#De Excidio

Text

Lifesteal conspiracy theory:

It's not just Vitalasy who's posessed, Roshambo isn't who they seem to be. Roshambo may be a North American Minecraft YouTuber however the truth is that he's possessed by the spirit of the 6th century British author Gildas.

It makes sense!!!

'De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae' and 'Clutching My School's Unfair Minecraft Tournament' have such a clear similarity in authorship and language used. Gildas was classically educated and it makes sense that the person he chose to possess would also be educated. If that's not convincing enough here's some more evidence that shows I'm on the right path:

Speaks Latin, Gildas famously was a big Latin enjoyer

Believes the Romans were fantastic and stans them, if you've read De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae then you'll know

The hand motif, one of Gildas' surviving relics is an arm. Arm = hand. It's too obvious at this point

Warrior. According to the famously accurate hagiographies by a Rhuys monk and Llancarfan respectively, Gildas was a great warrior. We saw the ancient battle tactics video. Bit obvious there mate.

It's obvious because Gildas cared about battle tactics and again, fanboyed all. over. the Romans.

Also the pagan thing. Writing about rival religions and exposing and dunking on them? 'I Infiltrated Minecraft's Deadliest Cult' moment.

This is a Roshambo exposé. He is possessed by the spirit of Gildas and it's all becoming crystal clear now. If they wish to defeat him, they need to call an exorcist. They tend to be somewhat Christian though and Gildas gets a good rep there so I'm not sure if it's possible at this point. They're just so clearly similar it's hard to separate them into two separate people.

SHARE AND REPOST TO SPREAD AWARENESS OF THIS VERY SERIOUS AND TOTALLY REAL THEORY ⚠️

#lssmp#Lifesteal SMP#Roshambo#Ro Roshambo Games#Gildas#De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae#De Excidio#This is such a real and serious theory omg#RoshamboGames#is possessed by a 6th century british monk#repost to spread awareness#Gildas theory

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Appendix A in Faletra's translation of Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain

I wanted to cover these too, but they're mostly excerpts so I don't want to cover them individually.

Part of the reason I got Michael Faletra's translation of the History of the Kings of Britain was its appendices. (I believe it's also one of the more recent translations, from 2008, and that was the othe reason.)

I already posted about Vita Merlini, because that's included in its entirety. Everything else is excerpts. Appendix A is focused on historical sources that Geoffrey of Monmouth drew on for his History.

Gildas, the Ruin of Britain (De Exicidio Britanniae)

The intro description of the Isle of Britain, which Faletra included it to illustrate how Geoffrey pulled almost verbatim from Gildas for parts of the History. The excerpt continues on with a lot of deriding Britain (and I believe this is mostly Breton specifically, aka Wales and southern England, but I'm not sure): "Since the days of its earliest settlement, Britain has been over-proud in mind and spirit, rebellious against God, against its own citizens, and even occasionally against kings and peoples from across the sea." Gildas focuses on the history of Britain from the days of the Roman emperors, "describing the evils that Britain has infliced upon others."

He writes from a very Christian perspective, and mostly focuses on Christian martyrs and various saints. This is one of the more lengthier excerpts that Faletra includes in the appendices,covering a significant chunk of time that Geoffrey also covers and pulled from Gildas very directly, minus most of the moralizing.

(Weirdly. You'd think Geoffrey would do more moralizing, but I suppose he was only kind of a priest, having been given a bishop position eight days after a quick ordination as a priest, probably as a reward because the Normans liked his History.)

Pseudo-Nennius, The History of the Britons (Historia Brittonum)

Faletra writes that pseudo-Nennius "seems to have been doing recovery work, wanting to get the facts and stories that he knew on the historical record before his source materials, whether oral or written, were lost forever." It has less rhetorical polish and often offers multiple accounts or versions of an event, and pseudo-Nennius tries to organize the disparate sources. Geoffrey pulls heavily from the History of the Britons for his own Historia, namely for the founding of Britain and the stories of Merlin/Ambrosius and Vortigern, and then expands upon it.

This one is clunkier to read, and more dry. It's a lot of very quick summaries, no poetic turns of phrase. Like Gildas, pseudo-Nennius also desn't seem to have a very high opinion of the Bretons and talks a lot about them being sinful.

I'll cover Appendix B (focused on Merlin) in a separate post.

#michael faletra#geoffrey of monmouth#pseudo-nennius#nennius#merlin#arthuriana#arthurian literature#arthurian newbie#gildas#historia brittonum#de excidio britanniae

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

has the arthurian fanbase here gotten wind of sistersong by lucy holland yet

#arthuriana#ballads#i personally really enjoyed it i liked a lot of the post roman britian/de excidio/historia regum britanniae references/allusions#it is definitely fantastical..but it's not fantasy. like definitely in the arthurian chronicle tradition of some batshit insane#magical things happening in the midst of..real history#i liked the way the original child ballad was woven into the plot but i wasn't expecting how it came in..exactly#keyne was definitely a real treat i wasn't expecting and that's a big reason why i think the book would be a tumblr hit

0 notes

Text

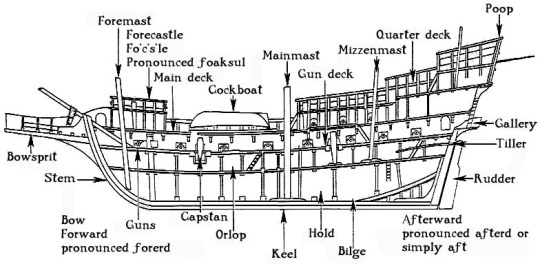

The Keel

The keel is the most important longitudinal structure of a ship or boat, attached to the floor amidships.

Ship parts

In terms of development history, the keel originated from the dugout canoe. The first further development of the dugouts consisted of inserting frames and raising the sides by adding plank walkways. Once this technique had been perfected, the dugout was gradually reduced in size until it was ultimately only the supporting element, the keel, of the hull. The keel is therefore the "backbone" of the ship. The transverse stabilising frames, the "ribs", are attached to it. At its ends, the keel merges into the stem. In addition to stabilising the hull, it also serves to increase course stability and - especially in sailing vessels - to reduce lateral drift.

Even if the word sounds very strange, it comes from Old English cēol, Old Norse kjóll, = "ship" or "keel". It has the distinction of being regarded by some scholars as the first word in the English language recorded in writing, having been recorded by Gildas in his 6th century Latin work De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, under the spelling cyulae (he was referring to the three ships that the Saxons first arrived in).

However, there are also ships that have no keel, such as flat-bottomed ships. This is a sailing ship that was mainly built for use in the mudflats of the North Sea and the English Channel. The two leeboards on the side of the hull and the extremely shallow draught of around one to one and a half metres are characteristic of flat-bottomed ships. They can navigate large parts of the Wadden Sea and coastal regions even at low tide.

#naval history#naval artifacts#parts of a ship#keel#ancient seafaring#medieval seafaring#age of discovery#age of sail#age of steam#modern

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthurian myth: Merlin (1)

Loosely translated from the article "Merlin" of the Dictionary of literary myths, under the direction of Pierre Brunet.

The literary fortune of Merlin was often dependent of the Arthurian literature. However, through its various resonances, the character gained its own seduction and its own popularity that allowed him to return outside of a medieval setting, gaining the status of an autonomous literary myth. He was at first the prophet of the Briton revenge, the one who had initiated the Round Table and who had inspired the errant-knighthood. Through his unique position between good and evil (he is born of a devil and a virgin), between life and death (his paradoxical survival within a “prison of air” or his vault), he embodies in modern times the enigma of History and of the future. Finally, he is the enchanter: causing or suffering many metamorphoses, he is a mythical builder and engineer, and sometimes a warlock/sorcerer. Merlin stays one of the prime heroes of the world of magic.

I/ Origins

The name and the character of Merlin appear for the first time within two Latin-written works of the second quarter of the 12th century, by the Welsh cleric Geoffroy of Monmouth: the “Historia Regum Britanniae” (1136) and the “Vita Merlini” (1148).

Nothing allows us to claim that a character named Merlin (Myrddin in Welsh) existed before these works. The very name of Merlin might have been an invention of Geoffroy, based on the name of the city of Kaermyrddin (today’s Carmarthen). It is also possible that Geoffroy used the phonetic similarity between the city and a “Merlin(us)” which belonged to the Armorican tradition (or more largely the continental one). However, Geoffroy of Monmouth did not start out of nothing. In the middle of the 12th century, Robert of Torigny, library of the abbey of Bec, claimed that two Merlin existed: a Merlin Ambroise/Ambrose (Ambrosius Merlinus) and a Merlin Sylvestre/Sylvester (Merlinus Silvester). This opinion was renewed thirty years later by Giraud of Cambria. Thes two names seem to correspond to two different traditions that Geoffroy joined:

1) “Merlin Ambrose” designates a character of the 6th century named Ambrosius. Gildas (in his “De Excidio et conquest Britanniae) made him the descendant of a Roman consulate family. Nennius( “Historia Britonum” presented him as a child born without a father, and whose mother had sex with an incubus – a tradition maintained by posterior authors. Nennius also provided the motif of the child revealing to the king Guorthigirn (Vortigern) the existence of two underground dragons preventing the building of his citadel. Discovered by the agents of the king at Kaermyrddin, the young Ambrosius interpreted the battle of the monsters as the omen of the long battles between the Briton and the Saxon. When Geoffroy retells this scene, he explicitly identifies Merln to this Ambrosius (“Merlinus, qui et Ambrosius dicebatur”).

2) “Merlin Sylvester” appears mainly in the “Vita Merlini”, and he seems to be the heir of older Celtic traditions. These traditions, shared by both Scotland and Ireland, depict a prince who lost his sanity and ran away into the forest, living there a wild existence while gaining supernatural powers. In Scotland it is Lailoken, known through the “Life of saint Kentigern”: on the day of the battle of Arfderydd (located by the “Cambriae Annals” at 573), this character, companion of the king Rodarch, heard a celestial voice condemning him to only have interactions with wild beasts [Translator’s note: The expression in French here is unclear if it speaks of human interactions or having sex, and I unfortunately can’t check the original Life of saint Kentigern right now]. Several predictions were attributed to him, predictions that the “Vita Merlini” places within Merlin’s mouth. Another incarnation of the “Merlin Sylvester” can be find back as early as the 8th century: in Ireland, the legendary king Suibne, turned mad after the battle of Moira, lived in trees (from which he ended up flying away), and shared similar traits with Lailoken. Similarly, in the Armorique there was the prophet Guinglaff, known through a verse-work of the 15th century “Dialogue entre le Roi Arthur et Guinglaff”.

The link between Merlin and those “wild men” becomes even more apparent thanks to several Welsh poems bearing the name “Myrddin”. Three of them belong to the “Black book of Carmarthen” (Welsh manuscript of the end of the 12th century) : The Apple-Trees (Afallenau), the Songs of the Pigs (Hoianau) and the Dialogue between Merlin and Taliesin (Ymddiddan Myrddin a Thaliesin). If the prophetic passages of these texts cannot be older than the Normand invasion, several lines where the bard talks to the trees and animals of the Caledonian forest (especially his pet-boar), complaining about his loneliness and his sorrow, could be the remains of a poem between 850 and 1050, which could be the oldest record of the Merlin legend.

Despite these many obscure origins, it seems that even before the publication of the “Historia Regum Britanniae” Merlin had awakened a certain interest within Geoffroy’s entourage, since Geoffroy decides to publish in 1134, due to the demands of several people including the bishop of Lincoln, a fragment of an unfinished work of his: the “Prophetiae Merlini”. Inspired by the Books of the Sybil, by the Apocalypse and by the prophetic imagery of Celtic and Germanic tribes, these “Prophecies”, that Geoffroy claimed to have translated from the language of the Briton, is first a record of several events that happened in Great-Britain since the Saxon invasion until the reign of Henry the First. Then, they announce in an obscure fashion the revenge of the Briton, and a series of disasters prefacing the end of the world. This text was a huge success: until the end of the Middle-Ages, these “Prophecies” were commented and quoted as equals to the holy Christian books. Alain of Lille, the “Universal Doctor”, wrote a commentary of the Prophecies in seven books. Merlin, first the great prophet of Wales, then of Scotland, was adopted in the 14th century by the England, which completely forgot the anti-Saxon origins of the character, and took the habit of beginning almost every speech by quoting a Prophecy of Merlin.

The ”Historia Regum Britanniae”, after the story of the two underground dragons and the text of the Prophecies, attributes to Merlin the building of Stonehenge, in the memory of Briton princes treacherously killed. Finally, it tells of how the prophet gave to the king Uter Pendragon magical potions that gave him the appearance of the husband of the duchess Ingern. A trick that allow the birth of the future king Arthur. As early as this first work, Merlin appears at the same time as a prophet and a wizard: a character claims that no one can rival with him when it comes to predicting the future, or accomplish complex machinations (“sive in futuris dicendis, sive in operationibus machinandis).

The ”Vita Merlini”, told in verse, completes Merlin’s biography by telling adventures of a very different tonality. Seer and king in the south of Wales, Merlin became mad after a deadly battle, and lived in the woods like a wild beast. Only the music of a zither can appease him. Led to the court of king Rodarch, chained in order to be kept there, he proves his gift of second sight throughout several “guessing scenes”. Before returning to the woods, he agrees to letting his wife Guendoloena marry again. However, on the day of the wedding, he appears with a horde of wild beasts, riding a stag. Ripping one of the antlers of his ride, he uses it to break the head of Guendoloena’s new husband. The rest of the text depicts Merlin as being saved by his sister Ganieda: he performs a series of astronomical observations and makes prophecies about the future of Britain. His disciple Thelgesin (identified with the Welsh bard Taliesin), back from the Armorique, joins him and they talk lengthily about nature. Finally, Merlin regains his sanity thanks to the water of a stream that just appeared, but he refuses to rule again and stays faithful to the forest.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cursed Rulers: Parallels Between Auberon & Emhyr

“Emperors rule their empires, but two things they cannot rule: their hearts and their time. Those two things belong to the empire.”

“The end justifies the means.”

Leaders of the highest order for their people, both rulers pursue the greater good at the expense of decency and their own humanity. A greater good to be achieved through similar means – by begetting the child who is prophesised.

Etymology

Let’s start with names for the names we give our characters often betray the backdrop from which we drew in conceiving them; especially if the author is a self-confessed fan of the subject matter.

Nilfgaard’s Emperor’s real name originates in the history of the British Isles and in the Arthurian legendarium. In Welsh, Emyr denotes “ruler” or “king.” Emreis, meanwhile, qualifies as the Welsh counterpart to the Greek Ambrose, serving as the equivalent for the Romanized Ambrosius. Ambrosius Aurelianus, a semi-mythical figure thought to have lived around the time Romans had recently left the Isles for good, was a Romano-British warlord credited with turning the tide against the invading Angles and Saxons. Very little about Sub-Roman Britain is verifiably beyond doubt, which means the era lends itself richly to myth craft (for which reason historians search within this period for the historical Arthur). Most chroniclers and myth-makers way back when were monks. Gildas mentions Ambrosius Aurelianus first in De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae. A Roman by blood, methods and upbringing, Ambrosius is thought to have claimed the position of a High King after the Bryton Vortigern and to have ushered in over a century of peace by pushing out the Germanic tribes and defeating them at Mons Badonicus (Mount Badon). Bede describes Ambrosius as “a modest man of Roman origin, who was the sole survivor of the catastrophe in which his noble parents had perished”. From Nennius onward though, the myth grows and factual matter starts to ebb.

Geoffrey of Monmouth links Ambrosius with the wizard Merlin, Uther Pendragon (whom he makes Ambrosius’ brother) and Constantine III (allegedly Ambrosius’ father). Co-incidentally, Emreis or Emrys is also the birth-name of Merlin (Latinized from the Welsh Myrddin, the great bard). But for the sake of comparing to Emhyr var Emreis as known in the Witcher, making Constantine III the father of Ambrosius is especially noteworthy. A Roman general come to power during the Roman Britain revolt, Constantine headed out to Gaul with all the mobile troops left in Britain in 407, leaving the island vulnerable to the migration of Germanic tribes. The general ended up declaring himself the Western Roman Emperor; a position he held for two years beside the sitting emperor Honorius. Then he was put to death by another general (who, surprise-surprise, also went on to declare himself). Geoffery of Monmouth changes his Constantine III’s background a little from the historical one, but importantly for us makes it so Constantine’s sons – Ambrosius and Uther – are smuggled to Brittany after their father’s death. There the exiles are gathering strength in order to later return and challenge the usurper Vortigern. These plot beats are familiar to what we know of Emhyr var Emreis.

In Welsh, Emrys also means “immortal” but Emhyr var Emreis – despite having lived several lives – is still a mortal ruler. Auberon Muircetach on the other hand exudes eternity. So old as to appear near immortal to Emhyr’s daughter, the Alder King retains a youthful appearance despite the thousand yard stare in which is buried unimaginable sadness. In his folk origins, Auberon is leading several lives.

Bearing Hen Ichaer (ichor (Ancient Greek), blood of the gods), Auberon (Old French) appears first in the 13th century Les Prouesses et faitz du noble Huon de Bordeaux and gives Shakespeare his fairy king Oberon who rules the spirit world. In turn, the name in Old French originates in the Germanic Alberich (or Elberich), denoting “the ruler of supernatural beings.” The most well-known Alberich is probably Wagner’s, from De Ring des Nibelungen, and though called a dwarf he treads closer to Svartálfar (dark elves) in character; dwarves and elves being, on occasion, conflated in Continental Europe. An important nuance though is that Alberich much like Auberon is the keeper of his subjects’ magical treasure (Rheingold/Andvaranaut Ring, or Elder Blood respectively), which is the source of power and wealth of each one’s race. Circling back to the suitability of Shakespeare’s adoption of the name for his fairy king, the root “alb” in Alberich originally stands for “white” and forms the trunk of Albion – denoting the British Isles with its white cliff face.

The character of Auberon Muircetach (as of the other Alder elves) is linked to Goethe’s Erlkönig; a haunting force of corruption and death, a stealer of souls who covets youthful innocence. This stands in contrast to Johann Gottfried von Herder’s translation of the Danish folk ballad Elverkongen’s Datter (The Elf-King’s Daughter) which inspired Goethe but where the protagonist is a wilful, selfish female spirit. Androgyny though is not new to elves. Erlkönig translates into English variously as Erlking, the Elf-King, and the Alder King. Erle (or Elle in Old Danish) stands for “alder” in German, and Ellefolk is a folkish use of “elves” in Denmark. Calling the Otherworld elves in the Witcher Aen Elle – the Alder Folk – is thus hardly wilful. But what do elves and alder trees have in common? As elven culture and origin story in the Witcher draws heavily on the Celtic world, an amusing example emerges on the plains of Albion. During the mythical Cad Goddeu – Battle of the Trees – the alder trees are animated by Gwydion and march in the vanguard while Bran the Blessed (a Welsh God-king figure) boasts alder twigs as personal protection and heraldry. Alder is the warrior of trees; the bark bleeds when cut, changing from white to red. Alder is also linked to the realm of water and wetlands – predominant on the plains of Somerset surrounding the Glastonbury Tor (a well-known place of power and an entry to Caer Sidi and the Otherworld). Bran is wounded by a poisoned spear in the course of Cad Goddeu and so he is sometimes deemed one of the first prototypes for the Fisher King, an Arthurian figure Sapkowski’s Auberon (and elves) amounts to in lieu of symbolic fit – an ailing ruler, rendered impotent with an injury which dooms the realm. In this manner links between the Continental Erlking and Celtic mythos shape up.

Finally, Muircetach – an alteration of the Irish Muirchetach also stands for “mariner.” Befitting of an Elf-King who has traversed the seas of time and space.

Intent

In the Witcher, both Auberon and Emhyr are embroiled in a plot of siring the child of prophecy with Cirilla Fiona Elen Riannon – their blood relative. Genetically, the incest is a matter of degree: Emhyr is Ciri’s biological father, Auberon Ciri’s ancestor 8 generations past. Symbolically, however, the degree collapses with Auberon because a few human generations are meaningless to elves. They call Ciri Lara’s daughter, effectively deeming Ciri Auberon’s granddaughter. But the reader – not unlike Ciri herself – won’t know about this until the very end of the tale.

Notionally, both rulers bind their actions with Ithlinne’s prophecy. The problem with prophecies is they decouple arguments from verification, lending themselves to the rationalization of all and any action. At least insofar as knowing the future accurately is impossible. This is the case for humanity, it is not the case for elves. Elven prophecies were made by the elves and for the elves in the first place. Consequently, the degree to which each ruler knows the prophecy to be true and believes in it differs. For Emhyr, mystical secret knowledge of the universe is irrelevant in comparison to political expedience: reason of state is what the tomorrow will bring. The Nilfgaardian Emperor is neither a mystic nor a fatalist. Contrary to the Alder King – a Sage, a ruler, and an elder – who has witnessed and likely verified some of what the Seers have prophesised. Elves conceive of the nature of time as cyclical in which the fate of things is tied up in the endless repetition of endings giving birth to new beginnings, the dance of attraction between life and death, two sides of the same coin which form the singular eternal truth of existence – change is only an eternal reoccurrence and re-arrangement of all. Auberon, you see, is a bit of a mystic. And even without Seers privy to secret knowledge, an extraordinary life span reduces the elves’ proclivity to black swan fallacy, or at least pushes the error probabilities. But at the end of the day, mysticism takes the cake.

The idea that either ruler must be the progenitor, however, comes at the instigation of an outside force.

Shortly after Ciri’s birth Emhyr is visited by a sorcerer. Emhyr has a strong aversion to mages; he was cursed by one. Even so, Vilgefortz proves himself capable of helping him regain the Nilfgaardian throne and is straightforward about what he wishes in exchange – gratitude, favours, privileges, power. Vilgefortz tells Emhyr about Ithlinne’s prophecy – a version about the fate of the world; a human interpretation. Then he plants the seed as to what Emhyr should do to steer the fate of this world. Naturally, he has his own agenda. It is not a huge leap of imagination to conceive of Auberon having been similarly persuaded by Avallac’h (an elven Knowing One who thematically parallels the human Vilgefortz). Not only are Avallac’h and Auberon tied by broken familial bonds, they are each a participant of the Elder Blood programme; and each, a Sage. Avallac’h serves nearly as a double for Auberon, his own fate also tied with Ciri’s. And Auberon is a “willing unwilling” in his arrangement with Ciri; implied so in his rage when he reveals Ciri ought to be grateful to him for lowering himself to the endeavour at all. There is an alternative.

Neither the Emperor nor the Alder King is pursuing the incestuous course of action out of lust. But both have the option to waive being the sire. Ithlinne’s prophecy is not explicit about the father of the Swallow’s child. For elves the match is backed by science. For humanity – pragmatism.

Emhyr has ordered to wipe out the Usurper’s name from the annals of history and is cementing his earthly power, conquering and ensuring the succession laws play out in his favour. Not only is he legitimatizing his rule over Cintra – the gateway to the North – by marrying its last monarch’s granddaughter, by keeping it in the family, he is also consolidating his rule among the Nilfgaardian aristocracy. The Emperor’s concern lies with the dynastic struggle for power: it is his blood that should rule the world and because history is bending its arc according to Nilfgaard’s dictation that means surmounting the Nilfgaardian succession laws. From such perspective, not fathering Ciri’s child would create numerous problems. Ciri as Emhyr’s heir would remain behind any other male offspring he might have (with any Nilfgaardian aristocrat). Ciri might not be acknowledged as a legitimate successor in Nilfgaard in the first place as she is a foreigner, born in Cintra at a time when her father was not yet an emperor; a bastard, effectively, and a girl besides. Ciri’s husband, moreover, may have designs on power himself and his remaining under Emhyr’s control, or Ciri’s control, is not a guarantee. It is difficult to be the correctly-shaped chess piece in a game of interests of the state. That a widely recited prophecy about the fate of the world can lend an aura of destiny to the brutal political machinations undertaken to seek retribution and pursue earthly power is convenient; a descendant who will be the ruler of the world – a bonus. But to get there sacrifices must be made.

‘Cirilla,’ continued the emperor, ‘will be happy, like most of the queens I was talking about. It will come with time. Cirilla will transfer the love that I do not demand at all onto the son I will beget with her. An archduke, and later an emperor. An emperor who will beget a son. A son, who will be the ruler of the world and will save the world from destruction. Thus speaks the prophecy whose exact contents only I know.’

’What I am doing, I am doing for posterity. To save the world.’

- Lady of the Lake

Notably, the manner in which the Emperor claims to understand Ithlinne’s prophecy does not make guarantees that a father’s incest with his daughter will ensure his progeny will one day save the world. The saviour is a few generations away and the causal arrow between now and then is not direct: the son could die, could father a child with a genetically non-fitting partner, could be sterile, or could turn out to be a daughter altogether. Not to even begin with what the world needs saving from in the first place; again, elven prophecies were written by the elves and for the elves. Emhyr var Emreis is neither an elf, a geneticist, an idealist nor a mystic. He is an autocrat.

Elder Blood is the creation of elves and it is elves who understand how their genetic abilities play into handling what was foretold by Ithlinne. Emhyr’s daughter, the Lady of Time and Space, is the descendant of an Alder King who has utilized Hen Ichaer in the past and whose ambitions lie in an altogether different ball park than that of an Emperor of one single world. Appropriately to the Saga’s love for subversion, it is ironic that human understanding of elven prophecies remains on the level of poetry, while elves – the irritatingly poetic, mystical species – can read the science elevating the prophetic jargon into something more. Which regardless does not invalidate the problem with prophecies: they lend themselves to the rationalization of action, frequently covering up the real horses the powerful might have in the race. Legitimatization of the ruler’s right to remain the leader of their people is relevant in Auberon’s life too. More on that when we return to the Fisher King parable and the nature of curses upon the two rulers.

Role & Relationships

Let’s take a look at the characters’ personalities.

Appearance: a play of contrasts

A very tall, slender elf with long fingers and ashen hair shot with snow-white streaks. An elf with the most extraordinary eyes – as on all Elder Blood carriers – reminiscent of molten lead. A man with black, shiny, wavy hair bordering an angular, masculine face that is dominated by a prominent nose (hooked, presumably, or Roman if you like). The Emperor of Nilfgaard does not resemble an androgynous elf by any means. But this does not mean nothing remains in him of the elven gene pool. Not only does Emhyr’s etymological origin link with the Romano-Celtic world underpinning all things elven in the Witcher. Nilfgaardians are effectively the Romano-Brytons. The human population in the South of the Continent mixed with elves heavily, retaining a lot of elven law, customs, language, and DNA. As Avallac’h says about heritability, “the father matters,” and Emhyr was one half of the equation for getting Ciri.

Rex Regum - King of Kings

The readers are probably more familiar with the imperial system and how that features in the depiction of Nilfgaard. Auberon Muircetach’s position as the Supreme Leader of the Aen Elle – as opposed to merely a “king” – is instead much more reminiscent of the station of a High King.

Ancient and early kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland boast many High Kings (e.g. Ard Rí Érenn Brian Boru, Ard Rí Alban Macbeth, Vortigern, King of the Britons, etc). The High King was usually elected and set above lesser rulers and warlords as an overlord in a land that shared a high degree of cultural unity. Emperors usually ruled over culturally different lands (regularly obtained through recent or ongoing conquests). In character such high kingship was sacred: the duties of the ruler were largely ceremonial and somewhat restricted, unless war, natural disaster or any other realm-wide occasion created a need for a unified command structure. The Irish High King, for example, was quite straightforwardly a ruler who laid claim to all of the land of the Emerald Isle. Noteworthy, because the ruler is frequently seen as the embodiment of the land, associated with the health and well-being of the realm that the land sustains. In quasi-religious terms, High Kings gained their power through a marriage to, or sexual relationship with, a sovereignty goddess; frequently, a mother goddess who was associated with the life-giving land. As one of the most frequently studied elements of the Celtic cosmology, this feature is instantly recognisable in the outlook of the elves in the Witcher and factors heavily into Auberon’s relationship with Ciri. Ciri who is the avatar of the Triple Goddess – the Virgin, the Pregnant Mother, and the Old Woman Death. As Sapkowski notes in Swiat króla Artura. Maladie:

“…no Wiccan mystery in honour of the Great Triple, cannot be performed, [without] the goblet and the sword.

Grail and Excalibur. The rest is silence.”

Through the Triple Goddess’ interaction with her God-counterpart (a ruler who briefly assumes the role of the god) is showcased the eternal cycle of life – one which cannot be realised without the interaction of the cup (feminine) & the sword (male). Excalibur is the symbol of rightful sovereignty and its wielders are frequently powerful men, but Ciri is a woman and a woman is the Grail, bringing salvation and new life. To possess the Grail is to legitimize oneself as the ruler, as the leader, protector, and father figure of the realm. Thus a King of Kings must do exactly that. A protector, a father figure, and a druid (wise man) merge into a symbolic whole in the Supreme Leader of the elves.

(But Ciri is also the witcher girl and owns a sword, unyielding before the matter of her gender. And though many a men might take her for the Lady of the Lake, she is not about to part with her sword.)

The realm is all

From early age, Emhyr’s father instilled an understanding in his heir that nothing counts more than the interest of the state. The blood of the Emreis family must be on the throne. Fergus never abdicated, not after torture, not even after his son was turned into a mutant hedgehog in front of his eyes. Love for his child did not sway Fergus from having his son suffer in the interests of power and the realm. This is how the shard of ice in Emhyr’s heart forms. Auberon, equally, “thinks of England” when attempting to regain his daughter’s legacy and restore their people’s power. The circumstances of Lara’s demise, however, beg the question about the Alder King’s role in facilitating or enabling the conditions that let things spiral out of control and break beyond repair. The stakes were infinitely higher for Auberon than they are for Emreis’ dynastic struggle. But what would an answer to this question change? In their cold hearts these characters see themselves each as duty-bound.

Ambitious and gloried, they nevertheless occupy different stages in their lives.

Emhyr’s ambition burns bright and fresh. Auberon’s has dwindled into a shadow of the past; buried under having witnessed and lived through the sacrifices that a ruler makes in the name of power. Emhyr chooses to seek retribution and power beyond what would befall him should he accept his life as Duny (the cursed, pitiful Duny), the prince consort of Cintra. Never losing sight of his goal, love and human happiness become temporary phases and means to an end, and Emhyr returns to Cintra only in the form of flames and death to pursue his daughter in insane ambition. The White Flame retains an active disposition; a lust for life. Neither Emhyr nor Auberon gallop at the head of their armies though, leading instead from the rear. They have lackeys for carrying out their will remotely (e.g. Cahir and Eredin). Emhyr, however, is said to be otherwise highly involved in the ruling of his empire, even if many revolutionaries who had helped him on the throne had hoped he would remain but a banner of the revolution. In contrast, the Alder King has more or less withdrawn from life and active service. In presence of Avallac’h and Eredin, Auberon appears much more like the standard Emhyr had refused to become. Of course, many decisions the equivalent of which Auberon has already made are still ahead of Emhyr, including as concerns the freedom of his daughter.

A ruler’s heart

Did Emhyr believe that he would be able to see Pavetta in Ciri and thus push through with the incest? Did Auberon hope to glance the memory of his wife in the eyes of Lara’s “daughter” and manage in this way? As already noted, neither ruler is pursuing their plans out of lust, but as lust must be induced for the act to bear fruit I cannot help but wonder what these characters must do to themselves to follow through with their plans. Because the love that is called for between a woman and a man in order for new life and hope to be born is in this instance abnormal. Yet it is undoubtedly love that plays a huge role in determining both Emhyr’s and Auberon’s eventual fate.

Until the emergence of false-Ciri, Emhyr var Emreis is said to have had numerous ladies in the imperial court. Little is known about Auberon’s disposition, but by the time Ciri starts frequenting his bed chamber it has become evident the image of a dowager king fits the elf like a glove; disaffected with romantic dalliance, he is still aware of the courtly intrigue and expectations surrounding it.

The next evening, for the first time, the Alder King betrayed his impatience.

She found him hunched over the table where a looking glass framed in amber was lying. White powder had been sprinkled on it.

It’s beginning, she thought.

…

At one moment Ciri was certain it was about to happen. But it didn’t. At least not all the way.

And once again he became impatient. He stood up and threw a sable fur over his shoulders. He stood like that, turned away, staring at the window and the moon.

- Lady of the Lake

Emhyr’s marriage to Pavetta, Ciri’s mother, was an unhappy one. In his own words, he did not love “the melancholy wench with her permanently lowered eyes,” and eventually would have had the vigilant Pavetta killed. Inadvertently, Emhyr caused Pavetta’s death anyway.

‘I wonder how a man feels after murdering his wife,’ the Witcher said coldly.

‘Lousy,’ replied Emhyr without delay. ‘I felt and I feel lousy and bloody shabby. Even the fact that I never loved her doesn’t change that. The end justifies the means, yet I sincerely do regret her death. I didn’t want it or plan it. Pavetta died by accident.’

‘You’re lying,’ Geralt said dryly, ‘and that doesn’t befit an emperor. Pavetta could not live. She had unmasked you. And would never have let you do what you wanted to do to Ciri.’

‘She would have lived,’ Emhyr retorted. ‘Somewhere … far away. There are enough castles … Darn Rowan, for instance. I couldn’t have killed her.’

‘Even for an end that was justified by the means?’

‘One can always find a less drastic means.’ The emperor wiped his face. ‘There are always plenty of them.’

‘Not always,’ said the Witcher, looking him in the eyes. Emhyr avoided his gaze.

‘That’s exactly what I thought,’ Geralt said, nodding.

- Lady of the Lake

After Pavetta’s demise Emhyr hounds his own daughter to the ends of the earth, killing her grandmother, burning down her home, and driving Ciri into an exile from which she never fully recovers. An exile which kills the innocence in her; the snow-white streaks in Ciri’s hair are from the trauma. In contrast, Auberon does not seem to even know what became of Shiadhal – his partner and the mother of their daughter together. On the verge of death he confuses Ciri for Shiadhal and says, “I am glad you are here. You know, they told me you had died.” The Alder King recalls Shiadhal affectionately, in the same loving breath as he recalls their daughter Lara. Lara whose exile – voluntary or not – killed her.

When Ciri was six years old, Emhyr took a lock of hair from her and held onto it; out of sentiment and for his court sorcerers to use. One of Auberon’s last lines to Ciri involves tying a loose ribbon back into Lara’s hair.

In regard to their brides-to-be, both rulers are saddled with fakes. A fake Ciri-Pavetta and a fake Shiadhal-Lara. But Emhyr’s and Auberon’s attitude toward the fake is diametrically opposite. Emhyr sees false-Cirilla as “a diamond in the rough.” Auberon calls Ciri “a pearl in pig shit, a diamond on the finger of a rotting corpse.” For Emhyr, a diamond is the essence of his poor peasant girl. While a pearl in pig shit, for Auberon, remains the essence of Ciri. Neither ruler can entirely ignore the social vigilance extended toward the ruler’s bedchamber either. The idea of a “foreign bride” is frowned upon among the Nilfgaardian aristocracy; it decreases their ability to influence the Emperor. Ciri’s social status at Tir ná Lia is never explicitly addressed, but the presence of human servants – all of whom that the reader sees are female – and casual xenophobia from Auberon himself does not make it hard to venture a guess.

‘If I were … the real Cirilla … the emperor would look more favourably on me. But I’m only a counterfeit. A poor imitation. A double, not worthy of anything. Nothing …’

- False-Cirilla

Lady of the Lake

‘It’s all my fault,’ she mumbled. ‘That scar blights me, I know. I know what you see when you look at me. There’s not much elf left in me. A gold nugget in a pile of compost—’

- Ciri

Lady of the Lake

The Alder King is unable to bring himself to love Ciri. The Emperor relents, caring for his daughter at last as a father should at the very end, in the one moment where it matters. Moreover, Emhyr ends up eventually marrying his own reason of state and comes to love the false-Cirilla. The contrasts do not end here. Real Ciri threatens to tear Emhyr’s throat out for what he is planning to do to her (unknowing that he is her father), yet with Auberon Ciri turns submissive and grows attached. She weeps over Auberon’s corpse and vows vengeance on Eredin for killing the Alder King. Ironic as Auberon never intended to let Ciri go, while Emhyr does let his daughter walk free. The shard in Auberon’s heart never melts. It shifts in Emhyr’s.

In their last meeting with the girl, both rulers implicitly reveal their blood relation to Ciri.

Cursed Rulers of the World

Emhyr’s tale begins and is framed with a curse. Likewise Auberon’s. And for both it is love in its different manifestations that will shift the curse just enough to offer closure. For healing largely entails obtaining closure.

‘They were silent for a long time. The scent of spring suddenly made them feel light-headed. Both of them.

‘In spite of appearances,’ Emhyr finally said dully, ‘being empress is not an easy job. I don’t know if I’ll be able to love you.’

She nodded to show she also knew. He saw a tear on her cheek. Just like in Stygga Castle, he felt the tiny shard of cold glass lodged in his heart shift.’

- Lady of the Lake

The reference to H. C. Andersen’s fairy tale of the Snow Queen is self-evident. Emhyr var Emreis is an Emperor whose heart has been pierced by a shard of ice. In the Saga the legend is elven and refers to the Winter Queen who conducts a Wild Hunt as she travels the land, casting hard, sharp, tiny shards of ice around her. Whose eye or heart is pierced by one of them is lost; they will abandon everything and will set off after the Queen, the one who wounded them so gravely as to become the sole aim and end of their life.

There are two ways in which to interpret the way Sapkowski applies the legend of the Snow Queen in the Saga. First, as a complement to the author’s stance that in life - where most things are shit - the Holy Grail is a woman, because it is the love of a woman and the hope a woman instils that often makes men act in inconceivable ways; love is the great motivator and the great balancer of scales. Almost as powerful as death. Or more so?

‘I would not like to put forward the theory that hunting for the wild pig was the primordial example of the search for the Grail. I don't want to be so trivial. I will - after Parnicki and Dante - identify the Grail with the real goal of the great effort of mythical heroes. I prefer to identify the Grail with Olwen, from under whose feet, as she walked, white clovers grew. I prefer to identify the Grail with Lydia, who was loved by Parry. I like New York in June… How about you?

Because I think the Grail is a woman. It is worth investing a lot of time and effort in order to find it and gain it, to understand it. And that's the moral.’

- A. Sapkowski

Swiat króla Artura. Maladie

In this reading, we find the framing to the stories of Geralt and Yennefer, Lara and Cregennan, Avallac’h and Lara, and many others. Including the story of Ciri herself – for Ciri is ultimately the author’s Grail in more ways than one. More than one party goes to great lengths to solicit her favour in a guise that includes elements of a love relationship but not the heart of it.

Secondly, we can interpret the legend in universal terms: the shard of ice is the definitive experience of our lives which distorts reality and makes the rest of our lives spin around it in one way or another. For Emhyr, such an experience could have been the trauma experienced in his youth. Fergus’ uncompromising death conditioned the boy early on to sacrifice personal feelings to the cause and let the only true feeling in his heart remain forever locked behind the ends a ruler must go to unthinkable lengths to achieve. Fergus did not deem his son above suffering for a cause and the son learned the lesson. Until…

In Andersen’s Snow Queen, Gerda manages to find her brother Kai in the Snow Queen’s castle, but despite her calls his heart remains cold as ice. Only when Gerda cries in despair do her tears finally melt the ice and remove the piece of glass from Kai’s eyes and heart. In the Witcher, the shard in Emhyr’s heart moves first upon witnessing his true daughter’s angry tears. For the second time – in thanks to the bogus princess of Cintra; his poor raison d’etat.

It brings us to the defining contrast in Emhyr’s and Auberon’s stories, and it concerns alleviating the suffering of those are bound to you by blood or love.

Recalling another case of incest that resulted in Adda the strigga, we may remember that the Temerian king recognises that his daughter is suffering and insists on disenchanting her instead of killing her. Realising that your own blood – who has been thrown into this world of suffering thanks to you – is suffering and consequently choosing to do something to alleviate this suffering fortifies the Saga’s faith in enduring human decency. Geralt himself is thoroughly vexed by the prospect of letting the same evil happen to Ciri that happened to himself and does everything within his power to prevent it (failing, trying anyway). Here lives the redemption of man, and in redemption his rebirth.

‘They passed a pond, empty and melancholy. The ancient carp released by Emperor Torres had died two days earlier.

“I’ll release a new, young, strong, beautiful specimen,” thought Emhyr var Emreis, “I’ll order a medal with my likeness and the date to be attached to it. Vaesse deireadh aep eigean. Something has ended, something is beginning. It’s a new era. New times. A new life. So let there be a new carp too, dammit.”’

- Lady of the Lake

As Emhyr and false-Cirilla take a stroll in the gardens after Stygga, they pass a sculpture of a pelican pecking open its own breast to feed its young on its blood. An allegory of noble sacrifice and also of great love – as False-Ciri tells us.

‘Do you think—’ he turned her to face him and pursed his lips ‘—that a torn-open breast hurts less because of that?’

‘I don’t know …’ she stammered. ‘Your Imperial Majesty … I …’

He took hold of her hand. He felt her shudder; the shudder ran along his hand, arm and shoulder.

‘My father,’ he said, ‘was a great ruler, but never had a head for legends or myths, never had time for them. And always mixed them up. Whenever he brought me here, to the park, I remember it like yesterday, he always said that the sculpture shows a pelican rising from its ashes.’

- Lady of the Lake

It is difficult to set aside our trauma and not pass it on to our children. Letting our children be free to choose and not sacrificing them on the altar of our fate is to rip open ourselves, calcified and bound to our path, and to feel all of it as we grope in the dark to feel for them. Emhyr’s father might not have gotten it entirely wrong, though his mind at the time was set on making his child an extension of himself. The cycle of death and rebirth begins and ends within that to which we give birth. Giving our children a chance before it is too late, we also give a chance to ourselves. By finding it in his heart to extend to his daughter the courtesy his father Fergus never extended to him - by letting Ciri free - Emhyr lets the part of himself that has defined his entire life die. His end stops justifying the means. He breaks the cycle on the edge of the precipice to which he has brought them and thus allows for the possibility of new beginnings for himself and for Ciri.

In a sense, False-Cirilla and Emhyr get the ending Ciri and Auberon might have gotten if –

If.

The story of Auberon Muircetach achieves a fundamentally different resolution.

‘What does the spear with the bloody blade mean? Why does the King with the lanced thigh suffer and what does it mean? What is the meaning of the maiden in white carrying a grail, a silver bowl—?’

- Galahad

Lady of the Lake

Galahad asks the questions that the innocent Perceval in his Story of the Grail failed to ask, thus losing his chance at freeing the Fisher King from his curse. And the Fisher King is the guardian of mysteries, among them the Holy Grail. But it is not because of gain that a chivalric knight with a shining sword should seek to free the Fisher King from his curse, but rather because it is a human thing to do. Sapkowski claims to be partial to Wolfram von Eschenbach’s rendition of the Grail myth in Parsifal. Wolfram’s message, according to Sapkowski, is the following:

‘Let's not wait for the revelation and the command that comes from above, let's not wait for any Deus vult. Let's look for the grail in ourselves. Because the Grail is nobility, it is the love of a neighbor, it is an ability for compassion. Real chivalric ideals, towards which it is worth looking for the right path, cutting through the wild forest, where, as they quote, "there is no road, no path". Everyone has to find their path on their own. But it is not true that there is only one path. There are many of them. Infinitely many. … Being human is important. Heart.’

‘I prefer the humanism of Wolfram von Eschenbach and Terry Gilliam from the idiosyncrasies of bitter Cistercian scribes and Bernard of Clairvaux...’

- A. Sapkowski

Swiat króla Artura: Maladie

The unimaginable sadness in Auberon’s eyes belies the suffering of the Alder King who is the avatar of the Fisher King. In the Witcher’s story between elves and humans, it is the elven males who all share aspects of the Fisher King’s fate, because they are the keepers of their Grail – the protectors of elven women. Auberon’s wound is wrought by time: by surviving his wife and daughter, by the witnessing of the fading of his ambitions and the results of pursuing them without success. He has lost his line. The Fisher King’s injury represents the inability to produce an heir. A ruler who is the protector and physical embodiment of his land, yet remains barren, sterile, or without a true-born successor, bodes ill for the realm. The Alder King’s injury consists in having lost control of the source of his people’s power, leaving the elves imprisoned and scattered across two worlds. Auberon’s personal tragedy, however, subsists in the lost power having been functionally manifest in a daughter.

‘Lara.’ The Alder King moved his head, and touched his neck as though his royal torc’h was garrotting him. ‘Caemm a me, luned. Come to me, daughter. Caemm a me, elaine.’

Ciri sensed death in his breath.

- Lady of the Lake

Elder Blood is indeed an accursed blood because it enslaves its carriers to its purpose. Emhyr has a theoretical chance to walk away from the pursuit of earthly power; the construct is social. Elder Blood, however, has a particular and real, magical function, and in virtue of being a genetic mutation it is embedded in the gene-carrying individuals. Functionally, Elder Blood allows to shape fate with degrees of freedom unimaginable for an ordinary individual. It’s a difference comparable to the one between a character in a story and the story’s author. Therefore the Aen Saevherne – the carriers of the gene – are bound to the thing they carry within their DNA that allows them to a greater and lesser degree shape the fate of reality. However dearly Auberon, or Lara, might have ever wished to untie themselves from their own essence, it seems impossible. The loss of control over power then is quite simply so pivotal as to necessitate a moment of original sin.

As already witnessed by way of the legend of the Winter Queen, the original “myths” of the Witcher world usually originate among elves; humans, the interlopers, push themselves into those myths only later. This creates an interesting conundrum. In Parsifal, the Fisher King is injured as punishment for taking a wife who is not meant for him. A Grail keeper is to marry the woman the Grail determines for him, which – if we equate woman with the Grail – is what the woman determines. Unfortunately, we know nothing about Shiadhal, so we cannot verify if this part of the legend dovetails. But generally, in a wholly elven world which may have matriarchal tendencies, in lieu of worshipping the mother Goddess, such cosmology is relatively unproblematic. Except suddenly there are humans too. And Auberon – the highest leader of elves and the father of the new scion of Elder Blood – is indirectly injured because a human sorcerer – Cregennan – turns himself into a Grail keeper (in place of another, special elf) by taking a woman not meant for him.

‘Witcher,’ she whispered, kissing his cheek, ‘there’s no romance in you. And I… I like elven legends, they are so captivating. What a pity humans don’t have any legends like that. Perhaps one day they will? Perhaps they’ll create some? But what would human legends deal with? All around, wherever one looks, there’s greyness and dullness. Even things which begin beautifully lead swiftly to boredom and dreariness, to that human ritual, that wearisome rhythm called life.’

- Yennefer

Sword of Destiny

Cregennan’s injury is to die. But what about the original Fisher King figure? What is Auberon’s original sin in this?

I see two possibilities. It could be that Auberon in his ambition hastened his daughter’s way into exile and, in a display of his displeasure, never made any effort to ease his daughter in to the personal sacrifices they, as Aen Saevherne, must make; walking without blinking to the end of the path Emhyr turned away from. It could equally be that Auberon, instead of locking Lara up in a tower to protect her from the folly of youth, let her go to Cregennan. It could be an amalgam of both, and the misjudgement of a father who allows freedom, who feels for his child, and is rewarded with an irreversible injury is probably the greater tragedy.

Because, regardless of the origin of the curse upon Auberon, one thing does not change – the icy eternity in the Alder King’s heart never fractures.

‘‘Zireael,’ he said. ‘Loc’hlaith. You are indeed destiny, O Lady of the Lake. Mine too, as it transpires.’

- Auberon

Lady of the Lake

Ciri passes through the shadow world of the Alders; a manifestation of fate. Her footsteps sowing discord and movement and change into the immutable, time-locked amber of the elven utopia. Her presence providing the trigger that will unshackle the past from future in a world where for a long time nothing has changed, died, or been reborn. She is destined and destiny, annihilation and rebirth, the grain of sand in the gears of the great mechanism; a strange girl. The child of hope and the Goddess who ought to be Three. Lara, the true daughter of the Alder King, is dead. Emhyr’s daughter still lives. There is nothing Auberon can do for Lara anymore and thus the ice in Auberon’s heart has crystallised. Emhyr still has a chance; he is where Auberon once was. And yet, there is one thing Ciri, the witcher girl with a sword of her own, can still do for the Alder King.

‘Va’esse deireadh aep eigean… But,’ he finished with a sigh, ‘it’s good that something is beginning.’

They heard a long-drawn-out peal of thunder outside the window. The storm was still far away. But it was approaching fast.

‘In spite of everything,’ he said, ‘I very much don’t want to die, Zireael. And I’m so sorry that I must. Who’d have thought it? I thought I wouldn’t regret it. I’ve lived long, I’ve experienced everything. I’ve become bored with everything … but nonetheless I feel regret. And do you know what else? Come closer. I’ll tell you in confidence. Let it be our secret.’

She bent forward.

‘I’m afraid,’ he whispered.

‘I know.’

‘Are you with me?’

‘Yes, I am.’

- Auberon

Lady of the Lake

The only way Ciri the Grail knight will be able to find her true self – the Grail – is to cure the suffering Alder King from his curse. Ciri’s presence in the world of the Alders is after all also part of her coming of age story. Through becoming Auberon’s destiny, Ciri must close the circle for him and bring closure. He would never let her go because the shard in Auberon’s heart is no longer able to melt. Auberon does not follow the motif of alleviating the suffering of one’s blood and/or love; and he dies. The roles are reversed, in fact. It is Ciri who realises Auberon is suffering. So Ciri must do what only she can do, because remaining human is important. Heart is important. The sacrifice a ruler makes on the altar of power includes his own heart, which is why there should never be only one, but always two; always.

‘Time is like the ancient Ouroboros. Time is fleeting moments, grains of sand passing through an hourglass. Time is the moments and events we so readily try to measure. But the ancient Ouroboros reminds us that in every moment, in every instant, in every event, is hidden the past, the present and the future. Eternity is hidden in every moment. Every departure is at once a return, every farewell is a greeting, every return is a parting. Everything is simultaneously a beginning and an end.

‘And you too,’ he said, not looking at her at all, ‘are at once the beginning and the end. And because we are discussing destiny, know that it is precisely your destiny. To be the beginning and the end. Do you understand?’

She hesitated for a moment. But his glowing eyes forced her to answer.

‘I do.’

- Lady of the Lake

Death Crone to Auberon Muircetach, Ciri never becomes the Mother Goddess in the Saga. It is a choice she must make for herself and the choice still lies ahead of her. The predicate to making such a choice at least for now, however, she achieves; she goes her own way. In a sense then, both rulers are father figures, who through their choices “beget” the child who is destined. Perhaps this too the Knowing Ones knew, and for this reason Auberon never could have budged, never could have changed his mind in regard to his purpose in the long and winding story of his life. Something is ending, but something is also beginning. A good ruler is responsible for the flourishing of their realm, for providing hope. It is Ciri’s role to be the beginning and the end, and though there might be ways in which to nudge the hand of Fate, whatever is destined must happen. Destiny, however accursed, must run its course.

That is the hope and the release.

---

If you like my writing, consider buying me a coffee.

Thanks! ❤️

#wiedźmin#the witcher#andrzej sapkowski#the witcher lore#the witcher meta#analysis#auberon muircetach#emhyr var emreis#cirilla fiona elen riannon#ciri#aen elle#nilfgaard#arthurian legend#arthuriana#Swiat Krola Artura#wicca#celtic mythology#history of the british isles#elder blood#lara dorren#fisher king#snow queen#fairy tales#longform#writing#false-cirilla#tw: inc*st#aen saevherne#ithlinne's prophecy#winter queen

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los necrogólems son constructos nigrománticos, cuyas venas artificiales constantemente bombean excidio, es decir, almas en pena diluídas en un líquido maldito y corrosivo. Las venas son una mezcla de baratrio y tejido conjuntivo laxo, con inscripciones rúnicas eranoristas para evitar que el excidio las destruya. El excidio debe ser reemplazado cada cierto tiempo, razón por la cual suelen venir con cilindros metálicos soldados a sus espaldas donde el excidio usado es removido y reemplazado.

Estos aborrecibles quimeras se componen de los tejidos y órganos de múltiples cadáveres, quienes son reanimados gracias a las propiedades impuras del flujo que las potencia. Además, los necrogólems son protegidos por una armadura orgánica compuesta de capas sobre capas de costras y formaciones cutáneas necróticas, las cuales, por su contacto con el excidio, toman un color negrestino. Sus cuerpos tienden a ser protegidos por pesadas armaduras de aleaciones impuras fabricadas bajo las Grietas del Abismo, y sus torsos conectan con sus extremidades a través de fascículos musculares oscuros y aislados, los cuales no son compactados ni juntados por el actuar de un epimisio. La falta de este tejido conjuntivo hace que los fascículos aparenten tentáculos que conectan con sus brazos.

Además de su dantesca y funeraria estructura quimérica, los necrogólems poseen un cráneo apenas cubierto en tejido como cabeza, el cual también es unido a su torso por un cuello de fascículos musculares separados y que es protegido por un largo gorjal de baratrio.

Leer más.

#rpg#foroactivo#rol#roleplay#dark fantasy#dieselpunk#foro#decopunk#trenchpunk#ambientación#horror fantasy#pbp español#pbp hispano#rol español#rol hispano

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

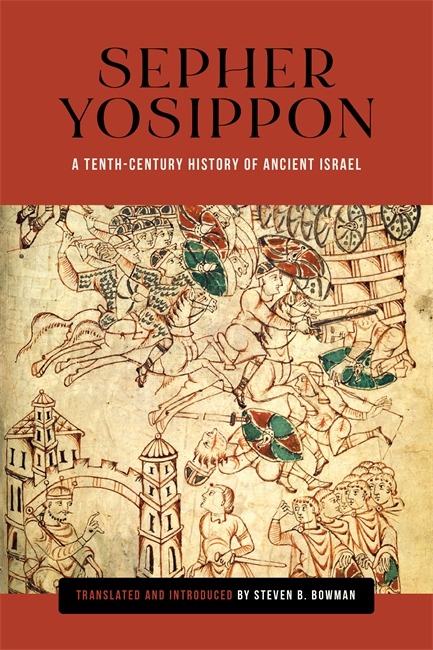

Book Review | Sepher Yosippon: A Tenth-Century History of Ancient Israel, translated by Steven B. Bowman

As the title suggests, this is a new modern English translation of the Sepher Yosippon, the 10th century work of Jewish history which was extremely popular in the medieval and early modern periods. It follows Jewish history from biblical times, when Noah and his sons repopulated the earth after the great flood, to the destruction of the Second Temple and the Battle of Masada. I initially decided to read it after it kept coming up in readings for my Jewish Studies class this past semester. Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi referred to it in Zakhor as the only major historical work written by Jews in the Middle Ages, discussing it in opposition to other ritualized forms of remembrance, such as piyyutim.

Whether or not Sepher Yosippon is entirely unique in terms of medieval history is debatable, but one can see why it holds up to Yerushalmi’s standards of history writing more so than other medieval works. The anonymous author—originally incorrectly assumed to be Josephus, hence the name of the work—was meticulous in his use of historical sources. One particularly interesting thing about his use of sources is that he cites Christian writers as much, if not more, than he cites Jewish ones: two of his main sources are the writings of Jerome and an earlier medieval work called De excidio urbis Hierosolymitae, a Christian polemic which asserted that the destruction of the Second Temple was the Jews’ fault. The author of Sepher Yosippon kept the more neutral historical details from these works, while removing the explicitly antisemitic ones to craft a narrative that was more forgiving to Jews.

Bowman’s translation is based on the critical edition of the Hebrew text published by David Flusser in the 20th century. My Hebrew is not good enough to read the whole text in the original, so I cannot comment on Bowman’s translation in that regard. What I can say is that the text is accompanied by copious translator’s notes, presented in the form of footnotes which explain certain translation choices and note the source texts for various passages. This latter detail I found particularly helpful for my own work in tracing the movement of ideas between medieval Christian and Jewish historians. Overall, I would say that I do recommend this text to anyone interested in medieval historiography. It is a fascinating insight into how Jews were thinking about their own history in the Middle Ages.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gildas

Gildas (c. 500-570) était un moine romano-britannique, connu principalement pour un ouvrage intitulé De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, traduit par Sur la ruine et la conquête de la Grande-Bretagne. L'œuvre de Gildas est un sermon polémique relatant l'histoire britannique tout en réprimandant les rois et le clergé britanniques de son vivant. Bien que l'on sache peu de choses sur Gildas lui-même, il est généralement admis qu'il écrivait vers le milieu du VIe siècle. Il vécut probablement près de l'ouest de la Grande-Bretagne, dans les régions actuelles du Pays de Galles et de la Cornouailles. Plus tard dans sa vie, il émigra en Bretagne, dans le nord-ouest de la France. Il y rejoignit nombre de ses compatriotes bretons qui fuyaient les envahisseurs germaniques. Gildas y fonda le monastère connu sous le nom de St. Gildas de Rhuys et fut vénéré comme un saint, parfois appelé Saint Gildas Sapiens ou Saint Gildas le Sage.

Lire la suite...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (January 29)

St. Gildas was probably born around 517 in the North of England or Wales.

His father's name was Cau (or Nau) and came from noble lineage. He most likely had several brothers and sisters.

There was a writing that suggested that one of his brothers, Cuil (or Hueil), was killed by King Arthur (who died in 537 AD).

It also appears that Gildas may have forgiven Arthur for this.

There are two accounts of the life of St. Gildas the Wise, neither of which tell the same story.

He lived in a time when the glory of Rome had faded from Britain. The permanent legions had been withdrawn by Maximus, who used them to sack Rome and make himself Emperor.

Gildas was noted in particular for his piety and good education. He was not afraid to publicly rebuke contemporary monarchs at a time when libel was answered by a sword rather than a court order.

Gildas lived for many years as a very ascetic hermit on Flatholm Island in the Bristol Channel.

There, he established his reputation for that peculiar Celtic sort of holiness that consisted of extreme self-denial and isolation.

At around this time, according to the Welsh, he also preached to Nemata, the mother of St. David, while she was pregnant with the saint.

In about 547, he wrote a book De Excidio Britanniae (The Destruction of Britain).

In this, he wrote a brief tale of the island from pre-Roman times. He criticized the rulers of the island for their lax morals and blamed their sins (and those that follow them) for the destruction of civilization in Britain.

The book was avowedly written as a moral tale.

He also wrote a longer work, the Epistle, which was a series of sermons on the moral laxity of rulers and of the clergy. Gildas proved that he was well read in the Bible and some other classic works.

He was also a very influential preacher. Because of his visits to Ireland and the great missionary work he did there, he was responsible for the conversion of many on the island.

He may be the one who introduced anchorite customs to the monks of that land.

From there, he retired from Llancarfan to Rhuys in Brittany, where he founded a monastery.

Of his works on the running of a monastery (one of the earliest known in the Christian Church), only the so-called Penitential, a guide for Abbots in setting punishment, survives.

He died in Rhuys at around 571.

He is regarded as one of the most influential figures of the early English Church.

The influence of his writing was felt until the middle ages, particularly in the Celtic Church.

He is also important to us today as the first British writer whose works have survived fairly intact.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

First impressions of Arthurian lore, part 2 (again copied from my Facebook posts because I only just started using Tumblr again, this one’s from Nov 25th):

Reading up on Arthurian legend, and…

There are surprisingly few resources of any kind out there on the development of the stories themselves. No books for public consumption, just expensive textbooks and research papers.

Plenty of books retelling the legends in one way or another. Plenty of books on ”who was the real King Arthur / where is the real Camelot” etc, trying to determine historical basis for the stories. Some pagany stuff deriving spirituality and magic from Arthurian lore.

But way fewer other resources than I expected.

And my (rather advanced, thank you) Google skills failed to find me a recommendations list for translations of the various source texts. Which just seems strange. Do people just not engage with the source material with Arthurian legend? Is it just endless derivations and fanfic of fanfic of fanfic? This is not bad, this is fascinating, but it’s also very weird to me.

(More recently, since originally writing this, I have learned that people are still engaging with the source material, but it’s apparently just “10 gay people on Tumblr” doing so, to quote oldtvandcomics.)

And way fewer Facebook groups than I expected. I found one, the Arthurian Society, which I finally posted to asking for translation recommendations and resource recommendations. They were very very helpful.

(Note: More recently I have discovered that apparently the place for resources on getting started with Arthurian lit is Tumblr, of all places.)

It looks like the Camelot Project will be where I exist from now on while I’m in this hyperfocus. I’ve barely scratched the surface of it but it’s already super helpful.

I was resisting the urge to make the resource I’m looking for, a timeline of what characters and lore elements were developed when and by whom. I’m going to take notes as I read through the source material and try to make it for myself, whether or not I share it publicly in any form. I begin to see why people haven’t done so, though, as it is *complex*.

So what do I read first? I want to start at the beginning. But that’s harder to figure out than you might think.

At the start, we’ve got 1138, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain. That’s the true “beginning” of Arthurian literature.

But if we want to look back further, Geoffrey’s sources were Gildas's sixth century De Excidio Brittaniae (On the Ruin of Britain) and Nennius's ninth century Historia Brittonum (History of the Britons). Gildas gave us Vortigern and Aurelius Ambrosius. Nennius gave us Saxon chieftains Hengest and Horsa, was the first to mention "Arthur the soldier," the "dux bellorum" (leader of battles), and also gives us a fellow named Ambrosius, who uncovers two fighting dragons under the foundation of his tower and prophesies the political future of Britain (sound familiar? Geoffrey incorporates him into the History as “Merlin Ambrosius”). Plus probably a bunch of Welsh material that Geoffrey never cites, for more on Merlin and Arthur.

Resources before Geoffrey are just brief mentions of Arthur. Merlin, on the other hand, has a wealth of pre-Galfridian material.

In addition to the History, Geoffrey also wrote two pieces about Merlin: Prophetiae Merlini (which was used for long afterwards by British politics in the same way as people have referenced Nostradamus, to attempt to predict or legitimize political events by saying it was predicted by Prophetiae Merlini), and Vita Merlini, a poem about Merlin’s life.

There’s Merlin Ambrosius of Nennius’s writing, and then there’s the Myrddin of early Welsh poetry. He gets called Merlin Silverstar at times to differentiate from Merlin Ambrosius, though you might have guessed that the two got merged into one figure pretty quick, the Merlin we now know of in modern Arthurian lore.

Then there are these six Welsh poems. The manuscripts that the poems are found in post-date Vita Merlini by over 100 years, but Welsh linguists have used orthographic evidence to show that the poems themselves are decidedly older than the manuscript, and may predate Geoffrey’s work as a result.

The poems are “Yr Afallennau" (The Apple Trees), "Yr Oianau" (The Greetings), "Ymddiddan Myrddin a Thaliesin" (The Dialogue of Myrddin and Taliesin), "Cyfoesi Myrddin a Gwenddydd ei Chwaer" (The Conversation of Myrddin and his Sister Gwenddydd), "Gwasgargerdd Fyrddin yn y Bedd" (The Diffused Song of Myrddin in the Grave), and "Peirian Faban" (Commanding Youth).

(When we say “poems” in this period of literature, we’re talking stuff like Beowulf. Novella length stuff. 50, 100 pages of lengthy lines and the like. So these are small books in their own right.)

And then of course there’s the Mabinogion, which was compiled into a manuscript much later than Geoffrey’s time but comes from earlier Welsh oral traditions which likely predate Geoffrey. There are apparently elements of the Mabinogion that are in Arthurian legends.

So do I start with the Mabinogion? The six Welsh poems about Merlin? Nennius and Gildas? Or Geoffrey of Monmouth?

Probably gonna start with Geoffrey, because it’s easy enough to find, and in fact free on the Camelot Project (though the formatting may drive me mad and lead me to get an ebook translation, apparently the Penguin Classics version is perfectly fine.

#arthurian literature#arthuriana#Arthurian newbie#arthurian lore#arthurian mythology#seriously how are there so few resources on this

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the tl;dr of my thought train over the past week:

(and technically those are 3 images of Gildas on the right but I figured the fact that the depictions were wildly different only furthered my point)

Roshambo & Gildas,,, identical to the point of suspicion,,, 👀

#lssmp#Lifesteal SMP#Roshambo#Ro Roshambo Games#RoshamboGames#Gildas#De Excidio#my very real and super serious conspiracy theory#Gildas theory

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read All the Arthurian Literature!

I was originally going to do this chronologically, but after pulling the enormous list of classic texts from @fuckyeaharthuriana's Arthurian List of Everything, I quickly abandoned that idea.

Instead, I'm going to start with the "core texts" in chronological order... more or less. I'll fill in the remaining literature over time if I stick with this project long enough. Core texts are bolded. These are the very influential, foundational texts that Arthurian literature built on over time, and that modern Arthuriana derives from. (What's a "core text" is debatable; I'm bolding the texts that I've most often seen recommended across the internet.)

This is my tracking sheet for what I've acquired, what I've read, and what I have left to read, with a link to the tag associated with that text where you can find my reactions, thoughts, and quotes from the text. Currently a shortlist, with additional texts from the complete list added in as I read them.

✓ 540 - Excerpt from De Excidio Britanniae / The Ruin of Britain, by Gildas. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of De Excidio Britanniae, by Gildas. (Probably not going to bother with this.)

✓ 600 - Y Gododdin. Translated by Gillian Clarke

✓ 828 - Excerpt from Historia Brittonum, by pseudo-Nennius. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of Historia Brittonum, by Nennius. (Probably not going to bother reading this.)

□ 1000-1185 - The Lives of Saints (various saints with Arthurian content in their stories) - This is not what I'd call a core text, I'll probably skip most of them for now, but I already read excerpts in Faletra's appendices and I wanted credit for it.

□ 1000 - Life of St. Illtud

□ 1000 - Life of St. Cadoc, by Lifras of Llancarfan

□ 1019 - Legenda Sancti Goeznovii (Arthur is mentioned as being "recalled from the actions of the world" and not much more, probably skippable)

□ 1100 - Life of St. Padarn (only a brief mention of Arthur and Caradoc, probably skippable)

□ 1100 - Life of St. Efflam

✓ 1130 Excerpt from Vita Gildae / Life of St Gildas, by Caradoc. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of Vita Gildae / Life of St Gildas. Translated by Hugh Williams because it's literally the only one I can find.

□ 1185 - The Life of Kentigern, by Jocelyn of Furness

✓ 1100 - The Lais of Marie de France. Translated by Claire Waters (newest recommended translation I could find, from 2018 by Broadview Press which was the selling point for me because they're amazing; has translation on one page and the old French on the other).

✓ 1138 - Historia regum Britanniae / History of the Kings of Britain, by Geoffrey of Monmouth. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

✓ 1125 - Excerpt from Gesta Regum Anglorum / The Deeds of the Kings of the English by William of Malmesbury. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of Gesta Regum Anglorum, by William of Malmesbury. (Probably not going to bother reading this.)

✓ 1150 - Vita Merlini / Life of Merlin, by Geoffrey of Monmouth. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ 1155 - Roman de Brut, by Wace. (Might skip this, not sure.)

□ 1170 - Tristan, by Thomas of England

□ 1170-81 - Romances of Chretien de Troyes

□ 1170 - Erec and Enide. Translated by Ruth Harwood Cline (the only one who's done verse translation instead of prose). Started reading it and then had to skip to Vulgate for a writing project.

□ 1176 - Cliges. Translated by Ruth Harwood Cline

□ 1177 - Lancelot: the Knight of the Cart. Translated by Ruth Harwood Cline