#CC BY NC ND

Text

Inner Light: Phase 3

Digital art

2023

(Lic.: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

#dark art#occult art#sepia#noughtlux#abstract#circles#tulpa#metaphysics#light#སྤྲུལ་སྐུ་#inscape#digital art#artists on tumblr#art#CC BY NC ND

478 notes

·

View notes

Text

Generative geometry by Frederik Vanhoutte, wblut

1 note

·

View note

Text

The crisis of the world - 1933 and 2023

Thomas Weber

Memorise content

What does 1933 teach us? If we understand National Socialism as a form of illiberal democracy, we can see that today's variants could easily slide into something worse. Then as now, exaggerated perceptions of crisis play an important role.

In times when several major crises are brewing into what is perceived as an existential poly-crisis, fears of the political consequences of this perception spread. The most spectacular case of the collapse of a democracy - the collapse of the Weimar Republic in January 1933 - is therefore repeatedly scrutinised in the hope of discovering lessons for the present.

A prime example of this in recent years is what has been happening in the United States: since the New York Times columnist Roger Cohen greeted his readers with "Welcome to Weimar America" in December 2015, "Weimerica" has developed into a veritable genre of opinion pieces and books. After the attack on the Capitol in Washington in January 2021, the son of an Austrian SA man also used his fame as a Hollywood actor and former governor of the US state of California to record a video message to the world: In it, Arnold Schwarzenegger spoke about his father and drew direct comparisons between the Reichspogromnacht, the Nazi anti-Jewish pogrom of 9 November 1938, and the situation in the US in early 2021. to resolve the footnote[3]

It is therefore not surprising that Adolf Hitler is more dominant in public discourse today than he was a generation ago. Between 1995 and 2018, the frequency with which Hitler was mentioned in English-language books rose by an astonishing 55 per cent. In Spanish-language books, the frequency even increased by more than 210 per cent in the same period. To break up the footnote[4] This increase is a result of both a growing perception of crisis and another phenomenon: an awareness of how much the world we live in today can be traced back directly and indirectly to the horrors of the "Third Reich" and the Second World War.

But the world that emerged in 1933 is not invoked everywhere in order to understand and interpret today's situation. Strangely enough, one country in the heart of Europe has taken a different direction: Germany itself. Here, the frequency with which Hitler was mentioned in books fell by more than two thirds between 1995 and 2018. The same trend applies to other terms that refer to the darkest chapter of Germany's past, such as "National Socialism" and "Auschwitz". To resolve the footnote[5] However, a declining interest in National Socialism should not lead to the false assumption that today's Germany is less strongly characterised by the legacy of the "Third Reich" and the horror that the Germans spread throughout Europe. The legacy of National Socialism defines who the Germans are, and has done so since the day Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor in January 1933.

New "special path"

In Germany, there was probably not so much explicit publicity about National Socialism because it was believed that the country had learnt from the past and built an exemplary political system with a corresponding society that had internalised the lessons of National Socialism. The prevailing narrative of the early Berlin Republic was that Germany had taken a "special path" towards dictatorship and genocide in the 19th and early 20th centuries. With reunification in 1990, however, the country had finally left this path and had fully arrived in the West. To resolve the footnote[6] According to this interpretation, the Berlin Republic was a new player in international politics, working side by side with its partners in Europe and the world to secure peace and stability at home and abroad.

However, the varying frequency with which Hitler, Auschwitz and National Socialism are referred to in books in Germany and abroad shows that Germany did not abandon its special path in 1990, but rather embarked on a new one. Germany's actual special path is that of its second (post-war) republic, which was founded in 1990 and, if one follows the argumentation of journalist and historian Nils Minkmar, collapsed in the wake of Putin's war of aggression against Ukraine. Germany's second republic, writes Minkmar, "took a holiday from history, was finally able to enjoy the moment like Faust and, also like Faust, made a pact - with Putin and with bad consequences". To resolve the footnote[7] However, Germany's holiday from history came to an abrupt end with the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. In the words of Federal Chancellor Olaf Scholz: "24 February 2022 marks a turning point in the history of our continent." To resolve the footnote[8] Scholz is right when he speaks of a turning point, but it does not primarily concern "our continent", but first and foremost his own country. The Russian invasion of Ukraine made many Germans suddenly aware of the realities of international politics that had been present to Germany's neighbours for some time.

The Faustian pact was not born of malice - Germany's second republic had been founded and governed with the best of intentions. Rather, a certain short-sightedness had prevailed that prevented many Germans from seeing what many of their international partners had long recognised after Russia's previous invasions or the shooting down of MH17 - the Malaysia Airlines plane that was shot down by a Russian missile in Ukrainian airspace on its way from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur in July 2014. And this short-sightedness is closely linked to the normative conclusions that the protagonists of the Second German Republic had drawn from the country's experience with National Socialism, which differed quite drastically from those drawn by other countries.

As a result, many Germans relied on soft power and had little interest in hard power - without realising that the former is just hot air if it is not accompanied by the latter. At the same time, many failed to recognise that Putin's aggressive approach since the day he took office was in line with earlier phases of Russian history. This is also reflected in a sharp decline in references in German-language publications to terms associated with the dark side of Russia's past, such as "Gulag", "Stalin", "Prague Spring" or "popular uprising". Dissolving the footnote[9] In English-language books, the number of mentions of the terms "Stalin" and "Prague Spring" remained relatively constant between 1995 and 2018, while mentions of the "Gulag" actually increased significantly. Resolution of the footnote[10]

The illusions that were harboured in Germany ultimately stood in the way of both even more successful European integration and the creation of an even more durable security and peace architecture. Minkmar therefore believes that a third republic must emerge from the ruins of the second: one that takes a less short-sighted view of the world around it and leaves behind the "naivety" of thinking about the world. To resolve the footnote[11] It is therefore necessary to work out lessons from the "Third Reich" for the third republic.

Historical misunderstandings

However, the myopic view of the past is not limited to Germany. In fact, many of the lessons learnt worldwide from 1933 for crisis management in the 2020s are based on historical misunderstandings. For example, although there are countless books about the "Third Reich" and its horrors, in many cases, and without realising it, they reproduce clichés dating back to Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, or they portray Hitler and the National Socialists only as madmen driven by hatred, racism and anti-Semitism. However, such approaches will never understand why so many supporters of National Socialism saw themselves as idealists. And they will not be able to explain why, according to Hitler, reason, not emotion, should determine the actions of National Socialism. On the resolution of the footnote[12]

A reductionist approach to the question of what characterised Hitler and other National Socialists is dangerous. It tempts us to look for false warning signs in today's world and to search for Hitler revenants and National Socialists in the wrong places. We are therefore recommended to read Thomas Mann's essay "Brother Hitler" from 1938, in which he portrays the dictator as a product of the same traditions in which he himself had grown up. In doing so, he opens our eyes to the realisation that it is not the angry crybabies, but above all people "like us" who are open to dismantling democracy in times of crisis. In fact, as soon as we take the ideas of the National Socialists seriously, it becomes disturbingly clear that many people supported these policies in the period from the 1920s to the 1940s for almost the same reasons that we so vehemently reject National Socialism today - not least the conviction that political legitimacy should come from the people and that equality is an ideal worth fighting for.

It is therefore important to dispel various misconceptions about the death of democracy in 1933 that are still taught in German schools today, including the idea that the seeds of Weimar's self-destruction were sown as early as 1919, that the "unstable Weimar constitution (.... ) ultimately led to the self-dissolution of the first German democracy", that "coalitions capable of governing [became] impossible because there were too many splinter parties", On the dissolution of the footnote[13] that the rise of Hitler resulted from the strength of the German conservatives, that the world economic crisis played the decisive role in the death of German democracy, that Germans supported the National Socialists, because they longed for the return of the authoritarian state of the past and rejected democracy in any form, or that the actions of the National Socialists did little to bring Hitler to power - which is evident, for example, in the tendency to speak only of a "transfer of power" in relation to the events of 1933 and not of a process that was both a "transfer of power" and a "seizure of power". On the resolution of the footnote[14]

The beliefs of the National Socialists and the appeal of their ideas cannot be understood if we do not take seriously the central apparent contradictions at the core of National Socialism, namely that the National Socialists destroyed democracy and socialism in the name of overcoming an all-encompassing, existential mega-crisis and creating a supposedly better and truer democracy and socialism. The National Socialists preached that all power must come from the people, not out of insincere and opportunistic Machiavellianism, but because they believed it. The promise of a National Socialist illiberal "people's community democracy" as a collectivist and marginalising concept of self-determination was widely accepted and promised to overcome what was supposedly the greatest crisis in centuries. This made 1933 possible and ultimately brought the world to the gates of hell.

So if we understand National Socialism as a manifestation of illiberal democracy, we see that today's variants of illiberal democracy could very easily slide into something much worse in times of crisis than we are currently experiencing in many places around the world. If we refrain from a reductionist account of National Socialism, we will recognise that the parallels between the present and the past lie primarily in the dangers posed by illiberal democracy and the general perception of crisis.

Furthermore, if we understand National Socialism as a political religion, we can understand why Germans followed its siren song en masse. Hitler's political religion demanded a double commitment from converts: firstly, to National Socialist orthodoxy - adherence to 'correct' beliefs and the practice of rituals - and secondly, to National Socialist orthopraxy - the 'ethical' behaviour prescribed by orthodoxy. In this way, acts of violence and war against internal and external "enemies of the people" were given a moral and even heroic significance - because they supposedly served a "higher" purpose, the good of one's own "national community". The belief systems of National Socialism are therefore inextricably linked to the violence and horrors of the "Third Reich". In other words, while it may well be true that liberal democracy brings with it a "peace dividend", illiberal democracy - at least in its totalitarian, messianic incarnations - can easily generate a "genocide and war dividend" if people believe they can overcome an existential crisis in this way.

Just as the National Socialist mindset should be taken seriously as a key driver of violent and extreme behaviour, the National Socialists themselves should also be understood as political actors with a clear plan for the future. Although it often looked as if they were merely reacting to others, it was precisely this reactive character of National Socialist behaviour that was a tactic - and a very successful one at that - that explains not only the developments in 1933, but also the dynamics of twelve years of Nazi rule. The path from the seizure of power to the settlement policy in the East, to total war and to a war policy of extermination and genocide was by no means long and tortuous - in the self-perception of its actors, it was the path to overcoming an existential polycrisis.

What does 1933 teach us?

The way in which the National Socialists succeeded in seizing and consolidating power and ultimately pursuing radical policies has more in common with the cunning of Frank Underwood, the fictional US president from the Netflix series "House of Cards", than with many of the portrayals that question whether their rise was coolly calculated. The political style and the illusion game of the National Socialists, the undermining and destruction of norms and institutions as well as the pursuit of a hidden agenda are increasingly becoming characteristics of politics in our time as well. Understanding the year 1933 should therefore help us to better understand today's challenges.

We therefore need a defensive democracy with strong guard rails in order to be able to counter the perception of an existential polycrisis. This includes strong party-political organisations that - unlike in daydreams of the transformation of parties into "movements" - prevent the internal takeover by radicals. Crucially, strong party structures also provide a toolkit to deal with polarised societies by both representing and containing divisions. The behaviour of conservative parties is particularly important here. German conservatism played a central role in the fall of Weimar democracy, but in a counter-intuitive way, not through its strength but through its weakness and the fragmentation of its organisations.

However, guard rails offer little or no protection if they are poorly positioned. Thus, a look beyond Germany reveals that in trying to make our own democracy weatherproof and crisis-resistant, we may have more to learn from cases where democracy survived in 1933 than from the death of democracy in Germany. The Netherlands, for example, had established a resilient political structure, or a defencible democracy avant la lettre, capable of dealing with a wide range of shocks to its system and responding flexibly to crises. As a result, the Dutch did not need to anticipate the specific threats of 1933, as their crisis prevention and response capacities were large enough to avoid the establishment of a domestic dictatorship. The comparison also shows that some supposed guard rails of today's democracy in Germany - such as the five per cent hurdle in elections - are largely useless and only appear to offer security.

The problem of looking at specific cases of the collapse of democracy, including the German case in 1933, harbours a danger: that the most important variables are insufficiently recognised and too narrow conclusions are drawn. The exact historical context of the collapse of a political order will always vary, as will the perception of an existential polycrisis and its political consequences. It therefore makes sense to identify states and societies from the past that were resilient to the widest possible range of shocks. Or as historian Niall Ferguson puts it: "All we can learn from history is how to build social and political structures that are at least resilient and at best antifragile (...), and how to resist the siren voices that propose totalitarian rule or world government as necessary for the protection of our unfortunate species and our vulnerable world." To resolve the footnote[15]

Nevertheless, the fall of the Weimar Republic in 1933 is a warning of where uncontained perceptions of crisis can lead. After all, it was Hitler's polycrisis consciousness and the associated individual and collective existential fear that formed the core of the emergence of Hitler's political and genocidal anti-Semitism. Added to this was the identification of the Jews with this crisis and the implementation of this identification in a programme of total solutions in order to "protect" themselves permanently. To resolve the footnote[16]

Perhaps the most important warning that the past century holds for us is that the biggest and most terrible crises in the world only arise when we try to contain real or perceived crises headlessly and without moderation. To resolve the footnote[17]

This article is a revised extract from Thomas Weber (ed.), Als die Demokratie starb. Die Machtergreifung der Nationalsozialisten - Geschichte und Gegenwart, Freiburg/Br. 2022.

Footnotes

On the mention of the footnote [1]

Roger Cohen, Trump's Weimar America, 14 Dec 2015, External link:http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/15/opinion/weimar-america.html.

For the mention of the footnote [2]

Niall Ferguson, "Weimar America"? The Trump Show Is No Cabaret, 6 Sept. 2020, External link:http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/weimar-america-the-trump-show-is-no-cabaret/2020/09/06/adbb62ca-f041-11ea-8025-5d3489768ac8_story.html.

On the mention of the footnote [3]

Cf. Thomas Weber, Trump Is Not a Fascist. But That Didn't Make Him Any Less Dangerous to Our Democracy, 24.1.2021, external link:https://edition.cnn.com/2021/01/24/opinions/trump-fascism-misguided-comparison-weber/index.html.

On the mention of the footnote [4]

Cf. Google N-gram analyses for "Hitler" and "Auschwitz" in English and Spanish, created on 10 August 2022: External link:https://t1p.de/ngramspanish and External link:https://t1p.de/ngramenglish.

For the mention of the footnote [5]

Cf. Google N-gram analyses for "Hitler", "Auschwitz" and "National Socialism" in German, created on 10 January 2022: External link:https://t1p.de/ngramgerman.

On the mention of the footnote [6]

Cf. Heidi Tworek/Thomas Weber, Das Märchen vom Schicksalstag, 8 November 2014, External link:http://www.faz.net/13253194.html.

On the mention of the footnote [7]

Nils Minkmar, Long live the Third Republic, 10 May 2022, External link:http://www.sueddeutsche.de/projekte/artikel/kultur/e195647.

Mention of the footnote [8]

Government statement by Federal Chancellor Olaf Scholz, 27 February 2022, External link:http://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/suche/regierungserklaerung-von-bundeskanzler-olaf-scholz-am-27-februar-2022-2008356.

Mention of the footnote [9]

Cf. Google N-gram analyses for "Stalin", "Gulag", "Prager Frühling" and "Volksaufstand" in German, created on 10 August 2022: External link:https://t1p.de/ngramstalingerman and External link:https://t1p.de/ngramgulagpfvgerman.

For the mention of the footnote [10]

Cf. Google N-gram analyses for "Stalin", "Gulag" and "Prague Spring" in English, created on 10 August 2022: External link:https://t1p.de/ngramstalinenglish and External link:https://t1p.de/ngramgulagpsenglish.

On the mention of the footnote [11]

See Minkmar (note 7).

On the mention of the footnote [12]

In his first known written anti-Semitic statement - the so-called Gemlich letter of 1919 - Hitler rejected "anti-Semitism on purely emotional grounds" and advocated an "anti-Semitism of reason". Cf. Hitler to Adolf Gemlich, 16 September 1919, reproduced in: German Historical Institute Washington DC, German History in Documents and Images, n.d., external link:https://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/pdf/deu/NAZI_HITLER_ANTISEMITISM1_DEU.pdf.

On the mention of the footnote [13]

Cf. Fabio Schwabe, Gründe für das Scheitern der Weimarer Republik, 12 March 2021, external link:http://www.geschichte-abitur.de/weimarer-republik/gruende-fuer-das-scheitern.

On the mention of the footnote [14]

Cf. Hans-Jürgen Lendzian (ed.), Zeiten und Menschen. Geschichte, Qualifikationsphase Oberstufe Nordrhein-Westfalen, Braunschweig 2019, pp. 237-264; Ulrich Baumgärtner et al. (eds.), Horizonte. Geschichte Qualifikationsphase, Sekundarstufe II Nordrhein-Westfalen, Braunschweig 2015, pp. 242-270.

On the mention of the footnote [15]

Niall Ferguson, Doom. The Politics of Catastrophe, London 2022, p. 17, own translation.

On the mention of the footnote [16]

Cf. Thomas Weber, Germany in Crisis. Hitler's Antisemitism as a Function of Existential Anxiety and a Quest for Sustainable Security, in: Antisemitism Studies (n.d.).

On the mention of the footnote [17]

Cf. Beatrice de Graaf, Crisis!, Amsterdam 2022.

#Creative Commons Licence#CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 DE#Thomas Weber#bpb.de#Germany 1933#weimar#weimar America#stop violence#stop trump#save our democracy#vote democrat#vote blue#please vote#Weimerica#Roger Cohen#read more

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photograph of Freda Paolozzi. Nigel Henderson, c.1950s

(via ‘Photograph of Freda Paolozzi‘, Nigel Henderson, [c.1950s] – Tate Archive | Tate)

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bad news for moose-dogs, bird-barking dogs, squirrel dogs, bay dogs and other kind of dogs out there.

Especially since so many U.Sian are downwind of the wildfires up north.

Article is open access under Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial – NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). You should be safe to share the PDF in Facebook groups and such.

#wildfire#2023 Alberta wildfires#2023 Canadian wildfires#2023 Nova Scotia wildfires#2023 Central Canada wildfires#wildfire smoke#air pollution#vocal changes#open access#CC BY-NC-ND

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My intention for this avatar, and furthermore this blog is “gossip columns if they were published during the Renaissance.” The title ‘Sagas’ felt perfect for both its synonymity with stories, tales, and history, combined with the more casual definition of “excessive dramatic happenings". It also reflects many gossip magazine’s tendencies to rely on single-word names for their magazine. Using Artemisia Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders (1610) (from the public domain) is my attempt at evoking the idea that I am focussed on intelligent and refined subject matter... That also reads a bit like someone spreading rumours to ruin someone’s name.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet the sand cat (Felis margarita). This small, solitary feline inhabits arid regions—including Africa’s Sahara Desert and parts of Asia. Built for desert life, the thick soles of this cat’s paws allow it to walk on scorching sand during the day and cold sand at night. In parts of its range, daytime temperatures can soar up to 124° Fahrenheit (51° C) and then plummet to 31° Fahrenheit (-0.5° C) by night. The sand cat is also a “fearless snake hunter” known to pursue snakes (even venomous vipers) for a meal.

Photo: Cloudtail the Snow Leopard, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, flickr

#science#nature#natural history#animals#cool animals#did you know#animal adaptations#fact of the day#cats#cat#caturday#feline

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

These giraffe images are about 18 feet high, located on a high, curving slope at Dabous, Niger in the Aïr Mountains. They were made ca. 7000 BCE. More than 800 smaller rock engravings are nearby. Photo Matthew Paulson, 2015. Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; cropped at left.

539 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grey whale Eschrichtius robustus

Observed by susannespider, CC BY-NC-ND

#Eschrichtius robustus#grey whale#Cetacea#Balaenopteridae#cetacean#whale#North America#Mexico#Baja California Sur#Pacific Ocean#Magdalena Bay

639 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stoat by Erpak || CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Where the Light really is (2nd version)

Mixed media

2023

(Lic.: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

#dark art#neopictorialism#sepia#noughtlux#chiaroscuro#still life#roses#flowers#light#pneuma#πνεῦμα#metaphysics#figurative#mixed media#artists on tumblr#art#CC BY NC ND

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

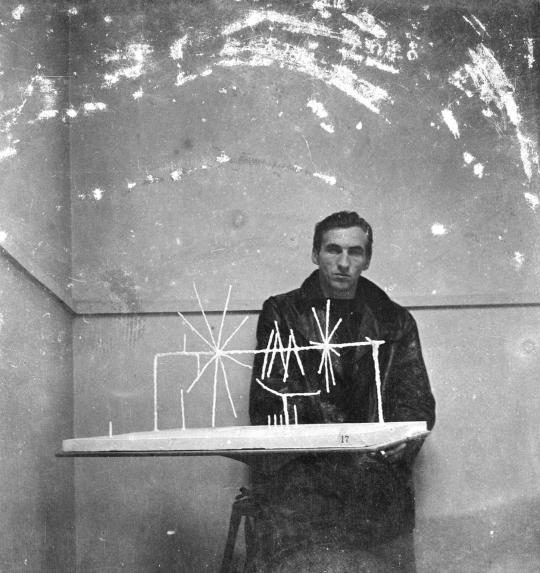

Nigel Henderson (photograph), William Turnbull with his work 'Mobile Stabile', [ca. 1949-1956] [Tate, London. © The estate of Nigel Henderson, The estate of William Turnbull. Image: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Deed]

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

the cultural heritage of mankind

As long as humans have populated this planet, drugs of various kinds have been used. Cultural history bears witness to this in many places: Mead and beer, hemp and opium, peyote and mescaline, tobacco, myrrh, frankincense, coffee, tea, betel, khat, herb or coca leaves - to name but a few - have fascinated people ever since they have been attached to some concept of pleasure. Sometimes drugs are a sacred medium of religious awakening, sometimes a means of a carnivalesque revaluation of all values. Sometimes they provide a collective ecstatic sense of purpose, sometimes they serve to make the hardships of everyday life more bearable: substances that do more than satisfy hunger and dispel thirst are firmly embedded in the cultural heritage of mankind.

Today, however, this diversity of means and motives for consumption is often minimised and instead a link between drug use and danger is suggested. The political problematisation of psychotropic substances began in the early modern period: at the beginning of the 17th century, the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV found it intolerable that tobacco and coffee houses had not only become places of consumption, but also centres of public discussion and thus places of criticism and opposition. He therefore had all tobacco houses torn down in 1633 and made smoking tobacco punishable by death. He used modern methods in the manhunt, such as undercover investigations and bogus purchases. The assets of those executed went to the sultan. Obviously, it was less about the drug itself; rather, the smoking ban fulfilled several useful functions: The criminalisation of a behaviour that was widespread on a mass scale and a sanction as part of - or under the guise of - drug control.

Until the 19th century, however, bans on drinking or smoking were rare. Since then, however, drugs and danger have become ever more closely linked, for example by the idea that all drugs inevitably lead to addiction and thus to ruin. Whenever there is talk of drugs or even "narcotics", the danger does not seem far away. The scientifically untenable but long-lasting talk of gateway drugs is proof of this - in fact, there is no reliable empirical evidence to show that the use of one drug often leads to another and thus deeper into the drug problem. Anyone who argues in this way has the slippery slope in mind, the fall that - for all those who have started - can only be avoided with great effort or not at all. Drug education in schools may have taken new, sensible paths at times. However, the actual and urgent reason for its necessity usually remains central: the danger.

However, the history of drug use is diverse and its widespread practices are only mediated, sequential or partially related to addiction and social decline. In addition, whenever people fall out of the social order, drugs were at worst a catalyst, but rarely or never the actual cause. The reluctant reference to drugs as the cause of social imbalances therefore has more the character of a handy and long-practised diversionary manoeuvre: those who hold drugs responsible do not have to talk about structural social imbalances.

It may therefore be time to turn our gaze round and look at the many and wide-ranging motives for drug use. After all, the matter of drugs is a kind of never-ending story, despite all the crusades and horrendous efforts in the so-called war on drugs. The following lines bring together - without claiming to be exhaustive, of course - a number of different reasons why people take or have taken drugs. In the process, a kaleidoscope of different episodes unfolds, the collection of which alone could illustrate how abbreviated the direct link between drugs, addiction and danger is in its contemporary form. Viewed from this perspective, i.e. detached from the overlapping perception of the problem, a different connection or at least an initial suspicion may emerge: which drugs are fashionable and how states and societies deal with them could be an expression of the respective social conditions.

Of course, this is not to say that drugs cannot tear chasms, that certain patterns of consumption sometimes lead to habits and damage health in the medium to long term. However, this is only one way among many, only one possible pattern, which also has to do with the constant social and economic marginalisation and political repression of youth cultures. The drug is only one factor. However, the almost exclusive focus on the practice of addiction and the social figure of the junkie has brought the whole subject of drugs and intoxication into disrepute and led to a sometimes bizarre practice of prohibition.

For the good!

The illustrious journey through the thicket of different reasons for drug use has countless possible beginnings and stops. The following passages of intoxicated transgression are not representative of anything, they merely show that different interpretations are possible. An arbitrary but interesting starting point is provided by a circular from the Faculty of Theology in Paris from 1444, which from today's perspective provides an irritating motivation for occasional but copious drinking. It states that "folly" is man's innate "second nature" and that "wine barrels burst if you don't open the lid from time to time and let air in. We, human beings, are poorly made wine barrels that burst from the wine of wisdom if it is left in uninterrupted fermentation of devotion and the fear of God. Therefore, on certain days we allow the folly (foolishness) in us to return to worship with all the greater fervour afterwards. "To resolve the footnote[2]

The regular drinking bouts were therefore doubly necessary: On the one hand, they were in keeping with human nature and, on the other, they were essential in order to live in a godly manner and pursue wisdom. The drunken feast, which thwarted all contemplation and fear of God, was thus part of the religious order. The culturally significant tradition of the festival, i.e. a "time between the times", has its last offshoots in today's carnival. However, there is little to suggest that much remains of the radical nature of the revaluation, of the character of the substantial time-out.

Just over a century later, the court marshal Hans von Schweinichen, whose diary entries have survived, was probably similarly drunk, albeit for completely different reasons. He was also fond of the "Tears of God" (Lacrimae Christi). He was so drunk that he "slept for two nights and two days in a row that people thought I would die". However, this did not cause him to turn away from wine. Quite the opposite: "And since then I have learnt to drink wine and have continued to do so to such an extent that I might well say it would be impossible for anyone to drink me full. But whether it brings me bliss and health, I leave to his place."

Of course, we can only speculate about Schweinichen's motives. It hardly sounds like a necessity of nature, a ritualised festivity or even a condition for religious wisdom. Rather, a kind of sporting competition without deeper meaning dominates, as is still often the case today.

Without any harm

While von Schweinichen described a social structure that apparently demanded his adaptation to alcohol, similar processes have also been passed down with regard to health aspects. Zedler's Universal Lexicon, for example, a kind of 18th century storehouse of knowledge, revealed that "opium can be used in fairly large quantities without any harm and with great benefit". It is well known that opium users "cannot refrain from it", i.e. that they cannot stop using it and, according to modern diction, become addicted. However, this is not a problem, just the opposite: "For if one is accustomed to poisonous things for a long time, they do no harm to nature. "5 The purpose of consuming opium here is to develop a habit in order to henceforth be able to enjoy the medical and psychological benefits of the substance without harm. Modern addiction research is no doubt throwing up its hands in horror. However, from a medical point of view, it is also known that opiates, appropriately dosed and consumed cleanly, trigger what we today call addiction, but cause hardly any physiological or psychological damage, provided that the social life around them functions.

At this point, however, the boundary between medication and drug becomes blurred. Strictly speaking, this boundary is only outlined either way on the basis of different consumption motives. Almost all drugs were or are also medicines - so it depends on the area of use and the reason for taking them. Opiates, for example, which include heroin, have been important substances in medicine for a very long time and still are today.

A letter to the editor that an elderly woman sent to the specialist journal "The Chemist and Druggist" in 1888 also shows how historically different the motives, practices and their categorisation as a (drug) problem are. It reads: "I have used morphine regularly for 30 years. (...) This medicine, so injurious in most cases, has done no harm whatever to my vitality. Nor has it in any degree reduced my vigour, which is very similar to that of young women, although I am now 67 years old. My zest for life is excellent, I am neither as emaciated nor as emaciated as most others who have undergone this treatment. (...) The only problem that probably stems from this medicine is that I am constantly putting on body fat. I would be extremely grateful if one of your experts would be so kind as to inform me whether my increase in adipose tissue is a natural consequence of morphine consumption. "

For medical reasons, the author of these lines had fallen into an opium habit that today would be labelled a severe addiction. At the same time, there are indications that the image of the typical addict ("neither as emaciated nor emaciated as most others") was (and is) more of a media spectre than a real experience or observation. What the woman is referring to is ultimately unclear. But the debate on addiction that emerged at the end of the 19th century was fuelled by stereotypes and exaggerated figures that correspond pretty much exactly to the typical image of the woman as a junkie. And finally, if there is an undisputed connection between the effects of opiates, then it is that they curb the appetite and can hardly be responsible for obese tendencies.

The letter to the editor shows two things quite vividly: on the one hand, it is recognisable how a modern addiction narrative creeps in and begins to re-evaluate things. The author was still very much a part of Victorian England, which had few reservations about opium. At the same time, however, she was already aware of the new era of rampant problematisation of drugs - if only to distance herself from it. On the other hand, the source also shows that debates on addiction, with their typical generalisation and focus on the compulsive nature of consumption, are to a certain extent blind to the motives, or at least less receptive to them. The same consumption practice, i.e. regular and high doses, can have many different reasons.

Between enlightenment and rebellion

A different spectrum of motives for drug use unfolds around attempts to help enlightenment with psychotropic substances. While the medieval circulars emphasised that wine-fuelled folly only provided the balance to strive for wisdom at all other times, the direct link between drugs and knowledge has a long history. The ancient Greek symposion (Latin: symposium) stands for social drinking in company, resulting in profound and perhaps philosophical conversations that lead to knowledge. The term has survived in the world of science, even if today's editions tend to shine with sobriety. The fact that there are always "symposia" on alcohol addiction is probably an unintentional punchline.

Newer versions of the link between drug and cognition focus less on social situations and more on individual experiences. To a large extent, we have the Romantic conquest of drugs in the first half of the 19th century to thank for this. Thomas De Quincey, for example - one of the first modern writers to deal with the insights and abysses of the effects of intoxication in literature - spoke in the mid-19th century of memory as a "palimpsest", i.e. a rewritable parchment that still bears all the older traces. Opium exposes these traces and therefore allows deep, otherwise hidden memories: "Life had spread a shroud of oblivion over every detail of experience. And now, on a silent command, on a rocket signal that our brain releases, this shroud is abruptly removed and the whole theatre lies bare to its depths before our eyes. This was the greatest mystery. And it is a mystery that excludes doubt - for to the martyrs of opium it repeats itself, it repeats itself ten thousand times in intoxication.

Since then, there have been many variations of profound, comprehensive, absolute, paradisiacal and constantly world-shaking insights in intoxication. The writer Charles Baudelaire stepped completely out of a purely subjective position and became a pipe smoker, only to subsequently become acquainted with the false paradise. His colleague Fitz Hugh Ludlow could "look into himself and, thanks to this appalling ability, perceive very vividly and clearly all the processes of life that take place unconsciously in the normal state". The philosopher William James did not experience his childhood as De Quincey did, but he experienced the truth quite directly: "For me, as for every other person I have heard of, the fundamental of the experience [of intoxication] consists in the tremendously thrilling sensation of a haunting metaphysical illumination." On nitrous oxide, "all the logical relations of being" were revealed.

The journey continues via the philosopher of life Ludwig Klages, who, intoxicated, experiences eternity in an instant, to the philosopher Walter Benjamin, who turns the tables differently - and more cleverly than the others - and recognises the emptiness or absence of truth in intoxication, via the writer Carlos Castaneda and on to the self-proclaimed leader of the psychedelic movement of the 1960s, Timothy Leary, who wanted to give LSD to as many people as possible. The motive for drug use is always the realisation, the hope of unravelling the mystery of life, the world or even the universe once and for all. Cultural history is full of attempts to enter into a Faustian pact with the devil in order to finally understand.

Sometimes realisation should be followed by action. Some who had seen or believed they had seen "the truth" wanted to use it in a revolutionary way and kiss a different society awake with the help of fabrics. Leary, for example, was of the opinion that the cybernetic-biological evidence, i.e. the unmediated truth of DNA, which LSD supposedly inevitably and undeniably calls to consciousness, must inevitably lead to people shedding the ridiculous mask called subject and inevitably overcoming capitalism. "Turn on, tune in, drop out" was the corresponding motto of the psychedelic revolution - which, however, failed to materialise. And the poet Allen Ginsberg, a Beat - i.e. hipster - of the first hour, declared to his Beat colleague Jack Kerouac on the phone: "I'm high and naked, and I'm the king of the universe", in order to then want to instigate the psychedelic revolution.

The drunken rebellion was not always preceded by total realisation. Sometimes drug use was and is a more or less rebellious rejection of the norms of society, of the status quo, combined with an attempt to expand the scope of freedom, even without a deeper layer. The writer William S. Burroughs and the aforementioned Beats, for example, used drugs as a provocation, as an antithesis and a means of breaking out of the puritanical straitjacket of the homophobic McCarthy era of the 1950s. And after the intoxicated euphoria of the 1960s, the motif of enlightenment faded into the background anyway. Punk became the new antithesis: a rebellion without revolution - but with drugs. Drug consumption can therefore also be motivated simply by the desire to set oneself apart from one's parents' generation and to emphasise one's own "No!" to the boredom of bourgeois life with a thick bag. Even the rave and techno movement of the 1990s had such elements of rebellion, if only because older generations didn't want to understand what this "endlessly booming music" was all about. Once again, a youth culture was spreading that wanted to cheat its parents and be different, including drug use.

Optimise yourselves!

Intoxicated realisations were booming - at present they have tended to retreat into scattered esoteric circles. And since the "new spirit of capitalism" has made rebellion the mode of accumulation, i.e. the creative class the driving force of capital, it is no longer so easy to drive parents up the wall with drug consumption. Instead, a whole spectrum of adapted consumption motives has become established; optimisation is the new trend.

In late modernity, a different place or rather a different, functional contour emerged for drug use, which nevertheless remained controversial. Since the 1990s, "avant-garde perspectives have been developing that deal with completely new types and dynamics of controlled pleasure production and functional enjoyment". In keeping with the neoliberal zeitgeist, in the context of which the individual and sometimes their intoxication became a resource, a pragmatic and purpose-orientated use of drugs shines through. As a result, consumption motives are also shifting. Drugs, which as alcohol, coffee, cigarettes or medicines are an everyday part of society, could - so the faint hope - be de-ideologised. This is primarily fuelled by the aforementioned "spirit of capitalism", which elevates flexibility and creativity to the highest economic good. The distinction between medicine and drug is becoming completely fragile, and the motives for consumption are becoming as diverse as they are customised with the new commodity form of the drug. In the foreseeable future, the flexibility of the norms will move drug consumption and intoxication out of the patterns of deviant behaviour and into a space of flexible normality. The flexible person has to learn new rules for dealing with themselves and the world and, not least, in dealing with their self-control: they only have to be careful to maintain a "reflexive distance".

Subject, substance, society

The multifaceted picture of motives or reasons for drug use presented here is truly incomplete. Other topics include Drugs for the purpose of martial disinhibition - such as Pervitin, a metamphetamine that was used en masse by Wehrmacht soldiers during the Second World War to reduce feelings of anxiety and increase performance - drugs to suppress socio-psychological baggage, drugs to speed up in order to keep up with the pace of the present and the beat, or drugs to combat the boredom of dull everyday life. On closer inspection, the different categories become blurred: Leisure and work, controlled consumption and addiction, hard and soft drugs or medication and drug. None of these pairs remains a real contradiction in the long term.

The triangle of subject, substance and society, with the help of which the Swiss historian Jakob Tanner attempts to capture the history of knowledge of the concept of addiction in the 20th century and free it from the clutches of medical self-certainty, also contributes to the dissolution. when it comes to the motives for drug consumption and its analysis. Subjective dispositions and constellations are always involved, as are the stimuli of the drug. Society always plays a decisive role, even if there is less talk of it at present, and on several levels: What is the legal status and moral connotation of drugs at what time? Are opiates regarded as a household remedy for free disposal or as the stuff of hell that inevitably leads to addiction and a crash? Or does drug use fall into the clutches of political aspirations or even movements? Is it labelled as rebellious, or does it have the reputation of holding irrefutable and earth-shattering truths? Is smoking weed a good way to start an adolescent row with the parents, or do the parents themselves like to grab a bag?

There is no doubt that motives are often mixed, and the reality of drug use makes it almost impossible to decipher things clearly. And often enough, users themselves don't know exactly why they take what. And yet it should have become clear that the link between drugs, danger and addiction does not stand up to historical scrutiny. The strong focus on the problem of drugs sometimes leaves the impression of a diversionary or evasive manoeuvre. From time to time, drugs did become dangerous to the general order, for example in the context of the counterculture of the 1960s. In each case, this led to a frenzy of lurid anti-drug propaganda, which pushed the dangers to the fore with all its might and had no inhibitions about spreading lies (for example regarding alleged chromosomal damage caused by LSD).

A kind of phenomenology of different motives and practices is therefore an important thing. Especially when the role of society in the triangle of subject and substance is taken into account. The whole subject area of drugs and drug use could ultimately serve as a kind of seismograph for different social conditions. According to a somewhat hackneyed saying, every society has the fashionable drug it deserves. This perspective could provide a whole panorama of interpretations. While the usual focus is on the influence of drugs on society (for example: "What does crystal meth do to people?"), it would be interesting to ask what influence society has on drugs, i.e. which drugs are used when, for what purpose and for what social or political reasons. The much-discussed opioid crisis in the USA might then appear to be an expression of a violently depressing time that is better tolerated with sedatives. Fast coke for top performance or weed for more creativity are then no longer the drugs of choice, but rather the painkilling opioid oxycodone or the anxiety-reducing benzodiazepine Xanax to endure the madness of late capitalism or at least the pains of transformation of a society in transition that can be felt everywhere.

Intoxicated by history

For thousands of years, humans have relied on the intoxicating effects of nature: a brief history of herbal drugs

Arno Frank

Prehistory: mushrooms in the desert

The history of plant-based drugs is almost as old as mankind. Their earliest depiction dates back to a time when even the Sahara was still a flourishing Garden of Eden and can be found in a sandstone mountain range in southern Algeria. There, prehistoric cave paintings show people with ritual headdresses dancing happily. They are holding mushrooms in their hands, from which dotted lines lead to the head - not only the oldest depiction of a drug ever, but also an artistic realisation of its effects. 10,000 years old and refer to the use of psilocybin-containing mushrooms in early advanced civilisations. The psilocyn or psilocybin they contain has a similar mind-expanding effect to LSD. It leads to a change in the state of consciousness, to waking dreams and visions, but can also cause mental disorders. Among the Aztecs, the mushrooms were known as "Teonanacatl", "flesh of the gods". The oldest surviving word for drug is also of divine origin, first written down in Sanskrit in the oldest religious texts of ancient India, the Vedas. It speaks of "soma" - at once god, plant and intoxicating juice. Scientists still puzzle over the composition of this juice to this day. It is assumed that the basis was the fly agaric.

Early times: liquid bread for the pharaoh

The mushroom went out of fashion when the first civilisations cultivated agriculture. As a result, they almost inevitably discovered alcohol, almost simultaneously in the Middle East and East Asia. The oldest recipe is Chinese, but there is also evidence of breweries in Mesopotamia and Sudan. In Egyptian mythology, it was Osiris who taught people how to brew. Although there wasn't much to teach. Barley mash, stored in a damp place, begins to ferment. The wages of the labourers on the pyramids included not only bread, but also beer. Because of its effects, beer quickly became the subject of both draconian prohibitions and festive rituals. Anyone caught drinking beer among the Sumerians could be drowned in their barrels, and on high Egyptian holidays, getting drunk together was a social event. Anyone conceived during these excesses was considered a lucky child. The Greeks were more inclined towards fermenting grapes and even had a god in Dionysus who was responsible for states of intoxication. But even in Athens, alcohol served higher purposes. In the "Symposium", people drank, but also practised philosophy with their loosened tongues.

The Middle Ages:

Good humour with the herb witchIn dark times, it was very useful to know what "an herb had grown against" - and where you could find it. Little helpers grew by the wayside, from belladonna to "fool's mushrooms" and datura. In the wrong hands, they could cause a lot of mischief. In skilful hands, the soothing substances were used for healing. A mixture of mandrake, henbane and poppy was commonly used as a "sleeping sponge" for anaesthesia. In the Middle Ages, a powerful drug was extracted from the scarified seed capsules of the poppy: opium. The juice had a healing effect, as Hildegard von Bingen noted: "And this is what you heal with." As a thickened paste with honey (called latwerge), the opium poppy was used for anaesthetic purposes and was often used under the suspicious eye of the church, which considered illness to be a punishment from God. Anyone who knew too much could quickly end up at the stake as a "herbal witch".

Early modern times: leaves for the conquerors

The leaves of the coca bush have always been chewed in South America. They helped against hunger, tiredness, cold and helped the blood to absorb oxygen. A property that also helped the coca bush to enjoy a flourishing career in the Andes. Coca was also drunk as tea and always chewed with the addition of lime or plant ash. When applied with saliva, it even had a pain-relieving effect and the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors was the first turning point. It is known that many of them not only took a liking to gold, silver and tobacco, but also conquered their new empires with coca leaves in their saddle and cheek pouches. The effects of the coca plant helped the exploiters in their plunder. As early as the 16th century, a royal accountant in Peru rejoiced: "The Indians in the mines can stay 36 hours a day without sleeping or eating." Later, the stimulant even made it into the original recipe for a world-famous US lemonade, and a second turning point was the successful isolation of cocaine from coca leaves in 1859. But that's another story and has little to do with the plant.

Today: Marijuana for the masses

Cannabis, also known as marijuana, grass, weed, pot or ganja, is something of a classic in the garden of speciality plants. Cannabis was used for medicinal or spiritual purposes in ancient China and India. Although hemp was cultivated in the West, the active ingredient - tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC for short - was not valued for a long time. In Christian tradition, it was considered exotic and dangerous. Crusaders feared the assassins of the Syrian Assassins, "hash machines", which translates as "hashish people" - the Assassins allegedly used the drug to make their followers compliant. Which is probably a legend. The consumption of weed makes most people listless. Cannabis first made a career in the West in Paris in the exclusive "club of hashish eaters". Artists and intellectuals from Victor Hugo to Charles Baudelaire and the painter Eugène Delacroix met to consume "hashish" processed into a paste with cinnamon, cloves, pistachios and butter. Their aim was to expand consciousness and heighten sensory impressions - all motives that still tempt people to smoke weed today.

Cannabis is banned in most countries, while in others a rethink is underway that is not only enabling the legalisation of cannabis (for example in the USA or Uruguay), but is also bringing the medicinal benefits of the plant into focus. THC-free CBD drops have been freely available in Germany for some time now. Their active ingredient, cannabidiol, is also relaxing - but not intoxicating.

#CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 DE#drogs#CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0-DE#Arno Frank#robert feustel#freedom of expression#human history#mod studio#reality#the cultural heritage of mankind#culture#politics#equality#freedom#headdog#artwork#Complete nonsense who can read has a clear advantage

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A Wall in Naples. Thomas Jones, about 1782

(via National Gallery, London)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Jake Johnson

Common Dreams

Sept. 5, 2023

"We are prepared to do whatever it takes, even get arrested in an act of civil disobedience, to stand up for our patients," said one Kaiser Permanente worker.

Dozens of healthcare workers were arrested in Los Angeles on Monday after sitting in the street outside of a Kaiser Permanente facility to demand that providers address dangerously low staffing levels at hospitals in California and across the country.

The civil disobedience came as the workers prepared for what could be the largest healthcare strike in U.S. history. Late last month, 85,000 Kaiser Permanente employees represented by the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions began voting on whether to authorize a strike over the nonprofit hospital system's alleged unfair labor practices during ongoing contract negotiations.

The current contract expires on September 30.

"We are burnt out, stretched thin, and fed up after years of the pandemic and chronic short staffing," Datosha Williams, a service representative at Kaiser Permanente South Bay, said Monday. "Healthcare providers are failing workers and patients, and we are at crisis levels in our hospitals and medical centers."

"Our employers take in billions of dollars in profits, yet they refuse to safely staff their facilities or pay many of their workers a living wage," Williams added. "We are prepared to do whatever it takes, even get arrested in an act of civil disobedience, to stand up for our patients."

Kaiser Permanente reported nearly $3.3 billion in net income during the first half of 2023. In 2021, Kaiser CEO Greg Adams brought in more than $16 million in total compensation.

According to the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions, the hospital system "has investments of $113 billion in the U.S. and abroad, including in fossil fuels, casinos, for-profit prisons, alcohol companies, military weapons, and more."

Healthcare workers, meanwhile, say they're being overworked and underpaid, and many are struggling to make ends meet amid high costs of living.

"We have healthcare employees leaving left and right, and we have corporate greed that is trying to pretend that this staffing shortage is not real," Jessica Cruz, a nurse at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, toldLAist.

"We are risking arrest, and the reason why we're doing it is that we need everyone to know that this crisis is real," said Cruz, who was among the 25 workers arrested during the Labor Day protest.

A recent survey of tens of thousands of healthcare workers across California found that 83% reported understaffing in their departments, and 65% said they have witnessed or heard of care being delayed or denied due to staff shortages.

Additionally, more than 40% of the workers surveyed said they feel pressured to neglect safety protocols and skip breaks or meals due to short staffing.

"It's heartbreaking to see our patients suffer from long wait times for the care they need, all because Kaiser won't put patient and worker safety first," Paula Coleman, a clinical laboratory assistant at Kaiser Permanente in Englewood, Colorado, said in a statement late last month. "We will have no choice but to vote to strike if Kaiser won't bargain in good faith and let us give patients the quality care they deserve."

A local NBC affiliate reported Monday that 99% of Colorado Kaiser employees represented by SEIU Local 105 have voted to authorize a strike.

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

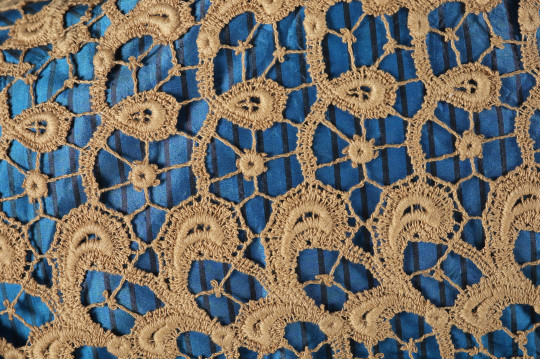

Nice day for a… blue wedding?

Indeed. Okay, no hate to white dresses here, but hasn't it been a little played out? After all, history is on our side. While white wedding dresses certainly existed before Queen Victoria, the theme still perseveres today to the point of boredom.

Take this gown from 1894. Between that bodice, the taffeta, the lace, and those absolutely over-the-top gigot sleeves, I'm in heaven. With the right hat and flowers, what look that would be coming down the aisle! Plus, you could always use it again later, you know, if things didn't turn out.

That gorgeous blue is, indeed, the product of aniline dyes (which the museum so nicely points out). Though they weren't uncommon by the time, they were still costly and impressive to behold.

Wedding dress, 1894, Wales, maker unknown. Gift of Miss C Rothwell, 1982. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Te Papa (PC002548) - Museum of New Zealand.

#threadtalk#historical costuming#silk dress#victorian fashion#costume history#history of fashion#costume#fashion history#textiles#late victorian fashion#1890s#1890s style#1890s dress#1890s fashion

510 notes

·

View notes