Text

On Kata and the Proper, Sometimes Inefficient Ways to Manifest Agency and Meaning

Probably the most important lesson that can be gleaned from Zen (and Japanese culture) is the one that is most ignored by the scores of otherwise topically adoring fans, namely, kata or form.

The principle of kata essentially establishes that there is a way for most everything to be done. The proper form of any given activity is often not the quickest, easiest, or even most logically sensible, but it is constant.

In the emerging global culture pioneered by the west so-called “free time” is most prized. Therefore efficiency and ease are the traits that lead our approaches to almost everything, and yesterday’s modes are always at risk of being deemed obsolete in favor of a new, more effortless models of doing and being.

Of course, we’re often so busied in our pursuit of free time that we don’t know what to do with it when we have it, and quite literally find ourselves in existential quandaries, marked with depression and anxiety, when we can’t find meaningful activity to fill our “free time” with.

When our mode of being is so consistently concerned with not having to invest ourselves fully in the mundane activities of our daily lives, lest they serve as costly distractions from the to-be-determined yet preferable, and seemingly intrinsically meaningful pursuits we might otherwise fill our time with, how else could things be?

Kata teaches us to show up to our lives. To sort through the confusion of endlessly preferential thoughts, and to navigate life via the essentially nonnegotiable demands of the present moment. This requires surrender which eventually is transmuted into discipline and agency, of which sort the ability to manifest meaning ultimately belongs to.

~Sunyananda

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bukkyo, Budo, and Shugyo

True spirituality (bukkyo), like true martial arts (budo), brings us face to face with the realities of life, and chiefly, with its limitations. In intentionally confronting mortality, suffering, violence, pain, and unknowing we can realize the confidence to actually enter into the streams of our lives already in progress, unburdened with the weight of fearing the unknown (consciously or otherwise) which keeps us so readily anchored to a half-life of ignorance, reservation, and even reckless attempts to break free from our molds.

As these fundamental matters are broached, and the ambiguity of their relationship to our being is resolved, through ongoing training in the midst of our daily life (shugyo) we can come to authentically entertain the nuances of love, joy, peace, awareness, and freedom. We can come to celebrate the would be ravages of time as the play of temporality, and to dance with its steps.

At its heart, such training is always about honesty, agency, and intentionality. Through it we can find meaning, narrative, and poetry that can withstand the gravity of reality, and persist as wisdom embodied.

~Sunyananda

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Shugyo

Shugyo*, above all else, is about fidelity. It’s about returning, time and time again to the nest of practice. Returning in times of gain, in times of seeming stagnation, and in times of decline. Shugyo is about will, and unknowing. It’s about intimacy, and humility. It’s about limits and infinity. Shugyo is life itself.

~Sunyananda

[*: Ch. 修行 (Cultivation, Practice), Skt. Sadhana (Spiritual Practice or Discipline)]

#shugyo#budo#martial arts#aiki#aikido#karate#hapkido#practice#spirituality#spiritual#cultivation#sadhana

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Kata, Pedagogy, Artists, and Technicians

The utility of traditional kata is entirely wrapped up in the reality that the forms have no definite meaning. Like sacred writ, each generation of practitioners must renegotiate how the strings of movement are engaged.

The most refined systems of practice contain within their curriculums exemplary waza (techniques) that inform and apprise the practitioner as to the fundamental essence of the system, and from these a practitioner can approach even a small body of kata, study them, and find inspiration for life. In this way, a system need not formalize cumbersome listings of techniques into the thousands. Instead, utilizing a deductive and inferential pedagogy born of the meeting of exemplary codified waza, appropriate kata, and necessary ambiguity.

When a practitioner is taught a technique for every seeming possibility, they become martial technicians at best. When they are forced to analyze, interpret, and derive, eventually their eyes may be opened in such a way that they can in fact create, even spontaneously, and finally be appropriately called martial artists.

~Sunyananda

0 notes

Text

On Context, Presuppositions, and Keeping Legitimate Skill Real

Traditional martial arts tend to get too wrapped up in their own mythos.

It’s not that all training needs to be “live;” indeed, there are a number of skills that when employed against resistance in anything but the most skilled and sensitive of hands can result in debilitating injury.

What it is, though, is that we all need to continually examine our presuppositions, and the context(s) upholding them. Without this, legitimate skill tends to drift into the realm of the fantastical, and real training tends to devolve into excercises in belief and dogmatism.

As we train, it’s not uncommon for motion and legitimate skill to become more and more subtle, and more and more efficient. And, if we’re not careful curators of context, the same body of skill has a tendency to become more and more esoteric wherein not only the technique but its presumed effects can be know (or conjured up) only by initiates. This is a truly sad, and extreme state of affairs, that is unfortunately too common.

For a martial art to be a martial art, it must be rooted in reality. That is, it must be applicable to real expressions of violence in context. Granted, this potential applicability exists in a vast expanse of socio-cultural paradigms cleaving through time. Nonetheless, a martial art must not be confused with a dance routine, nor any other more generic form of physical culture.

For a martial art to remain a martial art, it must remain conversant with its context, and in critical dialogue with its presuppositions. The shadow side of such vigilance though, is the devolution of legitimate skill due to a perceived lack of applicability to another specific context (presently, “the octagon” is a chief culprit).

All in all, the sage advice of the German philologist Max Mueller applies to the religionists he addressed as it does to martial artists seeking reality and relevance: when it comes to [contexts], knowing but one you know none!

~Sunyananda

0 notes

Text

On the Spirituality of Martial Arts

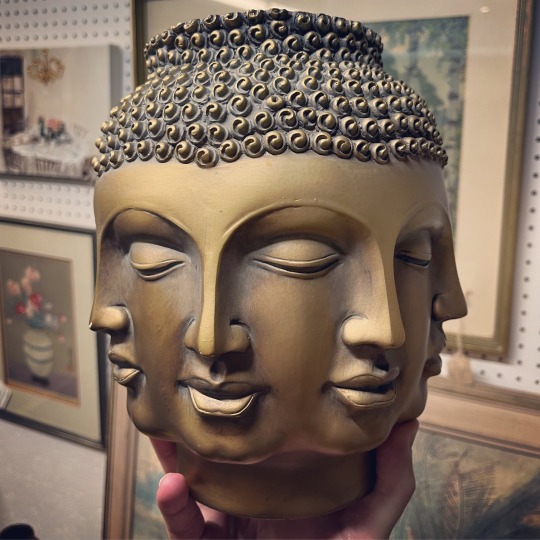

The spirituality of martial arts (Budo) is not an obvious thing. No amount of outfits, other accoutrement, or religiously adjacent cultural customs can elucidate (let alone comprise) the actual heart of training.

Contemporary definitions define spirituality as that which concerns “the nonphysical part of a person which is the seat of emotions and character,” with etymology uncovering the nature of spirit as “breath,” that essential yet often overlooked exchange of life giving gasses between our environment and innermost being.

In East Asia, the etymology of the word spirit (神) pertains to lightening, and the seemingly spontaneous manifestation of raw, overwhelming power in nature. The ancients saw lightening as coming strictly from the sky. Contemporarily we understand the visible force of lightening to come from the ground up. In reality, it’s both.

Budo is simultaneously an outwardly recognizable physical discipline and more subtly internal set of commitments and challenges. It is something learned from the outside in, but truly manifest only from the inside out. This meeting place between interior and exterior, between mental and physical is where the spirituality of martial arts abides.

Beginning with the common grappling between bodily compliance with the obscure physical demands of the arts (and the competition for attention and motivation with myriad other forces vying for our time) the spiritual path of Budo has its genesis as mere discipline, and its truest revelation in the spontaneous inseparability between technique and the dispositions, commitments, and activities of everyday life.

Budo is a pursuit that comes to occupy and possess one’s mind as much as one’s mind, when peeled back to its essence, comes to occupy and define Budo. In this, Budo is not simply a practice of combat or military tactics, but rather an orientation toward life that elicits awareness, acceptance, and harmonious accord with reality as it is. For this reason, aphorisms such as “Ken Zen Ichi Nyo” (拳禪一如) have come into being - “the fist and Zen are one.”

Conflict and peace are in constant relationship, seemingly a dichotomy until their dynamic tension is realized as a fundamental unitary nature. Life and death, and indeed all supposed opposites are also like this. Budo is a ground of intentionality where this fundamental unitary nature can be perceived and proactively engaged, with conscious attention and agency. What could be more spiritual, lest we confuse the constructs of belief and creed with true matters of spirit?

(Pictures from 15+ years ago, 10+ years ago, and 1+ year ago)

~Sunyananda

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Aiki, Static Wrist Grabs, and the Realities of True Basics vs Second Level Skills:

Aiki/Hapki arts have a lot of problems, and are often rightfully critiqued for their lack of realism. Chief among the problems facing these arts is their emphasis on the static wrist grab as a foray into learning basic techniques. Static wrist grabs lack intention and therefore give rise to resistance in every direction, which is either forcefully overcome or selectively muted by means of subtle hypnotic suggestion. Neither of these options provide the meaningful opportunity to learn how to harmonize with intent, and the transmission of fundamental skills therefore becomes murky when not (frequently even) entirely lost.

The reality is that wrist grabs are an opportunity to practice advanced skills on behalf of both uke and tori, and are actually poor starting places for beginners. A proper wrist seizure is a subtly dynamic encounter rather than a static or still moment to explore rudimentary motion. One must already have a working knowledge of the basic mechanics of the encounter that would give rise to a wrist seizure to provide a meaningful opportunity for practice.

If we understand Aiki arts to be rooted in sword work, the wrist seizure automatically becomes understandable only as a second level attack based on combative distance alone. The assumption of a wrist seizure is that a sword has already been (minimally) fully drawn, and the seizure is seeking to prevent further employment of a cut along those lines. For the wrist of tori to be seized in such a scenario the initial combative gap must have already been closed via the successful evasion of an initial cut. Hence foundational skills in the navigation of combative distance, evasive footwork, and entering maneuvers would have already been developed amidst the clarity of the intention of a sword cut or mimed empty hand variation thereof (such as shomen uchi).

Such a perspective might posit the best path forward as initiating the teaching of basic skills via a third option that is neither wrist seizure nor strike (or cut), but perhaps a didactic and neutral offering of instruction from an anatomically neutral position. And while this path might be more viable than continuing to attempt foundational instruction from the point of a static wrist grab, the inference to be understood here is that the very nature of fundamental skills should be re-examined.

Ikkyo (arm bar), nikyo (inside wrist lock), sankyo (spiral wrist lock), and kote gaeshi (outside wrist lock), for instance, are not in fact the foundational skills of the Aiki knowledge base. Rather, these are themselves second level skills to the true fundamentals of defensive covering, evasive body maneuvering, and the footwork that allows one to close the combative range while appropriately positioning oneself outside of the targeted position, and making initial harmonizing contact with uke.

~Sunyananda

#budo#martial arts#shugyo#aiki#aikido#karate#aikijutsu#aikijujutsu#ikkyo#nikyo#sankyo#kote gaeshi#wrist grab#hapkido#ma ai#mudo

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Rank, Lineage and the Like

I’m remembering this morning a pithy lesson from a martial arts colleague, nearly a couple decades ago that has stayed on my mind since then. Namely, the only people who say that rank isn’t important are those that have too much, and those that have too little. This applies to many things.

~Sunyananda

#budo#martial arts#shugyo#aiki#aikido#karate#Dan rank#black belt#shodan#lineage#title#Shihan#reneging#kyoshi#hanshi

0 notes

Text

Honesty and Efficacy

In martial arts, as in life generally, there is no magic as such. If you’re going to forego a reliance on strength (and you should), you must pay close attention to bodily structure and the mechanics of motion (think balance, leverage, angles, and kinesiology). Too one must account for focus and the psychology of conflict, but not at the expense of accounting for physics. It is the integrative consideration of these factors that give rise to the efficiency, efficacy, and relative effortlessness that begin to look and maybe even feel like magic. Relying on obscure and poetic principles that only infer a connection to physics rather than exploring them overtly is ignorant at best and willfully deceptive at worst.

~Sunyananda

0 notes

Text

On Takemusu Aiki, Judo’s Maxims, and Inferential Hypnosis

In October of 1930 the founder of Judo, Dr. Jigoro Kano paid a visit to the mystic and martial arts master Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido at the Meijiro Dojo. Upon witnessing Ueshiba’s technique, and in particular Ueshiba’s ease in handing out techniques to some of Kano’s top students it is recorded that Kano exclaimed “This is the ideal budo — true Judo!” Following this, Kano went as far as requesting that Ueshiba take on a few of his top students and allow that they routinely report back and share their training with him. Ueshiba obliged.

Today, Judo remains one of, if not the most respected of the traditional martial arts in the face of modern mixed martial arts training methods. Aikido on the other hand is probably the least, that is to say when it is even regarded as a martial art rather than an obscure system of physical culture on par with the likes of Tai Chi. There seems to be many reasons for this, not the least of which is that Judo went the way of negotiating the cinch, whereas Aikido remained hyper focused on relating to classical sword work, albeit often in an empty hand fashion.

In Aikido the focus of the day tends to be negotiating an infinite array of static wrist grabs (big concerns for a swordsman seeking to deploy a blade, and for opponents seeking to seize such deployment), and when not static wrist grabs then overhead striking maneuvers mimicking the downward, diagonal, and horizontal cuts of a sword. In other words, physical methods that are seldom encountered in the modern world, or even in the dojo with the amount of intent and energy to allow them to become dynamic rather than static initiations of technique.

To be clear the foundational techniques and principles of Aikido are remarkably well curated, condensing the knowledge of Daitoryu Aikijutsu (especially) into a workable system of concepts that can manipulate the human physiology quite well, to varied effects ranging from gentle neutralization (the ideal) to more dramatic arresting outcomes. However, in many Aikidojo, the focus tends to veer too quickly to what O’sensei Ueshiba called Takemusu Aiki.

Takemusu Aiki is a most advanced stage of Aiki training and cultivation wherein technique is spontaneously birthed rather than repetitiously learned. Here concerns for physiology and kinesiology are ultimately transcended, not for a lack of regard but for their integration and incorporation at more and more minute levels overtime, allowing for an almost magical expression of subtle technique in both look and feel. Arguably at this level techniques incorporate as much psychology as physiology, in blending with and manipulating the spirit (literally the psyche) and intent of the opponent or training partner. For this to be possible, though, intent must be present.

Ultimately Kano’s Judo is founded upon two central maxims, namely minimal effort with maximal result, and mutual welfare and benefit for all. These apply equally to the dojo environment as they may to the so-called real world, and perhaps can contextually help Aikido reclaim a respectable place as a “true Budo.”

Kano’s maxims have always been applied in a milieu of live training, that is of dynamic initiations with appropriate intention and resistance. In this environment relatively few Aikidoka can manifest efficacious foundational technique let alone true Takemusu Aiki. This goes to say that more time should be spent in the relentless pursuit of basic waza in increasingly dynamic circumstances, which means less time negotiating the seeming intricacies of static wrist grabs. Ultimately dynamic, live practice of the fundamentals is the only thing that can give yield to the spontaneous and authentic expression of Takemusu Aiki, which is frequently confused in this day and age with physical culture oriented parlor tricks, and more insidiously with mutual inferential hypnosis.

Takemusu Aiki is an extension of Shugyo - daily training of sufficient austerity to give rise to total integration of mind and body, wherein spirit manifests and transcends the limits of our conceptual engagement with practice. For this to be possible, though, for practice to eventually manifest as Shugyo one should break a sweat and push through the limits of boredom that will eventually accompany a relatively small number of principles expressed as techniques, engaged over, and over, and over again. In this, resistance and intention are the true bedfellows of Shugyo.

~Sunyananda

#aikido#Aiki#Takemusu#Takemusu Aiki#judo#budo#Ueshiba#Kano#morihei Ueshiba#jigoro Kano#shugyo#waza#martial arts

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

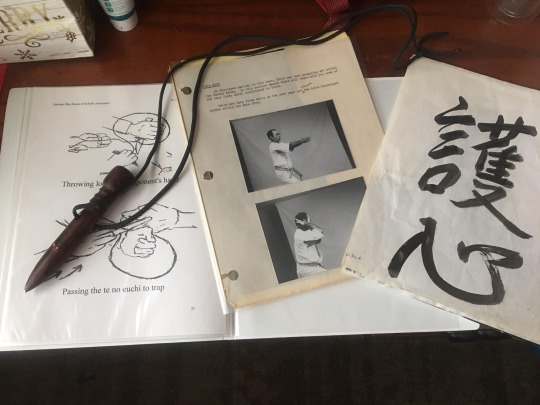

Remembering Soke

Soke passed away just before Covid really took off last year, and so here we are, over a year later, finally able to gather for his memorial. Students from Utah, Wyoming, Nebraska, Missouri, Indiana, and Ohio have all converged upon KC this weekend to pay our respects, and do what he’d have us be doing, training in the martial and healing arts! Soke’s wishes were that his ashes be kept in my temple, so his altar during the event is upon a Buddhist bowing cloth, replete with a nyoi (a ceremonial scepter of authority that represents a spine in proper alignment for meditation and martial arts), and one of his beloved quick cappuccinos!

~Sunyananda

0 notes

Text

Remembering My Early Training

I feel really quite fortunate to have stumbled into classical martial arts when I was a kid. As opposed to the more generic and significantly less exciting forms of kick-punch arts out there, my experience of Ryukyu Kempo was infinitely more colorful and arguably deep, if not at times in unintended and unexpected ways.

The first several weeks of training in Ryukyu Kempo consisted of wearing normal clothes to a class of black (yes black) dogi clad students practicing an array of empty handed kata, alongside kobujutsu, and distinct grappling maneuvers called tuite. I, however (like most new students at the time) was slated to make my way to the edge of the training area to watch class, and more importantly, to make friends with “Mr. Suburito.”

A suburito is an extra large, weighted wooden training sword. Despite its already bulky nature, the more senior students of the school would bore out holes along the blade of the veritable branch and fill them with lead for extra difficulty. My adult-sized, but not otherwise modified “Mr. Suburito” was quite enough for me to handle in awkwardly learning how to carry and draw him, so as to perform a great many downward, centerline cuts subsequently. I mean wooden swords are cool and all, but it was admittedly a little curious way to begin training in what I expected to be generically open handed karate art. Fast forward 20+ years later and I’m still discovering the nuance of that particular exercise in reference to my open handed skill set (including both striking and grappling) and my practice of kobujutsu at large.

After a few weeks of learning to relate to Mr. Suburito, I was introduced to Naihanchi Shodan as my first kata (solo exercise), rather than a taikyoku or kihon (typically low block and middle punch) manner of pattern.

The instruction given for the seemingly arcane Naihanchi kata was that the interestingly venerated Master Choki Motobu famously noted it was the only thing needed to gain a complete knowledge of karate. Beyond that, according to the Guiding Principles of our school “in the past a single master studied a single Kata for more than ten years…” and that if we just wholeheartedly threw ourselves into the practice of the kata (which follows a single horizontal, line enbusen [floor pattern] that sees the student moving left and right in a side-oriented kiba dachi [horse stance], while performing 27 duplicated movements at the left, right and center of the body, including two seeming ritualized double handed “salutes”) we would be well on our way to becoming truly skilled and wise practitioners of the art.

All of these things about the Naihanchi Kata were of course true, and after quite literally hundreds of thousands of repetitions of that particular 27-movement form over the course of more than two decades, I still cannot pretend to fully grok the contents and blueprints contained within that one archetypal form. Nonetheless, the unspoken fact was too that Mr. Suburito and the arcane Naihanchi Kata (despite the realities of the respective, intentionally subtle and skillful physical conditioning technologies contained within them) were really about slowly introducing a potential new member of the dojo into the actual training methods of the style and school without revealing anything too obviously dangerous, should the new recruit to prove to not be of the “good moral character” demanded by the Dojo Kun. Should that be the case, and should such a recruit find themselves to have worn out their welcome, the public was nominally protected, and the secrets of the school were further safeguarded by those deemed trustworthy enough to receive them. To return again to an examination of the Guiding Principles “the eagle with the sharpest talons hides them.”

As you can imagine, the onboarding process was a little more lengthy than that at a typical karate school. I recall distinctly having to memorize and be able to recite on command the five statements of the Dojo Kun (school code) and the ten paragraphs comprising the Guiding Principles (about a typed page and a half combined) before being able to progress beyond Mr. Suburito’s lone company.

After Naihanchi Shodan was sufficiently committed to mental and physical memory, and an exercise or two beyond simple striking sets with Mr. Suburito, two more similarly single, horizontal line enbusen comprised Naihanchi Kata (Nidan and Sandan) would follow, before I (the student) would actually be introduced to anything clearly resembling combat in posture, gesture, or movement in the truly unique “Tomari” Seisan (which is in fact a rather intricate white crane form, as opposed to most other forms sharing its name). For me this took about a year (without receiving or testing for a single belt rank along the way; curiously even the black belts didn’t wear rank belts, only a unique form of pantaloons called nobakhama, with but a couple of students who had here-and-there tested for a colored belt donning one).

However, it’s notable that within three or so weeks I (who hadn’t been yet taught how to do a simple block or strike in the manner of the system) would suddenly find myself introduced to the chizikun bo, a type of paired koppo (6” sticks with leather finger loops drilled through their centers, used as weapons, which are placed over the middle fingers of both hands). As it turns out a 7th Dan Kyoshi (Master) of the art would be teaching a rare form for the weapon at an even rarer full weekend training camp alongside a river at a distant and rural campsite.

You see, Kyoshi was always on the verge or “retiring,” and taking his still undivulged body of genuinely unique knowledge with him. Kyoshi never could quite get a successful dojo up and running himself (in fact the dojo was quite transient and moved or closed at least once a year) but nonetheless he (due to a mixture of actual skill and cowboy charisma) kept a pretty dedicated band of students within his orbit.

Whenever Kyoshi was strapped for cash a special training called a “Spirit Class” (a four+ hour day of Mr. Suburito and Naihanchi-esque kiba dachi chudan tsuki [horse stance middle punches]) could be scheduled for a nominal fee, inclusive of a custom screen printed t-shirt. If the bank was really coming to task though, a new, and somehow legitimately rare kobujutsu kata could be transmitted, replete with a custom printed t-shirt (for one low price) over the course of a weekend, and all hands were to be on deck. At no extra cost came the knowledge that if you open the advanced chizi kata the wrong way it “looks like you guys are trying to tear your peckers off” (LMAO, seriously) and that if you want to shower at a rural campsite you should stop and get quarters first, and that when you stop and get quarters first you should make sure that the item you’re buying to break cash into change with costs an appropriate amount so as to retrieve quarters in change. Twelve and thirteen year olds have to learn this stuff sometime! 😉

At this point I feel it worthwhile to note that Kyoshi did eventually retire and move out of state and out of touch, with some yet untaught and authentically rare and valuable skills in tow. I still practice that kata, or what I think I was taught at the time, and I’ve met very few people that know the “advanced chizi kata.”

Picking back up in week five of my training (and far beyond) Naihanchi Nidan and Sandan were gradually learned, and suddenly I had been indoctrinated and inducted properly into the tradition. By then I practiced my kata and exercises single mindedly while lusting over a copy of the Grandmaster’s newly self-published textbook. The textbook was sold only by a single school in his association for what was then (and now, but then especially) a very steep price of $65 (and a far cry from the $15 cost of his senior student’s very useful introductory manual sold in the same venue).

Speaking of those students and that venue, it was around this time that I recall that I began to realize that our faction of the art was no longer in the good graces of the Grandmaster’s association, and that there existed some really bad juju between the two camps. But regardless, we were all agreed that we were far superior to, and would not associate ourselves with, the third group of people accused of having stolen some of the secrets of the Grandmaster’s art at a few generous public seminars.

But I digress. For us, our “classical” system (as opposed to “traditional,” or the even more anathema “modern” styles) of karate was supreme (and admittedly the older I get the more my bias does swing that way among Japanese and Okinawan striking arts). Labeled sell-outs like Gichen Funakoshi of Shotokan fame were but “shamisen players with silver tongues who only ever learned the outside of karate” (or so said that curious younger Master Motobu again…the older Master Motobu was quite more refined in manners and skill). In short, if you wanted to real deal, you had to come to us.

My early life experience in Ryukyu Kempo introduced me to some of the most wonderful and valued friends and mentors in my life who I have been blessed to have cherished relationships with for decades now. Too, it broke (early on, in life and in training) many of my romantic conceptions of humanity, while also providing me an all but stereotypicalized idyllic training milieu. I really couldn’t have had it better anywhere else.

~Sunyananda

1 note

·

View note

Text

Now that we have a nice, newly refinished porch, I’ve taken up adding suburito strikes to my morning shugyo (training). For now 50 double handed swings on each side, and 10 single handed swings on each side for a total of 120 each morning.

Suburito (weighted sword training) is inextricably linked to open handed martial arts, from the repetitive shuffle steps from center, to training for centerline punches on front hand, and grip training for tuidi (joint manipulation common to Okinawan Kempo) and gakkun (meridian line pressure point grip common to Jujutsu) on the rear hand.

In proper suburito training the sword is raised above the head (jodan kamae) and swung with appropriate speed to the middle position (chudan kamae) where a squeezing-ringing grip abruptly stops the hilt at the hara (theee fingers beneath the navel, centerline) and the tip of the blade at the solar plexus, relaxing the grip as soon as the sword stops. This is paired as noted with a backward and forward shuffle step and appropriate inward and outward breath. When the sword is taken away the exercise is very much akin to aiki taiso (the solo exercises of aikido) specifically shomen uchi undo.

For the first twenty years of my training I really didn’t understand shugyo. I trained for a purpose, to gain a specific skill set, to memorize curricula, and to accomplish measurable objectives. Generally speaking, like shikantaza (silent illumination in Zen), shugyo is practice without aim. Practice for the sake of practice, completion seeking completion in and of its own accord. It’s a difficult process to describe, but when the curricula runs out, when there are no more promotions or recognitions to be had, and no one to “beat” or impress, we make room for the mysterious and arguably spiritual processes of daily training, namely shugyo.

~Sunyananda

0 notes