#Egyptian jewelry

Text

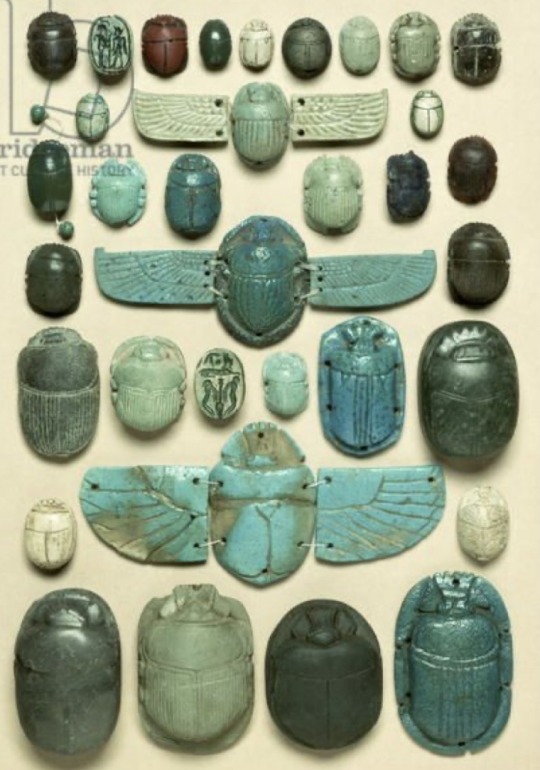

#ancient egypt#cleopatra#egypt#egyptian#egyptian aesthetic#egyptian antiquities#egyptian art#egyptian royalty#eqyptian architecture#queen of egypt#cleopatra makeup#cleopatra worship#cleopatra aesthetic#egyptian scarab#egyptian pharaoh#egyptian cats#egyptian statue#egyptian jewelry#egyptian cat#egyptian pyramids#ancient egyptian#scarab#khepera jewelry#khepera#turquoise#turquoise scarab#turquoise khepera#Egyptian beetle

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egyptian

Cuff Bracelets Decorated with Cats

New Kingdom, ca. 1479-1425 B.C.E.

#egyptian art#Egyptian jewelry#ancient egyptian#ancient egypt#ancient art#ancient jewelry#ancient people#egyptian history#egyptian culture#egyptian cat#cat aesthetic#catblr#beautiful cats#cats in art#cat art#cat jewelry#aesthetic#beauty#jewelry#ancient civilizations#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr#egyptology

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pectoral and Necklace of Sithathoryunet with the Name of Senwosret II, Middle Kingdomca. 1887–1878 B.C.

„Hieroglyphic signs make up the design, and the whole may be read:

The god of the rising sun grants life and dominion over all that the sun encircles for one million one hundred thousand years [i.e., eternity] to King Khakheperre [Senwosret II].”

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

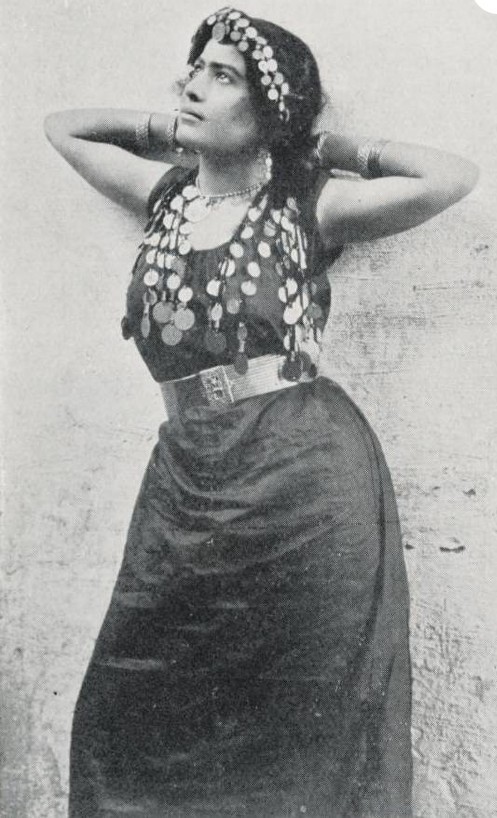

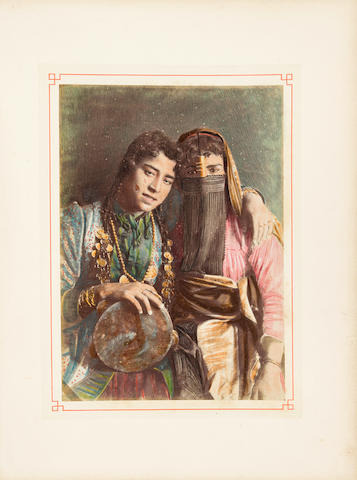

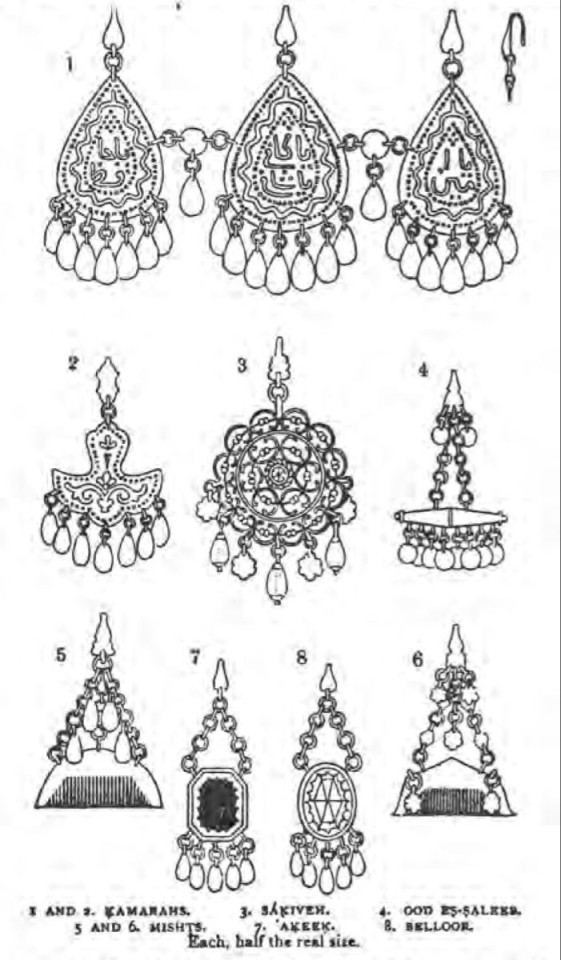

Ṣafa; Egyptian Women with coins in their hair

This style is attested in Edward William Lane's work from the 1830s. He describes it as follows:

The hair, except over the forehead and temples, is divided into numerous braids or plaits, generally from eleven to twenty-five in number, but always of an uneven number: these hang down the back. To each braid of hair are usually added three black silk cords, with little omaments of gold, &c., attached to them. For a description of these, which are called "ṣafa," I refer to the Appendix. Over the forehead, the hair is cut rather short; but two full locks (called "maḳàṣees"; singular "maḳṣooṣ") hang down on each side of the face: these are often curled in ringlets and sometimes plaited. (Egyptian women swear by the side-lock (as men do by the beard), generally holding it when they utter the oath, "Wa-ḥayát maḳṣooṣee!") [Page 45-46]

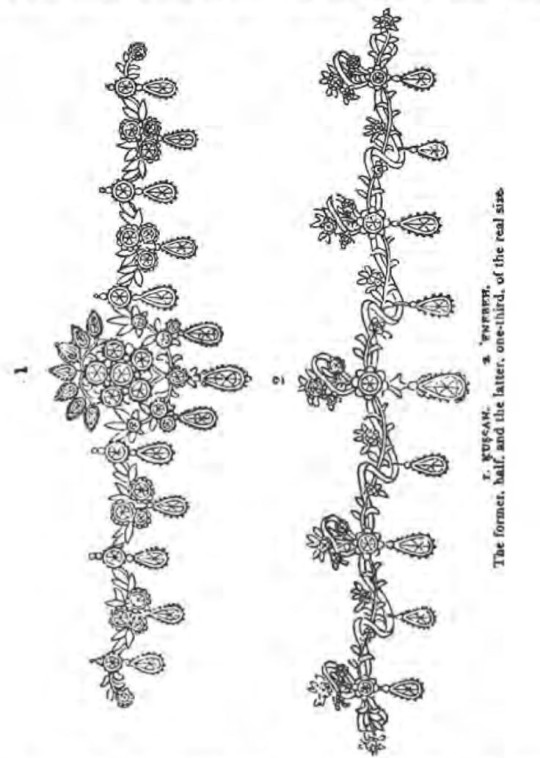

Further detail comes from an appendix focusing on jewelry:

It has been mentioned that all the hair of the head, except a little over the forehead and temples, is arranged in plaits, or braids, which hang down the back. These plaits are generally from eleven to twenty-five in number; but always of an uneven number: eleven is considered a scanty number: thirteen and fifteen are more common. Three times the number of black silk strings (three to each plait of hair, and each three united at the top), from sixteen to eighteen inches in length, are braided with the hair for about a quarter of their length; or they are attached to a lace or band of black silk which is bound round the head, and in this case hang entirely separate from the plaits of hair, which they almost conceal. These strings are called "ḳeyṭáns" and together with certain ornaments of gold, &c., the more common of which are here represented, compose what is tenned the "ṣafa". Along each string, except from the upper extremity to about a quarter or (at most) a third of its length are generally attached nine or more of the little flat ornaments of gold called "barḳ." These are commonly all of the same form, and about an inch, or a little more, apart; but those of each string are purposely placed so as not exactly to correspond with those of the others. The most usual forms of barḳ are Nos. 1 and 2 of the specimens given above. At the end of each string is a small gold tube, called "másoorah," about: three-eighths of an inch long, or a kind of gold bead in the form of a cube with a portion cut off from each angle, called "ḥabbeh." Beneath the másoorah or ḥabbeh is a little ring, to which is most commonly suspended a Turkish gold coin called "Ruba Fenduḳlee," equivalent to nearly 1s. 8d. of our money, and a little more than half an inch in diameter. Such is the most general description of ṣafa ; but there are more genteel kinds, in which the ḥabbeh is usually preferred to the másoorah, and instead of the Ruba Fenduḳlee is a flat ornament of gold, called, from its form, "kummetrè," or "pear." There are also other and more approved substitutes for the gold coin; the most usual of which is called "shiftisheh," composed of open gold work, with a pearl in the centre. Some ladies substitute a little tassel of pearls for the gold coin; or suspend alternately pearls and emeralds to the bottom of the triple strings; and attach a pearl with each of the barḳ. The ṣafa thus composed with pearls is called "ṣafa loolee.'' Coral beads are also sometimes attached in the same manner as the pearls. From what has been said above, it appears that a moderate ṣafa of thirteen plaits will consist of 39 strings, 351 barḳ, 39 másoorahs or ḥabbehs, and 39 gold coins or other ornaments; and that a ṣafa of twenty-five plaits, with twelve barḳ to each string, will contain no fewer than 900 barḳ, and seventy-five of each of the other appendages. The ṣafa appears to me the prettiest, as well as the most singular, of all the ornaments worn by the ladies of Egypt. The glittering of the barḳ, &c., and their chinking together as the wearer walks, have a peculiarly lively effect. [Page 572-574]

He goes onto describe a similar style worn by poorer women, but I probably will do its own post because it was still being worn in the Western Oases near the 1970s, and really doesn't use coins or barḳ.

This hairstyle initally was also worn with a particular headdress of upper and middle class Egyptian women, called a rabṭah, which is essentially a woman's turban. It is made with a tarboosh or ṭáḳeeyeh (I think Lane might mean taqiyah) as the base, with muslin printed or painted scarves called faroodeeyeh, or crepe scarves wrapped around it in a high, flat pattern. Over the tarboosh was stitched down an ornament called a ḳurṣ, made of metal and often gems, and distinguished by material- generally wether it was made of diamonds (ḳurṣ almás) or of gold (ḳurṣ dahab), with the latter often having an emerald or ruby cabochon in the center. A ḳuṣṣah/'enebeh (items similar to the Algerian khit errouh) or shawáṭeḥ (worn in the same manner, but made of pearl strands or netted beading with an emerald in the center) may also be attached, as well as many other small pendants and pins. It sometimes also had silver or gilt spangles attached to the front, in which case the rabṭah was made of rose or black muslin or crepe.

As can be seen from the sharper photos of bare headed women, the braids themselves start a few inches away from the scalp, not directly at it, probably owing to the texture of most of these women's hair.

While initally as Lane describes, this was a hairstyle for the middle and upper class, as those classes began to look increasingly at European fashions under the Khedivate and British Occupation, the hairstyle mainly continued use among the poor, dancers, and some Beoduins.

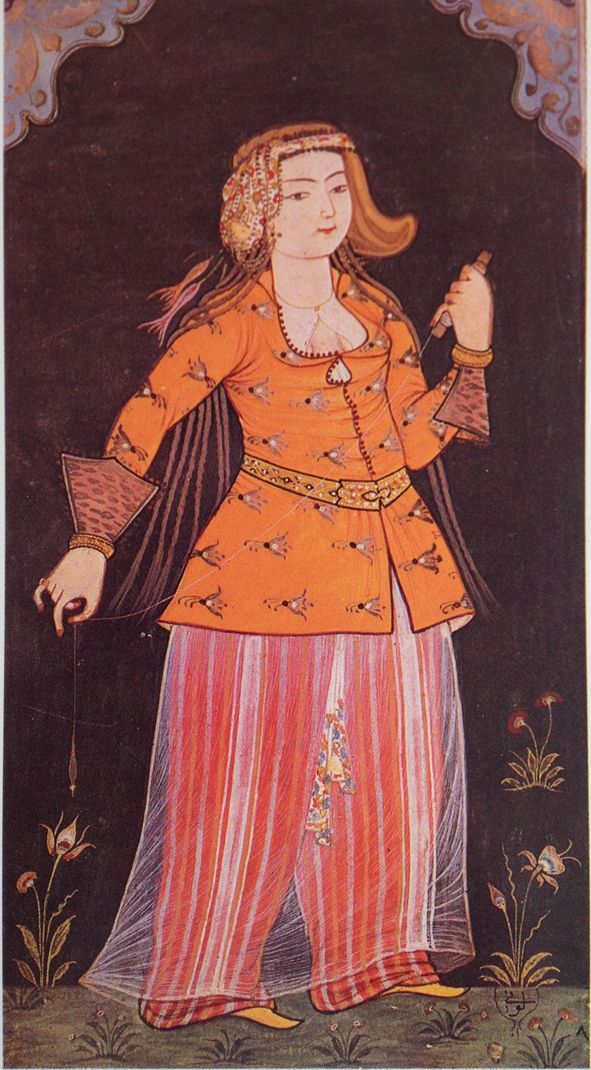

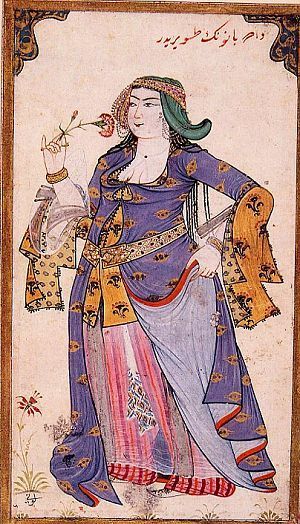

This style of many braids with bangs and often a turban over top is potentially rather old in Ottoman Turkish art, with examples appearing from the 17th century- though they are unfortunately unclear, as they could also be stylized tendrils of hair, and in some cases, clearly are such.

Similar styles of many long braids started a few inches away from the scalp are still used in Turkic groups such as Uzbeks and Uyghurs, particularly while wearing folk dress.

Sources/further reading:

Edward William Lane, The Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians.

Heather D. Ward, Egyptian Belly Dance in Transition: The Raqs Sharqi Revolution, 1890-1930

Unfortunately I don't have more to offer you, even for the Turkish style.

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Egyptian ring with a cat and kittens, Faience. XIII-VII centuries. B.C.

254 notes

·

View notes

Photo

AN EGYPTIAN ELECTRUM STIRRUP RING

NEW KINGDOM, 18TH-20TH DYNASTY, CIRCA 1390-1069 B.C.

1 in. (2.5 cm.) long.

This fine stirrup-shaped signet ring would have been used either by the king himself or given by him to a high official with the authority to act on his behalf. As visible by the wear on the oval bezel, it is clear that this ring was used as a seal, probably for royal administrative documents. Solid cast stirrup rings replaced earlier seal types with swivel bezels, as the sturdy form better suited the function for which it was intended. This tradition began at the end of the 18th Dynasty and continued into the 19th.

Electrum is an alloy of gold and silver whose colors vary from greenish-yellow to silvery-grey. Gold of high purity was not easy to cast, so adding silver or copper helped avoid defects due to excessive porosity. Electrum and silver were considered more desirable than gold before the New Kingdom, whereas the much redder color of copper-gold alloys was preferred for stirrup rings during the Amarna and immediate post-Amarna period. This ring was cast through the lost wax method, while the bezel was engraved using iron or copper tools.

At the center of the oval bezel is the Horus falcon wearing the Double Crown, the symbol of the monarchy’s task to unite Upper and Lower Egypt. The feathers and facial markings are finely detailed. In front of the falcon, a rearing cobra wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt is the uraeus protector of the Crown. Behind the falcon is a cobra looped over the sun disc with an ankh around its neck, invoking the sun god Ra. Below are the two horizontal lines and the basket hieroglyph, which together can be read as ‘neb tawy’, meaning Lord of the Two Lands, an epithet of the pharaoh. The composition is exquisitely executed and balanced and is reminiscent of other masterpieces from the end of the 18th Dynasty.

#AN EGYPTIAN ELECTRUM STIRRUP RING#NEW KINGDOM 18TH-20TH DYNASTY CIRCA 1390-1069 B.C.#jewelry#ancient jewelry#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian jewelry#egyptian art

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh u know just contemplating the meaning of life.

n also debating whether to order pizza or tacos.

the existential questions keep me up at night wondering about the purpose of our existence.

as for the food dilemma maybe ill go for a delicious fusion of pizza n taco

n create the ultimate culinary masterpiece.

n this one is too filtery, but i have so much cleopatra stuff i’ll be cosplaying her forever

#cleopatra#cleopatra cosplay#ancient egypt#egyptology#Egyptian jewelry#blue hair#black eyeliner#goth makeup#punk rock girl#btggf

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold, Steatite, Faience and Micromosaic Egyptian Revival Necklace by Castellani

Photo: Sotheby's

Source: townandcountrymag.com

#sothebys#castellani#egyptian revival#egyptian jewelry#multi gem jewelry#egyptian necklace#micro mosaic jewelry#faience#steatite#gold#high jewelry#luxury jewelry#fine jewelry#fine jewellery pieces#gemville

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

#Nefertiti#three strand necklace#Egyptian jewelry#statement necklace#beaded necklace#boho necklace#handmade jewelry#unique jewelry#gift for her#fashion jewelry

0 notes

Photo

EGYPTIAN GODDESS MA’AT DEVOTIONAL NECKLACE

https://www.etsy.com/listing/1403048239/egyptian-goddess-maat-necklace-handmade

White Jade, Opalite, and Wooden Beads, with a Silver and White Opal Pendant, faceted Black Agate end pieces, and a Gold-Colored Metal Lobster Clasp Closure

*COMMISSIONS ALSO AVAILABLE!*

Reblogs welcome and appreciated! <3

#Kemetic#Pagan#Kemetic Fandom#Kemetic Orthodox#Kemeticism#Egyptian Gods#Egyptian Mythology#Egyptology#Ancient Egypt#Ma'at#Maat#Ma'at Goddess#Ma'at Deity#Mother Goddess#Divine Feminine#Devotional Necklace#Pagan Jewelry#Kemetic Jewelry#Egyptian Jewelry#Prayer Beads#Pagan Rosary#Egyptian Rosary#Kemetic Rosary#Devotional Beads#Devotional Jewelry#Kemetic Necklace#Kemetic Prayer Beads

1 note

·

View note

Text

#ancient egypt#cleopatra#egypt#egyptian#egyptian aesthetic#egyptian antiquities#egyptian art#egyptian royalty#eqyptian architecture#queen of egypt#cleopatra makeup#cleopatra worship#cleopatra aesthetic#egyptian scarab#egyptian pharaoh#egyptian cats#egyptian statue#egyptian jewelry#egyptian cat#egyptian pyramids#ancient egyptian#pharaoh#desert#sand

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Bracelet.

Culture: Egyptian

Period: Middle Kingdom; 12th Dynasty

Date: ca. 1900 B.C.

Place of origin: El-Kubanija North, grave 15 l 1, (Grave of a girl)

Medium: Faience, blue-green

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#ancient egypt#ancient history#archaeology#ancient jewelry#egypt#egyptian#bracelet#12th Dynasty#middle kingdom#El-Kubanija#grave of a girl#ca. 1900 b.c.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

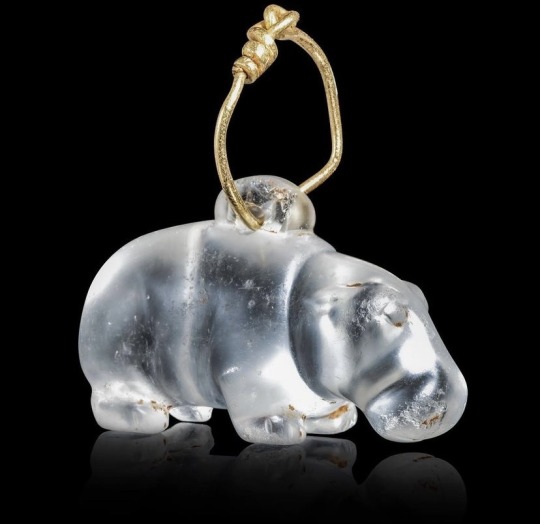

An Egyptian rock crystal of a chonky hinpopotamus amulet

(Middle Kingdom, ca. 2050-1650 BCE)

Amulets were worn by ancient Egyptians for their protective and regenative properties. Used in both in daily life and during funerary rites, amulets represented animals, deities, symbols or objects thought to possess the magical powers of warding off evil spirits.

As animals were popular representations, the hippopotamus was known for its apotropaic (e.g. ability to avert bad luck) qualities and was associated with rebirth.

#art#archaeology#sculpture#ancient#ancient art#ancient egypt#amulet#hippopotamus#apotropaic#egyptian art#egyptology#kemetic#ancient kemet#rock crystal#geology#ancient jewelry#jewelry

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

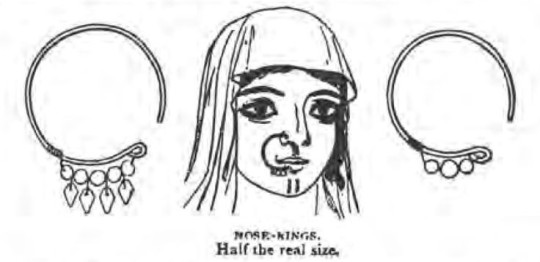

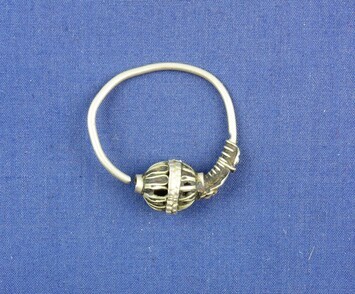

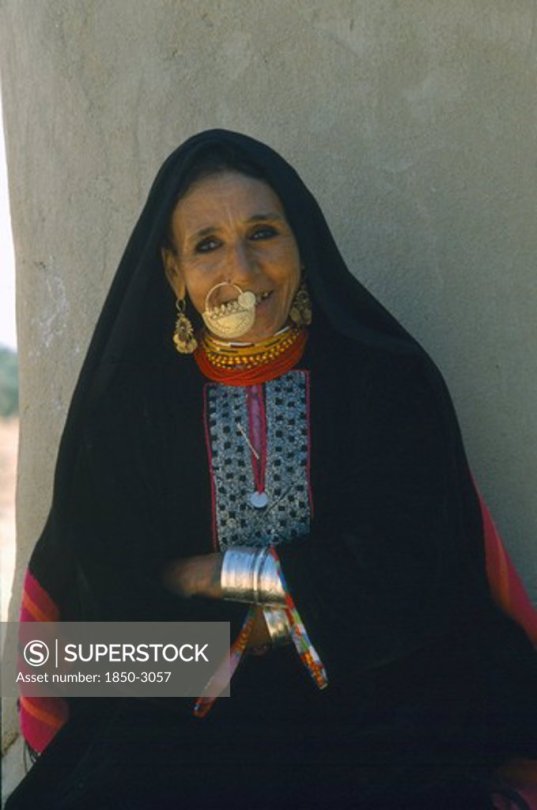

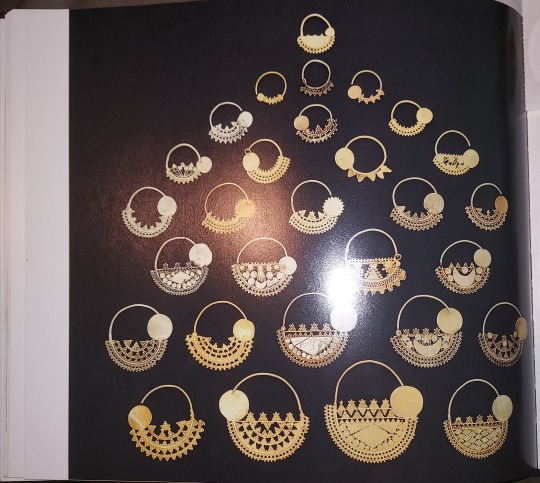

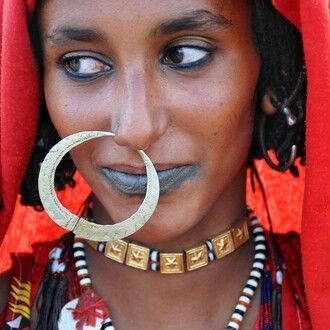

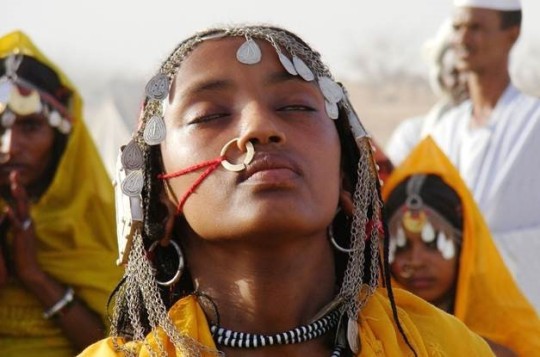

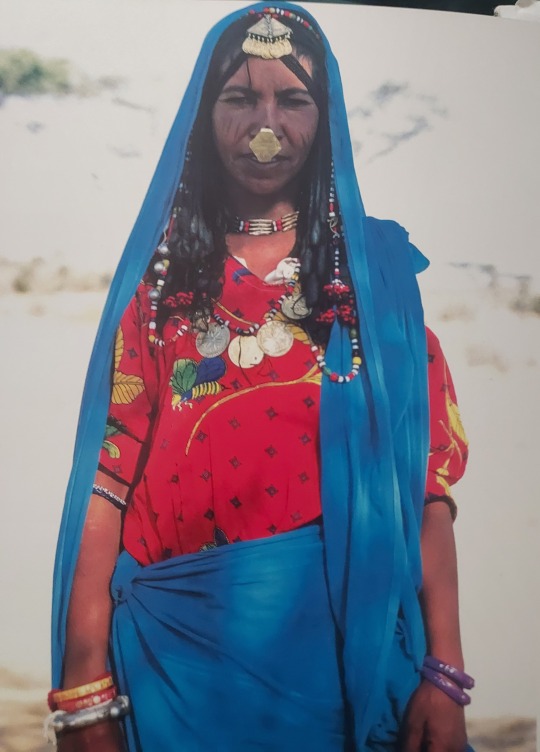

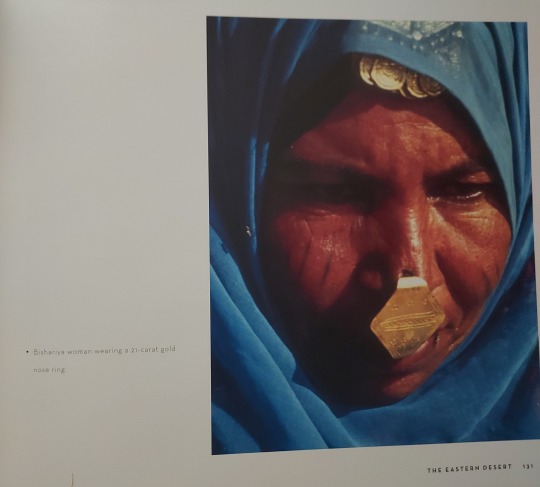

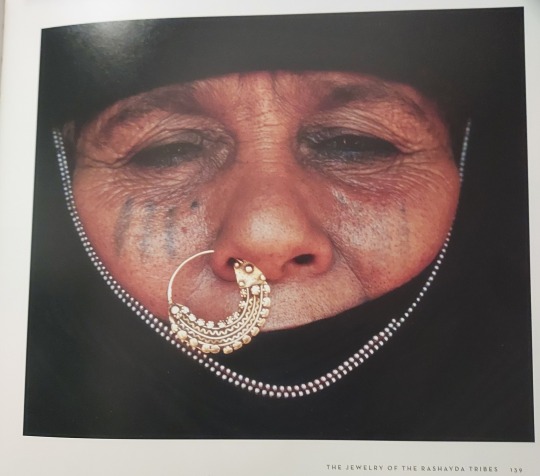

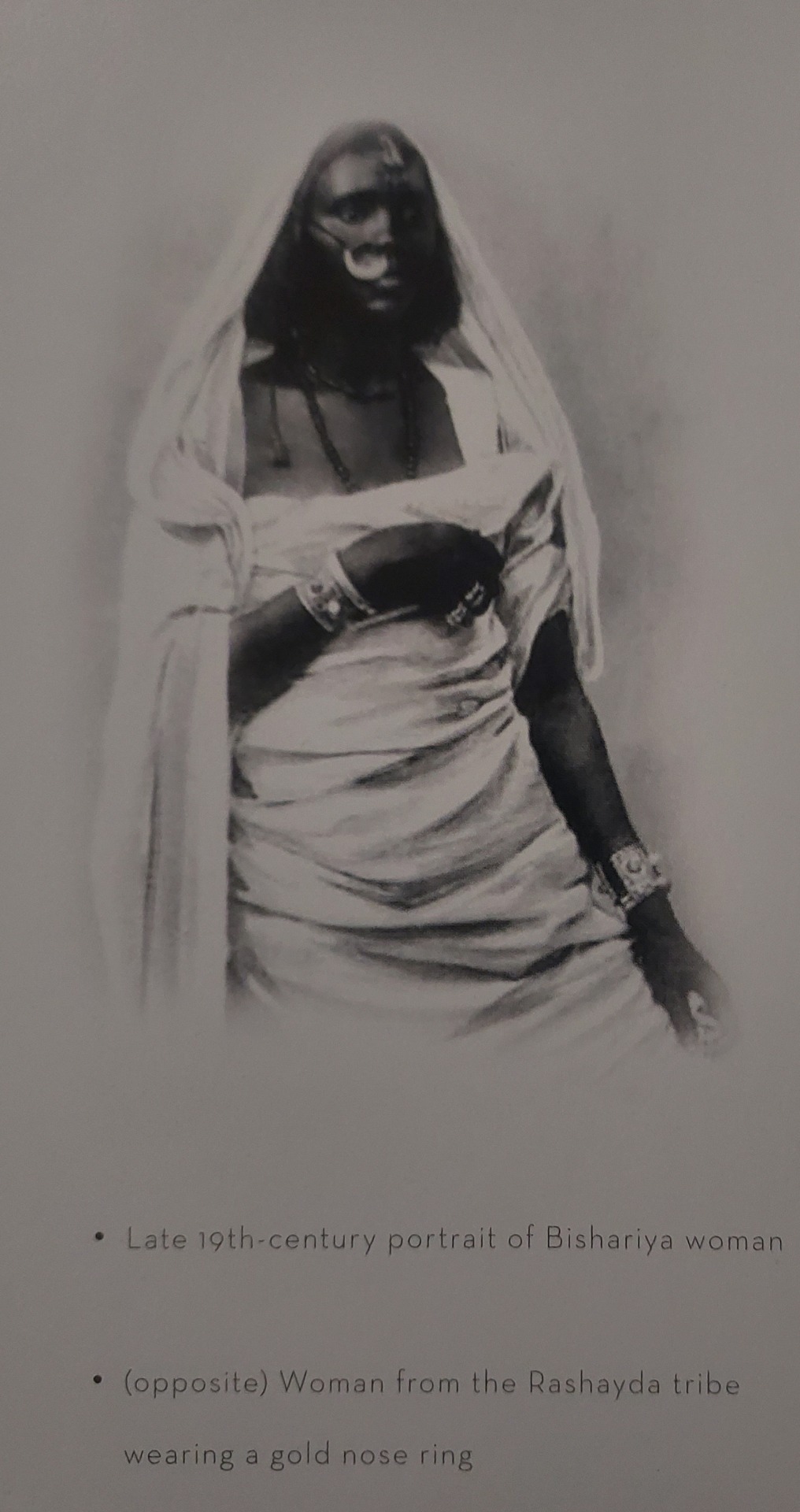

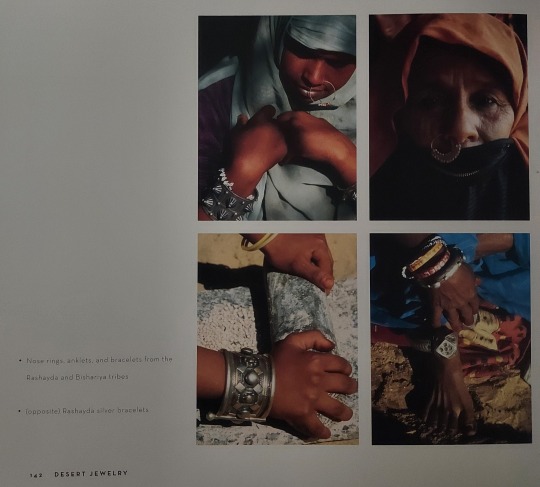

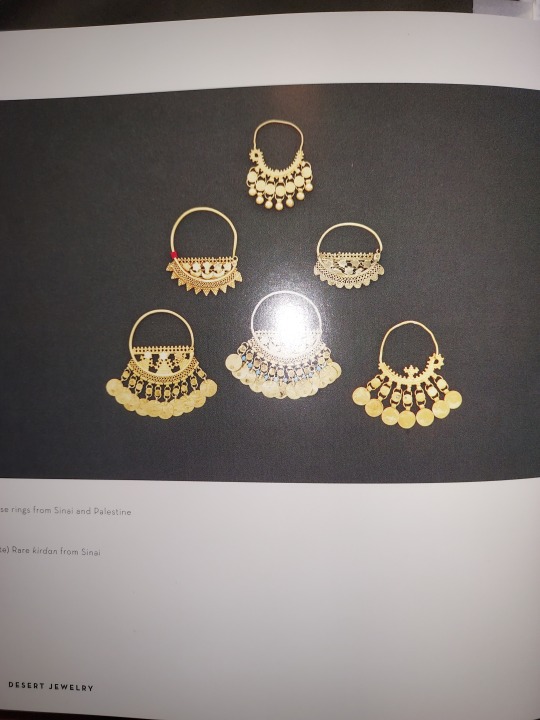

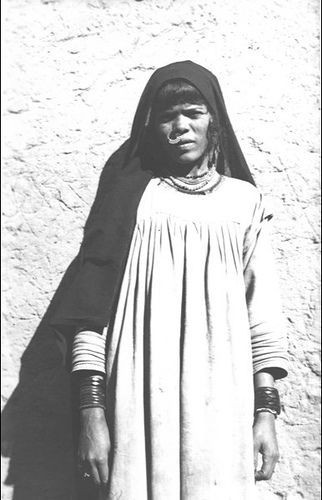

Nose rings in Egypt

Wearing nose rings in the Eastern Mediterranean actually goes back to the time that the Torah was being written. Referred to as nezemim, Rebecca is noted as wearing one. The practice continues to this day, though they are less common and have grown to be more strongly associated with South Asia and Alt sub cultures. Today it is thought that the wearing of nose rings in India may have been imported from West Asia (the assertion that they were brought over by the Mughals seems inaccurate, however, as the first mention of them is from around 1000 AD)- the discussion is somewhat contentious and unfortunately often feeds into political violence and bias against Muslims when mentioned.

The earliest modern depuction of a nose ring being worn in Egypt comes from the 1830s, thanks to our old enemy and research dog, Edward William Lane. He describes then as being made of brass or occasionally gold with glass beads attached to them, an inch to an inch and a half in diameter, says they are worn on the right side of the nose. His account associates them with poor women. He records the name as "khizám" or "khuzám".

A difficulty comes in recognizing nose ring examples held in museums; I have found a few items resembling this style, but they are described as earrings. The V&A is responsible for two cases, and given they have gotten information wrong on both Ancient and Modern Egyptian jewelry, my suspicion is these examples may be misidentified. The two examples will be shown promptly.

Another example of dubious identification comes from a design that may be multipurpose; silver rings with an openwork barrel at one end. The TRC Leiden institute has an example from Saudi Arabia and claims its a nose ring, but it bears close resemblance to some Egyptian examples identified as earrings, and those resemble some Coptic bronze examples also identified as earrings. To my mind this style also resembles Amazigh earrings/head ornaments (these were sometimes attached to the headdress, not the ears themselves). It is also possible that TRC Leiden has misidentified the item.

While Lane says nose rings were worn all over Egypt, the modern discussion I've found strongly associates them with Bahariya, where they are called gatar or qatrah. There, they are made of gold (usually 12 carat), with filigree and granulation filling the lower half, worn on the right side by married women. They also typically have a large flat circle of gold covering the gap where the wire goes through the nose. This is either soldered on or apart of the central wire the nose ring is built around. Occasionally a coral or glass bead is threaded into the wire that passes through the nose. They are never made of silver, as local women say silver would damage the blood vessels in the nose. They also feel that the nose ring prevents pain and headaches while worn, and when a piece has to be sent off to repair, they urge the person transporting it to hurry back.

I've found some discussion of nose rings as worn by Nubians, Sinai Bedouins, and Bisharin (Beja), Ababda (who have closely intermarried with the Bisharin), and Rashayda. The name recorded as used by Nubians and Beja is zimam. I haven't seen enough examples of Nubian or Beja Egyptian nose rings to draw conclusions about common manufacture, but I do have a few examples. One piece, attributed to Egypt by the Philadelphia museum, is a sliver ring with part of the wire flattened and cut halfway through. Azza Fahmy also provides a photo, putting it under a collection of earrings from the Red Sea area. Similar nose rings can be seen in these two photos from Sudan. I have also seen a photo allegedly of an Egyptian Nubian girl with a gold nose ring that has a similar partially flattened design.

Other Sudanese nose rings I've seen are gold, with a chain leading from the ring to the hair, in a similar fashion to the nath in India. However, these are not necessarily synonymous with Nubian nose rings, as Sudan has an Arab/Arabized cultural majority. At some point I'd like to ask someone who knows more about the subject if there is a distinction between the two styles, but as of now I do not know anyone who is knowledgeable on the matter, nor do I know of any academic texts that discuss the issue.

Beja jewelry has a strong influence from Nubian and Sudanese styles, owing to the fact that they live in proximity, and that more Beja live in Sudan than Egypt. Like Nubians, the Beja are an Indigenous group. They're believed to be related to the Blemmyes and the original group referred to as Medjay in Ancient Egypt, and some ostracon exist of their languages written in the Coptic alphabet (The Nubian alphabet is related to the Coptic alphabet as well, with unique letters for certain sounds). I have little information on the Rashayda, but they call their nose ring zimam. They claim to be descended from an Arab tribe, and some information I've seen implies they've intermarried with the Beja. Two nose piercings are in use by the Beja and Rashayda; a diamond shaped one worn in the center bulb of the nose, worn by Beja women, and gold nose rings with engraved designs or strung with beads, worn by both. 21k is the preference in Nubian goldwork, and this seems to be true of these groups as well.

In Sinai, the nose ring is called a shenaf. It has a great deal of similarity to Palestinian nose rings, and has a similar construction to Bahariya nose rings with the lower half full of filigree and granulation. It also sometimes has beads and hanging pieces. It is most commonly made of gold.

Other miscellaneous pictures of Egyptian nose rings:

Further reading:

https://newvoices.org/2021/05/14/most-decorated-women/ https://newvoices.org/2021/05/24/i-put-a-ring-in-your-nose/ | Regarding Jewish piercings and body art

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.dharmadispatch.in/amp/story/history/the-nose-ring-or-nath-is-an-import-from-muslim-invaders https://www.naturaldiamonds.com/style/natural-diamonds-nose-pin-history-legacy/ | regarding Indian nose rings. The first one is unfortunately incredibly biased against Muslims, and I wouldn't link it if I could find a better write up of the argument regarding nose rings being an import to India. I debated including it at all, but figured I should stick to my rule for citing biased sources in Egyptian fashion research; include it, but note the problem.

The Traditional Jewelry of Egypt by Azza Fahmy

The Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians by Edward William Lane

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O79718/earring-unknown/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O79793/earring-unknown/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O79718/earring-unknown/

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O79342/earring/earring-unknown/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O79454/earring-unknown/

https://trc-leiden.nl/collection/?trc=&zoek=saudi&cat=Accessories&subcat=&g=&s=24&f=0&id=2435

https://www.philamuseum.org/collection/object/41469

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carnelian fish pendant, Egypt, 18th Dynasty, 1390-1295 BC

from The Walters Art Museum

2K notes

·

View notes