#Mésangère

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 1 décembre 1799, An 8 (175): Chapeau - Capote. Schall de Casimir. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

'Chapeau-capote' with a long transparent veil with a floral pattern covering the face. A long 'casimir' scarf around the neck. Dress with long sleeves and train. Flat shoes with pointed toes. The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#18th century#1790s#1799#on this day#December 1#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#rijksmuseum#dress#shawl#veil#lace#Mésangère#cashmere

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

17th-century Château de La Mésangère in Bosguérard-de-Marcouville, Normandy region of France

French vintage postcard

#normandy#bosguérard-de-marcouville#marcouville#historic#chteau#photo#briefkaart#vintage#château de la mésangère#region#th#sepia#17th-century#photography#carte postale#postcard#postkarte#france#postal#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#french#old#ephemera#de#postkaart#msangre#century#la#bosgurard

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women artists in Napoleonic France

(Young women copying: ‘Love begging Venus to forgive Psyche’ which was displayed at the 1808 Salon. Sketch by Georges Rouget)

Quotes from an article about women’s participation in the art world during the Napoleonic era.

Article:

Heather Belnap Jensen, “The Journal des Dames et des Modes: Fashioning Women in the Arts, c. 1800-1815,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 5, no. 1 (Spring 2006) (source)

“More and more women artists began exhibiting their work in public venues and receiving recognition for their contributions at this time. While only three women artists had participated in the 1789 biennial Salon, fifty participated in the Salon of 1806–an increase in women’s participation of over 1600 percent in seventeen years.”

(Woman artist giving a drawing lesson — Self-portrait, 1810, by Louise-Adéone Drölling)

“We see a move away from the emphasis on the public sphere to the private space as motifs, intimating a valorization of a woman’s world. While history painting, which played such a crucial role in Revolutionary visual culture, remained the privileged genre at the turn of the century, the rise in portraiture, landscape, and genre painting in Napoleonic France indicates this shift in values.”

(Young Woman Drawing—Portrait of Charlotte du Val d'Ognes, 1801, by Marie-Denise Villers)

“Women’s journals, which often published art-related materials, have been largely overlooked in discussions of developments in late eighteenth-and early nineteenth-century French visual culture. This is surprising, given that bibliographies on art criticism of this period frequently cite items from these publications.”

One of the most influential women’s journal of the period was Journal des Dames et des Modes. It was created by Jean-Baptiste Sellèque and Pierre de La Mésangère in 1797 and continued until 1839.

“La Mésangère’s key collaborator during the Napoleonic period was a woman, Albertine Clément, née Hémery, a well-known figure in both journalistic and cultural circles in post-Revolutionary France, and that several women were regular contributors to this journal during this era.”

Annemarie Kleinert did a study on the journal:

“She determined that the journal targeted bourgeois women between the ages of 18 and 40 years old who could afford the annual subscription rate of 10 livres, and that the majority of subscribers during the period from 1800 to 1815 were from the provinces.”

(Portrait of a Young Woman Drawing Herself, early 1800s, by Louis-Léopold Boilly)

Interest from women in creating their own designs:

“Fashion plates that accompanied each issue of this journal gave visual testimony to this heightened interest in women’s artistic engagement. Indeed, women in fashion plates were sometimes presented in the act of sketching and drawing, as shown in a plate that appeared as an insert in an 1802 issue of the Journal des Dames et des Modes.”

The act of women creating art was compared to motherhood. In that way, women were encouraged to make art, but in terms which enforced traditional and patriarchal ideas:

“Furthermore, the vocabulary used by the author stresses the ways in which artistic creativity mirrors childbirth and elicits feelings of exaltation over one’s art that are similar to those evoked by motherhood when he writes that ‘she smiles at the objects which are born of her colors’ and calls the site of her production a ‘creative space.’”

There were opportunities for women to paint nude subjects for classical style art:

“Recent scholarship suggests that there were opportunities for such study in the Napoleonic era. By 1800, female students could attend anatomy classes given by the surgeon Sue and also by the École du Modèle Vivant at Versailles, and artist Adele Romilly reported that David, Régnault, and Guérin all provided mixed studios that offered courses on life drawing from the nude.”

One of the claims made against the women’s journals is that they were sexist. The author points out that it’s more complicated and not entirely true. The journals included laudatory reviews of paintings by female artists at the salons, biographies of women artists, such as Angelica Kauffmann, and published excerpts of pamphlets written by women, such as Angélique Mongez.

(Portrait of an Artist Drawing after the Antique, c. 1800s, Jean François Sablet)

However, the author also says there was a lot of anxiety about the increase in female participation in the art world, both as creators and as spectators. There were articles describing women at museums in derogatory terms. One in particular described a young girl being overcome by emotion at the sight of the statue of Apollo Belvedere and creating such a large scene that she had to be dragged away in tears.

These articles imply that women spectators had become dominant enough that it could inspire critics.

Women had become so important in the art world that a really unique phenomenon happened:

“Roger Bellet has demonstrated that there are known instances in late eighteenth-and early nineteenth-century France when men published under a female pseudonym.”

Many of the top artists who were admired in the era were women such as Élisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, Marguerite Gérard, Constance Mayer, Adèle Romany, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Pauline Auzou, Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet, Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Constance Marie Charpentier and many others.

#art#women’s art#women artists#napoleonic era#napoleonic#mine#fashion#writing#first french empire#napoleon bonaparte#quotes#ref#reference#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1800s#fashion history#historical fashion#history of fashion#french empire#france#history#french revolution#frev#women’s history#womens art#women in art#women painters#fashion plates

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Couch ca. 1837, Attributed to the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe, Scottish

In the early nineteenth century, designers and furniture makers embraced a revival of Classical prototypes from ancient Greek and Roman architecture and decorative arts. The sleek, curvaceous lines, and dramatic, figural mahogany veneers of this couch characterize the distinct Grecian Plain style that emerged in the 1820s to 1840s during the revival period. American cabinetmakers were highly influenced by French interpretations of Classical forms that circulated in design books and periodicals, such as Pierre de La Mésangère's Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût (1820–1831)

84 notes

·

View notes

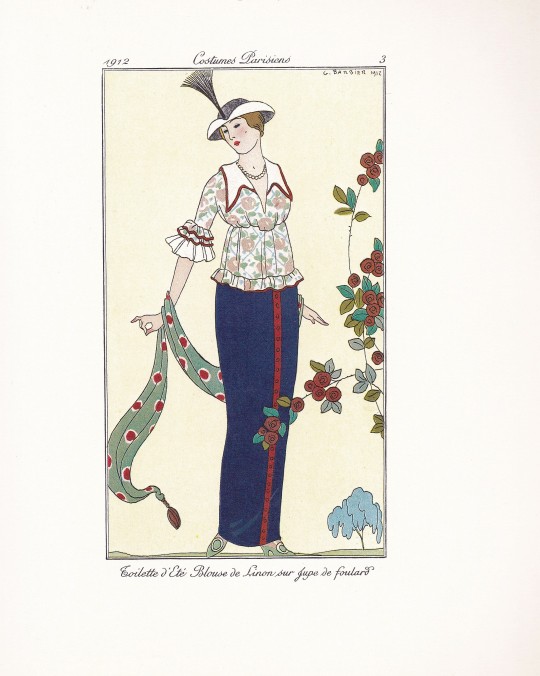

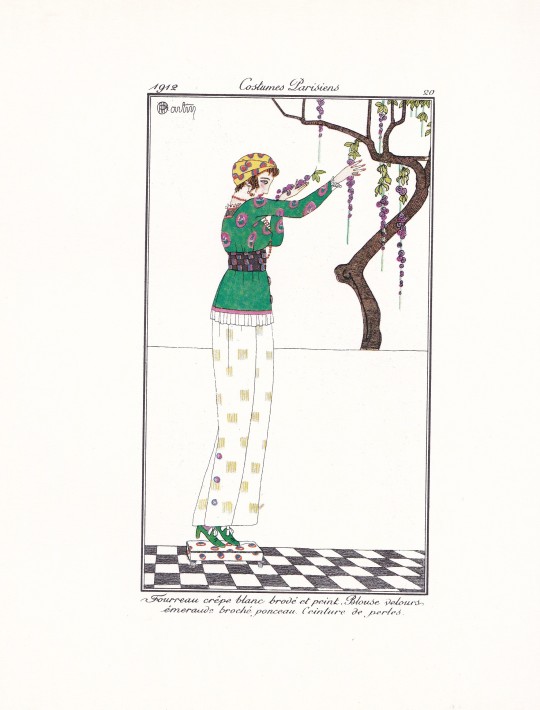

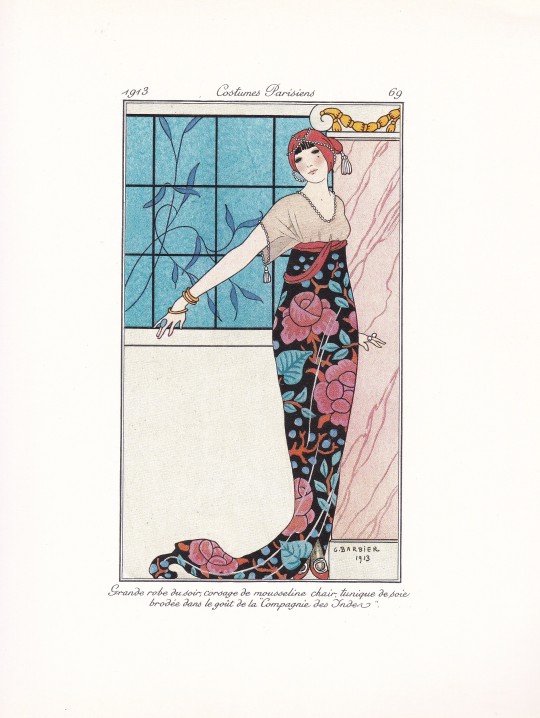

Photo

Modelli Parigini

dal “Journal des Dames et des Modes” vol.I 1912-1913

a cura di Laura Casalis, Introduzione di Cristina Nuzzi

Franco Maria Ricci, Milano 1979, 102 pagine, brossura, 23 x 25 cm.

euro 30,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Il 1912 vide la nascita, nel campo della moda, di tre importanti riviste, portavoce delle più raffinate eleganze parigine, illustrate della mano dei più dotati stilisti e illustratori del tempo. Il Journal des Dames et des Modes ebbe vita solo per tre anni, questo volume ci ripropone le più belle illustrazioni tratte dal primo biennnio questa rivista.

The "Journal des dames et des modes" was published in Paris by Vaugirard between June 1, 1912 and August 1, 1914. Inspired on an earlier journal of the same title (also known as "La Mésangère", which disappeared in 1839), the "Journal des dames et des modes" appealed to "the curious", lovers of rare editions, who valued fashion journals featuring limited editions with carefully executed fashion illustrations that could be equated to works of art. Each issue of the journal was made up of several texts, including poems, commentaries, and narrations of life in Paris, and hand-colored engravings or pochoir prints, executed in vivid colors and drawn by the leading artists of the day, including George Barbier, Antoine Vallée, Léon Bakst, and Umberto Brunelleschi. The combination of writings and illustrations was meant to be a reflection of the cultural atmosphere in Paris at the time, showcasing the best of intellectual, artistic and fashion creations.

17/12/21

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter: @fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano tumblr: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano

#Modelli Parigini#Journal des Dames et des Modes#1912-1913#George Barbier#Paul Iribe#fashion illustration#illustrazione di moda#fashion books#fashionbooksmilano

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

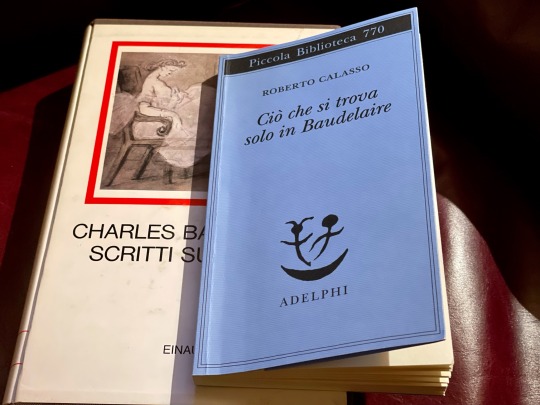

ROBERTO CALASSO: “CIÒ CHE SI TROVA SOLO IN BAUDELAIRE”

Se dovessi scegliere una forma di scrittura e di pensiero ideale, sceglierei quella che procede per illuminazioni, propria di Baudelaire. Benché necessaria, la scrittura argomentativa e deduttiva, non avrà mai la stessa potenza profetica della scrittura che procede per successive illuminazioni. Evidentemente la pensava come me anche Roberto Calasso, anche se è più opportuno dire che sono io a pensarla come lui. “Ciò che si trova solo in Baudelaire” edito, naturalmente, da Adelphi, è una sorta di breviario delle peculiarità della scrittura, della poesia, ma anche del tema caro a Charles Baudelaire, “essere naturalmente metafisico”, come lo definisce l’autore. Che si tratti dei suoi incipit speculativi, di una “correspondance”, di una lettera, di un saggio o di un sogno, Baudelaire è poco incline al ragionamento prolungato e consequenziale. Irresistibilmente attratto da “tutta la mostruosità” che avvolge l’uomo, di Victor Hugo apprezzò la sua capacità di attraversare l’intero repertorio umano ed a caratterizzare la prima parte del prezioso volumetto, è proprio la volontà di Calasso di voler evidenziare l’assoluta originalità di Baudelaire anche comparativamente con grandi e grandissimi della letteratura francese da Gautier a Saint-Beuve, da Diderot a Stendhal e appunto a Victor Hugo. Baudelaire è un a-sistematico per eccellenza e così la dottrina delle "corrispondances" è il vero nocciolo dell'interesse di Calasso e ne costituisce la struttura del piccolo e bellissimo volumetto "Adelphi" che si confà a questa esigenza di improvvise illuminazioni, potremmo dire "illuminazioni di illuminazioni"; alcune di rara bellezza, come quelle sull’artista che Baudelaire definiva "il pittore della vita moderna", ovvero l'incisore e illustratore Constantin Guys che disegnava per l’ “Illustrated London News”. Una opinione imbarazzante da sostenere nella Francia dei Salons, un paragone insostenibile per i tromboni dell’arte. In fondo Guys era “solo” un illustratore e per l’epoca questo era quasi disdicevole. Invece per Baudelaire proprio “l’assenza totale di antichità” nelle sue tavole, dà, quella che poi Aragon definì “la vertigine del moderno”. Del resto il bello, scrive Baudelaire, “È fatto di un elemento eterno, invariabile (…) e di un elemento relativo, circostanziale…” È noto che Baudelaire ha sempre manifestato per l’illustrazione un’attenzione quasi morbosa, tanto da fremere di desiderio, nella sua casa di Honfleur, nell’attesa dell’arrivo del “Journal des dames” del grande disegnatore Pierre de La Mésangère. Ma il volumetto di Calasso esplora tutte le passioni, dalle più riposte alle più palesi di Baudelaire, come per esempio la venerazione per Edgar Allan Poe e onirica e piena di fascino è la narrazione del suo desiderio di offrire la prima copia della traduzione di “Histoires extra-ordinaires” di Poe alla maîtresse di un grande bordello parigino. Un libretto-scrigno che racchiude non solo “fleurs du mal”, ma tante piccole gemme filosofiche e tante singolarità del poeta e scrittore francese. Se avete letto il sontuoso “La Folie Baudelaire” edito sempre da Adelphi, di qualche anno fa, non potete mancare questo piccolo ma indispensabile compendio all’opera di un antesignano della modernità.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recontres des petites ouvrières - Le Bon Genre, Nr. 15

Published by: Pierre La Mésangère, 1802-1812, Published in: Paris (France)

Plate 15: five ladies' maids, carrying hat boxes and baskets, meet and chat in the street.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Collection of furniture and objects of taste

A series of hand-colored engravings depicting furniture, carriages, draperies, decorative objects, jewelry, etc., issued in connection with the Journal des Dames et des Modes, edited by Pierre de la Mésangère, and published in Paris. Nos. 1-7 dated an 10, i. e. 1801 or 1802; The Bibliothèque Nationale supplies dates 1807-1831 for the series.

http://content.winterthur.org:2011/cdm/landingpage/collection/Mesangere

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût, vol. 2 by Pierre de La Mésangère, Drawings and Prints

Medium: Engraving, hand-colored

Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1930 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/381656

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 5 février 1819 (1792). Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

Standing woman with a cashmere turban with pearls on her head. She wears a 'par-dessus' of plain velvet, including a satin gown with long sleeves, trimmed with blonde (bobbin lace). Further accessories: earrings, two-strand necklace, fan, flat shoes with bows. Proof of a print from the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1810s#1819#on this day#February 5#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#proof#description#rijksmuseum#dress#Mésangère

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

17th-century Château de la Mésangère in Bosguérard de Marcouville, Normandy region of France

French vintage postcard

#normandy#marcouville#historic#chteau#photo#briefkaart#vintage#château de la mésangère#region#th#sepia#17th-century#photography#carte postale#postcard#postkarte#france#postal#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#french#old#ephemera#de#postkaart#msangre#century#la#bosgurard#bosguérard de marcouville

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

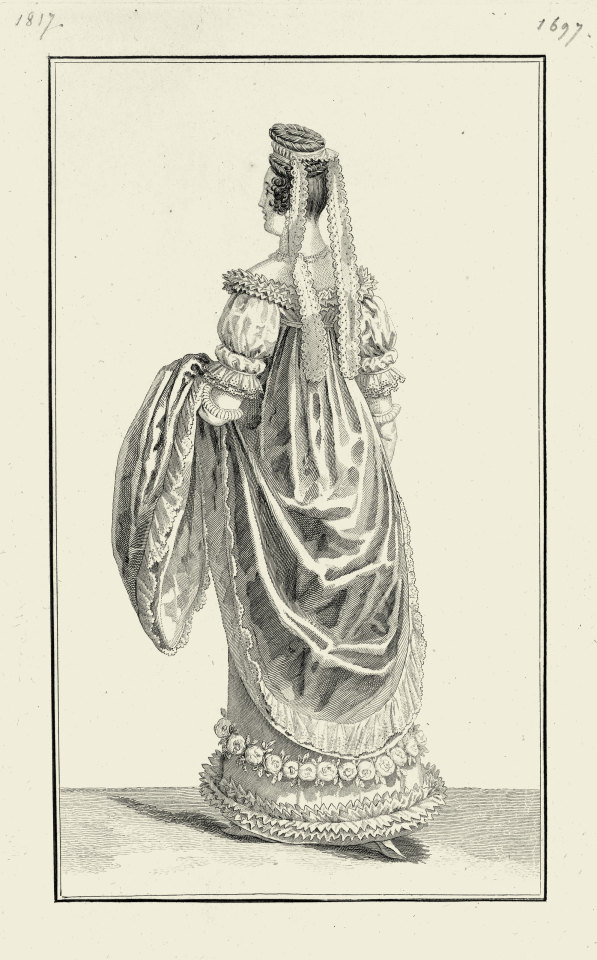

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 15 décembre 1817 (1697). Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

Woman, seen from the back, walking to the left, dressed in a court ensemble. She wears a dress with a high waist and train. The underskirt is decorated with a garland of flowers. The hair in a high bun and a headband with two hanging slips. Further accessories: necklace, gloves, shoes. She holds up her dress with her left hand. Proof of a print from the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1810s#1817#on this day#December 15#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#proof#description#rijksmuseum#dress#train#Mésangère

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costumes Parisiens, 25 juin 1828 (marked 24 juin 1828 in a note by the publisher), (2609): Chapeau de paille de riz du Magasin de Mme Millet, Boulevart Italien, No. 20. Robe de foulard. Pélerine de tulle à quadrilles appliqués. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

Paille de riz hat from Millet's shop. Foulard gown. Pelerine of tulle with 'quadrilles appliqués' (diamonds). Further accessories: gloves, lorgnette, handkerchief, flat shoes with straps. The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1820s#1828#on this day#June 24#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#rijksmuseum#dress#Mésangère#pelerine#gigot

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, editie Frankfurt 21 octobre 1821, Costume Parisien (43): Chapeau de satin moiré, orné d´une écharpe de gaze formant cocarde. spencer de velours. Robe de perkale, garnie en mousseline brodée et jours de tulle. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

The caption and accompanying text (p. 464) state: Hat of satin moiré, decorated with a gauze sash in the shape of a cockade. Spencer made of velvet. Cotton batiste dress, trimmed with embroidered muslin and openwork tulle. White gloves. Black shoes. The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published in Frankfurt as a copy of the French edition by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1820s#1821#on this day#October 21#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#rijksmuseum#dress#spencer#shawl#Mésangère

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 15 octobre 1819, (1851): Chapeau de crêpe et liserés de satin. Spencer à Schall, en gros d'été. Robe de perkale, garnie de bouillons de mousseline. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

Standing woman dressed in a spencer 'à Schall' (shawl collar) of 'gros d'été. Dress made of cotton batiste (percale), topped with muslin 'stocks'. On the head a hat of crepe and satin trim. Bag (reticle) in the right hand. The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1810s#1819#on this day#October 15#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#rijksmuseum#dress#bonnet#spencer#Mésangère

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 15 décembre 1819, (1865): Turban de velours plein. Robe de crêpon à la sévigné, agrafée derrière et à baleines perpendiculaires. Garnitures bordées en satin. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

Woman, seen from the back, wearing a dress made of 'crêpon à la sévigne', fastening at the back and with 'baleines perpendiculars'. Trims embroidered with satin. On the head a turban of plain velvet. Further accessories: necklace, fan, scarf, shoes. The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1810s#1819#on this day#December 15#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#rijksmuseum#dress#shawl#bow#Mésangère

56 notes

·

View notes