#College Football Hall of Fame

Text

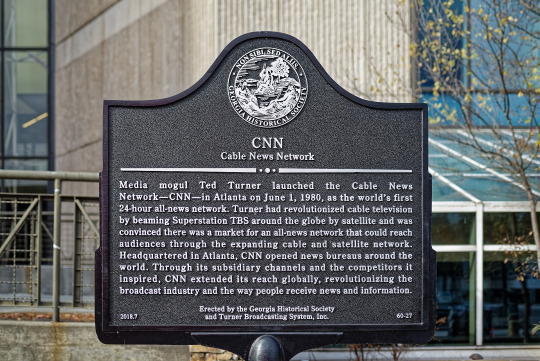

CNN HQ looks like a ghost town now, with nearby attractions facing similar wintery reception from post COVID visitors.

#CNN#Coca Cola#Pemberton Place#College Football Hall of Fame#Atlanta#Georgia#Nikon Z5#Nikon Studio#Santa Claus#ATL

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bill Kreutzmann Remembers His Grandfather, Football Coach Clark Shaughnessy, Ahead of Super Bowl

- “He was as good at being a grandfather as he was at making football plays,” Grateful Dead co-founder says

Bill Kreutzmann is thinking about his grandfather, college and professional coach Clark Shaughnessy, ahead of today’s Super Bowl between the San Francisco 49ers and the Kansas City Chiefs.

Known as the “father of the T formation,” Shaughnessy is enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame and had 50-year career that saw him coaching Tulane, Stanford, Maryland and other college teams along with the NFL’s Los Angeles Rams, Washington Redskins and Chicago Bears.

“To me, he was just someone I looked up to and enjoyed being around, because he was as good at being a grandfather as he was at making football plays,” the Grateful Dead co-founder and former Dead & Company drummer said.

“And that’s something.”

Kreutzmann continued: “So let’s go ’Niners, and maybe someday you’ll have dancing bears at the halftime show.”

That would be something, too.

2/11/24

#bill kreutzmann#grateful dead#dead & company#clark shaughnessy#college football hall of fame#san fransisco 49ers#kansas city chiefs

0 notes

Text

Reggie Bush

2023 College Football Hall of Fame Inductee

#reggie bush#college football#football hall of fame#black excellence#619#USC#black heisman#heisman trophy#2000s college football#black legend#black sports

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gators legend Tim Tebow joins College Football Hall of Fame

Legendary University of Florida quarterback Tim Tebow was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame Tuesday night during the 65th National Football Foundation Annual Awards Dinner in Las Vegas.

“It means a lot not just for the accolade—which it’s humbling to be in the hall of fame, but it also represents the incredible young men that I got to play with because the special thing about…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Classic Vol Video: ESPN: FBS 1992-Hall of Fame Bowl-Boston Eagles @ Tennessee Volunteers: Full Game

.

The Daily Journal

An interesting coaching matchup with Tom Coughlin of Boston who would later lead the expansion Jacksonville Jaguars to the 1996 NFL Playoffs, including the 1996 AFC Championship and the 1999 AFC Championship. But before Jacksonville, he rebuilt the Boston Eagles football program. That hadn’t been very good at all since Doug Flutie left in 1985. And of course Coughlin goes on…

youtube

View On WordPress

#1993 Hall of Fame Bowl#Boston College Eagles#Boston College Football#College Football#ESPN#Joe Theisman#Mike Patrick#NCAA Football#Tennessee Football#Tennessee Volunteers#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

You can’t take greatness for granted in this life

You can’t take greatness for granted in this life

Former NFL QB Len Dawson passed away recently, a reminder you can’t take greatness for granted in this life. A cornerstone of the Chiefs Super Bowl teams of the ‘60s and 1970s, Dawson went to a pro-Bowl and dominated in an era of far less protection for QBs, and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1987. Len Dawson was a building block for Kansas City football. We are…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Mack Brown, and that big beautiful bulge, at his induction into the College Football Hall of Fame. Mmm...

255 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hii how are you today?

Could you write Millionaire Reiner that is obsessed with his wife and could she be plus-size?

hiiii my sweetness! I absolutely can (and I’m totally not living vicariously or anything)

themes: black plus size reader, fluff and some freaky stuff mentioned

so I am a firm believer that Reiner made his millions off of playing football. He was a star quarterback in the NFL for years, where he won a plethora of championships before retiring. The last thing he wanted to do was be far too broken down to function so he decided to bow out gracefully after ten seasons, five of which were winning Super Bowl ones. He went on to invest his fortune in several different businesses including farming, auto sales and even the cannabis industry. But his true and most priceless passion was his gorgeous wife of ten years, (y/n) (l/n). A woman who had been by his side since his high school and D1 days back in college. A stunning and equally smart young lady; a pathology major with a minor in physical therapy, whom he first met in his math class after getting your help to pass an exam. He was equally smitten then as he was now. Infatuated with your intelligence and looks, Reiner didn’t stop until you were his and it didn’t take much because you were crushing hard on the shy ball player. Many people would say that the two of you brought the best out of another, including your shells. When you were around, he never stopped smiling and when he was away at games, interviews..he couldn’t wait to get back! Now the two of you spend your days traveling the world, working on the farm and enjoying the perks of married life that you missed out on during his glory days. Picking up and taking trips, being spoiled endlessly and just showered in love and praise by your man. Your walk in closet looks like an entire boutique, your fashion sense is envied and all you have to do is bat those pretty eyelashes and he opens his wallet. He gets so happy to brag on you, tell everyone how amazing you are and that you are his entire world. Reiner is so in love with you, constantly posting you to his Instagram and showing off his girl! Granted, as a bigger woman, people have had their fair share of nasty insults, but none of them compare to the love that you receive for how hot of a couple you are. You’re so spoiled, it makes no sense.

or the even nastier things he does with you! When you’re on vacation, strutting around in your bikini with those thick thighs, tummy (stretch marks and all baby!) he gets so excited. Like big daddy can barely even contain himself (side note: he posts you with the vaguest yet freakiest caption, saying things like ‘my meal’ or ‘my beard warmer’. He definitely whisks you away from all those fancy dinners and hall of fame ceremonies to eat you out in the front seat of his McLaren or Maserati. Plunging those fingers right to the brunt of his championship rings. Laying his forehead against the fat of your tummy and devouring that pussy until you’re shaking. Keeping this man off of you is a full time job in and of itself but you don’t mind it at all because lord is he down bad when it comes to you and the feeling is mutual. Y’all will go rounds until neither of you can stand and the obsession grows more and more each day.

#cherry’s asks 🍒#aot x black reader#black fem reader#reiner aot#reiner x chubby black reader#black reader#shingeki no kyojin reiner#reiner headcanons#reiner braun#reiner x black fem reader#reiner smut#attack on titan reiner#reiner imagine#reiner braun x black reader#snk reiner#black reader smut#reiner x reader#reiner braun x reader#reiner brainrot#aot reiner#need to fuck on him on an island

782 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bobby Bowden

Physique: Average Build

Height: 5'9"

Robert Cleckler Bowden (November 8, 1929 – August 8, 2021) was an American college football coach. Bowden coached the Florida State Seminoles of Florida State University (FSU) from 1976 to 2009 and is considered one of the greatest college football coaches of all time for his accomplishments with the Seminoles. Bowden was first among active coaches for winning percentage in bowl games at the time of his retirement, and is currently second for all-time bowl wins and second for bowl appearances.

The beloved Hall of Fame coach led FSU to an National Title in 1993 and a BCS National Championship in 1999, as well as 12 ACC championships. But fuck that shit! He was sexy southern guy who is just adorable at any time in his coaching career that got me giddy. Giddy? Yeah I said giddy.

The beloved, folksy Hall of Fame coach led FSU to an National Title in 1993 and a BCS National Championship in 1999, as well as 12 ACC championships. But fuck that shit! He was sexy southern guy who is just adorable at any time in his coaching career that got me giddy. Giddy? Yeah I said giddy. A devout Christian, Bowden didn’t smoke or drink, and “dadgummit” seemed the sharpest word in his vocabulary. Which some how makes him hotter to me.

Sadly, passed away Aug. 8, 2021 at the age of 91, after a battle with cancer. The Birmingham, AL native and his wife had six children, including two who became college football coaches, former Clemson coach Tommy Bowden and current University of Louisiana at Monroe coach Terry Bowden. I would probably toss a dick to all four of his sons, particularly Terry. Good genes I guess.

But back in the 90s, DAMN Bobby was scorching hot and I would have loved to make him cum. Accept his Christian faith wouldn't have allowed that. But I could dream.

Head Coaching Record

Overall 377–129–4

Bowls 21–10–1

Accomplishments and Honors

Championships

2 National (1993, 1999), 12 ACC (1992–2000, 2002–2003, 2005), 2 ACC Atlantic Division (2005, 2008)

Awards: Bobby Dodd COY (1980), Walter Camp Coach of the Year Award (1991), Amos Alonzo Stagg Award (2011)

College Football Hall of Fame

Inducted in 2006 (profile)

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

100th Bomber Boys: Major Robert 'Rosie' Rosenthal: Pt. 1

Ahead of the show's release, I bought Donald Miller's book and am reading it! Here is a little bit about Major Robert 'Rosie' Rosenthal (played by Nate Mann) from the prologue of Masters of the Air (pg. 13-14)!

Lt. Robert "Rosie" Rosenthal had not trained with the Hundredth's original crews. He and his crew had been assigned to the group that August from a replacement pool in England, to fill in for men lost on the Regens-burg raid. "When I arrived, the group was not well organized," Rosenthal recalled. "They were a rowdy outfit, filled with characters. Chick Harding was a wonderful guy, but he didn't enforce tight discipline on the ground orin the air."

Rosenthal didn't fly a mission for thirty days. "No one came around to check me out and approve me for combat duty. Finally, my squadron commander, John Egan, had me fly a practice formation. I flew to the right of his plane. I had done a lot of formation flying in training and I was frustrated; I desperately wanted to get into the war. I put the wing of my plane right up against Egan's, and wherever he went, I went. When we landed, Egan told me he wanted me to be his wing man."

Rosenthal had gone to Brooklyn College, not far from his Flatbush home. An outstanding athlete, he had been captain of the football and baseball teams, and later was inducted into the college's athletic hall of fame. After graduating summa cum laude from Brooklyn Law School, he went to work for a leading Manhattan law firm. He was just getting started in his new job when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The next morning he joined the Army Air Corps.

He was twenty-six years old, with broad shoulders, sharply cut features, and dark curly hair. A big-city boy who loved hot jazz, he walked, incongruously, with the shambling gait of a farmer, his toes turned inward and there wasn't an ounce of New York cynicism in him. He was shy and easily embarrassed, but he burned with determination. "I had read Mein Kampf in college and had seen the newsreels of the big Nazi rallies in Nuremberg, with Hitler riding in an open car and the crowds cheering wildly. It was the faces in the crowd that struck me, the looks of adoration. It wasn't just Hitler. The entire nation had gone mad; it had to be stopped.

"I'm a Jew, but it wasn't just that. Hitler was a menace to decent people everywhere. I was also tremendously proud of the English. They stood alone against the Nazis during the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. I read the papers avidly for war news and listened to Edward R. Murrow's live radio broadcasts of the bombing of London. I couldn't wait to get over there.

"When I finally arrived, I thought I was at the center of the world, the place where the democracies were gathering to defeat the Nazis. I was right where I wanted to be."

Rosie Rosenthal didn't share these thoughts with his crewmates, simple guys who distrusted what they called deep thinking. They never learned what was inside him, what made him fly and fight with blazing resolve.

Later in the war, when he became one of the most decorated and famous fliers in the Eighth, word spread around Thorpe Abbotts that his family was in a German concentration camp. But when someone asked him directly, he said "that was a lot of hooey." His family-mother, sister, brother-in-law, and niece (his father had recently died) were all back in Brooklyn.

"I have no personal reasons. Everything I've done or hope to do is strictly because I hate persecution... A human being has to look out for other human beings or else there's no civilization."

Rosie was part of the 'Bloody 100th' Bombardment Group of the 13th Combat Wing, of the 'Mighty Eighth' Air Force with John 'Bucky' Egan and Gale 'Buck' Cleven (played by Callum Turner and Austin Butler) His plane was called Rosie's Riveters, and him and his crew were an integral part of the bombardment group.

On October 8th, 1943, the 100th went on a bombing run to Bremen, Germany, and Buck Cleven was shot down. Two days later, Egan and the rest of the 100th went on a supposedly "easy" mission to Münster, accompanied by P-47 Thunderbolts almost all the way to the target. Rosenthal and his crew were not flying their beloved Rosie's Riveters due to damage from their two previous missions in Bremen and Marienburg. Instead, they flew Royal Flush.

Rosie's crew was worried about flying a brand new plane, and became incredibly nervous. Bringing them together under one of the wings, he calmed the boys down and lifted their spirits. This mission proved disastrous, and Royal Flush was the only one in the 100th to make it back to Thorpe Abbotts (the 100th's air-base in East Anglia).

Needless to say, I love Rosie already!! I've read up to chapter 6, and I feel like my brain is going to explode with all the information I've taken in :3

lmk if y'all want more posts like this one or would like to be tagged in them!!

#thank you for coming to my TED Talk#this is for everyone who doesn't have access to the book but wants more info on the guys!!!#can you tell i'm a history major??#masters of the air book excerpts#hbo war#bloody hundredth#100 bombardment group#major john egan#donald miller#major robert rosie rosenthal#masters of the air#major gale cleven

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

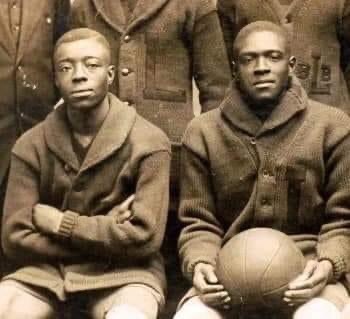

‘Pimp’ and ‘Lyss’: The Immortal Young Brothers by Claude Johnson (Black Fives Foundation)

They were brothers on and off the court. William Pennington Young, sometimes known as “Pimp” to his friends, and his older brother Ulysses S. Young, known simply as “Lyss” to his pals, were an unstoppable sibling pair of African American basketball stars that played during the 1910s and early 1920s.

They also made significant pioneering contributions off the court, long after their playing days ended.

Ulysses was born in Virginia in 1894. A year later, after his hard working parents migrated tot he North in pursuit of a better life, younger brother William was born in Orange, New Jersey.

A few years later, in 1900, their parents rented a room of their home to a young couple from Virginia, the Ricks family, who had a newborn son named James. Over the years the Young brothers embraced little James as if he were their own kin, and as the older boys got involved in sports, so did their protégé.

Something in that combined household created serious athletic skills.

Lyss and William attended nearby Orange High School, where they starred in football, basketball, and baseball. In 1910, while still in high school, the pair began playing semi-pro basketball for the Imperial Athletic Club, a local squad that competed against such teams as the Newark Strollers, the Montclair Athletic Club, and the Jersey City Colored YMCA. The two immediately received attention in the black sports press, including the popular and nationally circulated New York Age.

Their attraction to basketball got young James hooked on the sport too, and he soon developed his own talent. One huge advantage was having the opportunity to learn from- and train with the Young brothers.

The little basketball apprentice, James Ricks, would grow up to become James “Pappy” Ricks, who would become a founding member of the New York Renaissance Big Five professional basketball team and eventually reach the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

After high school, the Young brothers attended Lincoln University in West Chester, Pennsylvania, which was not only America’s oldest historically black university but also was the closest to home for them. In college they both were once again three-sport stars. Though the brothers excelled in each sport, their first claim to fame was through football.

Playing quarterback, William was named as a Negro All-American during his senior year. Ulysses, playing end, was named to the Milton Roberts All Time Black College Football Squad for the 1910s Decade.

After graduating from Lincoln (“Pimp” was class valedictorian in 1917), the Youngs were recruited to play professional basketball in Pittsburgh by prominent African American sports promoter Cumberland Posey. Posey, historian Rob Ruck wrote in Sandlot Seasons, his landmark book that explores the city’s unique athletic heritage, “was,as much as any one man could be, the architect of sport in black Pittsburgh.”

The pioneering promoter had been cultivating Pittsburgh’s black basketball talent through his operation of several different squads in the city, most prominently the Monticello Athletic Association, since the early 1910s. But with America’s imminent entry into World War I and the resulting lack of resources, Posey decided to consolidate his best talent into one powerfully built team.

The result was the Loendi Big Five, a legendary combo that was sponsored and got its name from the Loendi Social & Literary Club, an exclusive African American social club in the the city’s predominantly black Hill District.

1921.

Adding the collegiate superstars from Lincoln not only helped Posey promote his new team but also sparked the Loendi Big Five’s domination of black basketball, with a dynasty that included four straight Colored Basketball World Championships from 1919 through 1923.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

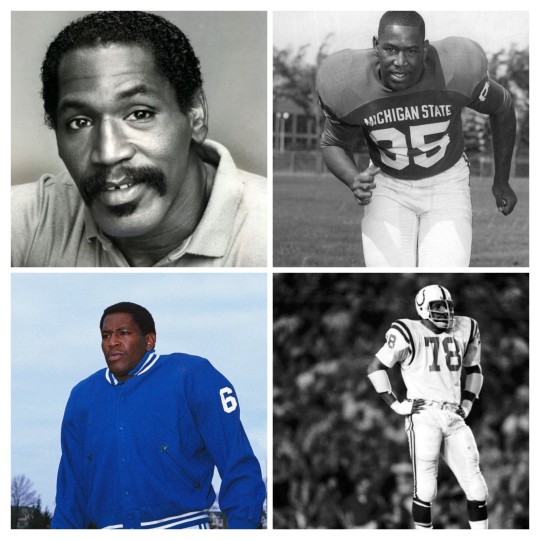

Charles Aaron "Bubba" Smith (February 28, 1945 – August 3, 2011) was an American football defensive end and actor. He first came into prominence at Michigan State University, where he twice earned All-American honors on the Spartans football team. Smith had a major role in a 10–10 tie against Notre Dame in 1966 that was billed as "The Game of the Century". He is one of only six players to have his jersey number retired by the program. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1988.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Travis Kelce Opens Up About Taylor Swift and What Comes Next

Wall Street Journal - Travis Kelce full article under the cut

A few months ago, he was merely football famous. Now Travis Kelce is ready to tell his story. ‘I’ve never dated anyone with that kind of aura about them.’

By J.R. Moehringer

WHEN TRAVIS KELCE was a young man, his college football coach pulled him aside one day and told him the secret of life: Everybody you meet in this world is either a fountain or a drain.

“I need fountains,” the coach growled at Kelce. “I don’t need f—ing drains. Travis, you’re f—ing draaaining me!”

The advice left a deep impression. (“Changed his life,” says one of Kelce’s closest friends.) Yes, Kelce thought—you’re either a giver of the basic wellsprings of life or a thirsty taker. He vowed to be the former. In a world of gutters, be a geyser.

You think about that story as Kelce drives you around his beloved Kansas City, home of his world-champion Chiefs, for whom he’s the star tight end and arguably the second-most popular player, after his best friend, quarterback Patrick Mahomes. You think about that story on a gorgeous autumn afternoon as Kelce gives you a personal tour of his decadelong history in this city, his singular journey from clueless rook to legend. (“I used to take this scenic route [to the stadium]—there’s just something about seeing the city you’re about to go represent….”)

A different sort of celebrity might be more guarded, might even chirp those big Rolls tires and speed away before someone throws their body across the luminous silver bonnet, but Kelce’s default emotion is this—exuberant extroversion. He likes people. Loves people. Never mind deciding not to be a drain. If people gush at him, he can’t help it, he gushes back.

Noting all this, you think how fame itself might be a kind of fountain. Some people moan about getting wet, others frolic like kids around a hydrant. You even wonder if this fountain-drain paradigm might be the skeleton key to Kelce, the Rosetta Stone for which half of America seems to be hunting right now.

Kelce was famous for several years, thanks to his Hall of Fame résumé, his symbiotic relationship with Mahomes, but that was just football famous. This year, after winning the Super Bowl, after hosting Saturday Night Live, after starring in all the commercials, Kelce became inescapable. And that was before—you know.

People have begun to ask in all earnestness why they can’t turn on their TV anymore without seeing Kelce’s sculpted mug. They wonder, not with snark, but in all sincerity: Who the frick is this guy? And where did he come from?

You have a TV. You wonder too. So you decide to join the search for answers. One weekend, in the thick of football season, you get on a plane to Kansas City.

BUT FIRST. Back up. Like that knucklehead who threw it into reverse, go back. Before you can take the Travis Michael Kelce Guided Tour, you need to watch him cry.

Kelce tries to play it off. He launches a sentence, stops. He launches another, again aborts. He paws his eyes with his giant hands and looks to be on the verge of losing it, because if Kelce loves people, what he really loves is his people.

This whole display takes place on a Monday afternoon at a Kansas City steakhouse, where you and Kelce are having an early dinner. Like, retirement-community early. He’s in recovery mode, healing from dozens of violent collisions sustained during the previous day’s win over division rival Los Angeles, and food is medicine. He can intuit when he’s hit the caloric sweet spot necessary to mend or maintain his 6-foot-5, 260-pound frame (roughly 4,000), and he’s not there yet. So he orders the dry-aged filet rubbed with coffee, Caesar salad (hold the anchovies), a side of “triple-cooked” fries and a glass of water.

After a long pause, and several Lamaze breaths, Kelce collects himself, apologizes. Can’t help it, he says; those folks who always have his back, who call him by the ancient secret nicknames (Big Yeti, El Travedor, Killatrav, Michael, etc.)—they’re everything. He doesn’t think of them as his entourage; he thinks of them as family, an extension of “Mama Kelce” and “Poppa Kelce” and older brother Jason, the starting center for the Philadelphia Eagles.

Patrick Bacon, a friend since first grade, says Kelce’s go-to method of winding down after a hard game or long day is to sit with this “core group” around his kitchen island and chop it up. Talk, that’s what nourishes Kelce, not videogames, not bottle service at some club.

“He loves to talk about the old days,” Bacon says. But it has to be with people from the old days. People who know that Kelce will sometimes dismiss a bad or subpar thing as “buns.” People who know that one of Kelce’s favorite desserts is French toast dripping with whipped cream and syrup. People who know that, growing up, he played every sport in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, and also know the difference between Cleveland Heights and Cleveland proper. You want to break into the Kelce core group? You better have a phone number that starts with 216.

And yet, you wonder how well his friends really know him, how well he lets anyone know him, because to a person they all say Trav lives in the moment, Trav never thinks about tomorrow, Trav never worries about retirement, despite recently turning 34, making him a Gollum in the NFL, whereas Kelce confesses that he thinks about it nonstop, “more than anyone could ever imagine.” In the same spirit, perhaps, he keeps his own counsel about his round-the-clock physical anguish. “That’s the only thing I’ve never really been open about,” he says, “the discomfort. The pain. The lingering injuries—the 10 surgeries I’ve had that I still feel every single surgery to this day.”

Kansas City’s longtime tight ends coach, Tom Melvin, says Kelce undersells the pain because the alternative is not playing, and the man will not miss games. “He has phenomenal pain tolerance. He’s played through things that other athletes I’ve coached through the years have not been able to push through. Mentally tough—way off the charts.”

Kelce’s trainer and physical therapist, Alex Skacel, says there’s not a single day, in season, when Kelce stretches out on the training table and doesn’t have some gruesome bruise. What few realize, however, is the insane number of scratches. Guys claw each other out there, Skacel says; it can leave Kelce’s epidermis striated with crimson. To bounce back after such abuse requires more than basic therapy. Kelce and Skacel use a battery of esoteric treatments, from cupping to dry needling to occlusion therapy: essentially tying off a limb with a tourniquet while Kelce works out. Kelce also adheres to a pregame regimen of anti-inflammatories, which he doesn’t like to discuss because they “have a history of affecting people’s insides.”

“There were definitely people she knew that knew who I was, in her corner [who said], ‘Yo! Did you know he was coming?'” Kelce says about how he initially found his way into Taylor Swift’s orbit. “I had someone playing Cupid.” Loewe coat, $4,990, Loewe.com.

IF KELCE BROODS on life without football, one reason is that he had an excruciating sneak preview. A redshirt sophomore at Cincinnati, he got booted off the team for smoking pot. In a blink, he lost everything—his purpose, his meaning. “It was like my life was over.”

He also lost his scholarship. He had to get a job. The best one he could find was at a telemarketing firm, doing healthcare surveys. “Eye-opening,” he says, bowing his head.

Cold-calling people in southern Ohio, northern Kentucky, eastern Indiana, asking what they thought of Obamacare, taught him a lot. (“Uh, sir, I ran out of the comment box, I can’t write anymore, we gotta kind of keep this moving.”) Above all it taught him that he didn’t want to ever do that again.

He probably won’t have to. He’s got options. Sometimes he sees himself in a broadcasting booth. Sometimes his manager talks about action flicks. (Maybe a Marvel movie? Kelce’s already built like Wolverine.) You also get the sense that Kelce toys with notions of doing some form of comedy. He haunts clubs, lives for open-mic nights, and he’s gotten to be friendly with several rising stand-ups.

At the moment, of course, the only thing millions of people want to know about Kelce’s future is whether or not it will include Taylor Swift. And the second thing they’re dying to know is how he and she got together in the first place.

Did he sit in a dark room and say Jumanji three times? He laughs. “I don’t know if I want to get into all of it,” he says, and then he gets into it, because fountain.

It all started when he tried to meet Swift at her Arrowhead concert in July and got blocked, presumably by security. He then recounted the experience in a charming way on the podcast he does with Jason. Soon after, he says, he received an unbidden assist from inside Team Swift.

“There were definitely people she knew that knew who I was, in her corner [who said]: Yo! Did you know he was coming? I had somebody playing Cupid.” He wasn’t aware at the time, however; the revelation only came later, after he looked down at his phone and got the shock of a lifetime. “She told me exactly what was going on and how I got lucky enough to get her to reach out.”

He lets slip that some of his early helpers were part of the Swift family tree. “She’ll probably hate me for saying this, but…when she came to Arrowhead, they gave her the big locker room as a dressing room, and her little cousins were taking pictures…in front of my locker.”

Understandably, he’s not handing out details about the first date, though he will say that he managed to not be nervous. “When I met her in New York, we had already kind of been talking, so I knew we could have a nice dinner and, like, a conversation, and what goes from there will go from there.”

If anyone was nervous, he adds, it was his core group. “Everybody around me telling me: Don’t f— this up! And me sitting here saying: Yeah—got it.”

Likewise, his mother. Donna Kelce still berates herself for how she handled a question about Taylor on the Today show. Trying not to sound too enthusiastic, she came off underwhelmed. Kelce, not wanting his mom to feel bad, immediately phoned her and assured her that she did a super job—adding that her green eyeglasses looked great.

These days, however, with the relationship progressing, Donna feels more at liberty. “I can tell you this,” she says, beaming. “He’s happier than I’ve seen him in a long time…. God bless him, he shot for the stars!”

Kelce seems freer, too. He doesn’t need to be asked about Taylor; he mentions her unreservedly, lavishes praise on her, calls her “hilarious,” “a genius,” notes that they share compatible worldviews, especially when it comes to family and work. “Everybody knows I’m a family guy,” he says. “Her team is her family. Her family does a lot of stuff in terms of the tour, the marketing, being around, so I think she has a lot of those values as well, which is right up my alley.”

One of Kelce’s friends describes a sweet, magical moment, a late-night gathering around Kelce’s firepit. Kelce and Swift looked like two “peas in a pod,” the friend says, and at one point they even burst into a memorable duet of—“Teenage Dirtbag”?

This must be fake

My lips start to shake

How does she know who I am?

Kelce squints into the distance: He’s not sure they were singing…Wheatus. But he allows that his memory might be compromised.

LONG BEFORE MEETING SWIFT, Kelce was just another Swiftie. In some ways he still is. He explains the concept of her concert—“She does it in eras”—as if you live in a yurt in Outer Mongolia. Then he eagerly informs you that the night he attended, he was counting the minutes until she got to 1989. (Both he and Swift were born in 1989.) “ ‘Blank Space’ was one I wanted to hear live for sure. I could make a bad guy good for the weekend. That’s a helluva line!”

More often than not, he says, it was a Swiftian beat, a melody that captivated him. (“She writes catchy jingles.”) But lately he’s all about those lyrics; he’s scrutinized the breakup stuff. What a miracle, he says, the way Swift can turn life into poetry. “I’ve never been a man of words. Being around her, seeing how smart Taylor is, has been f—ing mind-blowing. I’m learning every day.”

Something he might need to learn from Swift: how to handle the attention. Kelce lives in a quiet neighborhood north of downtown—leafy trees, trim lawns, no gates. There’s now a clutch of desperate-looking dudes with cameras stationed on his sidewalk 24/7. He’s followed everywhere, drones buzzing overhead—it’s stressful, more than he lets on, according to one confidante.

“Obviously I’ve never dated anyone with that kind of aura about them…. I’ve never dealt with it,” Kelce says. “But at the same time, I’m not running away from any of it…. The scrutiny she gets, how much she has a magnifying glass on her, every single day, paparazzi outside her house, outside every restaurant she goes to, after every flight she gets off, and she’s just living, enjoying life. When she acts like that I better not be the one acting all strange.”

Asked if he has anything to teach Swift, he looks shy. He can’t think of anything offhand.

Football?

Sure, he says, sounding unsure.

Of course, the thing she probably wants to learn about most is him. While talking to Kelce you realize all at once that the most avid participant in the national scavenger hunt for clues about his character is likely Swift herself. To that end, Donna says that anyone wishing to understand her younger son would do well to start with her older. Travis “could never quite catch up” to Jason, she says. “He was always just second, just searching to be the best, and never quite getting there.” (The only way in which the two brothers were full equals was appetite. As boys, Donna says, “they would sit down and eat whole chickens.”)

Others say the key to Travis is simpler than that. He’s basically still the kid who filled his Dad’s shampoo bottle with hand cream. “He just lives his life with so much joy,” Jason says. “He’s always kind of surrounding himself with people who are funny, who have a zest for life; it’s one of the things that defines him.”

Jason recalls many nights in the Kelce family room, the two brothers and mom eating in front of some comedy. “We had one of those coffee tables that the top would lift up and meet you at your face if you were eating,” he says, guffawing.

Indeed, Kelce has warned Swift that she’s going to have to reckon with this part of his personality. Adam Sandler, Chris Farley, Will Ferrell—they will all be a part of the relationship. “I told Taylor that I have that world, I’ve got to introduce it to her. I let her know: This is my jam right here.” (Kelce does an uncanny imitation of Farley’s dorky baritone, and the ringtone on his phone is Farley primal screaming: For the love of GOD!)

If the past is any prelude, this will register like an 8.0 earthquake among Swifties. Their queen—screening Tommy Boy? Every new factoid, every new piece of the puzzle, gets eagerly cataloged, investigated, celebrated, especially on “SwiftTok,” a fervent virtual community, according to Brian Donovan, a professor at the University of Kansas who teaches a seminar called The Sociology of Taylor Swift.

Donovan says several of his class discussions this semester have been given over to No. 87. Swifties make no apology for delving into her relationships, just as Shakespeare scholars like to contemplate the subject of the sonnets. But the deep “vetting” of Kelce, Donovan adds, goes well beyond fans. “I think there’s a public fascination, because it seems like a pure unalloyed moment of joy in the wider context of global wars, deepening political polarization, dysfunction in Congress, an ongoing health crisis. There’s a lot of bad news out there, and this is a common story that everybody knows about and can talk about. I don’t think we’ve had that in American culture for a long time.”

NOW GET IN THE CAR. Now you’re ready for the Rolls. Or are you? Gawking at the ceiling, you ask, Are those stars?

Yes, Kelce says.

You stare in disbelief. Embedded in a leather firmament are scores, no, hundreds—many hundreds—of twinkling lights, a fiber-optic galaxy meant to resemble the larger galaxy in which we’re all floating. For the sake of verisimilitude, the Rolls even produces a shooting star now and then. There was one, just a second ago, Kelce says. “Make a wish. Dreams come true.”

He guns the engine and steers toward downtown. The Rolls doesn’t drive so much as waft you around Kansas City. The ride is so cush, it almost makes sense, for a moment or two, that the car is worth more than many of the buildings you pass. (A Rolls Ghost, before customizing, goes for nearly half a million dollars.) All of which makes it that much more startling, as you come to the heart of downtown, when Kelce points out his first-ever apartment and shows you the alley door where he’d sneak in and out when he was late on the rent.

What?

He’s not ducking landlords these days. Still, he’s grossly underpaid. His $14 million salary, though near the top among tight ends, is half what the league’s star receivers make, and Kelce often functions as a receiver.

Nothing to be done, he says flatly. The Chiefs know, he says, that he would play for free. They know he loves his city, his quarterback. “Unfortunately, in this business, things gotta get ugly, they gotta get unpleasant [if you want more money], and I’m a pleasant son of a buck.”

Thank goodness for endorsements. At this point, says his co-manager Aaron Eanes, “the NFL is just his side hustle.”

Eanes and his brother, Andre, handle much of Kelce’s business life, from investments to marketing, and it was they who widened his investment portfolio, putting him into a tequila company, an energy drink and a chain of car washes. They also steered him into lucrative endorsements, like Bud Light and the Covid vaccine, for which he caught much grief from Aaron Rodgers. The Jets quarterback, out since game one of the season with a torn Achilles, belittled Kelce as a Pfizer shill during one of his Tuesday appearances on The Pat McAfee Show.

Kelce took the high road then. He’s staying on it now. “Aaron’s always been cool to me,” he says. “I knew he was trying to have some fun. He’s in a situation where Tuesdays are his game days…. So I get it, man, I’ve been injured too…. Who knows what the guy is going through?”

Mary Esselman, Operation Breakthrough’s CEO, says that whenever Kelce visits, he doesn’t bring media and he doesn’t leave until the last kid has felt seen and appreciated. Not long ago, she adds, Kelce sponsored a football camp. Afterward, Esselman asked the children to name the highlight of the experience.

One told her: “He remembered my name.”

Kelce drives you past a jazz club he likes, a coffee place he used to frequent. Just recently, he concedes, he could go to a Starbucks in Manhattan without anyone looking twice. Those days seem over. Minutes later, he’s steering past a small airport, where Swift’s plane is often prominently parked these days.

Is it there now, gleaming in the moonlight? The Kelce eras tour is coming to a close. Left unsaid, but palpable: She’s at the house, waiting.

The Rolls pulls off the highway, up the hill to your hotel. You thank him for taking so much time, for answering all your questions. As you step out of the Rolls, you turn, ask him one more.

You ask him if you’re going crazy, or did he really say that thing when you first got in the car? Did he really point to a shooting star in the ceiling of his Rolls-Royce and say, “Make a wish. Dreams come true”?

He cracks up.

He did. He said it.

He’s not running from it.

What’s more, it might just be true.

“How do you think I manifest it all?”

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last night my wife and I attended her highschool athletic association hall of fame banquet where she was being inducted as an honoree. A very big deal as she had a very serious career as a high school athlete which continued through college and after up even until today (she is actually out playing flag football this morning!) I am so proud of her and I know how much this means to her so I'm happy she is getting recognition.

But I am trying to process my own emotions surrounding this event and sporting culture in general, as a person who used to be athletic and active and now is disabled due to chronic physical and mental illness. It's a tough spot to be in but it's made much harder by the fact that our culture elevates sporting and being active and outdoorsy activities while either ignoring people with disabilities or outright blaming them for their mobility issues. My wife has always been very supportive of me but I don't think she always gets why I feel so vulnerable and out of place in "sports culture" events and groups. I think she thinks I can just come along for fun but it's wrapped up in so much garbage for me that even just spectating is really difficult.

Last night was tough enough because I don't particularly enjoy fancy affairs where you schmooze with strangers and especially was not looking forward to being likely the only queer people there but the sports thing just made things extra hard. That's all everyone talked about. And I get that it's so important! I remember those days too. It's just hard because I feel it was taken away from me. It makes me feel jealous, resentful, frustrated, and bored and all of those are ugly feelings and I don't like it.

I have met some of my wife's sportier friends in the past and they will shake my hand and look at me and my body and say things like "wow you should play hockey/football/basketball/handball." Should I play sports? Should I move my body for fun? Should I wake up every day and use my body in the way it was designed and not be crippled by pain? One time someone said to me "if I had your size I would dominate on the rugby pitch." If you had MY SIZE???? Let me tell you that as a person about 20 years into recovering from bulimia this is absolutely not the kind of shit I want to hear.

Last night someone saw my cane and asked (jokingly, I think?) if it was a sports injury. Nope, I'm disabled. Oh. Another person asked if I had attended this highschool, I said that no I had attended another highschool in the area; they asked if I did sports there, I said I did synchronized swimming until college. "Oh why didn't you continue?" Well jesus not that it's any of your business but that's when I became disabled, actually.

I have not figured out a way to gracefully navigate these situations while still respecting my own boundaries and privacy. They shouldn't be asking these questions but it wasn't too out of place considering the situation either. I just wish I knew what to say. It's hard because I'm still processing how I feel about my body and my limitations and I don't even really like talking about it with my doctors or my therapist, all of whom are awesome, or my friends, who are also awesome, so why would I want to talk about it with this random person? And I'm so mad that all of this got ripped open last night and I felt so vulnerable and upset and it's still getting to me today.

#chronically ill#chronic illness#chronic pain#chronic fatigue#autoimmune disease#disability pride#disability#disabled#disabilties#spoonie#spoon theory#mental health treatment#mental health awareness

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

O.J. SIMPSON

1947-2024

Orenthal James 'O.J.' Simpson was an alumni of the University of Southern California and winner of the Heisman Trophy. He was a former NFL running back for the Buffalo Bills (1969-77) and the San Francisco 49'ers (1977-78). Simpson parlayed his success on the gridiron into a career as an announcer and actor. As such, he appeared as himself on "Here's Lucy" in "The Big Game" (S6;E2) on September 17, 1973. In the episode, he speaks at Harry's Chamber of Commerce luncheon and passes on a couple of free passes to a sold out game. At first, Harry sells the tickets for a nifty profit, but then has to buy them back when he discovers that Simpson's wife will be there. When she cancels, Simpson gives Harry her tickets, which he tries to scalp outside the stadium.

Simpson was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1983 and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985. Once a popular figure with the public, he is known today for his trial and acquittal for the brutal murders of his former wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman. In 2007, Simpson was arrested in Las Vegas, Nevada, and charged with the felonies of armed robbery and kidnapping. He was convicted and sentenced to 33 years imprisonment, but granted parole on July 20, 2017. He died of cancer at age 76.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

FULL ARTICLE:

WHEN TRAVIS KELCE was a young man, his college football coach pulled him aside one day and told him the secret of life: Everybody you meet in this world is either a fountain or a drain.

“I need fountains,” the coach growled at Kelce. “I don’t need f—ing drains. Travis, you’re f—ing draaaining me!”

The advice left a deep impression. (“Changed his life,” says one of Kelce’s closest friends.) Yes, Kelce thought—you’re either a giver of the basic wellsprings of life or a thirsty taker. He vowed to be the former. In a world of gutters, be a geyser.

You think about that story as Kelce drives you around his beloved Kansas City, home of his world-champion Chiefs, for whom he’s the star tight end and arguably the second-most popular player, after his best friend, quarterback Patrick Mahomes. You think about that story on a gorgeous autumn afternoon as Kelce gives you a personal tour of his decadelong history in this city, his singular journey from clueless rook to legend. (“I used to take this scenic route [to the stadium]—there’s just something about seeing the city you’re about to go represent….”)

You can’t help thinking about that fountain story, not only because Kelce’s custom-made Rolls-Royce looks like a font of glowing light, not only because its silver goddess hood ornament is a burbling spigot of mercury. You think about that story because, as Kelce stops at a red light, as shirtless guys begin shambling toward the Rolls, apparently intent on opening the doors, getting an autograph, maybe even catching a ride, Kelce doesn’t seem the least bit alarmed. He’s smiling, waving, honking, even chuckling at a fan who leaps off the curb and “hits the stanky leg,” a dance Kelce has been known to bust out after a touchdown. At one point Kelce rolls down the window and exchanges hellos with some guy heedlessly reversing his rig into oncoming traffic, just so he can pull alongside Kelce and give a thumbs-up.

A different sort of celebrity might be more guarded, might even chirp those big Rolls tires and speed away before someone throws their body across the luminous silver bonnet, but Kelce’s default emotion is this—exuberant extroversion. He likes people. Loves people. Never mind deciding not to be a drain. If people gush at him, he can’t help it, he gushes back.

Noting all this, you think how fame itself might be a kind of fountain. Some people moan about getting wet, others frolic like kids around a hydrant. You even wonder if this fountain-drain paradigm might be the skeleton key to Kelce, the Rosetta Stone for which half of America seems to be hunting right now.

Kelce was famous for several years, thanks to his Hall of Fame résumé, his symbiotic relationship with Mahomes, but that was just football famous. This year, after winning the Super Bowl, after hosting Saturday Night Live, after starring in all the commercials, Kelce became inescapable. And that was before—you know.

People have begun to ask in all earnestness why they can’t turn on their TV anymore without seeing Kelce’s sculpted mug. They wonder, not with snark, but in all sincerity: Who the frick is this guy? And where did he come from?

You have a TV. You wonder too. So you decide to join the search for answers. One weekend, in the thick of football season, you get on a plane to Kansas City.

BUT FIRST. Back up. Like that knucklehead who threw it into reverse, go back. Before you can take the Travis Michael Kelce Guided Tour, you need to watch him cry.

Kelce is a hard man to tackle, but he’s shockingly easy to trigger. You just have to mention his best friends, the tight-knit crew who hang at his house and tag along on his golf outings, who manage his money and curate his diet and fill his private suite at Arrowhead Stadium. Suddenly, his cornflower-blue eyes, which normally twinkle, start to glisten. Now come the tears. Big sloppy ones. Talk about your fountains.

Kelce tries to play it off. He launches a sentence, stops. He launches another, again aborts. He paws his eyes with his giant hands and looks to be on the verge of losing it, because if Kelce loves people, what he really loves is his people.

This whole display takes place on a Monday afternoon at a Kansas City steakhouse, where you and Kelce are having an early dinner. Like, retirement-community early. He’s in recovery mode, healing from dozens of violent collisions sustained during the previous day’s win over division rival Los Angeles, and food is medicine. He can intuit when he’s hit the caloric sweet spot necessary to mend or maintain his 6-foot-5, 260-pound frame (roughly 4,000), and he’s not there yet. So he orders the dry-aged filet rubbed with coffee, Caesar salad (hold the anchovies), a side of “triple-cooked” fries and a glass of water.

After a long pause, and several Lamaze breaths, Kelce collects himself, apologizes. Can’t help it, he says; those folks who always have his back, who call him by the ancient secret nicknames (Big Yeti, El Travedor, Killatrav, Michael, etc.)—they’re everything. He doesn’t think of them as his entourage; he thinks of them as family, an extension of “Mama Kelce” and “Poppa Kelce” and older brother Jason, the starting center for the Philadelphia Eagles.

Patrick Bacon, a friend since first grade, says Kelce’s go-to method of winding down after a hard game or long day is to sit with this “core group” around his kitchen island and chop it up. Talk, that’s what nourishes Kelce, not videogames, not bottle service at some club.

“He loves to talk about the old days,” Bacon says. But it has to be with people from the old days. People who know that Kelce will sometimes dismiss a bad or subpar thing as “buns.” People who know that one of Kelce’s favorite desserts is French toast dripping with whipped cream and syrup. People who know that, growing up, he played every sport in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, and also know the difference between Cleveland Heights and Cleveland proper. You want to break into the Kelce core group? You better have a phone number that starts with 216.

And yet, you wonder how well his friends really know him, how well he lets anyone know him, because to a person they all say Trav lives in the moment, Trav never thinks about tomorrow, Trav never worries about retirement, despite recently turning 34, making him a Gollum in the NFL, whereas Kelce confesses that he thinks about it nonstop, “more than anyone could ever imagine.” In the same spirit, perhaps, he keeps his own counsel about his round-the-clock physical anguish. “That’s the only thing I’ve never really been open about,” he says, “the discomfort. The pain. The lingering injuries—the 10 surgeries I’ve had that I still feel every single surgery to this day.”

Kansas City’s longtime tight ends coach, Tom Melvin, says Kelce undersells the pain because the alternative is not playing, and the man will not miss games. “He has phenomenal pain tolerance. He’s played through things that other athletes I’ve coached through the years have not been able to push through. Mentally tough—way off the charts.”

Kelce’s trainer and physical therapist, Alex Skacel, says there’s not a single day, in season, when Kelce stretches out on the training table and doesn’t have some gruesome bruise. What few realize, however, is the insane number of scratches. Guys claw each other out there, Skacel says; it can leave Kelce’s epidermis striated with crimson. To bounce back after such abuse requires more than basic therapy. Kelce and Skacel use a battery of esoteric treatments, from cupping to dry needling to occlusion therapy: essentially tying off a limb with a tourniquet while Kelce works out. Kelce also adheres to a pregame regimen of anti-inflammatories, which he doesn’t like to discuss because they “have a history of affecting people’s insides.”

Despite it all, Kelce sounds like a man who’s never loved football more. Skacel recalls being with Kelce in Paris for Fashion Week. Around midnight, after 12 hours of bouncing from one designer show to another, Kelce was feeling guilty that he hadn’t done enough that day for his body. He suggested a run. Soon, a quick jog along the Seine turned into a mini-marathon, then wind sprints across empty bridges. While Paris slept, Kelce and Skacel grinded. It was cinematic, both men say, a double pump of adrenaline, like something out of Rocky. More, it was a reaffirmation of what matters most.

IF KELCE BROODS on life without football, one reason is that he had an excruciating sneak preview. A redshirt sophomore at Cincinnati, he got booted off the team for smoking pot. In a blink, he lost everything—his purpose, his meaning. “It was like my life was over.”

He also lost his scholarship. He had to get a job. The best one he could find was at a telemarketing firm, doing healthcare surveys. “Eye-opening,” he says, bowing his head.

Cold-calling people in southern Ohio, northern Kentucky, eastern Indiana, asking what they thought of Obamacare, taught him a lot. (“Uh, sir, I ran out of the comment box, I can’t write anymore, we gotta kind of keep this moving.”) Above all it taught him that he didn’t want to ever do that again.

He probably won’t have to. He’s got options. Sometimes he sees himself in a broadcasting booth. Sometimes his manager talks about action flicks. (Maybe a Marvel movie? Kelce’s already built like Wolverine.) You also get the sense that Kelce toys with notions of doing some form of comedy. He haunts clubs, lives for open-mic nights, and he’s gotten to be friendly with several rising stand-ups.

At the moment, of course, the only thing millions of people want to know about Kelce’s future is whether or not it will include Taylor Swift. And the second thing they’re dying to know is how he and she got together in the first place.

More study has been dedicated to the opening salvos of their relationship than to the first seconds of the Big Bang, and thus far both origins remain a mystery. People have even speculated that Kelce somehow spoke his desire into the universe and just—manifested Swift?

Did he sit in a dark room and say Jumanji three times? He laughs. “I don’t know if I want to get into all of it,” he says, and then he gets into it, because fountain.

It all started when he tried to meet Swift at her Arrowhead concert in July and got blocked, presumably by security. He then recounted the experience in a charming way on the podcast he does with Jason. Soon after, he says, he received an unbidden assist from inside Team Swift.

“There were definitely people she knew that knew who I was, in her corner [who said]: Yo! Did you know he was coming? I had somebody playing Cupid.” He wasn’t aware at the time, however; the revelation only came later, after he looked down at his phone and got the shock of a lifetime. “She told me exactly what was going on and how I got lucky enough to get her to reach out.”

He lets slip that some of his early helpers were part of the Swift family tree. “She’ll probably hate me for saying this, but…when she came to Arrowhead, they gave her the big locker room as a dressing room, and her little cousins were taking pictures…in front of my locker.”

Understandably, he’s not handing out details about the first date, though he will say that he managed to not be nervous. “When I met her in New York, we had already kind of been talking, so I knew we could have a nice dinner and, like, a conversation, and what goes from there will go from there.”

If anyone was nervous, he adds, it was his core group. “Everybody around me telling me: Don’t f— this up! And me sitting here saying: Yeah—got it.”

As those first heady days unfolded, as news bulletins and cutaways showed Swift cheering Kelce on from his suite, Kelce was uncharacteristically guarded with the media. “That was the biggest thing to me: make sure I don’t say anything that would push Taylor away.”

Likewise, his mother. Donna Kelce still berates herself for how she handled a question about Taylor on the Today show. Trying not to sound too enthusiastic, she came off underwhelmed. Kelce, not wanting his mom to feel bad, immediately phoned her and assured her that she did a super job—adding that her green eyeglasses looked great.

These days, however, with the relationship progressing, Donna feels more at liberty. “I can tell you this,” she says, beaming. “He’s happier than I’ve seen him in a long time…. God bless him, he shot for the stars!”

Kelce seems freer, too. He doesn’t need to be asked about Taylor; he mentions her unreservedly, lavishes praise on her, calls her “hilarious,” “a genius,” notes that they share compatible worldviews, especially when it comes to family and work. “Everybody knows I’m a family guy,” he says. “Her team is her family. Her family does a lot of stuff in terms of the tour, the marketing, being around, so I think she has a lot of those values as well, which is right up my alley.”

One of Kelce’s friends describes a sweet, magical moment, a late-night gathering around Kelce’s firepit. Kelce and Swift looked like two “peas in a pod,” the friend says, and at one point they even burst into a memorable duet of—“Teenage Dirtbag”?

This must be fake

My lips start to shake

How does she know who I am?

LONG BEFORE MEETING SWIFT, Kelce was just another Swiftie. In some ways he still is. He explains the concept of her concert—“She does it in eras”—as if you live in a yurt in Outer Mongolia. Then he eagerly informs you that the night he attended, he was counting the minutes until she got to 1989. (Both he and Swift were born in 1989.) “ ‘Blank Space’ was one I wanted to hear live for sure. I could make a bad guy good for the weekend. That’s a helluva line!”

More often than not, he says, it was a Swiftian beat, a melody that captivated him. (“She writes catchy jingles.”) But lately he’s all about those lyrics; he’s scrutinized the breakup stuff. What a miracle, he says, the way Swift can turn life into poetry. “I’ve never been a man of words. Being around her, seeing how smart Taylor is, has been f—ing mind-blowing. I’m learning every day.”

Something he might need to learn from Swift: how to handle the attention. Kelce lives in a quiet neighborhood north of downtown—leafy trees, trim lawns, no gates. There’s now a clutch of desperate-looking dudes with cameras stationed on his sidewalk 24/7. He’s followed everywhere, drones buzzing overhead—it’s stressful, more than he lets on, according to one confidante.

“Obviously I’ve never dated anyone with that kind of aura about them…. I’ve never dealt with it,” Kelce says. “But at the same time, I’m not running away from any of it…. The scrutiny she gets, how much she has a magnifying glass on her, every single day, paparazzi outside her house, outside every restaurant she goes to, after every flight she gets off, and she’s just living, enjoying life. When she acts like that I better not be the one acting all strange.”

Asked if he has anything to teach Swift, he looks shy. He can’t think of anything offhand.

Football?

Sure, he says, sounding unsure.

Of course, the thing she probably wants to learn about most is him. While talking to Kelce you realize all at once that the most avid participant in the national scavenger hunt for clues about his character is likely Swift herself. To that end, Donna says that anyone wishing to understand her younger son would do well to start with her older. Travis “could never quite catch up” to Jason, she says. “He was always just second, just searching to be the best, and never quite getting there.” (The only way in which the two brothers were full equals was appetite. As boys, Donna says, “they would sit down and eat whole chickens.”)

Others say the key to Travis is simpler than that. He’s basically still the kid who filled his Dad’s shampoo bottle with hand cream. “He just lives his life with so much joy,” Jason says. “He’s always kind of surrounding himself with people who are funny, who have a zest for life; it’s one of the things that defines him.”

Jason recalls many nights in the Kelce family room, the two brothers and mom eating in front of some comedy. “We had one of those coffee tables that the top would lift up and meet you at your face if you were eating,” he says, guffawing.

Maybe that’s why Kelce still watches and rewatches those same movies and shows? All his sacred entities got fused into one dollop of sensory memory—food, family, laughter.

Indeed, Kelce has warned Swift that she’s going to have to reckon with this part of his personality. Adam Sandler, Chris Farley, Will Ferrell—they will all be a part of the relationship. “I told Taylor that I have that world, I’ve got to introduce it to her. I let her know: This is my jam right here.” (Kelce does an uncanny imitation of Farley’s dorky baritone, and the ringtone on his phone is Farley primal screaming: For the love of GOD!)

If the past is any prelude, this will register like an 8.0 earthquake among Swifties. Their queen—screening Tommy Boy? Every new factoid, every new piece of the puzzle, gets eagerly cataloged, investigated, celebrated, especially on “SwiftTok,” a fervent virtual community, according to Brian Donovan, a professor at the University of Kansas who teaches a seminar called The Sociology of Taylor Swift.

Donovan says several of his class discussions this semester have been given over to No. 87. Swifties make no apology for delving into her relationships, just as Shakespeare scholars like to contemplate the subject of the sonnets. But the deep “vetting” of Kelce, Donovan adds, goes well beyond fans. “I think there’s a public fascination, because it seems like a pure unalloyed moment of joy in the wider context of global wars, deepening political polarization, dysfunction in Congress, an ongoing health crisis. There’s a lot of bad news out there, and this is a common story that everybody knows about and can talk about. I don’t think we’ve had that in American culture for a long time.”

NOW GET IN THE CAR. Now you’re ready for the Rolls. Or are you? Gawking at the ceiling, you ask, Are those stars?

Yes, Kelce says.

You stare in disbelief. Embedded in a leather firmament are scores, no, hundreds—many hundreds—of twinkling lights, a fiber-optic galaxy meant to resemble the larger galaxy in which we’re all floating. For the sake of verisimilitude, the Rolls even produces a shooting star now and then. There was one, just a second ago, Kelce says. “Make a wish. Dreams come true.”

He guns the engine and steers toward downtown. The Rolls doesn’t drive so much as waft you around Kansas City. The ride is so cush, it almost makes sense, for a moment or two, that the car is worth more than many of the buildings you pass. (A Rolls Ghost, before customizing, goes for nearly half a million dollars.) All of which makes it that much more startling, as you come to the heart of downtown, when Kelce points out his first-ever apartment and shows you the alley door where he’d sneak in and out when he was late on the rent.

What?

It was his rookie season, he says, and the paychecks rolled in every week. But he didn’t understand that paychecks stop when the season does. So he didn’t budget. “I don’t want to say I was broke….” But he was. “There might have been one or two days I avoided the landlord.”

He’s not ducking landlords these days. Still, he’s grossly underpaid. His $14 million salary, though near the top among tight ends, is half what the league’s star receivers make, and Kelce often functions as a receiver.

Nothing to be done, he says flatly. The Chiefs know, he says, that he would play for free. They know he loves his city, his quarterback. “Unfortunately, in this business, things gotta get ugly, they gotta get unpleasant [if you want more money], and I’m a pleasant son of a buck.”

Thank goodness for endorsements. At this point, says his co-manager Aaron Eanes, “the NFL is just his side hustle.”

Eanes and his brother, Andre, handle much of Kelce’s business life, from investments to marketing, and it was they who widened his investment portfolio, putting him into a tequila company, an energy drink and a chain of car washes. They also steered him into lucrative endorsements, like Bud Light and the Covid vaccine, for which he caught much grief from Aaron Rodgers. The Jets quarterback, out since game one of the season with a torn Achilles, belittled Kelce as a Pfizer shill during one of his Tuesday appearances on The Pat McAfee Show.

Kelce took the high road then. He’s staying on it now. “Aaron’s always been cool to me,” he says. “I knew he was trying to have some fun. He’s in a situation where Tuesdays are his game days…. So I get it, man, I’ve been injured too…. Who knows what the guy is going through?”

Kelce double-parks the Rolls outside a building that’s brightly lit, unusual in this neighborhood. That’s Operation Breakthrough, he says, voice swelling with emotion. Founded in 1971, the charitable organization provides safe spaces and cutting-edge educational resources for the city’s poorest children. Kelce enjoys coming here to visit, and sometimes invites the children to his suite on Sundays. And three years ago, when Operation Breakthrough wanted to expand, he bought them the muffler shop next door.

Mary Esselman, Operation Breakthrough’s CEO, says that whenever Kelce visits, he doesn’t bring media and he doesn’t leave until the last kid has felt seen and appreciated. Not long ago, she adds, Kelce sponsored a football camp. Afterward, Esselman asked the children to name the highlight of the experience.

One told her: “He remembered my name.”

Kelce drives you past a jazz club he likes, a coffee place he used to frequent. Just recently, he concedes, he could go to a Starbucks in Manhattan without anyone looking twice. Those days seem over. Minutes later, he’s steering past a small airport, where Swift’s plane is often prominently parked these days.

Is it there now, gleaming in the moonlight? The Kelce eras tour is coming to a close. Left unsaid, but palpable: She’s at the house, waiting.

The Rolls pulls off the highway, up the hill to your hotel. You thank him for taking so much time, for answering all your questions. As you step out of the Rolls, you turn, ask him one more.

You ask him if you’re going crazy, or did he really say that thing when you first got in the car? Did he really point to a shooting star in the ceiling of his Rolls-Royce and say, “Make a wish. Dreams come true”?

He cracks up.

He did. He said it.

He’s not running from it.

What’s more, it might just be true.

“How do you think I manifest it all?”

12 notes

·

View notes