#Maedhros in a dress

Text

October 29th

Costumes

Oh, Russingon - my curse, my downfall, my fatal weakness - there you are.

Too many people deserve a mention and I quail at the idea of disturbing those revered authors in their peace with my silly little ficlet, so - ever the coward - I will abstain.

Nonetheless, it would be dishonest not to mention last-capy-hupping and arofili for being such lovely inspirations and supporters. Never forgotten also the amazing people thanked in my TRSB fics who have helped me figure things out.

Here they are, the pairing that changed everything, pulled me through TRSB, and made me go on writing for the Silm...the couple that made me go back on all my principles...

Here is the testament to "Bittersweet and strange, finding you can change, learning you were wrong..."

There's been a lot of discourse running through my head lately and I'm weirdly reticent to post this one...I guess I'm just afraid of what might happen...here goes nothing...

Words: 738

Warnings: LGBTQ+ characters, half-cousin incest, cross-dressing, trans!Fingon...the whole shablam 🙈

“I am so not going to wear this!” Maedhros grunted and glared at Fingon who was holding up a lumpy, oddly spotted, limp piece of fabric that looked suspiciously like a tent with sloppy a giraffe print plastered all over it.

“I was afraid you’d say that,” Fingon purred, stepping closer and throwing aside his decoy costume to push his hands into the luscious mane of his lover’s hair; he loved every single strand of it and it was its glory that had inspired his real concept for this Halloween. “How brave are you, my handsome one?”

Maedhros gave a deep sigh; he knew that tone only too well and – after many long discussions – they had finally decided to wear matching costumes. It was not an official admission of their relationship status per se, but it was already a big step away from stealing kisses and pretending not to know each other too intimately when other people were around.

“I am not afraid of the costume,” Maedhros griped, “I just don’t want to look like a fool.”

Vulnerability and vanity painted his face a flaming crimson, but Fingon only repeated his question in a soft, tender, encouraging voice while he peppered small kisses along the ridge of Maedhros’ jaw.

“As long as you’re with me, valiant, reckless Finno, I can be very brave indeed,” he replied in a moment of foolish, cocky courage. “Bring it on!”

Reaching under his bed, Fingon produced a long tube, shimmering in dazzling reddish colours in the dimmed light of his bedside lamp and held it up to Maedhros’ body with a quizzical look on his face.

“Finno,” Maedhros growled warningly; there was – in his opinion – no way he’d fit into the criminally narrow garment that would, if he was to succeed against all odds, hug every non-existent curve of his bony body.

The reference picture on Fingon’s phone showed the drawing of a busty redhead with a smouldering gaze and a sensual mouth.

“Jessica Rabbit,” Fingon whispered, “the second-hottest ginger in the world.”

“Second to whom?” Maedhros grinned, taking the dress from him and rubbing the thin, flexible material between his thumb and forefinger pensively; his blood roared with an elating mix of excitement and dread.

“You, of course,” Fingon laughed and nodded at his wardrobe, “I’ll go as her sometimes-ex and often-husband, Roger Rabbit.” There was such raw, bare-faced, disarming hope in his face that Maedhros felt his neck melt; he nodded even while every fibre of his being bristled at the idea of letting everyone see just how pale and angular he was.

If it would make Fingon – who was ready and willing to wear a poofy rabbit tail and formless dungarees – smile, Maedhros would not be a spoilsport.

“Okay,” he breathed, leaning forward and letting Fingon impress that beatific smile onto his own lips so he could keep it forever in his heart and memory.

“I’ve asked my sister for help,” Fingon exclaimed excitedly. “I will do your make-up and straighten your hair.”

He had been so sure, Maedhros thought, deeply moved by this discovery; Fingon had been convinced that he’d manage to talk the stuck-up, often morose and sometimes craven man he called his own into wearing a skin-tight dress. The sudden onslaught of pure, infectious joy shooting like fireworks through his whole body him laugh aloud; yes, they would have fun and confuse many a person.

“Káno will be livid,” Maedhros grinned, “when I outshine him on the dancefloor.”

Inspired and overjoyed by Maedhros’ compliance – in truth, Fingon had fretted quite a bit about this – the would-be-rabbit resolved that he wouldn’t chicken out either; for the first time ever, he’d let others see his body, the truth written in pale scars – barely visible now – running along the underside of his pectorals, and the ridiculously slender wrists he felt so self-conscious about still.

“You’ll be the prettiest,” he promised Maedhros who seemed to grow ever more thrilled about the prospect of earning his mother-name by being undeniably beautiful. “And I’ll be the proudest critter at that rotten ball. Your brother will swallow his tongue out of sheer envy!”

It was a ludicrous way to come out, Maedhros thought hazily, a ridiculous proclamation of resilience, a preposterous declaration of love, but – the more he thought about it, the surer he grew – it would reflect and represent them, and all that they were underneath the polite and polished surface, perfectly.

@fellowshipofthefics here's one that's near and dear to my heart.

Lots of love from me...Please refrain from being needlessly cruel...I am just one person trying to put out some love; I've never meant to hurt/offend/anger anyone!

-> Masterlist

#fanfiction#writing#IDNMT writes#fotfics October challenge#fotfics fictober#ficlet run#1 scene per day#a different pairing every day#the silm#the silmarillion#Russingon#Maedhros#Fingon#Maedhros x fingon#costumes#trans!Fingon#Maedhros in a dress#love#and friendship#and a lot of nonsense

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

quick 15min doodle, bc I'm working on (currently only hypothetically tho :c) Something based on that post about "would mae survive castle dracula"

inspired by this snippet of a conversation w @nelyoslegalteam

#silm#silmarillion#maedhros#dracula#crossover#okay i need to somehow draw up a crossover w the pretty deadly guys dressed as rock opera c&c interacting w mae in draculas castle#purely for the tagging chaos#background on this: mae needs to Discuss Things w dracula (he wants to use dracs roads as a shortcut for the army)#he rode there on his giant valian horse that i have named Rocco#bc i hc him as a gift from celegorm and we all know how celegorm names pets#originally he was riding alongside the 'driver' bc drac didn't know what to do w Rocco since the horse cannot go in the carriage#but then drac started going in circles and mae got fed up and went straight to the castle (which. he could see the whole time. because Elf)#(drac panicked and had to run top speed to the castle to make it there before the giant magic horse did)#and then when they got there drac obviously did not have stablehands or a doorman or anyone to take care of Rocco#so mae just. brought his giant 10 foot tall horse in through the front door#and drac is like 'I DID NOT BUDGET FOR A HORSE'

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weeping honestly I understand this less than you

#But fingon would slay a leg split#It’s been a very long day okay#Sometimes I need food and water#sometimes I need Them in dresses#Russingon#Fingon#maedhros#maedhros x fingon#findekano#maitimo#maitimo nelyafinwe#nelyo#nelyafinwe#russandol#silm art#lol if I can call this art#who am I kidding it’s ingenious#the silm#the silmarillion#silmarillion#silm fandom#the silm fandom

9 notes

·

View notes

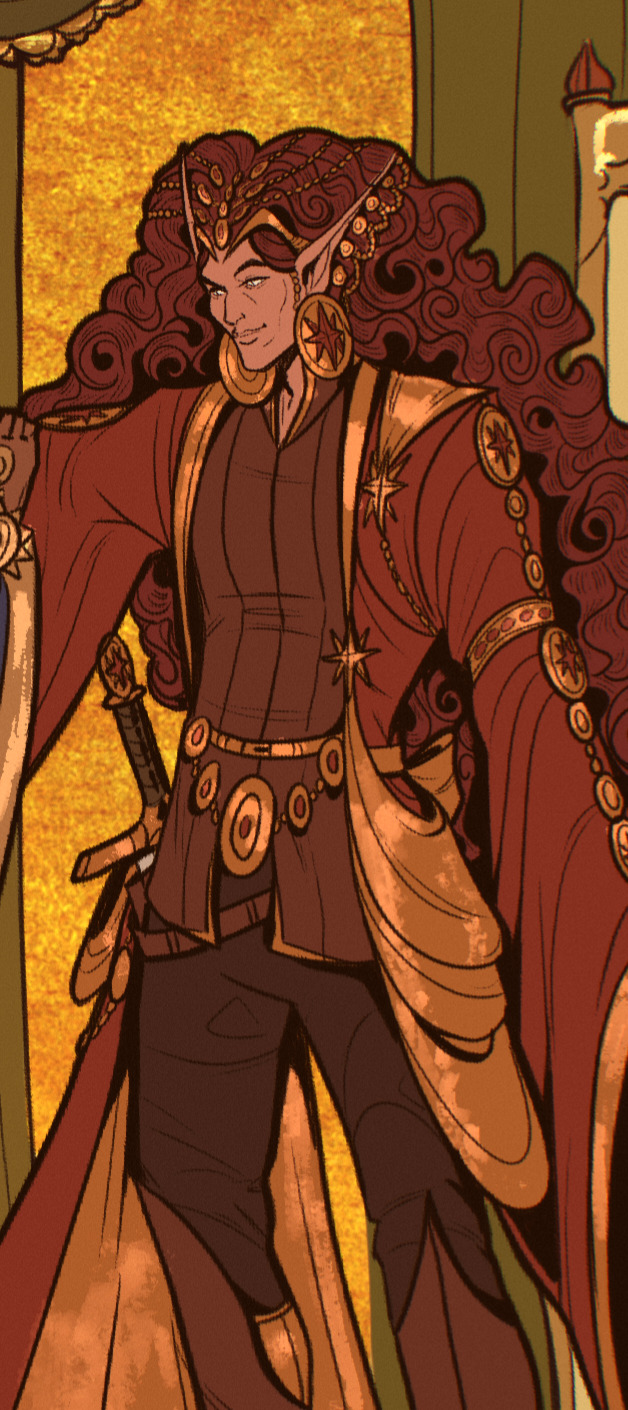

Photo

redrew this maedhros from 2012

“Maedhros did deeds of surpassing valour, and the Orcs fled before his face; for since his torment upon Thangorodrim his spirit burned like a white fire within, and he was as one that returns from the dead.” quotes which rewired my brain chemistry etc etc

#maedhros#silmarillion#the silmarillion#tolkien#i was going to put Blood on his Sword but forgot and ive already posted this on like two of my social media platforms.#so i cant be assed to change it now. use your imagination#antony makes art#some things change (immense overall improvement and altered character design)#some things stay the same (refusal to fully render draw backgrounds or armor)#(and also maedhros being impractically dressed for battle for the sake of looking sexy as hell and super cool)#ok no more tag rambling#maedhros................................................... [woozy emoji]

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

You brought it upon yourself: best and worst dressed Finweans. You can rank them all or just tell me the very best and the very worst or anything in between, I just need to know more forbidden fashion facts from the mind that's brought us basketball jersey surcoat Fingon --tolkien-feels

Oh no! 😂 I feel very ill-equipped for this ask, and I do need to point out that this art is the reason I always think of modern!Fingon in basketball jersies and deeply janky diy tank tops. He's just the kind of guy who should wear his armscyes down to his hips.

Now, the thing is, 'best dressed' depends on social context! For example, what works well in Tirion may not work in Alqualonde or Beleriand at large. What works in Noldoran Court would be cumbersome and awkward meeting with Iathrim ambassadors. So:

Fingolfin, Maedhros, Turgon, and probably Caranthir qnd Curufin are always well-dressed. But in slightly staid, respectably Noldoran ways. Maedhros and Caranthir and Curufin tend to be flashier, but they all go for conventional fashion focused on showing off the craftsmanship of their outfits.

Celegorm, Aredhel, Fingon, Amrod, Amras, and I think Aegnor tend towards jock chic, with varying degrees of perpetual dishevelment. They all can clean up well enough, and they all do typical Noldor flashiest well enough. But if nobody reminds them about an event, they'll tend to be at least a little under-dressed. Fingon falls into that trap less, if only because a hairdo full of gold compensates for a certain about of sartorial laziness among the Noldor. And this general approach becomes much more acceptable in Beleriand than in was in Tirion.

Finarfin, Orodreth and Galadriel all tend towards classy simplicity. It's a more Teleran/Sindaran approach, though, so while they always look good (and often more comfortable than their heavily bejeweled family members) they loose points in the gossip columns. This group does better at mixed culture events generally, but gets more snippy remarks from the Noldor in Beleriand I bet.

if you want fashion that is avante garde, cutting edge, and sometimes Does Not Work, you have to go to Finrod and soooometimes Feanor. Feanor drops out of this as political tensions rise and he has more kids to dress, but he's always quietly disappointed that his sons aren't more daring in their fashion.

So: at any given Finwion party, the worst dressed could be from The Jocks (underdressed and slightly messy), the ones who Snub Noldoran Fashion (solely on grounds of not playing to social expectations) or Finrod or Feanor or Maglor (a wild idea that didn't play out right; a wardrobe malfunction is a clear possibility).

#Tolkien#Not that wild experimental dress isn't de rigure for the noldor to some extent#I could see a *failure* to experiment with flashy dressing also being a failing in a noldor politician#But Maedhros would not wear clothes with experimental closures to a party. Finrod and Feanor both would#Feanor is sad his eldest wouldn't risk a wardrobe malfunction on the red carpet. Finwe is relieved (until finrod starts dressing himself)#I hope I haven't forgotten anyone#...I forgot maglor#I feel like maglor is a chameleon though#He'll do any and all of these depending on the occasion and who's in his party#Is it ever worth it for him to compete with Finrod? Probably

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elvish art genre that definitely exists in Middle-Earth: the captivity of Elrond and Elros (mostly just Elrond, especially after Elros dies)

The paintings– done mostly, but not always, by Sindarin and anti-Feanorian Noldor artists– are usually studies in contrast– Elrond as the bright, innocent child dressed in white; often portrayed as a small, frightened elfling, frozen at the moment he was taken from Sirion. Sometimes he is shown bravely resisting the cruelty of the Feanorians, other times he mourns for Sirion, or bows and prays to the gods for deliverance. Sometimes, he's given wings, both to stress his connection with Luthien and Elwing and to make him look more angelic and pure in comparison to the fallen Feanorians.

Maedhros and Maglor are the dark monsters the oath made them, with teeth, and claws, and harsh armor. Some of the more daring artists just portray Maedhros as an actual orc. While few of the paintings actually show the Feanorians' crimes, they're often portrayed with blood on their hands or swords, or simply surrounded by fire and destruction. They often demand, or threaten in the pictures, towering over Elrond and casting long shadows on him.

There's a few different sub-genres of these paintings. The ones that explicitly compare Elrond's situation to Luthien's kidnapping by Celegorm. The ones that feature a grateful Elrond being saved from the horrible Feanorians by whoever the artist is looking to valorize– Gil-Galad, Galadriel, Oropher, Eonwe, etc. The ones that show Elrond, locked in a dark cell, staring longingly out at Gil-Estel rising in the night sky. Some of the strangest are the ones that draw connections between the Silmarils being kept in Morgoth's crown and the twins– often with Maedhros playing the role of Morgoth.

Elrond hates almost all of these paintings. He feels like they take away his ability to define his past the way he wants to– to tell his own story. Most of them are grossly inaccurate, but most people don't know that, and dredging up all those really painful memories to try and correct people's assumption is hard. Sometimes, even when he does, people won't listen. Some of the paintings also seem... weirdly gleeful about the idea that Elrond suffered because of the Feanorians? Like they're trying to martyr him even though he's alive, and doesn't want to be martyred. It all makes him really, really uncomfortable.

There is one exception. It's not a very traditional example of captivity paintings. Elrond is at the center of the frame, shown not as a small child but as a young adult. Maglor and Maedhros are mostly unseen in the background, each with a bloody hand on one of Elrond's shoulders. Unlike the other paintings, instead of looking off into the distance or staring demurely at the ground, Elrond is looking straight out at the viewer His expression is hard to place. Anger? Acceptance? Defiance? Pity? Accusation? It's a very odd picture that unsettles almost everyone that look at it.

Elrond insists on hanging it in Rivendell.

#silmarillion#silm headcanons#silm meta#elrond#elrond peredhel#eldritch peredhel#maglor#maedhros#i think a lot about how the elves would've turned their history into art#and i can very easily see Elrond becoming a muse for a lot of different types of paintings#including ones he'd really rather not be included in#it's hard because he knows that many of the Sindar have every right to see Maedhros and Maglor as monsters#but it's still really difficult for him to see them portrayed that way when he cared about them both deeply#the Maedhros and Morgoth comparisons are especially uncomfortable for Elrond#and he knows they would've been really upsetting for Maedhros#kidnap fam#kidnap dads

327 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm legit so proud of this. and also utterly in love with the idea of mae helping Fingon put on his jewelery. You guys feel? The tender intimacy of helping someone dress? The added layer of these two being noldo, and the cultural importance of gemstones and jewelery? The time and effort it took maedhros to gain the fine motor skills to do it left handed?

#High King fingon is the best fingon I dont make the rules#maedhros x fingon#maedhros#fingon#silmarillion#jrr tolkien#middle earth#art

753 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maedhros: Doesn't wear much jewelry.

Fingon and Celebrimbor: New mission: Dress him in as much shiny jewelry as possible.

#silmarillion#silm#silm art#tolkien#the silmarillion#celebrimbor#telperinquar#tyelpe#fingon#findekano#maedhros#maitimo#lotr#noldor#click on the photo for more details. :)

417 notes

·

View notes

Text

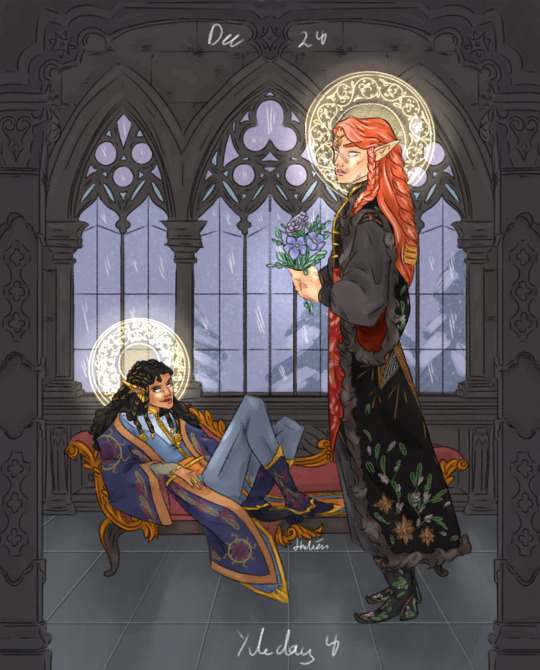

December; the 24

Yule day 4: Maedhros the tall & Fingon the Valiant

How many colors are used in the glass of the windows?

True blue Pansy; blue Pansy´s symbolize loyalty, honesty, devotion, and trust.

Bluehead Gilia; Bluehead Gilia is an annual herb with a self-supporting growth system. The Gilia has been used to treat blood disease over the years.

Fingon is in the free day clothes Maedhors just came in after some flower picking fully dressed; I also like to headcannon Himring fashion to include a lot of embroidered floral.

#a bit early than the others i know#yule calendar#tolkien#silmarillion#jrr tolkien#maedhros#nelyafinwe#maitimo#fingon#findekano#russingon#christmas calendar#christmas art calendar#tolkien art christmas calendar#silm art#tolkien art#my art#digital art

205 notes

·

View notes

Note

Congrats on the milestone! How about Maglor or Maedhros and jewellery, from the worldbuilding prompt list?

Digging up this old prompt for @maedhrosmaglorweek day 3! Have both of them.

"You will jingle as you walk," says Maedhros, "they will hear you coming for miles."

Maglor laughs, and tosses his head so that the dangling silver earrings chime. "A poor minstrel I will make, if my jewellery plays more music than I! No, Nelyo, these will not do." He removes them carefully, and lays them aside in the growing pile of precious metal heaped upon the side-table.

Maedhros, sitting cross-legged on the stone floor of his chambers in Himring, watches him with a faint little frown. "You must choose something," he says; "you cannot go to the feast dressed as plainly as a Vanya monk."

"My songbird's voice is adornment enough," Maglor says blithely, "and anyhow I did not come here to pick out my own gems. We must make some progress on deciding what to bring as gifts."

From the chest Maedhros draws out a long string of pearls, meant to be draped three times around the neck for the full effect. A souvenir from a summer Maglor spent in Alqualondë, long before the light of the Trees went out, or indeed before their father took it into his mind to preserve it. Maglor chose the pearls himself, going up and down a hundred beachside stalls to pick out those most perfectly round and white, and had Finrod his cousin teach him how to string them on a thread of silk before presenting them to Maedhros. How lovely they had looked set against his brother's fair skin; they had seemed almost to glow.

"These – these stones," Maedhros says, hesitant, "we could gift them to the envoys of the Sindar, perhaps."

Maglor swallows. "They are pearls, Nelyo," he says, keeping his voice light. Maedhros blinks at him, and he explains, "They come from the sea, from oysters. We used to get them from the Teleri." He pauses, and then, when Maedhros still looks bewildered, adds, "I do not think it good politics to gift them to the kin of those we slaughtered, whether or not they know of it."

Maedhros' face darkens. "You are right – Nolofinwë's host will murmur to see them, besides." He gives the pearls another troubled look and then sets them aside.

No use, Maglor has learned, in dwelling on these missing spaces in his brother's memory. They frustrate Maedhros enough as it is: and it is nothing personal, Maglor knows, that he has forgotten the pearls were a gift from Maglor. Their Enemy has taken from Maedhros things far more precious than the recollection of a trinket. It does not sting, that Maedhros does not remember.

Maedhros has turned his attention back to the chest before him. These are all his personal jewels, salvaged from their father's house in Tirion in the brief hours they had to pack before setting out on their ill-fated march. In the years of his captivity Maglor would indulge himself, sometimes, and open the chest, and admire the treasure within as though he were yet a fanciful child trying on his brother's baubles; and he would tell himself that he would hear Maedhros' laughing voice at the door any moment now, saying, Are you going through my things again, little magpie?

Maedhros does not much like to wear jewellery, these days. He says that it chafes against his skin, and on darker days that it puts him in mind of chains; occasionally he will consent to Maglor pinning back his hair with a bejewelled clip, or to an unobtrusive pair of earrings, but all his fine gold necklaces and ornate jewel-encrusted bracelets are useless now.

"Too few gemstones," he says now with a frown; "they were more marvellous than the metalwork, and would be better received."

Maglor thinks with some regret of a fine set of rubies his father had made him for his two hundredth begetting-day. Like all the house of Fëanor's best jewels, they were locked in the vault at Formenos, and stolen by Morgoth when he ransacked it.

"I know not how things are done in Doriath," he says, "but in any case the Mithrim Sindar are not over-fond of jewels, much like their Falmari kin. I do not think we need worry that our gifts will seem poor to them; in truth they will know not what to do with them. They wear flowers in their hair oftener than gems."

"It may be different in Doriath," Maedhros argues. "Findaráto says of Menegroth that the very walls are studded with jewels. Perhaps a gift of our own best would go some way towards earning Elwë's favour."

Maglor frowns. "Think you he will come himself, then?"

"Perhaps," says Maedhros, "but even if he does not we must not seem to be ungenerous. Many of those in Nolofinwë's host will be searching for any excuse to name us so." He passes his hand over his eyes, looking tired. Maglor only arrived yesterday, but he has his suspicions about how long his brother had gone without sleep before that. "We must choose presents for them too—"

"You gave Nolofinwë a crown," says Maglor; "surely he will be sated with that!"

The jest makes Maedhros laugh, as it would not coming from any of their other brothers, edged as it would be with resentment or mockery. Maglor is awfully, selfishly glad of that.

"Come here," says Maedhros, "you are distracting me. Help me choose what to give our own kin, at least."

Maglor settles on the floor beside him. "This for Findaráto," he says, picking out a necklace of sapphires that Maedhros never much liked in the first place, "it will go well with his eyes."

Maedhros favours him with a smile. "Well chosen," he says. Then he finds a very fine emerald, set into the front of a copper circlet but easily prised free, and examines it thoughtfully. This, Maglor remembers, is a relic of their father's first experiments with the art of capturing light; it does not shine with a light of its own as do the Silmarils, but catches and magnifies all the daylight coming through the window in a most pleasing manner, reflecting them back in every shade of green imaginable. Maedhros sets it aside, and when Maglor casts him a questioning look blushes and says only, "For Finno."

The next piece Maedhros draws out of the chest is a golden bangle, from Fëanor's filigree phase: the metal worked into the shapes of trees and flowers and leaping horses, studded all over with tiny gems in a multitude of colours. Their father was in a good mood, when he made this, Maglor recalls. The precision of the work appealed to him. Perhaps it was that more than the loveliness of the finished product that made Maedhros fond of it.

"You always liked this one," says Maedhros, his eyes warm now with recollection. "The number of times it turned up on your dressing-table, after I had spent hours searching for it! Here." And he slips the bangle onto Maglor's wrist.

Maglor tenses, forces himself to relax, and takes it off again. "I do not want it," he says, "thank you, Nelyo."

Maedhros blinks at him. "I cannot wear it," he says, "not a bangle, it will be – too tight." He shudders briefly and then masters himself. "You might as well take it, and then someone can have use of it."

You do not want him back, Celegorm spat once; all your mourning is performance only. You are quite content to sit here wearing his crown and playing dress-up with his jewels, in truth.

"I do not want it," Maglor says again.

"Káno," Maedhros says, very gently. He tilts Maglor's chin up to examine his face. "What troubles you?"

But how can Maglor tell him, I am not now the child you knew in Valinor, the little magpie who so loved to be adorned? How can he say, I too was sated with a crown? He cannot unburden himself to Maedhros, who so depends on him to be merry and bright and unruffled. He has lost the right to do so.

"It will get in the way," he says, "when I play my harp." Then he summons up a smile and says, cheerfully, "Five cousins yet to choose gifts for, and then you promised you would let me practice my new Sindarin songs after we dine! We had better hurry." And he turns back to the chest before Maedhros can object.

#asks#silmarillion#my fic#maedhros#maglor#echo-bleu#maedhrosmaglorweek#maglor is fine he's fine he's SO FINE ok

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

#silmarillion#silm#the silm#the silmarillion#feanor#sons of feanor#maedhros#fingon#russingon#nerdanel#ambarussa#fingolfin#silm poll

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

House of Feanor going to the festival on taniquetil

feanor refused to dress up (or even wipe the soot off) specifically to spite manwe.

maedhros picked out a nice appropriate fancy outfit. maglor is dressed for one of his concerts, complete with jewel dust in his hair and pearl strings on his sleeves. celegorm is wearing his orome cosplay like it's valarcon. caranthir is wearing like. the elf equivalent of a business suit and curufin was going to dress up but he had to drag both feanor and celebrimbaby out of the house and ended up forgetting his coat

the ambarussa were supposed to be dressed as various maia of orome (to match celegorm) but amrod forgot about the festival and went for a walk. amras had to retrieve him last minute

nerdanel just put on some basic jewelry and a nice cape thing over her normal clothes

#silm#silmarillion#house of feanor#maedhros#maglor#celegorm#caranthir#curufin#amrod#amras#ambarussa#feanor#nerdanel#amras is dressed as tilion#they were going to wear wigs but nerdanel didnt let them#she identifies everyone by hair color in a crowd#not pictured: they brought huan and dressed celegorms horse as nahar

335 notes

·

View notes

Text

revenant

maedhros & nerdanel | t | ao3

The first sound he remembers is a woman’s voice. It is soft—there is sadness in it, at first, before it is overshadowed by an artist’s precision, sentiment giving way to craft.

“Yes,” she says, “quite right, for the shade of his hair; only it has been finer, and curled less. He was not quite so tall—his memory betrays you there. I would have him brought down perhaps half an inch. His eyes—”

The first touch he remembers is a calloused hand on the side of his face, a caress along his cheek. Fingers gently pulling back his eyelid. A glimpse of a marbled ceiling, columns decorated with sculpted stone flowers, all white. He can feel her lean over him. Can see her hair. Fine and brown, very slightly curled. Almost red.

“The shape is right,” she says, “and the eyelashes. But I do not remember them so pale.”

The first scent he remembers is hyacinths, and then rock dust. Wind tickles his skin. He turns his head and sees her, bending over him. Her face is unwrinkled, her lips pale, cheeks a little pudgy, eyebrows and eyelashes a chestnut brown.

“Are you awake, Maitimo?” she asks.

He nods.

Some cloud flits over her features at that, some grief, some doubt. Old hurts hang in the air between them. Then she quashes it. Speaks, now, to him. “Say something.”

“Something,” he echoes.

She smiles. Her voice carries the same dispassionate notes of a craftsman. “He would answer me so,” she says, “yes, quite right on the sense of humor. But his voice had not been so raspy.”

He swallows. Reaches to feel at his own throat. “I smoke,” he says, “it’s a bad habit.”

The woman turns away from him. He cannot see whom she speaks to. “I do not remember him smoking,” she says.

They change his height, and the texture and curl of his hair, and the glint of his eye. But itch for tobacco never leaves him.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

The woman is his mother. It is not usual, he is told, that she had been there at his rebirth. But he had not been able himself to speak for any adjustments that need be made to his body, for he does not remember what it had been like before

He walks with her through the white city, made of marble clean as bone. Low domed cathedrals, tall gleaming towers—statues, all white, of elves and not-elves. Here is one of an elvish woman hewing stone; here is another, of a star-crowned king. The inhabitants of the city are a stark contrast to the buildings, dressed in silks so bright in color they seem to be distilled light. To his eyes there is something a little comical to them.

A child’s drawing, he thinks. The background left untended to, but the principal characters colored in.

(It swims before his vision then, briefly; dark inch lines drawn onto parchment, sketches of lairs and fortresses, filled in by a child’s hand with cheerful watercolor. He leans towards the memory, but cannot touch it.)

“You made me too tall,” he tells his mother, half-laughing, “look, no one is as tall as I am. Everyone is staring.”

“None of that,” she tells him, “you are just how you were meant to be, Maitimo.”

He does not feel made-right, made-well. He feels huge, ungainly, his limbs too long and his shoulders too wide.

They walk along the dirt road. Grass begins to cover it, here and there. Plainly horses and carts rarely come this way; only single sets of footprints, so light they barely leave behind a path.

His mother’s house is carved out of the side side of a hill some ways away from the city. One big room in the center, tall domed ceiling, skylight carved into the very top of it, where the peak of the hill must be. Under that light there is a block of white marble, chipped in four places but indistinct. A chisel lays atop it.

Little coal-stove, in the corner. Scattered dishes, clean but disorderly. Half loaf of bread and a little jam, black currant. Hard cheese.

One wall unfinished. Three walls of wood, and one of dirt.

Seven chests in the corner by the dirt wall, stacked atop each other. Seals on the latches of the chests, like eight-pointed stars with one point broken off.

Two rooms branching off, dug-out and reinforced with oak-wood. They are dark, and he cannot tell what they are without stepping inside.

“This is yours,” his mother tells him, of the right. He hesitates a moment, then goes. Sees the bed in the corner, wide and soft, hanging tapestries. There are four robes for him, in same bright silks everyone else had worn. Green as the first leaves of spring. Lilac, shimmering slightly even in the darkness. Bright, pretty coral-pink, decorated with embroidered leaves in yellow and purple, slightly raised and pleasant to the touch. Sky-blue, with patchwork clouds.

“They were yours once,” his mother tells him. “Long ago.”

His own robes, he notices, are a mottled grey. The color of a spider-web, he thinks, of dust. “How long?” he asks.

His mother shuts her eyes, as though counting. “Seven thousand years.”

He has some vague notion that in the damp clothes spoil, especially in so long a time. That moths eat holes in sleeves. That seams come apart. But when he asks she looks at him oddly.

“Nothing spoils, here,” she says, “do not be silly.”

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

They eat. There is one chair at the wooden table in the corner, so his mother brings a stool from the workshop to sit on. The jam is sweet and sour, just how he likes it. The bread is perfectly soft.

“Why do I not remember this?” he asks, pulling at the sleeve of his new, blue robe. “Why do I not remember you?”

His mother hesitates.

“You burned,” she says, “you burned and there was not enough left of you to put such memories together. You’re right handed, dear.”

He switches his knife to his right hand.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

She leaves him to rest and to gather himself. He wishes for smoke. Walks around the perimeter of the bedroom she’s given him and looks over every item.

A writing desk, prettily carved from dark oak, scratched with use. Pleasant, beneath his fingers. Familiar. Atop it—

A crystal ball, cold and heavy in his hand. A little light trapped within it, iridescent purple-red. He brings it up to his face and blows hot breath onto its surface. Sees age-old fingerprints on the smooth surface, there and then gone again.

Parchment, most of it blank. A few notes, scattered here or there on the papers, in beautiful, looping script, though he can make no sense of them. A snatch of a poem, rhyming turning eyes with burning skies, a note to procure radish-seed. Starred, and underlined—write to Elemmíre, Káno cannot play at the lilac-bloom festival—exile. A half-written apology, unaddressed, for a slight he cannot even begin to guess at.

He picks up the quill, and dips it into the inkwell. Feels scratch of the parchment under his touch as he writes:

Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play.

Three lines, neatly underneath the first. His hand is nothing like the hand of the first writer, his letters sharp and distinct and lonely where they ought to touch, ought to loop, ought to overlap. Maybe this is his mother’s writing, he thinks.

Though she had not seemed one for poetry, nor for ambling, awkward apologies.

Shelves. Books on history, on poetry. He runs his fingers along the spines and knows he has read them—can summon even the memories of the opening stanzas and chapter-headings. How odd, to remember these but not his mother. A flute, silver and black. Candles.

The bed is certainly his, for it is over-long. There is one blanket on it, a light thing of shimmering purple silk, and—he laughs to see it, then thinks he might weep—a little stuffed lamb, with cotton sewn onto its back to make fluff. He lifts it to his face, and breathes deeply.

It smells of sleep, of rose-soap, of tears. Its name dances somewhere just out of reach. It is not mine, he thinks, I gave it to…

But he cannot finish the thought. He sits, holding the little sheep in his lap. His fingers twitch.

Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He does not mean to sleep. He is not sure he does, truly. Only that he is waking. With his left hand he is holding the little sheep to his chest. His right hand is bound, above his head. His shoulders are stiff and ache.

He sinks his fingers spasmodically into the lamb’s fur. Shakes.

Yanks his hand down, expecting to feel the chain bite at his wrist. There is nothing, because his hand is gone, because—

Because.

Sits. Stares at two hands, clenched around the stuffed lamb. Too tight. Strangling it, poor thing. Poor thing.

He breathes in deeply, smelling again the rose-soap, the tears. Outgrew it, he thinks. Gave it away, gave it to—

There is a longing in his chest, like half of him missing. The burned half, he thinks. He shuts his eyes and tries to picture it, but nothing comes. Somewhere in the other room he can hear a faint clinking, a shuffling, steps. An image swims in his mind, an elf; dark-eyed, dark-braided, pouring liquor, mixing herbs and honey.

For some while he lies and holds the lamb, listening to the movements outside. Then the soft light of the crystal ball becomes oppressive, and he rolls out of bed. Feels the cool wooden floor under his feet. Slips outside.

If he is disappointed to see his mother in the main room, standing by the little oak table and mixing tea, he knows better than to show it.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

They breakfast outside. Pomegranate, a day past ripe and a little soft with it. Honey. Crumbling cottage cheese.

He notices for the first time how far they are from the city through which they had passed. There is a dirt road, half-covered in grass and little-tread. No one passes by them.

In the light of day he can see how their blood runs together. The sun freckles them the same. Bleaches his mother’s hair into a shade resembling his. He sees the square angles of his body in her big, calloused hands, in the set of her shoulders. But that is to be expected, he supposes. She made him. Shaped him, out of whatever he had been before this.

He expects she might speak of who he had been, but she does not. She sits and eats, sits and watches him. He cannot think of something to say, and follows her example.

“You want something to do,” she says, as they stack their plates.

“Yes,” he says. In that she knows him. Already he feels too idle, too stagnant, caught without a purpose.

She takes his plates. She gives him a shovel. A hammer. A chisel. She brings him back inside, and bids him dig.

“Here?” he asks, running his fingers over the dirt wall.

“Yes,” she says, “there is a lot of work to do, Maitimo. We will have a hall, and five more rooms. The hill ought fit them.”

He drives his spade into the dirt. Mostly clay, he thinks. It’ll hold well.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

They work in shifts; first he digs and his mother takes the pile of dirt and carries it out. Then she digs, and he lugs dirt.

After some time his shoulders begin to ache, new muscles responding to unfamiliar work. It is a pleasant ache, the shape of it familiar. It is almost odder, he thinks, for his back not to hurt.

The work is mediative. They do not talk during it, beyond the exchanges necessary to the work—“give me that” and “rock, I think,” and “steer leftwards.”

When the sun falls pink-orange through the skylight they cease their work. She hands him a broom to sweep the last of the dirt off the wooden floor. Gathers up the spade and the chisel, and washes them.

They walk together out of the hill, and bathe in the river. The water is warm. When it sprays out onto his face he opens his lips and tastes it, almost sweet with its clarity. When he dives it whips his braid around his face.

They return.

She goes to ship at the square of marble. He goes to his room. Shoves down the ever-present craving for tobacco. Sits at the desk. Reads by the light of the crystal ball, old books of poetry.

He is not surprised he knows every line.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

Neither of them sleeps. In the morning they resume they work again, digging the tunnel. He starts to leave the door open, when he goes to empty the pile of dirt, knowing he shall return to it soon. She closes it, each time. He does not ask why.

The rhythmic movement of the shovel becomes second nature. Around it all thoughts cease. All that is left is the motion, the sound, the heft. He does not notice at first he is putting words to it.

Thumpthump. Thump-thump. Thumpthump.

Káno can-not play. Káno can-not play. Káno can-not play.

It is odd. He has read better poetry.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

On the fourth night he sleeps again, and dreams of the scent of burning tree-sap and screams, of dark soot staining his hands, of a woman that falls and screams, and screams, and screams. Wakes clutching the lamb to him and calls out for a name he cannot recall again.

For breakfast she poaches eggs. Cracks them each onto upturned plates with suns painted on. Swirls the water around the pot to as twisters turned inside out. Clink of the teaspoon against the black edge of the pot. Then the eggs go on, one by one, and turn around.

“Your father used to do this,” she says, “I never cooked. Only the bread.”

He holds out a hand. “Let me,” he says, and she steps aside. He picks up the spoon. Swirls eggs.

“Good eggs,” she says later, when they sit and breakfast on the grass.

He tears off a chunk of his bread-crust with his teeth. Chews. “Good bread,” he says.

The patterns of leaves dance over her arm. Shadows, in the sun.

“Right hand, Maitimo,” she reminds him.

He moves his fork. Takes a bite of egg, and feels the yolk on his tongue. “Are you angry with me?”

“I do not mean to be,” she says, which is answer enough. She must see it on his face, because she puts down her fork and looks at him. “It was all very long ago.”

He nods.

She reaches over to lay a hand on the side of his face. She has not touched him, since the first day, and now she strokes his cheekbone. “I wanted you,” she says, “I begged for you.”

He shuts his eyes. There is soot on his hands. The ocean is angry, horribly angry with him. “Did I burn,” he says, “aboard a ship?”

She stares at him.

“I cannot say,” she says. Then, more forcefully: “my Maitimo might have, I think.”

He leans into her touch. It does not last long.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He expects the summer to pass, but it never does. The sun rises at the same time each day, and does not go down for a long time time. They eat sliced peaches and flaky pastries and spinach-wraps and perfect fall apples, goat milk and sour bread, carrot stew, eggs made in a startling variety of ways, candied flowers. He learns where the food comes from; once every twelve days a young elven girl comes, carrying covered baskets on her head, and his mother takes them from her and tucks them into the dug-out place beneath the hill, where the earth and the ground-water keep them cool.

(He wonders why it matters. Nothings seems to spoil here. She could leave them in the heat, he thinks, and they would be fine.)

Sometimes the girl brings them letters. Some seem formal, rolled into official-looking tubes and sealed with wax. Others are clearly hastily written, scrawled on one scrap of parchment or another, sometimes with sketches on the back.

Usually she will open them at the table, and name the relation who had written to her but not the contents. “My sister in law,” she will say, or sometimes, “my father,” or, once or twice, “your cousins.” Sometimes it is a patron in Tirion that writes.

One morning a letter arrives sealed with dark blue wax, an address scrawled along the edge she reads but does not voice aloud. She tucks it into her inside pocket and does not speak its sender, ignoring his curious eyes.

They dig.

As they go further they must pull up more and more rocks, must navigate around sandy areas that fall when touched. His shoulders no longer ache with the work. Indeed he grows so used to it that it is odd not to do it, that it begins to pull at him to spend time idle.

During the nights she chisels away at the marble slab, working by moonlight, and he reads, or else goes to swim in the river. At first she is wary to let him go alone, but after the third time he returns unwavering at dawn she stops tracking him.

The marble begins to take shape. An animal, he thinks. A four-legged thing, bent low to the ground.

“Did you make the statues in the white city?” he asks her. It is night, then, or perhaps the first note of morning. The moonlight is gone. He has stopped reading, but she has not finished her carving.

“Only the good ones,” she says, half-laughing. It is not a joke.

He picks up the pan. Stokes the fire, to make breakfast. Picks up the knife, unthinking, with his right hand. In the faint light his own hand is pale as marble. Carefully carved.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

After some time he begins to call the little lamb Káno. The odd nights when he comes to sleep he holds it to his chest. Through his nightmares the scent of rose soap never fades from its cotton sewn fur, and he begins to tell reality apart by it.

There are the snatches of his dreams, the screams, the song, the slow grinding of war-axes and the rattling of fortress doors. There is the icy forest, the kind that doesn’t truly exist in real life because winter does not exist, and snow does not exist, and one does not dash madly between ice-covered pines chasing the prints of bare-footed children. Then there is the smell of rose soap, and the softness of the cotton under his cheek.

(Sometimes he thinks Káno is in the next room, clinking around, humming under his breath. But that is an odd thought, because Káno is a stuffed lamb.)

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

“We are done digging, for now,” she says. The state of done digging should naturally follow the state of digging, but he has somehow failed to realize it is possible. But there it is, the tunnel. Five rooms branching off. “We must now go for wood.”

She gives him an axe. He looks down at it, and sees the dusting of red clay on the head first as blood, then as rust.

(Nothing rusts, he reminds himself. Rust is an idea in his mind with no real-world equivalent, like rot and ice and decapitation.)

They walk together along the overgrown dirt road, pulling an ass-drawn cart behind them. Not towards the city, this time, but away from it. The path fades, and fades, and fades, until there is nothing left but her intuition.

The wood is ancient, and untouched, pines tall and dark, their trunks many times the width of their shoulders. He reaches out and lays his hands on the bark, feeling its dark, deep ridges.

“The tree will bleed,” he says, “when we cut it down.”

“Yes,” she says, “so it will.”

She takes his hand, and draws it up to touch the deep green needles on a lower branch. When she begins to pray he knows the words, and echoes her. Together they ask for leave from Yavanna; together they promise to take no more than their due, and to pry the seeds from the pinecones of the fallen tree and plant them.

Then she makes the mark, and he begins to chop.

Some part of him expects soft yielding flesh under the axe-swing, expects gore, expects blood spray over his upturned face. Instead his axe hits hard wood, and only yellowish pine sap springs up around the cut.

It is long work, to reduce a living thing into material. First the tree must fall. Then it is cut again, to be rid of the thin branches for which they have no use; then again, to fit on the cart. Then they collect pinecones and twist them open, shake the seeds out and bury them in the dark soil, beneath the layers of dry pine-needles. Carry water from the river to drown them.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

It is dark when they make their return. His body aches in new ways with new work. Pine-sap clings sticky to his hands, his green robes. He wants to chase the dew gathering in his lungs away with smoke.

“The river,” his mother says, and he nods. But the water cannot wash the sap from him, and he goes to bed with his hands still stained.

He will not touch the stuffed lamb, except with the back of his wrist, to knock it from the bed. It stares at him plaintively from the floor, and he pities it.

“I am sorry, Káno,” he says, “but if I touch you you will be ruined. You are made of soft things, and shall not be washed clean.”

In his dreams there is a little boy, bright eyed and loud. He plays the flute, the same silver flute on the shelves, and laughs, high and bird-like, twirls in pretty mother-of-pearl court robes. When he reaches out to touch this child he sees his hands are covered in blood, that he has stained everything; the boy and the flute and the mother-of-pearl, and nothing is merry.

Then he stirs, half-wakes. Slips back down into his dreams. Now there is a figure above him, amber-eyed, more fair than any elf he can remember laying his eyes on. He has an axe in his hand, stained with red clay, and he raises it and hews off his right hand.

Oh, he says, unbothered, well, don't worry about it. I've still got my left.

But tree-sap keeps pouring out of the cut on his wrist, spewing in messy, sticky arcs, staining the other elf’s gold-beaded hair and his cheeks and his lips and his eyelashes, and he will drown, he will drown.

When he wakes there is no smell of rose-soap to cling to. He curls up on himself and thinks he must have come from a different world, a worse world; that he is a stained and broken thing forced into a clean body. He does not belong here, he knows.

He wonders what it would be, to go back. Wonders if he’s scared of it.

Then he slips outside, and bids his mother good morning, and sits trying to clean his hands. Chops spinach into fine little slivers; beats it with cheese and with eggs, pours it into the pan to cook. Watches the edges crisp up, fine bubbles forming on the surface.

His mother stirs sugar into tea. He misses someone so fiercely he feels his chest a hollow, empty thing. They slip outside to breakfast. The sun greets them, cheerful and warm.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

They chop the wood into boards, long to accommodate the hallway, wide. His mother has a better hand for it, at first, but he is quick to learn. The first days they speak of nothing but craft.

When they sit polishing the wood the sap has nearly come off his hands. Perhaps he has grown new skin, and the sap has flaked off with the old.

“Who will live there,” he says, “in the new rooms?”

She looks up at him. Her sleeves are hiked up, the board in front of her gleaming bright in the sun. “Your brothers.”

He has thought so, though he could not have voiced it.

“There are five,” he says, and knows it to be a question. He thinks she nods. “Who is next, after me?”

For a moment she hesitates. “Tyelkormo,” she says, “if he is granted to me.”

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He touches the edges of the eight-pointed star on the sealed chest. The broken point. She sits behind him and reads one of her letters. He can see another still-sealed underneath, the one she had not announced to him.

I have five brothers, he thinks. I am one of six.

It does not fit. Shoes too small in the toe, pinching uncomfortably.

For the first time he can remember he feels angry, truly and properly. Kicks at the lowest of the chests, then yelps in pain at his foot. Tyelkormo, he thinks, Tyelkormo, Tyelkormo. Who can need you? Who can want you?

The woman who is not his mother looks up from her carving, but says nothing. He will tell her, he thinks, when their work is done.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

But he breaks. The secret is too heavy on him; he cannot take it. They sit, and polish boards. It is an endless task.

“Maitimo,” the woman who is not his mother says, “hand me the sponge.”

He hands her the sponge. “I am not he,” he says, quite casually, “they brought the wrong soul back, and put it in your son’s body. I am another creature, and I think an evil one.”

“Oh,” she says, “and why is that?”

“There are evil things,” he says, “in my mind. I know not this land, but another. I dream of ice and bloodied hands and scared children.”

For some time she turns from him. He is sure she weeps. He would touch her, but it is not his right. He looks down at the board, working his brush in random patterns.

“Against the grain, Maitimo,” she says.

He turns his brush against the grain. They do not speak of it again.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He likes to run his hands along the polished wood. Likes to press wood-braces into the soil. Likes the neat sharpness that they give the tunnel, the way it begins to take the shape of the house.

“Did you do the same for me?” he asks, as they hang up curtain-doors.

“Yes,” she says.

“There was a different home,” he says, “where the chest is from. The bed is from. K—the lamb.”

“Yes,” she says.

For some time they work in silence. He braces the doorframe, and she hammers in the nails. Then they switch.

“What are you carving?” he asks. “I thought it a sheep.”

“No,” she says, “only an elf hiding under the wool.”

He nods. She nudges him, to step aside. There is a little window on the other side of the room, the sloping end of the hollow hill. She measures it, for a frame. Writes numbers on the inside of her arm in charcoal.

She taps him on the elbow as she passes him, beckoning him to follow. Outside they trim the wood into shapes to fit. He holds, she saws. Then she has them switch, so he may get the practice.

“I have gown too used to solitude,” she says, as they brace the corners of the window-frame with metal. “I have no words left. I thought it would be easier, to speak to you.”

He looks up. For the first he sees the weight of her own neurosis on her, the weight of her pain, her fear, her loneliness. For the first time he thinks she might touch him, if she remembered how.

“How long has it been?” he asks.

“Six thousand years,” she says. “You spend dead nearly twice the time you spent living. But I lost you sooner, of course.”

They carry the window frame inside. They fit it.

It will have a good sill, he thinks. Perhaps Tyelkormo will like to sit on it, and watch the birds.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

It looks like a proper house, with the last of the boards fitted to the floor, to the walls. The woman who could be his mother tells him that there is not so much left to do; only to make make the bed frames and the shelves, fitted to each of them. Only to open the chests and lay out what she had saved, of them.

“Saved from what?” he asks.

She looks up at him, as though surprised he does not know. “The building was torn down,” she says, “the king’s body was inside.”

She makes a gesture with her hands, first twisted together then falling. Tower. Splat.

Do people die here, he wonders, or had the king been simply waiting to be born?

“Tyelkormo will want hounds,” she says, “on his bed frame. Likely in the house, too.”

So he sits, and whittles hounds. They turn out crooked, their noses too long. She has him try again, and that is better.

Káno cannot play, he thinks, the repetition of a song stuck in his head, Káno cannot play. Káno cannot play.

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

“I cannot tell,” he says, setting a book of insect sketches next to a fox-skull on his brother’s shelves, “if I know him.”

His maybe-mother turns to look at him. Her face is drawn.

He touches the bone. It is familiar, at least. Smooth. Oddly delicate, for what it is. In places the smooth surface has peeled off, and it is porous. He could hold it in his hands and squeeze the barest bit and watch it crumble.

“Sometimes I think I am your son,” he says, “but that something wrong has clung to me, as the tree sap has. Some other world I saw, in death, that lingers upon waking.”

She takes his hands. Holds, around the fox skull. Her fingers do not touch the bone.

“Do not leave me,” she says, “do not go there. Promise me, Maitimo.”

-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

He tosses dumplings into broth, one after the other. She sits across the table from him. Her eyes follow their fall.

“I have not told you everything,” she says.

You haven’t told me anything, he thinks. But that is unjust. She has told him how to chisel stone and chop wood, how to polish floorboards, how to whittle hunting-hounds, how poach eggs.

She reaches past him, across the table. Picks up the parchment sealed with blue wax.

“I didn’t want to give you this,” she says. For a moment she holds it close to her chest, so that he cannot help but suppose the ending of the sentence will be so I won’t. Then she holds it out to him. “It is for you. You were betrothed.”

“Oh.” He reaches for the paper. He cannot tell if that seems right. If it is true of him. “Perhaps I was.”

“I am not sure,” she says, “how serious you were about it.”

An old instinct almost calls him to argue. To cry, I will, I will, after—

But after what?

He breaks the blue seal. Twirls open the paper.

The handwriting hits him with a note of such intense familiarity he cannot see the meaning of the words. His head swims.

The first time he remembers weeping is in the kitchen, holding a piece of parchment to his chest, and it is over the slopes of his lover’s letters. Behind him the fire crackles. He feels his chest cave in.

Maedhros, his lover writes, I grow tired of waiting for you to call to me. If you have gotten it into your head that it is your righteous duty to crawl into a ditch and die, speaking to none, we shall have words...

Maedhros does not make it past that opening line. He shakes with the clarity of the voice in his mind, its low, musical quality, its sardonic lilt. How well he can sense the desperation behind it. I know you, he thinks, I love you.

The woman in the room with him steps closer. She looks at the letter, but her eyes do not move to read the words.

“I never learned it,” she says, “some last defiance of your father. As though if I did not speak it it could not touch me.” There her voice breaks, her pale face flushing. "What do you think of that, Maitimo? Me lobbing one last insult at a long-dead man, and hurting myself by it?"

Of course, Maedhros thinks. It is Sindarin. He knows it, though he cannot say how. He’s thought in it, now and then, without noticing. Perhaps if he had spoken more he would have used it.

He lowers the letter, and looks at the woman who had once been his mother. In the shadows here she seems as white as marble. How odd, to think of her, all alone, beating the shape of sheep’s wool out of stone with a chisel. To think of her hollowing out the hill to make room for him. To think of her clawing him back from the dead. To think of her carving herself out of loneliness and defiance and love and anger.

Well-made, she called him.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maedhros & Maglor Week Drabbles (#6)

For @maedhrosmaglorweek day 6 (respite), have 100 words of post-canon M & M.

Old habits die hard. Returned Maedhros uses his left hand instinctively for most tasks, bracing and bolstering with his right wrist rather than engaging those fingers. When his new hand grows sore and stiff from lack of practice, it is Maglor who contrives a solution that will not tarnish his brother’s pride. Posed every afternoon before his dressing table, languidly considering earrings and collars and pendants for the evening’s engagements, he tasks Maedhros with the braiding of his hair: three strands, at first, then nine, then twelve, then twenty or more. The delicate twining heals, affirming both craft and love.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hands

Maedhros, Elrond, and Elros. Rated G.

"You're really going to teach us to fight?" Elros asked, eyeing the practice swords that lay on the ground near Maedhros' feet. They were wooden and sized for the boys, and now he knew what Taraharn had been so busy with for the past few days.

Maedhros nodded. He was dressed in a simple tunic and breeches, his long hair pulled back from his face, and he was leaning on a wooden sword of his own, this one much longer, more suited to his great height. "You're old enough to learn," he said, "and I would have you able to defend yourselves. The wilds are a dangerous place. You know that."

"Aren't you afraid that we'll kill you someday?" Elros said. Elrond shot him a disapproving look, but Elros ignored him; he had always been more blunt than his brother, and he had no qualms about bringing up the truth of how they had come to live with the Sons of Fëanor.

"I do not fear death, Elros," Maedhros said. It was a sentiment Maglor had voiced before, but unlike Maglor, when Maedhros said it he spoke the truth. "Besides, I believe you have more sense than to try. It would do you no good."

Elros had to concede the point. Even if Maedhros and Maglor refused to defend themselves from the boys — and that alone was a big if — there were certainly people among their followers who would not hesitate to avenge their lords. "That's true," he admitted.

Elrond rolled his eyes. "I don't feel like killing anybody except Orcs," he said. "Let's stop talking and get started."

That got a half-smile from Maedhros. "Take up a sword," he instructed. "It doesn't matter which; they're identical in all the ways that matter."

Elros and Elrond looked at each other, shrugged in unison, and each picked up the sword closest to them.

"These are meant to be used with one hand. Maglor will teach you the two-handed method, for obvious reasons," Maedhros said dryly. "Now, hold it like this, but in your right hand. We'll start with your dominant arm." He demonstrated with his own sword, and the boys copied him. "Good," he told Elrond as he examined his grip.

Elros received no praise. Instead, Maedhros handed his sword to Elrond, saying, "Hold this." Then he took Elros' hand in his own, adjusting the position of the boy's fingers. "You want your thumb here," he said. "It minimizes the risk of injury to your hand if you block a blow close to the cross-guard."

Elros nodded, but his mind wasn't on Maedhros' words. Instead it was fixed on the calloused, scarred hand wrapped around his own — a hand that was celebrated in song for its owner's deeds in the Dagor Bragollach, but also a hand that had slaughtered his mother's people twice over. Was it irony that this hand would be the one that taught him and Elrond to fight, or was it simply misfortune?

He didn't know, and he was snapped out of his reverie by Elrond elbowing him in the ribs.

"Elros," Maedhros was saying, "are you listening to me?"

"I'm sorry," he said, looking up. For a moment he thought he saw the dreaded Kinslayer standing before him, but he blinked and the man became simply Maedhros again, tired-eyed but patient. "I was just— I was thinking," he tried to explain.

"Thinking is good, but try to keep your thoughts focused on the present," Maedhros said. "Otherwise there is no point to these lessons." He took his sword back from Elrond and held it upright in front of him. "Now, copy me."

#elrond#elros#maedhros#the silmarillion#silmarillion fanfiction#silmfic#tolkien fanfic#tolkien#silm fic#kidnap dads#kidnap family#kidnap fam

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Show Me Your Devotion

CEO! Maedhros x reader

Kinktober 2023: Cockwarming

A/N: I decided to forgo adding the requests to the post since they were released before over here » List of Requests

Requests: fem!reader, cockwarming, exhibitionism, mean Maedhros, jealousy

Words: 2.2k

Synopsis: Becoming friendly with your new co-worker does not bode well with your boss. Unfortunately for you, his method of teaching a lesson lacks decorum.

“I hope you won’t mind showing your friend that you belonged to another, and he shouldn’t stare shamelessly,” he stated, a self-assured smile playing on his lips.

Extending his finger in a beckoning motion, he signalled you to come around the table. It didn’t take long for you to grasp the implications of his intent. This wasn’t the first time you’d been beckoned like this; each occasion held different motivations. As the reality of his proposition sunk in, your heart quickened. You understood what he was suggesting—a daring move that defied norms and boundaries. The anticipation in the air was palpable as you considered your choice, navigating the delicate balance between professionalism and intimacy.

With a mixture of trepidation and excitement, you approached him, each step carrying a weight of significance. The space between you diminished, the world around you fading as you settled before him. He occupied your grey office chair with a composed ease, his fiery ginger hair pulled back into a neat half updo. His attire harmoniously blended with the monochromatic palette of greys and blacks that dominated your workspace. The minimalist design of your office found contrast only in the ceiling-to-floor glass walls that adorned two sides, offering a glimpse of the outside world, while the remaining two sides boasted laminated black oak wood.

Those silver eyes remained unwavering, fixed on you from the moment you stepped closer. Sharp and narrow, they roamed over your form—your teal dress, the modest slit at the back, the simple sweetheart neckline—all components chosen to exude professionalism and poise. Though his expression remained firm, a knowing smirk played at the corners of his lips, hinting at a twist in the confrontation. “I see he’s due to deliver summary reports within the next,” he glanced at your desk clock, “half hour. I have a proposition—a way to put an end to this drama.”

Was it shameless of you to easily be dissuaded by the severity of the situation and abandon it all for a taste of dick? You wrestled with a sense of shame as you contemplated yielding to his proposition despite the seriousness of the situation. It seemed unprofessional and unethical, especially with your co-worker’s impending visit. You couldn’t predict what else Maedhros had in mind, and his demeanour only fuelled your desire to wipe the self-arrogant smirk from his handsome face. It wasn’t fair for someone as perfect as him to wield such power and make demands. You found yourself on the brink of willingly dropping your underwear—reserved solely for him—and complying with his audacious request.

You urged yourself to exhibit a modicum of decency, especially after he had accused you of potential infidelity. It was becoming increasingly evident that his persuasive abilities were far-reaching, particularly when it came to manipulating your emotions.

Suppressing a sigh and rolling your eyes, you decided that this would be a brief encounter. Awkwardly and hastily, you removed your lacey panties under your dress and placed them into his outstretched hand. He accepted them with an air of expectancy and placed them into his pocket, gesturing for you to come closer. As usual, he took a hands-off approach, leaving you to initiate everything—typical behaviour after his initial accusations.

You nonchalantly unzipped his pants, pulling out his length as if it were a mundane task. Holding it in your hand, you noticed it appeared more robust than your previous encounters; the head was flushed and beads of precum formed, while the veins stood out, reflecting both frustration and irritation. Time was of the essence, so you reached for the hem of your dress, pulling it upward. But as it reached mid-thigh, you froze, casting a panicked look toward Maedhros, then darting your gaze toward the open door. His voice cut through your thoughts. “Don’t worry about the door. Nobody will see unless they deliberately enter. And if they do, and they speak about it...they’ll be dismissed. Now, hurry up and take your place.”

Rolling your eyes at his casual attitude, you glanced at the still-open door and refocused on the task at hand. You pulled your dress up to your waist, shivering as the air hit your skin. Maedhros’ hungry gaze met yours, and he impatiently gestured for you to approach. You complied, allowing him to guide you into position. Sliding closer, he settled you on his lap and aligned his cock with your cunt, toying and rubbing the tip throughout your folds before slipping in.

Both of you sighed with a mixture of satisfaction and pleasure as you settled onto his lap. The sensation of your warm walls embracing his length, your arousal coating his cock and gathering at its base, elicited a moan from both of you. His fingers pressed into your waist as he relished the feeling, while your ass blocked his usual view, he knew that your arousal was likely creating a pool of cream at the base of his shaft. He could sense your muscles clenching and releasing around him, longing for more than just a stationary connection.

After allowing a moment for the sensations to settle, you shifted slightly, adjusting to the sensation of being impaled on his cock. The size and texture filled you deliciously, and you couldn’t help but appreciate the sensation of being stretched by him. However, your movement was halted as he stopped you, pulling you into an embrace against his chest. “Not so fast, princess,” he murmured. “I said to sit, not to ride. Consider this a payment for the rumours I had to endure about us.”

Scooting his chair closer to your desk, he shifted within you, the movement causing his cock to glide against your inner walls. Each motion sent sparks of pleasure through you, and you could feel your body responding to his touch. The pressure against your sweet spot was almost unbearable, and you felt yourself on the brink of release. The weight, size, and curve of his cock all combined to create a tantalizing sensation that you were denied the full pleasure of experiencing. Your role was simply to sit there as he desired, warming him for later use if he deemed it necessary.

“Mae are you serious?” you whispered, a mixture of frustration and disbelief evident in your voice.

He hummed softly, his chin resting on your shoulder as he placed a gentle kiss at the base of your neck. “Yes. Now, be patient and wait while I go through your reports,” he instructed, nonchalantly flipping open the folder and scanning its contents.

“All this because I decided to be friendly with a co-worker of mine,” you huffed, voice oozing with annoyance. As you articulated your thoughts, you found yourself growing increasingly frustrated at the need to explain such a straightforward situation to the CEO—a man of maturity who must have faced his share of rumours over the years. Your exasperation mingled with your deep affection for him, creating a blend of emotions that left you torn between the desire to defend yourself and the disbelief that he’d give credence to such baseless accusations.

“No sweetheart, all this because your co-worker doesn’t know to keep his eyes himself and requires being taught a lesson,” he corrected.

As you sat there, your breaths coming in ragged gasps, you looked at him incredulously. Accused, then made to sit and wait, either until he was ready or until your co-worker entered and bore witness to this unholy situation. Fuelled by the belief that you could provoke him into a quick encounter, you involuntarily clenched your inner walls around his cock, hoping to stir his arousal and prompt him to take more decisive action. But instead of the response you anticipated, he merely pinched your thigh and returned to casually flipping through the papers, humming softly to himself. “Behave!”

As time went on, your excitement and desire only increased, resulting in a steady flow of your arousal onto him. His pants around the base of his cock were damp from your essence, yet he seemed unaffected by it. Knowing Maedhros, he likely had a spare set of clothes somewhere in his office, a lesson you’d learned from the years of passionate encounters that had taken place on his expansive desk.

“Mae, come on! Do I really have to sit here and warm your cock until my co-worker comes in?” you turned to observe his unbothered disposition. “Can’t you just, you know, bend me over your desk and get on with it?”

“Is that what you desire of me, or do you want your friend to see you taking my cock?” He chuckled before breaking into a round of laughter. The more he laughed, the more you could feel him stirring inside you, and more cream oozed and dribbled down his shaft. His presence causes your body to react with a mixture of frustration and arousal. You were even surprised that without movement, your arousal was able to escape and coat his entire length, knowing how girthy he was and him boasting about how your lips would always grip him like there was no tomorrow. But you knew he was enjoying this more than he should; purposely dragging out the situation to see your reaction.

Life felt so unfair in these moments, especially when you considered him your boyfriend and yet he teased you like this.

Still feeling a bit vengeful, you squeezed around him, half expecting a series of amused reactions from him. What you didn’t anticipate was how quickly time seemed to pass. You had just fifteen minutes before your co-worker arrived with the summaries, potentially walking in on you warming your boss’ cock. It was as if life was throwing you a curveball, and you were stuck in a strange kind of limbo.

“Mae…” you whined softly, feeling a mix of frustration and impatience. His bite on your shoulder caused you to clench around him, and finally, you received a response as he let out a hissing sound.

“Y/N…” he mimicked your tone, his voice teasing and playful. “Oh Y/N, my dear. What’s the rush? Can’t you see I’m busy?”

“Busy?! Busy doing absolutely nothing important! The chief accountant is the one responsible for reading my reports, not you. You’re just overdoing it now!” you protested with anger written all over your face as you wiggled in his lap causing his cock to become stimulated.

You weren’t sure who released the first moan, but you knew you both moaned at the sensation from your movements. His fingers dug tightly into your waist to stop your actions while he growled at your defiance. “If you haven’t noticed, you have twelve minutes before your best buddy comes walking in. I’d choose my next actions carefully—”

“Or what Mae? Do you really believe that he was being overly friendly with me?” you countered.

“Or I’d leave you here unsatisfied,” he whispered an octave lower against your earlobe. “I know when a man is being too friendly, I should know it when I see it,” he responded with haste and annoyance in his voice. A clear sign of him not being pleased with you being oblivious to something so important to him. Rocking back in the chair, he took you with him and allowed you to lean into his chest, prompting all the weight from his cock to press heavily against one side of your walls and elicit gasps from you.

Wiggling in his lap was futile were it not for his iron grip around your waist, to prevent the slightest movement. He truly wished to bask in the warmth and suffocation your cunt was giving him—drooling all over his length and massaging it with your muscles. As much as he was hissing in annoyance at your acts of defiance, the enjoyment and pleasure echoed in every sigh he released as he sank deeper into your chair. He was a vile and horrid lover; you couldn’t comprehend how you could love him when he tortured you this way—the epitome of having his cake and eating it too. “If you continue squirming, I’ll withdraw without a single touch, or I’ll bend you over this table, have my fill and depart. Or you can be a good girl and I’ll fulfil your request.”

“I hate you,” you protested and turned to catch his eyes closed with a satisfactory smile on his face.

“I know princess, but all this will be over soon, and I’ll get what I want.” His warm breath brushed against the shell of your ear before he playfully nibbled on your lobe. The arms that encircled your waist slipped beneath your dress, exerting pressure on your lower abdomen where his presence was prominent. The sensation of his bulge nestled against your core was both exhilarating and maddening, leaving your mind in a whirlwind. Sluggishly, his hands travelled south and froze as the tip of his fingers contacted your clit; a gentle pat was delivered earning a gasp from you. “Just bear with me for a few more minutes,” he cooed as his fingers began snail’s pacing against your clit, making your head spin, “good girls get rewarded.”

Masterlist

Taglist: @lilmelily @eunoiaastralwings @koyunsoncizeri @ranhanabi777 @someoneinthestars

@mysticmoomin @aconstructofamind @rain-on-my-umbrella @the-phantom-of-arda @singleteapot

@wandererindreams @asianbutnotjapanese @ilu-stripes @justellie17 @justjane @silverose365

@bunson-burner @batsyforyou

#mina_kinktober2023#silm smut#maedhros x reader#maedhros smut#maedhros imagine#maedhros scenario#maedhros#silmarillion x reader#silmarillion imagine#silmarillion fic#silmarillion scenario#middle earth x reader#middle earth imagine#middle earth smut#middle earth fic#middle earth scenario#house of feanor#feanorians#sons of feanor#nelyafinwe maitimo#russandol#x reader smut#x reader insert#silmarillion#doodlepops writings ✨

98 notes

·

View notes