Trump’s Veterans Day “vermin” statement set up his opponents as enemies of the country by blurring them together as “Communists, Marxists, Racists, and Radical Left Thugs.” Conflating liberals with the “Left” has been a common tactic in the U.S. right-wing movement since 1954, when L. Brent Bozell and William F. Buckley Jr. tried to demonize liberals—those Americans of all parties who wanted the government to regulate business, provide Social Security and basic welfare programs, fund roads and hospitals, and protect civil rights—as wannabe socialists.

In the United States there is a big difference between liberals and the political “Left.” Liberals believe in a society based in laws designed to protect the individual, arrived at by a government elected by the people. Political parties disagree about policy and work to change the laws, but they support the system itself. Most Americans, including Democrats and traditional Republicans, are liberals.

Both “the Left,” and the “Right” want to get rid of the system. Those on the Left believe that its creation was so warped either by wealth or by racism that it must be torn down and rebuilt. Those on the Right believe that most people don’t know what’s good for them, making democracy dangerous. They think the majority of people must be ruled by their betters, who will steer them toward productivity and religion. The political Left has never been powerful in the U.S.; the political Right has taken over the Republican Party.

The radical right pushes the idea that their opponents are “Radical Left Thugs” trying to tear down the system because they know liberal policies like Social Security, Medicare, environmental protection, reproductive rights, gun safety legislation, and so on, are actually quite popular. This weekend, for example, Trump once again took credit for signing into law the Veterans Choice health care act, which was actually sponsored by Senators John McCain (R-AZ) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and signed by President Barack Obama in 2014.

The Right’s draconian immigration policies ignore the reality that presidents since Ronald Reagan have repeatedly asked Congress to rewrite the nation’s immigration laws, only to have Republicans tank such measures to keep the hot button issue alive, knowing it turns out their voters. Both President Joe Biden and Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas have begged Congress to fund more immigration courts and border security and to provide a path to citizenship for those brought to the U.S. as children. They, along with Vice President Kamala Harris, have tried to slow the influx of undocumented migrants by working to stabilize the countries from which such migrants primarily come.

Such a plan does not reflect “hatred and anger of the Radical Left Lunatics who want to destroy our country.” It reflects support for a system in which Congress, not a dictator, writes the laws.

A video ABC News published tonight from Trump lawyer Jenna Ellis’s plea deal makes the distinction between liberal democracy and a far-right dictatorship clear. In it, Ellis told prosecutors that former White House deputy chief of staff and social media coordinator Dan Scavino told her in December 2020 that Trump was simply not going to leave the White House, despite losing the presidential election.

When Ellis lamented that their election challenges had lost, Scavino allegedly answered: “‘Well, we don’t care, and we’re not going to leave.” Ellis replied: “‘What do you mean?” Scavino answered: “The boss is not going to leave under any circumstances. We are just going to stay in power.” When Ellis responded “Well, it doesn’t quite work that way, you realize?” he allegedly answered: “We don’t care.”

*The GOP, or Grand Old Party, is an old nickname for the Republican Party.

—

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#history#“vermin”#TFG#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#GOP#immigration#authoritarianism#fascim#fascism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who we celebrate in this lecture series’ focus on the “Four Freedoms,” outlined in his 1941 State of the Union address all of the fears and the freedoms. He fully understood the political salience of fear. FDR knew that people could be paralyzed by the fear of poorly understood events. They were prone to the manipulation of their fears and thus intimidation and exploitation. If people were filled with fear, they were incapable of taking the necessary individual and collective action to deal with a disaster.

Now fear, of course, is a normal response to a real or perceived threat. All animals exhibit fear, both predators and prey. And a sense of fear is essential to prepare for risk and act in the case of danger ahead but fear is often engendered by something more imagined than real. We fear what we don’t know, not just what we do, like the danger of nuclear weapons.

In the case of real dangers, a healthy dose of fear is critical to living with their ever-present possibility. You can’t have freedom from danger, but you can have freedom from fear. There will always be hidden dangers, but you can do something about them. You can prepare yourself for danger, insure against danger. Freedom from fear is essential for personal and societal resilience in the face of peril.

This takes me back to my studies of Russian. The Russian word for insurance is actually based on this very concept that I’ve just outlined, the idea of protection from fear or strakh. The word “insurance” in Russian is proof or preparation against fear, strakhovaniye. And indeed, having insurance in any form helps to relieve fear through the knowledge that you are prepared for the inevitability of danger and the risk of something happening. You are ready to deal with it.

In contrast to this pleasing synergy between the word and its meaning, the Russian word for security is less satisfying and a lot more troubling. Security is something Vladimir Putin always craves, and states it is his imperative in everything that he does, including invading Ukraine. He’s invaded Ukraine to ensure Russia’s security by taking Ukraine off the map. Now, the Russian word for security is bezopasnost’ or literally, “without danger.” In effect, the Russian word for security is “safety” in absolute terms. This suggests that the Russian idea or concept of security seeks the impossible, the creation of a world without danger, where everyone can be completely safe at all times.

The sense of that kind of security or safety will always be false, as false as the words of leaders who promise it to themselves and their followers. In this conception of security, there can be no freedom from fear. Danger will always be there. It cannot be eliminated. And fear will also always be present because we can never be in complete control. We cannot have absolute safety; we can only have insurance and prepare ourselves to deal with danger.

Just as Vladimir Putin wants his version of security, he also wants control of events. Indeed, most of us would like the same thing. We are afraid of the sudden loss of control in our ever-complex world. At times of conflict, or when major societal changes happen rapidly and in combination, fear predominates. We are plunged into what the insightful scholar of the twentieth century, Fritz Stern, called “cultural despair.” Stern focused on the fears that roiled Germany in the turbulent period between World War I and World War II. He described cultural despair as the sense of loss, grievance, and anxiety that occurs when people feel dislocated from their communities and broader society, as everything and everyone shifts around them.

Cultural despair leads to populism in politics, and from there to authoritarianism, as Stern noted in tracking the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany. Populism and authoritarianism are rooted in fear; fear of loss, fears from the past and fears of the future, fears of the other, like refugees, migrants, people who are simply different, and people who might think differently from the mainstream. All these fears emerge when societies undergo change. Populism shaped European and U.S. politics in the 1920s and 1930s after World War I and the 1918 influenza epidemic and the Great Depression. It arose again in the 1960s and in the 1980s during generational and technological shifts. Vladimir Putin is a populist who came to power after a decade of political turmoil and economic collapse in Russia. Putin promised to provide security and safety, as well as prosperity, as long as Russians acquiesced to his ultimate authority.

And throughout history, fear has been used by more powerful people to prey on the weak during difficult times. Populists today, like Putin in Russia, Donald Trump in the United States, Narendra Modi in India, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, and also Xi Jinping in China, appeal to people who fear they have lost their livelihoods along with their identities and their cultural moorings at times of rapid social change and political and economic uncertainty. They present themselves as strongmen leaders who can restore order from the chaos.

Freedom from fear: A BBC Reith Lecture by Fiona Hill

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 4.2

1513 – Having spotted land on March 27, Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León comes ashore on what is now the U.S. state of Florida, landing somewhere between the modern city of St. Augustine and the mouth of the St. Johns River.

1755 – Commodore William James captures the Maratha fortress of Suvarnadurg on the west coast of India.

1792 – The Coinage Act is passed by Congress, establishing the United States Mint.

1800 – Ludwig van Beethoven leads the premiere of his First Symphony in Vienna.

1801 – French Revolutionary Wars: In the Battle of Copenhagen a British Royal Navy squadron defeats a hastily assembled, smaller, mostly-volunteer Dano-Norwegian Navy at high cost, forcing Denmark out of the Second League of Armed Neutrality.

1863 – American Civil War: The largest in a series of Southern bread riots occurs in Richmond, Virginia.

1865 – American Civil War: Defeat at the Third Battle of Petersburg forces the Army of Northern Virginia and the Confederate government to abandon Richmond, Virginia.

1885 – Canadian Cree warriors attack the village of Frog Lake, killing nine.

1902 – Dmitry Sipyagin, Minister of Interior of the Russian Empire, is assassinated in the Mariinsky Palace, Saint Petersburg.

1902 – "Electric Theatre", the first full-time movie theater in the United States, opens in Los Angeles.

1911 – The Australian Bureau of Statistics conducts the country's first national census.

1912 – The ill-fated RMS Titanic begins sea trials.

1917 – American entry into World War I: President Wilson asks the U.S. Congress for a declaration of war on Germany.

1921 – The Autonomous Government of Khorasan, a military government encompassing the modern state of Iran, is established.

1930 – After the mysterious death of Empress Zewditu, Haile Selassie is proclaimed emperor of Ethiopia.

1954 – A 19-month-old infant is swept up in the ocean tides at Hermosa Beach, California. Local photographer John L. Gaunt photographs the incident; 1955 Pulitzer winner "Tragedy by the Sea".

1956 – As the World Turns and The Edge of Night premiere on CBS. The two soaps become the first daytime dramas to debut in the 30-minute format.

1964 – The Soviet Union launches Zond 1.

1972 – Actor Charlie Chaplin returns to the United States for the first time since being labeled a communist during the Red Scare in the early 1950s.

1973 – Launch of the LexisNexis computerized legal research service.

1975 – Vietnam War: Thousands of civilian refugees flee from Quảng Ngãi Province in front of advancing North Vietnamese troops.

1976 – Prince Norodom Sihanouk resigns as leader of Cambodia and is placed under house arrest.

1979 – A Soviet bio-warfare laboratory at Sverdlovsk accidentally releases airborne anthrax spores, killing 66 plus an unknown amount of livestock.

1980 – United States President Jimmy Carter signs the Crude Oil Windfall Profits Tax Act.

1982 – Falklands War: Argentina invades the Falkland Islands.

1986 – Alabama governor George Wallace, a former segregationist, best known for the "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door", announces that he will not seek a fifth four-year term and will retire from public life upon the end of his term in January 1987.

1989 – Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev arrives in Havana, Cuba, to meet with Fidel Castro in an attempt to mend strained relations.

1991 – Rita Johnston becomes the first female Premier of a Canadian province when she succeeds William Vander Zalm (who had resigned) as Premier of British Columbia.

1992 – In New York, Mafia boss John Gotti is convicted of murder and racketeering and is later sentenced to life in prison.

1992 – Forty-two civilians are massacred in the town of Bijeljina in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

2002 – Israeli forces surround the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, into which armed Palestinians had retreated.

2004 – Islamist terrorists involved in the 11 March 2004 Madrid attacks attempt to bomb the Spanish high-speed train AVE near Madrid; the attack is thwarted.

2006 – Over 60 tornadoes break out in the United States; Tennessee is hardest hit with 29 people killed.

2012 – A mass shooting at Oikos University in California leaves seven people dead and three injured.

2014 – A spree shooting occurs at the Fort Hood army base in Texas, with four dead, including the gunman, and 16 others injured.

2015 – Gunmen attack Garissa University College in Kenya, killing at least 148 people and wounding 79 others.

2015 – Four men steal items worth up to £200 million from an underground safe deposit facility in London's Hatton Garden area in what has been called the "largest burglary in English legal history."

2020 – COVID-19 pandemic: The total number of confirmed cases reach one million.

2021 – At least 49 people are killed in a train derailment in Taiwan after a truck accidentally rolls onto the track.

2021 – A Capitol Police officer is killed and another injured when an attacker rams his car into a barricade outside the United States Capitol.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can You Seek Legal Sanctuary in a Church?

By Sonja Cutts, University of Iowa Class of 2026

July 6, 2023

For the past eight years, Hilda Ramirez and her son Ivan have lived in a Sunday school classroom. The makeshift home—at Austin, Texas’s St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church—is not where the two wanted to end up when they entered the United States in 2014. Fleeing domestic violence in their native Guatemala, Ramirez and her son crossed the U.S.-Mexico border into Texas, where U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detained them for almost a year. Once released, they lived in a shelter for several months. However, after a judge denied their asylum case, Ramirez moved with Ivan into St. Andrew’s, fearing deportation. (1)

Over the next few years, cases like Ramirez’s multiplied as the Trump administration enacted its aggressive immigration policies. Wanting to avoid deportation, some immigrants sought refuge in supportive congregations. News of these cases led to a growing "sanctuary movement" among places of worship, which opened their doors to the undocumented. These congregations were participating in only the most recent phase of an ancient practice, finely tuned to the Trump era. (2) Now that the dust of that era is settling, it’s worth asking one important question—what legal basis, if any, does church sanctuary have in the U.S.?

The History of Church Sanctuary

To answer that question, we must first return to its origins. In ancient Greece and Rome, many temples, shrines, and altars were viewed as inviolable areas that had to remain weapons-free. As a result, some religious spaces gained reputations as sanctuaries where lawbreakers and refugees could seek protection from those who sought to apprehend or harm them. The right of fugitives to take asylum in churches continued to be respected in Rome after its conversion to Christianity, becoming enshrined in Roman imperial law in 431 CE. (3) From there, the practice carried on in Christianity for over a millennia before being seriously challenged by the religious upheaval of the 16th century. By questioning the Catholic Church’s authority, The Protestant Reformation severely damaged the practice of legal sanctuary Roman Catholicism had held up for so long. (4)

However, in more recent times the concept of church sanctuary has been revived as a response to political persecution, human rights abuses, and unjust immigration policies. The modern sanctuary movement gained momentum during the 1980s, primarily in the United States, as churches opened their doors to refugees fleeing civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala. Inspired by religious teachings about compassion, justice, and hospitality, these places of worship offered shelter from deportation. This rise in church sanctuary took place during the Reagan administration, which declined to grant asylum to many Central American applicants. Once Ronald Reagan left office, the movement died down. However, it had already laid the groundwork for its next phase, which would begin in 2016 when Donald Trump was elected president on an anti-immigration platform. (5)

So, Is Any of This Actually Legal?

While church sanctuary was once extended to a wide variety of lawbreakers, modern congregations involved in the sanctuary movement primarily focus on sheltering undocumented immigrants. Because of this focus, much of the current discussion around the legality of church sanctuary centers around immigration law. Technically, in the United States it is illegal to harbor someone facing deportation. The Immigration and Nationality Act, enacted in 1952, makes it a federal crime to “knowing[ly] or in reckless disregard of the fact that an alien has come to, entered, or remains in the United States in violation of law… conceal, harbor, or shield from detection, such alien in any place, including any building or any means of transportation.” If convicted under this act, a person can be fined and sentenced to years in prison. (6) Additionally, there is no law prohibiting the arrest of undocumented immigrants at places of worship.

However, law enforcement and prosecutors are generally hesitant to crack down on those involved in church sanctuary. ICE is aware that their public approval will suffer if they start busting into otherwise peaceful, law-abiding places of worship and arresting those inside. (7) As a result, they generally avoid making arrests at “sensitive locations” like schools, hospitals, and churches. (8) That does not mean, though, that no one has ever faced legal trouble for sheltering immigrants in churches. In 1986, while the sanctuary movement was combating Reagan’s stringent immigration policies, a Catholic priest from Nogales, Arizona was convicted of concealing and harboring illegal aliens. (9) Despite facing prison time, he served only probation. (10)

Similar crackdowns occurred when the movement rose again to combat Trump’s immigration policies. During her years-long stay at St. Andrew’s, Ramirez was hit with massive civil fines for avoiding deportation. Starting in July 2019, the Trump Administration used a rarely enforced section of the Immigration and Nationality Act to issue large financial penalties to Ramirez and other immigrants sheltering in places of worship. However, when Joe Biden took office in 2021, his administration canceled the existing fines and stopped issuing new ones. The Biden administration also recently granted four targets of the fines—including Ramirez—temporary protection from deportation for three years. (11)

While this development is undoubtedly a victory for the sanctuary movement, one cannot help but wonder what will happen to Ramirez when her temporary protection expires. Since church sanctuary operates within an uncertain legal framework in the United States, different administrations have taken varying approaches towards it throughout the years. Though Biden is appears accepting of the practice, our next president may not be. However, given the long history of church sanctuary and its persistence over time, it is likely that the tradition will continue to endure despite the legal challenges it faces.

______________________________________________________________

Dias, I. (2019). The Fear—and Hope—of Living in Sanctuary. The Texas Observer. https://www.texasobserver.org/hilda-ramirez-sanctuary-texas/

Shimron, Y. (2017, November 29). Resisting Trump, churches give sanctuary to immigrants facing deportation. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2017/11/29/resisting-trump-churches-give-sanctuary-immigrants-facing-deportation/904889001/

Bond, S. (2017, March 28). Defending The Ancient Concept Of The Sanctuary City. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2017/03/28/defending-the-ancient-concept-of-the-sanctuary-city/?sh=73dc463b3aaa

Rabben, L. (2016). Sanctuary and Asylum: A Social and Political History. University of Washington Press.

Garcia, M. (2019, July 30). More Central American migrants take shelter in churches, recalling 1980s sanctuary movement. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/more-central-american-migrants-take-shelter-in-churches-recalling-1980s-sanctuary-movement-120535

Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1324 (1952). http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid%3AUSC-prelim-title8-section1324&num=0&edition=prelim#0-0-0-322

Hanna, J. (2017, February 17). Can churches provide legal sanctuary to undocumented immigrants? CNN https://www.cnn.com/2017/02/17/us/immigrants-sanctuary-churches-legality-trnd/

Protected Areas and Courthouse Arrests. (n.d.). U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. https://www.ice.gov/about-ice/ero/protected-areas

Curry, B. (1986, May 2). 8 of 11 Activists Guilty in Alien Sanctuary Case : Defiant Group Says 6-Month Trial Hasn’t Ended Movement to Help Central American Refugees. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-05-02-mn-3211-story.html

Altman, M. L. (1990). The Arizona Sanctuary Case. Litigation, 16(4), 23–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29759415

Rose, J. (2023, June 21). Four immigrants who sought sanctuary in churches no longer face deportation. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/21/1183528143/four-immigrants-who-sought-sanctuary-in-churches-no-longer-face-deportation

0 notes

Text

Why You Should Speak to a Russian Immigration Attorney Right Away?

Are you a Russian citizen who has been detained or is seeking asylum for Russian Immigration Attorney speakers? If you’re currently in the U.S. and in California, you’ll need to speak to a Russian immigration lawyer immediately.

This is indeed a tough time for Russians, given the escalation of the Ukrainian conflict and the pressure they’re experiencing in their country. If you are dealing with this situation currently, you need to retain the services of a legal advocate.

Therefore, you need to set aside time to speak to a Russian-speaking immigration attorney – someone who can help you legally who speaks your language, and who understands what you may be going through.

Doing so will help you find a place where you can exert your rights for free expression and autonomy. Trying to seek asylum from your homeland is indeed difficult. That’s because you have to get used to a new culture and follow some complicated steps for entry.

Therefore, you cannot afford to take these steps without the help of a bilingual lawyer. By speaking to someone who speaks Russian and English, and who understands your immigration concerns, you can breathe easier after being detained, or when making the transition to your new home.

What is Asylum and How Is It Different from Being a Refugee?

You can make an asylum claim in one of three ways. However, before you do so, it helps to define the word, “asylum” first. Asylum grants protection to Russians who are already in the U.S. or who have already landed at a U.S. border and are considered refugees.

According to the United Nations, a “refugee” is someone who has left their homeland and can’t obtain protection in their country because of the fear of persecution or because they were persecuted in the past because of their race, nationality, religion, or membership in a specific political or social group.

This definition was extended by the U.S. Congress through the passage of the 1980 Refugee Act. Technically, asylum, in this case, is considered discretionary. That means you may still be denied asylum even if you meet the qualifications of a refugee.

An asylee is someone who has received protection from having to return to their home country. In addition, they can work in the U.S. or may apply for a social security number. They may also request permission to travel outside the country or petition family members to live with them in the U.S. Some asylees are eligible for governmental programs, such as Refugee Medical Assistance or Medicaid.

As an asylee from Russia, you may apply for legal permanent residence in the U.S. This involves submitting an application or a green card. After you obtain this status, you have to wait four years to submit an application for citizenship.

The primary difference between a refugee and an asylee is where they’re submitting an application. While a refugee applies for protection in their homeland before entering the U.S. as a refugee, an asylee asks for protection and is given asylum inside the U.S. Again, he or she has either entered the U.S. or is at a U.S. port of entry.

The 3 Asylum Processes

As an asylum seeker, your Russian immigration attorney will point you to one of three different types of processes, as follows:

1. Affirmative Asylum

Anyone who is not involved in removal proceedings, or who is categorized as an “unaccompanied child” who is in removal proceedings. may apply for affirmative asylum. They can do this through the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) department.

If the application is not granted, the applicant is referred to the immigration court to go through removal proceedings. At this point, they may renew their asylum request through a defensive asylum process. During the defensive process, they’ll appear before an immigration judge.

2. Defensive Asylum

If you’re going through removal proceedings as an immigrant, you may apply for Russian asylum defensively. Your Russian-speaking immigration lawyer will do this by submitting an application through the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), which is part of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ).

In simple terms, defensive asylum is applicable when the applicant is facing removal from the U.S. Unlike the criminal court system in the U.S., the EOIR will not provide the applicant with legal counsel. That is why you need to retain the services of a Russian immigration attorney if you’re seeking Russian asylum in the U.S.

2. Expedited Asylum

A Russian native who wishes to immigrate to the U.S., who is taken into custody within 14 days of entry, is placed into expedited removal proceedings. This process allows a USCIS officer to review an asylum claim before the applicant is placed into a formal removal process. Anyone who goes through expedited asylum, whose claim is denied, must go through removal proceedings and hearings in the U.S. immigration court.

Your Russian immigration lawyer has the burden of proving that you meet the legal definition of a refugee. This includes providing evidence that you have suffered persecution or feel threatened or fearful about returning to Russia. Your testimony will be used to help determine your case for asylum status.

When Applications Are Denied

Certain factors may prevent you from becoming an asylee. If you do not apply for asylum within a year of U.S. entry, you will not be granted asylum. Also, if the U.S. feels you pose a real threat to the government, you’ve committed a violent crime, or persecuted others yourself, your application for asylum will be denied.

Speeding Up the Process

To apply for U.S. protection, you need to make sure you follow all the steps and stay committed to the process. You’ll slow everything down if you do the following:

Reschedule an interview

Request a change of venue

Neglect to show up for a biometric screening

Add a large amount of additional documentation to your application

Provide insufficient supporting documents

Avoid appearing at a hearing

Contact the Paniotto Law Firm in Los Angeles Today

To ensure you receive asylum through these difficult times, contact a Russian immigration lawyer for assistance with your application. If you feel you’ll put yourself in danger by returning to Russia, you need to speak to an attorney right away. To ensure you get the needed assistance, contact the Paniotto Law Firm. Call 213-534-1824 immediately.

0 notes

Text

Historical Way of How Vietnamese People Came To the US

January 01, 2016 · 2.07am

After Saigon fell to North Vietnamese forces on April 30, 1975, about 125,000 Vietnamese fled their country. Operation New Life and Operation Baby Lift helped around 111,919 Vietnamese refugees and orphans to leave while over 90,000 of those resettled in the United States.

Have you heard about “boat people” before? That is the name of the estimated 1 to 2 million Vietnamese people who left Vietnam illegally and dangerously by boat in 1978 to the mid-1980s. The dangers came from e. g. overcrowded vessels and environmental perils. Many fell victim to pirates or were lost at sea.

Because of the high death tolls, the “United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees” (UNHCR) helped refugees to emigrate from their original country for the first and only time through the Orderly Depart (ODP). The U.S. government allowed the immigration of Vietnamese to the United States due to the hardships endured by the boat people and the Geneva conference on Indochinese Refugees on June 14, 1980. To qualify for immigration to the U.S., Vietnamese people had to fall under one of the following categories:

- Family unification

-�� Former U.S. employee

- Former re-education camp detainee

There was a subprogram, the Humanitarian Operation (HO), designated for the last-mentioned category. ODP ended in 1994 and helped over 500,000 immigrants. A renewal of the ODP agreement and McCain Amendment was signed by the U.S. and Vietnam in 2005. The McCain Amendment allowed the children from former re-education camp prisoners to immigrate with their parents. The renewals ended in 2009.

The Amerasian Homecoming Act was passed by the U.S. Congress in 1987 and allowed Vietnamese children with American fathers to immigrate to the U.S. and approximately 23,000 to 25,000 Amerasians, as well as 60,000 to 70,000 of their relatives, immigrated based on that.

0 notes

Video

youtube

The Truth About the U.S. Border-Industrial Complex

The story you’ve heard about immigration, from politicians and the mainstream media alike, isn’t close to the full picture. Here’s the truth about how we got here and what we must do to fix it.

A desperate combination of factors are driving migrants and asylum seekers to our southern border, from Central America in particular: deep economic inequality, corruption, and high rates of poverty — all worsened by COVID-19.

Many are also fleeing violence and instability, much of it tied to historic U.S. support for brutal authoritarian regimes, right-wing paramilitary groups, and corporate interests in Latin America.

Some long-term consequences of this U.S. involvement have been the rise of violent transnational gangs and drug cartels, as well as the internal displacement of hundreds of thousands of people.

And thanks to lax U.S. gun laws and export rules, a flood of firearms that regularly flows south makes this violence even worse.

In other words, the United States is very much part of the root of this problem.

Meanwhile, climate change-fueled natural disasters like droughts and hurricanes have led to widespread food insecurity in Central America, forcing thousands to migrate or risk starvation.

Some politicians want you to believe the way to address this humanitarian tragedy is to double down on border security and build walls to deter people from coming.

They’re wrong.

Several administrations have tried this approach. It’s failed every time. A recent study found that increased prosecutions and incarceration did not deter migration, but instead clogged courts, shifted resources from more serious cases and stripped people of due process.

The expansion of this militarized border apparatus and the increased criminalization of crossings has forced immigrants and asylum seekers to take riskier routes where they face extortion, assault, and even death.

The true beneficiaries have been the corporations who profited from the militarization of the border.

Between 2008 and 2020, the federal government doled out an astounding $55 billion in contracts to this border-industrial complex. Billions have been spent on everything from Predator drones to intrusive biometric security systems. Immigration enforcement budgets have more than doubled in the last 13 years, and since 1980, have increased by more than 6,000%.

Let’s be clear: What’s really out of control at the border is our spending on the border-industrial complex, which has done nothing but increase human suffering without dealing with the root causes of migration.

So what can we do?

Begin by acknowledging the role U.S. policies have played, and build a positive, sustained relationship with our Mexican and Central American neighbors to reduce economic inequality, uplift the marginalized, and uphold democratic ideals.

Donald Trump’s abrupt and arbitrary cancelling of crucial aid to the Northern Triangle nations of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador is the opposite of what we should be doing.

We must also ensure that aid doesn’t benefit transnational corporations and local oligarchs. Our goals must instead be aligned with the calls of local labor unions, environmental defenders, and agricultural movements to improve conditions so people are not forced to migrate in the first place.

And we should seek to reverse the militarization of borders in Central America, and instead help build a system that respects the human rights of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees.

Here at home, this means shifting away from the wasteful and violent militarization of our own borders, and ending the corporate profiteering it enables.

We need more asylum specialists, social workers, lawyers, and doctors at the border — not soldiers and walls.

And we must never again allow the inhumane and ineffective policies that resulted in the separation and detention of families and their children.

We must embrace the values we claim as our own, and never again allow a presidential administration to arbitrarily shrink the number of refugees accepted into the U.S. each year to almost none.

Congress should expand legal avenues of immigration, along with a roadmap to citizenship for undocumented immigrants already here — a policy with broad public support.

It’s not enough to roll back the cruel and xenophobic policies of our past. Most of us now living in America are the descendants of refugees, asylum-seekers, and immigrants. This new generation should be treated in ways that are consistent with our most cherished ideals.

Now is the time to act.

#immigration#immigration reform#Mexican Immigrants#immigrants from Central America#u.s. immigration and customs enforcement#video#videos

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bisexual Refugees & Asylum Seekers

Particular Social Groups

It is well settled in international refugee law that non-citizens facing persecution abroad on account of their sexual orientations are eligible for refugee status?4 The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, however, does not explicitly include sexual orientation. The Convention defines a refugee as any person who "owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country."

Although persecution on grounds of either religion or political opinion presents avenues for securing refugee status that are, in principle, open at least to some sexual minorities facing hetero-normative persecution, it is much more common for sexual minority refugee claimants to argue that they meet the refugee definition because they face persecution on grounds of their 'membership in a particular social group.'

One of the leading cases on what exactly constitutes a 'particular social group' is the Canadian Supreme Court decision, Ward v. Canada. In Ward, Justice La Forest explained that there were three distinct types of 'particular social groups' for the purpose of the refugee definition:

(1) groups defined by an innate or unchangeable characteristic;

(2) groups whose members voluntarily associate for reasons so fundamental to their

human dignity that they should not be forced to forsake the association; and

(3) groups associated by a former voluntary status, unalterable due to its historical

permanence. [x]

Sexual orientation is immutable; however, it is a common misconception that bisexuality is an exception to that rule. As misunderstood as bisexuality is, it is exceedingly difficult to prove that our sexual orientation is immutable. Our experiences are considered evidence of mutable sexuality.

Bisexual claimants often find it impossible to prove their membership of a ‘particular social group’. The fluidity bound up with bisexuality and the lack of acceptance of bisexual identities is at odds with the ‘immutability’ assumption of sexual orientation models.

Moreover, bisexuals are often not able to prove that ‘their’

group is sufficiently ‘visible’ and ‘recognisable’ for the purpose of legally qualifying as a ‘particular social group’. Visibility is a chief criterion for the definition of ‘a particular social group’ in many asylum jurisdictions, including US refugee law. The burden of having to prove ‘visibility’ creates a particular predicament for bisexuals as a group for different reasons (some may have been married, there is a lack of a recognisable ‘bisexual culture’ in most countries, etc.). [x]

There are no precedential asylum claims recognizing bisexual people as a particular social group (PSG). [x]

The Importance of “Particular Social Group” to Refugee Protection

To receive asylum in the United States, one must be a “refugee.” That term, drawn from an international convention to which the United States is a party (the 1967 Protocol to the Refugee Convention), requires a “well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.” In the United States, the Refugee Act of 1980, incorporated into the Immigration and Nationality Act, tracks that language. Because many – if not most – Central American asylum seekers are not seen as being persecuted for their race, religion, nationality, or political opinion (U.S. courts being reluctant to recognize feminism and opposition to gang rule as political opinions), an ability to show persecution on account of PSG membership often means the difference between life and death. [x]

Bisexual Experiences

Bisexual refugee claimants' experience, while varying to some degree across host states, shares two major features: (1) their presence in the host states' refugee jurisprudence is largely invisible and (2) they face extremely low refugee claim success rates. Both these features are evident in the experience of bisexual refugee claimants in three major host states: Canada, the United States, and Australia.

Canada

According to data acquired through a formal Access to Information request regarding refugee determinations by the IRB in 2006, bisexual refugee claims made up approximately

8% of sexual minority refugee claims decided by the IRB in 2006 (44 out of 577 decisions). The success rate for sexual minority claimants (58%) exceeded the average success rates at

the IRB for the year (54%). However, the success rate for bisexual refugee claimants (39%) was significantly lower. It is, moreover, worth noting that while the success rates for gay male and lesbian claimants were virtually identical (60%), cases involving gay

men (424) significantly outnumbered cases involving lesbians (100). In cases involving bisexuals, male claimants (33) once again outnumbered female claimants (11), but whereas success rates for gay and lesbian claimants matched closely, success rates for male bisexual claimants (33%) were lower than those for female bisexual claimants (55%).

United States

As with the Canadian data, the grant rate for bisexuals (5%) was significantly lower than the rate for gay men and lesbians (17%) in cases where the final outcomes were reported to the ADP.

Australia

A study of Australian sexual minority refugee determinations from

1994 to 2000, undertaken by Jenni Millbank and Catherine Dauvergne, identified 204 sexual minority refugee determinations, out of which 161 involved men and 43 involved women. In only two of the identified cases 'the claimants self-identified as "bisexual" in their applications.' Moreover, in these two cases the Australian Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT), 'rather than considering bisexuals as a particular social group, assumed the applicants to be homosexual.' The authors of the study also identified two further cases where the applicants were identified by the RRT as either bisexual or ambiguous in their sexuality. In none of these four cases - all of which involved men - did the applicant succeed in securing refugee status. [x]

The Gay Closet

Bisexuals seeking asylum are often encouraged to apply as homosexual rather than bisexual.

I learned that some individuals who have been seeking asylum as gay were trying to hide their attraction to more than one sex or gender. [x]

My lawyer even asked me if I would consider seeking asylum as a lesbian because it would “improve my chances” – like it was a choice I could make. [x]

Unfortunately, any history of other-sex relationships will discredit your case, even if you do apply as a bisexual.

I found that many activists in this field erase bisexuality and argue that if an asylum seeker is or has been in sexual or romantic relationships with the other sex, it can mean that they are lying about their attraction to their same sex. [x]

Fatal Consequences

This is an issue of life or death.

A bisexual Pakistani woman, who we will call Fatina, was beaten to death days after being deported in 2015. She was 22. Having gone to France to study, she discovered her identity and a girlfriend. She wished to claim asylum and remain in France, free to be herself. Her claim was rejected on the basis the asylum officers did not believe her. Fatina was technically engaged to be married to a man in Pakistan. Fatina’s sister told GSN: ‘Our uncle had read what she posted on Facebook. He saw a picture of Fatina and her girlfriend kissing. ‘On Fatina’s return, he prepared a “welcome party” of many of his friends. She died in hospital days later from multiple skull fractures.’ [x]

Asylum officers often ask: "Why can't you just go home and enter into an other-sex relationship?"

If only it were that easy. As soon as your sexual minority status is discovered, it makes no difference whether you are homosexual or bisexual.

‘Very few people in my country or in African countries can differentiate between LGBT. They term it as gay,’ Kirumila Hamid, a bisexual Ugandan appealing his failed asylum claim in the UK, said. ‘If you say you are transgender, bisexual, whatever – you’re just gay. They can’t tell the difference. In our countries it is very hard to say “I’m bisexual.” Gay is the general term.’

Grace, a bisexual Nigerian woman who is appealing her asylum rejection in Canada, agrees. ‘Once you are considered a gay, there’s nothing else that can change their minds. You can’t just explain it,’ she said.

When Grace revealed her sexuality to her husband, he raped her repeatedly to ‘clean away the sickness’.

Hamid, who was being blackmailed before coming to the UK, fears mob violence or even death if he is returned to Uganda. [x]

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

What My Korean Father Taught Me About Defending Myself in America

Born in 1939 during what would be the last years of the Japanese colonial occupation of Korea, my father, Choung Tai Chee, also called Charles or Chuck or Charlie, came to the United States in 1960. He was flashy, cocky, unafraid, it seemed, of anything. Wherever we were in the world, he seemed at home, right up until near the end of his life, when he was hospitalized after a car accident that left him in a coma. Only in that hospital bed, his head shaved for surgery, did he look out of place to me.

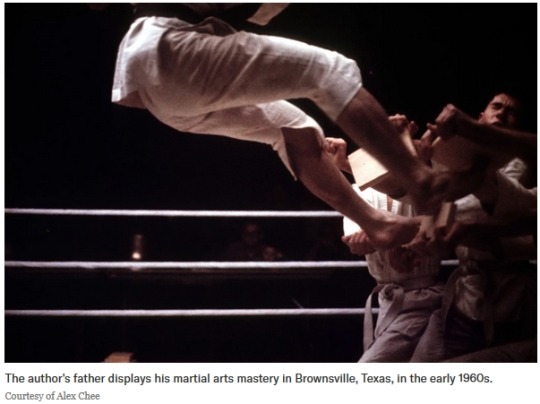

A tae kwon do champion by the age of 18 in Korea, he had begun studying martial arts at age 8, eventually teaching them as a way to put himself through graduate school, first in engineering and then oceanography, in Texas, California, and Rhode Island. He loved the teaching. The rising popularity of martial arts in the 1960s in Hollywood meant he made celebrity friends like Frank Sinatra Jr., Paul Lynde, Sal Mineo, and Peter Fonda, who my father said had fixed him up on a date with his sister, Jane, in the days before Barbarella. A favorite photo from his time in Texas shows him flying through the air, a human horseshoe, each of his bare feet breaking a board held shoulder high on each side by his students.

When I complained about my wet boots during the winters growing up in Maine, he told me stories about running barefoot in the snow in Korea to harden his feet for tae kwon do. His answer to many of my childhood complaints was usually that I had to be tougher, stronger, prepared for any attack or disaster. The lesson his generation took from those they lost to the Korean War was that death was always close, and I know now that he was doing all he could to teach me to protect myself. When I cried at the beach at the water’s edge, afraid of the waves, he threw me in. “No son of mine is going to be afraid of the ocean,” he said. When I first started swimming lessons, he told me I had to be a strong swimmer, in case the boat I was on went down, so I could swim to shore. When he taught me to body-surf, he taught me about how to know the approach of an undertow, and how to survive a riptide. When I lacked a competitive streak, he took to racing me at something I loved—swimming underwater while holding my breath. I was an asthmatic child, but soon, intent on beating him, I could swim 50 yards this way at a time.

For all of that, he was an exceedingly gentle father. He took me snorkeling on his back, when I was five, telling me we were playing at being dolphins. There he taught me the names of the fish along the reef where we lived in Guam. He would praise the highlights in my hair, and laugh, calling me “Apollo.” And as for any pressure regarding my future career, he offered something very rare for a Korean man of his generation. “Be whatever you want to be,” he told me. “Just be the best at it that you can possibly be.”

Only when I was older did I understand the warning about being strong enough to swim to shore in another context, when I learned the boat he and his family had fled in from what was about to become North Korea nearly sank in a storm. In Seoul as a child, he scavenged food for his family with his older brother, coming home with bags of rice found on overturned military supply trucks, while his father went to the farms, collecting gleanings. His attempts to teach me to strip a chicken clean of its meat make a different sense now. I had thought of him as an immigrant without thinking about how the Korean War made him one of the dispossessed, almost a refugee, all before he left Korea.

When I began getting into fights as a child in the U.S., he put me into classes in karate and tae kwon do for these same reasons. He loved me and he wanted me to be strong. I just wasn’t sure how I was supposed to take on a whole country.

We moved to Maine in 1973, when I was six years old. My father had taken us back to Korea after I was born, to work for his father, and then moved us around the Pacific—from Seoul to the islands of Truk, Kawaii, and Guam, in his and my mother’s attempts to set up a fisheries company. Maine was his next experiment, and not coincidentally, my mother’s home state. On my first day of the first grade, in the cafeteria, after a morning spent in what seemed like reasonably friendly classes, my troubles began when I went up to take an empty seat at a table and the blond haired, blue-eyed white boy seated there looked up with some alarm and asked me, “Are you a chink?”

“What’s a chink?” I asked, though I knew it wasn’t a compliment. I had never heard this word before.

“A Chinese person. You look like a chink. Is that why your face is so flat?”

This was also the first day I can remember being insulted about my appearance.

“I am not Chinese,” I said that day, naively. In a few years I would learn I was in fact part Chinese, 41 generations back, but at that moment, I tried to explain to him about how I was half Korean, a nationality and situation he had never heard of before. Half of what? And so this was also the first day I had to explain myself to someone who didn’t care, who had already decided against me.

He was a white boy from America, and he was repeating insults that seem to me to have come from a secret book passed out to white children everywhere in this country, telling them to call someone Asian “Chink,” to walk up to them, muttering “Ching-chong, ching-chong.” To sing a song, “My mother’s Chinese, my father’s Japanese, I’m all mixed up,” pulling their eyes first down and then up and then alternating up and down.

I was struck, watching Minari a few months ago, when the film’s Korean immigrant protagonist, David, is asked by a white boy in Arkansas in the 1980s why his face is so flat. “It’s not,” David says, forcefully—so many of us have this memory of someone saying this to us and responding that way. Why did a boy in Arkansas and a boy in Maine, in their small towns thousands of miles apart, before the internet, each know to make this insult?

When I got home from that first day at school, I asked my mother what the word “Chink” meant, and she flinched and covered her mouth in concern.

“Who said that to you?” she asked, and I told her. I don’t remember the conversation that followed, just the swift look of concern on her face. The sense that something had found us.

I was the only Asian-American student at my school in 1973, and the first many of my classmates had ever met. When my brother joined me at school three years later, he was the second. When my sister arrived, four years after him, she was the third. My mother is white, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed American, born in Maine to a settler family. I have six ancestors who fought in the Revolutionary War, but none of them had to fight this. I don’t know how to separate the teasing, harassment, and bullying that marked my 12 years of life there from that first racist welcome. It makes me question whether I really had a “temper” as a child, as I was told, or whether I was merely isolated by racism among racists, afraid and angry?

My father dealt with racism throughout most of his life by acting as if it had never happened—as if admitting it made it more powerful. He knew bullies loved to see their victims react and would tell me to not let what they said upset me. “Why do you care what they think of you?” he would say, and laugh as he clapped me on the shoulder. “They’re all going to work for you someday.”

“Don’t get even, get ahead,” was another of his slogans for me at these times. As if America was a race we were going to win.

Two decades after his death, writing in my diary while on a subway in New York City, I began counting off all of my activities as a child—choir, concert band, swimming, karate and tae kwon do, clarinet, indoor track, downhill and cross country skiing—and I asked myself if my parents were trying to raise Batman. Then I looked down to the insignia on my Batman t-shirt, and I laughed.

These lessons my father gave me—to be the best you can be, to fight off your enemies and defeat them, to swim to safety if the boat sinks, and in general toughen yourself against everything that would harm you—these I had absorbed alongside certain unspoken lessons, taken from observing his life as a Korean immigrant. To have two names, one American, known to the public, and one Korean, known only to a few intimates; to get rid of your accent; and to dress well as a way to keep yourself above suspicion. Did I need to train like a superhero just to be a person in America? Maybe.

But if I thought of superheroes, it was because my father was like one to me, training me to be like him.

One legend I heard about my father when I was growing up is the story of a night he was being held up at gunpoint, while he was unpacking his car. Whoever it was asked him to shut the trunk and turn around and raise his hands in the air. He agreed to, slamming the car trunk down so forcefully, he sank his fingertips into the metal.

By the time he turned around, the would-be stick-up artist was gone.

He would often ask me and my brother to punch him, as hard as we could, in his stomach. He was proud of his abdominal strength—it was like punching a wall. We would shake our hands, howling, and he would laugh and rub our heads. One time he even used it as a gag to stop a bully.

A boy on my street had developed the habit of changing the rules during our games if his team started losing. We had fights over it that could be heard up and down the street, and one day I chased him with a Wiffle bat, him laughing as I ran. My father stepped in the next time he tried to change the rules during a game and prevented it, telling him all games in his yard had to have the same rules at the beginning as the end—you couldn’t change them when you were losing. When the boy got mad, he said, “I bet you want to hit me, you should hit me. You’ll feel better. Hit me right here, in the stomach, as hard as you can.”

The boy hauled off and punched my dad in the stomach. I knew what was coming. The boy went home crying, shaking his hand at the pain. His mom came over and they had a talk. The rule-changing stopped.

I tried teasing my classmates back after being told to by my father. Stand-up as self-defense requires practice, though: During a “Where are you from?” exercise in the second grade, I told my classmates and teacher I had “Made in Korea” stamped on my ass, which elicited shocked laughter and a punishment from my teacher. I remember the glee when I called a classmate an ignoramus, and he didn’t know what it meant—and got angrier and angrier when I wouldn’t tell him, demanding that I explain the insult. When told to go back to where I came from, I said, “You first.”

Increasingly, I just hid, in the library, in books. When given detention, I exulted in the chance to be alone and read. I was an advanced student compared to my classmates, due in part to my mother being a schoolteacher, and I learned to make my intelligence a weapon.

The day several boys held me down on my street and ran their bicycles over my legs, to see if I could take it, as if maybe I wasn’t human, that felt like some new horrible level. I don’t remember how that ended or if I ever told anyone, just the feeling of the bicycle tires rolling over the skin of my legs. The day I bragged about my father being a martial artist to my classmates, they locked me in the bathroom and told me to fight my way out with kung fu, calling me “Hong Kong Phooey,” after the cartoon character, as they held the door shut. This was the fourth grade. After I got out of that bathroom and went home, I told my father about it, and he told me it was time to take tae kwon do. I had to learn to defend myself.

I would never be like him, never break boards like him, but for a while, I tried. I still cherish the day he gave me my first gi and showed me how to tie it. I learned I had a natural flexibility, which meant I could easily kick high, and I took pride in my roundhouse and reverse roundhouse kicks. But after a few years, my father took issue with a story he’d heard about my teacher’s arrogance toward his opponents, and he pulled me out of the classes. “It is very dangerous to teach in that spirit,” he told me. And he said something I would never forget. “The best fighter in tae kwon do never fights,” he said. “He always finds another way.”

I have thought about this for a long time. For the ordinary practitioner, tae kwon do and karate prepare you to go about your life, aware of what to do in case of assault. They offer no guarantee, just chances for preparedness in the face of the violence of others as well as the violence within yourself. At the time I felt my father was describing the responsibility that comes with knowing how to hurt someone, but I came to understand it as a principled if conditional non-violence, which, in this year of quarantine and rising racist violence, is one of the clearest legacies he left to me.

Like many of us, I have been trying to write about these most recent attacks on Asian-Americans, some of them in my old neighborhood in New York, and I keep starting and stopping. How do we protect ourselves and those we love? Can writing do that? I know I learned to use my intelligence as a weapon to keep myself safe from racists, starting as a child, and suddenly it doesn’t feel like enough. The violence is like a puzzle with many moving parts, but the stakes are life and death. “You’re really going to homework your way through this one?” I keep asking myself. The people attacking Asians and Asian Americans now are like the boy I met on my first day in the first grade. They don’t care whether or not we are actually Chinese—the primary experience Asian Americans have in common is mis-identification. The person who gets a patriotic ego boost off of calling me a “chink” isn’t going to check if they’re right about me, and I don’t imagine they’ll stop their fist or their gun if I say, “You’re just doing this because of America’s history of war in Asia,” even though we both know this is true. And so I have been thinking of my father and what he taught me.

The most overt way my father fought racism in front of me involved no fighting at all. He founded a group called the Korean American Friendship Association of Maine, which helped new Korean immigrants move to Maine and find work, community, and housing, along with offering lessons on how to open bank accounts, pay taxes, file immigration paperwork, and get drivers’ licenses. For both of my parents, community organizing, activism, and mutual aid like this were commitments they shared and enjoyed and passed along to us, their children, and this led to much of my own work as an activist, teacher, and writer. I am not my father, but I am much as he made me.

There’s a difference between fighting racists and fighting racism. Where my father stayed silent, I have learned I have to speak out, which has felt, even while writing this, a little like betraying him. And as a biracial gay Korean American man, I don’t experience the same identifications or misidentifications he did. I am mistaken for white, or at least “not Asian,” as often as I’m mistaken for Chinese, and have felt like a secret agent as people speak in front of me about Asians in ways they would not otherwise. I learned most of my adult coping strategies for street violence from queer activist organizations after college.

Even as I write, “I wonder if he ever felt fear living in America,” it feels like a betrayal, especially as he isn’t around for me to ask him. I think again about how my father always made a point of dressing well, for example, but it always felt like more than that. Men wearing suits as a kind of armor, that isn’t so strange. He had his suits made at J. Press, wore handmade English leather shoes—shoes that fit me. I sometimes wear them for special occasions. Among my favorite objects of his is a monogrammed J. Press canvas briefcase, the name “CHEE” in embossed leather between the straps. After his father gave him an Omega Constellation watch when I was born, he eventually acquired others. For a time I thought he did this aspirationally, but most of his family in Korea is like this: Well-dressed, with a preference for tailoring and handmade clothes. All of my memories of my uncles coming from the airport to visit us involve them arriving in their blazers.

The first time I followed my father’s advice to wear a sports jacket when flying, I received a spontaneous upgrade. I didn’t have frequent flyer miles and the person checking me in was not flirting with me either. There was nothing but the moment of grace, and the feeling that my father, from beyond the grave, was making a point as I sat down in my new, larger, more spacious seat. Because I had never tried out this advice while he was alive.

Like much of my father’s advice, it came from his keen awareness of social contexts, and it worked. His wardrobe came from the pleasure of a dare more than a disguise. You don’t acquire a black and gold silk brocade smoking jacket in suburban Maine because you want to fit in with your white neighbors. Sometimes his clothes were a charm offensive, sometimes just a sass. The jacket advice may well have been an anticipation of racist treatment, of a piece with perfecting his English so he had no accent, and raising us to speak only English. My mother spoke more Korean to us as children than he did—a remnant of her time living in Seoul.

Now that I am old enough to choose to learn Korean, I still feel like a child disobeying him, just as I do when I dress too casually, or acknowledge that I’ve experienced racism. I know I am just making different choices, as you do when you are grown, but also, I am stepping out from behind his program to protect myself. I feel the fears he never spoke about, and instead simply addressed with what now look like tactics. At these moments I miss him as much as I ever do, but especially for how I would tell him, this may have protected you. It won’t protect me.

In my kitchen the other day, as I was making coffee, I fell into the ready stance, with my right foot back, left foot forward, and snapped my right leg up and out in a front snap kick. This is the basic first kick you learn in tae kwon do. And you do it again, and again, and again, until it is muscle memory. You move across the room this way and then turn to begin again.

I wasn’t sure if my form was exactly right, but it felt good. Memories came back of the sweaty smell of the practice room, the other students, the mirrors on the walls, the fluorescent lights. All those years ago, I had thought my father had put me in those classes in order to become him, but as I sent my practice kicks through the air, I remembered how even learning them made me feel safer, protected at least by the knowledge that he loved me. I could not have said this at the time, but after those attacks, I had feared I wasn’t strong enough to be his son.

I still fear that. I suppose it drives me, even now. It is dehumanizing to insist on your humanity, even and perhaps especially now, and so I am not doing that here. Each time I’ve tried to write even this, a rage takes over, and then the only thing I want to do with my hands doesn’t involve writing, and I stop. But I know from learning to fight that hitting someone else means using yourself to do it. My father’s advice, about fighting being the last resort, has given me another lesson: You turn yourself into the weapon when you strike someone else—in the end, another way to erase yourself—and so you do that last. In the meantime, you fight that first fight with yourself, for yourself.

You may never be able to protect what you love, but at least you can try. At least you will be ready.

Alexander Chee is most recently the author of the essay collection How to Write an Autobiographical Novel. A novelist and essayist, he teaches at Dartmouth College and lives in Vermont.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of Mass Nonviolent Action

The use of nonviolence runs throughout history. There have been numerous instances of people courageously and nonviolently refusing cooperation with injustice. However, the fusion of organized mass struggle and nonviolence is relatively new.

It originated largely with Mohandas Gandhi in 1906 at the onset of the South African campaign for Indian rights. Later,the Indian struggle for complete independence from the British Empire included a number of spectacular nonviolent campaigns.

Perhaps the most notable was the year-long Salt campaign in which 100,000 Indians were jailed for deliberately violating the Salt Laws. The refusal to counter the violence of the repressive social system with more violence is a tactic that has also been used by other movements. The militant campaign for women's suffrage in Britain included a variety of nonviolent tactics such as boycotts, noncooperation, limited property destruction, civil disobedience, mass marches and demonstrations, filling the jails, and disruption of public ceremonies.

The Salvadoran people have used nonviolence as one powerful and necessary element of their struggle. Particularly during the 1960s and 70s, Christian based communities, labor unions, campesino organizations, and student groups held occupations and sit-ins atuniversities, government offices, and places of work such as factories and haciendas.

There is rich tradition of nonviolent protest in this country as well, including Harriet Tubman's underground railroad during the civil war and Henry David Thoreau's refusal to pay war taxes.Nonviolent civil disobedience was a critical factor in gaining women the right to vote in theUnited States, as well.

The U.S. labor movement has also used nonviolence with striking effectiveness in a number ofinstances, such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) free speech confrontations, theCongress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) sitdown strikes from 1935-1937 in auto plants, andthe UFW grape and lettuce boycotts.

Using mass nonviolent action, the civil rights movement changed the face of the South. TheCongress of Racial Equality (CORE) initiated modern nonviolent action for civil rights with sit-ins and a freedom ride in the 1940s. The successful Montgomery bus boycott electrified thenation. Then, the early 1960s exploded with nonviolent actions: sit-ins at lunch counters andother facilities, organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC);Freedom Rides to the South organized by CORE; the nonviolent battles against segregation inBirmingham, Alabama, by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); and the1963 March on Washington, which drew 250,000 participants.

Opponents of the Vietnam War employed the use of draft card burnings, draft file destruction, mass demonstrations (such as the 500,000 who turned out in 1969 in Washington, D.C.), sit-ins, blocking induction centers, draft and tax resistance, and the historic 1971 May Day traffic blocking in Washington, D.C. in which 13,000 people were arrested.

Since the mid-70s, we have seen increasing nonviolent activity against the nuclear arms raceand nuclear power industry. Nonviolent civil disobedience actions have taken place at dozensof nuclear weapons research installations, storage areas, missile silos, test sites, militarybases, corporate and government offices and nuclear power plants. In the late 1970s mass civil disobedience actions took place at nuclear power plants from Seabrook, New Hampshireto the Diablo Canyon reactor in California and most states in between in this country and inother countries around the world. In 1982, 1750 people were arrested at the U.N. missions ofthe five major nuclear powers. Mass actions took place at the Livermore Laboratories in California and SAC bases in the Midwest. In the late 80s a series of actions took place at theNevada test site. International disarmament actions changed world opinion about nuclearweapons.

In 1980 women who were concerned with the destruction of the Earth and who were interested in exploring the connections between feminism and nonviolence were coming together. InNovember of 1980 and 1981 the Women's Pentagon Actions, where hundreds of women came together to challenge patriarchy and militarism, took place. A movement grew that found waysto use direct action to put pressure on the military establishment and to show positiveexamples of life-affirming ways to live together. This movement spawned women's peacecamps at military bases around the world from Greenham Common, England to Puget SoundPeace Camp in Washington State, with camps in Japan and Italy among others.

The anti-apartheid movement in the 80s has built upon the powerful and empowering use ofcivil disobedience by the civil rights movement in the 60s. In November of 1984, a campaignbegan that involved daily civil disobedience in front of the South African Embassy. People,including members of Congress, national labor and religious leaders, celebrities, students,community leaders, teachers, and others, risked arrest every weekday for over a year. In theend over 3,100 people were arrested protesting apartheid and U.S. corporate and governmentsupport. At the same time, support actions for this campaign were held in 26 major Cities,resulting in an additional 5,000 arrests.

We also saw civil disobedience being incorporated as a key tactic in the movement againstintervention in Central America. Beginning in 1983, national actions at the White House andState Department as well as local actions began to spread. In November 1984, the Pledge ofResistance was formed. Since then, over 5,000 people have been arrested at military installations, congressional offices, federal buildings, and CIA offices. Many people have alsobroken the law by providing sanctuary for Central American refugees and through the Lenten Witness, major denomination representatives have participated in weekly nonviolent civil disobedience actions at the Capitol.

Student activists have incorporated civil disobedience in both their anti-apartheid and Central America work. Divestment became the campus slogan of the 80s. Students built shantytownsand staged sit-ins at Administrator's offices. Hundreds have been arrested resulting in the divestment of over 130 campuses and the subsequent withdrawal of over $4 billion from theSouth African economy. Central America student activists have carried out campaigns to protest CIA recruitment on campuses. Again, hundreds of students across the country have been arrested in this effort. Nonviolent direct action has been an integral part of the renewed activism in the lesbian andgay community since 1987, when ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) was formed. ACT UP and other groups have organized hundreds of civil disobedience actions across the country, focusing not only on AIDS but on the increasing climate of homophobia and attackson lesbians and gay men. On October 13, 1987, the Supreme Court was the site of the first national lesbian and gay civil disobedience action, where nearly 600 people were arrested protesting the decision in Hardwick vs. Bowers, which upheld sodomy laws. This was the largest mass arrest in D.C. since 1971.

Political Analysis