#Rio Grande & Colorado Rivers

Text

Lobatos Bridge

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Based on the 12 largest primary rivers by watershed area)

#polls#mississippi#mississippi river#Mackenzie river#st lawrence#Nelson river#yukon#yukon river#columbia#Columbia river#colorado river#rio grande river#Churchill river#fraser river#Sacramento river

0 notes

Text

Environment: Every Drop Counts in America’s Waterways Crisis

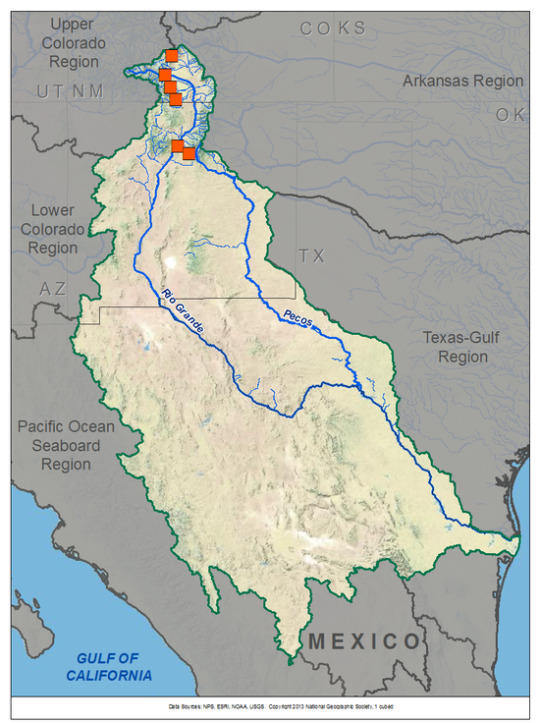

The Rio Grande and Colorado Rivers are two of the most threatened rivers in the U.S. National Geographic Photographer Pete McBride is on a mission to protect these vital rivers and their ecosystems.

— July 25, 2023 | Photographs By Pete McBride | By Kathleen Rellihan

National Geographic Photographer Pete McBride went on assignment to the Rio Grande to capture imagery of the depleted waterway.

Our nation's most vital waterways are drying up at an alarming rate due to global warming, increased human water use, and other man-made impacts. Nowhere is this crisis seen as dramatically than in the American West, with its longest drought in 1,200 years. Two of our nation’s critical lifelines—the Rio Grande and the Colorado River—are shrinking tragically with every passing day.

The Rio Grande is one of the most threatened waterways in the United States.

After spending years traveling the world on assignment, National Geographic Photographer Pete McBride realized that the world’s natural places he spent years documenting were changing drastically due to the disappearance of freshwater. He has spent the last two decades trying to bring awareness to this issue through photography and storytelling. Still, McBride calls for individuals and companies to take action to save our rivers and water.

“I hope to make people more aware of how fragile and precious our freshwater systems are—and why we all need to care for them like beloved family members. When we ask too much of them, they simply disappear.”

— Pete McBride, National Geographic Photographer and Explorer

Now, an effort from Finish Dishwashing is also helping to raise awareness of the crisis affecting freshwater resources everywhere. The Finish brand worked with a Texas sculptor to craft a one-of-a-kind sculpture that depicts the very thing it is honoring. Made from limestone that is native to Texas, the monument draws inspiration from rock formations, waterflow, waterfalls, flora, and fauna unique to many of the endangered bodies of water in the Southwest. Placed at the bottom of a lake in an at-risk area in Texas, the HOPEFUL MONUMENT is the first monument created with the hope that it will never be seen—that is, it will not be revealed unless water levels drop drastically low. While most monuments commemorate the past, this one is meant to spur action for the future—to inspire us to protect our most precious resource: water.

“Our drinking water doesn’t come from the tap, but rather rivers and lakes which supply the vast majority of all our water systems. Without them, then our taps will, and they already are, run dry and/or be polluted,” says McBride.

— Pete McBride, National Geographic Photographer and Water Advocate

McBride knows firsthand about the water crisis in the West, as he has documented it in his award-winning film, Chasing Water, and book, The Colorado River: Flowing Through Conflict. A photographer and Colorado native, McBride's mission is to raise awareness for the Colorado River and all American rivers, or arteries, as he refers to them.

After witnessing a dramatic loss of water in the Colorado River near his home, McBride expanded his photography career to be one that’s focused on environmental advocacy to protect the threatened resources of his home region, the American Southwest.

“I hope that combining beautiful imagery and a human story around a tough subject will help the public become more inspired to understand the issue and become more active,” says McBride, who was named a National Geographic Freshwater Hero for his work documenting rivers worldwide.

The National Geographic Photographer says he’s a “curious citizen who cares about his backyard river” and called to protect the waterway. And he’s now calling everyone else to do their part as well.

A Vital River Under Threat: The Rio Grande

On McBride’s latest assignment in Texas, he’s standing in a dried-up riverbed in the Rio Grande River, a spot locals tragically refer to as the “Rio Sand.” Just an hour south of El Paso, America’s fourth longest river is only ankle-deep in some locations. As it flows further south along the U.S./Mexico border, the river will become a trickle—and in many places—it runs completely dry.

The Rio Grande is dotted by dry stretches throughout Texas.

The Rio Grande supports more than 16 million people in the US and Mexico, including 22 indigenous nations. Alarmingly, this vital river system in North America is vanishing at a dramatic rate. Flowing from the Rocky Mountains and later forming the U.S.-Mexico border, this threatened river and its ecosystems have been impacted by agriculture withdrawals, rising temperatures, and unprecedented drought.

“The Rio Grande, just east of El Paso, is the ‘forgotten reach’—by the time it gets here it's a ghost of its former self. Because of a changing climate, severe drought, and asking too much of this limited resource, it's completely drying out.”

— Pete McBride, National Geographic Photographer and Explorer

The Rio Grande has seen devastating impacts from climate change. New Mexico, like much of the West, has been battling unusually hot and dry weather for the last two decades. The river has also been hit by historic drought, with the lower Rio Grande, the border between Texas and Mexico, dried up for over a hundred miles.

“Fresh water is one of the most important, limited natural resources,” says McBride as he stands in the barren riverbed. “We can live without oil; we can't live without water.”

America’s Most Endangered River—The Mighty Colorado

Seeing firsthand his own home dry-up in the water crisis had a major impact on the National Geographic Photographer: “I grew up on the [Colorado] River, so I always had a fond love for its beauty and wonder. When I followed it to its end and saw it run completely dry, I realized there needed to be more voices speaking on behalf of the river itself.”

The “lifeline of the West,” as the Colorado River is known, supplies drinking water to 40 million people in the U.S., fuels hydropower in eight states, and is a critical resource for 30 tribal nations and agricultural communities, according to the Bureau of Reclamation. It’s also the most at-risk river in the U.S. and is now considered the most endangered river in the world by conservation nonprofit American Rivers. The once mighty Colorado River has been drying out for the last twenty years due to overuse and historic drought.

Due to overallocation and climate change, the Colorado River has not reached the sea for two decades.

“The Colorado River is the frontline of climate change,” says McBride. “This remarkable river system supports over 5 million acres of farmland, where 95 percent of our winter vegetables come from. If you like eating salads, you are eating the Colorado River.”

As the climate crisis worsens, the water levels plummet. Today, the Colorado River runs at only 50% of its traditional flow, while its largest reservoirs in the United States: Lake Powell and Lake Meade, fell to 22% during the fall of 2022.

Everyday Actions to Save Water

The water crisis is a daunting and undeniably complex issue, but that doesn’t mean that people in their daily life can’t help protect our most valuable resource. If we don’t take action now, there won’t be time to save these rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and other bodies of water, warns McBride.

“Become more aware of your waterways. Our voices can make a difference. Rivers need more advocates,” advises the National Geographic Explorer, adding, “You can use less water by reducing meat consumption (meat requires a lot of water to produce), using less water-intensive, non-native thirsty plants in your yard, like bluegrass, and reducing how often you run your water systems for dishes, etc. We need agriculture as we need to eat; we just need to become more efficient and mindful about everything: from what is on our plate to how we clean them and use our taps."

McBride believes these are just some of the everyday actions we, as consumers, can take. Another small change that will make a ripple of impact? Use your dishwasher and stop pre-rinsing. Finish agrees. The brand has a longstanding history of driving impact and inspiring change through its ‘Skip the Rinse’ purpose campaign, which encourages consumers to skip pre-rinsing their dishes before placing them in the dishwasher, ultimately saving up to 20 gallons of water each time. If we all skipped the rinse, we could save up to 150 billion gallons of water every year.

Other water-saving actions include turning off the shower/faucet while lathering or brushing teeth and installing a greywater recycling system.

“Our fresh water is a limited resource,” warns McBride. “If we don’t get involved on some level, we will [see] more of that resource vanish.”

#Environment#Waterways Crisis#Rio Grande & Colorado Rivers#U.S. National Geographic Photographer Pete McBride#Kathleen Rellihan#American West#Hopeful Monument#Texas Native Limestone#Rock Formations | Waterflow | Waterfalls | Flora and Fauna#McBride: National Geographic Freshwater Hero#Rio Sand#El Paso#U.S. 🇺🇸/Mexico 🇲🇽 Border#Indigenous Nations#Rocky Mountains ⛰️#Agriculture 👨🌾#Hydropower#Tribal Nations | Agricultural Communities#Overuse of Waters | Historic Drought#United States 🇺🇸: Lake Powell | Lake Meade#National Geographic Explorer#Shower/Faucet#Greywater Recycling System#Resource Vanish

0 notes

Note

Hey, would you be willing to elaborate on that "disappearance of the Anasazi is bs" thing? I've heard something like that before but don't know much about it and would be interested to learn more. Or just like point me to a paper or yt video or something if you don't want to explain right now? Thanks!

I’m traveling to an archaeology conference right now, so this sounds like a great way to spend my airport time! @aurpiment you were wondering too—

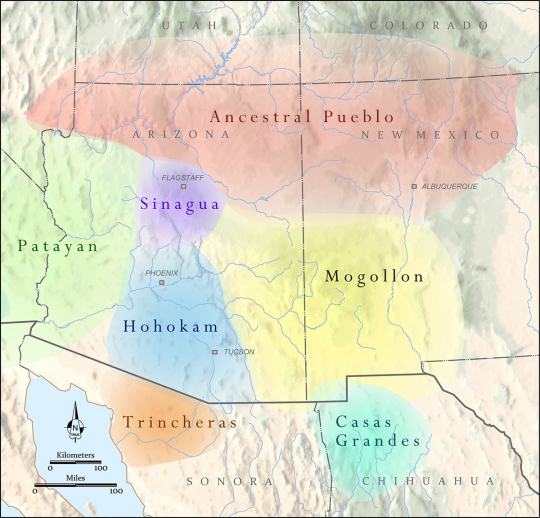

“Anasazi” is an archaeological name given to the ancestral Puebloan cultural group in the US Southwest. It’s a Diné (Navajo) term and Modern Pueblos don’t like it and find it othering, so current archaeological best practices is to call this cultural group Ancestral Puebloans. (This is politically complicated because the Diné and Apache nations and groups still prefer “Anasazi” because through cultural interaction, mixing, and migration they also have ancestry among those people and they object to their ancestry being linguistically excluded… demonyms! Politically fraught always!)

However. The difficulties of explaining how descendant communities want to call this group kind of immediately shows: there are descendant communities. The “Anasazi” are Ancestral Purbloans. They are the ancestors of the modern Pueblos.

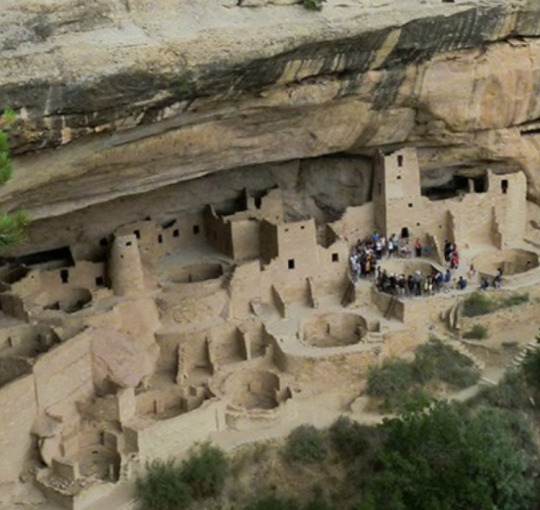

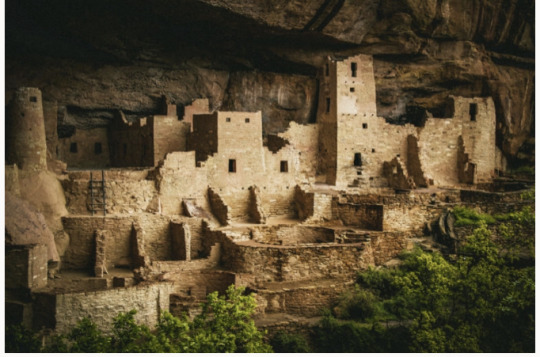

The Ancestral Puebloans as a distinct cultural group defined by similar material culture aspects arose 1200-500 BCE, depending on what you consider core cultural traits, and we generally stop talking about “Ancestral Puebloan” around 1450 CE. These were a group of people who lived in northern Arizona and New Mexico, and southern Colorado and Utah—the “Four Corners” region. There were of course different Ancestral Pueblo groups, political organizations, and cultures over the centuries—Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Kayenta, Tusayan, Ancestral Hopi—but they generally share some traits like religious sodality worship in subterranean circular kivas, residence in square adobe roomblocks around central plazas, maize farming practices, and styles of coil-and-scrape constructed black-on-white and black-on-red pottery.

The most famous Ancestral Pueblo/“Anasazi” sites are the Cliff Palace and associated cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado:

When Europeans/Euro-Americans first found these majestic places, people had not been living in them for centuries. It was a big mystery to them—where did the people who built these cliff cities go? SURELY they were too complex and dramatic to have been built by the Native people who currently lived along the Rio Grande and cited these places as the homes of their ancestors!

So. Like so much else in American history: this mystery is like, 75% racism.

But WHY did the people of Mesa Verde all suddenly leave en masse in the late 1200s, depopulating the whole Mesa Verde region and moving south? That was a mystery. But now—between tree-ring climatological studies, extensive archaeology in this region, and actually listening to Pueblo people’s historical narratives—a lot of it is pretty well-understood. Anything archaeological is inherently, somewhat mysterious, because we have to make our best interpretations of often-scant remaining data, but it’s not some Big Mystery. There was a drought, and people moved south to settle along rivers.

There’s more to it than that—the 21-year drought from 1275-1296 went on unusually long, but it also came at a time when the attempted re-establishment of Chaco cultural organization at the confusingly-and-also-racist-assuption-ly-named Aztec Ruin in northern New Mexico was on the decline anyway, and the political situation of Mesa Verde caused instability and conflict with the extra drought pressures, and archaeologists still strenuously debate whether Athabaskans (ancestors of the Navajo and Apache) moved into the Four Corners region in this time or later, and whether that caused any push-out pressures…

But when I tell people I study Southwest archaeology, I still often hear, “Oh, isn’t it still a big mystery, what happened to the Anasazi? Didn’t they disappear?”

And the answer is. They didn’t disappear. Their descendants simply now live at Hopi, Zuni, Taos, Picuris, Acoma, Cochiti, Isleta, Jemez, Laguna, Nambé, Ohkay Owingeh, Pojoaque, Sandia, San Felipe, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Tamaya/Santa Ana, Kewa/Santo Domingo, Tesuque, Zia, and Ysleta del Sur. And/or married into Navajo and Apache groups. The Anasazi/Ancestral Puebloans didn’t disappear any more than you can say the Ancient Romans disappeared because the Coliseum is a ruin that’s not used anymore. And honestly, for the majority of archaeological mysteries about “disappearance,” this is the answer—the socio-political organization changed to something less obvious in the archaeological record, but the people didn’t disappear, they’re still there.

385 notes

·

View notes

Text

based on suggestions from the previous poll. Before asking about other bodies of water pls check if I've already included them <3

BEFORE YOU START ASKING ABOUT THE OCEANS. Reminder that this poll and the previous one are both offshoots of The Original Poll. Vote for your saltwater coasts there. Gulf of Mexico is included (my beloved)

There may be more polls bc I don't want anyone to feel left out! I'm from the southeast so obviously I have a skewed idea of what's major/popular/well-known. I'll probably keep pulling suggestions from the notes if I do any more polls

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Loire River, France

The Rhine, Germany

Po River, Italy

The Danube, Hungary

Yangtze River, Chongqing, China

Lake Poyan, China - shrunk by 75% due to drought

Rio Grande, Mexico side

Colorado River, USA side

Through this summer (2022), severe drought is being experienced across much of Europe, North and Central America, China, and many other regions.

Some of this of course is making existing problems worse. The Colorado River was in crisis long before this summer (for many years). The Mekong River which emerges in Tibet, and flows through China, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Viet Nam, has been in trouble for years due to a major series of dams in China.

Regional droughts are nothing new however the scale of the current crisis is historic and mostly due to climate change.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

A crash course in some vocabulary

Archaeology, like all sciences, has a lot of specialized jargon we use to talk about pottery. To make sure everyone’s on the same page, here’s a list of some common terms I’ll be using, what they mean, and how to pronounce them.

~ 🏺🏺🏺 ~

Ware: A broader term for a technological/cultural tradition in pottery. Typically, construction method, color, clay type, temper type, and paint type are what defines a “ware.” So Chuska Gray Ware is unslipped, usually unpainted gray clay with crushed black basalt temper. Roosevelt Red Ware is red-slipped clay with sand temper and carbon-based paint. Hohokam Buff Ware is unslipped or cream-slipped buff-colored clay with coarse sand temper, created using a paddle-and-anvil forming method and painted with red paint.

Type: Within a ware, a type is a more narrowly specific decorative style. Roosevelt Red Ware has multiple types within it, such as Salado Red (unpainted red-slipped), Pinto Black-on-red (black paint on the red in a specific radially symmetric interlocked hatched-and-bold pattern), Pinto Polychrome (same decorative style but on a white-slipped interior field), Gila Polychrome (red exterior, white-slipped interior, a usually-broken black band around the rim, black painted designs in a two- or -four-fold symmetry), Tonto Polychrome (bolder and less symmetric black-and-white designs on a red field), Cliff Polychrome, Dinwiddie Polychrome, Nine Mile Polychrome… different stylistic variations on the Roosevelt Red Ware technological/visual core. You can read more about categorizations here.

A note on naming conventions: Pottery in this archaeological tradition tends to have a two-part name: a location where it was first defined and described, and a colorway. Wares tend to be “[Broad location or broad cultural group] [Color] Ware”; types tend to be “[Specific site] [paint color]-on-[clay color].” So within Tusayan White Ware is Flagstaff Black-on-white.

———

Gila: A river in southern Arizona and a bit of New Mexico, and a lizard and a polychrome type named after it. Pronounced hee-la.

Hohokam: An archaeological term for a Native American cultural group that lived in southern Arizona and northern Sonora, defined by traits like red-on-buff pottery, massive canal systems for field irrigation, and platform mounds. It comes from the O'odham-language word huhugham, “ancestors.” They are the ancestors of the modern Tohono O’odham and Akimel O’odham people (it’s a little bit more complicated than that but that’s basically the case.)

Mogollon: An archaeological term for a Native American cultural group from central New Mexico, eastern Arizona, and northern Chihuahua. Most iconic trait is the elaborate range of corrugated and smudged pottery. Named after the Mogollon Rim, the geological formation that marks the edge of the Colorado Plateau and a drastic change in geology and climate in the northern Southwest and the southern Southwest. Along with the Ancestral Pueblo, the Mogollon culture are ancestors of modern southern Rio Grande and Zuni pueblos. Pronounced moh-guh-yon.

Olla: A water jar with a wide body and narrow neck. Pronounced oy-ya.

Polychrome: Pottery that is three or more colors (poly+chrome), most often meaning red, white, and black.

A Tonto Polychrome olla. Southeastern Arizona, 1350-1450.

Pueblo: A collective term for Native people of the Southwest US (particularly in the Rio Grande river watershed, but also Hopi and Zuni) who share cultural traits and history—most immediately notably, a tradition of living in square adobe houses in large villages, which are also each called pueblos. Ancestral Pueblo is the term for the archaeologically-defined cultural group that share these similar traits and are, generally, from the northern half of New Mexico and Arizona, and a southern strip of Colorado and Utah. The Ancestral Puebloans were formerly called “Anasazi” but that has fallen out of favor due to pushback from modern Pueblos. Also, each modern Pueblo prefers to be called a Pueblo rather than a tribe in most cases—so you say the Pueblo of Acoma, the Pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh, Picuris Pueblo, Taos Pueblo, the Pueblo of Zuni, etc.

Temper: Non-clay bits that are added to natural clays to make them easier to work with. When you buy clay from a store now, it’s already mixed and processed and ready to use. When you find clay out in nature, it’s almost never so easy. Typically, you have to mine/harvest clay from riverbanks or cliffsides, and it’s hard and dried; then you have to grind the hard clay up into fine particles, and mix them with water. But natural clays are often puddly and don’t always hold together well, so you add temper, something hard and grainy to make your wet clay stick together more easily and make it good to work with! Temper can be sand, ground-up rock, ground-up shell, or even ground-up bits of other broken pottery. What different people used as temper is one defining feature of a pottery ware and pottery tradition.

Sherd: A broken bit of pottery. NOT shard. When it’s pottery, it’s “sherd.”

Slip: Very runny wet clay. It’s used to help attach clay pieces together, but more pertinently here, plain-colored pots are covered with an even layer of bolder-colored clay slip to get the desired color pot.

Smudging: A decorative style that potters made during the firing stage. They would have open pit-fires for firing their pottery, and cover the desired part of the pot with a layer of charcoal or ash. This creates a carbonized, reducing environment—that is, a lot of carbon, and little oxygen. This creates a smooth, inky black finish on the completed pot.

A Starkweather Smudged bowl. Mogollon, western New Mexico, AD 900-1200.

Vessel: Another word for pot, basically. Means a ceramic container of some sort. Bowls, jars, ladles, pitchers, mugs, etc are all vessels; effigies and statuettes are not.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

D&RGW movie train westbound double-headed locomotives on a freight train pass movie set at hobo's shack "Limited Mail" Warner Brothers

Actors and crew watch a Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad locomotive pass the location shoot of the Warner Brother's film, "Limited Mail," in the Royal Gorge of the Arkansas River, Fremont County, Colorado.

1925

#d&rgw#rio grande#1925#trains#freight train#history#royal gorge#colorado#limited mail#warner bros#movie set

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE BEGINNING OF THE BEGINNING

Who decides where a river starts? When are there enough

sources, strong currents and water wide enough for its name?

In Colorado, the Chama begins in smaller creeks and streams,

flows into New Mexico to form the Rio Grande, splitting Texas

and Mexico (who decided?) and moves deeper south. I think

a few of these thoughts by a creek on a beaming hot day,

as water rips by in rapids propelled, formed in mountains far above.

The water icy even in this summer heat. People grin

some false bravery. They sit in tubes and dip into the tide

and be carried away. I think of drowning. Of who sees water

as fun. Who gets to play in a heatwave. Who trusts

the flow. Migrants floating in the Rio Grande haunt me, so

I think of families tired of waiting, of mercy that never comes,

of taking back Destiny. The rivers must have claimed more

this year. Knows no metering but the rush of its mountain

source’s melt. A toddling child follows her father into water’s

pull. Think of gang’s demands, of where those come from. Trickles

of needs meeting form a flow of migrants. Think of where

it begins. Think of the current of history—long, windy, but

traceable and forceful in its early shapes.

PHUONG T. VUONG

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Rio Grande Del Norte National Monument is a swath of more than 240,000 acres of protected public land in northern New Mexico. Much of the monument's land abuts fifty miles of the Rio Grande. There are several several volcanic cones, including the tallest, Ute Mountain (in Colorado) at 10,093 feet. The monument encompasses the awe-inspiring Rio Grande gorge, an 800-foot deep slash in the Taos plateau that dramatically reveals the depth of the lava flows in the area. The Monuments’ two main rivers are the Rio Grande and the Red River. They were among the first eight rivers Congress designated as National Wild and Scenic Rivers. The headwaters of the Rio Grande are fed by the snow melt of the San Juan mountains in Colorado.

#taos#Rio Grande#Rio Grande River#new mexico#new mexico landscape#travel#weekend getaway#road trip#day trip#optoutside

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

All roads lead to Phoenix. On the gravy train of greenfield investment riding on the back of Inflation Reduction Act legislative incentives in the United States, no county ranks higher than Arizona’s Maricopa. The county leads the nation in foreign direct investment, with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. (TSMC), Intel, LG Energy, and others expanding their footprint in the Grand Canyon State. But Phoenix is neither the next Rome nor the next Detroit. The reasons boil down to workers and water.

First, the labor. America’s skilled worker shortage has been well documented since before the Trump-era immigration slump and pandemic border closures. Especially in the tech industry—the United States’ most productive, high-wage, and globally dominant sector—a huge deficit in homegrown engineering talent and endlessly bungled immigration policies have left Big Tech with no choice but to outsource more jobs abroad.

Arizona dangled its low taxes and sunshine, but TSMC has had to fly in Taiwanese technicians to jump-start production at the 4 nanometer chip plant that was meant to be completed by 2024, but has been delayed until 2025 at the earliest.

The salvage operation calls into question whether the more advanced and miniaturized 3 nanometer plant—scheduled to open in 2026 will stay on course. (With two-thirds of its customer base—including Apple, AMD, Qualcomm, Broadcom, Nvidia, Marvell, Analog Devices, and Intel—in the United States, it’s no wonder TSMC wants to speed things up.)

From electric vehicles to gaming consoles, the forecasted demand for the company’s industry-leading chips is projected to rise long into the future—and its market share is already north of 50 percent. Given the geopolitical risks it faces in Asia, a well-trained U.S. workforce could give it the comfort to establish the United States as a quasi-second headquarters. After all, Morris Chang, the company’s founder, had a long first career with Texas Instruments.

But the next slowdown they may face is Arizona’s dwindling water supply. In just the past year, Scottsdale cut off water to Rio Verde Foothills, an upscale unincorporated suburb on its fringes, due to the region’s ongoing megadrought and its curtailed allocation of Colorado River water. This was followed by Phoenix freezing new construction permits for homes that rely on groundwater.

Forced to find other sources, industry players have stepped up buying water rights from farmers, essentially bribing them to stop growing food that would serve the region’s fast-growing population. Then there are the backroom deals involved in an Israeli company receiving the green light for a $5.5 billion project to desalinate water from Mexico’s Sea of Cortez and pipe it 200 miles uphill through deserts and natural preserves to Phoenix.

Water risk brings political risk for companies. Especially in Europe, governments are carefully weighing the short-term benefits of corporate investment versus the climate stress it exacerbates. They have good reason to be suspicious: Firms such as Microsoft have been notoriously inconsistent in reporting their water consumption, and promises to replenish consumed water haven’t been delivered on. And even if data centers are becoming more efficient, growing demand just means more of them. Some European provinces have blocked data center development, pushing them to locations with high heat risk.

Europe’s regulatory stringency has long been off-putting to foreign investors, which is what makes European officials so weary of Washington’s aggressive Inflation Reduction Act, CHIPS and Science Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

But to fulfill its promise of putting the United States on a path toward sustainable industrial self-sufficiency, these policies need to better align investment with resources, matching companies to geographies that best suit their needs. It would be better to direct capital allocation to climate resilient regions than to throw good money after potentially stranded assets.

If any company ought to know better on all these matters, it’s TSMC. In Taiwan itself, the industry’s huge energy and water consumption are a source of controversy and difficulty. Not only have droughts on the island occasionally slowed production, but the company’s own water consumption rose 70 percent from 2015-19.

Furthermore, Taiwan knows that its real special sauce is precisely the technically skilled workforce that the United States lacks. Yet TSMC has doubled down on Phoenix, a place without a reliable long-term water supply for industry, little in the way of renewable energy, and a construction freeze that will make it challenging to house all the workers it needs to import.

With all the uncertainty over both water and workers, this begs the question of whether the semiconductor company the entire world is courting would have been better off establishing its U.S. beachhead in the upper Midwest or northeast instead? Ohio, upstate New York, and Michigan rank high in greenfield corporate investments, resilience to climate shocks, and are abundant in quality universities and technical institutes.

Amid accelerating climate change and an intensifying war for global talent, how can those devising U.S. industrial policy better select the appropriate locations to steer investment to?

States with higher climate resilience than Arizona are starting to flex for greater investment. According to recent data, Illinois has climbed to second place nationally for corporate expansion and relocation projects. The greater Chicago area and state as a whole are touting their tax benefits, underpriced real estate, growth potential, and grants to prepare businesses to cope with climate change.

Other parts of the Great Lakes region, such as Michigan and Ohio, are also regaining confidence in their industrial revival, pitching heavily for both domestic and foreign commercial investment while emphasizing their affordability and climate adaptation plans.

Just over the border, Canada has been wildly successful in poaching foreign skilled workers unable to secure or maintain green card status in the United States while also investing heavily in economic diversification—all with the benefit of nearly unlimited natural resources and energy supplies. While Canada hasn’t yet rolled out Inflation Reduction Act-style tax breaks to lure investors, it abounds in critical minerals for EV batteries (nickel, cobalt, lithium and rare earths such as neodymium, praseodymium, and niobium) as well as hydropower.

The more that climate change warps the United States, the more grateful it should be that its most natural and staunch ally occupies the most climate resilient real estate on the North American continent, even taking into account the raging wildfires of this summer. But rather than covet Canada the way China does Russia—as a vast and depopulated resource bounty—the United States and Canada should cooperate far more proactively on a continental scale industrial policy that would bring about true self-sufficiency from the Arctic to the Caribbean.

This is where geopolitical interests, economic competition, and climate adaptation converge. As Canada’s population surges by up to 1 million new permanent migrants annually, a more unified North American system would be more self-sufficient in crucial commodities and industries, less vulnerable to supply chain disruptions abroad, and avoid unnecessary carbon emissions from excessive inter-continental trade. Thirty years after the NAFTA agreement, it seems more sensible than ever to graduate toward a more formal, autarkic North American Union.

One can easily imagine Greenland joining one day—the country already enjoys autonomy from its colonizer (Denmark) and is now pushing for complete independence, driven partly by the desire to control more of the riches that climate change has revealed it to possess.

Meanwhile, in Taipei, there are far more complex geopolitical consequences to consider. TSMC has long been considered Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” a leader of industry so important that a conflict that took it offline would be a major own-goal for China. But it is precisely the combination of the China threat, environmental stress, and pandemic-era supply chain disruptions that convinced TSMC’s customers that its home nation represents too large a concentration risk.

Now TSMC and its rivals are expanding production from Japan to the United States, Europe, and India. This globally diversified set of chip manufacturers is easier for China to exploit as countries more susceptible to Chinese pressure become less rigid in compliance with U.S.-led export controls over advanced technologies.

At the same time, if the United States no longer depends on Taiwan itself for the majority of its semiconductor supply in just five to seven years, will it be as willing to defend Taiwan militarily? This, not Ukraine, is what Beijing is watching for as it pursues its own “Made in China” quest for self-sufficiency.

Industrial policy is back in vogue as a national security and economic strategy. But to get it right requires aligning investment into industry and infrastructure with the geographies of resources and resilience. The countries that build climate adaptation into their strategies will be the ones that build back better.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, I don't know who to ask this...

It occurred to me that bison used to be *Very* populous, and that they migrated, and crossed rivers to do so.

So, extrapolating from Africa, we have a vast water born bounty, floating downstream. What took advantage of this?

I am guessing wolves, bears, fish, birds.... In Africa there are crocodiles. Who sometimes get very little food the rest of the year.

Did alligators come north?

Are alligator Snapping Turtles big enough to feast for a while year(, or just pack on weight while the food lasted.)

Can that be one reason they get so darn big?

Has anyone else thought of this?

Hi there! This is a really interesting question, although the answer might not be what you think.

You're correct that, in Africa, there are crocodiles that regularly take advantage of larger prey like antelope and zebra as they attempt to cross rivers. However, all these rivers are major bodies of water, like the Nile, the Okavango Delta, or the Congo river. They're big, so they provide enough room for crocodiles to compete for food and mates, and attract a lot of prey via migration and the necessity of drinking. These rivers are also ideal temperatures for crocodiles, who are cold-blooded and need to bask in the sun to maintain their body temperatures.

In North America, there aren't many rivers that meet those qualifications. There are some alligators in the southeast end of the Rio Grande, where it runs into the Gulf of Mexico, but father north both it and the Colorado River are too cold for big reptiles. Other rivers that cross bison country are both too cold and too small. Alligator snapping turtles do have a mean bite, but they aren't nearly big enough to bring down a bison-- some of the largest have weighed over 100kg (close to 300lbs) but the average adult bison weighs at least 300kg (something like 700 lbs). The range of bison and alligator snapping turtles also don't overlap much; snapping turtles live generally east of the Mississippi River, while bison live to the west of it. So unfortunately there weren't really any big aquatic predators of bison.

However, wolves, cougars, and bears will all hunt bison, especially the old, young, or sick. Another important predator for bison were people: in fact, some historians believe now that the 'vast seas of bison herds' were actually a result of the decline of Native American populations due to disease and conflict with colonizers, which then allowed the bison population to spread unchecked.

#american bison#Artiodactyla#Bovidae#bovines#even toed ungulates#ungulates#mammals#alligator snapping turtle#Testudines#Chelydridae#snapping turtles#turtles#reptiles#american alligator#nile crocodile#Crocodilia#Crocodylidae#Alligatoridae#crocodiles#alligators#crocodilians#north america#africa#answered#asks#jack speaks

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s a beautiful August day, and Saige Copeland couldn’t bear to stay indoors! She brought her easel and canvas outside, with her dog Sam, to put the finishing touches on her latest work. The painting features the beautiful, rugged Sandia Mountains that border the city of Albuquerque to the east.

While she paints, Saige is going to share some facts about her hometown that you probably didn’t know!

Saige lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The population is around 500,000. That makes it the most populous city in the state, but it is not the state’s capitol. That honor goes to Santa Fe, about 60 miles northeast.

The state of New Mexico was added to the union in 1912, making it the 47th of 50 states. Prior to statehood, it had been a territory since 1848, when the US forcibly seized it from Mexico as a means to repay Mexico’s debt. It was a colony of Mexico from 1821 to 1848. Before that, it was occupied by Spain from 1598 to 1821. No other state in the US has seen three different flags flying over it.

Albuquerque was founded in 1706, which is about 100 years after Santa Fe was founded. But indigenous people have lived (and still live) in the area for centuries prior, living in pueblos, or small densely populated settlements.

Bordering the north of the city is Sandia Pueblo, and to the south is Isleta Pueblo. Both places have been continually inhabited for close to 1000 years. Pueblos are similar in concept to reservations, but have a few differences. There are 19 pueblos in total in New Mexico.

The Rio Grande (Spanish for “great river”) flows right through the middle of the city. It’s very wide and shallow in this area. It starts in the Rocky Mountains far to the north in the state of Colorado, and flows southeast into Texas, where it forms the border between the United States and Mexico until it ends at the Atlantic Ocean.

Albuquerque sits at an elevation of around 5,300 feet, a little over a mile high, or 1600 meters. That’s actually a bit higher than Denver, Colorado, which is known as the “mile high city”!

The weather conditions are near perfect for most of the year, with the city enjoying 310 days of sunshine every year! Spring and autumn are beautiful. Early summer does have a few very hot days, but those cool down closer to July and August. Those two months are the monsoon season, when it rains nearly every day, but rarely last longer than a couple of hours. Winters are mild, with only one or two heavy snowfalls a year and a few smaller snowfalls.

The Sandia Mountains, which Saige is painting, rise to a height of 10,678 feet or 3,254 meters. That might sound very high, but they are by no means the highest mountains in the state! There are many higher peaks farther north. Sandia is the Spanish word for “watermelon”, because they turn lovely shades of watermelon red and pink when they catch the light of sunset. At the top, you can stand at the scenic lookout point, do some more hiking through the beautiful forest, stop by the cafe and gift shop, and then ride the ski gondola all the way down to the bottom.

That’s right: there’s a ski resort at the top of the mountain! It’s actually on the east side of the mountain, facing away from the city, since that gets colder temperatures and more snow. If you don’t want to climb on foot or take the ski gondola, you can just drive to the top. The Sandia Crest Scenic Byway starts at the bottom on the east side, and goes up 3000 feet/ 914 meters to the top, passing through several different ecosystems. As you go up, the trees change from pine to spruce and aspen, and you can still see snow on the ground as early as October or as late as May.

Both Saige and I love spending time in the Sandia Mountains. Where she is set up painting is part of Cibola National Forest, and it’s set right up against the mountainside. It doesn’t even feel like you’re so close to the city! There are miles and miles of hiking trails and plenty of scenic viewpoints.

All finished!

Thanks, Saige, for sharing! Your painting looks beautiful!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

MEXICO CITY, July 14 (Reuters) - A floating barrier of orange buoys put in the Rio Grande by the Texan government to hinder migrants crossing into the U.S. violates a water treaty and may encroach on Mexican territory, incoming Mexican Foreign Minister Alicia Barcena said on Friday.

"We have sent a diplomatic letter (to the U.S.) on 26 June because in reality what it is violating is the water treaty of 1944," Barcena told reporters in Mexico City, referring to the Mexican Water Treaty between the U.S. and Mexico that covers the use of water from the Colorado, Tijuana and Rio Grande rivers.

"We are sending a mission, a territorial inspection," Barcena added, "to see where the buoys are located... to carry out this topographical survey to verify that they do not cross into Mexican territory."

The U.S. State Department and the office of Texas Governor Greg Abbott did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Barcena was named foreign minister last month but is still awaiting formal confirmation by Mexico's Senate.

On Friday, the Texan government said in a statement that it had this week begun installing the "new floating marine barriers along the Rio Grande River in Eagle Pass."

It said the buoys will "help deter illegal immigrants attempting to make the dangerous river crossing into Texas."

Many migrants have drowned trying to cross the river in recent years but some experts fear the buoys may only increase the risk of crossing.

Earlier this month, four migrants drowned in the Rio Grande. Last September nine migrants died and 37 were rescued as they tried to cross the rain-swollen river near Eagle Pass.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

1996-06-20 1515 AMTK 511 on AOE, Chacra, CO by jimkleeman

Via Flickr:

Two Pepsi Cans (P32-8 511 and 509) lead the westbound American Orient Express over the Colorado River near Chacra, CO on the former Rio Grande.

#aoex#american orient express#amtk#amtrak#d&rgw#rio grande#1996#trains#passenger train#history#chacra#colorado

15 notes

·

View notes