#1780s Netherlands

Text

Beige Chintz Dress, ca. 1780, Dutch.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#beige#Chintz#cotton#womenswear#extant garments#dress#1780#1780s#1780s Netherlands#1780s dress#1780s extant garment#V&A

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jacket (kassekijntje)

1775-1800

The Netherlands

Peabody Essex Museum (Object Number: 2012.22.13)

#jacket#fashion history#1770s#1780s#1790s#18th century#rococo era#floral#flower print#red#cotton#the netherlands#dutch#peabody essex museum#there is SO MUCH happening with this garment#also it seems this style seems to be confined to literally ONE town in the netherlands#i'm currently reading a scholarly article on it

768 notes

·

View notes

Text

ab. 1780 Gown (robe à l'anglaise) (Indian cotton chintz painted and block-printed, fabric made in Coromandel Coast, dress made in the Netherlands)

(Victoria and Albert Museum)

728 notes

·

View notes

Note

This never gets brought up enough in "why did people used to be thinner discussions". A SIGNIFICANT PERCENTAGE OF ADULTS HAD NO BLOODY TEETH. And a lot of the food tasted like garbage, of course they didn't eat much!

So, in the kindest way possible, I'd like to unpack this. Because I feel like there are some very common fallacies here.

When/where exactly are we talking about? 1780s Mediterranean France? 1960s rural Australia? New York City, 1857, upper-class neighborhood? It's possible to make some time/ place generalities when speaking broadly about cultural trends, but a lot of people talk about a nebulous Back Then so nonspecifically as to be meaningless.

My (limited) research has turned up evidence of preemptive- ie not immediately medically indicated -tooth removal and replacement with dentures, as a rare but not unheard-of practice, among young adults primarily in the UK, Australia, and Atlantic Canada around the 1920s-1970s, mostly in rural and/or working-class communities. Usually with existing tooth decay and expectations of further issues in the future. With some mentions from the US, Denmark, and the Netherlands, same time frame. So the question would then be "were people thinner in those communities at that time? if so, how much? and what role, if any, does voluntary toothlessness play in thinness if we take into account food insecurity and physical labor?"

2. People weren't necessarily thinner "back then." There are a myriad of factors that conspire to give this impression nowadays, from survivorship bias leading smaller clothes and shoes to be disproportionately represented in museums, to photo editing in eras where many of us are now unaware that it existed, to the prevalence of celebrity images over pictures of ordinary people, spotty record-keeping on the subject, improved nutrition in the modern day, beauty standards that caused people to have unhealthy but celebrated body weights, and so on. Further, the so-called "obesity epidemic" only dates back to the 1970s even among those who accept it uncritically, and the adoption of the (flawed) BMI system led many people to be newly classified as overweight who previously were not.

I highly recommend historian Kenna Libes' excellent Instagram, Stout Style History, for images of larger women in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

3. You can still eat solid food with dentures (albeit sometimes with difficulties). And a big part of this whole cultural practice was the "replace with dentures" step. For the even smaller subset of patients I've read about who did it for aesthetic reasons, that was the whole point- like capping teeth today. So that's not necessarily an impediment to eating, and therefore to eating-related weight gain/maintenance.

4. Many people in many eras liked their food, or at least some of it. I know the food in mid-20th-century Britain- a nexus of voluntary tooth removal in my research, and I'm guessing where you're from due to the use of "bloody" -is notorious now, and every period and place has folks who aren't fans of some common dishes. But it's hard to believe that these people (especially after first one war with rationing and then another) were turning up their noses enough to lose significant weight, or maintain non-genetic extremely low body weights unrelated to physical labor, sports, etc.. Tastes change- in my own country, the USA, I have to believe that SOMEBODY liked those fluorescent Jell-O salads, or there wouldn't be so many recipes for them.

I hope this doesn't come off too critical or combative; I just had many Thoughts on the premise of your ask.

#ask#anon#teeth#dental trauma#tooth trauma#dental#medical#history#long post#fatphobia mention#disordered eating mention#diet culture mention

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacques-Albert Senave - View of the pont Rouge and the tips of the islands of Saint-Louis and the Cité - 1791

oil on canvas, height: 73 cm (28.7 in); width: 92 cm (36.2 in)

Musée Carnavalet, city of Paris, Musée de la Ville de Paris

Jacques-Albert Senave (1758–1823) was a Flemish painter mainly active in Paris during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He is known for his genre scenes, history paintings, landscapes, city views, market scenes and portraits.

He was born as the son of a baker on 12 September 1758 in Lo, then in the Austrian Netherlands. He began his artistic training with the encouragement of Mr. Hennekin, a canon at the abbey of his native town who had seen his drawings. The canon egged on his parents to send him to study at the academy in Dunkirk. As his family was poor, he was sent to a baker in Dunkirk whom he was to assist in the bakery during the day, so that he could practice his art at the academy in the evenings. As gradually he had to spend more time working in the bakery, his art studies suffered and he returned to live with his parents. He was able to resume his studies in Dunkirk with the financial support of a Mr. Truit who was one of his teachers at the academy. After graduating from the academy of Dunkirk he followed Mr. Truit to Saint-Omer where the latter had been appointed a teacher at the local school of drawing. After a year in Saint-Omer, Mr. Hennekin procured for him a commission to decorate a pavilion in his hometown Lo which Mr. Hennekin (who was also an architect) had designed for a local family.

The money earned from this commission allowed Senave to travel to Paris in 1780. Here he continued his studies at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture for a few months until his money ran out. He returned to his hometown where he worked on local commissions for religious institutions and local dignitaries. Through contacts of his patron the abbot Hennekin he was admitted as a student in the academy of Ypres. In Ypres he was also introduced to prominent art lovers. The bishop of Ypres Felix Josephus Hubertus de Wavrans became his patron. Senave painted portraits and other subjects for the bishop.

His earnings allowed him to return to the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture in Paris where he obtained third prize in drawing and later second prize in life drawing. In Paris he also received training from his fellow Flemish painter Joseph-Benoît Suvée. He started to sell small genre paintings in the Flemish style which earned him some success. He married and had a son who followed in his father's footsteps and became a painter. The son died at age 22 and as a result of the grief over this early death, the wife of Senave died not long after.

He developed an interest in poetry and wrote poems in French and Dutch. He regularly contributed his paintings to the Salons in Paris.

After donating to the Painting Academy of Ypres a painting depicting Rembrandt in his workshop (destroyed during World War I), Senave was appointed Honorary Director of the Academy in 1821. His donated work formed the beginning of the art collection of the City Museum of Ypres. He also received the honor of being made an honorary member of the Royal Society of Fine Arts and Literature of Ghent. In his later years his right side was paralyzed and he learned to draw with his left hand. However, he could no longer paint. He later married a second time with the woman who took care of him during his final years.

Senave died in Paris in 1823.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The many faces of John Quincy Adams based upon his portrait by John Singleton Copley.

In 1797, Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, quite unexpectedly received a shipping case. It contained this portrait of her twenty-eight-year-old son by John Singleton Copley, which Mrs. Susanna Copley had asked her husband to paint as a gift for her old friend. Abigail was delighted, and she wrote to John Quincy Adams on June 23, 1797, “It is allowed to be as fine a portrait as ever was taken, and what renders it peculiarly valuable to me is the expression, the animation, the true Character which gives it so pleasing a likeness . . . It is most elegantly Framed, and is painted in a masterly manner. No present could have been more acceptable.” John and Abigail Adams had visited London in the 1780s and had become friends with the artist and his wife, and Copley had painted a full-length portrait of John Adams in 1783. Copley had also painted a likeness of Abigail Adams, daughter of John and Abigail Adams, probably at about the same time, which was subsequently destroyed by fire.

John Quincy Adams responded to his mother in a letter dated July 29, 1797, enlightening her on the circumstances under which his portrait had been painted:

"The history of the Portrait which you received last March was this. While I was here, the last time, Mr. Copley told me that Mrs. Copley had long been wishing to send you some token of her remembrance and regard, and thinking that a likeness of your Son, would answer the purpose, requested me to sit to him; which I did accordingly and he produced a very excellent picture, as you see. I had it framed in a manner which might correspond to the merit of the painting, and after I left this Country it was sent out by Mr. Copley. . . . It is therefore to the delicate politeness of Mr. and Mrs. Copley, that we are indebted for a present so flattering to me, and in your maternal kindness so acceptable to you. They are well, with all their family and continue to remember you with affection."

John Quincy Adams was serving as the United States Minister to the Netherlands in 1796 when he sat for Copley, having been appointed by President George Washington in 1794. He was resident in London for several months in 1795 and 1796 to conduct negotiations concerning the ratification of the Jay Treaty, which resolved many issues remaining from the American Revolution. Even though Adams was a relatively young man, he had been chosen for these important positions because of his extraordinary education and upbringing. Since he had often accompanied his father when he was sent to Europe on government business, the younger Adams had traveled to France, Spain, the Low Countries, England, the German States, Russia, and Sweden by the time he was seventeen. Often John Adams’s business required lengthy stays, and John Quincy Adams had therefore been enrolled in schools in Paris and Amsterdam. Back in the United States in 1786, Adams entered Harvard College, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated the following year. Subsequently he studied law in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and then began to practice law in Boston.

Adams recorded seven sittings for his portrait from February to April 1796. Two of the notations provide an elucidating glimpse into the experience of posing for Copley. On March 4 he wrote: “At Mr. Copley’s all the morning sitting for my picture. Conversation with him political, metaphysical, and critical. His opinions not accurate, but well meaning.” On March 28: “At Mr. Copley’s all morning, sitting again for my picture. Stayed there too long gazing at his Charles [Charles I ], and at a portrait of the three youngest princesses [The Three Youngest Daughters of King George III, 1785, Royal Collection, United Kingdom], a finely finished thing.”

In a stylish oval format, the portrait shows a rather debonair John Quincy Adams with powdered hair, dressed in a black frock coat with a white stock and a glimpse of a pink waistcoat. He is set against a red curtain and a crepuscular landscape. Copley carefully delineated Adams’s features but painted the costume and background with dashing and loose brushwork.

Shortly after the portrait was completed, Adams became engaged to Louisa Catherine Johnson in London. He went on to a brilliant political career, serving in the United States Senate, as Minister to Russia, as Minister to England, and as Secretary of State. In 1825 he was elected the sixth president of the United States, and after he lost his bid for re-election, he represented Plymouth, Massachusetts, in Congress for the rest of his life. Adams also went on to have his portrait painted by many of the leading artists of his day; in all he sat for at least sixty likenesses. Of all these portraits, Adams decided that “Copley’s Portrait of 1796, Stuart’s head of 1825, and Durand’s of 1836 . . . are the only ones worthy of being preserved.

#founding fathers#presidents#john quincy adams#digitalyarbs#amrev#american revolution#historical figures

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

is there anyone who knows anything about how courting worked in the netherlands between like 1780–1810-ish asking for me bc the internet is a nightmare 😭💀

#historical fiction writers you have my roses because wth this is a nightmare#i’m so used to just making shit up that now i’m like🧍♂️#talking#s: btaf

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

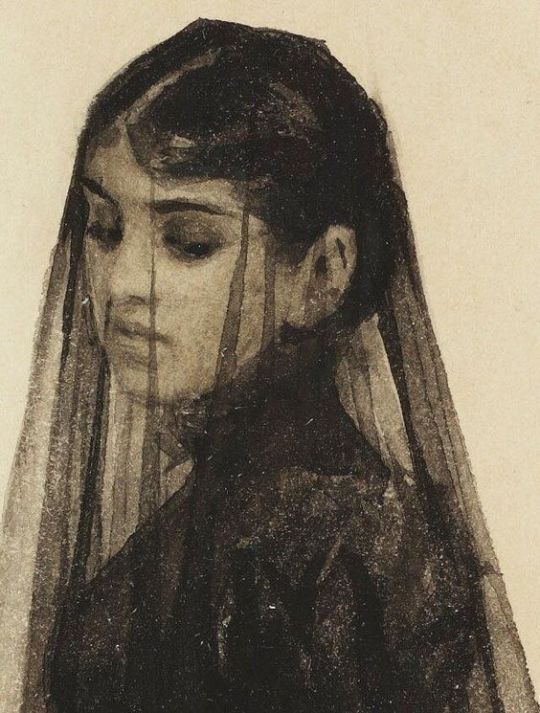

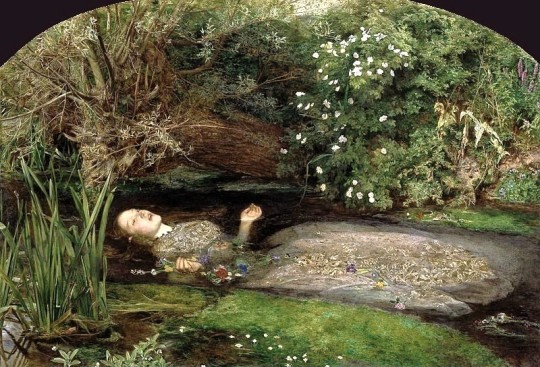

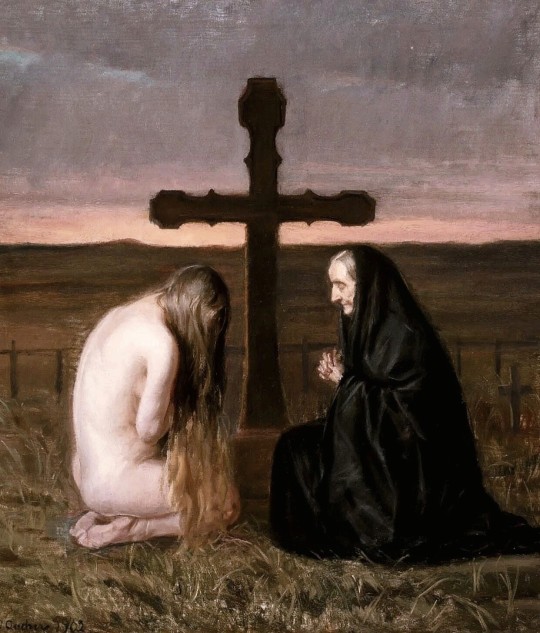

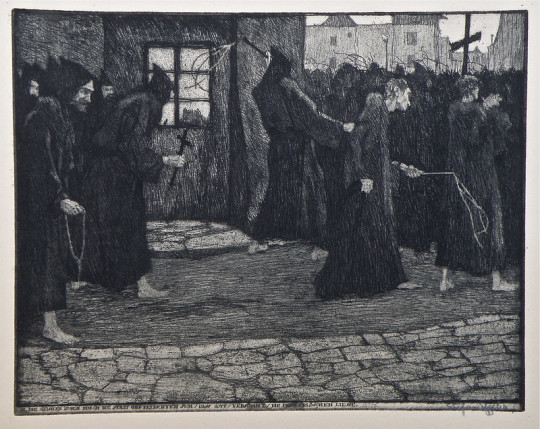

La Morte

The sick child, 1896 | Edvard Munch (1863-1944, Norway)

Funerale bianco (White funeral), 1901 | Edoardo Berta (1867-1931, Italia)

Autoritratto macabro (macabre self-portrait), 1899 | Carlo Fornara (1871-1968, Italia)

Tombe romane (roman tombs), Concordia (Venice), 1887 | Filippo Franzoni (1857-1911, Switzerland)

Miseria, 1886 | Cristóbal Rojas (1857-1890, Venezuela)

Böcklin's grave, 1901-02 (Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe) | Ferdinand Keller (1876-1958, Germany)

The widow (detail), 1882-83 | Anders Zorn (1860-1920, Sweden)

L’adultera o La femme de Claude, 1877 (Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Torino) | Francesco Mosso (1848-1877, Italia)

The funeral of Shelley, 1889 | Louis Édouard Fournier (1857-1917, France)

La peine de mort | Félicien Rops (1833-1898, Belgium)

Funeral at sea (on the death of the painter David Wilkie), 1842 (Tate Gallery, London) | William Turner (1775-1851, England)

La mort de Marat, 1793 (Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts, Bruxelles) | Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825, France)

Le jour des morts, 1859 (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux) | William Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905, France)

Bradamante at Merlin's tomb, 1820 | Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard (1780-1850, France)

Death on the pale horse, 1865 | Gustave Doré (1832-1883, France)

Il trionfo della morte, 1464 ca. (Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo) | Anonimo

Roman widow | Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882, England)

Cemetery in the moonlight, 1822 | Carl Gustav Carus (1789-1869, Germany)

The plague, 1898 | Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901, Switzerland)

Ophelia, 1851-52 (Tate Britain, London) | John Everett Millais (1829-1996, England)

Grief, 1902 | Anna Ancher (1859-1935, Denmark)

The plague of pestilence, portfolio (two of seven etchings), 1920 | Stefan Eggeler (1894-1969, Austria)

The plague of pestilence, portfolio (three of seven etchings), 1920 | Stefan Eggeler (1894-1969, Austria)

Dr. Nicolaes Tulp's anatomy lesson, 1632 | Rembrandt (1606-1669, Netherlands)

La sepoltura del conte di Orgaz (El Entierro del conde de Orgaz), 1586 (Chiesa di Santo Tomé, Toledo) | El Greco (1541-1614, Greece)

Woman on her deathbed, 1883 (Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo) | Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890, Netherlands)

Princess Tarakanova, in the Peter and Paul Fortress at the time of the flood, 1864 | Konstantin Flavitsky (1830-1866, Russia)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fan, 1780, Netherlands.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hamiltons and their Dutch Reformed wedding

[Text from Religions of the United States in Practice, Volume 1].

Alexander Hamilton and Elizabeth Schuyler were married on Thursday, December 14, 1780, in the largest parlor of her parents’ Albany mansion, by a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, as is recorded in the church registry of the Reformed Dutch Church of Albany (now First Church in Albany). Domine Eilardus Westerlo,* the second husband of Catharina Livingston Van Rensselaer (mother of Stephen Van Rensselaer III) had presided at Angelica and John Church’s wedding at the Van Rensselaer Manor house north of Albany three years prior, but it’s unknown to me if he also was the minister for the Hamilton wedding.

It’s easy to speculate that AH, at least, thought that he and Eliza would be married at Morristown that spring 1780 - it was not common to have an engagement lasting several months, and it would have made sense to get married before the campaign. Morristown had both Anglican and Presbyterian ministers. But Philip Schuyler poured cold water on that, stating in a letter that it would not be proper for them to be married at Morristown (and certainly, not to elope). In one of his letters to his fiancee AH complains that their engagement has lasted “an age,” and in another asks if she would still like to elope - it’s easy to see that he was going along with this delay to make her family happy.

If AH, who stated in 1771 that he was a member of the English Reformed Church, and then had ties through Rev. Knox to the Scotch Presbyterian Church, had mixed feelings about marrying in the Dutch Reformed tradition, it is unrecorded, although he is quoting from the Anglican marriage rite in his Oct 1780 letter to Eliza and his reference to “nuptial benediction” is from Anglicanism (I wonder if he grimaced when he read this totally non-poetic marriage rite below, compared to this one). He and Eliza’s first child, Philip, was baptized at the Reformed Dutch Church of Albany on Feb 11, 1782, with Philip’s grandparents as witnesses. And maybe AH really took the marital admonitions from this Liturgy (quoting Matthew 19) to heart [see page 3 below], as he supported folks only being allowed to divorce in the case of adultery (not for cruelty, not for abandonment), which remained NY state law until 1967.

So let’s talk cool facts about the Dutch Reformed tradition in America:

One book that every (Dutch American) colonial family was certain to possess was a kerkboekje (church book) - containing the Dutch metrical Psalter (with the Genevan tunes), the Heidelberg Catechism, and the Netherlands Liturgy - which they carried with them to church every Sunday. In more well-to-do families, every person had a kerboekje of his or her own. Because of their high birth rate, Dutch Americans were able to maintain their language and culture under the English regime for another century. Their culture was so tenacious that the French and German immigrants who later settled in the Hudson Valley adopted Dutch as their language rather than English. [Here I interject that Sojourner Truth, born into slavery in 1797 in Swartekill, NY, was a native Dutch speaker who likely never lost that accent - her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech was translated to a Southern dialect.]

After a hundred years of English rule, however, Dutch eventually lost its place as the language of New York and New Jersey.

English language preaching was introduced in 1763, and the church book was translated to English in 1767, becoming the New York Liturgy that became standard across all English-speaking Dutch Reformed Churches in the world. (Services in Albany would stay in Dutch through most of the 1780s, although I’m certainly hoping that their wedding wasn’t in Dutch, a language that I don’t believe we have any record of AH speaking.) This language certainly doesn’t have the flourishes of the Anglican liturgy - it’s pretty appalling from a literary point of view.

We know that Dutch women enjoyed stronger inheritance rights and a more elevated status than did their English peers. In cases of Dutch-English intermarriage, the couples usually ended up Dutch Reformed.

Obviously not the Hamiltons, who after Philip would baptize their next three children in the Episcopal Church (the Anglican Church of the USA) in 1788; the Hamiltons would remain Episcopalians for generations. Angelica Schuyler Church also became Episcopalian (and is the one we actually have a contemporary record of going to church with her own and the Hamilton children, other than presumed attendance for baptisms and at the 1st inauguration of GW), which makes total sense since she married an Englishman. It also makes sense that AH would return to the religious liturgies of his youth [See my lengthy post about the Hamiltons’ religious preferences.]

Getting back to the wedding stuff - although this researcher states that marriages were usually in church, I suspect that was for the plebs. Other books cite wealthy Dutch-Americans marrying at their homes, and then the bride wearing her finest outfit to church on the Sunday following her wedding. I have never found a reference to the Schuylers as a particularly pious family, nor have I found a reference to Philip Schuyler maintaining a pew for his family at the church in Albany. His youngest daughter does not cite him as an attendant, but as someone who kept private devotions and would sometimes recite a prayer service for the household (this was not at all uncommon).

Dutch American weddings were big, community, raucous affairs, almost everyone agrees. “Complaints about carousing and excessive drunkenness were not uncommon.” Philip and Catharine likely wanted to throw such a party!

Although they clearly wanted to witness and then throw a crazy party afterwards, Elizabeth’s parents would have played no role in the wedding itself. There was no giving away of the bride as there is in the Anglican rite, where the father (usually) affirms that he is giving “this woman to be married to this man.” Instead, this was a ceremony for two grown sober adults, choosing to live in the Married State, the Institution of God [see below].

Anyway, getting to the real point: below are my not-good photos of the form of marriage of the New York Liturgy. Considering the dates of this liturgy, this is likely what was read to and said by the Hamiltons at their wedding. This has some typical Reformed catechesis - “God will...judge and punish Whoremongers and Adulterers,” “Resist all Wickedness,” “Believe these Words of Christ, and be certain and assured, that our Lord God had joined you together in this holy State. You are therefore to receive, whatever befalls you therein with Patience and Thanksgiving, as from the Hand of God, and thus all Things will turn to your Advantage and Salvation.” It even starts off with such a great tone: “Whereas Married Persons are generally, by Reason of Sin, subject to many Troubles and Afflictions...”

A line that is unfamiliar to me from other Christian marriage rites: “[to the husband]..you are to labor diligently and faithfully, in the calling wherein God hath set you, that you may maintain your Household honestly, and likewise have something to give to the poor” [my emphasis]. And I am unaware of any other major Christian marriage rite that so blatantly states St. Paul’s admonition to get married to avoid fornication. Calvinism can be so grim (my apologies to any Calvinists reading this, but not really).

If you’ve made it this far, perhaps you’d also like to read about Dutch epithalamia. Epithalamia were wedding poems/songs - more specifically, for the marital bed/consummation - that were popular all the way from the classical period (they likely arose from the very elaborate wedding rituals of the past ancient Greeks/Balkan peoples) but largely disappeared in the late 19th century and have now been forgotten. There was quite a lot of literature/pamphlets/instruction manuals(?) about how to approach one’s wedding night; epithalamia was the far more naughty/raucous cousin to this literature. But I don’t think anyone really took some of this literature seriously:

...The chapter titled ‘Bruyt’ (Bride) highlights how respectable Protestants wished newly-weds the joys of a chaste Christian marriage and advocated the creation of a devotional atmosphere before becoming one flesh. Cats’s instructions about the wedding day cover various topics, such as the behaviour of the wedding guests, the bride and groom’s mental preparation, orchestrating the mood of the wedding banquet, the symbolic meaning of the bride’s crown, conduct at the nuptial bed, and pious conversation between bride and groom.

* h/t to Dr. Tom Cutterham for this, who is also working on a biography (and working to get a publisher for said biography) on Angelica Schuyler Church “which explores the processes of bourgeois class-formation in this period through the lens of her ideas, exploits, and transatlantic voyages.” He’s already released some of his research/early thoughts on “The Labor of Bourgeois Sexuality” during this period, or listen to the podcast, in which he reads from a section of his biography on ASC’s social climbing to get her husband into Parliament, including a ‘risque’ section of a letter from Baron von Steuben to Church.

#Alexander Hamilton#Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton#Dutch Reformed Church#18th century marriage#Angelica Schuyler Church

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Purse

c.1782

Dutch

Fries Museum via Europeana

#purse#fashion history#historical fashion#accessories#1780s#rococo era#1782#18th century#floral#flower print#brown#gold#silk#linen#netherlands#europeana#fries museum

200 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am a little late to the party, but would you share something from your Willemina/WM_AU_II for the tag game? :-)

But of course, my dear!

So Willemina is a thought experiment how Europe could have looked if the Stuarts had reigned into the third quarter of the 18th century (and thus a perfect prequel, if you will, to our little story about a German Prinz Georg ;-) ) by way of Willemina, daughter of William III and Mary II.

In this version of events, Mary outlives her husband and their daughter is born only days before her father's death.

William's death changes the power politics in Europe and by the time Willemina is a teen, Mary II sees the only way of maintaining peace by marrying her daughter off to the French royal family to hopefully prevent war with France.

Only... Willemina is not into that idea at all and, aided by her childhood friend the future 2nd Earl of Albemarle, the Duchess of Orléans and her step-grandmother, absconds from Paris and makes for England.

The story is basically the kind of historical adventure I would have loved to immerse myself in when I was younger (and still do), underpinned with much darker, more serious themes such as grief and rememberance, especially where Willemina's late father's and grandfather's memory is concerned, which overshadows her upbringing.

There is constant friction between mother and daughter caused by Mary's grief for the love of her life, and the way her daughter daily reminds her of him. For Willemina, the memory of the father she only knows as a looming, sombre presence in old portraits turns into a heavy burden to the point that she would like to separate herself fully from the expectations and comparisons heaped onto her on account of this de facto stranger.

Only when she arrives in France, feeling deceived and abandoned by her mother, does she turn her thoughts to her father and, lonely as she is, starts to have conversations with him- and sometimes, he replies to her. It is left open for the reader to decide whether there is such a thing as a supernatural presence or if her conversations with him are the product of the vivid imagination of an isolated, unhappy child.

In some way, these conversations, real or not, as well as interactions with people who knew her father, give Willemina a will to fight back- and leave France for the Netherlands, from where she, accompanied by Maria Beatrice d'Este and her best friend, intends to make for England.

In doing so Willemina unintentionally helps solve a political crisis in the Netherlands when she is caught running about The Hague dressed as a boy before returning home.

Virtually un-marriable now, Mary faces that her daughter will be the last Stuart monarch.

There are a few more things going on in Willemina's reign, but suffice to say that it concludes in the early 1780s following the Treaty of Paris.

Willemina's is a story of international politics, the sometimes not all positive powers of love leaving a lasting impact for generations to come and coming-of-age in peculiar circumstances.

If you want to read an excerpt, have a peek under the cut below. Willemina and her bosom friend William, son of her father's close friend Keppel, the Earl of Albemarle, decide to do some sight-seeing in The Hague by themselves, with William working hard to keep his friend from stirring up trouble in a world she's been largely sheltered from:

“Hans,” he reminded her quietly as they stood before the Binnenhof, where her father had been born, “I think a little less exuberance would do us good— the people are staring when you talk so loudly.”

“Oh,” made his friend, her lower lip protruding disappointedly, which marked her even more for her father’s daughter.

They walked on a little further, to streets not quite as clean as they had been before, on which raggedy children played their games.

“Gentlemen,” a young beggar with a babe on her arm approached them entreatingly, and Willemina, moved, thrust a golden florin into her fingers. “For your child,” she said, and suddenly sounded strangely touched, as if that woman and her child meant something to her, as if she saw in them something she knew or recognised, and whose effects she had felt upon herself.

“You cannot spend your money so freely,” William chastised her in a hushed voice.

“You see that I can,” she said simply, “if that woman has a loaf of bread for herself and her babe these next few days, and perhaps some warming clothes, I shall have done at least two of my subjects good, as I ought to do for all of them.”

He thought her daring, and reckless, and a little bit too boyish even at times; but for all her faults and haughty airs, which were regal in a princess, yet vexing in a friend, he could not think that he had ever met a kinder, more generous soul than her, and viewing her so pensively and touched, he was convinced that once she would reach majority, she would do as she had told him there on the street. Perhaps she might fail, in some ways, at least, for a Stadtholder is not the government entire; but she would try, and the people would love her for it.

“Come, Hans,” he gently tugged her by the sleeve, and guided her back to where the streets were broader and cleaner, for fear of being robbed, for they stood out among the people there quite markedly.

“Before we go back,” Willemina asked him, “might we go and eat in a tavern? We might be among the people there.”

He had done that, of course, when travelling with his father; they had always been given the finer back rooms of these houses along the carriage roads, with white linen overspreading the tables, and the better dishes and glassware upon their table, but he had never dined in the fashion Willemina had proposed either. To her, it was another half-hour in which she could pretend to be no one of import, and be among the people who by rights should be her subjects, and who by their language and customs, brought her closer to the father she had never known, and whose loss she appeared to feel all the more acutely the older she grew.

The tavern they selected was a clean, tidy establishment, the walls washed white, and the furnishings neatly arranged and clean. Naturally, two as young as they aroused some interest, but Willemina’s commanding air taught the inn-keeper’s lady to obey without question and seat them at a table by a window. No sooner had they sat down, that ale and bread with cold cuts of meat were brought. William watched as Willemina, who could hardly be famished, seeing as there had always been food upon their travels, took great mouthfuls of everything with great appetite: she, who had partaken in feasts at Versailles could think of no greater delights and delicacies than this simple meal: it tasted of a rare freedom, he supposed, one that she must give up again upon returning to England, and into her mother’s care, but which she would savour for as long as she could.

“If he had fucked his wife rather than his bum-boys, we might perhaps have a stadtholder now, one to do us the favour and protect us from the French threat!”

“Yes, one who is of age and not a papist princess!”

Willemina raised her head, and glanced to the table from which these words had come.

“A moment if you please,” she said and rose, standing as straight as she could, and wearing an expression so cool and measured that it betrayed the reverse sentiments to lie below, at least to him; to others, the young boy Hans might have seemed merely genteelly smiling.

“Gentlemen,” Willemina said and bowed a little awkwardly, being unaccustomed to it, as she neared the table. “May I sit with you?” She did not wait for their reply, and pulled an empty chair close. The men stared at this wayward boy in confusion; some in anger.

Watching, William prayed both in his native and in the papist way that his friend would not bring about a strife, or other unpleasantness.

“I heard you talking,” she smiled, and took a sip from her glass, as if that would make her seem older and more at ease, “Jacobite libel, I say. It is known that the Stadtholder-King was devoted to his wife, the Queen.”

“And who are you?” A burly old gentleman, the most well-dressed of the lot, demanded to know.

“A friend of Orange,” Willemina replied, smiling.

“Young, and prattling like a popinjay what his father tells him to!” a second voice boomed, laughing. Willemina frowned.

“Oh, but that is commonly known.”

“Is it? What is commonly known is that the country is without a stadtholder yet again, and Louis eyeing it like a cat a fat mouse! And who to defend us? Not the French princess, that is for certain.”

“The princess,” Willemina replied with a calmness that astonished William, “has gone to France as sorry for her country as you are; but she understood it to be a duty she owes to her mother,” she explained.

“Duty to her mother?”, one of the men echoed. William noted with great surprise how all of the men appeared to listen with interest to this curious boy with the high-pitched voice that caused him, despite his height, to appear younger than his years, “a duty to the state should always supersede that of a duty to her family.”

“And trust me that she is of the same opinion as you,” Willemina nodded and took another sip from her ale. “You will not have heard the last of her,” added she, and winked at William, who sent a prayer to the heaven to open the ground beneath his feet and swallow him hole, for he dreaded that less than Willemina being discovered, or worse, whatever the Queen would have to say upon their return, especially if Willemina would be found out.

“Pray, tell us then, little politician, what we should do now,” came a mocking jeer from the farther end of the table of one not so patient, or curious, as the older man.

“You should wait,” Willemina advised plainly. “The Princess will grow, and come of age and assume her rights, of course.”

“And how would you know?”, the well-dressed elderly gentleman scoffed. “She is French now, is what she is. And we to become subject to Louis—"

“It is a truth to be acknowledged by all that the son of the late Nassau-Diez is but a babe; and Zuylestein’s progeny grown too English for the taste of the ordinary Dutchman. What other Prince of Orange is there but the English princess, inheritor of her father’s blood and spirit? A brave Hollander will never be subdued, and she loves the home which she was never so lucky as to set eyes upon; and she is not wed yet,” she replied gravely and set down her empty glass, visibly relishing in the stunned silence of the party who had, rather than unwillingly accepting her presence, commenced to crowd around her.

“You talk much, and big, for one so little,” the old man observed, “how old are you?”

“Thirteen, Mynheer.”

He whistled mockingly through his teeth, “I would have taken you for ten, with that little voice of yours, were you not so tall,” he observed as another, half under his breath, made a chuckling remark about Italian castrati.

“And how—”

“I have it on the authority by my aunt in England, who by profession moved among the circle of the princess’ party,” Willemina cut off the man glibly; it was but half a lie; the sick and lonely Princess Anne had but died the previous year, when she had gone to join her husband and eighteen babes in Heaven.

“Thirteen, and talking like that; your father—”

“Is dead, Mynheers.”

Touched and embarrassed, the men directed their eyes to their fingertips or the edge of the table; the revelation appeared to mellow them somewhat, for now, even the hardened sort addressed his friend more amiably.

“A lad like you to go about the taverns alone—” a younger man with a grave face and blond hair shook his head with genuine concern. “Where is your mother, then?” a second wanted to know, and William’s anxiety mounted to unknown heights.

“His face appears familiar,” the blond man noted, and the older man concurred as they mustered Willemina intently, as if they wished to ascertain where they had seen her before, without knowing when and where. One of them rose, and approaching the fireplace, took from the wall beside it a little print, yellowed and quite neglected in its appearance, but by habit beloved enough that its plain little frame was dusted, and adjusted to hang straight on the wall.

It showed a boy, not quite grown into his face and features; his hair, in the style of the day, cut to be shorter in the front, and falling to his shoulders in the back, with what little was visible of him dressed in armour and a lace collar long fallen out of fashion.

“There is a resemblance,” the old man, to whom all others appeared to defer, judged, “uncanny, it is the nose—“

“but not the eyes, and he is too tall, for he was short, I saw him once ride past many years ago,” the blond man shook his head.

Only then did Willemina make an effort to squint her, alas not quite so very sharp, eyes a little to read what was writ below the portrait in Dutch and Latin:

Willem Hendrick de derde Prins van Orangie

Guilhelmus Henricus

Dei gratia

Princeps Auraicæ &c.

Ætatis anno XV.

William could read from her stony features that she, for the first time since making their escape, felt something akin to fear, and with her eyes sought for him, as if he could do anything at all— but he must at least try.

“You fancy me a bastard of Orange, whom you only such a short while ago accused of the Italian vice?” she laughed, but the sound was hollow to his ear.

Quietly, he rose from his chair, and, crawling along the ground slipped below the table.

“A thief!” one of the men cried, thinking William was intent of reaching into their pockets.

“Mina, run!” he exclaimed, and then, throwing over some chairs, scrambled to his feet and did the very same thing.

“Wait— for the table over there,” he heard Mina say to the inn-keeper’s wife, who had come out to see what the commotion was, and thrust a few coins in value far exceeding the men’s beers into her hand before pushing the buxom lady to the side, and running into the street, William always close behind her.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It’s the 1780s

Top: 1780-1783 Anna Teofila Potocka by Marcello Bacciarelli (The Royal Łazienki Museum in Warsaw). From tumblr.com/blog/view/sims4rococo76/675282695253884928 2048X2689 @72 1.3Mj.

Second row left: 1780s Calendar art for February. From tumblr.com/blog/view/sims4rococo76/675282695253884928 750X1063 @72 321kj.

Second row right: Calendar art for April. From tumblr.com/blog/view/antiquelaceartist 750X1063 @72 304kj.

Third row: ca. 1785 Fashion Plate (September) by Robert Dighton (V&A). From tumblr.com/blog/view/silverfoxstole 1916X2500 @72 1.2Mj.

Fourth row: ca. 1785 The Saithwaite Family by Francis Wheatley (Metropolitan Museum of Art). From their Web site 3790X3005 @150 2.9Mj.

Fifth row left: 1785 Maria J. Hoos by Nicolas Joseph Delin (Museum De Lakenhal - Leiden, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands). From tumblr.com/blog/view/andrayblue 2048X2256 @72 989kj.

Fifth row right: ca. 1787 The Mockery by Louis-Léopold Boilly (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art - Hartford, Connecticut, USA). From tumblr.com/blog/view/history-of-fashion 1273X1538 @72 626kj. Mildly cropped.

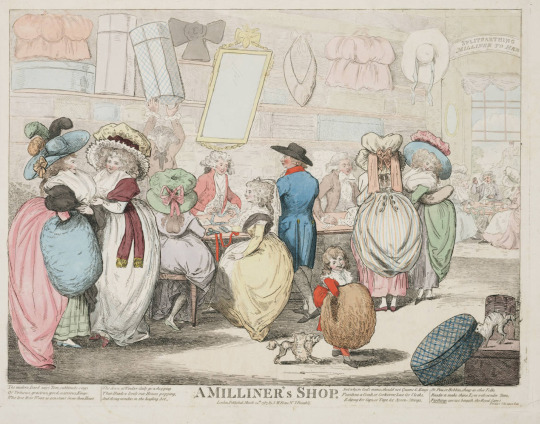

Bottom: 1787 A Milliners Shop by S. F. Fores. From sfcdyer.wordpress.com/2012/11/26/a-milliners-shop-in-1787/ 1781X1400 @400 891kj. The woman in the center wearing a yellow dress is supposed to be Queen Charlotte.

#1780s fashion#Rococo fashion#Louis XVI fashion#1785 fashion#1787 fashion#Anna Teofila Potocka#Marcello Bacciarelli#Robert Dighton#Saithwaite Family#Francis Wheatley#S. F. Fores#Maria Hoos#Nicolas Joseph Delin#curly hair#bouffant coiffure#long hair#feathered hat#hat brim#U décolletage#bertha#elbow length sleeves#lace cuffs#pleated hat#hat ribbon#three-quarter length sleeves#wrap#apron#maxi-length skirt#shoes#fichu

22 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

DeSantis said no one questioned slavery before Americans. See Van Jones ...

CHRONOLOGY-Who banned slavery when?

By Reuters Staff

3 MIN READ

(Reuters) - Britain marks 200 years on March 25 since it enacted a law banning the trans-Atlantic slave trade, although full abolition of slavery did not follow for another generation.

Following are some key dates in the trans-atlantic trade in slaves from Africa and its abolition.

1444 - First public sale of African slaves in Lagos, Portugal

1482 - Portuguese start building first permanent slave trading post at Elmina, Gold Coast, now Ghana

1510 - First slaves arrive in the Spanish colonies of South America, having travelled via Spain

1518 - First direct shipment of slaves from Africa to the Americas

1777 - State of Vermont, an independent Republic after the American Revolution, becomes first sovereign state to abolish slavery

1780s - Trans-Atlantic slave trade reaches peak

1787 - The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade founded in Britain by Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson

1792 - Denmark bans import of slaves to its West Indies colonies, although the law only took effect from 1803.

1807 - Britain passes Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, outlawing British Atlantic slave trade.

- United States passes legislation banning the slave trade, effective from start of 1808.

1811 - Spain abolishes slavery, including in its colonies, though Cuba rejects ban and continues to deal in slaves.

1813 - Sweden bans slave trading

1814 - Netherlands bans slave trading

1817 - France bans slave trading, but ban not effective until 1826

1833 - Britain passes Abolition of Slavery Act, ordering gradual abolition of slavery in all British colonies. Plantation owners in the West Indies receive 20 million pounds in compensation

- Great Britain and Spain sign a treaty prohibiting the slave trade

1819 - Portugal abolishes slave trade north of the equator

- Britain places a naval squadron off the West African coast to enforce the ban on slave trading

1823 - Britain’s Anti-Slavery Society formed. Members include William Wilberforce

1846 - Danish governor proclaims emancipation of slaves in Danish West Indies, abolishing slavery

1848 - France abolishes slavery

1851 - Brazil abolishes slave trading

1858 - Portugal abolishes slavery in its colonies, although all slaves are subject to a 20-year apprenticeship

1861 - Netherlands abolishes slavery in Dutch Caribbean colonies

1862 - U.S. President Abraham Lincoln proclaims emancipation of slaves with effect from January 1, 1863; 13th Amendment of U.S. Constitution follows in 1865 banning slavery

1886 - Slavery is abolished in Cuba

1888 - Brazil abolishes slavery

1926 - League of Nations adopts Slavery Convention abolishing slavery

1948 - United Nations General Assembly adopts Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including article stating “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

the oldest operational carousel in the world is the vermolenmolen, located in kaatsheuvel, netherlands. it was built in 1865, and was originally powered by horses.

even older, though stationary since 1932, is a carousel from 1780 in hanau, germany—where, on an unrelated note, jakob and wilhelm grimm were born only a few years after the carousel.

though carousels have existed in one form or another in many cultures around the world since the ancient times, the modern carousel can be traced back to the 12th century, when it served as a battle training device for turkish and arabian knights. while galloping in a circle, they would toss balls to one another. the balls were filled with scented water that left an unskilled player identifiable for days.

the practice later spread to europe and was especially popular in france, where a 'carrousel' meant a cavalry spectacle, where the riders had to spear small rings hung on poles in full speed. a famous carrousel was held by ludvig xiv in paris in 1662 to celebrate the birth of his heir. the site of the event is still known as 'place du carrousel'.

in the late 17th century, wooden horses came to be attached to a rotating central post to give the game a new form. the game became popular among women and children as well, and in the 18th century such make-believe carousels began to appear at fairs and gatherings around europe. these early carousels used humans or other animals to make them spin.

as a reminder of it's origins, the word carousel comes from the spanish 'carosella' and italian 'garosello, 'little battle'.

#fun fact: there are regional differences in the direction a carousel rotates#in the uk they go clockwise#elsewhere in the west counter-clockwise#idk about the rest of the world sorry#history

2 notes

·

View notes