Text

"Why do you have so many names?"

"Comment?"

"Names. Joseph, Paul—names."

"Oui, oui. Alors. So many before me, they make dead in battle. And so ma mère, she want me have protection of heaven. And so, Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier."

"What do I call you then?"

"Gilbert."

THÉODORE PELLERIN as GILBERT DU MOTIER, THE MARQUIS DE LAFAYETTE

1x01, FRANKLIN (2024)

157 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sunset Boulevard (1950) dir. Billy Wilder

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Leslie Howard as Henry Higgins in Pygmalion (1938)

#leslie howard#henry higgins#such lovely gifs#i love the dutch angle used for the lessons#higgins tripping as he passes the enlightened buddha#and wendy hiller's restraint - her convulsive hand and rippling back magnifying the strength of her effort#pygmalion 1938

264 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stella Bowen (1893 - 1947) - Embankment Gardens c.1938. Oil on board.

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

[excerpt from 'Wittgenstein' by William Child]

#ludwig wittgenstein#wittgenstein#bertrand russell#wittgenstein stories rank amongst my favorite things

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

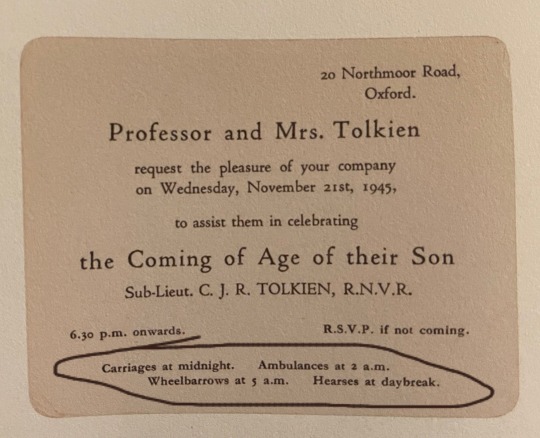

"our son made it through the war to come of age, let's fucken party! rsvp only if you're a little bitch who's NOT coming. all y'all not dead of alcohol poisoning by morning (lmao losers) get dunkt on"

63K notes

·

View notes

Text

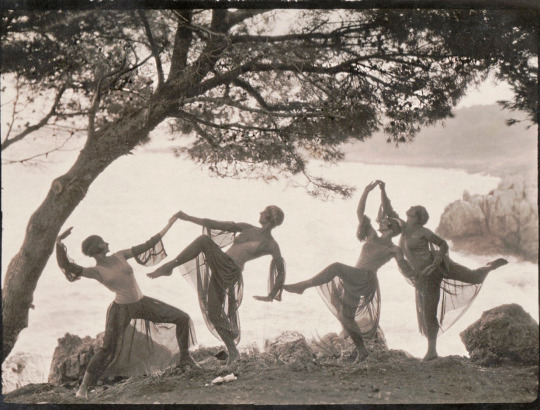

Fred Daniels :: Loïs Hutton and Margaret Morris in poses at the Château-des-Enfants, 1920s. From Rhythm & Colour. Hélène Vanel, Loïs Hutton & Margaret Morris. Richard Emerson. Published by Golden Hare, Edinburgh, 2018. | src TankMagazine

View more on WordPress

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

This made my day — thank you for writing this out and sharing. In your debt! You've sparked fresh memories for me too.

- I'd completely forgotten that Higgins ended up fond of the concertina by the end — going from cursing and chasing Eliza around to stop her playing to patting the instrument and smiling when he runs into it at his mother's house, or something like that.

- I also thought BERLIN upon seeing that lakeside villa. And the cocktails, though that's also a way to situate events in the thirties I suppose — one could have briefly been in a Noël Coward play. I had to wonder if they added the cocktails to make it clearer that Higgins was headlong and losing control, since Gründgens iirc interprets Higgins as rather stiff and doesn't particularly follow the scene directions to throw himself at furniture and nearly break a table and stumble over things (in contrast to Dutch!Higgins, who gets across that restlessness if not the emotional reserve). Now that you mention it, I seem to remember Clara's role at the tea/cocktail at home a little better; in a slight departure from the play, she's not so much drawn to Higgins as disappointed that he doesn't match the mental picture that had been conjured for her. Is that right? She'd imagined him differently, or some such. Did they keep the bit from the play where he tempts her into swearing? I adore the 38 film, but one of my regrets is that it cuts most of Clara's scenes and consequently a vivid illustration of Higgins' disregard for consequences and ability to get up to mischief when left unsupervised.

- I'm cracking up over the post-fight rant to Pickering. Schopenhauer! How could I forget? Of course. LOLOL.

- I agree with your read on Johnny - he seemed more like a Kumpel in her treatment of him than a love interest, if also a sign that she could hold her own and get help against the toffs if needed. He also served to define this Eliza against the one of the play, who seems to have few if any friends, lives alone, and finally claims she could never code switch (does Jugo still have that line about never being able to utter one of those sounds again? I can't remember). I also felt he served to show just how cold Higgins must seem to Eliza — in contrast to Johnny's friendliness, Gründgens radiates a certain amiable but nonetheless icy remove.

- Thank you, thank you, for this breakdown of the final act! So she does pose three options after all. I remember the ring sequence now - she seats herself before a mirror and puts it on, is she talking to herself during that scene too? The structure of the challenge — if she reveals her origins she stands to lose newfound security, if she hides them she's complicit, she melds in with the conforming masses — could have been subtly provocative in the context of when this was made, and I have to wonder how that got in (wouldn't be surprised if it's from Engel, who'd been initially fired by the UFA studio, I think in the 33 purge, for his communist sympathies; I've read in passing that he made several films on the theme of individuals choosing an unconventional path which skirted censorship, but haven't seen those films for myself). I like too that the ending is somewhat ambivalent — in asking her to come back, he's not specifying what that would mean (unlike Dutch!Higgins who overtly suggests marriage, which I personally found very jarring). At the same time, in respecting her preferred form of address (which play!Higgins could never bring himself to do), he's indicating a new basis for the relationship, one where she calls (more of) the shots. I can't help but feel like there's something dialectical going on with the three-four options thing - Engel worked closely with Brecht, who loved to employ Marxian dialectics as a practice of change-making - where the final synthesis at once negates and upholds. But that's a poorly thought-out aside. Wait wait - I can't remember what verb he got wrong, which was it? Was it that he used slang?

You're the best!

got my hands on German Pygmalion from 1935🦫

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gustaf Gründgens, Erika Mann, Pamela Wedekind, and Klaus Mann, 1925.

At the time of this photo, Erika was engaged to Gustaf but was having an affair with Pamela, who was engaged to marry Klaus, who was romantically involved with Gustaf.

335 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm so glad to find someone else who's seen it! I've only seen it once — the DVD won't play in my region code — but remember finding it fascinating, both structurally and as a historical document (with much, some extremely disturbing, left to unpack given who made it and when). Shaw hated it, iirc.

Some memories that may be misremembered details - would love love your take on what is actually in the film:

Eliza speaks a fantasy argot of Berlin and Vienna dialects (Jenny Jugo, the actress, was Austrian), which has a slightly alienating effect, as though to suggest that this story cannot fully translate, ie. could never have taken place anywhere but England. Or maybe it's a Brechtian touch from the film's director, Erich Engel. (There's also a really weird choice regarding Sie/du usage between Higgins and Eliza that I don't remember well enough to mention in more than passing but that did seem like a cultural translation error.)

In the play, Eliza sends for a musical instrument, but it's never specified in the text what Alfred ends up bringing to Wimpole Street. In this film, I seem to remember it being a concertina (a bellows-driven free-reed instrument with buttons at the ends). Smaller than an accordion and thus easily portable, developed independently in England and Germany, the German concertina has an association with dance music and the working classes. (Both the Dutch and English films also give her a concertina, iirc — the instrument plays a huge role in the Dutch film, and you can spot it in her rooms in the English one.) In any case, she plays and sings a raucous song written for the film, "Ich bin lustig ob ich Geld hab' oder keins", "I'm jolly whether I've got money or none". The song potentially says as much about Germany in 1935 as about this specific iteration of the character — it has fatalist, devil-may-care lines like, "ich bin lustig ob die Welt zum Teufel geht" (I'm jolly if the world goes to the devil), etc.

Higgins twice invokes Schubert's "Ständchen" (Serenade), once on the piano and once, whistling, after returning home from the ball. It's a wistful love song — softly imploring the beloved to listen, to come out, to not fear being overheard — that would have been instantly recognizable to a bourgeois audience raised on Romantic Kunstlieder. This marks a change from the 1912 play, where the crew is implied to have gone to see the new Puccini opera set in the wild west; Higgins whistles an air from that opera after coming home (ironically, since it's a piece about a woman cheating to win a bet and save the man she loves). Perhaps there's irony in having German!Higgins reference a song about being overheard, not least because he never sings the lyrics, only plays/whistles the melody — thus going over Eliza's head.

Much is made of the fact that Eliza took a boy with her on her initial taxi ride to Wimpole Street. Alfred implies a fairly young boy in the play; here he turns out to be a blond, strapping fellow named Johnny. While Eliza goes in to ask for lessons, Johnny waits outside for an all clear signal, like a kind of bodyguard, adding an element of mistrust to her character as well as independence (she has the means to threaten). Overall, Jugo's Eliza seemed to me a good deal less vulnerable than the Liza of the play (where there are hints that other flower girls bully her, where she specifically wants a taxi ride in her new clothes to get her own back). Johnny reappears in a couple of other scenes, including as an ice cream vendor at the first outing taken before Mrs Higgins' at home, the horse races, but I forgot what he says or does, exactly; part of his purpose iirc is to show that Eliza can seamlessly code switch. In terms of the scene, was it that someone tried to walk off with ice cream without paying for it? I seem to recall Eliza demonstrating she can hold her own — springing both physically and verbally into the fray — only to begin speaking high German again once the disgruntled toffs (Higgins) appear.

Alfred ends up lecturing for a temperance society, I believe. Altogether they make something more Brechtian of him, at least in my memory — and wasn't there an extra scene including Eliza's sixth stepmother?

Another added scene is right before the ball — it shifts the balance of power (Higgins is never particularly in control in this film, however, iirc). Higgins is in a state, he comes out from his room upstairs in his dressing gown with his face almost totally masked in shaving cream and bumbles down a long set of stairs to interact with Pickering. I forgot why — maybe helping Pickering look for the ball invitation, which both have misplaced. Eliza then joins them, but not before looking down on them from above. There follows a scene where she immediately solves their problem, then asks for advice on what to wear — maybe which earrings? — and offers three options. Is that right? Or is it two? Higgins is iirc useless at fashion but does inadvertently reveal that he finds her smile charming. The posing of three options — or maybe it's two, and Higgins gives a third — is also used at the very end of the film.

After the post-ball fight, Higgins doesn't storm off to bed; instead, as you mention, he wanders into Pickering's room for reassurance. There I seem to remember he sits at the window, staring at the moon (another German Romantic association, like the Schubert), and wonders whether Eliza's rage is anything he can trust: whether it's something she copied from a book or whether her soul has really been transformed through the experiment. Pickering is astonished. I wish I had access to a screenplay or screencaps for this sequence to recall what he says exactly in the German. I remember thinking Gründgens sold this scene — in part because there's tension and intimacy with Pickering, in part because he's so incapable of expressing himself except in literary abstraction.

The final act includes several major changes. Mrs Higgins' artistic Chelsea drawing room has become a lakeside villa, Freddy is there playing lawn games and the mandolin? (I have a weird memory of a ukulele?) and setting up a boat, Higgins shows up and immediately has a cocktail I think? Maybe? Once alone with Eliza, and faced with the prospect that she'll marry Freddy, he leaves off some of the insults and challenges her — does she really think these people will accept her once they learn the truth of her origins? Eliza is initially dismissive, maybe? but ultimately decides to tell the truth over lunch with the Eynsford-Hills, causing a minor sensation and prompting the whole family to up and depart. Freddy bounds back and shouts to Eliza from outdoors that he doesn't care and wants to marry her anyway. Higgins congratulates her on her splendid honesty (as though to finally acknowledge that she's won the bet, though of course he's egged her on to do this with a kind of bet of his own). Eliza once more poses two/three questions; she asks him whether she ought to marry Fred or do something else, and he asks her to do neither and come back, and the film ends.

Very curious how much of this is made up on my end, and to hear more of your thoughts!

got my hands on German Pygmalion from 1935🦫

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pygmalion, 1938

#i love that even though they toned down the victorianism of mrs higgins' rooms for the 38 film#the key artistic elements remain - flowers#landscape paintings#cheyne walk - the embankment#in contrast to the abstractly spiritual - stern buddhas indicating an alien enlightenment - and vaguely menacing machineworld#that higgins inhabits#it's fun to imagine child!higgins surrounded by pre-raphelites and aesthetes and other victorians#and reading the differences as rebellion#and then taking the miltonian aspect - rebellion and exiting the garden#the final scene takes place in a sort of garden#just as the first begins in a kind of garden#only the first was outdoors and wet and marked by stark class differences while this is a contained indoor space#rambling way of saying I like this set lol#pygmalion 1938#leslie howard#wendy hiller#films#gifs

663 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HILLARY BROOKE & RAY MILLAND in

MINISTRY OF FEAR ― 1944, dir. Fritz Lang

492 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Memory heaps dead leaves on corpse-like deeds, from under which they do but vaguely offend the sense.”

— John Galsworthy, The Forsyte Saga

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wendy Hiller as Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion (1938) Dir. Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard.

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A work of art does not answer questions it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers."

—Leonard Bernstein

46 notes

·

View notes