#Invertebrates of North America

Text

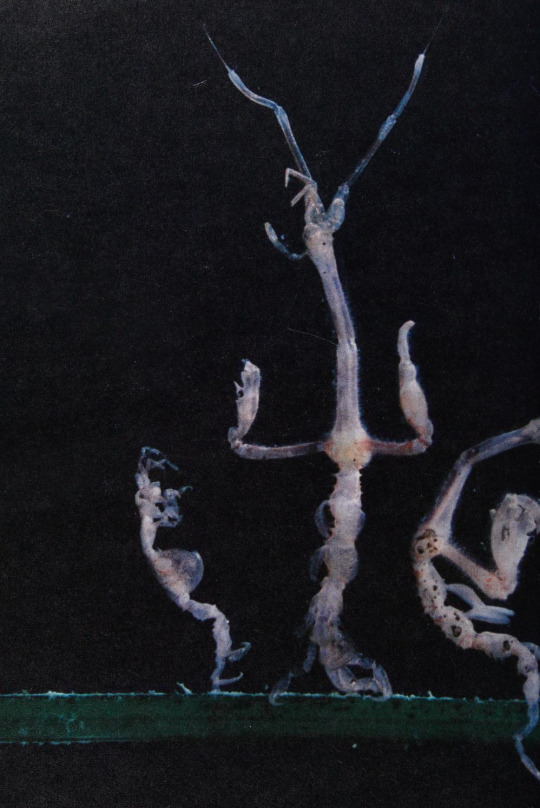

Skeleton shrimps (Caprella sp.)

By: Western Marine Laboratory

From: Invertebrates of North America

1972

#skeleton shrimp#shrimp#crustacean#arthropod#invertebrate#1972#1970s#Western Marine Laboratory#Invertebrates of North America

475 notes

·

View notes

Text

I remember as a kid in the 80s that these iconic large butterflies were everywhere in our garden, along with swallowtails of several species. It's been so disheartening to see an insect that was so plentiful be on the brink of extinction just a few decades later.

Individually we can only do so much about the effects of anthropogenic climate change, but here are a few things you can do to help monarch butterflies if you're in their range:

--No pesticides! These chemicals don't discriminate, and will harm all sorts of insects, not just the intended targets. In fact, the fewer yard chemicals you use, the better for your local ecosystem.

--Plant milkweed that is native to your area; even a few plants in pots count! Live Monarch (US), Monarch Watch (US), and Little Wings (Canada) all have free native milkweed seeds on a limited basis--and they appreciate donations of funds to help pay for more, too. Be aware that a lot of the milkweed on the general market consists of non-native tropical species that host parasites and also bloom late enough that they may cause monarchs to stop migrating south to overwintering grounds.

--Put out a watering station consisting of a shallow dish with a layer of rocks on the bottom and just enough water to not quite cover them so the butterflies can land and safely drink water without falling in.

--Support organizations like the ones mentioned above, and the Xerces Society of Invertebrate Conservation, which all help to protect monarch butterflies and other invertebrates.

#monarch butterflies#Danaus plexippus#butterflies#insects#invertebrates#invertblr#arthropods#endangered species#North America#extinction#environment#environmentalism#conservation#ecology

162 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Another Day, Another Pacific Sand Dollar

The eccentric sand dollar, aka the sea-cake, biscuit-urchin, western sand dollar, or Pacific sand dollar (Dendraster excentricus), are found in the intertidal zone and near-shore sandy bottoms from Alaska, US to Baja California, Mexico.They are the only sand dollars endemic to the Pacific Northwest, though they share the rest of their range with other species. Live individuals are seen either partially buried upright or lying flat on the ocean floor, depending on the strength of the current. To prevent themselves from being swept away, juveniles will also ingest sand to weigh themselves down. Although they are not social, they can form large colonies with as many as 6 sand dollars in a square m (1 sq yd).

Pacific sand dollars are named for their resemblance to silver dollars, especially the bleached exoskeletons that commonly wash up on beaches. Most adults average about 8 cm (3 in) across, though individuals as big as 10 cm (4 in) have been found. The body is a flat disc coated in small, purple tube-like feet and sensory organelles called cilia. The feet are used both for moving across the ocean floor and for pulling oxygen from the water. The mouth and anus-- a single opening-- are located on the sand dollar’s underside. Inside the mouth are five teeth and jaw plates known as doves; together they form a structure known as Aristotle’s lantern, which is unique to echinoderms like sand dollars and sea stars.

D. excentricus is a suspension feeder, using its feet and cilia to pull food from the water or direct it along special groves on the body’s underside. Their main prey are microscopic larvae, copepods, diatoms, algae, plankton, and detritus. The sea-cake is predated upon by a number of sea stars and fish, as well as crabs and sea gulls. To avoid being eaten, adults bury themselves in the sand and larvae will duplicate themselves via a process known as budding and fission, which creates smaller individuals that can distract potential predators.

Although western sand dollars have seperate sexes, they are broadcast spawners. In late spring or early summer, males and females congregate and release gametes into the water where they become fertilized. Larvae, also known as prisms, hatch just a day later. This larvae floats freely through the water, growing arms and metamorphosing into a echinopluteus larva. Once they reach 8 arms, the larva begins to develop an exoskeleton or echinus, and resembles a small adult. The final stage of growth is triggered by chemical cues released by other adults; after this, individuals become sexually mature and settle on the ocean with other sand dollars. In the wild, adults can live up to 13 years.

Conservation status: Although the IUCN has not evaluated the Pacific sand dollar, they are regularly threatened by ocean acidification, warming, and bottom trawling.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Chan Siuman

Brian Starzomski

Alison J. Gong

#pacific sand dollar#Clypeasteroida#Dendrasteridae#sand dollars#echinoderms#invertebrates#marine fauna#marine invertebrates#benthic fauna#benthic invertebrates#intertidal zone#intertidal invertebrates#coasts#coastal invertebrates#Pacific Ocean#North America#western north america

374 notes

·

View notes

Text

North Pacific humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae kuzira

with rabbit-ear barnacle Conchoderma auritum

Observed by tbell_08, CC BY-NC

#Megaptera novaeangliae kuzira#North Pacific humpback whale#Cetacea#Balaenopteridae#cetacean#whale#non-ungulate#invertebrate#crustacean#Conchoderma auritum#rabbit-ear barnacle#North America#United States#Alaska#Pacific Ocean#Chatham Strait

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

#book blog#bug field guide#bug book#bugs#insects#invertebrates#arthropods#field guide#field guide to insects of north america

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

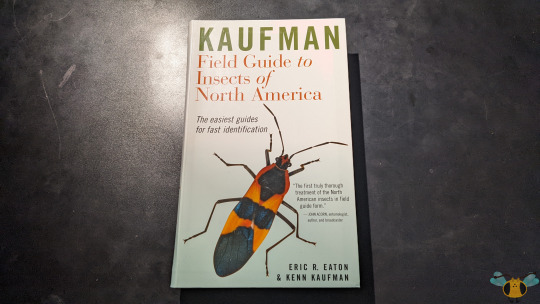

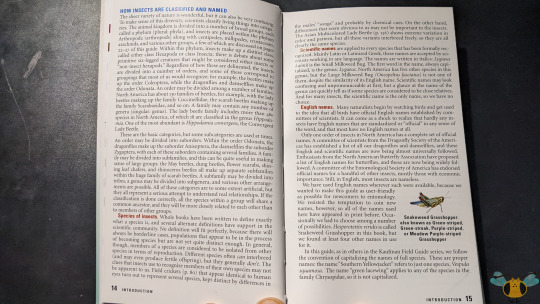

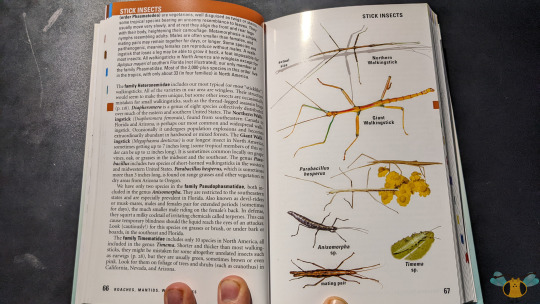

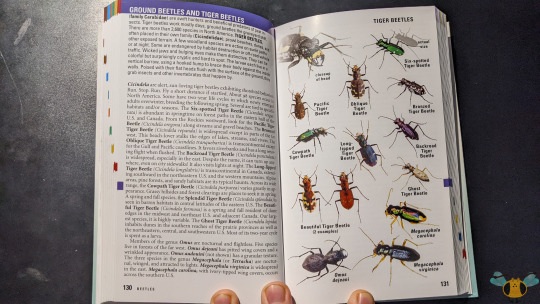

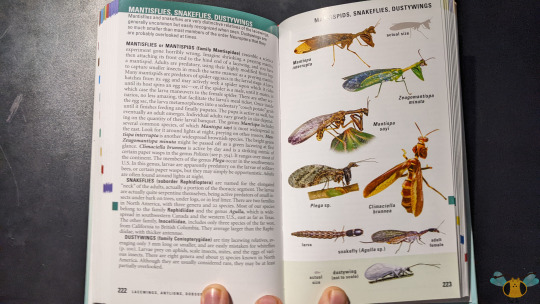

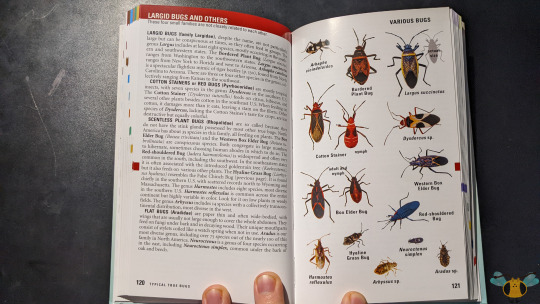

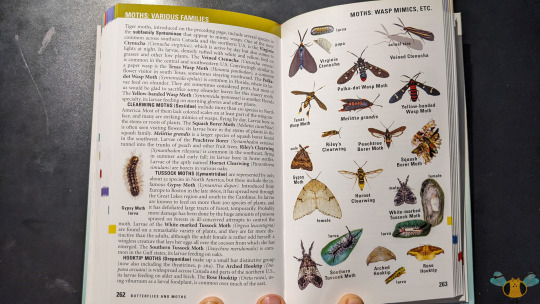

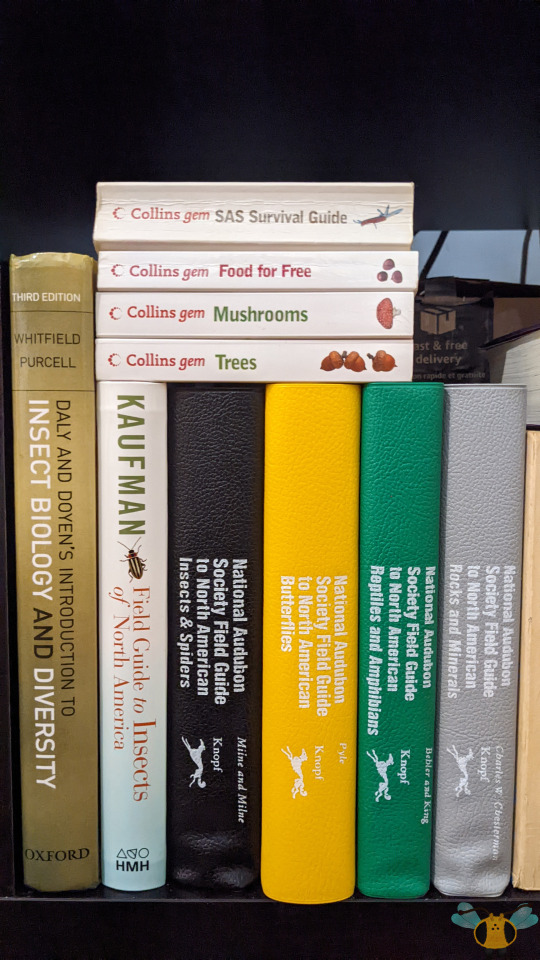

Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America, by Eric R. Eaton and Kenn Kaufman

I’ve added a new field guide to my growing collection of insect identification resources. This book was recommended to me after I picked up the Audubon Butterfly guide, and I have to say, I quite enjoy this book and it will be accompanying me on outdoor daylong bug hunts alongside the Audubon books. If you’re looking for something a bit more general, perhaps as an entry resource to help you catalogue and identify insects as a hobby, this book is a great starting point. The format of the book is mostly consistent with Pictures 4-8: key information on the left side of the book and pictures of insects on the right. The information is simple to understand and very articulate, highlighting crucial information that can help you sort insects into their different orders and families. For example, in the Beetle section, there are separate pages that would highlight the key characteristics that make each insect special which in turn allows a simple identification for each Beetle such as what makes a Leaf Beetle and a Longhorn Beetle. Many prominent species are highlighted in the field guide, but mostly those living in Canada and the USA. Of course, the guide can’t cover every insect specie, but the descriptions given are to the point you may recognize some of the more common species included. For something more technical, you many have to turn to another guide or consult an internet resource.

The insect imagery in the book is quite good, really aiding the text descriptions. I give many thanks to the contributing photographers of this guide and I wish that there were sections that would showcase larger insect pictures and diagrams. It would definitely help with the author’s goal of “naked eye identification” and to highlight some of the more rare insects, insects that look similar to other insects, and insects that (while presumed common) aren’t part of common knowledge. It’s for this reason that I highlight Picture 6 which documents Mantidflies (Mantispids). These are not Mantids or Flies and they can resemble Wasps, but they are in fact Neuropterans! It’s not something everyone would know and thus I think it should receive a bit more attention. A little bit of information can make the difference between knowing which insects to avoid and which look fearsome but are harmless, just like the Mantidflies. As well, finally a visualization of Snakeflies on this blog! Finally, what I enjoyed most about this field guide was the passion and love for insects on display in the writing. The people who wrote and contributed to this book clearly love these creatures and want to share with others why insects are important, what we can learn from them and how they impact Earth and our lives. All this is presented in a way that (aside from a few scientific or technical terms) is easily digestible and readily applicable.

To all those looking to create a hobby based on insects, learn the basics of insect identification or if you have a real passion for insects, I do recommend this book. I’ll be using it where I can, and until then it will stay with the other books I reference lined up on the bookshelf. To conclude, there are sections in the book on Arachnids and non-insect hexapods which I also appreciate, if only to highlight the difference between them and insects.

For additional insect literature, you may visit the Blog Resources page.

#jonny’s insect catalogue#insect field guide#kaufman field guide to insects of north america#field guide to insects of north america#north america insect guide#field guide#insect identification guide#amateur insect guide#insect pictures#insect facts#insect identification#entomology#invertebrates

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

the american woodcock is a member of the shorebird family (scolopacidae) that inhabits the eastern portion of north america. beloved as both a prized gamebird and considered a symbol of spring due to their elegant courtship flights during the breeding season, the american woodcock is known by many unusual names, including ‘timberdoodle’ and ‘bogsucker’. the males of this species are known for unique bobbing courtship dances along with flight displays during the breeding season. the sexes appear similar as far as coloration, but females are notably larger. this species feeds primarily on earthworms, but will also probe the dirt with their long bills for other invertebrates, such as centipedes. despite being a member of the shorebird family, they primarily inhabit young forests or brushy habitats where they are easily camouflaged.

#American woodcock#woodcock#timberdoodle#bogsucker#bird#birblr#thanks for the kofi tip!!#i loved looking at pics of this guy lol

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

What is our ecological responsibility when encountering an invasive animal species?

that depends on what that species is, and im struggling to come up with any catch-all response to that. there are a lot types of animals.

some stuff is way beyond our control, like the invasion of earthworms into North America and many other invertebrate species—it would be just as much of a waste of effort trying to kill all the spotted lanternflies as it would be to dig up every worm in the forest.

for stuff like fish, cats, and hogs… I really don’t know. this isn’t my area of expertise but I do think invasive mammals are at least a little easier to exclude/control/manage through hunting and trapping than minute flying or soil borne invertebrates (maybe not the hogs. they sound unstoppable). also people tend to get very stupid when it concerns charismatic or domesticated megafauna, even if vulnerable native ecology is at stake.

in all cases, prevention is most important: don’t let pets loose, make note of unfamiliar insects or help to track the spread of establishing species.

I also think it is important to not demonize or abuse the invasive animals regardless of what we need to do to control them. they’re not evil, they’re just trying to survive—torturing them doesn’t accomplish anything. so even if cane toads and cats and horses *AND pythons and fish and other uncharismatic animals* have to be killed to protect native ecosystems, we ought to find ways to do that that both have the intended effect and don’t cause unnecessary harm.

also, please no “humans are the invasive species” thing. I will hit you with my ecologist stick

348 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet the Monterey ensatina (Ensatina eschscholtzii)! Growing up to 6 in (15.2 cm) long, this amphibian uses its long tongue to snatch worms, beetles, snails, and other invertebrates. Though it has no lungs, it can make a faint squeaking sound when threatened. It also has the ability to secrete an unappetizing, sticky, milky-white substance onto its tail. When pursued, this species will wave its mucous coated-tail at a foe to deter them from getting any closer. If that fails, it can drop this appendage as a last-ditch effort to distract predators, and can eventually regrow it. This critter can be found in parts of North America’s Pacific Coast including Canada, the United States, and Mexico, where it inhabits cool, moist spaces.

Photo: mhedin, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, iNaturalist

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some 20 hammerhead flatworms have been spotted in Westmount. The invasive species from Asia secretes a dangerous paralyzing toxin and is increasingly present in North America.

Lisa Osterland, a retired teacher, discovered about 20 hammerhead flatworms (bipalium) in her garden in Westmount, a municipality on the Island of Montreal.

Earlier this week, while removing slugs that were eating the flowers in her garden, she noticed a type of invertebrate she had never seen before.

[...]

Their proliferation is a cause for concern, not least because this worm secretes a paralyzing toxin, tetrodotoxin.

"It's one of the most powerful molecules in the biological world, the same molecule that is produced by puffer-fish," Normandin said.

"If a young child puts soil in his mouth and ingests a flatworm or two or more, there's a real risk of damage. If ingested, it's a toxin that will first attack the perioral region — the face, the tongue and everything in the esophagus," and "in such a case, the child needs to be hospitalized very quickly," the expert added.

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada

520 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any cool facts about Missouri wildlife?

I'd love to share something with my Midwestern friends, and thank you for always updating this blog!

I don't know if i have any Missouri animal facts per se... but I can share some of the state symbols with everyone.

We moved around a lot when we first came to the U.S. and we lived briefly in Kansas City. I have great memories of going to the Ozarks at Christmas time (near Lake of the Ozarks). I specifically remember following woodpeckers and deer around the forest in the snow.

SOME MISSOURI STATE SYMBOLS:

STATE BIRD: Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis), family Turdidae, order Passeriformes, found across much of the central and Eastern U.S., SE Canada, and NW Mexico

Changes in land use lead to drastic declines in Eastern Bluebirds after the early 1900s. They have recovered in many places, due to "bluebird trails", reestablishing appropriate habitat and nest box campaigns for public and private property.

Find out more: NestWatch | Eastern Bluebird - NestWatch

Blue birds are in the thrush family, Turdidae, along with American Robins.

They eat mainly worms, insects, and other small invertebrates (but also take berries for part of the year).

Bluebirds are cavity nesters, nesting in tree holes usually, but will readily take to properly constructed and placed nest boxes.

Males (pictured) are brighter blue, and females are a more muted and faded blue or bluish gray.

photograph by Keith Kennedy

STATE AQUATIC ANIMAL: American Paddlefish (Polyodon spathula), family Polyodontidae, order Acipenseriformes, found in various parts of the Mississippi River basin

This species is the only member of this family that still exists. They are most closely related to sturgeons. This order, Acipenseriformes, is considered one of the most evolutionarily primitive groups of ray finned fishes.

They do not have scales, and their skeleton is mostly cartilaginous.

They are filter feeders. Their heads and rostrums are covered with thousands of sensory receptors, which help them locate zooplankton swarms.

They are considered "vulnerable" due to overfishing, habitat degradation and destruction, and pollution.

photograph via: US Fish & Wildlife Service

STATE ENDANGERED ANIMAL: Eastern Hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis), family Cryptobranchidae, eastern United States

The largest salamander in the Americas, it grows to a total maximum length of up to 40 cm (15.7 in).

Though nationally it is considered to be just "vulnerable", in some states (like Missouri), it is "endangered".

photograph by Mark Tegges

STATE REPTILE: Three-toed Box Turtle (Terrapene triunguis), family Emydidae, found in the South-central and Southeastern U.S.

This specie shas been considered to be a subspecies of the Eastern Box Turtle, T. carolina (and still is by some herpetologists).

These turtles are terrestrial, but are not closely related to tortoises. They are in the same family as aquatic sliders, pond turtles, cooters, map turtles, and painted turtles.

photograph by Noppadol Paothong

STATE FISH: Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), family Ictaluridae, order Siluriformes, found in freshwater habitats in the eastern and southern US, southern Canada, and northern Mexico

They are widely caught, and have been introduced into waterways in other parts of North America and around the world. (In some places they are considered an invasive species).

photograph via: Missouri Dept. of Conservation

photograph by Brian.gratwicke

#Acipenseriformes#paddlefish#fish#ichthyology#box turtle turtle reptile#herpetology#bluebird#thrush#bird#ornithology#north america#hellbender#salamander#amphibian#animals#nature#catfish

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlantic horseshoe crab encrusted with acorn barnacles. The barnacles will be shed next time the horseshoe crab molts

By: Fritz Goro

From: Invertebrates of North America

1972

#captivity#horseshoe crab#arachnid#arthropod#invertebrate#barnacle#crustacean#1972#1970s#Fritz Goro#Invertebrates of North America

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

This species only arrived in North America nine years ago, but it has already spread to over a dozen states in the US (particularly in the Northeast) and is spreading beyond that. These flies--especially in their nymph form--can be incredibly destructive to plant life here, including various fruit trees, soybeans, and other crops, as well as several species of native tree. Their primary predator, a parasitic wasp, does not exist here, and none of our native wasps have yet been seen to use this species as a host.

People in all US States, as well as Canada and Mexico, should keep their eyes out for the nymphs and adults, as well as the egg clusters, and are encouraged to smash them with impunity. We've seen how much damage other invasive species can do to both natural and cultivated spaces, and while it's unlikely we can completely eliminate them, we can at least curb them.

ID info and other relevant stuff about spotted lanternflies can be found here.

#spotted lanternfly#insects#invasive species#North America#United States#bugs#invertebrates#gardening#farming#agriculture#ecology#nature#wildlife

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Stupendous Alligator Snapping Turtle

Alligator snapping turtles (Macrochelys temminkii) are one of three recognised species of snapping turtle, all of which are found in North America. This particular species is found in the southeastern United States and the Mississippi Basin in particular. Macrochelys temminkii prefers deep freshwater, and is especially common in deep rivers, wetlands, and lakes.

The alligator snapping turtle is the largest freshwater turtle in North America, and is one of the heaviest in the world. Most individuals weigh between 70-80 kg (154-176 lbs), and are about 79-101 cm (31-39 in) long. However, the largest verified indiviual weighed over 113 kg (249 lb), and many others have been recorded in excess of 100 kg. The species is easily identifiable by its large, boxy head and thick shell with three rows of raised spikes. Typical alligator snapping urtles are solid black, brown, or olive green, though the shells of many older individuals can be covered in green algae.

M. temminkii is famous for its strong bite, which is most often utilised when feeding. The turtle's tongue resembles a worm, and at night individuals lie on the bottom of the river or lake bed with their mouths open. Fish are enticed by the bait-tongue, and when they get close enough the alligator snapping turtle's mouth clamps down around them. In addition to fish, this species may also feed on amphibians, invertebrates, small mammals, water birds, other turtles, and even juvenile alligators where their territories overlap. The alligator snapping turtle's relies on ambush techniques, and so hunters can remain submerged for up to 40 minutes. In some cases, individuals can also 'taste' the water to detect neaby mud and musk turtles. Because of this species' thick shell and ferocious bite, adults have few predators, but eggs and hatchlings may fall prey to raccoons, predatory fish, and large birds.

This species spends most of its time in the water, only emerging to nest or find a new home if their current habitat becomes unsuitable. Mating occurs between Februrary and May, starting later in the northern regions of the species' range. Males and females seek each other out, but generally don't travel great distances. About two months after mating, females dig a nest near a body of water and deposit between 10-50 eggs. Incubation takes up to 140 days, and the average temperature of the nest determines the sex of the hatchings; the hotter it is, the more males are produced. In the fall, hatchings emerge and are left to fend for themselves. Sexual maturity is reached at between 11 and 13 years of age, and individuals can live as old as 45 years in the wild.

Conservation status: The alligator snapping turtle is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN. The species is threatened by overharvesting for meat and for the pet trade, and by habitat destruction.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Ed Godfrey

Cindy Hayes

Eva Kwiatek

Nathan Patee

#alligator snapping turtle#Testudines#Chelydridae#snapping turtles#freshwater turtles#reptiles#freshwater fauna#freshwater reptiles#lakes#lake reptiles#wetlands#wetland reptiles#rivers#river reptiles#north america#southern north america#animal facts#biology#zoology

455 notes

·

View notes

Text

White Sturgeon

Acipenser transmontanus is a North American Species of sturgeon commonly known as white sturgeon. White sturgeon grow around 6 feet long on average. They can be found along the western coasts, estuaries, and river systems of North America, ranging as far south as Baja California and as far north as the Aleutian Islands. Groups of white sturgeon from different river systems exist in pockets of relatively steadfast isolation from each other. They are so isolated, in fact, that white sturgeon in different river systems and estuaries have evolved different numbers of chromosomes. Small white sturgeon mostly eat invertebrates, but larger adults consume fish as well. These fish used to be one of the staple food sources of the local indigenous populations, but their populations were greatly threatened by commercial fishing for meat and caviar in the early 1900s. Today, the white sturgeon is listed on the IUCN Red List as vulnerable.

[on a personal note: sorry for the lack of sturgeon facts lately, I have been very very depressed. I am going to be partially hospitalized for two weeks starting tomorrow, so hopefully that will get me back on track and I’ll have the energy to write about my favorite creatures again]

#sturgeon fish#sturgeon#fish#ichthyology#marine biology#acipenseridae#fish facts#sturgeon facts#white sturgeon#acipenser transmontanus

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

What can I even say? Both are incredible little guys. Very beautiful, very powerful. May the best bird win! (Though really, all birds are best birds.)

American woodcocks live in the forests of eastern North America, excellently camouflaged against the brush. They have many colloquial names, including the timberdoodle, the bogsucker, the hokumpoke, and the Labrador twister. They are crepuscular and forage for earthworms and other invertebrates where soil is moist by probing the soil with their bills. They will also rock their bodies back and forth, which provokes underground worms into moving around and thus becoming easier to detect. Males display for females by performing a complex spiraling flight.

Little auks, or dovekies, live in the North Atlantic, breeding in the Arctic and wintering slightly further south. They forage underwater for crustaceans, primarily copepods, usually in the open ocean but closer to shore during nesting. They nest in large colonies on coastal cliffsides, laying a single egg in a rocky crevice.

128 notes

·

View notes