Text

proposal, baltic writers residency, The Vampyre

[Still from “The Vampyre” (2017) by Tai Shani]

R Dorey

Proposal for Baltic Shoreside writer’s residency.

2019 Turner Prize co-winner Tai Shani has for a number of years been producing artworks as part of a series called “Dark Continent” (DC), named for Freud’s famous description of the “unknowable” sexuality of adult women. DC concerns women in proximity with overwhelmingly chaotic natural forces and isolation, and constitute a feminist project which seeks to re-examine what “woman” is beyond essentialist categories and structures.

The stories in DC are about sensation, and attempts to negotiate the indescribable. One artwork from DC that I am very interested in developing a critical text in response to is “The Vampyre”, which tells the story of the “spectral figure of an eternal vampire at the bottom of the ocean, forever caught on the threshold between life and death” (Shani, n.d.).

Two strands of my own research over the last year have been the strategies of “autotheory” and the concept of the “EcoGothic”.

Theorist David Del Principe summarises the EcoGothic as taking a “familiar Gothic subject – nature– taking a nonanthropocentric position to reconsider the role that the environment, species, and nonhumans play in the construction of monstrosity and fear”, positioning this alongside “EcoFeminism” which “seeks to question the mutual oppression of women, animals, and nature” (Del Principe, 2014, p. 1). Artist Lauren Fournier likewise positions autotheory within a “feminist genealogy” and “between academia and the art world” (Fournier, 2018, p. 642).

For the Baltic residency at Shoreside I would use the unique context of solitude and focus at the periphery of the North Sea, employing autotheory to write about The Vampyre as an EcoGothic text. The studies of autotheory and the EcoGothic are both in their early stages, and likewise Shani has only recently become the subject of a book “Our Fatal Magic” (SHANI, 2019), which reproduces the scripts from DC. The Vampyre, combined with the affective conditions of this residency would allow me to produce a creative and critical piece of writing which illuminates the overlaps in these areas of feminist study, as well as the work of an artist who is only just beginning to receive significant attention.

As a non-binary, disabled writer, this artwork and theoretical concepts are all of personal relevance, dealing as they do with the permeable borders of the idea of woman. Writers connected to autotheory such as Dodie Bellamy and Johanna Hedva have begun to make a space where disability and sickness can be creatively considered alongside power structures such as gender, race, or class. However I have yet to find writing which extends this into issues of ecology, and believe The Vampyre (which concerns the edges of the human, the ocean, the non-human, and death) offers a site to explore this further.

I believe I could make great use of this opportunity to produce a critical text from the unique conditions of the residency. The focus on personal experience to autotheory, and affect to The Vampyre, can be met through time in isolation in the proximity with nature at the point between land and sea.

Bibliography:

Bellamy, D. (2004). The letters of Mina Harker. Terrace Books, University of Wisconsin Press.

Del Principe, D. (2014). Introduction: The EcoGothic in the Long Nineteenth Century. Gothic Studies, 16(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.7227/GS.16.1.1

Fournier, L. (2018). Sick Women, Sad Girls, and Selfie Theory: Autotheory as Contemporary Feminist Practice. A/b: Auto/Biography Studies, 33(3), 643–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989575.2018.1499495

Hedva, J. (2016). Sick Woman Theory. Mask Magazine. http://www.maskmagazine.com/not-again/struggle/sick-woman-theory

Shani, T. (n.d.). DARK CONTINENT: THE VAMPYRE. Tai Shani. Retrieved 27 November 2019, from https://www.taishani.com/dark-continent-the-vampyre

SHANI, T. (2019). OUR FATAL MAGIC. STRANGE ATTRACTOR PRESS.

Smith, A., & Hughes, W. (Eds.). (2015). Ecogothic. Manchester University Press. http://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=4706038

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

PROPOSAL: Twyre is pain of the Steppe: death, dying, and the player as writer in Pathologic.

I just sent this to the excellent journal Revenant for their Apocalyptic Waste, Special Issue. I have wanted to write about Pathologic for a while, and now I am at the PhD stage of waiting for vivia/applying in vain for jobs, its good to have something to work on. I’m already doing a paper for sheffield Gothic in may, and will likely pitch a conference paper on Pathologic and Ecriture feminine for Current Research in Speculative Fiction in Liverpool this year. And with that done, here is the proposal.

Pathologic offers a dying city. [...]. A pustule encrusted town where events carry on regardless of your presence, slowly wasting away despite you. This is a fascinating game. And a very broken one (Walker, 2006).

The 2005 survival horror video game ‘Pathologic’ sees the player take control of one of three characters (‘the Thanatologist’, ‘the Haruspex’, and ‘the Changeling’) attempting to prevent, manage, cure, and explain the outbreak of a plague. The game’s manual describes it as a ‘“simulator of human behavior in the condition of pandemic”: it purports to test the user’s ability to make right decisions in times of crisis’ (Harrist, 2012).

The setting is an unspecified town bordered by a steppe, with an economy based around a huge slaughterhouse, and culture based on complex hierarchies and laws around death. The majority of a typical playthrough sees the player constantly on the verge of dying as they seek to understand the local cultures, navigate the conflicting narratives of the inhabitants, and acquire the knowledge, materials and permissions to stop the plague. Pathologic is offers a survival which is always a choice between ruinous or debasing options, searching waste bins for junk to trade with children or dissecting corpses for organs to sell to the doctor forms the game’s economy which never allows the player to accrue the capital to surpass this struggle. Outside of this, the game itself is a struggle to play, even in its 2015 HD remaster it uses deliberately limited graphics, awkward mechanics and restricted information, deploying the qualities of a broken game to further its exploration of apocalyptic crisis.

From Quintin Smith’s trilogy of articles (Smith, 2008a, 2008b, 2008c) which popularised Pathologic to English speaking audiences, to Harris ‘Hbomberguy’ Brewis’s 2 hour video analysis (Brewis, 2019) the common tension around the game is that it is both a work of art, and ‘agonizing to play’ (Harrist, 2012). I will argue that the latter is a feature of the former.

The developers ‘deliberately refuse to create a comfortable environment for the gamer. The addressee is not the consumer. [They are] the coauthor. Passing the deep game is a creative process’ (Ice-Pick Lodge, 2001). I analyze this player-role through game theorist Mary Flanagan’s concepts of ‘hyperknowledge’ and ‘rendition’, aligning the player’s navigation of game space from multiple irreconcilable points of view from a feminist philosophy of embodiment (Flanagan, 2002).

The player experience of difficulty, unreliable information, and constant proximity to death is theorised through the feminist writing practices of Hélène Cixous and Kathy Acker. Acker has conceptualised writing as dying ‘while remaining alive’ (Acker, 1990, p. 174) while Cixous approaches writing as ‘learning to die’ (Cixous, 2005, p. 10) and both offer ways of thinking of writing through its points of collapse and divergence. These writers offer a framework to examine the player-as-author while recontextualization the trauma of playing, the game’s collapsing and unreliable narratives, and the meaning of death and survival within such a creative process.

In conclusion, I argue that more than just being a game set within a nightmare space, where the environmental collapsed with the social and economic order, Pathologic demands active and complicit investment in these from the player. Pathologic is ‘hypo-ludic’ (Conway, 2012), as the game restricts conventional enjoyment through its mechanics, graphics, and morally compromising choices. The player of Pathologic is forced to engage in the creative process of roleplay in this apocalyptic waste, and in doing so both engages with feminist writing techniques and uses what game theorist Jesper Juul has identified as the unique capacity of games to make an audience complicit in tragedy (Juul, 2013).

Acker, K. (1990). In memoriam to identity (1st ed). Grove Weidenfeld.

Brewis, H. (2019, November 21). Pathologic is Genius, And Here’s Why. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JsNm2YLrk30

Cixous, H. (2005). Three steps on the ladder of writing (S. Cornell & S. Sellers, Trans.). Columbia University Press.

Conway, S. (2012). We Used to Win, We Used to Lose, We Used to Play: Simulacra, Hypo-Ludicity and the Lost Art of Losing. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 9(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.147

Dybovsky, N. (2005). On the Threshold of the Bone House, or as Game Becomes Art. (2005). I C E - P I C K. http://old.ice-pick.com/ore9_eng.htm

Dybowski, N. (2015). Pathologic Classic HD [Microsoft Windows]. G2 Games, Ice-Pick Lodge.

Flanagan, M. (2002). Hyperbodies Hyperknowledge: Women in Games, Women in Cyberpunk and Strategies of Resistance. In M. Flanagan & A. Booth (Eds.), Reload: Rethinking Women and Cyberculture. MIT Press.

Goodman, P. (2014, December 1). Pathologic Interview. The Escapist. http://www.escapistmagazine.com/articles/view/video-games/12333-Pathologic-Interview#&gid=gallery_3295&pid=1

Harrist, J. (2012, April 30). Infected Zones. Kill Screen. https://web.archive.org/web/20140815022720/http://killscreendaily.com/articles/essays/infected-zones/

Hiller, B. (2016, December 1). The new Pathologic is still one of the best games it’s no fun to actually play. VG247. https://www.vg247.com/2016/12/01/the-new-pathologic-is-still-one-of-the-best-games-its-no-fun-to-actually-play/

Hitorin, V. (2014, November 3). Pathologic: Saving the virtual world from a Russian plague. https://www.rbth.com/science_and_tech/2014/11/03/pathologic_saving_the_virtual_world_from_a_russian_plague_41037.html

Ice-Pick Lodge. (2001, March 18). Manifesto 2001. Ice-Pick Lodge. https://ice-pick.com/en/manifesto-2001/

Ilukhin, K. (2015, February 13). Pathologic: Interview with game creators. Sci-Fi and Fantasy Network. http://www.scififantasynetwork.com/pathologic-interview-with-game-creators/

Juul, J. (2013). The art of failure: An essay on the pain of playing video games. MIT Press.

Novitz, J. (2017). Scarcity and Survival Horror Trade as an Instrument of Terror in Pathologic. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 2(1), 63–88.

Smith, Q. (2008a, April 10). Butchering Pathologic – Part 1: The Body. Rock, Paper, Shotgun. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2008/04/10/butchering-pathologic-part-1-the-body/

Smith, Q. (2008b, April 11). Butchering Pathologic – Part 2: The Mind. Rock, Paper, Shotgun. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2008/04/11/butchering-pathologic-part-2-the-mind/

Smith, Q. (2008c, April 12). Butchering Pathologic – Part 3: The Soul. Rock, Paper, Shotgun. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2008/04/12/butchering-pathologic-part-3-the-soul/

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conclusions and sorrow

I've nearly finished editing the three books. I'm slightly overdue with submission, but it is what it is.

Underpinning most of my PhD research has been my ongoing relationship with the two elderly Staffordshire bull terriers that my partner and I adopted right at the start of it, around Christmas 2016.

It is with overwhelming heartbeat that yesterday, after I visit from the mobile vet, we discovered that Lea has a late stage inoperable growth. The vets are returning tomorrow and we will be saying goodbye to lea. I don't have the words yet to address the feeling of loss, or the anxiety of this ongoing 48 where I with lea at every moment to make sure she is as comfortable as possible. it's a lot. And I need to keep writing things in order to occupy my mind. So this is a draft (since edited, but that's in InDesign files I can't access from my phone) of the potential lines beyond the PhD, including the thing I worked on for a year regarding dogs, but couldn't emotionally deal with even prior to this last illness.

I could not have done this research without my relationship with Buster and Lea. The concept of care which I've addressed is as much drawn from this relationship as it is from Sedgwick. How to care for someone across the lines of different bodies and senses and desires. The concept of play as emergent collaboration equally comes from learning to play with dogs who had suffered neglect at the hands of their original owners, and then a year recovering in the noisy RSPCA kennels before they were well enough to be rehomed. I love you lea.

Conclusions and exits.

The structure and methodology of this PhD Output consisting of three approaches to a central area of art practice, and within each approach multiple overlapping attempts through the various documents, turns the issue of a conclusion into a challenge.

Rather than attempt to draw books and documents toward a unifying conclusion, erasing the differences between then, I have offered conclusions in the documents individually. Some of these are clearly labeled as such, some are more demonstrative, and some left as provocations.

Throughout the three books are indications of where future paths could proceed. For continuation of creative research and the application of concepts developed, these indications are generally placed at the end of documents. Paths which are more tangential, or areas where the research could be reinforced through engaging with a separate discipline or practitioner appear in endnotes.

In place of some kind of ending for the PhD Output as whole I will raise three of the avenues of future research not already mentioned in individual documents, that will be pursued at its end. All of these examples incorporate work already commenced, that for practical reasons has not been addressed in documents.

The Incomplete Object.

Archeologist Chantal Conneller has produced a large amount of research focused Star Carr, a Mesolithic site in Yorkshire (Conneller, 2004, 2011; Little et al., 2016; Milner, Conneller, & Taylor, 2018a, 2018b). In particular, Conneller has provided a framework for examining some of the objects recovered from the site, and through this reassess the historic inhabitants of the area’s relationship to animals and objects. The objects, twentyone of which were found during the site’s excavation by Professor J.G.D. Clark between 1949 and 1951, consist of the “uppermost part of the skull of a red deer, with the antlers still attached” and are referred to as “antler frontlets” (Conneller, 2004, p. 37). In offering an interpretation for the frontlet’s use, Clark “suggested they could have been used either as hunting aids, to permit hunters to stalk animals at close range without being seen, or as headgear in ritual dances” (Conneller, 2004, p. 37). This interpretation resulted in an impasse between a “‘functional’ and a ‘ritual’ analogy” and has according to Conneller, meant that “in the intervening 50 years they have been ignored” (Conneller, 2004, p. 37).

Conneller’s research breaches the impasse of an animal derived object needing to be either functional or ritual by use of philosopher Gilles Deleze and psychoanalyst Félix Guattari’s work in “A Thousand Plateaus” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). Firstly, Conneller outlines how in Deleuze and Guattari, “animals come to be seen [...] as an assemblage composed of a number of ways of perceiving and acting in the word” (Conneller, 2004, p. 44). In this view, animals are not singular fixed entities, and the objects derived from them are therefore not limited to being symbolic of the animal whole or else be understood only as practical material. Animals are here understood as collection of “affects” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 253), and the objects derived from them convey those Affects to the user in a manner which outside of the binary of ritual and functional. From this point Conneller proceeds to “examine the specific ways in which different things are seen to modify or extend the capacities of people in particular contexts” (Conneller, 2004, p. 51), bridging Deleuze and Guattari to theorist Donna Haraway’s concept of “situated knowledges” which replaces a fixed epistemological view with “webs of differential positioning” (D. Haraway, 1988, p. 590). The use of animal objects becomes simultaneously a process of taking on capacities as well as the ethical/epistemological/affective engagement with the world from another position.

These observations from archeology are useful not because they set some historic precedent for how art should function, but because they articulate processes which are important to art from another perspective. In the documents in this PhD Output which examine artworks I have consciously treated both the processes deployed by the artist and those of her characters in the same manner. In the art I am interested in, things are not easily split between the practical and the ritual but form processes across these lines to perform different things.

Finally, when I contacted Conneller in 2019 she was continuing to examine the frontlets of Star Carr in terms of how they function as “unfinished things”. Conneller has already observed that the frontlets were “broken up as a source of raw material” (Conneller, 2004, p. 46), but is now considering how this occurred concurrently with their uses. A framework for considering art objects which do not reach a fixed state, but are continually re-worked, and drawn from while being used is relevant to a number of documents in this PhD Output. It is relevant to the analysis of artist Tai Shani’s works (SHANI, 2019) which undergo edits between redeployments, or the ongoing work “sidekick” (Price, 2013) by Elizabeth Price. Going forward, I would consider how unfinished things connects to the writing practice of William Burruoghs both through the “cut-up” technique to “cut oneself out of language” (Hassan, 1963, p. 9), and the process whereby his novels were re-edited in subsequent editions. Burroughs is also relevant to the other side of unfinished things whereby these things are not just refined, but are a source of material for future things. I am also interested in the process by which computer software is updated via “patches” (Fisher, 2019) as another model for an unfinished thing.

I’m interested in the political implications of objects which refuse the linear transition from raw material to finished commodity, but is instead part of processes which cross that distinction. To borrow the image from Karl Marx’s Capital Vol. 1 (Marx, 1981), what would it mean for “coat” to remain functioning as “ten yards of linen”, to be always in a process of being woven/unwoven/rewoven into different forms? I feel there is something here to be pursued via the concepts of Incomplete Provocations, and the improvisations and departures which are centred in Tabletop Role Playing Games.

Divination Storytelling

The second exit is far more practical and straightforward. During my research I have used and developed methods for creating parts of narratives based on sortation systems such as card decks and dice rolls. In 2018 I produced an artwork entitled “The Sodden Gates of Vulnerability” which borrowed a mechanic used in multiple games whereby the space in which play takes places is procedurally generated. A hypothetical example of this mechanic would be a game which takes place in a derelict spaceship, the interior rooms and corridors of which is represented with cardboard tiles. When the players reach the exit of one room, a new random room tile is placed at the exit from the first, so the spaceship is configured, and unpredictable, with each subsequent playthrough. In The Sodden Gates of Vulnerability I combined some of the lore from Games Workshop’s derelict spaceship exploration game “Space Hulk” (Games Workshop, 1999) with their subsequently released rules for randomly generated spaceships (Hunt, 2013), to randomly generate prompts for a narrative built from a fictionalised version of my own past.

As a result of the cessation symptoms I was experiencing while coming off antidepressants I found memories returning that medication use had suppressed. In addition, there were physical cessation symptoms which mnemonically triggered some often confused memories of spaces in the town centre of Luton where I spent my teens, frequently from times in the early hours of the morning after leaving a club or a party. I reconstructed these fragmented memories, and the bodily feelings which connected them to the present, and any emergent feelings and noted them down as prompts on index cards. Some memories were so abstract as to not describe a place but just a sensation, or an action. These abstract memories, combined with some other images and thoughts were written up in a list and labeled 1-20.

The Sodden Gates of Vulnerability was produced as a single take spoken performance to microphone. It began with a short reflection on the different ways in which physical geography and brain chemistry are both modulated by chemicals. After this I shuffled and dealt an index card, describing the derelict spaceship/ 4am Luton Town Centre space it represented in the manner of Games Master setting a scene for players of a Role Playing Game. I then rolled a 20 sided dice and used the corresponding entry from the list as a prompt for what the player (the audience to whom the work is addressed) did in traversing this space. A partial transcription of one room follows;

“You stagger out of the thickening fog into the area where escaping heat from the many times kicked in door makes a dim pocket at the edge of the street. Banging on the door that feels like it should have given in by now and it is finally opened by someone inside. You roll in, and so does the fog, and the door opener is already turning the corner ahead into the living room so you guess you will follow them, remembering to shut the door behind you.

The living room is thick with dust and hair and ash over the brown carpet and old sofas. No one has their feet on the floor, all bunched up to keep warm or to manage some symptoms of intake.

You just want to buy, but that isn't how this is going to work out. It never does.

Everything slips. Someone makes you take a music cassette and in lock-eyed intensity tells you why you will like it and when you will die.

A man takes you to one side and rapidly ages while sharing with you a one sided conversation about how he has lived his life. He has little ears like fins and catfish whiskers and it's clear from the way he holds and interacts with the portable stereo he cradles that he has a relationship with Fabio and Grooverider which is both more beastially physical and more vapourusly transcendental than you will ever understand.

You slip out and it's dawn and you have the cassette and you don't think you bought anything but now do not think you need anything so maybe you bought it and weren't paying attention during intake or maybe someone else was in charge of your body.

You roll out with the fog and luckily town is down hill but my god you would never be able to find this place again and my god you would probably never want to because all those people would want to check how closely you been following their advice on how to live.

Oh yeah the plot twist is you're a rabbit”.

Going forward, I would like to explore the mechanics of procedural narrative based on sortation systems, both as an improvised Rendition, and as material which is subsequently cut up and deployed in other ways, possibly as a development of Diagramatics. I’m looking into how I might produce these works for a platform like YouTube, possible using a split screen where half the image shows the face that speaks, and half shows the sortation system such as tarot-style cards.

Dog Mod

Running throughout all three books of this PhD Output are dogs. When I started this PhD in 2016, I soon afterward began living with Lea and Buster, two elderly Staffordshire Bull Terriers. The importance of this relationship to the research is something I have attempted, and failed, to articulate on many occasions in the last three years. As much as the majority of the documents in this PhD Output are underpinned by a desire to understand my own trans* non-binary gender identity, they are also a response to learning about what Deleuze and Guattari would call dog affects, as well as negotiating my emotions towards Lea and Buster particually during the sadly increasing points where they have become unwell.

In mid 2019 I sketched an outline for what I called the “Dog Mod”. In the language of games, a mod is something added to the game which alters part or all of its systems in some way. Mods are often produced by a third party, and can range from something which simply adds some different functionality (such as the campaign generator for Space Hulk referenced in the previous section) or completely reorientate the system, such as the mod “DayZ” that reconfigures military sim “ARMA” into a zombie survival game and spawned an entire genre of video games (Davison, 2014).

The aim of Dog Mod was to produce a document which could provide a means to reconfigure the rest of the PhD Output through its unspoken focus, dogs. Dog Mod is something I decided was both conceptually and emotionally too overwhelming for me to be able to complete in time for submission, but I remains as a point of departure for my future research. It connects the Becoming-Animal of Deleuze and Guattari (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987; Stark & Roffe, 2015), philosopher Patricia MacCormack’s expansion of this into animal rights discourse in the Ahuman (MacCormack, 2014), with other ideas around, animals, play and care (Chen, 2012; D. J. Haraway, 2016; Massumi, 2014; Vint, 2008).

Bibliography

Anckorn, J. E. (2019, October 24). Does The Dog Die?: A Not-At-All Comprehensive Guide to Stephen King’s Canines. Retrieved 26 November 2019, from We Are the Mutants website: https://wearethemutants.com/2019/10/24/does-the-dog-die-a-not-at-all-comprehensive-guide-to-stephen-kings-canines/

Chen, M. (2012). Animacies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Conneller, C. (2004). Becoming Deer: Corporeal Transformations at Star Carr. Archaeological Dialogues, 11(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203804001357

Conneller, C. (2011). An archaeology of materials: Substantial transformations in early prehistoric Europe. New York: Routledge.

Davison, P. (2014, April 30). Bohemia Interactive Tells the Story of Arma and DayZ. Retrieved 30 December 2019, from USgamer website: https://www.usgamer.net/articles/bohemia-interactive-tells-the-story-of-arma-and-dayz

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Fisher, T. (2019, December 17). What Are Software Patches? Retrieved 30 December 2019, from Lifewire website: https://www.lifewire.com/what-is-a-patch-2625960

Games Workshop. (1999). Space Hulk Rule Book (4th Edition). Nottingham: Games Workshop.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hassan, I. (1963). The Subtracting Machine: The Work of William Burroughs. Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, 6(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00111619.1963.10689760

Hunt, C. A. T. (2013). Campaign Generator Geotiles. Games Workshop.

Little, A., Elliott, B., Conneller, C., Pomstra, D., Evans, A. A., Fitton, L. C., … Milner, N. (2016). Technological Analysis of the World’s Earliest Shamanic Costume: A Multi-Scalar, Experimental Study of a Red Deer Headdress from the Early Holocene Site of Star Carr, North Yorkshire, UK. PLOS ONE, 11(4), e0152136. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152136

MacCormack, P. (2014). The Animal Catalyst: Towards Ahuman Theory. A&C Black.

Marx, K. (1981). Capital: A critique of political economy (B. Fowkes & D. Fernbach, Trans.). London ; New York, N.Y: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review.

Massumi, B. (2014). What animals teach us about politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Milner, N., Conneller, C., & Taylor, B. (Eds.). (2018a). Star Carr Volume I: A Persistent Place in a Changing World. https://doi.org/10.22599/book1

Milner, N., Conneller, C., & Taylor, B. (Eds.). (2018b). Star Carr Volume II: Studies in Technology, Subsistence and Environment. https://doi.org/10.22599/book2

Price, E. (2013). Sidekick. In K. Macleod, Thinking Through Art: Reflections on Art as Research (1st ed., pp. 122–132). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203819869

SHANI, T. (2019). OUR FATAL MAGIC. London: STRANGE ATTRACTOR PRESS.

Stark, H., & Roffe, J. (Eds.). (2015). Deleuze and the non/human. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Vint, S. (2008). ‘The Animals in That Country’: Science Fiction and Animal Studies. Science Fiction Studies, 35(2), 177–188.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Proposal: Gothic Vectors and Gothic Lacuna: Gender, Reparative Love, and Unseen Agency in Tai Shani’s “Phantasmagoregasm”

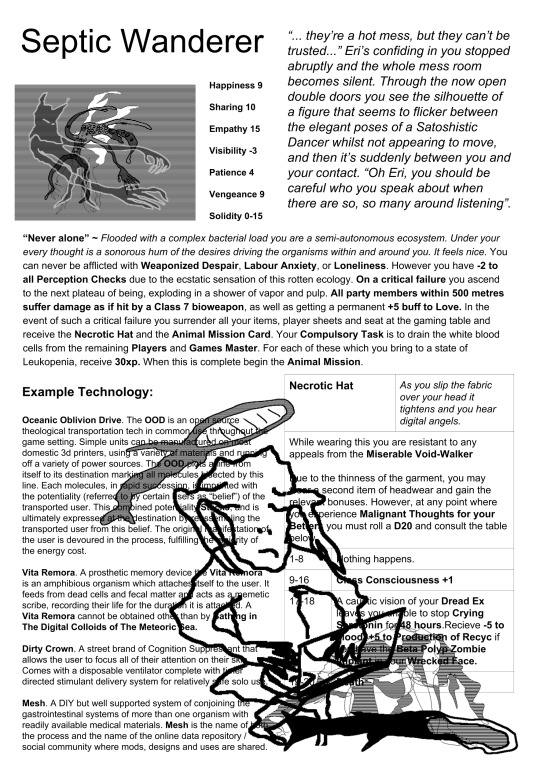

Figure 1. Phantasmagoregasm Production Print. Reprinted from "Tai Shani", by Shani, T, 2019, Retrieved from https://www.taishani.com/shop/dark-continent-productions-print-set. Copyright 2019 by Tai Shani.

This is a proposal I’ve just sent this morning for the Sheffield Gothic conf. the deadline is the 9ths so still time to submit something. http://sheffieldgothicreadinggroup.blogspot.com/

The artist and 2019 Turner Prize collective winner Tai Shani has since 2014 produced artworks as part of a project called Dark Continent (DC), named for Freud's description of the sexuality of adult women (Freud, 2002, p. 90). DC takes inspiration from texts such as Christine de Pizan’s proto-feminist work “City of Women”, adapting and deviating from them to question “what consitutes the feminine” through a “messier and more agnostic model of gender that moves beyond the binarism of Pizan” (Crone, 2019, p. xi).

One artwork within DC is “Phantasmagoregasm” (Shani, 2018, 2019, n.d.), a narrative delivered by its titular character “an eighteenth-century hermaphrodite writer of gothic fiction” (Shani, 2019) which explicitly references Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Fall of The House of Usher” in its concern for the protean interrelations of bodies, objects, buildings, and affects. Shani however, offers a radical redeployment of the tropes and structures of the gothic, just as she does with those of gender.

Firstly, I draw from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s concept of “reparative reading” (Sedgwick, 2002) with its calls back to Sedwick’s analysis of the gothic forms (Sedgwick, 1986), to consider how Phantasmagoregasm replaces the underpinning gothic presumption of paranoia, with queer care and love, via absense and affect. The reparative gothic position is used as a means to approach one of psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray’s rare direct addresses to art, “The Natal Lacuna” (Irigaray, 1994, 2006), and its related debates (MacCormack & McPhee, 2014; Robinson, 1994, 2006; Whitford, 1994).

Secondly, I identify how, as a reconfiguration of the gothic form of barriers and transgressions, Phantasmagoregasm is concerned with vectors and pathways for energies witnessed only through their effects, particularly the repeated literary description of rapidly moving disembodied points of view, sound waves, wind, and abstract geometry. This “Vectorial Gothic” in Shani’s work is considered through the metaphor of director Sam Raimi’s agentic camera in “The Evil Dead” movies (Campbell, 2002; Raimi, 1981, 1987; Raimi & Spiegel, 1986; Semley, 2019), in order to create another approach to Irigaray’s text, via Sedgwick and theorist Katherine Hayles writing on Poe (Hayles, 1990).

In conclusion, I consider how the queering of Gothic Desire and Gothic Space in Phantasmagoregasm readdresses structures of sexual difference and illuminates a feminist approach to art practice concerned with affect, love, and the negotiation of the unknown, or undescribable.

Bibliography:

Campbell, B. (2002). If chins could kill: Confessions of a B movie actor: an autobiography (1st St. Martin's Griffin ed). New York: LA Weekly Books for Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press.

Crone, B. (2019). Wounds of Un-Becoming. In Our Fatal Magic (pp. vii–xxiii). S.l.: STRANGE ATTRACTOR PRESS.

Freud, S. (2002). Wild Analysis (A. Phillips, Ed.; A. Bance, Trans.). Retrieved from http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/51108791.html

Graves, R. (2018). Tai Shani: Semiramis. Retrieved 27 November 2019, from Corridor8 website: https://corridor8.co.uk/article/tai-shani-semiramis/

Hayles, K. (1990). Chaos bound: Orderly disorder in contemporary literature and science. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press.

Irigaray, L. (1994, June). A Natal Lacuna (M. Whitford, Trans.). Women’s Art Magazine, (58), 11–13.

Irigaray, L. (2006). The Natal Lacuna. In S. Lotringer (Ed.), & B. Edwards (Trans.), More & less 3: : Hallucination of Theory (pp. 39–43). Pasadena, CA; Cambridge, MA: Fine Arts Graduate Studies Program and the Theory, Criticism and Curatorial Studies and Practice Graduate Programs, Art Center College of Design ; Distribution, MIT Press.

MacCormack, P., & McPhee, R. (2014). Creative Aproduction: Mucous and the Blank. InterAlia Special Issue: Bodily Fluids, (9), 146–164.

Raimi, S. (1981). The Evil Dead. Retrieved from http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0083907/

Raimi, S. (1987). Evil Dead II. Retrieved from http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0092991/

Raimi, S., & Spiegel, S. (1986, May 5). Evil Dead II Shooting Script, Seventh Draft. Retrieved from http://www.bookofthedead.ws/website/evil_dead_2_in-print.html

Robinson, H. (1994, December). Irigaray’s Imaginings. Women’s Art Magazine, (61), 20.

Robinson, H. (2006). Reading art, reading Irigaray: The politics of art by women. London: I. B. Tauris.

Sedgwick, E. K. (1986). The coherence of Gothic conventions. New York: Methuen.

Sedgwick, E. K. (2003). Touching feeling: Affect, pedagogy, performativity. Durham: Duke University Press.

Semley, J. (2019). Naturom Demonto. How The Evil Dead Claims Evil from Both Literature and Cinema. In R. A. Riekki & J. A. Sartain (Eds.), The many lives of The evil dead: Essays on the cult film franchise (pp. 41–50). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Shani, T. (2018). PhantasmagoregasmFinal.pdf.

Shani, T. (2019). Phantasmagoregasm. In OUR FATAL MAGIC. (pp. 139–153). S.l.: STRANGE ATTRACTOR PRESS.

Shani, T. (n.d.-a). DARK CONTINENT. Retrieved 27 November 2019, from Tai Shani website: https://www.taishani.com/dark-continent

Shani, T. (n.d.-b). DARK CONTINENT: PHANTASMAGOREGASM. Retrieved 27 November 2019, from Tai Shani website: https://www.taishani.com/darkcontinentphantasmagoregasm

Westengard, L. (2019). Gothic queer culture: Marginalized communities and the ghosts of insidious trauma. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Whitford, M. (1994, October). Woman With Attitude. Women’s Art Magazine, (60), 15–17.

#horror#feminism#queer#edgar allan poe#luce irigaray#eve kosofsky sedgwick#reparative reading#art#evil dead#voids#lacuna#vectors#trajectories

1 note

·

View note

Text

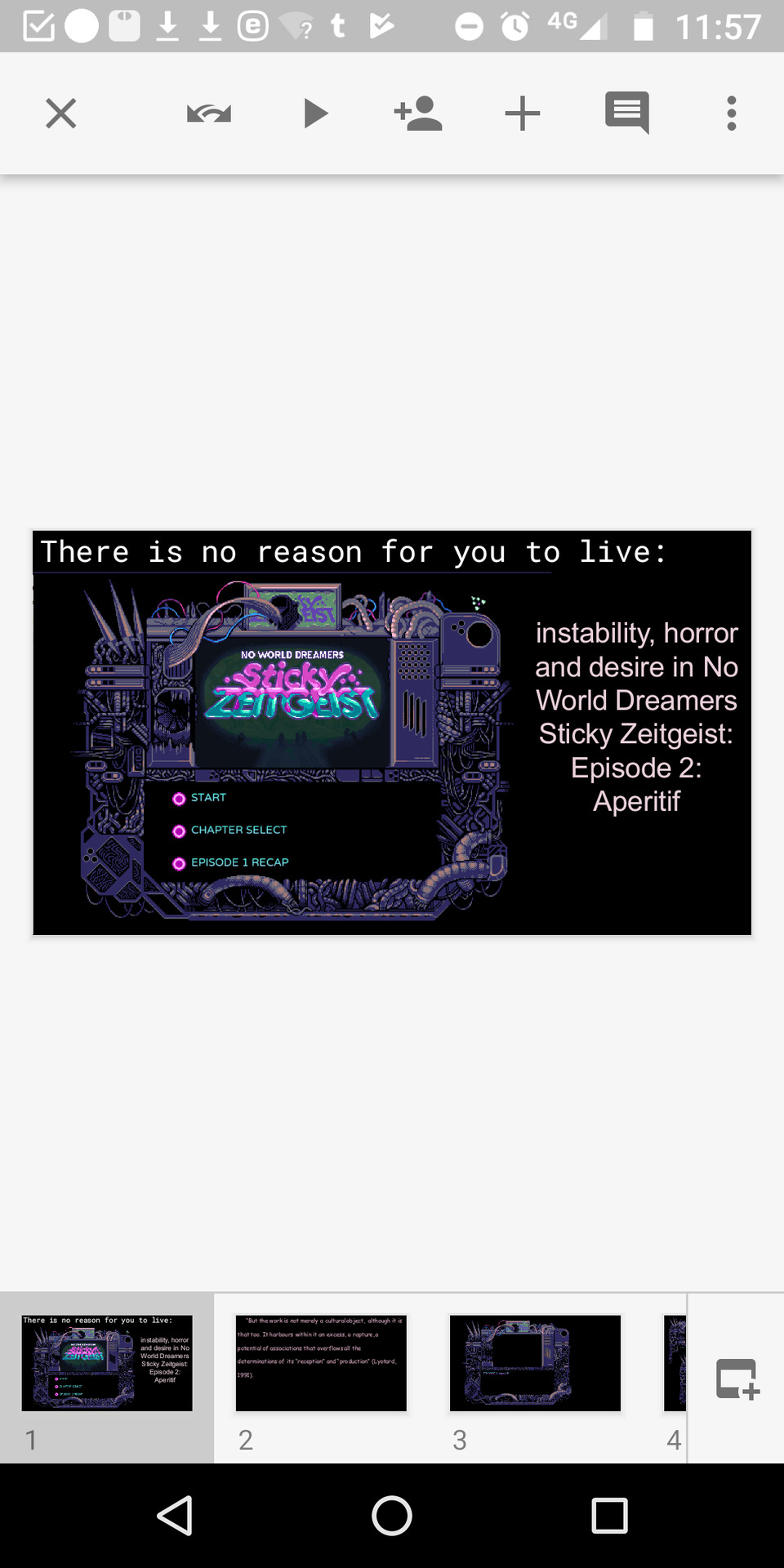

There is No Reason for you to Live. Part two: Excess

This is part of chapter I have written in the last two weeks, which uses the game Sticky Zeitgeist: Episode 2 Aperitif by Porpentine and Rook to draw out processes of art practice. I presented the beginning of the first part of this chapter at Beyond The Console: Gender and Narrative Games in London at the start of 2019. This is still very much a work in process, I’ve not even read this section back before posting it here. But I am very interested in the overlaps between Cixous’s figure of “woman”, “Becoming-Woman / Becoming-Girl” in Deleuze and Guattari, Bataille/Kristeva’s “Abjection” and “Johanna Hedva’s Sick Woman Theory” in regards art practice and trans* identity.

Part two: Excess

“Small salvage is $5.

Hear that sis, you’re $5.

Nooooo” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018).

Excess is a concept which arises in many areas of George Batailles work which spans art, literature, politics, economics, anthropology and mysticism. The concept, or rather an aspect of it, is particularly near the surface and therefore easy for us to grasp here, in Bataille’s essay “The Notion of Expenditure” (Bataille, 1985). Bataille begins by stating that while “there is nothing that permits on to define what is useful to man” (Bataille, 1985). Classical utility can be understood as follows;

“On the one hand, this material utility is limited to acquisition (in practice, to production) and to the conservation of goods; on the other, it is limited to reproduction and to the conservation of human life” (Bataille, 1985).

In contrast to utility Bataille positions “pleasure”, which he argues society judges to be lesser than utility in the eyes of society and is therefore permissible as a “concession” (Bataille, 1985). However Bataille proposes that just as a young man’s desire to waste and destroy demonstrates that there is a need for this kind of pleasure even while this cannot be given a “utilitarian justification”, “human society can have, just as he does, an interest in considerable losses, in catastrophes” (Bataille, 1985). Bataille sets this up as the tension between the ideological authority and the real needs for “nonproductive expenditure” which are at times not even articulable through the language of that authority. As examples of unproductive expenditure Bataille offers the following list;

“Luxury, mourning, war, cults, the construction of sumptuary monuments, games, spectacles, arts, perverse sexual activity (i.e., deflected from genital finality)” (Bataille, 1985).

A handful of these examples are examined further, but Bataille argues that in each “the accent is placed on a loss that must be as great as possible in order for the activity to take on its true meaning” (Bataille, 1985). Just as Lyotard identified affect as the point of excess which marks art apart from other things, and Cixous defines her figure of woman in terms of an unending outpouring, Bataille has identified “the principle of loss” (Bataille, 1985) as essential to a range of activities including but spreading beyond art and literature. The excess in Lyotard as deployed by O’Sullivan is that which is beyond the system of accounting for art, namely affect. In Cixous the excess is the capacity of the artist-figure woman when enacting ecriture feminine, to operate beyond the system prescribed by power to the production of art. As Allan Stoekl notes in his introduction to the edited volume “George Bataille Visions of Excess Selected Writings, 1927 - 1939”, for Bataille “People create in order to expand, and if they retain things they have produced, it is only to allow themselves to continue living, and thus destroying” (Stoekl, 1985). Bataille’s nonproductive expenditure is what is being freed in Cixous’s process of Ecriture Feminine, and I would therefore further argue, is being deployed in Aperitif, an artwork which deals with excesses both offered and implied (and therefore to be created at the point of interface with audience). More than this though, Bataillian excesses appear within the world of the game which the characters, and by extension us as players occupy. I would like to explore how different kinds of excess appear in Aperitif, and how these fit with Bataille’s observations around class struggle and manner in which those in power retain control of non-productive expenditure, including the expenditure of other beings. Finally I will consider these excess as areas which clarify Aperitif as abstracted horror and Ecriture Feminine.

A point where waste is rendered visible in Aperitif, in The Laugh of The Medusa, and in the work of Bataille, in the act of masturbatation. The character Ever, from whose perspective we begin Aperitif is the sole player character in the episode of the “No World Dreamers: Sticky Zeitgeist” which precedes it, “Hyperslime” (Heartscape & Rook, 2017) [KEYWORD Link to Smeared into the Environment]. Ever’s story in Hyperslime begins with a scene of anal drug use and masturbation which is interupted by the call to attend work. In the following episode, Aperitif, we learn that this work is in fact community service after Ever “whacked off in public” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). This detail of Ever’s life is exposed by Brava but in Ever’s interior monologue we learn that she herself does not fully understand why it occurred. Ever can only speculate on the reason for her doing something she identifies as harmful, and that the experience was like “watching through a window” after which she “blacked out” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). As an aspect of Ever’s character masturbation points to her isolation and desire, and to her struggle with the unbearable tension of shame which she alludes to when considering that “maybe I just wanted what they thought about me to come true” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). This enfolding of personal desire, the projection of being seen by another, the need to resolve an uncertainty, and the potential shame which runs through it is precisely how Cixous describes the struggle to produce Ecriture Feminine;

“[Y]ouv’e written a little, but in secret and it wasn’t good because you punished yourself for writing because it didn't go all the way; or because you wrote irresistibly, as when we would masturbate in secret, not to go further but to attenuate the tension a bit, just to take the edge off” (Cixous, 1976).

Ever, who the artists attribute the title/archetype/role “The Loser”, seems perpetually to be trying to manage the tension of her desires, with the only temporary resolution occurring in some kind of overwhelming loss of self. The struggle for a creative process which Cixous describes is not something I can identify in Aperitif because it is very much embedded in the experience of the process of making, which I do not have access to. However, I would argue that Aperitif is open to being played in a manner which is analogous if not in a similar affective register to the tension and collapse cycles of Ever. We begin both Aperitif and its prequel controlling Ever, but prior to the narrative beginning and still within the context of the title menu the game instructs us that we can “hold escape until you black out” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). On one hand this instruction is informing player-audience of the keypress which will allow them to exit the game. On the other hand, the use of the term “black out” echo’s Ever’s use of the same. When playing the game-artwork, I feel that the means of exiting has been embedded with an emotional resonance. Playing the game-artwork now has a resonance with Ever’s narrative, even outside of the points of play where I am controlling her character. The emotional content of the game is foregrounded, and the promise of the opportunity to in a manner, ‘lose consciousness’ as an escape from it invites/dares the audience-player to engage more with that content. We have permission to be a loser, to fail.

The concept of failure here is made complex when it is brought into the parameters of the game itself. It becomes an action. Ever berates herself for failure, but the artwork-game does not pass this judgement, and in aligning us with her and with failure, it invites us to not pass judgement either. Returning to Cixous, the other resonance of the allegory of masturbation to Ecriture Feminine is that the writer is given permission to write for themselves and for the act of writing to be self gratifying rather than requiring it before another. In “The “Onanism of Poetry”: walt whitman, rob halpern and the deconstruction of masturbation” the poet and lecturer Sam Ladkin notes the contradiction in the considered works “between masturbation as the failure of fecundity, spent energy without the returns of an investment” and something which has value in sowing “male seed across the typically female gendered earth” (Ladkin, 2015). In Ladkin’s work, the discourse around Onan, the poets being discussed, and the particular queer theory used tends toward the image and language of male homosexual desire but the author emphasises that beneith this the structure of “failed or suspended address” is not specific to a particualr “gendered identification fo desire” (Ladkin, 2015). In Cixous this contradiction between value and waste is articulated as fight to develop one’s own value system. To engage based upon the subjects desire, rather than exchange within an external economy which ascribes or denies a degree of value based on adherence to preexisting parameters. Ladkin explores the potential to “recuperate the wasteful excess of masturbation via the general economy of Bataille” yet in the author’s focus on the ejaculatory “economy of finitude” and the monetary economy of pornography, this avenue is effectively discounted and not further pursued (Ladkin, 2015). However I think there is a different dialectic at play in the systems of Bataille, and which are played out in the world of Aperitif as the struggle between the individual release of excess of the player characters, and the destructive forms of excess employed by power and authority, which render both landscape and those same player characters, as waste.

Bataille lays out his position that “Man is an effect of the surplus of energy: The extreme richness of his elevated activities must be principally defined as the dazzling liberation of an excess. The energy liberated in man flourishes and makes useless splendor endlessly visible” (Bataille, 2013). In Aperitif, this dazzling liberation of an excess is attempted by characters such as Brava, but it is always curtailed by the tyranny of an outer authority, the call to attend community service, the police. The motif of masturbation in Aperitif points to repeated denial of excess in the following of individual desire. As previously noted, character’s remain in a limbo of struggling survival, to “never perfectly live or die” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). In this state the following of individual desire into the expression of excess is denied to everyone except those who can afford it, as Brava recalls;

“When the internet 3 was invented the economy of really extra fucked, most stores were automated. Except the usual dollhouse experiments ran by rich people who fantasized about running a restaurant or cupcake shack of some shit” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018).

Bataille argues that “As the class that possesses the wealth -- having received with wealth the obligation of functional expenditure -- the modern bourgeoisie is characterized by the refusal in principle of that obligation” (Bataille, 1985). Bataille maps how earlier structures of social and material power would have led to the possessors of such power and wealth to express this through expenditure such as feasts, sacrifices and the construction of elaborate religious and cultural objects. In contrast to this, the logic of accumulation unders Capitalism leads to a “hatred of expenditure” (Bataille, 1985). In Aperitif this is demonstrated in the quote above from Brava showing that even with full automation, the bourgeois can only either imagine, or allow itself, a useless expenditure which takes the surface form of work by running a “cupcake shack” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018).

There is a second manner in which excess plays out through the agency of the authority in Aperitif and this is concerned with the rendering of subjects as objects, and then waste. Cultural theorist Sylvere Lotringer attempted to reexamine the concept of ‘Abjection’ in the work of Bataille, identifying a different trajectory from that subsequently developed by Kristeva in “Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection” (Kristeva, 1984). Lotringer’s short essay “Les Miserables” (Lotringer, 1999) positions Bataille’s fragmentary addresses of abjection written in the early 1930s as specifically in response to the “only truly original political formation to have emerged since the end of WWI [...] fascism” (Lotringer, 1999). Lotringer notes that in “The Notion of Expenditure” Batialle deplores the manner in which the bourgeoisie attenuate the damage done and “ameliorate the lot of the workers” (Bataille, 1985) as “abysmal hypocrisy” (Lotringer, 1999);

“The ultimate goal; of industrial masters, he asserted, wasn’t profit or accumulation, but the will to turn workers into pure refuse. Instead of extracting surplus value from the wretched population working in [the] factory, they enjoyed a surplus value of cruetly” (Lotringer, 1999).

The world of Aperitif presents a world in which authority has still not passed through its hypocrisy, but nevertheless continues to render the workers as waste. The company that employers Ever and the others to scavenge is represented by a character called “The Therapist”, which at least suggests a role of care, yet the job remains one of collecting scrap from a toxic environment which degrades and destroys their bodies (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). Lotringer’s published his essay Les Miserables in the edited book “More & Less” along with Bataille’s essay “Abjection and Miserable Forms” and interview with Kristeva titled “Fetishizing the Abject” (Bataille, 1999; Lotringer, 1999; Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Both Lotringer’s essay, and the line of questioning in the interview are in part concerned with a bifurcation within Bataille’s concept of abjection, which has not been given as much attention in its rearticulation and development by Kristeva in Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection and that works continued influence. Lotringer draws from Bataille a distinction between “The union of miserables reserved for subversion” and “wretched men rejected into negative abjection” (Lotringer, 1999).

The difference between the positive abjection which leads to action, solidarity, and perhaps martyrdom, and the negative abjection which leads simply to inertial, apathy, and alienation. The tension between these two forms of Abjection is something which appears throughout Aperitif, as its protagonists navigate a world of trash, see themselves to degrees become or be made trash, and navigate the threshold between agency and alienation.

In his summary, makes the following statement about Abjection without differentiating between the positive or negative form;

“Abjection doesn't result from a dialectical operation- feeling abject when “abjectified” in someone else’s eyes, or reclaiming abjection as an identity feature- but precisely when dialectics breaks down. When it ceases to be experienced as an act of exclusion to become an autonomous condition, it is then, and only then, that abjection sets in” (Lotringer, 1999).

It is unclear in this text whether Lotringer is arguing that what he elsewhere describes as people “becoming things to themselves” (Lotringer, 1999) defines Abjection in both positive and negative forms, or whether he is arguing for the primacy of the negative form. It is possible to read this as Lotringer trying to shift the definition of Abject to the negative, and the interview with Kristeva that will be addressed shortly in some ways supports this view.

Returning to Goard’s text on the trans* body and the cyborg it is worth nothing the importance of the process by which either are rendered Abject is addressed, though with different terminology;

“The dream of a world without surplus, illegitimate bodies is not feasible without a society that relies on surplus” (Goard, 2017).

Goard makes steps toward a politics whereby “bodies-made-surplus” (or trans* people and others) are not redefined, rearticulated and included, but simply allowed to exist (Goard, 2017). The politics not of “defining but defending” (Goard, 2017). Goard’s position seems to cut across Lotringer, proposing the act of oneself making and being made a thing as still containing revolutionary agency. In Lotringer’s reading of Bataille’s Abjection, at least in its negative form, is a place without hope of agency, a kind of living death. However Goard does seem to offer a position which is neither that living death, nor the simple dialectical struggle of being labeled abject and owning this label. Goard’s proposal becomes about a surplus yes, but an undefinable surplus which crosses categories of gender, class, race, ability, and attempts to tactically use such categories whilst aiming to ultimately destroy them. Goard articulates this party with the statement that “we should be deeply skeptical of placing value on the acquisition of formal rights when they are used in the legitimation of a violent border regime” (Goard, 2017). At the same time, Goard refuses the dialectic of power vs resistance by pointing out that the tactic entering into established modes of identity such as the gender binary are important at times for safety and so should not exclude a person from solidarity toward a common project of gender abolition for example.

[Footnote: The acquisition of rights for one group used as a means to justify is articulated by post-colonial theorist Jasbir Puar as “Homonationalism” in the 2007 book “Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer times” and developed further in the text “" I Would Rather Be a Cyborg Than a Goddess": Becoming-Intersectional in Assemblage Theory” (Puar, 2007, 2012). In the latter text Puar focuses on expanding upon the form’s negotiation between Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of “intersectionality”, “analyses that foreground the mutually co-constitutive forces of race, class, sex, gender, and nation” and an assembalge model which identifies “ the “retrospective ordering” of identities such as “gender, race, and sexual orientation” which “back-form their reality” (Puar, 2012). Puar sees these too positions not as “oppositional but rather,[...] frictional (Puar, 2012).]

As has been indicated throughout this chapter, Aperitif frequently plays establishing categories, names, structures, or identities, and having things which are surplus to these, which disrupt with either a counter-order, or the refusal of any order. Characters in some places self-define their identity on an axis of the gender binary, whereas the the game leaves other identity markers not only unknown but unacknowledged. The game frames and withholds information through its limited graphics showing animal ears, and text which trails off to convey emotion through lack of definition. An implication through explicit and implied information is that all characters in Aperitif are “girls”. However this category is broken open so wide as to be more in line with Cixous use of woman as catagory abstracted from sex, gender, or identity. “Girl” can be a category if it is deployed in that way, or it can something less stable.

Something about the four protagonists in Aperitif that remains consistent, and is presented unambiguously, is that the society they inhabit does not value their existence. Throughout the narrative, each protagonist struggles with whether or not they themselves value their own own existence. Society is ordered in a way that each of the four girls needs to undertake a job which is extremely damaging to their physical and mental health. A common thread throughout their conversations and many interior monologues is the consideration of whether than can, or should, survive this. In the interview with Lotringer titled “Fetishizing The Abject”, Kristeva describes her development of the concept through researching “borderline” clinical states in psychoanalysis;

“Without going as far as psychotic persecution, without going as far as autistic withdrawal, [the patent] creates a sort of territory between the two, which he often inhabits with a feeling of unworthiness, of even deterioration, a sort of physical abjection if you like” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999).

It would be out of the remit of this research to follow further into these pathologies. However; the oscillation of internal states, struggle, exploded categories, the question of self worth and being made thing invites another text to placed alongside Aperitif and Abjection. “Sick Woman Theory” by writer and artist Johanna Hedva (Hedva, 2016) is an examination of the politics which intersect in the bodies of disabled people, and offers a figure of protest in the form of the Sick Woman. As Hedva states, “Sick Woman Theory is an insistence that most modes of political protest are internalized, lived, embodied, suffering, and no doubt invisible” (Hedva, 2016). Applying Sick Woman Theory to hypothetical borderline case described by Kristeva repositions them as a political agent;

“The Sick Woman is all of the “dysfunctional,” “dangerous” and “in danger,” “badly behaved,” “crazy,” “incurable,” “traumatized,” “disordered,” “diseased,” “chronic,” “uninsurable,” “wretched,” “undesirable” and altogether “dysfunctional” bodies belonging to women, people of color, poor, ill, neuro-atypical, differently abled, queer, trans, and genderfluid people, who have been historically pathologized, hospitalized, institutionalized, brutalized, rendered “unmanageable,” and therefore made culturally illegitimate and politically invisible” (Hedva, 2016).

As the quotation marks around medical terms indicate, Hedva’s Sick Woman Theory is a kind of tactical categorization in order to refute a larger number of categories. Sick Woman Theory reads Abjection not from the position of analyst, but “the person with autism whom the world is trying to “cure”” as well as a multitude of other positions whose comonolity is that they are disenfranchised, suffering, and abused (Hedva, 2016). From the former position, categories become the norm, and things which transgress them a deviation or disruption. From the latter position of the multitude, the transgression across categories is the norm. It is possible to read the category of “girl” in Aperitif as Sick Woman, just as both, like Cixous’s woman’s writing, serve to encapsulate a sea of difference with an act of refusal against categories.

As mentioned previously in this chapter, a focus of Lotringer’s interview with Kristeva is questioning whether Abjection can form an oppositional function to power. Lotringer is particularly concerned with what he sees a broad tendency or movement within art and culture which attempts to reclaim the process of being made Abject and instil it with emancipatory potential. When asked at one point on this Kristeva responds “I feel very ambiguous in relation to this movement [...] I don’t adhere to it, and at the same time I realize that, as a kind of strategy, it is opposed to some kind of intolerable conservatism, so it's hard to adhere to that” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Kristeva’s concession is based in dialectic of Abjection against what must be imagined as a kind of totalitarian homogenous cultural sterility. Sick Woman Theory, is presented as “an identity and body” not against but in place of one of intolerable conservatism (Hedva, 2016). Hedva at point identifies this conservatism as the privileged existence, or “cruelly optimistic promise” (Hedva, 2016) of this existence, embodied by the;

“white, straight, healthy, neurotypical, upper and middle-class, cis- and able-bodied man who makes his home in a wealthy country, has never not had health insurance, and whose importance to society is everywhere recognized and made explicit by that society; whose importance and care dominates that society, at the expense of everyone else” (Hedva, 2016).

However, Kristeva seems to be describing an oppositional practice in line with what Lotringer describes as “reclaiming abjection as an identifying feature” (Lotringer, 1999). This Abjection is oppositional, it uses the definition given to it by what it opposes, and defines itself through that opposition. Sick Woman Theory instead repositions itself as the exclusion of what it can be seen to be opposing. Hedva argues that capitalism sets up binary between a default position of “wellness” and deviation from this in the form of “sickness”. To simply embody this deviant category of “sick” would be exactly the oppositional process of Abjection described by Lotringer and Kristeva. However, Hedva also argues that under capitalism “wellness” is positioned as a temporal norm, whilst “sickness” and therefore “care” is positioned as temporary. Hedva’s position can be seen as arguing that a broad encapsulation of vulnerabilities, oppressions, and suffering should be considered the norm. Crucially, care for oneself and for others, could and should follow as another norm. It can then be proposed that Sick Woman Theory, is not a struggle with another, but a reconfiguration of the context underneath both which shifts perspective. This reconfiguration is analogous to an operation I have elsewhere discussed as occurring within horror narratives, using the example of the film “Ringu” (Nakata, 2000). [LINK TO “FROLIC IN BRINE” performance SCREENPLAY]

Hedva’s call for the centering of their broad category of sickness, which includes not just sufferers of illness, but also victims of the violent enforcement of acceptable categories of gender, sexuality, class, etc. does find a direct parallel in Kristeva’s thought;

“These states, far from being simply pathological or exceptional, are perhaps endemic. And it is perhaps against this sort of structural uncertainty that inhabits us that religions are set in motion, at once to recognise them and to defend ourselves against them” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999).

I am wary of pursuing an argument regarding the subjectivities included within Hedva’s Sick Woman predating, and perhaps causing the social structures which their existence transgresses. Such an enquiry would move beyond the scope of this project, which is concerned with the practice of art.

In Fetishizing The Abject much of Lotringer’s direction of the interview focuses on ways in which further discourses, including art, have misincorporated Abjection following Kristeva’s popularisation of the term. While a number of art tendencies and specific exhibitions are critiqued, it is the speculation on what Abjection could do in art that is most relevant here. Both Lotringer and Kristeva agree that when something is placed in a gallery, it “becomes a new identity” and thus “fetishised” it joins other “[i]institutional objects” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Regarding potential to move beyond this, Kristeva proposes that “verbal art, insofar as it eludes fetishization, and constantly raises doubt and questioning [...] lends itself better perhaps to exploring those states that I call states of abjection” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). I am skeptical about the claim that any art form including verbal art might elude fetishization, but the operation of constantly raising doubt and questioning resonates with other observations in this chapter, as well as this PhD project overall. Elsewhere I discussed a concept from my research which I call Incomplete Provocations [LINK TO TEXTS]. Also, the use of unreliable narrators occurs in the majority of what might be called the fiction elements of this project. Something which is important to note regarding at least my use of unreliable narrators is that there is a rarely deliberate deception on the part of the narrator. Deception would necessitate that the narrator knows more than the audience who learns only from that the narrator reveals, at least initially. The application I am more interested in, is the unreliable narrator as point of which by either being cognitively compromised or simply different, has another perspective on events. The ideological position implied through this is that there is no one narrative which could encapsulate the entire event and therefore resolve it. There is always doubt and questions, each of which solicit speculation from the audience. In Deleuze and Guattari’s “A Thousand Plateaus” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987) the line that illustrates this non-deceptive unreliable narrator occurs at the start of the chapter “1730: Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal, Becoming-Imperceptible…”. While beginning an account of a film, the authors offer the disclaimer, “My memory of it is not necessarily accurate” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). The author’s uncertainty in their memory would fall within my description of the cognitively compromised unreliable narrator, and before even getting to the recounted film, doubts and questions are ready to be raised. These doubts and questions do not all have to be positioned in the gap between recollection and what was witnessed, though in this case we could look for differences between Deleuze and Guattari’s account, and the film itself. The other doubts and questions that I am interested in project not backwards in time to the witnessing but forwards. What is interesting to me is not what is lacking from the film in the recounting, but how the recounting is a process of addition which grows from the film even while it might leave out parts of that source material. In this way, the unreliable narrator offers a provocation not for a return to the stillness of certainty, but for the movement of more emerging possibilities.

Kristeva proposes something similar in her proposal for future Abject art, which involves processes of “anamnesis on the one hand, and gaming on the other” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). In terms of amnesia Kristeva expands this as “a sort of eternal return, repetition, perlaboration, elaboration” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Within Aperitif the process of amnesia enacted as the player returns to walking a path through the same environment with different characters, as well as through the game form which allows itself to be replayed.

[FOOTNOTE: For a radically different analysis of a comparable creative terrain to Kristeva’s Anamnesis see Mark Fisher’s “Ghosts of my life: writings on depression, hauntology and lost futures”. “This dyschronia, this temporal disjuncture, ought to feel uncanny, yet the predominance of what Reynolds calls ‘retro-mania’ means that it has lost any unheimlich charge: anachronism is now taken for granted” (Fisher, 2014).]

Kristeva follows Anamnesis with Gaming which involves “compositions, decompositions, recompositions” and is presented as a continuation of the “trajectory” as Anamnesis (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Examples provided for this process involve the process of chance through rolling dice, and the “glossolalia in Artaud, or like Finegan’s Wake” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). This resonates with Aperitif on multiple levels. At the game level Aperitif, despite being fairly linear in form, composes, decomposes,and recomposes itself continually. From the position of the player audience, this is perhaps most clear as the game shifts its genre and method of play at points. At points the player controls characters which walk around an environment and interact with one another in the manner of a role playing game. At other points the game switches to the form of a medical simulator where the player but diagnose and repair a robotic character with a completely different mode of interaction from the role playing game sections. This medical simulation then decomposes further as the performing of a specific repair sakes the form of side scrolling “shoot ‘em up” as a game within a game within a game. What would however be more in keeping with what Kristeva is describing would be evidence that at some level the making of this artwork included a shift to a less consciously direct mode. The reference to dice alongside glossolalia leads me to conclude that Kristeva’s Gaming is about the movement between conscious decision making, and something else which destabilized it, before potentially returning to conscious decision making. This destabilisation could be through the cold probability of a dice roll, the path for the works creation decided by the resulting number. The inclusion of Finegan’s Wake and Artaud’s glossolalia suggests that the destabilisation does not have to be the surrender to chance. Destabilisation could include the shift to using or creating words based on their sound rather than meaning for example. Cultural theorist Michel De Certeau described glossolalia as “vocal vegetation” not an exceptional thing constrained to the devout and artists, but the “bodily noises, quotations of delinquent sounds, and fragments of others' voices [which] punctuate the order of sentences with breaks and surprise” (De Certeau, 1996). The language in Aperitif, particularly where it comes to building its world through this language feels full of moments of shifts to a destabilised mode. Swamp-Dot-Com is populated with things like “bombo cabbage bludbud”, “lichen mommy board” and “whackback” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018).

[FOOTNOTE: A methodological decision has been made not to include research drawn from Heartscape and Rook’s other work, in order to focus on how this can inform methods of art practice, rather than drawing out the tendencies of these specific artists. However, it is worth noting that the processes of Kristeva’s Gaming are evident throughout Heartscape’s individual art practice. Heartscape curated the 2018 exhibition at Apexart in New York, entitled “Dire Jank” (Apexart, 2019). Dire Jank included artist Tabitha Nikolai’s video game “Ineffable Glossolalia” (Nikolai, 2018) and “Divination Jam” which invited the audience to “use divination, randomization, etc to make your game. when you get stuck, instead of feeling like shit, let some arcane system decide for you! rolling a die, i ching, tarot, anything that invokes fate! many ancient systems have been digitized, or you can look for randomness in the world around you…” (Heartscape, 2018). Furthermore, Heartscape’s 2016 novel “Psycho Nymph Exile” both contains the same collapsing worldbuilding language as Aperitif, and features such processes within its plot. “The crystal gives them an allergic reaction to language. Each girl has a unique combination of trigger words. They sit on the floor in rows, mumbling under their breath, reading from dictionaries until they find their combination” (Heartscape, 2016).]

This play in language is subtle, but I believe it a shift away from the direct conveyance of meaning to sounds and the joy of what words written down can do.

An area the gap between Kristeva and Lotringer’s Abject Art, Hedva’s Sick Woman Theory, and Aperitif widens is with the issue of the abject and identity. Lotringer sees Abjection’s relation to Fascism which he stresses is its origin in Batialle’s text “displaced” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). He broadens this further with the claim that “politics has become the politics of the notion of identity” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). This broad position is agreed by Kristeva who replies “everything has been taken up by the “politically correct” which are in fact identity related claims” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). It is this identity that Kristeva and Lotringer see in what they consider the problematic Oppositional Practice already outlined. I would like to argue though that their perceived problem with Abject identity would not apply to the way identity figures in Sick Woman Theory. Hedva sets out their position with clarity;

“The sick woman is an identity and body that can belong to anyone denied the privileged existence, or the cruelly optimistic promise of such an existence- of the white, straight, healthy, neurotypical, upper and middle class, cis and able-bodied man” (Hedva, 2016).

Sick Woman Theory is not a politics of sexual identity, but a broad identity which encapsulates sexual identity along with bodily, cognitive, and class differences. This is not the sidestepping of class struggle and opposition to fascism Lotringer in particular is concerned with in his observations about previous attempts at an Abject turn in art. Hedva creates an amorphous, fluid grouping, brings to the centre difference and care under the banner of the Sick Woman. Returning to The Laugh of The Medusa, Hedva’s project has strong resonances with Cixous’s;

“If there is a “property of woman,” it is paradoxically her capacity to depreciate unselfishly: body without end, without appendage, without principal “parts.” If she is a whole, it’s a whole composed of parts that are wholes, not simple partial objects but a moving, limitlessly changing ensemble, a cosmos tirelessly traversed by Eros, an immense astral space not organised around any one sun thats any more of a star than the others” (Cixous, 1976).

Cixous frames this “property of woman” within a text which is concerned with the practice of making art, but this practice is part of process which includes woman putting herself “into the world and into history” (Cixous, 1976). Writing, is embedded in a politics of living. For Cixous’s woman to write only in the dominant mode of man’s writing, is to be restricted not only from writing herself (as Cixous would put it) but to enter into the world as a subject, as an agent. If we read Cixous’s woman not in terms of an essentialist category which might be attached to some biological marker, but as a class category, she readily aligns with Hedva’s Sick Woman. Cixoux’s contemporaries Deleuze and Guattari describe the process of “becoming-woman” which can be considered like the former’s woman but now not a class but a process (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). MacCormack gives a succinct explanation of Becoming-Woman, “Woman as minoritarian is defined by lack and failure so an element of woman - gesture, fluid libidinality - taken in or as part of the self will necessarily alter the self” (MacCormack, 2008). In Hedva’s text, the woman is named for the “subject position [that] represents the uncared for, the secondary, [...] the non-, the un-, the less-than” (Hedva, 2016).

Even when addressing cisgendered women, the call Cixous is making entails Becoming, which MacCormack describes as selecting “certain specificities and intensities of a thing and [dissipating] those intensities within our own molecularities to redistribute our selves” (MacCormack, 2008). Cixous calls us to redistribute into ourselves the intensity of fluid libinality which she calls the “unflagging, intoxicating, unappeasable search for love” (Cixous, 1976). This pull of desire and connectivity reads like an antithesis of Valerie Solanas’s description of “the male” as an “unresponsive lump, incapable of giving or receiving pleasure or happiness” (Solanas, 1971).

[FOOTNOTE: For a trans* reading of gender in Solanas as creative process see writer Andrea Long Chu’s proposal that “Here, transition, like revolution, was recast in aesthetic terms, as if transsexual women decided to transition, not to “confirm” some kind of innate gender identity, but because being a man is stupid and boring.” (Long Chu, 2018).]

The Woman in Sick Woman Theory is similarly a source of creative desire, which Hedva explains through a description of some of their own symptoms;

“Because of these “disorders,” I have access to incredibly vivid emotions, flights of thought, and dreamscapes, to the feeling that my mind has been obliterated into stars, to the sensation that I have become nothingness, as well as to intense ecstasies, raptures, sorrows, and nightmarish hallucinations” (Hedva, 2016).

These descriptions form part of Hedva’s consideration of political agency of those, who for bodily, social, or other reasons cannot engage in the direct politics of public action. However the language, as with Solanas’s, is as concerned with emotion, affect, aesthetics, and creativity. Solanas’s Male is “incapable of empathizing” (Solanas, 1971) while “Sick Woman Theory asks you to stretch your empathy” (Hedva, 2016). Solanas’s manifesto is explicitly a response to the boredom society provocokes as it is dominated by the “psychically passive” figure of the Male (Solanas, 1971). Without exoticising and objectictifying illness, mental or otherwise, the subject of Sick Woman Theory is undoubtedly a creative force.

I hope that I have demonstrated that the world, characters, and player-audience experience of Aperitif have a resonance with theories of Abjection, and creative difference connected to a broad category of Woman. Aperitif is on one level, a video game about a group of runaway broken robots, and hybrid animal kids trying to improvise through wasteland failures, emergent tactics of living through giving and receiving care.

Throughout Aperitif, many things are left undefined, or only implied. Dialogues are full of the pointed absence of speech in ellipses. Delivery of information gives way to Gaming. Character’s themselves are unsure of what has happened, cannot remember, are too traumatised, or simply offer a conflicting view of events to one another. Finally the game itself, with its limited interface and graphics which hark back to games long before the turn of the millenium, makes clear that details are being withheld. With this in mind, the group of protagonists being self identified as, or implied to be “girls” rather than Women, can be understood through another Becoming proposed by Deleuze and Guattari, and explored further by MacCormack. Within the context of Becoming-Woman Deleuze and Guattari ask “What is a girl? What is a group of girls?” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). They consider Marcel Proust’s protagonist’s search for “fugitive beings” (Proust, 2010) and conclude that the Girl whether singular or in a pack, is “pure haecceity” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987).

[Mark Fisher defines Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of Haecceity as “non-subjective individuation. [...] the entity as event (and the event as entity)” (Fisher, 2018).]