#Tim Ingold

Text

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

The human genotype, in short, is a fabrication of the modern scientific imagination. This does not mean, of course, that a human being can be anything you please. But it does mean that there is no way of describing what human beings are independently of the manifold historical and environmental circumstances in which they become - in which they grow up and live out their lives.

Ingold, T. (2006) Against Human Nature, p. 273

26 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Through living in it, the landscape becomes a part of us, just as we are part of it.

Tim Ingold, The Temporality of the Landscape

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It is not enough to observe, in a now rather dated anthropological idiom, that hunter gatherers live in 'stateless societies', as though their social lives were somehow lacking or unfinished, waiting to be completed by the evolutionary development of a state apparatus. Rather, the principal of their socialty, as Pierre Clastres has put it, is fundamentally against the state."

- Tim Ingold

16 notes

·

View notes

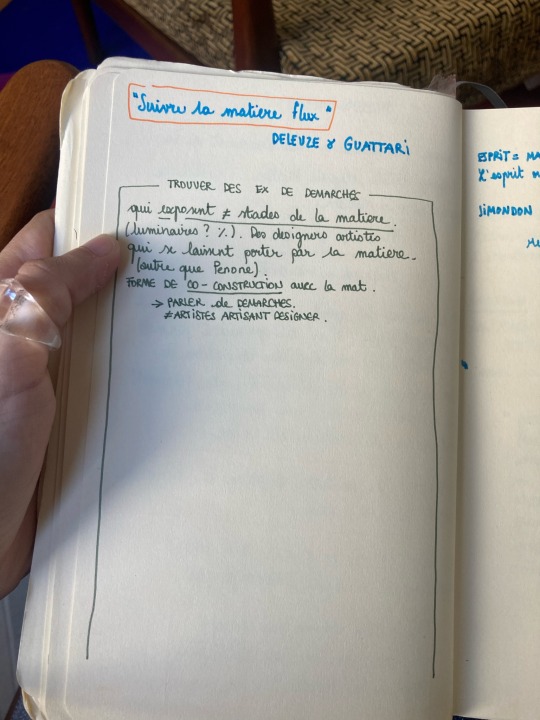

Photo

Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Inquiry is essentially the way of learning : Fragile Architectures of Hapticity and Time)

#Hapticity#Architecture#Collage#Francesca Woodman#Neil Leach#Bricolage#Environments#Peter Lodermeyer#Andrew Todd#Peter Brook#Juhani Pallasmaa#Jennifer A. H. Shields#Anne Cline#Scriptorium#Tim Ingold#MA Interiors#Waverley Inquiry 2013#Russell Moreton

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2022/07/04 English

Today I worked late. In the morning I read Tim Ingold's "Being Alive". I was a bit surprised because this book discusses a topic I am just interested in now. Being alive means not staying still but starting moving. For example, walking, thinking, writing, and talking. Start doing actual action. This book tells us about them (I think so). These actions change this world, and the world reacts to our actions. It causes another dynamic change... It's quite an exciting book.

I attended a discussion about the 'low birthrate and aging society' topic on an 'openchat' on LINE. We should accept immigrants or expect the development of AI... a member said that this problem lets people who have never done helping aged people grow up by helping people actually. Indeed, helping aged people might be tough work... but it made me have a difficult feeling. I can see that working hard and facing difficult things let us grow through my life experience. But it might go to a brutal logic of 'black companies'.

Recently I listen to Joichi Ito's podcast on Spotify. Especially I have a certain concern about the broadcasting with Kenichiro Mogi. Joichi Ito says he also creates a community on Discord. He found a possibility on Discord... which makes me impressed. What does he think? I want to know. With Kenichiro Mogi, he talks about neurodiversity and metaverse, and a brilliant future with technology that has been changing our society exactly. It might be 'a pie in the sky'. But I bet this bright future.

At night I remembered my life. I have lived until now... Exactly I couldn't become a bestseller writer. I would never become that. But I am satisfied with what I am writing. And I have some great readers. Unbelievable... and amazing. I have achieved this state. Also, I have built this skill of speaking English. Of course, I will keep on writing. But now I accept my current state and feel happiness. I lost my hungry spirit... is it OK?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

For Attention: art in the fold of education

Welcome to For Attention. Art in the fold of Education, a two-day doctoral colloquium of the research cluster Art, Pedagogy and Society (Image, LUCA School of Arts, Ghent) on May 2 and 3.

The doctoral colloquium focuses on the role of education in the cluster Art, Pedagogy and Society. The researchers will present how their artistic research corresponds to education. For this occasion, we invite Tim Ingold, professor emeritus of social anthropology at University of Aberdeen, who relates anthropology, art and education. He will attend the colloquium and give a public lecture on LEADING OUT AND LEANING OVER: THE POSTURE OF EDUCATION IN THE WORK OF GENERATIONS. The public lecture takes place on May 2 at 18u.

Please register for the doctoral colloquium and the public lecture via the link before 26 April.

Timetable

May 2

(002) – the lecture of Tim Ingold will take place at C23, the reception at C15

09h30 coffee and tea

09h45 introduction of the doctoral colloquium: Nancy Vansieleghem

10h00 doctoral presentations: Ciel Grommen, Stijn Van Dorpe & Roel Kerkhofs

13h00 lunch by Fiona Hallinan

14h00 doctoral presentations: Fiona Hallinan & Paul Nieboer

16h00 coffee break

16h30 filmscreening school: Nancy Vansieleghem & Julie Lesenne

18h00 public lecture by Tim Ingold

19h30 reception

May 3

(002)

09h30 coffee and tea

10h00 doctoral presentations: Dragana Radanoviç, Mattijs Driesen & Ziya Lemin

13h00 lunch

14h00 general discussion and closure of the doctoral colloquium

Kind regards,

research cluster Art, Pedagogy and Society

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Anthropology, in my definition, is philosophy with the people in.

Tim Ingold, Anthropology: Why it Matters (2018)

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tim Ingold, Architektura jako tkanie, s. 2

0 notes

Text

For it is indeed the case that while affirming human unity under the rubric of a single sub-species, we do so in terms that celebrate the historical triumph of Western civilisation. It is not hard to recognise, in the suite of capacities with which all humans are said to be innately endowed, the central values and aspirations of our own society, and of our own time. Thus we are inclined to project an idealised image of our present selves onto our prehistoric forebears, crediting them with the capacities to do everything we can do and have ever done in the past, such that the whole of history appears as a naturally preordained ascent towards the pinnacle of modernity. The bias is all too apparent in comparisons between ourselves and people of other cultures. Thus where we can do things that they cannot, this is typically attributed to the greater development, in ourselves, of universal human capacities. But where they can do things that we cannot, this is put down to the particularity of their cultural tradition. This kind of reasoning rests on just the kind of double standards that have long served to reinforce the modern West’s sense of its own superiority over ‘the rest’, and its sense of history as the progressive fulfilment of its own, markedly ethnocentric vision of human potentials.

Ingold, T. (2006) Against Human Nature, p. 279

0 notes

Text

What if I "pursued" you with the bloodthirst of a thousand hungry wolves, Tim? What would you do then?

#uni adventures#GET ON WITH IIIIIIT#it's so hard to be a tim ingold enjoyer. he is so irritating to me but he occasionally makes really interesting points#so i have to suffer the irritation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

god it kills me that I spoke with a famous anthropologist whose work I really like during a debate in undergrad and I have ZERO memory of it

#thanks to my classmate Ed for recording the fact I asked Tim Ingold a question#because otherwise I'd be like 'I wish I could meet him' when I have in fact met him#shut up em

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello there! today i came across a claim that sort of baffled me. someone said that they believed the historical norse heathens viewed their own myths literally. i was under the impression that the vast majority of sources we have are christian sources, so it seems pretty hard to back that up. is there any actual basis for this claim? thanks in advance for your time!

Sorry for the delay, I've been real busy lately and haven't been home much. Even after making you wait I'm still going to give a copout answer.

I think the most basic actual answer is that it's doubtful that someone has a strong basis to make that claim, and the same would probably go for someone claiming they didn't take things literally. I think we just don't know, and most likely, it was mixed-up bits of both literal and non-literal belief, and which parts were literal and which parts weren't varied from person to person. We have no reason so suppose that there was any compulsion to believe things in any particular way.

About Christians being the interlocutors of a lot of mythology, this is really a whole separate question. On one hand there's the question of whether they took their myths literally, and on the other is entirely different question about whether or not we can know what those myths were. Source criticism in Norse mythology is a pretty complicated topic but the academic consensus is definitely that there are things we can know for sure about Norse myth, and a lot more that we can make arguments for. For instance the myth of Thor fishing for Miðgarðsormr is attested many times, not only by Snorri but by pagan skálds and in art. Myths of the Pagan North by Christopher Abram is a good work about source criticism in Norse mythology.

Though this raises another point, because the myth of Thor fishing is not always the same. Just like how we have a myth of Thor's hammer being made by dwarves, and a reference to a different myth where it came out of the sea. Most likely, medieval Norse people were encountering contradictory information in different performances of myth all the time. So while that leaves room for at least some literal belief, it couldn't be a rigid, all-encompassing systematic treatment of all myth as literal. We have good reason to believe they changed myths on purpose and that it wasn't just memory errors.

I know you're really asking whether this one person has any grounds for their statement, and I've already answered that I don't think they do. But this is an interesting thought so I'm going to keep poking at it. I'm not sure that I'm really prepared to discuss this properly, but my feeling is that this is somehow the wrong question. I don't know how to explain this with reference to myth, so I'm going to make a digression, and hope that you get the vibe of what I'm getting at by analogy. Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917) described animism in terms of beliefs, "belief in spiritual beings," i.e. a belief that everything (or at least many things) has a soul or spirit. But this is entirely contradicted by later anthropology. Here's an except from Pantheologies by Mary Jane Rubenstein, p. 93:

their animacy is not a matter of belief but rather of relation; to affirm that this tree, that river, or the-bear-looking-at-me is a person is to affirm its capacity to interact with me—and mine with it. As Tim Ingold phrases the matter, “we are dealing here not with a way of believing about the world, but with a condition of living in it.”

In other words, "belief" doesn't even really play into it, whether or not you "believe" in the bear staring you down is nonsensical, and if you can be in relation with a tree then the same goes for that relationality; "believing" in it is totally irrelevant or at least secondary. Myths are of course very different and we can't do a direct comparison here, but I have a feeling that the discussion of literal versus nonliteral would be just as secondary to whatever kind of value the myths had.

One last thing I want to point out is that they obviously had the capacity to interpret things through allegory and metaphor because they did that frequently. This is most obvious in dream interpretations in the sagas. Those dreams usually convey true, prophetic information, but it has to be interpreted by wise people who are skilled at symbolic interpretation. I they ever did this with myths, I'm not aware of any trace they left of that, but we can at least be sure that there was nothing about the medieval Norse mind that confined it to literalism.

For multiple reasons this is not an actual answer but it's basically obligatory to mention that some sagas, especially legendary or chivalric sagas, were referred to in Old Norse as lygisögur, literally 'lie-sagas' (though not pejoratively and probably best translated just as 'fictional sagas'). We know this mostly because Sverrir Sigurðsson was a big fan of lygisögur. But this comes from way too late a date to be useful for your question.

40 notes

·

View notes