#Rough Terrain

Text

Honister Pass, high in the English Lake District, is a challenging drive

#Honister Pass#Cumbria#Lake District#English countryside#winding road#sunset#rough terrain#scenic beauty#UK

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

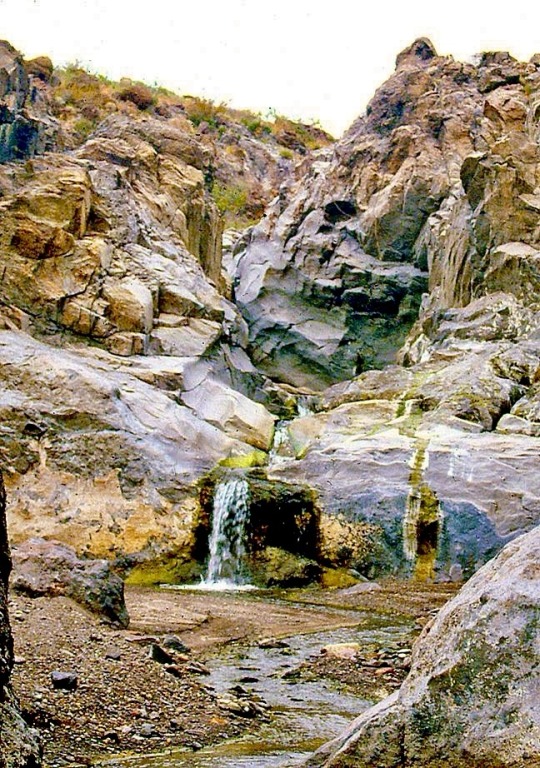

One reason cross country backpacking can be a pain. There’s a lot of obstacles to face in addition to rough terrain. But I love it🧡

#intermittent waterfall#stream#big bend national park#texas trans pecos#chihuahuan desert#backpacking#rough terrain#photo by me

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

You’re cold, like a stone.

How did you get that way?

How did you get that way?

You’re cold, like a stone.

How did you get that way?

Why did you get that way, with me?

The seasons over, the rest is fine

And I grow colder all the time

With never feeling lonely.

And I don’t want to break no more

And I don’t want to know the score

I don’t want to know who’s really happy.

The summer spun us into rough terrain

And across the country, hung my head in shame.

And I don’t know what you do with your days

But I don’t want to collide so I’m drawing

Yellow lines between you and I suggest, we don’t talk about it.

All the lines I drew, while waiting for you.

All the lines I drew, while waiting for you.

The rest is fine and so am I.

I won’t count the clocks again.

Cause if time runs out and I find out

It won’t be my problem them.

Cause you’ve pulled me above and beneath

My goals and it shows and grows and grows and grows.

Thrashing wildly in the core of my soul

It’s getting old.

And now it’s come to this.

Reaching my arms across the empty space next to me.

Watching TV to keep away the bad dreams.

All the lines I drew, while waiting for you.

All the lines I drew, while waiting for you, you.

Oh, you will take one step back, for that, for me.You will take one step back for that for me.

Oh, you will take one step back, for that, for me.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

They clambered all night through "the roughest country I have ever seen in any colony" and found themselves at dawn on the edge of a ravine.

"Killing for Country: A Family History" - David Marr

#book quote#killing for country#david marr#nonfiction#clambering#slow travel#walking#rough terrain#ravine#search party

0 notes

Text

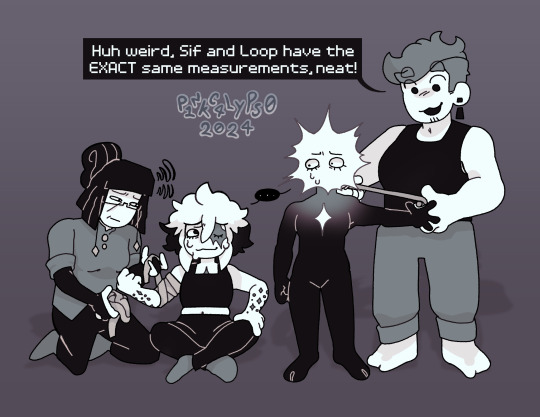

Damn these twinks built completely identical huh, wonder what that’s about

#cw sh#isat#isat fanart#isat siffrin#isat loop#isat spoilers#isat odile#isat isabeau#anyway I don’t think loop wanted to wear clothes but Bonnie mentioned how weird the fact they were ‘naked’#and like idk loop has the most fragile ego and cares so much about the child liking them that this needed to be fixed IMMEDIATELY#they would us the opportunity to request 2 inch heels to be taller than siffren (since sif has like 1 inch heels) and uh it’s been a while#their ass keeps like stumbling on rough terrain and REFUSES to acknowledge it or else they get sensitive#anyway unrelated odile clocks the loop siffren thing so fast but she’s never the one discovering information#other party members will accidentally prompt some information out of them and Odile like snaps her neck in the suitable direction to listen#also odile is helping sif either fully remove or swap out their bandages because god am I definitely normal about the act 5 glass dialogue#I thinks odile helps with sifs injuries :) I think she reminds him to like put stuff on his eye scar cause bitches forgetful

77 notes

·

View notes

Note

Twiddle Niddle in puppet form.. can his legs retract into his body so he could slither like a snake or not? I need to know..

Yes actually! I don't have it on hand but I know there's a doodle of him out there with his legs retracted. He can move pretty fast when slithering.

#in a straight short burst race vs Chickenstab they'd be pretty evenly matched#but if there is any minor obstacle in the way or any elevation change or just#anything.#twiddle would lose lol. he cannot navigate rough terrain at all without his legs#and with his legs hes much slower because he's lumbering his big ol body around with those spindly lil thangs#brambleramble

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

wondering if there's a character who HASN'T done the Do in heels. ????

#absolutely this thought came up bc i saw shadow lineage yakumo bang eiden while holding him up against the rocks#i looked down and saw yakumo was wearing heels!? for the first time??#ah. no wonder he was extra tall this time#i was saying to myself... how? doesn't it hurt your legs? GEEZ yokai heel wearing abilities are something else#i find heels extraordinarily painful. idk if it's the untrained calf muscles or what#so i had to sit in admiration and awe for a bit. wow! look at him go!#then i wondered... have ALL of them accomplished this impossible (for me) feat?#Quincy would never ? probably??#is it because they're impractical? not great for traversing rough terrain?#idk i'll let the quincy experts weigh in#but i started listing off the characters who HAVE done the do flawlessly in those painful shoes#edmond naturally. kuya of course. maid blade.#i haven't unlocked enough rooms to know#does garu wear heels? would he hate them? would he wear them and be completely unbothered bc his calves are the most powerful of all time?#DOES EIDEN EVER WEAR HEELS?#eiden in stilettos when???#i am torn between eiden beautifully strutting around with the confidence of a drag queen#and eiden tripping after a single step on slightly elevated heels#he can do both. depending on his mood#and depending on who's nearby to conveniently catch him if he were to fall oh so dramatically

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gem: Wow, hey Skizz!

Skizz: Heey! What's up, Gem?

Gem: You've done so much.

Skizz: Agh. You- Ah. You're the worse.

Gem: I didn't mean that sarcastically, Skizz!!

Skizz: Yes, you do!

#secret life smp#secret life#traffic series#geminitay#skizzleman#lmaooo#but love island is really looking kinda rough rn#love them but my gosh#the patience to clear an terrain with your only iron tools#sheep live blogs

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's not a real m9 episode if Matt doesn't accidentally confuse Ashley about the mechanics of her character abilities.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I'm bored this afternoon, maybe I'll go climb xiangshan" - the words of an idiot

#I'm not even halfway up stairs and mountains are my worst enemy#be rough terrain like the rest of us#not a trip hazard

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tabled 5

This slow-motion @b-and-w-holiday-gift-exchange gift for @barbarawar , a tale that concerns Myka and Helena’s post-Boone coffee(s) and the fallout therefrom, continues to be quite difficult to get right. It’s still got the shape I envisioned, with Myka sitting at tables and lying and consulting a book to find out her future, but I have to say I didn’t expect the Bering and the Wells to need to hit so very many beats in the course of enacting, or embodying, that shape: witness my optimism in each of part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4 that that part would (might) be penultimate. Then again these two were never going to be able to “get coffee” with any degree of ease, much less find their way back to—or is it simply to, for the first time?—good. Slow and steady may not in the end win the race, but it does finish the race (eventually, though not today); however, please know, @barbarawar , I’ll always be apologizing to you for letting this race, such as it is, continue to run. Anyway, the prior leg ended with Myka and Helena behind the locked door of a hotel room. Myka’s hand had just touched, then trailed away from, Helena’s shoulder.

Tabled 5

Blunders. So the book had said. Satisfactory, so it had also said.

Myka raises her right hand again; it wants to meet Helena’s waist, meet and seek, seek and sway... this hand, so empty as it rises, could be, at long last, full, full, full as it blunders...

But Helena backs away, raising her own right hand, warding Myka off. “Oh no,” she says. “You’re not getting out of anything that easily.”

Rendered purposeless by the refusal, Myka looks down at her reaching (empty) hand, her wanting (empty) body. “Easily?” she asks, because what could that mean? Such blundering could never be easy, no matter how satisfactory.

And yet satisfactory would mean satisfaction. At long last, satisfaction.

Keeping her own hand up, Helena says, “Privacy and nothing more. I said it to you and I meant it. You’ll blame me if in the end it proves untrue, and as for any intemperance of your own? I don’t doubt you’ll indict me for that as well, particularly in the event you’re forced to confess it. Does Pete even know you’re here?”

Myka wants to say yes. As if that lie would make what she wants defensible. As if it would be reasonable of her to say “yes, he trusts me, and isn’t that foolish”: as if by saying that, by getting agreement on that, she could in fact implicate Helena in all of it too. She glances at the table, bolted down, solid. It could give her cover to put that lie in motion.

As if she could do any of that... all right, yes, she could do it to herself. But she should not do it to Helena.

But you can, unison the snake and the lizard and all the other animal manifestations of... well. Animals.

And as she fights to maintain that “should not”: Aren’t you an animal? is their next enticing chorus.

Obviously...

“Obviously not,” Helena says, which brings Myka up short until she walks herself back to Helena having asked about Pete. About what he knows. Myka wishes, for a bloodless, anti-animal moment, that he could know, that she could have told him, told him cold, such that he could understand her as, because he himself also was, then and now and going forward, purely pragmatic.

But Pete is not pragmatic.

“I refuse to serve as your release valve,” Helena goes on, the last two words harsh.

“How could you say that?” Myka demands, trying to make her taking of offense believable, trying to dismiss from her head the evidence that was her raised, reaching hand. Her raised, reaching knowledge of the blunders she would volunteer to make.

“How could you say you have romantic feelings for Pete?” Helena counters. “Never mind what you’re willing to do when his back is turned.”

This is not just about what Myka has said, or even what she’s willing to do. It is not. And apparently now is the time to crash full speed into these walls: “How could you say you had romantic feelings for Nate? For nonexistent Giselle?”

“I did not say that. I invite you to search your prodigious memory, in which you will fail to find me saying that.”

“Really? Semantics? You implied!” This is not the hill to die on; Myka knows that. But she will be dying, and here is a hill. Why not plant her flag?

“Perhaps. But you inferred. And you seem to be doing it again. About my... what shall we call it? Use-value?”

Myka, mortified by intention and error and invalid inference, accuses, “You are the one who brought us to this room.”

“Yes. I do seem to be the one who acts. Leaving aside the recent poorly considered raise of hand.”

Myka doesn’t understand the fuller itch of meaning in Helena’s words. Maybe on purpose. “What are you talking about?” she demands, but she’s pretty sure she doesn’t want to hear the answer. Hearing it will surely require yet more bracing.

“Why did you come to Boone?” Helena asks.

The question confounds. Is she trying to punish Myka by making her put herself back in that place? “Because you called me about the artifact.”

“Yes. I contacted you.”

“I know. Like I said.” Are they negotiating something? Myka can’t reach to it, whatever it is. Maybe that’s on purpose too. She’d rather just raise her hand again, regardless of what tainted meaning Helena might assign it. She wouldn’t say no twice, would she?

Helena’s exhale—exasperated, closing in on angry—suggests she would indeed say no twice, in fact infinitely, based on how obtuse she finds Myka’s response. “Do you not see why I might have had reason to question your... interest?”

“What?” Myka does hate how often she uses, how often she seems to have to use, that word as a mark of utter bafflement.

“It isn’t as if you were looking for me.”

Myka’s entire being sinks. “How do you know?” she asks. A question isn’t a lie, but she feels the further fall of where this must go if the truth comes out, and it’s awful and unpardonable and she will never live it down in front of herself, never mind in front of Helena.

“You didn’t find me,” Helena says, and the backhand of that compliment slaps Myka hard across her pride, because Helena’s right. On every accusatory level, she’s right.

All Myka can muster, in pathetic defense, is, “I didn’t know where to start.”

“So you didn’t. Start.”

Myka doesn’t affirm it. She doesn’t have to.

“Were we not just speaking of who acts,” Helena says. That’s no blunt slap; rather, it’s the lightness of a perfect blade.

“I should have,” Myka says. Her wince is contemptibly inadequate. “Started.”

“You didn’t.”

Myka wishes that had been an angry accusation rather than a dispassionate statement of fact. She begins in response, “Well, you should have...” But she can find no similarly dispassionate retroscription.

“Held myself in limbo?” Helena finishes for her, brutal and true in what she knows Myka wished—what she and Myka both know was unreasonable for Myka to have wished. “I had had enough of limbo. Bronze. Incorporeality. And furthermore, I didn’t betray you.”

Here at this late date, Myka should say it out loud, this unjustifiable position that has irrationally sustained her: “It feels like you did.”

Helena takes a moment, her breathing again exasperated, then says, “Your feelings were not—are not—the primary determinant of my actions. Do you know why?”

“Yes.” Myka wishes she didn’t have to hear the elaboration. But she deserves it.

“Because I did not know your feelings.”

“I said yes,” Myka stubborns. “And it’s not my fault you didn’t know them; that’s Mrs. Frederic’s fault.” Myka would have spoken; she knows it. If Helena hadn’t disappeared, she would have spoken.

But you could have spoken if you’d looked for her and found her! Those animals again. Sing-song. Laughing at all her inabilities.

Helena sniffs. “Her fault perhaps at first. Subsequently, however, your fault.”

The animals and Helena, singing together. Their accord makes Myka dig deeper into her resentment. “I didn’t know yours either.”

“I did keep them close, first from necessity,” Helena says. She’s very serious now, intensity legible in her brow, and Myka feels herself pierced by a familiarly impossible love for that concentration—so lanced that she might fall to her knees, stricken. “But later,” Helena continues, even more severely, as if in rebuke (of the love, of any drama of possible expression), “because I saw quite clearly that my choices in Boone altered your opinion of me. Fundamentally. Not my other sins, grievous as they were, but my choices in Boone. As evidenced by your pulling further and further away... even unto Pete.” She hardens. “I don’t understand your morality. I don’t believe I care to.”

“Then we’re even,” Myka says, trying for similarly hard but faltering, failing, because the soft, vulnerable fact is that she has desperately tried to but doesn’t understand Helena’s morality, particularly (but not solely) how she could have, even for a second, entangled herself with—wanted to be with—that... person, whose daughter could not possibly have offset enough of anything. She doesn’t understand how Helena could ever have taken any comfort in that mediocrity, that fakery, never mind any effect those choices were always going to have had on Myka’s heart. Never mind that.

Never mind it, and Helena can deny that it was a betrayal, but it’s sharp like that, there in Myka’s heart... the condemnation of betrayal is part of her morality, that’s always been a bedrock, and she recognizes a sick mortification at the acute, astute contrast Helena has drawn between her ability to justify Helena’s other sins but not her choices in Boone.

In further contradiction, Myka isn’t condemning herself for betrayal—well, not yet—and of course Helena would call out that flagrant inconsistency. Call it out and condemn it. “You’re changing your opinion of me. Here, now,” Myka accuses, and Helena’s set face is confirmation enough. “We said we knew each other so well,” Myka says, an illogical lament for that tragic, though clearer, time.

Helena shakes her head. “Sentimental claims in an extreme circumstance.”

Nothing but sentimental claims, those words they’d said... and here Myka had thought she already had sufficient fault from that incident to scourge herself forever: Oh, Pete, I’ll refuse to watch you kill Helena, but I’ll let you kill her. As if “I can’t watch this” were a moral stance.

Sins, sins, but omissions not commissions, for what Helena has laid out before her seems now entirely right: Myka doesn’t act. She lets others do the acting. She lets others do the acting; worse, she lets them do the unholy, if thwarted, killing; but most of all she lets them do the saving, which Steve and Pete and above all Helena have done for her. Again and again. Damningly, because whenever she should have thought of ways to save Helena, she’s failed. Perhaps the greatest reason they both must walk away is that the scales between them will never be even.

Myka isn’t crying, because she doesn’t cry; instead, she steels. But in this moment, her tempering goes awry. She feels heat in her throat, threatening to overfill, for she is here, now, realizing that she hasn’t truly believed in this as the end, even though she’s the one who determined so deliberately to bring it about. There have been so many supposed ends—ends-that-were-not—that she’s harbored (yes, tied tight to a dock in her heart) a lifeboat of hope that Helena would save her this time too.

But just as the book declined to save her, Helena is declining as well. Myka can’t see a way out, can’t see any way for them to stop reminding each other of everything that begrimes what once promised blinding beauty, everything that makes the possibility of that beauty harder and harder to discern, even for Myka who can replay all its promise in detail, every brilliant episode, over and over at will... but never fresh. Never without everything else replaying too.

She isn’t crying, but she is grieving. “We can’t fix this,” she says.

“No,” Helena agrees.

It’s a final verdict.

The coffeemaker exhales loudly, inserting itself back into the conversation, and Myka turns to it, numb. Two small filled cups await her, determinedly present. Her hand shakes as she takes one and sets it next to the machine on the bureau; it shakes again as she takes the other and hands to Helena, saying “here,” to which Helena says “thank you”—a domestic little exchange, as if a glimpse of that other reality, the one with the couples therapy. A quiet scene from a pleasant time before they needed the therapy. It’s an achingly calming view.

But the picture fades, going and going, away away, as Helena says, “I don’t know what to do now.” Bleak. Newly so.

Myka stands inarticulate, because she doesn’t know either. Into the gap, she places her best guess: “Drink our coffee?”

So they do that, in this quiet, private space. The lack of distraction brings home to Myka that she has never really attended to how Helena drinks coffee. Their “coffees” have not allowed for that sort of observation, but now she attends, and she readily discerns a pattern: Helena takes a sip, then follows it with a near-gulp; another sip, another gulp. Hesitant, sure; hesitant, sure. Over and over, but then too soon she’s through, through and walking to the table, setting her cup there.

Helena retreats back to the bedside, and Myka understands that she, too, must finish. This is now become a ceremony.

She raises her cup to her mouth and drinks. In a final irony, it’s strong and good.

When her cup is empty, she places it next to Helena’s on the table—this final table that might have supported disastrous, yet satisfactory, blundering.

But even as Myka for one escaping instant lets her imagination soar to the potential transcendence of that blunder, she is visited by a question that crashes it into dirt: could “satisfactory” ever have been enough?

Of course not, say some animals, writhing and reveling in contradiction.

So has Helena in the end saved her one last time?

Sorry, book.

Involuntarily, Myka glances at the clock on the nightstand. It informs her that she can catch her plane if she hurries. Plane, flight, flying...

Oh, I’m flying...

The wisp from that early, beautiful part of their story, when everything was possibility, forces her to try to steel again, this time into cynicism and distance. All it really does is lead her to an incongruous near-regret that she has no gun.

Things should end as they began.

But then they very nearly do, in an even more literal sense: both Myka and Helena move toward the door, then veer away, saying “sorry” as their paths threaten to intersect. Myka takes a step back, yielding.

Helena’s hand is reaching for the door’s handle, to push it down, then to pull, thus breaking the seal that has kept them here.

However: a certainty rises in Myka, a conviction that this part of their story shouldn’t end as it began. They can’t fix everything, can’t fix enough of anything, but maybe Myka can fix this one thing. “Wait,” she says, and she’s gratified to see Helena still her hand’s rise. “I lied to you,” she says.

Helena turns minimally, as if Myka’s request that she stop her motion is an unreasonable burden. “About you and Pete. Your supposed feelings. Yes, I know.”

“Not that lie,” Myka says without thought, then realizes what she’s said, then realizes it doesn’t matter at all that she’s said it. “I’m talking about Nebraska.”

Helena twists her face. “My proving ground.”

“What?” Bafflement again. More mortification.

“Speaking of lies,” Helena clarifies.

It’s not a relief, that acknowledgment—that the “home” talk was fabricated—but it’s something. “Mine too,” Myka begins.

Helena cuts in with, “You were not well.”

So she knows. Knows the lie. Which means she knows the truth. “Is this Claudia again?” Myka asks, defeated.

Helena breathes.

“It isn’t fair that you had a spy the whole time,” Myka says. If only she had had a spy.

Helena says, “No—and I mean no, it isn’t fair, but also no, not ‘the whole time.’ In fact that was how she and I came into contact again: because you didn’t seem well. Egotistically, I thought it might have had to do with me. So I inquired.”

“Which means you know everything.”

“I’d like to think so,” Helena says, with a momentary sparkle of full charm, “but in fact, I don’t. Why did you lie?”

Myka, helpless against the charm, gives the most real answer she can: “I didn’t see a way to be honest with that version of you.”

“Ah,” is all Helena says, and Myka doesn’t know what that means. Implies. Carries. Before she can ask, Helena continues, “And are you well now?”

“I’m sure your spy told you the answer to that.”

“She may have believed she had. But I would like to hear it from you. Honestly.”

“I’m fine,” Myka says. It isn’t honest. She’s about to walk away from Helena for the last time. She is not fine.

“You’re lying. Yet again,” Helena says, with obvious disappointment.

Myka has never wanted to disappoint Helena. Helena has disappointed her, more than once, but for the reverse to be true—it’s pain Myka will suffer in perpetuity.

Helena sighs. “Of course it’s what we do.”

“You and I?” Myka asks, desolate.

Helena curls her lip. “Humans. We’re feral little fabulists who put ends before means.”

If there’s a better formulation of what Myka’s been performing, lately but never when it would do her any real good, she doesn’t know it. “I didn’t look for you,” she says, condemning herself. “And I didn’t burn Boone down to get you free.”

Now Helena smiles fully. Condescendingly. “To what would you have touched your match?”

Myka doesn’t bother answering, because there is no answer. Instead she says, because she should say it aloud, “You’re very good at saving me. I’m terrible at saving you.”

“That’s not true,” Helena says, gentling.

She sounds sincere, and she might mean it, but Myka knows better. “I never hoisted you into the sky.”

“But you did serve as my eventual impetus to leave Boone: essential, once it was allowed. I admit that in the circumstance, faced with your disapproval, I became more obstinate.” Helena ratchets her face down to a half-smile, one that self-deprecates rather than condescends. “Would that you could have hoisted me into the sky.”

“I think the car had already hit you,” Myka says. “I think you stepped in front of the car and begged it to hit you.”

With a bow of head, Helena says, “Apt.”

“Was that because of me? All that I didn’t do?”

“In part? But that can’t be the entire answer.”

“I guess I did the same,” Myka says. She isn’t guessing.

“Because of me?”

Myka wants to put everything on Helena, but she can’t. Well. She can, but she shouldn’t. “In part,” she echoes. Then, “If we had both just said.” It’s a lament.

“We don’t just say.”

“Humans?” Feral little not-sayers, Helena might clarify, which would make their own not-saying at least in some way justified, if not fully excusable, and—

“No,” Helena says. “In this case, you and I.”

Myka’s desolation is complete. “Maybe in another life we would.” She looks at the clock again. Time, time. She knows she should hurry now, but instead she’s fixated on that other life. It’s different, that life. It’s just—different. She wishes she could see her way back and through to how it might have come about, but there are too many branching points, an exploding tree of “why didn’t I” choices; they mingle and blur into a chaos that she has to push down, push down and hide, to prevent that back-tracery from taking her over.

Helena is again moving to the door. Again raising her hand to it. The action—graceful, as always so graceful, a movement flowing as if through water, not air—unfolds in slow motion, stretching time, and is this why Helena always moves with such grace? To prove, over and over, her mastery of time itself?

Tellingly, Myka’s first impulse is to turn away: I can’t watch this. The consequence for Helena here today is not so dire; for Myka, though, it might as well be.

But turning her back on what is most difficult is not—should never have been—part of her morality.

Face it. Face it.

She orients herself toward the door, readying to watch that graceful hand open it. Readying to watch that beloved body recross—uncross?—the threshold. Facing it, just as she should have faced Helena’s imminent actual destruction.

She wishes, hard, that she could have been the one to deliver the reprieve then, wishes she could have parried all of Pete’s and Helena’s arguments about usefulness and nobility, parried them and found a better way, found it and brought it about. That would have been more moral, surely, than a simple turning of her face toward what she never wanted to see...

At that, her brain clicks. More moral? The moral. The lesson hadn’t been—isn’t—“Watch, even when you want to look away.” Because: “Things you don’t want to watch are things that shouldn’t happen.” And so the real moral, of all these stories: “Find a better way and bring it about.”

But this insight, valid as it may be, offers her no vision here of how to find, of how to bring about, that better way.

She tries to think, tries to find, but laughably, in spite of everything, her hand wants to rise again, to catch somewhere, anywhere, on Helena’s body; she feels her wrist, palm, fingers pulling against all the gravity, as if trying to get everyone’s attention, as if that could be the way, as if the argument of a wanting hand could ever be stronger than that of history. As if it could fix any of what had gone wrong.

It couldn’t.

Of course it couldn’t.

But. But. But.

In raising her hand, before, in that inarticulate closed-door wish, she’d been prepared to... what?

Fix nothing. Certainly, she’d been prepared to fix nothing. So: what, then, had her intention been?

To ignore everything that stood between that reaching hand and what she wanted it to achieve.

And if for a blundering moment in a hotel in an airport in Chicago...

What if the book, in its prediction, hadn’t been referring only to what might happen in a blundering moment in a hotel in an airport in Chicago?

What if Myka is meant to blunder—satisfactorily—well beyond this moment in a hotel in an airport in Chicago?

What if the book had told of more than her immediate future? What if it had understood what she had been “about to undertake” as... the rest of her life?

And one final what if—one final move of mind, like the anticipatory shudder of the second hand the instant before it calls a clock’s alarm to life—what if learning to let language slip hasn’t been about dirty work at all? What if it’s the key?

Try it try it try it try it...

“Wait!” Myka yells—it’s no yawp; she’s got purpose now. “We can’t fix this,” she fevers out.

Helena slews her head around, and yes, yes, now she’s caught again; and this, yes, yes, this is what Myka needs. She isn’t surprised, however, when Helena says, “I know. If I hadn’t before, I know it now.”

“No. Listen.” Language, the slip, the work. “‘Fix.’ That’s the word I said.”

“I did listen,” Helena says, and the set stone in her voice rhymes with the adamant of her face. “That is the word you said, and I agreed. And thus we are finished.”

“No!” Myka throws the exclamation up against that tall wall. “We need a different word! Change the vocabulary!”

TBC

#bering and wells#Warehouse 13#fanfic#Tabled#B&W holiday gift exchange#part 5#barbarawar#the various burdens under which these poor beings have labored#are extensive:#choices among which every option yields pain#the twinned obligations of gratitude and graceful acceptance thereof#not to mention years of frustrated wanting#hopes raised and dashed#aspirations soured...#anyway it's rough terrain stretching as far as the eye can see#or the distance any plane might fly

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Somehow (shockingly) organizing my craft supplies and making a to-do list and deleting the open tabs I'm not using have collectively not written this one-shot for me

#unbelievable#headdesk#i am never signing up to dm for con again lol#the merch table was easy as fuck and i just had to show up for it#i have three sets of minis to paint#and i only have a rough outline of this thing#and my session is on saturday#i signed up to do waaaaaaay too many things this month and i did everything i could to allocate the most urgent things first but fuck#why did i decide to write the whole module myself T.T#why did i decide to print terrain for it T.T#why isn't my brain cooperating with me so i can finish this T.T#bleaaaaaaaargh#going to lie face-down on the bed for ten minutes and then try again#dixeram

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you grow up in a bad situation, with parents who fail to support you and hurt you instead, it leaves scars that are sometimes more obvious and sometimes less so.

One of the more insidious scars is this assumption that even when things are going well for you, you're ultimately on your own. That you're always playing catch-up in a rigged game, trying to convince others that you're worth some support and regard. It makes sense; after all, the people who should've taught you that you're worth caring about instead demanded that you defend and justify yourself all the time. Made you into a caretaker instead.

So going forward, that's what you expect. Even after you get away and start to heal, you're always worried. You expect other people to approach you in bad faith, to be constantly looking for your weaknesses and flaws. You're going through life believing that no one's in your corner, no one's rooting for you and wishing you well just because, and you don't even realise you're doing it, because you're so used to the idea of having to constantly work to earn your worth that it's just wallpaper to you. It doesn't even occur to you that people might conspire to your benefit.

Anyway this train of thought is dedicated to the social worker who told me that if I could muster the energy, I "really, really should to go to that big party that you were invited to, because it sounds like you would have fun and that's important!" and gave me a two-second out-of-body experience.

#spoopy's burnout diaries#family trauma#c-ptsd#it's been almost three hours and I'm still laughing about this#sometimes healing is like a slow predictable slog through rough treacherous terrain#and sometimes it's like someone playing circus music at you with a kazoo and then bapping you one the nose with it

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Helloooo! I just saw you wanted to improve anatomy and hands and wanted to offer something.

The noses you draw are a little long on the face and realistic faces you want one eyeball length between the bottom of the nose and the corner of the eye, and one eyeball length from the bottom of the nose to the mouth!

It's just a tip I learned, you totally don't have to do it! /nf /gen I do love your art a lot and I think this could be the small change it needs to really pop.

man i have been debating answering this for days like. i know u mean well and i dont wanna pull the whole 'its my style' thing bc i know how important it is to really understand anatomy

the issue here is that i find i draw like this because of the faces ive been exposed to irl, primarily my own and my family. that suggestion's standard for 'realistic' is not able to apply to my real life face LMAO im absolutely aware and try to make a conscious effort to vary it up bc obv i cant draw every character subconsciously looking like me but. man. please just watch before u peddle very general art tricks as the 'anatomically correct' way because people without perfectly proportioned faces arent anatomically incorrect

#tham talks#/srs#time to go take a nap#respect to all and i dont mean to make anyone feel guilty but. this kinda stuff makes ppl very self conscious#also unsolicited tips are a very rough terrain to navigate#whoops

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The climbing up such rough rocks was very fatiguing; the sides were so indented, that what was gained in one five minutes was often lost in the next.

"Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, 1832-36" - Charles Darwin

#book quote#the voyage of the beagle#charles darwin#nonfiction#sierra ventana#dierra de la ventana#mountain climbing#rough terrain#fatigue

0 notes